Research to Action

The Global Guide to Research Impact

Social Media

Framing challenges

Synthetic literature reviews: An introduction

By Steve Wallis and Bernadette Wright 26/05/2020

Whether you are writing a funding proposal or an academic paper, you will most likely be required to start with a literature review of some kind. Despite (or because of) the work involved, a literature review is a great opportunity to showcase your knowledge on a topic. In this post, we’re going to take it one step further. We’re going to tell you a very practical approach to conducting literature reviews that allows you to show that you are advancing scientific knowledge before your project even begins. Also – and this is no small bonus – this approach lets you show how your literature review will lead to a more successful project.

Literature review – start with the basics

A literature review helps you shape effective solutions to the problems you (and your organisation) are facing. A literature review also helps you demonstrate the value of your activities. You can show how much you add to the process before you spend any money collecting new data. Finally, your literature review helps you avoid reinventing the wheel by showing you what relevant research already exists, so that you can target your new research more efficiently and more effectively.

We all want to conduct good research and have a meaningful impact on people’s lives. To do this, a literature review is a critical step. For funders, a literature review is especially important because it shows how much useful knowledge the writer already has.

Past methods of literature reviews tend to be focused on ‘muscle power’, that is spending more time and more effort to review more papers and adhering more closely to accepted standards. Examples of standards for conducting literature reviews include the PRISMA Statement for Reporting Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses of Studies That Evaluate Health Care Interventions and the guidelines for assessing the quality and applicability of systematic reviews developed by the Task Force on Systematic Review and Guidelines . Given the untold millions of papers in many disciplines, even a large literature review that adheres to the best guidelines does little to move us toward integrated knowledge in and across disciplines.

In short, we need we need to work smarter, not harder!

Synthetic literature reviews

One approach that can provide more benefit is the synthetic literature review. Synthetic meaning synthesised or integrated, not artificial. Rather than explaining and reflecting on the results of previous studies (as is typically done in literature reviews), a synthetic literature review strives to create a new and more useful theoretical perspective by rigorously integrating the results of previous studies.

Many people find the process of synthesis difficult, elusive, or mysterious. When presenting their views and making recommendations for research, they tend to fall back on intuition (which is neither harder nor smarter).

After defining your research topic (‘poverty’ for example), the next step is to search the literature for existing theories or models of poverty that have been developed from research. You can use Google Scholar or your institutional database, or the assistance of a research librarian. A broad topic such as ‘poverty’, however, will lead you to millions of articles. You’ll narrow that field by focusing more closely on your topic and adding search terms. For example, you might be more interested in poverty among Latino communities in central California. You might also focus your search according to the date of the study (often, but not always, more recent results are preferred), or by geographic location. Continue refining and focusing your search until you have a workable number of papers (depending on your available time and resources). You might also take this time to throw out the papers that seem to be less relevant.

Skim those papers to be sure that they are really relevant to your topic. Once you have chosen a workable number of relevant papers, it is time to start integrating them.

Next, sort them according to the quality of their data.

Next, read the theory presented in each paper and create a diagram of the theory. The theory may be found in a section called ‘theory’ or sometimes in the ‘introduction’. For research papers, that presented theory may have changed during the research process, so you should look for the theory in the ‘findings’, ‘results’, or ‘discussion’ sections.

That diagram should include all relevant concepts from the theory and show the causal connections between the concepts that have been supported by research (some papers will present two theories, one before and one after the research – use the second one – only the hypotheses that have been supported by the research).

For a couple of brief and partial example from a recent interdisciplinary research paper, one theory of poverty might say ‘Having more education will help people to stay out of poverty’, while another might say ‘The more that the economy develops, the less poverty there will be’.

We then use those statements to create a diagram as we have in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Two (simple, partial) theories of poverty. (We like to use dashed lines to indicate ’causes less’, and solid lines to indicate ’causes more’)

When you have completed a diagram for each theory, the next step is to synthesise (integrate) them where the concepts are the same (or substantively similar) between two or more theories. With causal diagrams such as these, the process of synthesis becomes pretty direct. We simply combine the two (or more) theories to create a synthesised theory, such as in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Two theories synthesised where they overlap (in this case theories of poverty)

Much like a road map, a causal diagram of a theory with more concepts and more connecting arrows is more useful for navigation. You can show that your literature review is better than previous reviews by showing that you have taken a number of fragmented theories (as in Figure 1) and synthesised them to create a more coherent theory (as in Figure 2).

To go a step further, you may use Integrative Propositional Analysis (IPA) to quantify the extent to which your research has improved the structure and potential usefulness of your knowledge through the synthesis. Another source is our new book from Practical Mapping for Applied Research and Program Evaluation (see especially Chapter 5). (For the basics, you can look at Chapter One for free on the publisher’s site by clicking on the ‘Preview’ tab here. )

Once you become comfortable with the process, you will certainly be working ‘smarter’ and showcasing your knowledge to funders!

Contribute Write a blog post, post a job or event, recommend a resource

Partner with Us Are you an institution looking to increase your impact?

Most Recent Posts

- Seven lessons about impact case studies from REF 2021

- 1-2-4-all, the atomic bomb of Liberating Structures (LS under the lens)

- How to co-produce a research project

- How to design a research uptake plan

- Development and Outreach Officer: Girls not Brides

This Week's Most Read

- How to write actionable policy recommendations

- What do we mean by ‘impact’?

- AEN Evidence 23 – Online Access Registration now open!

- Gap analysis for literature reviews and advancing useful knowledge

- How to develop input, activity, output, outcome and impact indicators

- Outcome Mapping: A Basic Introduction

- 12ft Ladder: Making research accessible

- AI in Research: Its Uses and Limitations

- Policymaker, policy maker, or policy-maker?

- Stakeholder Engagement a Tool to Measure Public Policy

Research To Action (R2A) is a learning platform for anyone interested in maximising the impact of research and capturing evidence of impact.

The site publishes practical resources on a range of topics including research uptake, communications, policy influence and monitoring and evaluation. It captures the experiences of practitioners and researchers working on these topics and facilitates conversations between this global community through a range of social media platforms.

R2A is produced by a small editorial team, led by CommsConsult . We welcome suggestions for and contributions to the site.

Subscribe to our newsletter!

Our contributors

Browse all authors

Friends and partners

- Global Development Network (GDN)

- Institute of Development Studies (IDS)

- International Initiative for Impact Evaluation (3ie)

- On Think Tanks

- Politics & Ideas

- Research for Development (R4D)

- Research Impact

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates

How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates

Published on January 2, 2023 by Shona McCombes . Revised on September 11, 2023.

What is a literature review? A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources on a specific topic. It provides an overview of current knowledge, allowing you to identify relevant theories, methods, and gaps in the existing research that you can later apply to your paper, thesis, or dissertation topic .

There are five key steps to writing a literature review:

- Search for relevant literature

- Evaluate sources

- Identify themes, debates, and gaps

- Outline the structure

- Write your literature review

A good literature review doesn’t just summarize sources—it analyzes, synthesizes , and critically evaluates to give a clear picture of the state of knowledge on the subject.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

What is the purpose of a literature review, examples of literature reviews, step 1 – search for relevant literature, step 2 – evaluate and select sources, step 3 – identify themes, debates, and gaps, step 4 – outline your literature review’s structure, step 5 – write your literature review, free lecture slides, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions, introduction.

- Quick Run-through

- Step 1 & 2

When you write a thesis , dissertation , or research paper , you will likely have to conduct a literature review to situate your research within existing knowledge. The literature review gives you a chance to:

- Demonstrate your familiarity with the topic and its scholarly context

- Develop a theoretical framework and methodology for your research

- Position your work in relation to other researchers and theorists

- Show how your research addresses a gap or contributes to a debate

- Evaluate the current state of research and demonstrate your knowledge of the scholarly debates around your topic.

Writing literature reviews is a particularly important skill if you want to apply for graduate school or pursue a career in research. We’ve written a step-by-step guide that you can follow below.

Don't submit your assignments before you do this

The academic proofreading tool has been trained on 1000s of academic texts. Making it the most accurate and reliable proofreading tool for students. Free citation check included.

