What Do Kids Learn in Kindergarten?

Whether physical, emotional or social, developing life skills is what kindergarten is all about.

Getty Images

Kindergarten provides the building blocks of a strong education.

Millions of children will grab lunchboxes, backpacks and rolling bags and head to their first day of kindergarten this year. Some will go for a half day and some for a full. Some will attend private schools and some will go public. For all, however, the first day of kindergarten will inaugurate their arrival in a system where they will spend a dozen years receiving basic education.

Virtual Field Trips for Kids

Kristen Hampshire April 22, 2021

It begs some questions. What are the hallmarks of a high-quality kindergarten classroom? What can parents expect to see in the curriculum? How can mom and dad continue educating at home? In short, what do kids learn in kindergarten?

The answer is that kindergarten provides the building blocks of physical, social and emotional development, as well as the basics of language, literacy, thinking and cognitive skills. Equally important, it provides a bridge from education at home or in preschool to education in a more traditional classroom, where children must interact with a teacher, a set of rules and each other in order to learn.

“I think kindergarten is a good entry point into our education system,” says Alissa Mwenelupembe, senior director for early learning program accreditation at the National Association for the Education of Young Children, a professional organization that works to advance the quality of early learning. “It can really support some of the social-emotional goals that children need to meet so that they can be successful in future academic pursuits.”

Kindergarten Across the U.S.

Almost 4 million children attend kindergarten in the United States each year, according to the U.S. Census Bureau , but kindergarten instruction can be different in every locale, based on a number of variables.

For starters, while kindergarten is available almost everywhere, attendance is only mandatory in 19 states and Washington, D.C., according to the Education Commission of the States . In most communities, both full- and half-day programs are available.

Seventeen states plus Washington, D.C., require full-day kindergarten, and 39 states require districts to offer both full- and half-day options. About 81% of children in kindergarten attended full-day programs as of 2018, the latest year for which numbers are available from the National Center for Education Statistics . That number has increased over the years, climbing from 60% in 2000.

What students learn in kindergarten may also be affected by whether they are attending public school or private. Among the U.S. students who attend kindergarten, only about 15% do so in a private school, according to an analysis by the research firm Statista using 2019 data.

There are also regional differences. In some parts of the country, more emphasis is placed on academic subjects like reading and math, says Tamar Lindenfeld, founder of Chalkdust Inc., which provides tutoring, supplemental learning and academic consulting.

“In New York, the focus for the past 10 or maybe 15 years has been a lot more academic and a lot more rigorous,” she says.

Learning in Kindergarten

According to a primer by the National Association for the Education of Young Children, a high-quality kindergarten should address learning in several categories:

- Physical development. This is the development of large motor skills, meaning movement of arms and legs, and fine motor skills, or use of hands and fingers. Playing outside and doing physical activities as a class address the former. Puzzles, drawing and other in-class activities address the latter.

- Social development. This is how a child interacts with others, including working cooperatively, making friends, resolving disputes and other skills. Many aspects of classroom activity will be designed to develop these skills, helping children get along with one another.

- Emotional development. This helps children understand and manage their own feelings. “Teachers help children recognize, talk about, and express their emotions and show concern for others,” the association wrote. “They also support children's development of self-regulation—being able to manage their feelings and behavior.”

- Language and literacy. This develops communication through reading, writing, talking and listening. Literacy is a major focus in early learning, and particularly in kindergarten, because these skills are so critical. Students learn to read so they can read to learn in later grades.

- Thinking and cognitive skills. This encourages students to investigate, make observations, ask questions and solve problems. “Teachers help children plan what they're going to do, encourage children to discuss and think more deeply about ideas, and include children when making decisions,” the association wrote.

Subjects like math, reading, writing, science, social studies and art are also offered in high-quality kindergartens. Mwenelupembe, who is involved in accrediting facilities, says what she looks for in a healthy kindergarten classroom is energy and activity, with children engaging both learning materials and each other to facilitate all aspects of development.

“What is important in kindergarten, but you don't always see, is that playful learning is happening,” she says. “When children are sitting at desks all day and doing things like worksheets, it doesn't really connect with what we know about the brain and how children's brains learn.”

How Parents Can Help

There is much that parents can do to help kindergarten-age children develop in all of these categories, according to education experts. “Parent participation is key,” Clare Anderson, an educational consultant in Maryland, wrote in an email.

“Skills such as persistence and stamina are critical for children to tackle foundational tasks for oral language, vocabulary, and number sense,” she says. “Parents can play an enormous role in encouraging children to wonder, question, and explore.”

Here are some things that parents can do to help kindergarteners learn:

- Encourage exploration. Education experts say that everyday activities can be major opportunities for kindergarten-age children to learn everything from cognitive skills to literacy. One example is a simple trip to the grocery store.

- Talking about the difference between the vegetables, talking about the colors of the produce, talking about how many of something you need, helping them to understand how much things cost – all of those regular, everyday moments are such important pieces of learning that are going to carry through when they get to school,” Mwenelupembe says.

- Engage in conversation. Taking the time to have full conversations with children and explain the things happening around them at home can be extremely beneficial, whether that’s cooking a meal or watering the garden. “Being able to speak and fully explain the things that you're doing to your child provides them with so much vocabulary and so much understanding,” Lindenfeld says.

- Read. Few things do more to further literacy than reading to and with a child. Having a large and compelling selection of books at home and reading those books together is always time well spent.

- Reading to your child is always beneficial,” Lindenfeld says. “No matter the age, no matter how long you're doing it for. If you only have 15 minutes a day, those 15 minutes of reading will be very valuable to your child.”

- Build everyday skills. Anything that requires thinking and cognitive skills can help children learn. “To reinforce kindergarten learning, I would think (about) anything that promotes the development of the brain's executive functions,” Lindenfeld says. “So like anything that builds the ability to think critically, problem solve, multitask, organize, plan or analyze.”

- Encourage physical activity. Opportunities to build motor skills are abundant, but experts also say physical activity can be combined with reading and other subjects to make learning more fun and beneficial. For example, after hearing an adult read a story, children can draw a picture or act out what was read. As Mwenelupembe puts it, “Children learn with their whole bodies.”

Searching for a school? Explore our K-12 directory .

Best States for Early Education

Tags: education , K-12 education , Coronavirus , parenting , safety , elementary school , middle school , high school

2024 Best Colleges

Search for your perfect fit with the U.S. News rankings of colleges and universities.

Popular Stories

Best Colleges

College Admissions Playbook

You May Also Like

Choosing a high school: what to consider.

Cole Claybourn April 23, 2024

Map: Top 100 Public High Schools

Sarah Wood and Cole Claybourn April 23, 2024

States With Highest Test Scores

Sarah Wood April 23, 2024

Metro Areas With Top-Ranked High Schools

A.R. Cabral April 23, 2024

U.S. News Releases High School Rankings

See the 2024 Best Public High Schools

Joshua Welling April 22, 2024

Explore the 2024 Best STEM High Schools

Nathan Hellman April 22, 2024

Ways Students Can Spend Spring Break

Anayat Durrani March 6, 2024

Attending an Online High School

Cole Claybourn Feb. 20, 2024

How to Perform Well on SAT, ACT Test Day

Cole Claybourn Feb. 13, 2024

- Book Lists by Age

- Book Lists by Category

- Reading Resources

- Language & Speech

- Raise a Reader Blog

- Back to School

- Success Guides by Grade

- Homework Help

- Social & Emotional Learning

- Activities for Kids

What Makes for a Good Kindergarten Experience?

