By Audience

- Therapist Toolbox

- Teacher Toolbox

- Parent Toolbox

- Explore All

By Category

- Organization

- Impulse Control

- When Executive Function Skills Impair Handwriting

- Executive Functioning in School

- Executive Functioning Skills- Teach Planning and Prioritization

- Adults With Executive Function Disorder

- How to Teach Foresight

- Bilateral Coordination

- Hand Strengthening Activities

- What is Finger Isolation?

- Occupational Therapy at Home

- Fine Motor Skills Needed at School

- What are Fine Motor Skills

- Fine Motor Activities to Improve Open Thumb Web Space

- Indoor Toddler Activities

- Outdoor Play

- Self-Dressing

- Best Shoe Tying Tips

- Potty Training

- Cooking With Kids

- Scissor Skills

- Line Awareness

- Spatial Awareness

- Size Awareness

- Pencil Control

- Pencil Grasp

- Letter Formation

- Proprioception

- How to Create a Sensory Diet

- Visual Perception

- Eye-Hand Coordination

- How Vision Problems Affect Learning

- Vision Activities for Kids

- What is Visual Attention?

- Activities to Improve Smooth Visual Pursuits

- What is Visual Scanning

- Classroom Accommodations for Visual Impairments

Fine Motor Leaft Craft

- Free Resources

- Members Club

Executive Functioning Skills

Executive function, so, what exactly is executive function, explore popular topics.

What do all these words mean?

Executive Functioning Skills guide everything we do. From making decisions, to staying on track with an activity, to planning and prioritizing a task . The ability to make a decision, plan it out, and act on it without being distracted is what allows us to accomplish the most mundane of tasks to the more complicated and multi-step actions. Children with executive functioning issues will suffer in a multitude of ways. Some kids have many deficits in EF and others fall behind in several or all areas. Everyone needs to develop and build executive functions as they grow. Functional adults may still be struggling with aspects of executive functioning skills. Executive dysfunction can interfere with independence and the ability to perform activities. The cognitive skills are an interconnected web of processing that allows for self-regulation, planning, organization, and memory.

As a related resource, try these self-reflection activities for kids .

What are executive functioning Skills?

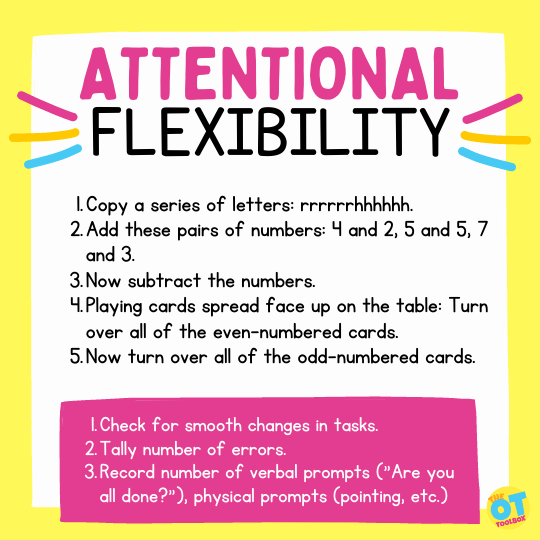

Executive functioning skill names, cognitive flexibility.

- Check for smooth changes in tasks.

- Tally number of errors.

- Record number of verbal prompts (“Are you all done?”), physical prompts (pointing, etc.)

Executive function and handwriting

How to build executive function skills:

Tools to grow executive functioning skills.

We have many resources and tools to grow executive functioning skills in functional tasks and learning. Explore the executive functioning blog posts below.

Some tools to support and grow executive functioning skills involve breaking down tasks into the components of executive functioning. By that I mean that you’ll want to focus on the specific executive functions that allow us to pay attention to instructions, plan out a task, and then recall how and why we are doing things, and then maintain the impulse control in order to sustain use of our existing skills in completing the task.

I love to provide students with specific tools to grow and nurture each of these executive functions.

We have resources and activities for the different executive functioning skills on different blog posts on this site, but one way to grow these areas is by focusing on one task and then developing tools for each aspect of that task.

For example, take on common struggle: writing down homework assignments and completing them when they are due, while managing the organization needed for the materials. You can try other tips for organizing a backpack that can help, too.

This is a common challenge for students with executive functioning that is below that of their peers. We know that executive functioning skills don’t fully develop until the early 30’s , so asking a teenager to utilize mature executive functioning skills requires tricks and practice. We can make it part of their routine rather than asking them to complete tasks on a whim with mature executive functioning.

Let’s look at the tools we can use to grow the skills needed for our homework example.

The student needs to write down their homework assignment during a busy classroom, possibly when there is a lot of other commotion going on. It seems like this is more of a challenge than it used to be because of the deceives like tablets, laptops that students use now, versus the old-fashioned paper planners that they could quickly write on and then tuck into their backpacks. Now, jotting down an assignment means pulling up a notes app or opening another program on the device. It’s not as easy for students to quickly jot down page numbers for their math homework.

We see students that believe they can remember the homework or think they can write it down when they open their laptop in their next class, but that just doesn’t happen. The attention and the distraction of this age means that the assignment is gone form their minds by the time they get that device opened back up again.

Tools to grow these skills include: using a post it note to quickly write down the assignment. This can support impulse control, attention, working memory, and organization skills.

Next, we have the home aspect. The student might not bring home all of the materials needed for the assignment. They might be left in the locker or lost somewhere along the way from school to home. We might see missing books, missing worksheets a forgotten device, or other materials that are missing or left at school. This involves organization skills, working memory, attention to detail, and impulse control.

Tools to grow this aspect might be using a check in before the student leaves school for the day. They might have a check in process in their locker in the way of a check list. You can practice this by assigning your student “homework” where they need to take home a piece of paper and bring it back to school the next day. Continue with this practice for a week so that they process of checking to make sure they have that slip of paper both in the morning and in the afternoon becomes part of the routine.

Be sure to check out all of our strategies to grow executive functioning skills by clicking through the blog posts on executive functioning skills…

Top Executive Function Blog Posts

- Executive Functioning Skills , Free Resources

Tools to Stop to Think

- Attention , Executive Functioning Skills , Occupational Therapy Activities , Sensory

Self-Reflection Activities

- Executive Functioning Skills , Free Resources , Occupational Therapy

Drawing Mind Maps

- Executive Functioning Skills , Functional Skills , Occupational Therapy Activities

Executive Function Coaching

- Executive Functioning Skills , Free Resources , Mental Health , Occupational Therapy

The Power of Yet

Breaking Down Goals

- Attention , Executive Functioning Skills , Occupational Therapy

Executive Function Tests

- Attention , Development , Executive Functioning Skills , Occupational Therapy

Spring Activities for Executive Functioning

Executive function in products.

Self Regulation Toolkit

How-to Life Sequences Made Easy – Cut & Paste

Fix the Mistakes-Fun Themes Bundle

Task Completion Cards (5 Theme Bundle)

Free Executive Function Resources

Fall Leaf Auditory Processing Activities

Pumpkin Sensory Activities

Pumpkin Deep Breathing Exercise for Halloween Mindfulness

Learning with Dyed Alphabet Pasta

Explore more tools, fine motor skills, functioning skills, handwriting, quick links, sign up for the ot toolbox newsletter.

Get the latest tools and resources sent right to your inbox!

Get Connected

- Want to read the website AD-FREE?

- Want to access all of our downloads in one place?

- Want done for you therapy tools and materials

Join The OT Toolbox Member’s Club!

