- Privacy Policy

Home » Research Paper – Structure, Examples and Writing Guide

Research Paper – Structure, Examples and Writing Guide

Table of Contents

Research Paper

Definition:

Research Paper is a written document that presents the author’s original research, analysis, and interpretation of a specific topic or issue.

It is typically based on Empirical Evidence, and may involve qualitative or quantitative research methods, or a combination of both. The purpose of a research paper is to contribute new knowledge or insights to a particular field of study, and to demonstrate the author’s understanding of the existing literature and theories related to the topic.

Structure of Research Paper

The structure of a research paper typically follows a standard format, consisting of several sections that convey specific information about the research study. The following is a detailed explanation of the structure of a research paper:

The title page contains the title of the paper, the name(s) of the author(s), and the affiliation(s) of the author(s). It also includes the date of submission and possibly, the name of the journal or conference where the paper is to be published.

The abstract is a brief summary of the research paper, typically ranging from 100 to 250 words. It should include the research question, the methods used, the key findings, and the implications of the results. The abstract should be written in a concise and clear manner to allow readers to quickly grasp the essence of the research.

Introduction

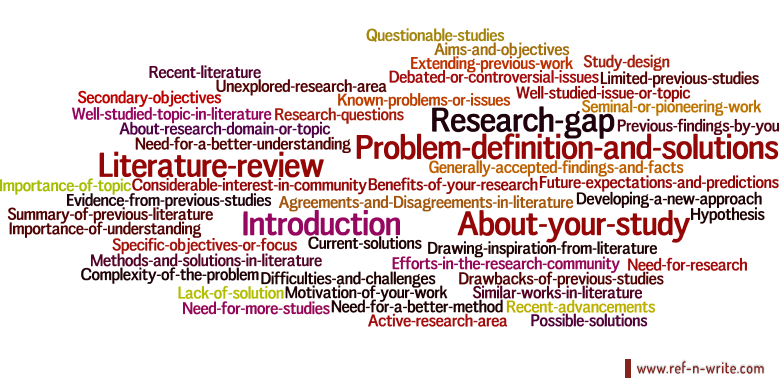

The introduction section of a research paper provides background information about the research problem, the research question, and the research objectives. It also outlines the significance of the research, the research gap that it aims to fill, and the approach taken to address the research question. Finally, the introduction section ends with a clear statement of the research hypothesis or research question.

Literature Review

The literature review section of a research paper provides an overview of the existing literature on the topic of study. It includes a critical analysis and synthesis of the literature, highlighting the key concepts, themes, and debates. The literature review should also demonstrate the research gap and how the current study seeks to address it.

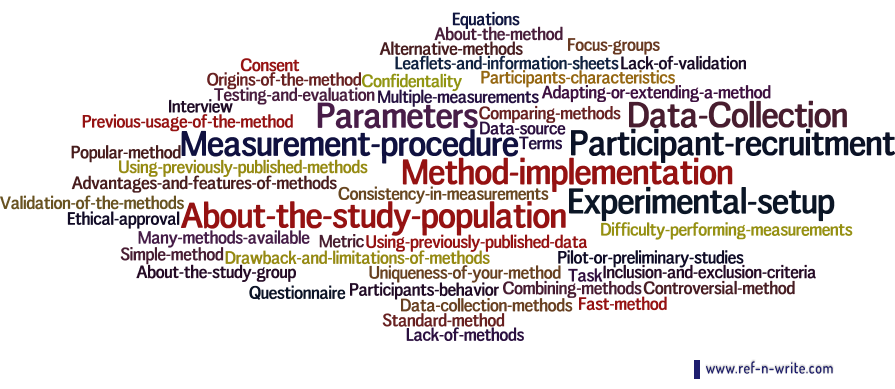

The methods section of a research paper describes the research design, the sample selection, the data collection and analysis procedures, and the statistical methods used to analyze the data. This section should provide sufficient detail for other researchers to replicate the study.

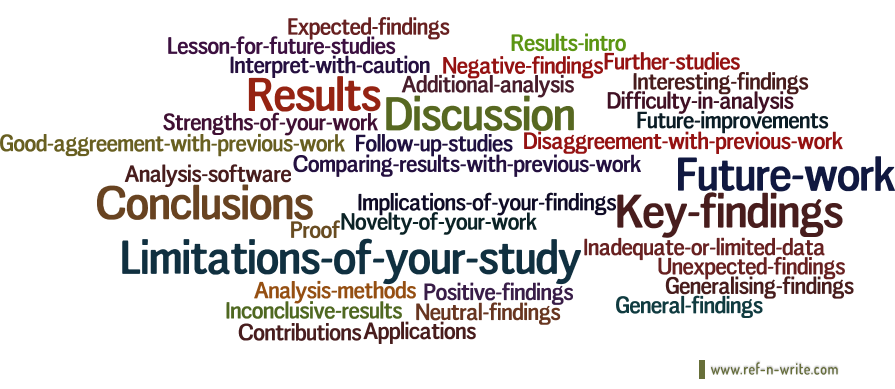

The results section presents the findings of the research, using tables, graphs, and figures to illustrate the data. The findings should be presented in a clear and concise manner, with reference to the research question and hypothesis.

The discussion section of a research paper interprets the findings and discusses their implications for the research question, the literature review, and the field of study. It should also address the limitations of the study and suggest future research directions.

The conclusion section summarizes the main findings of the study, restates the research question and hypothesis, and provides a final reflection on the significance of the research.

The references section provides a list of all the sources cited in the paper, following a specific citation style such as APA, MLA or Chicago.

How to Write Research Paper

You can write Research Paper by the following guide:

- Choose a Topic: The first step is to select a topic that interests you and is relevant to your field of study. Brainstorm ideas and narrow down to a research question that is specific and researchable.

- Conduct a Literature Review: The literature review helps you identify the gap in the existing research and provides a basis for your research question. It also helps you to develop a theoretical framework and research hypothesis.

- Develop a Thesis Statement : The thesis statement is the main argument of your research paper. It should be clear, concise and specific to your research question.

- Plan your Research: Develop a research plan that outlines the methods, data sources, and data analysis procedures. This will help you to collect and analyze data effectively.

- Collect and Analyze Data: Collect data using various methods such as surveys, interviews, observations, or experiments. Analyze data using statistical tools or other qualitative methods.

- Organize your Paper : Organize your paper into sections such as Introduction, Literature Review, Methods, Results, Discussion, and Conclusion. Ensure that each section is coherent and follows a logical flow.

- Write your Paper : Start by writing the introduction, followed by the literature review, methods, results, discussion, and conclusion. Ensure that your writing is clear, concise, and follows the required formatting and citation styles.

- Edit and Proofread your Paper: Review your paper for grammar and spelling errors, and ensure that it is well-structured and easy to read. Ask someone else to review your paper to get feedback and suggestions for improvement.

- Cite your Sources: Ensure that you properly cite all sources used in your research paper. This is essential for giving credit to the original authors and avoiding plagiarism.

Research Paper Example

Note : The below example research paper is for illustrative purposes only and is not an actual research paper. Actual research papers may have different structures, contents, and formats depending on the field of study, research question, data collection and analysis methods, and other factors. Students should always consult with their professors or supervisors for specific guidelines and expectations for their research papers.

