Science Connected Magazine

Science Literacy, Education, Communication

How the History of Littering Should Impact the Solution

Littering has wreaked havoc on ecosystems all over the world. What do we do now to amend the global problem of chronic waste?

By Emily Folk

A single plastic bottle can take up to 450 years to degrade.

Today, we know the impact littering has on our environment and human health. With access to the Internet and social media platforms, we witness the havoc pollution has wreaked on ecosystems all over the world. Solving the littering issue can seem like an insurmountable challenge. However, there are ways to amend the global problem of chronic waste, even though it may initially seem overwhelming.

Kids learn the definition of a “litterbug” starting in elementary school and receive regular reminders not to throw trash on the sidewalk. For decades, the conversation around litter points the finger to the consumer—the person throwing trash out their car window or tossing food wrappers in the park.

When finding a solution to littering, we need to examine its history. Discussions for the past few decades have placed the responsibility of preventing litter on the individual. In actuality, much of the blame goes to the industries that create waste in the first place.

Litter isn’t the problem. It is simply a by-product of a convenience-oriented economy. If you look at the history of litter, there remains one constant. Production of trash, including plastic packaging and aluminum cans, has continued to grow. Despite efforts to reduce waste and promote recycling, corporations like Coca-Cola continue to produce plastic pollution at an unsustainable level.

Litter would not exist if it were not for the businesses that created disposable packaging and capitalized off their invention. The primary anti-litter campaign, Keep America Beautiful, was founded by the very companies producing the waste.

Sustainable solutions to litter involve looking at the role of the packaging and bottling industry. To truly put an end to littering, we need to put more accountability on corporations to reduce the amount of waste they create in the first place.

The Keep America Beautiful Campaign

Keep America Beautiful is perhaps the most well-known anti-litter movement in the United States. Founded in 1953, this organization works to inspire and educate people on improving their communities. Today, it leads initiatives such as the Great American Cleanup and America Recycles Day.

Volunteer efforts funded by this organization are significant in slowing environmental harm. Annual events take place all across the country. The collective effort results in an impactful reduction in waste pollution in public places and along roadways.

However, most people are unfamiliar with the organization’s origin. When states began responding to the litter problem, the packaging and beverage industry worried the message would undermine their business models. Their profits demanded disposable cans and food packaging. So they founded Keep America Beautiful, which put the litter problem back on the people and out of the hands of corporations.

The packaging industry relied on convincing people they needed to buy more stuff and that these items would undergo a cycle of becoming trash almost immediately. Society had to be trained to dispose of single-use plastic. The bottle and can industry used the power of advertising to convince consumers that the things they were reusing, like glass bottles, were garbage.

The Recycling Movement

Following the rise of disposable products, advertisers convinced Americans they needed convenience above all else. In the post-World War II era, marketers sold the American society the idea of microwaveable dinners they could consume in front of the TV. These companies also marketed plastic soda bottles that did not require reuse. In the 1970s, consumers became increasingly uncomfortable with the amount of waste sent to landfills.

In response, Keep America Beautiful founded another organization, the National Center for Resource Recovery. With serious lobbying efforts, this initiative persuaded state legislators to favor recycling over reusing or reducing consumer goods. The Container Corporation of America invented and funded the phrase “reduce, reuse and recycle.”

By creating the recycling movement, corporations extended their influence across all levels of policy development. Most notably, they actively limited policies that would require corporations to take responsibility for their own waste management. Between 1989 and 1994, Keep America Beautiful spent over $14 million in lobbying efforts to limit recycling policies and let consumers bear responsibility.

The recycling movement has a dirty secret, too. For decades, anti-litter advertisements, including Keep America Beautiful’s infamous “Crying Indian” PSA video, have distracted consumers from making a real impact. Today, people are well-aware that recycling doesn’t always work. Corporations benefited from the recycling industry’s inefficiency, setting up recycling initiatives to fail from the beginning.

Most of the recycling collected by municipalities in the last thirty years has been shipped to China, where it was most often dumped into the ocean or added to landfills with little to no environmental standards.

Littering Corporations and the Circular Economy

The contemporary equivalent of the first anti-litter campaign is the corporate standard of a circular economy. Circular economies keep products and materials in continuous use, extending their lifetime and reducing the amount of waste generated from the system as a whole. Also referred to as a closed-loop system or cradle-to-cradle, the concept is only successful if it radically changes consumerism on a global scale — instead of making more plastic out of recycled materials.

If you look at the fashion industry, companies like H&M are making sustainability efforts that drastically overstate their ability to combat pollution. Creating clothes out of recycled materials may sound like a great idea, but if the growth potential remains the same, the impact does not change.

According to a study conducted by Greenpeace, Coca-Cola generates over 100 billion plastic bottles annually. A so-called circular economy may devolve into a form of greenwashing that enables unsustainable business models to persist without making real change. There is a real concern that the concept of a circular economy may award companies for their “sustainability” efforts while simultaneously allowing them to continue polluting at the same rate.

Recently, Coca-Cola has also announced a new initiative, launching their campaign of Coke bottles consisting of plastic from the sea. This concept might seem more optimistic if it were not for the fact that they are largely responsible for the plastic being in the sea in the first place. While the concept of a circular economy is promising, the way companies implement it will ultimately make the most significant impact.

Littering and the Individual

Modern consumers are demanding transparency. More so than ever before, buyers are supporting companies that engage in sustainable practices. People are increasingly aware that recycling is not a single solution. Lifestyles that advocate for buying less, like minimalism, are becoming mainstream. The solution to the worldwide littering problem is to hold corporations responsible for the waste they create. By advocating for smarter consumption, individuals can make a big difference in how materials become trash.

Buyers are widely knowledgeable of the impacts of waste pollution and are making efforts to ensure waste is handled more sustainably. City-wide green initiatives reduce litter and encourage recycling. Online companies promote the purchasing of secondhand products like clothes.

Individuals are managing their waste better while also holding the companies that create trash accountable. Organizations like Keep America Beautiful have helped in cleaning up the U.S.’s public places, sidewalks and roadways. Now it is time for them to take responsibility for the waste they generate before it reaches the consumer.

This article was originally published in the Conservation Folks blog on June 19, 2020.

Featured photograph provided by Boyce Duprey .

About the Author

Emily Folk is a sustainability and green tech writer. Her goal is to help people become more informed about the world around them and how they fit into it.

- Announcements

Sustainable Forestry

Rural development & climate smart agriculture.

- Waste Management

Responsible Mining

Wash (water, sanitation and hygiene), social entrepreneurship for green growth, georgia climate action program, climate change & drr.

- Policy & Institutions

- Publications

- Recycling Companies

- International Practice

Reasons, Consequences and Possible Solutions of Littering

- National Plastic Waste Management Program

- The Amount of Plastic Waste Worldwide

- Seasonal Study of the Morphological Composition of Solid Municipal Waste in Shida Kartli Region

- Seasonal Study of the Morphological Composition of Solid Municipal Waste in Kakheti Region

- Seasonal Study of the Morphological Composition of Solid Municipal Waste in Adjara AR

- The Circular Economy – Concept and Facts

- The Circular Economy – Implementation

- Guidelines for the Industrial Production of Biodegradable and Compostable Bags by an Existing Facilities in Georgia on the Example of Ltd. Zugo

- Guide to Hosting Low Waste Events

- WMTR - EPR Policy Options for Beverage Producers in Georgia

- Technical Regulation of the Government of Georgia - On Regulating Plastic and Biodegradable Bags

- Municipal Solid Waste Composition Study Methodology

- General Methodology for Establishing Tariffs and Cost Recovery System in Georgia

- Sustainable Consumption of Printing Paper

- Improving Thermal Insulation Through the Use of Plastic Waste

- Is there any potential for waste recycling in Georgia?

