- Sign into My Research

- Create My Research Account

- Company Website

- Our Products

- About Dissertations

- Español (España)

- Support Center

Select language

- Bahasa Indonesia

- Português (Brasil)

- Português (Portugal)

Welcome to My Research!

You may have access to the free features available through My Research. You can save searches, save documents, create alerts and more. Please log in through your library or institution to check if you have access.

Translate this article into 20 different languages!

If you log in through your library or institution you might have access to this article in multiple languages.

Get access to 20+ different citations styles

Styles include MLA, APA, Chicago and many more. This feature may be available for free if you log in through your library or institution.

Looking for a PDF of this document?

You may have access to it for free by logging in through your library or institution.

Want to save this document?

You may have access to different export options including Google Drive and Microsoft OneDrive and citation management tools like RefWorks and EasyBib. Try logging in through your library or institution to get access to these tools.

- Document 1 of 1

- More like this

- Scholarly Journal

HOMEWORK IN PRIMARY SCHOOL: COULD IT BE MADE MORE CHILD-FRIENDLY?

No items selected.

Please select one or more items.

Select results items first to use the cite, email, save, and export options

Homework plays a crucial role in the childhood environment. Teachers argue that homework is important for learning both school subjects and a good work ethic. Hattie (2013, p. 39) referenced 116 studies from around the world which show that homework has almost no effect on children's learning at primary school. Some studies have also found little effect on the development of a good work ethic or that homework may be counterproductive as children develop strategies to get away with doing as little as possible, experience physical and emotional fatigue, and lose interest in school (Cooper, 1989; Klette, 2007; Kohn, 2010). The present article argues that the practice of homework in Norwegian primary schools potentially threatens the quality of childhood, using Befring's (2012) five indicators of quality. These indicators are: good and close relationships, appreciation of diversity and variety, development of interest and an optimistic future outlook, caution with regards to risks, and measures to counteract the reproduction of social differences. The analysis builds on empirical data from in-depth interviews with 37 teachers and document analysis of 107 weekly plans from 15 different schools. The results show that the practice of homework potentially threatens the quality of childhood in all five indicators. The findings suggest that there is a needfor teachers to rethink the practice of homework in primary schools to protect the value and quality of childhood.

Homework, work-life balance, children's perspectives, quality indicators of childhood, work ethic

Introduction

Homework is defined as work teachers tell pupils to do outside of school hours (Cooper, 1989). Amounts of homework vary among teachers, schools, and countries. There's little data on how much time primary school pupils spend on homework, but according to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and various educational research partners there are large differences among countries in how much time 15-year-old students spend doing homework. These numbers are based on students' self-reports on time spent per week doing homework or other studying assigned by teachers (OECD, 2014). As seen in Fig. 1, Finland, Korea, and the Czech Republic are the three countries with the lowest reported weekly times spent on homework. Norway is in the middle.

These numbers are based on self-reporting from 15-year-old students, and we cannot be sure about the degree to which this is also the case for primary school pupils. In the case of Norway, numbers from the Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study (TIMSS) 2007 show that 50% of pupils in fourth grade spent less than 1 hour per day doing homework. A further 28% spent between 1 and 2 hours per day on homework, and 10% spent as much as 2-4 hours per day (Ronning, 2010).

In Norway, teachers are, in theory, free to choose whether or not to use homework with their students. At the same time, legislation instructs municipalities to provide 8 hours of homework support per week at school. Non-governmental organizations such as the Red Cross provide homework support to help children and families who have problems. It has also become big business to sell homework support to families who are struggling or who want something else from their family time.

Results from the TIMSS from 2003 to 2011 show that the volume of homework has increased over time (Valdermo, 2014). In 2009, Gronmo and Onstad presented TIMSS results showing that homework was corrected and given feedback by teachers to only a small extent. These authors argued that if homework is not corrected or connected to what is going on in the classroom it might leave the impression that homework is just something that should be done and not something from which to learn. They argued that Norwegian teachers should rethink homework in all subjects and make it more useful for learning (Gronmo & Onstad, 2009). What is surprising is that the idea of leaving an impression that homework is just something that should be done does not seem to be a problem that teachers and schools relate to. Doing something because it should be done is based on the idea that homework is a tool for teaching pupils a good work ethic. This is rarely mentioned in educational research and seldom subject to discussion. One explanation may be that schools as institutions have a strong need to maintain their hegemony and therefore feel endangered when academics ask critical questions about the school as an organization or about pedagogical practices (Aronowitz & Giroux, 1993). Apple (1982) argued that teachers and schools often blame problems on pupils or parents to avoid rethinking their practices. It is therefore of great academic importance to address these topics. The enormous gap in qualitative research on homework also makes it important to conduct research in this area.

Ronning's analyses of the TIMSS results for Norway from 2007 showed that pupils from low socioeconomic backgrounds who were assigned a large amount of homework had lower achievement than pupils with similar backgrounds who were assigned less homework. The study also showed that among the pupils who did homework, pupils with low socioeconomic backgrounds spent more time doing homework than pupils with high socioeconomic backgrounds did. There were also more pupils with low socioeconomic backgrounds who reported that they did not spend any time on homework (Ronning, 2010). This means the practice of homework has ethical issues that make it important to examine the practice in depth.

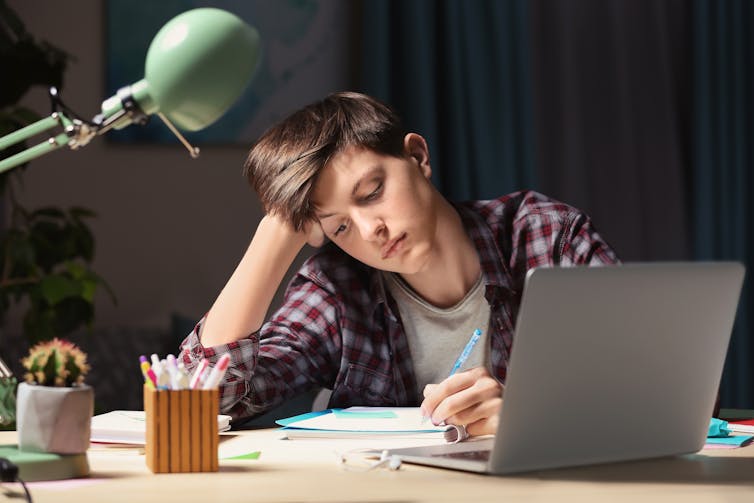

This article will present results showing how the practice of homework can endanger childhood in different ways. The health sector in Norway has reported an enormous increase in stress-related diseases among children over the past five years. It is now expected that 30% of children will have stress-related diseases during their childhood and that for 10-15% of them the disease will be so serious that they will need health services (Broyn 2016). After Hattie's (2013) findings, one cannot argue that this is the price we have to pay for children in primary school to learn, but some will argue that it is the price that must be paid to teach children a good work ethic. This article therefore includes reasoning about work ethics.

Before describing the present research, I will first consider what is implied by work ethics and consider previous research on homework and work ethics. I will then discuss Befring's (2012) five indicators of a high-quality childhood, namely:

1. Good and close relationships,

2. Appreciation of diversity and variety,

3. Development of interests and an optimistic future outlook,

4. Caution with regard to risks, and

5. Measures to counteract reproductive processes.

The Norwegian general curriculum states that "pupils' achievement is clearly influenced by the work habits acquired during their early years at school." Moreover, "good work habits developed at school have benefits far beyond the school framework." This is justified by the premise that school should prepare children for "the tasks of working and social life" (The Norwegian Directorate of Education and Training, 2015, p. 27). The curriculum does not describe what is meant by good work habits. So, what is meant by good work habits or a good work ethic and what does research say about the statement "pupils' achievement is clearly influenced by the work habits acquired during their early years at school"?

Work ethics are traditionally linked to adults' work and social lives. Weber laid much of the foundation for discussions of work ethics in his book The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism, published in 1904-5. The capitalist work ethic was then understood as the driving force behind industrialization, economic growth, and capitalism in North-west Europe and North America. A work ethic may be defined as "beliefs about the moral superiority of hard work over leisure or idleness, craft pride over carelessness, sacrifice over profligacy, earned over unearned income and positive over negative attitudes toward work" (Andrisani & Parnes, 1983, p. 104). Research has shown that the capitalist work ethic is now shared universally, albeit with cultural variations (Modrack, 2008, p. 7).