Try for free

Writing literature reviews can be quite challenging! A good starting point could be to look at some examples, depending on what kind of literature review you’d like to write.

- Example literature review #1: “Why Do People Migrate? A Review of the Theoretical Literature” ( Theoretical literature review about the development of economic migration theory from the 1950s to today.)

- Example literature review #2: “Literature review as a research methodology: An overview and guidelines” ( Methodological literature review about interdisciplinary knowledge acquisition and production.)

- Example literature review #3: “The Use of Technology in English Language Learning: A Literature Review” ( Thematic literature review about the effects of technology on language acquisition.)

- Example literature review #4: “Learners’ Listening Comprehension Difficulties in English Language Learning: A Literature Review” ( Chronological literature review about how the concept of listening skills has changed over time.)

You can also check out our templates with literature review examples and sample outlines at the links below.

Download Word doc Download Google doc

Before you begin searching for literature, you need a clearly defined topic .

If you are writing the literature review section of a dissertation or research paper, you will search for literature related to your research problem and questions .

Make a list of keywords

Start by creating a list of keywords related to your research question. Include each of the key concepts or variables you’re interested in, and list any synonyms and related terms. You can add to this list as you discover new keywords in the process of your literature search.

- Social media, Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, Snapchat, TikTok

- Body image, self-perception, self-esteem, mental health

- Generation Z, teenagers, adolescents, youth

Search for relevant sources

Use your keywords to begin searching for sources. Some useful databases to search for journals and articles include:

- Your university’s library catalogue

- Google Scholar

- Project Muse (humanities and social sciences)

- Medline (life sciences and biomedicine)

- EconLit (economics)

- Inspec (physics, engineering and computer science)

You can also use boolean operators to help narrow down your search.

Make sure to read the abstract to find out whether an article is relevant to your question. When you find a useful book or article, you can check the bibliography to find other relevant sources.

You likely won’t be able to read absolutely everything that has been written on your topic, so it will be necessary to evaluate which sources are most relevant to your research question.

For each publication, ask yourself:

- What question or problem is the author addressing?

- What are the key concepts and how are they defined?

- What are the key theories, models, and methods?

- Does the research use established frameworks or take an innovative approach?

- What are the results and conclusions of the study?

- How does the publication relate to other literature in the field? Does it confirm, add to, or challenge established knowledge?

- What are the strengths and weaknesses of the research?

Make sure the sources you use are credible , and make sure you read any landmark studies and major theories in your field of research.

You can use our template to summarize and evaluate sources you’re thinking about using. Click on either button below to download.

Take notes and cite your sources

As you read, you should also begin the writing process. Take notes that you can later incorporate into the text of your literature review.

It is important to keep track of your sources with citations to avoid plagiarism . It can be helpful to make an annotated bibliography , where you compile full citation information and write a paragraph of summary and analysis for each source. This helps you remember what you read and saves time later in the process.

Here's why students love Scribbr's proofreading services

Discover proofreading & editing

To begin organizing your literature review’s argument and structure, be sure you understand the connections and relationships between the sources you’ve read. Based on your reading and notes, you can look for:

- Trends and patterns (in theory, method or results): do certain approaches become more or less popular over time?

- Themes: what questions or concepts recur across the literature?

- Debates, conflicts and contradictions: where do sources disagree?

- Pivotal publications: are there any influential theories or studies that changed the direction of the field?

- Gaps: what is missing from the literature? Are there weaknesses that need to be addressed?

This step will help you work out the structure of your literature review and (if applicable) show how your own research will contribute to existing knowledge.

- Most research has focused on young women.

- There is an increasing interest in the visual aspects of social media.

- But there is still a lack of robust research on highly visual platforms like Instagram and Snapchat—this is a gap that you could address in your own research.

There are various approaches to organizing the body of a literature review. Depending on the length of your literature review, you can combine several of these strategies (for example, your overall structure might be thematic, but each theme is discussed chronologically).

Chronological

The simplest approach is to trace the development of the topic over time. However, if you choose this strategy, be careful to avoid simply listing and summarizing sources in order.

Try to analyze patterns, turning points and key debates that have shaped the direction of the field. Give your interpretation of how and why certain developments occurred.

If you have found some recurring central themes, you can organize your literature review into subsections that address different aspects of the topic.

For example, if you are reviewing literature about inequalities in migrant health outcomes, key themes might include healthcare policy, language barriers, cultural attitudes, legal status, and economic access.

Methodological

If you draw your sources from different disciplines or fields that use a variety of research methods , you might want to compare the results and conclusions that emerge from different approaches. For example:

- Look at what results have emerged in qualitative versus quantitative research

- Discuss how the topic has been approached by empirical versus theoretical scholarship

- Divide the literature into sociological, historical, and cultural sources

Theoretical

A literature review is often the foundation for a theoretical framework . You can use it to discuss various theories, models, and definitions of key concepts.

You might argue for the relevance of a specific theoretical approach, or combine various theoretical concepts to create a framework for your research.

Like any other academic text , your literature review should have an introduction , a main body, and a conclusion . What you include in each depends on the objective of your literature review.

The introduction should clearly establish the focus and purpose of the literature review.

Depending on the length of your literature review, you might want to divide the body into subsections. You can use a subheading for each theme, time period, or methodological approach.

As you write, you can follow these tips:

- Summarize and synthesize: give an overview of the main points of each source and combine them into a coherent whole

- Analyze and interpret: don’t just paraphrase other researchers — add your own interpretations where possible, discussing the significance of findings in relation to the literature as a whole

- Critically evaluate: mention the strengths and weaknesses of your sources

- Write in well-structured paragraphs: use transition words and topic sentences to draw connections, comparisons and contrasts

In the conclusion, you should summarize the key findings you have taken from the literature and emphasize their significance.

When you’ve finished writing and revising your literature review, don’t forget to proofread thoroughly before submitting. Not a language expert? Check out Scribbr’s professional proofreading services !

This article has been adapted into lecture slides that you can use to teach your students about writing a literature review.

Scribbr slides are free to use, customize, and distribute for educational purposes.

Open Google Slides Download PowerPoint

If you want to know more about the research process , methodology , research bias , or statistics , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Sampling methods

- Simple random sampling

- Stratified sampling

- Cluster sampling

- Likert scales

- Reproducibility

Statistics

- Null hypothesis

- Statistical power

- Probability distribution

- Effect size

- Poisson distribution

Research bias

- Optimism bias

- Cognitive bias

- Implicit bias

- Hawthorne effect

- Anchoring bias

- Explicit bias

A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources (such as books, journal articles, and theses) related to a specific topic or research question .

It is often written as part of a thesis, dissertation , or research paper , in order to situate your work in relation to existing knowledge.

There are several reasons to conduct a literature review at the beginning of a research project:

- To familiarize yourself with the current state of knowledge on your topic

- To ensure that you’re not just repeating what others have already done

- To identify gaps in knowledge and unresolved problems that your research can address

- To develop your theoretical framework and methodology

- To provide an overview of the key findings and debates on the topic

Writing the literature review shows your reader how your work relates to existing research and what new insights it will contribute.

The literature review usually comes near the beginning of your thesis or dissertation . After the introduction , it grounds your research in a scholarly field and leads directly to your theoretical framework or methodology .

A literature review is a survey of credible sources on a topic, often used in dissertations , theses, and research papers . Literature reviews give an overview of knowledge on a subject, helping you identify relevant theories and methods, as well as gaps in existing research. Literature reviews are set up similarly to other academic texts , with an introduction , a main body, and a conclusion .

An annotated bibliography is a list of source references that has a short description (called an annotation ) for each of the sources. It is often assigned as part of the research process for a paper .

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

McCombes, S. (2023, September 11). How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates. Scribbr. Retrieved June 11, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/dissertation/literature-review/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, what is a theoretical framework | guide to organizing, what is a research methodology | steps & tips, how to write a research proposal | examples & templates, get unlimited documents corrected.

