Search for:

Jump straight to:

Please enter a search term

What sectors are you interested in?

We can use your selection to show you more of the content that you’re interested in.

Sign-up and we’ll remember your preferences

Sign-up to follow topics, sectors, people and also have the option to receive a weekly update of lastest news across your areas of interest.

Got an account already? Sign in

Want to speak to an advisor from your closest office?

Out-law / your daily need-to-know.

Out-Law Guide 1 min. read

Assigning patent rights to others

17 Aug 2018, 3:32 pm

This guide is based on UK law. It was last updated in August 2018.

Requirements or restrictions for assignment of intellectual property rights

An assignment of a patent or patent application is void unless it is in writing.

Post 1 January 2005, the need for assignments to be signed by both assignees and assignors was removed for assignments of UK patents. This change was effected via the Regulatory Reform (Patents) Order 2004. Nevertheless, it is still common for both parties and not just the assignor to sign a UK patent assignment.

Assignments of EU patent applications do need to be signed by the assignee and assignor and must be in writing, under Article 72 of the European Patent Convention.

There are specific provisions which may be implied into UK patent assignments.

Under UK law set out in section 30(7) of the Patents Act 1977, patent assignments should include the right to bring proceedings for any previous infringements.

The public have a right to inspect the register of patents maintained by the Comptroller General of Patents, Designs and Trade Marks, who leads the UK's Intellectual Property Office (IPO). There is no obligation to register the assignment or licence with the IPO. That said, it is advisable to register the assignment or licence as soon as possible.

Registration gives priority to the registered rights which can defeat earlier claims of unregistered rights. Additionally, if the patent owner fails to register the transaction within six months its rights to claim costs for litigating an infringement that occurred before registration are diminished, unless the patent owner can prove to the court it was not reasonable or practicable to register it in that period.

Procedure for registration

It is a simple process to register a patent application or patent assignment or licence in the UK.

An application to the IPO is made using Patent Form 21 and a small fee is payable. It must include evidence establishing the transaction; however, this does not need to be a copy of the assignment itself. A redacted photocopy of the licence or assignment is sufficient.

To register a licence or assignment in the European Patent Office (EPO), the request must be in writing and accompanied by documents satisfying the EPO that the licence or assignment has been granted. A statement signed by the assignor/licensor that the assignment or licence has been granted is also sufficient.

There is no requirement for a licence, exclusive or non-exclusive, to be in writing; however, it is advisable for it to be so. This is to ensure certainty of terms, allow the parties to secure the benefits and rights of the registration and to designate the law and jurisdiction which governs the licence.

- Commercial Litigation

- Enforcement

- Intellectual Property

- Life Sciences & Health

- Technology & Digital Markets

- Technology, Science & Industry

- United Kingdom

Contact an adviser

Catherine Drew

Charlotte Weekes

Partner, Head of Life sciences

Christopher Sharp

Clare Tunstall

Latest News

Telecoms providers must ensure transparency following asa ruling and ofcom guidance, property rights in digital assets provided for in ‘landmark’ bill, uk offshore wind projects get customs duty boost, universities must ensure effective franchising risk management, fca enforcement report indicates shift towards data-driven interventions, don't miss a thing.

Sign-up to receive the latest news, analysis and events direct to your e-mail inbox

You might also like

Out-Law News

Decision highlights Irish Courts’ resistance to the commodification of litigation

A recent Irish Court of Appeal ruling highlights the significant work that needs to be done before reform is undertaken on third-party litigation funding in Ireland, an expert has said.

Bank of England tells firms to test for ‘extreme but plausible’ service disruption

Operators of financial markets infrastructure (FMIs), such as payment systems, have been advised to anticipate – and undertake robust testing around – “extreme but plausible” scenarios that could cause disruption to services, ahead of new rules on operational resilience taking effect in the UK next year.

UK government to ‘fine-tune’ NSI regime following consultation

The UK government will seek to “fine-tune” its national security investment screening regime to stay ahead of potential national security threats following a recent consultation outcome and in light of recent geopolitical developments, it has announced.

Trending topics across the site:

- Employment & Reward

- Construction Advisory & Disputes

- Corporate tax

- Construction Contracts

- International Arbitration

UK government plans to revamp holiday pay calculation for part-year workers

Out-Law Analysis

Pensions disputes: managing member expectations paramount

UK subsidy control post-Brexit: access to effective judicial remedies

'Steps of court' settlement was not negligent, court rules

'Vast majority' of companies not seeking to avoid tax

'World first' industrial decarbonisation strategy developed in the UK

3D printing: UK product safety issues

5G potential for business highlighted in UK funding programme

Sectors and what we do

Sectors we work in.

- Financial Services

- Infrastructure

- Real Estate

- Your assets

- Your company

- Your finance

- Your legal team and resource

- Your people

- Your risks and regulatory environment

Your privacy matters to us

We use cookies that are essential for our site to work. To improve our site, we would like to use additional cookies to help us understand how visitors use it, measure traffic to our site from social media platforms and to personalise your experience. Some of the cookies that we use are provided by third parties. To accept all cookies click ‘accept all’. To reject all optional cookies click ‘reject all’. To choose which optional cookies to allow click ‘cookie settings’. This tool uses a cookie to remember your choices. Please visit our cookie policy for more information.

The Basics Of Patent Law - Assignment And Licensing

Contributor.

Gowling WLG's intellectual property experts explain assignment and licensing in a series of articles titled 'The basics of patent law'.

The articles cover, respectively: Types of intellectual property protection for inventions and granting procedure ; Initiating proceedings ; Infringement and related actions ; Revocation, non-infringement and clearing the way ; Trial, appeal and settlement ; Remedies and costs ; Assignment and Licensing and the Unified Patent Court and Unitary Patent system.

The articles underpin Gowling WLG's contribution to Chambers' Global Practice Guide on Patent Litigation 2017 , for which Gordon Harris and Ailsa Carter wrote the UK chapter .

Introduction

Any patent, patent application or any right in a patent or patent application may be assigned (Patents Act 1977 (also referred to as "PA") s.30(2)) and licences and sub-licences may be granted under any patent or any patent application (PA s.30(4)).

The key difference between an assignment and a licence is that an assignment is a transfer of ownership and title, whereas a licence is a contractual right to do something that would otherwise be an infringement of the relevant patent rights. Following an assignment, the assignor generally has no further rights in relation to the relevant patent rights. On the granting of a licence, the licensor retains ownership of the licensed rights and generally has some continuing obligations and rights in relation to them (as set out in the relevant licence).

Formalities

Any assignment of a UK patent or application, or a UK designation of a European patent, must be in writing and signed by, or on behalf of, the assignor. For an assignment by a body corporate governed by the law of England and Wales, the signature or seal of the body corporate is required (PA s.30-31). With regards the assignment of a European patent application however, such assignment must be in writing and signed not just by the assignor but by both parties to the contract (Article 72 EPC).

There is no particular statutory provision regarding the form of a licence or sub-licence (exclusive or otherwise). However, in view of the advisability of registration (discussed below) and legal certainty, it is sensible that any licence be in writing. In addition, normal contractual formalities apply, such as intention to create legal relations, consideration and certainty of terms, etc.

Registration

Registration (with the UKIPO) of an assignment or licence is not mandatory. However, if the registered proprietor or licensor enters into a later, inconsistent transaction, the person claiming under the later transaction shall be entitled to the property if the earlier transaction was not registered (PA s.33). Registration is therefore advisable. Failure to register an assignment or an exclusive licence within six months will also impact the ability of a party to litigation to claim costs and expenses (PA s.68) and might, potentially, enable an infringer to defend a claim for monetary relief on the basis of innocent infringement (PA s.62).