The capitalist work ethic consists of four dimensions. These are belief in hard work, avoidance of leisure, independence of others, and asceticism, i.e. abstaining from pleasure and enjoyment and even causing oneself distress. The same dimensions can be found in Islamic work ethics, but unlike capitalist ethics, here time is divided into three parts: one for rest, one for work, and one for religious, social, and family activities (Modrack, 2008; Rice, 1999; Shirokanova, 2015, p. 618). Good work ethics are also regarded as including not wasting time, being honest and diligent, persevering, and aiming at perfection.

Asian cultures are known to have high work ethics. A survey showed that one in five Japanese companies reported staff who are in danger of dying from overwork. "Karoshi" means death from overwork and such cases began being recorded in 1987. Every year, there are hundreds of deaths recorded as karoshi (E24, 2016).

The values of the capitalist work ethic have been criticized for not having any value in themselves but merely being an instrument for the reproduction of social inequality as a precondition for the organization of production in society (Juul, 2010; Befring, 2012). Increased production and economic growth have resulted in threats to the environment and people's health. The French philosopher André Gorz argued that a work ethic as we know it is passé and can no longer be said to be relevant to current or future work or society. He argued that such a work ethic has become obsolete and that it is no longer true that increased production means increased work or that increased production will lead to an improved way of life. According to Gorz, current and future working life and society require us to produce and work differently. In light of this perspective, two new approaches to work ethics have appeared: "a work-life balance" and "working smart" (Ford, 2014). So what does a work-life balance mean and can it be called a work ethic? A work-life balance approach to work ethics emphasizes, similarly as with Islamic work ethics, a division between focus at work and focus on being a human (Goleman, 2013). In Islamic work ethics, religion is the reason for doing various things during a day. With a work-life balance, activities are based on what research has found to be the most efficient for people to be able to focus on work and work smart when working. Research has concluded that a balance in life is important for efficiency. This approach differs from that of the capitalist work ethic, which emphasizes working as much as possible and that working more will help you work better. Since the main argument for a work-life balance is that it will make people more efficient, it shares the main goal of a capitalist perspective on work ethics. Research has shown that meditation, spending time in nature, and doing something truly enjoyable are the most important things we can do in our spare time in order to work smarter when we work (Goleman, 2013). For some people, this will mean activities such as spending time with family or friends, praying, and being outside. We see that this runs contrary to the familiar work ethic of working hard, disconnecting from nature, and avoiding anything that is fun or pleasurable.

There is research showing that homework can help pupils develop good work habits, such as following instructions, setting goals, organizing work, allocating time, and discovering strategies for dealing with mistakes, difficulties, and disturbances (Bempechat, 2004; Cooper et. al 2006; Corno & Xu, 2004) but the literature is not unambiguous. There are studies showing a negative correlation between homework and the acquisition of good work habits and work ethics. One literature review studying 100 articles and books about study techniques for pupils found that 88-95% were about organizing time, reading techniques, test preparation, and notetaking techniques (Hadwin & Tevaarwerk, 2004). It remains up for discussion how useful these skills are for students' future working lives. In a video observational study of a fifth-grade classroom, Klette (2007, p. 352) found that a group of observed boys had established what she called a minimum strategy culture regarding homework. She also found that some pupils finished their maths homework immediately and some procrastinated on it. There were few indications of pupils doing some work every day in accordance with the idea that long-term and repeated work would lead to good results. This study found that both students who did things quickly and those who procrastinated sometimes could go for up to 12 days before they did any maths after school hours. This shows the importance of being clear when assigning homework about what is actually meant by a good work ethic and good work habits.

Quality indicators of childhood

Childhood has two functions. First, it has great intrinsic value because of its essence that is fundamentally important to protect. Second, childhood is the foundation for personality development throughout life (Befring, 2012, p. 30). Although childhood is primarily part of the private family, it is also institutionalized in that the child spends considerable time at school. Children at primary school stand with one foot in their family and one foot in their school. Homework can be a tool to create cooperation between the two realms.

Befring (2012) introduced five quality indicators of childhood: good, close relationships and networks; appreciation of diversity and variety; development of interests and optimism; caution regarding risks; and prevention of reproductive processes. Most important for children are good, close relationships and networks. This implies that families need support and encouragement to manage their responsibilities. The family must have suitable working conditions for these responsibilities. It is important to emphasize that families are far less well prepared than school professionals are to work at learning tasks. The modern family is very serious about parenting, but it is stressful and demanding to combine this with work. There may also be financial or personal problems in the family.

Appreciation of diversity and variety is also an important indicator of a good childhood; this involves nurturing the particular qualities of each individual child. The greatest threat to this is what Befring calls the positivistic educational concept. This means one-dimensional teaching that tries to force all learners into a single mold, and Befring argues for renewal in this area. An important point is that children are not small adults. Children are very different from adults in terms of their perceptions of the world, their interests, and their activity and other life needs. Play is important in understanding children's basic characteristics (Befring, 2012). Good conditions for play can be very important for harmonious cognitive and socio-emotional learning and development (Smith, 2003; Dale, 1996).

The third indicator of a good childhood is the development of interests and optimism. Children need something to be involved and interested in, and this is where play and leisure activities are key. According to Vygotsky (1978), pleasure is the most significant feature of play. Play is also characterized by the creation of imaginary situations with imaginary activities. Because their actions are detached from the environment around them, children can act independently of what they perceive. When children play, they rise above the physical limitations of their environment. In play, the environment ceases to dominate the child. Play is a state where the child shakes off reality for a while and has the opportunity to try out ideas and realize wishes in "another kind of make-believe world" (Vygotsky, 1978). Because play is such an important part of childhood as well as being important for sound learning and development, it is essential to allow children time to play freely and to include the form and content of play in educational methods to some extent. The second part of this indicator is an optimistic outlook. The key here is experiences of mastery and the development of a belief in self-efficacy (Bandura, 1997).

With regard to children's interest, Montessori has presented some interesting perspectives. One of the most profound observations made by Montessori was that it is natural for children to work and that they love doing so (Montessori, 1936, 2009). She was convinced that children had hidden abilities that were overlooked by educators, and she spent her life trying to show how these abilities could be activated. Montessori found that children had great capacities for self-training as well as for concentration and self-discipline when their work suited their stage of development. She also noticed that children had a great ability to persevere and repeat activities. She viewed this as an internal resource for the child to retain and develop what was learned, noting that such an internal resource could not be forced. The teacher's role is crucial in this; according to Montessori, inner motivation is aroused by exploration and testing in school, nature, and the community.

Caution with regard to risk is the fourth indicator. Deadlocked issues in family interactions are a specific area where caution is needed. Families who experience such problems must not be left to themselves but need to receive help as soon as possible (Befring, 2012, p. 108). Another risk factor is learning difficulties, where early interventions are needed, tailored to the individual child.

The fifth and final indicator is about prevention in terms of systematic efforts to prevent harm, limit risks, strengthen children's resilience to risk, and provide support to those with unacceptable behavior. These points are generally relevant to homework, but it is perhaps more important to work proactively to prevent the reproduction of social inequality because of the enormous consequences involved.

This article is based on data from a qualitative study involving in-depth interviews of teachers and a document analysis of weekly plans for grades 1 to 7 at 15 primary schools in Norway. The purpose was to find out why and how primary school teachers assign homework. Data were collected in a pilot study in autumn 2012 and in a complete study in autumn 2015. All project participants in the project signed a consent form that guaranteed anonymity and informed them that the interview data would be used in research into homework practices.

Participants

Project participants were qualified teachers with primary school experience. All had experience with teacher-parent contact, except for one who was a subject teacher. Two participants also had further qualifications in special education. Two had become deputy heads and one was a headmaster. They were all asked to respond based on their experience as primary school teachers. There was a range of ages and years of experience. Each teacher interviewed was also asked to submit three weekly plans. All weekly plans were from the autumn term, as that was when the data were collected. Ten people were interviewed in 2012. Four interviews were lost because of problems with the recordings. Other work demands meant that it was three years before I had the opportunity to involve students in more research. In 2015, 32 additional teachers were interviewed. One teacher participated in both data collections. The analysis included 37 interviews; 26 interviewees were women (aged 30 to 67 years) and 11 were men (aged 28 to 62). Participants were from 15 schools, all of which were used for teaching practice by 0stfold University College.

