Log in using your username and password

- Search More Search for this keyword Advanced search

- Latest content

- Current issue

- Write for Us

- BMJ Journals

You are here

- Volume 17, Issue 3

- Service evaluation, audit and research: what is the difference?

- Article Text

- Article info

- Citation Tools

- Rapid Responses

- Article metrics

- Alison Twycross 1 ,

- Allison Shorten 2

- 1 Faculty of Health and Social Care , London South Bank University , London , UK

- 2 Yale University School of Nursing , New Haven, Connecticut , USA

- Correspondence to : Dr Alison Twycross Faculty of Health and Social Care, London South Bank University, London SE1 0AA, UK; alisontwycross{at}hotmail.com

https://doi.org/10.1136/eb-2014-101871

Statistics from Altmetric.com

Request permissions.

If you wish to reuse any or all of this article please use the link below which will take you to the Copyright Clearance Center’s RightsLink service. You will be able to get a quick price and instant permission to reuse the content in many different ways.

Knowing the difference between health service evaluation, audit and research can be tricky especially for the novice researcher. Put simply, nursing research involves finding the answers to questions about “what nurses should do to help patients,” audit examines “whether nurses are doing this , and if not, why not,” 1 and service evaluation asks about “the effect of nursing care on patient experiences and outcomes .” In this paper, we aim to provide some tips to help guide you through the decision-making process as you begin to plan your evaluation, audit or research project. As a starting point box 1 provides key definitions for each type of project.

Box 1 Definitions of service evaluation, audit and research

▸ What is service evaluation?

Service evaluation seeks to assess how well a service is achieving its intended aims. It is undertaken to benefit the people using a particular healthcare service and is designed and conducted with the sole purpose of defining or judging the current service. 2

The results of service evaluations are mostly used to generate information that can be used to inform local decision-making.

▸ What is (clinical) audit?

The English Department of Health 3 states that:

Clinical audit involves systematically looking at the procedures used for diagnosis, care and treatment, examining how associated resources are used and investigating the effect care has on the outcome and quality of life for the patient.

Audit usually involves a quality improvement cycle that measures care against predetermined standards (benchmarking), takes specific actions to improve care and monitors ongoing sustained improvements to quality against agreed standards or benchmarks. 4 , 5

▸ What is research?

Research involves the attempt to extend the available knowledge by means of a systematically defensible process of enquiry. 6

How do I decide whether my project is service evaluation, audit or research?

- View inline

Key criteria to consider when deciding whether your project is service evaluation, audit or research 2 , 7

So if, for example, we were to explore management of children's postoperative pain we could:

Undertake a service evaluation and ask parents and children to complete a questionnaire about how well they think postoperative pain was managed for them during their experience on the paediatric unit.

Complete an audit by comparing postoperative pain management practices in the paediatric unit to current best practice guidelines using a standardised data collection tool.

Undertake a research project to identify the most effective postoperative pain management practices for children.

Online resource

The Health Research Authority in the UK has a useful online decision-making tool—see:

http://www.hra.nhs.uk/research-community/before-you-apply/determine-whether-your-study-is-research/

Applying ethical principles to service evaluation, audit and research

Ethical standards and patient privacy protection laws apply to all type of health research, service evaluation and audit processes. Research projects being carried out in healthcare will normally need approval from a research ethics committee or affiliated Institutional Review Board (IRB), as well as from the healthcare service site/s such as the hospital's Research and Development Department. If you are carrying out an audit you should register your project with the hospital's Audit Department or Quality and Safety Unit—this is mandatory in some organisations. If you are undertaking a service evaluation you should ensure the necessary permissions have been obtained at a local level or even regional level depending on the service.

A service evaluation or audit may not require specific approval from a research ethics committee or IRB but ethical principles must still be adhered to for the protection of patients. Ethical principles and Patient Protection laws that need to be followed:

Consent —It is important that potential participants are not coerced to take part in the project. They have the right to refuse to take part and to withdraw at any point.

Anonymity —Participants need to know whether their anonymity will be protected and if so how this will be carried out.

Data protection and privacy —You need to consider how you are going to ensure that your data is stored safely and that participant privacy is protected. In the UK you will adhere to the Data Protection Act (1998) and in the USA you will comply with the Health Insurance Privacy and Portability and Accountability Act (HIPPA; 1996) Privacy Rule.

Online resources

The Healthcare Quality Improvement Partnership (HQIP) has a useful guide in relation to applying ethical principles to service evaluations and audits. This can be downloaded from:

www.hqip.org.uk/assets/.../Audit-Research-Service-Evaluation.pdf

The U.S. Department of Health and Community Services, Office of Research Integrity has some useful resources on the principles of ethical research practice for a variety of roles in research http://ori.hhs.gov/

While researchers seek to provide evidence to guide practice, it often takes time for evidence to make the journey from ‘bench to bedside’. When organisations need answers fast, service evaluation and/or audit may be used to capture ‘real-time’ data and quickly move findings to create tangible practice change. An audit is like ‘taking the pulse’ of an organisation—it can produce results fast. As we check the organisational pulse against an expected range of normal we need to be sure we use the best approach to get an accurate reading so that our response is based on good data. This means no matter what the project scope or purpose, your project design should produce high-quality information about patient care and comply with ethical standards that protect patients.

- ↵ National Research Ethics Service (NRES) . Defining research . 2013 . http://www.nres.nhs.uk/EasySiteWeb/GatewayLink.aspx?alId=355 (accessed 22 Apr 2014) .

- ↵ Department of Health (2003) cited in What is clinical audit?. http://www.rcpsych.ac.uk/pdf/clinauditchap1.pdf (accessed 28 Apr 2014) .

- ↵ National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) . Principles for best practice in clinical audit . Oxford : Radcliffe Medical Press , 2002 .

- Gerrish K ,

- ↵ University Hospitals Bristol (2012) Service evaluation. http://bit.ly/1muGwOw (accessed 22 Apr 2014) .

Competing interests None.

Read the full text or download the PDF:

- Cancer Nursing Practice

- Emergency Nurse

- Evidence-Based Nursing

- Learning Disability Practice

- Mental Health Practice

- Nurse Researcher

- Nursing Children and Young People

- Nursing Management

- Nursing Older People

- Nursing Standard

- Primary Health Care

- RCN Nursing Awards

- Nursing Live

- Nursing Careers and Job Fairs

- CPD webinars on-demand

- --> Advanced -->

| | | |

- Clinical articles

- CPD articles

- CPD Quizzes

- Expert advice

- Clinical placements

- Study skills

- Clinical skills

- University life

- Person-centred care

- Career advice

- Revalidation

Evidence & Practice Previous Next

Practical guidance on undertaking a service evaluation, pam moule professor of health services research (service evaluation), faculty of health and life sciences, university of west of england, julie armoogum senior lecturer, faculty of health and life sciences, university of west of england, emily dodd clinical trials co-ordinator, faculty of health and life sciences, university of west of england, anne-laure donskoy research partner and survivor researcher, faculty of health and life sciences, university of west of england, emma douglass senior lecturer, faculty of health and life sciences, university of west of england, julie taylor senior lecturer, faculty of health and life sciences, university of west of england, pat turton senior lecturer, faculty of health and life sciences, university of west of england.

This article describes the basic principles of evaluation, focusing on the evaluation of healthcare services. It emphasises the importance of evaluation in the current healthcare environment and the requirement for nurses to understand the essential principles of evaluation. Evaluation is defined in contrast to audit and research, and the main theoretical approaches to evaluation are outlined, providing insights into the different types of evaluation that may be undertaken. The essential features of preparing for an evaluation are considered, and guidance provided on working ethically in the NHS. It is important to involve patients and the public in evaluation activity, offering essential guidance and principles of best practice. The authors discuss the main challenges of undertaking evaluations and offer recommendations to address these, drawing on their experience as evaluators.

Nursing Standard . 30, 45, 46-51. doi: 10.7748/ns.2016.e10277

All articles are subject to external double-blind peer review and checked for plagiarism using automated software.

