- Open access

- Published: 07 May 2019

Knowledge translation in health: how implementation science could contribute more

- Michel Wensing ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-6569-8137 1 &

- Richard Grol 2 , 3

BMC Medicine volume 17 , Article number: 88 ( 2019 ) Cite this article

43k Accesses

204 Citations

50 Altmetric

Metrics details

Despite increasing interest in research on how to translate knowledge into practice and improve healthcare, the accumulation of scientific knowledge in this field is slow. Few substantial new insights have become available in the last decade.

Various problems hinder development in this field. There is a frequent misfit between problems and approaches to implementation, resulting in the use of implementation strategies that do not match with the targeted problems. The proliferation of concepts, theories and frameworks for knowledge transfer – many of which are untested – has not advanced the field. Stakeholder involvement is regarded as crucial for successful knowledge implementation, but many approaches are poorly specified and unvalidated. Despite the apparent decreased appreciation of rigorous designs for effect evaluation, such as randomized trials, these should remain within the portfolio of implementation research. Outcome measures for knowledge implementation tend to be crude, but it is important to integrate patient preferences and the increased precision of knowledge.

Conclusions

We suggest that the research enterprise be redesigned in several ways to address these problems and enhance scientific progress in the interests of patients and populations. It is crucially important to establish substantial programmes of research on implementation and improvement in healthcare, and better recognize the societal and practical benefits of research.

Peer Review reports

Across the world, decision makers in healthcare struggle with the uptake of rapidly evolving scientific knowledge into healthcare practice, organisation, and policy. Rapid uptake of high-value clinical procedures, technologies, and organisational models is needed to achieve the best possible healthcare outcomes. Perhaps an even bigger struggle is that of stopping practices that do not or no longer have high value, such as the use of antibiotics for mild respiratory infections. Targeted interventions to improve healthcare practice exist in nearly all countries, and include, for instance, financial incentive programs to enhance the performance of healthcare providers, continuing professional education, and tools to involve patients more actively in their care and enhance shared decision-making. Evaluations of such implementation interventions in realistic settings found mixed, and overall moderate effects [ 1 , 2 ]. As a consequence, there have been calls to harness research and development on this topic [ 3 ]. We believe, however, that in recent years there has been little progress in our understanding of how healthcare practice can be improved.

The growing field of research on how to improve healthcare is known under various names, such as quality improvement, (dissemination and) implementation research, and knowledge transfer or translation [ 4 ]. Implementation science has been defined as the “scientific study of methods to promote the systematic uptake of research findings and other evidence-based practices into routine practice, and, hence, to improve the quality and effectiveness of health services and care” [ 3 ]. Knowledge translation is a related field that aims to enhance the use and usefulness of research. It covers the design and conduct of studies, as well as the dissemination and implementation of findings [ 4 ]. In healthcare, quality and safety management comprises a set of activities that aim to improve healthcare quality and safety, using measurement, feedback to decision-makers and organizational change [ 5 ]. In this article, we consider these and related fields as largely overlapping, because, through better uptake of putting knowledge in practice, they all aim to improve healthcare practice and thus provide better outcomes for patients and populations [ 6 ]. Knowledge may take various forms, such as evidence-based practice guidelines, technologies, or healthcare delivery models with proven value. The field is usually associated with change of practice and behaviors, but resisting change may occasionally serve the same purpose (e.g. in the case of promoted changes for which the evidence is limited or negative).

An illustrative example of research on knowledge transfer in health concerns pay-for-performance in general practice, which was introduced more than a decade ago in the UK. Practice performance was operationalized in terms of performance indicators, for which many had strong underlying evidence. Higher scores were associated with higher financial payments. For instance, an interrupted time series analysis of changes in performance scores for diabetes, asthma, and coronary heart diseases between 1998 and 2007 showed substantial improvements. These improvements had started before 2004; the year in which the contract was introduced. In diabetes and asthma, but not for coronary heart disease, a significant acceleration of improvement has been found since 2004 [ 7 ]. Other research in the field has focused, for instance, on continuing education, organizational change, health system reforms, and patient involvement for improving healthcare and implementation of recommended practice.

Looking at the infrastructure for research on how to improve healthcare practice, many positive developments can be noted in recent decades. Major funders, such as the National Institute for Health Research in the UK, the National Institutes of Health in the USA, the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, and Innovationsfond in Germany, have made substantial funding available. Several large research programs (funded with many millions of euros, pounds or dollars) have been established, such as the Collaborations for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care (CLAHRCs; soon to be ARCs) in the UK. Scientific journals dedicated to the field have emerged, such as BMJ Quality & Safety , and Implementation Science , and many medical and health science journals publish research on healthcare improvement. Professorships and training programs for implementation science and quality improvement have been created, most notably in North America, but also in other countries. A variety of yearly or biannual scientific conferences focus on healthcare improvement, implementation science, and related fields.

Despite this emerging infrastructure and growing interest in the field, it seems to lag behind the high expectations. We are still far from understanding how healthcare practice can be improved rapidly, comprehensively, at large scale, and sustainably. In fact, this observation has been made several times in previous decades. For instance, in the year 2000, reflecting on 20 years of implementation research in healthcare, Grol and Jones argued that many questions had remained unanswered [ 8 ]. Seven years later, Grol, Wensing and Berwick argued that research on quality and safety in healthcare must be strengthened to develop the science in this field [ 9 ]. In 2014, Ivers and colleagues suggested that science is stagnating, based on an analysis of audit and feedback strategies [ 10 ]. We feel that progress in the field has been limited in the previous decade. This Opinion article focuses on what may be wrong in research and practice, and what could help to address the problems. It is informed by our research projects, lectures, teaching at graduate and postgraduate levels, participation in academic review committees, roles as journal editors, and repeated updates of our books on improving healthcare practice [ 11 , 12 ] in the previous 25 years.

Problems and possible strategies

Table 1 provides an overview of our analysis of problems in research and practice, and possible ways to address these.

Misfit between problems and approaches

Healthcare challenges vary widely. For instance, implementing the centralization of surgical procedures or emergency services in specific centers is very different from a change in a medication protocol, or the introduction of nurses for counseling on lifestyle changes. All of these changes may be backed up by strong research evidence on their value, but analysis of the implementation challenges in each of these examples would reveal very different determinants of implementation and outcomes. For instance, health system factors may be crucial for the effective centralization of services, while individual factors related to knowledge or behavioral routines are probably most relevant in changing medication protocols. However, there is often little association between the type of problem and the approach to change taken. More particularly, organizational and system-related problems tend to be ignored, even when these were detected, favoring individual educational and psychological approaches [ 13 ]. Organizational and system change may be difficult to achieve within the typical course of a research project.

Probably even more relevant is that many researchers and consultants tend to be stubbornly consistent in their approach, and stick, for instance, either to a psychological approach (arguing that all implementation requires individual behavior change), an organizational systems approach (arguing that organizations rather than individuals need to change), or an economic perspective (arguing that financial factors override everything else). We believe, however, that the chosen approach to change should match the problems to achieve change, rather than the favored discipline of the researcher or consultant [ 14 ]. To remedy the current situation, options include training researchers and consultants and providing them with a multi-faceted perspective on the issue of knowledge translation and with theoretical frameworks that cover multiple approaches, as well as working in multidisciplinary improvement teams. These approaches require multidisciplinary academic training to be better appreciated in universities, which tend to facilitate academic careers within traditional scientific disciplines.

Proliferation of concepts, theories and frameworks

In the past [ 15 ], research on the translation of knowledge into practice was dominated by a few theories, such as the ‘Diffusion of Innovations’ theory [ 16 ]. Nowadays, research on improving healthcare practice is characterized by a proliferation of concepts, theories and frameworks for knowledge translation and implementation [ 17 ]. Most are essentially structured lists of disconnected items, which are not explicitly linked to higher-level scientific theory [ 18 ]. They distinguish, for instance, between individual, organizational, system-related and innovation-related factors. Many of these proposed frameworks have not been applied and tested in more than one study. New frameworks typically ignore published work – particularly if it is older than a decade – so the reinvention of existing concepts and frameworks is common. The field has also suffered from many fashions and hypes, which often present high-level concepts (e.g. the ‘breakthrough’ approach to improvement) and were popular for a while, but then disappeared without contributing much to scientific progress.

