2 Climate Change as a Social Problem

Scientists believe global climate change is the greatest challenge humanity has ever faced. But what exactly is climate change? What causes climate change? Why is it a social problem and not just an environmental problem?

Climate change refers to the long-term shift in global and regional temperatures, humidity and rainfall patterns, and other atmospheric characteristics. Unlike changes in weather that occur on a local level that can be measured in hourly, daily, or weekly fluctuations, climate change refers to longer-term fluctuations (both regionally or globally) that take place over a time scale of seasons, years, or even decades.

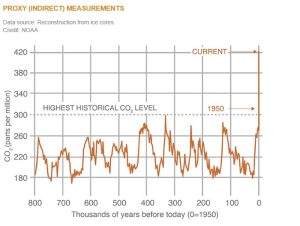

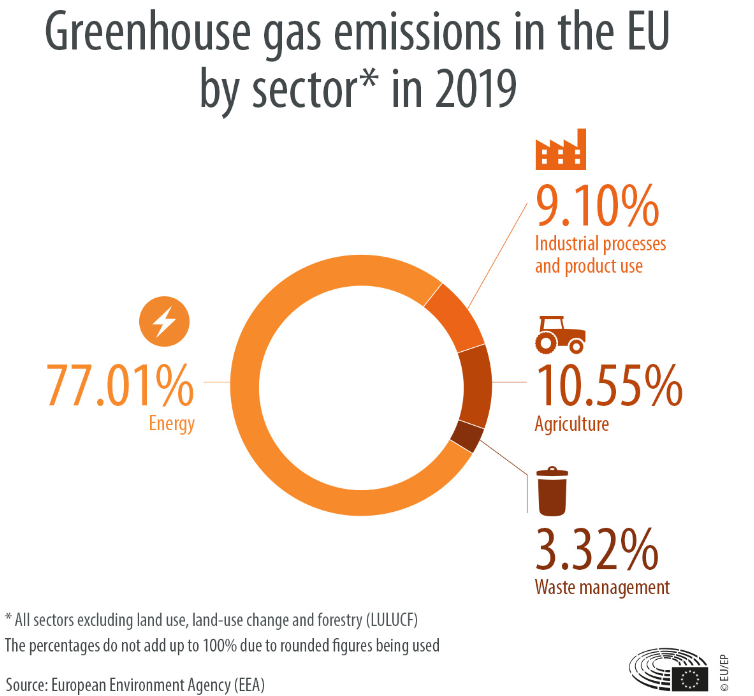

In the past two centuries, an exponential increase in carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases have been released into the earth’s atmosphere, as the chart in figure 8.3 shows. Although there are some natural processes that affect the earth’s climate, such as volcanic eruptions, the vast majority of scientists worldwide attribute the speed at which global warming has recently occurred to human activity, most notably the burning of fossil fuels. Scientists examine ocean sediments, ice cores, tree rings, and changes in glaciers to understand variations in Earth’s climate over time.

Figure 8.3. This graph shows the level of Carbon dioxide (CO2) over time. Although some fluctuation is normal, CO2 levels have never been as high as they are now. The change is predominantly caused by burning fossil fuels like coal, oil, and gas.

The Industrial Revolution is one reason for the increased carbon dioxide in the atmosphere. Since the Industrial Revolution, the concentration of greenhouse gasses is higher than at any other time in the past 800,000 years. This increase in greenhouse gasses is called the greenhouse effect ––an imbalance between the energy entering and leaving the earth’s atmosphere, resulting in a rise in global temperature. Because certain gasses absorb energy, such as carbon dioxide and methane, they trap heat and prevent it from being released into space, causing a rise in global temperature. The burning of fossil fuels is not the only human activity contributing to the greenhouse effect. Other activities such as deforestation, urbanization, and unsustainable agricultural practices contribute to global climate change.

So, climate change is a social problem because humans are causing the problem and are differently impacted by the problem. A social problem is a social condition or pattern of behavior that has negative consequences for individuals, our social world, or our physical world. Early sociological definitions of social problems rarely included the phrase “our physical world.” Today, climate change itself drives the importance of adding this phrase. social problem

Climate change is a critical issue, no matter how we approach it. Scientists are studying how to minimize its effects on people and the environment more broadly and, with any hope, successfully plan for the uncertain future. We must first examine the various ways climate change is already a threat to societies and communities worldwide.

Extreme Weather Events

As you watch the news, you may notice that extreme weather events occur regularly around the world. Many scientists argue that these events are caused or at least made worse by climate change. An extreme weather event is defined by the severity of its effects or any weather event uncommon for a particular location. Some examples of these types of severe and unusual events in the U.S. include Hurricane Katrina in 2005, which killed over 1800 people and caused $125 billion in damage; Hurricane Sandy in 2012, the third-most destructive hurricane ever to hit the nation; and the 2020 and 2021 wildfires that engulfed the West Coast states due to severe and prolonged drought and heat waves.

One of the most serious concerns Indigenous communities and other residents had about the Jordan Cove Energy Project discussed at the beginning of this chapter was the risk of a highly explosive gas pipeline being placed in a region increasingly inundated by annual wildfires. One of the large fires that swept through southern Oregon in September 2020 was located just a few miles from the planned route of the proposed pipelines, proving that the communities’ fears were valid.

And, as mentioned by communities of both Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples, climate change and mismanagement of forests will continue to create ripe conditions for unprecedented wildfires. In the Good Fire podcast , which you can listen to if you’d like, hosts Amy Cardinal Christianson and Matthew Kristoff, along with guest Frank Lake, discuss the landscape surrounding fire management:

Wildfire management has long been the domain of colonial governments. Despite a rich history of living with, managing, and using fire as a tool since time immemorial, Indigenous people were not permitted to practice cultural fire and their knowledge was largely ignored. As a result, total fire suppression became the prominent policy. With the most active force of natural succession abruptly halted, Indigenous communities suffered as the land changed. Today, western society has recognized the ecological problem a lack of fire has created, however, the cultural impact has been largely ignored. (Kristoff 2019)

The Indigenous knowledge that might have protected us against wildfires has been suppressed. It is another consequence of colonialism, an economic and political set of practices introduced in Chapter 5. Colonialism is not just a historical event. It is a structure of inequality that reproduces itself, even today (Wolfe 2006).

Cultural Loss

Figure 8.4. Salmon returning to their spawning grounds near Port Hope, Ontario, Canada. In the chapter’s next section, we will discuss what makes up a culture. How might access to salmon shape a culture? How might a lack of access to salmon impact that same culture?

Many cultures around the world are intimately connected to their environment. Certain foods, medicine, dance, and art are unique to places with particular animals, plants, or climates. With drastic temperature changes, extreme disasters, and biodiversity loss among plants and animals, people cannot practice many customs. This contributes to significant cultural loss around the world.

For example, salmon are an important symbol and food source for the Indigenous people in the Pacific Northwest (figure 8.4). The imagery of salmon in Indigenous art demonstrates a deep connection to natural surroundings. However, one effect of climate change is the warming of bodies of water worldwide. Like many fish, salmon require a specific temperature to spawn. As water temperatures increase, salmon cannot spawn as effectively or at all. This severely impacts species who eat salmon as a staple in their diet and the indigenous peoples who practice traditional methods of harvesting, crafting with, and cooking salmon.

Climate change can create cultural change or inhibit cultural expression.

Climate Change and Poverty: “Those who contribute the least suffer the most”

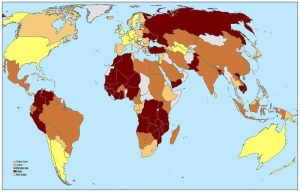

Figure 8.5. How vulnerable to climate change is your community? https://www.flickr.com/photos/theworldfishcenter/6143273940

This index combines a country’s vulnerability to climate change, and its readiness to improve resilience. Much of Africa is both vulnerable and not ready. Most of North America is less vulnerable and more ready. However, looking at this data by country hides vulnerabilities that are unique to communities.

