An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- My Bibliography

- Collections

- Citation manager

Save citation to file

Email citation, add to collections.

- Create a new collection

- Add to an existing collection

Add to My Bibliography

Your saved search, create a file for external citation management software, your rss feed.

- Search in PubMed

- Search in NLM Catalog

- Add to Search

Dynamics of Identity Development in Adolescence: A Decade in Review

Affiliations.

- 1 Utrecht University.

- 2 Erasmus University Rotterdam.

- PMID: 34820948

- PMCID: PMC9298910

- DOI: 10.1111/jora.12678

One of the key developmental tasks in adolescence is to develop a coherent identity. The current review addresses progress in the field of identity research between the years 2010 and 2020. Synthesizing research on the development of identity, we show that identity development during adolescence and early adulthood is characterized by both systematic maturation and substantial stability. This review discusses the role of life events and transitions for identity and the role of micro-processes and narrative processes as a potential mechanisms of personal identity development change. It provides an overview of the linkages between identity development and developmental outcomes, specifically paying attention to within-person processes. It additionally discusses how identity development takes place in the context of close relationships.

Keywords: adjustment problems; adolescence; identity; within-person processes.

© 2021 The Authors. Journal of Research on Adolescence published by Wiley Periodicals LLC on behalf of Society for Research on Adolescence.

PubMed Disclaimer

Similar articles

- Adolescent identity development in context. Branje S. Branje S. Curr Opin Psychol. 2022 Jun;45:101286. doi: 10.1016/j.copsyc.2021.11.006. Epub 2021 Dec 7. Curr Opin Psychol. 2022. PMID: 35008027 Review.

- The development of narrative identity in late adolescence and emergent adulthood: the continued importance of listeners. Pasupathi M, Hoyt T. Pasupathi M, et al. Dev Psychol. 2009 Mar;45(2):558-74. doi: 10.1037/a0014431. Dev Psychol. 2009. PMID: 19271839

- Daily Identity Dynamics in Adolescence Shaping Identity in Emerging Adulthood: An 11-Year Longitudinal Study on Continuity in Development. Becht AI, Nelemans SA, Branje SJT, Vollebergh WAM, Meeus WHJ. Becht AI, et al. J Youth Adolesc. 2021 Aug;50(8):1616-1633. doi: 10.1007/s10964-020-01370-3. Epub 2021 Jan 9. J Youth Adolesc. 2021. PMID: 33420886 Free PMC article.

- Narrative identity in the psychosis spectrum: A systematic review and developmental model. Cowan HR, Mittal VA, McAdams DP. Cowan HR, et al. Clin Psychol Rev. 2021 Aug;88:102067. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2021.102067. Epub 2021 Jul 10. Clin Psychol Rev. 2021. PMID: 34274799 Free PMC article. Review.

- It's how I am . . . it's what I am . . . it's a part of who I am: A narrative exploration of the impact of adolescent-onset chronic illness on identity formation in young people. Wicks S, Berger Z, Camic PM. Wicks S, et al. Clin Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2019 Jan;24(1):40-52. doi: 10.1177/1359104518818868. Clin Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2019. PMID: 30789046

- Academic motivation in adolescents: the role of parental autonomy support, psychological needs satisfaction and self-control. Çelik O. Çelik O. Front Psychol. 2024 May 10;15:1384695. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2024.1384695. eCollection 2024. Front Psychol. 2024. PMID: 38800688 Free PMC article.

- Trajectories of Gender Identity and Depressive Symptoms in Youths. Real AG, Lobato MIR, Russell ST. Real AG, et al. JAMA Netw Open. 2024 May 1;7(5):e2411322. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.11322. JAMA Netw Open. 2024. PMID: 38776085 Free PMC article.

- Voices of Identity: Exploring Identity Development and Transformation among Urban American Indian/Alaska Native Emerging Adults. Malika N, Palimaru AI, Rodriguez A, Brown R, Dickerson DL, Holmes P, Kennedy DP, Johnson CL, Sanchez VA, Schweigman K, Klein DJ, D'Amico EJ. Malika N, et al. Identity (Mahwah, N J). 2024;24(2):112-138. doi: 10.1080/15283488.2023.2300075. Epub 2024 Jan 8. Identity (Mahwah, N J). 2024. PMID: 38699070 Free PMC article.

- Identifying the top predictors of student well-being across cultures using machine learning and conventional statistics. King RB, Wang Y, Fu L, Leung SO. King RB, et al. Sci Rep. 2024 Apr 10;14(1):8376. doi: 10.1038/s41598-024-55461-3. Sci Rep. 2024. PMID: 38600124 Free PMC article.

- Psychological flexibility and cognitive-affective processes in young adults' daily lives. Westhoff M, Heshmati S, Siepe B, Vogelbacher C, Ciarrochi J, Hayes SC, Hofmann SG. Westhoff M, et al. Sci Rep. 2024 Apr 8;14(1):8182. doi: 10.1038/s41598-024-58598-3. Sci Rep. 2024. PMID: 38589553 Free PMC article.

- Adler, J. M. (2012). Living into the story: Agency and coherence in a longitudinal study of narrative identity development and mental health over the course of psychotherapy. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 102, 367–389. 10.1037/a0025289 - DOI - PubMed

- Adler, J. M. , Chin, E. D. , Kolisetty, A. P. , & Oltmanns, T. F. (2012). The distinguishing characteristics of narrative identity in adults with features of borderline personality disorder: An empirical investigation. Journal of Personality Disorders, 26, 498–512. 10.1521/pedi.2012.26.4.498 - DOI - PMC - PubMed

- Adler, J. M. , Lodi‐Smith, J. , Philippe, F. L. , & Houle, I. (2016). The incremental validity of narrative identity in predicting well‐being: A review of the field and recommendations for the future. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 20, 142–175. 10.1177/1088868315585068 - DOI - PubMed

- Albarello, F. , Crocetti, E. , & Rubini, M. (2018). I and us: A longitudinal study on the interplay of personal and social identity in adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 47, 689–702. 10.1007/s10964-017-0791-4 - DOI - PubMed

- Anthis, K. S. (2002). On the calamity theory of growth: The relationship between stressful life events and changes in identity over time. Identity, 2, 229–240. 10.1207/S1532706XID0203_03 - DOI

Publication types

- Search in MeSH

LinkOut - more resources

Full text sources.

- Europe PubMed Central

- Ovid Technologies, Inc.

- PubMed Central

- MedlinePlus Health Information

- Citation Manager

NCBI Literature Resources

MeSH PMC Bookshelf Disclaimer

The PubMed wordmark and PubMed logo are registered trademarks of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). Unauthorized use of these marks is strictly prohibited.

A deep dive into adolescent development

Spearheaded by psychologists, a new long-term study will produce mountains of open-access data on adolescents

By Kirsten Weir

June 2019, Vol 50, No. 6

Print version: page 20

- Open Science

In January, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) released the first complete baseline data set from the largest-ever study of adolescent health and development. The Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development (ABCD) Study will follow 11,874 children, starting at ages 9 and 10, for the next decade.

The ABCD Study will collect mountains of data: on neurological development, sociocultural and psychological factors, mental and physical health, environmental exposures, substance use, academic achievement and more. It's a huge undertaking, with huge implications for understanding children's development as they move through adolescence and into early adulthood.

"This is a massive effort, notable for both its scope and its depth," says Sandra Brown, PhD, vice chancellor for research and professor of psychology and psychiatry at the University of California, San Diego, and co-director of the ABCD Coordinating Center.

Because the project looks at so many different aspects of development, researchers will be able to mine the data to understand problems such as substance use and the emergence of mental illness, as well as the normal course of healthy adolescent development, adds Sara Jo Nixon, PhD, a professor of psychology at the University of Florida and a principal investigator of the study. "Often, we're interested in what went wrong, and indeed we'll have data to speak to those problems. But we'll also have data to look at resiliency and the kinds of factors—whether biological, psychological, social or cultural—that really nurture healthy development," she says. "This study is the epitome of what any psychological scientist would love to do."

ABCD basics

Launched in 2016, the ABCD Study is coordinated by the National Institute on Drug Abuse and the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, with support from numerous other NIH institutes and offices as well as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. To assist in recruitment, APA provided NIH with a statement encouraging families to consider participating, and an APA staff member serves on the ABCD national liaison board.

The study encompasses 21 research sites across the country and will follow participants for 10 years. It's an interdisciplinary effort, but psychologists Brown and Terry Jernigan, PhD, also at the University of California, San Diego, sit at the helm of the Coordinating Center, and 26 of the 40 principal investigators are psychologists. The study was carefully planned from the start to include a diverse group of adolescents, Brown says.

"We worked with high-quality epidemiologists, so the sample we're bringing to the table is a good reflection of the sociodemographics of the United States," she says.

