100+ ICMR Research Topics: Unlocking Health Insights

The landscape of healthcare research in India has been significantly shaped by the endeavors of the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR). Established in 1911, the ICMR has played a pivotal role in advancing medical knowledge, informing health policies, and fostering collaborations to address pressing health challenges in the country.

In this blog, we embark on a journey through the corridors of ICMR research topics, shedding light on the council’s current and noteworthy research topics that are contributing to the nation’s health and well-being.

The Role of ICMR in Health Research

Table of Contents

The Indian Council of Medical Research operates as the apex body in India for the formulation, coordination, and promotion of biomedical research. With a mission to nurture and harness the potential of medical research for the benefit of society, ICMR has become a cornerstone in shaping health policies and practices.

By fostering collaborations with researchers and institutions across the nation, ICMR has emerged as a driving force in advancing healthcare knowledge and outcomes.

Understanding ICMR Research Methodology

The success of ICMR’s research lies not only in its expansive scope but also in its rigorous methodology and ethical considerations. ICMR has established guidelines that researchers must adhere to, ensuring that studies funded by the council are not only scientifically sound but also ethically conducted.

This commitment to ethical research practices has been a cornerstone in building public trust and confidence in the findings generated by ICMR-funded studies.

100+ ICMR Research Topics For All Level Students

- Infectious Diseases: Emerging pathogens and control strategies.

- Non-Communicable Diseases (NCDs): Diabetes, cardiovascular research.

- Maternal and Child Health: Strategies for mortality reduction.

- Biomedical Research: Molecular insights into diseases.

- Cancer Research: Innovative approaches for treatment.

- Epidemiology: Studying disease patterns and trends.

- Vaccination Strategies: Enhancing immunization programs.

- Public Health Interventions: Effective community health measures.

- Antibiotic Resistance: Combating microbial resistance.

- Genetic Studies: Understanding genetic contributions to diseases.

- Neurological Disorders: Research on neurological conditions.

- Mental Health: Addressing mental health challenges.

- Nutrition and Health: Studying dietary impacts on health.

- Health Systems Research: Improving healthcare delivery.

- Ayurveda Research: Integrating traditional medicine practices.

- Environmental Health: Impact of environment on health.

- Emerging Technologies: Utilizing tech for healthcare innovations.

- Pharmacological Research: Advancements in drug discovery.

- Global Health Collaborations: International health partnerships.

- Waterborne Diseases: Prevention and control strategies.

- Health Policy Research: Shaping evidence-based policies.

- Health Economics: Studying economic aspects of healthcare.

- Telemedicine: Harnessing technology for remote healthcare.

- Rare Diseases: Understanding and treating rare disorders.

- Community Health: Promoting health at the grassroots level.

- HIV/AIDS Research: Advancements in HIV prevention and treatment.

- Aging and Health: Research on geriatric health issues.

- Cardiovascular Health: Preventive measures and treatments.

- Respiratory Diseases: Understanding lung-related conditions.

- Zoonotic Diseases: Investigating diseases transmitted from animals.

- Stem Cell Research: Applications in regenerative medicine.

- Yoga and Health: Studying the health benefits of yoga.

- Gender and Health: Research on gender-specific health issues.

- Oral Health: Preventive measures and treatments for oral diseases.

- Health Informatics: Utilizing data for healthcare improvements.

- Health Education: Promoting awareness for better health.

- Drug Resistance: Research on antimicrobial resistance.

- Hepatitis Research: Prevention and treatment strategies.

- Telehealth: Remote healthcare services and accessibility.

- Diabetes Management: Strategies for diabetes prevention and control.

- Tuberculosis Research: Advancements in TB diagnosis and treatment.

- Fertility Research: Understanding reproductive health issues.

- Artificial Intelligence in Healthcare: Integrating AI for diagnostics.

- Health Disparities: Addressing inequalities in healthcare access.

- Mental Health Stigma: Research on reducing stigma.

- Mobile Health (mHealth): Applications for mobile-based healthcare.

- Vector-Borne Diseases: Prevention and control measures.

- Nanotechnology in Medicine: Applications in healthcare.

- Occupational Health: Research on workplace health issues.

- Biobanking: Storing and utilizing biological samples for research.

- Telepsychiatry: Providing mental health services remotely.

- Health Equity: Promoting fairness in healthcare delivery.

- Community-Based Participatory Research: Engaging communities in research.

- E-health: Electronic methods for healthcare delivery.

- Sleep Disorders: Understanding and treating sleep-related conditions.

- Health Communication: Effective communication in healthcare.

- Global Burden of Disease: Research on disease prevalence and impact.

- Traditional Medicine: Studying traditional healing practices.

- Nutraceuticals: Research on health-promoting food components.

- Health Data Security: Ensuring privacy and security of health data.

- Regenerative Medicine: Advancements in tissue engineering.

- Social Determinants of Health: Studying social factors affecting health.

- Pharmacovigilance: Monitoring and ensuring drug safety.

- Gerontology: Research on aging and the elderly.

- Mobile Apps in Healthcare: Applications for health monitoring.

- Genetic Counseling: Supporting individuals with genetic conditions.

- Community Health Workers: Role in improving healthcare access.

- Health Behavior Change: Strategies for promoting healthier habits.

- Palliative Care Research: Enhancing end-of-life care.

- Nanomedicine: Applications of nanotechnology in medicine.

- Climate Change and Health: Impact on public health.

- Health Literacy: Promoting understanding of health information.

- Antibody Therapeutics: Advancements in antibody-based treatments.

- Digital Health Records: Electronic health record systems.

- Microbiome Research: Understanding the role of microorganisms in health.

- Disaster Preparedness: Research on health response during disasters.

- Food Safety and Health: Ensuring safe food consumption.

- Artificial Organs: Advancements in organ transplantation.

- Telepharmacy: Remote pharmaceutical services.

- Environmental Epidemiology: Studying the link between environment and health.

- E-mental Health: Digital tools for mental health support.

- Precision Medicine: Tailoring treatments based on individual characteristics.

- Health Impact Assessment: Evaluating the consequences of policies on health.

- Genome Editing: Applications in modifying genetic material.

- Mobile Clinics: Bringing healthcare to underserved areas.

- Telecardiology: Remote cardiac care services.

- Health Robotics: Utilizing robots in healthcare settings.

- Precision Agriculture and Health: Linking agriculture practices to health outcomes.

- Community-Based Rehabilitation: Supporting rehabilitation at the community level.

- Nanotoxicology: Studying the toxicological effects of nanomaterials.

- Community Mental Health: Strategies for promoting mental well-being.

- Health Financing: Research on funding models for healthcare.

- Augmented Reality in Healthcare: Applications in medical training and diagnostics.

- One Health Approach: Integrating human, animal, and environmental health.

- Disaster Mental Health: Addressing mental health issues after disasters.

- Mobile Laboratory Units: Rapid response in disease outbreaks.

- Health Impact Investing: Investing for positive health outcomes.

- Rehabilitation Robotics: Assisting in physical therapy.

- Human Microbiota: Understanding the microorganisms living in and on the human body.

- 3D Printing in Medicine: Applications in medical device manufacturing.

Success Stories from ICMR-Funded Research

Highlighting the impact of ICMR-funded research is essential in appreciating the council’s contribution to healthcare in India. From breakthrough discoveries to successful interventions, ICMR-supported studies have led to tangible improvements in health outcomes.

Case studies showcasing the journey from ICMR research topics and findings to real-world applications serve as inspiring examples of how scientific knowledge can translate into positive societal impacts.

Challenges and Opportunities in ICMR Research

While ICMR has achieved remarkable success in advancing health research, it is not without its challenges. Researchers face obstacles in conducting studies, ranging from resource constraints to logistical issues.