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

A Problem-Based Learning Curriculum for Occupational Therapy Education

1995, American Journal of Occupational Therapy

To prepare practitioners and researchers who are well equipped to deal with the inevitable myriad changes in health care and in society coming the 21st century, a new focus is needed in occupational therapy education. In addition to proficiency in clinical skills and technical knowledge, occupational therapy graduates will need outcome competencies underlying the skills of critical reflection. In this article, the author presents (a) the rationale for the need for change in occupational therapy education, (b) key concepts of clinical reasoning and critical reflection pertaining to the outcome such change in occupational therapy education should address, (c) problem-based learning as a process and educational method to prepare occupational therapists in these competencies, and (d) the experience of the Program in Occupational Therapy at Shenandoah University in Winchester, Virginia, in implementing a problem-based learning curriculum.

Related Papers

The American Journal of Occupational Therapy

Charlotte Royeen

Objectives. Problem-based learning (PBL) is increasingly being used within health care professional educational programs to develop critical thinking skills via a learner-centered approach. However, few studies have evaluated the effect of participation in a PBL-centered curriculum on occupational therapy knowledge and skill development over time from the perspective of the students involved. This study examined student evaluations of the first three class cohorts participating in a PBL-based curriculum. Method. A participatory action design study involving qualitative, student-led focus groups was conducted with 154 students across 2 years of the education program. Fourteen focus groups were audiotaped, and those audiotapes were transcribed by an outside expert, followed by two levels of analysis by program faculty members and a member check by student participants. Results. Themes that emerged from the data analysis related to (a) defining elements of PBL, (b) the role of students...

American Journal of Occupational Therapy

Kerryellen G Vroman

Donna Wooster

Steven Whitcombe

The British Journal of Occupational Therapy

Deborah Davys

Critical thinking is a component of occupational therapy education that is often intertwined with professional reasoning, even though it is a distinct construct. While other professions have focused on describing and studying the disciplinary-specific importance of critical thinking, the small body of literature in occupational therapy education on critical thinking has not been systematically analyzed. Therefore, a systematic mapping review was conducted to examine, describe, and map existing scholarly work about critical thinking in occupational therapy education. Inclusion/exclusion criteria were set, database searches conducted, and 63 articles identified that met criteria for full review based on their abstracts. Thirty-five articles were excluded during full review, leaving 28 articles for analysis and coding using a data extraction tool. Eleven articles (39%) had a primary focus of critical thinking, and of those 11 articles, the majority were about instructional methods. Qua...

Journal of Occupational Therapy Education

Brenda Coppard

The American journal of occupational therapy : official publication of the American Occupational Therapy Association

Linda De Wet

Within occupational therapy education, there has been increased attention to curricula and courses that emphasize problem solving, clinical reasoning, and synthesis of information across traditional discipline-specific boundaries. This article describes the development, implementation, and outcomes of a problem-based learning course entitled Selected Cases in Occupational Therapy. The course was designed to help students to integrate the various elements of a specific occupational therapy curriculum and to enhance their abilities to respond to an ever-changing health care environment. An evaluation of the course by the first 11 students who completed it revealed both strengths and weaknesses. Students responded that the course enhanced their professional behavior, including interpersonal communication skills, team work, and follow-through with professional responsibilities; helped them to integrate the various elements of the total occupational therapy academic program; enhanced the...

Date Presented 4/21/2018 This study provides relevant information about what instructional methods faculty use most often and what they find valuable to successfully teach clinical reasoning. Future work needs to identify specific methods that are most effective to build the cadre of contemporary scholarship of teaching and learning for occupational therapy. Primary Author and Speaker: Whitney Henderson Additional Authors and Speakers: Brenda Coppard Contributing Authors: Youngue Qi

The Open Journal of Occupational Therapy

LaRonda Lockhart-Keene

Loading Preview

Sorry, preview is currently unavailable. You can download the paper by clicking the button above.

RELATED PAPERS

Occupational Therapy in Health Care

Moses Ikiugu

Journal of the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning

Helene Larin

Occupational Therapy International

Charles Juwah

Adriana Reyes Torres

British Journal of Occupational Therapy

South African Journal of Occupational Therapy

Lizelle Jacobs

The Internet Journal of Allied Health Sciences & Practice

Bill O'Dell

Christine Kroll

Hiba Zafran

Tara Cusack , Sinead McMahon

South African Journal of Physiotherapy

carina eksteen

Iranian Rehabilitation Journal (IRJ)

Steven Taff

Helen Madill

Wyona M Freysteinson, PhD, MN

Iranian Rehabilitation Journal

narges shafaroodi

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

Copyright © 2024 OccupationalTherapy.com - All Rights Reserved

Cognitive Interventions In The Home: A Practical Approach For OT Professionals

Krista covell-pierson, otr/l, bcb-pmd.

- Acute Care, Community and Home Health

- Cognition and Executive Function

- Gerontology and Aging

To earn CEUs for this article, become a member.

unlimit ed ceu access | $129/year

Editor's note: This text-based course is a transcript of the webinar, Cognitive Interventions In The Home: A Practical Approach For OT Professionals, presented by Krista Covell-Pierson, OTR/L, BCB-PMD.

Learning Outcomes

- Identify four ways an OT can integrate cognition into a treatment plan.

- List four assessments for cognition that are appropriate to use in the home setting.

- Recognize four types of memory impairments and distinguish between dementia and delirium.

Introduction

Today, we will delve into cognitive interventions in the home—a practical approach tailored for occupational therapy professionals. Our profession holds significant potential to profoundly impact individuals' lives, although, at times, it may seem challenging to grasp the full scope of our role. However, during our discussion, I aim to provide you with valuable insights that you can readily integrate into your practice.

I reside in Colorado and am the proprietor of Covell Care and Rehab, a private practice where we serve a diverse patient population. The majority of our patients contend with various cognitive impairments, an aspect of care that I find particularly rewarding. Our work extends to individuals coping with conditions such as dementia, brain injuries, mild cognitive impairment, and other cognitive-related issues.

In my 22-year career as an occupational therapist, I have come to believe that, as OTs, we can enhance our approach to addressing cognition. As we embark on a deeper exploration during this hour, I encourage you to consider how you can better assist patients facing cognitive challenges.

You might wonder why this topic is of utmost importance. Given your roles as OT practitioners, you likely recognize its significance and inherent value. However, I intend to equip you with the language and rationale to explain its importance to our patients, their families, our colleagues, supervisors, and third-party payers. Effective communication, both verbally and in written documentation, is crucial. Therefore, we will touch on various aspects of this skill.

Why Is This Important?

When defining cognition, it's essential to appreciate the multifaceted nature of the concept. Several skills interplay when we consider cognition. One definition I find particularly insightful is derived from the Dementias Platform in the United Kingdom, and it reads as follows: "Cognition is a term for the mental processes that take place in the brain, such as thinking, attention, language, learning, memory, and perception." The areas are listed below.

- Skill generalization and combination

- Functional cognition

We also know as OTs that these processes are not discrete abilities, like this gentleman in his raft (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Man in a raft in the water.

Cognitive processes are intricately interconnected, akin to floating on a raft. Our objective is to equip our patients with diverse skills that harmoniously converge, enabling them to become proficient, functioning individuals, regardless of age. Therefore, when we clarify our purpose, we must emphasize that we are not solely focused on enhancing learning or memory.

Instead, our aim is for these improvements to translate into a higher quality of life. Effective communication plays a pivotal role here. While we often discuss these individual facets, it is equally essential to view the bigger picture and recognize the invaluable role that occupational therapists bring to the table.