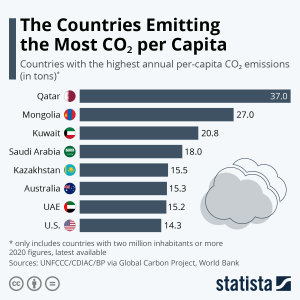

Figure 8.6. Countries with the highest annual per-capita CO2 emissions (in tons). https://www.statista.com/chart/20903/countries-emitting-most-co2-per-capita/

This image shows emissions of carbon dioxide, an emission that contributes to global warming. A common saying in the environmental movement is, “Those who contribute the least suffer the most.” This means that the poorest people use the least planetary resources, so they contribute to climate change the least. However, they suffer the most from climate change. We can see this as we compare the maps in figures 8.5 and 8.6. We see, for example, that Africa contributes the least greenhouse gasses, but they are the most vulnerable to climate change. The United States is a high contributor of emissions but the least vulnerable to climate change. While this model doesn’t hold true for every country, the saying encapsulates a key issue with climate change.

For example, with Hurricane Katrina in New Orleans, people with cars could evacuate. People without cars often couldn’t. People without cars contributed the least to CO2 emissions but experienced the most loss related to the extreme weather event (Bullard 2008).

You may have cheered with us as you learned that the Jordon Cove Energy Project pipeline project was shut down. However, the question remains: How else do we generate and transport our energy resources? Part of the answer is that the projects go where the resources exist, and the people are even more powerless to resist. Our unequal social locations contribute to inequality. To explore this further, we will look at the experience of people in Nigeria and oil production. We will build on the concept of socioeconomic class (SES) that we began in Chapter 4 .

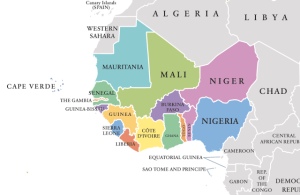

Figure 8.7. This map shows Nigeria, a country on the west coast of Africa. Nearly everyone there lives on less than $30.00 a day. Many people live on much less. How much do you think this country contributes to CO2 emissions?

Nigeria is a country on the western coast of Africa, as shown in figure 8.7. More than 40% of the people in Nigeria live in extreme poverty, defined as living on less than $1.40 per day (Cuaresma 2018). Less than 15% of the people have access to clean fuel for cooking (Ritchie 2021), and less than 60% of the people have access to sufficient electricity (Ritchie and Rosado 2021). At the same time, Nigeria is one of the world’s top oil exporters. Oil companies use a practice called gas flaring, burning the waste gas from oil exploration rather than disposing of it in other ways.

Figure 8.8. Gas flaring causes poor health in Nigeria.

Poor Nigerians experience rashes and sores because of the toxic fumes. In a recent study, children exposed to flaring experience coughs, respiratory issues, fevers, and other poor health symptoms. The rate of child deaths in children under five also slightly increases (Alimi and Gibson 2022: n.p.) The pollution contaminates the land, so women can’t grow enough food. Pollution also contaminates the water, leaving less for drinking and crop irrigation. One article notes that the women in the Niger Delta are poor because the environmental toxins are poisoning their plants. Women plant cassava to make their flour. However, the cassava roots are dying, and the women can’t replace them (Lawal 2021).

Many people are migrating to bigger cities, but it doesn’t solve the local pollution and emissions problem. The article, “ In Nigeria, Gas Giants Get Rich as Women Sink Into Poverty ” documents the story with more details, including pictures of the impacts of the gas flares, if you would like to learn more. We also notice that those who use the least resources are impacted the most. In this case, the environmental impact occurs on a different continent than most of the people using the oil. If you’d like to look more deeply into this problem, watch Who Is Responsible For Climate Change? – Who Needs To Fix It?

Licenses and Attributions for Climate Change as a Social Problem

| “Climate Change as a Social Problem” by Patricia Halleran, Kimberly Puttman, and Avery Temple, is licensed under . Figure 8.3: from Nasa Global Climate Change, Figure 8.8 by Alimi, Omoniyi, and John Gibson is used under Fair Use Figure 8.4 by . License: . Figure 8.5 by is licensed under Figure 8.6 by Katharina Buchholz is licensed under Figure 8.7 by is licensed under |

long-term shift in global and regional temperatures, humidity and rainfall patterns, and other atmospheric characteristics

an imbalance between the energy entering and leaving the earth’s atmosphere, resulting in a rise in global temperature

a social condition or pattern of behavior that has negative consequences for individuals, our social world, or our physical world

defined by the severity of its effects or any weather event uncommon for a particular location

Environmental Justice Copyright © by Deron Carter, Colleen Sanders, and Environmental Justice Students is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Social Dimensions of Climate Change

As the climate continues to change, millions of poor people face increasing challenges in terms of extreme events, health effects, food, water, and livelihood security, migration and forced displacement, loss of cultural identity, and other related risks.

Climate change is deeply intertwined with global patterns of inequality. The poorest and most vulnerable people bear the brunt of climate change impacts yet contribute the least to the crisis. As the impacts of climate change mount, millions of vulnerable people face disproportionate challenges in terms of extreme events, health effects, food, water, and livelihood security, migration and forced displacement, loss of cultural identity, and other related risks.

Certain social groups are particularly vulnerable to crises, for example, female-headed households, children, persons with disabilities , Indigenous Peoples and ethnic minorities, landless tenants, migrant workers, displaced persons, sexual and gender minorities , older people, and other socially marginalized groups. The root causes of their vulnerability lie in a combination of their geographical locations; their financial, socio-economic, cultural, and gender status; and their access to resources, services, decision-making power, and justice.

Poor and marginalized groups are calling for more ambitious action on climate change. Climate change is more than an environmental crisis – it is a social crisis and compels us to address issues of inequality on many levels: between wealthy and poor countries; between rich and poor within countries; between men and women, and between generations. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) has highlighted the need for climate solutions that conform to principles of procedural and distributive justice for more effective development outcomes.

The most vulnerable are often also disproportionately impacted by measures to address climate change. In the absence of well-designed and inclusive policies, efforts to tackle climate change can have unintended consequences for the livelihoods of certain groups, including by placing a higher financial burden on poor households. For example, policies that expand public transport or carbon pricing may lead to higher public transport fares which can disproportionately impact poorer households. Similarly, if not designed in collaboration with beneficiaries and affected communities, approaches such as limiting forestry activities to certain times of the year could adversely impact indigenous communities that depend on forests year-round for their livelihoods. In addition to addressing the distributional impacts of decarbonizing economies there is also a need to understand and address the social inclusion, cultural and political economy aspects – including agreeing on the types of transitions needed (economic, social, etc.) and identifying opportunities to address social inequality in these processes.

While much progress has been made on the science and the types of policies needed to support a transition to low carbon, climate resilient development, a challenge facing many countries is engaging citizens who may not understand climate change, and garnering the support of those who are concerned that they will be unfairly impacted by climate policies. It is critical that people are brought along in the choices to be made – this requires transparency, access to information and citizen engagement on climate risk and green growth in order to create coalitions of support or public demand to reduce climate impacts and to overcome behavioral and political barriers to decarbonization, as well as to generate new ideas for and ownership of solutions.

Moreover, communities bring unique perspectives, skills, and a wealth of knowledge to the challenge of strengthening resilience and addressing climate change. They should be engaged as partners in resilience-building rather than being regarded merely as beneficiaries. Research and experience have shown that community leaders can set priorities, influence ownership, and design and implement investment programs that are responsive to their community’s own needs. A recent IPCC report recognizes the value of diverse forms of knowledge such as scientific, Indigenous and local knowledge in building climate resilience. Innovations in the architecture of climate finance can connect communities and marginalized groups to the policy, technical and financial assistance that they need for locally relevant and effective development impacts.

