The Importance of Faith in Times of Crisis

Saint Joseph’s religious leaders and experts reflect on how the quarantine can serve as an opportunity to connect virtually, contemplate God’s will and strengthen our faith and humanity

Written by: Erin O'Boyle

Published: April 28, 2020

Total reading time: 5 minutes

In times of crisis and uncertainty, many people look to religion for guidance and consolation. But the COVID-19 pandemic, which resulted in physical distancing across the country and world in recent weeks and months, has made even the most common displays of faith more complicated.

For religions in America and abroad, the pandemic has necessitated a rethinking of how to worship, and many churches, synagogues and mosques have halted their public services to stop the spread of COVID-19. The timing of the pandemic in April was particularly difficult for faith leaders and congregants to determine how to observe Easter, Passover and the start of Ramadan.

We asked three faculty members from the Department of Theology and Religious Studies at Saint Joseph’s University to tell us how worship and expressions of faith have changed for different populations – including Christians, Jews and Muslims – during the quarantine.

Philip Cunningham, Ph.D., professor of theology and the director of the Institute for Jewish-Catholic Relations, wondered about the physical interactions of Easter week in the Catholic Church, such as receiving communion, or the washing of the feet during Holy Thursday mass. “What does it say about the ability to celebrate [rituals] and Christ’s example of befriending others and being of service, when you’re in an empty building?”

On the topic of serving others, professions such as nursing and medicine and supply chain industries have elevated the ideal of service at a time when it’s needed most, he says. “We should be thanking the people who stock grocery shelves, deliver mail and deliver food. There are now elements of risk in doing the ordinary, mundane tasks that deserve people’s gratitude. It has made us aware of things taken for granted, dismissed as mundane and pedestrian. We in the West aren’t used to having our lives interrupted, so this makes us value the everyday ordinariness more.”

Human connection is also a fundamental part of expressing one’s faith, and it is manifesting in new ways. Cunningham noted that the coronavirus quarantine has changed the way people celebrate religious holidays with family and friends. “When we have to physically distance, there’s a greater sensitivity that we miss being physically together,” he observes. “The internet is serving as a way to have conversations you wouldn’t normally have when physically with someone. On Easter, I Zoomed with several relatives in England whom I wouldn’t have seen under normal circumstances.”

Umeyye Isra Yazicioglu, Ph.D., associate professor of theology and religious studies, also spoke of how online experiences have changed the way people interact with each other. “Coronavirus has opened conversations about faith and religion, more so than had there been no virus,” she notes.

When we have to physically distance, there’s a greater sensitivity that we miss being physically together.”

Philip Cunningham, Ph.D.

Yazicioglu’s weekly Quran study ordinarily consisted of about four members, but that number has increased to about a dozen since transitioning to Zoom, she reports. Likewise, online lectures and discussions with spiritual scholars that she frequents have doubled or tripled in participation.

Muslims may also use this time for soul-searching, Yazicioglu explains. “There is an Islamic belief that everything happens with divine will and wisdom. How noble are we as creatures, that we might forget that we’re dependent beings and don’t have self-sufficiency? We’ve done so many grand things, like landing on the moon and on Mars. But this tiny virus has put us in our homes. We need to recognize we’re vulnerable, we took God’s blessings for granted, and we don’t have control.”

In times of crisis, Muslims are encouraged to ask forgiveness from God. “It’s a time to reflect on how we may be abusing our powers,” Yazicioglu says. “It’s time to notice mistakes. To wake yourself up because you’re missing your priorities.” She explains that asking forgiveness for complacency is important. “Maybe on a collective level, in a larger scheme, things are going wrong and you’re complacent. You should ask forgiveness. You can also ask forgiveness for others.”

Rabbi Abraham Skorka, Ph.D., visiting university professor, addressed the much larger question of why this global disaster is happening. “Pain leads us to ask things about God and His behavior toward human beings,” Skorka says. “For many people, this is a time of suffering. Not having the possibility to see your family and loved ones – that is suffering. And some have actually lost loved ones.” The Book of Job in the Hebrew Bible is devoted entirely to suffering, he notes. “The most important lesson we can learn from this book is that we cannot absolutely understand the ways of God, and it is forbidden to try to explain. Pain is part of our lives. It’s a reality. We cannot ascribe motives to God as an explanation.”

Skorka says our current condition is an opportunity to spend some time in silence, so that we may hear the voice of our conscience. “Silence is a great element in Jewish spirituality. God appeared to Moses in silence and solitude. God revealed himself to the people of Israel in the desert and wilderness,” he says, adding that sound provides people an escape from difficult questions including the meaning of life.

In the end, he urges people to remember that everything we receive from God is for good.

“When this pandemic is over, hopefully humanity will have learned something,” Skorka reflects. “And if you are scared, you will always have one thing to face fear: hope. Hope that God will help, and hope that a better time will come.”

Saint Joseph’s President Joins Philadelphia Mayor’s Eds and Meds Roundtable

As one of a dozen leaders, Dr. McConnell will advise on major Philadelphia sectors.

Heading Down the Shore? Saint Joseph’s PharmD Candidates Explain Why You Should Think Twice When Selecting Sunscreen

Colleen Huzinec, PharmD ’25, and Luz Rosario, PharmD ’25, discuss key factors consumers should consider when choosing sunscreen.

How Inflation, Online Shopping and Artificial Intelligence Will Impact This Holiday Shopping Season

Saint Joseph’s faculty experts weigh in on various factors impacting both consumers and businesses this holiday season.

Numbers, Facts and Trends Shaping Your World

Read our research on:

Full Topic List

Regions & Countries

- Publications

- Our Methods

- Short Reads

- Tools & Resources

Read Our Research On:

- More Americans Than People in Other Advanced Economies Say COVID-19 Has Strengthened Religious Faith

Nearly three-in-ten U.S. adults say the outbreak has boosted their faith; about four-in-ten say it has tightened family bonds

Table of contents.

- Acknowledgments

- Methodology

This analysis focuses on views of religious faith and family relationships around the world during the COVID-19 pandemic . It builds on research released in the fall of 2020 about responses in 14 countries to the coronavirus outbreak and U.S. public perceptions of how the pandemic has affected religious beliefs and family situations .

Data for this report is drawn from nationally representative telephone surveys conducted from June 10 to Aug. 3, 2020, among 14,276 adults in 14 advanced economies: the United States, Canada, Belgium, Denmark, France, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Spain, Sweden, the United Kingdom, Australia, Japan and South Korea.

Face-to-face interviews were not possible in many parts of the world due to the coronavirus outbreak, so the study includes only countries where nationally representative telephone surveys were feasible.

The pandemic situation has changed substantially since the survey was conducted. In many European countries, for example, the number of coronavirus cases and deaths was relatively low during the survey period but subsequently spiked in the fall and winter . On the other hand, cases began to rise during the fielding period in Australia , Japan and the U.S. ; more recent surges in Japan and the U.S. have since eclipsed those summer outbreaks.

Here are the questions used for the report, along with responses, and the survey methodology .

As the coronavirus pandemic continues to cause deaths and disrupt billions of lives globally, people may turn to religious groups, family, friends, co-workers or other social networks for support. A Pew Research Center survey conducted in the summer of 2020 reveals that more Americans than people in other economically developed countries say the outbreak has bolstered their religious faith and the faith of their compatriots.

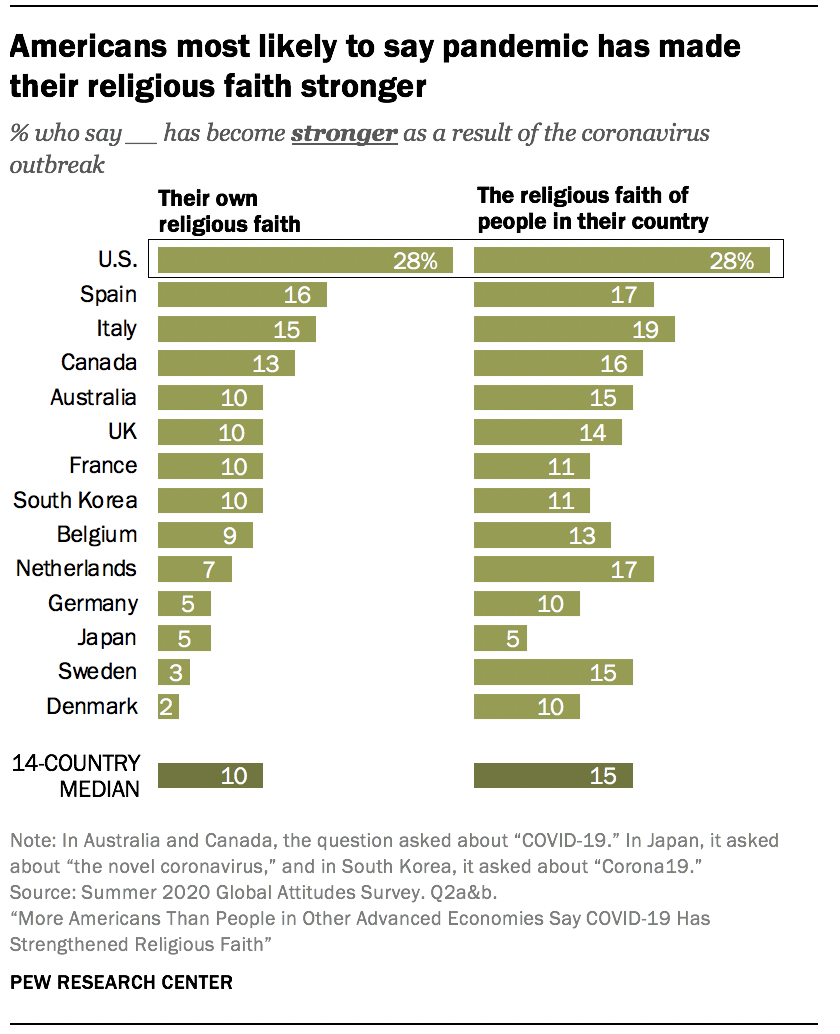

Nearly three-in-ten Americans (28%) report stronger personal faith because of the pandemic, and the same share think the religious faith of Americans overall has strengthened, according to the survey of 14 economically developed countries.

Far smaller shares in other parts of the world say religious faith has been affected by the coronavirus. For example, just 10% of British adults report that their own faith is stronger as a result of the pandemic, and 14% think the faith of Britons overall has increased due to COVID-19. In Japan, 5% of people say religion now plays a stronger role in both their own lives and the lives of their fellow citizens.

Majorities or pluralities in all the countries surveyed do not feel that religious faith has been strengthened by the pandemic, including 68% of U.S. adults who say their own faith has not changed much and 47% who say the faith of their compatriots is about the same.