The selection criterion for study participants was primary school teaching experience. One criterion for selection in 2015 was not having participated in the 2012 pilot study. This was to elicit a wide variety of responses, not because they could not provide important information after some time. I chose to include both interviews with the single informant who participated in both 2012 and 2015 because the questions were different between the two interviews. Using random sampling seemed to be a good strategy because students had been asked to find respondents at their training schools. I also assumed that most teachers could give valuable information about the topic.

First, the schools and training teachers were informed about the research project at an informational meeting at 0stfold University College. They were told that students would make contact to conduct interviews for the project. All informants worked at teaching practice schools, but not all were practice teachers. The students made contact and arranged for the interviews.

The study was based on a small sample of teachers and schools and thus does not provide a basis for generalization to all Norwegian schools or teachers. However, the design forms the basis for analytical generalization (Yin, 1994).

The criterion for selecting weekly plans was that they should represent ordinary weeks and the usual way of assigning homework. Informants could choose the weeks included. All of them submitted weekly plans except for one informant whose homework practice did not involve weekly plans.

The study might be criticized because students in basic courses were used as research assistants. There were many variables related to data collection over which I had no control. In 2012, I received the audio files and transcribed them myself. In 2015, in contrast, students submitted transcriptions from interviews, not audio files. This had the advantage of students gaining valuable experience by doing work for a real research project and reflecting on the topic at the same time as providing valuable data collection that could be used by undergraduate students as well as my colleagues and me. The final database was made available to one bachelor's degree student in 2013 and six in spring 2016. Student involvement enabled in-depth interviews with many more teachers from more schools than if I alone had been responsible for all data collection. To ensure optimal quality, students received a detailed introduction to the interview method and transcription with practical exercises. They were also provided with an interview guide and were asked to stick to the questions provided. At least two students conducted each interview together.

Semi-structured interviews

I decided to use semi-structured interviews to aid in the comparison of data emerging from the interviews. Two interview guides were used, one for each data collection. These were developed in a workshop in collaboration with the students who were to conduct the interviews, after which I assessed them for quality. The interview guide used in 2012 was slightly shorter and had rather more open questions on how and why homework was assigned. There were also questions about the respondent's attitude regarding the public debate about homework. This is why I call this study a pilot study. The 2015 interview guide was used to elaborate on some issues that arose after the data collection in 2012; these included opinions on a homework-free school, what were considered examples of good and bad homework, how respondents felt about the critical reflection on the practice of homework, and whether they felt they had real freedom in methods. It could be argued that using the same interview guide for both data collections would have been preferable, but, inspired by grounded theory (Glaser & Strauss, 1999), I chose to use the second data collection to go into greater detail on the data that had emerged from the first collection, which had been more like a pilot study.

With so many different interviewers, the quality of the interviews varied. In one of the interviews from 2012, one student went too far in asking leading questions to try to convince the given teacher that homework was not good. These efforts apparently did not affect the teacher's opinions, but it may have affected the clear way in which she expressed them. I believe that the asymmetry between the teachers and students in the interview was positive in that leading questions would influence the answers. As mentioned earlier, I lost four interviews from 2012 due to damaged audio files. In 2015, the transcriptions show that most interviewers did a good job of following the interview guide and asking follow-up questions. In some of the interviews, it was clear that the interviewer was not very committed to the questions. The atmosphere seemed somewhat formal and the answers were short and revealed little information. The interview guide encouraged interviewers to ask for examples and follow up answers. The transcriptions show that on several occasions they did so. Some interviews resulted in more information and stories than others did. I believe that would have been true in any case. All interviews were included in the data collection.

For this qualitative study, I chose a design that combined in-depth interviews with an analysis of weekly plans because sometimes informants provide in interviews a representation of their practice that is more politically correct or positive than a faithful description would be. Analyzing weekly notes in addition to the interviews should enhance the reliability of the study (Glaser & Strauss 1999).

Another way of ensuring reliability was collecting data on a larger scale after several years (Tjora, 2010). Expanding the range of teachers, grades, and schools has strengthened the data. To further enhance the data, I could have chosen to observe teachers' practice of assigning homework in the classroom and their meetings with parents, but this was not possible at the time. Klette (2007) has also used video observational studies to examine how work schedules are prepared and followed up. Interviews with pupils and their parents also could have provided a more comprehensive understanding. Such interviews are planned as well as potentially observations of pupils and parents. The analysis combined open, selective, and axial coding of the data (Robson, 2002).

In terms of work ethics, the results show that one reason for assigning homework to primary school pupils is to enable them to learn a good work ethic that would benefit them later in life. One teacher said, "I think about work ethics and making an effort and taking responsibility for homework ... because you can't get everythingforfree in this world and they need to find out that it costs something."

The results also show that the predominant way of assigning homework was in line with what Befring (2012) called the positivistic school tradition. Some teachers said that they practise in this way even though they do not think it is a good method. One teacher said:

We often base general homework on the textbooks. It gets to be very automatic. It would probably be a good idea to shake up that mindset a bit. It's been the samefor at least the 10 years I've been working.... You often just take the next three exercises in the book and assume that it's good enough homework.

Analysis of weekly plans shows that the most homework was assigned in Norwegian, mathematics, and English classes, with homework sometimes being assigned in religious education, social studies, and science classes and seldom or never in practical subjects such as arts and crafts, physical education, and food and health. The usual way of assigning homework is to assign the same work to all pupils in a class. Pupils with special needs often get their own weekly schedule; there are typically three or four of these per class. Homework is assigned on average 15 times per week to primary school pupils, regardless of age. Such homework primarily consists of reproducing information and is taken from the textbook or sheets of paper copied by teachers. Learning vocabulary, reading, words of the week, practice for dictation, handwriting, and sums are the most usual types of homework. "Revision of familiar material" is often the justification for the choice of exercises and the practice of homework. The consequences of not doing homework are reported as: being required to do it during a break, detention, a letter to parents, or no consequences at all. Analysis of the weekly plans also shows that it is the pure capitalist work ethic which is being cultivated, while we see no trace of elements such as meditation, being in nature, or doing something enjoyable. Rather, the results reveal scant appreciation of the value of what pupils really enjoy.

In terms of good, close relationships, several teachers mentioned pupils and parents who go too far when homework is to be done, meaning, for example, that the homework is done because the pupil has a guilty conscience or is afraid of negative consequences and/or that the parents push their children too hard. One teacher said, "It's not a matter of life and death to do the homework. It should only be done if it's a positive experience for the kids. You don't learn anything when mum and dad are sitting there yelling at their kids to do their maths." The interviews contained many examples of conflicts due to homework, often because it was difficult for students to get help at home. One teacher expressed this idea as follows:

You might have parents who force their child to sitfor two hours doing homework that they may not understand or that they find difficult because homework has to be "perfect" and "look nice". And that leads to a bad atmosphere and maybe some wet eyes, and then I kind of think you've gone a bit too far.

The results show that maths homework in particular made parents feel incompetent and inferior, and they contacted teachers about their challenges in helping their children. Some teachers stated that they had managed to create a good culture where parents were welcome to contact them and say they are having problems. Several said that such problems for parents normally increase with their child's age. They said that things are fine for most parents when their children are in first or second grade, that this is often followed by more problems from third to fifth grade, and that it can be very difficult for parents to help sixth and seventh graders and so the level of conflict increases.

The interviews reveal that many teachers found that families have problems with stress and time pressure after school hours due to recreational activities. Yet, the common perception is that pupils should spend 30-60 minutes per day on such activities.

With regard to the appreciation of diversity and variety, the results show that this is given little attention in homework practices; all pupils generally get assigned the same homework. In maths, pupils are sometimes allowed to choose the level of difficulty. Moreover, there may be voluntary exercises in addition to the mandatory ones. The type of homework does not vary much: great emphasis is placed on reading and writing in all subjects. Homework requires reproduction of knowledge rather than allowing pupils to involve their own world. There also seemed to be a widespread belief that homework should take priority over both family life and leisure activities. One teacher said, "I make it clear that homework should be given priority over other things. And if homework is neglected repeatedly, we contact the home."