Last Updated: Apr 01, 2023

The World Bank’s work to address the social dimensions of climate change (SDCC) has a strong focus on poverty reduction and on addressing the underlying causes of vulnerability, including social exclusion. The Bank adopts a whole-of-society approach, working with national and local governments, civil society, grassroots communities, and other partners to strengthen social resilience at the ground level, where the effects of climate change are typically felt the most, and to promote meaningful engagement of communities and other social groups in climate change decision-making and action.

The World Bank is committed to promoting socially equitable responses to global crises. As we adapt to a changing climate in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, it is important that we listen to, and learn from, people and communities. That is why a truly inclusive approach can often begin at the community level. Green recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic and transitioning to low-carbon, climate resilient development requires considering action on climate change in an immediate and broad social context and recognizing the urgency of present needs, while plotting an ambitious course to decarbonization. The World Bank supports achievement of these objectives through three key areas of activity:

Channeling resources and decision-making power to support locally-led climate action: Supporting devolved climate finance and community and local development approaches and that empower communities to drive a climate agenda in support of their development goals; promoting greater transparency and accountability on climate finance; aligning and linking locally led climate action to national climate change priorities and strategies; supporting work to strengthen M&E of resilience and adaptation.

Understanding and tracking the social impacts and social co-benefits of mitigation and green growth policies and programs: Supporting analysis and dialogue on what a “just transition” looks like across different sectors and in specific contexts; identifying and addressing the distributional and social inclusion impacts stemming from different approaches to decarbonization.

Facilitating processes needed to support key transitions: Engaging communities and citizens in climate decision-making and enhancing social learning as a form of regulatory feedback (e.g., citizen engagement, national climate dialogues, and improved governance); building awareness and political will amongst governments and partners on the need to understand and address the social dimensions of climate change and green growth.

Through these areas of action, the World Bank fosters strong collaboration across different practice areas to bring together and empower poor communities and marginalized social groups to reduce risks to future crises; and to bridge the gap between the local, subnational, and national levels for effective climate change support.

The World Bank has recognized the need to support locally led climate action and work with communities as equal partners so that we are building on their experience and expertise in managing risk and adapting to climate change and to transitions. In other sectors, the World Bank has invested in community and local development (CLD) operations that emphasize citizen control over investment development planning and decision making and implementation. For decades, CLD has effectively supported basic service delivery, livelihoods, social services, poverty reduction, and other community priorities at a large scale. Over $30 billion has been invested in CLD programs over the past decade. This same mechanism is now being harnessed and adapted to deliver effective, local climate resilience support at the necessary scale and its core principles of citizen control and social inclusion are being integrated into innovative approaches to decentralized climate finance.

In Kenya, the World Bank is working with the national and county governments to channel climate finance and decision-making to people at the local level to design solutions that meet their specific needs. Through the Financing Locally Led Climate Action program (FLLoCA), county governments are supported to work in partnership with communities to assess climate risks and identify socially inclusive solutions that are tailored to local needs and priorities. The FLLoCA Program in Kenya provides the first national-scale model of devolved climate finance that can be replicated in other countries.

In Bangladesh, the Nuton Jibon project considers extreme weather events in its design with communities who undertake participatory risk analyses, which then informs the locations and design of community centers, rural roads, tube wells, and other works.

The Bank’s support to recovery after Typhoon Yolanda in the Philippines was channeled through the National CDD Program so that communities could drive the decision-making process: The DAMPA (Damayan ng Maralitang Pilipinong Api) network consists of over 200 community-based women-led organizations representing rural and urban poor communities in the Philippines. It partnered with the government to monitor the delivery of disaster relief assistance after Typhoon Haiyan and facilitated community-based risk mapping to inform the prioritization and design of community-level investments of the National CDD Program.

CLD programs are also responding to the impact of COVID-19, including cash transfers for vulnerable groups and block grants to communities to reach vulnerable households with food and medical supplies. Lessons from previous pandemics, including the 2014-16 Ebola outbreak, highlight the importance of social responses to crisis management and recovery to complement medical efforts. In the case of COVID-19, partnerships between communities, healthcare systems, local governments, and the private sector have played a critical role in slowing the spread, mitigating impacts, and supporting local recovery.

The Somalia Crisis Response Project (SCRP) provides immediate support to areas hit by recent floods and droughts, in addition to response to COVID19 and building preparedness capacity for future risk management. The project will ensure women’s inclusion and participation in decision-making bodies, including participation in the development of the integrated community preparedness, adaptation, and response plans.

The World Bank also hosts the Climate Investment Funds , which is particularly relevant to the Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation plus (REDD+) agenda. Given their close relationships with and dependence on forested lands and resources, Indigenous Peoples are key stakeholders in CIF and REDD+. Specific initiatives in this sphere include: a Dedicated Grant Mechanism (DGM) for Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities under the Forest Investment Program (FIP) in multiple countries; a capacity building program oriented partly toward Forest-Dependent Indigenous Peoples by the Forest Carbon Partnership Facility (FCPF) ; support for enhanced participation of Indigenous peoples in benefit sharing of carbon emission reduction programs through the Enhancing Access to Benefits while Lowering Emissions (EnABLE) multi-donor trust fund; and analytical, strategic planning, and operational activities in the context of the FCPF and the BioCarbon Fund Initiative for Sustainable Forest Landscapes (ISFL).

Finally, more recent work is focusing on supporting just transitions in emerging economies and understanding the distributional and social inclusions impacts of green growth and decarbonization policies and investments. The goal of reaching net zero carbon emissions to mitigate the impacts of climate change is more urgent than ever. However, it is expected that the scaling down of industries and activities that most significantly contribute to carbon emissions will generate widespread impacts on the workers and the communities that depend on them. Ensuring a Just Transition for All means putting people and communities at the center of the transition process and promoting dialogue and participation at all levels of society throughout the entire transition, from planning to implementation. This entails ensuring socially inclusive approaches to transitions; garnering public support for complex transition processes; addressing the broader social, community, and cultural aspects of transition policies; supporting safe and successful migration where desired; and ensuring meaningful engagement of citizens in decision making.

While this work is still unfolding, it includes such activities as: mapping out the political economy of carbon-related sectors and identifying ways to engage stakeholders in sector reform; ensuring that projects are designed so that local communities can benefit equitably and meaningfully from green growth investments; undertaking gender and vulnerability analysis to identify gaps and ensuring the participation of women and underrepresented groups in decision making on green recovery programs; promoting transparency, access to information and citizen engagement on climate risk and green growth in order to create coalitions of support or public demand to reduce climate impacts; and, supporting local or national dialogues for just transition and green recovery decision making.

Social Sustainability & Inclusion

Climate Change at the World Bank

[BRIEF] Just Transition for All

[BLOG] To protect nature, put local communities at the center of climate action

[BLOG] Kenya moves to locally led climate action

[PRESS RELEASE] New US$150 Million Program to Strengthen Kenya’s Resilience to Climate Change

[PRESS RELEASE] World Bank Group Increases Support for Climate Action in Developing Countries

[REPORT] Social Dimensions of Climate Change: Equity and Vulnerability in a Warming World

[BLOG] A practical agenda for addressing climate-related conflict

[BLOG] Building resilient communities in West Africa in the face of climate-security risks

[REPORT] Meandering to Recovery

Stay Connected

Social Sustainability and Inclusion at the World Bank

This site uses cookies to optimize functionality and give you the best possible experience. If you continue to navigate this website beyond this page, cookies will be placed on your browser. To learn more about cookies, click here .

