Unit 1-Introduction to ICT

Mar 24, 2019

11.04k likes | 22.27k Views

Unit 1-Introduction to ICT. Unit 1-Introduction to ICT. Table of Contents What Is Information and Communication Technology? ICT and the Environment Ergonomics. What Is Information and Communication Technology?. What Is Information and Communication Technology (ICT)?. Information

Share Presentation

- manufacturers solution

- electronics companies

- communication technology

- communication technology ict

- create safer recycling systems

Presentation Transcript

Unit 1-Introduction to ICT Table of Contents What Is Information and Communication Technology? ICT and the Environment Ergonomics

What Is Information and Communication Technology?

What Is Information and Communication Technology (ICT)? • Information • Communication • Technology • A good way to think about ICT is to think about all the ways digital technology is used to help individuals, businesses and organizations use information. • ICT includes any product that will process information electronically • ICT will store, retrieve, manipulate, transmit or receive information electronically.

What Is Information and Communication Technology? • What do you think is an example of ICT? • Anything that help you access, use, and share information is ICT: • from computer, digital television, email, robots or household devices, such as electronic calendars, clocks, timers, to cell phones and PDAs.

What Is Information and Communication Technology? • Discussion: • With the person beside you: • Identify five examples of ICT in your home. • Identify five examples of ICT in your school. • Where would we be without technology? • Video: ICT: Getting Connected to Sustainability • http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Yzk1CCLqFvQ&feature=related

What Is Information and Communication Technology? • How has advances in ICT affected our relationship with people? • ICT has even affected relationships among people by allowing them to communicate in new and different ways. • How do you communicate with your friends? • How do people communicate in work world? • Whether it is through voice mail, text messaging, instant messaging, or e-mail, people rely on ICT to keep contact. • Video:Communication and ICT Video • http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=P0M2pvYD7Co

What Is Information and Communication Technology? • Video: • ICT - Benefits of using ICT http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kE0NT2-91eU&feature=related • Digital Nation: Frontline Video • http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/digitalnation/view/

ICT and the Environment

ICT and the Environment • Discussion: • What effects do your electronic activities have on the environment?

ICT and the Environment • To find out more information on this topic, lets read the PDF article in the 0836-STU Folder: • “ICT and The Environment” • Read only the first page • Discussion: • The three categories of environmental impact are raw materials used to make the ICT device, energy use, and waste. • When you bought your ICT device, did any of these categories have an impact on which device you bought?

ICT and the Environment-Disposal Lets get more into the third category, waste. Computer hardware disposed of at landfills has serious implications on the environment. We export enough e-waste each year to fill 5126 shipping containers (40 ft x 8.5 ft). If you stacked them up, they’d reach 8 miles high – higher than Mt Everest, or commercial flights. • But what really happens to your old computer or broken printer or fried cell phone?

ICT and the Environment-Disposal Digital Dumping: Disposal of Obsolete Equipment Shipped to developing countries: Salvage, then Landfill tons of these and other electronic items are loaded onto barges and shipped off to developing countries, where the recycling processes are so substandard (low) that they actually contribute to air and water pollution. Whatever isn’t salvageable (reusable) ends up in their landfills.

ICT and the Environment-Disposal Digital Dumping: Disposal of Obsolete Equipment continued… Try to “bridge the digital divide”, then Landfill North American recyclers say it’s not cost efficient to fix broken items, so they often donate these goods to developing nations to help “bridge the digital divide.” Many countries, though, report that up to 75% of this equipment is not usable, nor do they have the technology to repair or recycle it properly.

ICT and the Environment-Disposal • Read the following article: • “What happens to old computers?” • http://computer.howstuffworks.com/discarded-old-computer.htm • Answer the following questions: • What is a growing number of advocacy groups doing? • Define e-waste. • Why shouldn’t old computer go to the landfill? • What problems do the hazardous chemicals and toxic substances in the computers cause to humans? • How should old computers be recycled? • In reality how are they recycled? • What is one of the main reasons that e-waste is transported? • Name two ways that e-waste is dismantled.

ICT and the Environment-Disposal • Now lets see some proof of this... • Read the following article: • “Tossing your computer? Read this first” • http://www.cbc.ca/marketplace/pre-2007/files/environ/hitech_trash/index.html • Answer the following questions: • What happens to computers when they reach the end of their useful lives? • What did Jim Puckett find when he shot his video in China? • What were the consequences of the tech debris (e-waste)? • According to Jim Puckett, Canada shouldn’t be shipping e-waste to China for what reason? • Explain this treaty.

ICT and the Environment-Disposal • Video • Ghana: Digital Dumping Ground • http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OkpBcFDjk7Y&feature=related • Video • The Wasteland • http://www.cbsnews.com/video/watch/?id=5274959n

ICT and the Environment-Disposal What are the disposal policies in Canada? What environmental policies do computer manufacturers have?

ICT and the Environment-Disposal • Read the following summary: • “Disposal policies in Canada” • http://www.cbc.ca/marketplace/pre-2007/files/environ/hitech_trash/disposal.html • Discussion: • Based on this information, what changes would you make to policies for computer disposal in these cities?

ICT and the Environment-Disposal • Check out the environmental policies of at least two computer manufacturers, such asApple, IBM, MDG Computers, and Dell. • In pairs, compare their environmental policies with respect to manufacturing and recycling computer hardware. Which computer manufacturer has a better environmental policy? Explain why.

ICT and the Environment-Solution • What do we do with our old electronic equipment? • Most charitable groups won’t take it – it’s too old. • The city dump won’t take it –your old machine is full of toxic substances. • You don’t want it sitting in the closet for eternity.

ICT and the Environment-Solution • Video: • The Story of Electronics • The Story of Electronics explores the high-tech revolution's collateral damage—25 million tons of e-waste and counting, poisoned workers and a public left holding the bill. Host Annie Leonard takes viewers from the mines and factories where our gadgets begin to the horrific backyard recycling shops in China where many end up. The film concludes with a call for a green 'race to the top' where designers compete to make long-lasting, toxic-free products that are fully and easily recyclable. • http://www.storyofstuff.org/movies-all/story-of-electronics/

ICT and the Environment-Solution • The Story of Electronics Continued • Answer the following questions: • What is the main issue that the video presented? • What does “Designed for the dump” mean? • List 1 solution for the manufacturer and 1 solution for the individual.

ICT and the Environment-Solution • The Story of Electronics Continued • Answers: • What does “Designed for the dump” mean? • Designed for the dump: means making stuff to be thrown away quickly. • Today's electronics are hard to upgrade, easy to break, and impractical to repair. • This is a key strategy of the companies that make our electronics. • a key part of our whole unsustainable materials economy.

ICT and the Environment-Solution • Manufacturers Solution • Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR), (also called "Producer Takeback,“) • is a product and waste management system in which manufacturers – not the consumer or government – take responsibility for the environmentally safe management of their product when it is no longer useful or discarded.

ICT and the Environment-Solution • Manufacturers Solution continued... • When manufacturers take responsibility for the recycling of their own products, they no longer pass the cost of disposal of these toxic products to the government or the tax payers. • Also, they will have a financial incentive to: • Use environmentally safer materials in the production process • Design the product to be more easily recycled • Create safer recycling systems • Keep waste costs down

ICT and the Environment-Solution • Which companies are making progress? • Many companies are moving in the right direction. • For example, some companies have removed specific toxics from their products, like PVC and flame-retardants. • These are great steps, but they're still too small to really turn things around. Electronics need to be - and can be - made much more safe and more durable. • A toxics free computer that only lasts a year isn't good enough.

ICT and the Environment-Solution • Some companies are doing a good job in taking back and recycling their old products. • Check out Electronics TakeBack Coalition (ETBC) Electronics Recycling Scorecard to find out who's leading the way to greener electronics and who's playing catch up. • http://www.electronicstakeback.com/hold-manufacturers-accountable/recycling-report-card/

ICT and the Environment-Solution • Individual Solutions: • What can I do? • How can I be sure my old stuff isn’t getting exported? • Send a message to electronics companies • Let's turn this toxic mess around! You can send a strong message to electronics companies today, demanding that they "make 'em safe, make 'em last, and take 'em back." • http://www.electronicstakeback.com/home/

ICT and the Environment-Solution • What can I do? Continued... • Donate for reuse • If your product can be reused, donate it to a reputable reuse organization, that won't export it unless it's fully functional. • Some good organizations include • Electronic Recycling Association www.era.ca • Rechargeable Battery Recycling Corporation www.call2recycle.org • Salvation Army www.tstores.ca

ICT and the Environment-Solution • “What can I do?” continued... • Find an e-Steward. If your product is too old or too broken to donate, recycle it. But many recyclers simply export your old products, dumping them on developing nations. • So your best option is to use a recycler who is part of the “e-Steward” network; they don’t export to developing nations, and they follow other high standards. • e-Stewards http://e-stewards.org/ • City of Toronto http://www.toronto.ca/target70/electronics.htm • “We Want It” • http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=91OXkMkesBc • Electronic Recycling Association www.era.ca • Rechargeable Battery Recycling Corporation www.call2recycle.org

ICT and the Environment-Solution • “What can I do?” continued... • Manufacturer takeback programs. • If there is no e-Steward near you, then use the manufacturer’s takeback program. Many have voluntary takeback programs where they will recycle your old products for free. Some offer trade-in value for your products. • Discussion: • What did you find when you compared the environmental policies of computer manufactures with respect to manufacturing and recycling computer hardware?

