Choose Your Test

- Search Blogs By Category

- College Admissions

- AP and IB Exams

- GPA and Coursework

4 Top Tips for Writing Stellar MIT Essays

College Essays

For the 2021-2022 admissions cycle, MIT admitted about 4% of applicants. If you want to be one of these lucky few, you'll need to write some killer MIT essays as part of your own Massachusetts Institute of Technology application.

In this article, we'll outline the MIT essay prompts and teach you how to write MIT supplemental essays that will help you stand out from the thousands of other applicants.

What Are the MIT Essays?

Like most major colleges and universities, MIT requires its applicants to submit essay examples as part of your application for admission.

MIT has its own application and doesn't accept the Common Application or the Coalition Application. The MIT essay prompts you'll answer aren't found on any other college's application.

There are four MIT supplemental essays, and you'll need to answer all four (approximately 200 words each) on various aspects of your life: a description of your background, what you do for fun, a way that you contribute to your community, and a challenge that you have faced in your life.

The MIT essay prompts are designed specifically to get to the heart of what makes you you . These essays help the admissions committee get a holistic picture of you as a person, beyond what they can learn from other parts of your application.

2022-2023 MIT Essay Prompts

The MIT supplemental essays are short, and each one addresses a different aspect of your identity and accomplishments.

You'll submit your essays along with an activities list and a self-reported coursework form as Part 2 of your MIT application. MIT structures its application this way because they rely on a uniform application to help them review thousands of applicants in the most straightforward and efficient way possible.

You need to respond to all five of the MIT essay prompts for your application.

Here are the 2022-2023 MIT essay prompts:

We know you lead a busy life, full of activities, many of which are required of you. Tell us about something you do simply for the pleasure of it.

Describe the world you come from (for example, your family, school, community, city, or town). How has that world shaped your dreams and aspirations?

MIT brings people with diverse backgrounds and experiences together to better the lives of others. Our students work to improve their communities in different ways, from tackling the world’s biggest challenges to being a good friend. Describe one way you have collaborated with people who are different from you to contribute to your community.

Tell us about a significant challenge you’ve faced (that you feel comfortable sharing) or something that didn’t go according to plan. How did you manage the situation?

Now that we know what the prompts are, let's learn how to answer them effectively.

MIT Essays, Analyzed

In this section, we'll be looking at each of the five MIT essays in depth.

Remember, every applicant must answer every one of the MIT essay prompts , so you don't get to choose which essay you would like to write. You have to answer all five of the MIT essay prompts (and do so strongly) in order to present the best application possible.

Let's take a look at the five MIT supplemental essay questions and see what the admissions committee wants to hear from each.

MIT Essay Prompt #1

This MIT essay prompt is very broad. The structure of the prompt indicates that the committee is interested in learning about your curiosity inside and outside of the classroom, so don't feel like you have to write about your favorite parts of school.

This MIT essay is your opportunity to show a different side of your personality than the admissions committee will see on the rest of your application. This essay is your chance to show yourself as a well-rounded person who has a variety of different interests and talents.

Choose a specific activity here. You don't need to present a laundry list of activities—simply pick one thing and describe in detail why you enjoy it. You could talk about anything from your love of makeup tutorials on YouTube to the board game nights you have with your family. The key here is to pick something that you're truly passionate about.

Don't feel limited to interests relating to your potential major. MIT's second prompt is all about that, so in this first prompt forget about what the school "wants to read" and be yourself! In fact, describing your experience in or passion for a different field will better show that you're curious and open to new ideas.

MIT Prompt #2

Don't repeat information that the committee can find elsewhere on your application. Take the time to share fun, personal details about yourself.

For instance, do you make awesome, screen-accurate cosplays or have a collection of rock crystals from caving expeditions? Think about what you love to do in your spare time.

Be specific—the committee wants to get a real picture of you as a person. Don't just say that you love to play video games, say exactly which video games you love and why.

MIT wants to know about your community—the friends, family, teammates, etc. who make up your current life. All of those people have affected you in some way—this prompt is your chance to reflect on that influence and expand on it. You can talk about the deep bonds you have and how they have affected you. Showing your relationships to others gives the committee a better idea of how you will fit in on MIT's campus.

All in all, this MIT essay is a great opportunity to have some fun and show off some different aspects of your personality. Let yourself shine!

MIT Prompt #3

This MIT prompt is by far the most specific, so be specific in your answer. Pick one experience that's meaningful to you to discuss here. The prompt doesn't specify that you have to talk about something academic or personal. It can be anything that you've done where you have contributed to any community—your dance troupe, gaming friends, debate team teammates. A community can be anything; it doesn't just refer to your hometown, scholastic or religious community.

The trick to answering this prompt is to find a concrete example and stick to it.

Don't, for instance, say that you try to recycle because the environment is meaningful to you, because it won't sound sincere. Rather, you can talk about why picking up garbage in the park where you played baseball as a child has deeper meaning because you're protecting a place that you've loved for a long time. You should talk about something that is uniquely important to you, not the other thousands of students that are applying to MIT.

Pick something that is really meaningful to you. Your essay should feel sincere. Don't write what you think the committee wants to hear. They'll be more impressed by a meaningful experience that rings true than one that seems artificial or implausible.

MIT Prompt #4

This question sets you up for success: it targets your area of interest but doesn't pigeon-hole you.

This essay is where your formal education will be most important. They want to know what kind of academic life you may lead in college so keep it brief, but allow your excitement for learning to drive these words. You are, after all, applying to MIT—they want to know about your academic side.

You should demonstrate your knowledge of and affinity for MIT in this essay. Don't just say that you admire the MIT engineering program—explain exactly what it is about the engineering program that appeals to you.

You can call out specific professors or classes that are of interest to you. Doing so helps show that you truly want to go to MIT and have done your research.

If you love playing games with kids at the Boys & Girls Club, the third MIT essay prompt is the time to talk about that passion.

MIT Open-Ended Text Box

This is one of the most open-ended options that you'll find on a college application! Here's one last chance for you to let MIT get to know the real you—the you that didn't quite get to come out during the previous four essays.

MIT wants to know exactly who you are, but, just as a word of caution, make sure your answer is appropriate for general audiences.

How to Write a Great MIT Essay

Regardless of which MIT essay prompt you're responding to, you should keep in mind the following tips for how to write a great MIT essay.

#1: Use Your Own Voice

The point of a college essay is for the admissions committee to have the chance to get to know you beyond your test scores, grades, and honors. Your admissions essays are your opportunity to make yourself come alive for the essay readers and to present yourself as a fully fleshed out person.

You should, then, make sure that the person you're presenting in your college essays is yourself. Don't try to emulate what you think the committee wants to hear or try to act like someone you're not.

If you lie or exaggerate, your essay will come across as insincere, which will diminish its effectiveness. Stick to telling real stories about the person you really are, not who you think MIT wants you to be.

You're the star of the show in your MIT essays! Make sure your work reflects who you are as a student and person, not who you think the admissions committee wants you to be.

#2: Avoid Clichés and Overused Phrases

When writing your MIT essays, try to avoid using clichés or overused quotes or phrases.

These include quotations that have been quoted to death and phrases or idioms that are overused in daily life. The college admissions committee has probably seen numerous essays that state, "You miss a hundred percent of the shots you don't take." Strive for originality.

Similarly, avoid using clichés, which take away from the strength and sincerity of your work.

Your work should be straightforward and authentic.

#3: Check Your Work

It should almost go without saying, but you want to make sure your MIT essays are the strongest example of your work possible. Before you turn in your MIT application, make sure to edit and proofread your essays.

Your work should be free of spelling and grammar errors. Make sure to run your essays through a spelling and grammar check before you submit.

