How it works

For Business

Join Mind Tools

Article • 8 min read

The FOCUS Model

A simple, efficient problem-solving approach.

By the Mind Tools Content Team

Are your business processes perfect, or could you improve them?

In an ever-changing world, nothing stays perfect for long. To stay ahead of your competitors, you need to be able to refine your processes on an ongoing basis, so that your services remain efficient and your customers stay happy.

This article looks the FOCUS Model – a simple quality-improvement tool that helps you do this.

About the Model

The FOCUS Model, which was created by the Hospital Corporation of America (HCA), is a structured approach to Total Quality Management (TQM) , and it is widely used in the health care industry.

The model is helpful because it uses a team-based approach to problem solving and to business-process improvement, and this makes it particularly useful for solving cross-departmental process issues. Also, it encourages people to rely on objective data rather than on personal opinions, and this improves the quality of the outcome.

It has five steps:

- F ind the problem.

- O rganize a team.

- C larify the problem.

- U nderstand the problem.

- S elect a solution.

Applying the FOCUS Model

Follow the steps below to apply the FOCUS Model in your organization.

Step 1: Find the Problem

The first step is to identify a process that needs to be improved. Process improvements often follow the Pareto Principle , where 80 percent of issues come from 20 percent of problems. This is why identifying and solving one real problem can significantly improve your business, if you find the right problem to solve.

According to a popular analogy, identifying problems is like harvesting apples. At first, this is easy – you can pick apples up from the ground and from the lower branches of the tree. But the more fruit you collect, the harder it becomes. Eventually, the remaining fruit is all out of reach, and you need to use a ladder to reach the topmost branches.

Start with a simple problem to get the team up to speed with the FOCUS method. Then, when confidence is high, turn your attention to more complex processes.

If the problem isn't obvious, use these questions to identify possible issues:

- What would our customers want us to improve?

- How can we improve quality ?

- What processes don't work as efficiently as they could?

- Where do we experience bottlenecks in our processes?

- What do our competitors or comparators do that we could do?

- What frustrates and irritates our team?

- What might happen in the future that could become a problem for us?

If you have several problems that need attention, list them all and use Pareto Analysis , Decision Matrix Analysis , or Paired Comparison Analysis to decide which problem to address first. (If you try to address too much in one go, you'll overload team members and cause unnecessary stress.)

Step 2: Organize a Team

Your next step is to assemble a team to address the problem.

Where possible, bring together team members from a range of disciplines – this will give you a broad range of skills, perspectives, and experience to draw on.

Select team members who are familiar with the issue or process in hand, and who have a stake in its resolution. Enthusiasm for the project will be greatest if people volunteer for it, so emphasize how individuals will benefit from being involved.

If your first choice of team member isn't available, try to appoint someone close to them, or have another team member use tools like Perceptual Positioning and Rolestorming to see the issue from their point of view.

Keep in mind that a diverse team is more likely to find a creative solution than a group of people with the same outlook.

Step 3: Clarify the Problem

Before the team can begin to solve the problem, you need to define it clearly and concisely.

According to " Total Quality Management for Hospital Nutrition Services ," a key text on the FOCUS Model, an enthusiastic team may be keen to attack an "elephant-sized" problem, but the key to success is to break it down into "sushi-sized" pieces that can be analyzed and solved more easily.

Use the Drill Down technique to break big problems down into their component parts. You can also use the 5 Whys Technique , Cause and Effect Analysis , and Root Cause Analysis to get to the bottom of a problem.

Record the details in a problem statement, which will then serve as the focal point for the rest of the exercise ( CATWOE can help you do this effectively.) Focus on factual events and measurable conditions such as:

- Who does the problem affect?

- What has happened?

- Where is it occurring?

- When does it happen?

The problem statement must be objective, so avoid relying on personal opinions, gut feelings, and emotions. Also, be on guard against "factoids" – statements that appear to be facts, but that are really opinions that have come to be accepted as fact.

Step 4: Understand the Problem

Once the problem statement has been completed, members of the team gather data about the problem to understand it more fully.

Dedicate plenty of time to this stage, as this is where you will identify the fundamental steps in the process that, when changed, will bring about the biggest improvement.

Consider what you know about the problem. Has anyone else tried to fix a similar problem before? If so, what happened, and what can you learn from this?

Use a Flow Chart or Swim Lane Diagram to organize and visualize each step; this can help you discover the stage at which the problem is happening. And try to identify any bottlenecks or failures in the process that could be causing problems.

As you develop your understanding, potential solutions to the problem may become apparent. Beware of jumping to "obvious" conclusions – these could overlook important parts of the problem, and could create a whole new process that fails to solve the problem.

Generate as many possible solutions as you can through normal structured thinking, brainstorming , reverse brainstorming , and Provocation . Don't criticize ideas initially – just come up with lots of possible ideas to explore.

Step 5: Select a Solution

The final stage in the process is to select a solution.

Use appropriate decision-making techniques to select the most viable option. Decision Trees , Paired Comparison Analysis , and Decision Matrix Analysis are all useful tools for evaluating your options.

Once you've selected an idea, use tools such as Risk Analysis , "What If" Analysis , and the Futures Wheel to think about the possible consequences of moving ahead, and make a well-considered go/no-go decision to decide whether or not you should run the project.

People commonly use the FOCUS Model in conjunction with the Plan-Do-Check-Act cycle. Use this approach to implement your solutions in a controlled way.

The FOCUS Model is a simple quality-improvement tool commonly used in the health care industry. You can use it to improve any process, but it is particularly useful for processes that span different departments.

The five steps in FOCUS are as follows:

People often use the FOCUS Model in conjunction with the Plan-Do-Check-Act cycle, which allows teams to implement their solution in a controlled way.

Bataldan, P. (1992). 'Building Knowledge for Improvement: an Introductory Guide to the Use of FOCUS-PDCA,' Nashville: TN Quality Resource Group, Hospital Corporation of America.

Schiller, M., Miller-Kovach, M., and Miller-Kovach, K. (1994). 'Total Quality Management for Hospital Nutrition Services,' Aspen Publishers Inc. Available here .

You've accessed 1 of your 2 free resources.

Get unlimited access

Discover more content

Book Insights

Stolen Focus: Why You Can’t Pay Attention

By Johann Hari

Active Listening

Hear What People are Really Saying

Add comment

Comments (0)

Be the first to comment!

Get 30% off your first year of Mind Tools

Great teams begin with empowered leaders. Our tools and resources offer the support to let you flourish into leadership. Join today!

Sign-up to our newsletter

Subscribing to the Mind Tools newsletter will keep you up-to-date with our latest updates and newest resources.

Subscribe now

Business Skills

Personal Development

Leadership and Management

Member Extras

Most Popular

Latest Updates

The Role of a Facilitator

How to Manage Passive-Aggressive People

Mind Tools Store

About Mind Tools Content

Discover something new today

How can i manage passive-aggressive team members.

Dealing with passive aggression when it takes over your team

Written Communication

Discover how to construct an effective message, and test and hone your writing skills

How Emotionally Intelligent Are You?

Boosting Your People Skills

Self-Assessment

What's Your Leadership Style?

Learn About the Strengths and Weaknesses of the Way You Like to Lead

Recommended for you

Novel ways of networking video.

Video Transcript

Animated Video

Business Operations and Process Management

Strategy Tools

Customer Service

Business Ethics and Values

Handling Information and Data

Project Management

Knowledge Management

Self-Development and Goal Setting

Time Management

Presentation Skills

Learning Skills

Career Skills

Communication Skills

Negotiation, Persuasion and Influence

Working With Others

Difficult Conversations

Creativity Tools

Self-Management

Work-Life Balance

Stress Management and Wellbeing

Coaching and Mentoring

Change Management

Team Management

Managing Conflict

Delegation and Empowerment

Performance Management

Leadership Skills

Developing Your Team

Talent Management

Problem Solving

Decision Making

Member Podcast

7 Solution-Focused Therapy Techniques and Worksheets (+PDF)

It has analyzed a person’s problems from where they started and how those problems have an effect on that person’s life.