ICT and the Environment-Solution • “What can I do?” continued... • Discussion: • According to the Marketplace article, in 2002 the Canadian computer industry wanted to add a $25 fee to the cost of computers to cover recycling. Now that this fee has been added, in your opinion, do you think the problem of e-waste has been resolved?

ICT and the Environment-Solution • “What can I do?” continued... • Freecycling Article • Freecycling is a new alternative to bringing your unwanted stuff to a landfill by trading things through a network of people online. • For example, if you have something you no longer want, you would post it on the freecycling website. Someone who wants that item would then contact you and arrange to get it. • How do you think this concept can be applied to computer waste in your community? • http://www.emagazine.com/archive/2297 • http://www.freecycle.org/

ICT and the Environment-Solution • What can I do?” continued... • More solutions: “Earth Week: Green computing solutions” • Website shows some of the best software, web sites, blogs, extensions, widgets and doo-dads that help you to understand and potentially lessen your environmental footprint. • http://www.butterscotch.com/tutorial/Earth-Week-Green-Computing-Solutions

Check Your Understanding What are the main reasons there is so much e-waste in our society? What should computer manufacturers do to reduce waste? What should consumers do with their old electronic equipment? List and describe two possible solutions for e-waste. How can you be sure your old electronic equipment isn’t getting exported? When you purchase your next computer, how will you decide which one is the most environmentally friendly?

Ergonomics-See next PPT

- More by User

Unit 1 : Introduction to Internetworking

· What did you learn in TDC 361 and 362? · What is a (communications) network? An interconnected structure that allows attached devices to communicate with each other · Client/Server Model · Network Protocols · Network Classifications: LAN, MAN, WAN etc. · Internetwork

454 views • 26 slides

Unit 1 Introduction to DBMS

Unit 1 Introduction to DBMS. Common Terms. Data : collection of interrelated information about world being modeled DBMS : general-purpose software to define, create, modify, retrieve, delete and manipulate a database Goals: Efficient data management (faster than files) Large amount of data

229 views • 0 slides

OCR Nationals ICT – Unit 1

OCR Nationals ICT – Unit 1. Task 3 Grade C. Task Overview

259 views • 6 slides

Unit 1 Introduction to Computers

Unit 1 Introduction to Computers. Lesson 1.04 Software and Saving. Introduction: Software and Saving. Have there been times when you have forgotten what you named a file, had an error while saving a file, or opened a file and nothing was in the file.

321 views • 10 slides

OCR Nationals ICT – Unit 1. Task 4 Grade C. Task Overview In this task you will use word processing or desktop publishing software to create a variety of appropriate business documents relevant to the French trip. These must include a letter and at least two other documents .

283 views • 16 slides

Unit 1-1 Introduction to Physics

Unit 1-1 Introduction to Physics. Mr. Clements. Introduction. Welcome to Physics Physics Phor Phun Safety What you will need Lab Procedures Outline of Course Grading Absences.

204 views • 2 slides

UNIT 1: INTRODUCTION TO PSYCHOLOGY

UNIT 1: INTRODUCTION TO PSYCHOLOGY. AREA OF STUDY 2 LIFESPAN DEVELOPMENT. RESEARCH METHODS FOR STUDYING DEVELOPMENT. Longitudinal Studies / Cross-Sectional Studies Twin Studies Adoption Studies Selective Breeding Experiments. LONGITUDINAL STUDIES.

473 views • 12 slides

Unit 1: Introduction to Chemistry

Unit 1: Introduction to Chemistry. Pre- AP Chemistry Edmond NorthHigh School Chapters: 1 & 2. Scientific Method / Process. The Scientific Method is a systematic approach to problem solving. It is generally composed of the following parts: Question Hypothesis Experiment

1.14k views • 92 slides

Unit-1 Introduction to Java

Unit-1 Introduction to Java. Overloading. Overloading. Overloading is a mechanism in which we can use many methods having the same function name but can pass different number of parameters or different types of parameters.

176 views • 3 slides

Unit 1: Introduction to Anatomy

Unit 1: Introduction to Anatomy. Test Review. Which term refers to the study of how an organ functions? . Physiology. A group of similar cells performing a specialized function is referred to as a(n) . Tissue . Cells are to tissues as tissues are to. Organs .

779 views • 64 slides

OCR Nationals ICT – Unit 1. Task 2 Grade C. Task Overview As part of your task organising the French trip, you need to find out about different options for the trip. You must store some of this information for use in Tasks 4 and 5 of this assignment. Using the Booklet

240 views • 10 slides

Unit 1 Introduction to Chemistry

Outline. Unit 1 Introduction to Chemistry. Internet web site: www.unit5.org/chemistry. PowerPoint Presentation by Mr. John Bergmann. Safety. Basic Safety Rules. #1 Rule:. Use common sense. Others:. No horseplay. No unauthorized experiments. . Handle chemicals/glassware with respect.

832 views • 72 slides

OCR Nationals ICT – Unit 1. Task 4 Grade A. Task Overview In this task you will use word processing or desktop publishing software to create a variety of appropriate business documents relevant to the French trip. These must include a letter and at least two other documents .

434 views • 27 slides

Unit 1: Introduction to Chemistry. The Scientific Method:. An organized approach to solve problems. (We do this all the time!). Steps in the Scientific Method:. Observe Use your five senses Define the problem Hypotheses “Educated guess†Reasonable explanations for what was observed.

758 views • 9 slides

Delivering Unit 1- Using ICT

Delivering Unit 1- Using ICT. By the end of today you should:. have a clear and accurate understanding of what this unit is all about understand the project requirements understand the assessment strategy be aware of the admin requirements know how to make the most of DiDA’s flexibility.

594 views • 24 slides

Unit 1 Introduction to Marketing

Unit 1 Introduction to Marketing. Marketing….. defined. The Chartered Institute of Marketing define marketing as 'The management process responsible for identifying , anticipating and satisfying customer requirements profitably'. Marketing….. defined. Philip Kotler defines marketing as

1.48k views • 59 slides

Introduction to Unit 1

Introduction to Unit 1. Geography…Its Nature & Perspectives. Where does Geography come from?. First named by Greek scholar Eratosthenes Geo= “Earth” Graphy= “to write”. Thinking Geographically.

349 views • 17 slides

Unit 1: Introduction to Trigonometry

Unit 1: Introduction to Trigonometry. LG 1-1: Angle Measures LG 1-2: THE Unit Circle LG 1-3: Evaluating Trig Functions LG 1-4: Arc Length Quiz tomorrow TEST 8/29. Consider a circle, centered at the origin with 2 rays extending from the center.

329 views • 15 slides

OCR Nationals ICT – Unit 1. Task 1 Grade A. Task Overview

290 views • 18 slides

Unit 1: Introduction To .Net

Unit 1: Introduction To .Net. Introduction to .Net. Integrated Development Environment (IDE) Languages in the .NET Framework The Common Language Runtime Accessing Data with ADO.NET & XML Accessing the Web with ASP.NET. Integrated Development Environment (IDE). Editor/Browser.

138 views • 12 slides

Introduction to Unit 1. Mechanics Unit 1 Summary. Linear Kinematics 1D & 2D kinematics Relativistic Motion Relativistic Mass Relativistic Energy Other Relativistic Effects Angular Kinematics Angular Notation Kinematic Relationships Tangential Speed Rotational Dynamics

1.06k views • 94 slides

Unit-1 Introduction to Java. Basics of Java programming. Introduction.

501 views • 38 slides

- ICT Information And Communications Technology

- Popular Categories

Powerpoint Templates

Icon Bundle

Kpi Dashboard

Professional

Business Plans

Swot Analysis

Gantt Chart

Business Proposal

Marketing Plan

Project Management

Business Case

Business Model

Cyber Security

Business PPT

Digital Marketing

Digital Transformation

Human Resources

Product Management

Artificial Intelligence

Company Profile

Acknowledgement PPT

PPT Presentation

Reports Brochures

One Page Pitch

Interview PPT

All Categories

Powerpoint Templates and Google slides for ICT Information And Communications Technology

Save your time and attract your audience with our fully editable ppt templates and slides..

Item 1 to 60 of 71 total items

- You're currently reading page 1

This complete presentation has PPT slides on wide range of topics highlighting the core areas of your business needs. It has professionally designed templates with relevant visuals and subject driven content. This presentation deck has total of seventy eighjt slides. Get access to the customizable templates. Our designers have created editable templates for your convenience. You can edit the color, text and font size as per your need. You can add or delete the content if required. You are just a click to away to have this ready-made presentation. Click the download button now.

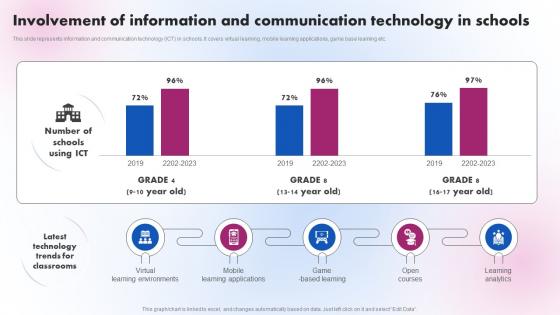

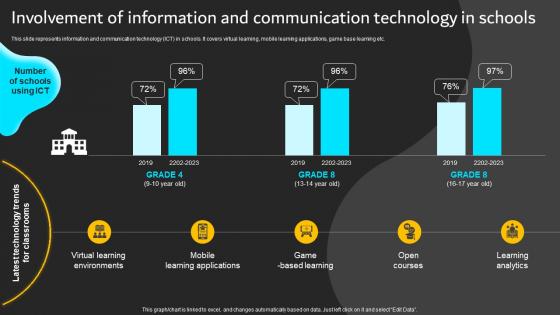

This slide represents information and communication technology ICT in schools. It covers virtual learning, mobile learning applications, game base learning etc. Present the topic in a bit more detail with this Involvement Of Information And Communication Delivering ICT Services For Enhanced Business Strategy SS V. Use it as a tool for discussion and navigation on Learning Environments, Open Courses. This template is free to edit as deemed fit for your organization. Therefore download it now.