- Municipal Waste Management Plan Development Guideline

Littering can be defined as making a place or area untidy with rubbish, or incorrectly disposing waste. Littering causes pollution, a major threat to the environment, and has increasingly become a cause for concern in many countries. As human beings are largely responsible for littering, it is important to understand why people litter, as well as how to encourage people not to litter. This paper explores the reasons and consequences of littering and suggests possible solutions based on international experience.

Why do people litter?

Laziness and carelessness have bred a culture of habitual littering. Carelessness has made people throw rubbish anywhere without thinking about the consequences of their actions. Many people do not realize or underestimate the negative impacts of littering on the environment. People believe that their individual actions will not harm society as a whole. As a result, it is common to see people throwing wrappers, cigarette butts and other rubbish in public areas. The majority of people believe that there are others who will clean up after them and consequently, the responsibility of cleaning up litter usually falls on local governments and taxpayers. Thus, the lack of responsibility to look after public places is another problem.

In Georgia, many residents living in urban areas blame the lack of public trash cans for widespread littering in the streets. Several studies have proven a correlation between the presence of litter in a given area and the intentional littering of that particular spot. [1] When a person sees litter accumulated in one place, it gives the impression that it is somehow acceptable to litter there. This, along with the absence of appropriate local waste services, might be one of the main reasons behind illegal dumping in Georgian villages.

Consequences of littering

Litter adversely affects the environment. Littering along the road, on the streets or by the litter bins, toxic materials or chemicals in litter can be blown or washed into rivers, forests, lakes and oceans, and, eventually can pollute waterways, soil or aquatic environments. Based on recent data, 7 billion tons of debris enter the world’s oceans annually and most of it is long-lasting plastic. [2] Litter also reduces air quality due to the smell and toxic/chemical vapor emanating from the trash. A polluted environment can encourage the spread of diseases. Toxic chemicals and disease-causing microorganisms in the trash may also contaminate water systems and spread water-borne diseases which can negatively affect the health of both animals and humans if unclean or untreated water is consumed.

Cigarette butts take a grand total of ten years to decompose because of cellulose acetate, contrary to the common perception that cigarette butts decompose very quickly in only a matter of days. [3] In reality, cigarette butts are a serious threat to the environment, as they contain toxic substances like arsenic which can contaminate soil and water.

Plastic litter is another threat to the environment and its inhabitants. It has often been mistaken for food by both land and marine wildlife. When consumed by animals, they reduce the stomach capacity since they cannot be digested. In the long-term it affects the animals’ eating habits, eventually killing the animals. Much of marine wildlife including birds, whales, dolphins and turtles have been found dead with plastic and cigarettes found in their stomachs. [4] An estimated 100,000 sea mammals are killed by plastic litter every year. [5] Some of the materials may also be poisonous or contain sharp objects therefore damaging the animal’s vital organs or severely injuring them. Another negative aspect of littering is that it is too expensive for a country, society and individuals. Cleaning up litter requires a huge amount of money that is financed by taxpayers that could be used in more productive ways. Littered places are visually displeasing and they depreciate the aesthetic and real value of the surrounding environments. Places with large amounts of litter are often characterized with homes and property that are less valuable as a result. Similarly, it affects tourism as it makes city areas and roadsides look disgusting and tourists tend to avoid staying and even visiting areas that are littered. Furthermore, littering can lead to car accidents. Some trash in the road is enough to create a dangerous situation that could result in serious injuries or death.

The ideal way to handle the problem of littering is for each member of society to take responsibility and try their best to properly dispose waste. If citizens are required not to litter, appropriate conditions must be provided by local governments. Measures must be taken by appropriate local authorities to ensure more garbage bins are installed in various areas for effective garbage disposal. Installing enough garbage bins in town centers, walking routes, public areas, and near bus stops as well as fast-food restaurants offer convenience in disposing and collecting litter. To avoid additional problems due to overfilling, the bins must be emptied regularly.

Unfortunately, the existence of garbage bins do not guarantee that waste will not be dropped in the streets. Enforcing strict litter laws will encourage people not to litter in private and public places. Such laws work towards prohibiting illegal dumping and littering.

According to research conducted by the 2011 Keep Britain Tidy campaign, attitudes concerning enforcement are greatly shaped by the degree to which an individual sees it as a threat and many do not think it is likely they will be fined for environmental offences. The same research also reports that people who have seen or heard about fixed penalty notices being issued are less likely to litter. [6]

Littering penalties and other enforcement measures are common practices worldwide. For instance, the penalty for the first case of littering consists of fines from $100 to $1000 and at least eight hours of community service litter cleanup in California. For subsequent offenses, fines and the duration of required community service increases. In Louisiana, intentional littering can result in a one-year suspension of your driver’s license or imprisonment for up to 30 days in addition to standard fines and community service. [7] According to the Code of Waste Management, adapted in 2015, penalties for dropping municipal waste in the street varies from 80 to 150 GEL in Georgia. The Department of Environmental Supervision, Ministry of Internal Affairs and the local self-governments are the responsible institutions responsible for executing the law and violators are fined systematically by the appropriate institution. However, authorities cannot fine someone unless they actually see them litter and it is impossible to control every street.

Undoubtedly, penalties have a real effect on littering behavior, but education and raising awareness is crucial in guaranteeing long-term results. Community clean up events can be an effective way for spreading anti-litter messages in society. The issue can also be incorporated in bulletin boards, TV programs, social media platforms, and newsletters in a more intensive way in order to spread the message widely. Furthermore, an anti-littering sign might be placed in highly littered areas such as the streets near public transport stations. These signs serve to constantly remind people that littering is a bad thing that should be avoided.

Some people argue that not only penalties but rewards also might be a good idea. People “caught” doing the right thing may be given rewards like shopping vouchers and their positive disposal behavior publicized in the media or social networks to encourage others to dispose of litter properly. [8]

[1] What is Littering? Conserve Energy Future. Rachel Oliver.

[2] Walking Green: Ten Harmful Effects of Litter, Green Eco Services, Cathy, 2008.

[3] Twenty Astonishing Facts About Littering, Conserve Energy Future, Rinkesh, 2018.

[4] What is Littering? Conserve Energy Future, Rinkesh.

[5] Walking Green: Ten Harmful Effects of Litter, Green Eco Services, Cathy, 2008.

[6] The Effectiveness of Enforcement on Behavior Change, Keep Britain Tidy, 2011.

[7] States with Littering Penalties, National Conference of State Legislatures, 2014.

[8] Why do People Litter? Litterology, Karen Spehr and Rob Curnow, 2015.

If you are not sure you need a printed version of this page, please don't print it - consider the environment! The planet will hug you for that.

Thank you for your subscription !

Sorry � such e-mail already exist in the mailing list. Please contact us

Please choose one of the following :

Subscribe to our mailing list

Subscribe to our newsltter to receive latest updates from us.

Social Media

Engage with us on following social media channels.

Causes, Problems, and Possible Solutions To Stop Littering

Litter is any trash thrown away in small amounts, especially in places where it doesn’t belong .

Now, with time, litter heaps up, forcing municipalities to spend millions of dollars annually in cleanup costs.

But it’s not just about the costs — litter, generally, portrays a bad picture of an area, turning what was initially beautiful into an unsightly place.

The most frequently littered items include fast food packaging, cigarette butts, used drink bottles , chewing gum wrappers, broken electrical equipment parts, toys, broken glass, food scraps , or green waste.

In other words, litter includes any item not disposed of properly. While not many people fully understand the repercussions of littering , it’s a dangerous practice and should not be taken lightly because it impacts the environment in multiple ways.