Patients may have previously undergone neuropsychological evaluations, cognitive screenings with physicians, or worked with speech-language pathologists. Nevertheless, we can step in and comprehensively assess the array of skills listed here, aligning them with our patients' life goals. Thus, our presence within the cognitive team is highly practical.

The research underscores that when patients receive occupational therapy tailored to address functional cognition, it significantly reduces their risk of hospitalization or re-hospitalization. This outcome is compelling and resonates with various stakeholders, including third-party payers, administrators, supervisors, and, most importantly, our patients and their families. Keeping our loved ones out of the hospital is a shared priority for all.

Cognition Impacts ADLs

- Home management

- Financial management

- Community involvement

Moving beyond discussing cognition, let's look at how cognition profoundly influences our daily activities, our routines, and, ultimately, our quality of life. While it's not groundbreaking for us to acknowledge that cognitive skills impact daily living, what sets us apart is our ability to effectively communicate how we can enhance these activities.

The tasks I've outlined here serve as simple examples that can be seamlessly integrated into our therapeutic goals to demonstrate tangible improvements in function through enhanced cognition.

Is it truly impactful if someone can recall five random words when prompted? Not really, because it lacks functionality. What genuinely matters is if someone can remember five essential steps in operating their washing machine, enabling them to independently and efficiently do their laundry. The real victory lies in achieving practical, meaningful outcomes where individuals no longer require constant caregiver assistance.

Our approach involves identifying these personally significant tasks, aligning them with the cognitive processes that require improvement, and then guiding our patients through the journey of mastering these tasks. This approach benefits our patients and facilitates clearer communication in our notes and collaboration with our peers, which we will delve into further.

ADLs at Home

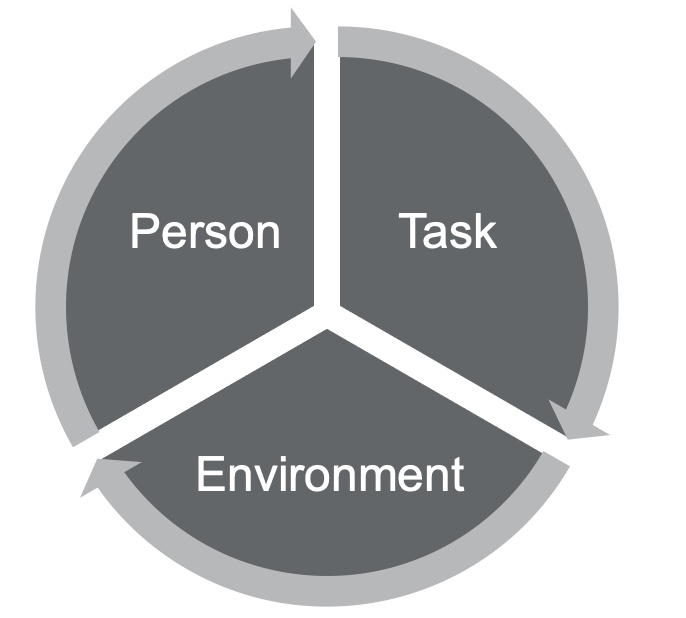

Figure 2 shows an infographic showing how the person, task, and environment are interconnected.

Figure 2. Person-task-environment diagram.

I frequently use diagrams like the one shown here because they align with the person-environment model, which emphasizes a holistic approach to assessing occupational performance. When working with our patients, conducting a comprehensive assessment is crucial. This assessment should encompass an examination of their skills, deficits, desires, mental and physical health, and medical needs. The goal is to develop a personal profile, recognizing that all these facets significantly impact an individual's functional cognition.

Next, we focus on identifying meaningful tasks, a process in which both the patient and their family members or caregivers play a vital role. Prioritizing tasks that resonate with the patient's motivations is imperative because intrinsic motivation is pivotal, especially when dealing with cognitive challenges. If a task isn't personally meaningful, it can be challenging to rationalize its importance, particularly for those already facing cognitive difficulties.

Additionally, it's crucial to assess how the patient perceives their skillset and compare it with our observations. Often, individuals with cognitive difficulties may overestimate their abilities. Input from loved ones and caregivers is equally valuable, as their perceptions might differ from our assessments.

A particularly rewarding aspect of our work is when we can engage with patients in their homes. This intimate setting allows us to witness their daily lives, which can be both dynamic and enlightening. Unlike a static therapy gym, homes vary, offering a unique and enjoyable challenge.

Here are two real-life examples that illustrate the diversity of environments we encounter. I had a patient who was living in a mother-in-law-type apartment above the garage. She had a huge family with members coming in and out all the time. It was distracting even for me during treatment, so I knew it was distracting for her, especially living with memory loss and cognitive fatigue related to chemotherapy treatments. I also had a patient who lived two minutes away in low-income housing. She had very limited resources and no social support system in town. Her family lived out of state, and she had no friends. She was dealing with crippling anxiety, memory loss, and decreased problem-solving skills related to years of alcohol and drug abuse. These are different people in two different environments. I can start by going into the home and looking for ideas and answers based on those environments. I can see what's meaningful to them. For example, I might see that they have a smartphone or notes next to the phone. I might see that they have their own cookbooks and like to cook. I can start using those things to make the tasks more meaningful when I'm in the environment. Working in the home setting requires flexibility and adaptability, but it's where the magic truly happens. Utilizing personal items like photographs, meaningful objects, or even the layout of their home can enhance memory recall and yield better results. Whether you're considering working in a home setting or already doing so, it's a personally rewarding endeavor. You'll find ample opportunities to connect with patients and significantly impact their lives.

Lastly, the American Occupational Therapy Association (AOTA) advocates for our role in the cognitive space. They define us as experts in measuring functional cognition, encompassing everyday task performance. Recognizing subtle cognitive impairments is crucial, as they often go untreated but can significantly impact an individual's functioning. As OTs, we treat cognitive impairments because they have the potential to compromise the safety and long-term well-being of our patients. By familiarizing yourself with AOTA's resources and language, you can strengthen your documentation and advocacy efforts, ensuring that OTs continue to play a vital role in addressing cognition and improving the lives of our patients. For additional information, refer to AOTA's resources on cognitive intervention.

Integrating Cognition Into a Treatment Plan

- Starts with chart review

- Education to patients/families of brain function as it relates to ADL at home

- Identification of areas of concern at home

- Administration of cognitive assessments at home

The integration of cognition into a treatment plan is a pivotal aspect of our occupational therapy practice. It's a process that begins with a thorough chart review, a step that some therapists may sometimes overlook in the midst of their busy daily routines. However, I want to emphasize the significance of this step. Neglecting it can potentially hinder the outcomes of your treatment plan.

A strong understanding of neuroanatomy is essential when reviewing medical records, especially in cases involving cognitive challenges. While most of us studied neuroanatomy in college, refreshing your knowledge may be a good idea, especially if it's been a while. Although we won't go into an in-depth neuroanatomy lesson, I'll touch on some key points to jog your memory. This knowledge will serve as a foundation for aligning the information you gather from chart reviews with your patient assessments. It also enables you to educate your patients, their families, and caregivers about what's happening in the brain.

You don't need to become a neurologist, but having a strategic understanding of the neurological aspects can significantly benefit your approach. For example, consider a patient who exhibits inappropriate behavior, like a previous client of mine. He would go out into public and act inappropriately, especially towards some of the women working at a local coffee shop. This gentleman was quite large, standing at 6'7", and that alone could be intimidating. Some of his inappropriate behaviors required occupational therapy intervention, but I also understood that trauma in his brain might have contributed to these behaviors. It's important to approach your work with a bit of strategy and understanding about what's going on neurologically. Knowing how specific areas of the brain might be contributing to certain behaviors can be incredibly valuable. It's all about bringing this understanding back to functional cognition.