None declared.

Received: 14 September 2015

Accepted: 17 December 2015

evaluation - evaluation methods - healthcare evaluation - service evaluation - patient involvement - public involvement

User not found

Want to read more?

Already have access log in, 3-month trial offer for £5.25/month.

- Unlimited access to all 10 RCNi Journals

- RCNi Learning featuring over 175 modules to easily earn CPD time

- NMC-compliant RCNi Revalidation Portfolio to stay on track with your progress

- Personalised newsletters tailored to your interests

- A customisable dashboard with over 200 topics

Alternatively, you can purchase access to this article for the next seven days. Buy now

Are you a student? Our student subscription has content especially for you. Find out more

06 July 2016 / Vol 30 issue 45

TABLE OF CONTENTS

DIGITAL EDITION

- LATEST ISSUE

- SIGN UP FOR E-ALERT

- WRITE FOR US

- PERMISSIONS

Share article: Practical guidance on undertaking a service evaluation

We use cookies on this site to enhance your user experience.

By clicking any link on this page you are giving your consent for us to set cookies.

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Starting the research process

- How to Write a Research Proposal | Examples & Templates

How to Write a Research Proposal | Examples & Templates

Published on October 12, 2022 by Shona McCombes and Tegan George. Revised on November 21, 2023.

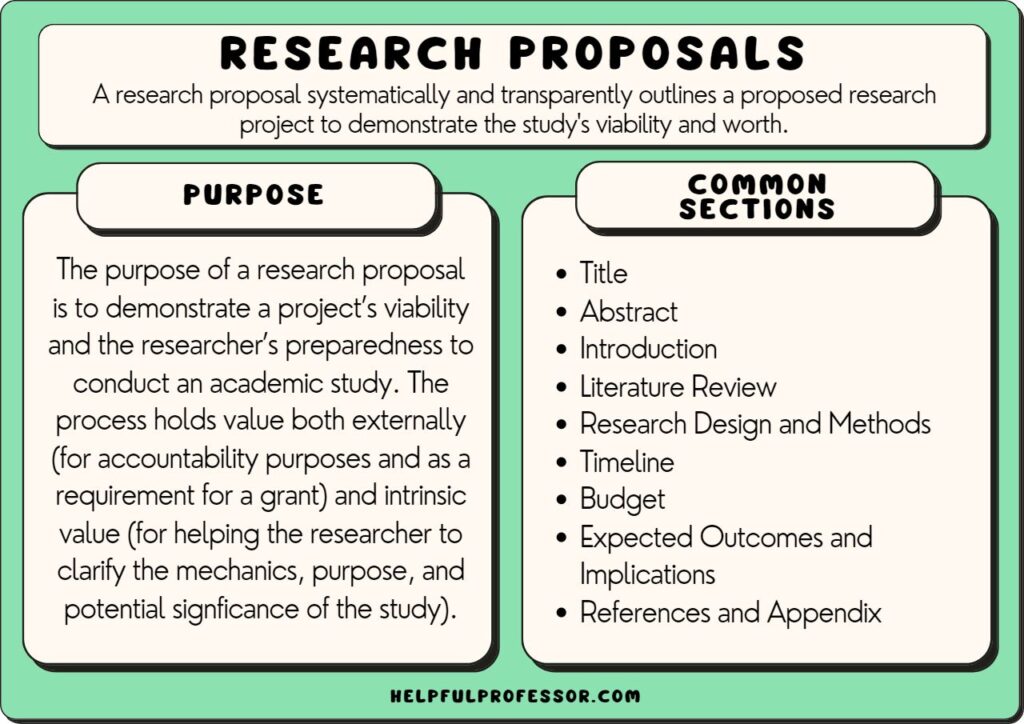

A research proposal describes what you will investigate, why it’s important, and how you will conduct your research.

The format of a research proposal varies between fields, but most proposals will contain at least these elements:

Introduction

Literature review.

- Research design

Reference list

While the sections may vary, the overall objective is always the same. A research proposal serves as a blueprint and guide for your research plan, helping you get organized and feel confident in the path forward you choose to take.

Table of contents

Research proposal purpose, research proposal examples, research design and methods, contribution to knowledge, research schedule, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about research proposals.

Academics often have to write research proposals to get funding for their projects. As a student, you might have to write a research proposal as part of a grad school application , or prior to starting your thesis or dissertation .

In addition to helping you figure out what your research can look like, a proposal can also serve to demonstrate why your project is worth pursuing to a funder, educational institution, or supervisor.

| Show your reader why your project is interesting, original, and important. | |

| Demonstrate your comfort and familiarity with your field. Show that you understand the current state of research on your topic. | |

| Make a case for your . Demonstrate that you have carefully thought about the data, tools, and procedures necessary to conduct your research. | |

| Confirm that your project is feasible within the timeline of your program or funding deadline. |

Research proposal length

The length of a research proposal can vary quite a bit. A bachelor’s or master’s thesis proposal can be just a few pages, while proposals for PhD dissertations or research funding are usually much longer and more detailed. Your supervisor can help you determine the best length for your work.

One trick to get started is to think of your proposal’s structure as a shorter version of your thesis or dissertation , only without the results , conclusion and discussion sections.

Download our research proposal template

Receive feedback on language, structure, and formatting

Professional editors proofread and edit your paper by focusing on:

- Academic style

- Vague sentences

- Style consistency

See an example

Writing a research proposal can be quite challenging, but a good starting point could be to look at some examples. We’ve included a few for you below.

- Example research proposal #1: “A Conceptual Framework for Scheduling Constraint Management”

- Example research proposal #2: “Medical Students as Mediators of Change in Tobacco Use”