It's a good idea to have someone else read your MIT essays, too. You can seek a second opinion on your work from a parent, teacher, or friend. Ask them whether your work represents you as a student and person. Have them check and make sure you haven't missed any small writing errors. Having a second opinion will help your work be the best it possibly can be.

#4: Demonstrate Your Love for MIT

MIT's five essay prompts are specific to MIT. Keep that in mind as you're answering them, particularly when you attack prompt two.

Show why MIT is your dream school—what aspects of the education and community there are most attractive to you as a student.

MIT receives thousands of applications, from students who have different levels of interest in the university.

The more you can show that you really want to go to MIT, the more the school will be interested in your application. Your passion for MIT may even give you a leg up on other applicants.

What's Next?

Exploring your standardized testing options? Click here for the full list and for strategies on how to get your best ACT score .

Are you happy with your ACT/SAT score, or do you think it should be higher? Learn what a good SAT / ACT score is for your target schools .

Your MIT essays are just one part of your college application process. Check out our guide to applying to college for a step-by-step breakdown of what you'll need to do.

Trending Now

How to Get Into Harvard and the Ivy League

How to Get a Perfect 4.0 GPA

How to Write an Amazing College Essay

What Exactly Are Colleges Looking For?

ACT vs. SAT: Which Test Should You Take?

When should you take the SAT or ACT?

Get Your Free

Find Your Target SAT Score

Free Complete Official SAT Practice Tests

How to Get a Perfect SAT Score, by an Expert Full Scorer

Score 800 on SAT Math

Score 800 on SAT Reading and Writing

How to Improve Your Low SAT Score

Score 600 on SAT Math

Score 600 on SAT Reading and Writing

Find Your Target ACT Score

Complete Official Free ACT Practice Tests

How to Get a Perfect ACT Score, by a 36 Full Scorer

Get a 36 on ACT English

Get a 36 on ACT Math

Get a 36 on ACT Reading

Get a 36 on ACT Science

How to Improve Your Low ACT Score

Get a 24 on ACT English

Get a 24 on ACT Math

Get a 24 on ACT Reading

Get a 24 on ACT Science

Stay Informed

Get the latest articles and test prep tips!

Hayley Milliman is a former teacher turned writer who blogs about education, history, and technology. When she was a teacher, Hayley's students regularly scored in the 99th percentile thanks to her passion for making topics digestible and accessible. In addition to her work for PrepScholar, Hayley is the author of Museum Hack's Guide to History's Fiercest Females.

Ask a Question Below

Have any questions about this article or other topics? Ask below and we'll reply!

What should I go with for MIT essay prompt: "What do you do for fun?"

The MIT application has a question that asks “We know you lead a busy life, full of activities, many of which are required of you. Tell us about something you do for the pleasure of it.”

I’m having trouble deciding between talking about drawing/painting or novel-writing. I have lots of creative writing awards on the national and state level, and lots of literary EC’s as well. My love for writing is going to be a major component of my application.

On the other hand, art won’t appear anywhere else on my application. It’s something I genuinely enjoy, plus I’ve sold some commissions and won very minor awards, but I haven’t taken an art class at school since freshman year and I don’t have any EC’s for it. I don’t know if talking about this is going to provide another angle on who I am, or make me look disorganized/disingenuous.

However, mentioning how I like to write might just be redundant here, since it’s proven over and over in other facets of my application.

Which one should I choose? Or should I go with a completely different topic (badminton, blogging, etc.)?

The only wrong answer would be to write about something that you don’t actually do for fun. Give a shot at both essays and see which one you like better. There’s no definitive answer here.

Anything you want to write about is fine. That is kind of the point. Use it to tell the school something new and interesting about yourself.

How about what you REALLY do for fun rather than what item you think puts you in the best light for your essay reader? Sincerity has a quality all its own. That’s the purpose of this essay – not seeing how you can beef up one of your ECs or traits.

I’d like to clarify that I like to do both of these things for fun. However, I only can choose to submit an essay about one of these things in the end.

Thanks to everybody for the advice, though! I can see how this would be something that depends on each individual applicant, and there’s no “right” or “wrong” answer. I’ll probably write both essays and see.

What makes you laugh and fills you with joy? What gives you stress relief? If it is something silly or quirky that is fine.

The point of the exercise is that YOU answer the prompt…isn’t it? So, use what got you to this point and build on it. You could also use a couple of beginning lines that might lead to a few more words, such as: “It was the funnest of times, it was the worst of times”, or the always popular “Call me Ishmael”.

What are your chances of acceptance?

Calculate for all schools, your chance of acceptance.

Your chancing factors

Extracurriculars.

5 Marvelous MIT Essay Examples

What’s covered:, essay example #1 – simply for the pleasure of it, essay example #2 – overcoming challenges, essay example #3 – dreams and aspirations, essay example #4 – community at a new school, essay example #5 – community in soccer.

- Where to Get Feedback on Your MIT Essay

Sophie Alina , an expert advisor on CollegeVine, provided commentary on this post. Advisors offer one-on-one guidance on everything from essays to test prep to financial aid. If you want help writing your essays or feedback on drafts, book a consultation with Sophie Alina or another skilled advisor.

MIT is a difficult school to be admitted into; a strong essay is key to a successful application. In this post, we will discuss a few essays that real students submitted to MIT, and outline the essays’ strengths and areas of improvement. (Names and identifying information have been changed, but all other details are preserved).

Read our MIT essay breakdown to get a comprehensive overview of this year’s supplemental prompts.

Please note: Looking at examples of real essays students have submitted to colleges can be very beneficial to get inspiration for your essays. You should never copy or plagiarize from these examples when writing your own essays. Colleges can tell when an essay isn’t genuine and will not view students favorably if they plagiarized.

Prompt: We know you lead a busy life, full of activities, many of which are required of you. Tell us about something you do simply for the pleasure of it.

After devouring Lewis Carrolls’ masterpiece, my world shifted off its axis. I transformed into Alice, and my favorite place, the playground, became Wonderland. I would gallivant around, marveling at flowers and pestering my parents with questions, murmuring, “Curiouser and curiouser.” If Alice’s “Drink Me” potion was made out of curiosity, I drank liters of it. Alice, along with fairytale retellings like the Land of Stories by Chris Colfer, kickstarted my lifelong love of reading.

Especially when I was younger, reading brought me solace when the surrounding world was filled with madness (and sadly, not like the fun kind in Alice in Wonderland ). There are so many nonsensical things that happen in the world, from shootings at a movie theater not thirty minutes from my home, to hate crimes targeted towards elderly Asians. Reading can be a magical escape from these problems, an opportunity to clear one’s mind from chaos.

As I got older, reading remained an escape, but also became a way to see the world and people from a new perspective. I can step into so many different people’s shoes, from a cyborg mechanic ( Cinder ), to a blind girl in WWII’s France (Marie-Laure, All the Light We Cannot See ). Sure, madness is often prevalent in these worlds too, but reading about how these characters deal with it helps me deal with our world’s madness, too.

Reading also transcends generational gaps, allowing me to connect to my younger siblings through periodic storytimes. Reading is timeless — something I’ll never tire of.

What the Essay Did Well

This essay is highly detailed and, while it plays off a common idea that reading is an escape, the writer brings in personal examples of why this is so, making the essay more their own. These personal examples often include strong language (e.g. “devoured,” “gallivant,” “pestering” ), which make the imagery more vivid, the writing more interesting. More advanced language can add more nuance to an essay– instead of “ate,” the writer chooses to say “devoured, ” and you can almost see the writer taking the book in almost as quickly as they might polish off a tray of cookies.

The writer also discusses how reading can not only be a solace from events that seem nonsensical, but a way to understand the madness in these events. By giving two different examples of how this can be so, that seem so varied from each other (the cyborg mechanic and the girl in WWII’s France), the writer creates more depth to this idea.