- VISIT Plan Your Visit Exhibits and Experiences Omnitheater Events Admission Parking & Directions Food & Drinks Accessibility & Amenities Private Events Safety

- EDUCATION Educator Resources Field Trips Learn from Home Lending Library Professional Development Summer Camps

- SCIENCE Our Science Collections Research Station Statement on Evolution Statement on Climate Change

- EQUITY Professional Development Youth STEM Justice Statement on Equity & Inclusion

- JOIN & GIVE Become A Member Give Corporate Support Legacy Giving Volunteer

The changing climate is a social justice issue

“Equity is at the heart of reversing climate change. Our collective challenge is to fundamentally change our behaviors, our habits, and our lifestyle to reduce carbon emissions, end the age of fossil fuels, and sustain a liveable planet for all.” — Joanne Jones-Rizzi, Vice President of Science, Equity, and Education Science Museum of Minnesota

I’ve learned while working at the Science Museum of Minnesota to view situations, ideas, and life through a variety of lenses. We work hard to bring together our core pillars of science, equity, and education, because it is when these three priorities come together that we do our best work. Science clearly tells us our planet is in trouble. We know the climate is changing and it is disproportionately affecting low-income countries and poor people in high-income countries. Climate change is a social justice issue, and we all need to understand this intersectionality (the overlap between the social impacts and environmental science of climate change). To make a real difference, consider how to take action to improve the current climate crisis through multiple lenses.

“It is the poor that actually suffer the most when there's an environmental injustice … and it's the poor that stand to benefit the most from an energy revolution.” — Kumi Naidoo of Africans Rising for Justice, Peace, and Dignity

I saw environmental injustice with my own eyes during a tour in New Orleans, LA. The tour was led by Leon Waters, founder of the Louisiana Museum of African American History and organizer of Hidden Histories tours; Anne Rolfes, founding director of the Louisiana Bucket Brigade—a citizen science organization; and Monique Verdin, tribal council person for the United Houma Nation. During this tour I witnessed the impact of industry on the environment and culture of New Orleans, as well as the historical transitions from plantations to refineries along the “Cancer Alley” corridor in the River Parishes. Even on a rainy morning, standing in neighborhoods in the shadows of refineries and other industries, all of my senses understood the impact industry and the changing climate has on life in these communities.

You don’t have to go to the other end of the Mississippi to witness the changing climate. Minnesota is warming slowly but surely. In the past 130 years, our state warmed by 2.9º F, while averaging 3.4 inches of additional annual rainfall. And although an extra 2.9 degrees may sound minor (and even welcome to Minnesotans at times!), its negative impact is significant. Minnesotans are already paying the price—literally—with homeowner’s insurance rates surging 68% in the past ten years due to a deluge of natural disasters in our state. But these impacts don’t affect everyone equally. People with less resources, from both urban and rural communities, suffer the most. Think about the farmers whose fields are underwater due to the more frequent and intense rainfall, and the urban poor who are exposed to much more pollution due to where they live day-after-day and generation-after-generation.

Nearly six in ten (58%) Americans are now either “Alarmed” or “Concerned” about global warming. From 2014 to 2019, the proportion of “Alarmed” nearly tripled. We should all be alarmed or concerned—whether we are directly affected or not. The problems are real, they’re here now, and they’re in desperate need of scientific solutions. To find those solutions, we must focus all of our intellectual firepower. But systems of social inequity mean that we’re shorting ourselves; we’re subjecting ourselves to a limited perspective and therefore a limited solution. We’re not harnessing all of our collective knowledge and creativity, and that needs to change.

There is still much we can do to stand up for science, together. ALL of us. We know that science, equity, and education can lead the way. This intersection is our superpower and the time to act is now. Be part of the solution and make a difference.

Do you want to learn more about climate change as a social justice issue? On this 50th anniversary of Earth Day, check out these resources and be inspired to take action:

Get involved with MN350 uniting Minnesotans as part of a global movement to end the pollution damaging our climate, speed the transition to clean energy, and create a just and healthy future for all.

Take action with COPAL to fight for environmental issues with racial and economic disparities in mind.

Stand up with the International Indigenous Youth Council and see how you can support the Twin Cities chapter.

Understand how climate change is already displacing thousands of people right now through this interactive article about climate migration.

Hear this interview with Thiagarajan Jayaramana , a professor at the School of Habitat Studies at the Tata Institute of Social Sciences, Mumbai, India, who has focused on climate action and climate justice for more than a decade.

Learn about the work of the Climate Justice Alliance —they envision a world in which fairness, equity, and ecological rootedness are core values.

Science is Action

It's time for bold climate action backed by science!

Connect with us

Interactive activities. Behind-the-scenes. Groundbreaking research. And even a few memes. That’s what you’ll find on our social media every day and in our emails once every two weeks.

Climate change: why is there still a gap between public opinion and scientific consensus, and how can we close it?

Catedrático de Ingeniería Química, Universitat de Girona

Director del IE Centre for Water & Climate Adaptation, IE University

Disclosure statement

The authors do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

IE University provides funding as a founding partner of The Conversation ES.

IE University provides funding as a member of The Conversation EUROPE.

Universitat de Girona provides funding as a member of The Conversation ES.

View all partners

As children, many of us played the “telephone” game – a message is whispered from one person to the next, invariably getting distorted as it passes along the line. In this game, people’s perception and understanding matters more than the original message, but as the US Secretary of Defence James Schlesinger said in 1975, “everyone is entitled to his own opinions, but not to his own facts”.

Today, this statement applies to climate change. While there is broad scientific consensus that human action has contributed decisively to warming the atmosphere, ocean and land, causing widespread change in a very short time, public opinion is less clear. At least 97% of scientists agree that humanity contributes to climate change, but the same cannot be said for society at large.

Same facts, different perceptions

Various studies and surveys show that social consensus on climate change is stronger in Europe than in the United States, where only 12% of citizens are aware of the scientific community’s near-total unanimity. This is a result of, among other things, disinformation , media portrayals , and cognitive bias .

Presenting climate change as a legitimate debate undermines the value of scientific consensus, often validating climate denialism – or its more recent iteration, delayism .

Moreover, there is a tendency to present ideological interpretations of the evidence as mere scientific disagreement: 82% of US Democratic voters believe that human activity contributes significantly to climate change, compared to just 38% of Republicans . This division also extends to responses to the crisis.

No enforcement, no accountability

The international community’s overall response has not been slow. As governments and multilateral bodies have become more aware of the issue they have committed themselves, albeit unevenly, to mitigation and adaptation plans.

This has also happened with decarbonisation plans , though, for the most part, commitments to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, like those laid out in the 2015 Paris Agreement , are not binding.

This illustrates a clear obstacle to change: these commitments include no legal obligations , no effective enforcement mechanisms, and no accountability measures. This undermines any agreements, and their uneven and inconsistent implementation allows some countries to be “free-riders” , reaping the benefits of reduced emissions while contributing little to the costs.

Transition plans in companies and countries, and even in the global energy sector , consist of detailed strategies towards carbon neutrality and the goal of net zero. These cover a range of measures, from technological innovation to regulatory instruments, investments, and changes in individual and collective behaviour . However, confusion surrounding objectives like carbon neutrality and net zero is also a deterrent in many cases.

There has been some progress since the Paris Agreement in 2015, which projected emissions in 2030 under then current policies to increase by 16%. Today, a 3% increase is projected in the same period, but emissions would still have to fall by 28% to stay within 2°C of global warming, and by 42% to stay under 1.5°C.

Carbon dioxide emissions from China’s energy sector, for instance, increased by 5.2% in 2023. This means that an unprecedented 4-6% reduction in 2025 would be needed to meet the target.

Why can’t we slow down emissions?

There is no simple or singular explanation for humanity’s inconsistent attitudes towards climate change. It is an immensely complex issue, and only by recognising its complexity can we understand and try to change behaviours.

