Collaborative and Group Writing

Introduction

When it comes to collaborative writing, people often have diametrically opposed ideas. Academics in the sciences often write multi-authored articles that depend on sharing their expertise. Many thrive on the social interaction that collaborative writing enables. Composition scholars Lisa Ede and Andrea Lunsford enjoyed co-authoring so much that they devoted their career to studying it. For others, however, collaborative writing evokes the memories of group projects gone wrong and inequitable work distribution.

Whatever your prior opinions about collaborative writing, we’re here to tell you that this style of composition may benefit your writing process and may help you produce writing that is cogent and compelling. At its best, collaborative writing can help to slow down the writing process, since it necessitates conversation, planning with group members, and more deliberate revising. A study described in Helen Dale’s “The Influence of Coauthoring on the Writing Process” shows that less experienced writers behave more like experts when they engage in collaborative writing. Students working on collaborative writing projects have said that their collaborative writing process involved more brainstorming, discussion, and diverse opinions from group members. Some even said that collaborative writing entailed less of an individual time commitment than solo papers.

Although collaborative writing implies that every part of a collaborative writing project involves working cooperatively with co-author(s), in practice collaborative writing often includes individual work. In what follows, we’ll walk you through the collaborative writing process, which we’ve divided into three parts: planning, drafting, and revising. As you consider how you’ll structure the writing process for your particular project, think about the expertise and disposition of your co-author(s), your project’s due date, the amount of time that you can devote to the project, and any other relevant factors. For more information about the various types of co-authorship systems you might employ, see “Strategies for Effective Collaborative Manuscript Development in Interdisciplinary Science Teams,” which outlines five different “author-management systems.”

The Collaborative Writing Process

Planning includes everything that is done before writing. In collaborative writing, this is a particularly important step since it’s crucial that all members of a team agree about the basic elements of the project and the logistics that will govern the project’s completion.Collaborative writing—by its very definition—requires more communication than individual work since almost all co-authored projects oblige participants to come to an agreement about what should be written and how to do this writing. And careful communication at the planning stage is usually critical to the creation of a strong collaborative paper. We would recommend assigning team members roles. Ensure that you know who will be initially drafting each section, who will be revising and editing these sections, who will be responsible for confirming that all team members complete their jobs, and who will be submitting the finished project.

Drafting refers to the process of actually writing the paper. We’ve called this part of the process drafting instead of writing to highlight the recursive nature of crafting a compelling paper since strong writing projects are often the product of several rounds of drafts. At this point in the writing process, you’ll need to make a choice: will you write together, individually, or in some combination of these two modes?

Individually

Revising is the final stage in the writing process. It will occur after a draft (either of a particular section or the entire paper) has been written. Revising, for most writing projects, will need to go beyond making line-edits that revise at the sentence-level. Instead, you’ll want to thoroughly consider all aspects of the draft in order to create a version of it that satisfies each member of the team. For more information about revision, check out our Writer’s Handbook page about revising longer papers .Even if your team has drafted the paper individually, we would recommend coming together to discuss revisions. Revising together and making choices about how to improve the draft—either online or in-person— is a good way to build consensus among group members since you’ll all need to agree on the changes you make.After you’ve discussed the revisions as a group, you’ll need to how you want to complete these revisions. Just like in the drafting stage above, you can choose to write together or individually.

Person A writes a section Person B gives suggestions for revision on this section Person A edits the section based on these suggestions

Person A writes a section The entire team meets and gives suggestions for revision on this section Person B edits the section based on these suggestions

Think through the strengths of your co-authoring team and choose a system that will work for your needs.

Suggestions for Efficient and Harmonious Collaborative Writing

Establish ground rules.

Although it can be tempting to jump right into your project—especially when you have limited time—establishing ground rules right from the beginning will help your group navigate the writing process. Conflicts and issues will inevitably arise in during the course of many long-term project. Knowing how you’ll navigate issues before they appear will help to smooth out these wrinkles. For example, you may also want to establish who will be responsible for checking in with authors if they don’t seem to be completing tasks assigned to them by their due dates. You may also want to decide how you will adjudicate disagreements. Will the majority rule? Do you want to hold out for full consensus? Establishing some ground rules will ensure that expectations are clear and that all members of the team are involved in the decision-making process.

Respect your co-author(s)

Everyone has their strengths. If you can recognize this, you’ll be able to harness your co-author(s) assets to write the best paper possible. It can be easy to write someone off if they’re not initially pulling their weight, but this type of attitude can be cancerous to a positive group mindset. Instead, check in with your co-author(s) and figure out how each one can best contribute to the group’s effort.

Be willing to argue

Arguing (respectfully!) with the other members of your writing group is a good thing because it means that you are expressing your deeply held beliefs with your co-author(s). While you don’t need to fight your team members about every feeling you have (after all, group work has to involve compromise!), if there are ideas that you feel strongly about—communicate them and encourage other members of your group to do the same even if they conflict with others’ viewpoints.

Schedule synchronous meetings

While you may be tempted to figure out group work purely by email, there’s really no substitute for talking through ideas with your co-author(s) face-to-face—even if you’re looking at your teammates face through the computer. At the beginning of your project, get a few synchronous meetings on the books in advance of your deadlines so that you can make sure that you’re able to have clear lines of communication throughout the writing process.

Use word processing software that enables collaboration

Sending lots of Word document drafts back-and-forth over email can get tiring and chaotic. Instead, we would recommend using word processing software that allows online collaboration. Right now, we like Google Docs for this since it’s free, easy to use, allows many authors to edit the same document, and has robust collaboration tools like chat and commenting.

Dale, Helen. “The Influence of Coauthoring on the Writing Process.” Journal of Teaching Writing , vol. 15, no. 1, 1996, pp. 65-79.

Lunsford, Andrea A., and Lisa Ede. Writing Together: Collaboration in Theory and Practice . Bedford St. Martin, 2011.

Oliver, Samantha K., et al. “Strategies for Effective Collaborative Manuscript Development in Interdisciplinary Science Teams.” Ecosphere , vol. 9, no. 4, Apr. 2018, pp. 1–13., doi:10.1002/ecs2.2206.

Writing Process and Structure

This is an accordion element with a series of buttons that open and close related content panels.

Getting Started with Your Paper

Interpreting Writing Assignments from Your Courses

Generating Ideas for Your Paper

Creating an Argument

Thesis vs. Purpose Statements

Developing a Thesis Statement

Architecture of Arguments

Working with Sources

Quoting and Paraphrasing Sources

Using Literary Quotations

Citing Sources in Your Paper

Drafting Your Paper

Generating Ideas for Your Paper Introductions Paragraphing Developing Strategic Transitions Conclusions

Revising Your Paper

Peer Reviews

Reverse Outlines

Revising an Argumentative Paper

Revision Strategies for Longer Projects

Developing Strategic Transitions

Finishing your Paper

Twelve Common Errors: An Editing Checklist

How to Proofread your Paper

Writing Collaboratively

- Grammar Checker

- Paraphrasing Tool

- Critique Report

- Writing Reports

- Learn Blog Grammar Guide Community Events FAQ

- Grammar Guide

How to Master Collaborative Writing

By Jennifer Xue

If you think writing is a solitary effort, think again. Some types of writing, in fact, might have a better outcome when they're written collaboratively.

In this article, we'll discuss what collaborative writing is, the advantages, the project types that likely succeed when approached collaboratively, how to find and hire qualified co-writers, and what the must-have tools.

What is Collaborative Writing?

Advantages of collaborative writing, projects likely to be successful, finding and managing collaborators, must-have tools.

Both fiction and non-fiction works, including business and technical writing projects, can involve a team of several members or one or two co-authors. Academic writing, such as journal writing, has a long history of co-authoring. It is reflected in the long list of co-authors under each reference item on college students' bibliography pages.