To manage such a large project, the study's designers included funding for a coordinating center and a data management center. There's also a retention committee that works to ensure that as many of the participants as possible stick it out over the next decade—no small feat, considering the time investment. The project involves neuroimaging, genetic testing and behavioral testing as well as numerous questionnaires for the children, their parents and teachers. Participants will wear sensors 'round-the-clock for several weeks, most likely once a year, to collect data about activity levels, heart rate and sleep patterns. Investigators will even collect hair samples and baby teeth to study exposures to environmental toxins. The study includes more than 2,000 twins and triplets, allowing researchers to begin to tease apart genetic susceptibility from environmental influences.

As the children move into their teenage years, researchers will be able to explore questions about substance use, physical activity, sports injuries, sleep, learning and the emergence of mental health problems—and that's just for starters, says psychologist Susan Tapert, PhD, a professor at the University of California, San Diego, and an associate director of the ABCD Coordinating Center. "There's really an infinite number of questions that can be addressed here."

Principal investigators aren't the only scientists who will be able to answer them. The study was developed with an open-access model, and the data collected are freely available to any qualified researcher who wants to tap into them via the National Institute of Mental Health Data Archive .

The open-science philosophy will drive the science forward faster, while the large sample size and methodologically rigorous study design will ensure that the data are trustworthy, says Raul Gonzalez, PhD, an ABCD principal investigator and professor of psychology at Florida International University. "There is a replication crisis in the sciences, and a lot of that crisis is partially due to small sample sizes and a bias to publish significant results," he says. "With this study, there is an opportunity to assess a lot of questions that are controversial in our field."

Another unique element of the open-access model: Lead investigators won't have preferential access to data before they've been made available to the general public. Whether you're a principal investigator at one of the study sites or a grad student far from the action, you will have the same opportunity to access the same information at the same time through planned data releases. "That says a lot about the commitment of the leadership team to make sure transparency and reproducibility are addressed head-on," says Nixon.

Early findings

Investigators finished recruiting participants only last year, yet they have already begun drawing insights from the study. In one analysis of the baseline data, Aaron Blashill, PhD, and Jerel Calzo, PhD, of San Diego State University, explored differences in mood disorders and suicidality between 9- and 10-year-olds who identified as gay, lesbian or bisexual and those who identified as heterosexual. The rate of mood disorders was 22.5 percent for sexual minority children, compared with 6.9 percent for heterosexual children. Similarly, 19.1 percent of sexual minority children experienced suicidal thoughts, while just 4.6 percent of heterosexual children did ( Journal of Affective Disorders , Vol. 246, No. 1, 2019).

Other groups have pulled from ABCD data to explore a pressing 21st-century problem: the effects of screen time. Jeremy Walsh, PhD, now at the University of British Columbia Okanagan, and colleagues explored physical activity, screen-time behavior and sleep among more than 4,500 of the participants. They found that children who met recommended guidelines for these activities—at least 60 minutes of physical activity, no more than two hours of recreational screen time and 9 to 11 hours of sleep daily—had better cognition than those who did not, as measured by tests of attention, language abilities, episodic memory, working memory, executive function and processing speed. Unfortunately, though, only half of the children in the sample got the recommended amount of sleep, just 36 percent had fewer than two hours of screen time and a mere 17 percent engaged in the recommended amount of daily exercise, the researchers found ( The Lancet Child & Adolescent Health , Vol. 2, No. 11, 2018).

Meanwhile, Tapert and colleagues found a link between screen time and a variety of complex structural brain changes, including cortical thickness, sulcal depth and gray matter volume. Different patterns of structural changes were related to downstream outcomes such as externalizing psychopathology and fluid and crystallized intelligence. But the changes differed depending on the type of screen media—and they weren't all bad (or all good) ( Neuroimage , Vol. 185, No. 1, 2019). "Kids who frequently played video games tended to have poorer mental health profiles and more family conflict, for example, while kids who were engaged in social media tended to have slightly better social and mental health functioning," she says. "It's not just how much screen time a child gets, but what they're doing."

With a single time point of data, it's too soon to make conclusions about the pros and cons of different screen media activities, Tapert notes. But as researchers follow the children in the years to come, they hope to be able to paint a more detailed picture of the effects of screen time on the brain.

A study that evolves

A lot can change in a decade. New social media platforms pop up almost overnight. Drug laws change, and the popularity of certain substances of abuse can wax and wane. New genetic tests and biomarkers may be discovered, new sensor technology could become available and neuroimaging techniques will be refined. The ABCD investigators have designed the study to accommodate such changes, so that new survey questions can be added and new technologies can be incorporated in future waves of data collection. "We have structures within ABCD that allow us to maintain enough continuity, so we can look at change in a systematic way and also augment the study using new methodologies," Brown says.

With its breadth, depth and flexible experimental design, the ABCD Study will serve as a model for other large-scale, long-term projects, investigators say. It also serves to showcase just how much psychology can do. "This is truly team science, led in large part by psychologists," Nixon says. "It speaks to the strength of our science, and the opportunity for psychologists to play a leading role in interdisciplinary research."

The Structure of Cognition in 9 and 10 Year-Old Children and Associations With Problem Behaviors:Findings From the ABCD Study's Baseline Neurocognitive Battery Thompson, W.K., et al. Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience , 2018

A Description of the ABCD Organizational Structure and Communication Framework Auchter, A.M., et al. Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience , 2018

Adolescent Neurocognitive Development and Impacts of Substance Use:Overview of the Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development (ABCD) Baseline Neurocognition Battery Luciana, M., et al. Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience , 2018

Letters to the Editor

- Send us a letter

MINI REVIEW article

Understanding the dynamics of the developing adolescent brain through team science.

- 1 Department of Developmental and Educational Psychology, Institute of Psychology, Leiden University, Leiden, Netherlands

- 2 Leiden Institute for Brain and Cognition (LIBC), Leiden University, Leiden, Netherlands

- 3 Erasmus School of Social and Behavioral Sciences, Erasmus University Rotterdam, Rotterdam, Netherlands

One of the major goals for research on adolescent development is to identify the optimal conditions for adolescents to grow up in a complex social world and to understand individual differences in these trajectories. Based on influential theoretical and empirical work in this field, achieving this goal requires a detailed understanding of the social context in which neural and behavioral development takes place, along with longitudinal measurements at multiple levels (e.g., genetic, hormonal, neural, behavioral). In this perspectives article, we highlight the promising role of team science in achieving this goal. To illustrate our point, we describe meso (peer relations) and micro (social learning) approaches to understand social development in adolescence as crucial aspects of adolescent mental health. Finally, we provide an overview of how our team has extended our collaborations beyond scientific partners to multiple societal partners for the purpose of informing and including policymakers, education and health professionals, as well as adolescents themselves when conducting and communicating research.