Research Paper Example sample for Students:

Title: The Impact of Social Media on Mental Health among Young Adults

Abstract: This study aims to investigate the impact of social media use on the mental health of young adults. A literature review was conducted to examine the existing research on the topic. A survey was then administered to 200 university students to collect data on their social media use, mental health status, and perceived impact of social media on their mental health. The results showed that social media use is positively associated with depression, anxiety, and stress. The study also found that social comparison, cyberbullying, and FOMO (Fear of Missing Out) are significant predictors of mental health problems among young adults.

Introduction: Social media has become an integral part of modern life, particularly among young adults. While social media has many benefits, including increased communication and social connectivity, it has also been associated with negative outcomes, such as addiction, cyberbullying, and mental health problems. This study aims to investigate the impact of social media use on the mental health of young adults.

Literature Review: The literature review highlights the existing research on the impact of social media use on mental health. The review shows that social media use is associated with depression, anxiety, stress, and other mental health problems. The review also identifies the factors that contribute to the negative impact of social media, including social comparison, cyberbullying, and FOMO.

Methods : A survey was administered to 200 university students to collect data on their social media use, mental health status, and perceived impact of social media on their mental health. The survey included questions on social media use, mental health status (measured using the DASS-21), and perceived impact of social media on their mental health. Data were analyzed using descriptive statistics and regression analysis.

Results : The results showed that social media use is positively associated with depression, anxiety, and stress. The study also found that social comparison, cyberbullying, and FOMO are significant predictors of mental health problems among young adults.

Discussion : The study’s findings suggest that social media use has a negative impact on the mental health of young adults. The study highlights the need for interventions that address the factors contributing to the negative impact of social media, such as social comparison, cyberbullying, and FOMO.

Conclusion : In conclusion, social media use has a significant impact on the mental health of young adults. The study’s findings underscore the need for interventions that promote healthy social media use and address the negative outcomes associated with social media use. Future research can explore the effectiveness of interventions aimed at reducing the negative impact of social media on mental health. Additionally, longitudinal studies can investigate the long-term effects of social media use on mental health.

Limitations : The study has some limitations, including the use of self-report measures and a cross-sectional design. The use of self-report measures may result in biased responses, and a cross-sectional design limits the ability to establish causality.

Implications: The study’s findings have implications for mental health professionals, educators, and policymakers. Mental health professionals can use the findings to develop interventions that address the negative impact of social media use on mental health. Educators can incorporate social media literacy into their curriculum to promote healthy social media use among young adults. Policymakers can use the findings to develop policies that protect young adults from the negative outcomes associated with social media use.

References :

- Twenge, J. M., & Campbell, W. K. (2019). Associations between screen time and lower psychological well-being among children and adolescents: Evidence from a population-based study. Preventive medicine reports, 15, 100918.

- Primack, B. A., Shensa, A., Escobar-Viera, C. G., Barrett, E. L., Sidani, J. E., Colditz, J. B., … & James, A. E. (2017). Use of multiple social media platforms and symptoms of depression and anxiety: A nationally-representative study among US young adults. Computers in Human Behavior, 69, 1-9.

- Van der Meer, T. G., & Verhoeven, J. W. (2017). Social media and its impact on academic performance of students. Journal of Information Technology Education: Research, 16, 383-398.

Appendix : The survey used in this study is provided below.

Social Media and Mental Health Survey

- How often do you use social media per day?

- Less than 30 minutes

- 30 minutes to 1 hour

- 1 to 2 hours

- 2 to 4 hours

- More than 4 hours

- Which social media platforms do you use?

- Others (Please specify)

- How often do you experience the following on social media?

- Social comparison (comparing yourself to others)

- Cyberbullying

- Fear of Missing Out (FOMO)

- Have you ever experienced any of the following mental health problems in the past month?

- Do you think social media use has a positive or negative impact on your mental health?

- Very positive

- Somewhat positive

- Somewhat negative

- Very negative

- In your opinion, which factors contribute to the negative impact of social media on mental health?

- Social comparison

- In your opinion, what interventions could be effective in reducing the negative impact of social media on mental health?

- Education on healthy social media use

- Counseling for mental health problems caused by social media

- Social media detox programs

- Regulation of social media use

Thank you for your participation!

Applications of Research Paper

Research papers have several applications in various fields, including:

- Advancing knowledge: Research papers contribute to the advancement of knowledge by generating new insights, theories, and findings that can inform future research and practice. They help to answer important questions, clarify existing knowledge, and identify areas that require further investigation.

- Informing policy: Research papers can inform policy decisions by providing evidence-based recommendations for policymakers. They can help to identify gaps in current policies, evaluate the effectiveness of interventions, and inform the development of new policies and regulations.

- Improving practice: Research papers can improve practice by providing evidence-based guidance for professionals in various fields, including medicine, education, business, and psychology. They can inform the development of best practices, guidelines, and standards of care that can improve outcomes for individuals and organizations.

- Educating students : Research papers are often used as teaching tools in universities and colleges to educate students about research methods, data analysis, and academic writing. They help students to develop critical thinking skills, research skills, and communication skills that are essential for success in many careers.

- Fostering collaboration: Research papers can foster collaboration among researchers, practitioners, and policymakers by providing a platform for sharing knowledge and ideas. They can facilitate interdisciplinary collaborations and partnerships that can lead to innovative solutions to complex problems.

When to Write Research Paper

Research papers are typically written when a person has completed a research project or when they have conducted a study and have obtained data or findings that they want to share with the academic or professional community. Research papers are usually written in academic settings, such as universities, but they can also be written in professional settings, such as research organizations, government agencies, or private companies.

Here are some common situations where a person might need to write a research paper:

- For academic purposes: Students in universities and colleges are often required to write research papers as part of their coursework, particularly in the social sciences, natural sciences, and humanities. Writing research papers helps students to develop research skills, critical thinking skills, and academic writing skills.

- For publication: Researchers often write research papers to publish their findings in academic journals or to present their work at academic conferences. Publishing research papers is an important way to disseminate research findings to the academic community and to establish oneself as an expert in a particular field.

- To inform policy or practice : Researchers may write research papers to inform policy decisions or to improve practice in various fields. Research findings can be used to inform the development of policies, guidelines, and best practices that can improve outcomes for individuals and organizations.

- To share new insights or ideas: Researchers may write research papers to share new insights or ideas with the academic or professional community. They may present new theories, propose new research methods, or challenge existing paradigms in their field.

Purpose of Research Paper

The purpose of a research paper is to present the results of a study or investigation in a clear, concise, and structured manner. Research papers are written to communicate new knowledge, ideas, or findings to a specific audience, such as researchers, scholars, practitioners, or policymakers. The primary purposes of a research paper are:

- To contribute to the body of knowledge : Research papers aim to add new knowledge or insights to a particular field or discipline. They do this by reporting the results of empirical studies, reviewing and synthesizing existing literature, proposing new theories, or providing new perspectives on a topic.

- To inform or persuade: Research papers are written to inform or persuade the reader about a particular issue, topic, or phenomenon. They present evidence and arguments to support their claims and seek to persuade the reader of the validity of their findings or recommendations.

- To advance the field: Research papers seek to advance the field or discipline by identifying gaps in knowledge, proposing new research questions or approaches, or challenging existing assumptions or paradigms. They aim to contribute to ongoing debates and discussions within a field and to stimulate further research and inquiry.