Despite slowing annual growth, global demand for fossil fuels has not peaked . It is expected to do so by 2030, but only if electric vehicle uptake increases, and if China’s economy grows slowly and it deepens investments in renewable energy.

Substantial amounts are still being poured into oil and gas investments . Between 2016 and 2023, they reached an annual average of around $0.75 trillion.

In 2023, global investment in clean energy reached an estimated $1.8 trillion, although concentrated in a few countries: mainly China, the European Union and the USA. For every dollar invested in hydrocarbons , approximately 1.8 dollars are already going into clean energy, but not all of it into renewables.

It should also be noted that long term “ rebound effects ” can often offset successful reductions in use of certain raw materials such as coal.

Furthermore, the benefits of carbon emission reductions are global and long-term, while the associated costs are often local and immediate .

Meanwhile, in low-income and emerging countries a lot of development is still less environmentally friendly – such as India’s ongoing dependence on coal – despite evidence that the co-benefits of reducing carbon emissions outweigh the cost of mitigation in a number of sectors .

Solutions remain elusive

It seems clear that there is no single solution . Some possible solutions require infrastructure or technologies to manage resources more efficiently, but more and more involve changes to our lifestyles and values.

In classical economics , the idea of rationality assumes that, with adequate information and income, an individual will always choose that which maximises their wellbeing. However, this explanation falls short – it assumes that people only live to maximise satisfaction through consumption, and ignores dreams, expectations and goals that may include other human beings.

The work of Herbert Simon in the 1950s demonstrates that our decisions are more accurately explained by what is known as bounded rationality : our cognitive capacity, information and time are limited, so we simplify reality and adapt.

For his part, Zygmunt Bauman ’s conception of “ liquid modernity ” envisaged the transition from a solid modernity to a more fluid, unstable form, unable to maintain one set of behaviours for long, and much more prone to change.

In the same vein, Gilles Lipovetsky speaks about the individualism and hedonism of a culture that prioritises the immediate fulfilment of individual desires, as opposed to commitment and sacrifice in service of ethical principles.

How do we reconcile these ideas that explain the way we respond to imperatives of sacrifice that, implicitly or explicitly, appear in the narratives of climate action and just transition ?

Perhaps recognising complexity and trying to understand how we decide is part of the answer. Biases and inconsistencies are easier to detect in others than in oneself.

This article was originally published in Spanish

- Climate change

- Carbon emissions

- Public opinion

- The Conversation Europe

- climate denialism

Newsletter and Deputy Social Media Producer

Clinical Trials Project Manager

College Director and Principal | Curtin College

Head of School: Engineering, Computer and Mathematical Sciences

Educational Designer

News from the Columbia Climate School

Why Climate Change is an Environmental Justice Issue

September 21-27 is Climate Week in New York City. Join us for a series of online events and blog posts covering the climate crisis and pointing us towards action.

While COVID-19 has killed 200,000 Americans so far, communities of color have borne disproportionately greater impacts of the pandemic. Black, Indigenous and LatinX Americans are at least three times more likely to die of COVID than whites. In 23 states, there were 3.5 times more cases among American Indian and Alaskan Native communities than in white communities. Many of the reasons these communities of color are falling victim to the pandemic are the same reasons why they are hardest hit by the impacts of climate change.

How communities of color are affected by climate change

Climate change is a threat to everyone’s physical health, mental health, air, water, food and shelter, but some groups—socially and economically disadvantaged ones—face the greatest risks. This is because of where they live, their health, income, language barriers, and limited access to resources. In the U.S., these more vulnerable communities are largely the communities of color, immigrants, low-income communities and people for whom English is not their native language. As time goes on, they will suffer the worst impacts of climate change, unless we recognize that fighting climate change and environmental justice are inextricably linked.

The U.S. is facing warming temperatures and more intense and frequent heat waves as the climate changes. Higher temperatures lead to more deaths and illness, hospital and emergency room visits, and birth defects. Extreme heat can cause heat cramps, heat stroke, heat exhaustion, hyperthermia, and dehydration.

Disadvantaged communities have higher rates of health conditions such as heart disease, diabetes, asthma, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Heat stress can exacerbate heart disease and diabetes, and warming temperatures result in more pollen and smog, which can worsen asthma and COPD. Heat waves also affect birth outcomes. A study of the impact of California heat waves from 1999 to 2011 on infants found that mortality rates were highest for Black infants. Moreover, disadvantaged communities often lack access to good medical care and health insurance.

African Americans are three times more likely than whites to live in old, crowded or inferior housing; residents of homes with poor insulation and no air conditioning are particularly susceptible to the effects of increased heat. In addition, low-income areas in cities have been found to be five to 12 degrees hotter than higher income neighborhoods because they have fewer trees and parks, and more asphalt that retains heat.

Extreme weather events

While climate change cannot be definitively linked to any particular extreme weather event, incidents of heat waves, droughts, wildfires, heavy downpours, winter storms, floods and hurricanes have increased and climate change is expected to make them more frequent and intense.

Extreme weather events can cause injury, illness, and death. Changes in precipitation patterns and warming water temperatures enable bacteria, viruses, parasites and toxic algae to flourish; heavy rains and flooding can pollute drinking water and increase water contamination, potentially causing gastrointestinal illnesses like diarrhea and damaging livers and kidneys.

Extreme weather events also disrupt electrical power, water systems and transportation, as well as the communication networks needed to access emergency services and health care. Disadvantaged communities are particularly at risk because subpar housing with old infrastructure may be more vulnerable to power outages, water issues and damage. Residents of these communities may lack adequate health care, medicines, health insurance, and access to public health warnings in a language they can understand. In addition, they may not have access to transportation to escape the impacts of extreme weather, or home insurance and other resources to relocate or rebuild after a disaster. Communities of color are also less likely to receive adequate protection against disasters or a prompt response in case of emergencies. In addition to physical hardships, the stress and anxiety of dealing with these impacts of extreme weather can end up exacerbating mental health problems such as depression, post-traumatic stress and suicide.

Poor air quality

While climate change does not cause poor air quality , burning fossil fuels does; and climate change can worsen air quality. Heat waves cause air masses to remain stagnant and prevent air pollution from moving away. Warmer temperatures lead to the creation of more smog, particularly during summer. And wildfires, fueled by heat waves and drought, produce smoke that contains toxic pollutants.

Living with polluted air can lead to heart and lung diseases, aggravate allergies and asthma and cause premature death. People who live in urban areas with air pollution, or who have medical conditions such as hypertension, diabetes, asthma or COPD, are particularly vulnerable to the impacts of air pollution.

Black people are three times more likely to die from air pollution than white people. This is in part because they are 70 percent more likely to live in counties that are in violation of federal air pollution standards. A University of Minnesota study found that, on average, people of color are exposed to 38 percent higher levels of nitrogen dioxide outdoor air pollution than white people. One reason for the high COVID-19 death rate among African Americans is that cumulative exposure to air pollution leads to a significant increase in the COVID death rate, according to a new peer-reviewed study.

More people of color live in places that are polluted with toxic waste, which can lead to illnesses such as cancer, heart disease, high blood pressure and asthma. These pre-existing conditions put people at higher risk for the more severe effects of COVID-19.

The fact that disadvantaged communities are in some of the most polluted environments in the U.S. is no coincidence. Communities of color are often chosen as sites for landfills, chemical plants, bus terminals and other dirty businesses because corporations know it’s harder for these residents to object. They usually lack the connections to lawmakers who could protect them and can’t afford to hire technical or legal help to put up a fight. They may not understand how they will be impacted, perhaps because the information is not in their native language. A 1987 report showed that race was the single most important factor in determining where to locate a toxic waste facility in the U.S. It found that “Communities with the greatest number of commercial hazardous waste facilities had the highest composition of racial and ethnic residents.”