Some previous studies have found an uptick in religious observance after people experience a calamity. And a Pew Research Center report published in October 2020 showed that roughly a third (35%) of Americans say the pandemic carries one or more lessons from God.

When it comes to questions about strength of religious belief, the wide variation in responses across countries may reflect differences in the way people in different countries view the role of religion in their private and public lives.

European countries experienced rapid secularization starting in the 19th century , and today, comparatively few people in Italy (25%), the Netherlands (17%) or Sweden (9%) say that religion is very important in their lives. 1 East Asian countries such as Japan and South Korea have low rates of religious affiliation and observance – at least by Western-centric measures.

The state of the pandemic during the summer 2020 survey period

Pew Research Center’s survey was conducted June 10 to Aug. 3, 2020, when all of the countries surveyed were under social distancing and/or national lockdown orders due to COVID-19. Even though the coronavirus is a global pandemic, not all countries have experienced the disease in the same way. During the fielding period, Australia , Japan and the United States had rising numbers of infections, while Italy and some other European countries had started to recover from the large number of cases reported in April and May. Nearly all countries surveyed experienced significant spikes in infections and deaths in the fall and winter.

The worsening of the pandemic, including tightening restrictions after the survey was conducted, may have affected views of faith and family since the summer of 2020. Attitudes also may continue to shift as the pandemic evolves. Nevertheless, if the differences between the U.S. and other economically developed countries on religion-related questions have deeper roots, they may persist even as the pandemic wears on, and the same may be true of differences between demographic groups within countries.

The United States recently has experienced some trends toward secularization , including a growing share of the population that does not identify with any religion and a shrinking share of people who say they regularly attend a church or other house of worship. Still, religion continues to play a stronger role in American life than in many other economically developed countries. For example, nearly half of Americans (49%) say religion is very important in their lives, compared with 20% in Australia, 17% in South Korea and just 9% in Japan.

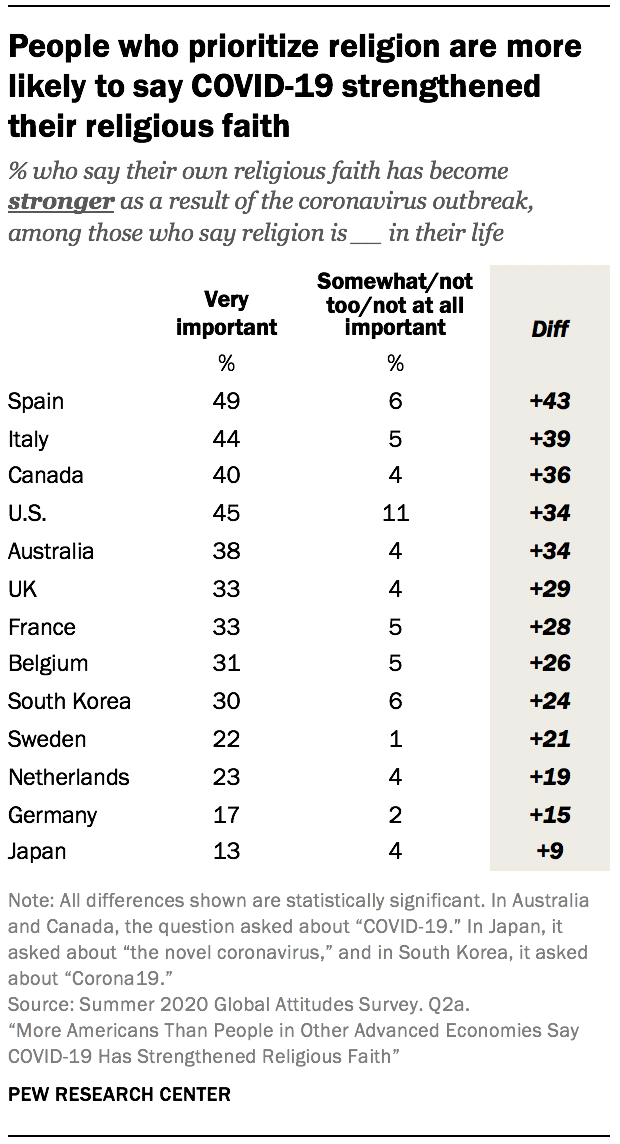

In nearly every country surveyed, those who say religion is very important in their lives are more likely to say both their own faith and that of their compatriots has grown due to the pandemic. Americans’ greater proclivity to turn to religion amid the pandemic is largely driven by the relatively high share of religious Americans (In several countries, those who say religion is somewhat, not too or not at all important to them personally are less likely take a clear position either way on how their faith has been affected by the pandemic.)

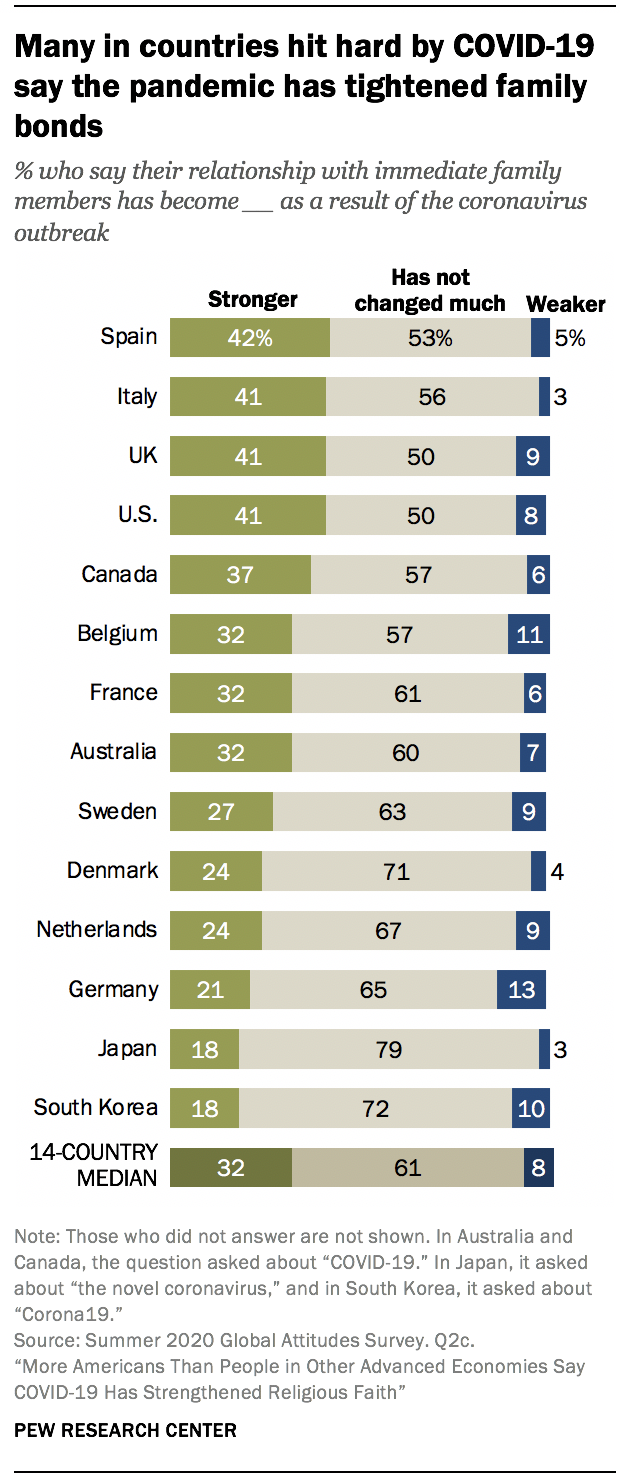

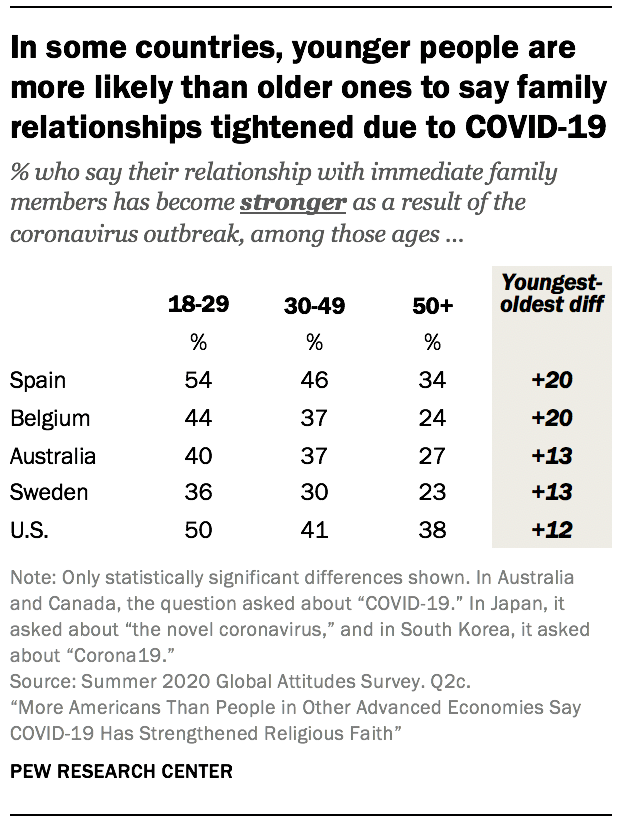

Religion is just one of many aspects of life that have been touched by the pandemic. Family relationships, too, have been affected by lockdowns, economic turmoil and the consequences of falling ill. Many in countries that were hit hard by initial waves of infections and deaths in the spring say their family relationships have strengthened. That is the case in Spain (42%), Italy, the UK and the U.S. (41% each). In the U.S. and in several other countries, younger adults are especially likely to say they feel a stronger bond with immediate family members since the start of the pandemic.

These are among the findings of a Pew Research Center survey conducted June 10 to Aug. 3, 2020, among 14,276 adults in 14 countries.