- To demonstrate research skills: Research papers demonstrate the author’s research skills, including their ability to design and conduct a study, collect and analyze data, and interpret and communicate findings. They also demonstrate the author’s ability to critically evaluate existing literature, synthesize information from multiple sources, and write in a clear and structured manner.

Characteristics of Research Paper

Research papers have several characteristics that distinguish them from other forms of academic or professional writing. Here are some common characteristics of research papers:

- Evidence-based: Research papers are based on empirical evidence, which is collected through rigorous research methods such as experiments, surveys, observations, or interviews. They rely on objective data and facts to support their claims and conclusions.

- Structured and organized: Research papers have a clear and logical structure, with sections such as introduction, literature review, methods, results, discussion, and conclusion. They are organized in a way that helps the reader to follow the argument and understand the findings.

- Formal and objective: Research papers are written in a formal and objective tone, with an emphasis on clarity, precision, and accuracy. They avoid subjective language or personal opinions and instead rely on objective data and analysis to support their arguments.

- Citations and references: Research papers include citations and references to acknowledge the sources of information and ideas used in the paper. They use a specific citation style, such as APA, MLA, or Chicago, to ensure consistency and accuracy.

- Peer-reviewed: Research papers are often peer-reviewed, which means they are evaluated by other experts in the field before they are published. Peer-review ensures that the research is of high quality, meets ethical standards, and contributes to the advancement of knowledge in the field.

- Objective and unbiased: Research papers strive to be objective and unbiased in their presentation of the findings. They avoid personal biases or preconceptions and instead rely on the data and analysis to draw conclusions.

Advantages of Research Paper

Research papers have many advantages, both for the individual researcher and for the broader academic and professional community. Here are some advantages of research papers:

- Contribution to knowledge: Research papers contribute to the body of knowledge in a particular field or discipline. They add new information, insights, and perspectives to existing literature and help advance the understanding of a particular phenomenon or issue.

- Opportunity for intellectual growth: Research papers provide an opportunity for intellectual growth for the researcher. They require critical thinking, problem-solving, and creativity, which can help develop the researcher’s skills and knowledge.

- Career advancement: Research papers can help advance the researcher’s career by demonstrating their expertise and contributions to the field. They can also lead to new research opportunities, collaborations, and funding.

- Academic recognition: Research papers can lead to academic recognition in the form of awards, grants, or invitations to speak at conferences or events. They can also contribute to the researcher’s reputation and standing in the field.

- Impact on policy and practice: Research papers can have a significant impact on policy and practice. They can inform policy decisions, guide practice, and lead to changes in laws, regulations, or procedures.

- Advancement of society: Research papers can contribute to the advancement of society by addressing important issues, identifying solutions to problems, and promoting social justice and equality.

Limitations of Research Paper

Research papers also have some limitations that should be considered when interpreting their findings or implications. Here are some common limitations of research papers:

- Limited generalizability: Research findings may not be generalizable to other populations, settings, or contexts. Studies often use specific samples or conditions that may not reflect the broader population or real-world situations.

- Potential for bias : Research papers may be biased due to factors such as sample selection, measurement errors, or researcher biases. It is important to evaluate the quality of the research design and methods used to ensure that the findings are valid and reliable.

- Ethical concerns: Research papers may raise ethical concerns, such as the use of vulnerable populations or invasive procedures. Researchers must adhere to ethical guidelines and obtain informed consent from participants to ensure that the research is conducted in a responsible and respectful manner.

- Limitations of methodology: Research papers may be limited by the methodology used to collect and analyze data. For example, certain research methods may not capture the complexity or nuance of a particular phenomenon, or may not be appropriate for certain research questions.

- Publication bias: Research papers may be subject to publication bias, where positive or significant findings are more likely to be published than negative or non-significant findings. This can skew the overall findings of a particular area of research.

- Time and resource constraints: Research papers may be limited by time and resource constraints, which can affect the quality and scope of the research. Researchers may not have access to certain data or resources, or may be unable to conduct long-term studies due to practical limitations.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Data Analysis – Process, Methods and Types

Research Paper Conclusion – Writing Guide and...

Research Topics – Ideas and Examples

Research Paper Abstract – Writing Guide and...

APA Table of Contents – Format and Example

Research Summary – Structure, Examples and...

- Search This Site All UCSD Sites Faculty/Staff Search Term

- Contact & Directions

- Climate Statement

- Cognitive Behavioral Neuroscience

- Cognitive Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Adjunct Faculty

- Non-Senate Instructors

- Researchers

- Psychology Grads

- Affiliated Grads

- New and Prospective Students

- Honors Program

- Experiential Learning

- Programs & Events

- Psi Chi / Psychology Club

- Prospective PhD Students

- Current PhD Students

- Area Brown Bags

- Colloquium Series

- Anderson Distinguished Lecture Series

- Speaker Videos

- Undergraduate Program

- Academic and Writing Resources

Writing Research Papers

- Research Paper Structure

Whether you are writing a B.S. Degree Research Paper or completing a research report for a Psychology course, it is highly likely that you will need to organize your research paper in accordance with American Psychological Association (APA) guidelines. Here we discuss the structure of research papers according to APA style.

Major Sections of a Research Paper in APA Style

A complete research paper in APA style that is reporting on experimental research will typically contain a Title page, Abstract, Introduction, Methods, Results, Discussion, and References sections. 1 Many will also contain Figures and Tables and some will have an Appendix or Appendices. These sections are detailed as follows (for a more in-depth guide, please refer to " How to Write a Research Paper in APA Style ”, a comprehensive guide developed by Prof. Emma Geller). 2

What is this paper called and who wrote it? – the first page of the paper; this includes the name of the paper, a “running head”, authors, and institutional affiliation of the authors. The institutional affiliation is usually listed in an Author Note that is placed towards the bottom of the title page. In some cases, the Author Note also contains an acknowledgment of any funding support and of any individuals that assisted with the research project.

One-paragraph summary of the entire study – typically no more than 250 words in length (and in many cases it is well shorter than that), the Abstract provides an overview of the study.

Introduction

What is the topic and why is it worth studying? – the first major section of text in the paper, the Introduction commonly describes the topic under investigation, summarizes or discusses relevant prior research (for related details, please see the Writing Literature Reviews section of this website), identifies unresolved issues that the current research will address, and provides an overview of the research that is to be described in greater detail in the sections to follow.

What did you do? – a section which details how the research was performed. It typically features a description of the participants/subjects that were involved, the study design, the materials that were used, and the study procedure. If there were multiple experiments, then each experiment may require a separate Methods section. A rule of thumb is that the Methods section should be sufficiently detailed for another researcher to duplicate your research.

What did you find? – a section which describes the data that was collected and the results of any statistical tests that were performed. It may also be prefaced by a description of the analysis procedure that was used. If there were multiple experiments, then each experiment may require a separate Results section.

What is the significance of your results? – the final major section of text in the paper. The Discussion commonly features a summary of the results that were obtained in the study, describes how those results address the topic under investigation and/or the issues that the research was designed to address, and may expand upon the implications of those findings. Limitations and directions for future research are also commonly addressed.

List of articles and any books cited – an alphabetized list of the sources that are cited in the paper (by last name of the first author of each source). Each reference should follow specific APA guidelines regarding author names, dates, article titles, journal titles, journal volume numbers, page numbers, book publishers, publisher locations, websites, and so on (for more information, please see the Citing References in APA Style page of this website).