Littering is a crime, but they are not enforcing the law. We need to educate the youths on why littering is bad and the effect litter has on neighbourhoods. ~ Johnnise Downs

To better understand littering, here is a list of its causes, problems, and possible solutions.

Various Causes of Littering

The consequences of littering are far-reaching, impacting wildlife, ecosystems, public health, and the overall aesthetic appeal of our surroundings. Addressing the causes of littering is essential for preserving the cleanliness and sustainability of our planet.

The following are the major causes of littering in our society.

1. Presence of Litter in an Area

Research has proven a correlation between the presence of litter in a given area and the intentional throwing of litter at that particular spot.

The research points out that when someone sees litter already accumulated somewhere, it gives him the impression that it’s the right place to discard items. In most cases, it’s either accidental or intentional.

2. Construction Projects

Some percentage of litter also comes from construction projects. The workers’ lunchtime waste and the uncontrolled generation of building waste are the culprits of the litter produced by construction projects.

Pieces of wood, metals, plastics, concrete debris, cardboard, and paper are some of the common waste materials generated.

3. Laziness and Carelessness

Laziness and carelessness have bred a culture of habitual littering . Typically, people have become too lazy and unwilling to throw away trash appropriately.

It is common to see people discard trash out of their kitchen windows or balconies, probably because they are too lazy to put it in the rightful places. Carelessness has also made people throw rubbish anywhere without even thinking about it.

4. The Belief That There is no Consequence For Littering

Since people perceive no consequence for their actions when they throw items anyhow and anywhere, it has created the “ I don’t care attitude.”

Pedestrians getting rid of chewing gum wrappers and other waste on the roadways and streets or motorists throwing garbage from their cars reveals this attitude.

Most people believe others will pick it up or clean it up.

5. Lack of Trash Receptacles

Many passengers, pedestrians, and people living in urban areas have blamed rampant littering on the lack of public trash cans .

Some places have them, but they are not enough, while some of the existing ones are sometimes poorly managed, which leads to overloading of the containers. Besides, animal scavengers and blowing wind can dislodge the items and scatter them around.

6. Improper Environmental Education

Many people do not know that their various acts of littering negatively impact the environment . As a result, people continue to throw litter anywhere without considering the environmental consequences.

Smokers, for example, are unaware of the environmental impact of their aimlessly throwing cigarette butt . The case is similar for passengers, pedestrians, and people who aimlessly throw wrappers or other used items in remote or public areas.

7. Low Fines

The fines for littering in many countries are quite low; to some, fines are not provided. Since people do not expect to get fined, they usually stick to their littering behavior.

For example, it is common for people to throw their cigarette butts and not care about this behavior as they are never fined.

8. Pack Behavior

As per psychology, it is human nature to get affected by the people we spend time with, even unconsciously.

Thus, if we spend time with stubborn people, unwilling to change their behavior, immature, or lack awareness of their actions that adversely affect the environment or are selfish enough to care for the environment and litter quite frequently, we are also more likely to start littering.

Serious Problems With Littering

The consequences of littering emphasize the critical effects of this problem on the environment and the well-being of our planet and all its inhabitants.

They include;

1. Can Cause Physical Harm or Injury to People

Litter can contain objects that can harm or cause physical injury to people or animals, namely needles, blades, or broken glass.

Rowing cigarette butts in the forest can also spark fires, destroy nearby properties and homes, or even kill those trapped in the fire.

2. It Can Facilitate the Spread of Disease

Littering can encourage the spread of pest species and diseases. Trash can provide a breeding ground for diseases and pass them through animals that eat them.

If the trash collects water, it may also harbor mosquitoes known to spread the deadly malaria disease in tropical regions.

Toxic chemicals and disease-causing microorganisms in the trash may also contaminate water systems and spread water-borne diseases, which can negatively affect the health of animals and humans if unclean or untreated water is consumed.

3. Pollutes the Environment

Litter adversely affects the environment . Be it littering along the road, in parks, on the streets, or by the litter bins, toxic materials or chemicals in the litter can be blown or washed into rivers, forest lands, oceans, lakes, and creeks and eventually pollute the waterways , land, forest areas, soils or aquatic environments.

Cigarette butts, for instance, contain toxic substances like arsenic , a well-known carcinogen of the liver, skin, lungs, and other body organs that also contaminate soil and water. The Great Pacific garbage patch is another example connected to marine plastic pollution .

Litter can also reduce air quality due to the smell and toxic/chemical vapor emanating from the trash.

4. High Cleanup Costs

Millions of dollars are spent by municipalities annually on cleanup efforts to reduce littering. This makes littering a huge problem because the money that would otherwise be used in progressive development is partly directed to waste management programs.

Litter can also block stormwater drainage systems and cause urban flooding, which requires money for intervention and restoration.

5. It Affects and Can Kill Wildlife

Plastic litter is often mistaken for food by land and marine wildlife, such as herbivores, sea birds, turtles, and fish.

When consumed by the animals, litter reduces their stomach capacity since it can’t be digested. In the long term, it affects the animals’ eating habits, eventually killing them.

Several marine wildlife, including birds, whales, dolphins, and turtles, have been found dead with plastics and cigarettes in their stomachs. Some of the materials may also be poisonous or contain sharp objects, thereby damaging the animal’s vital organs or injuring them.

6. Affects Aesthetic Value and Local Tourism

Littered places look gross and depreciate the aesthetic value of the surrounding environments. Similarly, it affects local tourism by making city areas and roadsides look disgusting.

The public and tourists also avoid littered areas because of health issues and unattractiveness. It also causes visual pollution and affects people’s quality of life.

7. Increased Probability of Fires

People often underestimate the underlying dangers of their behavior that littering may also contribute to fires. They throw away their cigarettes wherever they stand and risk sparking wildfires in areas at high risk for wildfires because of dry wood.

They hardly believe that a cigarette could be enough to start a fire. Therefore, littering can increase the probability of wildfires.

8. Breeding Ground for Insects

Litter can serve as a breeding ground for insects or pests. If it is organic litter, it can be quite harmful as insects and other pests prefer to breed on organic substances.

But that’s not all — littering can also lead to an increase in the population of undesirable insects, which obviously isn’t very good for both human and crop health.

9. Soil Pollution

Soil pollution is among the adverse effects of littering. Litter consists of several materials like glass, metal, and organic stuff and can also contain hazardous materials.

One example is batteries. As batteries contain many harmful substances, they may severely pollute the soil if disposed of improperly into the litter.

The soil is likely to store harmful substances, contaminating groundwater since the harmful substances are washed through the soil during rainfall.

10. Water Pollution

Littering can contribute to water pollution in several ways. When people dispose of their garbage directly into the water, rivers, and lakes can be polluted.

Additionally, water pollution includes the contamination of groundwater when garbage is washed into it due to natural rainfall. This garbage is likely to end up in our oceans eventually.

11. Air Pollution

People often burn litter to get rid of it. However, in the combustion process, the harmful substances contained in the litter mix with the air and lead to air pollution.

This problem becomes severe, especially when it comes to the burning of plastic , which leads to the emission of many toxic gases and particulate matter that can negatively affect the human respiratory system.

Possible Solutions to Littering To Save Our Environment

Addressing the problem of littering requires proactive solutions that promote responsible behavior and effective waste management. Developing sustainable practices is key to finding long-term solutions that ensure cleaner and healthier surroundings for present and future generations.

Below is a discussion of these solutions to littering that we can apply to save our environment.

1. Litter Laws

Strict litter laws ensure no litter is discarded, thrown, or dropped in private or public areas. Such laws work towards prohibiting illegal dumping and littering .

The law must also clearly stipulate that dumping is a serious offense, punishable by serving a jail term and fines.

Several local authorities globally have considerably addressed the littering problem by instituting legislation punishing perpetrators with fines , imprisonment, and community service.

