Absolute Advantage – definition and examples

- Absolute advantage means that an economy can produce a greater total of goods for the same quantity of inputs.

- Absolute advantage means that fewer resources are needed to produce the same amount of goods and there will be lower costs than other economies.

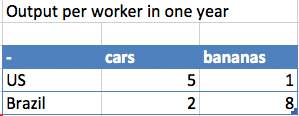

Simple example of absolute advantage

- In this example, Brazil has an absolute advantage in producing bananas (8 to 1).

- The US has an absolute advantage in producing cars (5 to 2)

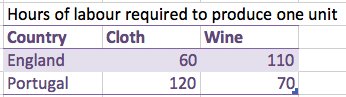

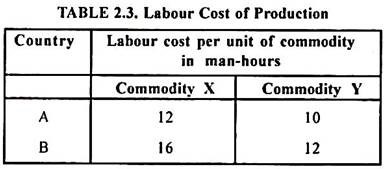

Absolute advantage and labour costs

This is a different way of showing absolute advantage. Rather than show the output, we show the hours of labour required. This reflects the effective cost of production.

- In the above case, England has an absolute advantage in producing cloth (only requires 60 hours compared to Portugal’s 120).

- Portugal has an absolute advantage in producing wine (only requires 70 hours compared to 110 hours in England)

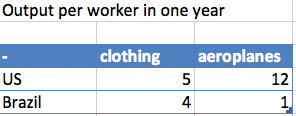

Absolute advantage in everything

It is possible for an economy to have an absolute advantage in everything. Whilst, some countries may have no absolute advantage in any goods or services.

In the above case, the US has an absolute advantage in producing clothing (5 to 4) and also has an absolute advantage in producing aeroplanes. (12 to 1)

Absolute vs Comparative advantage

Absolute advantage is concerned with producing at a lower cost. Comparative advantage is concerned with producing at a lower opportunity cost (ie. relatively better at producing)

Having absolute advantage doesn’t necessarily mean an economy should produce that good. It is not advisable to try and produce everything. It is more helpful to consider comparative advantage .

Comparative advantage measures the opportunity cost of producing a good.

- If the US produces clothing, the opportunity cost is 12/5 = 2.4 aeroplanes foregone.

- If Brazil produces clothing, the opportunity cost is 1/4 = 0.25 aeroplanes foregone.

- Therefore, the US should specialise in producing aeroplanes. Brazil should specialise in producing clothing (even though it doesn’t have an absolute advantage)

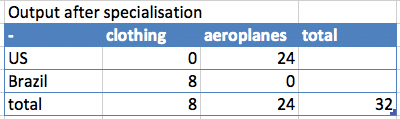

After specialisation

After specialisation, we assume countries are able to concentrate on doubling production because they produce only one good rather than two. Total output and economic welfare increases.

For example, one country may have an absolute advantage in many goods but it is better to focus on on goods where you have a relative advantage.

Absolute advantage in the workplace

- Susan can produce 11 cups of tea per hour and file 13 reports.

- Bob is a lazier worker and can only produce 10 cups of tea per hour and file 3 reports.

In this case, Susan has an absolute advantage in making cups of tea and filing reports.

- However, Susan should not try to do everything. She should specialise in compiling the reports, whilst Bob specialises in making cups of tea.

Notes about absolute advantage

- Absolute advantage can be hard to measure for many complicated goods because there are many different factor inputs.

- Comparative advantage

Published 12 November 2018, Tejvan Pettinger . www.economicshelp.org

13 thoughts on “Absolute Advantage – definition and examples”

Just a minor error, comparative advantage of aeroplanes in Brazil should be 1/4

Line – If Brazil produces clothing, the opportunity cost is 1/5 = 0.25 aeroplanes foregone.

yor comment is totaly wrong b/c comparative advantage is based on lower opportunity cost . countries with lower o.c is better off producing that good. i have degree in economics dear.

I have a degree* not I have degree. I don’t have a degree dear 😁

Sam, you are wrong please on the opportunity cost for Brazil it they decide to produce aeroplanes. The opportunity cost is not 1/4 but rather 4/1 = 4. This because they are forgoing producing 4 clothes only for one aeroplane. The O.C is therefore higher for them if they take this decision.

helpful but would like to know the defference btwn the comparative and absolute in detail

Thanks i got something new for ur presentation

LOL he’s is totally correct. Brazil has the comparative advantage is producing cloth,which the opprtunity cost of Cloth in brazil is lower than US

Thanks a lot… really helpful 🙏🙏🙏🙏🙏🙏

Tanks alot I’ve got everything for my presentation

Thanks a lot the document has really helped

I understood the lesson, I guess my students they are going to compliment me.

I very much enjoyed the notes, please keep publishing more for better clarification and details elaboration of the two subjects ( absolute and comparative advantage). I said this because on the context of relevance of absolute and comparative advantage is not detailed.

Wow I’m so thankful of you what a great lesson I learned from here I really appreciate you thanks for taking some absolutely advantage example.

Leave a comment Cancel reply

Theory of Absolute Advantage

A country has an absolute advantage in the production of that good, which it can produce in greater quantity with the same quantity of resources than another country.

The Theory of Absolute Advantage is one of the earliest economic theories that explains the benefits of specialisation and international trade between countries. It was proposed by Adam Smith, the father of modern economics, in 1776 in his seminal work, "The Wealth of Nations." The theory of absolute advantage is based on the idea that countries can benefit from trade if they specialise in producing goods or services in which they have an absolute advantage over other countries.

The Purpose of the Theory of Absolute Advantage

The purpose of the theory of absolute advantage is to demonstrate the benefits of specialisation and international trade between countries. By specialising in the production of goods and services in which they have an absolute advantage, countries can increase their output through better resource allocation. This, in turn, can lead to economic growth and higher living standards.

Assumptions

The theory of absolute advantage is based on some assumptions, which are given below.

- There are only two countries in the world (Countries A and B).

- Both countries can only produce two goods. (Chairs and tables).

- The same resources are used to produce both goods.

- Both countries have different factor endowment in terms of the quality of their resources.

- Resources are homogeneous within a country. For example, all the workers in a country have the same skills, qualifications, productivity, and motivation.

- The factors of production or inputs (such as labor and capital) are not mobile between countries.

- There is constant opportunity cost. (We assume a straight-line production possibility frontier.)

- There is no transportation cost.

- There is free trade between trading countries. It means that there are no trade barriers for international trade.

- There is barter trade.

Data Example

Let’s use a data example to better understand the concept of absolute advantage.

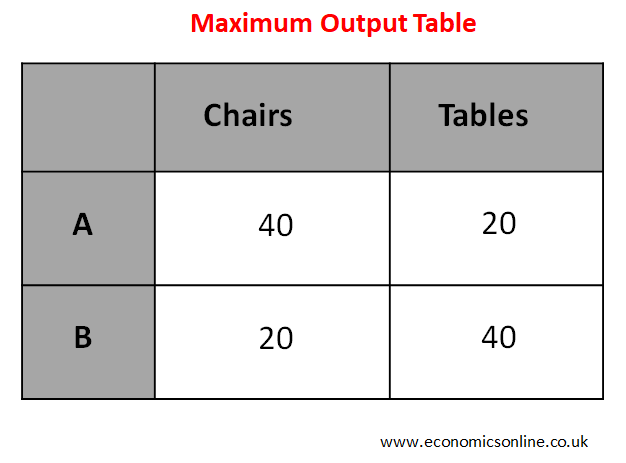

Consider the following maximum output table.

According to the above table, by using all the resources,

Country A can produce 40 chairs or 20 tables and country B can produce 20 chairs or 40 tables.

Suppose that each of the countries A and B has 10 workers. Then, In country A, 10 workers can produce 40 chairs or 20 tables and each worker can produce 4 chairs or 2 tables. While in country B, 10 workers can produce 20 chairs or 40 tables and each worker can produce 2 chairs or 4 tables.

Now let's consider different cases of resource allocation.

Case 1: Self-Sufficiency Output

Suppose that both countries are self-sufficient. Both countries produce chairs and tables according to their own needs. Suppose that both countries use half of their workers for the production of chairs and half for the production of tables. In country A, 5 workers will produce 20 chairs, and 5 workers will produce 10 tables. While in country B, 5 workers will produce 10 chairs, and 5 workers will produce 20 tables.

Following table shows self-sufficiency output in this scenario.

TWO is the total world output produced by both countries. For example, the total world output of chairs is 30 which is the sum of the outputs of country A (20) and country B (10).