Technical, business or marketing white papers usually involve one or two teams of subject matter experts and writers to ensure the highest quality of the deliverables. In business projects, such deliverables typically don't have any byline, which makes many readers aren't aware of their existence.

If you're a fan of best-selling author James Patterson, you probably notice that his novels often involve co-authors. Their names have smaller fonts on the front page, but they're appropriately cited. And there are many more established fiction and non-fiction authors who write with their collaborators, despite whether they're adequately attributed or not. Those who don't get a co-author byline are referred to as "ghostwriters."

Of course, to be successful in any collaboration, begin by choosing your writing partner wisely. Since writing is both a science and an art, sometimes people you're close with in real life may not be able to fulfill your expectations as good and equal writing partners.

Interestingly, if you think that having the right skills is the most important, those who write well may or may not perform their collaborating duties. This said, you and your partner must have similar, if not identical, vision for the substance of the book and work around the schedule to fit in the project.

Ideally, the tone of voice and style must be comparable, and the skills are compatible and complement each other. If the latter isn't possible, a copyeditor would be needed to ensure that the parts of the project are synchronous and in harmony with each other.

Your strong suits complement your partner's. For instance, if you're good at research, but your partner is good at analyses, you must work together, so no overlap occurs. But both of you have a similar level of understanding on the subject.

Personalitywise, both of you need to get along well. It's preferred that you can be close on a personal level and share some activities. However, if it's not possible, at least be respectful and honorable on a professional level. It's recommended not to talk about sensitive issues, like politics, religion, and personal matters.

Two heads are better than one. With the power of two minds, especially two influential, well-educated, and well-published writers, you can expect to solve many problems, including combining interdisciplinary thinking to deepen the understanding of various issues and people. This would allow a new level of excellence to emerge and provide an avenue for synthesizing and analyzing ideas.

For fiction writers, such synergy would combine both intellectual and affectional aspects. For instance, one author may have experienced a specific incident in life. Thus they already have a deeper understanding. Such emotional power would be useful in depicting the spirit of the work. With it, the other author would be able to absorb the environment, thus have their passages reflect such profound insights as well.

For non-fiction authors, a collaborative work style has been known for decades. For instance, it's common for journal articles to be written by multiple authors, which can be within one discipline or from multiple disciplines.

As science continues to progress, every researcher (or writer) needs their peers' collaboration to keep their knowledge in check. With a co-author, there is a sense of healthy competition.

There is no fixed formula on how to work on collaborative writing projects. Everything depends on your and your partner's efforts and commitment. A stable external environment is another determining factor, as background noise would affect a writer's focus.

Having a clear vision on the premise or a thesis statement of the non-fiction project is one thing. Managing the project when it's being executed, such as choosing the right style, tone, and structure is another. And maintaining positive morale is the glue that sticks things together.

Next, both (or all) authors must have clarity on their sections (or chapters or parts) of the project and how they must approach them while simultaneously and seamlessly complementing their partners. For instance, in a non-fiction book, every chapter has clear objectives and answers to specific questions that serve as the overarching framework.

As a team, you and co-authors must be realistic on their work schedules and project milestones, as most likely, every partner has their full-time jobs and family matters to tend. All collaborators must have a strong commitment and are determined to make things happen. On time and every time.

Most project managers would agree that successful projects are completed within the agreed timeframe by adhering to agreed milestones. Naturally, it would require having one's ego in check. The success of the project must be placed at the top of everyone's agenda without having to prove who's the best or the smartest or the most talented. This said, aligning a team's morale is as hard as keeping them focused.

For fiction projects, the tone, the plot, the structure, and the characters must be agreed upon in advance, so the expected completion of each milestone can be scheduled accordingly. For non-fiction papers, every section must go through technical scrutiny to ensure accuracy before it's written down and finally edited for grammatical and punctuation errors. Luckily, now we have cloud-based apps to facilitate such real-time and instantaneous tasks.

All collaborators should be on the same level of technical mastery. However, their skills shouldn't be too identical that they overlap with each other.

For example, for a business book, the co-authors should have an agreeable understanding of various concepts, such as the key terminologies and theories. With such a solid foundation, it would be easier to write about topic details without misunderstanding.

If you belong to an institution, such as a corporation or a training school, you will most likely find colleagues with whom you can discuss things freely. For instance, if both of you went to a graduate school together, you would most likely agree on certain key concepts.

If both of you have disagreements on crucial concepts that would influence the direction of the project, you can request assistance from an instructor for clarification. Remember, as a team. It's essential to be on the same page on key issues. In a nutshell, all project executors must be willing to work out their differences to kick start the project without delay.

When all writers reciprocate well by adding value with minimal overlaps, most likely, they're good partner candidates. However, personality types matter as well. Remember that no one is perfect. Everybody has their strengths and weaknesses.

You can "test the water" by asking several strong candidates to work on a so-called "mini-project." The thing is, since it takes at least one or two hours of their time, you might need to make sure that they're aware of the hours involved.

Also, make sure to find a way to compensate test takers regardless of the limited hiring budget. It can be in the format of gift cards of a specific value, such as $50 or $75 or $100 or $150 to offset the time they've spent working on the demo projects.

Completing a writing project involves several steps from planning, ideation, first draft writing, copyediting, to final editing. Thus, each step would require all writers to share files, see what each writer is doing in real-time, and be able to edit other writers' works (if necessary and upon agreement).

Using several writing collaboration apps, such as the following, would allow collaborators to optimize their resources, especially time and budget.

For group or team chat and phone/video chat, use Slack , Zoom , and Skype .

For real-time project and milestone management, use Asana or Trello .

For checklist management, use WorkFlowy or Todoist .

For quick sharing of files, use Google Docs or Microsoft Word Online .

For sharing and keeping standard files, use Dropbox or Google Drive .

For grammar and plagiarism check, ProWritingAid is an excellent choice.

Collaborative writing has been done for decades or even centuries. Both fiction and non-fiction works can be done collaboratively.

For collaboration to succeed, all writers must be on the same level in commitment and determination in making things work within the agreed timeframe. Numerous collaboration apps can be used to ensure smooth execution and completion, from planning to final editing processes.

Be confident about grammar

Check every email, essay, or story for grammar mistakes. Fix them before you press send.

Jennifer Xue

Jennifer Xue is an award-winning e-book author with 2,500+ articles and 100+ e-books/reports published under her belt. She also taught 50+ college-level essay and paper writing classes. Her byline has appeared in Forbes, Fortune, Cosmopolitan, Esquire, Business.com, Business2Community, Addicted2Success, Good Men Project, and others. Her blog is JenniferXue.com. Follow her on Twitter @jenxuewrites].

Get started with ProWritingAid

Drop us a line or let's stay in touch via:

Building a killer writing team - 6 tips you shouldn't miss

Gordana Lasković

Collaborative writing is an excellent way to craft compelling written work, and it's beneficial for content writers. The beauty of this approach is that it allows multiple writers or an editor to work together to brainstorm ideas and compose a finished piece.

However, collaborative writing requires a certain level of skill and finesse to ensure success.

In this blog, we'll explore the key elements of effective collaborative writing and offer tips on how to make the most of group work to create high-quality content. By tapping into the power of teamwork , a collaborative writing project can result in a remarkable finished product that captures the collective voice of the team.

You'll learn how to leverage project management tools to streamline workflow, how to handle conflicts, and how to celebrate the success of your collaborative writing efforts.

Whether you're an experienced writer or new to collaborative writing, this guide will equip you with the knowledge and tools you need. It will enable you to make your next group writing project a resounding success.

So let's get started and explore how you can unleash the power of teamwork to produce outstanding written work.

Tips for successful collaboration

Define the project's goals and objectives.