✔ Free APA citation check included ✔ Unlimited document corrections ✔ Specialized in correcting academic texts

- UConn Library

- Literature Review: The What, Why and How-to Guide

- Introduction

Literature Review: The What, Why and How-to Guide — Introduction

- Getting Started

- How to Pick a Topic

- Strategies to Find Sources

- Evaluating Sources & Lit. Reviews

- Tips for Writing Literature Reviews

- Writing Literature Review: Useful Sites

- Citation Resources

- Other Academic Writings

What are Literature Reviews?

So, what is a literature review? "A literature review is an account of what has been published on a topic by accredited scholars and researchers. In writing the literature review, your purpose is to convey to your reader what knowledge and ideas have been established on a topic, and what their strengths and weaknesses are. As a piece of writing, the literature review must be defined by a guiding concept (e.g., your research objective, the problem or issue you are discussing, or your argumentative thesis). It is not just a descriptive list of the material available, or a set of summaries." Taylor, D. The literature review: A few tips on conducting it . University of Toronto Health Sciences Writing Centre.

Goals of Literature Reviews

What are the goals of creating a Literature Review? A literature could be written to accomplish different aims:

- To develop a theory or evaluate an existing theory

- To summarize the historical or existing state of a research topic

- Identify a problem in a field of research

Baumeister, R. F., & Leary, M. R. (1997). Writing narrative literature reviews . Review of General Psychology , 1 (3), 311-320.

What kinds of sources require a Literature Review?

- A research paper assigned in a course

- A thesis or dissertation

- A grant proposal

- An article intended for publication in a journal

All these instances require you to collect what has been written about your research topic so that you can demonstrate how your own research sheds new light on the topic.

Types of Literature Reviews

What kinds of literature reviews are written?

Narrative review: The purpose of this type of review is to describe the current state of the research on a specific topic/research and to offer a critical analysis of the literature reviewed. Studies are grouped by research/theoretical categories, and themes and trends, strengths and weakness, and gaps are identified. The review ends with a conclusion section which summarizes the findings regarding the state of the research of the specific study, the gaps identify and if applicable, explains how the author's research will address gaps identify in the review and expand the knowledge on the topic reviewed.

- Example : Predictors and Outcomes of U.S. Quality Maternity Leave: A Review and Conceptual Framework: 10.1177/08948453211037398

Systematic review : "The authors of a systematic review use a specific procedure to search the research literature, select the studies to include in their review, and critically evaluate the studies they find." (p. 139). Nelson, L. K. (2013). Research in Communication Sciences and Disorders . Plural Publishing.

- Example : The effect of leave policies on increasing fertility: a systematic review: 10.1057/s41599-022-01270-w

Meta-analysis : "Meta-analysis is a method of reviewing research findings in a quantitative fashion by transforming the data from individual studies into what is called an effect size and then pooling and analyzing this information. The basic goal in meta-analysis is to explain why different outcomes have occurred in different studies." (p. 197). Roberts, M. C., & Ilardi, S. S. (2003). Handbook of Research Methods in Clinical Psychology . Blackwell Publishing.

- Example : Employment Instability and Fertility in Europe: A Meta-Analysis: 10.1215/00703370-9164737

Meta-synthesis : "Qualitative meta-synthesis is a type of qualitative study that uses as data the findings from other qualitative studies linked by the same or related topic." (p.312). Zimmer, L. (2006). Qualitative meta-synthesis: A question of dialoguing with texts . Journal of Advanced Nursing , 53 (3), 311-318.

- Example : Women’s perspectives on career successes and barriers: A qualitative meta-synthesis: 10.1177/05390184221113735

Literature Reviews in the Health Sciences

- UConn Health subject guide on systematic reviews Explanation of the different review types used in health sciences literature as well as tools to help you find the right review type

- ~[123]~: Sep 21, 2022 2:16 PM

- ~[124]~: https://guides.lib.uconn.edu/literaturereview

In order to continue enjoying our site, we ask that you confirm your identity as a human. Thank you very much for your cooperation.

Story Arcadia

Syntax in Literature: Defining Structure’s Impact on Meaning

Syntax, in the realm of language and grammar, refers to the set of rules that governs the structure of sentences. It is the arrangement of words and phrases to create well-formed sentences in a language. In literature, syntax is not just a mechanical tool but a powerful element that shapes meaning and influences the reader’s experience.

The significance of syntax in literature extends beyond mere grammatical correctness; it is instrumental in developing tone, mood, and various layers of interpretation. Through deliberate sentence construction, authors can manipulate pacing, emphasize certain themes or ideas, and evoke specific emotional responses from their audience.

Understanding syntax is crucial for both readers and writers as it enhances comprehension and allows for a deeper engagement with texts. By dissecting how sentence structure can affect meaning, readers gain insight into the subtleties of literary expression, while writers can refine their craft to convey complex concepts more effectively. As we explore syntax’s components and its role in literary devices, we uncover the intricate ways in which structure impacts meaning within the rich tapestry of written works. Exploring the Nuances of Syntax in Literature

Syntax, in its essence, refers to the arrangement of words and phrases to create well-formed sentences in a language. This structural framework is not just about grammatical correctness; it’s the backbone that supports the way meaning is conveyed and emotions are expressed in literature. Sentence structure, word order, and punctuation are pivotal components that writers manipulate to bring their narratives to life.

Take, for instance, the opening line from Gabriel García Márquez’s “One Hundred Years of Solitude”: “Many years later, as he faced the firing squad, Colonel Aureliano Buendía was to remember that distant afternoon when his father took him to discover ice.” The sentence structure here—beginning with a future event and circling back to a past memory—creates a sense of timelessness and foreboding that sets the tone for the novel.

Similarly, consider Emily Dickinson’s use of dashes in her poetry. Her unconventional punctuation often forces pauses where none would traditionally be found, creating an introspective rhythm that invites readers to ponder her elusive meanings.

By examining such examples, we see how syntax is not merely a tool for constructing sentences but an art form that shapes our understanding and emotional response to literature. The Influence of Syntax on Meaning and Tone

Syntax isn’t just about the structure of sentences; it’s a powerful tool that shapes meaning and sets the tone in literature. When authors play with the order of words, they can emphasize certain points or stir emotions in readers. For instance, Yoda’s distinctive speech pattern in “Star Wars” (“Fear leads to anger; anger leads to hate; hate leads to suffering.”) demonstrates how inverted syntax can create a memorable character voice that resonates with wisdom and gravity.

Literary devices like anaphora, which involves the repetition of a word or phrase at the beginning of successive clauses (“It was the best of times, it was the worst of times…”), rely heavily on syntax to build rhythm and evoke emotion. Chiasmus—a reversal in the order of words in two otherwise parallel phrases (“Ask not what your country can do for you—ask what you can do for your country”)—can produce a striking effect that highlights contrasts or balances ideas.

Through such devices, syntax manipulates our reading experience, guiding us toward a deeper understanding of themes and characters. It’s not just what authors say but how they say it that captures our imagination and compels us to reflect on their work long after we’ve turned the last page. Conclusion: The Influence of Syntax in Literary Interpretation

In conclusion, syntax is not merely a set of grammatical rules but a powerful tool that shapes the meaning and tone of literary works. Through deliberate sentence structure, word order, and punctuation, authors can guide readers’ emotions and interpretations. For instance, the use of short, abrupt sentences can create tension or highlight action, while longer, more complex structures may evoke contemplation or establish a narrative voice.

The strategic employment of syntactic devices like anaphora or chiasmus can add rhythm and emphasis to text, influencing how readers perceive themes and characters. Understanding syntax allows readers to appreciate the nuances of literary expression and offers writers the ability to craft their prose with precision.

Recognizing the subtle dance between syntax and meaning enriches our reading experience and deepens our connection to literature. It is an essential aspect of literary analysis that both readers and writers should endeavor to master for a fuller engagement with the written word.

Related Pages:

- Unveiling the Power of Syntax in Literature:…

- Syntax Literary Definition: Unveiling Its Role in Literature

- Mood Literary Definition and Its Role in Storytelling

- Zeugma: Enhancing Language with Clever Connections…

- Mood Definition Literature: Crafting Atmosphere in…

- Exploring Tone in Literature: Enhancing Meaning and…

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Diction refers to word choice and style of expression; Syntax is the arrangement of words and phrases to create well-formed sentences.