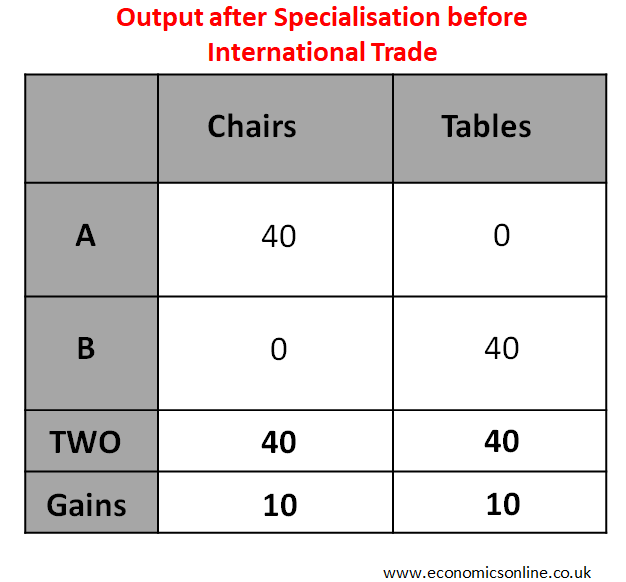

Case 2: Output after Specialisation before International Trade

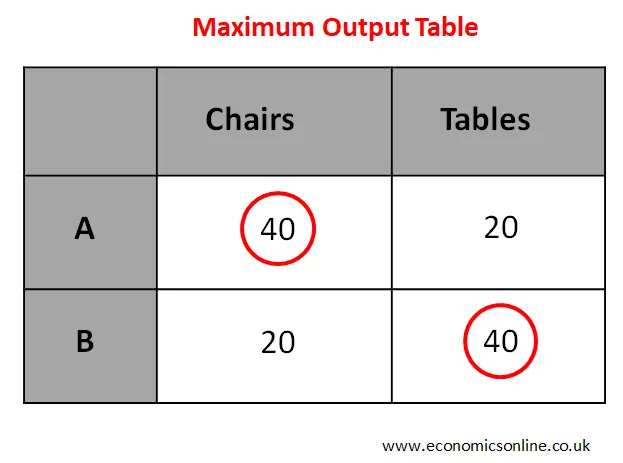

The specialisation decision will be made on the basis of absolute advantage. The specialisation decision will be made by using the maximum output table.

Country A can produce more quantity of chairs; hence, country A has an absolute advantage in the production of chairs.

Country B can produce more quantity of tables; hence, country B has an absolute advantage in the production of tables.

Country A has an absolute advantage in the production of chairs. So, country A should specialise in the production of chairs.

Country B has an absolute advantage in the production of tables. So, country B should specialise in the production of tables.

The following table shows output after specialisation.

It can be noted from above two cases, that the total world output (TWO) is increased due to specialisation. But the problem is that country A does not have tables and country B does not have chairs. This problem can be solved through international trade.

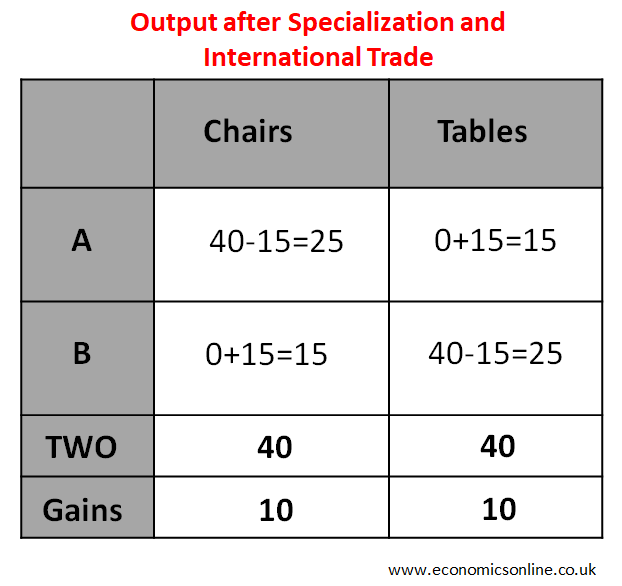

Case 3: Output after Specialisation and International Trade

In order to do international trade, countries have to deciode the barter exchange rate.

The barter exchange rate is the rate at which one country’s goods can be exchanged with another country’s goods. It is also called the barter terms of trade. The following points are important.

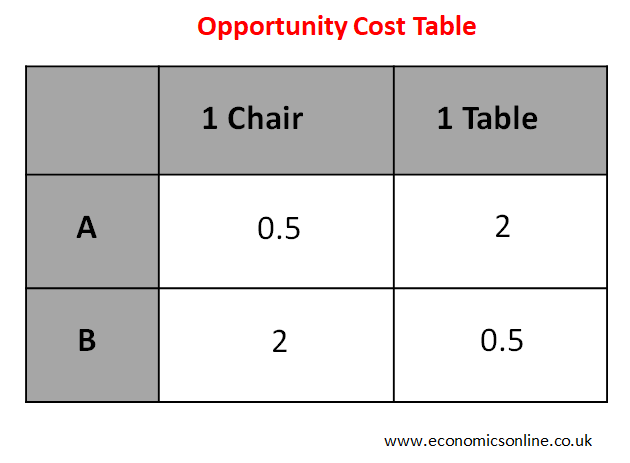

- The opportunity cost table is used to decide the barter exchange rate.

- The barter exchange rate must lie between opportunity cost ratios.

Here is the opportunity cost table.

For country A, the opportunity cost of making 1 chair = 0.5 tables

For country B, the opportunity cost of making 1 chair = 2 tables

Let us take the barter exchange rate as 1 chair = 1 table

Suppose that country A has exported 15 chairs and imported 15 tables

The barter exchange rate is 1 chair = 1 table. So, 15 chairs = 15 tables

For country A, Exports =15 chairs and Imports =15 tables

For country B, Exports =15 tables and Imports =15 chairs

The output after international trade is shown in the table below.

Gains from Specialisation and International Trade

- Country A’s output is increased by 5 chairs and 5 tables.

- Country B’s output is increased by 5 chairs and 5 tables.

- Total world output is increased by 10 chairs and 10 tables.

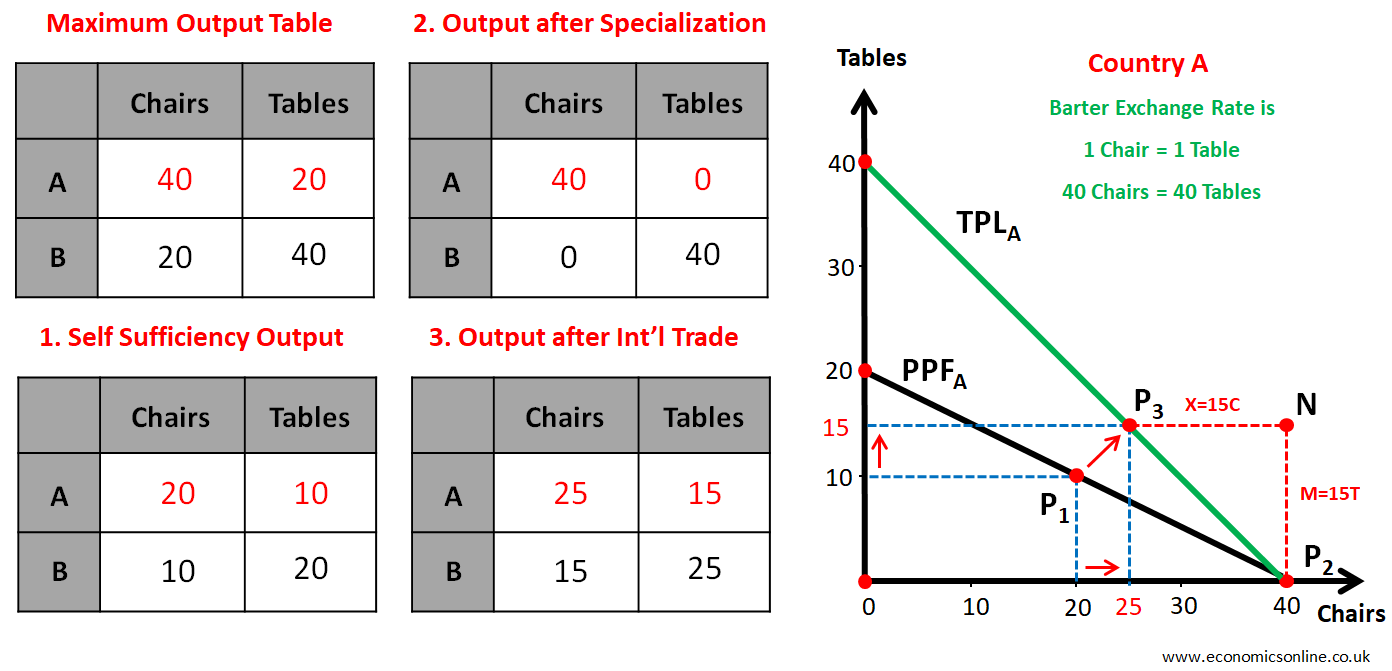

Diagrams of the Theory of Absolute Advantage

Diagram for country a.

The following diagram shows all above cases of resource allocation in country A.

Point P 1 (20, 10) shows self-sufficiency output.

Point P 2 (40, 0) shows output after specialisation before international trade.

Barter exchange rate is 1 chair = 1 table. So, 40 chairs = 40 tables (This is used to draw the trade possibility line, TPL). And 15 chairs = 15 tables.

Point P 3 (25, 15) shows output after international trade.

For Country A , Exports = 15 Chairs Imports = 15 Tables

Country A's Gains from Specialisation and International Trade

- Country A’s output is increased by 5 chairs and 5 tables

- Country A’s output is above PPF, which shows a decrease in scarcity, an increase in output and economic growth.