Tables and Figures

Graphs and data (optional in some cases) – depending on the type of research being performed, there may be Tables and/or Figures (however, in some cases, there may be neither). In APA style, each Table and each Figure is placed on a separate page and all Tables and Figures are included after the References. Tables are included first, followed by Figures. However, for some journals and undergraduate research papers (such as the B.S. Research Paper or Honors Thesis), Tables and Figures may be embedded in the text (depending on the instructor’s or editor’s policies; for more details, see "Deviations from APA Style" below).

Supplementary information (optional) – in some cases, additional information that is not critical to understanding the research paper, such as a list of experiment stimuli, details of a secondary analysis, or programming code, is provided. This is often placed in an Appendix.

Variations of Research Papers in APA Style

Although the major sections described above are common to most research papers written in APA style, there are variations on that pattern. These variations include:

- Literature reviews – when a paper is reviewing prior published research and not presenting new empirical research itself (such as in a review article, and particularly a qualitative review), then the authors may forgo any Methods and Results sections. Instead, there is a different structure such as an Introduction section followed by sections for each of the different aspects of the body of research being reviewed, and then perhaps a Discussion section.

- Multi-experiment papers – when there are multiple experiments, it is common to follow the Introduction with an Experiment 1 section, itself containing Methods, Results, and Discussion subsections. Then there is an Experiment 2 section with a similar structure, an Experiment 3 section with a similar structure, and so on until all experiments are covered. Towards the end of the paper there is a General Discussion section followed by References. Additionally, in multi-experiment papers, it is common for the Results and Discussion subsections for individual experiments to be combined into single “Results and Discussion” sections.

Departures from APA Style

In some cases, official APA style might not be followed (however, be sure to check with your editor, instructor, or other sources before deviating from standards of the Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association). Such deviations may include:

- Placement of Tables and Figures – in some cases, to make reading through the paper easier, Tables and/or Figures are embedded in the text (for example, having a bar graph placed in the relevant Results section). The embedding of Tables and/or Figures in the text is one of the most common deviations from APA style (and is commonly allowed in B.S. Degree Research Papers and Honors Theses; however you should check with your instructor, supervisor, or editor first).

- Incomplete research – sometimes a B.S. Degree Research Paper in this department is written about research that is currently being planned or is in progress. In those circumstances, sometimes only an Introduction and Methods section, followed by References, is included (that is, in cases where the research itself has not formally begun). In other cases, preliminary results are presented and noted as such in the Results section (such as in cases where the study is underway but not complete), and the Discussion section includes caveats about the in-progress nature of the research. Again, you should check with your instructor, supervisor, or editor first.

- Class assignments – in some classes in this department, an assignment must be written in APA style but is not exactly a traditional research paper (for instance, a student asked to write about an article that they read, and to write that report in APA style). In that case, the structure of the paper might approximate the typical sections of a research paper in APA style, but not entirely. You should check with your instructor for further guidelines.

Workshops and Downloadable Resources

- For in-person discussion of the process of writing research papers, please consider attending this department’s “Writing Research Papers” workshop (for dates and times, please check the undergraduate workshops calendar).

Downloadable Resources

- How to Write APA Style Research Papers (a comprehensive guide) [ PDF ]

- Tips for Writing APA Style Research Papers (a brief summary) [ PDF ]

- Example APA Style Research Paper (for B.S. Degree – empirical research) [ PDF ]

- Example APA Style Research Paper (for B.S. Degree – literature review) [ PDF ]

Further Resources

How-To Videos

- Writing Research Paper Videos

APA Journal Article Reporting Guidelines

- Appelbaum, M., Cooper, H., Kline, R. B., Mayo-Wilson, E., Nezu, A. M., & Rao, S. M. (2018). Journal article reporting standards for quantitative research in psychology: The APA Publications and Communications Board task force report . American Psychologist , 73 (1), 3.

- Levitt, H. M., Bamberg, M., Creswell, J. W., Frost, D. M., Josselson, R., & Suárez-Orozco, C. (2018). Journal article reporting standards for qualitative primary, qualitative meta-analytic, and mixed methods research in psychology: The APA Publications and Communications Board task force report . American Psychologist , 73 (1), 26.

External Resources

- Formatting APA Style Papers in Microsoft Word

- How to Write an APA Style Research Paper from Hamilton University

- WikiHow Guide to Writing APA Research Papers

- Sample APA Formatted Paper with Comments

- Sample APA Formatted Paper

- Tips for Writing a Paper in APA Style

1 VandenBos, G. R. (Ed). (2010). Publication manual of the American Psychological Association (6th ed.) (pp. 41-60). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

2 geller, e. (2018). how to write an apa-style research report . [instructional materials]. , prepared by s. c. pan for ucsd psychology.

Back to top

- Formatting Research Papers

- Using Databases and Finding References

- What Types of References Are Appropriate?

- Evaluating References and Taking Notes

- Citing References

- Writing a Literature Review

- Writing Process and Revising

- Improving Scientific Writing

- Academic Integrity and Avoiding Plagiarism

- Writing Research Papers Videos

How to Write a Research Paper: Parts of the Paper

- Choosing Your Topic

- Citation & Style Guides This link opens in a new window

- Critical Thinking

- Evaluating Information

- Parts of the Paper

- Writing Tips from UNC-Chapel Hill

- Librarian Contact

Parts of the Research Paper Papers should have a beginning, a middle, and an end. Your introductory paragraph should grab the reader's attention, state your main idea, and indicate how you will support it. The body of the paper should expand on what you have stated in the introduction. Finally, the conclusion restates the paper's thesis and should explain what you have learned, giving a wrap up of your main ideas.

1. The Title The title should be specific and indicate the theme of the research and what ideas it addresses. Use keywords that help explain your paper's topic to the reader. Try to avoid abbreviations and jargon. Think about keywords that people would use to search for your paper and include them in your title.

2. The Abstract The abstract is used by readers to get a quick overview of your paper. Typically, they are about 200 words in length (120 words minimum to 250 words maximum). The abstract should introduce the topic and thesis, and should provide a general statement about what you have found in your research. The abstract allows you to mention each major aspect of your topic and helps readers decide whether they want to read the rest of the paper. Because it is a summary of the entire research paper, it is often written last.

3. The Introduction The introduction should be designed to attract the reader's attention and explain the focus of the research. You will introduce your overview of the topic, your main points of information, and why this subject is important. You can introduce the current understanding and background information about the topic. Toward the end of the introduction, you add your thesis statement, and explain how you will provide information to support your research questions. This provides the purpose and focus for the rest of the paper.

4. Thesis Statement Most papers will have a thesis statement or main idea and supporting facts/ideas/arguments. State your main idea (something of interest or something to be proven or argued for or against) as your thesis statement, and then provide your supporting facts and arguments. A thesis statement is a declarative sentence that asserts the position a paper will be taking. It also points toward the paper's development. This statement should be both specific and arguable. Generally, the thesis statement will be placed at the end of the first paragraph of your paper. The remainder of your paper will support this thesis.

Students often learn to write a thesis as a first step in the writing process, but often, after research, a writer's viewpoint may change. Therefore a thesis statement may be one of the final steps in writing.

Examples of Thesis Statements from Purdue OWL

5. The Literature Review The purpose of the literature review is to describe past important research and how it specifically relates to the research thesis. It should be a synthesis of the previous literature and the new idea being researched. The review should examine the major theories related to the topic to date and their contributors. It should include all relevant findings from credible sources, such as academic books and peer-reviewed journal articles. You will want to:

- Explain how the literature helps the researcher understand the topic.

