- Skip to content

- Skip to main navigation

- Skip to 1st column

- Skip to 2nd column

Global Policy Forum

- Board Members

- Support GPF

- GPF Partners

- Annual Reports and Statutes (GPF Europe)

- Contact and Disclaimer

- Publications

- Publications in German

- Upcoming Events

- Past Events

- Events in Germany

- General Information on Internships

- Internship Application

A Closer Look: Cases of Globalization

| Source: wikipedia.org/Ken Banks |

Globalization expands and accelerates the movement and exchange of ideas and commodities over vast distances. It is common to discuss the phenomenon from an abstract, global perspective, but in fact globalization's most important impacts are often highly localized. This page explores the various manifestations of interconnectedness in the world, noting how globalization affects real people and places.

Articles and Documents

Chinese imports and contraband make bolivia's textile trade a casualty of globalization (july 6, 2012).

Domestic manufacturing in Bolivia has been crushed by the influx of cheap foreign goods, mainly from China. Bolivian products cannot compete in the global market because of the small scale production, the strict labor law which keeps labor cost high, and the frequent political unrest which hurt competitiveness by raising costs. The Bolivian economy is reliant on raw material extraction, and its trade deficit keeps widening. Although the government is making an effort to raise tariffs and create state-owned companies to save jobs, globalization seems to have caused more bad than good in Bolivia. (Associated Press)

Is France on Course to Bid Adieu to Globalization? (July 21, 2011)

Many in France are blaming globalization for causing high youth unemployment and a stagnated, post recessionary economy. With the 2012 presidential election approaching, the theme of “deglobalization” appears to be growing in popularity due to its nationalistic appeal. Left-wing candidates, including member of Parliament Arnaud Montebourg, are advocating European-based protectionism, and saying that “globalization” has caused France’s high rates of youth unemployment, destroyed natural resources, and made France vulnerable to the fluctuations of interconnected financial markets. While Montebourg is not a likely front-runner for the presidency, his surprising popularity has highlighted the French peoples’ disillusionment and has prompted a discussion of globalization. Ideally, this will “force politicians to work harder on their answers”, and they will work to improve France’s economic recovery plans and their role in a globalized system. (YaleGlobal Online)

350 Movement Video from Bolivia's Climate Summit (April 22, 2010)

Immigrants now see better prospects back home (december 8, 2009), the human effect of globalization (august 30, 2009), following the trail of toxic trash (august 17, 2009), will the crisis reverse global migration (july 17, 2009), in many business schools, the bottom line is in english (april 10, 2007), globalization and child labor: the cause can also be a cure (march 13, 2007), landless workers movement: the difficult construction of a new world (september 29, 2006), for african cotton farmers, more crops equal less pay (august 15, 2006), meet the losers of globalization (march 8, 2006), thanks to corporations instead of democracy we get baywatch (september 13, 2005), global health priorities – priorities of the wealthy (april 22, 2005), guatemala: supermarket giants crush farmers (december 28, 2004).

This article looks at the effects of economic liberalization in Latin America's food retailing system and identifies small scale farmers as the "losers of globalization." Corporate transformations of the regional food sector and its failed trickle-down economics have not generated wealth but rather increased the social inequalities in the region, forcing smaller growers to migrate. ( New York Times )

Campesinos vs Oil Industry: Bolivia Takes On Goliath of Globalization (December 5, 2004)

Privatizations: the end of a cycle of plundering (november 1, 2004), globalization: europe's wary embrace (november 1, 2004), latin american indigenous movements in the context of globalization (october 11, 2004), mixed blessings of the megacities (september 24, 2004), dominican republic: us trade pact fails pregnant women - cafta fails to protect against rampant job discrimination (april 22, 2004), workers face uphill battle on road to globalization (january 27, 2004), money for nothing and calls for free (february 17, 2004), the next great wall (january 19, 2004).

This article examines the growth of geographical, physical and, increasingly, digital immigration barriers to the free movement of people between rich and poor countries. ( TomDispatch.com )

Areas of Work

Special Topics

Archived Sections

More from gpf.

FAIR USE NOTICE : This page contains copyrighted material the use of which has not been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. Global Policy Forum distributes this material without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. We believe this constitutes a fair use of any such copyrighted material as provided for in 17 U.S.C § 107. If you wish to use copyrighted material from this site for purposes of your own that go beyond fair use, you must obtain permission from the copyright owner.

About Stanford GSB

- The Leadership

- Dean’s Updates

- School News & History

- Commencement

- Business, Government & Society

- Centers & Institutes

- Center for Entrepreneurial Studies

- Center for Social Innovation

- Stanford Seed

About the Experience

- Learning at Stanford GSB

- Experiential Learning

- Guest Speakers

- Entrepreneurship

- Social Innovation

- Communication

- Life at Stanford GSB

- Collaborative Environment

- Activities & Organizations

- Student Services

- Housing Options

- International Students

Full-Time Degree Programs

- Why Stanford MBA

- Academic Experience

- Financial Aid

- Why Stanford MSx

- Research Fellows Program

- See All Programs

Non-Degree & Certificate Programs

- Executive Education

- Stanford Executive Program

- Programs for Organizations

- The Difference

- Online Programs

- Stanford LEAD

- Seed Transformation Program

- Aspire Program

- Seed Spark Program

- Faculty Profiles

- Academic Areas

- Awards & Honors

- Conferences

Faculty Research

- Publications

- Working Papers

- Case Studies

Research Hub

- Research Labs & Initiatives

- Business Library

- Data, Analytics & Research Computing

- Behavioral Lab

Research Labs

- Cities, Housing & Society Lab

- Golub Capital Social Impact Lab

Research Initiatives

- Corporate Governance Research Initiative

- Corporations and Society Initiative

- Policy and Innovation Initiative

- Rapid Decarbonization Initiative

- Stanford Latino Entrepreneurship Initiative

- Value Chain Innovation Initiative

- Venture Capital Initiative

- Career & Success

- Climate & Sustainability

- Corporate Governance

- Culture & Society

- Finance & Investing

- Government & Politics

- Leadership & Management

- Markets and Trade

- Operations & Logistics

- Opportunity & Access

- Technology & AI

- Opinion & Analysis

- Email Newsletter

Welcome, Alumni

- Communities

- Digital Communities & Tools

- Regional Chapters

- Women’s Programs

- Identity Chapters

- Find Your Reunion

- Career Resources

- Job Search Resources

- Career & Life Transitions

- Programs & Services

- Career Video Library

- Alumni Education

- Research Resources

- Volunteering

- Alumni News

- Class Notes

- Alumni Voices

- Contact Alumni Relations

- Upcoming Events

Admission Events & Information Sessions

- MBA Program

- MSx Program

- PhD Program

- Alumni Events

- All Other Events

- Operations, Information & Technology

- Organizational Behavior

- Political Economy

- Classical Liberalism

- The Eddie Lunch

- Accounting Summer Camp

- Videos, Code & Data

- California Econometrics Conference

- California Quantitative Marketing PhD Conference

- California School Conference

- China India Insights Conference

- Homo economicus, Evolving

- Political Economics (2023–24)

- Scaling Geologic Storage of CO2 (2023–24)