Diction is the selection of words and phrases by a writer or speaker . It reflects the style of expression and can greatly influence the tone , mood, and atmosphere of a piece of writing. Diction can be formal, informal, complex, simple, archaic, or jargon-filled, depending on the context and audience.

📖 Example: In “The Great Gatsby,” F. Scott Fitzgerald uses sophisticated and elegant diction to reflect the opulence and decadence of the Jazz Age.

Syntax involves the arrangement of words and phrases to form coherent sentences. It encompasses sentence structure, length, punctuation, and the organization of words. Syntax plays a crucial role in conveying meaning, creating rhythm, and enhancing the readability of text.

📘 Example: In “To Kill a Mockingbird” by Harper Lee, the varied syntax reflects the complexity of themes and characters, using simple sentences to express clear truths and more complex structures for nuanced ideas.

| Literary Device | Definition | Purpose | Usage | Relevant Examples |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| The choice and use of words and phrases in speech or writing. | To convey , mood, and , affecting how the audience perceives the message. | Chosen based on the audience, , and purpose of the writing. | Elegant diction in “The Great Gatsby.” | |

| The arrangement of words and phrases to create well-formed sentences. | To structure information coherently, affecting the pace and flow of the . | Applied in constructing sentences to enhance readability and impact. | Varied in “To Kill a Mockingbird.” |

Writing Tips

When honing your use of diction and syntax :

- For Diction: Be mindful of your audience and purpose. Choose words that accurately convey your intended message and tone . Experiment with specific nouns and vivid verbs to add clarity and depth to your descriptions.

- For Syntax : Play with sentence length and structure to influence the pace and rhythm of your writing. Use short sentences for impact and longer, complex sentences to build suspense or detail.

🖋 Example for Diction: To create a mysterious atmosphere , use precise, evocative words like “whispered,” “shadows,” and “lurking.”

🖋 Example for Syntax : To portray urgency or excitement, employ short, fragmented sentences. For reflective or complex ideas, use longer, compound-complex sentences.

How do diction and syntax work together?

Diction and syntax complement each other; diction provides the building blocks (words), while syntax arranges these blocks into structures (sentences) to effectively convey meaning.

Can changing the syntax alter the meaning of a sentence?

Yes, rearranging words and phrases can significantly change the meaning or emphasis of a sentence, affecting how readers interpret the text.

Is diction more about the meaning of words while syntax is about the order?

Exactly. Diction focuses on the choice of words for their meaning and connotation , whereas syntax is concerned with how those words are organized and structured.

Decide if the following descriptions are more related to diction or syntax :

- The author uses the word “galaxy” instead of “space” to emphasize the vastness and beauty.

- A sentence is structured in passive voice to highlight the action rather than the subject.

- A paragraph starts with short, choppy sentences to mimic the protagonist’s panic.

- The use of slang and colloquial language to make dialogue more realistic.

Interesting Literary Device Comparisons

- Metaphor vs. Simile: Both are comparative devices used to enhance descriptions; metaphors imply direct comparison without using “like” or “as,” whereas similes make comparisons explicit.

- Foreshadowing vs. Flashback: Foreshadowing hints at future events, creating anticipation or suspense, while flashback provides a backward glance at events to add context or depth to the story.

- Alliteration vs. Assonance: Alliteration repeats consonant sounds at the beginning of words close together, while assonance repeats vowel sounds within words, contributing to the musicality and rhythm of the

Poetry Quiz

Students also viewed

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Relating lexical and syntactic knowledge to academic english listening: the importance of construct representation.

- Center for Linguistics and Applied Linguistics, Guangdong University of Foreign Studies, Guangzhou, China

This study aims to resolve contradictory conclusions on the relative importance of lexical and syntactic knowledge in second language (L2) listening with evidence from academic English. It was hypothesized that when lexical and syntactic knowledge is measured in auditory receptive tasks contextualized in natural discourse, the measures will be more relevant to L2 listening, so that both lexical and syntactic knowledge will have unique contributions to L2 listening. To test this hypothesis, a quantitative study was designed, in which lexical and syntactic knowledge was measured via partial dictation, an auditory receptive task contextualized in a discourse context. Academic English listening was measured via a retired IELTS listening test. A group of 258 college-level native Chinese learners of English completed these tasks. Pearson correlations showed that both lexical and syntactic measures correlated strongly with English listening ( r = 0.77 and r = 0.67 respectively). Hierarchical regression analyses showed that both measures jointly explained 62% of the variance in the listening score and that each measure had its unique contribution. These results demonstrated the importance of considering construct representation substantially and using measures that well reflect constructs in practical research.

Introduction

It is not uncommon for researchers to report different or even contradictory findings when they try to address the same issue in second language (L2) studies. A case in point is the relative importance of lexical and syntactic knowledge in L2 listening comprehension, where mixed findings have been reported, some alluding to the sole significance of lexical knowledge while downplaying or masking the role of syntactic knowledge ( Mecartty, 2000 ; Stæhr, 2009 ; Vandergrift and Baker, 2015 ; Cheng and Matthews, 2018 ; Matthews, 2018 ), others rendering the relative importance unclear ( Oh, 2016 ; Wang and Treffers-Daller, 2017 ) or resorting to the more general construct of linguistic knowledge and avoiding the distinction between lexical and syntactic knowledge ( Andringa et al., 2012 ).

The different findings and their relative generalizability may be attributed to various factors, such as the characteristics of the participant groups, the treatments delivered to the participants, the properties of the instruments used, and the settings of the studies. Among these factors, the instruments are of vital importance to the construct validity of the studies ( Shadish et al., 2002 ; Shadish, 2010 ). In the case of lexical and syntactic knowledge, the mixed findings may be attributed, at least partially, to the variety of instruments used in different studies, which are based on different theoretical underpinnings and construct representations. It is, therefore, important to understand the construct definitions and specifications related to the various instruments before the contradictions between findings can be resolved.

Following this reasoning, the relevant studies will be reviewed to compare the various construct representations of lexical and syntactic knowledge under a uniform framework, with a view to identifying the key features that are central to L2 listening. On the basis of these key features, an observational study will be designed in the academic English context to quantify the relative importance of lexical and syntactic knowledge in L2 listening, with a view to resolving the contradictions between findings from earlier studies.

Literature Review

Lexical and syntactic processes in listening.

To establish a uniform framework for comparing the construct representations of lexical and syntactic knowledge, a brief account of psycholinguistic theories of language comprehension is inevitable. Fortunately, descriptions of the key stages of comprehension are more or less the same across the rich variations of models, such that a “basic” model can be conceptualized, comprising word-, sentence-, and discourse-level processes ( Fernández and Cairns, 2018 ). A variation of this basic model often cited in applied linguistics literature is the three-stage cognitive model of Anderson (2015) , consisting of perception , parsing , and utilization . The division into three stages is supported by neurological evidence, such that psychologists are able to identify the different combinations of brain regions involved in the three stages ( Anderson, 2015 ).

In the L2 listening literature, the three stages are sometimes rephrased as decoding , parsing , and meaning construction ( Field, 2011 ). In brief, the listener converts the acoustic-phonetic signal into words, relates the words syntactically for a combined meaning, and enriches the meaning by integrating it with meaning derived from earlier text, context, and background. While the three-stage model deals with the cognitive processes of listening comprehension, these processes depend upon a multitude of sources, linguistic, contextual, and schematic, among which linguistic sources can be further classified into phonetic, phonological, prosodic, lexical, syntactic, semantic, and pragmatic processes ( Lynch, 2010 ).