The procedure for registration is governed by the Patents Rules 2007. The application should be made on the appropriate form, should include evidence establishing the transaction, instrument or event, and should be signed by or on behalf of the assignor or licensor. Documents containing an agreement should be complete and of such a nature that they could be enforced. A translation must be supplied for any documentary evidence not in English.

In practice (particularly in the context of a larger corporate transaction in which many different asset classes are being transferred, not just intellectual property), parties sometimes agree short form documents evidencing the transfer of the relevant patent rights and will submit these for registration. This can enable parties to save submitting full documents for the whole transaction, which may include sensitive commercial information that is not relevant to the transfer of the patent rights themselves.

Types of licence

A licensee may take a non-exclusive or exclusive licence from the licensor. The distinction between such licences is both legally and commercially significant.

On a basic level an exclusive licence means that no other person or company can exploit the rights under the patent and this means the licensor is also excluded from exploiting such rights. Exclusivity may be total or divided up by reference to, for example, territory, field of technology, channel, or product type. The extent of exclusivity generally goes to the value of the rights being licensed and will feed into the agreed financials. It is worth noting that the term "exclusive licence" does not have a statutory definition under English law, so it is very important to define the contractual scope of exclusivity in the relevant licence agreement.

In the event a licensor wants to retain the ability to exploit the rights in some way (for example an academic licensor may want the ability to continue research activities) then appropriate carve outs from the exclusivity should be expressly stated in the licence agreement.

A non-exclusive licensee has the right to exploit rights within the patent as determined by the licence agreement. However, the licensor may also exploit such rights as well as granting multiple other licences to third parties (which may include competitors of the original licensee).

Much less common is a sole licence, by which the patent proprietor agrees not to grant any other licences but gives the licensee the right to use the technology and may also still operate the licenced technology itself.

Compulsory licences

A compulsory licence provides for an individual or company to seek a licence to use another's patent rights without seeking the proprietor's consent. Compulsory licences under patents may be granted in circumstances where there has been an abuse of monopoly rights, but are very rarely granted in the UK.

An application for a compulsory licence can be made by any person (even a current licensee of the patent) to the Comptroller of Patents at any time after three years from the date of grant of the patent. In respect of a patent whose proprietor is a national of, or is domiciled in, or which has a real and effective industrial or commercial establishment in, a country which is a member of the World Trade Organisation, the applicant must establish one of the three specified grounds for relief. If satisfied, the Comptroller has discretion as to whether a licence is granted and if so upon what terms. The grounds are:

- demand for a patented product in the UK is not being met on reasonable terms;

- the exploitation in the UK of another patented invention that represents an important technical advance of considerable economic significance in relation to the invention claimed in the patentee's patent is prevented or hindered provided that the Comptroller is satisfied that the patent proprietor for the other invention is able and willing to grant the patent proprietor and his licensees a licence under the patent for the other invention on reasonable terms;

- the establishment or development of commercial or industrial activities in the UK is unfairly prejudiced;

- by conditions imposed by the patentee, unpatented activities are unfairly prejudiced.

The terms of the licence shall be decided by the Comptroller but are subject to certain restrictions on what type of licence can be granted, namely the licence: cannot be exclusive; can only be assigned to someone who has been assigned the part of the applicant's business that enjoys use of the patented invention; will be for supply to the UK market; will include conditions allowing the patentee to adequate remuneration; and must be limited in scope and duration to the purpose for which the licence is granted.

Infringement

The type of licence is also significant when it comes to tackling infringement. Under statute, an exclusive licensee has the same right as the proprietor of a patent to bring proceedings with respect infringement committed after the date of the licence and such proceedings may be brought in the licensee's name (PA 67(1)). An exclusive licensee of a patent application may also bring proceedings in its own name (PA ss. 67(1) & 69). In practice, however, these statutory provisions are often excluded or varied by parties negotiating complex licensing transactions. A licensee may also have a right under a licence to bring proceedings for an infringement occurring before the licence came into effect.

A non-exclusive licensee does not have any right under statute to bring proceedings in its own name. However, this could be negotiated into a licence agreement, though it may be difficult for a licensor to agree this point if it has multiple non-exclusive licensees.

Effect of non-registration on infringement proceedings

There is no requirement that a licence must be registered before proceedings can be commenced by an exclusive licensee. However, non-registration can affect a licensee's ability to recover its costs in relation to such proceedings.

Implied terms

Established rules of construction apply to assignment and licence agreements. Parties should ensure that important terms are included as express terms. There is no implied warranty that any assigned or licensed patent will be valid, or that an assignee or licensee will work the invention (for example, that they will exploit the rights and manufacture products). In certain very limited circumstances a court will order 'rectification' of an assignment or licence agreement, namely a court will order a change in the assignment or licence agreement to reflect what the agreement ought to have said in the first place. Regardless of this, all key terms should be included expressly in all assignment and licence agreements.

Termination of licences

Except where there is express contractual provision or where a licence has been wrongly terminated and damages sought, under English law there is no compensation payable to licensees on termination of a licencing agreement. The licence agreement should be clear as to what circumstances may give rise to termination, for example the non-payment of royalties, material breach or insolvency. The agreement should also make clear what happens in the event of termination in relation to, for example, existing stock of licensed products or work in progress.

Next in our 'The basics of patent law' series, we will be discussing the Unified Patent Court and Unitary Patent system.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.

Intellectual Property

United kingdom.

Mondaq uses cookies on this website. By using our website you agree to our use of cookies as set out in our Privacy Policy.

Assignments overview and pitfalls to beware!

03 December 2012

Many patents will see a change in ownership at some stage in their lives. Assignments are commonplace and occur for a variety of reasons; for example, in the context of a business sale where a buyer purchases all of the assets (including intellectual property assets) of a business from the vendor. Another is in the context of intra-group reorganisations.

Assignments can also occur as part of settlement of a dispute. This article outlines some of the pitfalls of which you should be aware when assigning patents; many of which can be averted by careful drafting of the assignment agreement.

Unless the assignment is intra-group, there will usually be some distance between what the assignee wants (typically, a variety of representations, warranties and indemnities in respect of the assigned rights) and what the assignor is prepared to give. This is a commercial decision and hence no two negotiated patent assignments will be identical.

Consideration

Under English law, to be a valid contract there must be consideration which is either money or money's worth. This is often overlooked but a key point required for the assignment agreement to be legally binding. Whilst the acceptance of mutual obligations may suffice, it is simplest to have a sum of money (even if only for £1). An alternative is to execute the assignment as a deed, though there are specific formalities which must be followed for the agreement to be a deed. Of course, if the parties agree to nominal consideration (eg, £1), it is important that this small amount is actually paid to the assignor.

An assignment of a UK patent (or application) must be in writing and signed by the assignor. It used to be the case that an assignment of a UK patent (or application) would need to be signed by both parties, however the law was changed in 2005. In reality, both parties will usually sign the assignment agreement. Where one or both of the parties is an individual in their personal capacity or a foreign entity, special 'testimonial' provisions are required; for example the signature to the assignment may need to be witnessed.

The assignment

English law distinguishes two types of assignment: legal and equitable. To assign the legal interest in something means that you have assigned simply the title to that property and not the right to exercise the rights inherent in it. This is the equitable (beneficial) interest and if this is not also assigned with the legal title, this can result in a split in ownership. Unless the parties specifically agree otherwise, legal and beneficial ownership should always be assigned together. It is possible to have co-assignees (ie, co-owners) but the terms of the co-ownership will need to be carefully considered.

It is possible to assign the right to bring proceedings for past infringements in the UK, but not in some other jurisdictions. Where non-UK rights are involved, local advice may be required as to whether such an assignment would be enforceable as against a prior infringer. This potential uncertainty makes a robust further assurance clause even more desirable (see below), to ensure the assignor's co-operation after completion of the assignment.