See how to evaluate a program and how to advocate for your child if their classroom doesn't measure up..

Ideally, kindergarten will be a smooth, sunny introduction to real school for your child, since it sets the stage for the rest of his education. While no program is perfect, some are better than others. Find out what sets them apart and how you can get the best possible start for your child — no matter what your options are. (Also be sure to check out our guide to kindergarten to know what you can expect from the year ahead!)

Why Kindergarten? First, consider the goal of a good kindergarten program. Kindergarten provides your child with an opportunity to learn and practice the essential social, emotional, problem-solving, and study skills that he will use throughout his schooling.

- The development of self-esteem is one of the important goals of kindergarten. This is the process of helping your child feel good about who she is and confident in her ability to tackle the challenges of learning. Books can be a great help with this — these picks help boost confidence in kids.

- Kindergarten teaches cooperation : the ability to work, learn, and get along with others. A year in kindergarten provides your child with the opportunity to learn patience, as well as the ability to take turns, share, and listen to others — all social and emotional learning skills that he will use through his school years and beyond.

- Most children are naturally curious, but some do not know how to focus or use this curiosity. Kindergarten is a time for sparking and directing your child’s curiosity and natural love of learning.

What Does an Ideal Kindergarten Look Like? Ask any number of educators and parents, and you will get many different descriptions of the ideal kindergarten. But there are certain basic agreements among educators as to what makes a good program. It should:

- Expand your child’s ability to learn about (and from) the world, organize information, and solve problems. This increases his feelings of self-worth and confidence, his ability to work with others, and his interest in challenging tasks.

- Provide a combination of formal (teacher-initiated) and informal (child-initiated) activities. Investigations and projects allow your child to work both on her own and in small groups.

- Minimize use of large group activities that require sitting. Instead, most activities feature play-based, hands-on learning in small groups. As the year progresses, large group activities become a bit longer in preparation for 1st grade.

- Foster a love of books, reading, and writing. There are books, words, and kids’ own writing all over the classroom.

When looking at programs, keep these elements in mind — as well as the specific needs of your child and family. Not every program is perfect for every child. Some children thrive in a program with more direction, some with less. Talk to your child’s preschool teacher, visit a few schools, and talk to the principal or a kindergarten teacher before deciding.

What if the Program Is Less Than Ideal? Perhaps you have little or no choice about where to send your child to kindergarten but are concerned about its quality. First, give the program and teacher some time to get the year going. If you observed the class in the spring and it seems different when your child starts in the fall, there may be a good reason. Many programs start slowly, taking time to help children separate from their families and feel confident in school before adding learning demands.

If after a few weeks you still have concerns, talk to the teacher. Ask her about her goals and share your expectations. Sometimes an apparent mismatch can be just a difference in approach. Keep the dialogue going. Ask for information, but also be willing to hear the “whys” of the teacher’s philosophy.

Still, there are times when a teacher or his approach is not the right fit for your child. Then it is time to talk with the principal . Come prepared with clear points you want to make. This will help the principal see what the problem is and make suggestions to help your child.

Sometimes (but rarely) children need to switch to a different teacher or school. This can be the result of many classroom observations of your child by the teacher, principal, and/or another professional. It is important to have group consensus on this decision.

Help prepare your child for a successful school year with the best kindergarten books at The Scholastic Store . Plus, explore more expert-approved kindergarten books, tips, and resources at our guide to getting ready for kindergarten , including recommended kindergarten reader s.

Want more activities and reading ideas? Sign up for our Scholastic Parents newsletter.

Amazing Kindergarten Books

Sign up and get 10% off books.

Education Policy

Teaching in the ways kindergartners learn best, play, relationships, and challenging content.

Picture taken by Laura Bornfreund

Laura bornfreund, erin freschi, march 31, 2023.

This blog post is the first in a series on Promoting Impactful Teaching and Learning in Kindergarten .

Kindergarten is an important year for children and their families. For some, it is their first experience in formal education. Some children may be away from their parents or caregiver for the first time. For those who attended an early childhood program, whether in a center, family childcare home, or with a care provider in the neighborhood, kindergarten may look and feel different than their previous experiences. While kindergarten is the first universal education access point for children, they bring diverse experiences and strengths to the classroom. And it’s incumbent on schools and educators to be ready for children regardless of what those experiences and strengths are.

Transitioning into kindergarten can be an intimidating experience for children and families unless kindergarten is a sturdy bridge that supports families and children through the transition, connecting what comes before and after, and regardless of the learning environments, they may have had. State leaders, district administrators, and kindergarten teachers themselves have an opportunity and an obligation to ensure equitable experiences for children and families through this transition, setting the stage for future growth and goal attainment. Ensuring equitable experiences requires implementing developmentally appropriate practices in kindergarten and addressing inequitable access to kindergarten for many children in this country.

If you attended kindergarten prior to the mid-1990s you may recall lots of play, singing, and graham crackers. Over the years, there has been a shift as kindergarten has become more structured and academic, with limited play and outdoor time. Children are often expected to sit at tables and complete worksheets and other rote close-ended activities. According to the National Association for the Education of Young Children (NAEYC ), play is a critical component of early childhood and children's physical, social, and emotional development, yet play has largely disappeared in kindergarten.

Research has shown that children learn best when they are engaged in developmentally appropriate experiences and activities: play! A developmentally appropriate kindergarten environment can support children socially and emotionally and foster positive relationships with peers and adults. According to Turnaround for Children , “...when educators neither prioritize these skills and mindsets nor integrate them with academic development, students are left without tools for engagement or a language for learning.” Developmentally appropriate environments provide the building blocks to guide the development of executive functioning skills and support foundational literacy, language, and math skills while also providing opportunities for fine and gross motor development. By incorporating play and developmentally appropriate practice into the kindergarten environment, teachers can support all children as they continue to grow and develop during this critical time in their lives.

During a webinar co-sponsored by New America and Campaign for Grade-Level Reading webinar in October 2022, A Pivotal Year: Kindergarten’s Important Role in Students’ Education, Ellen Galinsky, author of Mind in the Making, and Ryan Lee-James, Chief Academic Officer at the Atlanta Speech School, dug deeper into building executive function and children’s reading brain during the kindergarten year. Galinsky urged conversations about kindergarten readiness to move away from focusing on what kindergartners lack when they enter school and instead focus on the strengths they bring and how to then build from there. Schools must be ready for all children. Lee-James highlighted the importance of relationships for building a reading brain. She also discussed how COVID wreaked havoc on children’s learning but pointed out that schools struggled to meet all children’s needs, especially children from marginalized communities, before COVID. “We need to do better for our young learners.”

A second webinar in November 2022, Play + Academics, Relationships,” Teaching in Ways Kindergartners Learn Best explored the most important research findings on teaching and learning in kindergarten. One panelist, Nell Duke, Executive Director of the Center for Early Literacy Success at Stand for Children, spoke about the importance of looking for opportunities for interdisciplinary instruction when you’re developing language. “When you’re developing literacy, you’re developing science and math,” she said. Kathy Hirsch-Pasek, Professor at Temple University, raised how necessary it is to start “with the cultural values that are meaningful to the community that you’re working in.” And, Anya Hurwitz, Executive Director of Sobrato Early Academic Language, built on Hirsch-Pasek’s point, noting that “when children are engaged, when they’re interested, when they’re curious, the learning is deeper.”

Making learning relevant for young children, recognizing the assets and culture they bring to the classroom, and making learning joyful are all part of delivering developmentally appropriate practice.