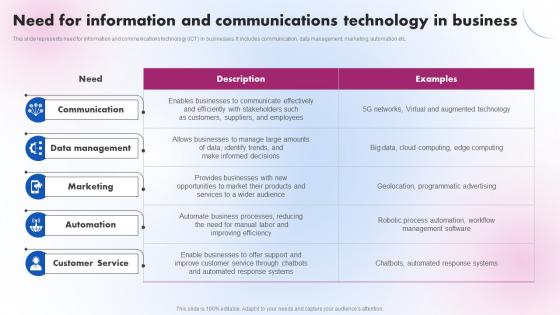

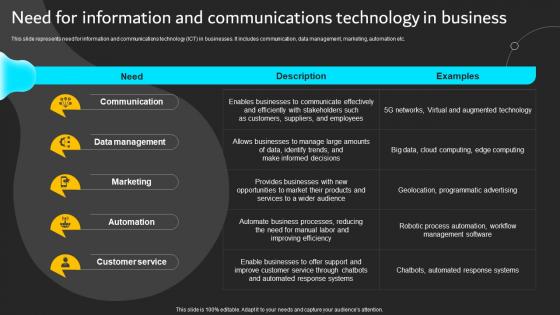

This slide represents need for information and communications technology ICT in businesses. It includes communication, data management, marketing, automation etc. Present the topic in a bit more detail with this Need For Information And Communications Delivering ICT Services For Enhanced Business Strategy SS V. Use it as a tool for discussion and navigation on Communication, Data Management, Marketing. This template is free to edit as deemed fit for your organization. Therefore download it now.

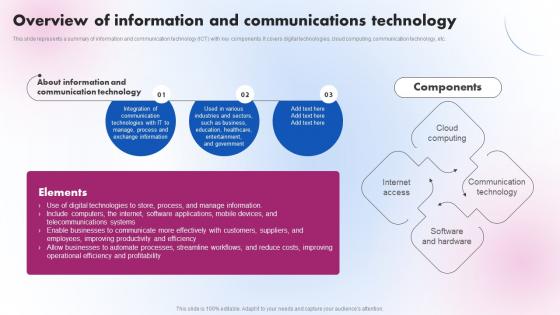

This slide represents a summary of information and communication technology ICT with key components. It covers digital technologies, cloud computing, communication technology, etc. Increase audience engagement and knowledge by dispensing information using Overview Of Information And Communications Delivering ICT Services For Enhanced Business Strategy SS V. This template helps you present information on three stages. You can also present information on Exchange Information, Entertainment, And Government using this PPT design. This layout is completely editable so personaize it now to meet your audiences expectations.

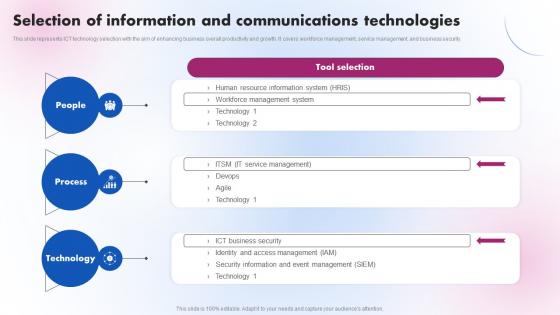

This slide represents ICT technology selection with the aim of enhancing business overall productivity and growth. It covers workforce management, service management, and business security. Increase audience engagement and knowledge by dispensing information using Selection Of Information And Communications Delivering ICT Services For Enhanced Business Strategy SS V. This template helps you present information on three stages. You can also present information on People, Process, Technology using this PPT design. This layout is completely editable so personaize it now to meet your audiences expectations.

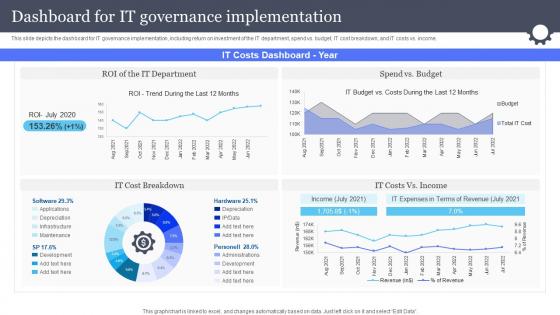

This slide depicts the dashboard for IT governance implementation, including return on investment of the IT department, spend vs. budget, IT cost breakdown, and IT costs vs. income. Deliver an outstanding presentation on the topic using this Dashboard For It Governance Implementation Information And Communications Governance Ict Governance. Dispense information and present a thorough explanation of Governance, Implementation, Dashboard using the slides given. This template can be altered and personalized to fit your needs. It is also available for immediate download. So grab it now.

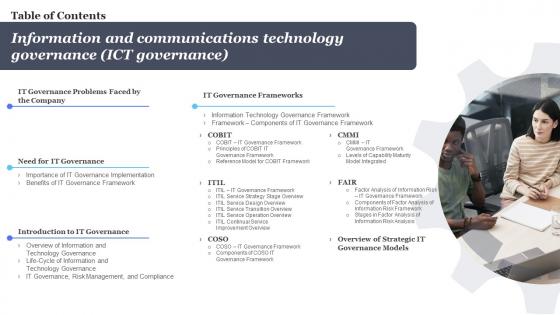

Introducing Table Of Contents Information And Communications Technology Governance Ict Governance to increase your presentation threshold. Encompassed with four stages, this template is a great option to educate and entice your audience. Dispence information on Information, Communications, Technology, using this template. Grab it now to reap its full benefits.

This slide represents information and communication technology ICT in schools. It covers virtual learning, mobile learning applications, game base learning etc.Present the topic in a bit more detail with this Involvement Of Information And Communication Implementation Of ICT Strategic Plan Strategy SS. Use it as a tool for discussion and navigation on Virtual Learning, Learning Applications, Game Based. This template is free to edit as deemed fit for your organization. Therefore download it now.

This slide represents the 30-60-90 days plan to implement IT governance in the company, including the tasks to be performed at each 30 days interval. Introducing 30 60 90 Days Plan To Implement It Governance Information And Communications Governance Ict Governance to increase your presentation threshold. Encompassed with three stages, this template is a great option to educate and entice your audience. Dispence information on Transformation, Organization, Frameworks, using this template. Grab it now to reap its full benefits.

Increase audience engagement and knowledge by dispensing information using Agenda Information And Communications Technology Governance Ict Governance. This template helps you present information on four stages. You can also present information on Information, Communications, Technology using this PPT design. This layout is completely editable so personaize it now to meet your audiences expectations.

This slide describes the benefits of the IT governance framework that help businesses to be more productive, provide the foundation to align IT and business strategies, and so on. Introducing Benefits Of It Governance Framework Information And Communications Governance Ict Governance to increase your presentation threshold. Encompassed with eight stages, this template is a great option to educate and entice your audience. Dispence information on Governance, Framework, Strategic, using this template. Grab it now to reap its full benefits.

This slide represents the budget for IT governance implementation, including staff and compensation, hardware, software, and project expenses. Present the topic in a bit more detail with this Budget For It Governance Implementation Information And Communications Governance Ict Governance. Use it as a tool for discussion and navigation on Governance, Implementation, Compensation. This template is free to edit as deemed fit for your organization. Therefore download it now.

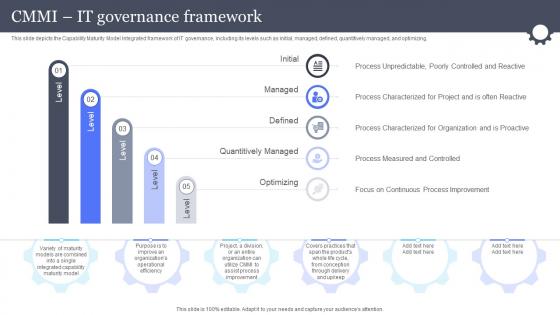

This slide depicts the Capability Maturity Model Integrated framework of IT governance, including its levels such as initial, managed, defined, quantitively managed, and optimizing. Deliver an outstanding presentation on the topic using this Cmmi It Governance Framework Information And Communications Governance Ict Governance. Dispense information and present a thorough explanation of Governance, Framework, Optimizing using the slides given. This template can be altered and personalized to fit your needs. It is also available for immediate download. So grab it now.

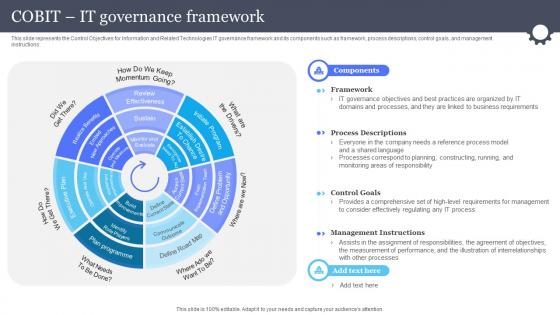

This slide represents the Control Objectives for Information and Related Technologies IT governance framework and its components such as framework, process descriptions, control goals, and management instructions. Present the topic in a bit more detail with this Cobit It Governance Framework Information And Communications Governance Ict Governance. Use it as a tool for discussion and navigation on Framework, Process Descriptions, Management Instructions. This template is free to edit as deemed fit for your organization. Therefore download it now.