Before you begin working together, you need to have a clear understanding of what you're trying to achieve and how you plan to get there. This means identifying the target audience , deciding on the tone and style of the writing, and determining the scope of the project.

A famous saying by George Harrison, one of the members of the Beatles , is as true for writers as it is for travelers:

“If you don't know where you're going, any road will take you there.”

Once you have a plan and a clear goal in mind, you can start crafting the perfect content to meet your objectives.

Identify the roles and responsibilities

Once you've established these goals and objectives, the next step is to define the roles and responsibilities of each team member. This means deciding who will be responsible for researching, drafting, editing, and reviewing the document.

It's like putting together a puzzle. Each piece has its unique shape and size, and it’s up to the team to make sure that the pieces fit together to create a cohesive whole.

Establishing clear roles and responsibilities from the start will help avoid confusion and ensure everyone understands what they're expected to do.

Collaborate on ideas

At the beginning of the writing process, why not gather your team together for an exciting brainstorming session?

This is the perfect time to shape your thesis statement and decide on the main focus of your writing project. You'll all have the chance to share ideas and discuss the direction of your final masterpiece.

During this exciting stage, be sure to listen carefully to your collaborators and hear what they have to say. Remember, the most successful writing projects are the result of collaboration, with each member contributing to crafting a well-rounded argument and defense.

It's natural to expect some differences of opinion when you're working with a group, but don't worry!

By embracing critical thinking and taking the time to understand each other's ideas, you can overcome any challenges and find common ground to move forward.

Choose how writing takes place

Collaborative writing is a process that allows a team to work together to create a single, unified document. But with so many different methods and tools available, how do you know which one to choose?

The answer is simple: choose how writing takes place! This means that your team has the freedom to select the method that works best for them.

By choosing how writing takes place, you can create a custom approach that suits your team's work style and preferences. This not only makes the writing process more enjoyable but also helps to increase productivity and produce higher-quality writing that meets your project's goals and objectives.

This is similar to picking the right tools for a job. You may have a hammer and a screwdriver, but if you need to drive a nail into the wall, the screwdriver won't be as effective as the hammer. Choosing the right tool for the job will help you do the task more quickly and easily while producing a better result.

So, whether you're a team that loves to brainstorm together in person or one that prefers to work asynchronously, don't be afraid to choose how writing takes place. With the right tools and approach , you can create a collaborative writing environment that's tailored to your needs and produces amazing results.

Use the right software

Your business needs and budget should be taken into consideration when choosing software.

Research potential providers and compare features to ensure you find the right fit. Make sure to consider long-term scalability, customer support, and other factors.

The global software services market is expected to reach a value of USD 872.72 billion by 2028.

Some of the software and tools you can consider include:

- Google Docs : It allows you to collaborate in real-time on a document or alternatively, you can upload your sections to the shared document.

- Microsoft Word : Real-time editing features are now available in Word 365 , which facilitate collaborative work on a document through a URL.

- Wiki software : It enables numerous authors to participate in creating a document, as seen in the software used for Wikipedia. An instance of this is Slab , a wiki tool that can be utilized by teams within an organization to collaborate.

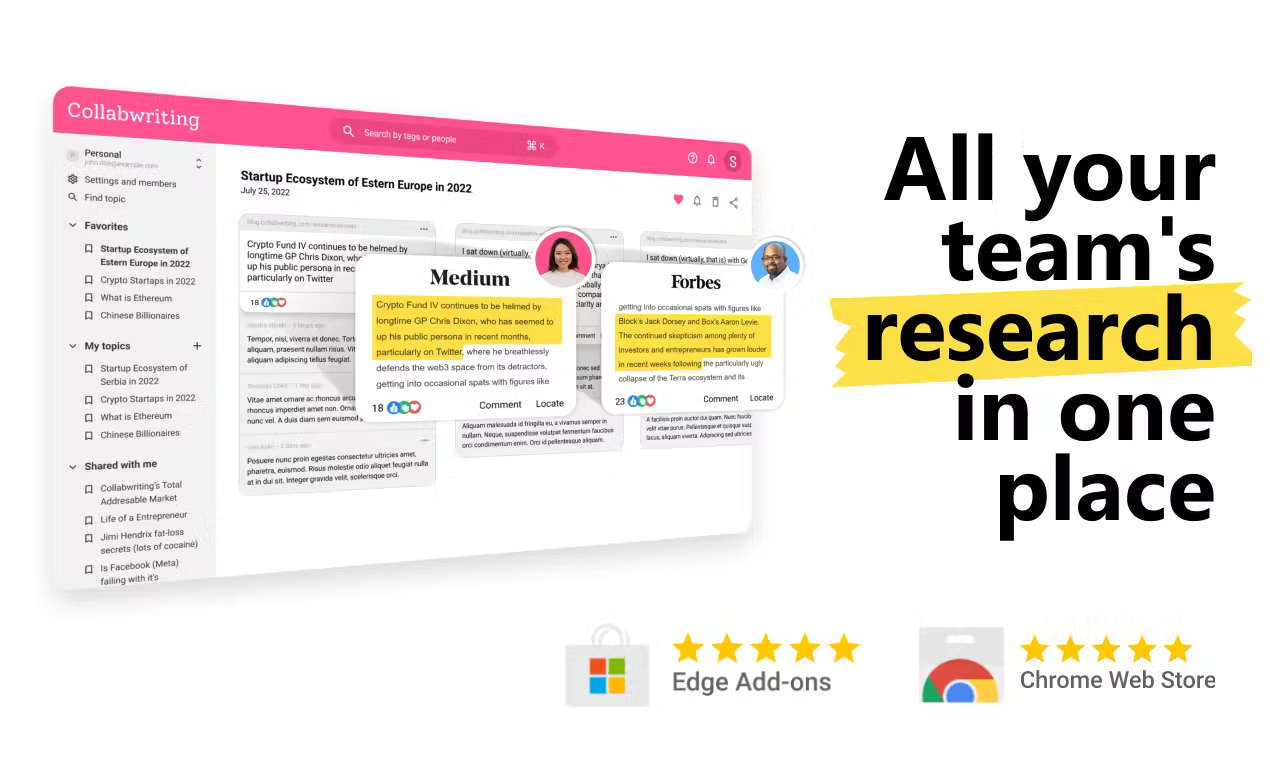

- Collabwriting : An actionable knowledge base for your team that helps you to:

- Collect data, ideas, and references

- Create a shareable and searchable system

- Receive feedback and collaborate with your team

Many of these tools are free or low-cost. It's important to research the different options to find software that best meets your needs.

Once you find the right platform, you can use it to create an effective collaboration system.

Working alongside editors

Collaboration isn't just limited to group writing activities.

It's also about working hand-in-hand with your editor to create a masterpiece that you can both be proud of. After all, your editor is part of your writing team, and together, you can achieve greatness!

With the help of group writing software, editors and writers can quickly edit and make changes to documents. This collaborative approach to the editing process not only saves time but also allows you to benefit from your editor's valuable insights . With their feedback, you can easily tweak your work until it's flawless and ready for publication!

Companies that promote collaboration and communication at work have reduced employee turnover rates by 50% and employees are 17% more satisfied with their job when they engage in collaboration at work.

So, don't be afraid to embrace collaboration with your editor. With their expertise and your talent, you can produce written work that will truly make an impact.

Collabwriting - Shareable Notes on Web Pages and PDFs

Collabwriting allows you to gather all your online sources in one place. Just highlight, save, and collaborate with anyone on any content you find online.

Final notes

Collaborating with other writers can be a game changer.

By working with others, you'll gain valuable insights into your strengths and weaknesses as a writer.