There are many opportunities to incorporate developmentally appropriate practice, including playful learning, into the kindergarten classroom. Some strategies include:

- Maintaining an intentional emphasis on fostering social and emotional development including supporting relationship development with peers and adults. Providing a safe and supportive social space is the cornerstone of all learning.

- Using a whole child approach meeting children where they are developmentally working toward individualized goals based on their unique needs

- Prioritizing learning opportunities through engaging, guided play in place of close-ended and rote memory activities.

- Utilizing a daily structure that provides children with flexibility and ample opportunities for gross motor and outdoor activities.

- Providing opportunities for student choice and autonomy in their learning and for student talk and collaboration

- Incorporating intentional, culturally responsive, and inclusive family engagement programs and activities.

- Ensuring written materials in the classroom are reflective of the home languages and culture of the children in the class and available in all areas where the child engages throughout the day.

- Remembering always that kindergarten should reflect a joy of learning!

To support kindergarten and early grade educators in delivering these developmentally appropriate practice ideas, state and local education agencies can promote curricula and instructional tools that are aligned with DAP, provide professional learning opportunities to build teacher and principal understanding of child development, and resources to ensure that classrooms are equipped to allow for exploration, discovery, and play.

Enjoy what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter to receive updates on what’s new in Education Policy!

Related Topics

Why early childhood care and education matters

The right to education begins at birth.

But new UNESCO data shows that 1 out of 4 children aged 5 have never had any form of pre-primary education. This represents 35 million out of 137 million 5-year-old children worldwide. Despite research that proves the benefits of early childhood care and education (ECCE), only half of all countries guarantee free pre-primary education around the world.

UNESCO’s World Conference on Early Childhood Care and Education taking place in Tashkent, Uzbekistan on 14-16 November 2022 will reaffirm every young child’s right to quality care and education, and call for increased investment in children during the period from birth to eight years.

Here’s what you need to know what early childhood care and education.

Why is early childhood care and education important?

The period from birth to eight years old is one of remarkable brain development for children and represents a crucial window of opportunity for education. When children are healthy, safe and learning well in their early years, they are better able to reach their full developmental potential as adults and participate effectively in economic, social, and civic life. Providing ECCE is regarded as a means of promoting equity and social justice, inclusive economic growth and advancing sustainable development.

A range of research and evidence has converged to support this claim. First, neuroscience has shown that the environment affects the nature of brain architecture – the child’s early experiences can provide either a strong or a fragile foundation for later learning, development and behaviours. Second, the larger economic returns on investment in prior-to-school programmes than in programmes for adolescents and adults has been demonstrated. Third, educational sciences have revealed that participation in early childhood care and education programmes boosts children’s school readiness and reduces the gap between socially advantaged and disadvantaged children at the starting gate of school.

From a human rights perspective, expanding quality early learning is an important means for realizing the right to education within a lifelong learning perspective. ECCE provides a significant preparation to basic education and a lifelong learning journey. In 2021, only 22% of United Nations Member States have made pre-primary education compulsory, and only 45% provide at least one year of free pre-primary education. Only 46 countries have adopted free and compulsory pre-primary education in their laws.

How has access to ECCE evolved?

Overall, there has been significant global progress in achieving inclusive and high-quality ECCE. Globally, the ratio for pre-primary education has increased from 46% in 2010 to 61% in 2020. The global ratio for participation in organized learning one year before the official primary school entry age also increased to reach 75% in 2020. However, in low- and lower-middle-income countries, fewer than two in three children attend organized learning one year before the official primary entry age. Furthermore, the proportion of children receiving a positive and stimulating home environment remains significantly low with only 64% of children having positive and nurturing home environments. Great regional disparities remain the biggest challenges. In sub-Saharan Africa, only 40% of children have experienced a positive and stimulating home learning environment compared to 90% of children in Europe and Northern America.

How has the COVID-19 pandemic impacted ECCE?

The COVID-19 pandemic has had devastating effect on ECCE and amplified its crisis. Young children have been deemed the greatest victims of the pandemic, experiencing the impact of on their immediate families, and because of stay-at-home orders of lockdowns, having been deprived of essential services to promote their health, learning and psychosocial well-being. Some children will start basic education without organized learning experiences to the detriment of their readiness for school. It was estimated that the closure of ECCE services has resulted in 19 billion person-days of ECCE instruction lost with 10.75 million children not being able to reach their developmental potential in the first 11 months of the pandemic.

What are the consequences on foundational learning?

ECCE is a pre-requisite for meeting the right to learn and to develop. In particular, access to pre-primary education is a basis for acquiring foundational learning including literacy, numeracy and socio-emotional learning. Yet, according to the recent estimate, about 64% of children in low- and middle-income countries cannot read and understand a simple story at age 10. The roots of this learning poverty start in ECCE and its lack of capacity to make children ready for school.

What is the situation regarding ECCE teachers and care staff?

As the calls grow for higher quality ECCE provision, teacher shortages and quality has received increasing attention. The number of teachers who received at least the minimum pedagogical teacher training, both pre-service and in-service, increased from 68% to 80% between 2010 and 2020. It is estimated that ECCE services need another 9.3 million full-time teachers to achieve the SDG target . Most Member States have established qualification requirements for ECCE teachers, while far less attention has been focused on ECCE teachers’ working conditions and career progression. The low social status, poor salaries and job insecurity of ECCE teachers and care staff tend to have an adverse impact on attracting and retaining suitably qualified early childhood educators.

What are the policies, governance and financing implications?

It is time for societies and governments to implement relevant policies to recover and transform their ECCE systems. ECCE is seen by many countries as a key part of the solution to a myriad of challenges including social inclusion and cohesion, economic growth and to tackle other sustainable development challenges. According to the 2022 Global Education Monitoring Report, 150 out of 209 countries have set targets for pre-primary education participation by 2025 or 2030. The proportion of countries that monitor participation rates in pre-primary education is expected to increase from 75% in 2015 to 92% in 2025 and 95% in 2030. It is expected that the pre-primary participation rate for all regions will exceed 90% by 2030. In Central and South Asia, East and South-East Asia, and Latin America and the Caribbean, participation rates are expected to be nearly 100%. At the same time, it is projected that participation rates in Northern Africa and Western Asia will be about 77% by 2030.

What are the obstacles to ensuring access to quality ECCE?

- Policy fragmentation: In many countries, ECCE policies and services are fragmented and do not leverage whole-of-government and whole-of-society approaches to addressing the holistic needs and rights of families and their young children. This is particularly challenging for national governments with limited resources, low institutional capacities and weak governance.

- Lack of public provision : Non-state provision of ECCE continues to grow in many contexts, and the role of non-state actors in influencing policy development and implementation is evident. Non-state actors provide a large proportion of places in pre-primary education. In 2000, 28.5% of pre-primary aged children were enrolled in private institutions, and this rose to 37% in 2019, a figure higher than for primary (19%) or secondary (27%) education.

- Insufficient regulation of the sector : Specific regulations and standards for ECCE are not in place in most countries. Regulations usually do not establish quality assurance mechanisms and those that do, tend not to focus on outcomes.

- Chronic underfunding : An average of 6.6% of education budgets at national and subnational levels were allocated to pre-primary education. Low-income countries, on average, invest 2% of education budgets in pre-primary education, which is far below the target of 10% by 2030 suggested by UNICEF. In terms of international aid, pre-primary education remains the least funded sector.

What are the solutions?