Out of years of observation of family therapy sessions, the theory and applications of solution-focused therapy developed.

Let’s explore the therapy, along with techniques and applications of the approach.

Before you read on, we thought you might like to download our three Positive Psychology Exercises for free . These science-based exercises will explore fundamental aspects of positive psychology including strengths, values, and self-compassion, and will give you the tools to enhance the wellbeing of your clients, students, or employees.

This Article Contains:

5 solution-focused therapy techniques, handy sft worksheets (pdf), solution-focused therapy interventions, 5 sft questions to ask clients, solution-focused brief therapy (sfbt techniques), 4 activities & exercises, best sft books, a take-home message.

Solution-focused therapy is a type of treatment that highlights a client’s ability to solve problems, rather than why or how the problem was created. It was developed over some time after observations of therapists in a mental health facility in Wisconsin by Steve de Shazer and Insoo Kim Berg and their colleagues.

Like positive psychology, Solution Focused Therapy (SFT) practitioners focus on goal-oriented questioning to assist a client in moving into a future-oriented direction.

Solution-focused therapy has been successfully applied to a wide variety of client concerns due to its broad application. It has been utilized in a wide variety of client groups as well. The approach presupposes that clients have some knowledge of what will improve their lives.

The following areas have utilized SFT with varying success:

- relationship difficulties

- drug and alcohol abuse

- eating disorders

- anger management

- communication difficulties

- crisis intervention

- incarceration recidivism reduction

Goal clarification is an important technique in SFT. A therapist will need to guide a client to envision a future without the problem with which they presented. With coaching and positive questioning, this vision becomes much more clarified.

With any presenting client concern, the main technique in SFT is illuminating the exception. The therapist will guide the client to an area of their life where there is an exception to the problem. The exception is where things worked well, despite the problem. Within the exception, an approach for a solution may be forged.

The ‘miracle question’ is another technique frequently used in SFT. It is a powerful tool that helps clients to move into a solution orientation. This question allows clients to begin small steps toward finding solutions to presenting problems (Santa Rita Jr., 1998). It is asked in a specific way and is outlined later in this article.

Experiment invitation is another way that therapists guide clients into solution orientation. By inviting clients to build on what is already working, clients automatically focus on the positive. In positive psychology, we know that this allows the client’s mind to broaden and build from that orientation.

Utilizing what has been working experimentally allows the client to find what does and doesn’t work in solving the issue at hand. During the second half of a consultation with a client, many SFT therapists take a break to reflect on what they’ve learned during the beginning of the session.

Consultation breaks and invitations for more information from clients allow for both the therapist and client to brainstorm on what might have been missed during the initial conversations. After this break, clients are complemented and given a therapeutic message about the presenting issue. The message is typically stated in the positive so that clients leave with a positive orientation toward their goals.

Here are four handy worksheets for use with solution-focused therapy.

- Miracle worksheet

- Exceptions to the Problem Worksheet

- Scaling Questions Worksheet

- SMART+ Goals Worksheet

Download 3 Free Positive Psychology Exercises (PDF)

Enhance wellbeing with these free, science-based exercises that draw on the latest insights from positive psychology.

Download 3 Free Positive Psychology Tools Pack (PDF)

By filling out your name and email address below.

Compliments are frequently used in SFT, to help the client begin to focus on what is working, rather than what is not. Acknowledging that a client has an impact on the movement toward a goal allows hope to become present. Once hope and perspective shift occurs, a client can decide what daily actions they would like to take in attaining a goal.

Higher levels of hope and optimism can predict the following desirable outcomes (Peterson & Seligman, 2004):

- achievement in all sorts of areas

- freedom from anxiety and depression

- improved social relationships

- improved physical well being

Mind mapping is an effective intervention also used to increase hope and optimism. This intervention is often used in life coaching practices. A research study done on solution-focused life coaching (Green, Oades, & Grant, 2006) showed that this type of intervention increases goal striving and hope, in addition to overall well-being.

Though life coaching is not the same as therapy, this study shows the effectiveness of improving positive behavior through solution-focused questioning.

Mind mapping is a visual thinking tool that helps structure information. It helps clients to better analyze, comprehend, and generate new ideas in areas they might not have been automatically self-generated. Having it on paper gives them a reference point for future goal setting as well.

Empathy is vital in the administration of SFBT. A client needs to feel heard and held by the practitioner for any forward movement to occur. Intentionally leaning in to ensure that a client knows that the practitioner is engaged in listening is recommended.

Speaking to strengths and aligning those strengths with goal setting are important interventions in SFT. Recognizing and acknowledging what is already working for the client validates strengths. Self-recognition of these strengths increases self-esteem and in turn, improves forward movement.

The questions asked in Solution-Focused Therapy are positively directed and in a goal-oriented stance. The intention is to allow a perspective shift by guiding clients in the direction of hope and optimism to lead them to a path of positive change. Results and progress come from focusing on the changes that need to be made for goal attainment and increased well being.

1. Miracle Question

Here is a clear example of how to administer the miracle question. It should be delivered deliberately. When done so, it allows the client to imagine the miracle occurring.

“ Now, I want to ask you a strange question. Suppose that while you are sleeping tonight and the entire house is quiet, a miracle happens. The miracle is that the problem which brought you here is solved. However, because you are sleeping, you don’t know that the miracle has happened. So, when you wake up tomorrow morning, what will be different that will tell you that a miracle has happened and the problem which brought you here is solved? ” (de Shazer, 1988)

2. Presupposing change questions

A practitioner of solution-focused therapy asks questions in an approach derived way.

Here are a few examples of presupposing change questions:

“What stopped complete disaster from occurring?” “How did you avoid falling apart.” “What kept you from unraveling?”

3. Exception Questions

Examples of exception questions include:

1. Tell me about times when you don’t get angry. 2. Tell me about times you felt the happiest. 3. When was the last time that you feel you had a better day? 4. Was there ever a time when you felt happy in your relationship? 5. What was it about that day that made it a better day? 6. Can you think of a time when the problem was not present in your life?

4. Scaling Questions

These are questions that allow a client to rate their experience. They also allow for a client to evaluate their motivation to change their experience. Scaling questions allow for a practitioner to add a follow-up question that is in the positive as well.

An example of a scaling question: “On a scale of 1-10, with 10 representing the best it can be and one the worst, where would you say you are today?”

A follow-up question: “ Why a four and not a five?”

Questions like these allow the client to explore the positive, as well as their commitment to the changes that need to occur.

5. Coping Questions

These types of questions open clients up to their resiliency. Clients are experts in their life experience. Helping them see what works, allows them to grow from a place of strength.

“How have you managed so far?” “What have you done to stay afloat?” “What is working?”

3 Scaling questions from Solution Focused Therapy – Uncommon Practitioners

The main idea behind SFBT is that the techniques are positively and solution-focused to allow a brief amount of time for the client to be in therapy. Overall, improving the quality of life for each client, with them at the center and in the driver’s seat of their growth. SFBT typically has an average of 5-8 sessions.

During the sessions, goals are set. Specific experimental actions are explored and deployed into the client’s daily life. By keeping track of what works and where adjustments need to be made, a client is better able to track his or her progress.

A method has developed from the Miracle Question entitled, The Miracle Method . The steps follow below (Miller & Berg, 1996). It was designed for combatting problematic drinking but is useful in all areas of change.

- State your desire for something in your life to be different.