If you find yourself without access to detailed medical records or relevant neurology reports, especially when dealing with a patient diagnosed with dementia but lacking associated medical documentation, consider requesting these records or making referrals to specialists. In some areas, neurology departments may have lengthy waitlists, so it's wise to get the process started early to ensure your patients receive timely support for their cognitive challenges.

Let's briefly review the critical regions of the brain. The frontal lobe, often referred to as our "mission control," plays a central role in cognitive functioning. It influences emotional expression, problem-solving, memory, judgment, and even sexual behaviors. Understanding this region can help us connect cognitive deficits with functional challenges. The temporal lobes are responsible for visual, olfactory, and auditory processing. These processes are vital for healthy thinking, emotional responses, and communication. The occipital lobes act as our visual hub, enabling us to interpret color, shapes, and object locations. In contrast, the insular cortex facilitates sensory processing, emotional expression, and some motor functions. The parietal lobe allows us to make sense of sensory experiences in the world, ensuring we can understand our surroundings and adapt our actions accordingly. There are also subcortical structures deep within the brain, including the diencephalon, pituitary gland, limbic structures, and basal ganglia. These structures can be likened to a "switchboard" or "mission control," simplifying complex medical concepts for our patients.

When educating patients and families about brain function in relation to activities of daily living (ADLs), consider using relatable examples and analogies. For instance, you could compare the brain to an avocado. This can make complex information more accessible and engaging.

Once you've conducted a chart review and gathered relevant information, it's an excellent time to begin educating your patients and their families about brain function and its implications for daily life. This step is crucial in building a strong foundation for your treatment plan. It helps your patients and their families understand the reasoning behind your interventions, making your approach transparent and empowering.

For instance, I once worked with an aide in an assisted living facility who had been caring for residents with different diagnoses for years but was unaware of the differences between these conditions and their effects on motor planning, cognition, and progression. Educating her about these differences transformed her perspective and improved her caregiving. Incorporate this education into your treatment plans and goals, and consider including caregiver-based goals when appropriate. By fostering understanding and collaboration, you can ensure that your interventions are effective and well-received.

Identifying areas of concern in the patient's home is the next crucial step. During evaluations, patients and their families may provide a wealth of information, but it's essential to sift through this data and prioritize. Given the pervasive influence of cognitive deficits, the list of concerns can be extensive. Start by identifying safety concerns, as these should always be addressed first.

Subsequently, focus on two to three areas that are particularly important to the patient and their family. This targeted approach allows for more manageable and effective interventions. Keep in mind that cognitive improvements in one area may have a positive ripple effect on other ADLs.

Treatment Planning Within the Home Environment

- Interpretation of results/Giving results meaning

- Identification of areas to work on

- Determining Functional Cognition!

Giving meaning to assessment scores is crucial. It's not enough to provide a number; we need to translate those scores into practical implications for the individual's daily life. This helps us pinpoint areas that require intervention and tailor our treatment plans to address specific functional challenges related to cognitive deficits.

Functional Cognition

- The cognitive ability to perform daily life tasks is conceptualized as incorporating metacognition, executive function, other domains of cognitive functioning, performance skills (e.g., motor skills that support action), and performance patterns.

- Making Functional Cognition a Professional Priority | The American Journal of Occupational Therapy | American Occupational Therapy Association (aota.org)

- Functional cognition should ONLY be evaluated in actual task performance. Home is ideal!

Functional cognition is a critical aspect of occupational therapy practice, and its definition has evolved over the years to provide a more comprehensive understanding of its role in daily life. The current definition emphasizes the integration of cognitive skills for performing activities of daily living (ADLs) and includes skills, strategies, and psychosocial elements. This updated definition acknowledges the impact of the environment, mental health, and physical health on an individual's cognitive abilities, making it a more robust framework for OTs to assess and address functional cognition in their clients.

Consideration for Functional Cognitive Treatment Planning

- Person focused

- Environment

- Emotional health

- Neurological and biological factors

In the realm of functional cognitive treatment planning, our focus naturally gravitates towards a person-centered approach. This inclination is hardly surprising, given that we, as occupational therapists, excel at catering to individual needs and aspirations. However, we may not always consider the profound impact of culture in our practice.

Culture, encompassing one's upbringing and early learning experiences, profoundly influences how individuals engage with their surroundings, perceive others, absorb and retain information, and form judgments. It's essential to recognize that these cultural nuances can vary significantly, especially when working with individuals from diverse backgrounds or those whose cultures we may not be intimately familiar with. A thoughtful exploration, whether through conversations with the patient or their family or through independent research, can unearth vital insights that should not be overlooked.

Cultural awareness aside, we must also cast our gaze upon the environmental factors that bear upon an individual's performance. Consider the case of a patient dwelling in a mother-in-law apartment, where chaos perpetually reigns. Amidst the constant juggling of pet care, from dogs to kittens and birthing cats, alongside the responsibility of caring for a boyfriend with brittle diabetes, distraction becomes a relentless companion, exhausting in its own right. Here, our task is to discern the nuances of such environments and strategize on managing their impact.

Emotional well-being is another facet deserving of our attention. A poignant quote aptly reminds us that "emotional function and cognitive function aren't unrelated to each other; they're completely intertwined." This truth is self-evident to anyone who has traversed the depths of grief, battled the shadows of depression, or grappled with the relentless grip of anxiety. When we encounter a patient navigating such emotional storms, we must acknowledge that their cognitive abilities may bear the brunt of these turbulent waters. A recently bereaved patient struggling to find equilibrium may exhibit signs of forgetfulness or cognitive struggle directly linked to their emotional state.

Lastly, we must not overlook the neurological and biological dimensions. Employing tools like brain scans and neuropsychological evaluations, we gain invaluable insights into the mind's inner workings. This knowledge becomes a cornerstone for crafting precise treatment plans and, where necessary, advocating for specialized care. Consider this parallel: just as you wouldn't prescribe the same medication for every patient with chest pain, so too should we be cautious of hastily offering psychiatric drugs without a comprehensive understanding of what's transpiring within the patient's brain. As occupational therapists, recognizing the significance of these assessments, our duty extends to educating our patients and championing their access to the expertise that can provide tailored solutions for their unique cognitive challenges.

Assessments to Use at Home

- Confusion Assessment Method: to identify patients with delirium: The_Confusion_Assessment_Method.pdf (va.gov)

- The Brief Interview for Mental Health Status

- Performance Assessment of Self-Care Skills

- Executive Function Performance Test

Let's now delve into the assessments that can be incorporated into our practice. Although some of these assessments may initially appear unconventional for occupational therapists, they offer valuable insights and are integral to comprehensive care.

The Confusion Assessment Method (CAM) and Brief Interview for Mental Health Status (BIMS) do not inherently align with traditional OT practices, but both have gained approval from Medicare for assessing cognition. CAM, for instance, aids in identifying delirium in patients. Delirium, which can range from subtle to severe, may not always be readily apparent. By conducting CAM, we ensure that cognitive assessments are appropriate, as addressing cognition when delirium is present can be counterproductive. Even if you are confident that delirium isn't a factor, utilizing CAM demonstrates a thorough approach, which can be crucial for third-party payer compliance. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) has integrated CAM into post-acute care assessments, which might already be a part of your healthcare team's protocol.