- A Resilient Pacific: Building Connections, Envisioning Solutions

- Adaptation and Innovation

- Changing Climate

- Civil Society

- Climate Impact Summit

- Climate Science

- Corporate Carbon Disclosures

- Earth’s Seafloor

- Environmental Justice

- Operations and Information Technology

- Organizations

- Sustainability Reporting and Control

- Taking the Pulse of the Planet

- Urban Infrastructure

- Watershed Restoration

- Junior Faculty Workshop on Financial Regulation and Banking

- Ken Singleton Celebration

- Marketing Camp

- Quantitative Marketing PhD Alumni Conference

- Presentations

- Theory and Inference in Accounting Research

- Stanford Closer Look Series

- Quick Guides

- Core Concepts

- Journal Articles

- Glossary of Terms

- Faculty & Staff

- Researchers & Students

- Research Approach

- Charitable Giving

- Financial Health

- Government Services

- Workers & Careers

- Short Course

- Adaptive & Iterative Experimentation

- Incentive Design

- Social Sciences & Behavioral Nudges

- Bandit Experiment Application

- Conferences & Events

- Get Involved

- Reading Materials

- Teaching & Curriculum

- Energy Entrepreneurship

- Faculty & Affiliates

- SOLE Report

- Responsible Supply Chains

- Current Study Usage

- Pre-Registration Information

- Participate in a Study

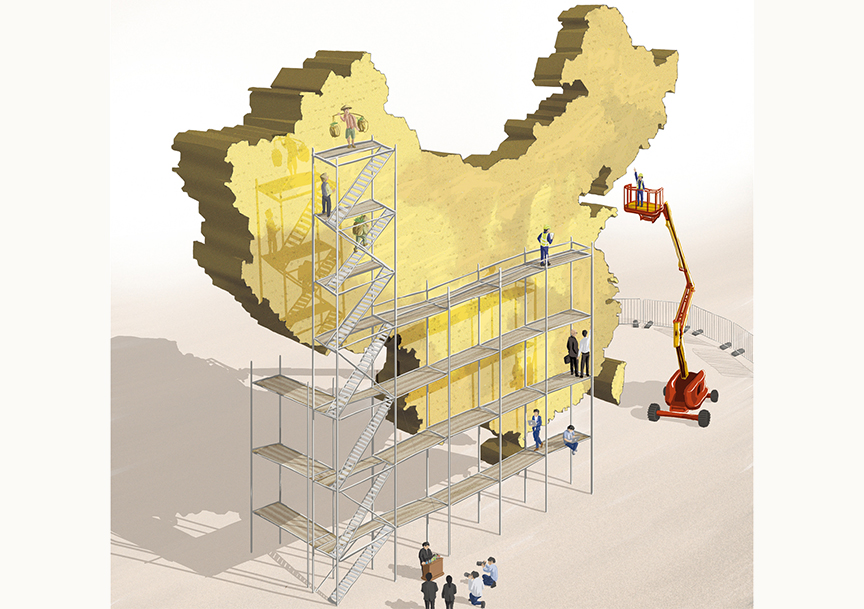

Xiaomi’s Globalization Strategy and Challenges

Xiaomi, the Chinese smartphone company founded in 2010, had quickly become an industry leader in the Chinese market. By 2016 it had started to expand internationally, and this case lays out the company’s globalization strategies and challenges moving forward. Hugo Barra, a top Android executive, had left Google a few years earlier to lead Xiaomi’s international growth. Xiaomi’s founder and CEO, Lei Jun, said the company’s ultimate goal was “making good but cheap things,” a low pricing strategy that had succeeded in China. The company sold over 70 million mobile phones in 2015—while aggressively building out a robust ecosystem. However, Xiaomi had expected to sell 80 to 100 million units that year; it was facing a declining domestic market and increased competition. Therefore, international expansion had become an important part of the company’s overall strategy.

But expanding to other countries would be a challenging road. For one, it would take considerable time and effort to tailor the company’s Android-based MIUI operating system for diversified markets—and obtain market-access qualifications. Xiaomi’s patent portfolio was thin compared to those of large competitors, and it ran the risk of lawsuits from companies that held patent rights in the countries it wanted to enter. Other challenges included building out sales channels, output capacity, and cross-culture management development. Xiaomi’s international plan included ten countries in Asia, Europe, and Latin America. The next year or two would be critical for Xiaomi—and it needed to make the right strategic decisions to succeed in its globalization efforts.

Learning Objective

- Priorities for the GSB's Future

- See the Current DEI Report

- Supporting Data

- Research & Insights

- Share Your Thoughts

- Search Fund Primer

- Affiliated Faculty

- Faculty Advisors

- Louis W. Foster Resource Center

- Defining Social Innovation

- Impact Compass

- Global Health Innovation Insights

- Faculty Affiliates

- Student Awards & Certificates

- Changemakers

- Dean Jonathan Levin

- Dean Garth Saloner

- Dean Robert Joss

- Dean Michael Spence

- Dean Robert Jaedicke

- Dean Rene McPherson

- Dean Arjay Miller

- Dean Ernest Arbuckle

- Dean Jacob Hugh Jackson

- Dean Willard Hotchkiss

- Faculty in Memoriam

- Stanford GSB Firsts

- Class of 2024 Candidates

- Certificate & Award Recipients

- Dean’s Remarks

- Keynote Address

- Teaching Approach

- Analysis and Measurement of Impact

- The Corporate Entrepreneur: Startup in a Grown-Up Enterprise

- Data-Driven Impact

- Designing Experiments for Impact

- Digital Business Transformation

- The Founder’s Right Hand

- Marketing for Measurable Change

- Product Management

- Public Policy Lab: Financial Challenges Facing US Cities

- Public Policy Lab: Homelessness in California

- Lab Features

- Curricular Integration

- View From The Top

- Formation of New Ventures

- Managing Growing Enterprises

- Startup Garage

- Explore Beyond the Classroom

- Stanford Venture Studio

- Summer Program

- Workshops & Events

- The Five Lenses of Entrepreneurship

- Leadership Labs

- Executive Challenge

- Arbuckle Leadership Fellows Program

- Selection Process

- Training Schedule

- Time Commitment

- Learning Expectations

- Post-Training Opportunities

- Who Should Apply

- Introductory T-Groups

- Leadership for Society Program

- Certificate

- 2024 Awardees

- 2023 Awardees

- 2022 Awardees

- 2021 Awardees

- 2020 Awardees

- 2019 Awardees

- 2018 Awardees

- Social Management Immersion Fund

- Stanford Impact Founder Fellowships and Prizes

- Stanford Impact Leader Prizes

- Social Entrepreneurship

- Stanford GSB Impact Fund

- Economic Development

- Energy & Environment

- Stanford GSB Residences

- Environmental Leadership

- Stanford GSB Artwork

- A Closer Look

- California & the Bay Area

- Voices of Stanford GSB

- Business & Beneficial Technology

- Business & Sustainability

- Business & Free Markets

- Business, Government, and Society Forum

- Second Year

- Global Experiences

- JD/MBA Joint Degree

- MA Education/MBA Joint Degree

- MD/MBA Dual Degree

- MPP/MBA Joint Degree

- MS Computer Science/MBA Joint Degree

- MS Electrical Engineering/MBA Joint Degree

- MS Environment and Resources (E-IPER)/MBA Joint Degree

- Academic Calendar

- Clubs & Activities

- LGBTQ+ Students

- Military Veterans

- Minorities & People of Color

- Partners & Families

- Students with Disabilities

- Student Support

- Residential Life

- Student Voices

- MBA Alumni Voices

- A Week in the Life

- Career Support

- Employment Outcomes

- Cost of Attendance

- Knight-Hennessy Scholars Program

- Yellow Ribbon Program

- BOLD Fellows Fund

- Application Process

- Loan Forgiveness

- Contact the Financial Aid Office

- Evaluation Criteria

- GMAT & GRE

- English Language Proficiency

- Personal Information, Activities & Awards

- Professional Experience

- Letters of Recommendation

- Optional Short Answer Questions

- Application Fee

- Reapplication

- Deferred Enrollment

- Joint & Dual Degrees

- Entering Class Profile

- Event Schedule

- Ambassadors

- New & Noteworthy

- Ask a Question

- See Why Stanford MSx

- Is MSx Right for You?