2. More Controlling Instances

Littering is mostly not controlled and fined appropriately because there is a lack of controlling instances or people who can control littering.

People know they can get away with littering, and nobody is ready to fine them. However, they can be stopped from littering by increasing the number of people engaged in controlling and fining litter.

3. Anti-litter Campaigns

Community programs and groups should be created with friends and neighbors for neighborhood cleanups with the sole aim of running anti-litter campaigns to raise awareness.

“ Keep the environment tidy ” programs and community cleanup events can be fun and sufficiently valuable in spreading the message.

The campaigns can also be incorporated into bulletin boards, social media platforms, and newsletters to spread the message widely.

Campaigns speak a lot and provide relevant knowledge about the environmental costs of littering, eventually addressing some of the major problems.

In supporting this initiative, more than half of smokers say that if they know how their behavior impacts the environment , they will strive to correct it.

4. Stop Littering Signs

Putting up signs is a very creative way of putting a stop to littering. The signs should be placed in highly littered areas and those prone to littering, such as the streets near public transport stations.

Routes used daily by pedestrians and commuters also deserve “ stop littering signs ” to constantly remind people that littering is a bad thing and should thus be avoided.

5. Putting up Litter Bins

Proper measures must be taken by the relevant local authorities to ensure more garbage bins are installed in various areas for effective garbage disposal .

Putting up enough garbage bins in town centers, walking routes, public areas, near bus stops, and fast-food restaurants offers convenience in the disposal and collection of litter.

Litter bins also help ease the recycling and reuse initiatives as the local authorities and garbage collectors are given enough time to sort the waste.

Moreover, the bins must be emptied regularly to avoid additional problems due to overfilling.

6. Education

Education is crucial to mitigate the littering issue. People need to know how their actions in their daily lives affect the environment.

We also have to make people understand that it is quite easy to avoid littering and thus contribute to protecting the environment.

7. Involve Children and Youth

This education should begin in schools because children and youth play an important role in shaping and keeping a nation clean and beautiful.

Children are good learners and adjust their behavior more easily than most adults.

Moreover, children may convince their parents to avoid littering. Additionally, when they grow up to be aware of the littering problem, they may be motivated to take measures to mitigate it.

8. Recycling of Waste

Recycling can prevent resource waste, and it is possible to reuse many things thrown in the garbage. The local community and the environment can benefit from recycling materials instead of littering.

It saves natural resources , landfill space, energy, clean air, and water and conserves the environment .

9. Carry a Litter Bag

Keep a litter bag in your car, bring it with you whenever you are out, and throw your trash in your bag until you find a garbage receptacle.

This action will not only keep your car clean and organized but also keep the streets clean.

Why Do People Litter?

One of the main reasons why people litter is because they are lazy, careless, and irresponsible. The lack of accountability and responsibility for keeping the planet a clean and habitable place allows them to carry out actions that could destroy it.

Due to ignorance and lack of knowledge about what littering might do to animals, plants, humans, and the whole planet, some people keep doing this bad activity.

Another reason people litter is the lack of trash cans or bins around a certain area. This is still connected to the sense of responsibility and caring as we could always keep our trash in our pockets or bags until we find a trash bin.

However, putting trash cans or bins in public areas would help reduce littering by a mile.

If irresponsible and careless people were punished or fined severely for littering, that could probably stop them from doing the bad activity. Due to the lack of strict law enforcement on littering, people keep doing it as if it is not a bad thing, which makes it a reason why people litter.

Furthermore, people usually litter in areas that are already filled with trash . People litter in areas covered in garbage, thinking that the area is a big trash bin. Bearing this in mind, keeping our areas clean could also stop littering.

Lastly, people litter due to an unwillingness to change their bad behavior. Many people are stubborn and don’t like listening to knowledgeable people about certain actions that could help the planet.

Even if some experts show them the facts and try to make them understand completely, some people do not want to listen and keep doing what they think is fine and right.

This is a painful reality that the people who care about the planet face every day.

Why Should We Stop Littering?

Some of the reasons we should stop littering are that it causes air, land, and water pollution; it kills animals and plants; and it is a means by which diseases keep spreading.

Littering causes air, land, and water pollution as the trash that people randomly throw away in the environment is full of chemicals and microparticles that are not natural in nature.

These chemicals are penetrating the soil and water, which could cause the destruction of nature and later on affect animals, plants, and humans.

Other than the affected land and water, littering also pollutes the air. The toxic emissions from burning litter could contribute greatly to ozone depletion and global warming.

Furthermore, it could cause respiratory problems in both animals and humans. If that’s not enough reason to stop littering, there are more.

In connection to the pollution caused by littering, the longevity of our environment is affected by this bad activity, which would lead to the killing of wildlife. Due to people’s litter, animals, especially the aquatic ones, eat the trash, which could kill them.

Aside from that, the water and air being filled with chemicals could cause many health problems for animals and suddenly lead to their deaths. Due to irresponsible littering, wildlife is becoming at stake.

Lastly, we should stop littering because it is a means for diseases to keep on spreading. Areas filled with litter allow bacteria, viruses, and parasites to reproduce.

As they continuously grow in number, it is easier to get in contact with the germs after picking them up or touching them. Other than that, insects from the area could transmit the bacteria to humans.

There are lots of reasons why we should stop littering and keep our planet clean and healthy.

Always be responsible and careful with your actions so that we can all live healthily and peacefully.

About Arindom Ghosh

A professional writer, editor, blogger, copywriter, and a member of the International Association of Professional Writers and Editors, New York. He has been part of many reputed domestic and global online magazines and publications. An avid reader and a nature lover by heart, when he is not working, he is probably exploring the secrets of life.

Interesting Posts You May Like...

Are Zoos Really Ethical? Insights From The 2 Sides of The Debate!

How To Dispose of Broken TV Sustainably?

20+ Things That You Shouldn’t Buy as an Environmentalist

The 8 R’s of Sustainability: True Environmental Stewardship

Pros and Cons of a Heat Pump

Pros and Cons of Tiny House Living

- Species We Protect

- Anti-Poaching Unit

- Mounted Anti-Poaching Units

- Anti-Poaching

- Ranger Training

- Counter Wildlife Trafficking

- Wildlife Corridors and Habitat Expansion

- Professional Development

- Eco-tour Safaris

- GCF Online Store

- GCF Bonfire Shop

- Upcoming Events

- K9 APU Wishlist

- APU wishlist

- Collaborations & Partnerships

The Effects of Litter on the Environment and Communities

In addition to being unsightly (Pandey, 1990), litter causes a plethora of environmental and social problems (Schultz et al., 2013). When trash and pollutants are washed into storm drains, it flows into our waterways and is distributed into streams, rivers, lakes, and oceans (Stormwater Litter and Trash, n.d.; Roper & Parker, 2013; Corcoran et al., 2009). This harms wildlife and degrades their habitats (Roper & Parker, 2013; Stormwater Litter and Trash, n.d.). Eighty percent of marine pollution can be traced back to sources on land (Nellemann & Corcoran, 2006). Marine organisms are affected by a variety of plastics by getting tangled in it as well as ingesting the plastic (Baird & Hooker, 2000; Blight & Burger, 1997; Corcoran et al., 2009; Mallory et al., 2006; Roper & Parker, 2013; Rothstein, 1973). This is an on-going problem since plastics are continuously deposited on coastlines both from inland and marine sources (Williams and Tudor, 2001). When marine life is exposed to toxins, death may not be imminent, but the toxins accumulate in the organism over its life span (Pearce, 1991). In addition to environmental degradation caused by trash and pollution, there are also repercussions that people experience every day. Some fish and seafood are unsafe to eat, beaches are closed to public access and stormwater drains are clogged with trash and debris which leads to broken pipes and neighborhood floods (Stormwater Litter and Trash, n.d.).