Interests and a positive future outlook were also rarely catered to in homework practices. Pupils were mostly assigned the same homework irrespective of their level, leading to great variation in self-efficacy behavior. Responsibility for adapting work was usually handed over to pupils and parents; they had to contact the teacher if they thought the work was too much or too difficult. However, teachers' opinions of very good homework were that it should give pupils a feeling of mastery and be about topics they could investigate and find interesting. Very good homework, according to the teachers, should satisfy the following criteria:

* Be adapted to the pupil's interests and abilities.

* Provide challenges and opportunities for mastery.

* Include exciting, investigative work involving the student's house, family, or friends.

* Inspire creativity through drawing or technology.

In relation to caution regarding risk, some teachers said they are reluctant to be too hard on pupils who have not done their homework because they may have all sorts of reasons for not doing it. Some pupils have their own homework plan. None of the teachers took special account of differences between families before assigning homework; everyone was assigned the same work. Teachers had three different views of parents' role in homework. One group thought parents should not play any role and pupils must cope by themselves. For another group, the parents' role is to make pupils do homework and check if it has been done. A third group believed that parents should make pupils do homework and help them with it. They will find the solution, but few reflected on how homework poses a risk in itself because it is done outside of school hours in a learning environment that the teacher has little control over. There was a naive belief that the learning environment at home is better and quieter than that at school.

Teachers generally believed they could always find a solution for a pupil to get homework done or to do less. Few considered not assigning homework. This is illustrated in the following example:

Many of them have a hard time at home. Cramped space and no room for any good experiences around [homework]. You find marital breakups and lots of that difficult stuff when you mess around with people's spare time. So you need to be sensitive; I think that's really important. So we don't tellpeople what to do in their private lives. Then homework doesn't work in a positive way. Then you just have to react quickly.

Finally, the results revealed little reflection on the prevention of the reproduction of social inequality in homework practices. Nevertheless, many teachers mentioned examples of this. One problem is that parents are responsible for helping pupils and contacting the teacher about adapting work to their child; many will not call or will wait too long before contacting the teacher. One teacher explained that he is happy to get calls from parents who do not understand the homework:

There may be some who don't get so much help at home, and if they didn't understand it at school, then they struggle. I've had calls from parents asking if I can explain it to them because they didn't understand it themselves. It's mostly weak pupils who struggle, and their home may not be very nice, so they haven't got the knowledge to learn it. Then they ring me. I say, "If you have any questions, just ring me" We're a small school so I know most of them. So if they talk for 15 minutes, it's OK with me.

Another teacher explained how social inequalities could increase through homework: "The ones who have too many leisure activities care less about school.... And then it's the weakest ones who opt out of homework and the best educatedparents who might get even better pupils because they help their children to a very different degree"

This article examined how homework is used as an instrument to teach pupils a good work ethic and how this threatens a high-quality childhood. The results reveal a need for more child-friendly homework practices.

Good, close relationships

The results show that teachers clearly realized that homework can threaten good, close parent-child relationships because it may lead to conflicts. These conflicts are connected to finding time for homework, getting started, completing it, and sometimes how it should be done. This is consistent with findings from other studies. In a survey of 500 US parents, 30% reported that homework was one of the main sources of stress and disagreements in the family (Blazer, 2009). In another survey, 50% of parents reported discussions with their children about homework that involved crying and shouting, and 22% admitted that this frustration had led to their doing the homework for the child (Johnson et al., 2006).

If homework is to support good, close relationships between parents and children, it should not be excessive. It is also important that both parents and children perceive homework as being meaningful and useful. One way to achieve this could be to assign homework in different subjects, involving fewer repetitive exercises. Teachers are responsible for working out how homework can enhance child-parent relationships.

Appreciation of diversity and variety and the opportunity to develop interests and optimism

Kohn (2007) argued that most teachers assign homework based on a philosophy where they say, "We've decided ahead of time that children will have to do something every night (or several times a week), later on we'll figure out what to make them do." This involves little emphasis on choosing work that pupils will enjoy or benefit from or that will meet parents' need for information about their child's development.

Teachers have a clear idea of what is meant by very good homework. It should be adapted to the pupil's interests and abilities; provide challenges and opportunities for mastery; include exciting, investigative work involving the student's house, family, or friends; and encourage creative activity. The major challenge is what prevents teachers from assigning such homework. If these criteria are to be met, it will be difficult to assign all pupils the same homework. Pupils will have more influence on homework and the teacher will risk encountering resistance from colleagues and parents who want to maintain the old system. Given Montessori's theory of pupils' innate desire for learning and Vygotsky's arguments for the benefits of play, there are more than enough pedagogical arguments for the new criteria. Since arguments that traditional homework does not promote learning have been insufficient to change practice, teachers may lack arguments that very good homework encourages the kind of work ethic that work and society need and is in accordance with indicators of a good childhood. Parents could be told that the capitalist work ethic can also be learned at home or in leisure activities. Kohn (2007) argues that it is better to learn the value of repetition and hard work in leisure activities because it is easier to see the purpose of the practice and to achieve results quickly.

Instead of downplaying children's leisure time, teachers and parents should look to transfer its value to school. A Norwegian study found a positive correlation between school performance and sport participation among adolescents, while those who spent substantial time on computer games did well in English (Sletten, Strandbu, & Gilje, 2015).

Caution with regard to risks

One negative effect of homework is that parents often give inadequate or poor help. The current study shows that teachers have a varied set of parents to deal with. Berglyd (2003) divided parents into groups: positive, helpful, and skillful ones; critical ones; uncertain ones; irresponsible ones; and those with illnesses or problems. Educated parents can found be in all of these groups. All pupils are assigned the same homework, irrespective of such differences. In this regard, teachers show caution if a pupil has not done the homework, but not by adapting the content, translating the weekly newsletter for immigrant parents, or assigning no homework to children with sick parents or parents with bad experiences from their own schooling. What happens when simple homework such as the word of the week meets critical or uncertain parents? What happens when one pupil learns vocabulary with positive, well-educated parents, while other pupils learn it with uncertain parents? Clearly, the home and family is a variable that involves risk. In order to exercise caution in relation to this risk, it is necessary to assess when parents can definitely provide good help with homework. One teacher said that textbooks should include guidelines for parents to help them feel more secure about what they are doing. Another teacher distinguished between three levels of solving a task. The lowest level is when a pupil solves it by seeing others solve it. The second level is when a pupil can solve it by asking or cooperating with others. At the third level, the pupil can solve it alone. This could form the basis for what we might call confidence steps. Only when a pupil is at the third step can he or she do the work at home without being at risk of poor parental help. The key here is that pupils cannot be assigned the same homework, but their teacher must ensure the quality of their homework in advance. For example, parents should not be reading tutors for pupils who cannot read or who read with difficulty. The purpose of homework could be to inform parents of what the pupil is able to do. This way of thinking about confidence allows for more exploratory and creative tasks without definitive answers, while repetitive work is done at school with professional help.

Using these confidence steps could also help to prevent the school from reproducing social inequality, which is the fifth indicator of a good childhood. Self-instructive learning can be done at home. Several of the teaching aids originally created by Montessori are now available as apps and computer programs.

The results show that the practice of homework has a bias towards theory that needs to be remedied. Befring argued that pupils choosing vocational jobs may feel inferior and unhappy because they are not good at theory. He wrote that in practice, despite good policy goals, schools are organized such that pupils who will make important contributions to society through practical work must first fulfil educational duties where they are subdued and degraded (Befring, 2003, in Befring, 2012, p. 219). It is very important that homework is not practiced as such a duty but instead allows for diversity, variety, interest, and optimism for all pupils. In primary school, it is vital to consider how play and pleasure can be more prominent: if not at school, at least in leisure time. According to Vygotsky, this is important for children to be able to process their learning. Goleman argued that it is important to do something enjoyable so as to be able to focus better when it is time to work, even for adults. Montessori claimed that she had identified resources in children which teachers had not noticed. Perhaps some of these resources will become more visible if homework practices are based on children's perspectives.