- Try to show connections and any disparities between the literature.

- Identify new ways to interpret prior research.

- Reveal any gaps that exist in the literature.

More about writing a literature review. . .

6. The Discussion The purpose of the discussion is to interpret and describe what you have learned from your research. Make the reader understand why your topic is important. The discussion should always demonstrate what you have learned from your readings (and viewings) and how that learning has made the topic evolve, especially from the short description of main points in the introduction.Explain any new understanding or insights you have had after reading your articles and/or books. Paragraphs should use transitioning sentences to develop how one paragraph idea leads to the next. The discussion will always connect to the introduction, your thesis statement, and the literature you reviewed, but it does not simply repeat or rearrange the introduction. You want to:

- Demonstrate critical thinking, not just reporting back facts that you gathered.

- If possible, tell how the topic has evolved over the past and give it's implications for the future.

- Fully explain your main ideas with supporting information.

- Explain why your thesis is correct giving arguments to counter points.

7. The Conclusion A concluding paragraph is a brief summary of your main ideas and restates the paper's main thesis, giving the reader the sense that the stated goal of the paper has been accomplished. What have you learned by doing this research that you didn't know before? What conclusions have you drawn? You may also want to suggest further areas of study, improvement of research possibilities, etc. to demonstrate your critical thinking regarding your research.

- << Previous: Evaluating Information

- Next: Research >>

- Last Updated: Feb 13, 2024 8:35 AM

- URL: https://libguides.ucc.edu/research_paper

- Contact sales (+234) 08132546417

- Have a questions? [email protected]

- Latest Projects

Project Materials

How to write a good chapter two: literature review.

Click Here to Download Now.

Do You Have New or Fresh Topic? Send Us Your Topic

How to write chapter two of a research pape r.

As is known, within a research paper, there are several types of research and methodologies. One of the most common types used by students is the literature review. In this article, we will be dealing how to write the literature review (Chapter Two) of your research paper.

Although when writing a project, literature review (Chapter Two) seems more straightforward than carrying out experiments or field research, the literature review involves a lot of research and a lot of reading. Also, utmost attention is essential when it comes to developing and referencing the content so that nothing is pointed out as plagiarism.

However, unlike other steps in project writing, it is not necessary to perform the separate theoretical reference part in the review. After all, the work itself will be a theoretical reference, filled with relevant information and views of several authors on the same subject over time.

As it technically has fewer steps and does not need to go to the field or build appraisal projects, the research paper literature review is a great choice for those who have the tightest deadline for delivering the work. But make no mistake, the level of seriousness in research and development itself is as difficult as any other step.

To further facilitate your understanding, we have divided this research methodology into some essential steps and will explain how to do each of them clearly and objectively. Want to know more about it? Read on and check it out!

What is the literature review in a research paper?

To develop a project in any discipline, it is necessary, first, to study everything that other authors have already explored on that subject. This step aims to update the subject for the academic community and to have a basis to support new research. Therefore, it must be done before any other process within the research paper. However, in the literature review (Chapter Two), this step of searching for data and previous work is all the work. That is, you will only develop the theoretical framework.

In general, you will need to choose the topic in question and search for more relevant works and authors that worked around that research idea you want to discuss. As the intention is to make history and update the subject, you will be able to use works from different dates, showing how opinions and views have evolved over time.

Suppose the subject of your research paper is the role of monarchies in 21st-century societies, for example. In that case, you must present a history of how this institution came about, its impact on society, and what roles the institution is currently playing in modern societies. In the end, you can make a more personal conclusion about your vision.

If your topic covered contains a lot of content, you will need to select the most important and relevant and highlight them throughout the work. This is because you will need to reference the entire work. This means that the research paper literature review needs to be filled with citations from other authors. Therefore, it will present references in practically every paragraph.

In order not to make your work uninteresting and repetitive, you should quote differently throughout development. Switching between direct and indirect citations and trying to fit as much content and work as possible will enrich your project and demonstrate to the evaluators how deep you have been in the search.

Within the review, the only part that does not need to be referenced is the conclusion. After all, it will be written as your final and personal view of everything you have read and analyzed.

How to write a literature review?

Here are some practical and easy tips for structuring a quality and compliant research paper literature review!

Introduction

As with any work, the introduction should attract your project readers’ attention and help them understand the basis of the subject that will be worked on. When reading the introduction, you need to be clear to whoever is reading about your research and what it wants to show.

Following the example cited on the theme of monarchies’ roles in the 21st-century societies, the introduction needs to clarify what this type of institution is and why research on it is vital for this area. Also, it would help if you also quoted how the work was developed and the purpose of your literary study.

Basically, you will introduce the subject in such a way that the reader – even without knowing anything about the topic – can read the complete work and grasp the approach, understanding what was done and the meaning of it.

Methodology

Describing the methodology of a literature review is simpler than describing the steps of field research or experiment. In this step, you will need to describe how your research was carried out, where the information was searched, and retrieved.

As you will need to gather a lot of content, searches can be done in books, academic articles, academic publications, old monographs, internet articles, among other reliable sources. The important thing is always to be sure with your supervisor or other teachers about the reliability of each content used. After all, as the entire work is a theoretical reference, choosing unreliable base papers can greatly damage your grade and hinder your approval, putting at risk the quality and integrity of your entire research paper.

Results and conclusion

The results must present clearly and objectively everything that has been observed and collected from studies throughout history on the research’s theme. In this step, you should show the comparisons between authors, like what was the view of the subject before and how it is currently, in an updated way.

You will also be able to show the developments within the theme and the progress of research and discoveries, as well as the conclusions on the issue so far. In the end, you will summarize everything you have read and discovered, and present your final view on the topic.

Also, it is important to demonstrate whether your project objectives have been met and how. The conclusion is the crucial point to convince your reader and examiner of the relevance and importance of all the work you have done for your area or branch, society, or the environment. Therefore, you must present everything clearly and concisely, closing your research paper with a flourish.

In all academic work, bibliographic references are essential. In the academic paper literature review, however, these references will be gathered at the end of the work and throughout the texts.

Citations during the development of the subject must be referenced in accordance with the guideline of your institutions and departments. For each type of reference, there is a rule that depends on the number of words or how you will make it.

Also, in the list of bibliographic references, where you will need to put all the content used, the rules change according to your search source. For internet sources, for example, the way of referencing is different than book sources.

A wrong quote throughout the text or a used work that you forget to put in the references can lead to your project being labeled a plagiarism work, which is a crime and can lead to several consequences. Therefore, studying these standards is essential and determinant for the success of your work’s literature review (Chapter Two).

By adequately studying the rules, dedicating yourself, and putting them into practice, not only will it be easy to develop a successful project, but achieving your dream grade will be closer than you think.

Not What You Were Looking For? Send Us Your Topic

INSTRUCTIONS AFTER PAYMENT

- 1.Your Full name

- 2. Your Active Email Address

- 3. Your Phone Number

- 4. Amount Paid

- 5. Project Topic

- 6. Location you made payment from

» Send the above details to our email; [email protected] or to our support phone number; (+234) 0813 2546 417 . As soon as details are sent and payment is confirmed, your project will be delivered to you within minutes.