What Could Be Improved

At the beginning, the writer should consider cutting the introduction paragraph by a line to leave more room for the two major points of the essay in the following paragraphs. Instead of a long sentence about a love of reading being kickstarted, the writer could create a short, powerful sentence to kick off the next two paragraphs. “I was in love with reading.”

The detail at the end about how reading also transcends generational gaps seems like an add-on that doesn’t connect to the past two ideas– instead, I would suggest that this author expand a little more on the prior two ideas and tie them together at the end. “In this timeless world of reading, I can keep drinking from the well of curiosity. In the pages of a book, I have a space to find out more about the world around me, process its events, and more deeply understand others.”

Prompt: Tell us about the most significant challenge you’ve faced or something important that didn’t go according to plan. How did you manage the situation?

“It’s… unique,” they say.

I sag, my younger sister’s koala drawing staring at me from the wall. It always seemed like her art ended up praised and framed, while mine ended up in the trash can when I wasn’t looking. In contrast to my sister, art always came as a bit of a struggle for me. My bowls were lopsided and my portraits looked like demons. Many times, I’ve wanted to scream and quit art once and for all. I craved my parents’ validation, a nod of approval or a frame on the wall.

Eventually, my art improved, and I made some of my favorite projects, from a ceramic haunted house to mushroom salt-and-pepper shakers. Even then, I didn’t get much praise from my parents, but I realized I genuinely loved art. It wasn’t something I enjoyed because of others’ praise; I just liked creating things of my own and the inexplicable thrill of chasing a challenge. Art has taught me to love failing miserably at something to continue it again the next day. If I never endured countless Bob Ross tutorials, I never would’ve made the mountain painting that I hang in my room today; if I never made pottery that blew up (just once!), I wouldn’t have my giant ceramic pie.

I’m still light years from being an expert, but I’ll never tire of the kick of a challenge.

The detail about the sister’s koala drawing being framed and praised while this writer’s portraits look like “demons” and bowls “lopsided” draws a nice contrast between the skills of the sister versus those of the writer. In response to this “Overcoming Challenges” prompt , the author justifies that this is a significant challenge by saying that they “wanted to scream and quit art once and for all” and that they still desired their parents’ approval.

The writer’s response to the situation—taking more tutorials online, creating many different pots before getting it right–is nicely framed. Many times, students forget to include examples that demonstrate how they respond to the situation, and this writer does a good job of including some of those details.

The writer seems to emphasize the parents’ approval piece in the first paragraph, but then moves away from that point more to focus on the “thrill of chasing a challenge.” This essay could be improved by focusing a little more on how the writer emotionally moved past not getting that approval “Even then, I didn’t get much praise from my parents, but I finally realized I didn’t need to focus on that. I could focus on my love of art, on the inexplicable thrill of chasing the challenge…”

Additionally, the sentence that starts with “Eventually, my art improved…” leaves the reader with the ques tion– how? Saying something like “Eventually, after many YouTube tutorials and a few destroyed pots, my art improved” would add detail, without taking away from the sentence about the Bob Ross tutorials and the pot blowing up.

Prompt: Describe the world you come from (for example, your family, school, community, city, or town). How has that world shaped your dreams and aspirations? (225 words)

When the school bell rang, I jumped on my bike and sped home to watch the Tom and Jerry cartoon. I took off my school uniform and sat in the living room, pressing the remote’s power button. I pressed it again frantically, feeling another heart drop as the screen remained black. “Oh my God,” I sobbed as I rushed up to ensure that all wires were properly plugged into their respective sockets, but the screen was still black.

I unplugged the television, disassembled it, and examined every component, starting with the power switch. I’ve been tinkering with old radios for a long time, so I easily realized that a power surge had destroyed its capacitor. I replaced it with one from my radio, and the TV turned on immediately. While I couldn’t watch the cartoon, fixing the TV not only made me happy, but it also piqued my interest in the digital world. I began looking into technical opportunities in my community, starting with a nearby repairing shop, where I became acquainted with electronic devices: smart phones, laptops, televisions, and printers. Today, if I’m not repairing people’s electronics, I’m amazed by integrating broken gadgets.

This writer does an excellent job of addressing the “dreams and aspirations” line of this prompt. They clearly describe how their interest in technology emerged, in a well-paced, energetic way that makes us readers vicariously feel their passion and excitement.

Additionally, introducing us to their love of repairing electronics through the seemingly mundane event of their TV not working is a smart choice, for two reasons:

- Everyone has experienced their TV, phone, laptop, etc. not working, so this story helps readers relate to the student

- They go on to talk about how they used their newfound skill to help others, and thus portray themselves as someone who views even the simplest occurrence as an opportunity to make the world better

Obviously, one of the main goals of the college essay is to connect with admissions officers, to get them personally invested in your story and, by extension, excited about your potential as an MIT student. Being relatable is one of the best ways to build that connection.

And, of course, MIT wants to accept students who are going “to advance knowledge and educate students in science, technology, and other areas of scholarship that will best serve the nation and the world in the 21st century” (per MIT’s mission statement). At such a selective school, grades and test scores alone won’t set you apart–aligning your values with theirs is critical, and this student does so in a natural, authentic way.

While this essay is well-written, there’s one major issue: the student doesn’t fully answer the prompt. As noted above, they focus primarily on the “dreams and aspirations” line, and while they do tell a compelling story, we don’t learn anything about their “ family, school, community, city, or town,” beyond a brief mention of a repair shop where they live.

Especially at highly selective schools like MIT, admissions officers choose their essay questions carefully, based on the information they feel they need to properly evaluate your candidacy. So, if you fail to answer part of a prompt, in a certain sense your application is incomplete. As you work towards the final draft of your essay, make sure you reread the prompt and confirm you’ve responded to it thoroughly.

In this essay, for example, the writer could have reworked the opening paragraph slightly, to include details about who they typically watch TV with, whether that’s their friends, siblings, parents, or someone else. They also could have gone into more detail about the repair shop, by describing what their boss was like, if they had any coworkers, and so on. These additions would make the student’s “world” come alive in a way it currently doesn’t.

Of course, fully responding to a prompt while staying under the word count can be hard, but this student actually has 31 extra words at their disposal. And even if they had to make cuts elsewhere, answering all parts of a prompt takes priority over including every single detail in your story.

Finally, on a linguistic level, the ending of this essay is quite abrupt. In a relatively short supplement like this, you don’t need (or even want) a lengthy conclusion, but you should have a quick line or phrase to wrap up the story.

For example, say the last line read something like “ Today, if I’m not repairing people’s electronics, I’m amazed by integrating broken gadgets, and dreaming of all the fixes I have yet to learn.” With just a few extra words, this version not only brings things full circle by connecting back to the prompt, but also subtly builds a bridge between the student’s current passions and their potential future at MIT.

Prompt: MIT brings people with diverse backgrounds and experiences together to better the lives of others. Our students work to improve their communities in different ways, from tackling the world’s biggest challenges to being good friends. Describe one way you have collaborated with people who are different from you to contribute to your community. (225 words)

Embarking in a new environment can be challenging, but when everyone is new, it can be disastrous. After completing grade 9, every Rwandan student is transferred to a new school to pursue advanced secondary schooling. When I transferred to a new school, people only talked to those who had previously attended the same school, resulting in fierce competition and people being unable to interact together.

In an effort to solve this problem, I brainstormed ways to bring the entire class together, and “The caremate game” came to mind. I assigned each student a caretaker, another student with whom they were unfamiliar, and required them to look after him / her for the entire week, which included telling stories, buying snacks in the canteen, jogging together, and so on. However, because some people would not accept this game in the first place, I spoke to the tastemakers in the class before introducing it so that they could persuade others.

Everything went as planned; some students who couldn’t even interact before ended up in relationships. Everyone wanted to play it again, and we ended up doing so three times. Today, we are no longer divided; rather, we are a family of brothers and sisters.