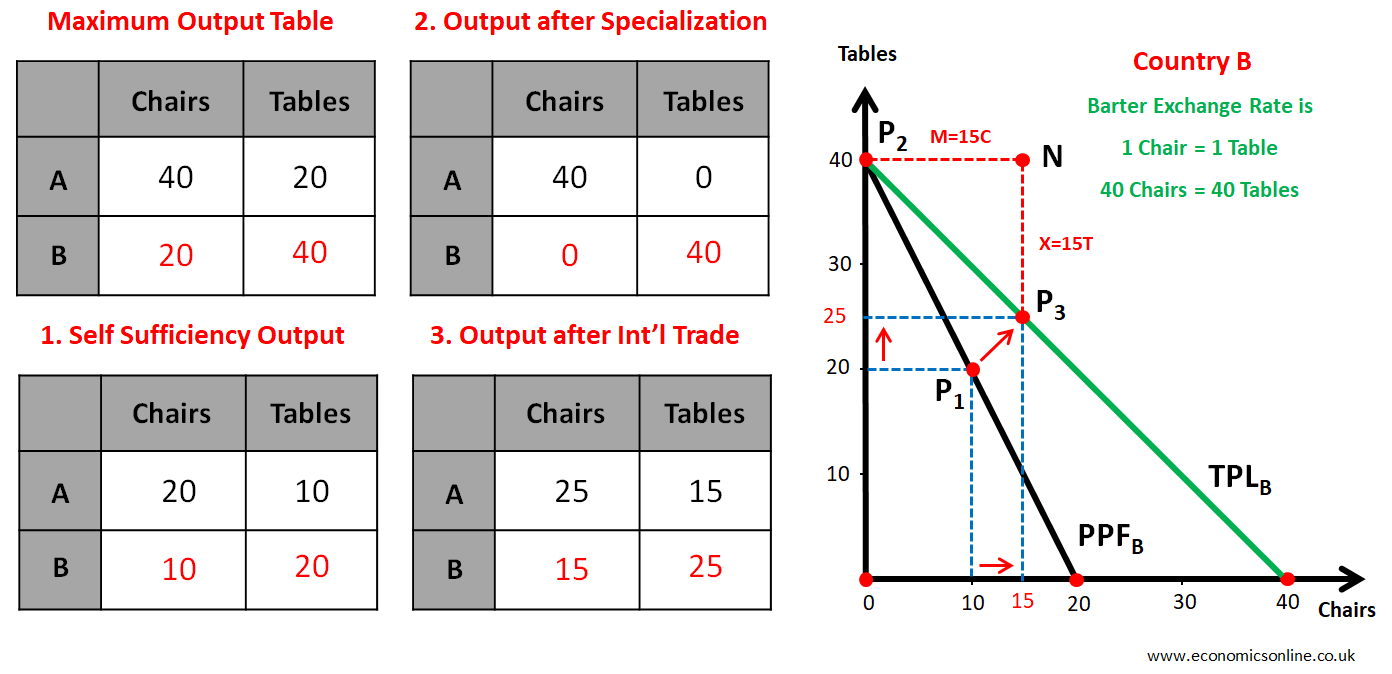

Diagram for Country B

The following diagram shows all above cases of resource allocation in country B.

Point P 1 (10, 20) shows self-sufficiency output.

Point P 2 (0, 40) shows output after specialisation before international trade

Point P 3 (15, 25) shows output after international trade.

For Country B, Imports = 15 Chairs Exports = 15 Tables

Country B's Gains from Specialisation and International Trade

- Country B’s output is above PPF, which shows a decrease in scarcity.

Problem with the Theory of Absolute Advantage

It does not explain the possibility of specialisation and international trade if one country has an absolute advantage in both goods.

Limitations of the Theory of Absolute Advantage

While the theory of absolute advantage provides a useful framework for understanding the benefits of specialisation and international trade, it has several limitations, including:

The theory assumes that there are only two countries and two goods produced, and that all resources are homogeneous within a country, which is an unrealistic oversimplification of the real world.

The theory assumes that all factors of production are fixed and cannot be increased or decreased. In reality, factors of production are not fixed and can be increased or decreased through investment and innovation.

The theory does not account for the impact of government policies, such as subsidies and taxation, on trade.

The theory does not account for the impact of technological change on trade.

The theory assumes free trade without trade restrictions. In reality, there may be tariffs, quotas, and other trade restrictions between countries.

The theory assumes a constant opportunity cost, but in reality, the opportunity cost may not be constant, especially if resources are not homogeneous or if the production process becomes more complex.

The theory assumes barter trade, but in reality, most international trade is conducted through monetary exchange.

The theory assumes no transportation costs, which can have a significant impact on trade patterns.

Real-world Examples of the Theory of Absolute Advantage

Here are some real-world examples of the theory of absolute advantage in action:

Saudi Arabia and Oil Production

Saudi Arabia has an absolute advantage in oil production due to its abundant oil reserves and low cost of production. As a result, it specialises in oil production and exports oil to other countries that do not have an absolute advantage in oil production.

Japan and Electronics Manufacturing

Japan has an absolute advantage in electronics manufacturing due to its highly skilled workforce and advanced technology. As a result, it specialises in electronics manufacturing and exports electronic products to other countries.

China and Textile Production

China has an absolute advantage in textile production due to its low labour costs and large workforce. As a result, it specialises in textile production and exports textiles to other countries.

New Zealand and Agriculture

New Zealand has an absolute advantage in agriculture due to its favourable climate and abundant natural resources. As a result, it specialises in agriculture and exports agricultural products to other countries.

Zambia and Copper Production

Zambia has an absolute advantage in copper production due to its abundant copper reserves and low cost of production. As a result, it specialises in copper production and exports copper to other countries. In fact, copper is Zambia's main export, accounting for over 70% of the country's total export earnings.

These examples illustrate how countries can benefit from specialising in the production of goods in which they have an absolute advantage, and then trading with other countries to obtain goods in which they do not have an absolute advantage.

Theory of Absolute Advantage vs. Theory of Comparative Advantage

The theory of comparative advantage, developed by David Ricardo in the early 18th century, is another important economic theory that explains the benefits of international trade. The key differences between the theory of absolute advantage and the theory of comparative advantage are that the idea of absolute advantage focuses on productivity and efficiency, while the theory of comparative advantage focuses on opportunity costs. The theory of comparative advantage suggests that countries should specialise in producing goods and services for which they have a lower opportunity cost of production than other countries. This means that a country should produce the goods and services in which it is relatively more efficient, even if it is not absolutely efficient in producing them. Despite these differences, both Smith's theory of absolute advantage and Ricardo's theory of comparative advantage justify the benefits of specialisation and international trade.

In conclusion, the theory of absolute advantage provides a useful framework for understanding the benefits of international trade between countries. By specialising in the production of goods and services in which they have an absolute advantage, countries can increase their productivity and efficiency and reduce their production costs. However, the theory has several limitations and assumptions that must be considered, and it should be compared with other economic theories, such as the theory of comparative advantage, for a more complete understanding of the benefits of international trade.

Illusory Correlation

Understanding the Tragedy of the Commons with Examples

33.1 Absolute and Comparative Advantage

Learning objectives.

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Define absolute advantage, comparative advantage, and opportunity costs

- Explain the gains of trade created when a country specializes

The American statesman Benjamin Franklin (1706–1790) once wrote: “No nation was ever ruined by trade.” Many economists would express their attitudes toward international trade in an even more positive manner. The evidence that international trade confers overall benefits on economies is pretty strong. Trade has accompanied economic growth in the United States and around the world. Many of the national economies that have shown the most rapid growth in the last several decades—for example, Japan, South Korea, China, and India—have done so by dramatically orienting their economies toward international trade. There is no modern example of a country that has shut itself off from world trade and yet prospered. To understand the benefits of trade, or why we trade in the first place, we need to understand the concepts of comparative and absolute advantage.

In 1817, David Ricardo , a businessman, economist, and member of the British Parliament, wrote a treatise called On the Principles of Political Economy and Taxation . In this treatise, Ricardo argued that specialization and free trade benefit all trading partners, even those that may be relatively inefficient. To see what he meant, we must be able to distinguish between absolute and comparative advantage.

A country has an absolute advantage over another country in producing a good if it can produce more of that good. Absolute advantage can be the result of a country’s having more resources, having more productive resources, or its natural endowment. For example, extracting oil in Saudi Arabia is pretty much just a matter of “drilling a hole.” Producing oil in other countries can require considerable exploration and costly technologies for drilling and extraction—if they have any oil at all. The United States has some of the richest farmland in the world, making it easier to grow corn and wheat than in many other countries. Guatemala and Colombia have climates especially suited for growing coffee. Chile and Zambia have some of the world’s richest copper mines. As some have argued, “geography is destiny.” Chile will provide copper and Guatemala will produce coffee, and they will trade. When each country has a product others need and it can produce it with fewer resources in one country than in another, then it is easy to imagine all parties benefitting from trade. However, thinking about trade just in terms of geography and absolute advantage is incomplete. Trade really occurs because of comparative advantage.