- Envision a miracle happening, and your life IS different.

- Make sure the miracle is important to you.

- Keep the miracle small.

- Define the change with language that is positive, specific, and behavioral.

- State how you will start your journey, rather than how you will end it.

- Be clear about who, where, and when, but not the why.

A short selection of exercises which can be used

1. Solution-focused art therapy/ letter writing

A powerful in-session task is to request a client to draw or write about one of the following, as part of art therapy :

- a picture of their miracle

- something the client does well

- a day when everything went well. What was different about that day?

- a special person in their life

2. Strengths Finders

Have a client focus on a time when they felt their strongest. Ask them to highlight what strengths were present when things were going well. This can be an illuminating activity that helps clients focus on the strengths they already have inside of them.

A variation of this task is to have a client ask people who are important in their lives to tell them how they view the client’s strengths. Collecting strengths from another’s perspective can be very illuminating and helpful in bringing a client into a strength perspective.

3. Solution Mind Mapping

A creative way to guide a client into a brainstorm of solutions is by mind mapping. Have the miracle at the center of the mind map. From the center, have a client create branches of solutions to make that miracle happen. By exploring solution options, a client will self-generate and be more connected to the outcome.

4. Experiment Journals

Encourage clients to do experiments in real-life settings concerning the presenting problem. Have the client keep track of what works from an approach perspective. Reassure the client that a variety of experiments is a helpful approach.

17 Top-Rated Positive Psychology Exercises for Practitioners

Expand your arsenal and impact with these 17 Positive Psychology Exercises [PDF] , scientifically designed to promote human flourishing, meaning, and wellbeing.

Created by Experts. 100% Science-based.

These books are recommended reads for solution-focused therapy.

1. The Miracle Method: A Radically New Approach to Problem Drinking – Insoo Kim Berg and Scott D. Miller Ph.D.

The Miracle Method by Scott D. Miller and Insoo Kim Berg is a book that has helped many clients overcome problematic drinking since the 1990s.

By utilizing the miracle question in the book, those with problematic drinking behaviors are given the ability to envision a future without the problem.

Concrete, obtainable steps in reaching the envisioned future are laid out in this supportive read.

Available on Amazon .

2. Solution Focused Brief Therapy: 100 Key Points and Techniques – Harvey Ratney, Evan George and Chris Iveson

Solution Focused Brief Therapy: 100 Key Points and Techniques is a well-received book on solution-focused therapy. Authors Ratner, George, and Iveson provide a concisely written and easily understandable guide to the approach.

Its accessibility allows for quick and effective change in people’s lives.

The book covers the approach’s history, philosophical underpinnings, techniques, and applications. It can be utilized in organizations, coaching, leadership, school-based work, and even in families.

The work is useful for any practitioner seeking to learn the approach and bring it into practice.

3. Handbook of Solution-Focused Brief Therapy (Jossey-Bass Psychology) – Scott D. Miller, Mark Hubble and Barry L. Duncan

It includes work from 28 of the lead practitioners in the field and how they have integrated the solution-focused approach with the problem-focused approach.

It utilizes research across treatment modalities to better equip new practitioners with as many tools as possible.

4. More Than Miracles: The State of the Art of Solution -Focused Therapy (Routledge Mental Health Classic Editions) – Steve de Shazer and Yvonne Dolan

It allows the reader to peek into hundreds of hours of observation of psychotherapy.

It highlights what questions work and provides a thoughtful overview of applications to complex problems.

Solution-Focused Therapy is an approach that empowers clients to own their abilities in solving life’s problems. Rather than traditional psychotherapy that focuses on how a problem was derived, SFT allows for a goal-oriented focus to problem-solving. This approach allows for future-oriented, rather than past-oriented discussions to move a client forward toward the resolutions of their present problem.

This approach is used in many different areas, including education, family therapy , and even in office settings. Creating cooperative and collaborative opportunities to problem solve allows mind-broadening capabilities. Illuminating a path of choice is a compelling way to enable people to explore how exactly they want to show up in this world.

Thanks for reading!

We hope you enjoyed reading this article. Don’t forget to download our three Positive Psychology Exercises for free .

- de Shazer, S. (1988). Clues: Investigating solutions in brief therapy. New York, NY: W.W. Norton and Co.

- Green, L. S., Oades, L. G., & Grant, A. M. (2006). Cognitive-behavioral, solution-focused life coaching: Enhancing goal striving, well-being, and hope. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 1 (3), 142-149.

- Miller, S. D., & Berg, I. K. (1996). The miracle method: A radically new approach to problem drinking. New York, NY: W.W. Norton and Co.

- Peterson, C., & Seligman, M. E. P., (2004). Character strengths and virtues: A handbook and classification (Vol. 1). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Santa Rita Jr, E. (1998). What do you do after asking the miracle question in solution-focused therapy. Family Therapy, 25( 3), 189-195.

Share this article:

Article feedback

What our readers think.

This was so amazing and helpful

excellent article and useful for applications in day today life activities .I will like at use when required and feasible to practice.

Let us know your thoughts Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published.

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Related articles

The Empty Chair Technique: How It Can Help Your Clients

Resolving ‘unfinished business’ is often an essential part of counseling. If left unresolved, it can contribute to depression, anxiety, and mental ill-health while damaging existing [...]

29 Best Group Therapy Activities for Supporting Adults

As humans, we are social creatures with personal histories based on the various groups that make up our lives. Childhood begins with a family of [...]

47 Free Therapy Resources to Help Kick-Start Your New Practice

Setting up a private practice in psychotherapy brings several challenges, including a considerable investment of time and money. You can reduce risks early on by [...]

Read other articles by their category

- Body & Brain (49)

- Coaching & Application (58)

- Compassion (25)

- Counseling (51)

- Emotional Intelligence (23)

- Gratitude (18)

- Grief & Bereavement (21)

- Happiness & SWB (40)

- Meaning & Values (26)

- Meditation (20)

- Mindfulness (44)

- Motivation & Goals (45)

- Optimism & Mindset (34)

- Positive CBT (29)

- Positive Communication (20)

- Positive Education (47)

- Positive Emotions (32)

- Positive Leadership (18)

- Positive Parenting (15)

- Positive Psychology (34)

- Positive Workplace (37)

- Productivity (17)

- Relationships (43)

- Resilience & Coping (37)

- Self Awareness (21)

- Self Esteem (38)

- Strengths & Virtues (32)

- Stress & Burnout Prevention (34)

- Theory & Books (46)

- Therapy Exercises (37)

- Types of Therapy (64)

- The Art & Science of Coaching Level 1 & 2

- The Art & Science of Coaching Level 3

- Team Coaching

- Master Your Coaching

- Tuition Fees

- Blogs, videos, downloadables

- Upcoming Webinars

- Speak to an Advisor

Key Skills for Solution-Focused Problem-Solving

Imagine that you just received an unexpected complex problem and need to find a solution fast. You have never experienced this situation before. What is your approach? Most of us focus on the problem by asking questions such as: “Why do I have this problem? What shall I do to get rid of this problem? Are you sure this is my problem?” Before you know it, the challenge becomes bigger by the minute. Your attention and effort are fully focused on overcoming the problem and you begin to feel less resourceful to find an acceptable solution.

When you focus on the problem instead of the desired outcome, you get stuck in the depths of the problem, as if you are in quicksand. Some people walk into the quicksand with lead boots on. One of the most powerful frames you can use to achieve results is to shift from a problem approach (I don’t want X) to an outcome approach (What I want is Y). This immediately shifts your thinking and the way you feel.

Only when your frame of mind is changed to focusing on the desired result can you begin to move forward toward the desired outcome. Using the Solution-Focused approach, you will be surprised how competently you can tackle even the thorniest of problems and turn them into opportunities.