The assignee will also typically argue for (and the assignor will typically resist) a transfer with 'full title guarantee', as this implies as a matter of law certain covenants: that the assignor is entitled to sell the property; that the assignor will do all it reasonably can, at its own expense, to vest title to the property in the assignee; and that the property is free from various third party rights.

In terms of European patents (EP), it is important to remember that ownership of an EP application is determined under by the inventor/applicant's local law, rather than under European patent law. This means that a formal, written assignment agreement should be executed to ensure that the applicant is entitled to ownership of the patent application, for example in cases where the work undertaken was done by a consultant or where local law dictates that the owner is the inventor(s). An assignment should include assignment of the right to claim priority, as well as the right to the invention and any patent applications. This need to obtain an effective assignment of the application (and right to claim priority) is particularly important where a priority application has been made in the name of the inventor. If such an assignment is not executed before applications which claim priority from earlier cases (for example, PCT applications) are filed, the right to ownership and/or the right to claim priority may be lost.

Don't forget tax

Currently, there is no stamp duty payable on the assignment of intellectual property in the UK. However, particularly for assignments which include foreign intellectual property rights, there can be considerable tax implications in transferring ownership of intellectual property rights in some countries and it is always prudent to check that the transfer will not result in excessive tax liabilities for you.

Update the register

Registered rights need to be updated at the patent offices. You will need to decide who pays for this: in the case of one patent, it is a simple process, however in the case of a whole portfolio, the costs can be considerable. Remember, if you ever need to take any action on a patent you own, you need to ensure you are the registered owner of that right at the applicable office.

In the UK, assignments can be registered but there is no statutory requirement to do so. In the case of international assignments, local offices may require recordal of the assignment. In any event, it is desirable for an assignee to ensure that the transaction is recorded. Section 68 of the UK Patents Act provides that an assignee who does not register the assignment within six months runs the risk of not being able to claim costs or expenses in infringement proceedings for an infringement that occurred before registration of the assignment, although recent case-law has reduced this risk somewhat.

Further assurance

The assignee will typically take charge of recordals to the Patents Offices; however they will often need the assignor's help in doing so. A 'further assurance' clause is a key element of the assignment from an assignee's point of view both for this purpose and for assisting in the defence and enforcement of patents or applications for registration. On the other hand, the assignor will typically seek to qualify its further assurance covenant by limiting it to what the assignee may reasonably require, and that anything done should be at the assignee's expense. An assignor should also require that recordals are done promptly to minimise their future correspondence from patent offices.

International transactions

In transactions which involve the transfer of patents in various countries, the parties can execute a global assignment which covers all the patents being transferred, or there can be separate assignments for each country. The former, global assignment, is usually preferred however this will frequently need to be supplemented by further confirmatory assignments in forms prescribed by the relevant international patent registries. As noted above, the preparation and execution of such assignments can be time-consuming and costly, hence the need to decide in advance who bears the cost of such recordals, and the assignee should insist on a further assurance provision.

Sharing IP information such as new legislation, relevant case law, market trends and other topical issues is important to us. We send out our IP newsletters by email about once a month, publish IP books annually, share occasional IP news alerts and also invitations to our IP events such as webinars and seminars. We take your privacy seriously and you can change your mailing preferences or unsubscribe at any time.

To sign up to our marketing communications, please fill out this form.

Your contact details

What would you like to hear from us about?

You can contact us at [email protected], telephone +44 (0) 20 7269 8850 or write to us at D Young & Co LLP, 3 Noble Street, London, EC2V 7BQ to update your preferences at any time.

We use cookies in our email marketing communications. You can view our privacy policy here and cookie policy here .

Almost finished! Submit this form and we will send you an email for you to confirm your preferences.

Cookies on GOV.UK

We use some essential cookies to make this website work.

We’d like to set additional cookies to understand how you use GOV.UK, remember your settings and improve government services.

We also use cookies set by other sites to help us deliver content from their services.

You have accepted additional cookies. You can change your cookie settings at any time.

You have rejected additional cookies. You can change your cookie settings at any time.

The Patents Act 1977

The Patents Act 1977 is the main law governing the patents system in the UK.

The Patents Act 1977 (as amended)

PDF , 884 KB , 102 pages

https://www.gov.uk/guidance/the-patent-act-1977

The Patents Act 1977 sets out the requirements for patent applications, how the patent-granting process should operate, and the law relating to disputes concerning patents. It also sets out how UK law relates to the European Patent Convention and the Patent Co-operation Treaty.

The latest amendment to the Patents Act 1977 took place on 31 December 2019 and was made by the Patents (Amendment) (EU Exit) Regulations 2019 and the Intellectual Property (Amendment etc.) (EU Exit) Regulations 2020.

Updates to this page

Updated with changes made by legislation which came into force at the end of the transition period and 1 January 2021.

Online version added.

Updated due to changes made by the Intellectual Property (Unjustified Threats) Act 2017.

Updated due to changes by legislation including the Intellectual Property Act 2014 and the Legislative Reform (Patents) Order 2014.

First published.

Sign up for emails or print this page

Related content, is this page useful.

- Yes this page is useful

- No this page is not useful

Help us improve GOV.UK

Don’t include personal or financial information like your National Insurance number or credit card details.

To help us improve GOV.UK, we’d like to know more about your visit today. Please fill in this survey (opens in a new tab) .

- More Blog Popular

- Who's Who Legal

- Instruct Counsel

- My newsfeed

- Save & file

- View original

- Follow Please login to follow content.

add to folder:

- My saved (default)

Register now for your free, tailored, daily legal newsfeed service.

Find out more about Lexology or get in touch by visiting our About page.

The basics of patent law - assignment and licensing

Gowling WLG's intellectual property experts explain assignment and licensing in a series of articles titled 'The basics of patent law'.

The articles cover, respectively: Types of intellectual property protection for inventions and granting procedure ; Initiating proceedings ; Infringement and related actions ; Revocation, non-infringement and clearing the way ; Trial, appeal and settlement ; Remedies and costs ; Assignment and Licensing and the Unified Patent Court and Unitary Patent system.

The articles underpin Gowling WLG's contribution to Chambers' Global Practice Guide on Patent Litigation 2017 , for which Gordon Harris and Ailsa Carter wrote the UK chapter .

Introduction

Any patent, patent application or any right in a patent or patent application may be assigned (Patents Act 1977 (also referred to as "PA") s.30(2)) and licences and sub-licences may be granted under any patent or any patent application (PA s.30(4)).

The key difference between an assignment and a licence is that an assignment is a transfer of ownership and title, whereas a licence is a contractual right to do something that would otherwise be an infringement of the relevant patent rights. Following an assignment, the assignor generally has no further rights in relation to the relevant patent rights. On the granting of a licence, the licensor retains ownership of the licensed rights and generally has some continuing obligations and rights in relation to them (as set out in the relevant licence).

Formalities

Any assignment of a UK patent or application, or a UK designation of a European patent, must be in writing and signed by, or on behalf of, the assignor. For an assignment by a body corporate governed by the law of England and Wales, the signature or seal of the body corporate is required (PA s.30-31). With regards the assignment of a European patent application however, such assignment must be in writing and signed not just by the assignor but by both parties to the contract (Article 72 EPC).

There is no particular statutory provision regarding the form of a licence or sub-licence (exclusive or otherwise). However, in view of the advisability of registration (discussed below) and legal certainty, it is sensible that any licence be in writing. In addition, normal contractual formalities apply, such as intention to create legal relations, consideration and certainty of terms, etc.