Americans most likely to say COVID-19 bolstered religious faith, though majorities around world see little change

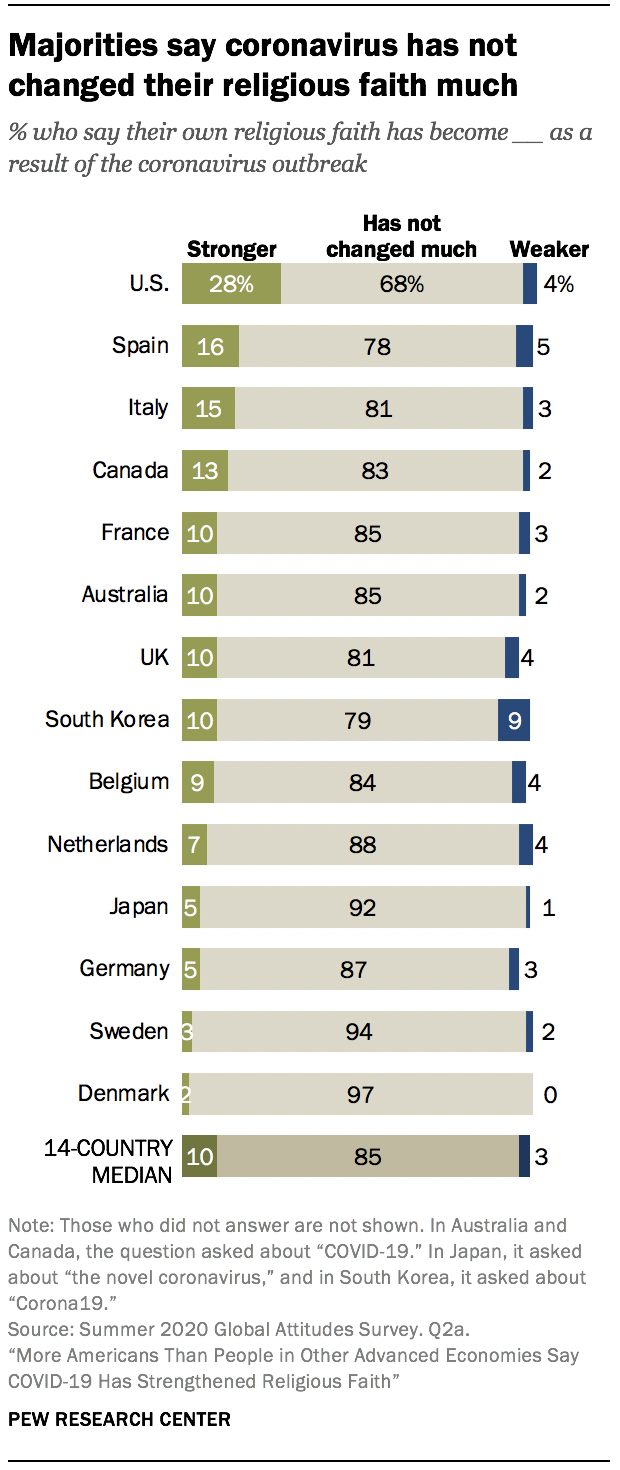

In 11 of 14 countries surveyed, the share who say their religious faith has strengthened is higher than the share who say it has weakened. But generally, people in developed countries don’t see much change in their own religious faith as a result of the pandemic.

A median of 10% across 14 developed countries say their own religious faith has become stronger as a result of the coronavirus outbreak, while a median of 85% say their religious faith had not changed much.

Among the countries surveyed, the U.S. has by far the highest share of respondents who say their faith has strengthened, with about three-in-ten holding this view.

By contrast, in Spain and Italy, two of Western Europe’s more religious countries, roughly one-in-six people say their own religious faith has grown due to the pandemic.

In Canada, 13% say their religious faith has become stronger because of COVID-19. And in other countries surveyed, one-in-ten or fewer report deeper faith due to the coronavirus outbreak.

The pandemic has led to the cancellation of religious activities and in-person services around the world, but few people say their religious faith has weakened as a result of the outbreak. Across the countries surveyed, a median of just 3% say their own religious faith has decreased, including 4% in the U.S. In South Korea, 9% say their personal faith has become weaker as a result of the coronavirus outbreak, making it the country where people are most likely to hold this view.

Perceptions about the pandemic’s influence on faith are tied to people’s own levels of observance – those who are more religious are more likely than their less religious compatriots to say COVID-19 has strengthened their faith and that of others in their country.

In Spain, for example, 49% of those who say religion is very important in their lives say their own religious faith has been bolstered because of the pandemic, compared with 6% among those who say religion is less important. A similar pattern occurs in the U.S.: 45% of those who say religion is very important in their lives say the pandemic has made their faith stronger, compared with 11% who consider religion less important. Overall, 24% of Spanish adults say religion is very important in their lives, as do 49% of Americans.

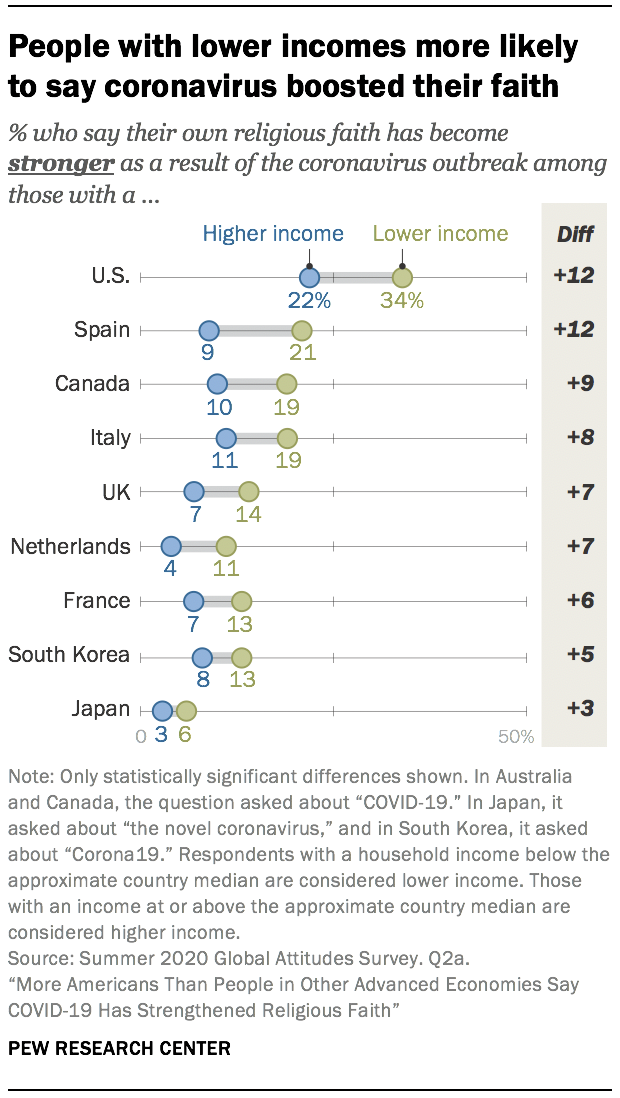

Wealth and education also play a role: In some countries, people with lower incomes and less education are somewhat more likely than others to say the pandemic has bolstered their religious faith.

When it comes to income, the largest gaps appear in the U.S. and Spain, where people at or below the national median income are 12 percentage points more likely than the rest of the population to say their religious faith has become stronger. There are also significant differences by income group in Canada, Italy, the UK, the Netherlands, France, South Korea and Japan.

People with less education are significantly more likely than those with a secondary education or higher to say their personal religious faith has deepened in five of the countries surveyed: Spain (those with less education are 11 points more likely to say this), Italy (8 points), the U.S. (7 points), France (5 points) and Japan (3 points).

There are few differences on this question by gender, even though women are generally more religious than men, particularly in Christian-majority countries . Two exceptional cases in this survey are Italy and South Korea, where women are more likely than men to report that their faith has been bolstered by the pandemic.

Americans most likely to say country is more religious because of pandemic

The survey also asked people if the strength of religious faith in their country as a whole has changed due to the pandemic. Responses largely mirror how people answer the question about their own religious faith, although respondents may additionally be taking into account their views on the role of religion in their nation’s public life.

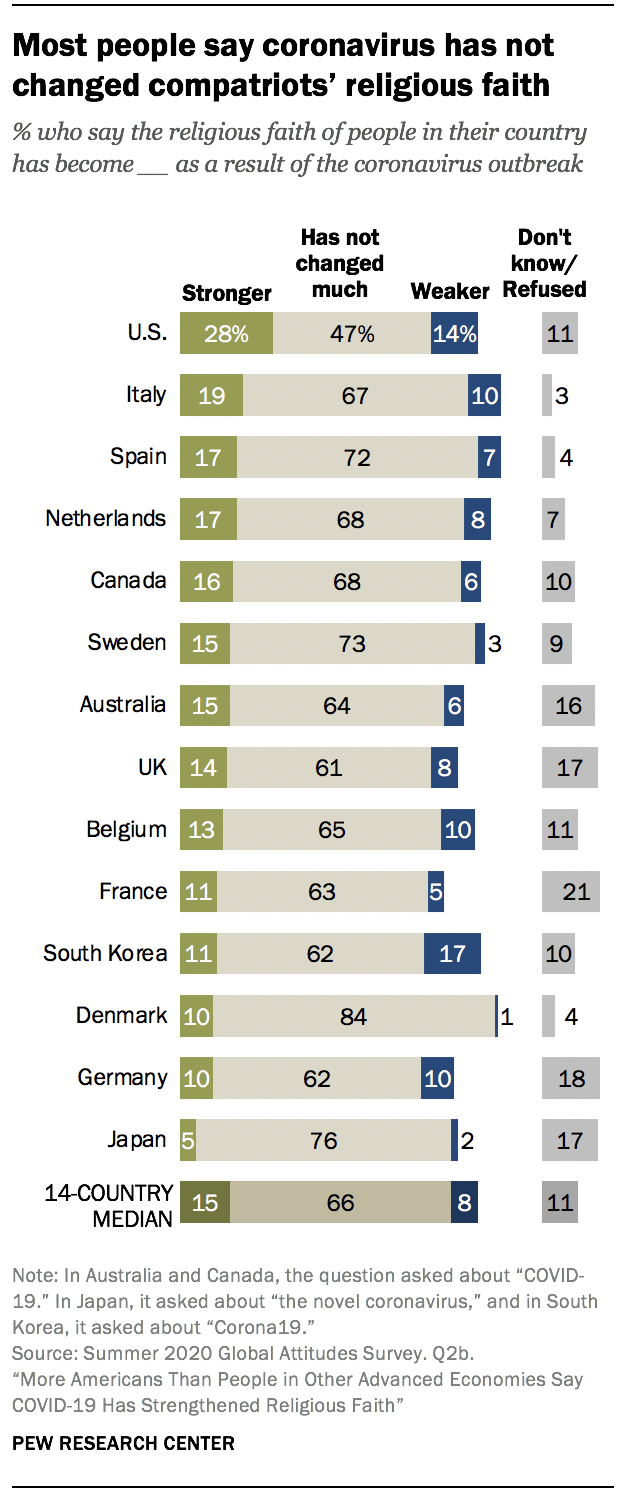

Majorities in nearly every country surveyed say that the religious faith of people in their country has not changed much as a result of the pandemic. A 14-country median of 66% say the religious faith of people in their country is about the same as before the pandemic, while 15% say faith in their country has become stronger and 8% say it has become weaker.