Interested in becoming a coach? Discover how Solution-Focused coaching skills enable you to create transformational change in yourself and others.

Solution-Focused communication magnetizes our attention toward getting the desired outcome, and so the outcome is held in mind as the vision for the future . Others naturally tend to respond positively to our leadership because we hold the vision that serves everyone. Rather than dwelling on the difficulties or the setbacks, the idea of the solution becomes the road to results, and people feel cheered when they can see a strong pathway toward the solution and are inspired by the plan.

Imagine running a race where there are hurdles every 100 yards. With problem framing, you are focused on the hurdles, “Oh my, how high they are! How hard will I have to work to jump them?” Such a focus, with little or no attention on the finish line, will not make you a champion—guaranteed! The hurdles symbolically (and in reality) stand in your way. When you are focused on the hurdles, you cannot see past them to the finish line that is your true aim. The hurdles loom large in your mind, and the race seems difficult (if not impossible) to run.

With a Solution-Focused approach to communication, your mind is galvanized by your purpose and you are able to see past the hurdles before you. Your purpose always leads you to the finish line, and the hurdles become less important and less of an obstacle. In fact, they may seem so unimportant that they become nonexistent and are just part of the journey. They are still the same height and you’ll still have to jump as high. Yet with the focus on the value of the goal and what is working to move forward towards it, jumping hurdles seems natural and easy. The end of the race is always drawing you onward. The race itself becomes a means to achieve the vision, and it’s the vision—who you are becoming and who you are contributing to—that looms large in your mind. This difference in your focus is the power that leads you to success.

Notice how efficient this approach is – Solution-Focused thinking is far more useful than problem-focused thinking because the focus is on getting the desired outcome, rather than dwelling on the difficulties or setbacks. Constantly operating from a solution perspective is a noticeable characteristic of high achievers.

Focusing on who you are becoming

One of the main ways of producing Solution-Focused results that serve the world is to focus the mind and heart on who you are becoming— and not what you are overcoming. Allowing yourself to go into the lower energies of an overcoming focus puts you into a very challenging and unpleasant hurdle race. People can spend most of their lives running such a race. As soon as you put your attention on what doesn’t work as a ‘reality,’ it is hard to explore what really could work. This is one reason why the Erickson Solution-Focused method is successful in moving people quickly beyond mindsets and models that ‘realistically’ start by focusing on the problem as the necessary aspects to deal with.

As a transformational communicator using the coaching approach, once you are secure in this skill for yourself, you will quickly discover the value of using it consistently in coaching conversations with others. This simple and subtle skill of flipping a problem or conflict into a Solution-Focused orientation may be the single most powerful characteristic of transformational coaches who become known as integral change maestros.

Declaring and visualizing outcomes

When outcomes are declared and visualized carefully, people move toward them naturally, almost effortlessly. What was once considered a problem is now little more than a pebble on the road! Having a strong, inspiring, value-based vision for the future cuts all other concerns down to size. We grow and our ‘problems’ diminish.

Once you, the transformational communicator, know how to consciously assist people to orient toward their larger purpose and goals, your clients will move consistently and more easily toward their desired outcomes. They will achieve their outcomes by choice, not by chance.

Creating a compelling future

Developing, holding, and feeling a vision of a compelling future is the single most important task for a person, in order to achieve their goals and dreams.

Without this vision and the process of consistently visualizing potential action steps to accomplish it, people move in a random, scattered fashion. They are likely to struggle and get frustrated and stuck.

When people make the choice to hold a specific outcome securely on the movie screen of their minds, they naturally begin to move toward making their vision a reality—no matter how large or small it is. Their chosen outcome becomes their future.

Who you are is the future you are moving into! What is in your mind becomes your reality. You have two choices. You can visualize how your problems continue, which will move you towards having even more problems. Or, you can visualize your outcome becoming real and move toward having it. Which do you prefer?

Other articles YOU MAY LIKE

A Fresh Approach to Performance Reviews: What Works Well and Even Better If

Ways to Stay Productive During the Holidays as a Coach

How Coaching Benefits Leaders and Managers

- The Art of Effective Problem Solving: A Step-by-Step Guide

- Learn Lean Sigma

- Problem Solving

Whether we realise it or not, problem solving skills are an important part of our daily lives. From resolving a minor annoyance at home to tackling complex business challenges at work, our ability to solve problems has a significant impact on our success and happiness. However, not everyone is naturally gifted at problem-solving, and even those who are can always improve their skills. In this blog post, we will go over the art of effective problem-solving step by step.

You will learn how to define a problem, gather information, assess alternatives, and implement a solution, all while honing your critical thinking and creative problem-solving skills. Whether you’re a seasoned problem solver or just getting started, this guide will arm you with the knowledge and tools you need to face any challenge with confidence. So let’s get started!

Table of Contents

Problem solving methodologies.

Individuals and organisations can use a variety of problem-solving methodologies to address complex challenges. 8D and A3 problem solving techniques are two popular methodologies in the Lean Six Sigma framework.

Methodology of 8D (Eight Discipline) Problem Solving:

The 8D problem solving methodology is a systematic, team-based approach to problem solving. It is a method that guides a team through eight distinct steps to solve a problem in a systematic and comprehensive manner.

The 8D process consists of the following steps:

- Form a team: Assemble a group of people who have the necessary expertise to work on the problem.

- Define the issue: Clearly identify and define the problem, including the root cause and the customer impact.

- Create a temporary containment plan: Put in place a plan to lessen the impact of the problem until a permanent solution can be found.

- Identify the root cause: To identify the underlying causes of the problem, use root cause analysis techniques such as Fishbone diagrams and Pareto charts.

- Create and test long-term corrective actions: Create and test a long-term solution to eliminate the root cause of the problem.

- Implement and validate the permanent solution: Implement and validate the permanent solution’s effectiveness.

- Prevent recurrence: Put in place measures to keep the problem from recurring.

- Recognize and reward the team: Recognize and reward the team for its efforts.

Download the 8D Problem Solving Template

A3 Problem Solving Method:

The A3 problem solving technique is a visual, team-based problem-solving approach that is frequently used in Lean Six Sigma projects. The A3 report is a one-page document that clearly and concisely outlines the problem, root cause analysis, and proposed solution.

The A3 problem-solving procedure consists of the following steps:

- Determine the issue: Define the issue clearly, including its impact on the customer.

- Perform root cause analysis: Identify the underlying causes of the problem using root cause analysis techniques.

- Create and implement a solution: Create and implement a solution that addresses the problem’s root cause.

- Monitor and improve the solution: Keep an eye on the solution’s effectiveness and make any necessary changes.

Subsequently, in the Lean Six Sigma framework, the 8D and A3 problem solving methodologies are two popular approaches to problem solving. Both methodologies provide a structured, team-based problem-solving approach that guides individuals through a comprehensive and systematic process of identifying, analysing, and resolving problems in an effective and efficient manner.

Step 1 – Define the Problem

The definition of the problem is the first step in effective problem solving. This may appear to be a simple task, but it is actually quite difficult. This is because problems are frequently complex and multi-layered, making it easy to confuse symptoms with the underlying cause. To avoid this pitfall, it is critical to thoroughly understand the problem.

To begin, ask yourself some clarifying questions:

- What exactly is the issue?

- What are the problem’s symptoms or consequences?

- Who or what is impacted by the issue?

- When and where does the issue arise?

Answering these questions will assist you in determining the scope of the problem. However, simply describing the problem is not always sufficient; you must also identify the root cause. The root cause is the underlying cause of the problem and is usually the key to resolving it permanently.

Try asking “why” questions to find the root cause:

- What causes the problem?

- Why does it continue?

- Why does it have the effects that it does?