This study reveals that the practice of homework in primary school rests on an ideology linked to the capitalist work ethic that there is good reason to reflect critically on. This work ethic threatens key quality indicators of childhood, such as good, close relationships; variety and diversity; optimism; caution regarding risk; and the prevention of reproductive processes. The capitalist work ethic has also outlived its usefulness for future society and working life (Ford 2014).

Homework is too widespread and risky to have key documents be unclear as to how and why it should be practiced. Educational plans should have a clear policy to ensure that homework also enhances pupils' health, wellbeing, and learning. In connection with this, the concept of confidence steps should be involved and homework should be linked to the three factors that lead to smarter work and a better work-life balance, namely meditation, time in nature, and doing something truly enjoyable (Goleman 2013).

There is still very little research on pupils' and parents' thoughts on why and how homework is practiced, and more research is clearly needed. Teachers in this study emphasized the enormous time pressure they are under, which means that pupils must do homework to complete the syllabus. Is the syllabus too big and the school day or year too short and, if so, is homework the ideal solution? This area also requires greater understanding and more research.

Andrisani P. J., & Parnes, H. S. (1983). Commitment to the work ethic and success in the labour market: A review of research findings. In J. Barbrush, R. J. Lampman, & S. A. Leviatan, et al. (Eds.), The work ethic. A critical analysis (pp. 101-120). Madison, WI: Industrial Relations Research Association Publications.

Apple, M. (1982). Education and Power. Boston: Routledge and Kegan Paul.

Aronowitz, S., & Giroux, H. (1993). Education still under siege (Second edition). Westport, Conneticut: Bergin and Garvin.

Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. New York: Freeman.

Bandura, A. (1999). A social cognitive theory of personality. In L. Pervin, & O. John (Ed.), Handbook of personality (Second edition) (pp. 154-196). New York: Guilford Publications.

Befring, E. (2012). Skolen for barnas beste: Kvalitetsvikar for oppvekst, læring og utvikling. [School for the childrens best: Quality indicators for upbringing, learning and development]. Oslo: Samlaget.

Bempechat, J. (2004). The motivational benefits of homework: A social-cognitive perspective. Theory Into Practice, 43(3), 189-196.

Berglyd, I. W. (2003). Skole og hjem samarbeid - avstand og nærhet. Bergen: Fagbokforlaget.

Blazer, Ch. (2009). Literature review homework. Miami, FL: Research services.

Broyn, T. (2016). Stress blant barn og unge. [Stress among children and young people]. Bedre Skole, (3), 38-40. Retrieved from https://www.utdanningsforbundet.no/upload/ Tidsskrifter/Bedre%20Skole/BS_3_2016/7724-BedreSkole-0316-Stress.pdf

Cooper, H. (1989). Homework. White Plains, NY: Longman.

Cooper, H., Robinson, J. C., & Patall, E. A. (2006). Does homework improve academic achievement? A synthesis of research, 1987-2003. Review of Educational Research, 76(1), 1-62.

Corno, L., & Xu, J. (2004). Homework as the job of childhood. Theory Into Practice, 43(3), 227-233.

Dale, E. L. (1996). Læring og utvikling - i lek og undervisning. In I. Braten (Ed.), Vygotsky i pedagogikken (pp. 43-73). Oslo: Cappelen Akademiske Forlag.

E24. (2016, October 9). Undersßkelse: Japanere'jobberseg tildode. [Research: Japanese work themselves to death]. Retrieved from http://e24.no/jobb/japan/undersoekelse-japanere-jobber-segtil-doede/23815775

Ford, N. (2014). "The crisis of work", by Andre Gorz Retrieved from http://abolishwork.com /2014/ 12/01/the-crisis-of-work-andre-gorz/

Glaser, B. G., & Strauss, R. D. (1999). The discovery of grounded theory. Strategies for qualitative research. New York: Routledge.

Goleman, D. (2013). Focus: The hidden driver of excellence. New Delhi: Bloomsbury Publishing India.

Gronmo, L. S., & Onstad, T. (2009). Tegn til bedring. Norske elevers prestasjoner i matematikk og naturfag i TIMSS 2007. Oslo: Unipub.

Hadwin, A., Tevaarwerk, K., & Ross, S. (2005). Are we teaching students to strategically self-regulate learning? A content analysis of 100 study skills textbooks. Paper presented at the Annual meeting of the American Educational Researchers Association, April 11-15, 2005, Montreal, QB.

Hattie, J. (2013). Synliglæring -forlærere. [Visible learning for teachers]. Oslo: Cappelen Damm Akademisk.

Johnson, J., Arumi, A. M., & Ott, A. (2006). Balancing the educational agenda. American Educator,, (Fall 2016), 18-26.

Klette, K. (2007). Bruk av arbeidsplaner i skolen - et hovedverktoy for a realisere tilpasset opplæring? [Workplans in school - a tool for individualizing education?]. Norsk Pedagogisk Tidsskrift, 91(4), 344-358.

Kohn, A. (2006). The homework myth. Why our kids get too much of a bad thing. Philadelphia, PA: First Da Capo Press.

Modrack, S. (2008). The protestant work ethic revisited: A promising concept or an outdated idea? (WZB discussion paper no. SP I 2008-101). Berlin, Germany: Social Science Research Center Berlin, research unit: Labour Market Policy and Employment.

Montessori, M. (1936, 2009). Barndommensgâte. [The mystery of Childhood., Original title: Il segreto dell'infanzia]. Oslo: Montessori Forlaget.

OECD. (2014). Table C7.4. Learning environment, by type of school (2012). In Education at a glance 2014: OECD Indicators (Chapter C: Access to education, participation and progression).

Rice, G. (1999). Islamic ethics and the implications for business. Journal of Business Ethics, 18(4), 345-358.

Robson, C. (2002). Real world research (Second edition). Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing.

Ronning, M. (2010). Homework andpupil achievement in Norway: Evidence from TIMSS. Retrieved from https://www.ssb.no/a/publikasjoner/pdf/rapp_201001/rapp_201001.pdf

Shirokanova, A. (2015). A comparative study of work ethic among Muslims and Protestants: Multilevel evidence. Social Compass, 62(4), 615-631.

Sletten, M. A., Strandbu, Ä., & Gilje, 0. (2015). Norsk Pedagogisk Tidsskrift, 99(5), 334-350.

Smith, P. K. (2003). Play and peer relations. In A. Slater, & G. Bremner (Eds.), An introduction to developmental psychology (pp. 311-333). Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing.

The Norwegian Directorate of Education and Training. (2015). Den generelle del av lærerplanen. [The general part of the curriculum]. Retrieved from http:// www.udir.no/laring-og-trivsel/ lareplanverket/generell-del-av-lareplanen/

Tjora, A. H. (2010). Kvalitative forskningsmetoder i praksis. Bergen: Fagbokforlaget.

Valdermo, O. H. (2014, May 7). Lekser i TIMMS og i norsk skole. Bedre Skole. Retrieved from http://utdanningsforskning.no/artikler/lekser-i-timss-og-i-norsk-skole/

Vygotsky, L. (1978). Mind in society. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Weber, M. (1995). Denprotestantiske etikk og kapitalismens and. Oslo: Pax Forlag.

Yin, R. (1994). Case study research. Design and methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

Corresponding author

Kjersti Lien Holte

Departement of Health and Social Science, 0stfold University College, Norway

E-mail: [email protected]

You have requested "on-the-fly" machine translation of selected content from our databases. This functionality is provided solely for your convenience and is in no way intended to replace human translation. Show full disclaimer

Neither ProQuest nor its licensors make any representations or warranties with respect to the translations. The translations are automatically generated "AS IS" and "AS AVAILABLE" and are not retained in our systems. PROQUEST AND ITS LICENSORS SPECIFICALLY DISCLAIM ANY AND ALL EXPRESS OR IMPLIED WARRANTIES, INCLUDING WITHOUT LIMITATION, ANY WARRANTIES FOR AVAILABILITY, ACCURACY, TIMELINESS, COMPLETENESS, NON-INFRINGMENT, MERCHANTABILITY OR FITNESS FOR A PARTICULAR PURPOSE. Your use of the translations is subject to all use restrictions contained in your Electronic Products License Agreement and by using the translation functionality you agree to forgo any and all claims against ProQuest or its licensors for your use of the translation functionality and any output derived there from. Hide full disclaimer

Copyright Masarykova Univerzita Filozofická Fakulta 2016

Suggested sources

- About ProQuest

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Policy

- Vyhledávání

Homework in Primary School: Could It Be Made More Child-Friendly?