Acknowledging these challenges is crucial in finding solutions and optimizing the impact of ICMR-funded research. Additionally, there are opportunities for collaboration, both nationally and internationally, that can further enrich the research landscape and accelerate progress in addressing health challenges.

The Future of Health Research in India: ICMR’s Vision

Looking ahead, ICMR envisions a future where health research continues to play a central role in shaping the well-being of the nation. Strategic goals include harnessing the power of technology and innovation to drive research advancements, fostering interdisciplinary collaborations, and addressing emerging health challenges.

The vision extends beyond the laboratory, emphasizing the translation of research findings into practical solutions that can positively impact the lives of individuals and communities across India.

In conclusion, the Indian Council of Medical Research stands as a beacon in the realm of healthcare research, tirelessly working towards advancements that contribute to the well-being of the nation.

By exploring ICMR research topics, understanding its methodology, and reflecting on success stories, we gain insight into the transformative power of scientific inquiry.

As ICMR continues to forge ahead, the future of health research in India looks promising, guided by a vision of innovation, collaboration, and a steadfast commitment to improving the health of all citizens.

Related Posts

Step by Step Guide on The Best Way to Finance Car

The Best Way on How to Get Fund For Business to Grow it Efficiently

- Member Types & Privileges

- Registration

- INFORMER Logo

- Office Bearers

- Our history

- Vision Mission & Values

- Blog@Third I

Quick Links

Subscribe to our Mailing List

- Request new password

Error message

- Deprecated function : Return type of DatabaseStatementBase::execute($args = [], $options = []) should either be compatible with PDOStatement::execute(?array $params = null): bool, or the #[\ReturnTypeWillChange] attribute should be used to temporarily suppress the notice in require_once() (line 2244 of /home2/inforyjm/public_html/includes/database/database.inc ).

- Deprecated function : Return type of DatabaseStatementEmpty::current() should either be compatible with Iterator::current(): mixed, or the #[\ReturnTypeWillChange] attribute should be used to temporarily suppress the notice in require_once() (line 2346 of /home2/inforyjm/public_html/includes/database/database.inc ).

- Deprecated function : Return type of DatabaseStatementEmpty::next() should either be compatible with Iterator::next(): void, or the #[\ReturnTypeWillChange] attribute should be used to temporarily suppress the notice in require_once() (line 2346 of /home2/inforyjm/public_html/includes/database/database.inc ).

- Deprecated function : Return type of DatabaseStatementEmpty::key() should either be compatible with Iterator::key(): mixed, or the #[\ReturnTypeWillChange] attribute should be used to temporarily suppress the notice in require_once() (line 2346 of /home2/inforyjm/public_html/includes/database/database.inc ).

- Deprecated function : Return type of DatabaseStatementEmpty::valid() should either be compatible with Iterator::valid(): bool, or the #[\ReturnTypeWillChange] attribute should be used to temporarily suppress the notice in require_once() (line 2346 of /home2/inforyjm/public_html/includes/database/database.inc ).

- Deprecated function : Return type of DatabaseStatementEmpty::rewind() should either be compatible with Iterator::rewind(): void, or the #[\ReturnTypeWillChange] attribute should be used to temporarily suppress the notice in require_once() (line 2346 of /home2/inforyjm/public_html/includes/database/database.inc ).

WHO ARE WE?

India is a country which contains hundreds of medical colleges and thousands of medical students graduating each year. A fair number of students actively involve themselves in research at a local or national or even international level. INFORMER, The Forum for Medical Students' Research, India is a step towards bringing those interested in research to a common platform.

INFORMER is an all India medical students' body aimed at advocacy and promotion of research amongst undergraduate medical students and to encourage them to present their research work at a national level by means of the annual conference organized by the forum. It is an institution comprising of a group of medical students who attempt to keep the spirit of research alive among the student community. INFORMER was formed in 2009 in response to there being a lack of an advocate for undergraduate medical students in the country. Over the past 3 years, we have diversified base of activities which now include our annual flagship conference (Medicon), an online journal club,collaborative research projects, a research project mentoring forum, workshops which promote evidence-based medicine,medical quizzes, case presentation conferences etc.

Recent Updates

Topic: Medical Research in India Past and Future

We are as young as our faith and old as our doubts. APJ Abdul Kalam

Write an essay on the topic in less than 1500 words and win cash prizes. 1st Prize- Rs.10000/-, 2nd Prize- Rs.7000/-, 3rd Prize-Rs.5000/-

Instructions:

-BMJ India has teamed up with Fortis C-DOC Center of Excellence for Diabetes, Metabolic Diseases & Endocrinology, New Delhi to provide educational support for health professionals to improve care for people with diabetes in India. Learn more about their course and how to sign up.-

Greetings from the 50th year council of Chengalpattu Medical college, Chengalpattu, Tamil Nadu. www. www.chemfest.in/charm.html

We, the students of this famed institution take immense pleasure in introducing to you our annual academic extravaganza – the 3rd CHARM-CHengalpattu Academic and Research Meet, to be conducted at our college premises, in September 2015

Abstract submission deadlines for Medicon 2015 have been extended to 30 June 2015. This is owing to certain colleges having examinations around the previous deadline. Hope you will be able to complete abstract submission within that time.

The wait is over ... Call for ICMR STS 2015 is out

Read all updates

Call for papers - Medical education in India

Guest Editors: Anne D. Souza: Manipal Academy of Higher Education, India Olwyn Westwood: King’s College London, UK

Submission Status: Open | Submission Deadline: 7 August 2024

Articles will undergo the journal’s standard peer-review process and are subject to all of the journal’s standard policies . Articles will be added to the Collection as they are published.

The Editors have no competing interests with the submissions which they handle through the peer review process. The peer review of any submissions for which the Editors have competing interests is handled by another Editorial Board Member who has no competing interests.

- Open access

- Published: 24 August 2021

Psychological well-being and burnout amongst medical students in India: a report from a nationally accessible survey

- Sharad Philip ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-8028-3378 1 ,

- Andrew Molodynski 2 , 3 ,

- Lauren Barklie 2 ,

- Dinesh Bhugra 4 &

- Santosh K. Chaturvedi 1

Middle East Current Psychiatry volume 28 , Article number: 54 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

5671 Accesses

9 Citations

Metrics details

Medical students in India face multiple challenges and sources of stress during their training. No nationally representative survey has yet been undertaken. We undertook a cross-sectional national survey to assess substance use, psychological well-being, and burnout using CAGE, Oldenburg Burnout Inventory (OLBI), and the short General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-12). The survey was open to all medical students in India. Descriptive statistics along with chi square tests and Spearman’s correlation were performed.

Burnout was reported by 86% of respondents for disengagement and 80% for exhaustion. Seventy percent had a score of more than 2 on the GHQ-12, indicating caseness.

Conclusions

This study reveals that medical students are going through exceptional stress when compared to their age-matched peers. More nationally representative studies must be conducted on a large scale to quantify the problem and to help design new interventions.

The rigours of medical education are well-known internationally, and medical students’ mental health morbidity is higher than that of their aged-matched peers [ 1 ]. Medical students are prone to anxiety, depressive disorders, and high levels of psychological distress [ 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 ]. Such issues may progress to negatively impact academic performance, predispose to substance use, and/or encourage other maladaptive coping strategies [ 4 , 8 , 9 ]. Increased distress can also increase academic dishonesty [ 10 ].

‘Burnout’ was first outlined by Freudenberger in 1974 [ 11 ], and ‘International Classification of Diseases-11 (ICD-11)’ recognises it as an occupational phenomenon in all workplace environments. Initially described as including reduced personal accomplishment, depersonalization, and emotional exhaustion, it is considered to be a health issue arising in the context of poorly managed workplace stress. It is comprised of three dimensions—energy depletion, reduced professional efficacy, and feelings of negativism or cynicism towards one’s job [ 12 ]. Burnout is directly related to increased psychological distress and unmitigated mental health issues in an apathetic environment. It has been shown to impact up to 40% of practicing doctors [ 13 , 14 ].