Introduction

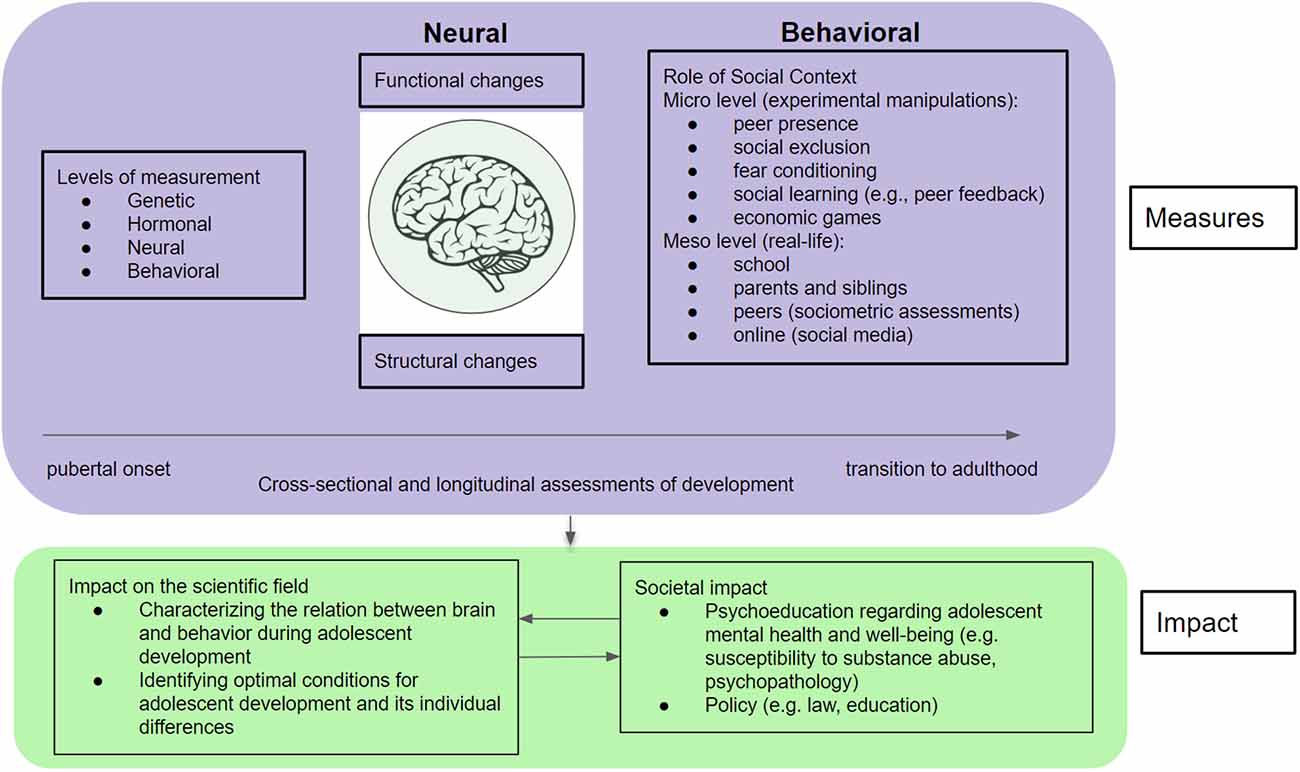

Adolescence is a developmental phase between the ages of 10 and 24 years ( Sawyer et al., 2018 ). Adolescence starts with puberty, setting off a cascade of hormonal changes signaling the start of biological maturation ( Dahl et al., 2018 ), and is characterized by major physical, psychological, and social changes ( Blakemore and Mills, 2014 ). Adolescents navigate an increasingly complex social network in which peer relations become more salient and are an important source for social learning (e.g., learning about, with, and from peers to adjust to changing social environments; Westhoff et al., 2020a ). Both peer relations and social learning have a great impact on mental well-being ( Nelson et al., 2005 , 2016 ; Vitaro et al., 2009 ). Moreover, adolescence is considered a period of heightened sensitivity to mental health problems, with approximately 75% of adult mental health problems first appearing during adolescence ( Kessler et al., 2007 ; Solmi et al., 2021 ). As biological, psychological, and social changes occur concurrently in adolescence, it is crucial to understand how these changes are intertwined and contribute to successful developmental outcomes, such as resilience and mental health, as well as to maladaptive outcomes, such as risky behaviors and psychopathology ( Davey et al., 2008 ; Crone and Dahl, 2012 ; Güroğlu, 2021 ). We further argue that understanding adolescence as a developmental phase with risks and opportunities requires incorporating a transactional perspective with measurements at multiple levels (genetic, hormonal, neural, behavioral) and across different social settings (e.g., school, parent relationships, peer relationships; see Figure 1 ). Considering the multitude of factors influencing development and the interlinked complexity of their corresponding measurement levels, we propose that team science is a fruitful approach to understanding the dynamics of adolescent development.

Figure 1 . Overview of the measures required to chart the complexity of developmental changes during adolescence and their impact. Note: This figure illustrates the richness of measures needed in studies that aim to capture the complexity of developmental changes during adolescence (purple). Findings from such studies will subsequently have a scientific and societal impact (green). Impact on the scientific field and on society are interlinked, as collaborating and communicating with societal stakeholders (e.g., policymakers, teachers, parents, and adolescents) also informs new research questions.

To understand individual differences in optimal conditions for growing up in an increasingly complex social world, we use a variety of neurobiological and behavioral methods. Current influential models of adolescent brain development describe an asynchronous development of the limbic “socio-affective system” and cortical “cognitive control system” during adolescence ( Steinberg, 2008 ; Somerville et al., 2010 ). These models emphasize that faster maturation of the limbic system compared to the slower maturation of the cortical system underlies heightened reward sensitivity and risk-taking tendencies, leading to risky and impulsive behaviors such as alcohol use ( Peters et al., 2017 ). Recent accounts of adolescent development also include the impact of individual differences in hormonal, genetic, behavioral, and neural influences which are intertwined in a social context ( Crone and Dahl, 2012 ; Pfeifer and Allen, 2021 ). Specifically, adolescence is seen as a time for heightened goal flexibility, where social goals can influence pathways for development. Hence, the asynchronous development between the limbic and cortical system, together with increasingly complex and influential social experiences, such as peer relations and social learning, makes adolescence a sensitive window for socio-affective development which can lead to multiple pathways, such as risky behaviors and mental illness, or prosocial behavior and mental resilience ( Crone and Dahl, 2012 ; Güroğlu, 2021 ; see Figure 1 ).

In this article, we highlight the unique position of our highly collaborative multidisciplinary research program and focus on its contributions to the field. We provide an overview of our research focusing on: (1) meso level peer relations; and (2) micro level social learning and next describe their combined influence on mental health. We propose that these two themes are crucial in charting the complexity of the dynamically interlinked biological, psychological, and social changes in adolescence. We provide examples of our research designs with controlled experimental settings at the micro-level and assessments of real-life social relationships at the meso level (see Figure 1 ). Finally, we demonstrate how collaborations can be extended to multiple societal partners to inform and include policy makers, education and health professionals, and adolescents themselves when conducting and communicating research. We conclude that understanding the complex dynamics of adolescent development requires rich measurements and we highlight the promising role of team science in achieving this goal.

Peer Relations

Adolescence is characterized by a significant shift in focus from parents toward peers, also referred to as social reorientation ( Nelson et al., 2005 ). Compared to children, adolescents spend increasingly more time without adult supervision and in the company of their peers, where fitting in the peer group and peers’ opinions become vital for adolescents’ self-identity development ( Laursen and Veenstra, 2021 ). Social goals, such as acceptance by the peer group and forming and maintaining friendships, are particularly important in the school context, as they are consistently linked with markers of positive social adjustment and academic achievement ( Dawes, 2017 ). Recently, evidence from neuroimaging studies corroborate the significance of the peer context for adolescents by finding that adolescents show heightened neural responses during social decision-making in brain regions related to reward and motivation, such as the ventral striatum, and in social cognition, such as dorsomedial prefrontal cortex (for reviews see Van Hoorn et al., 2019 ; Andrews et al., 2021 ). For example, in early- and mid-adolescence, mere peer presence, when being observed by an unfamiliar peer, results in heightened neural activation in the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC; Somerville et al., 2013 ), and when being observed by a friend, adolescents show increased risk-taking behavior, with heightened activation of the ventral striatum ( Chein et al., 2011 ). In an Event-Related Potential (ERP) study, we have shown that manipulation of participants’ social rank (high vs. low rank) modulated neural responses during social exchanges in mid-adolescents but not in children or adults, signifying that even transient social interactions are particularly salient for mid-adolescents ( Zanolie and Crone, 2021 ). In another study, compared to being alone, the presence of a group of spectators (consisting of adolescent confederate actors) led to increased prosocial behavior which was accompanied by enhanced activation in social brain areas such as mPFC, temporal parietal junction (TPJ), precuneus and superior temporal sulcus (STS; Van Hoorn et al., 2016 ). Taken together, these studies of peer presence illustrate the importance of capturing the peer context when studying adolescents’ social behavior ( Figure 1 , micro level).

Neuroimaging studies aiming to capture real-life peer context ( Figure 1 , meso level), however, face the challenge of bringing peer relationships into the highly controlled experimental laboratory setting, such as in the MRI scanner (see Güroğlu and Veenstra, 2021 for a more extensive review of this research line). In tackling this challenge, sociometric assessments of the peer network provide a useful tool to classify an individual’s peer status within a real-life peer group (see Box 1 ). Combinations of sociometric assessments with neuroimaging and/or economic exchange paradigms assessing social decision-making (see Box 2 ) led to insights into how social interactions and their neural underpinnings may depend on peer context ( Güroğlu et al., 2014 ). For example, we found in adults that interactions with familiar peers relate to heightened activation of brain regions of affect and reward (including the ventral striatum and amygdala) and social cognition (including the mPFC, TPJ, STS, and precuneus; Güroğlu et al., 2008 ). Recently, we showed that the developmental trajectories of ventral striatum responses to rewards are modulated by friendship stability across a 5-year period ( Schreuders et al., 2018 ) and that ventral striatum responses to winning money are also (negatively) related to acceptance by the peer group ( Meuwese et al., 2018 ). We also showed that in young adults ( Schreuders et al., 2018 ) and mid-adolescents ( Schreuders et al., 2019 ), prosocial decisions toward friends compared to disliked or unfamiliar peers, are related to increased activation of the putamen, part of the reward circuitry, and the posterior temporoparietal regions that are involved in social-cognitive processes. Moreover, neural responses to social rejection depend on the excluder’s peer status relative to the adolescent’s own status ( De Water et al., 2017 ). Our longitudinal studies further showed that the history of peer experiences across childhood modulates neural responses to social exclusion and during social decision-making in adolescence ( Will and Güroğlu, 2016 ; Will et al., 2016 , 2018 ; Asscheman et al., 2019 ).

Box 1. Using sociometric assessments to study social experiences.