The interplay between lexical and syntactic processes is an essential part of the cognitive processes in L2 listening. For one thing, word-level processes, such as the identification of a single word, depend on both lexical-semantic and syntactic cues in the context ( Buck, 1991 , 1994 ; Anderson, 2015 ). Neurologically, the speech signal of a word needs to be combined with information about its acoustic-phonological, syntactic, and conceptual semantic properties before it is recognized ( Hagoort, 2013 ). Similarly, parsing also draws on both syntactic and lexical-semantic cues ( Anderson, 2015 ). Underlying this process are two classes of neural mechanisms—lower-order bottom–up mechanisms that enable the lexical-semantic and morphosyntactic categorizations of the speech input and higher-order bottom-up and predictive top–down mechanisms that assign the complex relations between the elements detected in a sentence and integrate them into a conceptual whole ( Skeide and Friederici, 2018 ). There is also evidence that the lexical-semantic and morphosyntactic categorizations are parallel processes, as they occur within 50–80 and 49–90 ms, respectively, after the onset of the speech signal ( Friederici, 2012 ). In general, the three stages of listening comprehension are described as partly parallel and partly overlapping ( Anderson, 2015 ).

Findings in L2 Listening Research

Findings in L2 listening research have mirrored the interplay between lexical and syntactic processes, though to different degrees. For example, some studies on L2 English and French listening focused solely on the correlation between lexical knowledge and L2 listening ( Stæhr, 2009 ; Vandergrift and Baker, 2015 ; Cheng and Matthews, 2018 ; Matthews, 2018 ), reporting significant correlations between 0.39 and 0.73. With regard to the psycholinguistic theories reviewed above, the emphasis on lexical knowledge may have masked the contribution of syntactic knowledge to L2 listening. For the purpose of this study, however, these findings can be regarded as an initial indication of how strong the correlation between lexical knowledge and L2 listening can be.

That being said, the wide range of correlation estimates from these studies points to a potential problem—the inconsistent measures of the same construct. In fact, Cheng and Matthews (2018) deliberately compared the correlations of three different measures of lexical knowledge to L2 English listening and found that the correlations ranged between 0.39 and 0.71. The measure of lexical knowledge may also be confounded with other measures. In the study of Wang and Treffers-Daller (2017) on L2 English listening, the measures included a general language proficiency test, a vocabulary size test, and a questionnaire of metacognitive awareness. However, the general language proficiency test included a large number of items targeting lexical knowledge. Although their results of hierarchical regression analyses showed that general language proficiency and vocabulary both contributed uniquely to the variance of listening, the size of these contributions is subject to this confounding effect.

Another problem arises in empirical studies when the masking of syntactic knowledge in L2 listening is so conspicuous that it may negate the interplay between lexical and syntactic processes. Mecartty’s (2000) study on L2 Spanish learners found that both lexical and syntactic knowledge were significantly correlated with L2 listening ( r = 0.38 and r = 0.26 respectively), but his hierarchical regression analysis showed that only lexical knowledge explained 13% of the variance in listening. Although the addition of syntactic knowledge to the model increased the percentage of explained variance to 14%, the R 2 change was not statistically significant, and Mecartty concluded that syntactic knowledge had no unique contribution, which contradicts the psycholinguistic theories that both syntactic and lexical-semantic cues are necessary for listening comprehension. Interestingly, the correlation between lexical and syntactic measures in Mecartty’s (2000) study was estimated at r = 0.34, which, though significant, could be considered weak. This practically rules out the possibility of substantial overlap between the two measures being the cause of the insignificant R 2 change.

Other studies that were related to the contribution of lexical and syntactic knowledge to L2 listening yielded findings that agreed more with psycholinguistic theories. A common methodological feature among these studies is that L2 listening was regressed on multiple independent variables. Oh’s (2016) study on L2 English listening included four measures of processing speed, two measures of grammar, and three measures of vocabulary. While she found significant correlations between listening and all but one of the processing speed measures, she reported that none of the three groups of measures explained a unique portion of variance in listening when the other two groups of measures were already entered into the hierarchical regression model, which seems to suggest that while lexical and syntactic knowledge both contribute to listening, they were not distinct processes. The assumption of joint contribution of lexical and syntactic knowledge agreed with psycholinguistic theories, but the lack of distinction between the two processes may be considered as construct confounding for the purpose of this study.

Among the studies published so far, Andringa et al. (2012) have captured the psycholinguistic sophistication of L2 listening most faithfully. These authors constructed a structural equation model to explain L2 Dutch listening with a multitude of variables, including three measures of linguistic knowledge, five measures of processing speed, and six cognitive measures of intelligence. They found that the latent construct of linguistic knowledge indicated by vocabulary, grammatical processing, and segmentation (of speech stream into words) explained 90% of the variance in listening. As no distinction was made between lexical and syntactic knowledge in their original model, this result cannot be compared to those discussed above. For this purpose, a hierarchical multiple regression was run by the author of this paper on the R package “lavaan” version 0.6-2 ( Rosseel, 2012 ), using the correlation matrix and standard deviations reported in the original paper in lieu of raw data. The R 2 was estimated at 0.46 when L2 listening was regressed on vocabulary only and at 0.59 on grammar only, but increased to 0.67 when both predictors were entered. This result was closest to psycholinguistic findings in that lexical and syntactic sources both had unique contributions to the variance in L2 listening, and that the joint contribution of the two sources had significantly stronger explanatory power than single sources. Moreover, the lexical and syntactic measures were moderately correlated with each other ( r = 0.60), which ruled out the threat of multicollinearity.

The Importance of Measures

With regard to the relative importance of lexical and syntactic knowledge in L2 listening, the most notable contradiction was between the findings of Andringa et al. (2012) and those reported by Mecartty (2000) . Andringa et al. (2012) themselves noted that linguistic knowledge explained a larger percentage of variance in their study than in Mecartty’s (2000) study. This is an important observation, in that 90% was considerably greater than 14%, which merits much further investigation. A comprehensive search for possible reasons may cover experimental factors or treatments, classificatory factors or personal variables, situational variables or settings, and outcome measures or observations ( Shadish et al., 2002 ), as there are differences between the two studies in all these aspects. A heuristic search, however, could be based on the explanations of the authors themselves, who know the details of their study best. The first possible reason given by Andringa et al. (2012) was that measurement error had been cleared in the latent variable model they used, but even in raw score terms, lexical and syntactic knowledge explained 67% of variance in L2 listening, as this author’s reanalysis demonstrated. Another factor Andringa et al. (2012) postulated was restriction of range in L2 proficiency in Mecartty’s study. This could have attenuated correlations as well, but a closer examination of the coefficients of variation (CVs) yielded comparable results: 0.24 for L2 listening, 0.33 for lexical knowledge, and 0.15 for syntactic knowledge in Andringa et al. (2012) and 0.35 for L2 listening, 0.24 for lexical knowledge, and 0.25 for syntactic knowledge in Mecartty (2000) . Calculated as the ratio of the standard deviation to the mean, the CV is a standardized measure of dispersion such that it can be directly compared between two studies. It follows that the comparable results can be taken as evidence that restriction of range was not a key factor that attenuated correlations in Mecartty’s study. Therefore, the more probable reason that underlies the different findings in the two studies may be that the linguistic knowledge tests in Andringa et al. (2012) were “more pertinent to listening,” whereas “grammatical knowledge was measured in a production task in Mecartty” (p. 70).