In this essay, which is responding to a creative take on the classic “Community” prompt, the student does a great job of showcasing several qualities that MIT prizes in its students: problem-solving, imagination, and empathy, as well as an ability to make a difference in their everyday life.

We also want to highlight that the same student actually wrote both this essay and Example #4. We point this out because these two essays work in tandem, to present the student as simultaneously inventive and altruistic, even in quite ordinary situations. This picture would not be as clear if the student has chosen to highlight one set of qualities in Example #4, and a different set here.

Because college applications are inherently limiting in how much information they allow you to share about yourself–nobody can pack their entire personality into a transcript, an activities list, a 650-word personal statement, and a handful of supplements–some students are tempted to pack as much about themselves into their supplements as possible. However, that approach typically ends up being counterproductive.

Of course, we are all multifaceted, but if you choose to present yourself in three different ways in three different essays, MIT admissions officers may be unclear on who exactly they’d be admitting to their school. Remember, they’re trying to determine not just how well you’d do at MIT yourself, but also how you’d fit into the broader freshman class they’re assembling.

For example, if you were to talk about your love of fixing electronics above and then, say, your Taylor Swift fandom here, admissions officers may have a hard time determining how those two pieces of your personality fit together. After all, they have no additional background context on you, and they also have no choice but to read applications quickly, because they have so many to get through.

So, while having different, seemingly conflicting sides to your personality is part of being human, in the context of college applications specifically your goal should be to emphasize the same points in each essay, like this student. Cohesive applications are more memorable to admissions officers, as they clearly and directly show what that student has to offer that nobody else in the applicant pool does.

Just like there is some overlap between the strengths of this student’s essays, this essay’s biggest fault is a disconnect with the prompt, which asks applicants to “Describe one way you have collaborated with people who are different from you to contribute to your community.”

Remember, MIT admissions officers choose their prompts carefully. Including the bolded line, rather than having the prompt be just “Describe one way you have contributed to your community” means they want to see collaboration highlighted in your response.

While this student briefly mentions speaking “ to the tastemakers in the class before introducing it so that they could persuade others,” this is the only mention of collaboration in the essay, and we get no detail about what their conversations with these other students looked like, or the specific actions the other students took to ensure the success of the project. When a topic features so prominently in the prompt, you want to make sure you give it more than a passing glance in your response.

We also don’t get any explanation of what made these students different from the author. We can infer that they didn’t go to the same school before, but you never want to leave a key detail up to inference, as it’s always possible your reader doesn’t read you the way you intend.

Additionally, going to a different school doesn’t tell us what made these students different on a deeper level. MIT wants to see that you’re prepared to thrive at a school with students from all corners of the world, some of whom will have drastically different life experiences from you. Because we don’t know what made this student different from their peers in terms of personality, background, etc., nor how they worked across that difference, we can’t envision how they’d navigate MIT’s diverse student body.

Overall, the takeaway here is that choosing a topic for a college essay is a two-fold process. First, you need to have a strong story, which this student does. But secondly, and just as importantly, you want to cater the details of that story to the specific prompt you’re responding to, so that admissions officers will have all the information they need to make a well-informed decision about your candidacy.

Prompt: At MIT, we bring people together to better the lives of others. MIT students work to improve their communities in different ways, from tackling the world’s biggest challenges to being a good friend. Describe one way in which you have contributed to your community, whether in your family, the classroom, your neighborhood, etc. (200-250 words)

“Orange throw!”

As I extended my arm to signal properly, the smallest girl on the orange team picked up the ball to throw it back into play. In AYSO, U10 players often lift their back foot when throwing the ball, so I focused my attention there.

Don’t lift it. Keep it down.

It shot straight up.

My instincts blew the whistle to stop the game. The rulebook is simple: the rule was broken, give it to the other team. But the way she tried, eager to play, eager to learn and try again— I couldn’t punish that. So I made my way over to the sideline to try it myself.

“When we’re throwing it in, we wanna keep our back foot down. Try again!” After demonstrating, I backpedaled a bit and watched her throw again.

Don’t lift it. Keep it down… Ah, it stayed down.

“Nice throw!”

And just like that, we were off again. These short, educational encounters happen multiple times a game. And while they may not be prescribed, they provide so many learning opportunities. These kids, they’re the future of soccer. If they learn the basics, they can achieve greatness.

Every time I step out onto the pitch, that’s what I see: potential. Little Alex may not throw correctly now, but with work, she could become the next Alex Morgan. That’s why, in every soccer game I referee, every new situation I’m thrust into, I strive to see what’s more; I strive to see the potential.

There is so much imagery in this essay! It’s easy to see the scene in your mind. Through details such as “smallest girl” and describing the team as the “orange,” the reader can more easily picture the scene in their mind. Giving color, size, and other details such as these can make the imagery stronger and the picture clearer in the reader’s mind.

The writer narrates their thought process through their use of italics, bringing the reader into the mind of the writer. The space for each line of dialogue separates each thought, so that the reader can feel the full emphasis of each line. The mingling of cognitive narration and details about the setting keep the momentum of the essay.

Through this essay, we learn that this referee is supportive to the members of the youth soccer teams that they are refereeing; instead of seeing the role of referee as punitive (punishing), this writer sees it as a coaching experience. This idea of creating educational encounters as one’s contribution to the community is definitely a great idea to build upon for this essay prompt.

The contribution to the community is clear because of the emphasis on the coaching aspect of refereeing. However, especially thinking about structure, the author spends about half the essay on a single situation. Limiting this story to a third of the essay could give the writer more space to provide examples of other ways that the author has coached others. The author could have also connected this coaching experience to a mentoring experience in a different context, such as mentoring students at the YMCA, to create more connections between other extracurriculars and give more weight to this author’s contributions to the community.

The second to last paragraph ( “And just like that, we were off again…” ) could benefit from another example or two about showing, not telling. The sentence “And while they might not be prescribed, they provide so many learning opportunities” is already clear from the situation that the author has given; the author has already called these “educational encounters” in the prior sentence. Instead of that sentence, the writer could have given another example about a child thanking the writer for a coaching tip, or the expression on a different player’s face when they learned a new skill.

Additionally, the role of the writer is not immediately clear at the beginning, although it’s suspected that this student is most likely the referee. The writer also provides details about “AYSO” (American Youth Soccer Organization) and “U10,” where they could have simply referred to the games as “youth soccer games” to get the point across that the players are still learning basic skills about throwing the ball in.

To make all of this clear, the writer could have said “As a referee for youth soccer games, I have seen that players often lift their back foot when throwing the ball, so I focused my attention there.” Acronyms are usually best to be avoided in essays- they can take the reader’s attention away from what is actually happening and lead them to wonder about what the letters in the acronym stand for.

Where to Get Feedback on Your MIT Essay

Do you want feedback on your MIT essays? After rereading your essays countless times, it can be difficult to evaluate your writing objectively. That’s why we created our free Peer Essay Review tool , where you can get a free review of your essay from another student. You can also improve your own writing skills by reviewing other students’ essays.

If you want a college admissions expert to review your essay, advisors on CollegeVine have helped students refine their writing and submit successful applications to top schools. Find the right advisor for you to improve your chances of getting into your dream school!

Related CollegeVine Blog Posts

- Study Notes

- College Essays

MIT Admissions Essays

- Unlock All Essays

- What You Do For Fun

We know you lead a busy life, full of activities, many of which are required of you. Tell us about something you do simply for the pleasure of it.

I love listening to hard rock and heavy metal music. I find these music genres liberating because they pump me up and help me release stress. I enjoy doing this so much that I am an expert at games such as Guitar Hero and Rock Band, which I play with friends or alone just for the pleasure of it. Music allows me to entertain myself when I have to do things I do not like to do. Between rock music and reading a good book I can spend a full afternoon or evening perfectly content.