Collaboration allows you to learn from others, refine your critical thinking skills, and enhance your overall communication abilities . With the right approach, this process can help you create a truly outstanding piece of writing that you can be proud to showcase.

75% of employees think that collaboration and teamwork are essential, but 39% of them also think that their companies could be more collaborative. Moreover, between 2019 and 2021, the use of collaboration tools in workplaces increased by 44%.

Therefore, don't be afraid to team up with other writers and explore what you can achieve together.

With collaboration, the possibilities are endless!

Join the Collabwriting community today

Our websites may use cookies to personalize and enhance your experience. By continuing without changing your cookie settings, you agree to this collection. For more information, please see our University Websites Privacy Notice .

Writing Center

Collaborative writing resources.

A collaborative writing project Stacie Renfro Powers, Courtenay Dunn-Lewis, and Gordon Fraser University of Connecticut Writing Center

The resources that follow include ideas, research, and worksheets to help instructors integrate collaborative writing projects (CWPs) into their curriculum. Some techniques will be more practical for larger projects or projects of extended length. Many of the class resources are available in Microsoft Word and are intended to be customized for to the specific needs of each project.

General Considerations:

A. there are many ways to write collaboratively in the classroom..

In a practical sense, classroom collaboration can involve writing text together or separately, editing another’s work, peer reviewing in a face-to-face/virtual environment, or all (or none) of the above. It may involve running drafts by colleagues or having an editor piece together multiple contributions. Class assignments and deadlines may dictate some of this – or an instructor may simply let it happen organically.

While individual writing emerges from several iterations of brainstorming, organizing, writing, and refining, group writing multiplies these efforts. The process varies according to the group composition, experience, and constraints. This is confirmed in the literature, as no author advances a “best practice” for collaborative writing. In fact, as will be discussed below, almost all of the advice for collaborative writing centers on how to manage group workflow and dynamics.

B. Should a group project in the classroom reflect the “real world?”

Collaboration in the professional world is presented in a variety of scenarios – from a single author soliciting advice from colleagues to co-authored texts where input is equally shared. Some believe that it is important to model writing collaboration projects after the professional process (as a student might encounter them in their career). However, team writing in the professional context is not intended to be an educational experience. As Speck (2002) points out, “real world” work is not often evenly distributed. Professionals who are not able to contribute effectively may be dropped from a project with little fallout. These differences do not allow academic projects to maintain the style of those in the “real world.” The payoff of successful academic collaborative writing projects, however, should translate into better group skills when students do move into the working world.

The collaborative process in an academic setting is a valuable, predominantly educational, experience. Many students are still growing in their ability to write and work with the writing of others. Generating a coherent product from multiple student voices (and, at times, multiple academic disciplines) may be demanding. As Price and Warner (2005) write: “Our challenge is to find ways to help our students render the layers visible, so that we can offer them guidance as detailed and complex as their processes of composing warrant. This may mean letting go of values such as “coherence,” and inviting the potential benefits of mess.” It also means that the process becomes an integral part of the learning experience. In other words, challenging students to pursue a project – even in a manner that is not always smooth and does not always reflect the professional process – may allow them to become better at collaboration, writing, and other career-related skills.

C. Anticipating Obstacles is Important.

Research has shown that receiving personal satisfaction from group experiences is an important predictor of willingness to join other task groups, the ability to generate higher quality decisions, and increased commitment to those decisions (Hall, as cited in Bogert & Butt, 1990). However, while students are initially more concerned with the task than the group dynamics, successful completion of the task is not enough to leave them feeling satisfied with the outcome (Bogert & Butt, 1990). Embarking on a collaborative writing project in class requires an instructor’s awareness of the potential obstacles at play, their role in managing such obstacles, and strategies for prevention.

In an analysis of videotapes of group communication patterns, students encountered “the substantive, procedural, and relational problems experienced by many other problem solving groups” (Hirokawa & Gouran, as cited in Bogert & Butt, 1990). These issues included task-related problems that directly affect writing quality. These students experienced difficulty in testing ideas critically, in evaluating alternatives, and in achieving closure on important items. The tendency to introduce irrelevant discussion, failure to consider interpersonal relationships and authority relations, and outright conflict further compounded the bad experiences. The affected students were less likely to want to work in groups in the future.

Experienced instructors emphasize the importance of effective group communication as a foundation for successful collaborative writing experiences. While it is possible for most group projects to be successful even if there is no intervention, Mead (1994) estimates that about one in four groups will experience some kind of conflict that requires instructor mediation. Other techniques described below, such as monitoring students and ensuring proper group formation, can greatly improve the outcome of the group process.

Implementation:

1. group formation.

There are several considerations at play as far as group membership is concerned. Some instructors have found that students do better when they are assigned to groups. This ensures diversity, which leads to less groupthink and more substantive discussions. For large projects that require a lot of out-of-class meeting time, students may want to identify peers with similar schedules, interests, or campus residences. Speck recommends giving the students a sign-up sheet and leaving the room for 15-20 minutes.

Once groups are formed, other strategies may be useful depending on the expectations of the project. It is usually useful to conduct some initial icebreaker tasks to allow group members to get to know one another. Another option is to have group members take a personality test, such as the Myers-Briggs Inventory, to help identify their strengths for their group members (Deans, 2003).

2. Preventative Organization

Instructors can take several preventative steps to optimize group effectiveness and reduce the potential for conflict. Some of these steps can be performed prior to assigning team roles. For example, it is often useful to establish a group’s consensus on its own operations (meeting times, grade goals, policies for differences of opinion). To prevent group discord, a group contract can be used to create a consensus on expectations.

Either before or after assigning roles, formulating a group proposal can help an instructor to evaluate whether teams are putting energy into useful projects or doomed endeavors. Such proposals may accompany a writing plan, which will help with the organization of the project and distribution of work. (Please see the next section for more information on assigning roles).

- Group Contract

- Collaborative Writing

- Writing Plan

3. Assigning Roles

Issues of fairness can overshadow the learning process and can take up unplanned-for time. Assigning roles can facilitate communication processes and create comfortable conditions for constructive disagreement. You and/or the students may decide that it is preferable to rotate who is responsible for administrative roles (such as the meeting leader and note-taker) so that everyone has a chance to organize the process (Speck, 2002, p. 70).

It may be useful to consider roles in two categories: those concerned with accomplishing a task, and those concerned with maintaining group relations. Task roles may include initiators, information seekers/givers, opinion seekers/givers, clarifiers, elaborators, and summarizers (Speck, 2002, pp. 66-71). Group maintenance roles include encouragers, feeling expressers, compromisers, and gatekeepers. Before a big discussion, it is helpful to identify a devil’s advocate, or person who will challenge the group’s arguments and approaches in order to clarify them (p. 91).

For a short reading and group assignment on roles, see: http://www.mindtools.com/pages/article/newTMM_85.htm

4. Dedicated Class Time.

Including a collaborative writing project in a curriculum brings up several issues for time management. Instructors must consider the schedules of students and their abilities to meet. In addition, instructors often raise concerns on finding the time to give feedback on the writing and the process itself. A combination of dedicated class time and instructor monitoring typically improves the quality of projects and reduces time concerns (please see the next section for more on monitoring).

Many resources recommend scheduling class time for group work and group conferences. This does result in less time for lecture and other classroom activities. However, this allows instructors to become more familiar with each group’s work when it is still in its formative stages. Instructors may also find that they can anticipate issues more readily and detect groups that are stalling. Instructors can then save a lot of the time that they would otherwise have spent reading and commenting on poor drafts.

5. Group Meetings and Monitoring.

Advocates of collaborative writing stress the need to intervene during the entire process. This includes monitoring during class time, establishing meeting requirements, and/or monitoring meetings themselves. Monitoring helps to confirm that the process is going smoothly, that each group is compatible, and that work is effective. Instructors may choose to meet with groups beginning in the first week. This allows instructors to answer questions, confirm roles, and clarify expectations (Kryder, 1991). Thereafter, requiring group or individual conferences throughout the project can help ensure continual progress.