A more common term for pertinence is “construct relevance,” and the pertinence issue raised by Andringa et al. (2012) is essentially the issue of construct representation ( Bachman, 1990 ), which takes the form of measures of L2 listening, lexical knowledge, and syntactic knowledge. Underlying the reasoning of Andringa et al. (2012) is the assumption of how lexical and syntactic knowledge should be measured when examining their role in L2 listening. Though the measure of L2 listening itself is also a construct representation issue of no less importance, this paper will be confined to the discussion of the independent variables. A closer examination of the above-mentioned reason reveals two basic conceptual dichotomies familiar to most researchers in applied linguistics, the dichotomy of visual and auditory modes and the dichotomy of receptive and productive skills. Take the syntactic measure used in Andringa et al. (2012) ; the underlying construct was knowledge of the “distributional and combinatorial properties” of the Dutch language, most notably word order and agreement. A judgment task was designed, which required the participants to judge whether a fragment presented aurally was a possible sentence-initial string in Dutch, e.g., Die stad lijkt heel (“That city seems very”) and Precies ik weet (“Exactly I know”). In comparison, Mecartty (2000) used two syntactic measures, the first of which was a sentence completion task aiming to measure “local-level understanding of the grammatical features” of Spanish and requiring the participants to complete Spanish sentences with function words, such as Me gusta aquel automóvil; _____ me gusta el rojo (“I like that car; I ____ like the red one”). The second task was grammaticality judgment and error correction, aiming to measure knowledge of the “underlying rules” of Spanish, which required the participants to identify grammatical errors in Spanish sentences and correct them, such as ∗ Compró el carro y transportó lo a su garaje (“He bought the car and transported it to his garage”). In terms of the two dichotomies, the syntactic measure used in Andringa et al. (2012) was an auditory receptive task, whereas Mecartty’s (2000) syntactic measures were visual productive tasks. As listening is an auditory receptive language use activity, it is natural to expect the former to be more strongly correlated with listening than the latter. More specifically, difficulty in a productive task does not necessarily transfer to a receptive task. For example, an L2 Spanish learner may have difficulty in choosing the right word to complete the sentence Me gusta aquel automóvil; _____ me gusta el rojo , but no difficulty at all in understanding the sentence presented in auditory mode, even if the incomplete sentence is presented. In contrast, identifying Die stad lijkt heel as a sentence-initial string in Dutch is helpful for understanding the meaning of the whole sentence containing the string, as word order is important in Dutch syntax ( Oosterhoff, 2015 ) and thus a key factor for parsing ( Anderson, 2015 ). In sum, a relevant measure of syntactic knowledge in L2 listening should take the form of an auditory receptive task with a focus on the key processes in parsing.

The same features apply to relevant measures of lexical knowledge in L2 listening, as evidenced by the three measures of lexical knowledge in Cheng and Matthews (2018) . Intended for receptive vocabulary, their first measure took a multiple-choice format after the Vocabulary Levels Test of Nation (2001) . Their second measure, targeting productive vocabulary, was adapted from the controlled-production vocabulary levels test of Laufer and Nation (1999) and required the participants to complete a sentence with the target word, whose initial letters were provided. Both measures were presented visually. The third measure of receptive 1 vocabulary took the form of a partial dictation task and required the participants to complete each sentence they heard with a missing word. All three measures covered the first 5,000 frequency levels of word lists extracted from the British National Corpus (BNC, Leech et al., 2001 ). The researchers correlated these measures with the scores from a retired IELTS listening test and estimated Pearson correlation at 0.39 for the visual receptive measure, 0.55 for the visual productive measure, and 0.71 for the auditory receptive measure. This is evidence that auditory receptive measures of lexical knowledge are most relevant to L2 listening, due to similarity in task characteristics between the lexical measure and the L2 listening test. Another dimension that may have contributed to the relevance of lexical measures may be the context provided. The visual productive measure in Cheng and Matthews (2018) was contextualized in single sentences, whereas the visual receptive measure was decontextualized, which may explain why the former was more strongly correlated with L2 listening ( r = 0.55) than the latter ( r = 0.39). A similar pattern is uncovered when comparing the correlation with L2 listening of the sentence-based visual receptive measure in Andringa et al. (2012) and the correlation with L2 listening of the decontextualized visual receptive measure in Mecartty (2000) . Correlation was higher when lexical knowledge was measured in sentential context ( r = 0.68) but lower when the measure was decontextualized ( r = 0.34).

In sum, construct representation is a key factor that affects the findings on the relative importance of lexical and syntactic knowledge in L2 listening. Different measures of lexical and syntactic knowledge may represent different features of the constructs, which affects their relevance to L2 listening. More specifically, the visual/auditory, receptive/productive, and contextualized/decontextualized dichotomies may be key considerations for examining the contribution of lexical and syntactic knowledge to L2 listening.

Research Questions

To examine the above understanding, and to demonstrate the importance of theoretical underpinnings in practical research, the findings of Andringa et al. (2012) and Cheng and Matthews (2018) need to be replicated, with regard to the relationship between lexical and syntactic knowledge and L2 listening. Following the relevance principle, it is hypothesized that when lexical and syntactic knowledge is measured in auditory receptive tasks contextualized in natural discourse, the measures will be more relevant to L2 listening, so that both lexical and syntactic knowledge will have unique contributions to L2 listening. To test this hypothesis, the replication study should include both lexical and syntactic measures, similar to Andringa et al. (2012) , but will be set in the academic English context, similar to Cheng and Matthews (2018) . Two key research questions (RQs) are:

(1) How do lexical and syntactic knowledge correlate with L2 listening in the academic English context?

(2) Do lexical knowledge and syntactic knowledge have unique contributions to L2 listening in the academic English context?

RQ1 aims to measure the degree of association between lexical and syntactic knowledge and L2 listening. It is hypothesized that with a high level of relevance, Pearson correlations around 0.70 may be expected for both measures, similar to the findings with regard to the sentence-based visual receptive measure in Andringa et al. (2012) and the auditory receptive measure in Cheng and Matthews (2018) . RQ2 is based on the psycholinguistic theories reviewed above, assuming that lexical and syntactic processes are distinct but contribute jointly to listening. It is hypothesized that both lexical knowledge and syntactic knowledge have unique contributions to L2 listening, and that the joint contribution of the two sources has stronger explanatory power.

Materials and Methods

Participants.

The study was conducted on 258 native Chinese learners of academic English as a second language. At the time of the study, they were first-year English majors enrolled in a university in China. Their mean raw score on the academic English listening test used in this study (15.33) converted to a band score (5) according to the official conversion table 2 close to the mean band score (5.89) on IELTS listening of test-takers from China in 2018 3 .

Instruments

The measure of L2 academic English listening was a retired IELTS listening test published by Cambridge University Press. No participants had had access to the material prior to this study. The input material included the recordings of two monologs and two conversations, with 40 printed questions in four different formats—multiple-choice questions with four options, matching questions, judgment questions with three options (yes/no/not given or true/false/not given), and fill-in-the-blank questions in the form of questionnaires or forms to be filled. The monologs and conversations were recorded by native English speakers and were set in a variety of everyday social and educational/training contexts. These were designed to measure the ability to understand the main ideas and detailed factual information, the opinions and attitudes of speakers, and the purpose of an utterance and the development of ideas 4 .

The measures of lexical and syntactic knowledge were integrated into a partial dictation task. Eight minutes of recording of the IELTS listening test were selected as the auditory input of the partial dictation, so that the same level of naturalness in spoken English can be achieved ( Cai, 2013 ). The selection was based on the requirement that at least 10 words could be found in the recording on each of the three frequency-based levels, i.e., the 1,001–2,000 frequency range, the 2,001–3,000 frequency range, and the 3,001–5,000 frequency range, of the BNC ( Leech et al., 2001 ). This decision was based on the findings of Matthews (2018) that each of these three levels had unique contributions to L2 listening performance, and on the practice to include 10 items from each 1,000-word-family level for testing vocabulary size ( Nation and Beglar, 2007 ). Each blank was produced by taking away a single word or a two-to-three-word phrase. To give the participant sufficient time to write down the words and phrases they heard, the blanks were set apart at intervals of at least nine words, as the underlined segments (17, 18, and 19) in the following excerpt exemplify.

… I’d like to say at this point that you shouldn’t worry (17) if this process doesn’t work all that quickly – I mean occasionally there are postal problems, but most often the (18) hold-up is caused by references – the people you give as (19) referees , shall we say, take their time to reply.

The interval between blanks No. 18 and No. 19, which both involved single words, was the minimum nine words. The interval between a blank for a missing phrase and another blank was typically longer to allow more time for writing. For example, the interval between blanks No. 17 and No. 18 in the above excerpt was 17 words. This excerpt also exemplifies the items included in the lexical and syntactic scales. The lexical scale was made up of 30 single words, 10 from each of the three levels described above. For example, the words “referees” (blank No. 19) and “hold-up” (blank No. 18) were from the 2,001–3,000 and 3,000–5,000 levels respectively. Each correctly spelled word was worth 1 point, so that the maximum score was 30 for the scale.