For example, while Blacks make up only 13 percent of the U.S. population, 68 percent live within 30 miles of a coal plant. LatinX people are 17 percent of the population, but 39 percent of them live near coal plants. A new report found that about 2,000 official and potential highly contaminated Superfund sites are at risk of flooding due to sea level rise; the areas around these sites are mainly communities of color and low-income communities.

The link between climate change and environmental justice

Mary Annaïse Heglar , a climate justice essayist and former writer-in-residence at the Earth Institute, asserts that climate change is actually the product of racism. “It started with conquest, genocides, slavery, and colonialism,” she wrote . “That is the moment when White men’s relationship with living things became extractive and disharmonious. Everything was for the taking; everything was for sale. The fossil fuel industry was literally built on the backs and over the graves of Indigenous people around the globe, as they were forced off their land and either slaughtered or subjugated — from the Arab world to Africa, from Asia to the Americas. Again, it was no accident.”

The harmful impacts of climate change are linked to historical neglect and racism. When Black people migrated North from the South in the early 20th century, many did not have jobs or money; consequently they were forced to live in substandard housing. Jim Crow laws in the South reinforced racial segregation, prohibiting Blacks from moving into white neighborhoods. In the 1930s through the 1960s, the federal government’s “redlining” policy denied federally backed mortgages and credit to minority neighborhoods. As a result, African Americans had limited access to better homes and all the advantages that went with them—a healthy environment, better schools and healthcare, and more food options.

Prime examples of environmental injustice

Poor sanitation in the U.S.

Catherine Flowers, founder of the Center for Rural Enterprise and Environmental Justice and a senior fellow for the Center for Earth Ethics , which is affiliated with the Earth Institute, is from Lowndes County, Alabama. As a child growing up in a poor, mostly Black rural area with less than 10,000 residents, she used an outhouse before her family installed indoor plumbing. After leaving to get an education, Flowers returned to Alabama in 2002 and still saw extreme disparities in rural wastewater treatment. She visited many homes with sewage backing up into their homes or pooling in their yards, as many residents couldn’t afford onsite wastewater treatment. She is still advocating for proper sanitation in Lowndes. As a result of her work, Baylor College’s National School of Tropical Medicine conducted a peer-reviewed study which showed that over 30 percent of Lowndes County residents had hookworm and other tropical parasites due to poor sanitation.

”We’re also seeing that there is a relationship between [wastewater and] COVID infections,” added Flowers. “We don’t know exactly what it is yet—but you can actually measure wastewater to determine the level of infections in the community before people start showing up with the illness.” In Lowndes, one of every 18 residents has COVID-19; it is one of the highest infection rates in the U.S.

Today, Flowers works at the intersection between climate change and wastewater throughout the U.S. “The more we see sea level rise, the more we’re going to have wastewater problems,” she said. Her new book, Waste, One Woman’s Fight Against America’s Dirty Secret , due out in November, shows how proper sanitation is essential as climate change will likely bring sewage to more backyards everywhere, not just in poor communities.

Cancer Alley

An 85-mile stretch along the Mississippi River between Baton Rouge and New Orleans, Louisiana, hosts the densest concentration of petrochemical companies in the U.S. There have been so many cases of cancer and death in the area that it became known as “Cancer Alley.”

Most of these petrochemical plants are situated near towns that are largely poor and Black. There are 30 large plants within 10 miles of mostly Black St. Gabriel, with 13 within three miles. St. James Parish, whose population is roughly half Black and half white, has over 30 petrochemical plants, but the majority are located in the district that is 80 percent Black.

These plants not only emit greenhouse gases that are exacerbating climate change, but the particulate matter they expel can contain hundreds of different chemicals. Chronic exposure to this air pollution can lead to heart and respiratory illnesses and diabetes. As such, it is no surprise that St. James Parish is among the 20 U.S. counties with the highest per-capita death rates from COVID-19.

Despite efforts of the residents to fight back, seven new petrochemical plants have been approved since 2015; five more are awaiting approval.

Hurricane Katrina

In 2005, Hurricane Katrina, a Category 3 storm, caused extensive destruction in New Orleans and its environs. More than half of the 1,200 people who died were Black and 80 percent of the homes that were destroyed belonged to Black residents. The mostly Black neighborhoods of New Orleans East and the Lower Ninth Ward were hit hardest by Katrina because while the levees in white areas had been shored up after earlier hurricanes, these poorer neighborhoods had received less government funding for flood protection. After the hurricane, when initial plans for rebuilding were in process, white neighborhoods again got priority, even if they had experienced less flooding. Eventually federal funds were directed toward the rebuilding of parts of the Lower Ninth Ward and New Orleans East and the strengthening of their levees.

In 2014, the city of Flint, MI, whose population is 56.6 percent Black, decided to draw its drinking water from the polluted Flint River in order to save money until a new pipeline from Lake Huron could be built. Previously the city had brought in treated drinking water from Detroit. Because the river had been used by industry as an illegal waste dump for many years, the water was corrosive, but officials failed to treat it. As a result, the water leached lead from the city’s aging pipelines. Officials claimed the water was safe, but more than 40 percent of the homes had elevated lead levels. As almost 100,000 residents — including 9,000 children — drank lead-laced water, lead levels in the children’s blood doubled and tripled in some neighborhoods, putting them at high risk for neurological damage.

In October, 2015, the city began importing water from Detroit again. An ongoing project to replace lead service pipes is expected to be complete by the end of November. And just recently, Flint victims were awarded a settlement of $600 million, with 80 percent of it designated for the affected children.

Steps to achieve environmental justice

As the founder of the Center for Rural Enterprise and Environmental Justice, Catherine Flowers works to implement the best practices to reduce environmental injustice. Here are some key strategies she prescribes.

- Acknowledge the damage and try to repair it.

- Clean up sites where environmental damage has been done.

- Create an equitable system for decision-making so there is not an undue burden placed on disadvantaged communities. “Lobbyists that represent these [polluting] companies shouldn’t have more influence than the people who live in the area that are impacted by it,” said Flowers. “We need to make sure that the people that live in the community are sitting at the table when decisions are being made about what’s located in their community.”

- Call out the officials who are making decisions that are not in the best interest of the people they represent.

- Vote to put in place representatives that listen to their constituents rather than the people and companies that donate to them.

- Provide climate training to help people become more engaged. For example, the Climate Reality Project (Flowers sits on its board of directors) trains everyday people to fight for solutions and change in their communities.

- Partner with universities to conduct peer-reviewed studies of health impacts to help validate and draw attention to the experiences of disadvantaged communities.

- Build cleaner and greener. “We cannot discount the impact this could have on communities around the world,” said Flowers. “If we don’t pollute and we have a Green New Deal to build better, cleaner, and greener, then we won’t have these environmental justice issues.”

Related Posts

Venetian Ventures: Exploring Sustainable Development Through Fellowships in Italy

Ancient Plant, Insect Bits Confirm Greenland Melted in Recent Geologic Past

Planting Some Tree Species May Worsen, Not Improve, NYC Air, Says New Study

Injustice of any kind? It really does not matter. Unless people change their idea of materialism madness and understand the fact that they are threatened, we will get nowhere. When was the last time humans have done much of anything out of compassion if it would alter their own lifestyles?

I wonder if governments (particularly of modernized nations like America, the UK and China) have purposely chosen to ignore the issue of climate change? I agree that most of it falls on things like industrial shipping, transportation and processing, but governemnt incentivization is another issue with climate justice as a whole.

Simple VersionCOVID-19 has tragically claimed the lives of 200,000 Americans. However, it has disproportionately affected communities of color. Black, Indigenous, and LatinX Americans are at least three times more likely to die from COVID than their white counterparts. In 23 states, American Indian and Alaskan Native communities reported 3.5 times more cases compared to white communities. These same communities are also the most vulnerable to the impacts of climate change. Factors such as location, health, income, language barriers, and limited resources contribute to their heightened susceptibility. These marginalized groups include communities of color, immigrants, low-income populations, and non-native English speakers. If not addressed, these groups will suffer the harshest consequences of climate change. It is crucial to acknowledge that addressing environmental justice and combating climate change go hand in hand. The rising temperatures and increased intensity of natural disasters in the U.S. are indicative of this pressing issue.