Recall from the chapter Choice in a World of Scarcity that a country has a comparative advantage when it can produce a good at a lower cost in terms of other goods. The question each country or company should be asking when it trades is this: “What do we give up to produce this good?” It should be no surprise that the concept of comparative advantage is based on this idea of opportunity cost from Choice in a World of Scarcity . For example, if Zambia focuses its resources on producing copper, it cannot use its labor, land and financial resources to produce other goods such as corn. As a result, Zambia gives up the opportunity to produce corn. How do we quantify the cost in terms of other goods? Simplify the problem and assume that Zambia just needs labor to produce copper and corn. The companies that produce either copper or corn tell you that it takes two hours to mine a ton of copper and one hour to harvest a bushel of corn. This means the opportunity cost of producing a ton of copper is two bushels of corn. The next section develops absolute and comparative advantage in greater detail and relates them to trade.

Visit this website for a list of articles and podcasts pertaining to international trade topics.

A Numerical Example of Absolute and Comparative Advantage

Consider a hypothetical world with two countries, Saudi Arabia and the United States, and two products, oil and corn. Further assume that consumers in both countries desire both these goods. These goods are homogeneous, meaning that consumers/producers cannot differentiate between corn or oil from either country. There is only one resource available in both countries, labor hours. Saudi Arabia can produce oil with fewer resources, while the United States can produce corn with fewer resources. Table 33.1 illustrates the advantages of the two countries, expressed in terms of how many hours it takes to produce one unit of each good.

In Table 33.1 , Saudi Arabia has an absolute advantage in producing oil because it only takes an hour to produce a barrel of oil compared to two hours in the United States. The United States has an absolute advantage in producing corn.

To simplify, let’s say that Saudi Arabia and the United States each have 100 worker hours (see Table 33.2 ). Figure 33.2 illustrates what each country is capable of producing on its own using a production possibility frontier (PPF) graph. Recall from Choice in a World of Scarcity that the production possibilities frontier shows the maximum amount that each country can produce given its limited resources, in this case workers, and its level of technology.

Arguably Saudi and U.S. consumers desire both oil and corn to live. Let’s say that before trade occurs, both countries produce and consume at point C or C'. Thus, before trade, the Saudi Arabian economy will devote 60 worker hours to produce oil, as Table 33.3 shows. Given the information in Table 33.1 , this choice implies that it produces/consumes 60 barrels of oil. With the remaining 40 worker hours, since it needs four hours to produce a bushel of corn, it can produce only 10 bushels. To be at point C', the U.S. economy devotes 40 worker hours to produce 20 barrels of oil and it can allocate the remaining worker hours to produce 60 bushels of corn.

The slope of the production possibility frontier illustrates the opportunity cost of producing oil in terms of corn. Using all its resources, the United States can produce 50 barrels of oil or 100 bushels of corn; therefore, the opportunity cost of one barrel of oil is two bushels of corn—or the slope is 1/2. Thus, in the U.S. production possibility frontier graph, every increase in oil production of one barrel implies a decrease of two bushels of corn. Saudi Arabia can produce 100 barrels of oil or 25 bushels of corn. The opportunity cost of producing one barrel of oil is the loss of 1/4 of a bushel of corn that Saudi workers could otherwise have produced. In terms of corn, notice that Saudi Arabia gives up the least to produce a barrel of oil. Table 33.4 summarizes these calculations.

Again recall that we defined comparative advantage as the opportunity cost of producing goods. Since Saudi Arabia gives up the least to produce a barrel of oil, ( 1 4 1 4 < 2 2 in Table 33.4 ) it has a comparative advantage in oil production. The United States gives up the least to produce a bushel of corn, so it has a comparative advantage in corn production.

In this example, there is symmetry between absolute and comparative advantage. Saudi Arabia needs fewer worker hours to produce oil (absolute advantage, see Table 33.1 ), and also gives up the least in terms of other goods to produce oil (comparative advantage, see Table 33.4 ). Such symmetry is not always the case, as we will show after we have discussed gains from trade fully, but first, read the following Clear It Up feature to make sure you understand why the PPF line in the graphs is straight.

Clear It Up

Can a production possibility frontier be straight.

When you first met the production possibility frontier (PPF) in the chapter on Choice in a World of Scarcity we drew it with an outward-bending shape. This shape illustrated that as we transferred inputs from producing one good to another—like from education to health services—there were increasing opportunity costs. In the examples in this chapter, we draw the PPFs as straight lines, which means that opportunity costs are constant. When we transfer a marginal unit of labor away from growing corn and toward producing oil, the decline in the quantity of corn and the increase in the quantity of oil is always the same. In reality this is possible only if the contribution of additional workers to output did not change as the scale of production changed. The linear production possibilities frontier is a less realistic model, but a straight line simplifies calculations. It also illustrates economic themes like absolute and comparative advantage just as clearly.

Gains from Trade

Consider the trading positions of the United States and Saudi Arabia after they have specialized and traded. Before trade, Saudi Arabia produces/consumes 60 barrels of oil and 10 bushels of corn. The United States produces/consumes 20 barrels of oil and 60 bushels of corn. Given their current production levels, if the United States can trade an amount of corn fewer than 60 bushels and receive in exchange an amount of oil greater than 20 barrels, it will gain from trade . With trade, the United States can consume more of both goods than it did without specialization and trade. (Recall that the chapter Welcome to Economics! defined specialization as it applies to workers and firms. Economists also use specialization to describe the occurrence when a country shifts resources to focus on producing a good that offers comparative advantage.) Similarly, if Saudi Arabia can trade an amount of oil less than 60 barrels and receive in exchange an amount of corn greater than 10 bushels, it will have more of both goods than it did before specialization and trade. Table 33.5 illustrates the range of trades that would benefit both sides.

The underlying reason why trade benefits both sides is rooted in the concept of opportunity cost, as the following Clear It Up feature explains. If Saudi Arabia wishes to expand domestic production of corn in a world without international trade, then based on its opportunity costs it must give up four barrels of oil for every one additional bushel of corn. If Saudi Arabia could find a way to give up less than four barrels of oil for an additional bushel of corn (or equivalently, to receive more than one bushel of corn for four barrels of oil), it would be better off.

What are the opportunity costs and gains from trade?

The range of trades that will benefit each country is based on the country’s opportunity cost of producing each good. The United States can produce 100 bushels of corn or 50 barrels of oil. For the United States, the opportunity cost of producing one barrel of oil is two bushels of corn. If we divide the numbers above by 50, we get the same ratio: one barrel of oil is equivalent to two bushels of corn, or (100/50 = 2 and 50/50 = 1). In a trade with Saudi Arabia, if the United States is going to give up 100 bushels of corn in exports, it must import at least 50 barrels of oil to be just as well off. Clearly, to gain from trade it needs to be able to gain more than a half barrel of oil for its bushel of corn—or why trade at all?

Recall that David Ricardo argued that if each country specializes in its comparative advantage, it will benefit from trade, and total global output will increase. How can we show gains from trade as a result of comparative advantage and specialization? Table 33.6 shows the output assuming that each country specializes in its comparative advantage and produces no other good. This is 100% specialization. Specialization leads to an increase in total world production. (Compare the total world production in Table 33.3 to that in Table 33.6 .)

What if we did not have complete specialization, as in Table 33.6 ? Would there still be gains from trade? Consider another example, such as when the United States and Saudi Arabia start at C and C', respectively, as Figure 33.2 shows. Consider what occurs when trade is allowed and the United States exports 20 bushels of corn to Saudi Arabia in exchange for 20 barrels of oil.

Starting at point C, which shows Saudi oil production of 60, reduce Saudi oil domestic oil consumption by 20, since 20 is exported to the United States and exchanged for 20 units of corn. This enables Saudi to reach point D, where oil consumption is now 40 barrels and corn consumption has increased to 30 (see Figure 33.3 ). Notice that even without 100% specialization, if the “trading price,” in this case 20 barrels of oil for 20 bushels of corn, is greater than the country’s opportunity cost, the Saudis will gain from trade. Since the post-trade consumption point D is beyond its production possibility frontier, Saudi Arabia has gained from trade.

Visit this website for trade-related data visualizations.

As an Amazon Associate we earn from qualifying purchases.

This book may not be used in the training of large language models or otherwise be ingested into large language models or generative AI offerings without OpenStax's permission.

Want to cite, share, or modify this book? This book uses the Creative Commons Attribution License and you must attribute OpenStax.

Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/principles-economics-3e/pages/1-introduction

- Authors: Steven A. Greenlaw, David Shapiro, Daniel MacDonald

- Publisher/website: OpenStax

- Book title: Principles of Economics 3e

- Publication date: Dec 14, 2022

- Location: Houston, Texas

- Book URL: https://openstax.org/books/principles-economics-3e/pages/1-introduction

- Section URL: https://openstax.org/books/principles-economics-3e/pages/33-1-absolute-and-comparative-advantage

© Jan 23, 2024 OpenStax. Textbook content produced by OpenStax is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License . The OpenStax name, OpenStax logo, OpenStax book covers, OpenStax CNX name, and OpenStax CNX logo are not subject to the Creative Commons license and may not be reproduced without the prior and express written consent of Rice University.

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

20.2: Absolute and Comparative Advantage

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 164369

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Define absolute advantage, comparative advantage, and opportunity costs

- Explain the gains of trade created when a country specializes

The American statesman Benjamin Franklin (1706–1790) once wrote: “No nation was ever ruined by trade.” Many economists would express their attitudes toward international trade in an even more positive manner. The evidence that international trade confers overall benefits on economies is pretty strong. Trade has accompanied economic growth in the United States and around the world. Many of the national economies that have shown the most rapid growth in the last several decades—for example, Japan, South Korea, China, and India—have done so by dramatically orienting their economies toward international trade. There is no modern example of a country that has shut itself off from world trade and yet prospered. To understand the benefits of trade, or why we trade in the first place, we need to understand the concepts of comparative and absolute advantage.