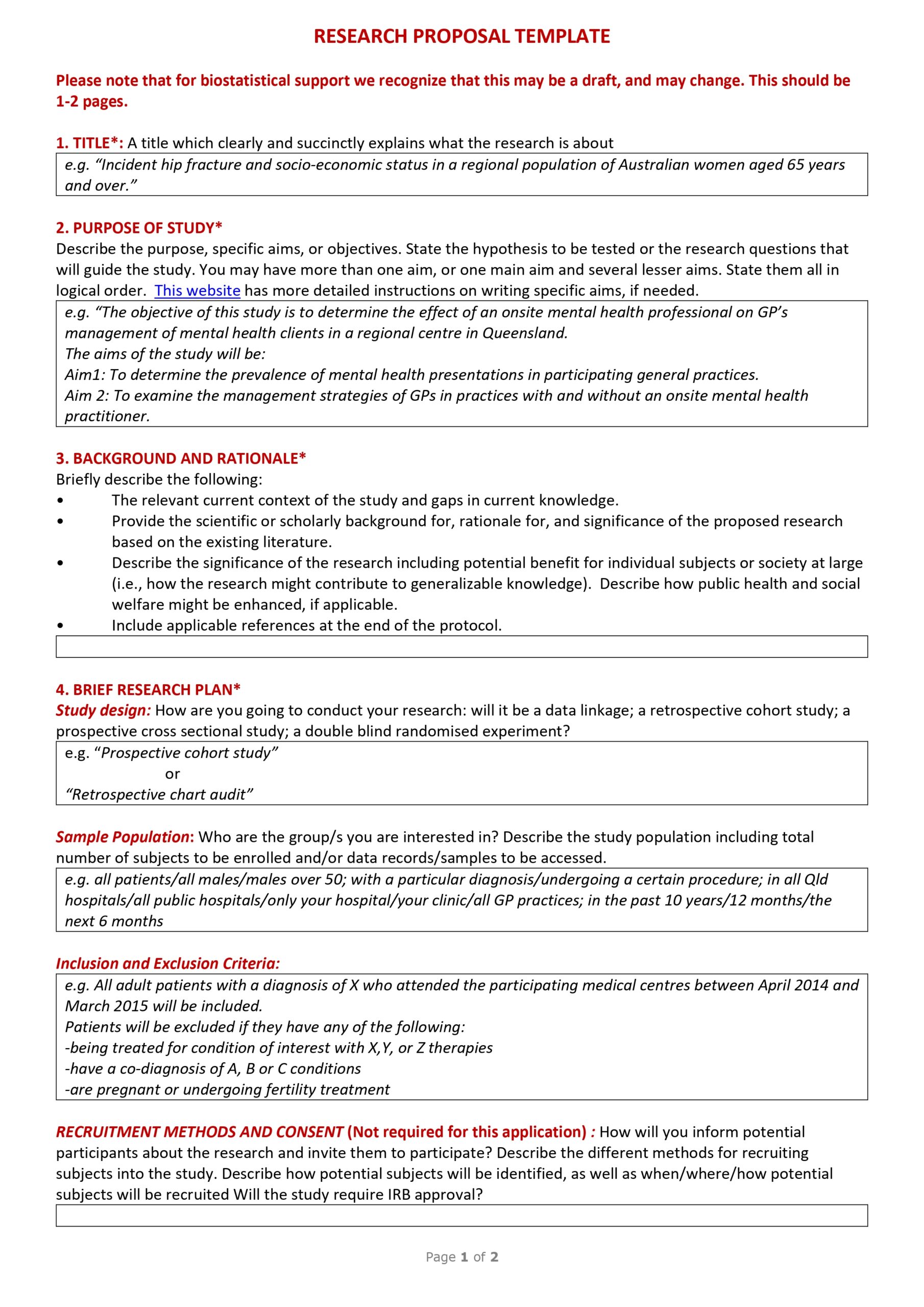

Like your dissertation or thesis, the proposal will usually have a title page that includes:

- The proposed title of your project

- Your supervisor’s name

- Your institution and department

The first part of your proposal is the initial pitch for your project. Make sure it succinctly explains what you want to do and why.

Your introduction should:

- Introduce your topic

- Give necessary background and context

- Outline your problem statement and research questions

To guide your introduction , include information about:

- Who could have an interest in the topic (e.g., scientists, policymakers)

- How much is already known about the topic

- What is missing from this current knowledge

- What new insights your research will contribute

- Why you believe this research is worth doing

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

As you get started, it’s important to demonstrate that you’re familiar with the most important research on your topic. A strong literature review shows your reader that your project has a solid foundation in existing knowledge or theory. It also shows that you’re not simply repeating what other people have already done or said, but rather using existing research as a jumping-off point for your own.

In this section, share exactly how your project will contribute to ongoing conversations in the field by:

- Comparing and contrasting the main theories, methods, and debates

- Examining the strengths and weaknesses of different approaches

- Explaining how will you build on, challenge, or synthesize prior scholarship

Following the literature review, restate your main objectives . This brings the focus back to your own project. Next, your research design or methodology section will describe your overall approach, and the practical steps you will take to answer your research questions.

| ? or ? , , or research design? | |

| , )? ? | |

| , , , )? | |

| ? |

To finish your proposal on a strong note, explore the potential implications of your research for your field. Emphasize again what you aim to contribute and why it matters.

For example, your results might have implications for:

- Improving best practices

- Informing policymaking decisions

- Strengthening a theory or model

- Challenging popular or scientific beliefs

- Creating a basis for future research

Last but not least, your research proposal must include correct citations for every source you have used, compiled in a reference list . To create citations quickly and easily, you can use our free APA citation generator .

Some institutions or funders require a detailed timeline of the project, asking you to forecast what you will do at each stage and how long it may take. While not always required, be sure to check the requirements of your project.

Here’s an example schedule to help you get started. You can also download a template at the button below.

Download our research schedule template

| Research phase | Objectives | Deadline |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Background research and literature review | 20th January | |

| 2. Research design planning | and data analysis methods | 13th February |

| 3. Data collection and preparation | with selected participants and code interviews | 24th March |

| 4. Data analysis | of interview transcripts | 22nd April |

| 5. Writing | 17th June | |

| 6. Revision | final work | 28th July |

If you are applying for research funding, chances are you will have to include a detailed budget. This shows your estimates of how much each part of your project will cost.

Make sure to check what type of costs the funding body will agree to cover. For each item, include:

- Cost : exactly how much money do you need?

- Justification : why is this cost necessary to complete the research?

- Source : how did you calculate the amount?

To determine your budget, think about:

- Travel costs : do you need to go somewhere to collect your data? How will you get there, and how much time will you need? What will you do there (e.g., interviews, archival research)?

- Materials : do you need access to any tools or technologies?

- Help : do you need to hire any research assistants for the project? What will they do, and how much will you pay them?

If you want to know more about the research process , methodology , research bias , or statistics , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

Methodology

- Sampling methods

- Simple random sampling

- Stratified sampling

- Cluster sampling

- Likert scales

- Reproducibility

Statistics

- Null hypothesis

- Statistical power

- Probability distribution

- Effect size

- Poisson distribution

Research bias

- Optimism bias

- Cognitive bias

- Implicit bias

- Hawthorne effect

- Anchoring bias

- Explicit bias

Once you’ve decided on your research objectives , you need to explain them in your paper, at the end of your problem statement .

Keep your research objectives clear and concise, and use appropriate verbs to accurately convey the work that you will carry out for each one.

I will compare …

A research aim is a broad statement indicating the general purpose of your research project. It should appear in your introduction at the end of your problem statement , before your research objectives.

Research objectives are more specific than your research aim. They indicate the specific ways you’ll address the overarching aim.

A PhD, which is short for philosophiae doctor (doctor of philosophy in Latin), is the highest university degree that can be obtained. In a PhD, students spend 3–5 years writing a dissertation , which aims to make a significant, original contribution to current knowledge.

A PhD is intended to prepare students for a career as a researcher, whether that be in academia, the public sector, or the private sector.

A master’s is a 1- or 2-year graduate degree that can prepare you for a variety of careers.

All master’s involve graduate-level coursework. Some are research-intensive and intend to prepare students for further study in a PhD; these usually require their students to write a master’s thesis . Others focus on professional training for a specific career.

Critical thinking refers to the ability to evaluate information and to be aware of biases or assumptions, including your own.

Like information literacy , it involves evaluating arguments, identifying and solving problems in an objective and systematic way, and clearly communicating your ideas.

The best way to remember the difference between a research plan and a research proposal is that they have fundamentally different audiences. A research plan helps you, the researcher, organize your thoughts. On the other hand, a dissertation proposal or research proposal aims to convince others (e.g., a supervisor, a funding body, or a dissertation committee) that your research topic is relevant and worthy of being conducted.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

McCombes, S. & George, T. (2023, November 21). How to Write a Research Proposal | Examples & Templates. Scribbr. Retrieved August 12, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/research-process/research-proposal/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, how to write a problem statement | guide & examples, writing strong research questions | criteria & examples, how to write a literature review | guide, examples, & templates, "i thought ai proofreading was useless but..".

I've been using Scribbr for years now and I know it's a service that won't disappoint. It does a good job spotting mistakes”

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- My Bibliography

- Collections

- Citation manager

Save citation to file

Email citation, add to collections.

- Create a new collection

- Add to an existing collection

Add to My Bibliography

Your saved search, create a file for external citation management software, your rss feed.

- Search in PubMed

- Search in NLM Catalog

- Add to Search

Service evaluation: A grey area of research?

Affiliation.

- 1 The University of Edinburgh, UK.

- PMID: 29262740

- DOI: 10.1177/0969733017742961

The National Health Service in the United Kingdom categorises research and research-like activities in five ways, such as 'service evaluation', 'clinical audit', 'surveillance', 'usual practice' and 'research'. Only activities classified as 'research' require review by the Research Ethics Committees. It is argued, in this position paper, that the current governance of research and research-like activities does not provide sufficient ethical oversight for projects classified as 'service evaluation'. The distinction between the categories of 'research' and 'service evaluation' can be a grey area. A considerable percentage of studies are considered as non-research and therefore not eligible to be reviewed by the Research Ethics Committee, which scrutinises research proposals rigorously to ensure they conform to established ethical standards, protecting research participants from harm, preserving their rights and providing reassurance to the public. This article explores the ethical discomfort potentially inherent in the activity currently labelled as 'service evaluation'.

