Choose Your Test

Sat / act prep online guides and tips, to be or not to be: analyzing hamlet's soliloquy.

General Education

"To be, or not to be, that is the question."

It’s a line we’ve all heard at some point (and very likely quoted as a joke), but do you know where it comes from and the meaning behind the words? "To be or not to be" is actually the first line of a famous soliloquy from William Shakespeare’s play Hamle t .

In this comprehensive guide, we give you the full text of the Hamlet "To be or not to be" soliloquy and discuss everything there is to know about it, from what kinds of themes and literary devices it has to its cultural impact on society today.

Full Text: "To Be, or Not to Be, That Is the Question"

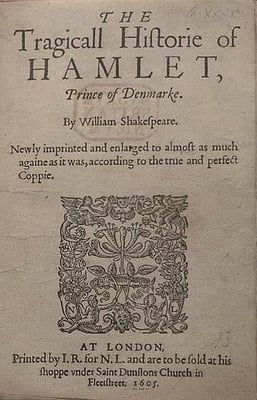

The famous "To be or not to be" soliloquy comes from William Shakespeare’s play Hamlet (written around 1601) and is spoken by the titular Prince Hamlet in Act 3, Scene 1. It is 35 lines long.

Here is the full text:

To be, or not to be, that is the question, Whether 'tis nobler in the mind to suffer The slings and arrows of outrageous fortune, Or to take arms against a sea of troubles, And by opposing end them? To die: to sleep; No more; and by a sleep to say we end The heart-ache and the thousand natural shocks That flesh is heir to, 'tis a consummation Devoutly to be wish'd. To die, to sleep; To sleep: perchance to dream: ay, there's the rub; For in that sleep of death what dreams may come When we have shuffled off this mortal coil, Must give us pause: there's the respect That makes calamity of so long life; For who would bear the whips and scorns of time, The oppressor's wrong, the proud man's contumely, The pangs of despised love, the law's delay, The insolence of office and the spurns That patient merit of the unworthy takes, When he himself might his quietus make With a bare bodkin? who would fardels bear, To grunt and sweat under a weary life, But that the dread of something after death, The undiscover'd country from whose bourn No traveller returns, puzzles the will And makes us rather bear those ills we have Than fly to others that we know not of? Thus conscience does make cowards of us all; And thus the native hue of resolution Is sicklied o'er with the pale cast of thought, And enterprises of great pith and moment With this regard their currents turn awry, And lose the name of action.—Soft you now! The fair Ophelia! Nymph, in thy orisons Be all my sins remember'd.

You can also view a contemporary English translation of the speech here .

"To Be or Not to Be": Meaning and Analysis

The "To be or not to be" soliloquy appears in Act 3, Scene 1 of Shakespeare’s Hamlet . In this scene, often called the "nunnery scene," Prince Hamlet thinks about life, death, and suicide. Specifically, he wonders whether it might be preferable to commit suicide to end one's suffering and to leave behind the pain and agony associated with living.

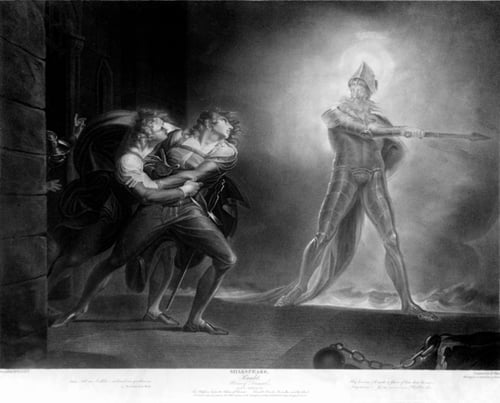

Though he believes he is alone when he speaks, King Claudius (his uncle) and Polonius (the king’s councilor) are both in hiding, eavesdropping.

The first line and the most famous of the soliloquy raises the overarching question of the speech: "To be, or not to be," that is, "To live, or to die."

Interestingly, Hamlet poses this as a question for all of humanity rather than for only himself. He begins by asking whether it is better to passively put up with life’s pains ("the slings and arrows") or actively end it via suicide ("take arms against a sea of troubles, / And by opposing end them?").

Hamlet initially argues that death would indeed be preferable : he compares the act of dying to a peaceful sleep: "And by a sleep to say we end / The heart-ache and the thousand natural shocks / That flesh is heir to."