In 1817, David Ricardo , a businessman, economist, and member of the British Parliament, wrote a treatise called On the Principles of Political Economy and Taxation . In this treatise, Ricardo argued that specialization and free trade benefit all trading partners, even those that may be relatively inefficient. To see what he meant, we must be able to distinguish between absolute and comparative advantage.

A country has an absolute advantage over another country in producing a good if it uses fewer resources to produce that good. Absolute advantage can be the result of a country’s natural endowment. For example, extracting oil in Saudi Arabia is pretty much just a matter of “drilling a hole.” Producing oil in other countries can require considerable exploration and costly technologies for drilling and extraction—if they have any oil at all. The United States has some of the richest farmland in the world, making it easier to grow corn and wheat than in many other countries. Guatemala and Colombia have climates especially suited for growing coffee. Chile and Zambia have some of the world’s richest copper mines. As some have argued, “geography is destiny.” Chile will provide copper and Guatemala will produce coffee, and they will trade. When each country has a product others need and it can produce it with fewer resources in one country than in another, then it is easy to imagine all parties benefitting from trade. However, thinking about trade just in terms of geography and absolute advantage is incomplete. Trade really occurs because of comparative advantage.

Recall from the chapter Choice in a World of Scarcity that a country has a comparative advantage when it can produce a good at a lower cost in terms of other goods. The question each country or company should be asking when it trades is this: “What do we give up to produce this good?” It should be no surprise that the concept of comparative advantage is based on this idea of opportunity cost from Choice in a World of Scarcity. For example, if Zambia focuses its resources on producing copper, it cannot use its labor, land and financial resources to produce other goods such as corn. As a result, Zambia gives up the opportunity to produce corn. How do we quantify the cost in terms of other goods? Simplify the problem and assume that Zambia just needs labor to produce copper and corn. The companies that produce either copper or corn tell you that it takes two hours to mine a ton of copper and one hour to harvest a bushel of corn. This means the opportunity cost of producing a ton of copper is two bushels of corn. The next section develops absolute and comparative advantage in greater detail and relates them to trade.

Visit this website for a list of articles and podcasts pertaining to international trade topics.

A Numerical Example of Absolute and Comparative Advantage

Consider a hypothetical world with two countries, Saudi Arabia and the United States, and two products, oil and corn. Further assume that consumers in both countries desire both these goods. These goods are homogeneous, meaning that consumers/producers cannot differentiate between corn or oil from either country. There is only one resource available in both countries, labor hours. Saudi Arabia can produce oil with fewer resources, while the United States can produce corn with fewer resources. Table 20.1 illustrates the advantages of the two countries, expressed in terms of how many hours it takes to produce one unit of each good.

In Table 20.1, Saudi Arabia has an absolute advantage in producing oil because it only takes an hour to produce a barrel of oil compared to two hours in the United States. The United States has an absolute advantage in producing corn.

To simplify, let’s say that Saudi Arabia and the United States each have 100 worker hours (see Table 20.2). Figure 20.2 illustrates what each country is capable of producing on its own using a production possibility frontier (PPF) graph. Recall from Choice in a World of Scarcity that the production possibilities frontier shows the maximum amount that each country can produce given its limited resources, in this case workers, and its level of technology.

Arguably Saudi and U.S. consumers desire both oil and corn to live. Let’s say that before trade occurs, both countries produce and consume at point C or C'. Thus, before trade, the Saudi Arabian economy will devote 60 worker hours to produce oil, as Table 20.3 shows. Given the information in Table 20.1, this choice implies that it produces/consumes 60 barrels of oil. With the remaining 40 worker hours, since it needs four hours to produce a bushel of corn, it can produce only 10 bushels. To be at point C', the U.S. economy devotes 40 worker hours to produce 20 barrels of oil and it can allocate the remaining worker hours to produce 60 bushels of corn.

The slope of the production possibility frontier illustrates the opportunity cost of producing oil in terms of corn. Using all its resources, the United States can produce 50 barrels of oil or 100 bushels of corn; therefore, the opportunity cost of one barrel of oil is two bushels of corn—or the slope is 1/2. Thus, in the U.S. production possibility frontier graph, every increase in oil production of one barrel implies a decrease of two bushels of corn. Saudi Arabia can produce 100 barrels of oil or 25 bushels of corn. The opportunity cost of producing one barrel of oil is the loss of 1/4 of a bushel of corn that Saudi workers could otherwise have produced. In terms of corn, notice that Saudi Arabia gives up the least to produce a barrel of oil. Table 20.4 summarizes these calculations.

Again recall that we defined comparative advantage as the opportunity cost of producing goods. Since Saudi Arabia gives up the least to produce a barrel of oil, ( 1 4 1 4 < 2 2 in Table 20.4) it has a comparative advantage in oil production. The United States gives up the least to produce a bushel of corn, so it has a comparative advantage in corn production.

In this example, there is symmetry between absolute and comparative advantage. Saudi Arabia needs fewer worker hours to produce oil (absolute advantage, see Table 20.1), and also gives up the least in terms of other goods to produce oil (comparative advantage, see Table 20.4). Such symmetry is not always the case, as we will show after we have discussed gains from trade fully, but first, read the following Clear It Up feature to make sure you understand why the PPF line in the graphs is straight.

Clear It Up

Can a production possibility frontier be straight.

When you first met the production possibility frontier (PPF) in the chapter on Choice in a World of Scarcity we drew it with an outward-bending shape. This shape illustrated that as we transferred inputs from producing one good to another—like from education to health services—there were increasing opportunity costs. In the examples in this chapter, we draw the PPFs as straight lines, which means that opportunity costs are constant. When we transfer a marginal unit of labor away from growing corn and toward producing oil, the decline in the quantity of corn and the increase in the quantity of oil is always the same. In reality this is possible only if the contribution of additional workers to output did not change as the scale of production changed. The linear production possibilities frontier is a less realistic model, but a straight line simplifies calculations. It also illustrates economic themes like absolute and comparative advantage just as clearly.

Gains from Trade

Consider the trading positions of the United States and Saudi Arabia after they have specialized and traded. Before trade, Saudi Arabia produces/consumes 60 barrels of oil and 10 bushels of corn. The United States produces/consumes 20 barrels of oil and 60 bushels of corn. Given their current production levels, if the United States can trade an amount of corn fewer than 60 bushels and receive in exchange an amount of oil greater than 20 barrels, it will gain from trade . With trade, the United States can consume more of both goods than it did without specialization and trade. (Recall that the chapter Welcome to Economics! defined specialization as it applies to workers and firms. Economists also use specialization to describe the occurrence when a country shifts resources to focus on producing a good that offers comparative advantage.) Similarly, if Saudi Arabia can trade an amount of oil less than 60 barrels and receive in exchange an amount of corn greater than 10 bushels, it will have more of both goods than it did before specialization and trade. Table 20.5 illustrates the range of trades that would benefit both sides.

The underlying reason why trade benefits both sides is rooted in the concept of opportunity cost, as the following Clear It Up feature explains. If Saudi Arabia wishes to expand domestic production of corn in a world without international trade, then based on its opportunity costs it must give up four barrels of oil for every one additional bushel of corn. If Saudi Arabia could find a way to give up less than four barrels of oil for an additional bushel of corn (or equivalently, to receive more than one bushel of corn for four barrels of oil), it would be better off.

What are the opportunity costs and gains from trade?

The range of trades that will benefit each country is based on the country’s opportunity cost of producing each good. The United States can produce 100 bushels of corn or 50 barrels of oil. For the United States, the opportunity cost of producing one barrel of oil is two bushels of corn. If we divide the numbers above by 50, we get the same ratio: one barrel of oil is equivalent to two bushels of corn, or (100/50 = 2 and 50/50 = 1). In a trade with Saudi Arabia, if the United States is going to give up 100 bushels of corn in exports, it must import at least 50 barrels of oil to be just as well off. Clearly, to gain from trade it needs to be able to gain more than a half barrel of oil for its bushel of corn—or why trade at all?

Recall that David Ricardo argued that if each country specializes in its comparative advantage, it will benefit from trade, and total global output will increase. How can we show gains from trade as a result of comparative advantage and specialization? Table 20.6 shows the output assuming that each country specializes in its comparative advantage and produces no other good. This is 100% specialization. Specialization leads to an increase in total world production. (Compare the total world production in Table 20.3 to that in Table 20.6.)

What if we did not have complete specialization, as in Table 20.6? Would there still be gains from trade? Consider another example, such as when the United States and Saudi Arabia start at C and C', respectively, as Figure 20.2 shows. Consider what occurs when trade is allowed and the United States exports 20 bushels of corn to Saudi Arabia in exchange for 20 barrels of oil.

Starting at point C, which shows Saudi oil production of 60, reduce Saudi oil domestic oil consumption by 20, since 20 is exported to the United States and exchanged for 20 units of corn. This enables Saudi to reach point D, where oil consumption is now 40 barrels and corn consumption has increased to 30 (see Figure 20.3). Notice that even without 100% specialization, if the “trading price,” in this case 20 barrels of oil for 20 bushels of corn, is greater than the country’s opportunity cost, the Saudis will gain from trade. Since the post-trade consumption point D is beyond its production possibility frontier, Saudi Arabia has gained from trade.