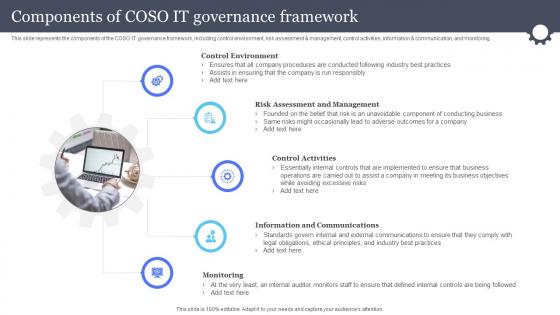

This slide represents the components of the COSO IT governance framework, including control environment, risk assessment and management, control activities, information and communication, and monitoring. Introducing Components Of Coso It Governance Framework Information And Communications Governance Ict Governance to increase your presentation threshold. Encompassed with five stages, this template is a great option to educate and entice your audience. Dispence information on Control Environment, Risk Assessment And Management, Information And Communications, using this template. Grab it now to reap its full benefits.

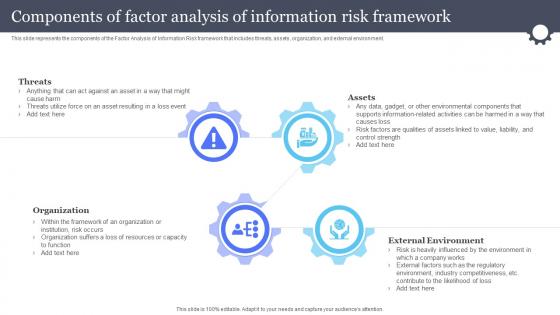

This slide represents the components of the Factor Analysis of Information Risk framework that includes threats, assets, organization, and external environment. Increase audience engagement and knowledge by dispensing information using Components Of Factor Analysis Of Information Information And Communications Governance Ict Governance. This template helps you present information on four stages. You can also present information on Components, Analysis, Framework using this PPT design. This layout is completely editable so personaize it now to meet your audiences expectations.

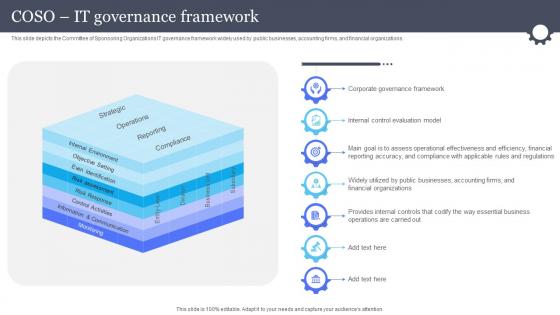

This slide depicts the Committee of Sponsoring Organizations IT governance framework widely used by public businesses, accounting firms, and financial organizations. Present the topic in a bit more detail with this Coso It Governance Framework Information And Communications Governance Ict Governance. Use it as a tool for discussion and navigation on Governance, Framework, Compliance . This template is free to edit as deemed fit for your organization. Therefore download it now.

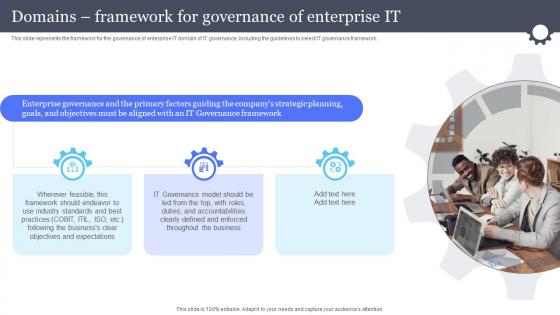

This slide represents the framework for the governance of enterprise IT domain of IT governance, including the guidelines to select IT governance framework. Introducing Domains Framework For Governance Of Enterprise It Information And Communications Governance Ict Governance to increase your presentation threshold. Encompassed with three stages, this template is a great option to educate and entice your audience. Dispence information on Framework, Governance, Enterprise, using this template. Grab it now to reap its full benefits.

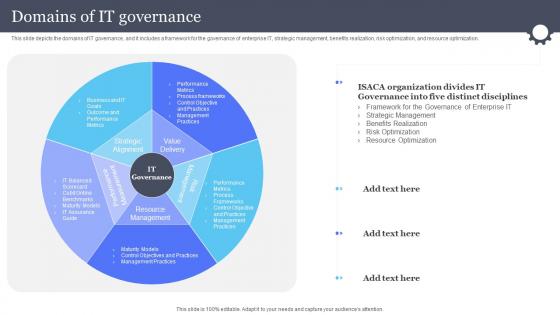

This slide depicts the domains of IT governance, and it includes a framework for the governance of enterprise IT, strategic management, benefits realization, risk optimization, and resource optimization. Present the topic in a bit more detail with this Domains Of It Governance Information And Communications Governance Ict Governance. Use it as a tool for discussion and navigation on Organization, Strategic, Management. This template is free to edit as deemed fit for your organization. Therefore download it now.

This slide represents the get executive sponsorship guideline for IT governance implementation in the company. It shows that the chief information officer and chief finance officer can be helpful for effective persuading. Introducing Effective Implementation Get Executive Sponsorship Information And Communications Governance Ict Governance to increase your presentation threshold. Encompassed with six stages, this template is a great option to educate and entice your audience. Dispence information on Implementation, Executive, Sponsorship, using this template. Grab it now to reap its full benefits.

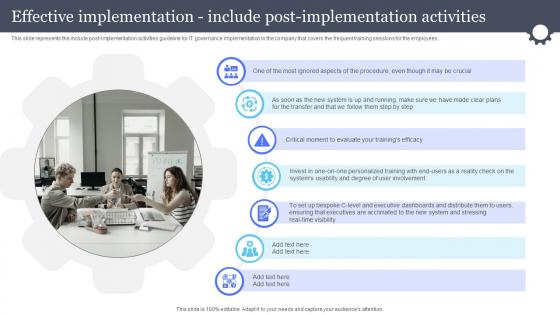

This slide represents the include post-implementation activities guideline for IT governance implementation in the company that covers the frequent training sessions for the employees. Increase audience engagement and knowledge by dispensing information using F711 Effective Implementation Include Implementation Information And Communications Governance Ict Governance. This template helps you present information on seven stages. You can also present information on Effective Implementation, Executive Dashboards, Executives using this PPT design. This layout is completely editable so personaize it now to meet your audiences expectations.

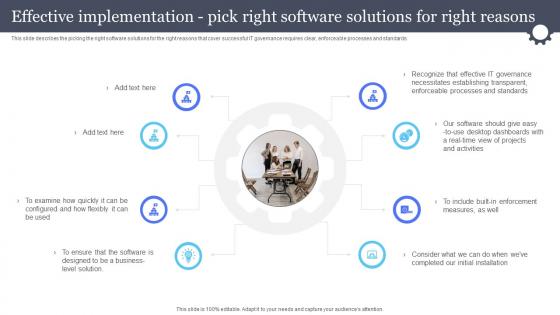

This slide describes the picking the right software solutions for the right reasons that cover successful IT governance requires clear, enforceable processes and standards. Introducing F712 Effective Implementation Pick Right Software Information And Communications Governance Ict Governance to increase your presentation threshold. Encompassed with eight stages, this template is a great option to educate and entice your audience. Dispence information on Effective, Implementation, Software Solutions, using this template. Grab it now to reap its full benefits.

This slide depicts the put client resources on the team guideline for IT governance implementation in the organization that describes that solid connections and collaboration across the company are essential for success. Increase audience engagement and knowledge by dispensing information using F713 Effective Implementation Put Client Resources Team Information And Communications Governance Ict Governance. This template helps you present information on five stages. You can also present information on Resources, Effective Implementation, Business using this PPT design. This layout is completely editable so personaize it now to meet your audiences expectations.

This slide outlines the take small steps guideline for effective IT governance implementation that focuses on small details such as training employees to match the pace of employees to adapt to the new system. Introducing F714 Effective Implementation Take Small Steps Information And Communications Governance Ict Governance to increase your presentation threshold. Encompassed with eight stages, this template is a great option to educate and entice your audience. Dispence information on Organization, Demonstrate, Acceptance, using this template. Grab it now to reap its full benefits.

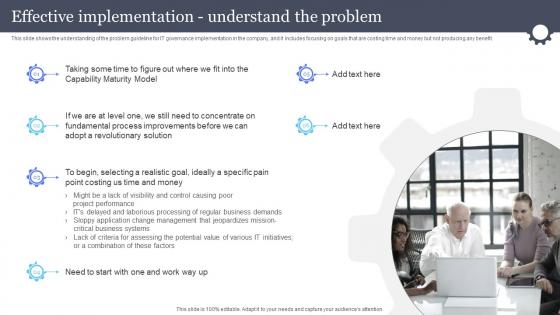

This slide shows the understanding of the problem guideline for IT governance implementation in the company, and it includes focusing on goals that are costing time and money but not producing any benefit. Increase audience engagement and knowledge by dispensing information using F715 Effective Implementation Understand The Problem Information And Communications Governance Ict Governance. This template helps you present information on six stages. You can also present information on Effective Implementation, Revolutionary Solution, Business using this PPT design. This layout is completely editable so personaize it now to meet your audiences expectations.