In 2019, 1.41 million students attempted the Indian medical school entrance exam; 797,000 passed and only 75,000 were selected. The course lasts over 5 years and is academically and personally demanding. Many undertake medical studies due to parental pressure rather than personal interest [ 15 ], potentially causing disillusionment and limiting help seeking.

India is home to the world’s largest population of people aged 10–24 years, and suicide is their leading cause of death [ 16 , 17 ]. ‘Academic trauma’ has been documented as a contributor to student suicide in a news report of nearly 10,000 students committing suicide in 1 year [ 18 ]. Separate data for medical students is however unavailable.

Several cross-sectional studies have examined the stress and overall well-being of Indian medical students by using various questionnaires. One study [ 19 ] using the Oldenburg Burnout Inventory and GHQ 12 reported high levels of burnout (88% and 81% for disengagement and exhaustion respectively) and high levels of mental health problems (62% with GHQ score >2). Two studies [ 20 , 21 ] using the Oldenburg Burnout Inventory have reported mean scores in Indian medical students, disengagement scores of 2.43 [ 20 ] and 18.16 [ 21 ], and exhaustion scores of 2.32 [ 20 ] and 13.89 [ 21 ] respectively. A different study [ 22 ] used the Maslach Burnout Inventory and reported 71% of the students showed moderate to high levels of burnout. Bute et al. [ 23 ] reported high levels of caseness indicating need for evaluation (66% with scores more than 4) amongst Indian medical students using the GHQ 28. Another study [ 24 ] using the same scale reported a mean score of above 7. Many other studies have examined the psychological well-being and mental health of Indian medical students [ 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 ]. The variety of instruments and scales used and methodological variations have resulted in a wide range of results. All studies were limited to students within a few medical colleges. There have yet been no nationally representative robust studies. Our study reports a nationally accessible large-scale survey on the well-being of medical students in India.

We conducted an online survey amongst medical student communities in India as part of a larger international effort to understand the stresses of medical student life. Matching surveys have been undertaken in countries such as Brazil [ 30 ], Morocco [ 31 ], and Jordan [ 32 ]. A similar study was also undertaken in four medical colleges of eastern and southern India [ 19 ].

This cross-sectional survey was conducted over the ‘Type Form’ platform, which presents survey questions sequentially and records respondent data. These data are collected and displayed graphically for each question. The survey link was disseminated to multiple medical student groups. A message accompanied the link to introduce the survey and its’ aims and to assure confidentiality and anonymity. Participant consent was sought in the beginning of the survey. The link was launched along with the message over multiple medical student groups across many colleges, predominantly by reaching out to student leadership and WhatsApp chat groups. The survey was open from 09/02/20 until 31/08/20. Fortnightly reminders were sent. As the circulation increased, a medical student magazine ‘Lexicon’ picked up the survey link and promoted it.

Survey questions included basic demographic details such as year of study, level of parental education, hours of work outside of student activities, current and past mental health difficulties, prescribed medications, and basic details of substance use. The short version of the ‘General Health Questionnaire’ (GHQ-12) [ 33 , 34 ] was included to screen for minor psychiatric disorders, with a score of 2 or more indicating caseness. The GHQ-12 has been used previously in Indian populations [ 35 ]. The CAGE questionnaire [ 36 ] was included to measure alcohol use with a score of more than 2, considered as ‘CAGE positive’. Lastly, the Oldenberg Burden Inventory [ 37 ] was included to identify burnout with threshold scores of 2.10 for disengagement and 2.25 for exhaustion [ 38 ].

Three hundred and forty-four respondents completed the survey. Of these respondents, three were removed as they were not medical students. There were respondents from New Delhi, Pondicherry, Vellore, Ludhiana, Bellary, and Bangalore amongst other sites.

Responses were spread across the training years as follows: 15% in the first year, 22% from the second year, 20% from year three, 12% from year four, 10% from year five, and 19% from year six. Two percent did not specify year of training.

Sixty percent of respondents identified as female, 39% identified as male, and one respondent identified as other gender.

Parental education levels for 46% were post-graduation; 35% were undergraduate degrees, while 13% were up to high school education.

Fifteen percent of respondents reported working for more than 20 h weekly. The majority of respondents (79%) did not work. Details of the sociodemographic details are presented in Tables 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , and 5 .

Mental health

Before commencing their medical education, 27 respondents (8%) consulted a mental health professional, and five (2%) were given a mental health diagnosis. Diagnoses included mood disorder, anxiety disorder, adjustment disorder, and obsessive-compulsive disorder. Four respondents reported attention deficit hyperactive disorders. Seventeen (5%) students were on psychotropics. Twelve did not provide details, four (1%) were prescribed antidepressants, and one (0.3%) was prescribed benzodiazepines.

Thirty-six (11%) students reported that they were seeing a mental health professional at the time of the survey. Conditions reported included mood disorder, anxiety disorder, stress-related disorder, and obsessive-compulsive disorder. Twenty-four (7%) respondents reported being on prescription medications for their mental health. Nineteen (5%) were on antidepressants, three (1%) were on mood stabilisers, four (1%) were on sedatives, two (1%) were on antipsychotics, and one (0.3%) was on beta blocker. Twelve (4%) reported being prescribed stimulants for ADHD/ADD.

Two hundred and thirty-nine respondents (70%) reported academic work as a source of stress. One hundred and eighty (52%) respondents reported stress from relationships; eighty-eight (26%) reported stress due to financial reasons. Most respondents reported multiple stressors.

CAGE and substance use

Forty-nine (14%) respondents were CAGE positive. Thirty-three (10%) reported using a nonprescription substance to modify their mood to feel better. These nonprescription medications included sedatives, 13 respondents (4%); stimulants, six respondents (2%); antidepressants, five respondents (1%); and over the counter medications, three respondents (1%).

Forty (12%) students reported using cannabis, and five (1%) reported using hallucinogens. Nineteen (6%) of the respondents had used substances to enhance academic performance.

Fifteen (4%) respondents reported that someone close to them was worried about their substance use, and twenty-four (7%) reported being concerned about their own substance use.

GHQ-12 and OLBI score

The mean score of our sample was 5.26, and two hundred and thirty-nine (70%) respondents scored more than 2 in GHQ-12. The mean score for the group on the OLBI scale was 2.6. Two hundred and ninety-four (86%) of the respondents met the disengagement criteria for the OLBI scale while two hundred and seventy-five (80%) met criteria for exhaustion.

Comparisons before training and during training

Twenty-six (8%) respondents reported having had consultations with general practitioners and mental health professionals during the training. Eighteen (5%) of those who responded had only consulted before training and did not do so during their training.

Thirty-seven (11%) respondents reported being diagnosed with a mental health condition after the commencement of their medical training while only two (0.6%) reported being diagnosed in the past but not currently diagnosed. Four (1%) respondents were diagnosed in the past and continued with the diagnosis.

Association of sociodemographic factors with GHQ and OLBI scores

GHQ scores indicating ‘caseness’ were significantly associated with the first and sixth year of medical training. Higher GHQ scores were also reported for higher parental education levels ( p <0.05). We found an association between GHQ scores greater than two and a higher number of reported stressors ( p <0.05) (Ref. Table 1 ).

Disengagement and exhaustion were significantly associated ( p <0.05) with increasing number of stressors (Ref. Table 5 ).

Correlation of GHQ, OLBI, and CAGE scores

GHQ scores were positively correlated with the disengagement domain (correlation coefficient 0.511) and the exhaustion domain (correlation coefficient 0.521) of the OLBI scores. CAGE scores also positively correlated with the GHQ scores (correlation coefficient 0.136).