Essays That Worked

Read the top 146 college essays that worked at MIT and more. Learn more.

Keep reading more MIT admissions essays — you can't be too prepared!

Previous Essay Next Essay

Tip: Use the ← → keys to navigate!

How to cite this essay (MLA)

Victor G Negron

Mathematics, graduated mit '15, more mit essays.

- MIT Short Essays

- Major of Choice

- 106,519 views (29 views per day)

- Posted 10 years ago

46 Essays that Worked at MIT

Updated for the 2024-2025 admissions cycle.

.css-1l736oi{display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;gap:var(--chakra-space-4);font-family:var(--chakra-fonts-heading);} .css-1dkm51f{border-radius:var(--chakra-radii-full);border:1px solid black;} .css-1wp7s2d{margin:var(--chakra-space-3);position:relative;width:1em;height:1em;} .css-cfkose{display:inline;width:1em;height:1em;} About MIT .css-17xejub{-webkit-flex:1;-ms-flex:1;flex:1;justify-self:stretch;-webkit-align-self:stretch;-ms-flex-item-align:stretch;align-self:stretch;}

The Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) is a world-renowned research university based in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Known for its prioritization of intellectual freedom and innovation, MIT offers students an education that’s constantly on the cutting-edge of academia. The school’s star-studded roster of professors includes Nobel prize winners and MacArthur fellows in disciplines like technology, biology, and social science. A deeply-technical school, MIT offers students with the resources they need to become specialists in a range of STEM subjects. In many ways, MIT is the gold standard for creativity, critical thinking, and problem solving.

Unique traditions at MIT

1. "Ring Knocking": During the weeks preceding the MIT Commencement Ceremony, graduating students celebrate by finding a way to touch the MIT seal in the lobby of Building 10 with their newly-received class rings. 2. "Steer Roast": Every year in May, the MIT Science Fiction Society hosts a traditional event on the Killian Court lawn for incoming freshmen. During the Steer Roast, attendees cook (and sometimes eat) a sacrificial male cow and hang out outside until the early hours of the morning. 3. Pranking: Pranking has been an ongoing tradition at MIT since the 1960s. Creative pranks by student groups, ranging from changing the words of a university song to painting the Great Dome of the school, add to the quirkiness and wit of the MIT culture. 4. Senior House Seals: The all-senior undergraduate dormitory of Senior House is known for its yearly tradition of collecting and displaying seals, which are emblems that represent the class of the graduating seniors.

Programs at MIT

1. Global Entrepreneurship Lab (G-Lab): G-Lab provides undergraduate and graduate students with the skills to build entrepreneurial ventures that meet developing world challenges. 2. Mars Rover Design Team: This club is part of the MIT Student Robotics program that provides students with the engineering, design, and fabrication skills to build robots for planetary exploration. 3. Media Lab: The Media Lab is an interdisciplinary research lab that explores new technologies to allow individuals to create and manipulate communication presentation of stories, images, and sounds. 4. Independent Activities Period (IAP): A month-long intersession program that allows students to take courses and participate in extracurricular activities from flying classes to volunteering projects and sports. 5. AeroAstro: A club that provides students with the opportunity to learn about aerospace engineering and build model rockets.

At a glance…

Acceptance Rate

Average Cost

Average SAT

Average ACT

Cambridge, MA

Real Essays from MIT Admits

Prompt: mit brings people with diverse backgrounds and experiences together to better the lives of others. our students work to improve their communities in different ways, from tackling the world’s biggest challenges to being a good friend. describe one way you have collaborated with people who are different from you to contribute to your community..

Last year, my European History teacher asked me to host weekly workshops for AP test preparation and credit recovery opportunities: David, Michelangelo 1504. “*Why* is this the answer?” my tutee asked. I tried re-explaining the Renaissance. Michelangelo? The Papacy? I finally asked: “Do you know the story of David and Goliath?” Raised Catholic, I knew the story but her family was Hindu. I naively hadn’t considered she wouldn’t know the story. After I explained, she relayed a similar story from her culture. As sessions grew to upwards of 15 students, I recruited more tutors so everyone could receive more individualized support. While my school is nearly half Hispanic, AP classes are overwhelmingly White and Asian, so I’ve learned to understand the diverse and often unfamiliar backgrounds of my tutees. One student struggled to write idiomatically despite possessing extensive historical knowledge. Although she was initially nervous, we discovered common ground after I asked about her Rohan Kishibe keychain, a character from Jojo’s Bizarre Adventure. She opened up; I learned she recently immigrated from China and was having difficulty adjusting to writing in English. With a clearer understanding of her background, I could now consider her situation to better address her needs. Together, we combed out grammar mistakes and studied English syntax. The bond we formed over anime facilitated honest dialogue, and therefore genuine learning.

Essay by Víctor

i love cities <3

Prompt: We know you lead a busy life, full of activities, many of which are required of you. Tell us about something you do simply for the pleasure of it.

I slam the ball onto the concrete of our dorm’s courtyard, and it whizzes past my opponents. ******, which is a mashup of tennis, squash, and volleyball, is not only a spring term pastime but also an important dorm tradition. It can only be played using the eccentric layout of our dorm’s architecture and thus cultivates a special feeling of community that transcends grade or friend groups. I will always remember the amazing outplays from yearly tournaments that we celebrate together. Our dorm’s collective GPA may go significantly down during the spring, but it’s worth it.

Essay by Brian

CS, math, and economics at MIT

Prompt: Describe the world you come from (for example, your family, school, community, city, or town). How has that world shaped your dreams and aspirations?

The fragile glass beaker shattered on the ground, and hydrogen peroxide, flowing furiously like lava, began to conquer the floor with every inch the flammable puddle expanded. This was my solace. As an assistant teacher for a middle school STEM class on the weekends, mistakes were common, especially those that made me mentally pinpoint where we kept the fire extinguishers. However, these mishaps reminded me exactly why I loved this job (besides the obvious luxury of cleaning up spills): every failure was a chance to learn in the purest form. As we conducted chemical experiments or explored electronics kits, I was comforted by the kids’ genuine enthusiasm for exploration—a sentiment often lost in the grade-obsessed world of high school. Accordingly, I tried to help my students recognize that mistakes are often the most productive way to grow and learn. I encouraged my students to persist when faced with failure, especially those who might not have been encouraged in their everyday lives. I was there for students like Nathan, a child on the autism spectrum who reminded me of my older brother with autism. I was there for the two girls in a class of 17, reminding me of my own journey navigating the male-dominated world of STEM. I wanted to encourage them into a lifelong journey of pursuing knowledge and embracing mistakes. I may have been their mentor, but these lessons also serve as a crucial reminder to me that mistakes are not representative of one’s overall worth.

Essay by Sarah J.

cs @ stanford!! lover of STEM, taylor swift, and dogs!

.css-310tx6{display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;-webkit-box-pack:center;-ms-flex-pack:center;-webkit-justify-content:center;justify-content:center;text-align:center;gap:var(--chakra-space-4);} Find an essay from your twin at MIT .css-1dkm51f{border-radius:var(--chakra-radii-full);border:1px solid black;} .css-1wp7s2d{margin:var(--chakra-space-3);position:relative;width:1em;height:1em;} .css-cfkose{display:inline;width:1em;height:1em;}

Someone with the same interests, stats, and background as you

MIT Essays that Worked

Mit essays that worked – introduction.

In this guide, we’ll provide you with several MIT essays that worked. After each, we’ll discuss elements of these MIT essay examples in depth. By reading these sample MIT essays and our expert analysis, you’ll be better prepared to write your own MIT essay. Before you apply to MIT, read on for six MIT essays that worked.