Keywords: Ethics principles; ethics review; research; research ethics; service evaluation.

PubMed Disclaimer

Similar articles

- Views of National Health Service (NHS) Ethics Committee members on how education research should be reviewed. Brown J, Ryland I, Howard J, Shaw N. Brown J, et al. Med Teach. 2007 Mar;29(2-3):225-30. doi: 10.1080/01421590701300179. Med Teach. 2007. PMID: 17701637

- Achieving an ethical health service: the need for information. HM Queen Elizabeth the Queen Mother Lecture. Holland W. Holland W. J R Coll Physicians Lond. 1995 Jul-Aug;29(4):325-34. J R Coll Physicians Lond. 1995. PMID: 7473329 Free PMC article. No abstract available.

- Reconsidering 'ethics' and 'quality' in healthcare research: the case for an iterative ethical paradigm. Stevenson FA, Gibson W, Pelletier C, Chrysikou V, Park S. Stevenson FA, et al. BMC Med Ethics. 2015 May 8;16:21. doi: 10.1186/s12910-015-0004-1. BMC Med Ethics. 2015. PMID: 25952678 Free PMC article.

- Ethics approval, guarantees of quality and the meddlesome editor. Long T, Fallon D. Long T, et al. J Clin Nurs. 2007 Aug;16(8):1398-404. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2006.01918.x. J Clin Nurs. 2007. PMID: 17655528 Review.

- Research governance and ethics: a resource for novice researchers. Fontenla M, Rycroft-Malone J. Fontenla M, et al. Nurs Stand. 2006 Feb 15-21;20(23):41-6. doi: 10.7748/ns2006.02.20.23.41.c4069. Nurs Stand. 2006. PMID: 16514927 Review.

- Impact of Digital Inclusion Initiative to Facilitate Access to Mental Health Services: Service User Interview Study. Oliver A, Chandler E, Gillard JA. Oliver A, et al. JMIR Ment Health. 2024 Jul 26;11:e51315. doi: 10.2196/51315. JMIR Ment Health. 2024. PMID: 39058547 Free PMC article.

- The well now course: a service evaluation of a health gain approach to weight management. Clarke F, Archibald D, MacDonald V, Huc S, Ellwood C. Clarke F, et al. BMC Health Serv Res. 2021 Aug 30;21(1):892. doi: 10.1186/s12913-021-06836-z. BMC Health Serv Res. 2021. PMID: 34461890 Free PMC article.

- Revising ethical guidance for the evaluation of programmes and interventions not initiated by researchers. Watson SI, Dixon-Woods M, Taylor CA, Wroe EB, Dunbar EL, Chilton PJ, Lilford RJ. Watson SI, et al. J Med Ethics. 2020 Jan;46(1):26-30. doi: 10.1136/medethics-2018-105263. Epub 2019 Sep 3. J Med Ethics. 2020. PMID: 31481472 Free PMC article.

- Search in MeSH

LinkOut - more resources

Full text sources.

- Ovid Technologies, Inc.

Other Literature Sources

- scite Smart Citations

- Citation Manager

NCBI Literature Resources

MeSH PMC Bookshelf Disclaimer

The PubMed wordmark and PubMed logo are registered trademarks of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). Unauthorized use of these marks is strictly prohibited.

Log in using your username and password

- Search More Search for this keyword Advanced search

- Latest content

- Current issue

- BMJ Journals

You are here

- Volume 24, Issue 5

- What to expect when you're evaluating healthcare improvement: a concordat approach to managing collaboration and uncomfortable realities

- Article Text

- Article info

- Citation Tools

- Rapid Responses

- Article metrics

- http://orcid.org/0000-0003-3604-2897 Liz Brewster ,

- Emma-Louise Aveling ,

- Graham Martin ,

- Carolyn Tarrant ,

- Mary Dixon-Woods ,

- The Safer Clinical Systems Phase 2 Core Group Collaboration & Writing Committee

- Correspondence to Dr Liz Brewster, Department of Health Sciences, University of Leicester, Leicester LE1 6TP, UK; eb240{at}le.ac.uk

Evaluation of improvement initiatives in healthcare is essential to establishing whether interventions are effective and to understanding how and why they work in order to enable replication. Although valuable, evaluation is often complicated by tensions and friction between evaluators, implementers and other stakeholders. Drawing on the literature, we suggest that these tensions can arise from a lack of shared understanding of the goals of the evaluation; confusion about roles, relationships and responsibilities; data burdens; issues of data flows and confidentiality; the discomforts of being studied and the impact of disappointing or otherwise unwelcome results. We present a possible approach to managing these tensions involving the co-production and use of a concordat. We describe how we developed a concordat in the context of an evaluation of a complex patient safety improvement programme known as Safer Clinical Systems Phase 2. The concordat development process involved partners (evaluators, designers, funders and others) working together at the outset of the project to agree a set of principles to guide the conduct of the evaluation. We suggest that while the concordat is a useful resource for resolving conflicts that arise during evaluation, the process of producing it is perhaps even more important, helping to make explicit unspoken assumptions, clarify roles and responsibilities, build trust and establish open dialogue and shared understanding. The concordat we developed established some core principles that may be of value for others involved in evaluation to consider. But rather than seeing our document as a ready-made solution, there is a need for recognition of the value of the process of co-producing a locally agreed concordat in enabling partners in the evaluation to work together effectively.

- Quality improvement

- Patient safety

- Evaluation methodology

- Quality improvement methodologies

This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjqs-2014-003732

Statistics from Altmetric.com

Request permissions.

If you wish to reuse any or all of this article please use the link below which will take you to the Copyright Clearance Center’s RightsLink service. You will be able to get a quick price and instant permission to reuse the content in many different ways.

Introduction

Meaningful evaluation has an essential role in the work of improving healthcare, especially in enabling learning to be shared. 1 Evaluations typically seek to identify the aims of an intervention or programme, find measurable indicators of achievement, collect data on these indicators and assess what was achieved against the original aims. 2 Evaluating whether a programme works is not necessarily the only purpose of evaluation, however: how and why may be equally important questions, 3 , 4 especially in enabling apparently successful interventions to be reproduced. 5 Despite the potential benefits of such efforts, and the welcome given to evaluation by some who run programmes, the literature on programme evaluation has long acknowledged that evaluation can be a source of tension, friction and confusion of purpose: [Evaluation] involves a balancing act between competing forces. Paramount among these is the inherent conflict between the requirements of systematic inquiry and data collection associated with evaluation research and the organizational imperatives of a social program devoted to delivering services and maintaining essential routine activities. 6

Healthcare is no exception to the general problems characteristic of programme evaluation: the concerns and interests of the different parties involved in an improvement project and its associated evaluation may not always converge. These parties may include the designers and implementers of interventions (without whose improvement work there would be nothing to evaluate), the evaluators (who may be a heterogeneous mix of different professional groups - including health professionals and others - or academics from different disciplines) and sometimes funders (who may be funding either the intervention, the evaluation or both). Each may have different goals, perspectives, expectations, priorities and interests, professional languages and norms of practice, and they may have very distinct accountabilities and audiences for their work. As a result, evaluation work may—and in fact, often does—present challenges for all involved, ranging from practicalities such as arranging access to data, through conceptual disagreements about the programme and what it is trying to achieve, to concerns about the impartiality and competence of the evaluation team, widely divergent definitions of success and many others. 6 Given that it is not unlikely these challenges will occur, the important question is how they can optimally be anticipated and managed. 7 , 8

This article seeks to make a practical contribution by presenting a possible approach to minimising the tensions. Specifically, we propose the co-production and use of a concordat —a mutually agreed compact between all parties, which articulates a set of principles to guide the conduct of the evaluation. The article proceeds in two parts. First, we identify the kinds of challenge often faced in the design, running and evaluation of an improvement programme in healthcare. Second, we present an example of the development of a concordat used in the evaluation of a major improvement project.