On the other hand, BIMS, another CMS-approved assessment, serves as a valuable tool for neuropsychological screening. For example, if you encounter a patient grappling with profound grief and depression, the BIMS can shed light on their mental state. It's essential to address mental health concerns before diving into cognitive evaluations. Collaborating with your healthcare team to determine who administers these assessments can streamline the process. Alternatively, you can administer them yourself; they are efficient and quick, providing a solid foundation for cognitive assessments.

Let's explore assessments that align more closely with traditional occupational therapy practices. The Performance Assessment of Self-Care Skills is a reliable, client-centered, performance-based assessment designed to measure occupational performance in daily life tasks. It can be effectively employed with adolescents, adults, and older adults, even in home settings. Comprising 26 core tasks, including mobility, basic ADLs, IADLs with a physical focus, and crucially, 14 IADL tasks related to cognition, the PASS provides a holistic view of a patient's abilities and how they navigate various tasks.

The Executive Function Performance Test examines a patient's capabilities in tasks like cooking, phone use, medication management, and bill payment within their home environment. It offers valuable insights into a patient's functional abilities and serves as an educational tool for families. Additionally, it's accessible as a free download, providing convenient access to a useful assessment tool.

Despite their initial differences from conventional OT practices, these assessments play an indispensable role in ensuring comprehensive care and tailored interventions for our patients.

Additional Assessments to Use at Home

- Fitness to Drive Screening Measure: Web-based to identify at-risk drivers

- Loewenstein Occupational Therapy Cognitive Assessment (LOTCA): Cognitive and visual perception skills in older adults are assessed

- Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE): Measures orientation, recall, short-term memory, calculation, language, and constructability

- Cognitive-Performance Test (CPT): Explains and predicts capacity to function in various contexts and guide intervention plans

- Cognistat: Rapid testing for delirium, MCI, and dementia (can be used with teens to adults)

- Trail Making Tests A and B

Incorporating assessments into our home-based occupational therapy practice is essential for providing comprehensive care. One critical area that demands our attention is assessing a patient's fitness to drive. If you work in the community, be it outpatient, home care, or mobile outpatient services, addressing a patient's ability to drive is paramount, especially when cognitive issues are at play. However, determining whether a patient should drive requires specific skills and training. If you lack this expertise, it's crucial to connect with a Certified Driving Rehab Specialist (CDRS), often an occupational therapist or physical therapist with extensive training in driving assessments. Collaborating with CDRSs is vital, as it directly relates to public health, safety, and community well-being. The tragic example of a wrong-way driver causing a fatal accident highlights the significance of addressing driving concerns diligently.

Here are some assessments that you can integrate into your practice. The Loewenstein Occupational Therapy Cognitive Assessment, previously known as the LOTCA, assesses cognitive and visual perception skills. It aids in identifying various levels of cognitive difficulties and provides insights into a patient's learning potential and thinking strategies. This information significantly influences our treatment planning and intervention selection. Additionally, the LOTCA offers different versions tailored to different age groups, enhancing its versatility.

Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) assesses orientation, recall, short-term memory, calculation, language, and constructive ability. While it's commonly administered in physician's offices, you can also use it in your home-based practice. There's a similar tool called the SLUMS (Saint Louis University Mental Screening), which is a free assessment option.

The Cognitive-Performance Test (CPT) is a performance-based assessment that explains and predicts a patient's capacity to function in various contexts. It employs the Allen Cognitive Levels for rating patients, which can be shared with their families to help them understand cognitive challenges better.

Although typically used in inpatient psychiatric facilities, the Cognistat can be adapted for home-based assessments. It's a rapid test that differentiates between delirium, mild cognitive impairment, and dementia and can be applied across various age groups.

The Trail Making Tests A and B evaluate general cognitive function, including working memory, visual processing, visual-spatial skills, selective and divided attention, processing speed, and psychomotor coordination. Trail Making Test B, in particular, has been linked to poor driving performance. If a patient performs poorly on this test and intends to drive, it's advisable to refer them to a CDRS or consider pursuing CDRS certification.

These assessments, though diverse in their applications and availability, expand our toolkit for home-based occupational therapy. Some may require purchase, while others can be downloaded. Discuss the possibility of integrating these assessments into your practice with your employer to enhance the quality of care you provide during home visits.

Clinical Observations

- Errors in math

- Frustration from the patient

- Distractibility

- Difficulty focusing

- Repeated phrases

- Requires redirection

- Unable to locate items

- Impulsivity

- Reduced reciprocity

- Reduced problem-solving skills

- Delayed or absent recall

- Changes in perception

- Poor insight

- Changes in personality

- Irritability

- Safety concerns

- Increased fatigue

- Decreased organization

It's essential to emphasize the value of your clinical observations and activity analyses in your documentation. These observations, rooted in your skilled assessment and honed through clinical experience, provide crucial insights into a patient's cognitive abilities and challenges.

For instance, consider an activity as straightforward as making a peanut butter and jelly sandwich, reminiscent of college days. While occasional difficulties in locating items or lapses in focus are common and may not necessarily indicate a cognitive issue, persistent patterns of such challenges warrant attention. If you consistently encounter these issues or receive complaints from families, it's an indication that cognitive assessment and intervention may be necessary, even if your initial focus was on a different aspect of care. Your ability to recognize these signs and adapt your approach is a testament to your clinical expertise and dedication to comprehensive patient care.

Home Strategies

- Visual cues

- Automatic timers

- Lighting alternatives

- DME for fall prevention

- Reduced clutter

- Alarm/alert systems

- Phones and computers

- Routine modifications

- Mental health support/activities

- Paper calendars

- Timers for time modulation

- Caregiver education

- Driving alternatives

- Dementia education and training

- Emergency preparedness

- “Just right challenge” tasks

- Safety training

- Stress management

Working in a patient's home setting can be an incredibly rewarding experience for occupational therapists. It provides a unique opportunity to tap into our innate creativity and adaptability as professionals. Here are some strategies and interventions that can be seamlessly integrated into home-based care:

Utilizing visual cues can be highly effective. For example, consider a patient who frequently snacks on unhealthy foods. To address this issue, you can clear a designated place on the kitchen counter, place a placemat there, and instruct caregivers to set out specific healthier snacks on the placemat. This visual cue prompts the patient to choose healthier options, promoting improved dietary habits.

While automatic timers can be useful, it's crucial that the patient understands their purpose. Many patients may become confused when timers go off without clear instructions. Therefore, ensuring the patient comprehends the intended use of timers and how to respond when they activate is essential.

In cases where certain areas lack adequate illumination, such as bathrooms, adjusting the lighting can reduce patient distress and confusion, particularly for those with cognitive impairments. Ensuring a well-lit environment can enhance their comfort and safety.

Managing a patient's energy levels throughout the day is vital. Cognitive issues, from dementia to brain injuries, can lead to increased fatigue. Therefore, helping patients modulate their activity levels and prevent excessive exhaustion is integral to care planning.

Smartphones, computers, and phones can be valuable tools for patients, provided they have a basic understanding of how to use them. Caregiver education in this regard can empower patients to leverage technology for various aspects of daily life.

Stress can significantly worsen cognitive function. Implementing stress management techniques and strategies can be beneficial for patients. This may include relaxation exercises, mindfulness practices, or simple stress-reduction activities.

Although not listed, exercise plays a crucial role in maintaining and improving cognitive function. Incorporating physical activity, even in modified forms, can engage the cerebellum and contribute to clearer thinking and improved cognitive abilities.

In summary, home-based occupational therapy allows us to be creative and tailor interventions to suit each patient's unique environment and needs. Utilizing visual cues, appropriate technology, and effective energy management can enhance our patients' quality of life and well-being while addressing cognitive challenges.