Homework plays a crucial role in the childhood environment. Teachers argue that homework is important for learning both school subjects and a good work ethic. Hattie (2013, p.39) references 116 studies from around the world which show that homework has almost no effect on children’s learning at primary school. Some studies have also found little effect on the development of a good work ethic or that homework may be counterproductive as children develop strategies to get away with doing as little as possible, experience physical and emotional fatigue, and lose interest in school (Cooper, 1989; Klette, 2007; Kohn, 2010). The present article argues that the practice of homework in Norwegian primary schools potentially threatens the quality of childhood, using Befring’s (2012) five indicators of quality. These indicators are: (1) good and close relationships, (2) appreciation of diversity and variety, (3) development of interest and an optimistic future outlook, (4) caution with regards to risks, and (5) measures to counteract the reproduction of social differences. The analysis builds on empirical data from in-depth interviews with 37 teachers and document analysis of 107 weekly plans from 15 different schools. The results show that the practice of homework potentially threatens the quality of childhood in all five indicators. The findings suggest that there is a need for teachers to rethink the practice of homework in primary schools to protect the value and quality of childhood.

Klíčová slova

[1] Andrisani P. J., & Parnes, H. S. (1983). Commitment to the work ethic and success in the labour market: A review of research findings. In J. Barbrush, R. J. Lampman, & S. A. Leviatan, et al. (Eds.), The work ethic. A critical analysis (pp. 101–120). Madison, WI: Industrial Relations Research Association Publications.

[2] Apple, M. (1982). Education and Power. Boston: Routledge and Kegan Paul.

[3] Aronowitz, S., & Giroux, H. (1993). Education still under siege (Second edition). Westport, Conneticut: Bergin and Garvin.

[4] Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. New York: Freeman.

[5] Bandura, A. (1999). A social cognitive theory of personality. In L. Pervin, & O. John (Ed.), Handbook of personality (Second edition) (pp. 154–196). New York: Guilford Publications.

[6] Befring, E. (2012). Skolen for barnas beste: Kvalitetsvikår for oppvekst, læring og utvikling. [School for the childrens best: Quality indicators for upbringing, learning and development]. Oslo: Samlaget.

[7] Bempechat, J. (2004). The motivational benefits of homework: A social-cognitive perspective. Theory Into Practice, 43(3), 189–196. | DOI 10.1207/s15430421tip4303_4

[8] Berglyd, I. W. (2003). Skole og hjem samarbeid – avstand og nærhet. Bergen: Fagbokforlaget.

[9] Blazer, Ch. (2009). Literature review homework. Miami, FL: Research services.

[10] Brøyn, T. (2016). Stress blant barn og unge. [Stress among children and young people]. Bedre Skole, (3), 38–40. Retrieved from https://www.utdanningsforbundet.no/upload/Tidsskrifter/Bedre%20Skole/BS_3_2016/7724-BedreSkole-0316-Stress.pdf

[11] Cooper, H. (1989). Homework. White Plains, NY: Longman.

[12] Cooper, H., Robinson, J. C., & Patall, E. A. (2006). Does homework improve academic achievement? A synthesis of research, 1987–2003. Review of Educational Research, 76(1), 1–62. | DOI 10.3102/00346543076001001

[13] Corno, L., & Xu, J. (2004). Homework as the job of childhood. Theory Into Practice, 43(3), 227–233. | DOI 10.1207/s15430421tip4303_9

[14] Dale, E. L. (1996). Læring og utvikling – i lek og undervisning. In I. Bråten (Ed.), Vygotsky i pedagogikken (pp. 43–73). Oslo: Cappelen Akademiske Forlag. E24. (2016, October 9). Undersøkelse: Japanere jobber seg til døde. [Research: Japanese work themselves to death]. Retrieved from http://e24.no/jobb/japan/undersoekelse-japanere-jobber-segtil-doede/23815775

[15] Ford, N. (2014). " The crisis of work", by Andre Gorz. Retrieved from http://abolishwork.com/2014/12/01/the-crisis-of-work-andre-gorz/

[16] Glaser, B. G., & Strauss, R. D. (1999). The discovery of grounded theory. Strategies for qualitative research. New York: Routledge.

[17] Goleman, D. (2013). Focus: The hidden driver of excellence. New Delhi: Bloomsbury Publishing India.

[18] Grønmo, L. S., & Onstad, T. (2009). Tegn til bedring. Norske elevers prestasjoner i matematikk og naturfag i TIMSS 2007. Oslo: Unipub.

[19] Hadwin, A., Tevaarwerk, K., & Ross, S. (2005). Are we teaching students to strategically self-regulate learning? A content analysis of 100 study skills textbooks. Paper presented at the Annual meeting of the American Educational Researchers Association, April 11–15, 2005, Montreal, QB.

[20] Hattie, J. (2013). Synlig læring – for lærere. [Visible learning for teachers]. Oslo: Cappelen Damm Akademisk.

[21] Johnson, J., Arumi, A. M., & Ott, A. (2006). Balancing the educational agenda. American Educator, (Fall 2016), 18–26.

[22] Klette, K. (2007). Bruk av arbeidsplaner i skolen – et hovedverktøy for å realisere tilpasset opplæring? [Workplans in school – a tool for individualizing education?]. Norsk Pedagogisk Tidsskrift, 91(4), 344–358.

[23] Kohn, A. (2006). The homework myth. Why our kids get too much of a bad thing. Philadelphia, PA: First Da Capo Press.

[24] Modrack, S. (2008). The protestant work ethic revisited: A promising concept or an outdated idea? (WZB discussion paper no. SP I 2008-101). Berlin, Germany: Social Science Research Center Berlin, research unit: Labour Market Policy and Employment.

[25] Montessori, M. (1936, 2009). Barndommens gåte. [The mystery of Childhood., Original title: Il segreto dell'infanzia]. Oslo: Montessori Forlaget.

[26] OECD. (2014). Table C7.4. Learning environment, by type of school (2012). In Education at a glance 2014: OECD Indicators (Chapter C: Access to education, participation and progression).

[27] Rice, G. (1999). Islamic ethics and the implications for business. Journal of Business Ethics, 18(4), 345–358. | DOI 10.1023/A:1005711414306

[28] Robson, C. (2002). Real world research (Second edition). Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing.

[29] Rønning, M. (2010). Homework and pupil achievement in Norway: Evidence from TIMSS. Retrieved from https://www.ssb.no/a/publikasjoner/pdf/rapp_201001/rapp_201001.pdf

[30] Shirokanova, A. (2015). A comparative study of work ethic among Muslims and Protestants: Multilevel evidence. Social Compass, 62(4), 615–631. | DOI 10.1177/0037768615601980

[31] Sletten, M. A., Strandbu, Å., & Gilje, Ø. (2015). //Norsk Pedagogisk Tidsskrift, 99(5), 334–350.

[32] Smith, P. K. (2003). Play and peer relations. In A. Slater, & G. Bremner (Eds.), An introduction to developmental psycholog y (pp. 311–333). Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing.

[33] The Norwegian Directorate of Education and Training. (2015). Den generelle del av lærerplanen. [The general part of the curriculum]. Retrieved from http://www.udir.no/laring-og-trivsel/lareplanverket/generell-del-av-lareplanen/

[34] Tjora, A. H. (2010). Kvalitative forskningsmetoder i praksis. Bergen: Fagbokforlaget.

[35] Valdermo, O. H. (2014, May 7). Lekser i TIMMS og i norsk skole. Bedre Skole. Retrieved from http://utdanningsforskning.no/artikler/lekser-i-timss-og-i-norsk-skole/

[36] Vygotsky, L. (1978). Mind in society. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

[37] Weber, M. (1995). Den protestantiske etikk og kapitalismens ånd. Oslo: Pax Forlag.

[38] Yin, R. (1994). Case study research. Design and methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

Na tento článek odkazuje

- Aktuálně neexistují žádné citace.