Challenges in conducting programme evaluations

Areas of possible tension and challenge in programme evaluation identified in the literature.

Securing full consensus on the specifics of evaluation objectives 34

Unpacking contrasting interpretations about what and who the evaluation is for 6

A desire on the part of evaluators to fix the goals for improvement programmes early in the evaluation process 35

Evolution of interventions (intentionally or unintentionally) during implementation 36 and ongoing negotiation about evaluation scope in relation to implementation evolution 37

Fear of evaluation being used for performance management 15

Mismatched interpretations of stakeholders’ own role and other partners’ roles 12 , 14

An interpretation of evaluators as friends or confidants, risking a subsequent sense of betrayal 16

A lack of shared language or understanding if some partners lack familiarity with the methodological paradigm or data collection tools being proposed 13

Conflicts between the burden of evaluation data collection and the work of the programme 2

Previous experiences of the dubious value of evaluation leading to disengagement with current evaluation work 17

Tensions between an imperative to feedback findings and to respect principles of anonymity and confidentiality 38

Encountering the ‘uncomfortable reality’ that a service or intervention is not performing as planned or envisaged and objectives have not been met 18

Negotiations with gatekeepers about access to complete and accurate data in a timely fashion

A reluctance to share evaluation findings if they are seen as against the ‘organisational zeitgeist’ 20 or threaten identity and reputational claims 21

Pressure from partners, research sponsors or funders to alter the content or scope of the evaluation, 20 or to delay their publication 22

A critical first task for all parties is to therefore clarify what is to be achieved through evaluation. This allows an appropriate evaluation design to be formulated, but is also central to establishing a shared vision to underpin activity. This negotiation of purpose may be more or less formal, 11 but should be undertaken. The task is to settle questions about purpose and scope, remembering that agreements about these may unravel over the course of the activity. 12 Constant review and revisiting of the goals of the evaluation (as well as the goals of the improvement programme) may therefore be necessary to maintain dialogue and avoid unwarranted drift.

These early discussions are especially important in ensuring that all parties understand the methods and data collection procedures being used in the evaluation. 13 A lack of shared language and understanding may lead to confusion over why particular methods are being used, generating uncertainties or suspicion and undermining willingness to cooperate. Regardless of what form it takes, the burden of data collection can be off-putting for those being evaluated and those performing the evaluation. If the evaluation itself is too demanding, there may be conflicts between its requirements and doing the work of the programme. 2 For partner organisations, collecting data for evaluation may not seem as much of a priority as delivery, and the issue of who gets to control and benefit from the data they have worked so hard to collect may be difficult to resolve.

Even when agreement on goals and scope is reached early on and remains intact, complex evaluations create a multiplicity of possible lines of communication and accountability, as well as ambiguity about roles. Though the role of each party in a programme evaluation may seem self-evident (eg, one funds, one implements, one evaluates), in practice different parties may have mismatched interpretations both of their own role and of others’. Such blind spots can fatally derail collaborative efforts. 12 The role of the evaluator may be an especially complex one, viewed in different ways by different parties. 14 Outcomes-focused aspects of evaluation—aimed at assessing degree of success in achieving goals—may cast evaluators as ‘performance managers’. 15 But the process-focused aspects of evaluation—particularly where they involve frequent contact between evaluators and evaluated, as is usually the case with ethnographic study—may make evaluators seem like friendly confidants, risking a subsequent sense of betrayal. 16 Thus, evaluators may be seen as critical friends, co-investigators, facilitators or problem solvers by some, but also as unwelcome intruders who sit in judgement but do not get their hands dirty in the real work of delivering the programme and who have influence without responsibility.

Uncertainties about what information should be shared with whom, when and under what conditions may provide a further source of ethical dilemma, especially when unspoken assumptions and expectations are breached, damaging trust and undermining cooperative efforts. Evaluators must often abide by both the imperative to feedback findings to other stakeholders (especially, perhaps, the funders and clients of the evaluation) and to respect principles of anonymity and confidentiality in determining the limits of what can be fed back, to whom and in how much detail. For these reasons, role perceptions and understandings about information exchange (content and direction) need to be surfaced early in the programme—and revisited throughout—to avoid threats to an honest, critical and uncompromised evaluation process. This is especially important given the asymmetry that may arise between the various parties, which can lead to tensions about who is in charge and on what authority.

Sometimes, though perhaps not often, the challenges are such that implementers may feel that obstructing evaluation is more in line with their organisational interests. They may, for example, frustrate attempts to evaluate by providing inaccurate, incomplete or tardy data (quantitative or qualitative) or, where they are able to play the role of ‘gatekeeper’, simply deny access to data or key members of staff. A lack of engagement with the process may be fuelled by previous experiences of evaluation that was felt to be time-consuming or of dubious value. 17

Tensions do not, of course, end when the programme and evaluation are complete, and may indeed intensify when the results are published. Those involved in designing, delivering and funding a programme may set out with great optimism; they may invest huge energy, efforts and resource in a programme; they may be convinced of its benefits and success and they may want to be recognised and congratulated on their hard work and achievement. When evaluation findings are positive, they are likely to be welcomed. Robust evidence of the effectiveness of an intervention can be extremely valuable in providing weight to arguments for its uptake and spread, and positive findings from independent evaluation of large-scale improvement programmes help legitimise claims to success. But not every project succeeds, and an evaluation may result in some participants being confronted with the uncomfortable reality that their service or their intervention has not performed as well as they had hoped. 18 Such findings may provoke reactions of disappointment, anger and challenge: ‘for every evaluation finding there is equal and opposite criticism’. 19

When a programme falls short of realising its goals, analysis of the reasons for failure can produce huge net benefits for the wider community, not least in ensuring that future endeavours do not repeat the same mistakes. 2 But recognising this value can be difficult given the immediate disappointment that comes with failure. If the evaluation—and the resulting publications—does not present the organisation(s) involved in the intervention in a positive light, there may be a reluctance to ‘wash dirty linen in public’ 2 and resistance to the implications of findings, 20 especially where they threaten reputation. 21 Evaluators themselves may not be immune to pressures to compromise their impartiality. The literature contains cautionary examples of pressure from partners or research sponsors who wish to direct the content of the report or analysis, 20 or coercion from funders to limit the scope of evaluation, distort results or critically delay their publication. 22

A possible solution: developing a concordat

Managing risks of conflict and tension in the evaluation of improvement programmes.

All parties should agree on the purpose and scope of the evaluation upfront, but recognise that both may mutate over time and need to be revisited

An explicit statement of roles may ensure that understandings of the division of labour within an evaluation—and the responsibilities and relationships that imply—are shared

The expectations placed on each party in relation to data collection should be reasonable and feasible, and the methodological approach (in its basic principles) should be understood by all parties

Clear terms of reference concerning disclosure, dissemination and the limits of confidentiality are necessary from the start

All efforts should be made to avoid implementers experiencing discomfort about being studied: through ensuring all parties are fully briefed about the evaluation; sharing formative findings and ensuring appropriate levels of anonymity in reporting findings

Commitment to learning for the greatest collective benefit is the overriding duty of all parties involved—it follows from this that all parties should make an explicit commitment to ensuring sincere, honest and impartial reporting of evaluation findings

The programme we discuss, known as Safer Clinical Systems Phase 2, was a complex intervention in which eight organisations were trained to apply a new approach (adapted from high-risk industries) to the detection and management of risk in clinical settings. 26 The work was highly customised to the particularities of these settings. The programme involved a complicated nexus of actors, including the funder (the Health Foundation, a UK healthcare improvement charitable foundation); the technical support team (based at the University of Warwick Medical School), who designed the approach and provided training and support for the participating sites over a 2-year period; the eight healthcare organisations (‘implementers’) and the evaluation team (itself a three-university partnership led by the University of Leicester).