- MSx Stories

- Leadership Development

- How You Will Learn

- Admission Events

- Personal Information

- Reference Letters

- GMAT, GRE & EA

- English Proficiency Tests

- Career Change

- Career Advancement

- Daycare, Schools & Camps

- U.S. Citizens and Permanent Residents

- Requirements

- Requirements: Behavioral

- Requirements: Quantitative

- Requirements: Macro

- Requirements: Micro

- Annual Evaluations

- Field Examination

- Research Activities

- Research Papers

- Dissertation

- Oral Examination

- Current Students

- Education & CV

- International Applicants

- Statement of Purpose

- Reapplicants

- Application Fee Waiver

- Deadline & Decisions

- Job Market Candidates

- Academic Placements

- Stay in Touch

- Faculty Mentors

- Current Fellows

- Standard Track

- Fellowship & Benefits

- Group Enrollment

- Program Formats

- Developing a Program

- Diversity & Inclusion

- Strategic Transformation

- Program Experience

- Contact Client Services

- Campus Experience

- Live Online Experience

- Silicon Valley & Bay Area

- Digital Credentials

- Faculty Spotlights

- Participant Spotlights

- Eligibility

- International Participants

- Stanford Ignite

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Founding Donors

- Location Information

- Participant Profile

- Network Membership

- Program Impact

- Collaborators

- Entrepreneur Profiles

- Company Spotlights

- Seed Transformation Network

- Responsibilities

- Current Coaches

- How to Apply

- Meet the Consultants

- Meet the Interns

- Intern Profiles

- Collaborate

- Research Library

- News & Insights

- Program Contacts

- Databases & Datasets

- Research Guides

- Consultations

- Research Workshops

- Career Research

- Research Data Services

- Course Reserves

- Course Research Guides

- Material Loan Periods

- Fines & Other Charges

- Document Delivery

- Interlibrary Loan

- Equipment Checkout

- Print & Scan

- MBA & MSx Students

- PhD Students

- Other Stanford Students

- Faculty Assistants

- Research Assistants

- Stanford GSB Alumni

- Telling Our Story

- Staff Directory

- Site Registration

- Alumni Directory

- Alumni Email

- Privacy Settings & My Profile

- Success Stories

- The Story of Circles

- Support Women’s Circles

- Stanford Women on Boards Initiative

- Alumnae Spotlights

- Insights & Research

- Industry & Professional

- Entrepreneurial Commitment Group

- Recent Alumni

- Half-Century Club

- Fall Reunions

- Spring Reunions

- MBA 25th Reunion

- Half-Century Club Reunion

- Faculty Lectures

- Ernest C. Arbuckle Award

- Alison Elliott Exceptional Achievement Award

- ENCORE Award

- Excellence in Leadership Award

- John W. Gardner Volunteer Leadership Award

- Robert K. Jaedicke Faculty Award

- Jack McDonald Military Service Appreciation Award

- Jerry I. Porras Latino Leadership Award

- Tapestry Award

- Student & Alumni Events

- Executive Recruiters

- Interviewing

- Land the Perfect Job with LinkedIn

- Negotiating

- Elevator Pitch

- Email Best Practices

- Resumes & Cover Letters

- Self-Assessment

- Whitney Birdwell Ball

- Margaret Brooks

- Bryn Panee Burkhart

- Margaret Chan

- Ricki Frankel

- Peter Gandolfo

- Cindy W. Greig

- Natalie Guillen

- Carly Janson

- Sloan Klein

- Sherri Appel Lassila

- Stuart Meyer

- Tanisha Parrish

- Virginia Roberson

- Philippe Taieb

- Michael Takagawa

- Terra Winston

- Johanna Wise

- Debbie Wolter

- Rebecca Zucker

- Complimentary Coaching

- Changing Careers

- Work-Life Integration

- Career Breaks

- Flexible Work

- Encore Careers

- Join a Board

- D&B Hoovers

- Data Axle (ReferenceUSA)

- EBSCO Business Source

- Global Newsstream

- Market Share Reporter

- ProQuest One Business

- Student Clubs

- Entrepreneurial Students

- Stanford GSB Trust

- Alumni Community

- How to Volunteer

- Springboard Sessions

- Consulting Projects

- 2020 – 2029

- 2010 – 2019

- 2000 – 2009

- 1990 – 1999

- 1980 – 1989

- 1970 – 1979

- 1960 – 1969

- 1950 – 1959

- 1940 – 1949

- Service Areas

- ACT History

- ACT Awards Celebration

- ACT Governance Structure

- Building Leadership for ACT

- Individual Leadership Positions

- Leadership Role Overview

- Purpose of the ACT Management Board

- Contact ACT

- Business & Nonprofit Communities

- Reunion Volunteers

- Ways to Give

- Fiscal Year Report

- Business School Fund Leadership Council

- Planned Giving Options

- Planned Giving Benefits

- Planned Gifts and Reunions

- Legacy Partners

- Giving News & Stories

- Giving Deadlines

- Development Staff

- Submit Class Notes

- Class Secretaries

- Board of Directors

- Health Care

- Sustainability

- Class Takeaways

- All Else Equal: Making Better Decisions

- If/Then: Business, Leadership, Society

- Grit & Growth

- Think Fast, Talk Smart

- Spring 2022

- Spring 2021

- Autumn 2020

- Summer 2020

- Winter 2020

- In the Media

- For Journalists

- DCI Fellows

- Other Auditors

- Academic Calendar & Deadlines

- Course Materials

- Entrepreneurial Resources

- Campus Drive Grove

- Campus Drive Lawn

- CEMEX Auditorium

- King Community Court

- Seawell Family Boardroom

- Stanford GSB Bowl

- Stanford Investors Common

- Town Square

- Vidalakis Courtyard

- Vidalakis Dining Hall

- Catering Services

- Policies & Guidelines

- Reservations

- Contact Faculty Recruiting

- Lecturer Positions

- Postdoctoral Positions

- Accommodations

- CMC-Managed Interviews

- Recruiter-Managed Interviews

- Virtual Interviews

- Campus & Virtual

- Search for Candidates

- Think Globally

- Recruiting Calendar

- Recruiting Policies

- Full-Time Employment

- Summer Employment

- Entrepreneurial Summer Program

- Global Management Immersion Experience

- Social-Purpose Summer Internships

- Process Overview

- Project Types

- Client Eligibility Criteria

- Client Screening

- ACT Leadership

- Social Innovation & Nonprofit Management Resources

- Develop Your Organization’s Talent

- Centers & Initiatives

- Student Fellowships

- Sign into My Research

- Create My Research Account

- Company Website

- Our Products

- About Dissertations

- Español (España)

- Support Center

Find your institution

Examples: State University, [email protected]

Other access options

- More options

Select language

- Bahasa Indonesia

- Português (Brasil)

- Português (Portugal)

Welcome to My Research!

You may have access to the free features available through My Research. You can save searches, save documents, create alerts and more. Please log in through your library or institution to check if you have access.

Translate this article into 20 different languages!

If you log in through your library or institution you might have access to this article in multiple languages.

Get access to 20+ different citations styles

Styles include MLA, APA, Chicago and many more. This feature may be available for free if you log in through your library or institution.

Looking for a PDF of this document?

You may have access to it for free by logging in through your library or institution.

Want to save this document?

You may have access to different export options including Google Drive and Microsoft OneDrive and citation management tools like RefWorks and EasyBib. Try logging in through your library or institution to get access to these tools.

- More like this

- Preview Available

- Scholarly Journal

McDonald's: A Case Study in Glocalization

No items selected.

Please select one or more items.

You might have access to the full article...

Try and log in through your institution to see if they have access to the full text.

Content area

The purpose of this research report was to assess McDonald's globalization strategy. We examined McDonald's strategy across six dimensions: menu, promotion, trademarks, restaurants, employees, and service. We also compared the company's performance across these six dimensions in 10 different countries: Saudi Arabia, France, the United Kingdom, Greece, Brazil, Indonesia, India, China, Japan, and New Zealand to measure McDonald's success in capitalizing on globalization and localization. As discussed in this report, McDonald's is a global brand through its worldwide standards and training operations, but the company is also local, with its franchising to local entrepreneurs, locally sourcing food, and targeting specific local consumer market demands. McDonald's is an excellent example of blending global with local - an organization that has glocalized very successfully.

Introduction and Purpose

McDonald's has been serving fast food to America since 1955 and has grown into one of the world's leading fast food giants. Today, McDonald's is the leading global foodservice retailer with 1.7 million employees and more than 34,000 restaurants in 119 countries serving nearly 69 million people each day (McDonald's, Annual Report, 2012).

Not too long ago people believed McDonald's would become "a lumbering cash cow in a mature market" (Serwer & Wyatt, 1994). However, its success abroad has offset the maturing market in America. In fact, 65% of McDonald's sales came from international revenues (McDonald's, Annual Report, 2012.) Its worldwide operation concentrates its global strategy, "Plan to Win," and on customer experience, which includes people, products, place, price, and promotion.

This paper will compare McDonald's marketing strategy to determine how well it capitalizes on both globalization and localization. It will look at this strategy by examining ten different countries: Saudi Arabia, France, the United Kingdom, Greece, Brazil, Indonesia, India, China, Japan, and New Zealand, across six different dimensions: menu, promotion, trademarks, restaurants, employees, and service.

McDonald's: The American Standard

The McDonald's American model focuses on fast and convenient service with high purchasing turnover. Its recognizable bright red and yellow colors with the iconic golden arches reaching into the sky offer Americans a piece of the familiar in a foreign country. "Our goal is to become customers' favorite place and way to eat and drink by serving core favorites such as our World Famous Fries, Big Mac,...