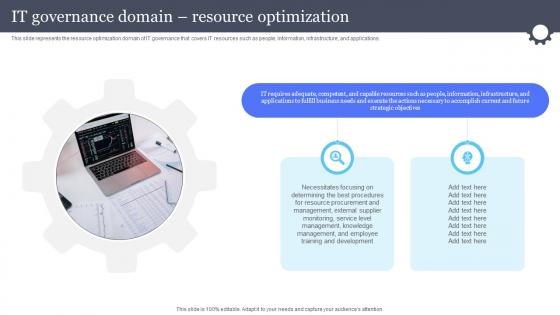

This slide represents the resource optimization domain of IT governance that covers IT resources such as people, information, infrastructure, and applications. Introducing F716 It Governance Domain Resource Optimization Information And Communications Governance Ict Governance to increase your presentation threshold. Encompassed with two stages, this template is a great option to educate and entice your audience. Dispence information on Resource, Optimization, Governance Domain, using this template. Grab it now to reap its full benefits.

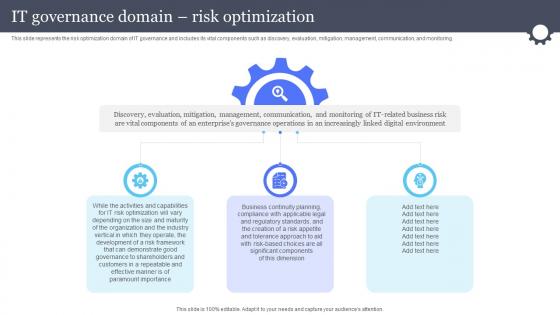

This slide represents the risk optimization domain of IT governance and includes its vital components such as discovery, evaluation, mitigation, management, communication, and monitoring. Increase audience engagement and knowledge by dispensing information using F717 It Governance Domain Risk Optimization Information And Communications Governance Ict Governance. This template helps you present information on three stages. You can also present information on Optimization, Environment, Communication using this PPT design. This layout is completely editable so personaize it now to meet your audiences expectations.

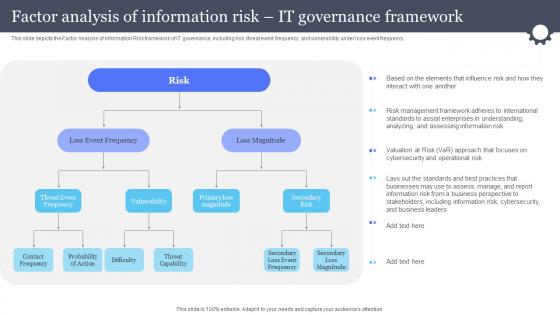

This slide depicts the Factor Analysis of Information Risk framework of IT governance, including risk, threat event frequency, and vulnerability under loss event frequency. Present the topic in a bit more detail with this Factor Analysis Of Information Risk It Governance Information And Communications Governance Ict Governance. Use it as a tool for discussion and navigation on Governance, Framework, Information. This template is free to edit as deemed fit for your organization. Therefore download it now.

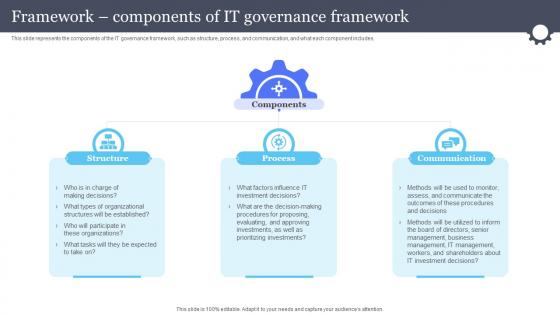

This slide represents the components of the IT governance framework, such as structure, process, and communication, and what each component includes. Increase audience engagement and knowledge by dispensing information using Framework Components Of It Governance Framework Information And Communications Governance Ict Governance. This template helps you present information on three stages. You can also present information on Framework, Communication, Structure using this PPT design. This layout is completely editable so personaize it now to meet your audiences expectations.

Present the topic in a bit more detail with this Icons Slide For Information And Communications Technology Governance Ict Governance. Use it as a tool for discussion and navigation on Icons. This template is free to edit as deemed fit for your organization. Therefore download it now.

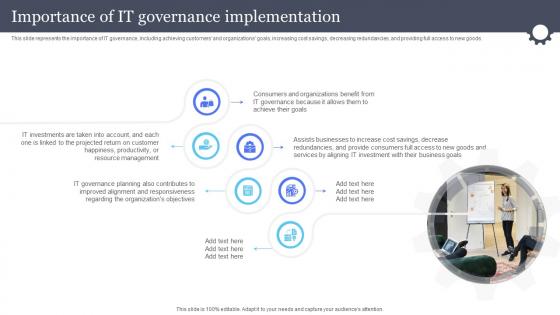

This slide represents the importance of IT governance, including achieving customers and organizations goals, increasing cost savings, decreasing redundancies, and providing full access to new goods. Introducing Importance Of It Governance Implementation Information And Communications Governance Ict Governance to increase your presentation threshold. Encompassed with six stages, this template is a great option to educate and entice your audience. Dispence information on Governance, Implementation, Business Goals, using this template. Grab it now to reap its full benefits.

This slide represents the envision of the solution guideline for IT governance implementation that caters to considering what we want to accomplish initially and setting high goals. Increase audience engagement and knowledge by dispensing information using Information And Communications Governance Ict Governance Effective Implementation Envision The Solution. This template helps you present information on eight stages. You can also present information on Demoralizes, Individuals, Strategy, Success using this PPT design. This layout is completely editable so personaize it now to meet your audiences expectations.

This slide depicts the benefits realization domain of IT governance that includes the appropriate management of IT-enabled investments for achieving optimal business outcomes. Introducing Information And Communications Governance Ict Governance It Governance Domain Benefits Realization to increase your presentation threshold. Encompassed with three stages, this template is a great option to educate and entice your audience. Dispence information on Realization, Governance, Business, using this template. Grab it now to reap its full benefits.

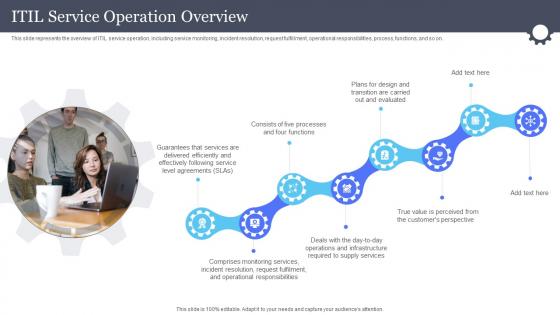

This slide represents the overview of ITIL service operation, including service monitoring, incident resolution, request fulfillment, operational responsibilities, process, functions, and so on. Increase audience engagement and knowledge by dispensing information using Information And Communications Governance Ict Governance Itil Service Operation Overview. This template helps you present information on eight stages. You can also present information on Agreements, Services, Responsibilities using this PPT design. This layout is completely editable so personaize it now to meet your audiences expectations.

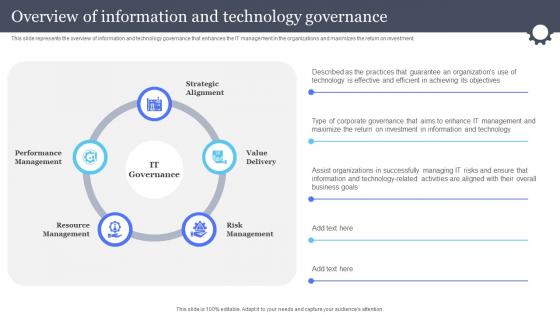

This slide represents the overview of information and technology governance that enhances the IT management in the organizations and maximizes the return on investment. Introducing Information And Communications Governance Ict Governance Overview Of Information And Technology to increase your presentation threshold. Encompassed with five stages, this template is a great option to educate and entice your audience. Dispence information on Technology, Governance, Information, using this template. Grab it now to reap its full benefits.

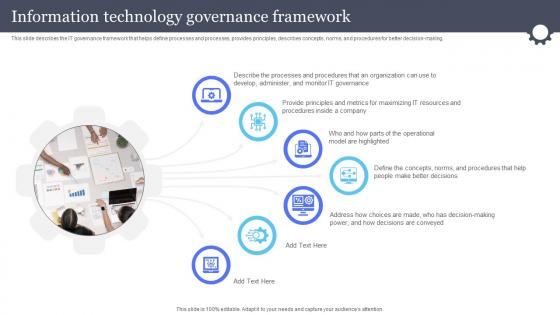

This slide describes the IT governance framework that helps define processes and processes, provides principles, describes concepts, norms, and procedures for better decision-making. Introducing Information Technology Governance Information And Communications Governance Ict Governance to increase your presentation threshold. Encompassed with seven stages, this template is a great option to educate and entice your audience. Dispence information on Technology, Governance, Framework, using this template. Grab it now to reap its full benefits.

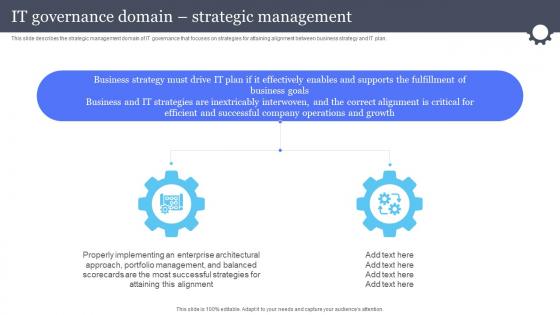

This slide describes the strategic management domain of IT governance that focuses on strategies for attaining alignment between business strategy and IT plan. Increase audience engagement and knowledge by dispensing information using It Governance Domain Strategic Management Information And Communications Governance Ict Governance. This template helps you present information on two stages. You can also present information on Strategic, Management, Governance using this PPT design. This layout is completely editable so personaize it now to meet your audiences expectations.