Visit this website for trade-related data visualizations.

Key Terms for All Subjects

50k vocabulary words to help you ace your ap, sat & act exams.

AP Art & Design

AP Art History

AP Music Theory

AP Capstone

AP Research

AP English Language

AP English Literature

AP European History

AP US History

AP World History: Modern

AP Chemistry

AP Environmental Science

AP Physics 1

AP Physics 2

AP Physics C: E&M

AP Physics C: Mechanics

AP Math & Computer Science

AP Calculus AB/BC

AP Computer Science A

AP Computer Science Principles

AP Pre-Calculus

AP Statistics

AP Social Science

AP Comparative Government

AP Human Geography

AP Macroeconomics

AP Microeconomics

AP Psychology

AP US Government

AP World Languages & Cultures

AP Japanese

AP Spanish Language

AP Spanish Literature

Stay Connected

© 2024 Fiveable Inc. All rights reserved.

AP® and SAT® are trademarks registered by the College Board, which is not affiliated with, and does not endorse this website.

Absolute Advantage

According to Adam Smith, who is regarded as the father of modern economics, countries should only produce goods in which they have an absolute advantage. An individual, business, or country is said to have an absolute advantage if it can produce a good at a lower cost than another individual, business, or country.

Furthermore, when a producer has an absolute advantage, it also means that fewer resources and less time are needed to provide the same amount of goods as compared to the other producer. This greater overall efficiency in production creates an absolute advantage, which allows for beneficial trade—this is because producers are able to specialize and then, through trade, benefit from other producers’ specialization.

Assumptions Underlying the Theory of Absolute Advantage

The idea of absolute advantage rests on a number of assumptions on the part of Adam Smith. While influential and insightful, the theory of absolute advantage is not always entirely accurate because many of these fundamental assumptions are in fact not true in practice. Here are the most significant of these assumptions:

1. Lack of Mobility for Factors of Production

Adam Smith assumes that factors of production cannot move between countries. This assumption also implies that the Production Possibility Frontier of each country will not change after the trade.

2. Trade Barriers

There are no barriers to trade for the exchange of goods. Governments implement trade barriers to restrict or discourage the importation or exportation of a particular good.

3. Trade Balance

Smith assumes that exports must be equal to imports. This assumption means that we cannot have trade imbalances, trade deficits, or surpluses. A trade imbalance occurs when exports are higher than imports or vice versa.

4. Constant Returns to Scale

Adam Smith assumes that we will get constant returns as production scales, meaning there are no economies of scale . For example, if it takes 2 hours to make one loaf of bread in country A, then it should take 4 hours to produce two loaves of bread. Consequently, it would take 8 hours to produce four loaves of bread.

However, if there were economies of scale, then it would become cheaper for countries to keep producing the same good as it produced more of the same good.

Absolute Advantage vs. Comparative Advantage

Both absolute advantage and comparative advantage are enormously significant concepts for understanding how international trade works. Both nations and the firms residing within them make many of their decisions about resource allocation (which goods should be allotted more or fewer resources for production ) based on assessments of absolute and comparative advantage.

The two concepts are undoubtedly related but are also distinct. Absolute advantage refers to situations wherein one firm or nation can produce a given product of better quality, more quickly, and for higher profits than can another firm or nation. Comparative advantage, by contrast, looks at international trade more broadly—it accounts for the opportunity costs of choosing to manufacture multiple kinds of products using finite resources.

Adam Smith had believed that absolute advantage was a necessity for beneficial trade. The theory of comparative advantage was developed by David Ricardo, who built on Adam Smith’s work to argue that, in fact, a country doesn’t have to have an absolute advantage for beneficial trade to occur.

Absolute Advantage Example

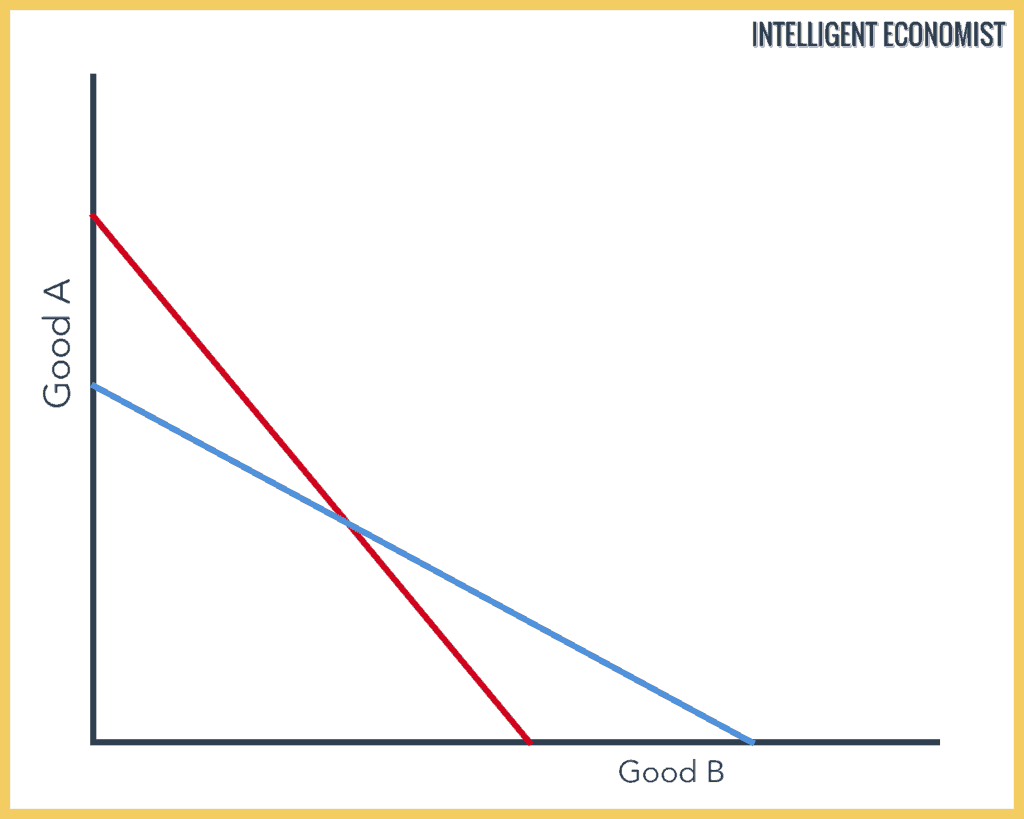

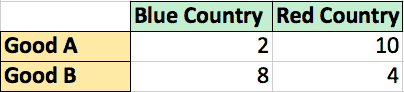

In our absolute advantage example, we assume that there are two countries, which are represented by a blue and red line. They are called Blue Country and Red Country respectively.

To keep things simple, we also assume that only two goods are produced. They are Good A and Good B. From the table below, we can determine how many hours it takes to create one product.

Consider this table, which gives hours required to produce one unit of Good A and Good B by Blue and Red country:

The Blue country has an Absolute Advantage in the production of Good A (2 hours). Blue county has an absolute advantage because it takes fewer hours to produce a unit of Good A than Red country, which takes 10 hours.

Red Country takes fewer hours to produce Good B (4 hours). Therefore Red Country has an Absolute Advantage in the production of Good B.

As a result, Blue Country will be better off if it specializes in the production of Good A.

Red Country will be better off if it specializes in Good B.

As you can see from our example, it makes sense for businesses and countries to trade with one another. All countries engaged in open trade benefit from lower costs of production.

Similar Posts:

- Comparative Advantage

- Factors of Production

- Production Possibilities Frontier

- Trade Barriers

- Trading Bloc

1 thought on “Absolute Advantage”

Very simply and clearly explained (my specific interest was in absolute and comparative advantage).

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Save my name and email in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Search Search Please fill out this field.

Absolute Advantage

Comparative advantage, the bottom line.

- Business Essentials

Absolute vs. Comparative Advantage: What’s the Difference?

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/troypic__troy_segal-5bfc2629c9e77c005142f6d9.jpg)

Yarilet Perez is an experienced multimedia journalist and fact-checker with a Master of Science in Journalism. She has worked in multiple cities covering breaking news, politics, education, and more. Her expertise is in personal finance and investing, and real estate.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/YariletPerez-d2289cb01c3c4f2aabf79ce6057e5078.jpg)

Absolute vs. Comparative Advantage: An Overview

Absolute advantage and comparative advantage are two important concepts in economics and international trade. They largely influence how and why nations and businesses devote resources to producing particular goods and services. Absolute advantage describes a scenario in which one entity can manufacture a product at a higher quality and a faster rate for a greater profit than another competing business or country can accomplish. Conversely, comparative advantage considers the opportunity costs involved when choosing to manufacture multiple types of goods with limited resources.

Key Takeaways

- Absolute advantage and comparative advantage are two concepts in economics and international trade.

- Absolute advantage refers to the uncontested superiority of a country or business to produce a particular good better.

- Comparative advantage introduces opportunity cost as a factor for analysis in choosing between different options for production diversification.

- Economist Adam Smith helped develop the concepts, suggesting that countries can specialize in goods they can produce efficiently and trade with others for goods they can't produce nearly as well.