This was the first nationally accessible survey of medical student well-being in India. A previous study [ 19 ] used the same methods but was conducted in selected medical colleges. We used innovative approaches to recruit respondents. Our survey found that medical students were at greater risk of developing mental ill health than their age-matched peers. Further, it appears that medical training increases mental health morbidity. Only 2% of the respondents had a diagnosis prior to commencing their training while 12% reported being diagnosed after entering medical college. This is a sizeable increase meriting further research to identify aggravating and protective factors. An identical survey carried out a year ago reported that 10% of respondents had received a mental ill health diagnosis prior to entering medical school and that 15% did during medical school [ 19 ]. Rates in the overall literature vary, and this will at least in part be due to sampling and the use of different measures.

From the survey on types and number of stressors, analysis was done looking for associations between the scale measures and stressors. Statistically significant results were obtained regarding increased mental health disturbances and the number of stressors.

There appears to be an association between duration of medical training and mental health issues. It can be understood that many stressors are likely to have greater impacts during the first year and the last year of medical training. The former period is one of great change and uncertainty while the latter period is one of exam pressure and expectations. These periods should be the focus of support systems and measures.

This study demonstrates the need to optimise well-being and to decrease burnout in medical students, which is now known beyond doubt to be increasing amongst physicians throughout their careers [ 39 ]. We need to urgently develop initiatives to minimise morbidity and maximise an individual’s well-being and medical career. Some suggestions are listed below:

Emphasising the importance of well-being both in and away from the workplace

Increasing the amount of targeted support around mental health from medicaleducators/institutions

Stigma reduction and attitude changes that will allow a positive platform on which well-being and mental health optimization and/or treatment can be accessed

Based on the findings from Singh et al. [ 22 ], we endorse co-curricular activities to promote cohesion and development of secondary and tertiary support systems in the colleges. Yoga and meditation activities conducted in group formats may also be beneficial [ 40 ]. Emphasis on physical activity and sleep hygiene should be retained. Online social networks can complement existing more traditional ones. Robust peer mentoring systems and the training of faculty members may aid in surveillance and early detection of mental health issues. This may subsequently reduce morbidity for those affected and reduce dropout rates. Mental health promotion activities should also be a focus of student welfare activities.

Limitations

This study is a cross-sectional survey of a convenience sample available only in English. However, English is the medium of instruction during medical training in India. The questions used were easily understood English.

Implications

Findings from this study highlight high levels of burnout and psychological distress being experience by medical students in India. Mental health morbidity appears to increase in medical training. Further research is warranted to assess mental health morbidity and its’ contributing and mitigating factors amongst students pursuing professional and non-professional disciplines in India.

Medical students in India report high levels of psychological distress and burnout. Urgent attention and interventions are required from peers, teachers, and policy makers.

Availability of data and materials

Abbreviations.

Attention deficit hyperactive disorders/attention deficit disorder

General Health Questionnaire

International Classification of Diseases-11

Oldenburg Burnout Inventory

Moir F et al (2018) Depression in medical students: current insights. Adv Med Education Pract 9:323–333

Article Google Scholar

Sherina MS, Rampal L, Kaneson N (2004) Psychological stress among undergraduate medical students. Med J Malays 59(2):2017–2011

Google Scholar

Supe AN (1998) A study of stress in medical students at Seth G.S. Medical College. J Postgrad Med 44(1):1

CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Stewart SM et al (1999) A prospective analysis of stress and academic performance in the first two years of medical school. Med Educ 33(4):243–250

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Saipanish R (2003) Stress among medical students in a Thai medical school. Med Teach 25(5):502–506

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Dyrbye LN, Thomas MR, Shanafelt TD (2006) Systematic review of depression, anxiety, and other indicators of psychological distress among U.S. and Canadian medical students. Acad Med:354–373

Dyrbye LN et al (2008) Burnout and suicidal ideation among U.S. medical students. Ann Intern Med 149(5):334–341. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-149-5-200809020-00008

Ashton CH, Kamali F (1995) Personality, lifestyles, alcohol and drug consumption in a sample of British medical students. Med Educ 29(3):187–192

Newbury-Birch D, Walshaw D, Kamali F (2001) Drink and drugs: from medical students to doctors. Drug Alcohol Depend 64(3):265–270

Rennie SC, Rudland JR (2003) Differences in medical students’ attitudes to academic misconduct and reported behaviour across the years - a questionnaire study. J Med Ethics 29(2):97–102. https://doi.org/10.1136/jme.29.2.97

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Freudenberger HJ (1974) Staff burn-out. J Soc Issues 30(1):159–165

World Health Organisation. Burn-out an “occupational phenomenon.”: International Classification of Diseases. International Classification of Disease. 2019.

Henderson G (1984) Physician burnout. Hospital Physician 20(10):8–9

Langade D et al (2016) Burnout syndrome among medical practitioners across India: a questionnaire-based survey. Cureus 8:9

Jothula KY et al (2018) Study to find out reasons for opting medical profession and regret after joining MBBS course among first year students of a medical college in Telangana. Int J Community Med Public Health 5(4):1392–1396

UNFPA India | Young people (no date). (). Available at: https://india.unfpa.org/en/topics/young-people-12 .

Dandona R et al (2018) Gender differentials and state variations in suicide deaths in India: the Global Burden of Disease Study 1990–2016. Lancet Public Health 3(10):e478–e489

Student suicides rising, 28 lives lost every day - the Hindu (no date). (Accessed: 12 Nov 2020). Available at: https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/student-suicides-rising-28-lives-lost-every-day/article30685085.ece

Farrell SM et al (2019) Wellbeing and burnout in medical students in India; a large scale survey. Int Rev Psychiatry 31(7–8):555–562

Shad R, Thawani R, Goel A (2015) Burnout and sleep quality: a cross-sectional questionnaire-based study of medical and non-medical students in India. 7(10):e361

Goel A et al (2016) Longitudinal assessment of depression, stress, and burnout in medical students. J Neurosciences Rural Practice 7(4):493–498

Singh S et al (2016) A cross-sectional assessment of stress, coping, and burnout in the final-year medical undergraduate students. Ind Psychiatry J 25(2):179

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Bute J et al (2016) A cross-sectional study of mental well-being among undergraduate students in a Medical College, in Central India. Int J Med Science Public Health 5(9):1775

Nandi M et al (2012) Stress and its risk factors in medical students: an observational study from a medical college in India. Indian J Med Sci 66(1–2):1–12

Jena S, Tiwari C (2015) Stress and mental health problems in 1st year medical students: a survey of two medical colleges in Kanpur, India. Int J Res Med Sci 3(1):130–134

Venkatarao E, Iqbal S, Gupta S (2015) Stress, anxiety; depression among medical undergraduate students; their socio-demographic correlates. Indian J Med Res 141(3):354

Yuvaraj BY, Poornima S, Rashmi S (2016) Screening for overall mental health status using mental health inventory amongst medical students of a government medical college in North Karnataka, India. Int J Community Med Public Health 3(12):3308–3312

Anuradha R et al (2017) Stress and stressors among medical undergraduate students: a cross-sectional study in a private medical college in Tamil Nadu. Indian J Community Med 42(4):222

Garg K, Agarwal M, Dalal PK (2017) Stress among medical students: a cross-sectional study from a North Indian Medical University. Indian J Psychiatry 59(4):502–504

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Castaldelli-Maia JM et al (2019) Stressors, psychological distress, and mental health problems amongst Brazilian medical students. Int Rev Psychiatry 31(7–8):603–607

Lemtiri Chelieh M et al (2019) Mental health and wellbeing among Moroccan medical students: a descriptive study. Int Rev Psychiatry 31(7–8):608–612