Developing the concordat and its content

The evaluation team drew on the literature and previous experience to anticipate potential points of conflict or frustration and to identify principles and values that could govern the relationships and promote cooperation. These were drawn together into the first draft of a document that we called a ‘concordat’. The evaluation team came up with the initial draft, which was then subject to extensive comment, discussion, refinement and revision by the technical support team and funders. The document went through multiple drafts based on feedback, including several meetings where evaluators, technical team and funders came up with possible areas of conflict and possible scenarios illustrating tensions, and tested these against the concordat. Once the final draft was agreed, it was signed by all three parties and shared with the participating sites.

The concordat in outline

Goals and values —outlining the partners and their commitment to the programme goal, shared learning, respect for dignity and integrity and open dialogue

Responsibilities of the evaluation team —summarising the purpose of the evaluation, making a commitment to accuracy in representation and reporting and seeking to minimise the burden on partners

Responsibilities of the support team —a synopsis of the remit of one partner's role in relation to the evaluation team and their agreed interaction

Responsibilities of participating sites— outlining how the sites will facilitate access to data for the evaluation team

Data collection— agreeing steps to minimise the burden of data collection on all partners and to share data as appropriate

Ethical issues —summarising issues about confidentiality, data security and working within appropriate ethical and governance frameworks

Publications —confirming a commitment to timely publication of findings, paying particular attention to the possibility of negative or critical findings

Feedback —outlining how formative feedback should be provided, received and actioned by appropriate partners

The concordat then sets out the roles and responsibilities of each party, including, for example, an obligation to be even-handed for the evaluation team, and the commitment to sharing information openly on the part of the technical support team ( box 3 ). The concordat also articulated the relationships between the different parties, emphasising the importance of critical distance and stressing that this was not a relationship of performance management. The concordat further sought to address potential disagreements relating to the measures used in the evaluation. Rather than delineate an exhaustive list of what those methods and data would be, the concordat sets out the process through which measures would be negotiated and determined, and made explicit the principles concerning requests for and provision of data that would underpin this process (eg, the evaluation team should minimise duplicative demands for data by the evaluation team, and the participating sites should provide timely and accurate data).

The values and ethical imperatives governing action and interactions were also made explicit; for example, arrangements around confidentiality, anonymity and dissemination were addressed, including expectations relating to authorship of published outputs. Principles relating to research governance and feedback sought both to mitigate unease at the prospect of evaluation while also enshrining certain inalienable principles that are required for high-quality evaluation: for example, it committed all parties to sharing outputs ahead of publication, but it also protected the impartiality of the evaluation team by making clear that they had the final say in the interpretation and presentation of evaluation findings (though this did not preclude other partners from publishing their own work). Importantly, the concordat sets out a framework that all parties committed to following if disputes did arise. These principles were invoked on a number of occasions during the Safer Clinical Systems evaluation, for example, when trying to reach agreement on measurement or to resolve ambiguities in the roles of the evaluation and support teams. The concordat was also invaluable in ensuring that boundaries and expectations did not have to be continually re-negotiated in response to organisational turbulence, given that the programme experienced frequent changes of personnel over its course.

Challenges in developing and using the concordat

Of course, neither the process nor the outcome of the concordat for this evaluation was without wrinkles. Some issues arose that had not been anticipated, and some tensions encountered from the start of the programme continued to cause difficulties. These challenges were in some respects unique to this particular context, but may provide general lessons to inform future evaluation work. For instance, the technical support team was charged with undertaking ‘learning capture’, which was not always easy to distinguish from evaluation, and it proved difficult to maintain clear boundaries about this scope. Future projects would benefit from earlier clarification of scope and roles.

The concordat took considerable time to develop and agree—around 6 months—in part because the process for developing the concordat was being worked on at the same time as developing the concordat itself. One consequence of this was that the participating sites (the implementers) were only given the opportunity to comment rather than engage as full partners. Future iterations should attempt to involve all parties earlier. We share this concordat and its process of development in part to facilitate the speedier creation of future similar agreements.

The concordat as a solution: how does developing a concordat support effective collaborative activity?

The development of a concordat makes concrete the principles underpinning evaluation as a collaborative activity, and the concordat itself has value as a symbolic, practical and actionable tool for setting expectations and supporting conflict resolution.

The concordat as a document provides mutually agreed foundational principles which can be revisited when difficulties arise. In this sense, the concordat has value as a guide and point of reference. 21 It also serves a symbolic function, in that it signals recognition—by all parties—of the centrality and importance of collaboration and a shared commitment to the process of evaluation. Formalising a collaborative agreement between parties, in the form of a non-binding contract, has the potential to promote a cooperative orientation among the parties involved and build trust. 27 , 28 That the concordat is written and literally signed up to by all parties is important, as this institutionalisation of the concordat makes it less susceptible to distortion over time and better able to ensure that mutual understanding is more than superficial. Further, because it is explicitly not a contract, it offers a means of achieving agreement on core principles, goals and values separate from any legal commitments, and it leaves open the possibility of negotiation and renegotiation.

Much of the value in developing a concordat, however, lies in the process of co-production by all parties—a case of ‘all plans are useless, but planning is indispensable’. Though we did not directly evaluate its use, we feel that its development had a number of benefits for all stakeholders. First, rather than waiting for contradictions to materialise as disruptive conflicts that impede the evaluation, the process of discussing and (re)drafting a concordat offers an opportunity to anticipate, identify and make explicit differences in interpretations and perspectives on various aspects of the joint activity. Each party must engage in a process of surfacing and reflecting on their own assumptions, interpretations and interests, and sharing these with other parties. This allows difference and alternative interpretations to be openly acknowledged (rather than denied or ignored)—a respectful act of recognition and a prerequisite of open dialogue. 29 , 30 Thus, the production of the concordat acts as a mechanism for establishing the kind of open dialogue and shared understanding so commonly exhorted.

Second, by explicitly reflecting on and articulating the various roles and contributions of each party, the concordat-building process helps to foreground the contribution that each partner makes to the project and its evaluation, showing that all are interdependent and necessary. 7 This emphasis on the distributed nature of contributions can help to offset the dominance of asymmetrical, hierarchical positionings (such as evaluator and evaluated, funder and funded, for example). 21 It can therefore enable all those involved to see the opportunities as well as the challenges within an evaluation process, and reinforce a shared understanding of the value of a systematic, well-conducted evaluation.

Conclusions

Programme evaluation is important to advancing the science of improvement. But it is unrealistic to suppose that there will be no conflict within an evaluation situation involving competing needs, priorities and interests: the management of these tensions is key to ensuring that a productive collaboration is maintained. Drawing on empirical and theoretical literature, and our own experience, we have outlined a practical approach—co-production and use of a concordat—designed to optimise and sustain the collaboration on which evaluation activity depends. A concordat is no substitute for sincere, faithful commitment to an ethic of learning on the part of all involved parties, 31 and even with goodwill from all parties, it may not succeed in eliminating discord entirely. Nonetheless, in complex, challenging situations, having a clear set of values and principles that all parties have worked through is better than not having one.

A concordat offers a useful component in planning an evaluation that runs smoothly by providing a framework for both anticipating and resolving conflict in collaborative activity. This approach is premised on recognition that evaluation depends on collaboration between diverse parties, and is therefore, by its collective nature, prone to tension about multiple areas of practice. 32 Key to the potential of a concordat is its value, first, as an institutionalised agreement to be used as a framework for conflict resolution during evaluation activity, and, second, as a mechanism through which potential conflicts can be anticipated, made explicit and acknowledged before they arise, thereby establishing dialogue and a shared understanding of the purpose, roles, methods and procedures entailed in the evaluation.

The concordat we developed for the Safer Clinical Systems evaluation (see online supplementary appendix 1) is not intended to be used directly as template for others, although, with appropriate acknowledgement, its principles could potentially be adapted and used. Understanding the principles behind the use of a concordat (how and why it works) is critical. 33 In accordance with the rationale behind the concordat approach, we do not advocate that other collaborations simply adopt this example of a concordat ‘as is’. To do so would eliminate a crucial component of its value—the process of collective co-production. The process of articulating potential challenges in the planned collaboration, and testing drafts of the concordat against these, is particularly important in helping to uncover the implicit assumptions and expectations held by different parties, and to identify ambiguities about roles and relationships. All parties must be involved, in order to secure local ownership and capitalise on the opportunity to anticipate and surface tensions, establish dialogue and a shared vision and foreground the positive interdependence of all parties.