You have requested "on-the-fly" machine translation of selected content from our databases. This functionality is provided solely for your convenience and is in no way intended to replace human translation. Show full disclaimer

Neither ProQuest nor its licensors make any representations or warranties with respect to the translations. The translations are automatically generated "AS IS" and "AS AVAILABLE" and are not retained in our systems. PROQUEST AND ITS LICENSORS SPECIFICALLY DISCLAIM ANY AND ALL EXPRESS OR IMPLIED WARRANTIES, INCLUDING WITHOUT LIMITATION, ANY WARRANTIES FOR AVAILABILITY, ACCURACY, TIMELINESS, COMPLETENESS, NON-INFRINGMENT, MERCHANTABILITY OR FITNESS FOR A PARTICULAR PURPOSE. Your use of the translations is subject to all use restrictions contained in your Electronic Products License Agreement and by using the translation functionality you agree to forgo any and all claims against ProQuest or its licensors for your use of the translation functionality and any output derived there from. Hide full disclaimer

Suggested sources

- About ProQuest

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Policy

- SUGGESTED TOPICS

- The Magazine

- Newsletters

- Managing Yourself

- Managing Teams

- Work-life Balance

- The Big Idea

- Data & Visuals

- Reading Lists

- Case Selections

- HBR Learning

- Topic Feeds

- Account Settings

- Email Preferences

Globalization

- Behavioral economics

- Economic cycles and trends

- Economic systems

- Emerging markets

The State of Globalization in 2021

- Steven A. Altman

- Caroline R. Bastian

- March 18, 2021

Emerging Expertise

- Steven Sams

- From the May 2005 Issue

Case Study: From Niche to Mainstream

- April 25, 2018

Geopolitics Are Changing. Venture Capital Must, Too.

- Hemant Taneja

- Fareed Zakaria

- February 10, 2023

The State of Globalization in 2023

- Caroline R Bastian

- July 11, 2023

Name Your Brand with a Global Audience in Mind

- Nataly Kelly

- September 10, 2020

Right Up the Middle: How Israeli Firms Go Global

- Jonathan Friedrich

- From the May 2014 Issue

What 45 Years of Data Tells Us About Globalization's Influence on the Shadow Economy

- Robert G Blanton

- Dursun Peksen

- Bryan Early

- May 08, 2018

Connect and Develop: Inside Procter & Gamble’s New Model for Innovation

- Larry Huston

- Nabil Sakkab

- From the March 2006 Issue

An Agenda for the Future of Global Business

- Johann Harnoss

- Martin Reeves

- February 27, 2017

The New Tools of Trade

- Regina M. Abrami

- Leonard Bierman

Are the Risks of Global Supply Chains Starting to Outweigh the Rewards?

- Willy C Shih

- March 21, 2022

How Amazon Adapted Its Business Model to India

- Vijay Govindarajan

- Anita Warren

- July 20, 2016

Making M&A Fly in China

Why Europe Tops 2015's List of Global Risks

- January 09, 2015

Not As Global As We Think

- From the March 2015 Issue

The New Economy’s Troubling Trade Gap

- Eamonn Fingleton

- From the November–December 1999 Issue

China Myths, China Facts

- Elisabeth Yi Shen

- From the January–February 2010 Issue

Capturing the Ricochet Economy

- Vijay Mahajan

- Yoram (Jerry) Wind

- From the November 2006 Issue

The Element of Surprise Is a Bad Strategy for a Trade War

- Chad P. Bown

- April 16, 2018

When Expanding into a Foreign Market, Your Outsider Status Is a Competitive Advantage

- May 31, 2024

5 Myths Expats Believe About Local Employees

- Snejina Michailova

- Anthony Fee

- May 28, 2024

Building Cross-Cultural Relationships in a Global Workplace

- Andy Molinsky

- Melissa Hahn

- February 29, 2024

Is China’s Economic Dominance at an Inflection Point?

- Allen J. Morrison

- J. Stewart Black

- February 13, 2024

The Radical Reshaping of Global Trade

- Rita McGrath

- November 01, 2023

AI and the New Digital Cold War

- September 06, 2023

Digital Skills Provide a Development Path for Sub-Saharan Africa

- Ndubuisi Ekekwe

- July 25, 2023

Does Your Company Have an India Strategy?

- Rajendra Srivastava

- Anup Srivastava

- Aman Rajeev Kulkarni

- June 27, 2023

The U.S.–India Relationship Is Key to the Future of Tech

- April 17, 2023

Eurasia Group’s Ian Bremmer: Biggest Threat to World Is Rogue Actors – From Putin to Musk

- January 19, 2023

How Companies Can Navigate Today’s Geopolitical Risks

- David S. Lee

- Brad Glosserman

- November 28, 2022

Has Trade with China Really Cost the U.S. Jobs?

- Scott Kennedy

- Ilaria Mazzocco

- November 10, 2022

Creating a Successful Plan to Electrify Transportation Infrastructure

- November 08, 2022

What the Next Era of Globalization Will Look Like

- Walter Frick

- November 03, 2022

Trade Regionalization: More Hype Than Reality?

- May 31, 2022

3 Obstacles to Globalizing a Digital Platform

- Noman Shaheer

- Max Stallkamp

- May 03, 2022

The State of Globalization in 2022

- April 12, 2022

- Willy C. Shih

Novartis: Leading a Global Enterprise

- William W. George

- Krishna G. Palepu

- Carin-Isabel Knoop

- May 27, 2013

HNA Group: Moving China's Air Transport Industry in a New Direction

- William C. Kirby

- F. Warren McFarlan

- Tracy Yuen Manty

- November 19, 2008

Wanxiang Group: A Chinese Company's Global Strategy

- Regina Abrami

- Keith Chi-ho Wong

- February 26, 2008

Wal-Mart in 2002

- David B. Yoffie

- March 22, 2002

Dabur India Ltd. - Globalization

- Niraj Dawar

- Chandra Sekhar Ramasastry

- June 10, 2009

Trade Restrictions and Hong Kong's Textiles and Clothing Industry

- Richard Wong

- January 31, 2005

Timberland: Commerce and Justice

- James E. Austin

- Herman B. Leonard

- James W. Quinn

- July 19, 2004

Coca-Cola's New Vending Machine (A): Pricing to Capture Value, or Not?

- Charles King

- Das Narayandas

- February 07, 2000

Capitalism, Slavery, and Reparations

- Sophus A. Reinert

- Cary Williams

- April 15, 2021

National Innovation Systems of China and the Asian Newly Industrialised Economies: A Comparative Analysis

- Ali Farhoomand

- Samuel Tsang

- March 29, 2005

Baidu and Google in China's Internet Search Market: Pathways to Globalisation and Localisation

- Chen Wei-Ru

- Kuangzhen Wu

- March 27, 2009

Qualcomm and Intel: Evolving Strategies in the Mobile Chipset Industry in 2014

- John Thomas

- Robert A. Burgelman

- October 28, 2015

Arcor: Global Strategy and Local Turbulence (Abridged)

- Pankaj Ghemawat

- Michael G. Rukstad

- Jennifer L. Illes

- July 01, 2009

Future of "Big Pharma?"

- David W. Conklin

- Murray J. Bryant

- Danielle Cadieux

- August 12, 2005

IBM: Building with Blockchain

- B. Tom Hunsaker

- January 01, 2018

Zespri Grows

- David E. Bell

- Natalie Kindred

- November 26, 2018

The TAG Heuer Carrera Connected Watch (A): Swiss Avant-Garde for the Digital Age

- Felipe L Monteiro

- April 21, 2017

Wealth Management Crisis at UBS (A)

- Paul M. Healy

- George Serafeim

- March 04, 2011

Wanxiang Group: A Chinese Company's Global Strategy (B)

- Nancy Hua Dai

- Erica M Zendell

- January 23, 2013

India: The Dabhol Power Corporation (A)

- Shashi Verma

- April 27, 2001

Popular Topics

Partner center.

- Register or Log In

- 0) { document.location='/search/'+document.getElementById('quicksearch').value.trim().toLowerCase(); }">

Issues of Globalization: Case Studies in Contemporary Anthropology

- Anthropology

Burning at Europe's Borders

Alexander-Nathani

Burning at Europe’s Borders invites readers inside the lives of the world’s largest population of migrants and refugees — the hundreds of thousands who are trapped in hidden forest camps and forgotten detention centers at Europe’s southernmost borders in North Africa. “ Hrig ,” the Arabic term for “illegal immigration,” translates to “burning.” It signifies a migrant’s decision to bu...

Burning at Europe’s Borders invites readers inside the lives of the world’s largest population of migrants and refugees — the hundre...