Molodynski A et al (2020) Cultural variations in wellbeing, burnout and substance use amongst medical students in twelve countries. Int Rev Psychiatry

Goldberg DP, Blackwell B (1970) Psychiatric illness in general practice: a detailed study using a new method of case identification. Br Med J 2(5707):439–443

Article PubMed Central Google Scholar

Goldberg DP et al (1997) The validity of two versions of the GHQ in the WHO study of mental illness in general health care. Psychol Med 27(1):191–197

Chaturvedi SK et al (1994) Detection of psychiatric morbidity in gynecology patients by two brief screening methods. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol 15(1):53–58

Ewing JA (1984) Detecting alcoholism: the CAGE questionnaire. J Am Med Assoc 252(14):1905–1907

Article CAS Google Scholar

Demerouti E, Bakker AB (2007) Measurement of Burnout (and engagement) measurement of burnout and engagement. the Oldenburg Burnout Inventory: a good alternative to measure burnout (and Engagement)

Westwood S et al (2017) Predictors of emotional exhaustion, disengagement and burnout among improving access to psychological therapies (IAPT) practitioners. J Ment Health 26(2):172–179

Shanafelt TD, Dyrbye LN, West CP (2017) Addressing physician burnout the way forward. J Am Med Assoc:901–902

Ganpat T, Nagendra H (2012) Integrated yoga therapy for improving mental health in managers. Ind Psychiatry J 20(1):45

Download references

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all the people who helped and the many students who took part.

No funding was required for this study.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Psychiatry, NIMHANS, Bangalore, Karnataka, India

Sharad Philip & Santosh K. Chaturvedi

Oxford Health NHS Foundation Trust, Oxford, UK

Andrew Molodynski & Lauren Barklie

Oxford University, Oxford, UK

Andrew Molodynski

King’s College, London, UK

Dinesh Bhugra

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

SP contributed in planning the study, preparing the methodology and questionnaire, analysing the results, preparing the tables, writing the introduction and discussions, and reviewing, revising, and approving the final manuscript. AM contributed in planning the study, preparing the methodology and questionnaire, interpreting the results, writing the introduction and discussions, and reviewing, revising, and approving the final manuscript. LB contributed in preparing the methodology and questionnaire, writing the discussions, and reviewing, revising, and approving the final manuscript. DB contributed in planning the study, preparing the methodology and questionnaire, writing the discussions, and reviewing, revising, and approving the final manuscript. SKC contributed in planning the study, preparing the methodology and questionnaire, analysing the results, preparing the tables, writing the introduction and discussions, and reviewing, revising, and approving the final manuscript. The authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Sharad Philip .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

As per the Indian Council of Medical Research guidelines for online surveys, only participant consent is required. There is no requirement for ethics committee permissions. No ethical approval was deemed necessary by the national algorithm in the UK as this was an online population survey of consenting medical students irrespective of their health status. Only consenting subjects were included. Participant consent was sought in the beginning of the survey.

Consent for publication

The authors have consented to publication.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Philip, S., Molodynski, A., Barklie, L. et al. Psychological well-being and burnout amongst medical students in India: a report from a nationally accessible survey. Middle East Curr Psychiatry 28 , 54 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s43045-021-00129-1

Download citation

Received : 12 July 2021

Accepted : 18 July 2021

Published : 24 August 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s43045-021-00129-1

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Medical students

N. K. P. SALVE INSTITUTE OF MEDICAL SCIENCES & RESEARCH CENTRE

Lata mangeshkar hospital,nagpur.

Ongoing Research Project

Ongoing research project 2023, research projects from anatomy department, research projects from anatomy department 2020 to 2021, research projects from physiology department 2020 to 2021, research projects from biochemistry department 2020 to 2021, research projects from pathology department 2020 to 2021, research projects from forensic medicine department 2020 to 2021, research projects from microbiology department 2020 to 2021, research projects from pharmacology department 2020 to 2021, research projects from community medicine department 2020 - 2021, research projects from otorhinolaryngology department 2020 - 2021, research projects from ophthalmology department 2020 - 2021, research projects from psychiatry department 2020 - 2021, research projects from respiratory medicine department 2020 - 2021, research projects from dermatology, venerology and leprosy department 2020 – 2021, research projects from orthopedic department 2020 - 2021, research projects from general surgery department 2020 - 2021, research projects from anesthesiology department 2020 - 2021, research projects from radio-diagnosis department 2020 - 2021, research projects from general medicine department 2020 - 2021, research projects from obstetrics & gynecology department 2020 - 2021, research projects from paediatric department 2020 - 2021.

- - Google Chrome

Intended for healthcare professionals

- My email alerts

- BMA member login

- Username * Password * Forgot your log in details? Need to activate BMA Member Log In Log in via OpenAthens Log in via your institution

Search form

- Advanced search

- Search responses

- Search blogs

- How to get involved in...

How to get involved in research as a medical student

- Related content

- Peer review

- Anna Kathryn Taylor , final year medical student 1 ,

- Sarah Purdy , professor of primary care and associate dean 1

- 1 Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Bristol, UK

Participating in research gives students great skills and opportunities. Anna Taylor and Sarah Purdy explain how to get started

This article contains:

-How to get involved with research projects

-Questions to ask yourself before starting research

-What can you get published? Research output

-Advice for contacting researchers

-Different types of research explained

-Stages of research projects

Students often go into medicine because of a desire to help others and improve patients’ physical and mental wellbeing. In the early years of medical school, however, it can seem as if you are not making much difference to patient care. Involvement in research can provide exciting opportunities to work as part of a team, improve career prospects, and most importantly add to the evidence base, leading to better outcomes for patients.

Research is usually multidisciplinary, including clinical academics (medical doctors who spend part of their working life doing research), nurses, patients, scientists, and researchers without a medical background. Involvement in such a team can improve your communication skills and expand your understanding of how a multidisciplinary team works.

Participating in research can also help you to develop skills in writing and critical appraisal through the process of publishing your work. You may be able to present your work at conferences—either as a poster or an oral presentation—and this can provide valuable points for job applications at both foundation programme and core training level. This is particularly important if you are considering a career in academia. You will also develop skills in time management, problem solving, and record keeping. You might discover an area of medicine in which you are keen to carry out further work. For some people, getting involved in research as a medical student can be the first step in an academic career.

Kyla Thomas, National Institute for Health Research clinical lecturer in public health at the University of Bristol, says, “my first baby steps into a clinical academic career started with a research project I completed as a medical student. That early involvement in research opened my eyes to a whole new world of opportunities that I never would have considered.

“Importantly, participating in undergraduate research sets students apart from their colleagues. Applying for foundation posts is a competitive process and it is a definite advantage if you have managed to obtain a peer reviewed publication.”

Getting involved with research projects

Although it is possible to do research at medical school, it is important to be realistic about how much free time you have. It might be possible to set up your own research project, but this will require substantial planning in terms of writing research protocols, gaining ethical approval, and learning about new research methodologies. Other opportunities for research that make less demands on your time include:

Intercalated degrees—these often have time set aside for research in a specific area, so it is important to choose your degree according to what you might like to do for your dissertation (for example, laboratory-based work in biochemistry, or qualitative research in global health. Some subjects may have options in both qualitative and quantitative research).

Student selected components or modules can provide a good opportunity to be involved in an ongoing study or research project. If you have a long project period, you might be able to develop your own small project.

Electives and summer holidays can also provide dedicated time for research, either within the United Kingdom or in another country. They can allow you to become established in a research group if you’re there for a few weeks, and can lead to a longstanding relationship with the research group if you continue to work with them over your medical school career.

If you don’t know what to do, contacting the Student Audit and Research in Surgery (STARSurg), 1 the National Student Association of Medical Research (NSAMR), 2 or your medical school’s research society may be a good place to start.