Acknowledgments

We thank all of the many organisations and individuals who participated in this programme for their generosity and support, and our collaborators and the advisory group for the programme. Mary Dixon-Woods thanks the University of Leicester for grant of study leave and the Dartmouth Institute for Health Policy and Clinical Practice for hosting her during the writing of this paper.

- Dixon-Woods M ,

- Aveling EL , et al

- Davidoff F ,

- Leviton L , et al

- Hoffmann TC ,

- Glasziou PP ,

- Boutron I , et al

- Stevahn L ,

- Van Elteren AHG ,

- Nierse CJ , et al

- Mero-Jaffe I

- Sharkey S ,

- Van Vlaerenden H

- Gillespie A ,

- Richardson B

- Schwandt TA ,

- Martin GP ,

- Hendy J , et al

- Desautels G ,

- Aveling EL ,

- Jovchelovitch S

- Widdershoven G

- Tarrant C , et al

- Malhotra D ,

- Murnighan JK

- Irlenbusch B ,

- Engeström Y

- Beauchamp TL ,

- Ledermann S

- Dixon-Woods M

- Saparito P ,

Supplementary materials

Supplementary data.

This web only file has been produced by the BMJ Publishing Group from an electronic file supplied by the author(s) and has not been edited for content.

Files in this Data Supplement:

- Data supplement 1 - Online appendix

Collaborators The Safer Clinical Systems Phase 2 Core Group Collaboration & Writing Committee, Nick Barber, Julian Bion, Matthew Cooke, Steve Cross, Hugh Flanagan, Christine Goeschel, Rose Jarvis, Peter Pronovost and Peter Spurgeon.

Contributors All authors contributed to and approved the final manuscript.

Funding Wellcome Trust, Health Foundation.

Competing interests Mary Dixon-Woods is deputy editor-in-chief of BMJ Quality and Safety .

Provenance and peer review Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Read the full text or download the PDF:

Service Evaluation

- Skip to Navigation

- Accessibility

BSL Help in a crisis

- Our Portfolio

- Patients and Public

- Partners and Infrastructure

- Get Involved - staff

A service evaluation will seek to answer “What standard does this service achieve?”. It won’t reference a predetermined standard and will not change the care a patient receives.

Where an evaluation involves patients and staff, it is best practice to seek their permission, through consent, for their participation. The degree to which consent is taken can vary from asking someone if it is OK to seek their feedback on the service, through to a formal process using consent and information leaflets.

What is a service evaluation?

Many people make claims about their services without sound evidence to inform their judgements. A well planned and executed service evaluation will provide:

- Evidence to demonstrate value for money .

- A baseline from which to measure change .

- Evidence to demonstrate effectiveness .

- Evidence to demonstrate efficiency .

- Evidence to demonstrate benefits and added value .

Service evaluations do not require NHS Research Ethics review but do need to be registered with, and approved by, the Research and Evidence Department before they can commence. This will include checks that the project is feasible (e.g., the service has capacity, appropriate timeframes) and carried out in line with Trust standards. Registration ensures the R&E Department know what type of activity (research and service evaluations) is happening in which services.

Please note, the Trust primarily processes data to deliver healthcare. The data cannot be used for other purposes unless the law allows ‘secondary processing’. Research and service evaluation are both considered secondary processing.

Data collected through service evaluations must be obtained, recorded and stored as defined by all relevant data standards, including The General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) and the Data Protection Act 2018. At all times your evaluation must be designed in such a way that privacy is built into all aspects that involve data.

A great source of information is also available from the Evaluation Works .

What do I need to do to undertake a service evaluation?

Be clear about what you want to evaluate.

This will shape how you conduct the evaluation and define what information you will need to collect and where the data is. Your project should also link to at least one of the Trust’s Quality Priorities.

Identify all stakeholders

Stakeholders in the success of your evaluation may include, amongst others service managers, commissioners, staff and patients. Be sure to engage them as early as possible to ensure they understand your work. Involving them early will help you shape your application to ensure it is successfully delivered.

Plan your project

Planning is paramount and needs to include an honest assessment of how long it will take to produce the necessary paperwork and seek approvals. You must also consider how and where data will be recorded and stored. Wherever possible you should use non-identifiable data. Data must be anonymised* or pseudonymised and kept secure within the Trust. The Information Commissioner's Office define ‘anonymised data’ as “…data that does not itself identify any individual and that is unlikely to allow any individual to be identified through its combination with other data.” Where agreed by the Research & Evidence Department, only fully anonymised data may be taken outside the Trust (e.g. to be stored on university servers).

All project members – Trust employees and those on honorary contracts – are required to have completed the Trust’s annual Information Governance (IG) training. A paper version can be provided where members do not have electronic access. Project members receiving anonymised data only are not required to complete the Trust’s IG training.

Develop your paperwork

The Service Evaluation (SE1) form sets out the information you need to provide. This covers the aims, objectives (what you will do to meet the aims), methodology (including data handling), analysis, and dissemination. Please follow the additional guidance on the SE1 form so that the form is completed in full.

Depending on how you plan to gather the data for your evaluation, you may need a participant information sheet and a consent form. You should seek appropriate informed consent from participants if you are asking them to do more than what is in the Friends & Family Test. Consent should be explicit verbal or written (written consent where participants are identifiable or where their identifiable data is involved, or qualitative methods are being used). The Research and Evidence (R&E) department can help you determine what you will need; templates are available.

All forms must be version controlled to ensure approved ones are being used.

Your project must be approved by, and registered with, the R&E department.

Prior to submission, applicants are encouraged to discuss their proposed project at one of the Trust’s monthly Research Clinics via MS Teams. This can help to improve the application. Please contact [email protected] to book on to a Research Clinic.

Apply to register your project with the Research and Evidence department

The completed SE1 form and any additional documents (e.g., copies of data collection forms and any interview topic guides) should be sent to [email protected] . Incomplete forms will be returned to the applicant to request completion. The review will not start until we have received a completed SE1 form and all relevant accompanying documents listed on the SE1 form. Please contact the R&E Department if you need advice.

Following an initial review from the R&E Compliance team, it is likely you will be invited to discuss your application at a Service Evaluation Review Panel (SERP) . This is a supportive discussion to help approve the project. The SERP will comprise representatives from relevant departments (e.g., R&E, Information Assurance) and allow applications to be processed more efficiently as it gives the applicant the opportunity to address any queries or concerns.

Applicants are expected to address any outstanding actions resulting from the SERP and submit responses. The application will be approved when any actions have been completed.

For non-Trust staff, a research passport / Letter of Access may be required where the applicant does not hold a contract with the Trust. This will be addressed at the SERP.

Applicants must not start their service evaluation until they receive written approval from the R&E Department.

Conducting your project

With good planning and engaged stakeholders your project should run according to plan. Where we see problems arise it is usually because of something that was not considered, or planning was not thorough enough.

Where relevant, the service evaluation lead will be asked to provide ‘recruitment’ figures quarterly to the R&E Department. This is so we can monitor the level of evaluation activity in the Trust. The study team should notify the R&E Dept when they have stopped recruiting participants.

Where amendments to the evaluation are necessary (e.g., timeframes, changes to the study team), the applicant should discuss and agree these with the R&E Compliance Team beforehand. This should prevent deviations to the approved study.

Writing up your project

It is important that your project is written up at the end to ensure what was learnt can be shared and used to make improvements. A Final Report (FR1) template is available. This is the minimum feedback that should be provided. You should send the final evaluation report to [email protected] so that we can put a copy on our Connect page.

In addition to providing the final report, the study team should present to the service or other relevant Trust meetings if requested.