Research that applies and tests concepts, theories or frameworks is largely organized in silos – bubbles of like-minded academics (e.g. epidemiologists, psychologists, sociologists, or economists). Among researchers, there is mixed interest in testing conceptual ideas in rigorous empirical research. Some are close to healthcare practice (e.g., as clinicians), but are not aware of the full range of available concepts, theories and frameworks. Others know and apply specific theories or frameworks, but may be insufficiently familiar with healthcare practice or policy to assess their usefulness. Furthermore, head-to-head comparisons and integrations of proposals from different silos are rare, because many researchers are inclined to stick to their favored approach. We suggest, however, that these would advance science far more than the continuous development of new theories within disconnected worlds. Rather than adding new frameworks, the focus should be on the testing, refinement and integration of theories. Furthermore, we think that these should be sufficiently concrete and specific. To be sufficiently informative, they may be related to a specific topic or field of application – although it remains open for debate as to what would be the appropriate aggregation level (e.g., antibiotics prescribing in primary care, medication prescribing generally, or ambulatory medical care).

Non-validated methods for stakeholder involvement

The involvement of stakeholders (e.g., patients, providers, payers) in the design and conduct of interventions to improve healthcare practice has been emphasized to the extent that it is now seen as the ‘holy grail’ of improvement. For instance, ‘mode 2’ knowledge generation has been characterized as socially distributed, organizationally diverse, application-oriented, and transdisciplinary, as opposed to the traditional, ‘ivory tower’ mode 1 [ 19 ]. Involvement usually takes the form of consultation of stakeholders through interviews or surveys, or the participation of stakeholders in boards. However, the evidence for this belief is – so far – largely anecdotal, and many methods for stakeholder involvement are poorly specified, so replication is difficult. For instance, integrated knowledge translation (collaboration between researchers and decision-makers) uses a variety of methods, but its outcomes are unknown [ 20 ]. Stakeholders are often heterogeneous with respect to knowledge, needs and preferences regarding a particular change. Attempts to develop and validate stakeholder-based, tailored interventions have met with various difficulties and uncertainties [ 21 ]. For example, it is unclear how available research evidence and theory is combined with stakeholder involvement, if stakeholders have suggestions that contradict existing knowledge. Stakeholder involvement also implies the use of resources, particularly health professionals’ time, which must be considered when planning implementation programs. We suggest that methods for stakeholder involvement must be better specified and validated in empirical research.

Decreased appreciation of rigorous designs for effect evaluation

In some circles of researchers, practitioners, and policy makers, there seems to have emerged a decreased appreciation of rigorous designs for effect evaluation in healthcare, such as randomized trials. Arguments for the criticism of randomized trials as a preferred study design are manifold, and include, for instance, the belief that many interventions are changed during application in practice, outcomes of interventions are largely context-dependent, rigorous evaluation is time-consuming and expensive, and biomedical knowledge is evolving too quickly to allow rigorous outcomes evaluation [ 22 ]. Implementation science needs a variety of study designs and methods, including systematic intervention development, observational pilot tests, qualitative studies, and quantitative simulation modeling. We believe that rigorous designs for effect evaluation, including randomized trials, should remain on the menu.

Several researchers appreciate randomized trials and other rigorous evaluation designs, but they focus on the effectiveness of interventions with respect to patients’ health. Implementation researchers can indeed make useful contributions to process evaluation and feasibility testing of interventions in studies of intervention effectiveness. While such research is important, it is unlikely to advance implementation science much, because this is not its primary objective, and, as a consequence, the methods are not fully aligned. For instance, clinical trials and trials in public health often benefit from optimized intervention fidelity and strict inclusion criteria for participants, which does not match with the requirements of research on quality improvement, knowledge translation and implementation science.

There are clearly various issues that must be carefully considered when designing rigorous evaluations of improvement and implementation interventions, such as the choice of outcome measures, the duration of follow-up, and the approach in control groups. Several trial designs, such as stepped wedge trials, provide options beyond the classic two-armed randomized trial – albeit often at the price of more complex statistical analysis. Advanced designs for rigorous evaluation can only be considered if the people involved understand and appreciate outcome evaluation in the first place. It cannot be assumed that this is the case. We therefore argue that the appreciation of outcome evaluation must be nurtured among healthcare providers, managers and policy-makers. This appreciation should extend to interventions for the improvement of healthcare practice.

Suboptimal outcomes measures

Strategies for improvement or implementation must be evaluated with respect to their effectiveness in changing healthcare practices as a primary outcome of interest. Many studies of interventions to improve healthcare practice use relatively simple outcomes measures, such as clinical behaviors, which have been documented in patient records or procedures for which reimbursement was requested. While such measures can be informative, they are often only crude indicators of the actual use of knowledge in healthcare practice. Recent and continuing work on the pragmatic use of outcomes in implementation research has emphasized the importance of acceptability, feasibility, compatibility with routines, and perceptions of usefulness [ 23 ]. In some studies, however, health outcomes are primary outcomes – although these may not be responsive for improvements in the quality of care. The number of steps from interventions to health outcomes is relatively great, so that interpretation of causality is difficult if intermediate factors are not measured – particularly if health outcomes do not show intervention effects.

Furthermore, a fundamental problem is that the use of knowledge in decision-making rarely has simple, predictable associations with the decisions made. Ultimately, the key outcome is not crude frequencies of behaviors or health outcomes, but whether the available knowledge was taken into consideration in decision-making and healthcare practice. This knowledge is increasingly individualized on the basis of patients’ biological and psychological features, and comes from computerized decision support systems rather than clinical guidelines for patient populations. Patients’ preferences must also be taken into account when assessing the quality of decision-making. A knowledge-informed conversation between a patient and a clinician, resulting in a decision that is not coherent with some recommendation, should not automatically be documented as non-use of knowledge. We believe there is a need for new outcome measures of knowledge implementation, which take the changing nature of knowledge and the impact of patient preferences into account.

A fundamental challenge is to overcome the misconceptions, silo-thinking and self-interests among stakeholders. These stakeholders include politicians and managers who prefer to act on the basis of conviction rather than research evidence, healthcare providers who deny that research findings apply to them, and researchers who prefer to focus on concepts and approaches that fit their particular academic background. Global investment in the research infrastructure of knowledge implementation and quality improvement in healthcare provides major opportunities, but also a high responsibility for all involved.

After participating in many grant review panels, we conclude that the assessment of project applications is often dominated by the perceived relevance of the health issue or healthcare problem on which it focuses. The project’s contribution to the agenda of research on how to improve healthcare practice is usually of secondary importance, at best. This practice of healthcare research funding has resulted in many researchers in the field who do one or two projects on how to improve healthcare practice, and then leave the field, because they see no perspective for a career, or lack real interest. As a result, research on healthcare improvement and knowledge implementation is currently fragmented in different, largely disconnected, communities [ 24 ].

We think that coordinated and longer lasting research programs are needed to enhance the continuity of researchers in the field, which is crucial for knowledge accumulation. Knowledge translation and healthcare improvement in healthcare needs research centers or networks that bring together scientists with different backgrounds who can work on sequential projects over a longer period of time. Examples exist, and include an international research network to examine and optimize feedback interventions for implementation [ 25 ], and a large center for the study of healthcare improvement [ 26 ]. Effective programmatic research requires, among other things, institutional funding for core staff, multidisciplinary composition of groups, realistic and continuous funding opportunities for research projects, career opportunities for young and mid-career researchers, and integration in locally relevant infrastructures (e.g., routine quality improvement in hospitals). It also requires focused education. For instance, some graduation programs for implementation science in healthcare have been established [ 24 ], but their long-term success depends on graduated students’ opportunities in the labor market.