Časopis Ústavu pedagogických věd FF MU . Výkonná redakce: Klára Šeďová, Roman Švaříček, Zuzana Šalamounová, Martin Sedláček, Karla Brücknerová, Petr Hlaďo. Redakční rada: Milan Pol (předseda redakční rady), Gunnar Berg, Inka Bormann, Michael Bottery, Elisa Calcagni, Hana Cervinkova, Eve Eisenschmidt, Ola Andres Erstad, Peter Gavora, Yin Cheong Cheng, Miloš Kučera, Adam Lefstein, Sami Lehesvuori, Jan Mareš, Jiří Mareš, Jiří Němec, Angelika Paseka, Jana Poláchová Vašťatková, Milada Rabušicová, Alina Reznitskaya, Michael Schratz, Martin Strouhal, Petr Svojanovský, António Teodoro, Tony Townsend, Anita Trnavčevič, Jan Vanhoof, Arnošt Veselý, Kateřina Vlčková, Eliška Walterová. Časopis vydává čtyři čísla ročně. ISSN 1803-7437 (print), ISSN 2336-4521 (online)

Information

- Author Services

Initiatives

You are accessing a machine-readable page. In order to be human-readable, please install an RSS reader.

All articles published by MDPI are made immediately available worldwide under an open access license. No special permission is required to reuse all or part of the article published by MDPI, including figures and tables. For articles published under an open access Creative Common CC BY license, any part of the article may be reused without permission provided that the original article is clearly cited. For more information, please refer to https://www.mdpi.com/openaccess .

Feature papers represent the most advanced research with significant potential for high impact in the field. A Feature Paper should be a substantial original Article that involves several techniques or approaches, provides an outlook for future research directions and describes possible research applications.

Feature papers are submitted upon individual invitation or recommendation by the scientific editors and must receive positive feedback from the reviewers.

Editor’s Choice articles are based on recommendations by the scientific editors of MDPI journals from around the world. Editors select a small number of articles recently published in the journal that they believe will be particularly interesting to readers, or important in the respective research area. The aim is to provide a snapshot of some of the most exciting work published in the various research areas of the journal.

Original Submission Date Received: .

- Active Journals

- Find a Journal

- Proceedings Series

- For Authors

- For Reviewers

- For Editors

- For Librarians

- For Publishers

- For Societies

- For Conference Organizers

- Open Access Policy

- Institutional Open Access Program

- Special Issues Guidelines

- Editorial Process

- Research and Publication Ethics

- Article Processing Charges

- Testimonials

- Preprints.org

- SciProfiles

- Encyclopedia

Article Menu

- Subscribe SciFeed

- Recommended Articles

- Google Scholar

- on Google Scholar

- Table of Contents

Find support for a specific problem in the support section of our website.

Please let us know what you think of our products and services.

Visit our dedicated information section to learn more about MDPI.

JSmol Viewer

Homework’s implications for the well-being of primary school pupils—perceptions of children, parents, and teachers.

.png)

1. Introduction

1.1. homework—perspectives of students, teachers, and parents, 1.2. homework practices in primary education in romania, 1.3. present study, 2. methodology, 2.1. design, data collection methods, and procedures, 2.2. participants, 2.3. data analysis, 3. research findings, 3.1. homework not liked by students.

| Learning Cycle | Students | Parents | Teachers |

|---|---|---|---|

| Classes I–II | - homework in the subject in which they are not doing well (61.5%); - for which they put a lot of effort (23.1%); - considered difficult (15.4%). | - that put them in difficulty (30%); - difficult, above their level of knowledge (30%); - in a discipline they do not prefer (20%); - for which they put a lot of effort (20%). | - repetitive (35.7%); - long and tiring (28.6%); - for which a lot of effort is put in (14.3%); - considered difficult (14.3%); - considered uninteresting (7.1%). |

| Classes III–IV | - for which they put a lot of effort (38.5%); - long and tiring (30.8%); - difficult (15.4%); - repetitive (7.7%); - with imposed limits (7.7%). | - for which they put a lot of effort (42.9%); - make students feel insecure about their strengths (14.3%); - with imposed limits (14.3%); - that are not appreciated (14.3%); - in a particular discipline they do not prefer (14.3%). | - for which they put effort (30.8%); - long and tiring (23.1%); - that put them in difficulty (23.1%); - repetitive (15.4%); - with imposed limits (e.g., compositions with given homework or a limited number of lines) (7.7%). |

3.2. Students’ Negative Reactions When Doing Homework

| Learning Cycle | Students | Parents | Teachers |

|---|---|---|---|

| Classes I–II | - feel bad and blame themselves for forgetting (50.0%); - are disappointed (37.5%); - get upset that they can’t go to play because they can’t finish promptly (12.5%). | - after calm discussions, they resume work even though they are disappointed (33.3%); - students cry when forced to do homework (16.7%); - students are disappointed (8.3%); - take a break and restart after (8.3%); - are stressed (8.3%); - lose patience (8.3%); - demotivate very quickly (8.3%); - categorically refuse to do them (8.3%). | - categorically refuse to do them (25.0%); - students cry when forced to do their homework (16.7%); - they intentionally forget their notebook at home (16.7%); - demotivate very quickly (8.3%); - get discouraged and ask their parents to help them (8.3%); - admit they don’t know, but try (8.3%); - get angry (8.3%); - take an interest in solving them (8.3%). |

| Classes III–IV | - feel bad and blame themselves for forgetting (36.4%); - gather frustrations (27.3%); - take a break and resume after (9.1%); - get discouraged and ask their parents to help them (9.1%); - take an interest in solving (9.1%); - lose confidence in their strength (9.1%). | - they gather frustration and close themselves off (50.0%); - I take a break and restart after (20.0%); - after calm discussions resume their work (10.0%); - get discouraged and ask their parents to help them (10.0%); - lose confidence in their strength (10.0%). | - honestly say they don’t know (16.7%); - refuse to solve their homework (16.7%); - are disappointed (16.7%); - get discouraged and ask their parents to help them (16.7%); - take a break and resume after (8.3%); - cry when forced to do their homework (8.3%); - they intentionally forget their notebook at home (8.3%); - students ask for help (8.3%). |

3.3. Homework That Makes Children Feel Good

| Learning Cycle | Students | Parents | Teachers |

|---|---|---|---|

| Classes I–II | - contain creative elements (visual arts or text composition) (50.0%); - who value them and feel appreciated (16.7%); - reading (8.3%); - by choice (8.3%). | - those preparing for competitions (71.4%); - those in preparation for classroom assessments (28.6%). | - involve the use of imagination (22.2%); - homework that makes students feel valued (22.2%); - appeal to real life (11.1%); - are related to practical things (11.1%); - homework to be checked with the teacher (11.1%); - negotiated with the teacher (11.1%); - in which a funny story is found (11.1%). |

| Classes III–IV | - involve the use of imagination (30.8%); - value them and feel appreciated (23.1%); - creative (23.1%); - increasing their self-confidence (15.4%); - appeal to real life (7.7%). | - make them feel appreciated (62.5%); - involves the use of imagination (12.5%); - are related to practical things (12.5%); - carried out as a team (12.5%). | - value them and feel appreciated (21.1%); - the projects they present to the class (15.8%); - for which they are rewarded (10.5%); - involve the use of imagination (5.3%); - homework that appeals to real life (5.3%); - changing the word “homework” to something else (5.3%); - in teams (5.3%); - investigation on a specific topic (5.3%); - creative (5.3%); - easy, which is effortless (5.3%); - in the form of debates (5.3%); - differentiated (5.3%); - increasing their self-confidence (5.3%). |

3.4. Homework Students Like

| Learning Cycle | Students | Parents | Teachers |

|---|---|---|---|

| Classes I–II | - in the form of reading or writing (35.7%); - contain creative elements (28.6%); - make them feel appreciated (14.3%); - preparation for evaluation (14.3%). | - Maths exercises (62.5%); - reading (25.0%); - projects (12.5%). | - practice (15.8%); - that they carry out on their own (15.8%); - are resolved in a relatively short time (15.8%); - attractive (10.5%); - contain creative elements (10.5%); - Maths exercises (10.5%); - in the form of gambling (10.5%); - reading or writing (5.3%); - arouse curiosity (5.3%). |

| Classes III–IV | - contain creative elements (35.3%); - reading (35.3%); - Maths exercises (11.8%); - attractive (5.9%); - short (5.9%); - projects (5.9%). | - Maths exercises (27%); - projects (18%); - bring creative elements (18%); - practice (9%); - team homework (9%); - are appreciated by teachers (9%). | - projects (27.3%); - appreciated by teachers and colleagues (13.6%); - short (13.6%); - are completed (9.2%); - involves creativity (9.1%); - not involving much effort (9.1%); - understood in the classroom (4.5%); - in teams (4.5%); - investigation (4.5%). |