Among Americans, about half of adults surveyed (47%) say the religious faith of people in the U.S. has not changed much, while 28% say the country has become more religious. A relative handful of Americans (14%) think that religious faith in their country has weakened as a result of the coronavirus outbreak.

In some countries, significantly more people say their country has experienced religious renewal than say they themselves have greater religious faith. In the Netherlands, 17% say their country has become more religious, even though just 7% of Dutch adults say they, personally, are now more religious. In Sweden, 15% say the religious faith in their country is stronger, compared with 3% who say they themselves have experienced stronger religious faith.

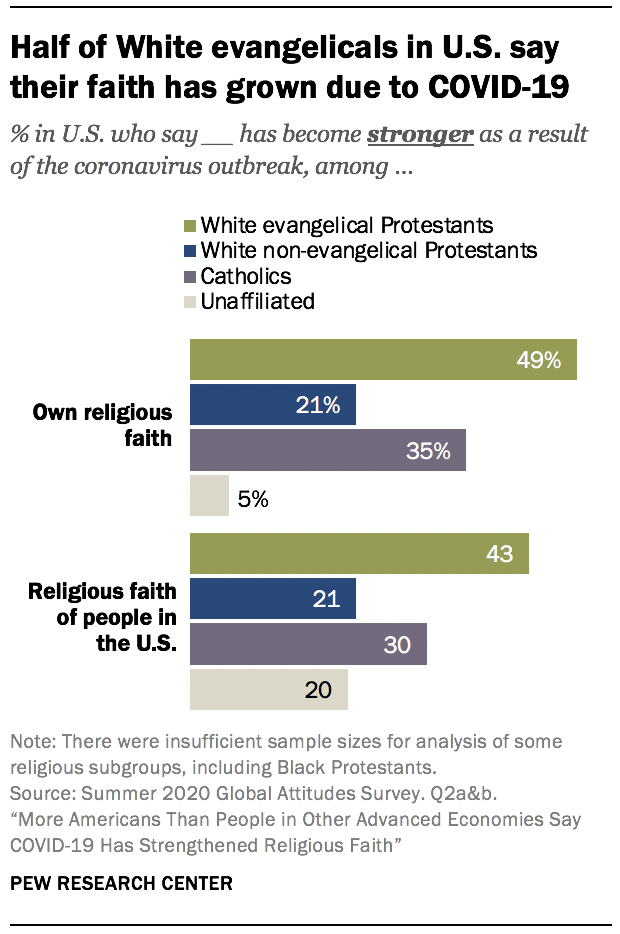

In the U.S., White evangelicals most likely to say COVID-19 boosted faith

White evangelical Protestants in the U.S. – one of the most religious groups in the country , by a variety of standard measures – are among the most likely to see stronger faith due to the coronavirus outbreak. Nearly half (49%) say their own religious faith has grown, while 43% say the same about the faith of Americans as a whole.

Three-in-ten U.S. Catholics say Americans’ religious faith has strengthened, while roughly a third report that their own religious faith has become stronger. Non-evangelical (mainline) Protestants show a similar pattern: Roughly two-in-ten say their own faith has deepened, while another 21% offer a similar assessment of other Americans’ religious faith.

Just 5% of Americans who report no religious affiliation say their religious faith has increased due to the coronavirus outbreak. However, 20% of unaffiliated people say they see deeper religious faith among Americans in general.

Family bonds have strengthened for many in countries surveyed

Religion is by no means the only way people cope with crisis. Family relationships are often a bulwark of support. And as many families in countries surveyed remain confined to their homes because of mandated work from home and closed or virtual schools , more people say their relationships with immediate family members have become stronger than say these relationships have weakened. A 14-country median of 32% say relationships have grown stronger, while just 8% say the opposite. Majorities in 11 countries say the coronavirus outbreak has not changed their relationship to immediate family much.

About four-in-ten adults surveyed in Spain, Italy, the U.S. and the UK say their relationship with immediate family has strengthened. By contrast, only about two-in-ten in Germany, Japan and South Korea say they now have deeper relationships with their family.

Record numbers of younger adults in the U.S. have moved home since the start of the pandemic, and young Americans are more likely than their older counterparts to say their relationships with immediate family members have strengthened. Half of U.S. adults ages 18 to 29 say their family bonds have tightened, compared with 38% of those ages 50 and older. Similar age gaps appear in Spain and Belgium (both 20 points), as well as Australia and Sweden (13 points).

- Chadwick, Owen. 1975. “The Secularization of the European Mind in the 19th Century.” ↩

Sign up for our weekly newsletter

Fresh data delivery Saturday mornings

Sign up for The Briefing

Weekly updates on the world of news & information

- Coronavirus (COVID-19)

- Religious Commitment

How Americans View the Coronavirus, COVID-19 Vaccines Amid Declining Levels of Concern

Online religious services appeal to many americans, but going in person remains more popular, about a third of u.s. workers who can work from home now do so all the time, how the pandemic has affected attendance at u.s. religious services, mental health and the pandemic: what u.s. surveys have found, most popular, report materials.

1615 L St. NW, Suite 800 Washington, DC 20036 USA (+1) 202-419-4300 | Main (+1) 202-857-8562 | Fax (+1) 202-419-4372 | Media Inquiries

Research Topics

- Email Newsletters

ABOUT PEW RESEARCH CENTER Pew Research Center is a nonpartisan fact tank that informs the public about the issues, attitudes and trends shaping the world. It conducts public opinion polling, demographic research, media content analysis and other empirical social science research. Pew Research Center does not take policy positions. It is a subsidiary of The Pew Charitable Trusts .

© 2024 Pew Research Center

Faith in a time of crisis

Psychologists’ research shows why some people can find peace during the COVID-19 pandemic, while others may be struggling with their faith.

- Belief Systems and Religion

Kay Bajwa, a real estate agent in Washington, D.C., spends her time in quarantine praying five times a day and working with members of her mosque to find ways to help the less fortunate during these difficult times. “This whole ordeal is bringing us closer together and closer to Allah,” she says. “Spending time praying and being with him is comforting.”

Bajwa is not alone in turning to her faith to weather life’s storms. Religion and belief are now seen by many researchers and clinicians as an important way to cope with trauma and distress thanks to research over the last three decades.

“Religion was largely looked upon as an immature response to difficult times,” says Kenneth Pargament, PhD, professor emeritus of psychology at Bowling Green State University, who since the 1980s has been on the forefront of the research on religion and resilience.

Despite the attitudes he faced at the time, Pargament and a handful of others pressed on, conducting research on the impact of religion on people’s mental health. That research identified positive and negative forms of religious coping — as well as evidence that how people experience and express their faith has implications for their well-being and health. “People who made more use of positive religious coping methods had better outcomes than those who struggled with God, their faith or other people about sacred matters,” Pargament says.

Positive and negative aspects

What are those positive effects? Research shows that religion can help people cope with adversity by:

- Encouraging them to reframe events through a hopeful lens. Positive religious reframing can help people transcend stressful times by enabling them to see a tragedy as an opportunity to grow closer to a higher power or to improve their lives, as is the case with Bajwa.

- Fostering a sense of connectedness. Some people see religion as making them part of something larger than themselves. This can happen through prayer or meditation, or through taking part in religious meetings, listening to spiritual music or even walking outside.

- Cultivating connection through rituals . Religious rituals and rites of passage can help people acknowledge that something momentous is taking place. These events often mark the beginning of something, as is the case with weddings, or the end of something, as is the case with funerals. They help guide and sustain people through life’s most difficult transitions.

“It is extremely important that people use their beliefs in a way that makes them feel empowered and hopeful,” says Thomas Plante, PhD, a professor of psychology at Santa Clara University. “Because it can be remarkably helpful in terms of managing stress during times like these.”

Unfortunately, religious beliefs may also undermine healing during stressful times. These negative religious expressions include:

- Feeling punished by God or feeling angry toward a higher being. Trauma and tragedy can challenge conceptions of God as all-loving and protective. As a result, some people struggle in their relationship with God and experience feelings of anger, abandonment or being punished by a higher power.

- Putting it all “in God’s hands.” When people engage in “religious deferral,” they believe God is in charge of their well-being and may not take the necessary steps to protect themselves. One example of this deferral is church leaders who say God will protect their congregations as they hold church services in defiance of physical distancing guidelines aimed at reducing the spread of COVID-19.

- Falling into moral struggles . People can have difficulty squaring their behavior with their moral and spiritual values. For example, health-care providers who are on the front lines of treating coronavirus patients may describe the anguish they feel as they are being forced to decide how to allocate limited life-sustaining resources, decisions that put them in the uncomfortable role of playing God.

Takeaways for people of faith — and those without

Even though you cannot congregate due to physical distancing rules, there are many ways to lift your spirits right now, says Plante. “You can play a spiritual or uplifting song, you can join fellow congregants on Zoom or you can decide to help other people by giving to those in need.” Bajwa says she is inspired by both the practical and spiritual information she is getting during Zoom calls with members of her mosque.

“We are inviting doctors and financial advisors to hold seminars on key topics during our Zoom meetings, and they are giving us a lot of information that is helping us with all of the issues that are popping up during this difficult period,” she says. “Our leaders are coupling the seminars with emotional and spiritual support, which is really helpful.”

Plante says that the benefits of religion are not exclusive to believers. “There are so many religious practices that are now used by non-believers,” he says. “Yoga comes from Hinduism and mindful meditation from Buddhism, yet agnostics, atheists and people of all belief systems now take part in these traditions.”

Plante says atheists and agnostics can seek inspiration in literature, nature and by connecting with others, but he notes that the world’s religions are ready-made for when the world is turned on its head.

“Religion has been helping people get through hard times for thousands of years,” he says. “It’s tested and ready to go at a moment’s notice. Just read the psalms and you will see that it is all about people turning to God during troubled times.”

Further Reading

Religious coping among diverse religions: Commonalities and divergences. Abu-Raiya, H., & Pargament, K. I., Psychology of Religion and Spirituality, 2014,

Positive and negative religious coping styles as prospective predictors of well-being in African Americans Park, C. L., Holt, C. L., Le, D., Christie, J., & Williams, B. R., Psychology of Religion and Spirituality, 2017.

Religious struggle as a predictor of mortality among medically ill elderly patients: a 2-year longitudinal study. Pargament, KI; Koenig, HG; Tarakeshwar, N; Hahn, J., Archives of Internal Medicine, 2001.

Religious coping methods as predictors of psychological, physical and spiritual outcomes among medically ill elderly patients: a two-year longitudinal study. Pargament, KI; Koenig, HG; Tarakeshwar, N; Hahn, J., Journal of Health Psychology, 2004.