The field would also be enhanced by the revision of procedures for accountability and recognition of performance in academic institutions. Research on healthcare improvement and implementation is unlikely to provide ‘discoveries’, but studies can add substantially to the body of knowledge and thus support users in practice, management and policy. Citations in scientific journals are problematic as a sole criterion for review of performance because users (e.g. clinicians, managers, policy-makers) rarely cite publications, as most do not publish scientific papers. Several complementary methods for performance review are available, but their validity and feasibility remain challenging [ 27 ]. Perhaps most importantly, research on improving healthcare and knowledge implementation requires a higher appreciation of the field in the academic and health community, and alignment of resources and power in institutions accordingly.

The ultimate aim of research on knowledge implementation in healthcare is for interventions to improve healthcare practice to become more effective, thus leading to better care and outcomes for patients and populations. We believe that the research enterprise in this field must be redesigned in several ways to make this happen.

Grol R, Grimshaw J. From best evidence to best practice. Lancet. 2003;361:1225–30.

Article Google Scholar

Grimshaw JM, Eccles MP, Lavis JN, Hill SJ, Squires JE. Knowledge translation of research findings. Implem Sci. 2012;7:50.

Eccles MP, Mittmann BS. Welcome to Implementation Science. Implem Sci. 2006;1:1.

Graham ID, Logan J, Harrison MB, Straus SE, Tetroe J, Caswell W, et al. Lost in knowledge translation: time for a map? J Cont Educ Health Prof. 2006;26:13–24.

Dixon-Woods M. Harveian oration 2018: improving quality and safety in healthcare. Clin Med. 2019;19:47–56.

Theobald S, Brandes N, Gyapong M, El-Saharty S, Proctor E, Diaz T, et al. Implementation research: new imperatives and opportunities in global health. Lancet. 2018;392:S0140–6736.

Campbell SM, Reeves D, Kontopantelis E, Sibbald B, Roland R. Effects of pay for performance on the quality of primary care in England. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:368–78.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Grol R, Jones R. Twenty years of implementation research. Fam Pract. 2000;17(Suppl 1):S32–5.

Grol R, Berwick D, Wensing M. On the trail of quality and safety in healthcare. BMJ. 2008;338:74–6.

Ivers NM, Grimshaw JM, Jamvedt G, Flottorp S, O’Brien MA, French SD, et al. Growing literature, stagnant science? Systematic review, meta-regression and cumulative meta-analysis of audit and feedback interventions in health care. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29:1534–41.

Wensing M, Grol R. Implementatie: Effectieve verandering in de patiëntenzorg. Zevende Druk. [effective change in patient care. 7th edition.] Houten: Boom Stafleu Van Loghum, 2017.

Grol R, Wensing M, Eccles M, Davies. Improving patient care. The implementation of change in clinical practice. 2nd ed. Chichester: Wiley, BMJ Books; 2013.

Book Google Scholar

Bosch M, Van der Weijden T, Wensing M, Grol R. Tailoring quality improvement interventions to identified barriers: a multiple case analysis. J Eval Clin Pract. 2007;13:161–8.

Grol R. Beliefs and evidence in changing clinical practice. BMJ. 1997;315:418–21.

Estabrooks CA, Derksen L, Winther C, Lavis JN, Scott SD, Wallin L, et al. The intellectual structure and substance of the knowledge utilization field: alongitudinal author co-citation analysis, 1945 to 2004. Implement Sci. 2008;3:49.

Rogers EM. Diffusion of innovations. 4th ed. New York: The Free Press; 1995.

Google Scholar

Strifler L, Cardosa R, McGowan J, Cogo E, Nincic V, Khan PA, et al. Scoping review identifies significant number of knowledge translation theories, models, and frameworks with limited use. J Clin Epidemiol. 2018;100:92–102.

Nilsen P. Making sense of implementation theories, models and frameworks. Implem Sci. 2015;10:53.

Gibbons M, Limoges C, Nowotny H. The new production of knowledge: the dynamics of science and research in contemporary societies. London: Sage; 1997.

Gagliardi AR, Berta W, Kothari A, Boyko J, Urquhart R. Integrated knowledge translation (IKT) in health care: a scoping review. Implem Sci. 2016;11:38.

Wensing M. The tailored implementation in chronic diseases project: introduction and main findings. Implem Sci. 2017;12:5.

Greenhalgh T, Howick J, Maskrey N. Evidence-based medicine renaissance group. Evidence based medicine: a movement in crisis? BMJ. 2014;348:g3725.

Powell BJ, Stanick CF, Halko HM, Dorsey CN, Weiner BJ, Barwick M, et al. Toward criteria for pragmatic measurement in implementation research and practice: a stakeholder-driven approach using concept mapping. Implem Sci. 2017;12:118.

Wensing M, Grimshaw JM, Eccles MP. Does the world need a scientific society for research on how to improve healthcare? Implem Sci. 2012;7:10.

Ivers NM, Grimshaw JM. Reducing waste with implementation laboratories. Lancet. 2016;388:547–8.

Ullrich C, Mahler C, Forstner J, Szecsenyi J, Wensing M. Teaching implementation science in a new master of science program in Germany: a survey of stakeholder expectations. Implem Sci. 2017;12:55.

Greenhalgh T, Raftery J, Hanney S, Glover M. Research impact: a narrative review. BMC Med. 2016;14:78.

Download references

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

There was no specific funding for this manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

Author information, authors and affiliations.

Department of General Practice and Health Services Research, Heidelberg University Hospital, Im Neuenheimer Feld, 130.3, 69120, Heidelberg, Germany

Michel Wensing

Radboud Institute for Health Sciences, Radboud University Medical Center, Geert Grooteplein Zuid 10, 6525, Nijmegen, GA, Netherlands

Richard Grol

Maastricht University, Minderbroedersberg 4-6, 6211, Maastricht, LK, Netherlands

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

MW and RG collaboratively conceived the idea for this manuscript. MW wrote draft versions and RG provided substantial comments. Both authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript. MW guarantees the scientific integrity of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Michel Wensing .

Ethics declarations

Authors’ information.

Michel Wensing is Professor of Health Services Research and Implementation Science at Heidelberg University and Editor-in-Chief of the journal Implementation Science . Richard Grol is a retired professor of Quality of Care with an extensive scientific and societal track record.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Consent for publication, competing interests.

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Wensing, M., Grol, R. Knowledge translation in health: how implementation science could contribute more. BMC Med 17 , 88 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-019-1322-9

Download citation

Received : 10 February 2019

Accepted : 10 April 2019

Published : 07 May 2019

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-019-1322-9

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Knowledge transfer

- Implementation science

- Quality improvement

- Research policy

BMC Medicine

ISSN: 1741-7015

- Submission enquiries: [email protected]

- General enquiries: [email protected]

Systematic review

- Open access

- Published: 04 March 2020

Knowledge translation strategies for dissemination with a focus on healthcare recipients: an overview of systematic reviews

- Evelina Chapman 1 ,

- Michelle M. Haby ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-6203-9195 2 , 3 ,

- Tereza Setsuko Toma 4 ,

- Maritsa Carla de Bortoli 4 ,

- Eduardo Illanes 5 ,

- Maria Jose Oliveros 6 &

- Jorge O. Maia Barreto 1

Implementation Science volume 15 , Article number: 14 ( 2020 ) Cite this article

28k Accesses

59 Citations

27 Altmetric

Metrics details

While there is an ample literature on the evaluation of knowledge translation interventions aimed at healthcare providers, managers, and policy-makers, there has been less focus on patients and their informal caregivers. Further, no overview of the literature on dissemination strategies aimed at healthcare users and their caregivers has been conducted. The overview has two specific research questions: (1) to determine the most effective strategies that have been used to disseminate knowledge to healthcare recipients, and (2) to determine the barriers (and facilitators) to dissemination of knowledge to this group.