3.5. Checking and Assessing Homework

| Learning Cycle | Students | Parents | Teachers |

|---|---|---|---|

| Classes I–II | - students correct their homework together with their classmates, guided by the teacher, and congratulate each other (38.5%); - positive or negative verbal comments are made (30.8%); - teachers give them rewards on checked homework, based on accuracy (15.4%); - homework is not checked daily and students become sad (7.7%); - they give themselves pluses and minuses (7.7%), being sure that they did (less/fairly) well. | - don’t know how the assessment and verification is done, but are notified if problems occur (33%); - homework is assessed and checked, and students’ work is validated (33%); - homework is not checked daily and students are sad, and disheartened (17%); - are rewarded with stickers and stickers, which are meant to make children happy (17%). | - give positive and constructive verbal feedback on homework (44.4%); - stickers, stickers as rewards (33.3%); - motivate students with good grades (22.2%). |

| Classes III–IV | - homework is checked and corrected individually (38.5%), bringing the satisfaction of a job well done; - students correct their homework together with their classmates, guided by the teacher, and congratulate each other (30.8%); - students don’t get their homework checked every day and students get sad (7.7%); - give themselves pluses and minuses (23%), being confident that they did (less/fairly) well. | - do not know how homework is checked and assessed, but are notified if something is wrong (50.0%); - homework is checked, but no daily assessment is given (37.5%); - check, then make notes (12.5%). | - assess homework by awarding grades (33.3%); - check and correct their homework in front (33.3%); - correct the homework, then put “seen” (11.1%); - check students out of homework when they take them to the blackboard (11.1%); - checks and corrects their homework individually (11.1%). |

3.6. Suggestions for Improving Educational Practices Regarding Homework

| Learning Cycle | Students | Parents | Teachers |

|---|---|---|---|

| Classes I–II | - creative homework (cutting, gluing, painting) (72.7%); - doing homework as a game (18.2%); - organization of team competitions (9.1%). | - some parents refrain and think teachers know better (33%); homework in the form of a game (22%); - team competition (11%); - participation in training courses (11%); - children should make suggestions, they are directly involved (11%); - story context (11%). | - creative homework (cutting, gluing, painting) (25.0%); - homework in the form of a game (16.7%); - presentation of attractive material on the Internet (16.7%); - alternating homework (16.7%); - making worksheets more attractive (16.7%); - replacing the word “homework” with something else (8.3%). |

| Classes III–IV | - homework in the form of a game (22.7%); - creative techniques (cutting, gluing, painting) (18.2%); - creative writing (13.6%); - documentation and elaboration of a project on a given homework (13.6%); - dividing the class into three groups and giving three types of homework (9.1%); -more attractive workplaces (9.1%); - creating cards with homework ideas (4.5%); - rewarding students (4.5%); - diversification of homework (4.5%); | - use of digital applications (25.0%); - homework in the form of a game (12.5%); - team projects (12.5%); - homework with a reference to modern-day reality (12.5%); - homework in the form of an experiment (12.5%); - homework in the form of competitions (12.5%); - some parents abstain (12.5%). | - rewarding students (12.5%); - better organization of after-school time (12.5%); - diversifying homework (12.5%); - children’s choice of homework (6.3%); - a good combination of modern and traditional methods (6.3%); - creating a suitable environment, free of distracting elements (6.3%); -giving homework in the form of more attractive worksheets (6.3%); - use of digital applications (6.3%); - presentation of attractive material online (6.3%); - not permitting the parent to intervene directly in the students’ homework (6.3%); - creative homework (cutting, gluing, painting) (6.3%); - homework in the form of competitions (6.3%); - homework in the form of a game (6.3%). |

4. Discussions

5. conclusions, author contributions, institutional reviewer board statement, informed consent statement, data availability statement, conflicts of interest.

- Rosário, P.; Núñez, J.C.; Vallejo, G.; Cunha, J.; Nunes, T.; Suárez, N.; Fuentes, S.; Moreira, T. The effects of teachers’ homework follow-up practices on students’ EFL performance: A randomized-group design. Front. Psychol. 2015 , 6 , 1528. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Williams, K.; Swift, J.; Williams, H.; Van Daal, V. Raising children’s self-efficacy through parental involvement in homework. Educ. Res. 2017 , 59 , 316–334. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Tam, V.C.; Chu, P.; Tsang, V. Engaging in self-directed leisure activities during a homework-free holiday: Impacts on primary school children in Hong Kong. J. Glob. Educ. Res. 2023 , 7 , 64–80. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Moorhouse, B.L. Qualities of good homework activities: Teachers’ perceptions. ELT J. 2021 , 75 , 300–310. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- McGuire, S.Y.; McGuire, S. Teach Students How to Learn: Strategies You Can Incorporate into Any Course to Improve Student Metacognition, Study Skills, and Motivation , 1st ed.; Stylus Publishing: Sterling, VA, USA, 2015. [ Google Scholar ]

- Sayers, J.; Petersson, J.; Marschall, G.; Andrews, P. Teachers’ perspectives on homework: Manifestations of culturally situated common sense. Educ. Rev. 2020 , 74 , 905–926. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Norhayati, E.; Rahya, R. Teacher’s Strategy in Shaping the Responsible Character of the Primary School Students toward Homework. Indones. J. Prim. Educ. Res. 2023 , 1 , 36–44. Available online: https://ejournal.aecindonesia.org/index.php/IJPER/article/view/6 (accessed on 2 June 2023).

- Negru, I.; Sava, S. Reflections, perceptions and practices in formulating and evaluating homework in primary education. J. Pedag. 2022 , 52 , 93–120. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Dolean, D.D.; Lervåg, A.; Visu-Petra, L.; Melby-Lervåg, M. Language skills, and not executive functions, predict the development of reading comprehension of early readers: Evidence from an orthographically transparent language. Read. Writ. 2021 , 34 , 1491–1512. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Syla, L.B. Perspectives of Primary Teachers, Students, and Parents on Homework. Educ. Res. Int. 2023 , 7669108. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Moè, A.; Katz, I.; Cohen, R.; Alesi, M. Reducing homework stress by increasing adoption of need-supportive practices: Effects of an intervention with parents. Learn. Individ. Differ. 2020 , 82 , 101921. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Rodríguez, S.; González-Suárez, R.; Vieites, T.; Piñeiro, I.; Díaz-Freire, F.M. Self-Regulation and Students Well-Being: A Systematic Review 2010. Sustainability 2022 , 14 , 2346. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Dettmers, S.; Yotyodying, S.; Jonkmann, K. Antecedents and Outcomes of Parental Homework Involvement: How Do Family-School Partnerships Affect Parental Homework Involvement and Student Outcomes? Front. Psychol. 2019 , 10 , 1048. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Epstein, J.L.; Van Voorhis, F.L. More Than Minutes: Teachers’ Roles in Designing Homework. Educ. Psychol. 2001 , 36 , 181–193. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Medwell, J.; Wray, D. Primary homework in England: The beliefs and practices of teachers in primary schools. Int. J. Prim. Elem. Early Years Educ. 2018 , 47 , 191–204. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Rodríguez, S.; Núñez, J.C.; Valle, A.; Freire, C.; Ferradás, M.d.M.; Rodríguez-Llorente, C. Relationship Between Students’ Prior Academic Achievement and Homework Behavioral Engagement: The Mediating/Moderating Role of Learning Motivation. Front. Psychol. 2019 , 10 , 1047. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- De Róiste, A.; Kelly, C.; Molcho, M.; Gavin, A.; Nic Gabhainn, S. Is school participation good for children? Associations with health and wellbeing. Health Educ. 2012 , 112 , 88–104. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- OECD. Measuring What Matters for Child Well-Being and Policies ; OECD: Paris, France, 2021. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]