To enhance the effectiveness of such activities, groups can supply a meeting plan prior to the meeting and supply a progress report after each meeting. A decision making guide, while advantageous for any decision a group is faced with, may also help resolve conflict.

- Decision Making Guide

- Meeting Planning Guide

- Weekly Progress Reports

6. Evaluation

Just as the process of collaborative writing can be an educational experience, so can the process of evaluation. You may want to allow students to modify evaluation questions and criteria. This may be useful as a learning tool, as it can help them to gain more perspective on the process. For example, Speck recommends letting students give input into how to weight the group evaluation criteria.

- Peer Review Worksheet

- Evaluation of a Team Member’s Contribution

Further References

Books and articles that can help start the conversation:.

- Ronald, K. & Roskelly, H. (2002) Learning to Take it Personally: The Ethics of Collaborative Writing.* In D. H. Holdstein & D. Bleich (Eds.), Personal Effects: The Social Character of Scholarly Writing. Logan, Utah: State University Press.

- Bruffee, K. A. (1999). Collaborative Learning (Second ed.). Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Ede, L., and Andrea A. Lunsford. (Mar. 2001). Collaboration and Concepts of Authorship. PMLA, 116(2), 354-369.

- Hyman, D., & Lazaroff, B. (2007). With A Little Help From Our Friends: Collaboration and Student Knowledge-Making in the Composition Classroom. In F. Gaughan & P. H. Khost (Eds.), Collaboration(,) Literature(,) and Composition (pp. 127-145). Cresskill, New Jersey: Hampton Press, Inc.

- Price, M., & Warner, A. B. (Dec. 2005). What You See Is(Not) What You Get: Collaborative Composing in Visual Space. Across the Disciplines Retrieved Nov. 1, 2007, from http://wac.colostate.edu/atd/visual/price_warner.cfm

- Reither, J. A., and Douglas Vipond. (Dec. 1989). Writing as Collaboration. College English, 51(8), 855-867.

- Spooner, M. & Yancey, K. (1998). A single good mind: Collaboration, cooperation, and the writing self. College Composition and Communication, 49(1), 45-62.

- Bogert, J. & Butt, D. (1990). Opportunities lost, challenges met: Understanding and applying group dynamics in writing projects. Bulletin of the Association of Business Communication, 53(2), 51-58. Retrieved from ERIC database (EJ411597).

- Deans, T. (2003). Writing and Community Action: A Service-Learning Rhetoric with Readings. New York: Longman.

- Speck, B. W., Johnson, T. R., Dice, C. P., & Heaton, L. B. (1999). Collaborative Writing: An Annotated Bibliography. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press.

- Speck, B. W. (2002). Facilitating Students’ Collaborative Writing. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Kryder, L. G. (1991). Project administration techniques for successful classroom collaborative writing. Bulletin of the Association for Business Communication, 54(4), 65-66. Retrieved from ERIC database (EJ439195).

- Mead, D. G. (1994). Celebrating Dissensus in Collaboration: A Professional Writing Perspective. Paper presented at the 45th Conference on College Composition and Communication in Nashville, TN. Retrieved from ERIC database (ED375427).

- University of Maryland Graduate School of Management and Technology. (nd). Tips for Collaborative Writing. Retrieved online at http://www.umuc.edu/departments/omde/orientation/ collaborativewriting.pdf

- U.S. Locations

- UMGC Europe

- Learn Online

- Find Answers

- 855-655-8682

- Current Students

Online Guide to Writing and Research

Collaborative writing and peer reviewing, explore more of umgc.

- Online Guide to Writing

Collaborative Writing

Methodology.

When you are working on a major collaborative writing project, make sure that each member has at least two roles:

- The writer of a specific section of the project, and

- The specialist in one or more areas of the project. In addition to learning how to write this project, each team member should coordinate his or her individual effort, knowledge, schedule, and work habits with those of the other members.

This coordination requires courtesy, thoughtful communication, and dependability on everyone’s part.

Each team member should plan to write a specific section of the project—some members may write more than others, depending on their roles. Roles may overlap or be shared, depending on team members’ skills. Each student should take on two or more of the following roles:

- Group Leader

- Subject Matter Specialist

Everyone in the group writes and revises a specific part of the project.

This person coordinates the team, organizes the writing plan and schedule (especially for group meetings), and picks up loose ends.

This person edits and proofreads final drafts, provides stylistic standards for the group as a whole, and guides the group in using stylistic conventions and formats.

Each person is responsible for researching technical topics, helping other team members with technical problems, and testing the final project for accuracy. All members must become subject matter specialists in at least one area.

These next two roles may or may not be part of every group project. However, you want to be aware of them and have one or two members take on these roles if needed.

- Graphics Layout Artist and Production Manager

This person is responsible for project design, illustrations, layout, hard-copy and web formats, and the printing of the final project.

In web projects, this person is responsible for putting the project on the web and administering it

Each student should keep their own copy of the entire assignment, with all its parts, together in a portfolio or notebook as the group completes the individual assignments. The group then submits the completed project.

Your instructor may act as manager or ask that you manage your own team writing assignment. In either case, you should plan to meet as a group and decide which roles each of you will fulfill on the team and which sections of the project each of you will write. Your group may even write a contract for each member to agree to and sign. Plan to write all or some of them as a group and be sure your instructor gets copies of all of them.

Mailing Address: 3501 University Blvd. East, Adelphi, MD 20783 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License . © 2022 UMGC. All links to external sites were verified at the time of publication. UMGC is not responsible for the validity or integrity of information located at external sites.

Table of Contents: Online Guide to Writing

Chapter 1: College Writing

How Does College Writing Differ from Workplace Writing?

What Is College Writing?

Why So Much Emphasis on Writing?

Chapter 2: The Writing Process

Doing Exploratory Research

Getting from Notes to Your Draft

Introduction

Prewriting - Techniques to Get Started - Mining Your Intuition

Prewriting: Targeting Your Audience

Prewriting: Techniques to Get Started

Prewriting: Understanding Your Assignment

Rewriting: Being Your Own Critic

Rewriting: Creating a Revision Strategy

Rewriting: Getting Feedback

Rewriting: The Final Draft

Techniques to Get Started - Outlining

Techniques to Get Started - Using Systematic Techniques

Thesis Statement and Controlling Idea

Writing: Getting from Notes to Your Draft - Freewriting

Writing: Getting from Notes to Your Draft - Summarizing Your Ideas

Writing: Outlining What You Will Write

Chapter 3: Thinking Strategies

A Word About Style, Voice, and Tone

A Word About Style, Voice, and Tone: Style Through Vocabulary and Diction

Critical Strategies and Writing

Critical Strategies and Writing: Analysis

Critical Strategies and Writing: Evaluation

Critical Strategies and Writing: Persuasion

Critical Strategies and Writing: Synthesis

Developing a Paper Using Strategies

Kinds of Assignments You Will Write

Patterns for Presenting Information

Patterns for Presenting Information: Critiques

Patterns for Presenting Information: Discussing Raw Data

Patterns for Presenting Information: General-to-Specific Pattern

Patterns for Presenting Information: Problem-Cause-Solution Pattern

Patterns for Presenting Information: Specific-to-General Pattern

Patterns for Presenting Information: Summaries and Abstracts

Supporting with Research and Examples

Writing Essay Examinations

Writing Essay Examinations: Make Your Answer Relevant and Complete

Writing Essay Examinations: Organize Thinking Before Writing

Writing Essay Examinations: Read and Understand the Question

Chapter 4: The Research Process

Planning and Writing a Research Paper

Planning and Writing a Research Paper: Ask a Research Question

Planning and Writing a Research Paper: Cite Sources

Planning and Writing a Research Paper: Collect Evidence

Planning and Writing a Research Paper: Decide Your Point of View, or Role, for Your Research

Planning and Writing a Research Paper: Draw Conclusions

Planning and Writing a Research Paper: Find a Topic and Get an Overview

Planning and Writing a Research Paper: Manage Your Resources

Planning and Writing a Research Paper: Outline

Planning and Writing a Research Paper: Survey the Literature

Planning and Writing a Research Paper: Work Your Sources into Your Research Writing

Research Resources: Where Are Research Resources Found? - Human Resources

Research Resources: What Are Research Resources?