This overview used systematic review methods and was conducted according to a pre-defined protocol. A comprehensive search of ten databases and five websites was conducted. Both published and unpublished reviews in English, Spanish, or Portuguese were included. A methodological quality assessment was conducted; low-quality reviews were excluded. A narrative synthesis was undertaken, informed by a matrix of strategy by outcome measure. The Health System Evidence taxonomy for “consumer targeted strategies” was used to separate strategies into one of six categories.

We identified 44 systematic reviews that describe the effective strategies to disseminate health knowledge to the public, patients, and caregivers. Some of these reviews also describe the most important barriers to the uptake of these effective strategies. When analyzing those strategies with the greatest potential to achieve behavioral changes, the majority of strategies with sufficient evidence of effectiveness were combined, frequent, and/or intense over time. Further, strategies focused on the patient, with tailored interventions, and those that seek to acquire skills and competencies were more effective in achieving these changes. In relation to barriers and facilitators, while the lack of health literacy or e-literacy could increase inequities, the benefits of social media were also emphasized, for example by widening access to health information for ethnic minorities and lower socioeconomic groups.

Conclusions

Those interventions that have been shown to be effective in improving knowledge uptake or health behaviors should be implemented in practice, programs, and policies—if not already implemented. When implementing strategies, decision-makers should consider the barriers and facilitators identified by this overview to ensure maximum effectiveness.

Protocol registration

PROSPERO: CRD42018093245 .

Peer Review reports

Contributions to the literature

Much evidence has been developed to ensure that the results of research are used by health policy-makers and practitioners. However, the challenges of research use for patients and the public are greater and there is less research in this area.

This review is the first synthesis of systematic review evidence that can help ensure that research results are used by patients and the public and that is not limited to specific diseases.

The use of Information and Communication Technologies is the new great challenge to increase access and to achieve greater equity in health, especially in low-middle income countries.

Knowledge translation (KT) is “the synthesis, exchange, and application of knowledge by relevant stakeholders to accelerate the benefits of global and local innovation in strengthening health systems and improving people’s health” [ 1 ]. The process of KT ensures that evidence from research is used by relevant stakeholders, including healthcare providers, managers, policy-makers, informal caregivers, patients, and the public in the improvement of health [ 2 ]. While there is an ample literature on the evaluation of interventions aimed at healthcare providers, managers, and policy-makers, there has been less focus on patients and their informal caregivers.

“Patient-mediated” KT interventions are those strategies that involve patients in their own healthcare and have the aim to improve patient knowledge, relationship with the provider, the appropriateness of health service use, satisfaction with the provision of care experience, adherence to the recommended treatment, and other health behaviors and outcomes [ 3 ].

The Canadian Institutes for Health Research (CIHR), a leader in the science and practice of knowledge translation, have recognized four key elements in the process of KT: synthesis, dissemination, exchange, and ethically sound application of knowledge. For this overview, we will be focusing on dissemination as a core strategy in KT. Dissemination involves identifying the appropriate audience and tailoring the message and medium to the audience [ 4 ]. Dissemination of health-related information is the active, tailored, and targeted distribution of information or interventions via determined channels using planned strategies to a specific public health or clinical practice audience, and has been characterized as a necessary but not sufficient antecedent of knowledge adoption and implementation [ 5 ]. According to CIHR, dissemination can include elements such as summaries for/briefings to stakeholders, educational sessions with patients, practitioners and/or policy makers, engaging knowledge users in developing and executing dissemination/implementation plans, tools creation, and media engagement. Dissemination can be done through different information and communication technologies (ICT) based or not on the internet, i.e., videos, websites, brochures, decision aids, or art pieces.

There are many models and theories to explain what makes KT for healthcare recipients (and providers) effective [ 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 ]. These theories have varying objectives, which range from information provision individually or to large audiences (e.g., mass media) to achieving behavior change through education or skills acquisition. When focusing on behavior change, the aim is to increase the capacity to use and apply evidence effectively, thus achieving better health outcomes including quality of life. Desired outcomes of these models include shared decision-making between patients, their families, and providers; patient-provider communication; self-efficacy; adherence; improved access; and cure or survival. Intermediate outcomes could include healthcare users’ improved health knowledge, health behaviors, and physiologic measures; patient satisfaction; and reduced costs [ 10 ].

Further, in KT processes addressed to patients and informal caregivers, it is important to consider determinants or barriers at the level of healthcare recipients, i.e., knowledge, language, and cultural differences, skills deficits, attitudes, access to care and motivation to change, among others [ 7 , 10 , 11 , 12 ]. Also, it is usual practice to combine multicomponent dissemination strategies such as a combination of reach, motivation, or ability goals.

For the purpose of this overview, we have focused on dissemination strategies aimed at healthcare users and their caregivers in order to improve health and wellbeing. We used the taxonomy developed by Lavis et al. to organize the results, which includes six groups of strategies that are explained later [ 13 ].

This overview addressed two specific research questions:

How effective are the strategies that have been used to disseminate knowledge to healthcare recipients (both for the general public and patients)?

What are the barriers (and facilitators) to disseminate knowledge to healthcare recipients (both for the general public and patients)?

This overview used systematic review methodology and adheres to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) statement [ 14 ]. A systematic review protocol was written and registered prior to undertaking the searches [ 15 ]. Deviations from the protocol are noted.

Inclusion criteria for studies

Studies were selected based on the following inclusion criteria.

Types of studies

Systematic reviews (SRs) that included quantitative studies of any design that provided information on the effectiveness of dissemination strategies. SRs of qualitative studies that describe barriers and facilitators to uptake of research evidence were also included.

Types of participants

We included studies that involved healthcare recipients as the main focus, such as the general public, patients, caregivers, or patient groups. We excluded studies where other users, such as practitioners, policy-makers, educators, decision-makers, health care administrators, and community leaders, were the main focus. We also excluded studies where the dissemination strategy was directed to participants with a single health issue, e.g., multimedia interventions to promote HIV testing. This was to ensure a more general approach to strategies for dissemination of knowledge to healthcare recipients.

Types of interventions

SRs that evaluated KT dissemination strategies aimed at healthcare recipients or caregivers were included. The dissemination strategies were defined based on the Health System Evidence taxonomy [ 13 ] for “consumer targeted strategies” as follow:

Information or education provision: strategies to enable consumers to know about their treatment and their health.

Behavior change support: interventions which focus on the adoption or promotion of health and treatment behaviors at an individual level, such as adherence to medicines.

Skills and competencies development: strategies that focus on the acquisition of skills relevant to self-management.

(Personal) Support: interventions which provide assistance and encouragement to help patients cope with and manage their health and ongoing medical issues, such as counseling and follow up on treatment efficacy.

Communication and decision-making facilitation: strategies to involve consumers in decision-making about healthcare.

System participation: interventions to involve patients and/or caregivers in decision-making processes at a system level.

The dissemination element could be written on paper (i.e., pamphlets, flyers, booklets), verbal (i.e., using telephone), or written or verbal using ICT (i.e., e-health, m-health, websites, multimedia, telemedicine, patient reminder, etc.). The dissemination could be done individually, in groups, or massively.

Types of comparisons

There were no restrictions on types of comparisons.

Types of outcome measures

We included outcomes related to the effectiveness of dissemination strategies addressed to health-care recipients, caregivers, or the general public, including change in knowledge, understanding, perception, attitudes, adherence to health recommendations, and behavior changes. Other proposed results were health status, access, use of services, social outcomes, user satisfaction, costs, and cost-effectiveness. Additionally, we considered barriers to uptake of research evidence through dissemination strategies at the level of knowledge, competency, health literacy, attitudes, access to care, and motivation to change.

Publications in English, Spanish, or Portuguese were included and there were no restrictions on the year of publication. Both published and gray literature were included.

Search strategy and sources of systematic reviews

A comprehensive search of ten databases and five websites was conducted. The databases searched for SRs were MEDLINE (Ovid); Embase (Ovid); ERIC (EBSCOHost); CINAHL (EBSCOHost); PsycINFO (Ovid); LILACS (BVSalud); and World Wide Science. The specialized sources of SRs were the Cochrane Library (including Cochrane Reviews, the Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects and Health Technology Assessment); Epistemonikos; and Health Systems Evidence.