Care for Sale

Gutiérrez Garza

In homes and brothels around the world, migrant women are selling a unique commodity: care. Care for Sale is an in-depth ethnography of a group middle-class women from Latin America who exchange care and intimacy for money while working as domestic and sex workers in London. Illuminating the complexities of care work, the proposed book is a detailed study of women’s lives and working conditions. It considers how their experience of migratio...

In homes and brothels around the world, migrant women are selling a unique commodity: care. Care for Sale is an in-depth ethnography of a group middle...

Indebted examines the economic and political factors that led to the Greek debt crisis, investigating the effects of financial pressures from international lenders, unregulated spending by the Greek government, predatory bank loans, and rising unemployment. The book looks closely at the cultural dimensions of the crisis—how middle class urbanites experienced the shock of a global collapse, managed societal instability, and worked to sustain their...

Indebted examines the economic and political factors that led to the Greek debt crisis, investigating the effects of financial pressures from internat...

Labor and Legality Tenth Anniversary Edition

Gomberg-Muñoz

Labor and Legality is an ethnographic account of the lives of ten undocumented workers in Chicago, originally published in 2010. The book seeks to push past one-dimensional rhetoric and show that undocumented workers are neither mere victims nor criminals, but complicated people engaged in workaday struggles to make their lives better. The book follows these men through their daily routines and records their efforts to improve their fortunes and ...

Labor and Legality is an ethnographic account of the lives of ten undocumented workers in Chicago, originally published in 2010. The book seeks to pus...

Low Wage in High Tech

Mirchandani, Mukherjee, Tambe

Low Wage in High Tech focuses on the lives and livelihoods of housekeepers, drivers, and security guards who work in India's multinational technology firms. These call centers and software firms are housed in gleaming corporate towers within lavish special economic zones; spaces which have become symbolic of new, sanitized, technology-driven development regimes. However little is known about the workers who are responsible for the daily maintenan...

Low Wage in High Tech focuses on the lives and livelihoods of housekeepers, drivers, and security guards who work in India's multinational technology ...

Marriage After Migration

Marriage After Migration is a compelling ethnography centered around the stories of five women in rural Mexico as they work to keep their communities and families together when their spouses migrate abroad. Through rich and highly readable narratives about the lives of these women, author Nora Haenn explores how international migration affects kinship ties and rewrites gender roles. Haenn's research illuminates aspects of migration and globalizat...

Marriage After Migration is a compelling ethnography centered around the stories of five women in rural Mexico as they work to keep their communities ...

Serious Youth in Sierra Leone: An Ethnography of Performance and Global Connection

Generational anxieties over what will happen to the young are unfolding starkly in Sierra Leone, where the civil war that raged between 1991 and 2002-characterized by the extreme youthfulness of the rebel movement-triggered mass fear of that generation being "lost." Even now, fifteen years later with these children grown into young adults, "children of the war" are regarded with suspicion. These fears stem largely from young people's easy embrace...

Generational anxieties over what will happen to the young are unfolding starkly in Sierra Leone, where the civil war that raged between 1991 and 2002-...

Waste and Wealth

Waste and Wealth examines questions of value, labor, and morality underlining the translocal waste networks in Spring District, Vietnam. Engaging with waste as an economic category of global significance, this book provides an account of migrant laborers' complex negotiations with political economic forces to build their economic, social, and moral life from their marginalized position. It thereby makes visible how women and men seek to construct...

Waste and Wealth examines questions of value, labor, and morality underlining the translocal waste networks in Spring District, Vietnam. Engaging with...

Select your Country

Globalization: Case Studies

Learning objectives.

- Students will analyze how technological advancements have led to increased globalization.

- Students will create presentations that inform about ways in which globalization impacts daily life.

- Students will complete Parts 1 and 2 of the guided reading handout.

- (5 Minutes) Debrief Homework: Ask students to share key takeaways from homework. Highlight that 1) technological advances have increased globalization and 2) globalization has a direct impact on their daily lives in the food they eat. This sets the stage for a deeper look at the impact of globalization through case studies.

- Group 1: A Global Semiconductor Shortage

- Group 2: Big in China: The Global Market for Hollywood Movies

- Group 3: Human Trafficking in the Global Era

- A Global Semiconductor Shortage = data related to backorders, map of supply chain, chips used in a car visual, bullet points of what CHIPS Act does

- Big in China = data on box office sales, images related to censored movies, etc.

- Human Trafficking = data about numbers of people affected, visuals of common industries where trafficking is common, visuals about products tied to human trafficking.

Students should complete the Impact of Globalization Infographic/ Presentation. They will share at the beginning of the next class meeting. If possible, their infographics should be displayed or shared with the larger school audience (i.e: submitted to the school newspaper).

withholding of information, typically by a government or an authoritative body.

cable, made out of strands of glass as thin as hair, used to quickly transmit large volumes of internet traffic between locations all over the globe.

disease outbreak that has reached at least several countries, affecting a large group of people.

supreme or absolute authority over a territory.

a network—consisting of individual producers, companies, transportation, information, and more—that extracts a raw material, transforms it into a finished product, and delivers it to a consumer.

an international institution created in 1995 that regulates trade between nations. A replacement for the 1947 General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), the WTO manages the rules of international trade and attempts to ensure fair and equitable treatment for its 164 members. It does this by conducting negotiations, lowering trade barriers, and settling disputes. As of 2018, the WTO had 164 members.

In order to continue enjoying our site, we ask that you confirm your identity as a human. Thank you very much for your cooperation.

Browse Econ Literature

- Working papers

- Software components

- Book chapters

- JEL classification

More features

- Subscribe to new research

RePEc Biblio

Author registration.

- Economics Virtual Seminar Calendar NEW!

Economic globalization in the 21st century: A case study of India

- Author & abstract

- 6 References

- Most related

- Related works & more

Corrections

(Assistant Professor, Christ (Deemed to be) University, NCR, India)

Suggested Citation

Download full text from publisher, references listed on ideas.

Follow serials, authors, keywords & more

Public profiles for Economics researchers

Various research rankings in Economics

RePEc Genealogy

Who was a student of whom, using RePEc

Curated articles & papers on economics topics

Upload your paper to be listed on RePEc and IDEAS

New papers by email

Subscribe to new additions to RePEc

EconAcademics

Blog aggregator for economics research

Cases of plagiarism in Economics

About RePEc

Initiative for open bibliographies in Economics

News about RePEc

Questions about IDEAS and RePEc

RePEc volunteers

Participating archives

Publishers indexing in RePEc

Privacy statement

Found an error or omission?

Opportunities to help RePEc

Get papers listed

Have your research listed on RePEc

Open a RePEc archive

Have your institution's/publisher's output listed on RePEc

Get RePEc data

Use data assembled by RePEc

‘Containerization in Globalization’: A Case Study of How Maersk Line Became a Transnational Company

- Open Access

- First Online: 30 October 2019

Cite this chapter

You have full access to this open access chapter

- Henrik Sornn-Friese 7

Part of the book series: Palgrave Studies in Maritime Economics ((PSME))

16k Accesses

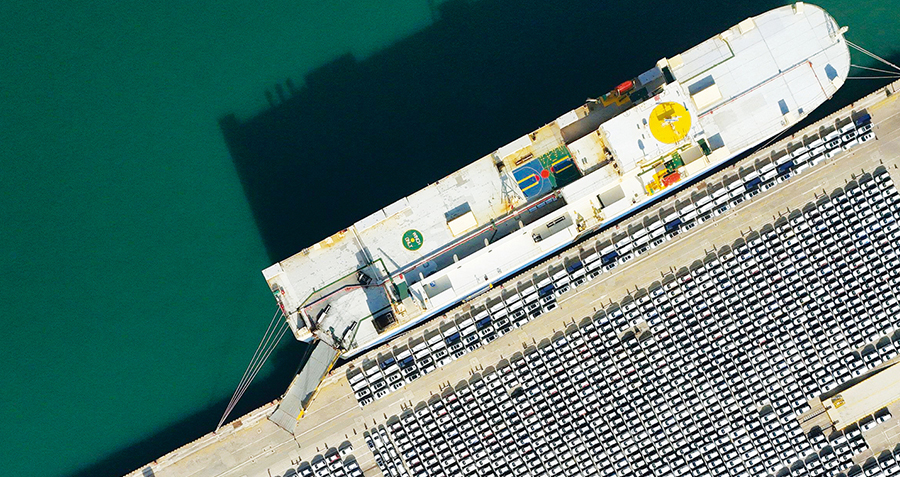

2 Citations

This chapter is a historical case study of Maersk Line, the world’s leading container carrier. Maersk Line’s global leadership was achieved within a relatively short time period and was the result of Mærsk Mc-Kinney Møllers decision in 1973 to enter container shipping—the biggest investment in the history of the AP Moller companies. When Maersk Line managed to achieve global leadership in a period of just about 25 years, the company’s own country offices were particularly important. They allowed the interconnection of three types of networks: The physical network of ships and routes, the digital network of information and communication systems and the human network of Maersk employees. The interaction between the vessels, the systems and the people is still at the core of the company today and central to its continued development.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

The Strategic Consequences of Containerization

Container Ports in Latin America: Challenges in a Changing Global Economy

Peripherality in the global container shipping network: the case of the southern african container port system, introduction.