Latest Updates

Media gate keeping process as a catalyst for promoting good governance, influence of newspaper political report in voting behaviour, twitter handle of selected celebrities as a tool for mobilizing endsars protesters, leave a reply cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

Advertisements

- Hire A Writer

- Plagiarism Research Clinic

- International Students

- Project Categories

- WHY HIRE A PREMIUM RESEARCHER?

- UPGRADE PLAN

- PROFESSIONAL PLAN

- STANDARD PLAN

- MBA MSC STANDARD PLAN

- MBA MSC PROFESSIONAL PLAN

How To Write A Research Paper

Step-By-Step Tutorial With Examples + FREE Template

By: Derek Jansen (MBA) | Expert Reviewer: Dr Eunice Rautenbach | March 2024

For many students, crafting a strong research paper from scratch can feel like a daunting task – and rightly so! In this post, we’ll unpack what a research paper is, what it needs to do , and how to write one – in three easy steps. 🙂

Overview: Writing A Research Paper

What (exactly) is a research paper.

- How to write a research paper

- Stage 1 : Topic & literature search

- Stage 2 : Structure & outline

- Stage 3 : Iterative writing

- Key takeaways

Let’s start by asking the most important question, “ What is a research paper? ”.

Simply put, a research paper is a scholarly written work where the writer (that’s you!) answers a specific question (this is called a research question ) through evidence-based arguments . Evidence-based is the keyword here. In other words, a research paper is different from an essay or other writing assignments that draw from the writer’s personal opinions or experiences. With a research paper, it’s all about building your arguments based on evidence (we’ll talk more about that evidence a little later).

Now, it’s worth noting that there are many different types of research papers , including analytical papers (the type I just described), argumentative papers, and interpretative papers. Here, we’ll focus on analytical papers , as these are some of the most common – but if you’re keen to learn about other types of research papers, be sure to check out the rest of the blog .

With that basic foundation laid, let’s get down to business and look at how to write a research paper .

Overview: The 3-Stage Process

While there are, of course, many potential approaches you can take to write a research paper, there are typically three stages to the writing process. So, in this tutorial, we’ll present a straightforward three-step process that we use when working with students at Grad Coach.

These three steps are:

- Finding a research topic and reviewing the existing literature

- Developing a provisional structure and outline for your paper, and

- Writing up your initial draft and then refining it iteratively

Let’s dig into each of these.

Need a helping hand?

Step 1: Find a topic and review the literature

As we mentioned earlier, in a research paper, you, as the researcher, will try to answer a question . More specifically, that’s called a research question , and it sets the direction of your entire paper. What’s important to understand though is that you’ll need to answer that research question with the help of high-quality sources – for example, journal articles, government reports, case studies, and so on. We’ll circle back to this in a minute.

The first stage of the research process is deciding on what your research question will be and then reviewing the existing literature (in other words, past studies and papers) to see what they say about that specific research question. In some cases, your professor may provide you with a predetermined research question (or set of questions). However, in many cases, you’ll need to find your own research question within a certain topic area.

Finding a strong research question hinges on identifying a meaningful research gap – in other words, an area that’s lacking in existing research. There’s a lot to unpack here, so if you wanna learn more, check out the plain-language explainer video below.

Once you’ve figured out which question (or questions) you’ll attempt to answer in your research paper, you’ll need to do a deep dive into the existing literature – this is called a “ literature search ”. Again, there are many ways to go about this, but your most likely starting point will be Google Scholar .

If you’re new to Google Scholar, think of it as Google for the academic world. You can start by simply entering a few different keywords that are relevant to your research question and it will then present a host of articles for you to review. What you want to pay close attention to here is the number of citations for each paper – the more citations a paper has, the more credible it is (generally speaking – there are some exceptions, of course).

Ideally, what you’re looking for are well-cited papers that are highly relevant to your topic. That said, keep in mind that citations are a cumulative metric , so older papers will often have more citations than newer papers – just because they’ve been around for longer. So, don’t fixate on this metric in isolation – relevance and recency are also very important.

Beyond Google Scholar, you’ll also definitely want to check out academic databases and aggregators such as Science Direct, PubMed, JStor and so on. These will often overlap with the results that you find in Google Scholar, but they can also reveal some hidden gems – so, be sure to check them out.

Once you’ve worked your way through all the literature, you’ll want to catalogue all this information in some sort of spreadsheet so that you can easily recall who said what, when and within what context. If you’d like, we’ve got a free literature spreadsheet that helps you do exactly that.

Step 2: Develop a structure and outline

With your research question pinned down and your literature digested and catalogued, it’s time to move on to planning your actual research paper .

It might sound obvious, but it’s really important to have some sort of rough outline in place before you start writing your paper. So often, we see students eagerly rushing into the writing phase, only to land up with a disjointed research paper that rambles on in multiple

Now, the secret here is to not get caught up in the fine details . Realistically, all you need at this stage is a bullet-point list that describes (in broad strokes) what you’ll discuss and in what order. It’s also useful to remember that you’re not glued to this outline – in all likelihood, you’ll chop and change some sections once you start writing, and that’s perfectly okay. What’s important is that you have some sort of roadmap in place from the start.

At this stage you might be wondering, “ But how should I structure my research paper? ”. Well, there’s no one-size-fits-all solution here, but in general, a research paper will consist of a few relatively standardised components:

- Introduction

- Literature review

- Methodology

Let’s take a look at each of these.

First up is the introduction section . As the name suggests, the purpose of the introduction is to set the scene for your research paper. There are usually (at least) four ingredients that go into this section – these are the background to the topic, the research problem and resultant research question , and the justification or rationale. If you’re interested, the video below unpacks the introduction section in more detail.

The next section of your research paper will typically be your literature review . Remember all that literature you worked through earlier? Well, this is where you’ll present your interpretation of all that content . You’ll do this by writing about recent trends, developments, and arguments within the literature – but more specifically, those that are relevant to your research question . The literature review can oftentimes seem a little daunting, even to seasoned researchers, so be sure to check out our extensive collection of literature review content here .

With the introduction and lit review out of the way, the next section of your paper is the research methodology . In a nutshell, the methodology section should describe to your reader what you did (beyond just reviewing the existing literature) to answer your research question. For example, what data did you collect, how did you collect that data, how did you analyse that data and so on? For each choice, you’ll also need to justify why you chose to do it that way, and what the strengths and weaknesses of your approach were.

Now, it’s worth mentioning that for some research papers, this aspect of the project may be a lot simpler . For example, you may only need to draw on secondary sources (in other words, existing data sets). In some cases, you may just be asked to draw your conclusions from the literature search itself (in other words, there may be no data analysis at all). But, if you are required to collect and analyse data, you’ll need to pay a lot of attention to the methodology section. The video below provides an example of what the methodology section might look like.

By this stage of your paper, you will have explained what your research question is, what the existing literature has to say about that question, and how you analysed additional data to try to answer your question. So, the natural next step is to present your analysis of that data . This section is usually called the “results” or “analysis” section and this is where you’ll showcase your findings.

Depending on your school’s requirements, you may need to present and interpret the data in one section – or you might split the presentation and the interpretation into two sections. In the latter case, your “results” section will just describe the data, and the “discussion” is where you’ll interpret that data and explicitly link your analysis back to your research question. If you’re not sure which approach to take, check in with your professor or take a look at past papers to see what the norms are for your programme.