Two Sides of the Same Coin: The Positive and Negative Impact of Spiritual Religious Coping on Quality of Life and Depression in Dialysis Patients. Vitorino, L.M.; Lucchetti, L.G; Cortez P.J.; Soares, RDC; Santos, AE; Luchetti, AL; Cruz, JP; Cortez, PJ; Journal of Holistic Nursing , 2001.

- Psychological impact of COVID-19

- When COVID-19 meets pandemic hope: Existential care of and in the impossible

You may also like

Coronavirus Disease 2019

Keeping the faith: the power of prayer during covid-19, research reveals the value of faith-based positive living..

Posted July 12, 2020

Faith sustains when circumstances fail. Christians have celebrated this reality the world over, but perhaps never in recent times in quite the way we have seen during the COVID-19 pandemic. Calling the virus “novel” also characterizes the way society has responded, with unprecedented measures, quarantines, laws, and regulations that have seriously disrupted life to try and contain the spread of the disease.

Faith and Health

Many have written about the power of faith, and how it impacts well-being. Harold G. Koenig (2020), in a piece specific to the pandemic entitled “Maintaining Health and Well-Being by Putting Faith into Action During the Covid-19 Pandemic,”[i] discusses a variety of different faith traditions but tied the discussion to the adverse impact of negative emotions on the body.

Koenig notes that emotions like fear and anxiety adversely impact our physiological systems that are designed to protect us from infection. Consequently, he notes that practicing our religious faith can help protect us from contracting COVID-19 and manage the symptoms if, God forbid, we become infected.

He notes that emotions such as anxiety and fear can actually heighten susceptibility to contracting the virus due to the adverse effects such emotions can have on immune functioning. On the other hand, he notes that positive emotions have the opposite effect on the immune system—supporting the goal of remaining hopeful and optimistic .

Koenig notes that positive emotions generated by religious activity such as reading Scripture and practicing faith actually benefits the immune system, a finding that he notes is increasingly corroborated by scientific research. He identifies religious faith as an important resource that many people use to maintain health and well-being.

Faith and Agency

Other researchers have tied positive mental health to the type of religious beliefs held. Yingling Liu and Paul Froese explored this issue in “Faith and Agency: The Relationships Between Sense of Control, Socioeconomic Status, and Beliefs About God” (2020).[ii] They found that although a person’s sense of control differs depending on degree of religiosity , the relational direction appears to vary based on a person’s image of God, as well as social status. Types of religious beliefs appear to explain how religion positively or negatively impacts sense of control.

Specifically, they found that “secure attachment to God and belief in divine control will compensate for social and economic deprivation.” In addition, they found believing in a judgmental God to be negatively related to agency, finding a “traditional fire‐and‐brimstone God” to be associated with a lower sense of control, in contrast to people who have more contemporary and individualized beliefs about God—which were associated with a sense of greater agency. This was particularly true for believers who were in need.

Liu and Froese explain that prior research establishes that sense of control, which is a measure of mental health and human agency, depends on a person’s socioeconomic status (SES) as well as religiosity. They also note that because it is a fundamental human need, a sense of control is a significant factor contributing to both mental and physical well‐being, and it also overlaps with other mental health measures “such as agency, internal locus of control , and mastery.”

A stronger sense of self-control appears to have other benefits as well. The authors note that it is linked with lower mortality rates, less symptoms of depression , and quicker recovery from illness.

Relational Closeness

In explaining their results, Liu and Froese note that secure attachment to God resembles other psychological measures of relational closeness—such as closeness to others, and accordingly, produces a variety of social and psychological benefits. They recognize that in terms of being a measure of theology or religiosity, secure attachment to God “highlights the positive aspects of belief—those feelings of security and love that can come with faith.” They note that consequently, secure attachment to God reflects individualized and therapeutic benefits of faith.

Liu and Froese note that people who experience low secure attachment to God, even though they may be “highly religious,” do not receive the same benefits. They explain that subscribing to a belief in a judgmental God reflects a very different type of religiosity, reflecting a system of beliefs based on “moral strictness and fear of retributive justice,” which is very different from the comfort and closeness experienced through a sense of secure attachment to God. It is this latter type of attachment that Christians would explain represents the relationship they have with Jesus Christ.

The Power of Prayer

Both research and experience reveal the power of faith and prayer to positively impact believers both physically and psychologically. Especially during uncertain times, faith sustains, comforts, and provides a sense of control in an otherwise uncertain, seemingly unpredictable time in history.

[i] Koenig, Harold G. 2020. “Maintaining Health and Well-Being by Putting Faith into Action during the Covid-19 Pandemic.” Journal of Religion and Health, May. doi:10.1007/s10943-020-01035-2.

[ii] Liu, Yingling, and Paul Froese. 2020. “Faith and Agency: The Relationships between Sense of Control, Socioeconomic Status, and Beliefs about God.” Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 59 (2): 311–26. doi:10.1111/jssr.12655.

Wendy L. Patrick, J.D., Ph.D., is a career trial attorney, behavioral analyst, author of Red Flags , and co-author of Reading People .

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Online Therapy

- United States

- Brooklyn, NY

- Chicago, IL

- Houston, TX

- Los Angeles, CA

- New York, NY

- Portland, OR

- San Diego, CA

- San Francisco, CA

- Seattle, WA

- Washington, DC

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Self Tests NEW

- Therapy Center

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

Sticking up for yourself is no easy task. But there are concrete skills you can use to hone your assertiveness and advocate for yourself.

- Emotional Intelligence

- Gaslighting

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

Faith in the time of Coronavirus

The coronavirus pandemic is confusing and frightening for hundreds of millions of people. That is not surprising. Many around the world are sick and many others have died. Unless the situation changes dramatically, many more will fall ill and die around the globe. This crisis raises serious medical , ethical and logistical questions. But it raises additional questions for people of faith. So I would like to offer some advice from the Christian tradition, Ignatian spirituality and my own experience.

Resist panic. This is not to say there is no reason to be concerned, or that we should ignore the sound advice of medical professionals and public health experts. But panic and fear are not from God. Calm and hope are. And it is possible to respond to a crisis seriously and deliberately while maintaining an inner sense of calm and hope.

St. Ignatius Loyola, the founder of the Jesuits, often talked about two forces in our interior lives: one that draws us toward God and the other away from God. The one that draws us away from God, which he labeled the evil spirit, “causes gnawing anxiety, saddens and sets up obstacles. In this way it unsettles people by false reasons aimed at preventing their progress.” Sound familiar? Don’t lend credence to lies or rumors, or give in to panic. Trust what medical experts tell you, not those who fear monger. There is a reason they call Satan the “Prince of Lies.”

Panic, by confusing and frightening you, pulls you away from the help God wants to give you. It is not coming from God. What is coming from God? St. Ignatius tells us: God’s spirit “stirs up courage and strength, consolations, inspirations and tranquility.” So trust in the calm and hope you feel. That is the voice to listen to.

“Do not be afraid!,” as Jesus said many times.

Do n o t demonize . The other day a friend told me that when an elderly Chinese man got onto a subway car in New York City, the car emptied out as people started shouting slurs at him, blaming his country for spreading the virus. Resist the temptation to demonize or scapegoat, which increases in time of stress and shortages. Covid-19 is not a Chinese disease; it is not a “foreign” disease. It is no one’s “fault.” Likewise, the people who become infected are not to blame. Remember that Jesus was asked about a blind man: “Who sinned, that this man was born blind?” Jesus’ response: “No one” (Jn 9:2). Illness is not a punishment. So don’t demonize and don’t hate.

Many things have been cancelled because of the coronavirus. Love is not one of them.

Care for the sick. This pandemic may be a long haul; some of our friends and family may get sick and perhaps die. Do what you can to help others, especially the elderly, disabled, poor and isolated. Take the necessary precautions; don’t be reckless and don’t risk spreading the disease, but also don’t forget the fundamental Christian duty to help others. “I was sick, and you came to visit me,” said Jesus (Mt 25). And remember that Jesus lived during a time when people had no access to even the most rudimentary medical care, and so visiting the sick was just as dangerous, if not more, than it is today. Part of the Christian tradition is caring for the sick, even at some personal cost.

And do not close your hearts to the poor and those who have no or limited healthcare. Refugees, the homeless and migrants, for example, will suffer even more than the general population. Keep your heart open to all those in need. Don’t let your conscience become infected, too.

Pray . Catholic churches around the world are closing, with Masses and other parish services cancelled by many bishops. These are prudent and necessary measures designed to keep people healthy. But they come at some cost: For many people, this removes one of the most consoling parts of their lives—the Mass and the Eucharist—and isolates them even more from the community at a time when they most need support.

What can one do instead? Well, there are many televised and livestreamed Masses available, as well as ones broadcast on the radio. But even if you can’t find one, you can pray on your own. When you do, remember that you’re still part of a community. There is also the longstanding tradition in our church of receiving a “spiritual communion,” when, if you cannot participate in the Mass in person, you unite yourself with God in prayer.

Remember that you’re still part of a community.

And be creative. You can meditate on the Sunday Gospel on your own, consult a Bible commentary about the readings, gather your family to talk about the Gospel or call friends and share your experiences of how God is present to you, even in the midst of a crisis. The persecuted Christians in the early church prayed and shared their faith in the catacombs, and we can do the same. Remember that Jesus said, “Where two or three are gathered in my name, I am there among them” (Mt. 18:20). Remember too that the church is not a building. It is the community.

Trust that God is with you . Many people, especially those who are sick, may feel a sense of isolation that compounds their fear. And many of us, even if we’re not infected, will know people who are sick and even die. So most will naturally ask: Why is this happening?

Many people, especially those who are sick, may feel a sense of isolation that compounds their fear.

There is no satisfactory answer to that question, which at its core is the question of why suffering exists, something that saints and theologians have pondered over the centuries. In the end, it is the greatest of mysteries. And the question is: Can you believe in a God that you don’t understand?

At the same time, we know that Jesus understands our suffering and accompanies us in the most intimate of ways. Remember that during his public ministry Jesus spent a great deal of time with those who were sick. And before modern medicine, almost any infection could kill you. Thus, lifespans were short: only 30 or 40 years. In other words, Jesus knew the world of illness.

Jesus, then, understands all the fears and worries that you have. Jesus understands you, not only because he is divine and understands all things but because he is human and experienced all things. Go to him in prayer. And trust that he hears you and is with you.

Trust in my prayers, too. We will move through this together, with God’s help.

[Explore all of America’s in-depth coverage of the coronavirus pandemic]

The Rev. James Martin, S.J., is a Jesuit priest, author and editor at large at America .

Most popular

Your source for jobs, books, retreats, and much more.

The latest from america

Renewing faith, or losing it, in the time of COVID-19

- Copy Link URL Copied!

One roamed for hours through an oak preserve asking God to speak to her through the silence.