Massachusetts Institute of Technology

The Massachusetts Institute of Technology is a private research university in Cambridge , Massachusetts. Since its founding in 1861, MIT has become one of the world’s foremost institutions for science and technology . With MIT ranking highly year after year, the low MIT acceptance rate is no surprise. Knowing how to get into MIT means knowing about MIT admissions, the MIT application, and how to write MIT supplemental essays.

MIT Supplemental Essay Requirements

The MIT application for 2022–2023 requires four short essays. Each essay should be up to 200 words in length.

MIT essay prompts :

We know you lead a busy life, full of activities, many of which are required of you. tell us about something you do simply for the pleasure of it., describe the world you come from (for example, your family, school, community, city, or town). how has that world shaped your dreams and aspirations.

- MIT brings people with diverse backgrounds and experiences together to better the lives of others. Our students work to improve their communities in different ways, from tackling the world’s biggest challenges to being a good friend. Describe one way you have collaborated with people who are different from you to contribute to your community.

- Tell us about a significant challenge you’ve faced (that you feel comfortable sharing) or something that didn’t go according to plan. How did you manage the situation?

MIT changes the wording of these prompts a little bit every year. As a result, our MIT essay examples may look a little different from the prompts to which you will be crafting your own responses. However, there is a lot of overlap between current and past prompts and often the underlying questions are the same. In other words, even if the prompts differ, most of our MIT essays that worked are still helpful. Even MIT essay examples for prompts that are gone can be useful as a general sample college essay.

As one of the best universities worldwide, MIT is nearly impossible to get into without a good strategy . Even if you don’t have a stellar ACT or SAT score , your essays may impress admissions officers. Let’s briefly analyze each prompt so we know what to look for in MIT essays that worked.

MIT Essay Prompt Breakdown

1. extracurricular essay.

First, you’ll write about an activity you enjoy, whether it’s baking, doing magic tricks, or writing fanfiction. Remember, strong MIT essay examples for this prompt show genuine enthusiasm and explain why the activity is meaningful. Choose a hobby you can write about with gusto while also showing what it means to you.

2. Your Background Essay

Next, we have a prompt asking about your background. This is a classic question; in every other sample college essay, you find answers to this prompt. This question is intentionally open-ended, allowing you to write about any aspect of your background you’d like. In the MIT essays that worked, the “world” has something important to say about the author’s values or outlook.

3. Community Essay

Then, the third essay asks how you work with diverse groups to contribute to a larger community. MIT wants to see that you can work toward community goals while valuing diverse perspectives. But don’t worry. They don’t expect you to have solved world hunger—pick something that demonstrates what community means to you.

4. Significant Challenge Essay

Lastly, we have the failure essay, which seeks to answer how you persist in the face of adversity. Notice the prompt doesn’t mention “overcoming,” so this can be a time that you completely flat-out failed. Everyone handles setbacks differently, so effective MIT essay examples illustrate the author’s unique way of managing failure. It doesn’t have to be a particularly unique or unusual failure, although that may help you stand out .

How to Apply to MIT

MIT doesn’t accept the Common or Coalition Application. Instead, there’s a school-specific application for all prospective students. The 2022 Early Action MIT application deadline was November 1. The Regular Action MIT application deadline is usually January 1, but it’s been extended this year to January 5, 2023. The financial aid information deadline is February 15, 2023.

Depending on your admissions round, you need to submit all materials to the Apply MIT portal by the specified deadline.

MIT application requirements

- Basic biographical information, including your intended area of study

- Four supplemental essays

- A brief list of four extracurricular activities that are meaningful to you

- Self-reported coursework information

- A Secondary School Report from your guidance counselor, including your transcript

- Two letters of recommendation : MIT recommends one from a STEM teacher and one from a humanities teacher.

- SAT or ACT scores —MIT is not test-optional for 2022–2023!

- The February Updates form with your midyear grades (goes live in mid-February)

Furthermore, interviews are offered to many—but not all—students; not being offered an interview doesn’t negatively reflect on your application. At the end of this article, we compile more resources regarding the rest of the application. If you have specific questions about your application, reach out to the MIT admissions office .

Now that we’ve discussed the prompts and MIT admissions process, let’s read some MIT essays that worked. We have six sample MIT essays to help you learn how to write MIT supplemental essays. And, if you’re looking to test your knowledge of college admissions, take our quiz below!

MIT Essay Examples #1 – Cultural Background Essay

The first of our MIT essay examples responds to a prompt that isn’t exactly on this year’s list. Let’s take a look. The prompt for this MIT essay that worked is:

Please tell us more about your cultural background and identity in the space below (100 word limit). If you need more than 100 words, please use the Optional section on Part 2.

Although the wording isn’t identical to any of this year’s prompts, it is similar to prompt #2. Remember, essay prompt #2 asks about the world you come from, which is essentially your background. However, MIT essay examples for this prompt speak more specifically about cultural background. With a shorter word limit, concise language is even more critical in MIT essays that worked for this prompt.

MIT Essays That Worked #1

My dad is black and my mom is white. But I am a shade of brown somewhere in between. I could never wear my mom’s makeup like other girls. By ten, I was tired seeing confused stares whenever I was with my dad. I became frustrated and confused. I talked to my biracial friends about becoming confident in my divergent ancestral roots. I found having both an understanding of black issues in America and of the middle class’ lack of exposure gave me greater clarity in many social issues. My background enabled me to become a compassionate, understanding biracial woman.

Why This Essay Worked

MIT essays that worked effectively show that the author can think about the bigger picture. This author describes their experiences as a biracial woman while addressing the wider scope of racial issues. While you shouldn’t reach to reference irrelevant societal problems, MIT essays that worked do often incorporate big ideas.

In addition, this author mentions conversations with biracial friends. MIT essay examples often include collaboration and community, and this one is no different. Often, sample MIT essays about cultural background will connect that heritage with one’s community. It shows that you value what makes you unique and can find it in others.

Lastly, strong MIT essay examples display reflection and personal growth. Do you understand the ways your experiences have shaped you, and can you write about them? Can you point to areas where you’ve grown as a result of your experiences? MIT essays that worked link the topic and the writer’s personal growth or values.

MIT Essays That Worked #2 – Activities Essay

The second of our MIT essay examples answers a prompt that’s on this year’s list.

In other words, write about a hobby or extracurricular activity—and what it says about you. As we mentioned above, MIT essays that worked for this prompt aren’t all about lofty ambitions. If you don’t read textbooks in your spare time, don’t write an essay claiming that’s your hobby. Be honest, thoughtful, and enthusiastic while finding a way to make your uniqueness show through. Let’s read one of many MIT essays that worked for this prompt.

MIT Essays That Worked #2

Adventuring. Surrounded by trees wider than I am tall on my right and the clear, blue lake on my left. I made it to the top after a strenuous hike and it was majestic. There is no feeling like the harmony I feel when immersing myself in nature on a hike or running through the mud to train for my sprint triathlon or even fighting for a pair of cute boots on black Friday. I take pleasure in each shade of adventure on my canvas of life, with each deliberate stroke leading me to new ideas, perspectives, and experiences.

MIT essays that worked use precise language to appeal to readers’ emotions. Note words like “strenuous,” “majestic,” “harmony,” and “deliberate.” The strategic use of vivid words like this can strengthen MIT essay examples and heighten their impact. But don’t overuse them—like paintings use a variety of shades, you should play with the intensity of your words.

Another benefit of colorful language is conveying meaning more deeply and precisely. Well-written MIT essay examples layer on meaning: this author likes adventuring through nature as well as life. With effective diction, you can make the most of the words you’re given. Consider using metaphors like in this MIT essay conclusion, comparing life to a canvas.

Now, think about your impression of the author after reading this. They’re active, ambitious, and, above all, adventurous. We know they like to challenge themselves (training for a triathlon) but also like fashion (buying cute boots). And we see from their concluding sentence that they have no intention of slowing down or pulling back. In under 100 words, we’ve got a clear snapshot of their worldview and see their adventuring spirit fits MIT.