Hello Renée Cho, I agree with your position on climate change; the events that occur heavily affect the health of the economy; Your connection with how COVID-19 still affects people with the rise of climate change events. We’ve been seeing records of air pollution continuing to showcase dramatic numbers. With the long-term symptoms of COVID-19 being asthma and heart complications, air pollution can worsen those problems and make survivors of COVID-19 vulnerable. Your connection with these ex-patients explains how aggressive climate change can change someone’s life around so negatively. Also, we’ve seen aggressive heat waves hitting across the globe sending people of all ages into hospitals. If adults and children are barely handling such temperatures, imagine how infants are the most susceptible to suffering from these heat waves as their bodies are not meant to withstand such heat. These heat waves are affecting ex-COVID-19 individuals with asthma as the thick air makes it difficult to breathe. We cannot afford such catastrophes caused by these damages.

6/12/24, 2:48 pm

Get the Columbia Climate School Newsletter

New Student Welcome and Orientation : August 21, 2024

Understanding Climate Change as a Social Issue: How Research Can Help

- Grand Challenges

Earth’s increasingly deadly and destructive climate is prompting social work leaders to focus the profession’s attention on one of humanity’s most pressing issues: environmental change.

Typhoons are hitting the South Pacific with greater severity and regularity. Hurricane Katrina prompted the largest forced migration of Americans since the Civil War. Civil conflicts and instability in the Middle East and Africa are being linked to climate change and its socioecological effects.

“We see it perhaps most importantly as a social justice issue,” said Lawrence Palinkas , the Albert G. and Frances Lomas Feldman Professor of Social Policy and Health at the USC Suzanne Dworak-Peck School of Social Work. “Generally the people most affected by climate change tend to be the poor, older adults, children and families, and people with a history of mental health problems — populations that are typically the focus of social work practice.”

This inherent link between social work and the social and economic consequences of environmental change is at the heart of a new initiative Palinkas and other social work scholars are leading as part of the Grand Challenges for Social Work.

Organized by the American Academy of Social Work and Social Welfare, the national effort seeks to achieve societal progress by identifying specific challenges that social work can play a central role in overcoming — in this case, creating social responses to the changing environment.

“Where we see social workers playing a role is developing an evidence-based approach to disaster preparedness and response,” Palinkas said. “How do we provide services to communities that are devastated by natural disasters? How do we help populations that are being dislocated by virtue of changes in the environment?”

Inaction could prove deadly

Not addressing this issue is likely to have dire consequences. At a policy meeting in London in December, military experts warned that dramatic shifts in the natural and built environments could trigger a major global disaster in the near future.

“Climate change could lead to a humanitarian crisis of epic proportions,” retired Brig. Gen. Stephen A. Cheney, CEO of the American Security Project and a member of the U.S. Department of State’s Foreign Affairs Policy Board, said in prepared remarks. “We’re already seeing migration of large numbers of people around the world because of food scarcity, water insecurity and extreme weather, and this is set to become the new normal.”

To describe their vision for social work’s role in this grand challenge, Palinkas and his partners outlined three main policy recommendations for the profession.

The first recommendation centers on reducing the impact of disasters such as extreme weather events. Climate-related catastrophes affect more than 375 million people every year—an increase of 50 percent compared to the previous decade.

Palinkas emphasized the need to develop and spread evidence-based interventions to combat that risk and respond in the wake of disasters, in part by ensuring that all clinicians and social work students receive training in disaster preparedness and response as a critical component of the job.

“That includes things like training communities in the use of evidence-based practices to provide treatment for traumatic symptoms in the aftermath of a disaster,” he said. “We also need to promote social cohesion and community resilience to mitigate the possibility of social conflict.”

Leaders from the USC Suzanne Dworak-Peck School of Social Work are ahead of the curve in tackling that piece of the puzzle, most notably in the Pacific Rim. In recent years, for example, a team of researchers and practitioners from the school has led humanitarian missions to the Philippines following major typhoons.

Building a safety net

Faculty members Marleen Wong and Vivien Villaverde are among those who have traveled to the South Pacific to offer training sessions on delivering psychological first aid, addressing secondary post-traumatic stress and promoting social development.

“In many parts of Asia, the infrastructure for disaster response and recovery is weak,” said Villaverde, a clinical associate professor with expertise in disaster preparedness, crisis interventions and trauma-informed care. “At the same time, that’s where a lot of climate-related natural disasters are occurring.”

Social workers can assist during recovery efforts by offering interventions and training others to use them, she said, but broader efforts to prepare for and respond to crises are needed.

Although the USC team has generally focused on the intervention component, Villaverde noted an increasing emphasis on the multi-tier framework described by Palinkas and other scholars in the Grand Challenge policy brief, which calls on governments and private organizations to begin planning for climate change and related disasters at a national and community level.

Wong echoed the need for countries like the Philippines to move beyond merely reacting to environmental disasters, particularly in terms of developing proactive plans that outline how various government agencies, community groups and individuals can prepare for and respond to catastrophes.

“Social work has a clear role to play in building that safety net,” said Wong, senior associate dean of field education and clinical professor. “We can bring our knowledge and skills and develop additional ways of supporting people, especially children and families, in the wake of these natural disasters.”

Invisible refugees

Another critical issue highlighted by the Grand Challenge team is the emergence of a new class of displaced individuals, known as environmental or ecological refugees.

Environmental factors have caused an estimated 25 million people to relocate, according to the policy brief, and that figure is expected to skyrocket to 250 million by 2050. Examples include rising sea levels that are forcing Pacific Islanders to seek asylum in New Zealand, the devastating flooding of the Lower Ninth Ward in New Orleans that displaced thousands and the recent conclusion of the United Nations Security Council that climate change prompted the war in Sudan.

“Of course people want to leave North Korea due to the harsh political environment, but the reality is most are leaving because the agricultural system was destroyed by devastating floods beginning in the 1990s,” Palinkas said. “Even this year, what little had been rebuilt was again wiped out by a series of historic floods.”

A major problem is these individuals have no legal status under the United Nations mandate to protect and support refugees, he said. Because they are denied protections offered to people fleeing from war or conflict, they may not have access to care or shelter, are unable to plan for the future and are afforded little dignity.

“They might not be leaving because their lives are being threatened, but threats to their livelihood are forcing them to migrate,” Palinkas said. “People who may not have had difficulties in generating income through agricultural activities are suddenly being forced to relocate because they can’t grow crops anymore.”

In addition to raising awareness and advocating for policy changes to ensure these individuals are supported, he said strategies are needed for long-term relocation of these environmental migrants.

An urban future

Finally, the Grand Challenge authors are calling for increased focus on the effects of urbanization and the inclusion of marginalized communities in planning for inevitable environmental changes. Experts expect two-thirds of the world’s population will be living in cities by 2050, which means increasing demands on infrastructure and service systems, new threats to security and increased density.

“How do we accommodate more people in the same amount of space?” Palinkas said. “How can we provide adequate support systems — not just physical but governmental, service-related, health care-related — to people living in these urban areas?”

Policies need to be developed that ensure equitable use of space, provide housing to all, protect the natural environment and create access to services and jobs. A critical component of developing those guidelines is giving a voice to vulnerable communities that have been left out of previous planning efforts.

Doing so will ensure that marginalized groups, particularly low-income individuals and people with racial and ethnic minority backgrounds, will not be disproportionately harmed by changes in urban and regional environments.