This chapter is generally based on and extends an earlier article, written in Danish, Sornn-Friese ( 2017 ).

Studies on the role of containerization in globalization have centred either broadly on the history of the liner shipping industry, Footnote 1 or more narrowly on strategic alliances Footnote 2 and global maritime networks. Footnote 3 Most of these studies in addition have been carried out at the industry level and have largely neglected the strategic dynamics associated with identifying business opportunities at home and abroad, the mobilization of resources, and efforts to continually adjust company strategy and organization. This chapter adds to the literature in two ways. Firstly, by shifting the unit of analysis from that of industry to that of the firm and, secondly, by focusing on the process of a company’s transnationalization, which entails the establishment of a global network of subsidiaries orchestrated by a central corporate headquarters. Footnote 4

The chapter uses a historical case study of Maersk Line, the world’s leading container carrier. Maersk Line’s global leadership was achieved within a relatively short time period and was the result of Mærsk Mc-Kinney Møllers decision in 1973 to enter container shipping—the biggest investment in the history of the AP Moller companies. Maersk Line has since grown into the world’s largest container ship operator with almost 33,000 employees in 130 countries, a fleet of 639 container ships serving 59,000 customers around the globe, more than 300 own company offices in 121 countries, global service centres in Denmark, the Philippines, India and China, and access to 343 port terminals and inland transport facilities in 61 countries, partly through its sister company APM terminals.

Why did Maersk Line decide to become a global company, and how did it manage so quickly to achieve leadership in an industry dominated by a small number of consortia organized in cartel-like liner conferences? The major features in the company’s development are well documented, but the story of how Maersk Line became a transnational corporation is an overlooked chapter. Footnote 5 The replacement of long-established third-party agency agreements with own offices after 1974 was a decision of great importance that enabled superior services globally. The motto ‘service all the way’ was the hallmark and a major driving force for the company. In a rare interview, the person in charge of the new container initiative, Mr Ib Kruse, explained how the company’s competitiveness rested on a service ‘second to none’, realized through the combination of modern and effective company-owned ships with sophisticated equipment developed in-house, a global network of own company offices and high-level communication, and sophisticated documentation and control systems. Footnote 6 This chapter examines the development of these elements.

Through interviews with current and former employees of the AP Moller-Maersk Group, documents from the company’s private archives and various secondary sources, the transnationalization of Maersk Line is studied as an ‘extended era’, limited in time and focusing on the substitution of third-party agents abroad with own country offices. With inspiration from the theory of dynamic capabilities the chapter seeks to explain how Maersk Line created an efficient global organization while adapting its services to local market needs in the countries where it operates. Footnote 7 The chapter demonstrates strategic change by examining the company’s ability to capture and understand new business opportunities, seize them and change the company’s core competencies. The study of such dynamic capabilities provides new perspectives for the understanding of transnational corporations. Footnote 8

The analysis focuses largely on the period from 1974 to 1999, during which the establishment of the company’s global network of own overseas offices was particularly pronounced. In this period, the company’s many country managers had, as ‘entrepreneurs and kings’, the responsibility to create profits in their own country, and there were many local investments in container shipping and related services. Footnote 9 The Copenhagen headquarters decided on the overall strategy for Maersk Line and had a direct role in local development, but country offices were run as profit centres. Towards the end of the period, culminating in the acquisition of Safmarine and Sea-Land in 1999, the organization changed gradually, with the multifarious activities increasingly organized into independent product lines.

A Transnational Company

Unlike the global companies of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, primarily plantation, mining and international trade, which were typically state-supported monopolies on specific trades within the European colonies, modern transnational companies such as Maersk Line are characterized by their involvement in direct business activities abroad and their ability to profit from cooperation and international division of labour. Footnote 10

The decision in 1973 to enter into container shipping was the start of Maersk Line’s deep internationalization, developing as a genuine transnational corporation. Not only is Maersk Line today a huge and diverse company that serves customers around the globe with different needs and expectations, its activities are also managed so as to provide economies of scale through a global organization while the company can concurrently handle various conditions in different regions of the world and differentiate its services to local needs.

Several factors differentiate the transnational company from other international companies. Footnote 11 Transnational companies are able to plan, organize, coordinate and control their business activities across countries—typically from a central headquarters and through the setting of common goals and strategies. Characteristically, they promote multiple internal management perspectives, through which they can decode and respond to the diversity of external demands and opportunities; their interdependent physical assets and management capabilities are distributed internationally; and they have a strong unifying management approach. Footnote 12 The latter is characterized by top management’s ability to synchronously manage context, processes and content. Context management is the task of providing a structure for delegated decision-making based on clear goals and priorities, career development for leaders with a global mindset, and established decision-making procedures. Top management’s direct intervention in organizational processes may include minor modifications, typically handled through continuous monitoring and additional decision support, as well as major interventions (such as establishing temporary working groups and task forces) in larger or more complex situations. Through content management, top management intervenes directly in local decision-making situations, if an issue remains unresolved, or if a previously selected solution proves unsatisfactory.

Soon after World War II Maersk Line had established a handful of offices abroad, and these became important for the subsequent container endeavour and for the building of the company’s transnational organization from the middle of the 1970s. The latter followed the expansion of the trade network, where new regions were gradually added. In each region, Maersk Line established key country offices, while in individual ports and certain mainland hubs it opened up small branch offices. In the few locations that did not offer enough business volume to form a true profit centre, the company continued to be represented by third party agents.

Only Taiwan’s Evergreen matched Maersk Line’s approach in scope and dedication, and the two became the first real transnational companies in international container shipping. Although there was strategic awareness of the importance of strong representation locally, Maersk Line’s global organization was not the result of a conscious transnational strategy, but rather of a long process of change in which the company reacted to business opportunities as they arose and dismissed the elements it found not to work. It is true, however, that container shipping, at least initially, required proximity to the customers, that certain economies of scale to some extent justified strong local country offices, and that the strength of the company’s distinct entrepreneurial culture, where it ‘was better to get forgiveness than to get permission’, made it desirable to have a functioning internal sharing of knowledge and information. Footnote 13 All this contributed to the transnationalization of Maersk Line through a period when container shipping—driven by the transition from general cargo traffic to standard containers and the relocation of production from the West to low-wage countries in Southeast Asia—was a high-growth market.

The Establishment of the First Maersk Line Offices Abroad

Shortly after World War I Arnold Peter Møller started tramp shipping services in the US freight market, from where he soon also served the Far East. In 1919 he and his cousin, Hans Isbrandtsen, who had immigrated to the United States in 1915, together founded the Isbrandtsen-Moller Company (ISMOLCO) in New York. The international activities of the AP Moller-companies thus early on included ownership and strategic management control across borders. In 1928 ISMOLCO went into the liner business of shipping cargo from the US East Coast via the Panama Canal to the Far East, and hence Maersk Line was born. The Panama line was successful, and in 1931 Maersk Line had three ships in regular services on the route.

Like most liner companies Maersk Line employed local agents in the ports where the company’s ships were calling. ISMOLCO was an agent for Maersk Line in the United States, and a few years after the establishment of the Panama line Mr Møller had built a network of third-party agents in Asia. The network comprised of the shipping departments of large industrial companies, such as Mitsubishi of Japan and Compañía General de Tabacos de Filipinas (‘Tabacalera’) in the Philippines, Footnote 14 and international trading houses specialized in liner shipping, such as, Melchers & Co in Shanghai (1931–1946), Jebsen & Co in Hong Kong (1946–1975) and in Shanghai (1946–1969), and Tait & Co in Taiwan. Footnote 15 The latter were typically larger companies each with their portfolio of agencies and with their own teams dedicated to each customer. During 1973–1976 Chris Jephson was employed by Tait & Co in Taiwan and responsible for their Maersk Line team, a group of 15–16 people focused exclusively on servicing Maersk Line. Tait & Co was agent for more than 70 shipping companies from around the world, several of which were Maersk Line’s direct competitors. Footnote 16

WWII put a temporary halt to Maersk Lines’ activities, but from 1946 the Panama line was reopened. In the post-war years, Maersk Line established country offices in Thailand, Indonesia, the United States and Japan. The four offices proved important for the development of Maersk Line’s global organization after 1974. Moreover, in 1951 Maersk Company Limited was established in London as an independent company that could operate the AP Moller fleet under the British flag in the event of a new war in Europe. Similarly, during the Cold War, Maersk Inc. in New York (see below) developed as a separate shadow headquarters that could take over the Maersk Line fleet in the event of a new war in Europe.