MIT Essay Examples #3 – Why Major Essay

The third of our MIT essays that worked answers a prompt that isn’t on our list for 2022.

Although you may not yet know what you want to major in, which department or program at MIT appeals to you and why?

This is a classic “Why Major” essay, asked by hundreds of colleges every year. Obviously, the prompt asks about your academic interests . However, it subtly asks about school fit : why is MIT the best place for you to pursue this interest? Although this sample college essay prompt isn’t in this cycle, you should read as many sample MIT essays as possible. MIT essays that worked for the “Why Major” essay prompt illustrated the author’s academic interests and motivations. Let’s see what the next of our sample MIT essays has to say.

MIT Essays That Worked #3

My first step in to the Koch Institute for Integrative Cancer Research was magical. My eyes lit up like Christmas lights and my mind was racing faster than Usain Bolt. I was finally at home, in a community where my passions for biology, chemistry, math, and engineering collided, producing treatments to save lives everywhere.

I pictured myself in a tie-dyed lab coat, watching a tumor grow in a Petri disk then determining my treatment’s effectiveness. If I am admitted to MIT, I look forward to majoring in bioengineering and shaping and contributing to the forefront of bioengineering research.

Earlier, we said that MIT essays that worked use vivid language to drive home their point. This sample college essay is no different. Describing their instantaneous reaction, the author pulls us into their headspace to share in their delight. Following that, they show us their vision for the future. Finally, they state directly how they’ll work toward that vision at MIT.

This author points out that bioengineering aligns with their interests across math and the sciences. There’s no rule saying you can’t be purely into math, but MIT strives to cultivate the world’s leading minds. Many MIT essays that worked present the author as a multifaceted person and intellectual. If you write a Why Major essay for a STEM field, it may be worth your while to take an interdisciplinary angle.

Among other parts of these MIT essays that worked in the author’s favor is the mention of an experience. Many model MIT essay examples directly reference the author’s life experiences to connect them with their interest. For instance, this author frames their essay with a visit to a cancer research institute. We don’t know if it’s a tour or an internship—the reason for their visit is less important than the impact.

MIT Essay Examples #4 – Community Essay

At this point, we’ve gone through half of our MIT essay examples. Moving on, we’ll read three MIT essays that worked for prompts (nearly) identical to this year’s. Next, we’ve got a prompt asking about community contributions.

At MIT, we bring people together to better the lives of others. MIT students work to improve their communities in different ways, from tackling the world’s biggest challenges to being a good friend. Describe one way in which you have contributed to your community, whether in your family, the classroom, your neighborhood, etc.

It’s very similar to this year’s third prompt, with one crucial difference. The current prompt asks for “one way you have collaborated with people who are different from you .” While past MIT essay examples for this prompt could have focused on individual efforts, now you should focus on group efforts. In particular, groups where “people who are different from you” also play key roles. This is intentionally open-ended, allowing for endless kinds of differences.

With that said, let’s continue with our MIT essay examples.

MIT Essays That Worked #4

“I’m going to Harvard,” my brother proclaimed to me. My jaw dropped. My little brother, the one who I taught to pee in the toilet, the one who played in the pool with me every day of the summer for 7 years, the one who threw me in the trash can 3 months ago, had finally realized the potential I have seen in him since he was a little kid. And I was thrilled.

He told me that after attending the Harvard basketball program, he knew that attending college was the perfect opportunity for him to continue playing the sport he loved as well as get a very good education. His end goal (this is where I almost cried) was to become an engineer at Nike. The best part, though, is that he asked me to help him achieve it.

I was astounded that he thought so highly of me that he trusted me to help him. That night, we began discussing various fields of engineering that he could pursue, as well as the internship opportunities that he classified as “so cool.” As soon as school started, I bought him a planner and taught him to keep his activities organized. I go over homework with him and my baby brother almost every night.

I love using my knowledge to contribute to my family with my knowledge. I am so proud of my brother and our progress. I cannot wait to see him grow as he works to achieve his dream.

Perhaps while reading the prompt, you thought all MIT essays that worked discussed setting up a food bank or working at a hospital. Not so! What really matters for this essay is the impact the community has on you. In sample MIT essays like this one, we see just how important the writer’s family is to them. If your family means the world to you, don’t shy away from writing about them!

On the other hand, while many sample MIT essays discuss family, the best ones remember to center the author. It may seem selfish, but in an applicant pool of over 30,000 , you must stand out. You have to beat that low MIT acceptance rate by putting your best foot forward. Notice how the author’s feelings and thoughts show through in their interactions and reactions. Even in recounting their past with their little brother, you see them as a caring, playful older sibling. They’re thoroughly proud of their brother, his ambitions, and the trust he’s placed in them.

MIT Essay Examples #5 – Describe Your World

The fifth of our MIT essay examples answers a prompt in circulation this year. Hooray!

This “world” is open-ended to allow writers to explore the communities and people that have shaped them. This essay calls for deep introspection; can you find a common thread connecting you to your “world”? Some MIT essays that worked discuss family traditions, other city identities, etc. Whatever you choose, it should reflect who you are now and who you want to become.

MIT Essays That Worked #5

I was standing on the top row of the choir risers with my fellow third graders. We were beside the fourth graders who were beside the fifth graders. My teacher struck the first chords of our favorite song and we sang together, in proud call and response “Ujima, let us work together. To make better our community. We can solve! Solve our problems with collective work and responsibility.”

Then the students playing African drums and the xylophones on the floor began the harmonious percussion section and we sang again with as much passion as nine-year-olds can muster. This was my world. As a child, my community was centered around my school. At my school we discovered that if you love something enough, and work hard enough for it, you can do great things for both yourself and others around you.

In the years since I left, I reflected back on the lessons I learned at school. I determined I wanted to focus on the things I love – mathematics, science, and helping others. I also want to harmonize my abilities with those of other people so that we can work together to make the world a better place. Today I aspire to work in integrative research as a bioengineer to address the pressing medical issues of today.

For those who don’t know, ujima is the Swahili word for collective work and responsibility. The most well-crafted MIT essay examples employ narrative devices like framing and theme to leave a lasting impression. This essay, for example, introduces ujima with the choir scene—which itself is collective work—then reflects on the general concept. In every sentence, this writer works with the idea of collaboration and the positive power of the collective.

Among sample MIT essays, this can be challenging if you haven’t thought critically about your past and present. This writer clearly values collective responsibility and sees their future through that lens. They speak directly to their interests and their aspirations of bioengineering. All in all, they show careful consideration of ideas that have influenced them and the direction they want to take.

MIT Essay Examples #6 – Significant Challenge

The last of our MIT essays that worked answers a prompt nearly identical to one from this year.

Tell us about the most significant challenge you’ve faced or something important that didn’t go according to plan. How did you manage the situation?

The only difference is that this year’s prompt indicates you should feel comfortable sharing what you write about. This seems obvious, but you may be surprised how many students dredge up traumatic experiences in sample college essays. The issue isn’t that these experiences are unpleasant to read; on the contrary, they may be painful to write about. Although many MIT sample essays are somewhat vulnerable, you don’t have to write about experiences you’d rather keep to yourself.

With that said, let’s read the last of our MIT essay examples.

*Please be advised that the following essay example contains discussions of anxiety and panic attacks.

Mit essays that worked #6.

Ten o’clock on Wednesday, April 2016. Ten o’clock and I was sobbing, heaving, and gasping for air. Ten o’clock and I felt like all my hard work, passion, and perseverance had amounted to nothing and I was not enough. It was ten o’clock on a Wednesday, but it all started in August of 2015. I moved cities in August 2015. I knew the adjustment would be hard, but I thought if I immersed myself in challenging activities and classes I loved, I would get through the year just fine.