Adding Goals to Treatment Plans

- Client-based

- Assist level

When formulating goals for cognitive interventions, it's beneficial to employ the COAST framework, emphasizing client-centered, occupation-based, specific, and time-bound goals. These objectives should align with the principles of functional cognition and measure improvements in functional outcomes. Here are a few practical examples:

Medication Management Goal

For this goal, the focus is on the patient's ability to manage their medications effectively. In the COAST framework, the goal is tailored to a specific patient, the occupation in focus is the proper administration of daily medications, the patient will employ learned strategies to achieve this goal, the specific objective is for the patient to take all five of their daily medications using the strategies they've acquired, and the patient is expected to reach this goal within a timeframe of three consecutive days within two weeks.

Phone Management Goal

This goal centers around a patient's capability to manage medical appointments through phone calls. In the COAST framework, the goal is customized to meet the specific patient's needs, the occupation in focus is the efficient management of medical appointments via telephone, the patient is encouraged to strive for independent management using their contact list and iPhone, the specific aim is for the patient to make two phone calls with a flawless accuracy rate to manage medical appointments, and the patient is expected to reach this goal within the span of four treatment sessions.

Meal Preparation Goal

In this scenario, the goal is to enhance a patient's ability to prepare a meal, leveraging visual cues. In the COAST framework, the goal is tailored to meet the specific patient's needs, the occupation in focus is the independent preparation of a meal, visual cues will be used to assist the patient in achieving this goal, the specific aim is for the patient to prepare a simple meal while relying on visual cues placed within the kitchen, and the patient is expected to reach this goal within a specified timeframe.

In your documentation, it's crucial to be explicit about the cognitive strategies being employed. This guides the treatment approach and sets clear expectations regarding when the patient is anticipated to succeed. By adhering to the COAST framework and focusing on measurable functional improvements, your cognitive goals will effectively address each patient's unique needs and challenges.

Challenges With Documentation

- EMR useability

- Limited resources online or with employers

- Cognitive goals can require extra time to ensure quality

- Medically necessary required for billing

- Third-party payer authorizations can be more difficult to obtain

Documenting cognitive interventions can pose challenges, particularly within electronic medical records (EMRs) that may not be tailored to occupational therapists. It's not uncommon for EMRs to be more user-friendly for physical therapists, so OTs often need to get creative in how they use these systems. This might involve finding workarounds or advocating for the necessary resources and support from employers to ensure efficient documentation.

Cognitive goals and interventions may also require additional time compared to traditional physical therapy interventions. Justifying this extended timeframe in your treatment recommendations for third-party payers is crucial. Instead of merely stating that you're working on a specific task, such as transfer training, provide a clear rationale for the prolonged duration. For instance, if you're implementing errorless learning techniques or addressing specific cognitive challenges, explain why this additional time is medically necessary for the patient's benefit.

Navigating third-party payment authorizations can be more complex when dealing with cognitive disabilities. Advocacy becomes essential in such cases. You may encounter denials, but don't hesitate to appeal these decisions. Back your appeal with well-structured documentation that educates the payer about the intricacies of cognitive impairments and their impact on the patient's daily life. Emphasize the medical necessity of your interventions. This advocacy can lead to successful outcomes, as exemplified by a case where an appeal secured additional therapy sessions for a patient who ultimately achieved her academic and career goals despite cognitive challenges.

In summary, documenting cognitive interventions may require creativity within EMRs, justification for extended treatment times, and advocacy to secure the necessary authorizations. Through clear and informed documentation, you can effectively convey the medical necessity of your interventions and advocate for the best outcomes for your patients.

Billing for Cognition

- Therapeutic interventions that focus on cognitive function (e.g., attention, memory, reasoning, executive function, problem-solving, and/or pragmatic functioning) and compensatory strategies to manage the performance of an activity (e.g., managing time or schedules, initiating, organizing, and sequencing tasks), direct (one-on-one) patient contact.

- Therapeutic interventions that focus on cognitive function (e.g., attention, memory, reasoning, executive function, problem-solving and/or pragmatic functioning) and compensatory strategies to manage the performance of an activity (e.g., managing time or schedules, initiating, organizing, and sequencing tasks), direct (one-on-one) patient contact.

When it comes to billing for cognitive interventions in occupational therapy, there are specific Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes that you should use. These codes help you accurately document and bill for the services you provide. Here's a breakdown of the relevant codes:

The 97129 code is used for the initial 15 minutes of therapeutic interventions. It's important to note that this code is the same as 97130 in terms of definition. After the initial 15 minutes, you would use the 97130 code for each additional 15-minute increment of therapeutic interventions.

It's crucial to be precise in your documentation and use the language provided in the CPT code descriptions. This helps ensure that your third-party payer understands the nature of the interventions you're providing and approves the billing accordingly. For example, if your therapy session focused on executive function tasks, make sure to explicitly mention that in your documentation. By aligning your documentation with the CPT code definitions, you provide a clear and accurate account of the services you delivered.

To stay organized and informed, consider keeping a handy reference sheet of CPT codes and their definitions, even if you're experienced in your field. This can be a valuable tool for ensuring consistency and accuracy in your billing and documentation practices.

Types of Cognitive Impairments

As we wind down, I want to talk about delirium and dementia for a second.

Delirium Vs. Dementia

Delirium is a condition that, while more commonly associated with acute care settings, can also manifest in the community or during home care visits. As occupational therapists, it's essential to be knowledgeable about delirium because of its potential severity and impact on patients. You might be the primary healthcare provider present in these situations, so identifying delirium becomes crucial.

Delirium is characterized by a sudden onset and is primarily defined by disturbances in attention and awareness. Recognizing delirium is essential because it can lead to significant complications if left unaddressed. Being vigilant and informed about delirium ensures that you can provide appropriate care and support, especially when you're working in home care or outpatient settings where immediate access to medical personnel may not be readily available.

Delirium

- Disturbance in attention and awareness developing acutely tends to fluctuate in severity

- At least one additional disturbance in cognition

- Disturbances are not better explained by dementia

- Disturbances do not occur in the context of a coma

- Evidence of an underlying organic cause

Delirium is a condition characterized by its rapid onset and varying degrees of severity. It's marked by at least one noticeable disturbance in cognition, and it's important to note that this disturbance cannot be attributed to dementia. To help identify delirium quickly, you can utilize the delirium assessment we discussed earlier, which is a fast and efficient tool. If the assessment indicates delirium, seeking immediate medical attention is crucial. While it's rare to encounter someone in a coma during home visits, delirium can manifest in various ways and usually indicates an underlying cause.

Delirium can result from factors such as medication interactions, psychiatric issues, or infections. When you're in a home care setting and observe signs of delirium, it's essential to prioritize the person's safety and well-being by promptly getting them the necessary medical care.

- Significant cognitive decline in one or more cognitive domains.

- Cognitive impairment interferes with ADL.

- Cognitive impairment does not occur exclusively in the context of delirium.

- Cognitive decline is not better explained by other medical or psychiatric conditions.

Dementia is distinguished by significant cognitive decline in one or more cognitive domains, and this decline typically interferes with a person's ability to perform daily activities. It's important to note that delirium and dementia can coexist and are not mutually exclusive conditions. While someone with dementia can experience delirium, the two are distinct.