Considering the extensive aesthetic, environmental, and social problems litter causes, conservationists need to determine how to change the global population’s attitudes and behaviors about litter. When Hardin discusses the ‘tragedy of the commons’ (1968) he points out that people consistently do what is in their best interest. People need to be convinced that cigarettes are not only litter but also toxic waste (Rath et al., 2012). The public needs to believe that it is in their best interest to refrain from littering and maintain their property accordingly.

Amy Young Global Conservation Force Project Coordinator, Ecology and Environmental Science M.A. Zoology B.A. Anthropology

Baird, R.W., & Hooker, S.K., (2000). Ingestion of plastic and unusual prey by a juvenile harbour porpoise. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 40, 719-720.

Blight, L.K. & Burger, A.E., (1997). Occurrence of plastic particles in seabirds from the eastern North Pacific. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 35, 323-325.

Brown, B., Perkins, D., & Brown, G. (2004). Crime, new housing, and housing incivilities in a first-ring suburb: Multilevel relationships across time. Housing Policy Debate, 15, 301-345.

Cope, J.G., Huffman, K.T., Allred, L.J & Grossnickle, W.F. (1993). Behavioral strategies to reduce cigarette litter. Journal of Social Behavior and Personality, 8(4), 607-619.

Corcoran, P., Biesinger, M. & Grifi, M. (2009). Plastics and beaches: A degrading relationship. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 58, 80-84.

Finnie, W.C. (1973). Field experiments in litter control. Environment and Behavior, 5, 123-144.

Hardin, G. (1968). The Tragedy of the Commons. Science, New Series, 162(3859), 1243-1248.

Keizer, K., Lindenberg, S. & Steg, L. (2008). The spreading of disorder. Science, 322, 1681-1685.

Mallory, M.L., Robertson, G.J. & Moenting, A. (2006). Marine plastic debris in northern fulmars from Davis Strait, Nunavut, Canada. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 52, 813-815.

MSW Consultants. (2009). National visible litter study. New Market, MD: Author. Obtained November 30, 2014 from: www.kab.org/research09.

National Association of Home Builders. (2009). House price estimator. Available from www.nahb.org.

Nellemann, C. & Corcoran, E. (2006). Our precious coasts-Marine pollution, climate change and the resilience of coastal ecosystems. Norway: United Nations Environment Programme, GRID-Arendal.

Pandey, J. (1990). The environment, culture, and behavior. In R. Brislin (Ed.), Applied cross-cultural psychology, Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE. 254-277.

Pearce, J. (1991). Collective effects of development on the marine environment. Oceanologica Acta, 11, 287-298.

Rath, J.M., Rubenstein, R.A., Curry, L.E., Shank, S.E., & Cartwright, J.C. (2012). Cigarette litter: Smoker’s attitudes and Behaviors. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 9, 2189-2203.

Roper, S. & Parker, C. (2013). Doing well by doing good: A quantitative investigation of the litter effect. Journal of Business Research, 66, 2262-2268.

Rothstein, S.I. (1973). Plastic particle pollution of the surface of the Atlantic Ocean: evidence from a seabird. Condor, 75, 344-345.

Schultz, P.W., Bator, R.J., Large, L.B., Bruni, C.M. & Tabanico, J.J. (2013). Littering in context: Personal and environmental predictors of littering behavior. Environment and Behavior, 45(1), 35-59.

Skogan, W. (1990). Decline and disorder: Crime and the spiral of decay in American neighborhoods. New York, NY: Free Press.

Stafford, J. & Pettersson, G. (2009). Vandalism, graffiti and environmental nuisance on public transport. Literature review.

Stormwater-Litter and Trash. (n.d.). Department of Public Works. Obtained on November 29, 2014 from: www.sandiegocounty.gov/dpw/watersheds/residential/litter

Williams, A.T., & Tudor, D.T. (2001). Litter burial and exhumation: spatial and temporal distribution on a cobble pocket beach. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 42, 1031-1039.

Join the movement to protect endangered species and preserve our planet's diverse wildlife with Global Conservation Force. Together, we can make a difference for future generations.

- P.O. Box 956 Oceanside, CA 92049

- EIN 474499248

- Copyright 2024. All Rights Reserved. Powered by Wild Media.

- [email protected]

Littering in Public Places: A Significant Issue Essay (Critical Writing)

- To find inspiration for your paper and overcome writer’s block

- As a source of information (ensure proper referencing)

- As a template for you assignment

Introduction

Littering can be defined as the incorrect disposal of trash in places it does not belong. Littering in public places is a significant issue many communities face. People’s carelessness toward the surroundings they live in causes other citizens to suffer. According to Reisch’s characteristic of an ethical issue, littering in public places upholds all standards stated (2019). Public littering is a realistic and winnable issue that is possible to solve, moreover, it is immediate and clearly stated. A problem like this can be an opportunity for the community to unite; additionally, it is likely to be solved through collective action. Lastly, the population of a residential area is affected by public littering because it stands in the way of pleasant recreational activities for both children and adults.

The ultimate goal for the issue of littering in public places would be clearing out the community of any litter and preventing its appearance in the future. The biggest goal should be the termination of littering because even though it takes hard work to clean out the area from litter, the citizens cannot continuously do it. Therefore, making residents understand that future littering in public places will not only affect the community around but also them. Preventional punishments must be created to lower the possibility of people committing this irresponsible action.

A community organization should target community change efforts. As the residents of the specific community are the cause of this issue, its resolvent must target exactly them. Moreover, teamwork will allow a particular community not only to become closer but also to see the consequences of someone’s irresponsibility. After thoroughly analyzing the issue, the organization must create a plan for terminating it and essentially have several alternatives for it. After that, significant actions must be taken to prevent littering from happening again.

Potential allies for public littering issues may vary. The most obvious and realistic are the municipal services. The local government may help increase the number of trash bins in the public areas or town authorities can create penalties or fines for people who get caught littering in public places. In California, such penalties vary from fines to hours of community service (CENN). Such actions are radical but practical. Pro-ecology organizations can be potential allies for the initiative to terminate public littering. Such organizations may cooperate and create info boards that are to be set in public places like parks or bus stations, which inform on the harmful consequences of littering for the environment.

A strategic approach is the most critical component of solving a community-related issue. I think that competition can be of the most significant effect on solving public place littering. The local community will have to choose the most littered public areas and clean them together. The contest can depend on how clean the public area is after the cleaning; therefore, the winners get a prize. The prize can be the renovation of a local playground for children or the installment of a brand new bus stop, which will be up to the winning teams. In such a way, the area around will not only get rid of the rubbish but also become a more comfortable place to be. With the help of local government and eco-organizations, such places will obtain educational information and preventional matters. Collectively with these measures implemented, it is possible to minimize the probability of littering in public places and make a local community more appealing and pleasant to live in.

To conclude, littering in public places is a common issue for communities around the world; however, with appropriate collective actions, it is possible to prevent and terminate it. Directly involving the community to participate, asking local leaders to take action, and teaming up with other organizations can ultimately solve the issue of littering once and for all.

CENN. (n.d.). Reasons, Consequences and Possible Solutions of Littering. Web.

Reisch, M. (2019). Macro social work practice: working for change in a multicultural society . San Diego, CA: Cognella Academic Publishing.

- Old Age Dependency Overview and Analysis

- No Respect Given to Military Family

- Modern Global Issues: Drinking Water Shortage

- Code of Conduct and Ethics in School

- How I Organize my Trash

- The Case of Social Work Supervision: A Self-Reflection

- The Arc Mid-South: Strategy, Mission, Goals

- Social Action as a Method of Social Work

- Woodcock-Johnson Tests of Cognitive Ability III Edition: Critique

- Reflection on Gun-Free Zones

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2022, February 15). Littering in Public Places: A Significant Issue. https://ivypanda.com/essays/littering-in-public-places-a-significant-issue/

"Littering in Public Places: A Significant Issue." IvyPanda , 15 Feb. 2022, ivypanda.com/essays/littering-in-public-places-a-significant-issue/.