By repeatedly asking “ why ,” you’ll eventually get to the bottom of the problem. This is an important step in the problem-solving process because it ensures that you’re dealing with the root cause rather than just the symptoms.

Once you have a firm grasp on the issue, it is time to divide it into smaller, more manageable chunks. This makes tackling the problem easier and reduces the risk of becoming overwhelmed. For example, if you’re attempting to solve a complex business problem, you might divide it into smaller components like market research, product development, and sales strategies.

To summarise step 1, defining the problem is an important first step in effective problem-solving. You will be able to identify the root cause and break it down into manageable parts if you take the time to thoroughly understand the problem. This will prepare you for the next step in the problem-solving process, which is gathering information and brainstorming ideas.

Step 2 – Gather Information and Brainstorm Ideas

Gathering information and brainstorming ideas is the next step in effective problem solving. This entails researching the problem and relevant information, collaborating with others, and coming up with a variety of potential solutions. This increases your chances of finding the best solution to the problem.

Begin by researching the problem and relevant information. This could include reading articles, conducting surveys, or consulting with experts. The goal is to collect as much information as possible in order to better understand the problem and possible solutions.

Next, work with others to gather a variety of perspectives. Brainstorming with others can be an excellent way to come up with new and creative ideas. Encourage everyone to share their thoughts and ideas when working in a group, and make an effort to actively listen to what others have to say. Be open to new and unconventional ideas and resist the urge to dismiss them too quickly.

Finally, use brainstorming to generate a wide range of potential solutions. This is the place where you can let your imagination run wild. At this stage, don’t worry about the feasibility or practicality of the solutions; instead, focus on generating as many ideas as possible. Write down everything that comes to mind, no matter how ridiculous or unusual it may appear. This can be done individually or in groups.

Once you’ve compiled a list of potential solutions, it’s time to assess them and select the best one. This is the next step in the problem-solving process, which we’ll go over in greater detail in the following section.

Step 3 – Evaluate Options and Choose the Best Solution

Once you’ve compiled a list of potential solutions, it’s time to assess them and select the best one. This is the third step in effective problem solving, and it entails weighing the advantages and disadvantages of each solution, considering their feasibility and practicability, and selecting the solution that is most likely to solve the problem effectively.

To begin, weigh the advantages and disadvantages of each solution. This will assist you in determining the potential outcomes of each solution and deciding which is the best option. For example, a quick and easy solution may not be the most effective in the long run, whereas a more complex and time-consuming solution may be more effective in solving the problem in the long run.

Consider each solution’s feasibility and practicability. Consider the following:

- Can the solution be implemented within the available resources, time, and budget?

- What are the possible barriers to implementing the solution?

- Is the solution feasible in today’s political, economic, and social environment?

You’ll be able to tell which solutions are likely to succeed and which aren’t by assessing their feasibility and practicability.

Finally, choose the solution that is most likely to effectively solve the problem. This solution should be based on the criteria you’ve established, such as the advantages and disadvantages of each solution, their feasibility and practicability, and your overall goals.

It is critical to remember that there is no one-size-fits-all solution to problems. What is effective for one person or situation may not be effective for another. This is why it is critical to consider a wide range of solutions and evaluate each one based on its ability to effectively solve the problem.

Step 4 – Implement and Monitor the Solution

When you’ve decided on the best solution, it’s time to put it into action. The fourth and final step in effective problem solving is to put the solution into action, monitor its progress, and make any necessary adjustments.

To begin, implement the solution. This may entail delegating tasks, developing a strategy, and allocating resources. Ascertain that everyone involved understands their role and responsibilities in the solution’s implementation.

Next, keep an eye on the solution’s progress. This may entail scheduling regular check-ins, tracking metrics, and soliciting feedback from others. You will be able to identify any potential roadblocks and make any necessary adjustments in a timely manner if you monitor the progress of the solution.

Finally, make any necessary modifications to the solution. This could entail changing the solution, altering the plan of action, or delegating different tasks. Be willing to make changes if they will improve the solution or help it solve the problem more effectively.

It’s important to remember that problem solving is an iterative process, and there may be times when you need to start from scratch. This is especially true if the initial solution does not effectively solve the problem. In these situations, it’s critical to be adaptable and flexible and to keep trying new solutions until you find the one that works best.

To summarise, effective problem solving is a critical skill that can assist individuals and organisations in overcoming challenges and achieving their objectives. Effective problem solving consists of four key steps: defining the problem, generating potential solutions, evaluating alternatives and selecting the best solution, and implementing the solution.

You can increase your chances of success in problem solving by following these steps and considering factors such as the pros and cons of each solution, their feasibility and practicability, and making any necessary adjustments. Furthermore, keep in mind that problem solving is an iterative process, and there may be times when you need to go back to the beginning and restart. Maintain your adaptability and try new solutions until you find the one that works best for you.

- Novick, L.R. and Bassok, M., 2005. Problem Solving . Cambridge University Press.

Daniel Croft

Daniel Croft is a seasoned continuous improvement manager with a Black Belt in Lean Six Sigma. With over 10 years of real-world application experience across diverse sectors, Daniel has a passion for optimizing processes and fostering a culture of efficiency. He's not just a practitioner but also an avid learner, constantly seeking to expand his knowledge. Outside of his professional life, Daniel has a keen Investing, statistics and knowledge-sharing, which led him to create the website learnleansigma.com, a platform dedicated to Lean Six Sigma and process improvement insights.

Innovate to Accelerate: Strategies for Operational Excellence

7 Reasons Continuous Improvement Fails in Businesses

Free lean six sigma templates.

Improve your Lean Six Sigma projects with our free templates. They're designed to make implementation and management easier, helping you achieve better results.

5S Floor Marking Best Practices

In lean manufacturing, the 5S System is a foundational tool, involving the steps: Sort, Set…

How to Measure the ROI of Continuous Improvement Initiatives

When it comes to business, knowing the value you’re getting for your money is crucial,…

8D Problem-Solving: Common Mistakes to Avoid

In today’s competitive business landscape, effective problem-solving is the cornerstone of organizational success. The 8D…

The Evolution of 8D Problem-Solving: From Basics to Excellence

In a world where efficiency and effectiveness are more than just buzzwords, the need for…

8D: Tools and Techniques

Are you grappling with recurring problems in your organization and searching for a structured way…

How to Select the Right Lean Six Sigma Projects: A Comprehensive Guide

Going on a Lean Six Sigma journey is an invigorating experience filled with opportunities for…

How it works

Transform your enterprise with the scalable mindsets, skills, & behavior change that drive performance.

Explore how BetterUp connects to your core business systems.

We pair AI with the latest in human-centered coaching to drive powerful, lasting learning and behavior change.

Build leaders that accelerate team performance and engagement.

Unlock performance potential at scale with AI-powered curated growth journeys.

Build resilience, well-being and agility to drive performance across your entire enterprise.

Transform your business, starting with your sales leaders.

Unlock business impact from the top with executive coaching.

Foster a culture of inclusion and belonging.

Accelerate the performance and potential of your agencies and employees.

See how innovative organizations use BetterUp to build a thriving workforce.

Discover how BetterUp measurably impacts key business outcomes for organizations like yours.

A demo is the first step to transforming your business. Meet with us to develop a plan for attaining your goals.

- What is coaching?

Learn how 1:1 coaching works, who its for, and if it's right for you.

Accelerate your personal and professional growth with the expert guidance of a BetterUp Coach.

Types of Coaching

Navigate career transitions, accelerate your professional growth, and achieve your career goals with expert coaching.

Enhance your communication skills for better personal and professional relationships, with tailored coaching that focuses on your needs.

Find balance, resilience, and well-being in all areas of your life with holistic coaching designed to empower you.

Discover your perfect match : Take our 5-minute assessment and let us pair you with one of our top Coaches tailored just for you.