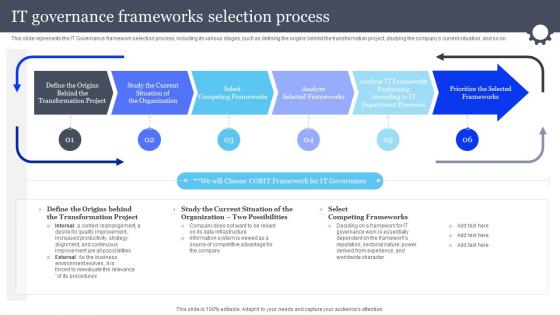

This slide represents the IT Governance framework selection process, including its various stages, such as defining the origins behind the transformation project, studying the companys current situation, and so on. Introducing It Governance Frameworks Selection Process Information And Communications Governance Ict Governance to increase your presentation threshold. Encompassed with six stages, this template is a great option to educate and entice your audience. Dispence information on Process, Governance, Frameworks, using this template. Grab it now to reap its full benefits.

This slide represents the post-implementation impact on IT governance on the business. It includes alignment and responsiveness, objective decision making, resources balancing, organizational risk management, and execution and enforcement. Increase audience engagement and knowledge by dispensing information using It Governance Post Implementation Impact Information And Communications Governance Ict Governance. This template helps you present information on five stages. You can also present information on Responsiveness, Resource Balancing, Organizational Risk Management using this PPT design. This layout is completely editable so personaize it now to meet your audiences expectations.

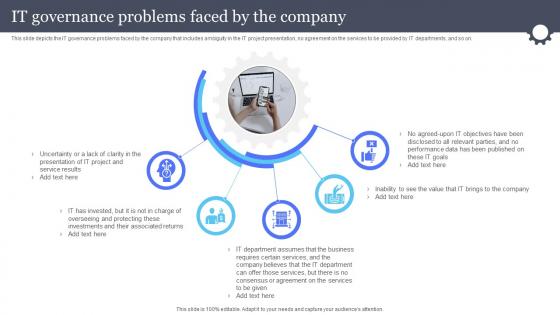

This slide depicts the IT governance problems faced by the company that includes ambiguity in the IT project presentation, no agreement on the services to be provided by IT departments, and so on. Introducing It Governance Problems Faced By The Company Information And Communications Governance Ict Governance to increase your presentation threshold. Encompassed with five stages, this template is a great option to educate and entice your audience. Dispence information on Governance, Departments, Agreement, using this template. Grab it now to reap its full benefits.

This slide depicts the IT governance, risk management, and compliance, including key IT decisions, decision models, IT governance structure, processes and policies and standards, and so on. Increase audience engagement and knowledge by dispensing information using It Governance Risk Management And Compliance Information And Communications Governance Ict Governance. This template helps you present information on three stages. You can also present information on Governance Framework, Interface With Operational IT, Compliance using this PPT design. This layout is completely editable so personaize it now to meet your audiences expectations.

This slide defines the overview of ITILs continual service improvement, including tracking and assessing IT service performance, efficiency-boosting, cost-effectiveness, etc. Introducing Itil Continual Service Improvement Overview Information And Communications Governance Ict Governance to increase your presentation threshold. Encompassed with six stages, this template is a great option to educate and entice your audience. Dispence information on Improvement, Overview, Effectiveness, using this template. Grab it now to reap its full benefits.

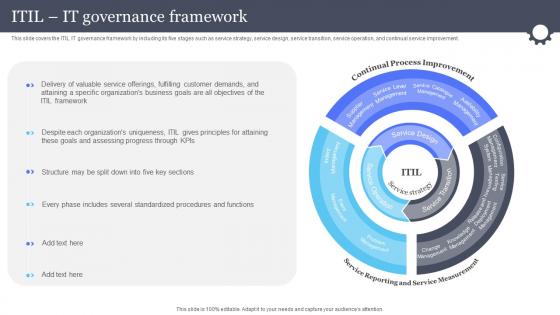

This slide covers the ITIL IT governance framework by including its five stages such as service strategy, service design, service transition, service operation, and continual service improvement. Present the topic in a bit more detail with this Itil It Governance Framework Information And Communications Governance Ict Governance. Use it as a tool for discussion and navigation on Governance, Framework, Improvement. This template is free to edit as deemed fit for your organization. Therefore download it now.

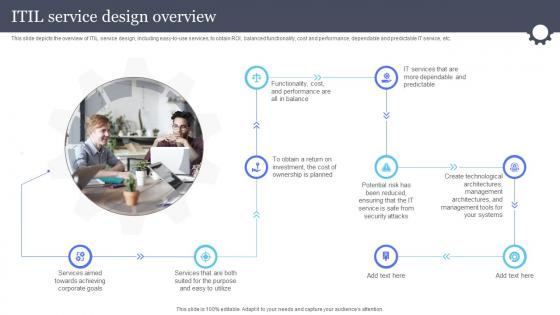

This slide depicts the overview of ITIL service design, including easy-to-use services, to obtain ROI, balanced functionality, cost and performance, dependable and predictable IT service, etc. Increase audience engagement and knowledge by dispensing information using Itil Service Design Overview Information And Communications Governance Ict Governance. This template helps you present information on nine stages. You can also present information on Services, Performance, Investment using this PPT design. This layout is completely editable so personaize it now to meet your audiences expectations.

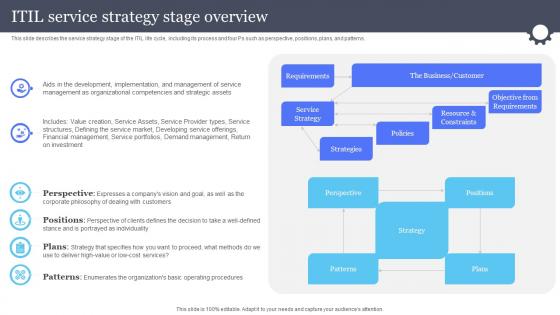

This slide describes the service strategy stage of the ITIL life cycle, including its process and four Ps such as perspective, positions, plans, and patterns. Deliver an outstanding presentation on the topic using this Itil Service Strategy Stage Overview Information And Communications Governance Ict Governance. Dispense information and present a thorough explanation of Service, Strategy, Overview using the slides given. This template can be altered and personalized to fit your needs. It is also available for immediate download. So grab it now.

This slide gives the overview of ITIL service transition, including the method of creating a strategy to deliver services, organization and coordination of activities and functions, and so on. Increase audience engagement and knowledge by dispensing information using Itil Service Transition Overview Information And Communications Governance Ict Governance. This template helps you present information on six stages. You can also present information on Transition, Overview, Production using this PPT design. This layout is completely editable so personaize it now to meet your audiences expectations.

This slide represents the levels of capability maturity model integrated, including its levels such as initial, repeatable, defined, managed, and optimizing. Deliver an outstanding presentation on the topic using this Levels Of Capability Maturity Model Integrated Information And Communications Governance Ict Governance. Dispense information and present a thorough explanation of Requirements Management, Software Configuration Management, Subcontract Management using the slides given. This template can be altered and personalized to fit your needs. It is also available for immediate download. So grab it now.

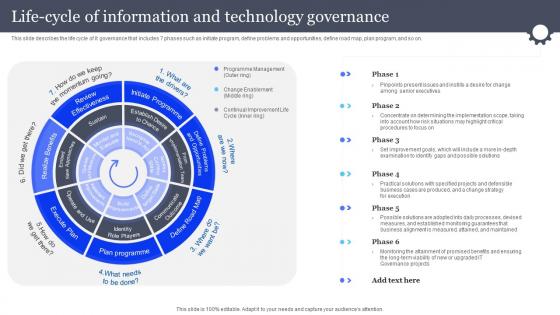

This slide describes the life cycle of It governance that includes 7 phases such as initiate program, define problems and opportunities, define road map, plan program, and so on. Present the topic in a bit more detail with this Life Cycle Of Information And Technology Information And Communications Governance Ict Governance. Use it as a tool for discussion and navigation on Information, Technology, Governance. This template is free to edit as deemed fit for your organization. Therefore download it now.

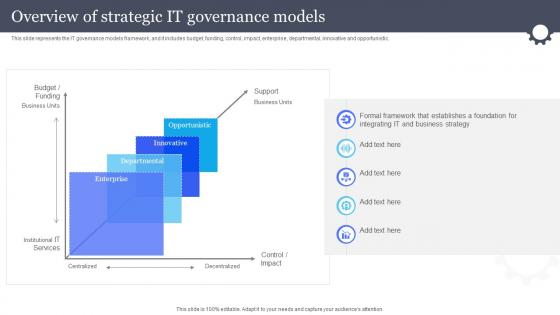

This slide represents the IT governance models framework, and it includes budget, funding, control, impact, enterprise, departmental, innovative and opportunistic. Deliver an outstanding presentation on the topic using this Overview Of Strategic It Governance Models Information And Communications Governance Ict Governance. Dispense information and present a thorough explanation of Overview, Strategic, Governance using the slides given. This template can be altered and personalized to fit your needs. It is also available for immediate download. So grab it now.

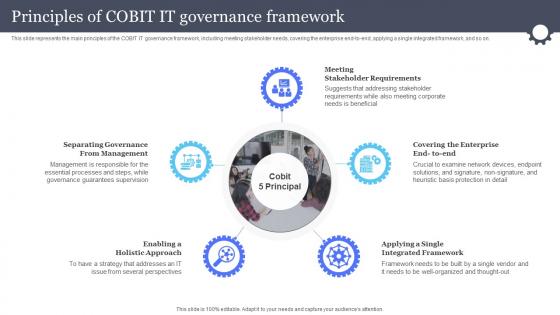

This slide represents the main principles of the COBIT IT governance framework, including meeting stakeholder needs, covering the enterprise end-to-end, applying a single integrated framework, and so on. Introducing Principles Of Cobit It Governance Framework Information And Communications Governance Ict Governance to increase your presentation threshold. Encompassed with five stages, this template is a great option to educate and entice your audience. Dispence information on Governance Framework, Stakeholder Requirements, Integrated Framework, using this template. Grab it now to reap its full benefits.