- David Ricardo built on Smith's concepts by introducing comparative advantage, saying countries can benefit from trade even when they have absolute advantage in producing everything.

The differentiation between the varying abilities of companies and nations to produce goods efficiently is the basis for the concept of absolute advantage . As such, absolute advantage looks at the efficiency of producing a single product. It also looks at how to produce goods and services at a lower cost by using fewer inputs during the production process compared to the competition.

This analysis helps countries avoid producing goods and services that would yield little to no demand , which would ultimately lead to losses. A country's absolute advantage (or disadvantage) in a particular industry can play an important role in the types of products it chooses to produce. Some of the factors that can lead an entity to absolute advantage include:

- Lower labor costs

- Access to an abundant supply of (natural) resources

- A larger pool of available capital

For example, if Japan and Italy can both produce automobiles, but Italy can produce sports cars of a higher quality at a faster rate with greater profit, then Italy is said to have an absolute advantage in that particular industry. On the other hand, Japan may be better served to devote limited resources and labor to other types of vehicles (such as electric cars) or another industry altogether. This may help the country enjoy an absolute advantage rather than trying to compete with Italy's efficiency .

While absolute advantage refers to the superior production capabilities of one entity versus another in a single area, comparative advantage introduces the concept of opportunity cost.

Comparative advantage takes a more holistic view of production. In this case, the perspective lies in the fact that a country or business has the resources to produce a variety of goods and services rather than focus on just one product.

The opportunity cost of a given option is equal to the forfeited benefits that could have been achieved by choosing an available alternative in comparison. In general, when the profit from two products is identified, analysts would calculate the opportunity cost of choosing one option over the other.

For example, let's assume that China has the resources to produce either smartphones or computers, such that it can produce either 10 million computers or 10 million smartphones. Computers generate a higher profit , so the opportunity cost is the difference in value lost from producing a smartphone rather than a computer. If China earns $100 for a computer and $50 for a smartphone, then the opportunity cost is $500 million. So, if China has to choose between producing computers over smartphones, it will probably select computers because the chance of profit is higher.

Adam Smith is often considered to be the father of modern economics.

History of Absolute Advantage and Comparative Advantage

Scottish economist Adam Smith helped originate the concepts of absolute and comparative advantage in his book, The Wealth of Nations. Smith argued that countries should specialize in the goods they can produce most efficiently and trade for any products they can't produce as well.

Smith described specialization and international trade as they relate to absolute advantage. He suggested that England could produce more textiles per labor hour and Spain could produce more wine per labor hour, so England should export textiles and import wine, and Spain should do the opposite.

Smith made several basic assumptions for his theory to work, including:

- No change to the factors of production between different countries

- The lack of trade barriers

- An equal balance of exports and imports

- No economies of scale

British economist David Ricardo later built on Smith's concepts by more broadly introducing comparative advantage in the early 19th century. He became well-known throughout history for his musings on comparative advantage. According to Ricardo, nations can benefit from trading even if one of them has an absolute advantage in producing everything. In other words, countries must choose to diversify the goods and services they produce, which requires them to consider opportunity costs.

What Is Adam Smith's Theory of Absolute Advantage?

Scottish economist Adam Smith is credited with developing the theory behind absolute and creative advantage. He wrote about them in his book, The Wealth of Nations. According to Smith, countries should focus on goods they can produce efficiently and use trade to acquire anything they can't make themselves.

What Is an Example of Absolute Advantage?

There are many examples of absolute advantage, especially in the real world. For instance, Saudi Arabia's oil reserves are abundant, giving it an absolute advantage. That's one reason it exports the commodity to other nations worldwide.

How Do You Calculate Absolute Advantage?

To calculate absolute advantage, examine the output of the product in question between two entities. The one with the larger output has the absolute advantage. To demonstrate, let's use this example. Let's say that with the exact same resources, Worker A produces 60 glue sticks and 25 large foam pads per hour, and Worker B produces 20 glue sticks and 35 foam pads per hour. Worker A has the absolute advantage for glue sticks, while Worker B has the absolute advantage for foam pads.

How Do You Define Comparative Advantage?

Comparative advantage is often contrasted with absolute advantage. Where absolute advantage refers to the ability of an entity to produce a greater quantity of a product or service, comparative advantage refers to the ability to produce goods and services at a lower opportunity cost compared to the competition.

What Is the Benefit of Reaching Absolute Advantage in the Production of One Good?

The benefit of reaching absolute advantage when it comes to producing a single good or service boils down to pure economics and profit. Making a product that others need (and can't produce) allows you to initiate a trade relationship for goods and services you need but can't produce yourself. This will enable you to profit from the sale of your (specialized) goods and still be able to enjoy the goods you import from your trading partner(s).

The idea of absolute advantage was developed by Scottish economist Adam Smith, who explained how countries can profit by only specializing in the goods and services they can produce efficiently. Smith suggested that countries can open up trade with others for products they can't make efficiently on their own.

The concept is often contrasted with comparative advantage, which was explored after Smith by economists like David Ricardo. He suggested that countries produce goods and services not necessarily at a greater volume or quality but at lower opportunity costs. These ideas have evolved since they were first developed, but the fundamental basis is still prevalent in production and international trade today.

Project Gutenberg. " An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations ."

Adam Smith via Bibliomania. " The Wealth of Nations ."

Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). " Ricardo's Difficult Idea ."

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/ABSOLUTE-ADVANTAGE-FINAL-edit-32a9742eecf944bc870f2de10a452ec5.jpg)

- Terms of Service

- Editorial Policy

- Privacy Policy

- Your Privacy Choices

Agribusiness Management and Trade 3(3+0)

Lesson-37 absolute advantage theory of international trade.

37.1 INTRODUCTION

The exchange of goods across the national borders is termed as international trade. Countries differ widely in terms of the products and services traded. Countries rarely follow the trade structure of the other nations; rather they evolve their own product portfolios and trade patterns for exports and imports. Besides, nations have marked differences in their vulnerabilities to the upheavals in exogenous factors. There are various theories of international trade which are grouped in to classical and neo-classical theories. We will discuss only the classical theory of international trade. This lesson aims to discuss absolute advantage theory of international trade and the next lesson you are going to study the comparative advantage theory of international trade. This will provide a conceptual understanding of the fundamental principles of international trade and shifts in trade patterns.

37.2 THEORY OF MERCANTILISM

The theory of mercantilism attributes and measures the wealth of a nation by the size of its accumulated treasures. Accumulated wealth is traditionally measured in terms of gold, as earlier gold and silver were considered the currency of international trade. Mercantilists, therefore, suggested that the fundamental task of the national government is to acquire as much of gold and other precious metals as possible, through foreign trade. The only way in which this can be accomplished by a country is, when it is able to run perpetually favourable balance of trade for itself. i.e. by exporting more and more and importing less and less. The difference between exports and imports, which must be always in favour of the nation, would be settled by an inflow of gold and other precious metals. The more gold the nation had, richer and more powerful it would be. All this could be guaranteed by foreign trade that is in favour of the country. The mercantilists, as great “nation builders” advocated that the government should adopt policies which are designed to restrict imports and stimulate exports; because we lose gold by importing and earn gold by exporting. The theory of mercantilism aims at creating trade surplus, which in turn contributes to the accumulation of a nation’s wealth. Between the 16 th and 19 th centuries, European colonial powers actively pursued international trade to increase their treasury of goods, which were in turn invested to build a powerful army and infrastructure.

Mercantilism was implemented by active government interventions, which focused on maintaining trade surplus and expansion of colonization. National governments imposed restrictions on imports through tariffs and quotas and promoted exports by subsidizing production. The colonies served as cheap sources for primary commodities, such as raw cotton, grains, spices, herbs and medicinal plants, tea, coffee, and fruits, both for consumption and also as raw material for industries. Thus, the policy of mercantilism greatly assisted and benefited the colonial powers in accumulating wealth.

The main limitation of this theory is, accumulation of wealth takes place at the cost of another trading partner. If one nation has to gain from international trade the partner country must lose. Therefore, international trade is treated as a win-lose game resulting virtually in no contribution of global wealth. Thus, international trade becomes zero-sum game.

A number of national governments still seem to cling to the mercantilist theory, and exports rather than imports are actively promoted. This also explains the reason behind the ‘import substitution strategy’ adopted by a large number of countries prior to economic liberalization. This strategy was guided by their keenness to contain imports and promote domestic production even at the cost of efficiency and higher production costs. It has resulted in the creation of a large number of export promotion organizations that look after the promotion of exports from the country. However, import promotion agencies are uncommon in most nations. Presently, the terminology used under this trade theory is neo-mercantilism, which aims at creating favourable trade balance and has been employed by a number of countries to create trade surplus.

37.3 THEORY OF ABSOLUTE ADVANTAGE

In 1776, Adam Smith published his famous book The Wealth of Nations, in which he attacked the mercantilist view and showed that it was all wrong and illogical, for one thing, not all nations can have an export surplus simultaneously. Mercantilist policy, therefore, cannot be considered as international economic policy. Their policy was highly nationalistic and biased heavily against the other countries. It was Adam Smith who first developed a model of international trade and showed convincingly that all countries could gain form trade. Mercantilists had measured the wealth of nation by the stock of precious metals that the nation possessed. Adam Smith rejected all this and argued instead, that the wealth of a nation is measured by the amount of goods and services that a nation produced, or by what is today called Gross National Product (GNP). He developed the comparative advantage model, where he showed that international trade could bring gains to all trading nations, thereby improving the wealth and standards of living of all the participating nations. In his model of trade, unlike the mercantilist’s model, a nation need not gain only at the expense of other nations; here all nations gain together and simultaneously.