Research, expert insights, and resources to develop courageous leaders within your organization.

Best practices, research, and tools to fuel individual and business growth.

View on-demand BetterUp events and learn about upcoming live discussions.

The latest insights and ideas for building a high-performing workplace.

- BetterUp Briefing

The online magazine that helps you understand tomorrow's workforce trends, today.

Innovative research featured in peer-reviewed journals, press, and more.

Founded in 2022 to deepen the understanding of the intersection of well-being, purpose, and performance

We're on a mission to help everyone live with clarity, purpose, and passion.

Join us and create impactful change.

Read the buzz about BetterUp.

Meet the leadership that's passionate about empowering your workforce.

For Business

For Individuals

10 Problem-solving strategies to turn challenges on their head

Jump to section

What is an example of problem-solving?

What are the 5 steps to problem-solving, 10 effective problem-solving strategies, what skills do efficient problem solvers have, how to improve your problem-solving skills.

Problems come in all shapes and sizes — from workplace conflict to budget cuts.

Creative problem-solving is one of the most in-demand skills in all roles and industries. It can boost an organization’s human capital and give it a competitive edge.

Problem-solving strategies are ways of approaching problems that can help you look beyond the obvious answers and find the best solution to your problem .

Let’s take a look at a five-step problem-solving process and how to combine it with proven problem-solving strategies. This will give you the tools and skills to solve even your most complex problems.

Good problem-solving is an essential part of the decision-making process . To see what a problem-solving process might look like in real life, let’s take a common problem for SaaS brands — decreasing customer churn rates.

To solve this problem, the company must first identify it. In this case, the problem is that the churn rate is too high.

Next, they need to identify the root causes of the problem. This could be anything from their customer service experience to their email marketing campaigns. If there are several problems, they will need a separate problem-solving process for each one.

Let’s say the problem is with email marketing — they’re not nurturing existing customers. Now that they’ve identified the problem, they can start using problem-solving strategies to look for solutions.

This might look like coming up with special offers, discounts, or bonuses for existing customers. They need to find ways to remind them to use their products and services while providing added value. This will encourage customers to keep paying their monthly subscriptions.

They might also want to add incentives, such as access to a premium service at no extra cost after 12 months of membership. They could publish blog posts that help their customers solve common problems and share them as an email newsletter.

The company should set targets and a time frame in which to achieve them. This will allow leaders to measure progress and identify which actions yield the best results.

Perhaps you’ve got a problem you need to tackle. Or maybe you want to be prepared the next time one arises. Either way, it’s a good idea to get familiar with the five steps of problem-solving.

Use this step-by-step problem-solving method with the strategies in the following section to find possible solutions to your problem.

1. Identify the problem

The first step is to know which problem you need to solve. Then, you need to find the root cause of the problem.

The best course of action is to gather as much data as possible, speak to the people involved, and separate facts from opinions.

Once this is done, formulate a statement that describes the problem. Use rational persuasion to make sure your team agrees .

2. Break the problem down

Identifying the problem allows you to see which steps need to be taken to solve it.

First, break the problem down into achievable blocks. Then, use strategic planning to set a time frame in which to solve the problem and establish a timeline for the completion of each stage.

3. Generate potential solutions

At this stage, the aim isn’t to evaluate possible solutions but to generate as many ideas as possible.

Encourage your team to use creative thinking and be patient — the best solution may not be the first or most obvious one.

Use one or more of the different strategies in the following section to help come up with solutions — the more creative, the better.

4. Evaluate the possible solutions

Once you’ve generated potential solutions, narrow them down to a shortlist. Then, evaluate the options on your shortlist.

There are usually many factors to consider. So when evaluating a solution, ask yourself the following questions:

- Will my team be on board with the proposition?

- Does the solution align with organizational goals ?

- Is the solution likely to achieve the desired outcomes?

- Is the solution realistic and possible with current resources and constraints?

- Will the solution solve the problem without causing additional unintended problems?

5. Implement and monitor the solutions

Once you’ve identified your solution and got buy-in from your team, it’s time to implement it.

But the work doesn’t stop there. You need to monitor your solution to see whether it actually solves your problem.

Request regular feedback from the team members involved and have a monitoring and evaluation plan in place to measure progress.

If the solution doesn’t achieve your desired results, start this step-by-step process again.

There are many different ways to approach problem-solving. Each is suitable for different types of problems.

The most appropriate problem-solving techniques will depend on your specific problem. You may need to experiment with several strategies before you find a workable solution.

Here are 10 effective problem-solving strategies for you to try:

- Use a solution that worked before

- Brainstorming

- Work backward

- Use the Kipling method

- Draw the problem

- Use trial and error

- Sleep on it

- Get advice from your peers

- Use the Pareto principle

- Add successful solutions to your toolkit

Let’s break each of these down.

1. Use a solution that worked before

It might seem obvious, but if you’ve faced similar problems in the past, look back to what worked then. See if any of the solutions could apply to your current situation and, if so, replicate them.

2. Brainstorming

The more people you enlist to help solve the problem, the more potential solutions you can come up with.

Use different brainstorming techniques to workshop potential solutions with your team. They’ll likely bring something you haven’t thought of to the table.

3. Work backward

Working backward is a way to reverse engineer your problem. Imagine your problem has been solved, and make that the starting point.

Then, retrace your steps back to where you are now. This can help you see which course of action may be most effective.

4. Use the Kipling method

This is a method that poses six questions based on Rudyard Kipling’s poem, “ I Keep Six Honest Serving Men .”

- What is the problem?

- Why is the problem important?

- When did the problem arise, and when does it need to be solved?

- How did the problem happen?

- Where is the problem occurring?

- Who does the problem affect?

Answering these questions can help you identify possible solutions.

5. Draw the problem

Sometimes it can be difficult to visualize all the components and moving parts of a problem and its solution. Drawing a diagram can help.

This technique is particularly helpful for solving process-related problems. For example, a product development team might want to decrease the time they take to fix bugs and create new iterations. Drawing the processes involved can help you see where improvements can be made.

6. Use trial-and-error

A trial-and-error approach can be useful when you have several possible solutions and want to test them to see which one works best.

7. Sleep on it

Finding the best solution to a problem is a process. Remember to take breaks and get enough rest . Sometimes, a walk around the block can bring inspiration, but you should sleep on it if possible.

A good night’s sleep helps us find creative solutions to problems. This is because when you sleep, your brain sorts through the day’s events and stores them as memories. This enables you to process your ideas at a subconscious level.

If possible, give yourself a few days to develop and analyze possible solutions. You may find you have greater clarity after sleeping on it. Your mind will also be fresh, so you’ll be able to make better decisions.

8. Get advice from your peers

Getting input from a group of people can help you find solutions you may not have thought of on your own.

For solo entrepreneurs or freelancers, this might look like hiring a coach or mentor or joining a mastermind group.

For leaders , it might be consulting other members of the leadership team or working with a business coach .

It’s important to recognize you might not have all the skills, experience, or knowledge necessary to find a solution alone.

9. Use the Pareto principle

The Pareto principle — also known as the 80/20 rule — can help you identify possible root causes and potential solutions for your problems.

Although it’s not a mathematical law, it’s a principle found throughout many aspects of business and life. For example, 20% of the sales reps in a company might close 80% of the sales.

You may be able to narrow down the causes of your problem by applying the Pareto principle. This can also help you identify the most appropriate solutions.

10. Add successful solutions to your toolkit

Every situation is different, and the same solutions might not always work. But by keeping a record of successful problem-solving strategies, you can build up a solutions toolkit.

These solutions may be applicable to future problems. Even if not, they may save you some of the time and work needed to come up with a new solution.