Political will and ownership are key to transforming ECCE. UNESCO’s review highlights progress in some countries, giving an indication of what is required to successfully strengthen the capacity of ECCE systems:

- Expanding and diversifying access : Increasing investment and establishing a legal framework to expand ECCE services are essential steps. Innovative ECCE delivery mechanisms such as mobile kindergartens with teachers, equipment for learning and play, have been deployed in some countries to reach remote areas and provide children with pre-primary education.

- Enhancing quality and relevance : ECCE curriculum frameworks should cover different aspects of early learning and prepare children with essential knowledge, skills, and dispositions to transit smoothly to formal education.

- Making ECCE educators and caregivers a transforming force : For the transformation of ECCE to take place, ECCE educators need to be adequately supported and empowered to play their part.

- Improving governance and stakeholder participation : Countries have adopted different modes of governance. There are generally two systems that are followed, an integrated system and a split system.

- Using funding to steer ECCE development : Strengthening domestic public financing is important for providing affordable ECCE. Since ECCE services are offered by different ministries, there must be a clear demarcation of funding and financing rules for different sectors and different ministries. Innovative financing may include earmarking resources from economic activities and other sources.

- Establishing systems for monitoring and assessing whole-of-child development . System-level action in strengthening the availability and reliability of data obtained from assessments enables efficient and timely monitoring of programmes and child developmental milestones.

- Galvanize international cooperation and solidarity . The World Conference on Early Childhood Care and Education is an opportunity to mobilize existing global, regional, and national networks to increase focus on identifying and sharing innovations, policies and practices.

Related items

- Early childhood

- Early childhood education

Other recent news

- Community and Engagement

- Honors and Awards

- Give Now

Ask the Expert: Why is a Preschool Education Important? ‘When Children Attend High-quality Pre-K Programs, They Get a Really Great Boost in Early Skills That Set Them Up for Success in Elementary School,’ Says Assistant Professor Michael Little

This is part of the monthly “Ask the Expert” series in which NC State College of Education faculty answer some of the most commonly asked questions about education.

Early childhood is a critical time when a child’s brain is highly impacted by the contexts and environments that surround them. It is for that reason that NC State College of Education Assistant Professor Michael Little, Ph.D. , says a preschool education is important for all students who are able to attend.

“Oftentimes, when children attend high-quality and effective Pre-K programs, they get a really great boost in early skills that set them up for success in elementary school,” said Little, who studies policies and programs that seek to improve early educational outcomes for students with a focus on connections between preschool and early elementary grades.

Decades of research have demonstrated the benefits of preschool, Little said, including a long-term study of an early model Pre-K program that began in the 1960s. Participants in that study, who are now middle aged, have been followed throughout their lives by researchers who have found that those who attended the preschool program demonstrated beneficial outcomes throughout their lives, including having superior health outcomes and being less likely to be incarcerated than those who did not attend preschool.

Studies on scaled up Pre-K programs, including North Carolina’s state-funded Pre-K program, also show that attendance leads to robust benefits for kids that set them up for success in early elementary school grades, Little said.

Despite these initial benefits, Little said that more can be done to help children sustain the academic gains that they make in preschool. Stronger alignment between preschool and the K-12 school system, specifically in kindergarten through third grade, can help prevent “Pre-K fadeout,” a phenomenon in which the early benefits of preschool can diminish in elementary school.

“This is a really critical challenge because, to deliver on the promise and effectiveness of Pre-K, we need to make sure that we’re sustaining the gains of Pre-K throughout elementary school and beyond,” he said. “That means coordinating and creating an aligned system of early learning that builds upon the gains that kids made in Pre-K and sustains them throughout the early grades. This is often referred to as P-3 alignment.”

Little’s own research has demonstrated that school-based preschool programs, which are located within an elementary school rather than in a separate building, could be a crucial element to improving P-3 alignment. When preschools reside in the same location as K-3 teachers, it can create conditions for educators to better collaborate and share student data in order to break down barriers that often exist between the worlds of Pre-K and K-12 learning.

Making sure that preschool and kindergarten teachers are able to communicate and create stronger transition practices from Pre-K to kindergarten can also help support P-3 alignment, Little said.

In addition to helping children to sustain academic gains, P-3 alignment also has the benefit of helping schools to achieve goals of educational equity, as children who attend state-funded preschool programs are often historically marginalized students or students from disadvantaged backgrounds.

“If the effects of Pre-K simply fade away once they enter elementary school, we’re not delivering on the promise of preschool as an equity achieving policy intervention. For us to close achievement gaps and really deliver on the promises of Pre-K, we need to ensure through P-3 alignment that the benefits of Pre-K are sustained,” Little said.

Video by Ryan Clancy

- Research and Impact

- Ask The Expert

- homepage-news

- Michael Little

More From College of Education News

Alumni Distinguished Graduate Professor of Higher Education Alyssa Rockenbach to Explore Interpartisian Friendships on College Campuses through National Center for Free Speech and Civic Engagement Fellowship

Catherine Hartman Named Assistant Professor of Community College Leadership

My Student Experience: Graduate Assistants in University Housing Make Campus Feel Like Home

Early Education Pays Off. A New Study Shows How

- Share article

The benefits of early-childhood education can take a decade or more to come into focus, but a new study in the journal Child Development suggests preschool may help prepare students for better academic engagement in high school.

Researchers at the nonprofit ChildTrends, Georgetown University, and the University of Wisconsin tracked more than 4,000 children who started kindergarten in Tulsa, Okla., public schools in 2006. Some 44 percent of the students participated in the Sooner State’s universal state-funded preschools, which include partnerships between school districts and early-learning organizations. Another 14 percent of the students had participated in federal Head Start programs, and the rest did not participate in either program.

Early benefits of preschool participation on students’ math and reading scores mostly faded away by the time students reached high school—a common fade-out problem seen for early education. But Amadon and her colleagues found that students who had participated in Tulsa’s state-funded preschool programs were more likely to attend school regularly and take more-challenging courses than those who participated in Head Start or did not receive early-childhood education.

“The fact that students were attending school more days, the fact that they were enrolling in different types of courses indicates some sort of different engagement in and commitment to their education and their schooling,” said Sara Amadon, a senior research scientist for the nonprofit ChildTrends and lead author of the study. “It didn’t translate to GPA or test scores, but, you know, we also know that GPA and test scores are just one part of the puzzle of persistence and engagement through high school. Those behavioral indicators are also really powerful predictors of graduation.”

The results come as the Biden administration continues to press for universal, publicly funded preschool for all 3- and 4-year-olds. Earlier this month, President Joe Biden signed a $1.5 trillion spending bill for fiscal 2022 that included more than $584 million in additional support for child care and early learning programs, including Head Start, Early Head Start, and the Child Care and Development Block Grants. However, the new study suggests state-supported programs may have more-stable benefits than Head Start in the long term.

Overall, students showed no significant differences in cumulative grade point averages or scores on ACT or SAT college placement exams, regardless of whether or not they participated in preschool. There were two exceptions: Native American students performed better in English/language arts on college placement exams, and Hispanic students had higher GPAs, if they attended preschool than if they had not.

Moreover, compared with children who had not attended early education, alumni of Tulsa’s universal preschools challenged themselves more academically: They were significantly more likely to take an Advanced Placement or International Baccalaureate class, and less likely to fail a high school course in general, than students who had not attended preschool. (By contrast, there was no significant difference academically for students who had participated in Head Start or no early education.)