An absolute advantage refers to the ability of a country to produce a good more efficiently and cost-effectively than any other country. Smith elucidated the concept of ‘absolute advantage’ leading to gains from specialization with the day-to-day illustrations as follows:

“It is the maxim of every prudent master of a family, never to make at home what is will cost him more to make than to buy. The taylor does not attempt to make his own shoes, but buys them from shoemaker. The shoemaker does not attempt to make his own clothes, but employs a taylor. The farmer attempts to make neither…”

What is true in the conduct of a family may also be applied for the nations. If a foreign country can supply us with a commodity cheaper than we ourselves can make it, better buy it from them with some part of the produce of our own industry. Thus he advocated, instead of producing all products, each country should specialize in producing those goods that it can produce more efficiently. A country’s advantage may be either natural or acquired.

2.3.1 Natural Advantage

Natural factors, such as a country’s geographical and agro-climatic conditions, mineral or other natural resources, or specialized manpower contribute to a country’s natural advantage in certain products. For instance, the agro-climatic condition in India is an important factor for sizeable export of agro-produce, such as spices, cotton, tea and mangoes etc. The availability of relatively cheap labour contributes to India’s edge in export of labour-intensive products. The production of wheat and maize in US, petroleum in Saudi Arabia, citrus fruits in Israel, lumber in Canada, and aluminum ore in Jamaica are illustrations of natural advantages.

2.3.2 Acquired Advantage

The acquired advantage in either a product of its process technology plays an important role in creating such as shift. The ability to differentiate or produce a different product is termed as an advantage in product technology, while the ability to produce a homogenous product more efficiently is termed as an advantage in process technology. Development of software products in India, production of consumer electronics and automobiles in Japan, watches in Switzerland and shipbuilding in South Korea may be attributed to acquired advantage. Export centers in for precious and semi-precious stones in Jaipur, Surat, Navasari and Mumbai have come up not just because of their raw material resources but the skills they have developed in processing imported raw stones.

To appreciate the theory of absolute advantage, consider an example of two countries and two commodities model. Let Malaysia and India be the two such countries and Rubber and Textiles be the commodities. Assume that in the production of these commodities in two countries, there are constant returns to scale conditions i.e. there are constant marginal opportunity opportunity cost conditions in both countries in both commodities. Assume further production possibilities are such that both countries can produce both the goods if they wish. Finally assume that both countries have X amount of factors of production such that,

a. With X factors of production, Malaysia can produce either 100 units of rubber or 50 units of textiles, or mix of rubber and textiles in the opportunity cost ratio of 2:1 (i.e. to produce 1 more unit of textiles, it has to give up the opportunity of producing 2 units of rubber). b. With X factors of production India can produce either 50 units of rubber or 100 units of textiles. Or some other combination of rubber and textiles subject to the opportunity cost ratio of 1:2 (This means that India has to give up producing 1 unit of rubber in order to produce 2 units of textiles or alternatively, India has to give up the opportunity of producing 2 units of textiles in order to product 1 more unit of rubber).

From the above supply conditions it is quite clear that Malaysia has an absolute advantage in the production of rubber and India has the absolute advantage in the production of textiles. This shows there is scope for specialization in production and also of establishing mutually beneficial trade between the two countries. Now let us see how it happens.

First in a situation of autarky or no trade, each country can produce and consume independent of other country, a combination of rubber and textile as shown in table 37.1. Malaysia produces and consumes 50 units of rubber plus 25 units of textiles (total 75 units). India produces 25 units of rubber plus 50 units of textiles (total 75 units). Therefore, in absence of any trade, the total units produced in the world are 150 units.

Table 37.1. Production and consumption levels with no trade

Let us now examine what happens if they trade with each other. This is shown in the table 37.2. Malaysia would specialize in production of rubber and India in production of textiles with 100 units of rubber and textiles respectively by utilizing all the resources. Thus the total production in the world would be 200 units. Thus opening up trade resulted in higher production in both the countries. Both the countries became richer after trade in terms of production. This is production gain from international trade.

Table 37.2. Production levels after international trade

What about the consumption gain? This depends on how the gains from the production are distributed between the two countries. In other words, it depends on the terms of trade, i.e., how many units of rubber exchange for one unit of textiles between India and Malaysia.

Suppose terms of trade are fixed at 1:1 i.e., Malaysia and India agree to exchange 1 unit of rubber for 1 unit of textiles. Then depending on the taste pattern in the two countries and upon how much they want to trade each other’s goods, the consumption gains can be determined. Supposing that the consumers in both countries want to consume some mix of both the goods; then Malaysia could export say 40 units of rubber in exchange for 40 units of textile imports from India. The resulting situation will be like that is presented in table 37.3. Malaysia after trade has produced 100 units of rubber. Consumers wish to consume 60 units of rubber to India. Malaysia exports 40 units of rubber to India in exchange for 40 units of textile imports from India. Similarly for India, it imports 40 units of rubber and exports 40 units of textiles. India’s post trade consumption of rubber and textile is 40 and 60. Clearly consumers in both the countries have gained from the trade.

The same analogy can be applied what happens if the terms of trade are different.

Table 37.3. Consumption shares after international trade

Current course

Module 1. Management Concepts & Principle

Module 2. Management Functions

Module 3. Marketing Management

Module 4. Concepts and application of management p...

Module 5. Production, Consumption, Processing and ...

Module 6. Meaning & Theories of International ...

Module 7. WTO provisions for trade in agricultural...

Absolute Advantage Theory

The paper seeks to highlight on the relevance of the absolute advantage theory on the global market as compared to other theories of international trade. It also describes how the theory is applied using Japan and the United States of America as typical examples of countries that have gained from absolute advantage in relation to their respective major production areas. Moreover, complications and limitations of the theory have also been discussed.

Absolute Advantage Theory

The absolute advantage theory is one of the theories of international trade that make up the most influential potential body of economics. Others include mercantilism, and the theory of comparative advantage (Peng, 2008).

One country has an absolute advantage over another when its production of goods and services consumes comparatively fewer resources. A country is able to produce more output using the same volume of inputs. This theory is also applicable to various economic entities such as firms, regions and cities but a specific focus on countries is good enough to describe what the theory is all about. This is in line with the countries’ international trade flows and production decisions. Equating cost advantages with absolute advantages is a fallacy that presents a scenario of continued confusion (Marrewijk, 2008). The fact that the volume allocation of real resources might vary across different countries is what results into the significant deviation between the two.

The 17th century witnessed a reaction to the mercantilist theory that campaigned for a comprehensive regulation of trade for the purpose of enhancing wealth and growth. In effect, a free trade doctrine emerged by the end of the 18th century. The doctrine was further realized after Adam Smith’s publication of ‘An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations’ (Marrewijk, 2008). Smith through his work was able to develop a new view point as regards political economy. Regulations work to favor one industry by siphoning away resources from a different industry.

The opportunity cost principle applies to individuals when for instance, a tailor buys shoes from the shoemaker because it is not his or her line of specialization meaning that it would take him quite some time to make a pair (Marrewijk, 2008). It, therefore, explains that an individual finds it wise to concentrate with his/her line of specialization in order to realize competitive advantage. Peng (2008) reveals that other relevant principles include the specialization and opportunity costs principles. A country is able to concentrate in the efficient production of goods when it imports goods from other countries that have comparatively more efficient production. The technological differences between the exporting country and the importing country are what enhance international trade flows.

Download will start in 20 seconds

Choose an option to complete your free download

Note that all papers are meant for inspiration and reference purposes only! Do not copy papers in full or in part. Papers are provided by other students, who hold the copyright for the content of those papers. All papers were submitted to TurnItIn and will show up as plagiarism if you try to submit any part of them as your own work. Assignment Lab can not guarantee the quality of the user generated content such as sample papers above.

- Login with Facebook

- Keep me logged in Forgot password?

Restore Password

- Back to login form

New password was sent

Create new account

Please enter a valid email address. We will send you a verification code to this email address. Email verification is required to download essays

Please register to download

Please enter a valid email address to download a sample you requested. We will send you a verification code to this email address

Registration Successful

Registration failed.

- Economics Assignment Help

Absolute Advantage Theory

Absolute advantage theory assignment help | absolute advantage theory homework help.

The criticism of the mercantilism led to the birth of the absolute advantage theory. Economist claimed that with the mercantilism school of thought, countries would never perpetually increase their wealth through international trade but rather they will revolve around being bullion deficits and bullion surpluses. Adam Smith came up with a solution to this hitch in the international trade; the absolute advantage theory. This theory’s major implication is that it encourages wealth creation in foreign markets. When countries can easily import goods that they do not produce efficiently and produce only those they are great at, more wealth will be created since they are not limited by what they can produce hence allowing an opportunity for growth. Moreover, the absence of trade barriers allows increased specialization, mutual benefits from countries and increase in the market size which all translate to wealth creation.