One effort to give voice to individuals interested in tackling climate change at the grassroots level is CYPHER , a technology-focused initiative led by R. Bong Vergara , an adjunct assistant professor at the USC Suzanne Dworak-Peck School of Social Work.

In collaboration with Los Angeles CleanTech Incubator and other local partners, the program encourages teens and young adults from the United States, China and Kenya to develop social and technological strategies to address the human impact of climate change — ideas they present at CYPHER’s signature event, the Sustainable Earth Decathlon, each spring.

“Our work creates a pipeline of clean technology and tech-enabled solutions to local manifestations of climate change,” Vergara said. “Although we are interested in solutions, we are profoundly compelled by our target outcome, which is a shift in identity among these youth from non-innovators to tech innovators.”

He described one participant, the son of undocumented farmworkers, who had to ask his parents for permission to go to school and take part in CYPHER, which took him away from assisting with farm labor.

That personal background proved invaluable, Vergara said; the student helped invent an app-enabled irrigation system that shows farmworkers and landowners which parcel of property needs water the most. It earned top honors at the annual competition.

“The insight from his direct, personal experience of the impact of a heat wave on their farm was really instrumental in making the innovation that his team came up with rise to the very top,” Vergara said. “He saw the impact, financially, emotionally and socially, of solving the overlap of food, energy and water systems in the fields of his community.”

Measuring success

Many of the goals of the Grand Challenge team are broad and seemingly nebulous, so developing metrics that highlight progress could prove difficult. However, Palinkas said markers such as reducing the prevalence of environmentally induced diseases by a certain percentage might serve as signals of success.

“We may not reduce the number of natural disasters, but we may reduce the number of displaced families,” he said. “We may reduce the incidence of psychiatric conditions like PTSD or generalized anxiety disorder that are often associated with exposure to these kinds of events.”

In general, many are encouraged the Grand Challenge and the overall concept of responding to environmental change from a social perspective is gaining awareness among social workers and others in the helping professions.

Palinkas, Wong and other leading scholars have been crossing the globe to highlight the Grand Challenge initiative, delivering speeches in places like South Korea, Portugal, China, Singapore, Papua New Guinea, Philippines, Taiwan and Switzerland.

“I think social work is really well positioned to address this challenge,” Wong said. “Social workers never work alone; they always work as a team. In these complex situations, we need to build teams to enhance the national capacity to respond.”

To reference the work of our faculty online, we ask that you directly quote their work where possible and attribute it to "FACULTY NAME, a professor in the USC Suzanne Dworak-Peck School of Social Work” (LINK: https://dworakpeck.usc.edu)

45,000+ students realised their study abroad dream with us. Take the first step today

Meet top uk universities from the comfort of your home, here’s your new year gift, one app for all your, study abroad needs, start your journey, track your progress, grow with the community and so much more.

Verification Code

An OTP has been sent to your registered mobile no. Please verify

Thanks for your comment !

Our team will review it before it's shown to our readers.

- School Education /

Essay on Climate Change: Check Samples in 100, 250 Words

- Updated on

- Sep 21, 2023

Writing an essay on climate change is crucial to raise awareness and advocate for action. The world is facing environmental challenges, so in a situation like this such essay topics can serve as s platform to discuss the causes, effects, and solutions to this pressing issue. They offer an opportunity to engage readers in understanding the urgency of mitigating climate change for the sake of our planet’s future.

Must Read: Essay On Environment

Table of Contents

- 1 What Is Climate Change?

- 2 What are the Causes of Climate Change?

- 3 What are the effects of Climate Change?

- 4 How to fight climate change?

- 5 Essay On Climate Change in 100 Words

- 6 Climate Change Sample Essay 250 Words

What Is Climate Change?

Climate change is the significant variation of average weather conditions becoming, for example, warmer, wetter, or drier—over several decades or longer. It may be natural or anthropogenic. However, in recent times, it’s been in the top headlines due to escalations caused by human interference.

What are the Causes of Climate Change?

Obama at the First Session of COP21 rightly quoted “We are the first generation to feel the impact of climate change, and the last generation that can do something about it.”.Identifying the causes of climate change is the first step to take in our fight against climate change. Below stated are some of the causes of climate change:

- Greenhouse Gas Emissions: Mainly from burning fossil fuels (coal, oil, and natural gas) for energy and transportation.

- Deforestation: The cutting down of trees reduces the planet’s capacity to absorb carbon dioxide.

- Industrial Processes: Certain manufacturing activities release potent greenhouse gases.

- Agriculture: Livestock and rice cultivation emit methane, a potent greenhouse gas.

What are the effects of Climate Change?

Climate change poses a huge risk to almost all life forms on Earth. The effects of climate change are listed below:

- Global Warming: Increased temperatures due to trapped heat from greenhouse gases.

- Melting Ice and Rising Sea Levels: Ice caps and glaciers melt, causing oceans to rise.

- Extreme Weather Events: More frequent and severe hurricanes, droughts, and wildfires.

- Ocean Acidification: Oceans absorb excess CO2, leading to more acidic waters harming marine life.

- Disrupted Ecosystems: Shifting climate patterns disrupt habitats and threaten biodiversity.

- Food and Water Scarcity: Altered weather affects crop yields and strains water resources.

- Human Health Risks: Heat-related illnesses and the spread of diseases.

- Economic Impact: Damage to infrastructure and increased disaster-related costs.

- Migration and Conflict: Climate-induced displacement and resource competition.

How to fight climate change?

‘Climate change is a terrible problem, and it absolutely needs to be solved. It deserves to be a huge priority,’ says Bill Gates. The below points highlight key actions to combat climate change effectively.

- Energy Efficiency: Improve energy efficiency in all sectors.

- Protect Forests: Stop deforestation and promote reforestation.

- Sustainable Agriculture: Adopt eco-friendly farming practices.

- Advocacy: Raise awareness and advocate for climate-friendly policies.

- Innovation: Invest in green technologies and research.

- Government Policies: Enforce climate-friendly regulations and targets.

- Corporate Responsibility: Encourage sustainable business practices.

- Individual Action: Reduce personal carbon footprint and inspire others.

Essay On Climate Change in 100 Words

Climate change refers to long-term alterations in Earth’s climate patterns, primarily driven by human activities, such as burning fossil fuels and deforestation, which release greenhouse gases into the atmosphere. These gases trap heat, leading to global warming. The consequences of climate change are widespread and devastating. Rising temperatures cause polar ice caps to melt, contributing to sea level rise and threatening coastal communities. Extreme weather events, like hurricanes and wildfires, become more frequent and severe, endangering lives and livelihoods. Additionally, shifts in weather patterns can disrupt agriculture, leading to food shortages. To combat climate change, global cooperation, renewable energy adoption, and sustainable practices are crucial for a more sustainable future.

Must Read: Essay On Global Warming

Climate Change Sample Essay 250 Words

Climate change represents a pressing global challenge that demands immediate attention and concerted efforts. Human activities, primarily the burning of fossil fuels and deforestation, have significantly increased the concentration of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere. This results in a greenhouse effect, trapping heat and leading to a rise in global temperatures, commonly referred to as global warming.

The consequences of climate change are far-reaching and profound. Rising sea levels threaten coastal communities, displacing millions and endangering vital infrastructure. Extreme weather events, such as hurricanes, droughts, and wildfires, have become more frequent and severe, causing devastating economic and human losses. Disrupted ecosystems affect biodiversity and the availability of vital resources, from clean water to agricultural yields.

Moreover, climate change has serious implications for food and water security. Changing weather patterns disrupt traditional farming practices and strain freshwater resources, potentially leading to conflicts over access to essential commodities.

Addressing climate change necessitates a multifaceted approach. First, countries must reduce their greenhouse gas emissions through the transition to renewable energy sources, increased energy efficiency, and reforestation efforts. International cooperation is crucial to set emission reduction targets and hold nations accountable for meeting them.