Research Resources: Where Are Research Resources Found?

Research Resources: Where Are Research Resources Found? - Electronic Resources

Research Resources: Where Are Research Resources Found? - Print Resources

Structuring the Research Paper: Formal Research Structure

Structuring the Research Paper: Informal Research Structure

The Nature of Research

The Research Assignment: How Should Research Sources Be Evaluated?

The Research Assignment: When Is Research Needed?

The Research Assignment: Why Perform Research?

Chapter 5: Academic Integrity

Academic Integrity

Giving Credit to Sources

Giving Credit to Sources: Copyright Laws

Giving Credit to Sources: Documentation

Giving Credit to Sources: Style Guides

Integrating Sources

Practicing Academic Integrity

Practicing Academic Integrity: Keeping Accurate Records

Practicing Academic Integrity: Managing Source Material

Practicing Academic Integrity: Managing Source Material - Paraphrasing Your Source

Practicing Academic Integrity: Managing Source Material - Quoting Your Source

Practicing Academic Integrity: Managing Source Material - Summarizing Your Sources

Types of Documentation

Types of Documentation: Bibliographies and Source Lists

Types of Documentation: Citing World Wide Web Sources

Types of Documentation: In-Text or Parenthetical Citations

Types of Documentation: In-Text or Parenthetical Citations - APA Style

Types of Documentation: In-Text or Parenthetical Citations - CSE/CBE Style

Types of Documentation: In-Text or Parenthetical Citations - Chicago Style

Types of Documentation: In-Text or Parenthetical Citations - MLA Style

Types of Documentation: Note Citations

Chapter 6: Using Library Resources

Finding Library Resources

Chapter 7: Assessing Your Writing

How Is Writing Graded?

How Is Writing Graded?: A General Assessment Tool

The Draft Stage

The Draft Stage: The First Draft

The Draft Stage: The Revision Process and the Final Draft

The Draft Stage: Using Feedback

The Research Stage

Using Assessment to Improve Your Writing

Chapter 8: Other Frequently Assigned Papers

Reviews and Reaction Papers: Article and Book Reviews

Reviews and Reaction Papers: Reaction Papers

Writing Arguments

Writing Arguments: Adapting the Argument Structure

Writing Arguments: Purposes of Argument

Writing Arguments: References to Consult for Writing Arguments

Writing Arguments: Steps to Writing an Argument - Anticipate Active Opposition

Writing Arguments: Steps to Writing an Argument - Determine Your Organization

Writing Arguments: Steps to Writing an Argument - Develop Your Argument

Writing Arguments: Steps to Writing an Argument - Introduce Your Argument

Writing Arguments: Steps to Writing an Argument - State Your Thesis or Proposition

Writing Arguments: Steps to Writing an Argument - Write Your Conclusion

Writing Arguments: Types of Argument

Appendix A: Books to Help Improve Your Writing

Dictionaries

General Style Manuals

Researching on the Internet

Special Style Manuals

Writing Handbooks

Appendix B: Collaborative Writing and Peer Reviewing

Collaborative Writing: Assignments to Accompany the Group Project

Collaborative Writing: Informal Progress Report

Collaborative Writing: Issues to Resolve

Collaborative Writing: Methodology

Collaborative Writing: Peer Evaluation

Collaborative Writing: Tasks of Collaborative Writing Group Members

Collaborative Writing: Writing Plan

General Introduction

Peer Reviewing

Appendix C: Developing an Improvement Plan

Working with Your Instructor’s Comments and Grades

Appendix D: Writing Plan and Project Schedule

Devising a Writing Project Plan and Schedule

Reviewing Your Plan with Others

By using our website you agree to our use of cookies. Learn more about how we use cookies by reading our Privacy Policy .

What Is Collaborative Writing? Everything You Need to Know

What is collaborative writing? Learn more about what it is like to complete a writing project with other team members.

There are a lot of group projects that people complete at all levels, and some are asked to complete group writing projects. This is called collaborative writing, and it involves brainstorming, writing, revising, and publishing writing projects with the help of other group members.

Many moving parts happen during collaborative writing projects, and multiple writers are typically employed to complete different tasks. For example, one person might be responsible for the first draft, while another might be responsible for the editing process. One writer might have the authority to go in and change something that another writer has written. This writing process can be helpful in certain situations. What is involved in finishing a project?

Collaborative Writing Example

Single author writing, sequential single writing, parallel writing, reactive writing, mixed mode writing, turn writing engagement, lead writing, communication is critical, be clear about the roles, create specific deadlines, know who to go to for help, use real-time collaboration tools.

One of the top examples of collaborative writing in action is the process of creating Wikipedia entries. These are articles that multiple people write, then edited by admins, followed by changes suggested by various readers. This is a collaborative writing environment where individual duties are demarcated between different groups of people.

Every writer has equal abilities and authority in the perfect collaborative writing environment. They can engage in writing, editing, adding, removing, and changing various parts of the project. Successful collaborative writing leads to publishing a final product that is as accurate as possible. That is what happens with Wiki articles.

Different Types of Collaborative Writing?

Group work comes in many shapes and forms. Collaborative writing is no different. There are several different types of collaborative writing, and some of the most common types include:

One of the most common types of collaborative writing is called single-author writing. In this type of writing, one person represents an entire team that works together to produce written work. For example, multiple people might work on files in Google Docs. They might be responsible for writing their work, sending it to an editor for proofreading, and then publishing it under one person’s name. It looks like individual work, but in reality, many people play significant roles in getting the project done.

One of the most common examples of this type of project is when multiple people publish blog posts for a lawyer, but based on the website, it looks like the leading lawyer is responsible for doing all of the work. This also means that the person whose name is on the final product is responsible for the accuracy of the facts that get presented. You might also be interested in our explainer on what is mapping in writing .

Another common type of collaborative writing is called single sequential writing. This type of project occurs when a group of writers works on a single area of the writing project, but they all take place in a sequence. This means that one person works on the first part of the article and then passes it to the second writer to work on the next part of the article.

Peer review takes place because the second writer can change the work of the first writer. For example, one person might be responsible for brainstorming. Then, that person might pass an outline to the second writing team member for the next writing task, which might mean putting together a rough draft. After that, the next writer will be responsible for the writing style, ensuring that the right tone is struck. Finally, a fourth writer might be responsible for ensuring all of the publication requirements are met.

Parallel writing is similar to single sequential writing in that members are responsible for different project areas. The difference is that different parts of the project are handled simultaneously. For example, when the first part of the article is outlined, it might get passed to the next writer to take the research and complete a draft; however, the first writer might be responsible for outlining another portion of the article while the next writer is working on writing the first portion.

In this case, collaborative learning is also necessary because the first writer might take the feedback from the second writer and use it to create a better outline for the next portion of the assignment. This could expedite the process of getting the article finished. There are also a lot of collaborative tools that could be used in this situation to make the process easier.

Another one of the most popular collaborative writing strategies is called reactive writing. This type of collaborative writing process occurs when different team members go through different projects that are completed by different team members and suggest changes.