Sociometric assessments based on nominations of classmates on various criteria (e.g., “who do you like?”, “who do you dislike?”, “who are your friends?”) are most valuable for assessing social experiences, and more specifically for assessing peer relationships, in an efficient manner. Crucially, these social assessments require access to a closed network (e.g., classmates, sports team, an orchestra) where the nominations can be made. These nominations can be used to assess social experiences at two levels. At the dyadic level, they reveal reciprocal relationships, such as mutual friendships between two people who nominate each other as a friend (see, e.g., Güroğlu et al., 2008 ; Schreuders et al., 2019 ). At the group level, they reveal information on the status of the individual within the peer group, such as accepted or rejected status based on the total number of received nominations from like and dislike nominations ( Will et al., 2016 ; Will and Güroğlu, 2016 ). Finally, by applying graph theory, these nominations can be used to calculate social network characteristics that can be used to characterize individuals’ positions in the network, such as centrality, as well as identifying group level characteristics, such as social cohesion ( Van den Bos et al., 2018 ). An increasing number of studies combine assessments of peer relations with neuroscientific designs to investigate how peer relations modulate brain activity (see for review Güroğlu and Veenstra, 2021 ).

Box 2. Using economic games to study social interactions.

Economic games create social contexts that reveal fundamental aspects about the participant’s social preferences in ways that are quantifiable. They have proven highly efficient in assessing various forms of (pro) social behavior both in adults and in development ( Camerer, 2011 ; Will and Güroğlu, 2016 ). These paradigms are based on an economic exchange between at least two players where the participant’s decisions have actual consequences for their own and their interaction partner’s payoff. The simplest example is the Dictator Game in which the first player is given valued goods (e.g., money, toys, candies) and can share a portion of those goods with a second player. While game theoretical models assume that humans are rational players who aim to maximize their own profit, findings consistently show that people typically share some portion of the goods, thereby revealing other-regarding preferences. In the Ultimatum game , the first player (proposer) is a variant where the second player can either accept or reject the share given by the first player. If accepted, the goods are divided as proposed by the first player. If rejected, both players receive nothing. The reward maximizing strategy is to accept any offer greater than zero, but again consistent findings show that offers viewed as unfair are rejected ( Fehr and Schmidt, 1999 ). Offers made by the first player are typically higher in the Ultimatum Game than Dictator Game, revealing strategic considerations to reduce the probability of rejection. Another variant is the Trust Game , in which the first player (investor) can again share a portion of goods with the second player (trustee). The portion received by the trustee is multiplied by the experimenters. The trustee then chooses to either share the profit with the investor (reciprocation; both profit from the exchange) or keep all the profit (betrayal; only the trustee profits, the investor loses the entrusted amount; Berg et al., 1995 ). These paradigms can be presented in a repeated fashion, such that participants play multiple rounds of these games with the same partner(s). Feedback received during these repeated interactions facilitates learning about the social preferences of other individuals or groups. Economic exchange paradigms are simple enough to administer to a wide age range (from 3 years old to adults) and enable studying developmental patterns in social behavior ( Güroğlu et al., 2009 ; Meuwese et al., 2015 ; Zanolie et al., 2015 ; Ma et al., 2017 ). Moreover, their structured nature makes them further suitable for neuroimaging research.

Taken together, increasing evidence shows both current and long-term patterns of social experiences with peers modulate adolescent social behavior and their underlying neural processes ( Güroğlu, 2022 ). In order to understand the developing brain in a social context, future studies need to incorporate measures of social networks with assessments of brain function and structure ( Lamblin et al., 2017 ; Baek et al., 2021 ). Additionally, the complexity of social dynamics has in recent years only been amplified through the addition of the online social layer where young people can have meaningful connections. Future studies aiming to understand the dynamics of adolescent development need to include assessments of both offline and online connections.

Social Learning

Peer relations interact with individual and social learning. Social learning encompasses learning about, with, and from others. In the peer context, it involves learning about the characteristics and preferences of a peer or a peer group, such as their trustworthiness or cooperativeness ( Nelson et al., 2005 ; Blakemore and Mills, 2014 ; Sawyer et al., 2018 ). Adaptive social behavior requires adolescents to learn about these characteristics and adjust their own behavior accordingly, such as learning when to be prosocial and towards whom ( Steinberg and Morris, 2001 ; Van den Bos et al., 2011 ; Lockwood et al., 2016 ; Crone and Fuligni, 2020 ). These social learning processes are crucial for fostering healthy relationships with peers, which are predictive of adolescents’ long-term well-being ( Paus et al., 2008 ; Crone and Dahl, 2012 ; Dahl et al., 2018 ; Sawyer et al., 2018 ).

Social learning is often studied with repeated behavioral economic paradigms, where participants play multiple rounds of an economic game with the same partner or multiple partners from one experimentally selected group (see Box 2 ). Peer characteristics or peer evaluations are typically experimentally manipulated, allowing participants to learn through positive and negative feedback ( Ma et al., 2020 ; Westhoff et al., 2020b ; Zanolie and Crone, 2021 ). Reinforcement learning models can then be used to characterize individual differences in learning strategies, learning speed, and the underlying cognitive processes that cause age differences in learning about others ( Sutton and Barto, 2018 ; Nussenbaum and Hartley, 2019 ; Wilson and Collins, 2019 ). For example, we used an information sampling paradigm in which participants were able to sample information about a peer’s history of trustworthiness before deciding to trust or not trust them ( Ma et al., 2020 ). We found that behavioral adaptation to the gathered evidence improved with age, especially from early to mid-adolescence. In other studies, we manipulated the cooperativeness of groups ( Westhoff et al., 2020b ) and used a probabilistic learning task in which participants could sometimes earn rewards for themselves and sometimes for others ( Westhoff et al., 2021 ). We found that probabilistic learning to benefit others showed age-related improvement across adolescence and was associated with ventromedial prefrontal cortex responses to unexpected outcomes. Learning for the self was stable across adolescence and associated with ventral striatal responses to unexpected outcomes. Together, these findings suggest that adolescents show rapid improvements in behavioral adjustments to the social environment, especially from early to mid-adolescence. These findings are consistent with the idea that learning about the consequences of actions in an interpersonal context is especially salient for adolescents and furthermore highlight early to mid-adolescence as a sensitive period for learning about others ( Blakemore and Mills, 2014 ; Nelson et al., 2016 ; Sawyer et al., 2018 ; Andrews et al., 2021 ).

Considering that learning at school takes place in the peer context (i.e., in classrooms and group assignments), learning about, with, and from peers are also crucial research lines to identify the optimal conditions of learning at school. In ongoing studies, we focus on determining which individuals work well together by combining reinforcement learning or feedback processing paradigms with sociometric assessments. Such studies form the first steps of identifying optimal conditions for learning in the context of peers by informing how peer relationships in classrooms and differences in learning strategies between collaborating students may influence (social) learning.

Social Experiences and Mental Health

It is well-established that social experiences influence mental health and well-being. For example, close friendships during adolescence are a protective factor against mental health problems across adolescence and later in life ( Van Harmelen et al., 2017 , 2021 ). However, being rejected by peers is associated with self-harm ( Esposito et al., 2019 ) and depressive symptoms ( Platt et al., 2013 ). Also, epidemiological studies have shown a peak in the emergence of mental health problems across adolescence ( Dalsgaard et al., 2020 ). Showing symptoms of psychopathology in childhood or adolescence are found to be a key predictor of mental health problems and other adverse outcomes later in life ( Zisook et al., 2007 ; Caspi et al., 2020 ). These findings indicate that there are developmental processes enhancing or bringing about vulnerabilities to develop mental health problems. Theoretical models propose a complex interplay between brain development, hormonal changes, and social development in interaction with environmental factors that may explain the emergence and maintenance of mental health problems across adolescence ( Pfeifer and Allen, 2021 ). So far, only a few studies have directly linked the relationship between social context, brain development, and mental health outcomes. One study showed that greater subgenual anterior cingulate activity (sgACC) during a social exclusion game was associated with an increase in parent-reported depressive symptoms 1 year later ( Masten et al., 2013 ). Social interactions with friends have also been related to activation of the sgACC and the ventral striatum. These brain regions are associated with the reward circuitry, speculatively providing indirect evidence linking positive peer interactions with mental health ( Güroğlu et al., 2008 ; Schreuders et al., 2021 ). Research is needed to elucidate the complex interplay between brain development, social context, and mental health ( Davey et al., 2008 ; Pfeifer and Allen, 2021 ). To better understand mental health and the transition from mental health to mental illness, our ongoing studies aim to contextualize individual differences in relation to social development and genetic factors (e.g., by using twin designs; Crone et al., 2020 ), and their association with mental health outcomes in a developmental context ( Ferschmann et al., 2021 ).

Crucial in contextualizing individual differences in etiology and maintenance of mental health problems is investigating neurobiological mechanisms of psychopathology from a longitudinal perspective. Specifically, non-linear developmental changes in cortical and subcortical structures may explain why cross-sectional developmental neuroimaging studies may find mixed results depending on the age range of the participants ( Wierenga et al., 2014a , b ; Mills et al., 2021 ). With longitudinal designs, we, for example, found that heightened scores on externalizing symptoms were associated with smaller developmental changes in brain structure ( Vijayakumar et al., 2014 ; Oostermeijer et al., 2016 ; Ambrosino et al., 2017 ; Bos et al., 2018a ; but see Ducharme et al., 2011 ). Likewise, for internalizing symptoms, such as depression, longitudinal studies revealed associations with aberrant brain development ( Whittle et al., 2014 ; Luby et al., 2016 ; Bos et al., 2018b ). Together, these studies highlight the importance of longitudinal studies for understanding mental health problems and their development.