I was wrong. With each passing month I experienced increased anxiety attacks, lack of satisfaction in any and every activity, and constant degradation of my personal happiness. By April, I was broken. Naked, bent over the toilet, sweating, shaking, choking on the tightening of my own throat, thinking “not enough, not enough, not enough.”

It was extremely challenging to pick myself up after such a hard fall. When I finally made it out of the bathroom, I crawled to my room and read “Still I Rise” by Maya Angelou. Her struggle encouraged me to rise to this challenge stronger than I had been before. I prioritized my own happiness and fulfillment, taking care of my body and mind.

I finally realized I did not have to do everything on my own, and began collaborating with my peers to finish the year strong and begin initiatives for the next year. I became a stronger, more confident woman than ever before.

Now, you may understand why this year’s wording includes “that you feel comfortable sharing.” While the author’s vivid description helps immerse us in the moment, a reader may hope they’re okay now. Again, you don’t need to strictly avoid traumatizing moments—but don’t feel obligated to share anything you don’t want to. In any case, the diction is indeed very precise and helps convey just how shaken the author was.

Furthermore, we see how the author dealt with this challenge: they were inspired by Maya Angelou. This ability to seek and find strength beyond yourself is crucial, especially in an ever more connected world. At the end of the essay, the writer notes how they’ve changed by working with others to accomplish goals. Their renewed confidence has made them even stronger and more willing to face challenges.

MIT Essay Examples – Key Takeaways

So after reading six sample MIT essays, what do you think? What are the takeaways from these MIT essays that worked? It goes without saying that you should read more sample MIT essays if you can. Additionally, when you draft your own MIT essays, take time to revise them and have other people read them.

MIT Essays that Worked Takeaways

1. discuss experiences.

The best MIT essay examples keep it real by talking about the author’s experiences. Can you think critically about how they have made you who you are? Find ways to address the prompt with your background and life experiences. You may also find sample MIT essays easier to write when they’re rooted in your reality.

2. Use precise language

Two hundred words are, in fact, not that much space. MIT essays that worked use every word to paint a vivid picture of the writer and their world. Mark Twain said it best: “The difference between the almost right word and the right word is … the difference between the lightning-bug and the lightning.” Choose your words carefully to refine your meaning and strengthen your impact.

3. Reflect on yourself

In college essays, it’s all about you and your personal narrative . So don’t miss any opportunity to introspect on your experiences, community, and personal growth. Demonstrate that you know yourself well enough to point to specific influences on your worldview. We all move through the world in different ways—why do you move the way you do?

4. Be genuine

You’ve heard this a thousand times, and we’ll say it again: be yourself . While you hear all about the typical MIT student and what MIT looks for , we’re all unique individuals. As, or even more, important than good scores or a huge activities list is an accurate representation of you . Write about extracurriculars and subjects and communities that are important to you—not what you think will sound impressive.

Additional MIT Resources from CollegeAdvisor

We have a wealth of resources on how to get into MIT here at CollegeAdvisor.com. We’ve got a comprehensive article on the MIT admissions process, from the MIT acceptance rate to deadlines.

MIT Admissions

Speaking of the acceptance rate, we take a closer look at that, too.

MIT Acceptance Rate

If you’re wondering about MIT tuition and costs, read our breakdown .

MIT Tuition & MIT Cost

Finally, we’ve got a guide covering application strategy from start to finish.

Strategizing Your MIT Application

MIT Essays that Worked – Final thoughts

Placing among the top American universities, we see MIT ranking highly every year, and for good reason. By the same token, it’s very challenging to get admitted. So, in order to get in, you need to know how to write MIT supplemental essays.

We read through several MIT essays that worked and identified strengths in our MIT essay examples. Use these tips when writing your own essays to craft a strong application!

This article was written by Gina Goosby . Looking for more admissions support? Click here to schedule a free meeting with one of our Admissions Specialists. During your meeting, our team will discuss your profile and help you find targeted ways to increase your admissions odds at top schools. We’ll also answer any questions and discuss how CollegeAdvisor.com can support you in the college application process.

Personalized and effective college advising for high school students.

- Advisor Application

- Popular Colleges

- Privacy Policy and Cookie Notice

- Student Login

- California Privacy Notice

- Terms and Conditions

- Your Privacy Choices

By using the College Advisor site and/or working with College Advisor, you agree to our updated Terms and Conditions and Privacy Policy , including an arbitration clause that covers any disputes relating to our policies and your use of our products and services.

MIT Technology Review

- Newsletters

What is AI?

Everyone thinks they know but no one can agree. And that’s a problem.

- Will Douglas Heaven archive page

Internet nastiness, name-calling, and other not-so-petty, world-altering disagreements

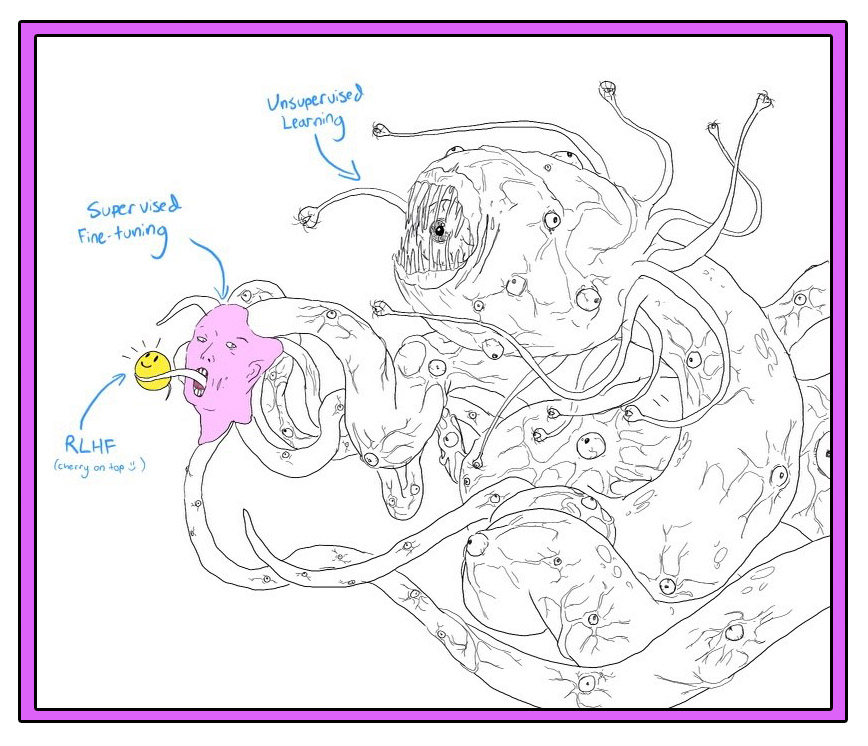

AI is sexy, AI is cool. AI is entrenching inequality, upending the job market, and wrecking education. AI is a theme-park ride, AI is a magic trick. AI is our final invention, AI is a moral obligation. AI is the buzzword of the decade, AI is marketing jargon from 1955. AI is humanlike, AI is alien. AI is super-smart and as dumb as dirt. The AI boom will boost the economy, the AI bubble is about to burst. AI will increase abundance and empower humanity to maximally flourish in the universe. AI will kill us all.

What the hell is everybody talking about?

Artificial intelligence is the hottest technology of our time. But what is it? It sounds like a stupid question, but it’s one that’s never been more urgent. Here’s the short answer: AI is a catchall term for a set of technologies that make computers do things that are thought to require intelligence when done by people. Think of recognizing faces, understanding speech, driving cars, writing sentences, answering questions, creating pictures. But even that definition contains multitudes.

And that right there is the problem. What does it mean for machines to understand speech or write a sentence? What kinds of tasks could we ask such machines to do? And how much should we trust the machines to do them?