Manual searches were conducted in Google and Google Scholar; EPPI-Center Systematic Reviews; Rx for Change ( https://www.cadth.ca/rx-change ); and 3ie–International Initiative for Impact Evaluation. In addition to the above sources that included gray literature, we manually searched the System for Information on Grey Literature in Europe (Open Grey— http://www.opengrey.eu ).

Electronic searches were conducted between 21 and 23 May 2018 and supplementary searches (reference lists, contact with authors, and gray literature) were conducted in January 2019. Databases were searched using keywords from keyword areas related to the participants, the intervention, outcomes, and study type—combined using “AND.” Keywords were searched for in the title and abstract fields and using Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms where available (search terms and strategies for the electronic searches are in Additional file 1 ). Results were downloaded into the EndNote reference management program (version X8.2) and duplicates were removed.

Screening and selection of studies

Titles and abstracts were screened independently according to the selection criteria by pairs of review authors (EC, JB, and MO). The full text of any potentially relevant papers was retrieved for closer examination. The inclusion criteria were then applied against the full text version of the papers independently by two reviewers (EC and MO). Disagreements regarding eligibility of studies were resolved by discussion, and a third reviewer (JB) consulted when necessary. All studies which initially appeared to meet the inclusion criteria but on inspection of the full text paper did not meet the inclusion criteria are listed in a table “Characteristics of excluded studies” together with reasons for their exclusion.

Data extraction

Information extracted from included SRs were objectives, study designs and number of studies included, date of last search, intervention/strategy, participants, settings, country of studies, and financing source, as well as outcome measures, findings, barriers, research gaps, and theories or frameworks. Data extraction was shared between six reviewers (EC, MB, TT, EI, MH, and MO) and checked by a second reviewer (EC). Disagreements were resolved through discussion and consensus.

After extracting data from the included SRs, reviewers completed a matrix previously designed using the Health Systems Evidence taxonomy [ 13 ] for each of the six strategies down the left-hand side with the different outcome measures across the top. While we started with the list of outcome measures specified in the protocol we had to expand the matrix because we found more types of outcome measures than originally proposed. Classification was done by each reviewer (EC, MB, TT, EI, MH, and MO) and checked by a second reviewer (EC).

Assessment of methodological quality

The methodological quality of included SRs was assessed independently by pairs of reviewers using A MeaSurement Tool to Assess systematic Reviews (AMSTAR) [ 16 ]. Disagreements in scoring were resolved by discussion and consensus. For this overview, SRs that achieved AMSTAR scores of 8 to 11 were considered high quality, scores of 4 to 7 medium quality, and scores of 0 to 3 low quality. SRs of low quality were excluded. We did not find any SRs of exclusively qualitative studies to inform barriers and facilitators so could not use the Confidence in the Evidence from Reviews of Qualitative research approach to assess the confidence of findings from qualitative syntheses [ 17 ] as proposed in the protocol. Instead, we found SRs with a mix of study designs that included qualitative research so the overall quality of these studies was evaluated with AMSTAR tool.

Data analysis

Findings from the included publications were synthesized using tables and a narrative summary informed by the matrix of strategy by outcome measure. Meta-analysis was not possible because the included studies were heterogeneous in terms of the populations, strategies/interventions tested, and outcomes measured. Further, few studies informed effectiveness measures. Thus, to inform the main results, we developed effectiveness statements using four categories and standardized language as proposed by Ryan et al. [ 9 ]. The decision rules took into account the results, their statistical significance, and the quality and number of studies that support the result. The four categories are (1) sufficient evidence, (2) some evidence, (3) insufficient evidence, and (4) insufficient evidence to determine effectiveness (Additional file 2 ). Category 4 was used to inform research gaps.

Search results

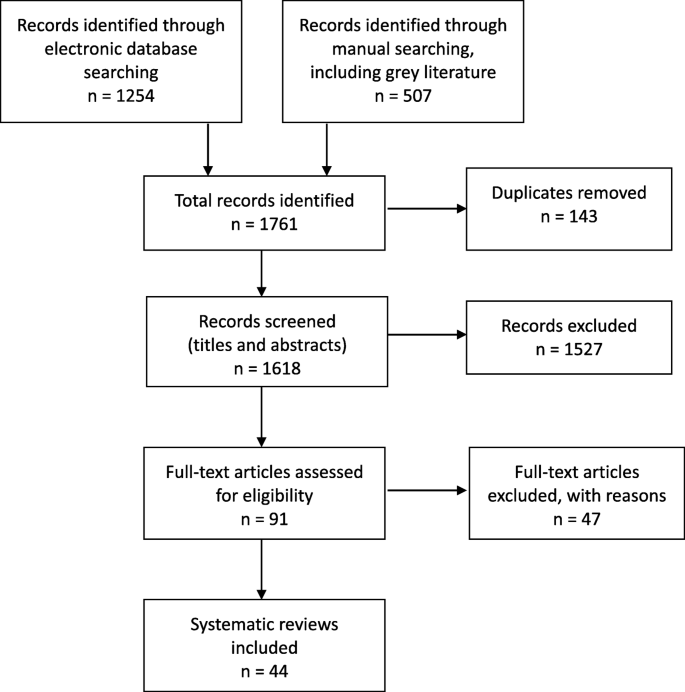

Forty-four SRs met the inclusion criteria for the overview [ 3 , 5 , 7 , 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 , 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 , 37 , 38 , 39 , 40 , 41 , 42 , 43 , 44 , 45 , 46 , 47 , 48 , 49 , 50 , 51 , 52 , 53 , 54 ]. The selection process for SRs and the number of papers found at each stage are shown in Fig. 1 . The reasons for exclusion of the 47 papers at full text stage are shown in Additional file 3 .

Study selection flow chart

Characteristics of included studies and quality assessment

Details of the characteristics of the included SRs and AMSTAR scores are in Additional file 4 (Tables 1 and 2 ). Of the 44 SRs, 19 had AMSTAR scores of high quality [ 7 , 9 , 10 , 12 , 20 , 21 , 24 , 31 , 35 , 36 , 38 , 43 , 44 , 45 , 47 , 48 , 49 , 50 , 54 ] and 25 were of medium quality [ 3 , 5 , 11 , 18 , 19 , 22 , 23 , 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 32 , 33 , 34 , 37 , 39 , 40 , 41 , 42 , 46 , 51 , 52 , 53 ]. Of the 44 SRs, 24 included both experimental and quasi-experimental designs [ 3 , 5 , 7 , 9 , 11 , 12 , 20 , 21 , 25 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 32 , 33 , 34 , 36 , 38 , 41 , 42 , 49 , 51 , 53 , 54 ], ten only included randomized controlled trials [ 18 , 23 , 24 , 26 , 35 , 43 , 47 , 48 , 50 , 52 ], and ten included both quantitative and qualitative research [ 10 , 19 , 22 , 31 , 37 , 39 , 40 , 44 , 45 , 46 ]. Seventeen SRs included only patients or caregivers [ 7 , 9 , 10 , 20 , 24 , 31 , 32 , 34 , 35 , 37 , 39 , 40 , 43 , 44 , 49 , 50 , 53 ], and the remaining 27 also included providers. Twenty SRs were informed by, or based on, a theory or framework [ 3 , 7 , 9 , 11 , 12 , 18 , 21 , 25 , 27 , 29 , 31 , 33 , 36 , 38 , 41 , 42 , 46 , 49 , 51 , 54 ].

The different strategies tested, and types of communication or dissemination tested in each of the SRs are shown in Additional file 5 . When reviewing the included SRs, we found outcome measures that were not included in the protocol (or in the “ Methods ” section of this review). These included shared decision-making between patients, their families, and providers, patient-provider communication, self-efficacy and/or self-management, awareness, beliefs, clinical results, coverage, use of services, empowerment, less suffering or anxiety, persuasion, safety, social support and influence, quality of life, health status and wellbeing, hospitalizations, length of consultation, participation in health, sustainability, choice, addiction to media, and readability. More details are in Additional file 6 .