This is where Google Docs can be helpful because someone can comment on the doc in real-time, making it easier for one co-author to “react” to the work that has been written, suggest changes, and ensure everyone knows what is happening before the project is finalized. This type of division of labor is beneficial because it ensures the final document is credible. With so many people sharing their information, the final document is more likely to be accurate and represent the group’s opinions. This is one of the most common types of collaborative writing, mainly when an editor is involved.

The mixed mode type of collaborative writing is a blend of the above. For example, a group of people could work face-to-face on a group assignment to put together a rough draft. Then, the entire team might pass the document to another group of people who react to it.

There might be some personal writing, but every group member works on it in real-time to produce a final draft. Different team members might have specific tasks assigned to them. Still, once they finish their tasks, they become reactive members or learners, working with others to complete the project as quickly as possible while ensuring the final draft is as solid as possible. This is one of the most common types of collaborative writing and is great for learning.

Different Types of Engagement In Collaborative Writing

For collaborative writing to work as well as possible, it is critical to ensure that everyone is as engaged with the rest of the team as possible. In general, there are two ways to ensure everyone is engaged with the project as it unfolds. They include:

The first type of engagement is called turn-writing engagement. This type of writing takes place where there are multiple authors who each contribute to different sections. They suggest changes and additional modifications. Then, they check the sections, implement the suggested changes, and publish them. This type of engagement is called turn writing because each writer takes a turn before passing it to the next team member. Everyone takes a turn, and everyone has a voice.

The other type of engagement is called lead writing. There might be a specialist who is given a piece to compose. For example, a scientist might have a research project that has to get published. They will write down their thoughts on the topic but give the piece to another writer to ensure the voice and style are great. Before the piece can be published, the assignment is given back to the expert, who reviews the changes and ensures the information is still accurate. Again, they will voice their thoughts to make sure the information will have the intended impact on the reader before publishing it.

Top Tips for a Strong Collaborative Writing Process

Even though collaborative writing can be a great way to complete a writing project, there are also a lot of challenges along the way. Everyone should follow a few tips to make sure the piece goes as smoothly as possible. Some of the top tips to keep in mind include:

One of the most common reasons why people have trouble during the collaborative writing process is that they do not communicate with one another. Particularly in the current environment, there are a lot of people who work remotely. If group members do not communicate well with each other, they will have difficulty figuring out when something is ready for their review. This can lead to delays and scope creep during the project, leading to a sloppy finished product. Therefore, it is helpful to use a communication tool, such as Slack , to make it easier for people to stay in touch during the project.

Speaking of communication, it is helpful to ensure everyone knows their role. Sometimes, a project can get going, but many people do not know exactly who is responsible for what. As a result, some people might end up working on the same part of the project, leading to confusion in the group. Then, there are other areas of the project that might fall through the cracks. It might be helpful to use a project management tool, such as ClickUp , to make it easier for people to see the deliverables.

It is not unusual for a collaborative writing project to be turned in late because people do not know what the deadlines are and when different parts of the project are due. For example, the group might only see the final deadline, but if someone does not pass the project to the next person fast enough, the next person might not have adequate time to do their portion of the project. That is why it is helpful to set deadlines for the individual pieces, not just the final project.

When a collaborative writing project gets going, it is critical to ensure everyone knows who to go to for help. With many people in the group, some members might not know who to call if they need help. Ensure all relevant contact information is shared and group members know who the next person in line might be. This could be an excellent place to start if someone needs help with a portion of the project, and it can reduce the phone (or text) tag people play.

Finally, with every collaborative writing assignment, it is critical to use real-time collaboration tools. If the document has to be saved and emailed before the next person can start working, it is hard to know the most recent version of the project. So instead, use real-time collaboration tools that allow multiple people to work on the file simultaneously. Then, people know what version of the project is the most recent one (because there will only be one), and they can see who has made what edits to the file.

If you are interested in learning more, check out our essay writing tips !

It doesn’t have to rhyme: Collaborative creative writing as a community tool

28 April 2022 | Mel Parks

Mel Parks shares ideas on using collaborative creative writing in community settings to bring people together, creating a unified experience often with the added benefit of new insights and surprising connections. As well as being lots of fun!

Many people are scared of poetry and creative writing often brings back memories of school, and often not good ones, so I always tread lightly and carefully. Even the people that sign up to my weekly creative writing workshops tell me they don’t write poetry, but when I break it down, step by step, they almost always join in, give it a go and find a form that speaks to them. It is always okay for people to contribute a word or two rather than whole lines, to speak aloud their words instead of writing them down, and to offer their work anonymously.

Collaborative poetry can represent many voices and one voice is not privileged over another. It can be a snapshot in time and work with a theme or message you want to get across or explore. Words contributed from less confident writers can be absorbed into the whole and they can enjoy having their work shared with a wider audience, without their name on a particular part.

For people who work visually or who would rather work with words that already exist, instead of having to make up lines or sentences, I offer collage, found or blackout poetry workshops . This is making poems from text that already exists. We cut up magazines, block out lines on pages of old books, or draw on newspapers, making new and surprising connections between words and phrases. To do this collaboratively, you could work on larger paper, cut out and stick found poems together.

Collaborative story games involving no writing

The one-word story game.

This is a fast-paced game. Can be played by as many people as you have available. Everyone is only allowed to say one word. Someone starts with a beginning word, for example, ‘Once…’, the next person continues the story but only saying one word, for example, ‘upon’ and so on.

The sentence story game

A variation on the one-word story game but players are allowed to say a sentence or a fragment. Am not strict about whether it’s a sentence or not, just the next part of the story, but some people enjoy hogging the limelight so a limit can be helpful!

Fortunately, unfortunately

Tell a story in the circle, but each person has to take it in turns to start with Fortunately… or Unfortunately….

These games can go on for as long as you like. It’s helpful to give a warning that the end is coming, for example, ‘one more round, then Sam can say the ending’.

Collaborative writing games

This is based on the old Consequences game, where one person writes something, folds it over and passes it to the next person in the group. It is anonymous but it helps if you are sure everyone is confident that what they write can be read by other people. Writing skill can be basic as long as it is legible! Everyone has a blank sheet of A4 paper to begin with.

Questions and answers

Following the order of the prompts below, write question, answer, question, answer, folding over and passing round after each one. Unfold and read out. The answers can be surprisingly appropriate and are often funny. The questions and answers could all be based on an agreed theme.

Answer to a why question (you won’t see the question first so this is a random answer, beginning with because…)

Answer to a where question

Answer to a when question

Answer to a how question

Answer to a who question

Pass the paper with no folding

This is a great way to work on collaborative poems or stories. Someone writes the first part of a story or the first line of a poem, then pass round and the next person reads what has been written, writes the next part or line. And so on. I also use this game to practise writing dialogue – two characters having a conversation in writing by passing paper back and forth. A great starter for this is ‘Did you hear what happened last night?’.

Two examples of my collaborative poetry projects outside of workshops:

A community festival – I had a stall with luggage tags, writing prompts and string tied up like a washing line. People wrote their impressions of the festival on the tags, then hung them on the line. They could read what other people had written and respond to those ideas. I encouraged them to use all their senses, as well as share their feelings.

At the end of the day, with the help of my 10 year old child, I typed up the lines and arranged them. I usually change no words, but I might change to past or present tense to make it consistent with the rest of the poem. If the poem is to be published or printed, I will make the punctuation consistent too. The following day, the festival compere read out the poem.

An academic research project – During the pandemic, I was invited to be a researcher on a project looking at stories of gender-based violence during the Covid-19 pandemic . We didn’t want to ask participants to do anything we weren’t prepared to do ourselves and so as part of the research, we wrote our own remembered stories of gender-based violence. These came out as fragments, which often happens with traumatic memory and is one of the reasons that poetry is so fitting in this work.