Another spent her days in meditation, using each exhale to send relief to her son, who had, by then, slipped out of consciousness. Not long before, a third woman had awakened in the middle of the night to what became a terrifying, recurring dream about descending into hell.

Each woman — members of three generations — went through a spiritual journey that had been sparked, sped up or heightened by the pandemic.

The last two years have transformed the stability of our families, our jobs and our collective understanding of science and sacrifice. But, for many of us, COVID-19’s reach also rewired something more elemental: our faith.

A Pew survey conducted early in the pandemic , found that nearly 3 in 10 Americans said their religious faith had become stronger since the coronavirus outbreak.

For others, this time has fundamentally changed their place within their religious traditions or led them to question long-held beliefs altogether — processes of introspection and transfiguration that can be, at once, painful and deeply fruitful.

“Suffering,” one of the women said, “sometimes forces us to look at the gold mine we’re sitting on.”

During the first fall of the pandemic, as she was clawing her way through a blinding depression, Esther Loewen told her wife, Paige, something she’d long feared would end both her marriage and her career as a Seventh-Day Adventist pastor.

“I’m afraid I might be trans.”

They sobbed and hugged and Paige made a promise: “I’m not going anywhere.”

A few months later, Loewen emailed her mother to explain that the person she’d long thought of as her eldest son was, in fact, her daughter. Her new name was Esther Elizabeth.

The revelation was hard for her mother. But Loewen, now 40, said her mother has come far in a short time, switching from using her deadname to “Elle,” a short version of her new middle name. Next, Loewen and her wife told their two sons, then 9 and 6, who quickly settled on a nickname of their own: Mapa.

In many ways, she said, the pandemic shutdowns provided the framework she needed to come out. For the first time ever, she was isolated from the social pressures and fears that had prevented her from transitioning. From her home in Redlands, she connected with other transgender Christians in Zoom support groups, which provided some relief from the bone-deep exhaustion that had come with pastoring a congregation with split views on masking and other COVID-19 safety measures.

Loewen knew her denomination had a longstanding record of barring LGBTQ people from church leadership, but because she was preaching remotely at the time, she’d felt comfortable to begin growing out her hair, keeping her beard closely cropped and painting her toenails. But she hadn’t yet decided whether to take hormones.

Before she took that step, she wanted to hear a blessing from God — and it finally came in January 2021 while at a retreat for church leaders at an oak preserve in Yucaipa.

During several hours of solitude, she prayed — “What do you want to tell me today?” — then she rounded a corner and saw hundreds of monarch butterflies. Like many trans people, she sees the caterpillar-to-butterfly transition as a beautiful analogy and, in that moment, she burst into laughter and then tears.

“It shifted from being like, ‘Can I do this?’” she said, “to ‘I have to do this in order to be faithful to God.’”

It felt just as clear as the calling, years earlier, to a life of ministry — a vocation born out of the faith she’d clung to as a teenager after surviving a house fire that killed her younger brother. It was a job she loved dearly, but also one that often made her think about privacy and secrecy.

“Don’t put your trash in the can out front,” an older pastor once had advised her, explaining that church members had interrogated him after finding an empty carton of ice cream, which would be off limits to the strictest Adventists, who are vegan.

She wouldn’t lie outright, but Loewen decided that church members didn’t need to know everything about her private life, including the time she wrote a letter to a friend, who is a lesbian, telling her she was loved by God exactly as she was and that the church was wrong on this issue.

She never dared say such a thing publicly, a reality that made her feel complicit then and guilty now. She sometimes thinks about times she sat around boardroom tables, listening to church leaders say hurtful, exclusionary things and didn’t speak up. And yet, she tries to welcome God’s grace, understanding that deep down, even then, she knew she was trans.

Last summer, as her depression deepened, she sat down with fellow church leaders and told them she was trans. She desperately hoped she could keep her job, she told them, suggesting they move her to a church in a more liberal area. The leaders handled the situation about as generously as they could have given church rules, she said, but it was clear she had to resign.

It was one of the heaviest losses of her life, she said, but still she feels closer to God than ever.

On a recent afternoon, Loewen, who is studying to become a therapist, picked up her younger son from school and took him to a park. A little girl on the swing next to him looked over at Loewen and then turned to her grandmother.

“What’s wrong with that lady?”

Her son turned confidently toward the girl.

“She’s transgender and she’s my Mapa.”

The ‘exvangelical’

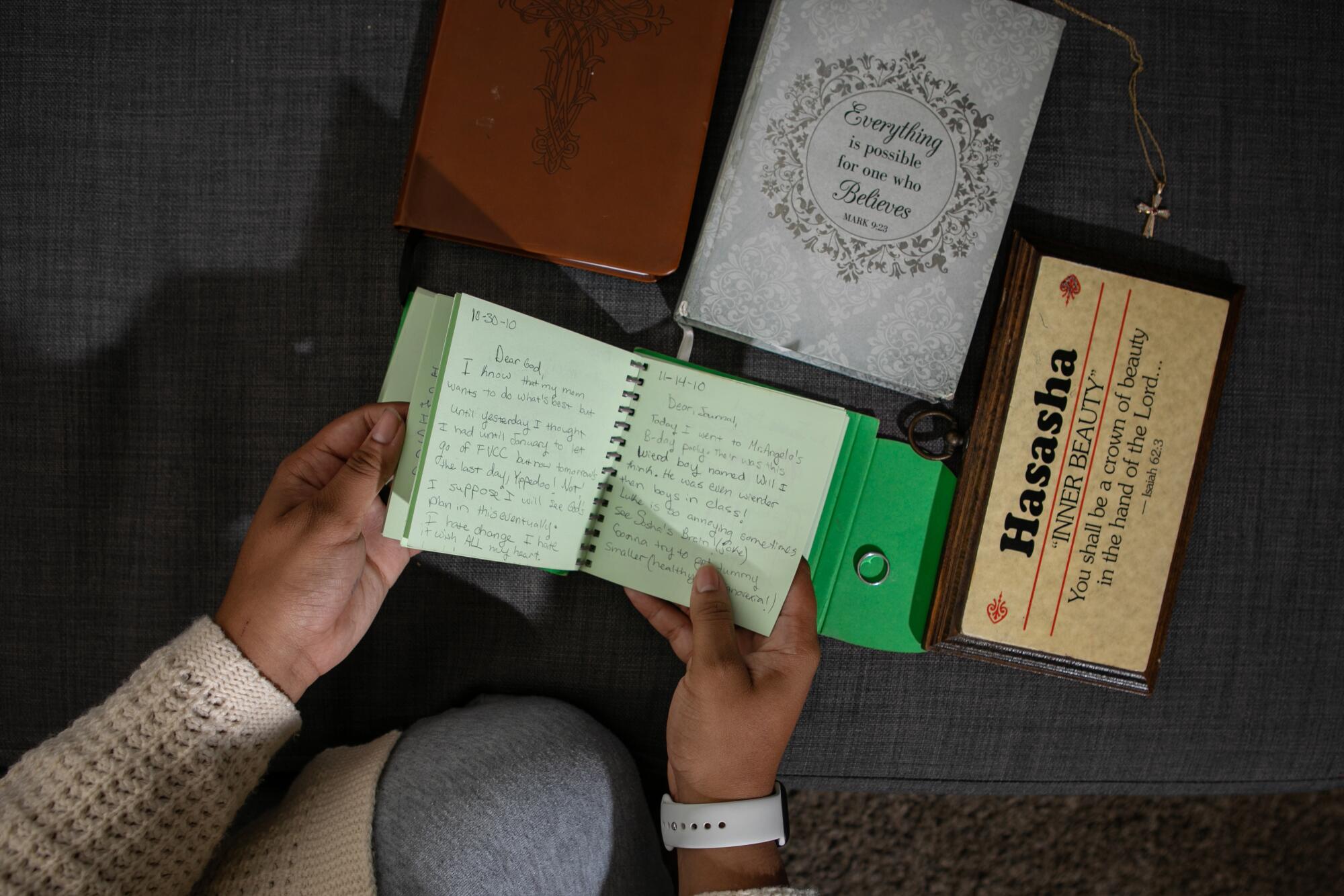

One day, when she was 9, Hasasha Hasulube-George recalls sitting on her bed sobbing.

“I’m such a bad girl,” she’d written in her journal.

She can’t remember what she got in trouble for that day — forgetting to clean her room, perhaps. But she vividly recalls her mother assuring her that if she asked Jesus into her heart, he would help her. So she prayed and relief washed over her.

By 12, she had pored through the Bible and soon after she read “I Kissed Dating Goodbye,” a purity culture classic during the early aughts. She proudly wore a silver promise ring inscribed with “True Love Waits” and woke up early on schooldays to pray.

And yet, a countervailing force buffeted her spiritual life: a dawning awareness that her family’s racial identity — her father is Black, her mother white — set them apart from the rest of their worship community in suburban Chicago.

Hasulube-George, now 24, recalls a church picnic where members of their congregation repeatedly told her brothers to only take what they could eat and not go back for seconds. They said nothing to the other teenagers in line, who were white.

So often, she said, conversations about race in white, evangelical circles — when they happened at all — quickly pivoted to the same line: “One day we’ll all go to Heaven and color will not matter.”

Still, she found deep community among fellow believers. When she thought about her few friends who weren’t Christians, it filled her with dread. What if she never tried to convert them and they died? Going to hell, she’d learned, was like getting stuck in a dark cave, separated from God for eternity and surrounded by deafening silence.

It was that same image that had haunted her dreams during the first summer of the pandemic.

By then, her then-fiancé, Hunter George, whom she’d met in college in Indiana, had been laid off from his job at a nonprofit and the cleaning job she had lined up after graduation fell through. The couple moved into Hunter’s parents’ basement in Rochester, N.Y.

She could almost always hear Fox News on the TV upstairs, with rotating headlines about the impending presidential election and mask mandates, or talking heads framing the social justice protests after the killings of Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor and George Floyd only in the context of property damage. Family members sent her and Hunter, who is white, emails suggesting that Black Lives Matter was against God and Trump was ordained by the Lord.

That’s when the nightmares started.

Like Arbery, who was shot to death by a white man while out for a jog, in her dreams Hasulube-George would be running when someone, often a neighbor, would shoot her dead. She’d then descend into the quiet-cave version of hell and be trapped there until she woke up in a panic.

She told Hunter she needed to get rid of her Bible. She couldn’t stop thinking about verses she’d underlined years earlier that she now felt condemned by. He understood.

In the weeks that followed, she remembers sitting on Zoom calls for Christian premarital counseling with a longtime mentor and thinking it felt like a farce. She and Hunter were actively trying to get pregnant, but she knew she couldn’t be upfront about that. She was trying to hold onto the final shreds of her faith until her wedding day in September 2020.