Effectiveness statements

The effects of interventions are presented below by strategy according to the adopted taxonomy [ 13 ]. The SRs were divided into those testing the specific strategy alone (single) or in combination with other strategies (combined). Many reviews evaluated interventions involving multiple strategies and so contributed evidence to more than one category. More details are in Additional file 5 , Table 1 . The effectiveness statements are presented in Tables 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , and 5 for those with “sufficient” or “some evidence” (categories 1 and 2 in Additional file 2 ). Those with “insufficient evidence” (category 3) are in Additional file 7 and those with “insufficient evidence to determine” (category 4) were used to inform the research gaps (Additional file 8 ).

Providing information or education

Forty-one reviews included this strategy (Additional file 5 , Table 1 ) but only 17 provided evidence that was useful for the development of the effectiveness statements [ 7 , 9 , 11 , 12 , 21 , 26 , 28 , 29 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 37 , 39 , 40 , 44 , 49 , 52 ]. Seven of these 17 reviews were of high quality [ 7 , 9 , 12 , 21 , 35 , 44 , 49 ]. The remaining 24 SRs were used to inform the research gaps (Additional file 8 ). The effectiveness statements are presented in Table 1 and Additional file 7 .

Communication and decision-making facilitation

Twenty-seven reviews included this strategy (Additional file 5 , Table 1 ) but only 11 provided evidence that was useful for the development of the effectiveness statements [ 9 , 10 , 24 , 28 , 30 , 31 , 46 , 47 , 48 , 49 , 50 ]. Eight of these 11 reviews were of high quality [ 9 , 10 , 24 , 31 , 47 , 48 , 49 , 50 ]. The effectiveness statements are presented in Table 2 and Additional file 7 .

Acquiring skills and competencies

Twenty-six reviews included this strategy but only five provided evidence that was useful for the development of the effectiveness statements [ 5 , 9 , 11 , 22 , 53 ]. One of these five reviews was of high quality [ 9 ]. See Table 3 and Additional file 7 for the effectiveness statements.

Behavior change support

Thirty-nine reviews included this strategy but only 19 provided evidence that was useful for the development of the effectiveness statements [ 3 , 9 , 11 , 18 , 19 , 20 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 27 , 30 , 36 , 38 , 41 , 42 , 43 , 50 , 51 , 54 ]. Seven of these reviews were of high quality [ 9 , 20 , 21 , 24 , 36 , 38 , 43 , 50 ]. See Table 4 and Additional file 7 for the effectiveness statements.

Personal support

Thirty reviews included this strategy but only two provided evidence that was useful for the development of the effectiveness statements [ 9 , 49 ]—both were of high quality. See Table 5 and Additional file 7 for the effectiveness statements.

Consumer system participation

Twenty-eight reviews included this strategy but only six provided evidence that was useful for the development of the effectiveness statements [ 10 , 19 , 23 , 32 , 42 , 45 ]—two of these were of high quality [ 10 , 45 ]. In relation to consumer system participation, no single strategies were identified. For the combined strategies, none had sufficient evidence and only one had some evidence of effectiveness, with the resulting effectiveness statement:

The use of social media and telemonitoring (ICT platforms) for promoting patient engagement and delivering behavior change interventions may improve health outcomes [ 42 ].

The combined strategies with insufficient evidence are listed in Additional file 7 .

We did not find any SRs of exclusively qualitative studies. Of the 44 included SRs, ten included qualitative research among other study designs. For the synthesis of barriers (and facilitators) to KT to healthcare participants, 31 SRs contributed information. The barriers identified were grouped following the type of communication used for the intervention or strategy (Additional file 5 , Table 2 ). While this method of grouping barriers was not originally stated in the protocol, we found it to be the most logical way to group them due to the way in which barriers were reported in the included systematic reviews.

None of the SRs identified barriers to verbal communication specifically. However, in relation to patient advisory councils (which may use both verbal and electronic communication), the main barrier described was that the implementation takes a significant amount of time and resources for recruitment, holding meetings, and providing follow up [ 45 ].

For written information that does not require the internet, concerns were raised about motivation and awareness [ 29 , 49 ], health literacy [ 40 , 53 ], and comprehension and understanding [ 29 , 40 ]. Other possible barriers that should be considered are the reliability and trustworthiness of the information [ 29 ], personal needs [ 49 ], and text complexity and design [ 40 ].

For information technology interventions in general, barriers raised include health literacy, privacy and information quality concerns, access to technology, and information design [ 42 ].

Computer-based strategies, whether internet-based or not, present as barriers difficulties in the management of technologies, mainly for the elderly [ 19 ], e-literacy [ 25 , 31 , 51 ], privacy concerns, consumer’s personal feelings, socioeconomic factors [ 31 , 41 ], and health literacy [ 31 , 44 ]. Other barriers include reliability and trustworthiness in the information, lack of time and personal impairment [ 31 ], motivation and awareness, and information that does not meet personal needs [ 49 ], text complexity and lack of access to information [ 44 ].

Strategies that use multimedia not based on the internet bring difficulties like motivation, awareness, information that does not respond to personal need or without sufficient detail [ 49 ], problems of communication [ 35 ], and health literacy [ 18 , 52 ] for their implementation.

Internet-based multimedia strategies face barriers such as e-literacy [ 12 , 25 , 51 ], health literacy [ 11 , 37 , 44 ], motivation, awareness [ 12 , 29 ], concerns about reliability and trustworthiness [ 29 , 37 ], complexity of the text [ 37 , 44 ], consumer’s personal feelings, information overload, and information that does not match personal needs [ 37 ]. Other barriers were lack of internet access and personal skills [ 12 , 24 , 44 , 51 ], and comprehension, understanding, and self-management when self-management interventions packaged with guidelines are used [ 5 ].

Most of the studies did not discuss issues such as ethnicity, income level, or homelessness, which are important when considering the use of an internet-based technology to deliver an outpatient intervention. The long-term effects on individual persistence with chosen therapies and cost-effectiveness of the use of internet-based therapies and hardware and software development require continued evaluation [ 51 ]. Recent SRs have mentioned inequities such as lack of access to technology [ 42 ]. However, one review noted that a benefit of social media is that it can widen access to those who may not easily access health information via traditional methods, such as younger people, ethnic minorities, and lower socioeconomic groups [ 39 ].

For social media interventions, barriers on the individual level include health literacy [ 7 , 42 ] and the risk of a deterioration in the relationship between health professionals and patients [ 7 , 39 ], including the inability to meet the patients’ emotional and information needs [ 46 ]. Other concerns include how the information is presented [ 7 , 21 ], privacy, information quality, lack of internet access, trustworthiness in the information, information overload, and stigma about certain conditions [ 39 ]. Another highlighted barrier was the fact that the social content is used more than the educational content, i.e., participants use the social media to interact with other users more than as a means for self-education [ 38 ].

m-health (with mobile phone) strategies raise as the main barriers to its implementation issues such as e-literacy and lack of internet access [ 10 , 27 ], health literacy [ 34 , 44 ], socioeconomic factors [ 27 , 50 ], privacy concerns, lack of personal skills [ 10 ], text complexity [ 44 ], and the time-consuming nature of the technology [ 54 ]. Another potential limitation of m-health could be that the delivery of interventions can be interrupted if the mobile phone is stolen or lost. However, the same limitations exist with many other forms of communication (e.g., postal mail may be delivered to the wrong address, email boxes may be too full to receive messages) [ 27 ].

Barriers to implementation of telemedicine are also related to e-literacy, privacy concerns, lack of internet access, and personal skills [ 10 ].

For the implementation of patient decision aids, which can include pamphlets, videos, or web-based tools, barriers detected include decision aids that do not meet the needs of the population, clinicians unwilling to use them, and clinicians and healthcare consumers without skills for shared decision-making [ 48 ].