IvyPanda . (2022) 'Littering in Public Places: A Significant Issue'. 15 February.

IvyPanda . 2022. "Littering in Public Places: A Significant Issue." February 15, 2022. https://ivypanda.com/essays/littering-in-public-places-a-significant-issue/.

1. IvyPanda . "Littering in Public Places: A Significant Issue." February 15, 2022. https://ivypanda.com/essays/littering-in-public-places-a-significant-issue/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Littering in Public Places: A Significant Issue." February 15, 2022. https://ivypanda.com/essays/littering-in-public-places-a-significant-issue/.

Sciencing_Icons_Science SCIENCE

Sciencing_icons_biology biology, sciencing_icons_cells cells, sciencing_icons_molecular molecular, sciencing_icons_microorganisms microorganisms, sciencing_icons_genetics genetics, sciencing_icons_human body human body, sciencing_icons_ecology ecology, sciencing_icons_chemistry chemistry, sciencing_icons_atomic & molecular structure atomic & molecular structure, sciencing_icons_bonds bonds, sciencing_icons_reactions reactions, sciencing_icons_stoichiometry stoichiometry, sciencing_icons_solutions solutions, sciencing_icons_acids & bases acids & bases, sciencing_icons_thermodynamics thermodynamics, sciencing_icons_organic chemistry organic chemistry, sciencing_icons_physics physics, sciencing_icons_fundamentals-physics fundamentals, sciencing_icons_electronics electronics, sciencing_icons_waves waves, sciencing_icons_energy energy, sciencing_icons_fluid fluid, sciencing_icons_astronomy astronomy, sciencing_icons_geology geology, sciencing_icons_fundamentals-geology fundamentals, sciencing_icons_minerals & rocks minerals & rocks, sciencing_icons_earth scructure earth structure, sciencing_icons_fossils fossils, sciencing_icons_natural disasters natural disasters, sciencing_icons_nature nature, sciencing_icons_ecosystems ecosystems, sciencing_icons_environment environment, sciencing_icons_insects insects, sciencing_icons_plants & mushrooms plants & mushrooms, sciencing_icons_animals animals, sciencing_icons_math math, sciencing_icons_arithmetic arithmetic, sciencing_icons_addition & subtraction addition & subtraction, sciencing_icons_multiplication & division multiplication & division, sciencing_icons_decimals decimals, sciencing_icons_fractions fractions, sciencing_icons_conversions conversions, sciencing_icons_algebra algebra, sciencing_icons_working with units working with units, sciencing_icons_equations & expressions equations & expressions, sciencing_icons_ratios & proportions ratios & proportions, sciencing_icons_inequalities inequalities, sciencing_icons_exponents & logarithms exponents & logarithms, sciencing_icons_factorization factorization, sciencing_icons_functions functions, sciencing_icons_linear equations linear equations, sciencing_icons_graphs graphs, sciencing_icons_quadratics quadratics, sciencing_icons_polynomials polynomials, sciencing_icons_geometry geometry, sciencing_icons_fundamentals-geometry fundamentals, sciencing_icons_cartesian cartesian, sciencing_icons_circles circles, sciencing_icons_solids solids, sciencing_icons_trigonometry trigonometry, sciencing_icons_probability-statistics probability & statistics, sciencing_icons_mean-median-mode mean/median/mode, sciencing_icons_independent-dependent variables independent/dependent variables, sciencing_icons_deviation deviation, sciencing_icons_correlation correlation, sciencing_icons_sampling sampling, sciencing_icons_distributions distributions, sciencing_icons_probability probability, sciencing_icons_calculus calculus, sciencing_icons_differentiation-integration differentiation/integration, sciencing_icons_application application, sciencing_icons_projects projects, sciencing_icons_news news.

- Share Tweet Email Print

- Home ⋅

- Science ⋅

- Nature ⋅

- Environment

The Effects of Littering on the Environment & Animals

Five Reasons Why Littering Is Bad

As humans consume natural resources, they, too, create byproducts that enter Earth's varied ecosystems. Plastic waste, water pollution, soil runoff, and jars and bottles make up just a few of the human-made products and byproducts that can harm the Earth and the species that live on it. The damage can be physical — six-pack rings strangling marine life — or chemical — fertilizers causing algal blooms — but in either case, they can cause lasting damage to the flora and fauna of an area.

Plastic Waste

Discarding plastic products, including grocery sacks, rapidly fills up landfills and often clog drains. When plastic litter drifts out to sea, animals like turtles or dolphins may ingest the plastic. The plastic creates health problems for the animals including depleting their nutrients and blocking their stomachs and intestines. Animals cannot break down plastic in their digestive system and will usually die from the obstruction. Pieces of plastic can also get tangled around animals' bodies or heads and cause injury or death.

Water Pollution

Litter in Earth's water supply from consumer and commercial use creates a toxic environment. The water is ingested by deer, fish and a variety of other animals. The toxins may cause blood clotting, seizures or serious medical issues that can kill animals. The toxic water may also kill off surrounding plant life on riverbanks and the bottom of a pond's ecosystem. When humans eat animals that have ingested compromised water supplies, they also can become sick.

Soil Runoff

Runoff from litter, polluted water, gasoline and consumer waste can infiltrate the soil. The soil absorbs the toxins litter creates and affects plants and crops. The agriculture is often compromised and fails to thrive. Animals then eat those crops or worms that live in the soil and may become sick. Humans who eat either the crops or the animals feeding on the infected agriculture can also become ill.

Jars and Bottles

Discarded jars and bottles usually do not biodegrade naturally and add to humanity's mounting litter problem. The litter remains in landfills and clogs sewers, streets, rivers and fields. Crabs, birds and small animals may crawl into the bottles looking for food and water and become stuck and slowly die from starvation and illness. The World Wide Fund for Nature reported some 1.5 million tons of plastic waste from the water bottling industry alone.

Related Articles

The effects of sewage on aquatic ecosystems, the effects of improper garbage disposal, harmful effects of plastic waste disposal, how does pollution affect dolphins, what are the effects of non-biodegradable waste, types of pollutants, solutions for soil pollution, the effects of water pollution around the world, pollution in the 21st century, examples of secondary pollutants, environmental problems caused by synthetic polymers, negative effects of pollution, environmental problems & solutions, pollution's effects on animals, the effects of pollution on the body, why are plastic grocery bags bad for the environment, ecological impact of chicken farming, list of ways we can reduce trash and litter, define chemical pollution.

- All About Water: The Effects of Bottled Water on the Environment

About the Author

Catherine Irving is a travel and lifestyle writer living in Brooklyn, New York and has been professionally freelance writing since 2002. She's written for "Young Money," Kayak.com, Pokemon.com and numerous other national outlets. Irving graduated with a bachelor's degree in film with a minor in English from Georgia State University.

Find Your Next Great Science Fair Project! GO

Littering - Free Essay Examples And Topic Ideas

An essay on littering can examine the environmental and social consequences of litter and pollution. It can discuss the impact of litter on ecosystems, wildlife, and public spaces, as well as the role of environmental awareness, education, and anti-litter campaigns in addressing this environmental issue, highlighting the importance of responsible waste disposal. A vast selection of complimentary essay illustrations pertaining to Littering you can find in Papersowl database. You can use our samples for inspiration to write your own essay, research paper, or just to explore a new topic for yourself.