“My farewell party to my old life,” she came to think of it.

Soon after, she started having conversations, sometimes painful ones, with friends and family about her decision. A verse she’d once memorized — “ Children, obey your parents in the Lord” — now felt like a dagger.

Her mother initially responded with deep fear, she said, but time has softened the situation.

Since moving to North Hollywood last summer, the couple has continued to deconstruct their faiths. Hunter has vowed off organized religion and she has begun researching African spiritualism, specifically traditions from her father’s native Uganda.

She misses the structure her faith offered — for years, she relied on prayer as a tool to regulate her anxiety — but she has, again, found community in an online book club for fellow “exvangelicals.”

While she thinks she probably would have left her faith eventually, she said that watching the trifecta of pandemic-era scenarios play out in 2020 — the “don’t-wear-a-mask-God-will-protect-you” comments, the evangelical fervor for Trump and the response she saw from many Christians during the social justice protests — both crystalized and sped up her decision.

“That pushed me to decide, ‘I’m done.’”

The religious studies professor

Fran Grace clearly remembers the origin point of a twisting spiritual pathway that has helped guide her through the pandemic.

It was four decades ago and her high school English teacher was reading aloud from “The Scarlet Letter.” Only half-listening to Nathaniel Hawthorne’s tale of sin and repentance, she saw a pillar of light slice down, as if piercing through the ceiling, and felt as if she melted into the incandescence.

She interpreted it, at first, as a sign that something infinitely loving existed inside of her. But the revelation calcified into fear after her mother took her to see the pastor of a small Protestant church in her Florida town.

“You’ve got the devil inside you, young lady,” he proclaimed.

Now, further along in a journey that has included joining and leaving a fundamentalist Christian church, divorcing her husband, falling in love with a woman for the first time, drinking herself to near-death, finding sobriety and traveling to study world religions, Grace — a professor of religious studies at the University of Redlands — looks back fondly on that day in high school as the start of a lifelong quest that has buoyed her during the hardest times in her life.

At the tail end of last summer, Peter Boyko — her partner Diane Eller-Boyko’s son, whom she’d come to think of as her own — was hospitalized with COVID-19. Before long, the 29-year-old father of three was struggling to breathe.

Restricted from frequent visits, Grace and Eller-Boyko, who both follow the Sufi path, dug into spiritual tools they’d long relied on: meditation, dream work and paying attention to small signs.

Soon after Peter died, a letter addressed to him showed up at the couple’s home. The note from a children’s charity included a line about accepting people just as they are — a trait that was exceptionally true of Peter. It was a hint, Grace believed, from the inner world.

She felt more tuned into the kindness of others, often reflecting on the proverb about how suffering often points us to the goldmine beneath us. And as the pandemic lingers, she has tried to help others find that spiritual gold.

One Wednesday in December, Grace, 57, sat cross-legged in front of a camera inside the Meditation Room, an airy, carpeted space adjacent to her office at the University of Redlands.

A showcase for compelling storytelling from the Los Angeles Times.

For years, Grace has led free, weekly meditation sessions for students and other members of the community and although she’d returned in person by December, most of the attendees were still joining virtually. One by one, their smiling faces popped up in small squares as they joined from San Diego, Tucson, Canada.

Grace asked everyone to close their eyes.

“Relax, relax, relax,” she guided them.

Sense your right leg, she said, and then your left. Let your belly fall open and relax the muscles in your throat. Open your heart and offer yourself in service to others. Think of a stranger and send them love.

Later, they went around the virtual circle, sharing about their weeks and whom they had selected as their “stranger” while meditating.

A 91-year-old from San Diego had thought of the volunteer who drove her to a dentist appointment a few days earlier. An Iowa State University student pictured the cafeteria employee who handed her ice cream on her birthday. A Presbyterian minister recalled a man on Death Row at San Quentin who had started as a pen pal and became a close friend ; during the meditation, the minister said, she had prayed for the women he killed.

“Wow,” Grace whispered.

When it was his turn to share, a man from British Columbia, who was sitting cross-legged on his floor, told the group that his father had died a week earlier. He began to cry, resting his forehead on the ground.

Grace closed her eyes. As she inhaled, she focused on breathing in his suffering. With her exhale, she sent out hope.

More to Read

Young Latines are leaving organized religion. This divided family is learning to cope

April 30, 2024

Letters to the Editor: Losing your religion could be the start of a new search for faith

March 27, 2024

In ‘The Exvangelicals,’ Sarah McCammon tells the tale of losing her religion

March 20, 2024

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

Marisa Gerber is an enterprise reporter at the Los Angeles Times. A finalist for the Livingston Award, she joined The Times in 2012.

More Column One Storytelling

The desperate hours: a pro baseball pitcher’s fentanyl overdose

June 27, 2024

He crossed the Atlantic solo in a boat he built himself

June 26, 2024

World & Nation

She sang for ‘El Chapo.’ Now the cartel kingpin’s lawyer wants to be a ranchera star

June 20, 2024

A Ukrainian ‘King Lear’ comes to Shakespeare’s hometown. Its actors know true tragedy

June 19, 2024

A draft resister, a judge and the moment that still binds them after 54 years

June 14, 2024

Can money conquer death? How wealthy people are trying to live forever

June 4, 2024

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Elsevier - PMC COVID-19 Collection

Faith and science mindsets as predictors of COVID-19 concern: A three-wave longitudinal study ☆

Kathryn a. johnson.

a Arizona State University, USA

Amanda N. Baraldi

b Oklahoma State University, USA

Jordan W. Moon

Morris a. okun, adam b. cohen, associated data.

The COVID-19 pandemic allowed for a naturalistic, longitudinal investigation of the relationship between faith and science mindsets and concern about COVID-19. Our goal was to examine two possible directional relationships: (Model 1) COVID-19 concern ➔ disease avoidance and self-protection motivations ➔ science and faith mindsets versus (Model 2) science and faith mindsets ➔ COVID-19 concern. We surveyed 858 Mechanical Turk workers in three waves of a study conducted in March, April, and June 2020. We found that science mindsets increased whereas faith mindsets decreased (regardless of religious type) during the early months of the pandemic. Further, bivariate correlations and autoregressive cross-lagged analyses indicated that science mindset was positive predictor of COVID-19 concern, in support of Model 2. Faith mindset was not associated with COVID-19 concern. However, faith mindset was a negative predictor of science mindset. We discuss the need for more research regarding the influence of science and faith mindsets as well as the societal consequences of the pandemic.

1. Introduction

In the early months of 2020 and beyond, people's lives around the world were changed due to the spread of a novel coronavirus (SARS-COV-2) and the disease it causes (COVID-19). Arguably the most significant global health crisis in the past century, the virus had spread to every continent by June 2020, with over 9 million cases and 400,000 deaths worldwide. In the U.S. alone, COVID-19 had caused economic hardship, stressed supply chains, exacerbated levels of depression, heightened the anxiety of individuals already experiencing poor physical health, and led to the death of over 100,000 individuals. Historically, the uncertainty, danger, and existential crises associated with non-normative events of this magnitude have compelled people to try to make sense of, and cope with, their circumstances—often turning to natural resources such as science and/or supernatural resources such as religion ( Legare, Evans, Rosengren, & Harris, 2012 ; Legare & Gelman, 2008 ; Rutjens & Preston, 2020 ; Sibley & Bulbulia, 2012 ). In the present research, we conducted a longitudinal investigation of the potential causal relationships between science and faith mindsets and COVID-19 concern in a sample of individuals living in the U.S. during the early months of the pandemic.

There has been considerable interest in contrasting the characteristics, psychological profiles, and associated outcomes of reliance on science and religion in human experience. Science and religion are both multi-dimensional constructs with similar features such as their own vocabulary, orienting behaviors, norms, values, communities, and practices. However, at their respective cores, science and religion are two different approaches to making sense of and responding to events in the world ( Murphy, 2007 ). The global beliefs ( Park, 2005 ), knowledge networks ( Murphy, 2007 ), worldviews (Johnson, Hill, & Cohen, 2011), or mindsets associated with science and religion are critical for meaning-making as people perceive, interpret, navigate, and respond to life events and environmental stressors. Although religious groups can serve as rich sources of social support in times of crisis, in the present research, we focused on religious beliefs— a religious mindset—in comparison with a scientific mindset. Henceforth, we refer to the religious mindset as “faith” or a “faith mindset” to emphasize our focus on beliefs rather than religion more broadly construed.

In the present research, we conducted a longitudinal, quasi-experimental study during the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic in the U.S., focusing on the mindsets of science and faith. Our goal was to investigate whether COVID-19 concern shapes science and faith mindsets—mediated by disease avoidance and self-protection motivations; or, instead, whether science and faith mindsets influence the degree of COVID-19 concern. (The response to COVID-19 quickly became politicized in the U.S. Therefore, we control for political leanings in our analyses.)

1.1. COVID-19 concern as an influence on science and faith mindsets

As belief systems or mindsets, science and faith each have core tenets. The faith mindset generally includes beliefs that God or other supernatural beings exist; that religious group teachings or sacred writings are authoritative; and that God can provide comfort, protection, or help in meeting the challenges of life. The science mindset includes beliefs that logic must be used to generate testable hypotheses; empirical evidence is imperative for understanding; natural events can (eventually) be accurately explained and predicted by the community of scientists; and scientific knowledge is useful (or ideal) in addressing life's challenges.

However, science and faith—and the reliance on science and faith mindsets—have both been subject to change and reconceptualization and, at the cultural level, those changes often co-occur ( Barbour, 1998 ; Kuhn, 1996 ; Wootton, 2016 ). At the individual level, many factors, including environmental stressors and the challenges a person faces, may also bring about personal change in reliance on science and/or faith ( Farias, Newheiser, Kahane, & de Toledo, 2013 ; Jong, Halberstadt, & Bluemke, 2012 ; Lewandowsky & Oberauer, 2016 ; Rutjens, van der Pligt, & van Harreveld, 2010 ; Sinatra, Kienhues, & Hofer, 2014 ; Sinatra, Southerland, McConaughy, & Demastes, 2003 ). We expected that one such stressor would be the COVID-19 pandemic. Indeed, pathogens have presented one of the most pressing ecological threats to humankind, and SARS-CoV-2, and the disease it causes (COVID-19), is no different.