The INSPIRE initative, 3 coordinated by the Academy of Medical Sciences, gives support and grants to help students take part in research. Some UK medical schools have small grants for elective and summer projects, and organise taster days for students to get an idea of different research areas.

You may also be able to access other grants or awards to support your research. Some of the royal colleges, such as the Royal College of General Practitioners and the Royal College of Psychiatrists, offer bursaries to students doing research in their holidays or presenting at conferences. Other national organisations, such as the Medical Women’s Federation, offer bursaries for elective projects.

Box 1: Questions to ask yourself before starting research

What are you interested in? There is no point getting involved in a project area that you find boring.

How much time do you have available? It is crucial to think about this before committing to a project, so that your supervisor can give you an appropriate role.

What do you want to get out of your research experience? Do you want a brief insight into research? Or are you hoping for a publication or presentation?

Do you know any peers or senior medical students who are involved in research? Ask them about their experiences and whether they know of anyone who might be willing to include you in a project.

Box 2: Research output

Publication —This is the “gold standard” of output and usually consists of an article published in a PubMed ID journal. This can lead to your work being cited by another researcher for their paper, and you can get up to two extra points on foundation programme applications if you have published papers with a PubMed ID.

Not all research will get published, but there are other ways to show your work, such as presenting at conferences:

Oral presentation —This involves giving a short talk about your research, describing the background, methods, and results, then talking about the implications of your findings.

Poster presentation —This involves creating a poster, usually A1 or A2 in size, summarising the background, methods, and results of your research. At a conference, presenters stand by their poster and answer questions from other delegates.

Contacting researchers

Most universities have information about their research groups on their websites, so spend some time exploring what studies are being carried out and whether you are interested in one of the research topics.

When contacting a member of the research group, ask if they or someone else within their team would be willing to offer you some research experience. Be honest if you don’t have any prior experience and about the level of involvement you are looking for, but emphasise what it is about their research that interests you and why you want to work with them. It’s important to have a flexible approach to what they offer you—it may not initially sound very exciting, but it will be a necessary part of the research process, and may lead to more interesting research activity later.

Another way to make contact with researchers is at university talks or lectures. It might be intimidating to approach senior academics, but if you talk to them about your interest they will be more likely to remember you if you contact them later on.

Box 3: What can students offer research teams?—Views from researchers

“Medical students come to research with a ‘fresh eyes’ perspective and a questioning mindset regarding the realities of clinical practice which, as a non-medic myself, serves to remind me of the contextual challenges of implementing recommendations from our work.”

Alison Gregory, senior research associate, Centre for Academic Primary Care, University of Bristol, UK.

“Enthusiasm, intelligence, and a willingness to learn new skills to solve challenges—bring those attributes and you’ll be valuable to most research teams.”

Tony Pickering, consultant anaesthetist and Wellcome Trust senior research fellow, University of Bristol, UK.

Box 4: Different types of research

Research aims to achieve new insights into disease, investigations, and treatment, using methodologies such as the ones listed below:

Qualitative research —This can be used to develop a theory and to explain how and why people behave as they do. 4 It usually involves exploring the experience of illness, therapeutic interventions, or relationships, and can be compiled using focus groups, structured interviews, consultation analysis, 5 or ethnography. 6

Quantitative research —This aims to quantify a problem by generating numerical data, and may test a hypothesis. 7 Research projects can use chemicals, drugs, biological matter, or even computer generated models. Quantitative research might also involve using statistics to evaluate or compare interventions, such as in a randomised controlled trial.

Epidemiological research —This is the study of the occurrence and distribution of disease, the determinants influencing health and disease states, and the opportunities for prevention. It often involves the analysis of large datasets. 4

Mixed methods research —This form of research incorporates both quantitative and qualitative methodologies.

Systematic reviews —These provide a summary of the known evidence base around a particular research question. They often create new data by combining other quantitative (meta-analysis) or qualitative (meta-ethnography) studies. They are often used to inform clinical guidelines.

Box 5: Stages of research projects

Project conception—Come up with a hypothesis or an objective for the project and form the main research team.

Write the research protocol—Produce a detailed description of the methodology and gain ethical approval, if needed.

Carry out the methodology by collecting the data.

Analyse the data.

Decide on the best way to disseminate your findings—for example, a conference presentation or a publication—and where you will do this.

Write up your work, including an abstract, in the format required by your chosen journal or conference.

Submit . For conference abstracts, you may hear back swiftly whether you have been offered the chance to present. Publication submissions, however, must be peer reviewed before being accepted and it can take over a year for a paper to appear in print.

Originally published as: Student BMJ 2017;25:i6593

Competing interests: AKT received grant money from INSPIRE in 2013.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

- ↵ STARSurg. Student Audit and Research in Surgery. 2016. www.starsurg.org .

- ↵ NSAMR. National Student Association of Medical Research. 2016. www.nsamr.org .

- ↵ The Academy of Medical Sciences. About the INSPIRE initiative. 2016. www.acmedsci.ac.uk/careers/mentoring-and-careers/INSPIRE/about-INSPIRE/ .

- ↵ Ben-Shlomo Y, Brookes ST, Hickman M. Lecture Notes: Epidemiology, Evidence-based Medicine and Public Health. 6th ed . Wiley-Blackwell, 2013 .

- ↵ gp-training.net. Consultation Theory. 2016. www.gp-training.net/training/communication_skills/consultation/consultation_theory.htm .

- ↵ Reeves S, Kuper A, Hodges BD. Qualitative research methodologies: ethnography. BMJ 2008 ; 337 : a1020 . doi:10.1136/bmj.a1020 pmid:18687725 . OpenUrl FREE Full Text

- ↵ Porta M. A Dictionary of Epidemiology. 5th ed . Oxford University Press, 2008 .

Will You Be a Catalyst for India's Medical Research Revolution?

Research methodology teaching for undergraduate medical students – an interesting project

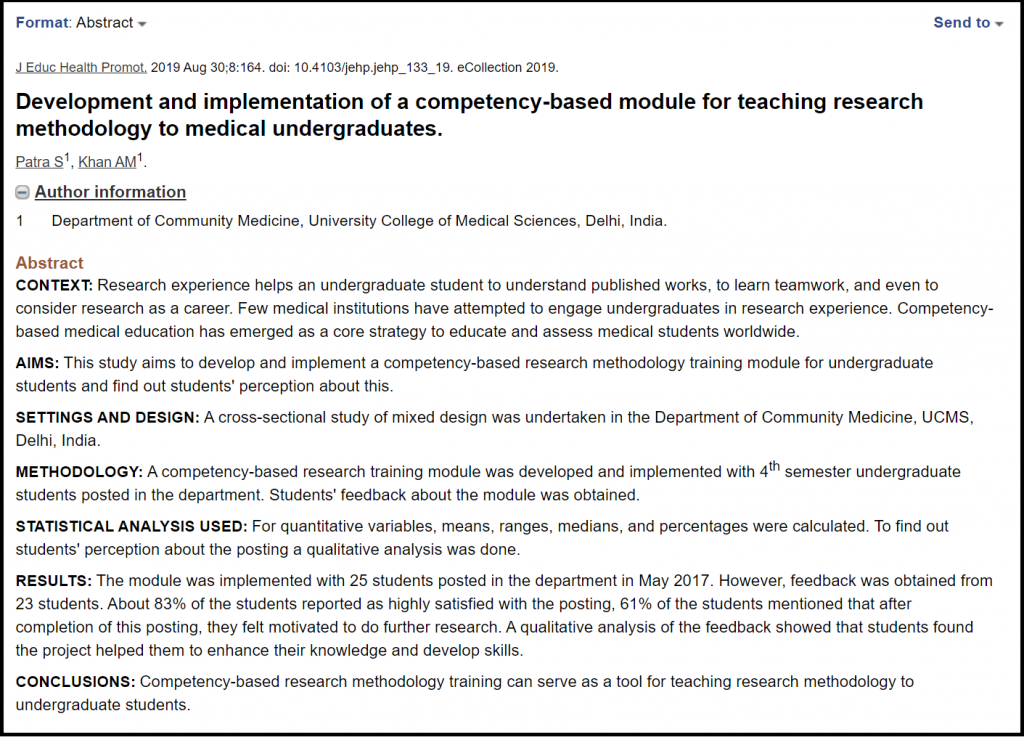

Development and implementation of a competency-based module for teaching research methodology to medical undergraduates.