For this overview, we identified 44 SRs that describe the effective strategies to disseminate health knowledge to the public, patients, and caregivers. Some of these SRs also describe the most important barriers to the uptake of these effective strategies. The reviews that tested more general strategies were selected instead of those directed to a particular condition or setting. To our knowledge, this is the first overview of SRs addressing this objective.

While we reported the strategies and results according to the taxonomy adapted from the Health System Evidence database [ 13 ], we found that many strategies overlapped for both the type of intervention and the outcome measures. For example, interventions providing information or education could report outcomes related to behavior change or self-efficacy, and the primary intention could have been to increase knowledge. Situations like these were frequent and could be due to the use of combined strategies or to characteristics of the intervention itself, its intensity, frequency, or duration. The strategies reported in the included SRs could be directed to individuals or groups, in print or verbally, face to face, or remotely. In addition, interventions could range from single (e.g., a written information leaflet) to combined strategies. We considered a strategy to be combined when it used two or more verbal, print, or remote health information strategies (e.g., video, computer, and slide show presentations [ 11 ]), or different electronic communication types (based or not on the internet), such as telemedicine, ICT applications or ICT platforms [ 10 , 42 ], or social networking like Facebook or Twitter [ 39 , 46 ].

We found few SRs with a meta-analysis that could inform the magnitude of effects. Thus, an overall meta-analysis for each of the strategies could not be conducted, which is why we chose to adopt the approach proposed by Ryan et al. [ 9 ] and have presented the findings as evidence statements.

A key objective of the included interventions was to inform, improve knowledge, or to change health behaviors. To achieve behavioral changes, different strategies were used, such as training, coaching, or text messages. Factors that affected the effectiveness of the intervention included its frequency, intensity, and follow-up time. These factors are important to consider when implementing the chosen intervention strategies, including the applicability of the intervention in different modes of implementation and contexts.

When analyzing those strategies with the greatest potential to achieve behavioral changes, the majority of strategies with sufficient evidence of effectiveness were combined, frequent, and/or intense over time. Further, strategies focused on the patient, with tailored interventions, and those that seek to acquire skills and competencies were more effective in achieving these changes. Many of these strategies used toolkits or different platforms, based or not on the internet. Examples of strategies based on the internet include social networks, specific portals, tailored text messaging, or email [ 23 , 27 , 30 , 36 , 42 , 43 , 50 , 54 ]. Examples of strategies that are not always based on the internet are the use of videos, telephone calls, telemedicine, and telemonitoring [ 9 , 10 , 41 , 48 , 49 , 53 ].

Other examples of effective tailored interventions, such as those designed to improve communication or participation in decision-making between patients and healthcare providers, were the use of patient decision aids and patient information leaflets, provided electronically or not [ 10 , 48 , 49 ]. Interestingly, when coaching was added to patient decision aids, we found some evidence for improvements in knowledge and participation. Also, coaching, when compared to patient decision aids alone, increased values-choice agreement and improved satisfaction with the decision-making process [ 47 ]. In relation to satisfaction, we also found some evidence for improvement in patient satisfaction for interventions through multimedia before consultations designed to help patients with their information needs [ 35 ].

With regard to caregivers, in particular of patients with Alzheimer’s disease, we found good evidence for the effect of a home safety toolkit for improvements in home safety, risky behavior, and caregiver self-efficacy [ 53 ]. For interventions that involved patients and/or caregivers in decision-making processes at a system level, we did not find sufficient evidence to make any statements. Further, few studies included a follow-up period longer than 1 year or reported retention rate, thus it is not known if behavior change results are sustained over time [ 32 , 36 , 42 , 51 ].

Our second research question focused on barriers to the dissemination of knowledge to healthcare recipients, which are important to consider when implementing chosen intervention strategies. The barriers most frequently mentioned were related to ICT or to the information itself. For ICT, the main concerns were access to the technologies, including availability of the internet. On a personal level, the lack of skills for managing new technologies, privacy issues, lack of time, and deterioration of the doctor-patient relationship were also mentioned, especially when using social media or websites. As for the information itself, the lack of understanding or comprehension, the volume of information, text complexity and its design, information that did not meet the needs of the patients, and trustworthiness were the key barriers mentioned. While inequities were mentioned and were often related to the lack of health literacy or e-literacy, the benefits of social media were also emphasized, for example by widening access to health information, particularly for ethnic minorities and lower socioeconomic groups.

Strengths and limitations of the overview

Strengths of our overview were that only reviews of medium or high quality were included, as well as our focus on strategies that translated health information to patients and caregivers through different strategies and types of dissemination. Further, we focused on more general interventions rather than specific interventions, which are already abundant in the scientific literature and could be among the list of SRs that were excluded. While we did not find SRs of qualitative studies to analyze barriers to a better implementation of dissemination interventions, we did find considerable information and analysis of barriers in many of the included SRs. These included good quality studies on health literacy. Further, we were able to identify many research gaps that are detailed in Additional file 8 .

Limitations of our overview include limitations in the included SRs, such as the lack of clear description of the interventions, setting or samples, and outcomes in some reviews. Further, not all of the included SRs used theories or frameworks to inform the strategies. Finally, due to the heterogeneity in the interventions and outcomes, a meta-analysis was not possible.

Achieving improvements in knowledge uptake or health behaviors is difficult and the literature of effectiveness for the different strategies in the clinical field has been presented using a range of frameworks, theories, or taxonomies. While work is underway to develop consistent taxonomies for the design and reporting of behavior change and dissemination and implementation interventions, such as the behavior change wheel [ 55 ], the theoretical domains framework [ 56 , 57 ], and other taxonomies [ 58 ], these are not consistently applied in the existing literature. Further, few have been developed for patients or their caregivers, and there is more of a focus on implementation rather than dissemination. None of the developed frameworks were suitable for our context ( https://dissemination-implementation.org/viewAll_di.aspx ). Thus, given that this overview was aimed at healthcare decision-makers, we chose to use the Health Systems Evidence taxonomy of Lavis and colleagues [ 13 ]. The advantage of using this taxonomy is that it makes it easier for healthcare decision-makers to find, understand, and use the evidence contained in the overview. Further, while there is debate about how best to measure the effectiveness of complex behavior change interventions [ 59 , 60 ], these authors acknowledge that further work is needed. Until that work is conducted and consensus achieved, systematic reviews of randomized controlled trials (and other designs), as used in this overview, are the currently accepted best method.

This overview of systematic reviews has shown that a variety of dissemination strategies aimed at healthcare users and their caregivers can improve health and wellbeing in different ways. However, implementation of our findings will need to consider the particular context in which a strategy is to be implemented. This overview will help decision-makers choose the most effective dissemination strategies and will also inform them as to the factors that they should consider when implementing those strategies.

Implications for practice and policy

Those interventions that have been shown to be effective in improving knowledge uptake or health behaviors should be implemented in practice, programs, and policies—if not already implemented. The benefits of strategies such as e-health and m-health, including telemedicine, should be considered for knowledge dissemination and to improve health behaviors—especially in populations with lack of access to traditional sources of healthcare, including in remote or rural areas. The application of distance technology may strengthen the continuity of care between patient and clinician by improving access and supporting the coordination of healthcare activities from a single source. When designing KT strategies, not only the effectiveness of the strategy but also the characteristics of the interventions should be taken into account, such as the type of dissemination (electronic or not), frequency, intensity, and follow-up time. It is also important to ensure that the content of the messages is addressed to people with low literacy, low numeracy, and low e-literacy. The knowledge disseminated should be readable, comprehensible, relevant, consistent, unambiguous, and credible for patients. Moreover, patients should be invited to participate in its design. All of these strategies are likely to increase the success of the dissemination.

Implications for research

Future research should focus on the areas identified as research gaps in Additional file 8 . In addition, researchers should ensure that the interventions tested are well described in their papers. Likewise, systematic reviewers should also ensure that they include a clear description of the interventions, settings, samples, and outcomes included in their reviews to facilitate their evaluation and implementation by decision-makers.