In the present research, we were primarily interested in whether COVID-19 concerns affect disease avoidance and self-protection motivations, which in turn, influence changes in individuals' reliance on science and faith mindsets. A large body of research has shown that diverse motivational systems (e.g., self-protection, disease avoidance, coalition formation, status-seeking, mate acquisition, and parenting) affect a swath of cognitive process, including what people attend to, how they reason, and their social perceptions ( Kenrick, Griskevicius, Neuberg, & Schaller, 2010 ). These fundamental motives are theorized to be distinct systems designed to promote behavior that solves adaptive problems. For example, when motivated by self-protection, people become wary of outgroups perceived as dangerous, whereas people who are motivated to find a romantic partner focus more on others' attractiveness and, at least for men, become more risk-prone ( Griskevicius, Goldstein, Mortensen, Cialdini, & Kenrick, 2006 ). In the present research, we consider the fundamental motivations of disease avoidance and self-protection to explain why COVID-19 concern, specifically, might lead to an increase in reliance on science or a faith mindset.

1.1.1. Disease avoidance

We expected that high levels of concern regarding COVID-19 would increase disease avoidance motives (see Makhanova & Shepherd, 2020 ). Pathogen prevalence and the motivation to avoid disease are often associated with traditionalist thinking, including conservativism and ingroup-oriented psychology ( Boyer, Firat, & van Leeuwen, 2015 ; McCann, 1999 ), and past research has linked the threat of disease to shifts in religion, as well as personality and values ( Fincher, Thornhill, Murray, & Schaller, 2008 ; Gelfand et al., 2011 ; Schaller & Murray, 2008 ; Varnum & Grossmann, 2016 ). High pathogen levels have also been linked with religiosity at the country level ( Fincher & Thornhill, 2012 ). Additionally, many of the rituals associated with religion promote cleanliness, such as emphases on health ( Reynolds & Tanner, 1995 ), ritual washings, and safety-minded food restrictions ( Johnson, White, Boyd, & Cohen, 2011 ). These rituals (e.g., hand washing) might carry over to better health practices.

However, there are reasons to think people living in Western cultures (such as the U.S.) might turn to science instead of faith when motived by disease avoidance. First, some religious practices actually increase the risk of disease. For instance, communal cups and certain religious rituals (e.g., touching surfaces, hymn books, etc., in common areas) may expose people to higher pathogen levels ( Reynolds & Tanner, 1995 ). To the extent that people intuit these dangers, they may avoid religious gatherings, and their faith may deteriorate ( Exline et al., 2020 ). Second, given the enormous impact COVID-19 has had on daily life, we expected to find that people were more likely motivated to seek medically accurate information and look to science to develop technologies, treatments, preventative health practices, or vaccines ( Murray, 2014 )—resources which would not necessarily be available from sacred texts or religious engagement. Thus, a hypothesized mediated pathway from COVID-19 concern to disease motivation to reliance on a science mindset is shown in the upper half of Fig. 1 .

Hypothesized model of changes in science and faith mindsets as outcomes of COVID-19 concern.

Note: Positive sign (+) indicates a hypothesized positive association. Correlated residuals are included because it is expected that factors outside of the model would also contribute to shared variation between disease avoidance and self-protection and between science and faith. We had no a priori hypothesis regarding the strength and direction of the correlated residuals between science and faith. In all analyses, we control for age, sex, and political conservatism.

1.1.2. Self-protection

In addition to the motivation to avoid germs, molds, contagion, and natural pollutants from contact with objects, humans possess suites of adaptations known as the “behavioral immune system,” which facilitates the avoidance of people as potential sources of pathogens ( Schaller & Park, 2011 ). Notably, disease avoidance and self-protection motivational systems are distinct (i.e., they use distinct inputs, are assessed differently, and promote distinct behavioral patterns; Neuberg, Kenrick, & Schaller, 2010 ). Therefore, in addition to an increase in disease avoidance motives, we also expected levels of self-protection to increase during the pandemic as a result of a more zero-sum psychology ( Van Bavel et al., 2020 ), perceiving other people to be potential carriers of the virus as well as competitors for resources ( Olivera-La Rosa, Chuquichambi, & Ingram, 2020 ).

We reasoned that self-protection motives would be especially likely to prompt a faith mindset. Such a reaction might reflect the fact that, when threatened, people become especially attuned to group membership ( Boyer et al., 2015 ). Indeed, people are more likely to form coalitions when mortality is made salient ( Wisman & Koole, 2003 ). Given the daily reports of worldwide deaths, we expected that COVID19 concern would increase self-protection motives and, in turn, increase seeking social support from familiar, trusted groups as well as via faith in God and prayer. The hypothesized mediated pathway from COVID-19 concern to self-protection motivation to faith is shown in the lower half of Fig. 1 .

In sum, we expected that the circumstances of COVID-19 would lead people to increase both reliance on a science and a faith mindset to provide different but complementary benefits. For example, science provides epistemological value, practical solutions for treating disease, and people may be particularly motivated to rely on science to regain a sense of control ( Rutjens, Van Harreveld, Van Der Pligt, Kreemers, & Noordewier, 2013 ) as they seek to avoid disease; whereas faith can provide a sense of comfort, meaning, and hope in times of crisis ( Laurin, Schumann, & Holmes, 2014 ; Pargament, Magyar-Russell, & Murray-Swank, 2005 ; Pargament, Smith, Koenig, & Perez, 1998 ).

1.2. Alternative model: science and faith mindsets as interpretive frameworks

However, it is possible that an individual's tendency to rely on science and faith might change very little, even in the face of an ecological crisis such as the COVID-19 pandemic. Indeed, an individual's worldview may be firmly entrenched and resistant to change. For instance, Lewandowsky and Oberauer (2016) found that many people reject scientific findings despite educated warnings of climate change, particularly if they viewed these findings as conflicting with their religious worldview. Likewise, despite repeated findings that religious faith is associated with better health and well-being ( McCullough, Hoyt, Larson, Koenig, & Thoresen, 2000 ), many people reject theism.

Instead, science and faith may function as meaning-making systems or interpretative frameworks in thinking about and making sense of the pandemic. Meaning-making has been conceptualized as a psychological need “to perceive events through a prism of mental representations of expected relations that organizes … perceptions of the world” ( Heine, Proulx, & Vohs, 2006 ). In that sense, meaning-making refers to the cognitive process of restoring global meaning—the coherence of one's beliefs and goals and the subjective sense of satisfaction that life is at least headed in the right direction ( Park, 2005 ). If people employ science or faith to understand, learn about, and interpret life experiences, then science or faith mindsets may, instead, influence individuals' thoughts, feelings, and attitudes about COVID-19.

Thus, the alternative model of science and faith providing coherent frameworks for making sense of the COVID-19 crisis would predict that reliance on science (i.e., the belief that science is the best source of knowledge and that the science mindset is capable of solving humankind's problems) would lead individuals to seek out scientific and statistical information (e.g., mortality rates, number of cases, potential treatments—or the lack thereof). Information about the pandemic was plentiful in the early months of the pandemic, and actively seeking this information could have elevated concerns and fears about infection, intubation, and death. The alternate pathway of science increasing COVID concern and, thereby, disease avoidance and self-protection, is shown in Fig. 2 .

Alternative model of science and faith as meaning-making systems.

Note: Positive sign (+) indicates a hypothesized positive association; a negative sign (−) indicates a hypothesized negative association. The bivariate relations between science and disease avoidance and between faith and self-protection was expected to be positive. However, these paths may be reduced to non-significance in the model after accounting for COVID-19 concern as a mediator; thus, no hypotheses for these paths were made.

In contrast, people with a robust faith or religious worldview may have had long-term experience with religious coping, trusting God to provide protection, comfort, and care ( Laurin et al., 2014 ; Pargament et al., 1998 ; Park, Cohen, & Herb, 1990 ). Indeed, monotheists are repeatedly instructed to trust in God and “fear not” in the scriptures. Thus, contrary to the predictions in our hypothesized model ( Fig. 1 ), faith may have mitigated concern about COVID-19, indirectly reducing disease avoidance and self-protection, as shown in Fig. 2 .

1.3. Science and faith mindsets

Research shows that some people see the belief systems of science and faith as conflicting domains, often in terms of an epistemological divide ( McPhetres, Jong, & Zuckerman, 2020 ; McPhetres & Nguyen, 2018 ; O'Brien & Noy, 2015 ). Consequently, much of the previous research has focused on investigating differences between science and faith in terms of cognitive style ( Farias et al., 2017 ; Gervais & Norenzayan, 2012 ; Pennycook, Cheyne, Seli, Koehler, & Fugelsang, 2012 ), differing knowledge structures ( Lewandowsky & Oberauer, 2016 ), or as hydraulic cognitive processes ( Preston & Epley, 2009 ).

However, science and faith mindsets do not necessarily conflict. People can and often do rely upon both religious and scientific beliefs ( Ecklund, Park, & Sorrell, 2011 ; Nelson, 2009 ; Pew Research Center, 2015a , Pew Research Center, 2015b ; Scheitle, 2011 ; Watts, Passmore, Jackson, Rzymski, & Dunbar, 2020 ). Indeed, until about the 16th century, science and faith were indistinguishable ( Barbour, 1998 ; Wootton, 2016 ). Today, people often utilize both systems to understand and deal with illness and death ( Clegg, Cui, Harris, & Corriveau, 2019 ; Cui et al., 2020 ; Davoodi et al., 2019 ; Legare & Gelman, 2008 ). Thus, in our hypothesized model, we expected both science and faith mindsets to increase, with science providing practical treatments and a sense of control; and faith providing a source of comfort and care.

2.1. Participants

We conducted a naturalistic study, surveying a panel of Amazon Mechanical Turk workers in the U.S., across three time periods, in March, April, and June 2020. We report all measures, manipulations (none), and exclusions below. Sample size was determined before data collection began.

2.1.1. Time 1

Participants at Time 1 (T1; March 15–29, 2020) were 858 MTurk workers recruited using Cloud Research ( Litman, Robinson, & Abbercock, 2017 ) (IRB # 00011534). All participants had completed one of the authors' studies during the past five years and had been informed that they might be invited to participate in subsequent studies. Participants at T1 were recruited over one week, as concern regarding COVID-19 was increasing daily, and the number of cases and deaths continued to rise. More detail regarding the data collection strategy is provided in the Supplemental Materials (Table S1).

There were 384 males and 474 females, M age = 44.84, SD = 13.72. There were 121 Atheists, 176 Agnostics, 177 Mainline Protestants, 150 Catholics, 124 Evangelicals, 91 Spiritual but not Religious, 13 Jews, and 6 Muslims. The percentages of participants who identified as spiritual or religious (66%) and non-religious (34%) in our study were similar to the percentages of these groups in the U.S. (77% religious, 23% non-religious; Pew Research Center, 2015a , Pew Research Center, 2015b ) but with somewhat more non-religious participants as is typical of the MTurk population ( Lewis, Djupe, Mockabee, & Su-Ya Wu, 2015 ). There were 79.7% Euro-Americans, 7.5% Blacks, 4.9% Asians, 4.8% Hispanics, and 3.1% of people reported multiple races/ethnicities.