Registration

Registration (with the UKIPO) of an assignment or licence is not mandatory. However, if the registered proprietor or licensor enters into a later, inconsistent transaction, the person claiming under the later transaction shall be entitled to the property if the earlier transaction was not registered (PA s.33). Registration is therefore advisable. Failure to register an assignment or an exclusive licence within six months will also impact the ability of a party to litigation to claim costs and expenses (PA s.68) and might, potentially, enable an infringer to defend a claim for monetary relief on the basis of innocent infringement (PA s.62).

The procedure for registration is governed by the Patents Rules 2007. The application should be made on the appropriate form, should include evidence establishing the transaction, instrument or event, and should be signed by or on behalf of the assignor or licensor. Documents containing an agreement should be complete and of such a nature that they could be enforced. A translation must be supplied for any documentary evidence not in English.

In practice (particularly in the context of a larger corporate transaction in which many different asset classes are being transferred, not just intellectual property), parties sometimes agree short form documents evidencing the transfer of the relevant patent rights and will submit these for registration. This can enable parties to save submitting full documents for the whole transaction, which may include sensitive commercial information that is not relevant to the transfer of the patent rights themselves.

Types of licence

A licensee may take a non-exclusive or exclusive licence from the licensor. The distinction between such licences is both legally and commercially significant.

On a basic level an exclusive licence means that no other person or company can exploit the rights under the patent and this means the licensor is also excluded from exploiting such rights. Exclusivity may be total or divided up by reference to, for example, territory, field of technology, channel, or product type. The extent of exclusivity generally goes to the value of the rights being licensed and will feed into the agreed financials. It is worth noting that the term "exclusive licence" does not have a statutory definition under English law, so it is very important to define the contractual scope of exclusivity in the relevant licence agreement.

In the event a licensor wants to retain the ability to exploit the rights in some way (for example an academic licensor may want the ability to continue research activities) then appropriate carve outs from the exclusivity should be expressly stated in the licence agreement.

A non-exclusive licensee has the right to exploit rights within the patent as determined by the licence agreement. However, the licensor may also exploit such rights as well as granting multiple other licences to third parties (which may include competitors of the original licensee).

Much less common is a sole licence, by which the patent proprietor agrees not to grant any other licences but gives the licensee the right to use the technology and may also still operate the licenced technology itself.

Compulsory licences

A compulsory licence provides for an individual or company to seek a licence to use another's patent rights without seeking the proprietor's consent. Compulsory licences under patents may be granted in circumstances where there has been an abuse of monopoly rights, but are very rarely granted in the UK.

An application for a compulsory licence can be made by any person (even a current licensee of the patent) to the Comptroller of Patents at any time after three years from the date of grant of the patent. In respect of a patent whose proprietor is a national of, or is domiciled in, or which has a real and effective industrial or commercial establishment in, a country which is a member of the World Trade Organisation, the applicant must establish one of the three specified grounds for relief. If satisfied, the Comptroller has discretion as to whether a licence is granted and if so upon what terms. The grounds are:

- demand for a patented product in the UK is not being met on reasonable terms;

- the exploitation in the UK of another patented invention that represents an important technical advance of considerable economic significance in relation to the invention claimed in the patentee's patent is prevented or hindered provided that the Comptroller is satisfied that the patent proprietor for the other invention is able and willing to grant the patent proprietor and his licensees a licence under the patent for the other invention on reasonable terms;

- the establishment or development of commercial or industrial activities in the UK is unfairly prejudiced;

- by conditions imposed by the patentee, unpatented activities are unfairly prejudiced.

The terms of the licence shall be decided by the Comptroller but are subject to certain restrictions on what type of licence can be granted, namely the licence: cannot be exclusive; can only be assigned to someone who has been assigned the part of the applicant's business that enjoys use of the patented invention; will be for supply to the UK market; will include conditions allowing the patentee to adequate remuneration; and must be limited in scope and duration to the purpose for which the licence is granted.

Infringement

The type of licence is also significant when it comes to tackling infringement. Under statute, an exclusive licensee has the same right as the proprietor of a patent to bring proceedings with respect infringement committed after the date of the licence and such proceedings may be brought in the licensee's name (PA 67(1)). An exclusive licensee of a patent application may also bring proceedings in its own name (PA ss. 67(1) & 69). In practice, however, these statutory provisions are often excluded or varied by parties negotiating complex licensing transactions. A licensee may also have a right under a licence to bring proceedings for an infringement occurring before the licence came into effect.

A non-exclusive licensee does not have any right under statute to bring proceedings in its own name. However, this could be negotiated into a licence agreement, though it may be difficult for a licensor to agree this point if it has multiple non-exclusive licensees.

Effect of non-registration on infringement proceedings

There is no requirement that a licence must be registered before proceedings can be commenced by an exclusive licensee. However, non-registration can affect a licensee's ability to recover its costs in relation to such proceedings.

Implied terms

Established rules of construction apply to assignment and licence agreements. Parties should ensure that important terms are included as express terms. There is no implied warranty that any assigned or licensed patent will be valid, or that an assignee or licensee will work the invention (for example, that they will exploit the rights and manufacture products). In certain very limited circumstances a court will order 'rectification' of an assignment or licence agreement, namely a court will order a change in the assignment or licence agreement to reflect what the agreement ought to have said in the first place. Regardless of this, all key terms should be included expressly in all assignment and licence agreements.

Termination of licences

Except where there is express contractual provision or where a licence has been wrongly terminated and damages sought, under English law there is no compensation payable to licensees on termination of a licencing agreement. The licence agreement should be clear as to what circumstances may give rise to termination, for example the non-payment of royalties, material breach or insolvency. The agreement should also make clear what happens in the event of termination in relation to, for example, existing stock of licensed products or work in progress.

Next in our 'The basics of patent law' series, we will be discussing the Unified Patent Court and Unitary Patent system.

Filed under

- Gowling WLG

- Patent infringement

Popular articles from this firm

Have your say on the iaa project list: discussion paper feedback due by september 27, 2024 *, a banker asked us: joint and several guarantees *, bill c-27 timeline of developments *, scc bulletin 19-09-2024 *, judicial review of adjudicator’s determination of “contract completion” pursuant to the construction act *.

Professional development

EPC & MEES Regulations - All You Need to Know - Learn Live

Related practical resources PRO

- How-to guide How-to guide: The legal framework for resolving disputes in England and Wales (UK)

- Checklist Checklist: Considerations prior to issuing court proceedings (UK)

- How-to guide How-to guide: How to assess antitrust law risks in agency and distribution agreements (USA)

Related research hubs

An International Guide to Patent Case Management for Judges

9.3.1 judicial administration structure.