Alright – once you’ve presented and discussed your results, it’s time to wrap it up . This usually takes the form of the “ conclusion ” section. In the conclusion, you’ll need to highlight the key takeaways from your study and close the loop by explicitly answering your research question. Again, the exact requirements here will vary depending on your programme (and you may not even need a conclusion section at all) – so be sure to check with your professor if you’re unsure.

Step 3: Write and refine

Finally, it’s time to get writing. All too often though, students hit a brick wall right about here… So, how do you avoid this happening to you?

Well, there’s a lot to be said when it comes to writing a research paper (or any sort of academic piece), but we’ll share three practical tips to help you get started.

First and foremost , it’s essential to approach your writing as an iterative process. In other words, you need to start with a really messy first draft and then polish it over multiple rounds of editing. Don’t waste your time trying to write a perfect research paper in one go. Instead, take the pressure off yourself by adopting an iterative approach.

Secondly , it’s important to always lean towards critical writing , rather than descriptive writing. What does this mean? Well, at the simplest level, descriptive writing focuses on the “ what ”, while critical writing digs into the “ so what ” – in other words, the implications . If you’re not familiar with these two types of writing, don’t worry! You can find a plain-language explanation here.

Last but not least, you’ll need to get your referencing right. Specifically, you’ll need to provide credible, correctly formatted citations for the statements you make. We see students making referencing mistakes all the time and it costs them dearly. The good news is that you can easily avoid this by using a simple reference manager . If you don’t have one, check out our video about Mendeley, an easy (and free) reference management tool that you can start using today.

Recap: Key Takeaways

We’ve covered a lot of ground here. To recap, the three steps to writing a high-quality research paper are:

- To choose a research question and review the literature

- To plan your paper structure and draft an outline

- To take an iterative approach to writing, focusing on critical writing and strong referencing

Remember, this is just a b ig-picture overview of the research paper development process and there’s a lot more nuance to unpack. So, be sure to grab a copy of our free research paper template to learn more about how to write a research paper.

Can you help me with a full paper template for this Abstract:

Background: Energy and sports drinks have gained popularity among diverse demographic groups, including adolescents, athletes, workers, and college students. While often used interchangeably, these beverages serve distinct purposes, with energy drinks aiming to boost energy and cognitive performance, and sports drinks designed to prevent dehydration and replenish electrolytes and carbohydrates lost during physical exertion.

Objective: To assess the nutritional quality of energy and sports drinks in Egypt.

Material and Methods: A cross-sectional study assessed the nutrient contents, including energy, sugar, electrolytes, vitamins, and caffeine, of sports and energy drinks available in major supermarkets in Cairo, Alexandria, and Giza, Egypt. Data collection involved photographing all relevant product labels and recording nutritional information. Descriptive statistics and appropriate statistical tests were employed to analyze and compare the nutritional values of energy and sports drinks.

Results: The study analyzed 38 sports drinks and 42 energy drinks. Sports drinks were significantly more expensive than energy drinks, with higher net content and elevated magnesium, potassium, and vitamin C. Energy drinks contained higher concentrations of caffeine, sugars, and vitamins B2, B3, and B6.

Conclusion: Significant nutritional differences exist between sports and energy drinks, reflecting their intended uses. However, these beverages’ high sugar content and calorie loads raise health concerns. Proper labeling, public awareness, and responsible marketing are essential to guide safe consumption practices in Egypt.

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

Writing Research Papers: Part Two — Formatting Your Paper

Once you have decided on a topic for your paper and developed an outline and thesis statement ( get tips in Part One of our guide to writing research papers), you are ready to begin writing the paper itself. Here are some tips on structure and format.

Starting point: the introduction

Introductions should get the attention of your reader, introduce your main idea, and capture your argument. This part of the paper sets up the remainder of the material.

A few elements you may want to include in an effective introduction:

- a hook to get readers’ attention

- background (if necessary) of the topic

- your main idea or thesis

- a preview of the body of your essay (often contained in or found near a thesis statement)

Most introductions present a paper’s main point, but the rest of the details may vary. The introductory paragraph of a sociology exam may not include a “hook” but get right to the main claim of your essay. A longer essay may contain a significant introduction. You will want to evaluate your situation and choose what works best.

Not sure where to begin? If you’re stuck, try these strategies:

- Start writing the body of your paper. If the first paragraph isn’t coming to mind easily, look at your outline and start writing a paragraph that you feel more confident about.

- Think about your audience. For example, pet owners may be more invested if you explain why your proposed dog park helps their pets stay healthy and happy.

- Use trial and error. Your first introduction may not be your best, and that’s fine. Try listing several ideas at once and see which one seems best.

- Talk it out. Have friends and family read your work. Email your instructor. Read your work out loud.

- Take a break. Try one of these de-stressing suggestions from World Campus students.

If you’re stuck on your introduction, reach out to your instructor, your classmates, and your tutors. They can provide feedback on what you have written and may help you improve your text.

Ending on a good note

Endings can also be tricky when writing a research paper. Many students struggle with figuring out how to wrap things up, especially because you may feel pressure to end with a memorable line or important takeaway. And it is true that this will be one of the most important parts of your paper.

Every paper needs a convincing and memorable ending. Like a great punchline caps off a good joke, your conclusion will be the last thing that your readers read and remember about your paper. You want it to reinforce your point and drive home why your argument matters. But how do you do that?

You may take several approaches to writing a conclusion. There is no single “right” way to end a paper. A lot will depend on the tone and style of your paper — just as there are different ways in which you would end a verbal conversation, depending on the situation. The point is the same for conversations and for papers: help your reader (or listener) remember your main point and (hopefully) be persuaded by it.

When you draft your conclusion, try to ask yourself these questions about your paper. Your answers may help guide your conclusion.

- What should your reader remember? Summarize the most important information.

- What should your reader do in response to your paper? Call for that action.

- Why should they care about your main point? Appeal to your readers’ self-interest.

Depending on the goal of your paper, your conclusion may change its focus. If you’re writing a paper about recycling, you may want your reader to do something, such as call their city council members, write a letter to a center, or start recycling.

One final tip: Sometimes, less is more! If you get stuck with your conclusion, remember it doesn’t have to be long to be effective. You may be able to write a shorter conclusion and get the same effect.

For more on conclusions, check out this video .

Rubrics and grading

Being truly successful in writing a college paper — and earning a good grade — requires more than just good writing and research skills. You also must be sure to meet all of the requirements specified by your instructor. These are often detailed in what is known as a rubric.

A rubric is a ranking system used by instructors to grade an assignment based on specific criteria. A rubric can also tell you what your instructor expects from a quality assignment and can guide you as you write a paper. Other times, the instructor will simply explain the guidelines or grading criteria via written instructions.

As you prepare for a paper or any assignment, read and reread the assignment description or rubric provided by your instructor. Check to make sure you have understood each piece and addressed it. All of these tools can help you understand your instructor’s expectations for the assignment.

Here are a few other ways that rubrics or assignment instructions can help you:

- Follow directions. Your instructor includes only important information in a rubric, and a rubric can remind you of important pieces of an assignment that you may have missed.

- Focus on significant areas of an assignment.

- Revise effectively. A rubric can remind you of an area for revision.

Penn State University Libraries has created a collection of Information Literacy Modules that provides helpful information that can guide you in writing papers and completing other assignments. Modules include:

- Sources of Information

- Searching for Information

- Presenting Research and Data

- Citations and Academic Integrity

Photo by Keira Burton from Pexels

Related Articles

Subscribe to receive the latest posts by Penn State World Campus in your email box.