Improving problem-solving skills is essential for professional development — both yours and your team’s. Here are some of the key skills of effective problem solvers:

- Critical thinking and analytical skills

- Communication skills , including active listening

- Decision-making

- Planning and prioritization

- Emotional intelligence , including empathy and emotional regulation

- Time management

- Data analysis

- Research skills

- Project management

And they see problems as opportunities. Everyone is born with problem-solving skills. But accessing these abilities depends on how we view problems. Effective problem-solvers see problems as opportunities to learn and improve.

Ready to work on your problem-solving abilities? Get started with these seven tips.

1. Build your problem-solving skills

One of the best ways to improve your problem-solving skills is to learn from experts. Consider enrolling in organizational training , shadowing a mentor , or working with a coach .

2. Practice

Practice using your new problem-solving skills by applying them to smaller problems you might encounter in your daily life.

Alternatively, imagine problematic scenarios that might arise at work and use problem-solving strategies to find hypothetical solutions.

3. Don’t try to find a solution right away

Often, the first solution you think of to solve a problem isn’t the most appropriate or effective.

Instead of thinking on the spot, give yourself time and use one or more of the problem-solving strategies above to activate your creative thinking.

4. Ask for feedback

Receiving feedback is always important for learning and growth. Your perception of your problem-solving skills may be different from that of your colleagues. They can provide insights that help you improve.

5. Learn new approaches and methodologies

There are entire books written about problem-solving methodologies if you want to take a deep dive into the subject.

We recommend starting with “ Fixed — How to Perfect the Fine Art of Problem Solving ” by Amy E. Herman.

6. Experiment

Tried-and-tested problem-solving techniques can be useful. However, they don’t teach you how to innovate and develop your own problem-solving approaches.

Sometimes, an unconventional approach can lead to the development of a brilliant new idea or strategy. So don’t be afraid to suggest your most “out there” ideas.

7. Analyze the success of your competitors

Do you have competitors who have already solved the problem you’re facing? Look at what they did, and work backward to solve your own problem.

For example, Netflix started in the 1990s as a DVD mail-rental company. Its main competitor at the time was Blockbuster.

But when streaming became the norm in the early 2000s, both companies faced a crisis. Netflix innovated, unveiling its streaming service in 2007.

If Blockbuster had followed Netflix’s example, it might have survived. Instead, it declared bankruptcy in 2010.

Use problem-solving strategies to uplevel your business

When facing a problem, it’s worth taking the time to find the right solution.

Otherwise, we risk either running away from our problems or headlong into solutions. When we do this, we might miss out on other, better options.

Use the problem-solving strategies outlined above to find innovative solutions to your business’ most perplexing problems.

If you’re ready to take problem-solving to the next level, request a demo with BetterUp . Our expert coaches specialize in helping teams develop and implement strategies that work.

Boost your productivity

Maximize your time and productivity with strategies from our expert coaches.

Elizabeth Perry, ACC

Elizabeth Perry is a Coach Community Manager at BetterUp. She uses strategic engagement strategies to cultivate a learning community across a global network of Coaches through in-person and virtual experiences, technology-enabled platforms, and strategic coaching industry partnerships. With over 3 years of coaching experience and a certification in transformative leadership and life coaching from Sofia University, Elizabeth leverages transpersonal psychology expertise to help coaches and clients gain awareness of their behavioral and thought patterns, discover their purpose and passions, and elevate their potential. She is a lifelong student of psychology, personal growth, and human potential as well as an ICF-certified ACC transpersonal life and leadership Coach.

8 creative solutions to your most challenging problems

5 problem-solving questions to prepare you for your next interview, what are metacognitive skills examples in everyday life, 31 examples of problem solving performance review phrases, what is lateral thinking 7 techniques to encourage creative ideas, leadership activities that encourage employee engagement, learn what process mapping is and how to create one (+ examples), how much do distractions cost 8 effects of lack of focus, can dreams help you solve problems 6 ways to try, similar articles, the pareto principle: how the 80/20 rule can help you do more with less, thinking outside the box: 8 ways to become a creative problem solver, experimentation brings innovation: create an experimental workplace, 3 problem statement examples and steps to write your own, contingency planning: 4 steps to prepare for the unexpected, stay connected with betterup, get our newsletter, event invites, plus product insights and research..

3100 E 5th Street, Suite 350 Austin, TX 78702

- Platform Overview

- Integrations

- Powered by AI

- BetterUp Lead

- BetterUp Manage™

- BetterUp Care™

- Sales Performance

- Diversity & Inclusion

- Case Studies

- Why BetterUp?

- About Coaching

- Find your Coach

- Career Coaching

- Communication Coaching

- Life Coaching

- News and Press

- Leadership Team

- Become a BetterUp Coach

- BetterUp Labs

- Center for Purpose & Performance

- Leadership Training

- Business Coaching

- Contact Support

- Contact Sales

- Privacy Policy

- Acceptable Use Policy

- Trust & Security

- Cookie Preferences

35 problem-solving techniques and methods for solving complex problems

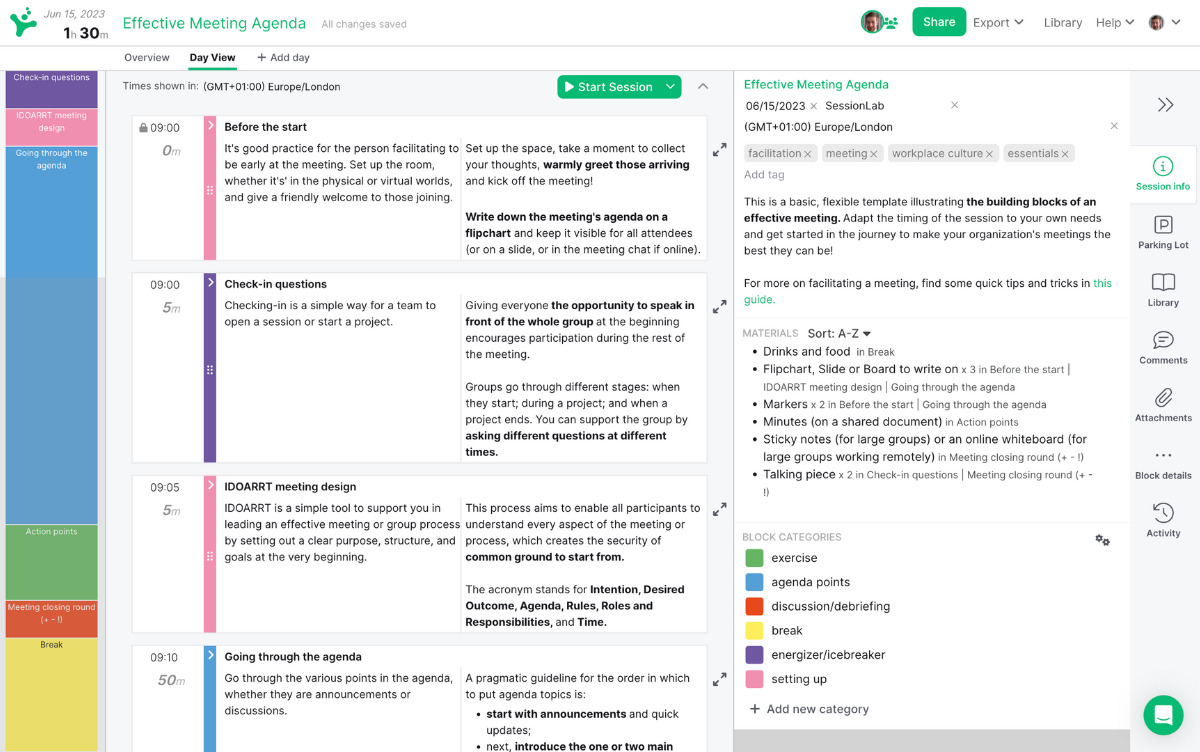

Design your next session with SessionLab

Join the 150,000+ facilitators using SessionLab.