Integrating Science and Society

Integrating scientific knowledge about adolescent development into society can be achieved in multiple ways. Popular science books such as “The Adolescent Brain” (Het Puberende Brein, Crone, 2018 ) and “Inventing ourselves” ( Blakemore, 2018 ) help to reach a wider audience, including policymakers (“science for policy”). In our team, we aim to reach adolescents via targeted websites designed for youth 1 and scientific articles for children ( Westhoff et al., 2020a ). We also inform youth professionals by designing educational material for elementary and high schools about the developing brain (e.g., http://www.breinkennisleiden.nl/onderwijs ), and through our contributions to science-translation reports such as those on differences between boys and girls in learning (report Dutch Educational Council), and UNESCO’s International Science and Evidence-based Education Assessment on the social-emotional learning ( Gotlieb et al., 2022 ).

It is particularly important to include adolescents themselves when forming policies and designing interventions in order to make their participation efforts optimal and to contribute to their sense of autonomy which benefits their mental health ( Fuligni, 2019 ). Especially during mid-adolescence interventions typically tend to fail when they do not align with adolescents’ desired feeling to be respected and accorded status ( Yeager et al., 2018 ). Peer-led interventions to generate positive behavioral changes can be powerful when the complexity of peer relations and social networks are taken into account as well as social learning (e.g., imitation, norms, and positive reinforcement; Veenstra and Laninga-Wijnen, 2022 ). The next step toward improving these efforts is setting up projects in which adolescents are involved in co-designing and co-creating research ( Whitmore and Mills, 2021 ). Not only does this enrich the context in which scientific findings can be launched and interpreted, but crucially informs researchers in important ways, helping them to improve their research designs and paradigms. In our current projects, adolescent volunteers are also involved in disseminating knowledge to their peers, thereby increasing the likelihood that the information is relevant and interesting for the target audience (e.g., http://www.instagram.com/breinboost ). Finally, in several innovative projects we involve societal stakeholders (e.g., teachers, adolescents, policymakers) in the research consortium from the start of the project and create research and knowledge dissemination projects together throughout the project (see e.g., http://www.neurolab.nl/startimpuls , Vandenbroucke et al., 2021 ).

Conclusions

In this perspectives article, we provided an overview of ways of characterizing developmental changes during adolescence and their relation to the developing brain. We highlighted the importance of capturing social contextual factors, as social experiences play a crucial role in shaping many developmental trajectories. We further emphasized the importance of longitudinal approaches in developmental studies in identifying predictors of mental health. The social context is increasingly important given that young people today grow up in a highly socially complex environment. The recent COVID-19 pandemic showed how strong the effects of the changing social context are on adolescents’ mental health has been ( Orben et al., 2020 ; Van de Groep et al., 2020 ; Asscheman et al., 2021 ; Breaux et al., 2021 ; Green et al., 2021 ; Klootwijk et al., 2021 ). An increased understanding of the effect of social contextual factors on the development and neurobiological mechanisms underlying mental health will inform high stake policy questions, and find their way to daily practice. Throughout this overview, we illustrated the value of collaborative team science to understand adolescent development and the value of integration of science and society to be able to inform policy and practice.

Author Contributions

All authors co-designed the aims and wrote the article. KZ and IM designed the article aims, outline, figure, and integrated individual author contributions. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

KZ was supported by the AXA Research Fund. IM was supported by the National Science Foundation. ES and MB were supported by the Research Council of Norway (RCN; 288083). ES and AV were supported by the The Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (NWO; NWA 400.17.602 Startimpulse grant). JH was supported by NWO [406-11-019 ResearchTalent Grant]. AD was supported by NWO [464-15-176 Open Research Area (ORA) grant] and the Social Resilience and Security Program (Leiden University). LW was supported by NWO (024.001.003 Gravitation grant). EC was supported by the European Research Council (ERC; StG-263234 Starting grant and CoG-681632 Consolidator grant) and NWO (453-14-001 Vici grant). BG was supported by NWO (VENI 451-10-021 Veni grant).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

- ^ http://www.kijkinjebrein.nl/

Ambrosino, S., De Zeeuw, P., Wierenga, L. M., van Dijk, S., and Durston, S. (2017). What can cortical development in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder teach us about the early developmental mechanisms involved? Cereb. Cortex 27, 4624–4634. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhx182

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Andrews, J. L., Ahmed, S. P., and Blakemore, S.-J. (2021). Navigating the social environment in adolescence: the role of social brain development. Biol. Psychiatry 89, 109–118. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2020.09.012

Asscheman, J. S., Koot, S., Ma, I., Buil, J. M., Krabbendam, L., Cillessen, A. H. N., et al. (2019). Heightened neural sensitivity to social exclusion in boys with a history of low peer preference during primary school. Dev. Cogn. Neurosci. 38:100673. doi: 10.1016/j.dcn.2019.100673

Asscheman, J. S., Zanolie, K., Bexkens, A., and Bos, M. G. (2021). Mood variability among early adolescents in times of social constraints: a daily diary study during the COVID-19 pandemic. Front. Psychol. 12:722494. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.722494

Baek, E. C., Porter, M. A., and Parkinson, C. (2021). Social network analysis for social neuroscientists. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 16, 883–901. doi: 10.1093/scan/nsaa069

Berg, J., Dickhaut, J., and McCabe, K. (1995). Trust, reciprocity and social history. Games Econ. Behav. 10, 122–142. doi: 10.1006/game.1995.1027

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Blakemore, S.-J., and Mills, K. L. (2014). Is adolescence a sensitive period for sociocultural processing? Ann. Rev. Psychol. 65, 187–207. doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-010213-115202

Blakemore, S.-J. (2018). Inventing Ourselves: The Secret Life of the Teenage Brain. Ealing, London: Transworld Publishers Ltd.

Google Scholar

Bos, M. G., Wierenga, L. M., Blankenstein, N. E., Schreuders, E., Tamnes, C. K., and Crone, E. A. (2018a). Longitudinal structural brain development and externalizing behavior in adolescence. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 59, 1061–1072. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12972

Bos, M. G., Peters, S., van de Kamp, F. C., Crone, E. A., and Tamnes, C. K. (2018b). Emerging depression in adolescence coincides with accelerated frontal cortical thinning. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 59, 994–1002. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12895

Breaux, R., Dvorsky, M. R., Marsh, N. P., Green, C. D., Cash, A. R., Shroff, D. M., et al. (2021). Prospective impact of COVID-19 on mental health functioning in adolescents with and without ADHD: protective role of emotion regulation abilities. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 62, 1132–1139. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.13382

Camerer, C. F. (2011). Behavioral Game Theory: Experiments in Strategic Interaction. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Caspi, A., Houts, R. M., Ambler, A., Danese, A., Elliott, M. L., Hariri, A., et al. (2020). Longitudinal assessment of mental health disorders and comorbidities across 4 decades among participants in the Dunedin birth cohort study. JAMA Netw. Open 3:e203221. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.3221

Chein, J., Albert, D., O’Brien, L., Uckert, K., and Steinberg, L. (2011). Peers increase adolescent risk taking by enhancing activity in the brain’s reward circuitry. Dev. Sci. 14, F1–F10. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2010.01035.x

Crone, E. (2018). Het Puberende Brein: Over de Ontwikkeling van de Hersenen in de Unieke Periode van de Adolescentie. Amsterdam: Prometheus.