Patra S, Khan AM J Educ Health Promot. 2019 Aug 30;8:164 PMID:31544129

The authors did this study as a part of a FAIMER fellowship program (CMCL-FAIMER). It aimed to develop and carry out a “competency-based research methodology” training module for undergraduate students and get the students’ feedback on this. It was carried out in the Community Medicine Department, for 25 students in their 4th semester . The study was done in the year 2017.

This group of 25 students were made to work in groups under supervision of senior residents and faculty. It appears that the students worked on a single topic, but did data collection individually and then assessed the entire data. They were, in this way initiated into understanding the research process.

It was interesting to learn that more than 60% felt that this exercise motivated them to do research in future! Also that their self perceived gain in knowledge was 4 or 5 as a median in a scale of 1-5. Very impressive!

While the authors rightly state the limitations, it seems that it does not take a very big (or expensive) effort to sensitize and motivate undergraduate students towards research. As the authors mention, the MCI has mentioned that UG students must get sensitized in research methodologies.

I have very often heard faculty / seniors mentioning that they would rather have UG students only study textbooks and get their foundations firm. Of course they need a very firm foundation of medical knowledge. But, it is increasingly obvious that they need to be sensitized and get a basic hands on experience of what it takes to do research. Thankfully the ICMR STS projects have done something in this direction (increasingly) over years. But this training in an institution seems well worth replicating!

Note: I was particularly pleased to note that the students gave a feedback of 4/5 in the understanding their literature search process . Dr AM Khan , one of the authors has been a participant of one of my workshops on literature searching and referencing, and I am sure he did a great job in ensuring that the students were taught the basic skills in searching

One Comment

The excitement of, and passion for research takes hold as early as you care to begin. From kindergarten on, they rub off the teachers and stick to the students like wet paint. Of course, teachers must soak in the paint first. The cascading effect of one QMed workshop coloured several generations at UCMS with the fervor for effectively searching the medical literature. That’s all it takes. The rest is fun and games.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

For security, use of Google's reCAPTCHA service is required which is subject to the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Use .

I agree to these terms .

Related Posts

Medical students can be mentored to enjoy research!

Infodemic – the avalanche who can help, conducted a clinical trial in india it maybe yes and no, about courses.

QMed Knowledge Foundation

A-3, Shubham Centre, Ground Floor Cardinal Gracious Road, Chakala, Andheri East, Mumbai - 400099. Phone: +91-22-40054474 Email: [email protected] Any questions? Write to us

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- v.14(5); 2022 May

Medical Education and Research in India: A Teacher’s Perspective

Venkataramana kandi.

1 Clinical Microbiology, Prathima Institute of Medical Sciences, Karimnagar, IND

Medical education is a systematic process wherein interested and eligible individuals are trained to become physicians/surgeons. It is assumed that a person who completes the Bachelor of Science and Bachelor of Medicine (MBBS) degree will be competent enough to perform the duties of a physician of first contact. However, it is not the case with graduates from India. Most MBBS graduates prefer to pursue a postgraduate degree and become unavailable to people or governments. The doctor-to-patient ratio in India (1:1,655) does not currently satisfy the World Health Organization’s prescribed ratio (1:1,000). The Government of India, therefore, has been taking initiatives to increase the number of MBBS graduates. Moreover, there are several doubts over the quality of medical education and the competency of medical students. In addition, the National Medical Commission, the epic body that regulates the medical education and practice in India, has recently been conducting medical education technology workshops to improve teachers and has devised a new curriculum to elevate the standards of medical education in India. This editorial attempts to provide readers with the current status of medical education and research in India.

The Indian medical education system has recently seen a makeover in the form of a change in the curriculum. This change may have become inevitable due to growing concerns, both within the country and globally, over the low standards and quality of MBBS graduates. It has been widely accepted that medical students graduating from Indian institutions are not competent enough to practice. This is evident by the requirement for medical graduates from India to clear the United States Medical Licensing Examination (USMLE) to practice in the United States. Therefore, the National Medical Commission (NMC), previously known as the Medical Council of India (MCI), has come forward with a vision to revamp medical education in India. The main motto of this initiative by the NMC is to ensure that Indian medical graduates (IMG) are competent enough to function as community physicians of first contact [ 1 ]. This decision by the Government of India (GOI) was taken after considering the high disease burden among people, as well as the huge disparities in the status of medical institutions/establishments/facilities/services within different geographical regions of the country. Moreover, the NMC has made it mandatory for all medical teachers to undergo a training program on medical education technology (MET). The NMC regularly conducts basic and advanced workshops/courses for all medical teachers in the country. However, the NMC appears to have ignored the most significant aspect that could potentially contribute to the success of a teacher/learner in medical education. The attitudes of both the teachers and learners significantly influence the learning outcomes, thereby affecting the competency of medical graduates. Carefully designed faculty development programs may contribute to medical teachers’ professionalism, management, and leadership abilities that further enable students to become competent physicians [ 2 ].

The current scenario

Most medical teachers, especially those who participate in the teaching of students in their I MBBS and II MBBS may be considered accidental teachers. Although this is not usually considered a topic for discussion, it must be noted that the first two years of the MBBS course function as a foundation for students. During this period, students learn basic subjects, including anatomy, physiology, biochemistry, pathology, microbiology, and pharmacology. Basic and comprehensive knowledge of these subjects is considered extremely useful to understand the clinical subjects that the students pursue from the third year of the MBBS course. However, in practice, disinterested teachers are misguiding students to learn the subjects from an examination point of view rather than emphasizing the importance of the role played by pre and para-clinical subjects for the rest of their future in the medical profession (clinical relevance and integrated approach). The scenario may be the same with teachers who opt for less familiar clinical degrees after having compromised on their specialization of interest. Unfortunately, specializations gain familiarity based on the expected earnings they can get during the practice and not particularly about the interest/skills they have concerning the subject/specialization.

The NMC and GOI’s decision to improve the doctor-to-patient ratio has indirectly affected the teacher-to-student ratio. With increased numbers of medical institutions being permitted and more in the pipeline, there is a continuous movement of faculty resulting in transient deficiencies of faculty that directly affects the quality of curriculum delivery despite the improvement/change in the curriculum, as envisaged by the NMC recently. Further, the NMC and the GOI must consider the numbers of MBBS and MD (Doctor of Medicine) graduates who move out of the country for livelihood and other reasons. Interestingly, not many medical graduates were available who volunteered during the initial days of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. Therefore, public and private healthcare facilities were forced to work with medical students (house surgeons/interns/final MBBS students) and fresh MBBS graduates. The main reason is that MD graduates belonging to the pre and para-clinical subjects, sparing a few, lose their connectivity to medicine and lack the confidence to examine patients. This aspect needs serious consideration by the GOI, NMC, local governments, as well as the doctors themselves, who should make efforts to provide their services by running evening community clinics.