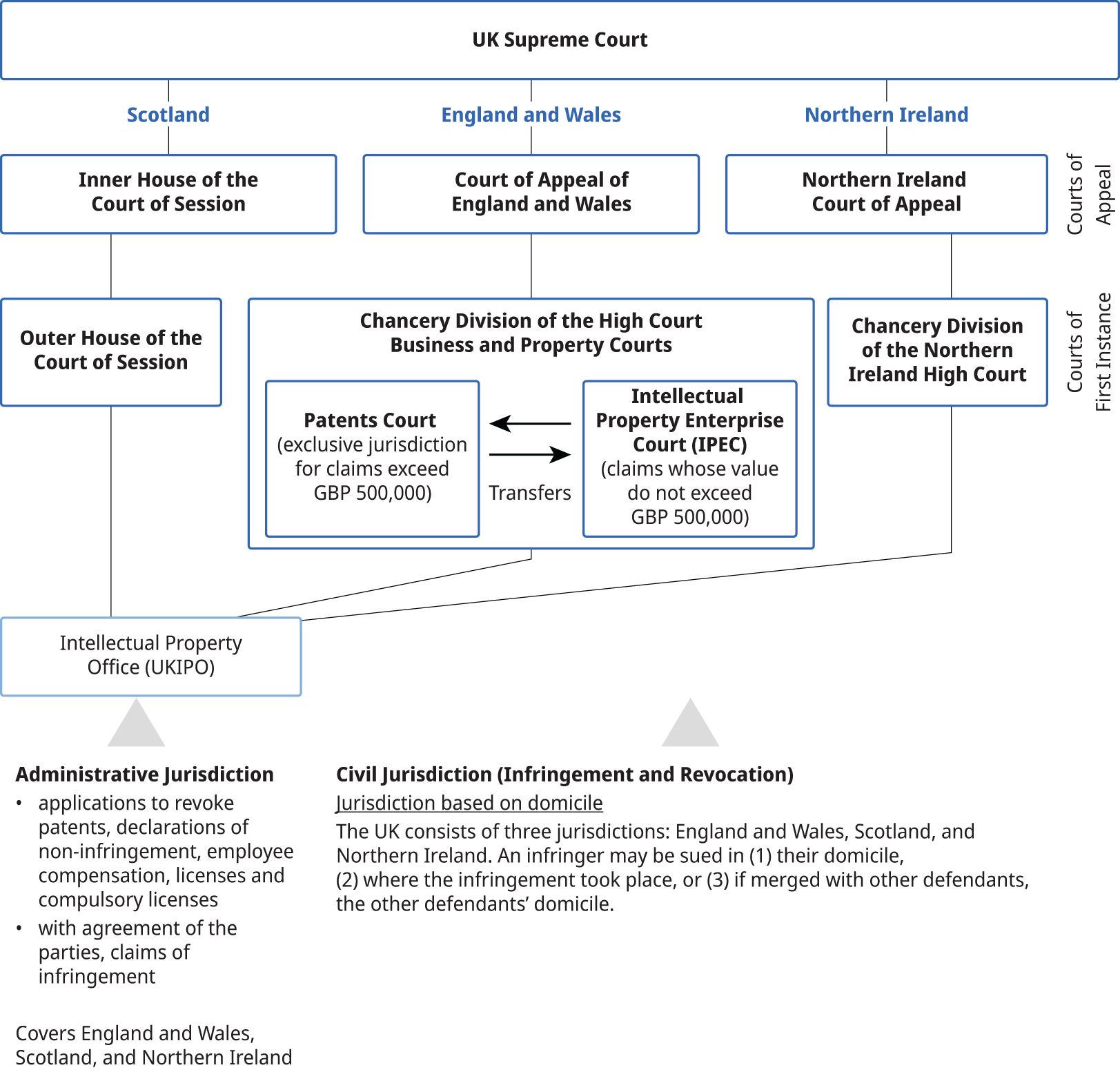

Figure 9.2 shows the judicial administration structure in the United Kingdom.

9.3.1.1 The civil courts and judges of England and Wales

The jurisdiction of England and Wales has two first-instance civil courts: a set of local county courts, which are located in larger towns and cities throughout the jurisdiction, and a national High Court, with its principal seat in London and a series of district registries in major cities. Cases of high value and importance are heard in the High Court.

In all civil first-instance courts, trials are conducted by a single judge sitting alone. The judge is the tribunal of fact and law. Case management is also undertaken by a single judge. In some courts, trials are conducted by judges of a different grade from that of judges who hear trials; in other courts, the judges who hear trials also carry out case management. All patents cases are heard in courts of the latter sort.

Appeals go to the next court in the hierarchy. Appeals from the High Court are to the Court of Appeal, which sits as a panel of three judges. Appeals from the Court of Appeal are to the U.K. Supreme Court.

Judges are recruited from the ranks of qualified lawyers who have been in practice for a substantial time. When a lawyer is appointed as a full-time “salaried” judge, they leave their legal practice. It is also possible for a lawyer to act as a deputy judge as a part-time fee-paid appointment while continuing to work as a lawyer. Today deputy judge appointments are for a limited time so as to allow the lawyer to get a taste of work as a judge and decide if they wish to apply for a full-time post. Full-time judges are only appointed from the ranks of lawyers who have sat as deputies.

Judicial training is conducted at the Judicial College.

9.3.1.2 The Patents Court

The Patents Court is part of the Chancery Division of the High Court and is now organized as part of the Business and Property Courts of England and Wales. It handles most of the patents cases that are brought in the United Kingdom. In England and Wales, it has exclusive jurisdiction over patents cases 34 where the value is over GBP 500,000 and shares jurisdiction with IPEC in cases of a value between GBP 50,000 and GBP 500,000 (or more, if the parties agree). 35

The principal judges of the Patents Court always have extensive experience in patent litigation. The principal judges of the Patents Court, Mr Justice Meade and Mr Justice Mellor, were each in practice at the patent bar for about 30 years before their appointment, handling cases relating to a wide range of technologies. They are supported by five to eight other judges of the Chancery Division who are able to hear patents cases, by the judge in charge of IPEC (currently His Honour Judge Hacon) and by a number of deputy High Court judges (experienced practicing barristers or solicitors who have been appointed to sit as part-time judges). 36

The Patents Court operates a system in which the technical difficulty of the case is rated between one and five, with five representing the most technically complex cases. Only Mr Justice Meade, Mr Justice Mellor, His Honour Judge Hacon or suitably qualified deputy High Court judges are able to hear trials of cases with a technical complexity of four or five. Trials of cases of lower technical complexity and interim applications can be heard by any judge permitted to sit in the Patents Court.

Under Section 70(3) of the Senior Courts Act 1981, the Patents Court has the discretion to appoint scientific advisers. The role of a scientific adviser is to assist the court in understanding the technology and the technical evidence, not to assist the judge in deciding the case. 37 In most cases, the judges of the Patents Court sit without a scientific adviser; it is rarely necessary given their background and the fact that they have the assistance of expert witnesses called by the parties. However, in some cases, scientific advisers have been appointed to assist the trial judge, 38 the Court of Appeal and the Supreme Court (or its predecessor, the House of Lords). 39

The English legal profession is divided into barristers and solicitors. Parties are generally represented before the Patents Court by specialist patent barristers instructed by specialist patent solicitors. There are about 119 members of the Intellectual Property Bar Association of England and Wales, many of whom practice extensively in the Patents Court. There are about 60 members of the Intellectual Property Lawyers’ Association, which principally represents solicitors practicing in intellectual property law in England and Wales; of these, a substantial number are experienced in patent litigation, and some have rights of audience before the Patents Court as solicitor advocates. Parties can also be represented by patent attorneys, either instructing barristers or exercising their own rights of audience.

An individual may also represent themselves as a “litigant in person”, and a company or other corporation may be represented by an employee, provided that the employee has been authorized by the company and the court gives permission. 40

The Patents Court, like the rest of the High Court, operates according to the “overriding objective” of the CPR – namely, that of “enabling the court to deal with cases justly and at proportionate cost.” 41 The CPR explains that

Dealing with a case justly and at proportionate cost includes, so far as practicable: (a) ensuring that the parties are on an equal footing and can participate fully in proceedings, and that parties and witnesses can give their best evidence; (b) saving expense; (c) dealing with the case in ways which are proportionate – (i) to the amount of money involved; (ii) to the importance of the case; (iii) to the complexity of the issues; and (iv) to the financial position of each party; (d) ensuring that it is dealt with expeditiously and fairly; (e) allotting to it an appropriate share of the court’s resources, while taking into account the need to allot resources to other cases; and (f) enforcing compliance with rules, practice directions and orders. 42

This overriding objective has fueled many developments in case management in the Patents Court, and the High Court more generally, aimed at streamlining patent litigation while retaining the core features of the system that enable proper scrutiny of parties’ cases. We address these in more detail in subsequent parts of this chapter, but examples include:

- providing the option for parties accused of infringement to provide a full and accurate product and process description of the alleged infringing product or process, rather than requiring the disclosure of documents; 43

- limiting the disclosure of internal documents that might be said to bear upon issues of obviousness or insufficiency to cases in which such disclosure is necessary to deal with the case justly and proportionately; 44

- introduction of a streamlined procedure (no disclosure or experiments, cross-examination on written evidence only on topics where it is necessary) 45 and the Shorter Trials Scheme (trials to be concluded within four days, disclosure subject to restrictions, evidence and cross-examination restricted to identified issues); 46 and

- expedition of cases where merited, 47 as well as a general intention to bring cases on for trial within 12 months where possible. 48

Appeals from the Patents Court are not available as of right. A party wishing to appeal must seek and obtain permission to appeal, as discussed further in Section 9.8.1 below.