Crone, E. A., Achterberg, M., Dobbelaar, S., Euser, S., van den Bulk, B., van der Meulen, M., et al. (2020). Neural and behavioral signatures of social evaluation and adaptation in childhood and adolescence: the Leiden consortium on individual development (L-CID). Dev. Cogn. Neurosci. 45:100805. doi: 10.1016/j.dcn.2020.100805

Crone, E. A., and Dahl, R. E. (2012). Understanding adolescence as a period of social-affective engagement and goal flexibility. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 13, 636–650. doi: 10.1038/nrn3313

Crone, E. A., and Fuligni, A. J. (2020). Self and others in adolescence. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 71, 447–469. doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-010419-050937

Dahl, R. E., Allen, N. B., Wilbrecht, L., and Suleiman, A. B. (2018). Importance of investing in adolescence from a developmental science perspective. Nature 554, 441–450. doi: 10.1038/nature25770

Dalsgaard, S., Thorsteinsson, E., Trabjerg, B. B., Schullehner, J., Plana-Ripoll, O., Brikell, I., et al. (2020). Incidence rates and cumulative incidences of the full spectrum of diagnosed mental disorders in childhood and adolescence. JAMA Psychiatry 77, 155–164. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2019.3523

Davey, C. G., Yücel, M., and Allen, N. B. (2008). The emergence of depression in adolescence: development of the prefrontal cortex and the representation of reward. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 32, 1–19. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2007.04.016

Dawes, M. (2017). Early adolescents’ social goals and school adjustment. Soc. Psychol. Educ. 20, 299–328. doi: 10.1007/s11218-017-9380-3

De Water, E., Mies, G. W., Ma, I., Mennes, M., Cillessen, A. H., and Scheres, A. (2017). Neural responses to social exclusion in adolescents: effects of peer status. Cortex 92, 32–43. doi: 10.1016/j.cortex.2017.02.018

Ducharme, S., Hudziak, J. J., Botteron, K. N., Ganjavi, H., Lepage, C., Collins, D. L., et al. (2011). Right anterior cingulate cortical thickness and bilateral striatal volume correlate with child behavior checklist aggressive behavior scores in healthy children. Biol. Psychiatry 70, 283–290. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2011.03.015

Esposito, C., Bacchini, D., and Affuso, G. (2019). Adolescent non-suicidal self-injury and its relationships with school bullying and peer rejection. Psychiatry Res. 274, 1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2019.02.018

Fehr, E., and Schmidt, K. M. (1999). A theory of fairness, competition and cooperation. Quart. J. Econ. 114, 817–868. doi: 10.1162/003355399556151

Ferschmann, L., Bos, M. G., Herting, M. M., Mills, K. L., and Tamnes, C. K. (2021). Contextualizing adolescent structural brain development: environmental determinants and mental health outcomes. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 44, 170–176. doi: 10.1016/j.copsyc.2021.09.014

Fuligni, A. J. (2019). The need to contribute during adolescence. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 14, 331–343. doi: 10.1177/1745691618805437

Gotlieb, R., Hickey-Moody, A., Güroğlu, B., Burnard, P., Horn, C., Willcox, M., et al. (2022). “The social and emotional foundations of learning,” in Education and the Learning Experience in Reimagining Education: The International Science and Evidence Based Education Assessment , eds S. Bugden, G. Borst, A. K. Duraiappah, and N. M. vanAtteveldt (New Delhi: UNESCO MGIEP).

Green, K. H., van de Groep, S., Sweijen, S. W., Becht, A. I., Buijzen, M., de Leeuw, R. N., et al. (2021). Mood and emotional reactivity of adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic: short-term and long-term effects and the impact of social and socioeconomic stressors. Sci. Rep. 11:11563. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-90851-x

Güroğlu, B. (2021). Adolescent brain in a social world: unravelling the positive power of peers from a neurobehavioral perspective. Eur. J. Dev. Psychol. 18, 471–493. doi: 10.1080/17405629.2020.1813101

Güroğlu, B. (2022). The power of friendship: developmental significance of friendships from a neuroscience perspective. Child Dev. Perspect.

Güroğlu, B., Haselager, G. J., van Lieshout, C. F., Takashima, A., Rijpkema, M., and Fernández, G. (2008). Why are friends special? Implementing a social interaction simulation task to probe the neural correlates of friendship. Neuroimage 39, 903–910. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.09.007

Güroğlu, B., and Veenstra, R. (2021). Neural underpinnings of peer experiences and interactions: A review of social neuroscience. Merrill-Palm. Quart. 67, 416–455. doi: 10.13110/merrpalmquar1982.67.4.0416

Güroğlu, B., van den Bos, W., and Crone, E. A. (2009). Fairness considerations: increasing understanding of intentionality during adolescence. J. Exp. Child Psychol. 104, 398–409. doi: 10.1016/j.jecp.2009.07.002

Güroğlu, B., van den Bos, W., and Crone, E. A. (2014). Sharing and giving across adolescence: an experimental study examining the development of prosocial behavior. Front. Psychol. 5:291. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00291

Kessler, R. C., Angermeyer, M., Anthony, J. C., De Graaf, R., Demyttenaere, K., Gasquet, I., et al. (2007). Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of mental disorders in the world health organization’s world mental health survey initiative. World Psychiatry 6, 168–176.

PubMed Abstract | Google Scholar

Klootwijk, C. L., Koele, I. J., van Hoorn, J., Güroğlu, B., and van Duijvenvoorde, A. C. (2021). Parental support and positive mood buffer adolescents’ academic motivation during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Res. Adolesc. 31, 780–795. doi: 10.1111/jora.12660

Lamblin, M., Murawski, C., Whittle, S., and Fornito, A. (2017). Social connectedness, mental health and the adolescent brain. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 80, 57–68. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2017.05.010

Laursen, B., and Veenstra, R. (2021). Toward understanding the functions of peer influence: A summary and synthesis of recent empirical research. J. Res. Adolesc. 31, 889–907. doi: 10.1111/jora.12606

Lockwood, P. L., Apps, M. A., Valton, V., Viding, E., and Roiser, J. P. (2016). Neurocomputational mechanisms of prosocial learning and links to empathy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 113, 9763–9768. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1603198113

Luby, J. L., Belden, A. C., Jackson, J. J., Lessov-Schlaggar, C. N., Harms, M. P., Tillman, R., et al. (2016). Early childhood depression and alterations in the trajectory of gray matter maturation in middle childhood and early adolescence. JAMA Psychiatry 73, 31–38. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.2356

Ma, I., Lambregts-Rommelse, N. N., Buitelaar, J. K., Cillessen, A. H., and Scheres, A. P. (2017). Decision-making in social contexts in youth with ADHD. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 26, 335–344. doi: 10.1007/s00787-016-0895-5

Ma, I., Westhoff, B., and van Duijvenvoorde, A. C. (2020). The cognitive mechanisms that drive social belief updates during adolescence. bioRxiv [Preprint] doi: 10.1101/2020.05.19.105114

Masten, C. L., Eisenberger, N. I., Pfeifer, J. H., and Dapretto, M. (2013). Neural responses to witnessing peer rejection after being socially excluded: FMRI as a window into adolescents’ emotional processing. Dev. Sci. 16, 743–759. doi: 10.1111/desc.12056

Meuwese, R., Braams, B. R., and Güroğlu, B. (2018). What lies beneath peer acceptance in adolescence? Exploring the role of nucleus accumbens responsivity to self-serving and vicarious rewards. Dev. Cogn. Neurosci. 34, 124–129. doi: 10.1016/j.dcn.2018.07.004

Meuwese, R., Crone, E. A., de Rooij, M., and Güroğlu, B. (2015). Development of equity preferences in boys and girls across adolescence. Child Dev. 86, 145–158. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12290

Mills, K. L., Siegmund, K. D., Tamnes, C. K., Ferschmann, L., Wierenga, L. M., Bos, M. G., et al. (2021). Inter-individual variability in structural brain development from late childhood to young adulthood. Neuroimage 242:118450. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2021.118450

Nelson, E. E., Jarcho, J. M., and Guyer, A. E. (2016). Social re-orientation and brain development: An expanded and updated view. Dev. Cogn. Neurosci. 17, 118–127. doi: 10.1016/j.dcn.2015.12.008

Nelson, E. E., Leibenluft, E., McClure, E. B., and Pine, D. S. (2005). The social re-orientation of adolescence: A neuroscience perspective on the process and its relation to psychopathology. Psychol. Med. 35, 163–174. doi: 10.1017/s0033291704003915

Nussenbaum, K., and Hartley, C. A. (2019). Reinforcement learning across development: what insights can we draw from a decade of research? Dev. Cogn. Neurosci. 40:100733. doi: 10.1016/j.dcn.2019.100733

Oostermeijer, S., Whittle, S., Suo, C., Allen, N., Simmons, J., Vijayakumar, N., et al. (2016). Trajectories of adolescent conduct problems in relation to cortical thickness development: A longitudinal MRI study. Transl. Psychiatry 6:e841. doi: 10.1038/tp.2016.111

Orben, A., Tomova, L., and Blakemore, S.-J. (2020). The effects of social deprivation on adolescent development and mental health. Lancet Child Adolesc. Health 4, 634–640. doi: 10.1016/S2352-4642(20)30186-3

Paus, T., Keshavan, M., and Giedd, J. N. (2008). Why do many psychiatric disorders emerge during adolescence? Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 9, 947–957. doi: 10.1038/nrn2513

Peters, S., Peper, J. S., Van Duijvenvoorde, A. C., Braams, B. R., and Crone, E. A. (2017). Amygdala-orbitofrontal connectivity predicts alcohol use two years later: A longitudinal neuroimaging study on alcohol use in adolescence. Dev. Sci. 20:e12448. doi: 10.1111/desc.12448

Pfeifer, J. H., and Allen, N. B. (2021). Puberty initiates cascading relationships between neurodevelopmental, social and internalizing processes across adolescence. Biol. Psychiatry 89, 99–108. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2020.09.002