Availability of data and materials

All files supporting the conclusions of this article are included within the article or in Additional files 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , and 6 .

Abbreviations

A MeaSurement Tool to Assess systematic Reviews

Absolute risk reduction

Canadian Institutes for Health Research

Information and Communication Technologies

- Knowledge translation

Medical Subject Headings

Number needed to treat

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

Relative risk reduction

Short message service

Pablos-Mendez A, Shademani R. Knowledge translation in global health. J Contin Educ Heal Prof. 2006;26(1):81–6.

Article Google Scholar

WHO. Knowledge translation framework for Ageing and health. Geneva: Department of Ageing and Life-Course, World Health Organization; 2012.

Google Scholar

Gagliardi AR, Legare F, Brouwers MC, Webster F, Badley E, Straus S. Patient-mediated knowledge translation (PKT) interventions for clinical encounters: a systematic review. Implement Sci. 2016;11(1):26.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Graham ID, Tetroe JM. Getting evidence into policy and practice: perspective of a health research funder. J Can Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2009;18(1):46–50.

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Vernooij RW, Willson M, Gagliardi AR, members of the Guidelines International Network Implementation Working G. Characterizing patient-oriented tools that could be packaged with guidelines to promote self-management and guideline adoption: a meta-review. Implement Sci. 2016;11:52.

Albrecht L, Archibald M, Arseneau D, Scott SD. Development of a checklist to assess the quality of reporting of knowledge translation interventions using the workgroup for intervention development and evaluation research (WIDER) recommendations. Implement Sci. 2013;8(1):52.

McCormack L, Sheridan S, Lewis M, Boudewyns V, Melvin CL, Kistler C, et al. Communication and dissemination strategies to facilitate the use of health-related evidence. Evidence Report/Technology Assessment No. 213. AHRQ Publication No. 13(14)-E003-EF. Rockville: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2013.

Pantoja T, Opiyo N, Lewin S, Paulsen E, Ciapponi A, Wiysonge CS, et al. Implementation strategies for health systems in low-income countries: an overview of systematic reviews. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;9:CD011086.

PubMed Google Scholar

Ryan R, Santesso N, Lowe D, Hill S, Grimshaw J, Prictor M, et al. Interventions to improve safe and effective medicines use by consumers: an overview of systematic reviews. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;4:CD007768.

Finkelstein J, Knight A, Marinopoulos S, Gibbons MC, Berger Z, Aboumatar H, et al. Enabling patient-centered care through health information technology. Evidence Report/Technology Assessment No. 206. AHRQ Publication No. 12-E005-EF. Rockville: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. 2012.

Berkman ND, Sheridan SL, Donahue KE, Halpern DJ, Viera A, Crotty K, et al. Health literacy interventions and outcomes: an updated systematic review. Evidence Report/Technology Assesment No. 199. AHRQ Publication Number 11-E006. Rockville: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. 2011.

Car J, Lang B, Colledge A, Ung C, Majeed A. Interventions for enhancing consumers’ online health literacy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;(6). Art. No.: CD007092.

Lavis JN, Wilson MG, Moat KA, Hammill AC, Boyko JA, Grimshaw JM, et al. Developing and refining the methods for a ‘one-stop shop’ for research evidence about health systems. Health Res Policy Syst. 2015;13(1):10.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Group P. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097.

Chapman E, Barreto JOM. Knowledge translation overview: strategies for dissemination with a focus on recipient health care. PROSPERO 2018 CRD42018093245. Available from: http://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/display_record.php?ID=CRD42018093245 .

Shea BJ, Grimshaw JM, Wells GA, Boers M, Andersson N, Hamel C, et al. Development of AMSTAR: a measurement tool to assess the methodological quality of systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2007;7:10.

Lewin S, Glenton C, Munthe-Kaas H, Carlsen B, Colvin CJ, Gulmezoglu M, et al. Using qualitative evidence in decision making for health and social interventions: an approach to assess confidence in findings from qualitative evidence syntheses (GRADE-CERQual). PLoS Med. 2015;12(10):e1001895.

Abu Abed M, Himmel W, Vormfelde S, Koschack J. Video-assisted patient education to modify behavior: a systematic review. Patient Educ Couns. 2014;97(1):16–22.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Akesson KM, Saveman BI, Nilsson G. Health care consumers’ experiences of information communication technology--a summary of literature. Int J Med Inform. 2007;76(9):633–45.

Akl EA, Oxman AD, Herrin J, Vist GE, Terrenato I, Sperati F, et al. Framing of health information messages. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;(12). Art. No.: CD006777.

Akl EA, Oxman AD, Herrin J, Vist GE, Terrenato I, Sperati F, et al. Using alternative statistical formats for presenting risks and risk reductions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;3:1–90.

Ammentorp J, Uhrenfeldt L, Angel F, Ehrensvard M, Carlsen EB, Kofoed PE. Can life coaching improve health outcomes?—a systematic review of intervention studies. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13:428.

Ammenwerth E, Schnell-Inderst P, Hoerbst A. The impact of electronic patient portals on patient care: a systematic review of controlled trials. J Med Internet Res. 2012;14(6):e162.

Atherton H, Sawmynaden P, Sheikh A, Majeed A, Car J. Email for clinical communication between patients/caregivers and healthcare professionals. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;11:CD007978.

Bekker HL, Winterbottom AE, Butow P, Dillard AJ, Feldman-Stewart D, Fowler FJ, et al. Do personal stories make patient decision aids more effective? A critical review of theory and evidence. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2013;13(Suppl 2):S9.

Buchter R, Fechtelpeter D, Knelangen M, Ehrlich M, Waltering A. Words or numbers? Communicating risk of adverse effects in written consumer health information: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2014;14:76.

Cole-Lewis H, Kershaw T. Text messaging as a tool for behavior change in disease prevention and management. Epidemiol Rev. 2010;32:56–69.

Edwards A, Hood K, Matthews E, Russell D, Russell I, Barker J, et al. The effectiveness of one-to-one risk communication interventions in health care: a systematic review. Med Decis Mak. 2000;20(3):290–7.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Faber M, Bosch M, Wollersheim H, Leatherman S, Grol R. Public reporting in health care: how do consumers use quality-of-care information? A systematic review. Med Care. 2009;47(1):1–8.

Fjeldsoe BS, Marshall AL, Miller YD. Behavior change interventions delivered by mobile telephone short-message service. Am J Prev Med. 2009;36(2):165–73.

Gibbons MC, Wilson RF, Samal L, Lehman CU, Dickersin K, Lehmann HP, et al. Impact of consumer health informatics applications. Evidence Report/Technology Assessment No. 188. AHRQ Publication No. 09(10)-E019. Rockville: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. 2009.

Health Quality Ontario. Electronic tools for health information exchange: an evidence-based analysis. Ont Health Technol Assess Ser. 2013;13(11):1–76. Available from: http://www.hqontario.ca/en/documents/eds/2013/full-report-OCDM-etools.pdf .

PubMed Central Google Scholar

Hoffman BL, Shensa A, Wessel C, Hoffman R, Primack BA. Exposure to fictional medical television and health: a systematic review. Health Educ Res. 2017;32(2):107–23.

Ketelaar NA, Faber MJ, Flottorp S, Rygh LH, Deane KH, Eccles MP. Public release of performance data in changing the behaviour of healthcare consumers, professionals or organisations. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;(11). Art. No.: CD004538.

Kinnersley P, Edwards A, Hood K, Cadbury N, Ryan R, Prout H, et al. Interventions before consultations for helping patients address their information needs. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(3). Art. No.: CD004565.

Laranjo L, Arguel A, Neves AL, Gallagher AM, Kaplan R, Mortimer N, et al. The influence of social networking sites on health behavior change: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2015;22(1):243–56.

Loudon K, Santesso N, Callaghan M, Thornton J, Harbour J, Graham K, et al. Patient and public attitudes to and awareness of clinical practice guidelines: a systematic review with thematic and narrative syntheses. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14:321.