Better attendance habits later on for preschool participants

In part, this could be because students who attended Tulsa’s universal preschools developed better attendance habits early—and kept them throughout their academic careers.

Students who had attended Tulsa’s preschools were significantly less likely to be chronically absent in high school—defined as missing 10 percent of school days or more—than their classmates who had not attended preschool. On average, preschool alumni missed 1.5 fewer days a year than those who hadn’t attended.

On average, students who had attended Head Start programs instead were also slightly less likely to miss school, but showed no other academic or engagement advantages.

Students of color who had attended preschool were particularly likely to be more engaged in school later on. For example, Hispanic students who had attended preschool attended 2.8 more school days on average in high school compared with Hispanic students who had not attended preschool or who had attended Head Start.

Amadon said the study also highlights the need for educators and school leaders to plan for additional supports for students entering school during the pandemic, who may have had less access to early-childhood education.

“When we think about the upcoming pre-K classes, [education leaders should] make sure they are giving that extra push to ensure that all students are accessing pre-K ... doing a little more outreach, especially to the neighborhoods and communities that you know have families that were hard hit by the pandemic or struggled to find child care” and early education, she said.

The study is part of an ongoing research project tracking the long-term effects of early-childhood education. The next study in the project will focus on differences in college-going among these students.

Sign Up for EdWeek Update

Edweek top school jobs.

Sign Up & Sign In

- High contrast

- Press Centre

Search UNICEF

- Early childhood education

Every child deserves access to quality early childhood education.

- Available in:

Quality pre-primary education is the foundation of a child’s journey: every stage of education that follows relies on its success. Yet, despite the proven and lifelong benefits, more than 175 million children – nearly half of all pre-primary-age children globally – are not enrolled in pre-primary education.

Nearly half of all pre-primary-age children around the world are not enrolled in preschool.

In low-income countries, the picture is bleaker, with only 1 in 5 young children enrolled. Children from poor families are the least likely to attend early childhood education programmes. For children who do have access, poorly trained educators, overcrowded and unstimulating environments, and unsuitable curricula diminish the quality of their experiences.

Failure to provide quality early childhood education limits children’s futures by denying them opportunities to reach their full potential. It also limits the futures of countries, robbing them of the human capital needed to reduce inequalities and promote peaceful, prosperous societies.

Why should universal access to pre-primary education be a global priority?

Children enrolled in at least one year of pre-primary education are more likely to develop the critical skills they need to succeed in school and less likely to repeat grades or drop out. As adults, they contribute to peaceful societies and prosperous economies. Evidence of the ways in which pre-primary education advances development exists around the world.

Yet, global disparities in enrolment persist. More than half of low- and lower-middle-income countries are not on track to ensure at least one year of quality pre-primary education for every child by 2030, as set out by the Sustainable Development Goals .

What should governments do to ensure pre-primary education for all?

1. scale up investment.

Pre-primary education provides the highest return on investment of all education sub-sectors. Yet, it receives the smallest share of government expenditure compared to primary, secondary and tertiary education.

2. Progressively grow the pre-primary system, while improving quality

Efforts to scale up access to pre-primary education should not come at the expense of quality. Quality is the sum of many parts, including teachers, families, communities, resources, and curricula.

Without adequate safeguards for quality, expansion efforts can intensify education inequities. It is only by investing in quality as education systems grow – not after – that governments can expand access and maintain quality.

9.3 million new teachers are needed to achieve universal pre-primary education

Only 50% of pre-primary teachers in low-income countries are trained, only 5% of pre-primary teachers globally work in low-income countries, 3. ensure vulnerable populations are not the last to benefit.

Access to early childhood education has been slow and inequitable, both across and within countries. Worldwide, vulnerable children are disproportionately excluded from quality pre-primary education – even though it can have the greatest impact on them.

To ensure no child is left behind, Governments should adopt policies that commit to universal pre-primary education and prioritize the poorest and hardest-to-reach children at the start of the road to universality, not the end.

*Early childhood education

The richest children are 7 times more likely to attend ECE* programmes than the poorest

Children of mothers with secondary education are 5 times more likely to attend ECE* programmes

Children in urban areas are 1.5 times more likely to attend ECE* programmes than those in rural areas

Equitable attendance in ECE* programmes exists between girls and boys

What does UNICEF call for to achieve universal pre-primary education?

What does unicef do to advance pre-primary education.

UNICEF works to give every child a fair start in education. We support pre-primary education in 129 countries around the globe by:

- Building political commitment to quality pre-primary education through evidence generation, advocacy and communication

- Strengthening policies and advocating for increased public financing for pre-primary education

- Bolstering national capacity to plan and implement quality pre-primary education at scale

- Enhancing the quality of pre-primary programmes by supporting the development of quality standards, curricular frameworks, teacher training packages and more

- Collecting data and generating evidence for innovative approaches that deliver quality pre-primary education for vulnerable children

- Delivering conflict-sensitive early childhood education and psychosocial support to young children and their families in humanitarian situations

More from UNICEF

Early childhood education for all.

It is time for a world where all children enter school equipped with the skills they need to succeed.

175 million children are not enrolled in pre-primary education – UNICEF

Early childhood education has a new MOOC

A new Massive Open Online Course sets out to give all children the best start in education

5 fun ideas for learning through play

Eat, play, love: Playful ways to help build your child’s brain

Better Early Learning and Development at Scale

Build to last: a framework in support of universal quality pre-primary education, blogs on the pilot countries’ belds experiences: ghana , lesotho , the kyrgyz republic, sao tome and principe.

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

A top researcher says it's time to rethink our entire approach to preschool

Anya Kamenetz

Dale Farran has been studying early childhood education for half a century. Yet her most recent scientific publication has made her question everything she thought she knew.

"It really has required a lot of soul-searching, a lot of reading of the literature to try to think of what were plausible reasons that might account for this."

And by "this," she means the outcome of a study that lasted more than a decade. It included 2,990 low-income children in Tennessee who applied to free, public prekindergarten programs. Some were admitted by lottery, and the others were rejected, creating the closest thing you can get in the real world to a randomized, controlled trial — the gold standard in showing causality in science.

The Tennessee Pre-K Debate: Spinach Vs. Easter Grass

Farran and her co-authors at Vanderbilt University followed both groups of children all the way through sixth grade. At the end of their first year, the kids who went to pre-K scored higher on school readiness — as expected.

But after third grade, they were doing worse than the control group. And at the end of sixth grade, they were doing even worse. They had lower test scores, were more likely to be in special education, and were more likely to get into trouble in school, including serious trouble like suspensions.

"Whereas in third grade we saw negative effects on one of the three state achievement tests, in sixth grade we saw it on all three — math, science and reading," says Farran. "In third grade, where we had seen effects on one type of suspension, which is minor violations, by sixth grade we're seeing it on both types of suspensions, both major and minor."

That's right. A statewide public pre-K program, taught by licensed teachers, housed in public schools, had a measurable and statistically significant negative effect on the children in this study.

Farran hadn't expected it. She didn't like it. But her study design was unusually strong, so she couldn't easily explain it away.

"This is still the only randomized controlled trial of a statewide pre-K, and I know that people get upset about this and don't want it to be true."

Why it's a bad time for bad news

It's a bad time for early childhood advocates to get bad news about public pre-K. Federally funded universal prekindergarten for 3- and 4-year-olds has been a cornerstone of President Biden's social agenda, and there are talks about resurrecting it from the stalled-out "Build Back Better" plan. Preschool has been expanding in recent years and is currently publicly funded to some extent in 46 states. About 7 in 10 4-year-olds now attend some kind of academic program.