Platt, B., Kadosh, K. C., and Lau, J. Y. (2013). The role of peer rejection in adolescent depression. Depress. Anxiety 30, 809–821. doi: 10.1002/da.22120

Sawyer, S. M., Azzopardi, P. S., Wickremarathne, D., and Patton, G. C. (2018). The age of adolescence. Lancet Child Adolesc. Health 2, 223–228. doi: 10.1016/S2352-4642(18)30022-1

Schreuders, E., Braams, B., Crone, E. A., and Güroğlu, B. (2021). Friendship stability in adolescence is associated with ventral striatum responses to vicarious rewards. Nat. Commun. 12:313. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-20042-1

Schreuders, E., Klapwijk, E. T., Will, G.-J., and Güroğlu, B. (2018). Friend versus foe: neural correlates of prosocial decisions for liked and disliked peers. Cogn. Affect. Behav. Neurosci. 18, 127–142. doi: 10.3758/s13415-017-0557-1

Schreuders, E., Smeekens, S., Cillessen, A. H., and Güroğlu, B. (2019). Friends and foes: neural correlates of prosocial decisions with peers in adolescence. Neuropsychologia 129, 153–163. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2019.03.004

Solmi, M., Radua, J., Olivola, M., Croce, E., Soardo, L., de Pablo, G. S., et al. (2021). Age at onset of mental disorders worldwide: large-scale meta-analysis of 192 epidemiological studies. Mol. Psychiatry [Online ahead of print]. doi: 10.1038/s41380-021-01161-7

Somerville, L. H., Jones, R. M., and Casey, B. (2010). A time of change: Behavioral and neural correlates of adolescent sensitivity to appetitive and aversive environmental cues. Brain Cogn. 72, 124–133. doi: 10.1016/j.bandc.2009.07.003

Somerville, L. H., Jones, R. M., Ruberry, E. J., Dyke, J. P., Glover, G., and Casey, B. J. (2013). The medial prefrontal cortex and the emergence of self-conscious emotion in adolescence. Psychol. Sci. 24, 1554–1562. doi: 10.1177/0956797613475633

Steinberg, L. (2008). A social neuroscience perspective on adolescent risk-taking. Dev. Rev. 28, 78–106. doi: 10.1016/j.dr.2007.08.002

Steinberg, L., and Morris, A. S. (2001). Adolescent development. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 52, 83–110. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.83

Sutton, R. S., and Barto, A. G. (2018). Reinforcement Learning: An Introduction. Cambridge, MA: MIT press.

Van de Groep, S., Zanolie, K., Green, K. H., Sweijen, S. W., and Crone, E. A. (2020). A daily diary study on adolescents’ mood, empathy and prosocial behavior during the COVID-19 pandemic. PLoS One 15:e0240349. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0240349

Van den Bos, W., Crone, E. A., Meuwese, R., and Güroğlu, B. (2018). Social network cohesion in school classes promotes prosocial behavior. PLoS One 13:e0194656. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0194656

Van den Bos, W., van Dijk, E., Westenberg, M., Rombouts, S. A., and Crone, E. A. (2011). Changing brains, changing perspectives: the neurocognitive development of reciprocity. Psychol. Sci. 22, 60–70. doi: 10.1177/0956797610391102

Van Harmelen, A.-L., Blakemore, S. J., Goodyer, I. M., and Kievet, R. A. (2021). The interplay between adolescent friendships and resilience following childhood and adolescent adversity. Adv. Res. Sci. 2, 37–50. doi: 10.1007/s42844-020-00027-1

Van Harmelen, A.-L., Kievit, R., Ioannidis, K., Neufeld, S., Jones, P., Bullmore, E., et al. (2017). Adolescent friendships predict later resilient functioning across psychosocial domains in a healthy community cohort. Psychol. Med. 47, 2312–2322. doi: 10.1017/S0033291717000836

Van Hoorn, J., Shablack, H., Lindquist, K. A., and Telzer, E. H. (2019). Incorporating the social context into neurocognitive models of adolescent decision-making: A neuroimaging meta-analysis. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 101, 129–142. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2018.12.024

Van Hoorn, J., Van Dijk, E., Güroğlu, B., and Crone, E. A. (2016). Neural correlates of prosocial peer influence on public goods game donations during adolescence. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 11, 923–933. doi: 10.1093/scan/nsw013

Vandenbroucke, A. R., Crone, E. A., van Erp, J. B., Güroğlu, B., Hulshoff Pol, H., de Kogel, K., et al. (2021). Integrating cognitive developmental neuroscience in society: lessons learned from a multidisciplinary research project on education and social safety of youth. Front. Integr. Neurosci. 15:756640. doi: 10.3389/fnint.2021.756640

Veenstra, R., and Laninga-Wijnen, L. (2022). Peer network studies and interventions in adolescence. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 44, 157–163. doi: 10.1016/j.copsyc.2021.09.015

Vijayakumar, N., Whittle, S., Dennison, M., Yücel, M., Simmons, J., and Allen, N. B. (2014). Development of temperamental effortful control mediates the relationship between maturation of the prefrontal cortex and psychopathology during adolescence: A 4-year longitudinal study. Dev. Cogn. Neurosci. 9, 30–43. doi: 10.1016/j.dcn.2013.12.002

Vitaro, F., Boivin, M., and Bukowski, W. M. (2009). “The role of friendship in child and adolescent psychosocial development,” in Handbook of Peer Interactions, Relationships and Groups , eds K. H. Rubin, W. M. Bukowski, and B. Laursen (New York, NY: The Guilford Press), 568–585.

Westhoff, B., Blankenstein, N. E., Schreuders, E., Crone, E. A., and Van Duijvenvoorde, A. C. (2021). Increased ventromedial prefrontal cortex activity in adolescence benefits prosocial reinforcement learning. bioRxiv [Preprint]. doi: 10.1101/2021.01.21.427660

Westhoff, B., Koele, I. J., and van de Groep, I. H. (2020a). Social learning and the brain: how do we learn from and about other people? Front. Young Minds 8:95. doi: 10.3389/frym.2020.00095

Westhoff, B., Molleman, L., Viding, E., van den Bos, W., and van Duijvenvoorde, A. C. (2020b). Developmental asymmetries in learning to adjust to cooperative and uncooperative environments. Sci. Rep. 10:21761. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-78546-1

Whitmore, L. B., and Mills, K. L. (2021). Co-creating developmental science. Infant. Child Dev. doi: 10.1002/icd.2273

Whittle, S., Lichter, R., Dennison, M., Vijayakumar, N., Schwartz, O., Byrne, M. L., et al. (2014). Structural brain development and depression onset during adolescence: a prospective longitudinal study. Am. J. Psychiatry 171, 564–571. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2013.13070920

Wierenga, L. M., Langen, M., Ambrosino, S., van Dijk, S., Oranje, B., and Durston, S. (2014a). Typical development of basal ganglia, hippocampus, amygdala and cerebellum from age 7 to 24. Neuroimage 96, 67–72. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2014.03.072

Wierenga, L. M., Langen, M., Oranje, B., and Durston, S. (2014b). Unique developmental trajectories of cortical thickness and surface area. Neuroimage 87, 120–126. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2013.11.010

Will, G.-J., Crone, E. A., van Lier, P. A., and Güroğlu, B. (2018). Longitudinal links between childhood peer acceptance and the neural correlates of sharing. Dev. Sci. 21:e12489. doi: 10.1111/desc.12489

Will, G.-J., and Güroğlu, B. (2016). “A neurocognitive perspective on the development of social decision-making,” in Neuroeconomics , eds M. Reuter, and C. Montag (Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer), 293–309. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-35923-1_15

Will, G.-J., van Lier, P. A., Crone, E. A., and Güroğlu, B. (2016). Chronic childhood peer rejection is associated with heightened neural responses to social exclusion during adolescence. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 44, 43–55. doi: 10.1007/s10802-015-9983-0

Wilson, R. C., and Collins, A. G. (2019). Ten simple rules for the computational modeling of behavioral data. eLife 8:e49547. doi: 10.7554/eLife.49547

Yeager, D. S., Dahl, R. E., and Dweck, C. (2018). Why interventions to influence adolescent behavior often fail but could succeed. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 13, 101–122. doi: 10.1177/1745691617722620

Zanolie, K., and Crone, E. A. (2021). Ranking status differentially affects rejection sensitivity in adolescence: an event-related potential study. Neuropsychologia 162:108020. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2021.108020

Zanolie, K., de Cremer, D., Güroğlu, B., and Crone, E. A. (2015). Rejection in bargaining situations: an event-related potential study in adolescents and adults. PLoS One 10:e0139953. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0139953

Zisook, S., Lesser, I., Stewart, J. W., Wisniewski, S. R., Balasubramani, G., Fava, M., et al. (2007). Effect of age at onset on the course of major depressive disorder. Am. J. Psychiatry 164, 1539–1546. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.06101757

Keywords: adolescence, brain development, social development, mental wellbeing, team science

Citation: Zanolie K, Ma I, Bos MGN, Schreuders E, Vandenbroucke ARE, van Hoorn J, van Duijvenvoorde ACK, Wierenga L, Crone EA and Güroğlu B (2022) Understanding the Dynamics of the Developing Adolescent Brain Through Team Science. Front. Integr. Neurosci. 16:827097. doi: 10.3389/fnint.2022.827097

Received: 01 December 2021; Accepted: 31 January 2022; Published: 22 February 2022.