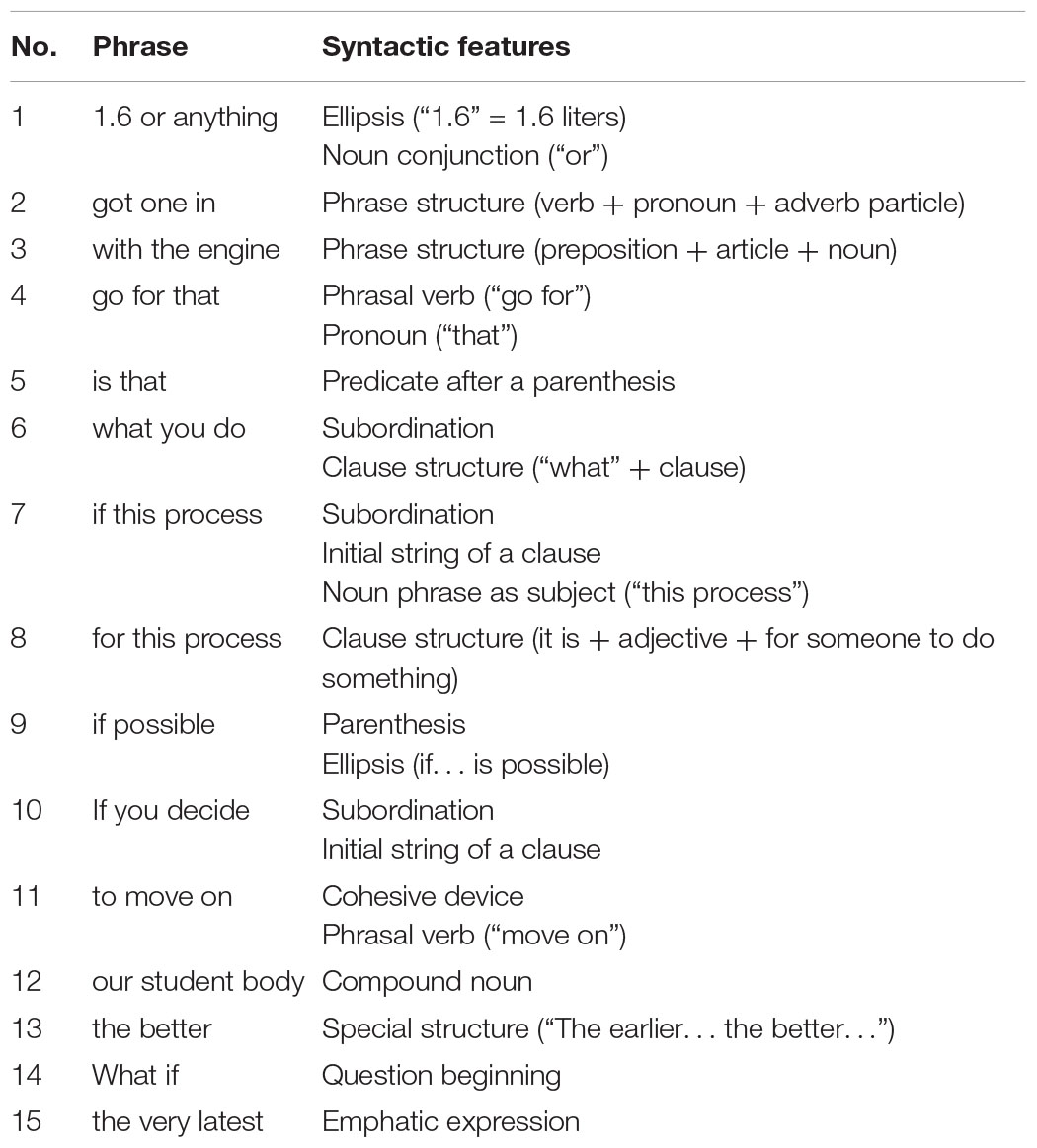

The syntactic scale consisted of 15 two-to-three-word phrases, such as “if this process” for blank No. 17, which is the initial string of a subordinate clause, consisting of the subordinating conjunction “if” and the noun phrase “this process,” which serves as the subject of the clause. Identifying this phrase involves knowledge of word order and subordination, which are both important syntactic cues for parsing ( Anderson, 2015 ). The other syntactic features involved in the items included ellipses, noun conjunctions, pronouns, parentheses, emphatic expressions, etc. (see Appendix for details.) To avoid confounding with lexical processes, none of the phrases in the syntactic scale included words beyond the first 1,000-word-family level of the BNC ( Leech et al., 2001 ). As word order is the key syntactic feature that influences parsing in English ( Anderson, 2015 ), the participants’ responses were scored according to the degree of conformity to the original word order. The maximum score for each segment was 2, for responses that retrieved the original phrase in its full form, for example, “if this process.” A score of 1 was given to responses that retrieved only a semantically proper pairwise sequence, e.g., “this process,” Otherwise the response would be given a score of 0, regardless of the number of words retrieved, e.g., “if process” or “process.” To avoid inconsistent judgments, misspelt words were considered errors. The maximum score for each of the 15 segments was 2 points, and the maximum score for the full scale was 30.

As the lexical and syntactic measures both took the form of a partial dictation task, word recognition may be the key process underlying both measures, which poses a major threat to the validity of the syntactic measure. For preliminary evidence of validity, a homogeneity test by way of internal consistency ( Anastasi and Urbina, 1997 ; Urbina, 2014 ) was conducted. The lexical scale was broken into three subscales, each consisting of 10 items from each of the three levels described above, i.e., the 1,001–2,000 frequency range, the 2,001–3,000 frequency range, and the 3,001–5,000 frequency range, of the BNC ( Leech et al., 2001 ). Coefficient alpha was calculated at 0.85 for the three subscales (which coincided with the item-level estimate reported in Table 1 ) but dropped to 0.78 when the syntactic measure was included as the fourth subscale. As internal consistency is essentially a measure of homogeneity ( Anastasi and Urbina, 1997 ; Urbina, 2014 ), this is evidence that the three lexical subscales constituted a more homogeneous scale, whereas the syntactic measure was more heterogeneous to the lexical measure. Together with the content analysis presented above and detailed in the Appendix , this provides the preliminary evidence for interpreting the 15 phrases as a syntactic measure.

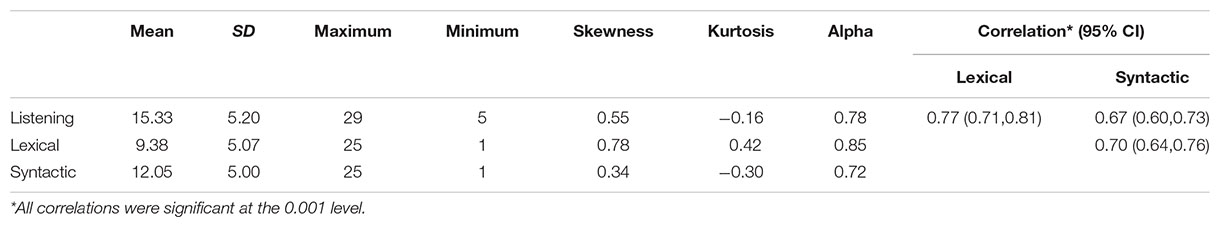

Table 1. Descriptive statistics, reliabilities, and correlations ( n = 258).

Data Collection Procedures

The IELTS listening test was administered in its paper-and-pen form in a computerized language lab as part of a mid-term test for the academic listening course. In accordance with the official IELTS administration procedures, the participants heard the recordings once only and responded to the questions in 30 min, after which they transferred their responses to a commercial web-based testing platform, which saved the responses as a downloadable Microsoft Excel file for scoring.

The partial dictation task was completed immediately after the participants submitted their listening test responses online, as another part of the mid-term test. The task was also administered in its paper-and-pen form. The participants heard the recordings once only, after which the participants submitted their responses to the same testing platform. The responses were also downloaded as a Microsoft Excel file for scoring.

Data Analysis

The scores used in the analyses were numbers of correct responses. The maximum score was 40 for the listening test and 30 for the lexical and syntactic scales. To answer RQ1, scores on the lexical and syntactic scales were correlated to the score on the listening test. To answer RQ2, the listening score was regressed on the lexical and syntactic scales in two sequential analyses. The first analysis started with the lexical scale in the first step, with the addition of the syntactic scale in the second step. The second analysis was conducted in the reverse order, starting with the syntactic scale. All analyses were conducted in SPSS18.