To diagnose dementia, a physician is required as it involves a comprehensive evaluation beyond the scope of occupational therapy. It's essential to remember that dementia is not a specific disease; rather, it is an umbrella term encompassing various conditions characterized by cognitive decline. Each type of dementia, such as Alzheimer's disease, vascular dementia, or Lewy body dementia, has its unique features and progression patterns. Thus, it's crucial to recognize that not all dementias are the same, and a proper diagnosis is necessary for appropriate management and care planning.

- Vascular dementia

- Dementia with Lewy bodies

- Frontotemporal dementia

- Alzheimer’s

- Mild cognitive impairment

- Encephalopathy

It's crucial to understand that dementia is a broad category encompassing various conditions, each with its unique characteristics and underlying causes. Dementia is not a single disease but rather a term used to describe a range of cognitive impairments. Here are some types of dementia and their distinguishing features:

Vascular dementia results from impaired blood flow to the brain, leading to problems with reasoning, planning, judgment, memory, and other cognitive functions. It is often characterized by cognitive deficits that can vary in severity, as if the brain's function has "holes" due to damage from inadequate blood flow.

Dementia with Lewy bodies is a progressive dementia characterized by a decline in thinking, reasoning, and independent function. Individuals with this type of dementia commonly experience sleep disturbances, visual hallucinations, and movement disorders, such as slow movements, tremors, and rigidity. It is closely related to Parkinson's disease.

Frontotemporal dementia refers to a group of disorders caused by nerve loss in the brain's frontal and temporal lobes. It can manifest as changes in behavior, empathy, judgment, foresight, and language abilities. The specific symptoms may vary depending on the regions of the brain most affected.

Alzheimer's disease is the most common type of dementia, accounting for 60-80% of dementia cases. It is characterized by progressive cognitive decline, including memory loss, language problems, and difficulties with daily activities. Plaques and tangles in the brain are hallmarks of Alzheimer's.

Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI) represents cognitive impairments that are more significant than expected for an individual's age and education level but do not meet the criteria for dementia. While individuals with MCI are at increased risk of developing Alzheimer's disease, not everyone with MCI progresses to dementia.

Encephalopathy refers to a broad term for brain dysfunction. It can lead to a range of cognitive difficulties, including problems with concentration, suicidal thoughts, lethargy, vision issues, swallowing difficulties, seizures, dementia-like behaviors, and more.

Understanding the specific type of dementia is essential for appropriate care and interventions, as each type may require different management strategies and approaches. Additionally, dementia is a complex condition with various underlying causes, and research continues to uncover more about its mechanisms and risk factors.

- Stanley B. Prusiner

- Florence Clark, PhD, OTR/L, FAOTA

As we conclude this session, I'd like to share some valuable insights and practical tips for addressing cognition in occupational therapy. Remember, as occupational therapy practitioners, our role is to help people live life to the fullest, providing practical solutions for success in everyday living. We can assist individuals in maximizing their function, vitality, and productivity, regardless of their cognitive impairments.

It's crucial to advocate for our patients and for the occupational therapy profession's involvement in addressing cognition. Staying informed about neuroanatomy and emerging scientific findings allows us to develop creative and effective treatment plans tailored to each patient's needs, especially when working in a home-based setting.

One essential aspect to remember is that the brain plays a central role in all bodily functions. As Thomas Edison aptly put it, "The chief function of the body is to carry the brain around." Therefore, even when working on physical aspects with our patients, we must recognize the critical importance of cognitive function.

In documenting cognitive deficits influenced by psychosocial aspects during home visits, it's essential to provide specific examples. For instance, if a patient exhibits signs of depression that impact their daily life, you can document the patient's emotional state, any refusal to participate in activities, and your efforts to address their emotional well-being. While we cannot diagnose depression, we can highlight observable signs and symptoms and collaborate with other healthcare professionals for further evaluation and intervention.

Regarding the Allen Cognitive Levels, you can access resources and printouts online. There are books available, such as "Understanding the Allen Cognitive Levels," that can serve as valuable references. These levels can be instrumental in helping patients and their families better understand cognitive impairments and manage associated behaviors effectively.

In summary, occupational therapy practitioners play a vital role in addressing cognition, and we have the tools and knowledge to make a meaningful impact on our patients' lives. By advocating for our patients, staying informed, and using evidence-based approaches, we can help individuals with cognitive impairments lead more fulfilling and independent lives.

Thank you for joining this session.

Adamit, T., Shames, J., & Rand, D. (2021). Effectiveness of the Functional and Cognitive Occupational Therapy (FaC o T) intervention for improving daily functioning and participation of individuals with mild stroke: A randomized controlled trial. International journal of environmental research and public health , 18 (15), 7988. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18157988

Cognition, Cognitive Rehabilitation, and Occupational Performance. (2019). AJOT , 73 (Supplement_2), 7312410010p1–7312410010p26. https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.2019.73S201

Edwards, D. F., Wolf, T. J., Marks, T., Alter, S., Larkin, V., Padesky, B. L., Spiers, M., Al-Heizan, M. O., & Giles, G. M. (2019). Reliability and validity of a functional cognition screening tool to identify the need for occupational therapy. AJOT , 73 (2), 7302205050p1–7302205050p10. https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.2019.028753

Manee, F. S., Nadar, M. S., Alotaibi, N. M., & Rassafiani, M. (2020). Cognitive assessments used in occupational therapy practice: A global perspective. Occupational Therapy International , 8914372. https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/8914372

Stigen, L., Bjørk, E., & Lund, A. (2022). Occupational therapy interventions for persons with cognitive impairments living in the community. Occupational therapy in health care , 1–20. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/07380577.2022.2056777

Covell-Pierson, K. (2023). Cognitive interventions in the home: A practical approach for OT professionals. OccupationalTherapy.com , Article 5638. Available at www.occupationaltherapy.com

Occupational therapist and entrepreneur, Krista Covell-Pierson is the founder and owner of Covell Care and Rehabilitation, LLC. Krista created Covell Care and Rehabilitation to improve the quality of services available for clients of all ages living in the community through a one-of-a-kind mobile outpatient practice which aims to improve the lives of clients and clinicians alike. Krista attended Colorado State University receiving degrees in social work and occupational therapy. She has worked in various settings including hospitals, home health, rehabilitation centers and skilled nursing. Through her private practice, Krista created a model that she teaches other therapists looking to start their own business. She has extensive experience as a fieldwork educator and received the Fieldwork Educator of the Year Award from Colorado State University. Krista served as the President of the Occupational Therapy Association of Colorado for two years. She presents to groups of professionals and community members on a regular basis and has a heart to help others become the best version of themselves.

Related Courses

Course: #5963 level: introductory 1 hour, incontinence: practical tips for the occupational therapy practitioner (part 1), course: #3609 level: intermediate 1 hour, incontinence: practical tips for the occupational therapy practitioner (part 2), course: #3610 level: intermediate 1 hour, assessing and preventing falls at home: a practical approach for the ot, course: #5413 level: intermediate 2 hours, covid-19 with older adults: an update, course: #5494 level: introductory 2.5 hours.

Our site uses cookies to improve your experience. By using our site, you agree to our Privacy Policy .

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Research-based occupational therapy education: An exploration of students’ and faculty members’ experiences and perceptions

Kjersti velde helgøy.