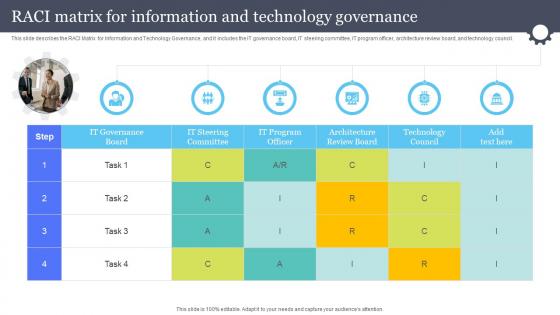

This slide describes the RACI Matrix for Information and Technology Governance, and it includes the IT governance board, IT steering committee, IT program officer, architecture review board, and technology council. Deliver an outstanding presentation on the topic using this Raci Matrix For Information And Technology Information And Communications Governance Ict Governance. Dispense information and present a thorough explanation of Technology, Governance, Information using the slides given. This template can be altered and personalized to fit your needs. It is also available for immediate download. So grab it now.

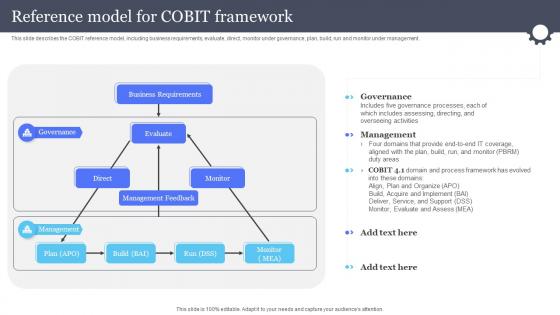

This slide describes the COBIT reference model, including business requirements, evaluate, direct, monitor under governance, plan, build, run and monitor under management. Deliver an outstanding presentation on the topic using this Reference Model For Cobit Framework Information And Communications Governance Ict Governance. Dispense information and present a thorough explanation of Governance, Management, Framework using the slides given. This template can be altered and personalized to fit your needs. It is also available for immediate download. So grab it now.

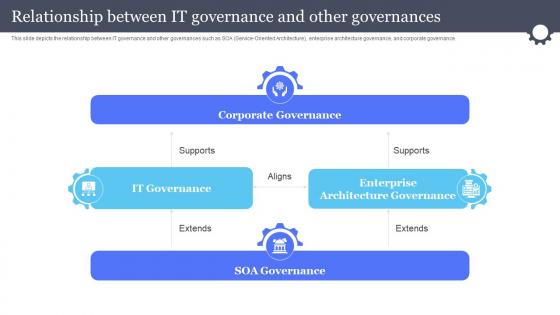

This slide depicts the relationship between IT governance and other governances such as SOA Service-Oriented Architecture, enterprise architecture governance, and corporate governance. Present the topic in a bit more detail with this Relationship Between It Governance And Other Information And Communications Governance Ict Governance. Use it as a tool for discussion and navigation on Governances, Relationship, Corporate. This template is free to edit as deemed fit for your organization. Therefore download it now.

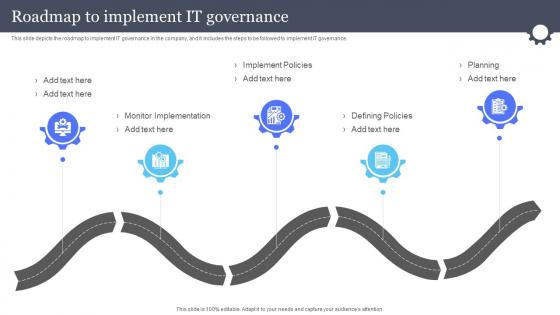

This slide depicts the roadmap to implement IT governance in the company, and it includes the steps to be followed to implement IT governance. Introducing Roadmap To Implement It Governance Information And Communications Governance Ict Governance to increase your presentation threshold. Encompassed with five stages, this template is a great option to educate and entice your audience. Dispence information on Monitor Implementation, Implement Policies, Defining Policies, using this template. Grab it now to reap its full benefits.

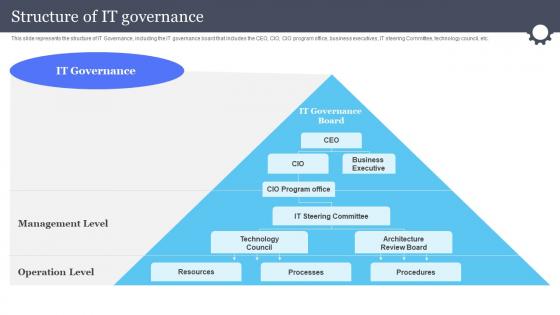

This slide represents the structure of IT Governance, including the IT governance board that includes the CEO, CIO, CIO program office, business executives, IT steering Committee, technology council, etc. Deliver an outstanding presentation on the topic using this Structure Of It Governance Information And Communications Governance Ict Governance. Dispense information and present a thorough explanation of Structure, Governance, Management Level using the slides given. This template can be altered and personalized to fit your needs. It is also available for immediate download. So grab it now.

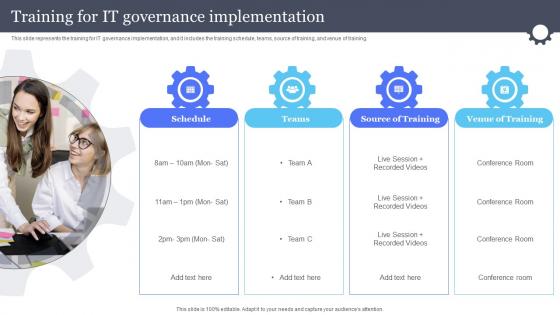

This slide represents the training for IT governance implementation, and it includes the training schedule, teams, source of training, and venue of training. Deliver an outstanding presentation on the topic using this Training For It Governance Implementation Information And Communications Governance Ict Governance. Dispense information and present a thorough explanation of Governance, Implementation, Represents using the slides given. This template can be altered and personalized to fit your needs. It is also available for immediate download. So grab it now.

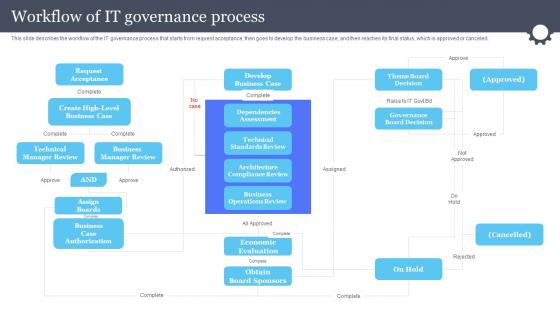

This slide describes the workflow of the IT governance process that starts from request acceptance, then goes to develop the business case, and then reaches its final status, which is approved or canceled. Present the topic in a bit more detail with this Workflow Of It Governance Process Information And Communications Governance Ict Governance. Use it as a tool for discussion and navigation on Governance, Process, Business. This template is free to edit as deemed fit for your organization. Therefore download it now.

Present the topic in a bit more detail with this F720 Information And Communications Technology Governance Ict Governance Table Of Contents. Use it as a tool for discussion and navigation on Governance Implementation, Communications, Technology This template is free to edit as deemed fit for your organization. Therefore download it now.

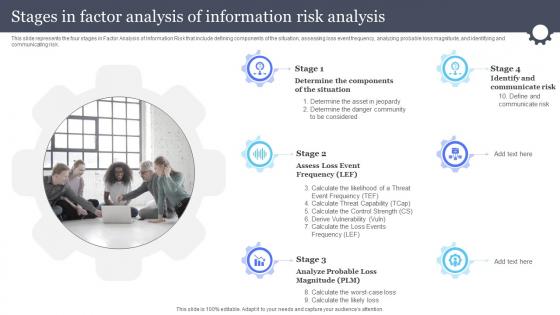

This slide represents the four stages in Factor Analysis of Information Risk that include defining components of the situation, assessing loss event frequency, analyzing probable loss magnitude, and identifying and communicating risk. Increase audience engagement and knowledge by dispensing information using Information And Communications Governance Ict Governance Stages In Factor Analysis Of Information. This template helps you present information on six stages. You can also present information on Analysis, Information, Situation using this PPT design. This layout is completely editable so personaize it now to meet your audiences expectations.

This slide represents need for information and communications technology ICT in businesses. It includes communication, data management, marketing, automation etc.Present the topic in a bit more detail with this Need For Information And Communications Implementation Of ICT Strategic Plan Strategy SS. Use it as a tool for discussion and navigation on Programmatic Advertising, Management Software, Response Systems. This template is free to edit as deemed fit for your organization. Therefore download it now.

28 Free Technology PowerPoint Templates for Presentations from the Future

- Share on Facebook

- Share on Twitter

By Lyudmil Enchev

in Freebies

3 years ago

Viewed 235,647 times

Spread the word about this article:

If you’re amongst the science and technology teachers, students, or businesses in the field; we have something for you. We deep-dived to find the best free technology PowerPoint templates for your presentation, so today’s collection has 28 amazing designs to choose from.