Reviewed by:

Copyright © 2022 Zanolie, Ma, Bos, Schreuders, Vandenbroucke, van Hoorn, van Duijvenvoorde, Wierenga, Crone and Güroğlu. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY) . The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Kiki Zanolie, [email protected]

† These authors have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Child and Adolescent Development

- First Online: 28 January 2017

Cite this chapter

- Rosalyn H. Shute 3 &

- John D. Hogan 4

11k Accesses

For school psychologists, understanding how children and adolescents develop and learn forms a backdrop to their everyday work, but the many new ‘facts’ shown by empirical studies can be difficult to absorb; nor do they make sense unless brought together within theoretical frameworks that help to guide practice. In this chapter, we explore the idea that child and adolescent development is a moveable feast, across both time and place. This is aimed at providing a helpful perspective for considering the many texts and papers that do focus on ‘facts’. We outline how our understanding of children’s development has evolved as various schools of thought have emerged. While many of the traditional theories continue to provide useful educational, remedial and therapeutic frameworks, there is also a need to take a more critical approach that supports multiple interpretations of human activity and development. With this in mind, we re-visit the idea of norms and milestones, consider the importance of context, reflect on some implications of psychology’s current biological zeitgeist and note a growing movement promoting the idea that we should be listening more seriously to children’s own voices.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

Subscribe and save.

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or eBook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

School-Age Development

Children’s Developmental Needs During the Transition to Kindergarten: What Can Research on Social-Emotional, Motivational, Cognitive, and Self-Regulatory Development Tell Us?

Transition to School from the Perspective of the Girls’ and Boys’ Parents

Achenbach, T. M. (2009). The Achenbach system of empirically based assessment (ASEBA): Development, findings, theory, and applications . Burlington, VT: Research Center for Children, Youth and Families, University of Vermont.

Google Scholar

Ainsworth, M. D., & Bell, S. M. (1970). Attachment, exploration, and separation: Illustrated by the behavior of one-year-olds in a strange situation. Child Development, 41 , 49–67.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, (DSM-5) (5th ed.). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association.

Book Google Scholar

Ames, L. B. (1996). Louise bates Ames. In D. N. Thompson & J. D. Hogan (Eds.), A history of developmental psychology in autobiography (pp. 1–23). Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

Anderson, V., Spencer-Smith, M., & Wood, A. (2011). Do children really recover better? Neurobehavioural plasticity after early brain insult. Brain, 134 , 2197–2221. doi: 10.1093/brain/awr103 .

Annan, J., & Priestley, A. (2011). A contemporary story of school psychology. School Psychology International, 33 (3), 325–344. doi: 10.1177/0143034311412845 .

Article Google Scholar

Aries, P. (1962). Centuries of childhood: A social history of family life (R. Baldick, Trans.). New York: Random House.

Arnett, J. J. (2007). Emerging adulthood: What is it, and what is it good for? Child Development Perspectives, 1 (2), 68–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-8606.2007.00016.x .

Arnett, J. J. (2013). The evidence for Generation We and against Generation Me. Emerging adulthood, 1 , 5–10. doi: 10.1177/2167696812466842 .

Bandura, A., & Walters, R. H. (1963). Social learning and personality development . New York: Holt Rinehart and Winston.

Bjorklund, D. E., & Pellegrini, A. D. (2002). The origins of human nature: Evolutionary developmental psychology . Washington, DC: APA.

Bowlby, J. (1969). Attachment and loss (Vol. 1). New York: Basic Books.

Boyce, W. T., & Ellis, B. J. (2005). Biological sensitivity to context: I. An evolutionary developmental theory of the origins and function of stress reactivity. Development and Psychopathology, 17 , 271–301. doi: 10.1017/S0954579405050145 .

British Psychological Society. (2011). Response to the American Psychiatric Association: DSM-5 development . Retrieved January 16, 2015, from http://www.bps.org.uk/news/british-psychological-still-has-concerns-over-dsm-v

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The ecology of human development: Experiments by nature and design . Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Bronfenbrenner, U., & Morris, P. A. (1998). Chapter 17: The ecology of developmental processes. In R. M. Lerner (Ed.), Handbook of child psychology: Theoretical models of human development (5th ed., Vol. 1, pp. 535–584). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Burman, E. (2008). Deconstructing developmental psychology . London: Routledge. (Original work published 1994)

Burns, M. K. (2011). School psychology research: Combining ecological theory and prevention science. School Psychology Review, 40 (1), 132–139.

Byers, L., Kulitja, S., Lowell, A., & Kruske, S. (2012). ‘Hear our stories’: Child-rearing practices of a remote Australian Aboriginal community. Australian Journal of Rural Health, 20 , 293–297. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1584.2012.01317.x .

Cefai, C. (2011). Chapter 2: A framework for the promotion of social and emotional wellbeing in primary schools. In R. H. Shute, P. T. Slee, R. Murray-Harvey, & K. L. Dix (Eds.), Mental health and wellbeing: Educational perspectives (pp. 17–28). Adelaide: Shannon Research press.

Chomsky, N. (1957). Syntactic structures . The Hague/Paris: Mouton.

Copple, C., & Bredekamp, S. (Eds.). (2009). Developmentally appropriate practice in early childhood programs . Washington, DC: National Association for the Education of Young Children.

Crain, W. (2010). Theories of development: Concepts and applications (6th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson.

Darwin, C. (1877). A biographical sketch of an infant. Mind, 2 , 285–294.

Dekker, S., Lee, N. C., Howard-Jones, P., & Jolles, J. (2012). Neuromyths in education: Prevalence and predictors of misconceptions among teachers. Frontiers in Psychology, 3 , Article 429. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2012.00429

Department of Education and Training, Victoria. (2005). Research on learning: Implications for teaching. Edited and abridged extracts . Melbourne: DET. Retrieved October 8, 2014, from www.det.vic.gov.au

Elkind, D. (2011). Developmentally appropriate practice: Curriculum and development in early education (C. Gestwicki, Guest editorial, 4th ed.). Belmont, CA: Wadsworth.

Erikson, E. (1950). Childhood and society . New York: Norton.

Freud, S. (2005). The unconscious . London, UK: Penguin.

Goodman, R., & Scott, S. (1999). Comparing the strengths and difficulties questionnaire and the child behavior checklist: Is small beautiful? Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 27 , 17–24.

Gredler, M. E. (2012). Understanding Vygotsky for the classroom: Is it too late? Educational Psychology Review, 24 , 113–131. doi: 10.1007/s10648-011-9183-6 .

Greene, S. (2006). Child psychology: Taking account of children at last? The Irish Journal of Psychology, 27 (1/2), 8–15.

Guenther, J. (2015). Analysis of national test scores in very remote Australian schools: Understanding the results through a different lens. In H. Askell-Williams (Ed.), Transforming the future of learning with educational research . Hershey, PA: IGI Global.

Hall, G. S. (1883). The contents of children’s minds. Princeton Review, 11 , 249–272.

Hall, G. S. (1904). Adolescence: Its psychology and its relation to physiology, anthropology, sociology, sex, crime, religion, and education (Vol. 1–2). New York: D. Appleton.

Heary, C., & Guerin, S. (2006). Research with children in psychology: The value of a child-centred approach. The Irish Journal of Psychology, 27 (1/2), 6–7.

Hindman, H. D. (2002). Child labor: An American history . Armonk, NY: M. E. Sharpe.

Hogan, J. D. (2003). G. Stanley Hall: Educator, innovator, pioneer of developmental psychology. In G. Kimble & M. Wertheimer (Eds.), Portraits of pioneers in psychology (Vol. V, pp. 19–36). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Iossifova, R., & Marmolejo-Ramos, F. (2013). When the body is time: Spatial and temporal deixis in children with visual impairments and sighted children. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 34 , 2173–2184.

Jantz, P. B., & Plotts, C. A. (2014). Integrating neuropsychology and school psychology: Potential and pitfalls. Contemporary School Psychology, 18 , 69–80. doi: 10.1007/s40688-013-0006-2 .

Jarvis, J. (2011). Chapter 20: Promoting mental health through inclusive pedagogy. In R. H. Shute, P. T. Slee, R. Murray-Harvey, & K. L. Dix (Eds.), Mental health and wellbeing: Educational perspectives (pp. 237–248). Adelaide: Shannon Research press.

Jiang, X., Kosher, H., Ben-Arieh, A., & Huebner, E. S. (2014). Children’s rights, school psychology, and well-being assessments. Social Indicators Research, 117 , 179–193. doi: 10.1007/s11205-013-0343-6 .