This enthusiasm has rested in part on research going back to the 1970s. Nobel Prize-winning economist James Heckman, among others, showed substantial long-term returns on investment for specially designed and carefully implemented programs.

To put it crudely, policymakers and experts have touted for decades now that if you give a 4-year-old who is growing up in poverty a good dose of story time and block play, they'll be more likely to grow up to become a high-earning, productive citizen.

What went wrong in Tennessee

No study is the last word. The research on pre-K continues to be mixed. In May 2021, a working paper (not yet peer reviewed) came out that looked at Boston's pre-K program. The study was a similar size to Farran's, used a similar quasi-experimental design based on random assignment, and also followed up with students for years. This study found that the preschool kids had better disciplinary records and were much more likely to graduate from high school, take the SATs and go to college, though their test scores didn't show a difference.

Farran believes that, with a citywide program, there's more opportunity for quality control than in her statewide study. Boston's program spent more per student, and it also was mixed-income, whereas Tennessee's program is for low-income kids only.

So what went wrong in Tennessee? Farran has some ideas — and they challenge almost everything about how we do school. How teachers are prepared, how programs are funded and where they are located. Even something as simple as where the bathrooms are.

In short, Farran is rethinking her own preconceptions, which are an entire field's preconceptions, about what constitutes quality pre-K.

Do kids in poverty deserve the same teaching as rich kids?

"One of the biases that I hadn't examined in myself is the idea that poor children need a different sort of preparation from children of higher-income families."

She's talking about drilling kids on basic skills. Worksheets for tracing letters and numbers. A teacher giving 10-minute lectures to a whole class of 25 kids who are expected to sit on their hands and listen, only five of whom may be paying any attention.

A Harsh Critique Of Federally Funded Pre-K

"Higher-income families are not choosing this kind of preparation," she explains. "And why would we assume that we need to train children of lower-income families earlier?"

Farran points out that families of means tend to choose play-based preschool programs with art, movement, music and nature. Children are asked open-ended questions, and they are listened to.

5 Proven Benefits Of Play

This is not what Farran is seeing in classrooms full of kids in poverty, where "teachers talk a lot, but they seldom listen to children." She thinks that part of the problem is that teachers in many states are certified for teaching students in prekindergarten through grade 5, or sometimes even pre-K-8. Very little of their training focuses on the youngest learners.

So another major bias that she's challenging is the idea that teacher certification equals quality. "There have been three very large studies, the latest one in 2018, which are not showing any relationship between quality and licensure."

Putting a bubble in your mouth

In 2016, Farran published a study based on her observations of publicly funded Tennessee pre-K classrooms similar to those included in this paper. She found then that the largest chunk of the day was spent in transition time. This means simply moving kids around the building.

Partly this is an architectural problem. Private preschools, even home-based day cares, tend to be laid out with little bodies in mind. There are bathrooms just off the classrooms. Children eat in, or very near, the classroom, too. And there is outdoor play space nearby with equipment suitable for short people.

Putting these same programs in public schools can make the whole day more inconvenient.

"So if you're in an older elementary school, the bathroom is going to be down the hall. You've got to take your children out, line them up and then they wait," Farran says. "And then, if you have to use the cafeteria, it's the same thing. You have to walk through the halls, you know: 'Don't touch your neighbor, don't touch the wall, put a bubble in your mouth because you have to be quiet.' "

One of Farran's most intriguing conjectures is that this need for control could explain the extra discipline problems seen later on in her most recent study.

"I think children are not learning internal control. And if anything, they're learning sort of an almost allergic reaction to the amount of external control that they're having, that they're having to experience in school."

In other words, regularly reprimanding kids for doing normal kid stuff at 4 years old, even suspending them, could backfire down the road as children experience school as a place of unreasonable expectations.

We know from other research that the control of children's bodies at school can have disparate racial impact. Other studies have suggested that Black children are disciplined more often in preschool, as they are in later grades. Farran's study, where 70% of the kids were white, found interactions between race, gender, and discipline problems, but no extra effect of attending preschool was detected.

Preschool Suspensions Really Happen And That's Not OK With Connecticut

Where to go from here.

The United States has a child care crisis that COVID-19 both intensified and highlighted. Progressive policymakers and advocates have tried for years to expand public support for child care by "pushing it down" from the existing public school system, using the teachers and the buildings.

Farran praises the direction that New York City, for one, has taken instead: a "mixed-delivery" program with slots for 3- and 4-year-olds. Some kids attend free public preschool in existing nonprofit day care centers, some in Head Start programs and some in traditional schools.

But the biggest lesson Farran has drawn from her research is that we've simply asked too much of pre-K, based on early results from what were essentially showcase pilot programs. "We tend to want a magic bullet," she says.

"Whoever thought that you could provide a 4-year-old from an impoverished family with 5 1/2 hours a day, nine months a year of preschool, and close the achievement gap, and send them to college at a higher rate?" she asks. "I mean, why? Why do we put so much pressure on our pre-K programs?"

We might actually get better results, she says, from simply letting little children play.

Education: Kindergarten Matters!

Can kindergarten be that important.

Posted August 1, 2010

Did you read the article in the New York Times last week discussing research that demonstrated the clear importance of kindergarten to later success? It was a real eye opener for many people who are involved in public education and real confirmation for those of us who have advocated for true reform in an American public-education system that has been in steady decline for years. And, in an odd sort of way, it confirms the wisdom of the 1988 book, All I Really Need to Know I Learned in Kindergarten .

Three findings were most compelling. First, children who learned more in kindergarten, compared to similar students, were less likely to be single parents, went to college in higher numbers, had higher incomes, and had retirement plans. What was most striking about these findings was that they stand in sharp contract to other research involving test scores indicating that quality early education had a diminishing effect on students as they progress through elementary and high school.

The second important finding was that the quality of teachers has a direct impact on the long-term success of students, not just on test scores. This result is one of those "We didn't need science to tell us the obvious" observations, but it does defang arguments made from theory, conjecture, anecdote, or ideology suggesting otherwise. Class size had some effect as did the socioeconomic status of students in classes (the higher, the better all students performed). But the data demonstrated unequivocally that better teachers had the most significant influence on their students in adulthood. The researchers estimated that, based on the differences in adult income of the different classes of kindergarteners, exceptional teachers are worth $320,000 a year. That dollar figure doesn't include other personal, economic, and social gains such as improved health, more stable marriages, better parenting , and reduced crime . And these gains are likely to increase exponentially with each succeeding generation.

The third finding, though less clear, is that kindergarteners are gaining something very powerful from quality early education. The researchers didn't speculate on what those benefits are, but some obvious ones are worth considering. These early school experiences may instill a belief in the value of education and a joy (or at least an appreciation) for learning. They may build students' confidence in their competence and their ability to learn. These students may learn important life skills, as the article suggests, such as motivation , discipline, patience, and persistence, all qualities that aren't directly assessed by testing.

Some provocative inferences can be drawn from these findings. These more ethereal gains from quality early education aren't resilient enough to overcome the debilitating environment of bad schools and result in higher test scores. Yet, they are hardy enough to resist the discouraging culture and experiences of bad schools and reemerge in adulthood with, as the research shows, startling benefits.