We also want to capture the impact of your service evaluation so please give some thought as to how this can be achieved.

Forms, templates and guidance documents for service evaluations

- SE1 Form - Application for approval to conduct a Service Evaluation template v5.1.docx [docx] 53KB – for applying to seek approval for a service evaluation

- GD-E002 Service Evaluations guidance for applicants v1.1 Jan22.pdf [pdf] 251KB – for additional guidance on applying to do a service evaluation

- FR1 Form - Service Evaluation Final Report template (v2.0).docx [docx] 34KB – a template for a Final Report

- T_SE Participant Information Sheet v1.0 Feb22.docx [docx] 328KB – a template with suggested text for a Participant Information Sheet

- T_SE Consent Form v1.0 Feb22.docx [docx] 333KB – a template with suggested text for a Consent Form

Privacy policy Cookie policy Terms and conditions Accessibility statement Modern slavery statement Disclaimer Site map

Powered by VerseOne Technologies Ltd

© Nottinghamshire Healthcare NHS Foundation Trust 2024

We use cookies to personalise your user experience and to study how our website is being used. You consent to our cookies if you continue to use this website. You can at any time read our cookie policy .

- Search Menu

- Sign in through your institution

- Advance articles

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access

- Why Publish?

- About Science and Public Policy

- Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Dispatch Dates

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

1. introduction, 2. background, 4. findings, 5. discussion, 6. conclusion and final remarks, supplementary material, data availability, conflict of interest statement., acknowledgements.

- < Previous

Evaluation of research proposals by peer review panels: broader panels for broader assessments?

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Rebecca Abma-Schouten, Joey Gijbels, Wendy Reijmerink, Ingeborg Meijer, Evaluation of research proposals by peer review panels: broader panels for broader assessments?, Science and Public Policy , Volume 50, Issue 4, August 2023, Pages 619–632, https://doi.org/10.1093/scipol/scad009

- Permissions Icon Permissions

Panel peer review is widely used to decide which research proposals receive funding. Through this exploratory observational study at two large biomedical and health research funders in the Netherlands, we gain insight into how scientific quality and societal relevance are discussed in panel meetings. We explore, in ten review panel meetings of biomedical and health funding programmes, how panel composition and formal assessment criteria affect the arguments used. We observe that more scientific arguments are used than arguments related to societal relevance and expected impact. Also, more diverse panels result in a wider range of arguments, largely for the benefit of arguments related to societal relevance and impact. We discuss how funders can contribute to the quality of peer review by creating a shared conceptual framework that better defines research quality and societal relevance. We also contribute to a further understanding of the role of diverse peer review panels.

Scientific biomedical and health research is often supported by project or programme grants from public funding agencies such as governmental research funders and charities. Research funders primarily rely on peer review, often a combination of independent written review and discussion in a peer review panel, to inform their funding decisions. Peer review panels have the difficult task of integrating and balancing the various assessment criteria to select and rank the eligible proposals. With the increasing emphasis on societal benefit and being responsive to societal needs, the assessment of research proposals ought to include broader assessment criteria, including both scientific quality and societal relevance, and a broader perspective on relevant peers. This results in new practices of including non-scientific peers in review panels ( Del Carmen Calatrava Moreno et al. 2019 ; Den Oudendammer et al. 2019 ; Van den Brink et al. 2016 ). Relevant peers, in the context of biomedical and health research, include, for example, health-care professionals, (healthcare) policymakers, and patients as the (end-)users of research.

Currently, in scientific and grey literature, much attention is paid to what legitimate criteria are and to deficiencies in the peer review process, for example, focusing on the role of chance and the difficulty of assessing interdisciplinary or ‘blue sky’ research ( Langfeldt 2006 ; Roumbanis 2021a ). Our research primarily builds upon the work of Lamont (2009) , Huutoniemi (2012) , and Kolarz et al. (2016) . Their work articulates how the discourse in peer review panels can be understood by giving insight into disciplinary assessment cultures and social dynamics, as well as how panel members define and value concepts such as scientific excellence, interdisciplinarity, and societal impact. At the same time, there is little empirical work on what actually is discussed in peer review meetings and to what extent this is related to the specific objectives of the research funding programme. Such observational work is especially lacking in the biomedical and health domain.

The aim of our exploratory study is to learn what arguments panel members use in a review meeting when assessing research proposals in biomedical and health research programmes. We explore how arguments used in peer review panels are affected by (1) the formal assessment criteria and (2) the inclusion of non-scientific peers in review panels, also called (end-)users of research, societal stakeholders, or societal actors. We add to the existing literature by focusing on the actual arguments used in peer review assessment in practice.

To this end, we observed ten panel meetings in a variety of eight biomedical and health research programmes at two large research funders in the Netherlands: the governmental research funder The Netherlands Organisation for Health Research and Development (ZonMw) and the charitable research funder the Dutch Heart Foundation (DHF). Our first research question focuses on what arguments panel members use when assessing research proposals in a review meeting. The second examines to what extent these arguments correspond with the formal −as described in the programme brochure and assessment form− criteria on scientific quality and societal impact creation. The third question focuses on how arguments used differ between panel members with different perspectives.

2.1 Relation between science and society

To understand the dual focus of scientific quality and societal relevance in research funding, a theoretical understanding and a practical operationalisation of the relation between science and society are needed. The conceptualisation of this relationship affects both who are perceived as relevant peers in the review process and the criteria by which research proposals are assessed.

The relationship between science and society is not constant over time nor static, yet a relation that is much debated. Scientific knowledge can have a huge impact on societies, either intended or unintended. Vice versa, the social environment and structure in which science takes place influence the rate of development, the topics of interest, and the content of science. However, the second part of this inter-relatedness between science and society generally receives less attention ( Merton 1968 ; Weingart 1999 ).

From a historical perspective, scientific and technological progress contributed to the view that science was valuable on its own account and that science and the scientist stood independent of society. While this protected science from unwarranted political influence, societal disengagement with science resulted in less authority by science and debate about its contribution to society. This interdependence and mutual influence contributed to a modern view of science in which knowledge development is valued both on its own merit and for its impact on, and interaction with, society. As such, societal factors and problems are important drivers for scientific research. This warrants that the relation and boundaries between science, society, and politics need to be organised and constantly reinforced and reiterated ( Merton 1968 ; Shapin 2008 ; Weingart 1999 ).

Glerup and Horst (2014) conceptualise the value of science to society and the role of society in science in four rationalities that reflect different justifications for their relation and thus also for who is responsible for (assessing) the societal value of science. The rationalities are arranged along two axes: one is related to the internal or external regulation of science and the other is related to either the process or the outcome of science as the object of steering. The first two rationalities of Reflexivity and Demarcation focus on internal regulation in the scientific community. Reflexivity focuses on the outcome. Central is that science, and thus, scientists should learn from societal problems and provide solutions. Demarcation focuses on the process: science should continuously question its own motives and methods. The latter two rationalities of Contribution and Integration focus on external regulation. The core of the outcome-oriented Contribution rationality is that scientists do not necessarily see themselves as ‘working for the public good’. Science should thus be regulated by society to ensure that outcomes are useful. The central idea of the process-oriented Integration rationality is that societal actors should be involved in science in order to influence the direction of research.

Research funders can be seen as external or societal regulators of science. They can focus on organising the process of science, Integration, or on scientific outcomes that function as solutions for societal challenges, Contribution. In the Contribution perspective, a funder could enhance outside (societal) involvement in science to ensure that scientists take responsibility to deliver results that are needed and used by society. From Integration follows that actors from science and society need to work together in order to produce the best results. In this perspective, there is a lack of integration between science and society and more collaboration and dialogue are needed to develop a new kind of integrative responsibility ( Glerup and Horst 2014 ). This argues for the inclusion of other types of evaluators in research assessment. In reality, these rationalities are not mutually exclusive and also not strictly separated. As a consequence, multiple rationalities can be recognised in the reasoning of scientists and in the policies of research funders today.

2.2 Criteria for research quality and societal relevance