If permission is granted, appeals from decisions of the Patents Court will normally be heard by a panel of three judges of the Court of Appeal. The panel is likely to include at least one of the patent specialists in the Court of Appeal, currently Lords Justices Arnold and Birss, each of whom sat as a judge of the Patents Court for many years following lengthy periods of practice at the patent bar.

If permission to appeal to the Supreme Court is granted (discussed below in Section 9.8.3.2 ), then the case is likely to be heard by five Supreme Court justices, which is likely to include Lord Kitchin, who practiced at the patent bar before his appointment to the Patents Court, then the Court of Appeal and finally the Supreme Court.

In a case in which, while an appeal against the revocation of a patent is pending, the patent proprietor reaches a settlement with its opponent so that the appeal is unopposed, the appeal court will not simply allow the appeal. It will need to be persuaded that the decision to revoke the patent was wrong. In such cases, it is the practice to invite the Comptroller to make such submissions as they think fit to assist the court. 49

9.3.1.3 The Intellectual Property Enterprise Court

Like the Patents Court, IPEC is part of the Business and Property Courts of the High Court of England and Wales. It (and its predecessor, the Patents County Court) was established to improve access to justice in patents cases for small and medium-sized enterprises by providing a forum with streamlined litigation in which a party’s potential liability for the costs of the other party is limited to GBP 60,000. 50 The presiding judge of IPEC is His Honour Judge Hacon, who is a specialist circuit judge. 51 His Honour Judge Hacon is assisted by a number of deputy judges (comprising nominated barristers and solicitors who specialize in intellectual property law). All judges who sit in the Patents Court can also sit in IPEC. IPEC is covered in greater detail in Section 9.9 of this chapter.

9.3.1.4 Scotland

In Scotland, the Court of Session has exclusive jurisdiction in proceedings relating primarily to patents. 52 Chapter 55 of the Act of Sederunt (Rules of the Court of Session 1994) 1994 53 contains specific rules governing the procedure for and case management of all intellectual property cases, including those involving patents. 54 Patents cases are heard by designated intellectual property judges, 55 who are frequently also judges in the Commercial Court. The court aims to ensure, as far as possible, that the same judge is responsible for the management of a case from commencement to conclusion.

Cases are put out at an early stage for a preliminary hearing. 56 At this hearing, the intellectual property judge can make orders that are “fit for the speedy determination of the cause,” such as ordering the disclosure of witnesses or documents or the lodging of expert reports or affidavits. 57 The intellectual property judges also have available to them extended powers that are peculiar to intellectual property cases, such as the power to order the disclosure of information relating to infringement of an intellectual property right. 58

Thereafter, a case is usually set down for a procedural hearing. 59 At this hearing, the judge will decide which issues are to be determined at the substantive hearing of the case, how they will be addressed and may order, for example, the lodging of witness statements, the lodging of documentary and other evidence, and the carrying out of experiments. 60 The breadth of the orders and discretion available to the judges at each stage enables them to achieve both the specific procedure and the type of hearing that are best suited to the resolution of each individual case.

9.3.1.5 Northern Ireland

In Northern Ireland, patents cases are brought before the Chancery Division of the High Court of Northern Ireland. They are case-managed in the same way as other chancery cases. Once pleadings are complete, the case is set down, and it then comes before the chancery judge for case management. Case management involves the legal representatives completing a questionnaire: this deals with interlocutory matters, experts’ reports and meetings, statements of law and fact, details of any alternative dispute resolution, and trial details (e.g., the number of witnesses, estimated length of trial, timetable for skeletons etc.). The judge then reviews the case with legal representatives present, and it is usually listed for hearing after two to three review hearings, depending on how matters progress. Patents cases in Northern Ireland are rare.

Build your custom guide

To create your custom guide, select any combination of the topics and jurisdiction below and then press "Confirm selection".

1. Select topics

2. Select jurisdictions

Update Your Browser

This website is not compatible with Internet Explorer 9 or below, we recommend you update your browser.

Did you know

Old and outdated browser version have security issues and don't follow new web standards. By updating your browser you can element these issues and enjoy a feature rich experience.

Which browser should I choose?

Google Chrome more info | free download

Internet Explorer more info | free download

Mozilla Firefox more info | free download

A guide to intellectual property rights in the UK

The main types of intellectual property (IP) rights in the UK are:

- Trade marks, both registered and unregistered

- Designs, both registered and unregistered

- Trade secrets.

If you are launching a business in the UK, you may well want to consider some or all of these (at least to replicate the protection you have in other territories). Please note that, with effect from the end of the Brexit ‘transition period’ on 31 December 2020, EU-wide rights no longer give protection in the UK and the UK will not be deemed to form part of any relevant EU-wide regime. As noted below, this has particular implications for the UK’s trade mark and registered/unregistered designs regimes.

Burges Salmon can advise you on your UK IP rights and help to guide you through application processes. The information below provides an overview.

Trade marks

Unregistered rights: In the UK, unregistered rights in a brand may be created through use of that brand over time, as goodwill is built in it: this may enable the owner to bring a passing off action to prevent third parties from using an identical or highly similar brand. However, there are disadvantages to relying on this approach – not least its uncertainty and the heavier burden of proof.

Registered rights: I f you are launching in the UK, it is strongly preferable to register your brands as trade marks. This creates both an asset and a clearer right to enforce.

Territory: Trade mark protection is territorial, so that applications need to be filed in each country or territory of interest to a business. This means that even if a company has trade mark registrations elsewhere, e.g. Japan or the USA, these rights will not automatically extend to the UK.

Options: In the UK, there are currently two ways of obtaining registered trade mark:

- a UK national trade mark application; and

- an international trade mark application designating the UK or EUTM.

Please note, Brexit has changed the position vis-à-vis obtaining trade marks in the UK, most notably in respect of EU trade marks (EUTMs). All EUTMs registered prior to 1 January 2021 were automatically ‘cloned’ and recorded as new (and distinct) marks on the UK trade mark register (a ‘comparable UK trade mark’). These new comparable UK marks retained the EUTM filing, priority and/or UK seniority dates associated with the underlying EUTM. In contrast, however, any EUTM applications pending as at 1 January 2021 (and therefore registered after 1 January 2021) were not subject to this cloning process. Owners of any such marks will have a nine-month period within which to register a comparable UK trade mark. Successful applications submitted within this period will retain the same filing, priority and/or UK seniority dates as the original EUTM.

We are happy to advise further on any of these points, including the impact of Brexit.

Clearance Searches: Even if a brand is well established in another territory, it is strongly recommended to conduct clearance searches in the UK before launching or filing a new trade mark application here, to see if there are any earlier trade mark right holders that may object to the application or that you could be infringing by using your brand.