Correlations

Correlations between lexical and syntactic measures and L2 academic English listening were calculated to answer RQ1. Table 1 reports the mean, standard deviation, and internal consistency reliability (coefficient alpha) for each of the three measures, as well as Pearson correlations between each pair of measures with their 95% confidence intervals.

Prior to discussing the descriptive statistics, the internal consistency reliability of the three scores should be examined. Coefficient alpha was estimated at 0.78 for the listening score, 0.85 for the lexical score, and 0.72 for the syntactical score. These were considered acceptable for the study. The coefficient of variation can be calculated for each measure from the mean and standard deviation reported in Table 1 , i.e., 5.20/15.33 = 0.34 for listening, 5.07/9.38 = 0.54 for the lexical score, and 5.00/12.05 = 0.41 for the syntactical score. The CV for the listening score was comparable to the estimates calculated from the descriptive statistics reported in Mecartty (2000) and Andringa et al. (2012) . However, the CVs for the lexical and syntactical scores were considerably greater than those calculated from the two previous studies. Taken together, these were evidence that restriction of range in the three scores did not attenuate the correlations seriously. The skewness and kurtosis estimates of the three scores are also reported in Table 1 . None of these had an absolute value greater than 1, so the scores were considered to be approximately normally distributed, which supported the use of Pearson correlations to represent the bivariate relationships.

As Table 1 shows, the three pairwise correlations were all close to 0.70, comparable to findings reported in Andringa et al. (2012) and Cheng and Matthews (2018) . Considered separately, both lexical and syntactic scores were moderately correlated with the L2 listening score. The correlation between lexical and syntactic scores was also moderate, consistent with psycholinguistic theories that lexical and syntactic processes are distinct processes in listening.

Regression Analyses

To answer RQ2, two hierarchical regression analyses were conducted, both regressing L2 academic English listening on the lexical and syntactic scores, but with different predictors in each step. Prior to the analyses, the outlier and collinearity assumptions were examined. The maximum value of Cook’s distance in the sample was 0.055, far less than the critical value of 1, indicating that there were no overly influential cases that warranted exclusion from the analyses ( Cook, 1977 ). The tolerance was estimated at 0.504, indicating that around half of the variance in one predictor could be explained by the other predictor. The corresponding variance inflation factor was 1.984, and multicollinearity was not considered a serious threat to result interpretation. After the regression analyses, diagnostics were also run to examine the normality and homoscedasticity of the residuals. Figure 1 displays the resulting plots.

Figure 1. Regression diagnostics.

The upper panel is the normal P-P plot of the standardized residuals from the regression model, which displays only minor deviations from normality. The lower panel is the scatterplot with the standardized predicted value on the X-axis and the standardized residuals on the Y-axis. No obvious deviation from homoscedasticity is observed. Therefore, the two regression analyses were considered appropriate.

In the first analysis, the lexical score was entered as a sole predictor of L2 academic English listening in the first step, with the addition of the syntactic score in the second step. The regression with only the lexical score was significant, R 2 = 0.59, adjusted R 2 = 0.59, F (1,256) = 369.76, p < 0.001. The addition of the syntactic score produced a significant R 2 change, R 2 = 0.03, F (1,255) = 22.24, p < 0.001. These results showed that lexical score alone was a good predictor of L2 academic English listening, explaining 59% of the variance in the listening score. The addition of the syntactic score contributed 3% more to the variance in the listening score.

The second analysis reversed the order and started with the syntactic score as a sole predictor of L2 academic English listening, with the addition of the lexical score in the second step. The regression with only the syntactic score was significant, R 2 = 0.45, adjusted R 2 = 0.45, F (1,256) = 208.46, p < 0.001. The addition of the lexical score produced a significant R 2 change, R 2 = 0.18, F (1,255) = 118.53, p < 0.001. These results showed that syntactic score alone was a good predictor of L2 academic English listening, explaining 45% of the variance in the listening score. The addition of the lexical score contributed 18% more to the variance. In either order, both predictors were able to account for 62% of the variance in the listening score.

In answer to RQ2, the above results show that both lexical and syntactic processes had unique contributions to L2 listening in the academic English context.

Comparability to Earlier Studies

The correlation and regression analyses have yielded results that agree more with Andringa et al. (2012) and Cheng and Matthews (2018) than with Mecartty (2000) . When considered separately, both lexical and syntactic measures correlated moderately with L2 academic English listening, with Pearson correlations close to 0.70. When considered jointly, both lexical and syntactic measures had unique contributions to the variance in the listening score. These results have confirmed the hypotheses stated earlier. More generally, they have provided evidence in support of the claim that different degrees of relevance in the measures will yield different results with regard to the relative importance of lexical and syntactic knowledge in L2 listening. More specifically, contextualized auditory receptive measures of lexical and syntactic knowledge are more similar to L2 listening tasks in terms of task characteristics and are considered more relevant to L2 listening in this sense, which explained the different results between Mecartty (2000) and Andringa et al. (2012) . In particular, the lower correlations between lexical and syntactic measures and L2 listening in Mecartty (2000) may be attributed to the decontextualized visual feature of the lexical measure and the visual productive feature of the syntactic measure. The lack of unique contribution of syntactic knowledge to L2 listening in Mecartty (2000) may also be attributed to the same features.

It is also interesting to compare the findings of these studies to similar studies on L2 reading. Studies on the relative significance of lexical and syntactic knowledge in L2 reading have also yielded mixed results—some studies found a greater contribution of lexical knowledge ( Bossers, 1992 ; Brisbois, 1995 ; Yamashita, 1999 ), while others reported heavier regression weights of syntactic knowledge ( Shiotsu and Weir, 2007 ). Shiotsu and Weir (2007) emphasized the difference between a structural equation model and a regression model but also noted that sample size, test difficulty relative to the participants, characteristics of the participants, and the nature and reliabilities of the instruments used are important methodological factors that may explain the differences between studies. The commonality between the findings of the present study and those of Shiotsu and Weir (2007) is that both lexical and syntactic knowledge have a unique contribution to L2 English comprehension.

Importance of Theoretical Underpinnings

The comparison of results between this study and earlier studies also demonstrates the importance of theoretical underpinnings in practical research. For example, the findings that syntactic knowledge does not contribute uniquely to the variance of L2 listening beyond lexical knowledge ( Mecartty, 2000 ) are difficult to explain in light of psycholinguistic theories ( Field, 2011 ; Anderson, 2015 ; Fernández and Cairns, 2018 ; Skeide and Friederici, 2018 ), whereas an emphasis on the joint contribution of lexical and syntactic knowledge ( Andringa et al., 2012 ) agrees in principle with these theories and relative findings. This shows the importance of basing the measures on clear theoretical definitions of the constructs ( Bachman, 1990 ).

The literature review has focused on psycholinguistic theories as the framework for depicting the partly parallel and partly overlapping relation between lexical and syntactic processes ( Anderson, 2015 ). This coincides with findings in applied linguistics. For example, the verbal protocol studies of Buck (1991 , 1994) found that L2 English listening tasks intended to test lexical knowledge turned out to involve higher-order processes, including syntactic processes. In turn, these findings also coincide with the lexico-grammatical approach to language studies in contemporary linguistics, which views lexis and syntax as the two ends of one continuum ( Broccias, 2012 ; Sardinha, 2019 ). However, adopting a psycholinguistic framework offers the convenience of smooth transition to cognitive diagnostic assessment of listening, which is gaining increasing attention in L2 assessment ( Lee and Sawaki, 2009 ; Aryadoust, 2018 ).

Another issue raised in the literature review is construct confounding, which reduces the relevance of results from Oh (2016) and Wang and Treffers-Daller (2017) to the issue under consideration in this study. The relative importance of lexical and syntactic processes in L2 listening was not distinguished in Oh’s (2016) results, while lexical knowledge was intertwined with general language proficiency in Wang and Treffers-Daller (2017) . It is a pity that these studies do not provide further evidence for examining the theoretical relationship between lexical knowledge, syntactic knowledge, and L2 listening.