- How to write a research paper

Last updated

11 January 2024

Reviewed by

With proper planning, knowledge, and framework, completing a research paper can be a fulfilling and exciting experience.

Though it might initially sound slightly intimidating, this guide will help you embrace the challenge.

By documenting your findings, you can inspire others and make a difference in your field. Here's how you can make your research paper unique and comprehensive.

- What is a research paper?

Research papers allow you to demonstrate your knowledge and understanding of a particular topic. These papers are usually lengthier and more detailed than typical essays, requiring deeper insight into the chosen topic.

To write a research paper, you must first choose a topic that interests you and is relevant to the field of study. Once you’ve selected your topic, gathering as many relevant resources as possible, including books, scholarly articles, credible websites, and other academic materials, is essential. You must then read and analyze these sources, summarizing their key points and identifying gaps in the current research.

You can formulate your ideas and opinions once you thoroughly understand the existing research. To get there might involve conducting original research, gathering data, or analyzing existing data sets. It could also involve presenting an original argument or interpretation of the existing research.

Writing a successful research paper involves presenting your findings clearly and engagingly, which might involve using charts, graphs, or other visual aids to present your data and using concise language to explain your findings. You must also ensure your paper adheres to relevant academic formatting guidelines, including proper citations and references.

Overall, writing a research paper requires a significant amount of time, effort, and attention to detail. However, it is also an enriching experience that allows you to delve deeply into a subject that interests you and contribute to the existing body of knowledge in your chosen field.

- How long should a research paper be?

Research papers are deep dives into a topic. Therefore, they tend to be longer pieces of work than essays or opinion pieces.

However, a suitable length depends on the complexity of the topic and your level of expertise. For instance, are you a first-year college student or an experienced professional?

Also, remember that the best research papers provide valuable information for the benefit of others. Therefore, the quality of information matters most, not necessarily the length. Being concise is valuable.

Following these best practice steps will help keep your process simple and productive:

1. Gaining a deep understanding of any expectations

Before diving into your intended topic or beginning the research phase, take some time to orient yourself. Suppose there’s a specific topic assigned to you. In that case, it’s essential to deeply understand the question and organize your planning and approach in response. Pay attention to the key requirements and ensure you align your writing accordingly.

This preparation step entails

Deeply understanding the task or assignment

Being clear about the expected format and length

Familiarizing yourself with the citation and referencing requirements

Understanding any defined limits for your research contribution

Where applicable, speaking to your professor or research supervisor for further clarification

2. Choose your research topic

Select a research topic that aligns with both your interests and available resources. Ideally, focus on a field where you possess significant experience and analytical skills. In crafting your research paper, it's crucial to go beyond summarizing existing data and contribute fresh insights to the chosen area.

Consider narrowing your focus to a specific aspect of the topic. For example, if exploring the link between technology and mental health, delve into how social media use during the pandemic impacts the well-being of college students. Conducting interviews and surveys with students could provide firsthand data and unique perspectives, adding substantial value to the existing knowledge.

When finalizing your topic, adhere to legal and ethical norms in the relevant area (this ensures the integrity of your research, protects participants' rights, upholds intellectual property standards, and ensures transparency and accountability). Following these principles not only maintains the credibility of your work but also builds trust within your academic or professional community.

For instance, in writing about medical research, consider legal and ethical norms , including patient confidentiality laws and informed consent requirements. Similarly, if analyzing user data on social media platforms, be mindful of data privacy regulations, ensuring compliance with laws governing personal information collection and use. Aligning with legal and ethical standards not only avoids potential issues but also underscores the responsible conduct of your research.

3. Gather preliminary research

Once you’ve landed on your topic, it’s time to explore it further. You’ll want to discover more about available resources and existing research relevant to your assignment at this stage.

This exploratory phase is vital as you may discover issues with your original idea or realize you have insufficient resources to explore the topic effectively. This key bit of groundwork allows you to redirect your research topic in a different, more feasible, or more relevant direction if necessary.

Spending ample time at this stage ensures you gather everything you need, learn as much as you can about the topic, and discover gaps where the topic has yet to be sufficiently covered, offering an opportunity to research it further.

4. Define your research question

To produce a well-structured and focused paper, it is imperative to formulate a clear and precise research question that will guide your work. Your research question must be informed by the existing literature and tailored to the scope and objectives of your project. By refining your focus, you can produce a thoughtful and engaging paper that effectively communicates your ideas to your readers.

5. Write a thesis statement

A thesis statement is a one-to-two-sentence summary of your research paper's main argument or direction. It serves as an overall guide to summarize the overall intent of the research paper for you and anyone wanting to know more about the research.

A strong thesis statement is:

Concise and clear: Explain your case in simple sentences (avoid covering multiple ideas). It might help to think of this section as an elevator pitch.

Specific: Ensure that there is no ambiguity in your statement and that your summary covers the points argued in the paper.

Debatable: A thesis statement puts forward a specific argument––it is not merely a statement but a debatable point that can be analyzed and discussed.

Here are three thesis statement examples from different disciplines:

Psychology thesis example: "We're studying adults aged 25-40 to see if taking short breaks for mindfulness can help with stress. Our goal is to find practical ways to manage anxiety better."

Environmental science thesis example: "This research paper looks into how having more city parks might make the air cleaner and keep people healthier. I want to find out if more green spaces means breathing fewer carcinogens in big cities."

UX research thesis example: "This study focuses on improving mobile banking for older adults using ethnographic research, eye-tracking analysis, and interactive prototyping. We investigate the usefulness of eye-tracking analysis with older individuals, aiming to spark debate and offer fresh perspectives on UX design and digital inclusivity for the aging population."

6. Conduct in-depth research

A research paper doesn’t just include research that you’ve uncovered from other papers and studies but your fresh insights, too. You will seek to become an expert on your topic––understanding the nuances in the current leading theories. You will analyze existing research and add your thinking and discoveries. It's crucial to conduct well-designed research that is rigorous, robust, and based on reliable sources. Suppose a research paper lacks evidence or is biased. In that case, it won't benefit the academic community or the general public. Therefore, examining the topic thoroughly and furthering its understanding through high-quality research is essential. That usually means conducting new research. Depending on the area under investigation, you may conduct surveys, interviews, diary studies , or observational research to uncover new insights or bolster current claims.

7. Determine supporting evidence

Not every piece of research you’ve discovered will be relevant to your research paper. It’s important to categorize the most meaningful evidence to include alongside your discoveries. It's important to include evidence that doesn't support your claims to avoid exclusion bias and ensure a fair research paper.

8. Write a research paper outline

Before diving in and writing the whole paper, start with an outline. It will help you to see if more research is needed, and it will provide a framework by which to write a more compelling paper. Your supervisor may even request an outline to approve before beginning to write the first draft of the full paper. An outline will include your topic, thesis statement, key headings, short summaries of the research, and your arguments.

9. Write your first draft

Once you feel confident about your outline and sources, it’s time to write your first draft. While penning a long piece of content can be intimidating, if you’ve laid the groundwork, you will have a structure to help you move steadily through each section. To keep up motivation and inspiration, it’s often best to keep the pace quick. Stopping for long periods can interrupt your flow and make jumping back in harder than writing when things are fresh in your mind.

10. Cite your sources correctly