Several lessons emerge from this article. First, testing isn't a valid measure of educational attainment and long-term benefit. As has often been reported, children who attend quality early education, such Head Start, suffer from a "fade out effect" in which any gains that are made tend to disappear, based on test scores, as children progress through school. Yet, consistent with my indictment of testing, the research found that there were clear benefits to children who attend quality kindergarten that are realized in adulthood. As the lead researcher noted, "We don't really care about test scores. We care about adult outcomes." Could the obvious have been stated any more clearly? Doesn't this statement shoot holes in the use of testing as the end-all, be-all of Race to the Top as a means of assessing students' academic benefits and progress? What it does clearly demonstrate is that our current battery of academic-assessment tests simply don't measure what we need them to measure and, as a result, should be reconsidered.

The second lesson is that teachers matter. As such, they deserve not only our respect -- sadly, teachers are typically considered to be pretty far down on the career food chain -- but also much better pay. Thankfully, as noted in the New York Times article, school districts around the country are showing signs of getting this message and starting to pay teachers accordingly (and teachers unions are getting the message that contracts based on seniority and tenure just won't fly these days).

The final, and most important, lesson is that quality early education makes a huge difference. And quality early education is a very good investment. We spend billions upon billions of dollars struggling to deal with problems after the fact, such as lack of job skills, ill health, high unemployment, drug abuse , broken families, and high crime rates, all of which result partly from poor education, with little to show for those dollars spent. Why not prevent these enormous social problems by ensuring high-quality early (and later) education. Imagine the economic gains when you multiply that $320,000 per class by every kindergarten class of disadvantaged students in America by the decades ahead of us. Based on my very rough calculations, it is safe to say that is far into the trillions of dollars.

I don't want to get into an argument with deficit hawks or libertarians about how to pay for education reforms to bolster early education. But it seems obvious that, based on this data, a well-used investment in children, teachers, and schools now can have massive individual, economic, and social benefits twenty year later and beyond.

Jim Taylor, Ph.D. , teaches at the University of San Francisco.

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Online Therapy

- United States

- Brooklyn, NY

- Chicago, IL

- Houston, TX

- Los Angeles, CA

- New York, NY

- Portland, OR

- San Diego, CA

- San Francisco, CA

- Seattle, WA

- Washington, DC

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Self Tests NEW

- Therapy Center

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

At any moment, someone’s aggravating behavior or our own bad luck can set us off on an emotional spiral that threatens to derail our entire day. Here’s how we can face our triggers with less reactivity so that we can get on with our lives.

- Emotional Intelligence

- Gaslighting

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

Why Is Early Childhood Education Important for Children?

Early childhood education (ECE) plays a vital role in children’s development. It provides a strong foundation for later academic, social, and emotional growth.

During these formative years, a child's brain is like a sponge, absorbing new information and experiences at a remarkable rate. According to VeryWellMind, this critical period of brain development brings rapid cognitive, emotional, and physical growth for a child. It paves the way for greater learning capabilities.

Early childhood education programs and ECE educators prove invaluable during this critical time, offering structured, creative environments to nurture the developing child. Engaging in well-designed ECE programs equips children at this stage with the essential tools and skills they will need throughout their academic journey and life.

Cognitive Development in Early Childhood Education

It is important to provide children with stimulating environments and projects to enhance their cognitive abilities during their preschool years.

A key benefit of early childhood education is the support it provides to prepare children for entering kindergarten. Many ECE programs teach children to reason by incorporating problem-solving tasks, which helps to develop their critical thinking skills.

Effective childhood education also encourages children to explore their surroundings, which fosters curiosity and a sense of wonder. Imaginative play, such as pretending to be a doctor or a chef, allows a child to exercise creativity and develop an imagination.

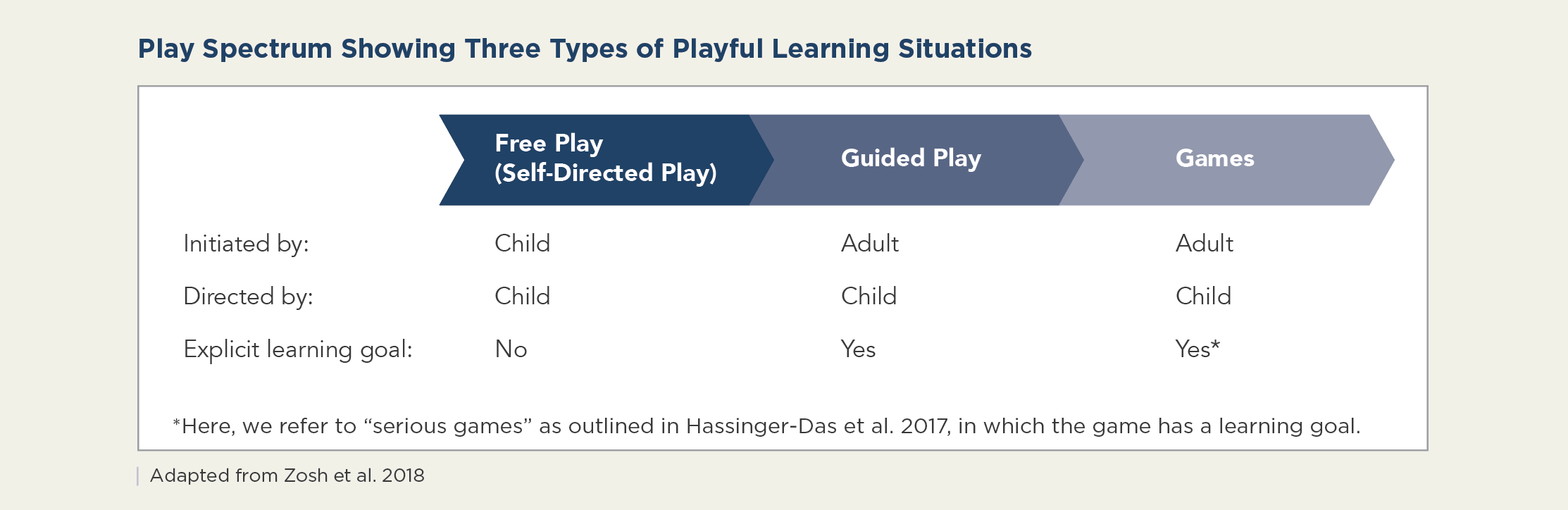

In fact, a great deal of early learning takes place when young students are involved in different forms of play:

- Hands-on activities: These activities involve sensory play, art projects, science experiments, and construction using building blocks. Such activities encourage exploration, creativity, and an understanding of basic scientific concepts.

- Storytelling, reading, music, and dance: Reading and storytelling foster language skills, comprehension, and a love for literature. They also enhance imagination and listening abilities, while activities like singing, dancing, and playing simple musical instruments help young students to develop motor skills, rhythm, and self-expression.

- Group projects and collaborative activities: Working together on projects teaches kids skills such as cooperation, problem-solving, and teamwork.

- Exploration of new cultures and languages: Activities that introduce children to different cultures, languages, and customs broaden their understanding of the world and promote inclusion.

- Technology games and apps: Integrating age-appropriate technology like educational apps and interactive games during playtime enhances learning and tech literacy, which is a practical skill in today’s digital age.

Laying the Foundations for Literacy

A child’s early years lay the groundwork for more advanced literacy skills. During early childhood education, young students develop pre-reading abilities as they practice letter recognition and phonics, as well as building their vocabulary. Even at this young age, children are exposed to a rich language environment, which helps them learn how to communicate.

Long before they enter kindergarten, young students can begin to develop early math knowledge, such as counting, sorting, and recognizing shapes. This rudimentary knowledge supplies children with the necessary tools to sustain themselves academically as they eventually progress through school.