The following selection has templates related to science, technology, cybersecurity, search engines, bitcoin, networking, programming, and engineering, so there’s something for everyone.

1. Computer Hardware Free Technology PowerPoint Template

This template sports a cool design with a bright light of a microchip processor and a blue background. Ideal for explaining concepts such as semiconductors, databases, and central computer processors.

- Theme : Technology, Hardware

- Slides : 48

- Customization : Fully editable + 136 editable icons

- Graphics : Vector

- Aspect Ratio : 16:9

- License : Free for Personal and Commercial Use │ Do Not Redistribute Any Components of the Template

2. Space Science Free Technology Powerpoint Templates

This free template has 3D spaceship graphics and blue background color. It’s great for presentations on astronomy.

- Theme : Technology, Cosmos

- Slides : 25

- Customization : Fully editable

- Resolution : 1920×1080

3. 5G Technology Speed Free Powerpoint Templates

Design with twinkling rays of geometric shapes is perfect for presentations on technology topics such as internet networking, intranet, and communication technology.

- Theme : Technology, Networking, 5G

- Customization : Editable

4. Start-Up Tech Corporation Free Powerpoint Template

This free tech corporation template is great for presentations on tech business startups.

- Theme : Technology, Tech Business, Start-Up Companies

5. App Startup Free Powerpoint Technology Template

This design is great for presentations on communication, mobile technology, and other digital devices used for the PPT presentations.

- Theme : Technology, Apps, Software

6. Cloud Technology Free Powerpoint Template

A technology template with a clean and modern design for your presentations about cloud computing and other computing services.

- Theme : Cloud Technlogy

7. Artificial Intelligence High Technology Free PowerPoint Template

This template represents artificial intelligence as an illustration . It also includes related shapes to allow for a variety of expressions.

- Theme : Technology, Artificial Intelligence

8. Search Engine Optimization PowerPoint Template

The template is SEO-themed but you can adapt it to any presentation related to marketing and search engines.

- Theme : Technology, Marketing, SEO

9. Binary Code Free PowerPoint Template

The cool binary code design makes this template perfect for any presentation on computer science.

- Theme : Computer Science, Programming

10. Network Free Technology PowerPoint Template

Sporting design with crags and electric rays in many angles are representing networking around the globe, the template is suitable for presentations on communication, networking, technology, and crag wheels.

- Theme : Technology, Networking

11. Hexagonal Design Free PowerPoint Template

Here we have a free template with hexagons and icons pattern for techy content. Its dark background and bright blue color palette give a professional look.

- Theme : Technology

12. Technology Pixels Free PowerPoint Template

A technology-themed template for presentations on consulting, IT, software, and other related subjects. The pixel pattern is grouped by tones which you can change from the master slides.

13. Connections and Networking Free PowerPoint Template

This free Powerpoint template is perfect for a presentation about the internet, blockchain, machine learning, cybersecurity, or cloud computing.

14. Isometric Free Technology PowerPoint Template

Here we have an amazing isometric design and high-tech background with gradients. Ideal for subjects like cloud computing, SaaS development, servers, and networks, or cybersecurity.

- Theme : Networking, Programming

15. Free PowerPoint Template with Techy Contour Lines

This design has an abstract contour lines background in a dark green color. Ideal for subjects like geography, technology, video games, or even military affairs.

- Theme : Technology, Gaming

16. Marketing and Technology Free PowerPoint Template

The isometric design has illustrations on business, marketing, and technology topics that will make every slide stand out.

- Theme : Technology, Marketing

17. Purple Hexagons Free PowerPoint Template

For presentations related to scientific or technological topics, with professional hexagonal design.

- Theme : Technology, Science

18. Rockets Taking Off Free PowerPoint Template

Rockets taking off is a great metaphor for growing businesses. It’s also a symbol of progress and technology.

- Slides : 35

19. IOT Smart City Free PowerPoint Template

Smart City offers a futuristic design for subjects such as internet communication, smart city concepts, and tech innovation.

- Theme : Technology, Smart City

20. Cyber Security Free PowerPoint Template

The perfect template for presentations on cybersecurity, antivirus software, and other related topics.

- Theme : Technology, Cyber Security

21. BlockChain Free PowerPoint Templates

This template is a 3D rendering design of blockchain technology and you can use it for a variety of purposes.

Presentation Design Tips You Wish You Knew Earlier:

The shorter you keep the text, the better. In fact, some specialists suggest that you shouldn’t use more than 5-6 words per slide . And sometimes, a single word combined with a powerful visual is enough to nail the attention of the people sitting in front of you and make them listen to what you have to say.

22. BitCoin Themed Free PowerPoint Template

A very versatile template that includes 20 semi-transparent illustrations of different concepts: security, social networks, programming, bitcoin.

- Theme : Technology, Bitcoin

23. Technical Blueprint Free Technology PowerPoint Template

This template uses a blueprint style and a monospaced font to emulate the technical drawings used in construction and industry.

- Theme : Technology, Engineering

24. Blue Connections Free PowerPoint Template

The design of this free template fits social media, connection, internet, cloud computing, and science-related topics.

- Theme : Technology, Social Media

25. Cute Robots Free PowerPoint Template

Here we have a colorful design with beautifully illustrated robots for presentation on technology, science, and physics.

- Theme : Technology, Physics

26. Green Circuit Free PowerPoint Template

This is a free template with futuristic vibes that you can use for your tech presentations both in PowerPoint and Google Slides.

27. Data Particles Free Technology PowerPoint Template

The design with particle lines gives it a modern and slightly technological look.

28. Science Hexagons Free Technology PowerPoint Template

The background gradients highlight the white text, and the hexagons give it a techie style.

Final Words

That’s it. Today’s collection covered the best free technology PowerPoint templates that you can download and adapt to your presentations related to science, technology, programming, engineering, and physics. Now all you need to do is open your PowerPoint and make the most amazing presentation your viewers have ever seen.

For more freebies, you can check the Best Free Powerpoint Templates of 2022 or see these related articles:

- 36 Free Food PowerPoint Templates For Delicious Presentations

- 31 Free Modern Powerpoint Templates for Your Presentation

- 25 Free Education PowerPoint Templates For Lessons, Thesis, and Online Lectures

Add some character to your visuals

Cartoon Characters, Design Bundles, Illustrations, Backgrounds and more...

Like us on Facebook

Subscribe to our newsletter

Be the first to know what’s new in the world of graphic design and illustrations.

- [email protected]

Browse High Quality Vector Graphics

E.g.: businessman, lion, girl…

Related Articles

Website backgrounds: 18 sources to find the perfect background, 120+ free food illustrations for personal and commercial garnishing, how to get started with powerpoint + guide and resources, 40 free cartoon robot characters for you epic high-tech designs, free gifs for powerpoint to animate your killer presentation, 500+ free and paid powerpoint infographic templates:, enjoyed this article.

Don’t forget to share!

- Comments (0)

Lyudmil Enchev

Lyudmil is an avid movie fan which influences his passion for video editing. You will often see him making animations and video tutorials for GraphicMama. Lyudmil is also passionate for photography, video making, and writing scripts.

Thousands of vector graphics for your projects.

Hey! You made it all the way to the bottom!

Here are some other articles we think you may like:

Free Vectors

Free car vectors: the best logos, banners, illustrations to download now.

by Lyudmil Enchev

30+ Free Presentation Clipart Graphics and Resources for Great PowerPoint Visuals

by Al Boicheva

35+ Free Infographic PowerPoint Templates to Power Your Presentations

by Iveta Pavlova

Looking for Design Bundles or Cartoon Characters?

A source of high-quality vector graphics offering a huge variety of premade character designs, graphic design bundles, Adobe Character Animator puppets, and more.

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Unit 1-Introduction to ICT. An Image/Link below is provided (as is) to download presentation Download Policy: Content on the Website is provided to you AS IS for your information and personal use and may not be sold / licensed / shared on other websites without getting consent from its author. Download presentation by click this link.

Slide 1 of 83. Information And Communications Technology Governance Ict Governance Powerpoint Presentation Slides. This complete presentation has PPT slides on wide range of topics highlighting the core areas of your business needs. It has professionally designed templates with relevant visuals and subject driven content.

Create impactful presentations with these IT PowerPoint templates. Perfect for tech professionals, students, and educators, these templates will help you convey your message in a clear and engaging way. With a range of customizable slides, you can easily manage your lessons and workshops, and make learning dynamic and attractive.

19. Scrum Process PowerPoint Presentation Template – Illustrate the Future of Software Development: Scrum using this Premium Information Technology PowerPoint Template. The Scrum Process PPT Presentation Template is a great way to present your company’s unique process for delivering products and services.

Lesson-1.-Introduction-to-ICT.pptx - Free download as Powerpoint Presentation (.ppt / .pptx), PDF File (.pdf), Text File (.txt) or view presentation slides online. Scribd is the world's largest social reading and publishing site.

4. Dyfo Technology Theme PowerPoint Template. A stark purple and black color scheme brings the audience's focus to your technology slide designs. Dyfo also includes one of the best bonuses for a tech PowerPoint template: p lenty of charts and graphs to show data.

1. Computer Hardware Free Technology PowerPoint Template. This template sports a cool design with a bright light of a microchip processor and a blue background. Ideal for explaining concepts such as semiconductors, databases, and central computer processors. Theme: Technology, Hardware. Slides: 48.

Powerpoint Presentation for ICT - Free download as Powerpoint Presentation (.ppt / .pptx), PDF File (.pdf), Text File (.txt) or view presentation slides online. This document provides information on using PowerPoint effectively in classroom presentations. It discusses best practices for slideshow construction and delivery, such as avoiding ...