Admission for entry into the MBBS course is currently carried out based on reservations following the caste system that is prevalent in India. A significant percentage of seats are filled based on the student’s capability to pay fees, and some are accommodated to the non-resident Indian (NRI) category. Similarly, the admission of students is based on a competitive multiple-choice-based examination that does not evaluate students’ interests and attitudes and merely evaluates their theoretical knowledge. These are the main reasons for the deteriorating quality of medical graduates in India. Conversely, the deterioration in quality comes from the fact that the concepts that were described in the medical education workshops are not pursued by the majority of faculty members across medical colleges in India. Compared to the olden days, currently, teachers are not spending enough time with students and patients, especially in the clinical departments.

Medical teachers

Teachers appointed in medical institutes are required to have an MD degree in the respective subjects. However, the NMC has allowed the appointment of non-medical teachers (teachers without an MBBS degree) for up to 30% (50% in biochemistry) in both pre and para-clinical subjects excluding the department of pathology [ 3 ]. This was mainly due to the lack of qualified MD teachers available for the job. Recently, the change in the medical education curriculum with more emphasis on competency and competency-based medical education (CBME) has forced the NMC to reconsider the appointment of non-medical teachers. Therefore, NMC has decided to reduce the number of non-medical teachers in the anatomy, physiology, and biochemistry departments, and stop the recruitment of such teachers to the microbiology and pharmacology departments. The decision of the NMC regarding non-medical teachers was long pending with complaints about such teachers emerging over the years both from students as well as teachers with MD degrees. The major reason for the NMC’s decision to minimize and remove non-medical teachers is because the GOI and the NMC have already given a green signal/approval for admission into several MD courses in these departments. On the contrary, many MBBS graduates who fail to pursue a clinical MD/MS degree have been opting for non-clinical (pre and para-clinical) MD subject specialization courses. However, this decision by the NMC had some drawbacks. The major one is the lack of interest among MBBS graduates admitted in the concerned subject of specialization. After joining the courses, these students face difficulties in completing the course at the designated time. Moreover, the mandatory dissertation required for them to complete the course is not done with the required/desired technical and ethical standards.

In contrast to a Ph.D. degree, wherein the pursuant does research work for at least three years to become eligible for the award of the degree, MD graduates work as part-time teachers (tutor/junior resident/senior resident) and are able to complete the course within three years. All universities in India come under the aegis of the Union Grants Commission (UGC). However, medical institutions and medical universities function under the umbrella of the NMC. The UGC mandates that Ph.D. students publish at least two original research articles in reputed journals and present at least one abstract in a national/international conference to become eligible to be awarded the degree. This is in complete contrast to the MD degree, wherein the students only undertake research work for a maximum period of one year, and it is not mandatory to publish/present papers in journals/conferences. Moreover, the period during the MD study is considered a teaching experience in the position of resident/tutor/demonstrator. Therefore, MD degree holders become eligible for appointments as assistant professors after the study period. This points to the fact that an MD degree must not necessarily be considered a research degree. The UGC has a mechanism wherein the Ph.D. thesis and postgraduate dissertations submitted by the students are deposited in a repository (Shodhganga) and are carefully screened for plagiarism before they are approved/accepted. The Information and Library Network Centre (INFLIBNET) is an autonomous interuniversity center of the UGC [ 4 ]. However, even today, this practice is not followed by medical universities. Therefore, MD dissertations are generally not as standard as Ph.D. theses. Medical Universities, in the future, should consider screening all MD dissertation submissions for potential plagiarism and make the dissertations available in the public domain (similar repository as the INFLIBNET). Several institutions do not support the financial aspects of the MD dissertation, and this limitation could be the reason why the students are unable to pursue real research and finally end up writing dissertations without even working on the topic. This situation can be improved by active vigilance by the NMC and at the institutional level regarding the MD dissertations and their standards. Given the above observations, the matter of equivalence of an MD degree with a Ph.D. degree appears to be questionable. However, medical universities in India and autonomous research institutes funded by the GOI are accepting/recognizing MD degree holders as Ph.D. guides. Such practices should be re-evaluated by higher education bodies/councils because it affects the standards of Ph.D. holders and their future in research activities.

Medical research

Medical teachers who were not properly trained in research end up being not interested in pursuing research after obtaining their degrees. This probably was the main reason why the NMC was particular about the research publications requirement for promotions. However, medical teachers find it difficult to do even these mandatory research publications. This is majorly attributed to the lack of financial and logistic support from the public and private administrations. The lack of proper research orientation among medical teachers appears to have significantly impacted the research inclination of students. Moreover, medical institutions have not been supportive of the research activities of both the faculty and students. The GOI, under the Indian Council for Medical Research, has been implementing limited numbers of short-term studentship (STS) research fellowships (two-month duration) for medical students [ 5 ]. Despite this initiative, many more interested students will remain unbenefited. This issue may be addressed by the institution by devising a mechanism wherein research-oriented faculty may be roped into a group (research wing) that mainly functions to facilitate interested students to pursue research work under able faculty members. Because research work involves financial implications, medical institutions must create a fund (crowdfunding, donations, corpus, others) that potentially serves this purpose.

The criteria for promotion that requires a medical teacher to have published at least two papers in an indexed journal also appear to be responsible for the deterioration of research standards among medical teachers and institutions. This decision by the NMC was instrumental in the emergence of several predatory journals that claim to have been indexed by the agencies recognized/prescribed by the NMC. However, the NMC realized and changed its decision and excluded the Index Copernicus as the desired indexing agency that was responsible for the emergence of pay-to-publish journals. Interestingly, the NMC recently added the Indian Citation Index to the list of desired indexing agencies along with others that are already present, including PubMed, Scopus, DOAJ, and EMBASE, among others. Given unethical research and publication practices, the NMC may choose to accept literature reviews as an acceptable type of article in consideration for promotions. This will enable faculty members to pursue research and get increasingly acquainted with current trends with extremely limited resources and encourage within-country and foreign collaborations.

Other concerns

Despite several positive changes by the NMC, medical institutions are further plagued by the problems of ghost faculty, ghostwriters, and other malpractices related to examinations, research, dissertation work, and publications. The factors that potentially affect medical education and research in a medical institution are depicted in Figure Figure1 1 .

Ghostwriter

Ghostwriters are anonymous persons who write manuscripts (that in this case are represented by research publications) for teachers who require them for promotions. A ghostwritten research article is used by a teacher to his/her credit by implanting his/her name on it and without mentioning the person who has written it. Moreover, ghostwritten articles are not necessarily written based on authentic data collected after conducting bench work. These amount to malicious practices under the recommendations by the Committee of Publication Ethics (COPE). Ghostwriters have been in full function helping several medical teachers to acquire research publications required for promotions. The problem with ghostwriting is that authors claim a work neither by doing nor by writing. Such literature that is written without actually working and available as published content in the public domain will adversely influence the scientific community and public health.

Ghost faculty

It has been a frequent occurrence in the past decade, wherein medical teachers representing more than one medical college appear before the NMC during inspections. However, NMC did identify this problem and punished several such medical faculties. There was also a problem of duplicate faculty wherein the certificates of a medical person were used to wrongly represent the faculty. Despite strict vigilance by the NMC, the newest trend is the ghost faculty. Medical colleges call upon qualified medical graduates during the inspection and show them as resident faculty members to the NMC. It is an open secret that is followed ubiquitously by several institutions throughout India. Interestingly, the faculty list shown by the institutes could range between 15 and 20 in each department during the inspection days. However, once the NMC inspection is completed, the actual faculty that works on the ground is considerably low in numbers (hardly 10). This significantly affects the faculty-to-student ratio. Assuming a college has 200 students, and the college shows 15 staff during the inspection, the actual number of teachers working on the ground will be less than 10. This results in overcrowding during practical demonstrations, and, for this reason, many students do not follow/understand the practical aspects. Moreover, with a smaller number of faculty members, teachers do not function in the manner that allows them to train each student adequately. Several practicing doctors and academically uninterested graduates are approached by the institutions. Due to the financial favors offered by institutions, medical graduates agree to be on the rolls of the college.