A Discussion on the Need to Stop Pollution and Littering

What is pollution? Pollution, as defined by Webster's dictionary, is "to make impure and to contaminate with man-made waste." Pollution has become a major threat to our world today. It is one of the toughest challenges we are facing. It may seem difficult to stop pollution, but the world can certainly reduce it with collective effort. The problem is, there seems to be a lot of talk with less action. Yes, there are various activist groups fighting against pollution, and […]

The Environmental Consequences of Littering

There are several concerns that the planet deals with and also 2 big ones are the results from littering and deforestation. These particular points impact the world around us as well as our neighborhoods. When people clutter, they harm our oceans as well as when people chop down thousands of trees each day it harms a really crucial plant in the survival of all taking a breath things. The planet is where we as individuals live as well as create. […]

The Impact of Mass Tourism Globally and Littering

Tourism has been more established than ever over the past decade. However, while it brings important advantages for countries, tourism also carries a negative influence on several elements. Mass tourism is one type of tourism that creates harmful effects on the environment and culture, particularly in developing countries such as Vietnam. Although mass tourism has rapidly diminished the charms of the country, travelers and the host country can address these troubles with proper solutions. Mass tourism involves tens of thousands […]

We will write an essay sample crafted to your needs.

The Importance of Community Clean-Up Days on Every Weekend from Littering

In the city of Victorville, the community recently organized an event to help improve the area. This event, aptly named 'Area Clean-up Day' takes place once a month. My AVID instructor recommended that my classmates and I participate in the community service to help our city. This kind of civic engagement is a fantastic way to contribute to our futures. However, one question that continually arises is "Why isn't Area Clean-up held every weekend?" After all, rubbish inevitably returns after […]

The Importance of Plastics to our Lives and its Contribution to the Pollution of our Environment and Littering

Plastics are one of the most crucial substances in this period. Their convenience and abilities are commended, however, their effects on contaminating the environment are typically ignored. Since the introduction of commercial use of plastic bags 30 years ago, there has been a decrease in the health of the environment. The littering of plastic has continued to destroy the community and aquatic life as rubbish gathers in the Great Pacific Trash Patch. Due to plastic's slow rate of biodegrading, it […]

The Causes of Littering and how to Prevent it

Litter just does not appear; it is the result of reckless attitudes and inappropriate waste handling. Is there anything you can do? Understanding more about trash and where it originates from is a great place to start. A study by Keep America Beautiful, Inc., has discovered that people litter because: They feel no sense of ownership, even though places such as parks and beaches are public property. They believe someone else, a park maintenance or highway worker, will clean up […]

An Introduction to the Issue of Littering in Today’s Society

"Close friend, please don't throw rubbish on the ground. Dispose of it in the litter bin," I stated to my friend. She responded, "What are the sweepers for, anyhow?" I chose to overlook her comment. This isn't the only instance I've come across. I've been advising all of my friends to avoid littering. What I often hear back is, "Who cares? There's already so much litter on the ground, it's the sweepers' job to clean it," or "The bin is […]

Strict Consequences should be Implemented to Punish Littering in America

In the USA, littering has actually reached an all-time high. Keeping a clean living space is an important part of life. The majority of the trash that accumulates is, in fact, unintentional. Sometimes, littering does occur accidentally. Something might fall out of your pocket or possibly fly from the rear seat of a vehicle out of a window. Not that this justifies the act of littering, but it might not be intentional. However, there are some people who do litter […]

The Long Term Effects of Littering and Pollution on the Environment

Cluttering, as well as contamination, is a significant problem around the world today. It influences all of our lives and will undoubtedly continue to do so for years to come. Clutter and pollution play a substantial role in our everyday experiences. Wherever we walk or drive, there's garbage on the roadside, thrown out of windows, and dangling from trees. However, even minor efforts on our part can bring about change and help make the earth a better place. With less […]

The Bad Side of Littering and the Projects to Clean the Beaches of Miami

Trash is specified as solid waste that has been displaced, either by wind, traffic, or even water. It travels until it gets caught on something, like an aesthetic or fence [Unk13]. Typically, when litter has been placed somewhere, it invites others to add more to the heap, despite the penalties in Florida for such actions. It affects people everywhere, from tourists to businesses. There are numerous efforts out there to clean up our beaches, yet it still doesn't seem to […]

School Communities should be Involved more in Establishing Policies for Littering

There are numerous issues with pollution in the neighborhood nowadays. Some of these can be dangerous, while others are harmless to us. A significant problem in our neighborhood is the littering in and around school universities. This might seem harmless to some, but it sets a negative example and can be hazardous for the local flora and fauna. It appears that students these days simply do not care about littering. Firstly, the Student Council needs to be more engaged and […]

Additional Example Essays

- Why Should Recycling be Mandatory?

- Poor Nutrition and Its Effects on Learning

- Deepwater Horizon Oil Spill

- Plastic Straws Cause and Effect Final Draft

- Before The Flood

- Importance Of Accountability

- Oedipus is a Tragic Hero

- Dogs Are Better Than Cats Essay

- Medieval Romance "Sir Gawain and the Green Knight"

- Personal Philosophy of Leadership

- Personal Narrative: My Family Genogram

- What Do The Bells Symbolize in The Cask of Amontillado

1. Tell Us Your Requirements

2. Pick your perfect writer

3. Get Your Paper and Pay

Hi! I'm Amy, your personal assistant!

Don't know where to start? Give me your paper requirements and I connect you to an academic expert.

short deadlines

100% Plagiarism-Free

Certified writers

- News, Stories & Speeches

- Get Involved

- Structure and leadership

- Committee of Permanent Representatives

- UN Environment Assembly

- Funding and partnerships

- Policies and strategies

- Evaluation Office

- Secretariats and Conventions

- Asia and the Pacific

- Latin America and the Caribbean

- New York Office

- North America

- Climate action

- Nature action

- Chemicals and pollution action

- Digital Transformations

- Disasters and conflicts

- Environment under review

- Environmental law and governance

- Extractives

- Fresh Water

- Green economy

- Ocean, seas and coasts

- Resource efficiency

- Sustainable Development Goals

- Youth, education and environment

- Publications & data

Everything you need to know about plastic pollution

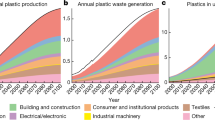

This year’s World Environment Day – the fiftieth iteration of the annual celebration of the planet – is focusing on the plastic pollution crisis. The reason? Humanity produces more than 430 million tonnes of plastic annually, two-thirds of which are short-lived products that soon become waste, filling the ocean and, often, working their way into the human food chain.

“Many people aren’t aware that a material that is embedded in our daily life can have significant impacts not just on wildlife, but on the climate and on human health,” says Llorenç Milà i Canals, Head of the United Nations Environment Programme’s (UNEP’s) Life Cycle Initiative.

Read our explainer to find out more about the plastic pollution crisis:

Why is plastic pollution such a problem?

Affordable, durable and flexible, plastic pervades modern life, appearing in everything from packaging to clothes to beauty products. But it is thrown away on a massive scale: every year, more than 280 million tonnes of short-lived plastic products become waste.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_NAbkldMV48&feature=youtu.be

Overall, 46 per cent of plastic waste is landfilled , while 22 per cent is mismanaged and becomes litter. Unlike other materials, plastic does not biodegrade. This pollution chokes marine wildlife, damages soil and poisons groundwater, and can cause serious health impacts .

Is pollution the only problem with plastic?

No, it also contributes to the climate crisis. The production of plastic is one of the most energy-intensive manufacturing processes in the world. The material is made from fossil fuels such as crude oil, which are transformed via heat and other additives into a polymer. In 2019, plastics generated 1.8 billion metric tonnes of greenhouse gas emissions – 3.4 per cent of the global total.