Recommended Articles

A step-by-step guide to planning a workshop, how to create an unforgettable training session in 8 simple steps, 47 useful online tools for workshop planning and meeting facilitation.

All teams and organizations encounter challenges as they grow. There are problems that might occur for teams when it comes to miscommunication or resolving business-critical issues . You may face challenges around growth , design , user engagement, and even team culture and happiness. In short, problem-solving techniques should be part of every team’s skillset.

Problem-solving methods are primarily designed to help a group or team through a process of first identifying problems and challenges , ideating possible solutions , and then evaluating the most suitable .

Finding effective solutions to complex problems isn’t easy, but by using the right process and techniques, you can help your team be more efficient in the process.

So how do you develop strategies that are engaging, and empower your team to solve problems effectively?

In this blog post, we share a series of problem-solving tools you can use in your next workshop or team meeting. You’ll also find some tips for facilitating the process and how to enable others to solve complex problems.

Let’s get started!

How do you identify problems?

How do you identify the right solution.

- Tips for more effective problem-solving

Complete problem-solving methods

- Problem-solving techniques to identify and analyze problems

- Problem-solving techniques for developing solutions

Problem-solving warm-up activities

Closing activities for a problem-solving process.

Before you can move towards finding the right solution for a given problem, you first need to identify and define the problem you wish to solve.

Here, you want to clearly articulate what the problem is and allow your group to do the same. Remember that everyone in a group is likely to have differing perspectives and alignment is necessary in order to help the group move forward.

Identifying a problem accurately also requires that all members of a group are able to contribute their views in an open and safe manner. It can be scary for people to stand up and contribute, especially if the problems or challenges are emotive or personal in nature. Be sure to try and create a psychologically safe space for these kinds of discussions.

Remember that problem analysis and further discussion are also important. Not taking the time to fully analyze and discuss a challenge can result in the development of solutions that are not fit for purpose or do not address the underlying issue.

Successfully identifying and then analyzing a problem means facilitating a group through activities designed to help them clearly and honestly articulate their thoughts and produce usable insight.

With this data, you might then produce a problem statement that clearly describes the problem you wish to be addressed and also state the goal of any process you undertake to tackle this issue.

Finding solutions is the end goal of any process. Complex organizational challenges can only be solved with an appropriate solution but discovering them requires using the right problem-solving tool.

After you’ve explored a problem and discussed ideas, you need to help a team discuss and choose the right solution. Consensus tools and methods such as those below help a group explore possible solutions before then voting for the best. They’re a great way to tap into the collective intelligence of the group for great results!

Remember that the process is often iterative. Great problem solvers often roadtest a viable solution in a measured way to see what works too. While you might not get the right solution on your first try, the methods below help teams land on the most likely to succeed solution while also holding space for improvement.

Every effective problem solving process begins with an agenda . A well-structured workshop is one of the best methods for successfully guiding a group from exploring a problem to implementing a solution.

In SessionLab, it’s easy to go from an idea to a complete agenda . Start by dragging and dropping your core problem solving activities into place . Add timings, breaks and necessary materials before sharing your agenda with your colleagues.

The resulting agenda will be your guide to an effective and productive problem solving session that will also help you stay organized on the day!

Tips for more effective problem solving

Problem-solving activities are only one part of the puzzle. While a great method can help unlock your team’s ability to solve problems, without a thoughtful approach and strong facilitation the solutions may not be fit for purpose.

Let’s take a look at some problem-solving tips you can apply to any process to help it be a success!

Clearly define the problem

Jumping straight to solutions can be tempting, though without first clearly articulating a problem, the solution might not be the right one. Many of the problem-solving activities below include sections where the problem is explored and clearly defined before moving on.

This is a vital part of the problem-solving process and taking the time to fully define an issue can save time and effort later. A clear definition helps identify irrelevant information and it also ensures that your team sets off on the right track.

Don’t jump to conclusions

It’s easy for groups to exhibit cognitive bias or have preconceived ideas about both problems and potential solutions. Be sure to back up any problem statements or potential solutions with facts, research, and adequate forethought.

The best techniques ask participants to be methodical and challenge preconceived notions. Make sure you give the group enough time and space to collect relevant information and consider the problem in a new way. By approaching the process with a clear, rational mindset, you’ll often find that better solutions are more forthcoming.

Try different approaches

Problems come in all shapes and sizes and so too should the methods you use to solve them. If you find that one approach isn’t yielding results and your team isn’t finding different solutions, try mixing it up. You’ll be surprised at how using a new creative activity can unblock your team and generate great solutions.

Don’t take it personally

Depending on the nature of your team or organizational problems, it’s easy for conversations to get heated. While it’s good for participants to be engaged in the discussions, ensure that emotions don’t run too high and that blame isn’t thrown around while finding solutions.

You’re all in it together, and even if your team or area is seeing problems, that isn’t necessarily a disparagement of you personally. Using facilitation skills to manage group dynamics is one effective method of helping conversations be more constructive.

Get the right people in the room

Your problem-solving method is often only as effective as the group using it. Getting the right people on the job and managing the number of people present is important too!

If the group is too small, you may not get enough different perspectives to effectively solve a problem. If the group is too large, you can go round and round during the ideation stages.

Creating the right group makeup is also important in ensuring you have the necessary expertise and skillset to both identify and follow up on potential solutions. Carefully consider who to include at each stage to help ensure your problem-solving method is followed and positioned for success.

Document everything

The best solutions can take refinement, iteration, and reflection to come out. Get into a habit of documenting your process in order to keep all the learnings from the session and to allow ideas to mature and develop. Many of the methods below involve the creation of documents or shared resources. Be sure to keep and share these so everyone can benefit from the work done!

Bring a facilitator

Facilitation is all about making group processes easier. With a subject as potentially emotive and important as problem-solving, having an impartial third party in the form of a facilitator can make all the difference in finding great solutions and keeping the process moving. Consider bringing a facilitator to your problem-solving session to get better results and generate meaningful solutions!

Develop your problem-solving skills

It takes time and practice to be an effective problem solver. While some roles or participants might more naturally gravitate towards problem-solving, it can take development and planning to help everyone create better solutions.

You might develop a training program, run a problem-solving workshop or simply ask your team to practice using the techniques below. Check out our post on problem-solving skills to see how you and your group can develop the right mental process and be more resilient to issues too!

Design a great agenda

Workshops are a great format for solving problems. With the right approach, you can focus a group and help them find the solutions to their own problems. But designing a process can be time-consuming and finding the right activities can be difficult.

Check out our workshop planning guide to level-up your agenda design and start running more effective workshops. Need inspiration? Check out templates designed by expert facilitators to help you kickstart your process!

In this section, we’ll look at in-depth problem-solving methods that provide a complete end-to-end process for developing effective solutions. These will help guide your team from the discovery and definition of a problem through to delivering the right solution.

If you’re looking for an all-encompassing method or problem-solving model, these processes are a great place to start. They’ll ask your team to challenge preconceived ideas and adopt a mindset for solving problems more effectively.

- Six Thinking Hats

- Lightning Decision Jam

- Problem Definition Process

- Discovery & Action Dialogue

Design Sprint 2.0

- Open Space Technology

1. Six Thinking Hats

Individual approaches to solving a problem can be very different based on what team or role an individual holds. It can be easy for existing biases or perspectives to find their way into the mix, or for internal politics to direct a conversation.

Six Thinking Hats is a classic method for identifying the problems that need to be solved and enables your team to consider them from different angles, whether that is by focusing on facts and data, creative solutions, or by considering why a particular solution might not work.