The first country office had been established in New York, where Mærsk Mc-Kinney Møller stayed during WWII. Along with Thorkil Høst, the former head of the AP Moller liner department in Copenhagen, he founded the Interseas Shipping Company. The new company, which in 1943 changed its name to Moller Steamship Company, was set to replace ISMOLCO as agent for Maersk Line in the United States, as A. P. Møller had decided to break with his cousin. When Mærsk Mc-Kinney Møller in 1947 moved back to Denmark, the Moller Steamship Company was fully staffed and operational and busy rebuilding the Panama line. Under Høst’s leadership from 1947 to 1967, the Moller Steamship Company grew into a large and successful company with autonomous top management and Board of Directors. In 1955 the company established its own office in Los Angeles and in 1973 extended with an office in San Francisco. After the containerization of Maersk Line the company quickly built an extensive network of own offices in the United States and Canada.

From early spring 1946 the ships were once again fully loaded travelling from the United States to the Far East, and many of the customers from before the war returned to Maersk Line. Footnote 17 It was, however, difficult to generate backhaul from the Far East to the United States, and Maersk Line was working keenly to adapt its agent network in Asia to generate home-going cargoes. Cooperation with the agents in Hong Kong, Manila and Taiwan were strengthened, but to access the lucrative Japan traffic, which in the post-war years was reserved for American tonnage, the company had to make a detour. Footnote 18 In 1947, Mærsk Mc-Kinney Møller therefore established Maersk Line Ltd (MLL) in Delaware, which gave access to the Asian countries managed by the Americans under General Douglas MacArthur, the Supreme Commander of the Allied Powers. In 1948, MLL opened up its own country office in Yokohama south of Tokyo and branch offices in Kobe and Osaka, and in 1958 it expanded with a branch office in Jakarta, replacing the existing agency agreement with Harrisons & Crosfield in Indonesia. MLL was mainly an administrative unit and it played no direct commercial role for Maersk Line until 1983 when it got a contract with the US Defense Department.

The branches in Japan and Indonesia developed in a short time to become important country offices for Maersk Line in the Far East, and Japan became a bridgehead to Thailand. In September 1949, the first Maersk Line ship called on Bangkok with the supply of railway equipment from Japan to the Thai State Railways. The new Japan-Thailand route, which in the following year was extended to the Persian Gulf, provided safe and regular cargo, and already in 1951 Maersk Line established an office in Bangkok, which soon was as important as the country offices in Japan and Indonesia.

Maersk Line expanded dramatically during the post-war period with the establishment of new routes. In addition to Japan-Thailand and Japan-Persian Gulf, it established a transatlantic line in 1947 (which was closed down again in 1954), a Suez line in 1949, a Japan-Indonesia line in 1952, a Gulf of Mexico-West Africa line in 1958 and a Japan-West Africa line in 1959.

Table 5.1 shows Maersk Line’s coverage through third-party agents and own offices in 1958. With continuous network expansion, the company’s agent network grew significantly in the post-war years, and there was an increased need for coordination and information exchange. From 1956 there would be regular meetings between the Principal Agents and the liner department in Copenhagen. The first Principal Agents’ Meeting was held North of Copenhagen and lasted two days, and the meetings were then repeated at 2–3 year intervals. Footnote 19 When Maersk Line almost two decades later went into container shipping, the agent meetings had become weeklong events with executives from Copenhagen and the principal agents from around the world. Although they were indeed autonomous and legally independent companies, the principal agents were considered an integral part of Maersk Line, as made apparent by A. P. Møller in his welcoming speech during the second Principal Agents’ Meeting in 1958: ‘You are now all in the Maersk family, and we are happy to have you as members thereof. You have all done a good job to serve as a member of that family, and I hope that you will all continue to make the Maersk name honoured, respected, and still growing. I thank you, Gentlemen!’. Footnote 20

Developments 1974–1999

Maersk Line’s international organization proved to be an important prerequisite for the company’s success in container shipping. The country managers in the United States, Japan, Thailand and Indonesia (so-called ‘Maersk Top’) were part of the ‘crash committee’ established by Mærsk Mc-Kinney Møller in early 1970 with the task to investigate whether the Panama line should be containerized. Footnote 21 Prior to this there had been a cautious attempt to initiate a containerized service between Asia and Europe in cooperation with Japanese ‘K’ Line, but the Japanese had terminated the partnership and Maersk Line’s first container ship had instead been chartered out. The four-country managers were deeply involved in the decision to containerize the line and their country offices were important building blocks in the unfolding of this new venture globally. Footnote 22 Local presence along the Panama line was crucial for success as the ultimate goal was a worldwide door-to-door service in which the company would control the customer’s transport task from supplier to final destination. Footnote 23 The country managers contributed international knowledge and experience as well as an organizational platform for the containerization of the line.

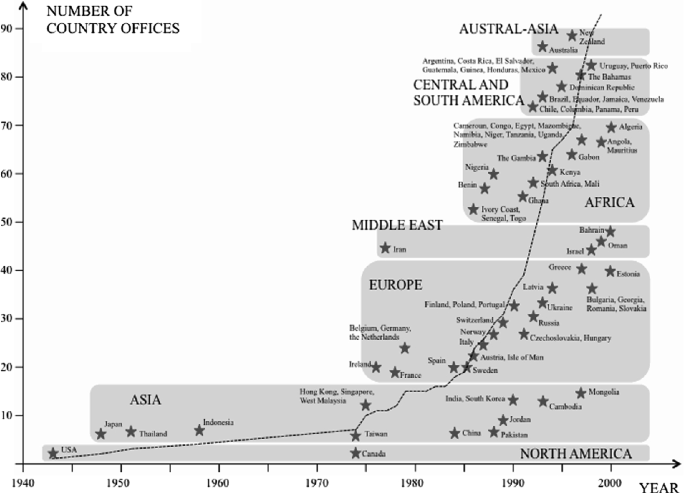

‘Maersk Container Line’ was initially shielded from AP Moller’s conventional liner business and was a small unit in Copenhagen with only five employees: Ib Kruse (managing director), Flemming Jacobs (marketing and sales), Niels Jørgen Iversen (ship operations), Birger Riisager (finance and IT) and Erik Holtegaard (conference matters). Globally the unit had only about 30 employees. The recommendations from the crash committee to the organization were: ‘Develop the essential management organization, taking account of both the new skills that will be necessary and the quality of staff required in each location’. Footnote 24 In 1974 it was decided to establish country offices in Hong Kong and Singapore, and from that time onwards there was rapid establishment of offices in Asia, Europe and North America and later in the rest of the world, as illustrated in Fig. 5.1 .

( Source AP Moller-Maersk, Main Archive, various boxes)

The establishment of Maersk Line country offices

The establishment of country offices were each international episodes of great importance and can be described as revolutionary steps towards the transnationalization of Maersk Line, whereas the creation of smaller, local offices were gradual extensions in an ongoing, evolutionary internationalization process. Footnote 25 Each country office was established as a profit centre—an independent, and in the country legally domiciled, company with its own board and management. Each establishment had thus a long-term perspective; they were ‘good citizens’ locally and not temporary structures aimed at ‘looting’. Footnote 26 Country managers were typically expat Danes sent from the Copenhagen headquarters, while the other employees in the offices were well-qualified locals recruited from the shipping and freight forwarding industry. The focus on own country offices was on building a global agency network, with emphasis on the word ‘network’: although the offices were established as profit centres, there was a strong central management from Copenhagen in the form of advanced IT systems and behavioural incentives, and effective socialization mechanisms worked to interconnect the organization across countries and companies.

Employees were carefully selected and tested. Already in the 1960s McKinney-Møller had introduced a so-called Predictive Index (PI) system for staff assessment, where employees were measured on intellect and personality. From this system was drawn a global inventory of talents that could be called upon whenever the organization lacked ‘the right person at the right time and place’.