Where is all this plastic coming from? The packaging sector is the largest generator of single-use plastic waste in the world. Approximately 36 per cent of all plastics produced are used in packaging. This includes single-use plastic food and beverage containers, 85 per cent of which end up in landfills or as mismanaged waste.

Farming is another area where plastic is ubiquitous: it is used in everything from seed coatings to mulch film. The fishing industry is another significant source. Recent research suggests more than 100 million pounds of plastic enters the oceans from industrial fishing gear alone. The fashion industry is another major plastic user. About 60 per cent of material made into clothing is plastic , including polyester, acrylic and nylon.

I have heard people talk about microplastics. What are those?

They are tiny shards of plastic measuring up to 5mm in length. They come from everything from tires to beauty products, which contain microbeads, tiny particles used as exfoliants. Another key source is synthetic fabrics. Every time clothing is washed, the pieces shed tiny plastic fibres called microfibres – a form of microplastics. Laundry alone causes around 500,000 tonnes of plastic microfibres to be released into the ocean every year –the equivalent of almost 3 billion polyester shirts.

What is being done about plastic pollution? In 2022, UN Member States agreed on a resolution to end plastic pollution. An Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee is developing a legally binding instrument on plastic pollution, with the aim of having it finalized by the end of 2024. Critically, the talks have focused on measures considering the entire life cycle of plastics, from extraction and product design to production to waste management, enabling opportunities to design out waste before it is created as part of a thriving circular economy.

What more needs to be done? While this progress is good news, current commitments by governments and industry are not enough. To effectively tackle the plastic pollution crisis, systemic change is needed. This means, moving away from the current linear plastic economy, which centres on producing, using and discarding the material, to a circular plastic economy , where the plastic that is produced is kept in the economy at its highest value for as long as possible.

How can countries make that a reality?

Countries need to encourage innovation and provide incentives to businesses that do away with unnecessary plastics. Taxes are needed to deter the production or use of single-use plastic products, while tax breaks, subsidies and other fiscal incentives need to be introduced to encourage alternatives, such as reusable products. Waste management infrastructure must also be improved. Governments can also engage in the Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee process to forge a legally binding instrument that tackles plastic pollution, including in the marine environment.

What can the average person do about plastic pollution? While the plastic pollution crisis needs systemic reform, individual choices do make a difference. Such as shifting behaviour to avoid single-use plastic products whenever possible. If plastic products are unavoidable, they should be reused or repurposed until they can no longer be used – at which point they should be recycled or disposed of properly. Bring bags to the grocery store, and if possible, striving to purchase locally sourced and seasonal food options that require less plastic packaging and transport.

Should I lobby governments and businesses to address plastic pollution?

Yes. One of the most important actions individuals can take is to ensure their voice is heard by talking to their local representatives about the importance of the issue, and supporting businesses that are striving to reduce single-use plastic products in their supply chains. Individuals can also show their support for them on social media. If people see a company using unnecessary plastic (such as single-use plastics covering fruit at a grocery store) they can contact them and ask them to do better.

For more information on how you can help tackle the plastic pollution crisis, download the Beat Plastic Pollution Practical Guide .

About World Environment Day World Environment Day on 5 June is the biggest international day for the environment. Led by UNEP and held annually since 1973, the event has grown to be the largest global platform for environmental outreach, with millions of people from across the world engaging to protect the planet. This year, World Environment Day will focus on solutions to the plastic pollution crisis.

- Chemicals & pollution action

- Plastic pollution

- Marine Litter

Further Resources

- UNEP’s work on chemicals and waste

- Pollution and the Circular Economy

- Beat Plastic Pollution

- Financing Circularity: Demystifying Finance for the Circular Economy

- Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee on Plastic Pollution

- Beat Plastic Pollution Practical Guide

Related Content

Related Sustainable Development Goals

© 2024 UNEP Terms of Use Privacy Report Project Concern Report Scam Contact Us

An official website of the United States government

Here’s how you know

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock A locked padlock ) or https:// means you’ve safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

JavaScript appears to be disabled on this computer. Please click here to see any active alerts .

What You Can Do About Trash Pollution

We all play a role in helping to prevent and remove trash in the environment. You can take action at home, school, and work to ensure a cleaner community and healthier waters.

Watch the video " Repair the Future " to learn how everyone can help to reduce aquatic trash. This video was created by marketing students from California State Polytechnic University-Pomona and was the winner of the 2020 American Marketing Association (AMA)- EPA Trash Free Waters Video and Marketing Brief Competition.

On this page:

- Reduce Consumer Waste

- Dispose of Waste Properly

Volunteer in Your Community

- Learn More and Spread the Message

Reduce Consumer Waste

The most effective way to prevent trash from polluting our waterways is to reduce the amount of waste you create .

- Replace single-use plastic packaging, bottles, and containers with reusable products or eliminate packaging when possible. Discover 10 ways to Unpackage Your Life page.

- Buy used clothing and household items.

- Repair, rather than replace, broken items.

- Learn more about how to Reduce, Reuse, and Recycle .

Dispose of Waste Properly

Marine litter is often the result of poorly-managed trash on land. If trash is intentionally or accidentally littered on the ground, wind or rain can carry it into nearby waterways. The trash then travels downstream and can ultimately, end up in the ocean.

Never litter. Put trash in the appropriate bins and do not leave trash next to- or on top of an overflowing bin.

Go to your municipality's website to learn how to properly dispose of your recyclable and non-recyclable waste. Be sure to recycle more, recycle right.

Take these steps to prevent trash from escaping from your outdoor trash bins on collection day:

Keep your lid closed and don’t overflow the trash bin.

Put trash outside shortly before pickup.

- Properly dispose of your Personal Protective Equipment (PPE). Remember to throw your masks, wipes, and latex gloves in the trash and not in the recycling bin, street, parking lot, or sidewalk. Para ver una infografía en español, haga clic aquí .

Organize and participate in local waterway cleanups .

Collect data on what you find!

Use the Marine Debris Campus Toolkit to bring positive change to your university.

Invite your friends, family, and classmates to join in!

Learn More and Spread the Message

Learn basic information about aquatic trash from the EPA Trash Free Waters website and go deeper by checking out these helpful websites and resources.

Read the Trash-Free Waters newsletter or watch our webinar series to stay up to date with recent trash capture projects and research efforts.

- Trash Free Waters Home

- Learn About Aquatic Trash

- What EPA is Doing

- 10 Ways to Unpackage Your Life

- Best Management Practices & Tools

- Science & Case Studies

- Webinar Library

- Trash Free Waters Article Series

- 'The Flow' Newsletter Archive

- 'The Rapids' Email Archive

- Skip to main content

- Skip to secondary menu

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Skip to footer

A Plus Topper

Improve your Grades

Essay on Littering | Littering Essay for Students and Children in English

February 13, 2024 by Prasanna

Essay on Littering: We often see people throwing banana peels, bits of papers here and there. Many people while going on roads spit there and throw wrappers and other wastes directly on the roads. Many industries and big factories also generate chemical wastes that they dump into water bodies without treating them properly. It is really sad to see the laziness and damn care of people about the environment.

Littering is an environmental issue and requires great attention. However, people are not concerned about the environment. They litter the environment either in small deeds or in big deeds. The Government also spends a great amount of money to clear the wastes for which the economy also gets affected. Thus people need to be aware and sensitised regarding this. They should teach the habits to get rid of litter but efficiently and properly.

You can also find more Essay Writing articles on events, persons, sports, technology and many more.

Long and Short Essays on Littering for Students and Kids in English

We provide the students with essay samples on an extended essay of 500 words and a short essay of 150 words on the topic of Littering.

Long Essay on Littering 500 Words in English

Long Essay on Littering is usually given to classes 7, 8, 9, and 10.