Enhancing Social and Emotional Growth

Social development is closely related to cognitive development. Young students who interact with their peers, share ideas, and collaborate on projects develop valuable social skills, including empathy, cooperation, and conflict resolution.

These social interactions further enhance cognitive abilities and contribute to children’s overall emotional well-being.

Recognizing Diverse Learning Needs

Quality early childhood care acknowledges young students as individuals whose cognitive development is as unique as their personalities. Educators must understand the importance of creating inclusive environments that cater to the various learning needs of each child.

As a result, teachers should provide differentiated instruction, adapting their teaching methods and lesson plans to suit the diverse learning styles of their students. Personalized teaching approaches ensure all children have the opportunity to thrive and reach their full cognitive potential.

Social and Emotional Growth in Early Childhood

An early childhood education program should provide a safe, nurturing environment for young students to develop their social and emotional skills. This type of environment encourages interactions with peers, teachers, and caregivers to build meaningful social connections and relationships. By integrating collaborative play in early childhood education, young students also learn to share, take turns, and cooperate effectively, which are among the biggest challenges for young students to learn.

Early childhood educators can further promote students’ emotional growth by teaching them how to identify and express their emotions in a healthy manner. This way, they learn how to manage their feelings and resolve conflicts peacefully.

Acquiring the ability to manage emotions and resolve conflicts help contribute to children’s emotional intelligence, a necessity for successfully navigating relationships and developing strong social bonds at any age.

Key Factors in Early Childhood Social and Emotional Growth

Various factors are involved in a student's social, emotional, and academic growth. They include both direct and indirect influences that collectively shape a child's growth.

From the level of nurturing at home to the social and educational experiences at school, nearly every aspect of kids' lives guides them either closer to or further away from becoming well-rounded and capable individuals. Recognizing this intricate interplay is of the utmost importance for caregivers and early childhood educators.

Building Secure Relationships

Children’s social abilities are greatly influenced by the quality of the relationships they forge with early childhood educators such as preschool teachers. These relationships serve as the basis for a child’s sense of security and emotional well-being.

A child who feels supported and cared for is more inclined to develop trust, empathy, and effective communication. The security offered through their relationships helps to create a positive self-image and gives children resilience to overcome social challenges later on.

Furthermore, healthy relational dynamics allow children to practice cooperation, conflict resolution, and emotional regulation. It builds a strong foundation for their future interpersonal interactions and emotional health.

The Role of Free Play in a Child’s Life and Growth

Social and emotional growth are also fueled by participating in free play. “Free play” refers to recreational time, during which young people engage their imaginations. Free play allows them to explore their emotions, develop their creativity, and practice social interactions.

Whether they’re building a tower with blocks or pretending to be superheroes, kids learn important social skills such as negotiation, compromise, and empathy by playing.

The Importance of ECE Programs and ECE Staff

The importance of ECE programs in social and emotional growth cannot be overstated. These programs often incorporate storytelling, role-playing, and group discussions, through which young people learn how to recognize and understand their emotions.

However, a program of early childhood education is only as helpful as the adults who run it. The best early childhood educators demonstrate passion, creativity, and understanding in their work with young people.

These professionals bear the responsibility of supporting their students' social and emotional development during early childhood education. They must create a positive and inclusive classroom environment where everyone can feel valued and respected during their early childhood.

An early childhood educator or preschool teacher may accomplish this goal by serving as a model of positive behavior, and providing guidance during conflicts. Teachers can also encourage empathy to help children develop healthy relationships.

Studies indicate that children with well-developed social and emotional abilities during their early years tend to achieve greater academic success as they grow older. Similarly, these young people tend to experience fewer mental health concerns.

Social and emotional skills allow young students to maintain healthy relationships with each other and their families, manage stress, cope with challenges, and make responsible decisions.

The Role of Early Childhood Education in Preparing for School

Early childhood education programs serve as a bridge between home life with parental involvement and the more structured world of elementary school with teachers. Childcare centers and preschools provide environments that mirror the classroom to encourage adaptability and prepare children for future academic challenges.

These early educational settings also play a crucial role by imparting various skills necessary for healthy development. Young kids become accustomed to adhering to routines while they enhance their abilities to listen and follow instructions.

In addition, children learn to cooperate with others by actively participating in group activities. This early exposure to structured learning cultivates critical thinking and collaboration, which are essential for their proper development and lifelong learning.

Early childhood education also places a strong emphasis on developing self-help skills. Mastering tasks like getting dressed, independently using the restroom, and maintaining good hygiene gives children a sense of independence and self-reliance.

Moreover, a child’s education is fundamental in building confidence and autonomy. Early childhood education equips students with the self-assurance required to navigate the more formal and demanding environment of schooling. Such holistic development ensures children are ready – academically, emotionally, and socially – to transition to the next stage of life.

The Long-Term Benefits of Early Childhood Education

According to Learning Policy Institute, studies consistently demonstrate that children who are provided with high-quality early childhood education reap enduring benefits that last for years to come. Additionally, Learning Policy Institute notes that that children who have attended preschool or early childhood programs demonstrate better academic performance throughout their schooling years when compared to those who did not.

Early childhood education has also been linked to improved socio-economic outcomes in adulthood, according to Gray Group International. Evidently, individuals who receive a high-quality early education are more likely to graduate from high school, seek a degree, and pursue a career.

Ultimately, early childhood education can have a long-lasting, positive impact on a child's overall well-being and future endeavors.

Is Early Childhood Education the Right Path for You?

Early childhood educators help shape the lives of many young learners. They serve as a guidepost for parents and families during one of the most impactful times in children’s lives.

If you're inspired to begin your own ECE journey, consider looking into American Public University's early childhood education associate degree program. In this degree program, students explore the latest in educational practices and child development theories. Visit our Early Childhood Care and Education program page to explore the curriculum.

- Call: 877-755-2787

- Email: [email protected]

- Chat: Live Chat

Main: (623) 556-2179 Enrollment: (602) 761-0826 check school Calendar --> 15688 W. Acoma Rd. Surprise, AZ 85379

The benefits of a kindergarten education: why it is important to start school early.

Starting school early provides children with the essential skills and knowledge to succeed in their academic careers. Kindergarten is the first step toward children realizing their potential and reaching their goals.

Benefits of Kindergarten

One of the main benefits of kindergarten is that it provides children with the opportunity to learn how to interact with others in a social setting. By having regular classroom activities, children develop an understanding of basic concepts that will help them succeed.

Importance of Kindergarten

The importance of kindergarten centers around the fact that it allows children to explore and grow academically, socially, and emotionally through play-based learning activities like music time or outdoor playtime. Additionally, since many kindergarten classrooms are highly interactive environments where teachers use technology such as computers or tablets for teaching purposes, students gain valuable tech skills that can also be beneficial later in life.

Parents’ Goals for Kindergarten Students

Parents’ goals for kindergarten students should be specific and might include:

- mastering basic concepts, such as numbers and letters

- developing positive relationships with classmates

- engaging in meaningful conversations

- building self-confidence

- gaining independence

- mastering basic problem-solving skills

What Are the Benefits of Early Childhood Education?

So, what are the benefits of early childhood education? Early childhood education helps to develop critical thinking skills from a young age by providing opportunities such as problem-solving activities or games that require independent decisions or collaboration between peers. It also encourages creativity through art projects or experiments to promote imagination and innovation. Early childhood education also teaches essential communication skills.