1 Center of Diakonia and Professional Practice, VID Specialized University, Stavanger, Norway

Jens-Christian Smeby

2 Centre for the Study of Professions, OsloMet – Oslo Metropolitan University, Oslo, Norway

Tore Bonsaksen

3 Department of Health and Nursing Science, Faculty of Social and Health Sciences, Inland Norway University of Applied Science, Elverum, Norway

4 Faculty of Health Studies, VID Specialized University, Sandnes, Norway

Nina Rydland Olsen

5 Department of Health and Functioning, Faculty of Health and Social Sciences, Western Norway University of Applied Sciences, Bergen, Norway

Associated Data

In accordance with restrictions imposed by the Norwegian Data Protection Services (NSD) with ID number 8453764, data must be stored on a secure server at VID Specialized University. The contents of the etics committe`s approval resolution as well as the wording of participants` written consent do not render public data access possible. Access to the study`s minimal and depersonalized data set may be requested by contacting the project manager, KVH, email: [email protected] or the institution: on.div@tsop .

Introduction

One argument for introducing research in bachelor`s degree in health care is to ensure the quality of future health care delivery. The requirements for research-based education have increased, and research on how research-based education is experienced is limited, especially in bachelor health care education programmes. The aim of this study was to explore how occupational therapy students and faculty members experienced and perceived research-based education.

This qualitative, interpretative description consisted of three focus group interviews with occupational therapy students in their final year (n = 8, 6 and 4), and three focus group interviews with faculty members affiliated with occupational therapy programmes in Norway (n = 5, 2 and 5). Interviewing both students and faculty members enabled us to explore the differences in their experiences and perceptions.

Five integrative themes emerged from the analysis: “introducing research early”, “setting higher expectations”, “ensuring competence in research methods”, “having role models” and “providing future best practice”. Research was described as an important aspect of the occupational therapy bachelor program as it helps ensure that students achieve the necessary competence for offering future best practice. Students expressed a need to be introduced to research early in the program, and they preferred to have higher expectations regarding use of research. Competence in research methods and the importance of role models were also highlighted.

Conclusions

Undergraduate health care students are expected to be competent in using research. Findings from our study demonstrated that the participants perceived the use of research during training as important to ensure future best practice. Increasing the focus on research in the programme’s curricula and efforts to improve students’ formal training in research-specific skills could be a starting point towards increased use of research in the occupational therapy profession.

Occupational therapists have positive attitudes towards research, but implement research evidence infrequently within their daily practice [ 1 ]. Professional education is believed to play an important role in the development of positive attitudes towards evidence-based practice (EBP) skills [ 2 , 3 ]. One approach to improving evidence-based practice uptake in clinical practice is through the integration of research in education [ 4 , 5 ]. Developing student’s research skills is an important aspect of EBP [ 6 ] and participation in a research course has been found to improve nursing student’s attitudes towards research [ 7 ]. The World Federation of Occupational Therapists recommends an occupation-focused curriculum that includes critical thinking, problem-solving, EBP, research and life-long learning [ 8 , p. 6]. As such, educators in occupational therapy are advised to engage in research [ 8 , p. 53].

Several studies have explored how to link research and teaching in higher education [ 9 – 20 ]. Based on previous research [ 9 , 10 , 15 – 20 ], Huet developed a research-based education model that distinguishes between research-led teaching and research-based teaching [ 14 ]. Research-led teaching means that academics use their expertise as active researchers or use the research of others to inform their teaching. Research-based teaching means that students develop research skills by being involved in research or other inquiry-based activities. Research-led teaching and research-based teaching is interconnected, and research and teaching should be seen as interlinked [ 14 ]. One strategy for linking research and teaching is to bring research into the classroom, e.g. through academics presenting their research relevant to the subject and discussing research outcomes and methods with students [ 14 ]. In a research-based learning environment, students learn how to become critical thinkers, lifelong learners and to generate discipline-enriching knowledge [ 14 ].

Research-based education has mainly been emphasized in disciplinary university education [ 21 ]. In medical education, students’ knowledge, perceptions and attitudes towards research have been examined in several studies [ 22 – 25 ]. In their review, Chang and Ramnanan [ 22 ] found that medical students had positive attitudes towards research. Similar results emerged in Paudel et al.`s cross-sectional study [ 24 ]. Kandell and Vereijken et al. [ 25 ] found that first-year students believed that research would be important to keeping up to date in their future clinical practice.

Less research has been carried out on research-based education in bachelor’s programmes in health care, but the requirements for research-based education have also increased in these programmes [ 21 , p. 11]. Some studies have, however, investigated the attitudes, skills and use of research among nursing students [ 4 , 7 , 26 ]. In their literature reviews, Ross [ 7 ] found that nursing students have positive attitudes towards research and Ryan [ 26 ] found that nursing students are generally positive towards the use of research. Ross [ 7 ] noted that participation in research courses and research-related activity improved students’ attitudes towards nursing research. Leach et al. [ 4 ] have argued that undergraduate research education has an impact on nursing students’ research skills and use of EBP.

Students in occupational therapy and physiotherapy have been found to share positive attitudes towards research [ 27 ]. Similarly, studies have found positive attitudes towards EBP among occupational therapy students [ 28 – 31 ]. Stronge and Cahill [ 29 ] found that students were willing to practice EBP, but a lack of time and clinical instructors not practising EBP were perceived as barriers. Stube and Jedlicka [ 28 ] and Jackson [ 30 ] highlighted the importance of learning EBP through fieldwork experiences. DeCleene Huber et al. [ 31 ] found that students were least confident in EBP skills that involved using statistical procedures and statistical tests to interpret study results. These studies focused mainly on students’ attitudes and competence in EBP and research utilization (RU), and other elements of research-based education, such as student’s exposure to and engagement with research evidence were not investigated.

Few studies have explored faculty members’ perceptions of research in undergraduate education. Wilson et al. [ 32 ] found that the way in which university teachers in university disciplines translate research into learning experiences depends on their own personal perception of research. Some academics have highlighted that disciplinary content must be learned before engaging in research [ 32 ]. This idea is in accordance with the findings of Brew and Mantai [ 33 ], who also found variations in the way in which academics conceptualized undergraduate research. Experiences, attitudes and barriers towards research have been examined among the junior faculty of a medical university, and findings indicate that fewer than half of the participants in the study were involved in research at the time [ 34 ]. Ibn Auf et al. [ 35 ] found that the factors significantly influencing positive perceptions of research experience among the faculty at medical programmes were being male, having had education in research during undergraduate level, having been trained in research following graduation, and having undertaking years of research. To our knowledge, few studies have been conducted on faculty members’ perceptions of research in health care education, and we have identified only one such study related to occupational therapy education [ 36 ]. In a survey Ordinetz [ 36 ] found that the faculty members had a positive attitude towards research-related activities, and they considered research as an integral component of their role. Still, participants found research-related activities difficult to perform.

Research into how research-based education is experienced and perceived by faculty members and students is limited, especially in bachelor’s programmes in health care [ 21 , p. 11]. To gain a better understanding of the advantages or disadvantages of linking teaching and research, we therefor aimed to explore students’ and faculty members’ experiences and perceptions of research-based education in one bachelor’s programme in health care in Norway. Our specific research questions were:

- How do students and faculty members in occupational therapy programmes perceive the emphasis on research in the programme?

- How do occupational therapy students and faculty members perceive the expectations regarding research during the programme?

- What similarities and differences exist between the experiences and perceptions of students and faculty members regarding research-based education in the programme?

Context of the research

In Norway, it is required that higher education should be research-based [ 37 ]. According to the Act relating to universities and university college § 1–1 b, education must be on the cutting edge in terms of research, development work and artistic practice [ 37 ]. In a recent white paper on quality in higher education, research-based education is defined as education that is linked to a research environment; is conducted by staff who also carry out research; builds on existing research in a particular field; provides knowledge about the philosophy of science and research methods; and provides opportunities for students to learn how research is conducted from staff or students themselves conducting research as a part of their studies [ 38 ].