Employees were stationed in a country for a number of years and then either sent on to another country for an additional time period or back to the head office in Copenhagen. In that way, employees developed actual country experience and international perspective, and they forged strong ties to other Maersk people, essentially forming a ‘Maersk-blue brotherhood’.

Marketing and Sales was a primary management philosophy. A comprehensive and detailed marketing manual had been developed for use in the conventional liner business in 1974, the distribution of which was restricted to Maersk Line personnel and agencies. The manual specified the Maersk Line logo, which consisted of two elements: ‘a Maersk blue square with rounded corners containing a white seven-pointed star (“standing on two points”), and the name Maersk Line’. Footnote 27 It also specified in great detail how the logo should be applied in communication (e.g., transportation documents, cover letters, envelopes, name badges, and business cards), on the company’s ships and vehicles, and in other advertisement (match boxes, playing cards, pencils and pens, memo pads, calculators, alarm clocks, LEGO ship models, and more). All overseas offices would use the manual to ensure that sales and marketing was handled properly.

Similarly, there was a written manual for the design of Maersk Line offices, narrowly specifying the choice of colours, furniture and office wall art (the offices should always have pictures of A. P. Møller and Mærsk Mc-Kinney Møller as well as the Danish Royal family). The manual also promoted a strict dress code, however allowing for smaller deviations to accommodate to local customs in the different countries.

There was outspoken focus on training and education, particularly in sales. The company’s global sales training program was managed from Copenhagen, but performed and adapted locally. With the rapidly expanding global organization the company’s training efforts were vigorously developed, and from 1993 firmly established in the M.I.S.E. program (‘Maersk International Shipping Education’), which annually attracted more than 85,000 applicants worldwide to around 500 trainees positions. Footnote 28

In 1967, Poul Rasmussen replaced Thorkil Høst as country manager in the United States, and after the decision to containerize the Panama line in 1973 he replaced the company’s third-party agents in the United States with own offices in the most important ports. These typically focused on sales and customer services, but in major ports such as Baltimore and Charleston they would also carry out ship operations. In 1978, Alfred B. (‘Ted’) Ruhly took over after Rasmussen. Among many other initiatives, Ruhly introduced quality circles in the organization, based on the principle that ‘what gets measured, gets done’. Quality Control subsequently spread to Maersk Line globally as a key underpinning in being ‘second to none’.

When Moller Steamship Company in 1988 changed its name to Maersk Inc. and moved to larger premises in New Jersey, it had more than 30 own offices in the United States and Canada. The name change was a result of increased marketing of the Maersk brand, but the company’s function was unchanged. Maersk Inc. had a high degree of autonomy from Copenhagen, partly due to the business volume based on the remarkable Post-WWII expansion of the US economy and the importance of the Panama service to Maersk Line, and partly due to the role the organization got with Mc-Kinney Møller’s residence in the United States during WWII. In the 1990s, the culture to some extent was a reflection of the culture in Copenhagen but mixed with strong elements of American leadership. Footnote 29 When Maersk Line acquired Sea-Land in 1999 Maersk Inc. played a major role, both in the dialogue with the US authorities and in the work to get the two companies integrated. With the acquisition of Sea-Land, Maersk Inc. more than doubled in size and was now by far the largest shipping company in the Americas with more than 100 offices in the United States, Canada, South America, Central America, and the Caribbean. Footnote 30

Until the mid-1990s the establishment of new country offices followed in a steady stream and anchored Maersk Line in Eastern Europe as well as in Africa, China and the Middle East. In the locations where Maersk Line, due to local institutional conditions, could not be established with wholly-owned subsidiaries, the company would set up exclusive Maersk Line units in the organizations of its third-party agents. Having own employees stationed was considered as a key issue, partly with the aim to inject the right dose of ‘Maersk blue blood’ in the organization and partly to provide own people with specific country experiences and an international outlook.

In 1993, Maersk Line went into nine new countries and 24 overseas Maersk Line offices were added to the organization. Particularly interesting was the establishment in Australia and the continuation of containerization of routes within Asia. These included the acquisition of EAC’s Far East Line and certain of their offices in the area. This all happened before the intra-Asia container market became the world’s largest. Included in the acquisition of EAC’s Far East Line was an Eastern Australian service between Melbourne, Sydney, Brisbane and two ports in Japan and Korea, as well as a Western Australian service between Fremantle, Singapore, Malaysia, Hong Kong and Taiwan. The EAC’s intra-Asia services were also included in the deal and were continued from Singapore through Maersk Line’s new subsidiary MCC Transport.

Containerization of the Europe/Asia Route

In the late 1970s it was decided to containerize the important Suez line running between Europe and Asia. The Suez line had originally been established in 1946, when the company experimentally let the ships that had sailed out on the Panama line return to the United States via South and Southeast Asia and the Red Sea. Footnote 31 With the decision to start a weekly independent container service between Asia and Europe ten new large container ships were ordered, and the organization in Western Europe was considerably strengthened. Long-held agency agreements were replaced with own country offices: Dublin in 1976, Paris in 1978 and Hamburg, Rotterdam and Antwerp in 1979. In addition, the company established its own local branch offices in Bremen, Düsseldorf, Nürnberg, Stuttgart, Frankfurt, Munich and Amsterdam. The European focus was gradually extended first to Scandinavia in 1985 with an owned office, Maersk Line (Sverige) AB, in Gothenburg and smaller, local branch offices in Stockholm and Helsingborg and then to Eastern Europe. With the continued expansion of Maersk Line in Europe new agency agreements were made with third-party providers in new countries, only to be replaced with own Maersk Line offices later on. In Helsinki, for example, an agreement was entered with OY Jacobsen Shipping Ltd in 1976 and replaced with an owned office in 1990. This stepping-stone approach was a means for Maersk Line to build up country experience in new markets that would later be used as lever for an own establishment.

Various documents related to the company’s Europe Project show that Belgium, The Netherlands and Germany formed the core of containerization of the Suez line. Footnote 32 Experienced Maersk employees were installed as Board of Directors and together with the newly appointed country managers were directly involved in hiring high-calibre senior people to lead the main functions of the three offices. The offices were also linked to the company’s new electronic systems that Maersk Data had developed in collaboration with Cable & Wireless in London for container management and documentation on the Panama line.

On Saturday, 28 June 1980, the country managers and senior people from the Europe offices together with the third-party agents in Switzerland, Denmark, Norway and Sweden were invited to a full-day information session in Copenhagen. Senior managers from Copenhagen and top officials from the advertising company Young & Rubicam also joined the meeting. On the program were the key elements in Maersk Line’s management philosophy: ships and operations, marketing and sales, financial management and the unique IT systems. Sales philosophy was a significant strategic directive for the company: Maersk Line should offer a superior service and be known as the prime alternative to the three large container consortia Trio, Scan Dutch and ACE Group, which controlled more than 90% of container shipping on Asia-Europe through the cartel-like Far Eastern Freight Conference (FEFC). Maersk Line’s partnership with Young & Rubicam was important and close. It was an integral part of getting the new container concept rolled out and marketed. Young & Rubicam had its own team of employees living and breathing for Maersk Line.

The World’s Most Profitable Container Shipping Line

In 1985, it was decided that Maersk Line should become ‘the most profitable international container transportation company in the world’. Footnote 33 This objective was to be achieved through first-class services, global coverage, and door-to-door services—three elements that from the beginning were captured in the motto ‘service all the way’. To achieve the objective required outstanding ships and equipment, well-trained and highly motivated employees, maximum cost-effectiveness, tailor-made customer services, and investments in specialized tonnage and equipment for niche markets. With the objective followed a genuine growth strategy to be pursued through a combination of increased transport frequency in existing markets and entry into new geographic markets. The growth would be based on the experiences with the containerization of the Panama line, and should preferably be organic.

The establishment of own offices in key locations were formalized in the company’s new growth strategy: ‘Maersk Line must have as an objective to be represented by their own agencies, where this is feasible’. The strategy included detailed plans for the establishment of new offices in Europe, Asia and Africa, and for each country a short comment was attached. Footnote 34 For Italy it was noted, for example, that the previously used agent was ‘owned and managed by aging Italians with no apparent dynamic crown princes’. For West Africa the note was more comprehensive: ‘The ongoing study by the Line Department is expected to lead to a positive conclusion on the establishment of own companies in Ivory Coast, Togo and maybe Senegal to achieve overall control and undertake direct sales, customer service, documentation and container control—possibly leaving vessels’ operations sub-contracted to existing agencies’.