Classes: When you apply to register a trade mark in the UK you have to specify the goods and services that you intend to use the brand for. These are organised into 45 different classes under the Nice classification system. Official trade mark application fees are charged on a per class basis. The UK Intellectual Property Office (IPO) accepts a broader list of goods and services than certain territories, such as the USA, so it is recommended to seek UK counsel input into a trade mark specification even if one has already been prepared and filed in another territory.

Application process: Once a UK application has been filed it will be examined by the UK IPO to ensure that it complies with various registration requirements. The IPO will also conduct a search of the IPO Register for earlier rights they consider to be similar to the mark applied for – the application will not be refused on this basis, but earlier right holders will be notified of the application and it will be for them to take action if they consider there to be a conflict. Assuming there are no major issues during examination, the application will be published for opposition purposes. If no oppositions are filed by third parties the application will proceed to registration and a certificate will be issued. For a straightforward application this process typically takes around four to six months.

Duration of Registration: UK registrations can be renewed every 10 years, for a fee, and can last indefinitely so long as they are used and renewed.

Priority: Once an initial trade mark application has been filed in (almost) any territory the filing date may be preserved for additional applications abroad provided those application are filed within six months. This ability to back-date later applications is known as 'claiming priority' and is useful as it allows time to see how the first application progresses before any investment is made in additional territories, as well as helping to stagger costs. The UK IPO accepts priority claims from earlier applications/registrations, and UK applications can be used as priority applications. Later applications can be made after the end of this priority period, but those later applications will simply be dated at the date of the application.

Marking: The trade mark registration symbol ® must only be used in the UK after a valid UK registration has been obtained. The TM symbol can be used to indicate a trade mark before an application is filed or while it is pending. This applies to use on products or packaging, as well as on a website directed at the UK. See further guidance note on e-commerce.

Other registrations: In the UK, neither simply registering your company name at Companies House nor owning the domain name for your website gives you rights to prevent others using your trade mark. Therefore, it is important that specific consideration of IP protection is given when launching in the UK.

What is protected? Patents can protect inventions which are not yet in the public domain. It is important to keep inventions secret and disclose them only under a Non-Disclosure Agreement in order to preserve the ability to patent them.

Requirements to be registered: Requirements for protection include that the invention is new, something that can be made or used, and not just a foreseeable modification to something already out there. The invention should not be made public before patent protection is sought (and, as set out below, an earlier application in a different country can be publication that prevents a later registration in the UK).

Territorial: Like trade mark protection, patent protection is territorial – so protection in one territory will not protect in another.

Infringement: You should undertake freedom to operate searches before launching an invention in the UK. This is the case even if you have already launched elsewhere (or you already have a patent registered elsewhere), as there may be different patents in the UK which are infringed by your invention.

Timing: Unlike trade mark protection, there is a limited period of time in which to select the countries in which you want to file a patent application. So, if you already have a patent in one territory, it may no longer be open to you to protect the same invention in the UK. Bespoke advice may be required here.

UK Patents: Patents can be registered through the UK IPO (which may be accessed through a European Patent Application (via the European Patent Office) or through an International Patent Application (via the World Intellectual Property Office). Once registered, patents can be renewed (on payment of renewal fees) for up to 20 years.

What is protected? Designs can protect the appearance, shape, configuration or decoration of the whole or part of a product. Requirements for protection include that the design is new, and creates a different overall impression to any earlier design already in the market. The design should not be made public before registration is sought.

Unregistered rights: Unregistered UK 'Design Rights' will arise automatically to protect certain shape and configuration (3D) designs. However, Design Rights provide less protection than Registered Designs and are of shorter duration (for the earlier of 10 years after it was first sold or 15 years after it was created). There are also EU Design Rights (Unregistered Community Designs (UCD)), which are of shorter duration again. UCDs existing before 1 January 2021 automatically retain UK protection as a continuing unregistered design, with protection continuing for the remainder of the three year term that attached to the UCD.

Registered Designs: Designs can be registered through the UK IPO. Before launching or applying to register a design it is advisable to conduct a clearance search. Once registered, designs can be renewed (on payment of renewal fees) every five years for up to 25 years. Since 1 January 2021, EU registered designs (Registered Community Designs (RCDs)) are no longer valid in the UK. Any RCD that existed prior to this date was automatically cloned to allow for comparable UK rights. The comparable right is a fully independent UK registered design capable of being assigned, renewed or challenged separately from the original RCD. By contrast, a comparable UK right was not created for any RCD application that was pending (i.e. not yet registered as an RCD) on 1 January 2021. Applicants in this position have a nine-month period (starting on 1 January 2021) within which they can apply for a comparable UK design right with the same filing, priority and/or UK seniority dates as their original RCD application.

What is protected? Copyright can protect original literary, dramatic, musical and artistic work, as well as software and databases and audio/visual recordings.

Unregistered rights: Unlike trade marks, designs and patents, copyright in the UK cannot currently be registered (so there is no central register and no fee requirement). Copyright arises automatically in the UK as soon as certain requirements are met, including the need for the work to be written down or recorded.

Marking: It is best practice to mark original work with the copyright symbol ©, the name of the author/creator, and the date of creation – not least so (recognising that there is no register) third parties are put on notice that the work is protected by copyright and can trace the copyright owner.

International protection: The UK has signed various copyright treaties which allow the UK to provide copyright protection in respect of copyright protected in other signatory countries. If you have copyright outside the UK, those treaties may operate to provide automatic protection in the UK too.

Trade secrets

Trade secrets can protect business information such as recipes and customer lists. There is not a specific register for this. In the UK these can be protected under the common law of confidence, through keeping the information secret and through only disclosing to those that have signed non-disclosure agreements.

Managing your intellectual property

Audit: You should regularly take stock of your IP assets. This is called an ‘IP Audit’ and it will help in ensuring your IP protection is up-to-date. Burges Salmon can work with you in conducting an IP Audit, and can advise on the scope and status of your current IP portfolio, how it compares to what IP you actually have and use, what further enforceable IP rights you might have, and the best way to protect and enforce those rights.

Licensing and transfer of IP rights: IP rights can be very valuable intangible property assets. The rights can be licensed, transferred, sold, or used to secure investment. For certain IP rights, such as trade marks, it is best practice to record any such licences or transfers on the IPO Register. Please contact the Burges Salmon IP and Commercial teams to discuss your requirements regarding dealing with your IP. See also our note on Contracting Under English Law.

Enforcement: You may also wish to use your IP to enforce your rights against others.

How can Burges Salmon help?

Our highly-acclaimed intellectual property team have formidable expertise, which is acknowledged nationally and internationally. They cover a range of technical, scientific and commercial backgrounds and have an in-depth insight into many industry sectors having worked with multiple high profile global brands. For more information or if you have any questions, please contact the Burges Salmon IP team .

Key contact

Helen Scott-Lawler Partner

- Head of Food and Drink

- Intellectual Property and Media

Subscribe to news and insight

Related news and insights, eu trade marks: are virtual goods similar to their real-world counterparts.

The mere fact that the earlier goods are the real-world counterparts of the contested virtual goods is not sufficient for a finding of similarity

Supreme Court clarifies law on accessory liability in trade mark claims

Deploying ai in the battle against counterfeit goods, mcdonald's big mac - use it (and prove it) or lose it, burges salmon careers.

Our partners and attorneys are highly qualified and highly experienced to advise you in all areas of Intellectual Property law. We advise start-ups, SMEs, and multinational corporations and ensure that your inventions, brands and designs are expertly protected.

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Diversity in IP

- Testimonials

Introduction to UK Patents

What is a uk patent.

A patent is a monopoly right to prevent others from exploiting an invention in a particular country. In the UK, the right is renewable up to a term of 20 years.

A patent does not give the owner the right to exploit the invention. For example, if the patent is for an engine management system and a competitor has an earlier patent covering an engine, a licence may be required to use the engine management system in conjunction with the competitor’s engine. If you have concerns in the area, then you should consider a freedom to operate search.