I wanted to link the fragments together somehow and came up with the idea of creating a renga. This is an ancient Japanese collaborative poetic form made up of linked verses. Having rules (number of lines, syllable count) helped to contain emotions of difficult experiences. We did this by email – writing one stanza, emailing it to the next person on the list who added their own to the growing poem. But I have also done it in person and on Zoom. The important thing is that each verse or stanza responds to an idea, word or theme in a previous one, which helps to make connections and tie the whole poem together.

Writing often feels like a solitary act, but each time I facilitate collaborative creative writing, I am reminded of the power of sharing stories, truly listening and responding to each other and our own individual voices. We all have something to say and together we can say it louder!

Further reading

Parks, M., Holt, A., Lewis, S., Moriarty, J., Murray, L. (Accepted/In press) ‘Silent Footsteps: Renga poetry as a collaborative, creative research method reflecting on the immobilities of gender-based violence in the Covid-19 pandemic’, Cultural Studies <=> Critical Methodologies , Sage Journals.

Phillips, R., & Kara, H. (2021). Creative Writing for Social Research . Bristol: Policy Press.

Mel Parks is a writer, researcher and workshop facilitator as well as the editor of Ideas Hub. She has an MA in Creative Writing (Distinction) and her research values creative practice for social change. She specialises in the maternal, building on 20 years’ experience writing about children and families. She also works with myths, fairy tales and stories of place. www.honeyleafwriting.com

Share this article:

Similar articles.

Grenfell Memorial Community Mosaic: Collective Power Awards

Celebrating and learning more about CHWA Awards joint winner, The Grenfell Memorial Community Mosaic, which has brought almost 1,000 local people from North Kensington together to make large scale public artworks. Co-created with individuals and local community, resident, faith and school groups under the guidance of mosaic artists Emily Fuller and Tomomi Yoshida.

Gloucestershire Creative Health Consortium: Collective Power Awards

Celebrating and learning more about one of the CHWA Awards joint winners: made up of Art Shape; Mindsong; The Music Works; Artlift and Artspace. They all work in partnership to provide high quality, personalised, inclusive and accessible creative health services for people experiencing psychological and/or physical challenges.

2.8 Million Minds: Collective Power Awards

This blog features the 2.8 Million Minds project. Between November 2021 and May 2022, over 120 people contributed to A Manifesto for 2.8 Million Minds, a youth-led, artist-centred, and Disability Justice-informed approach to how young Londoners want to use art to begin to radically reimagine mental health support, justice and pride.

Collaborative Writing Projects: Pros, Cons, and Tips for Success

Collaborative writing projects offer a unique opportunity for writers to combine their talents, creativity, and perspectives to create something greater than the sum of its parts. However, navigating the complexities of collaborative writing requires careful planning, communication, and teamwork. Today, we will explore the pros and cons of these projects by drawing insights from famous writers who have successfully collaborated on various literary endeavors. We will also look at some practical tips for your own successful collaboration.

Pros of Collaborative Writing Projects

Collaborative writing projects offer several advantages, including the opportunity to pool diverse talents and expertise. Writers can complement each other’s strengths, resulting in a more well-rounded and dynamic final product. Additionally, working together fosters creativity and innovation through brainstorming sessions, idea exchanges, and collective problem-solving. This shared accountability can help maintain momentum and motivation throughout the writing process, reducing the likelihood of procrastination or writer’s block .

Cons of Collaborative Writing Projects

Despite the many benefits, collaborative writing projects also present challenges. One potential drawback is the risk of creative differences and conflicts arising. Different writing styles, visions, or expectations may lead to tension and compromise the cohesion of the project. Additionally, coordinating schedules and managing communication among multiple writers can be logistically challenging, especially if collaborators are in different time zones or have conflicting commitments.

Examples of Successful Collaborative Writing Projects

Famous writers throughout history have engaged in successful collaborative writing projects, demonstrating the potential of collective creativity. One notable example is “The Kingkiller Chronicle” series by Patrick Rothfuss, which features a cohesive narrative crafted through collaboration with editors, beta readers, and fellow writers. Similarly, Good Omens by Neil Gaiman and Terry Pratchett exemplifies how two authors with distinct voices can blend their talents to create a beloved literary work.

Establishing Clear Roles and Responsibilities

To ensure the success of a collaborative writing project, it’s essential to establish clear roles and responsibilities from the outset. Define each collaborator’s contributions, areas of expertise, and expectations for the project. Clarifying roles helps minimize ambiguity and ensures that everyone is aligned with the project’s goals and vision.

Effective Communication and Collaboration Tools

Effective communication is the cornerstone of successful collaboration. Use tools and platforms that facilitate seamless communication and collaboration among team members. Whether it’s project management software, cloud-based document sharing, or video conferencing tools, choose platforms that suit your team’s needs and preferences.

Setting Realistic Deadlines and Milestones

Setting realistic deadlines and milestones is crucial for maintaining momentum and accountability in collaborative writing projects. Break down the project into manageable tasks and establish deadlines for each phase of the writing process. Regular check-ins and progress updates help keep the project on track and ensure that everyone is working towards common goals.

Resolving Conflicts and Creative Differences

Conflicts and creative differences are inevitable in collaborative writing projects, but they can be managed effectively with open communication and a willingness to compromise. Encourage honest dialogue and active listening among team members to address issues as they arise. Focus on finding common ground and reaching a consensus to move the project forward.

Celebrating Achievements and Milestones

Celebrate achievements and milestones throughout the collaborative writing process to foster a sense of camaraderie and motivation among team members. Recognize individual contributions and milestones reached, whether it’s completing a draft, receiving positive feedback, or achieving a publication milestone. Celebrating successes reinforces a positive team dynamic and encourages continued collaboration.

Embracing Flexibility and Adaptability

Flexibility and adaptability are essential qualities for navigating the dynamic nature of collaborative writing projects. Be open to feedback, revisions, and unexpected changes that may arise during the writing process. Embrace the opportunity to refine the project based on those insights and evolving ideas developed together.

Reflection and Continuous Improvement

After completing a project, take time to reflect on the experience and identify areas for improvement. Ask for feedback from team members to find out what worked well and what could be changed for future collaborations. Continuous reflection and learning contribute to the growth and refinement of not only your writing skills but also life in general.

Collaborative writing projects offer many opportunities for writers to leverage their collective talents and creativity. By understanding the pros and cons, drawing inspiration from successful examples, and implementing practical tips for success, writers can embark on these endeavors with confidence and enthusiasm.

Have you ever participated in a collaborative writing project, and if so, what strategies or techniques did you find most effective in ensuring its success?

About The Author

Thom Francis

Related posts.

Unlocking Creativity: Using Photographs as Writing Prompts

Five Practical Ways to Cultivate Your Writing Life

Editing Tips for Conscious and Inclusive Language and Storytelling

Alternative Narrative Structures in Memoir

The Hudson Valley Writers Guild supports the efforts of writers in all genres by sponsoring readings, workshops, and contests and providing a number of valuable resources for the entire literary community.

- Non Fiction

- Next Up to The Mic

- Writers Read Live!

- Sanctuary Radio

- Writers Forum

- Literary Events Calendar

- Calls For Submissions

HVWG Newsletter

Keep in touch.

- 518-482-2639

- 265 River Street, Troy, NY 12180

Start typing and press enter to search

ELA Matters

Engaging both middle school and high school learners!

5 Collaborative Writing Activities to Boost Writing Confidence

They say two heads are better than one, so it stands to reason that students working in pairs or groups can yield greater learning outcomes than individual performance tasks. Learning from our peers is usually more memorable and impactful than traditional lecture style teaching, even for us as adults!