Should I apply for a patent?

You do not need a patent to exploit your invention, but once you have disclosed your invention publicly, you will no longer be able to gain a valid patent in the UK. We would, therefore, strongly suggest seeking advice, and probably also filing an application, before disclosing your invention publically because it may be your only opportunity to do so.

How do I apply for a patent in the UK?

An application should be submitted to the UK Intellectual Property Office (UK IPO).

Should I Get Professional Assistance?

It is not necessary to have your patent application drafted by a patent attorney, or to have a patent attorney communicate with the UK IPO on your behalf to get that application to grant. The UK IPO offer clear guidance to inventors on their website .

However, drafting a patent application and dealing with the UK IPO through to grant is a complex matter and so we would strongly encourage you to consult with an attorney as early as possible and to consider their professional advice. Our attorneys are highly trained UK and European Patent Law specialists, with expertise in a broad spectrum of science and engineering disciplines.

By way of analogy, you could compare drafting and filing a patent application, and dealing with the UK IPO through to grant yourself with choosing to represent yourself in court. You may be able to achieve a satisfactory outcome by representing yourself in court, but if you were represented by a lawyer, then through their expertise in the field, the final outcome may be considerably better. Similarly, a patent attorney could gain much broader and more robust patent protection for your invention than you may achieve yourself.

Confidentiality

As discussed above, it is important to seek professional advice before you make your invention public. We are bound to confidentiality by virtue of our membership of the Intellectual Property Regulation Board ( click here for the Code of Conduct) and therefore any disclosure made to us in the workplace is confidential and so is not considered a public disclosure.

When should I apply for a patent?

In short – as soon as possible.

The application must be submitted before you make your invention public and, when filed, acts as a ‘flag in the ground’, securing what is called the priority date. Anything published before this priority date anywhere in the world can be used when assessing the patentability of your invention; anything published on or afterward, can not.

At the very latest, a UK application can be submitted on the same day as a public disclosure.

What is in a patent application?

The application comprises a description, appropriate drawings and a set of claims which define the actual monopoly for which protection is sought.

The description should describe the relevant features of the invention in sufficient detail and in a manner clear enough for it to be put into practice by a person knowledgeable in the particular field to which the invention relates.

How is patentability assessed?

In order for an invention to be patentable, there must be some functional (i.e. technical) aspect which is new, or “novel” and inventive and which is not specifically excluded from patentability in the Patents Act.

In the UK, a novel invention is simply one that has not been publicly disclosed anywhere in the world before the filing date of the patent application seeking to protect the invention. Such public disclosure can take the form of a book, magazine, website, journal article, an earlier patent application, prior use or the like.

The novel aspect of an invention is then assessed as to whether it can be considered non-obvious (i.e. inventive) in light of what is already known. This means that if an invention is novel, it still may not be considered patentable because of a lack of inventiveness, for example it is might be considered obvious to modify a known process to arrive at the novel invention.

What is the basic process in the UK and how long does it take?

The typical process is to file a patent application at the UK IPO comprising a description, appropriate drawings and a set of claims which define the invention. The application will then lie dormant until such time as a search request is filed and fee paid. This can be done at any point within twelve months from the initial filing date but must be done by the first anniversary of the UK filing date in order to proceed. A search report will issue approximately 4 to 6 months after filing the search request and will list publications that predate the filing of the application (“prior art”) that the UK IPO examiner considers to be relevant to the patentability of the invention.

The application will publish approximately 18 months from the filing date and six months after publication is the deadline for filing a request for the UK IPO to carry out a substantive examination of the application to determine the patentability of the invention.

A substantive examination report will be issue after the request has been filed (usually at least six months after, and often longer) and this will outline, in detail, any objections the Examiner has to the patentability of the invention and invite the applicant to address these objections within a timeframe of, typically, 4 months.

Examination and amendment proceeds for as long as is required to put the application in order for grant, up until the compliance deadline of 4 ½ years from filing or 12 months from issuance of the first substantive examination report (whichever is later).

Deadlines can typically be extended should the applicant require more time and an application can typically be restored should the applicant unintentionally miss a deadline.

How much does it cost?

The cost to prepare and file a UK patent application can vary significantly. Typically the cost of preparing and filing a UK patent application can cost between approximately £5000 and £10,000 (plus VAT). Depending on whether objections are raised, and the complexity of the technology, the overall cost for prosecuting a typical UK application to grant following the initial application can be very low (less than £1000 +VAT), but for a typical case it is likely to be in the region of £3000 to £6000 (plus VAT). As noted above, these figures are estimates only and will vary depending upon the complexity of the idea and the ease or otherwise with which the prosecution through the Intellectual Property Office proceeds. In particular, if there are significant objections raised by the UKIPO during the prosecution procedure then the time taken to deal with those issues will likely increase the overall cost.

Can I speed things up?

There are a number of options available to us in order to expedite prosecution and it is possible to obtain a patent in well under a year.

The UKIPO guide to getting your patent granted more quickly is here: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/patents-fast-grant .

You should, though, consider whether expedited prosecution is the best path for you to take. Expediting prosecution will bring forward the date by which costs are incurred and, although provisional protection for your invention will start from the date the application is published, early publication will put your competitors on notice as to your activity. You may wish to plan the commercialisation and marketing of your invention whilst your patent is pending and has not been published.

Furthermore, if you make improvements to your invention you should discuss with your attorney as it may be easier to patent these improvements if a further patent application is filed before your original patent application publishes.

How do I minimise the preparation and filing cost?

We can minimise costs in a number of ways, for example:

- Filing only a description initially and filing the claims to the invention by 12 months later.

- Waiting until 12 months from filing the application to submit the search request.

- Having the applicant provide as much information as to the technicalities of the invention as well as details of any similar ideas which are known to be available already.

I’ve disclosed my invention to others – what should I do?

Please let us know exactly what has been disclosed, where and to whom. Disclosures must have been ‘made available to the public’ so confidential disclosures are not prejudicial to novelty.

Please note that for matter to be deemed ‘made available to the public’ it does not require that the public became aware of the matter as a result, for example a book on a library shelf is disclosure whether the book was read or not. However, the disclosure must be enabling, i.e. enough information must have been revealed to enable a person in the relevant field to replicate the invention. Public use of an invention is not necessarily an enabling disclosure.

I’ve made some improvements since I filed – what should I do?

As touched on above, you should inform your advisor as soon as you make any improvements to your invention. They can then assess whether these improvements fall within the scope of protection applied for in your patent application. It may be that a further application is required and that your original application can be allowed to lapse.

Will my UK patent application protect me overseas?

Yes, but only in a limited number of countries.

A patent is a monopoly right specific to a particular country. A UK patent provides a monopoly right in the UK and can be extended, by registration after grant, in a number of different countries. The full details can be found here .

The filing of a UK patent application also secures an option on filing outside of the UK for a period of twelve months. As long as an application to afford protection in overseas territories is filed within twelve months of the initial UK filings, those applications will be treated as if they had been filed on the same day as the initial UK filing.

A UK patent application can also be registered in Hong Kong. The registration is a two-step process requiring a first step to be taken within six months of publication of the UK application and the second to be taken within six months of grant. This gives rise to a Hong Kong patent based on the UK patent.

How can AA Thornton help?

If you are interested in discussing any of the above with an attorney, or have any questions, we would be happy to help.

We offer a free 30 minute initial discussion for new clients with a qualified attorney, during which you would talk through your invention in detail and we would discuss with you our thoughts on patent protection, patentability, outline the patent procedure to you and when you can expect to incur costs, and offer our advice as to how best you should proceed. We would be happy to arrange such a discussion with you.