However, he quickly changes his tune when he considers that nobody knows for sure what happens after death , namely whether there is an afterlife and whether this afterlife might be even worse than life. This realization is what ultimately gives Hamlet (and others, he reasons) "pause" when it comes to taking action (i.e., committing suicide).

In this sense, humans are so fearful of what comes after death and the possibility that it might be more miserable than life that they (including Hamlet) are rendered immobile.

Inspiration Behind Hamlet and "To Be or Not to Be"

Shakespeare wrote more than three dozen plays in his lifetime, including what is perhaps his most iconic, Hamlet . But where did the inspiration for this tragic, vengeful, melancholy play come from? Although nothing has been verified, rumors abound.

Some claim that the character of Hamlet was named after Shakespeare’s only son Hamnet , who died at age 11 only five years prior to his writing of Hamlet in 1601. If that's the case, the "To be or not to be" soliloquy, which explores themes of death and the afterlife, seems highly relevant to what was more than likely Shakespeare’s own mournful frame of mind at the time.

Others believe Shakespeare was inspired to explore graver, darker themes in his works due to the passing of his own father in 1601 , the same year he wrote Hamlet . This theory seems possible, considering that many of the plays Shakespeare wrote after Hamlet , such as Macbeth and Othello , adopted similarly dark themes.

Finally, some have suggested that Shakespeare was inspired to write Hamlet by the tensions that cropped up during the English Reformation , which raised questions as to whether the Catholics or Protestants held more "legitimate" beliefs (interestingly, Shakespeare intertwines both religions in the play).

These are the three central theories surrounding Shakespeare’s creation of Hamlet . While we can’t know for sure which, if any, are correct, evidently there are many possibilities — and just as likely many inspirations that led to his writing this remarkable play.

3 Critical Themes in "To Be or Not to Be"

- Doubt and uncertainty

- Life and death

Theme 1: Doubt and Uncertainty

Doubt and uncertainty play a huge role in Hamlet’s "To be or not to be" soliloquy. By this point in the play, we know that Hamlet has struggled to decide whether he should kill Claudius and avenge his father’s death .

Questions Hamlet asks both before and during this soliloquy are as follows:

- Was it really the ghost of his father he heard and saw?

- Was his father actually poisoned by Claudius?

- Should he kill Claudius?

- Should he kill himself?

- What are the consequences of killing Claudius? Of not killing him?

There are no clear answers to any of these questions, and he knows this. Hamlet is struck by indecisiveness, leading him to straddle the line between action and inaction.

It is this general feeling of doubt that also plagues his fears of the afterlife, which Hamlet speaks on at length in his "To be or not to be" soliloquy. The uncertainty of what comes after death is, to him, the main reason most people do not commit suicide; it’s also the reason Hamlet himself hesitates to kill himself and is inexplicably frozen in place .

Theme 2: Life and Death

As the opening line tells us, "To be or not to be" revolves around complex notions of life and death (and the afterlife).

Up until this point in the play, Hamlet has continued to debate with himself whether he should kill Claudius to avenge his father. He also wonders whether it might be preferable to kill himself — this would allow him to escape his own "sea of troubles" and the "slings and arrows" of life.

But like so many others, Hamlet fears the uncertainty dying brings and is tormented by the possibility of ending up in Hell —a place even more miserable than life. He is heavily plagued by this realization that the only way to find out if death is better than life is to go ahead and end it, a permanent decision one cannot take back.

Despite Hamlet's attempts to logically understand the world and death, there are some things he will simply never know until he himself dies, further fueling his ambivalence.

Theme 3: Madness

The entirety of Hamlet can be said to revolve around the theme of madness and whether Hamlet has been feigning madness or has truly gone mad (or both). Though the idea of madness doesn’t necessarily come to the forefront of "To be or not to be," it still plays a crucial role in how Hamlet behaves in this scene.

Before Hamlet begins his soliloquy, Claudius and Polonius are revealed to be hiding in an attempt to eavesdrop on Hamlet (and later Ophelia when she enters the scene). Now, what the audience doesn’t know is whether Hamlet knows he is being listened to .

If he is unaware, as most might assume he is, then we could view his "To be or not to be" soliloquy as the simple musings of a highly stressed-out, possibly "mad" man, who has no idea what to think anymore when it comes to life, death, and religion as a whole.

However, if we believe that Hamlet is aware he's being spied on, the soliloquy takes on an entirely new meaning: Hamlet could actually be feigning madness as he bemoans the burdens of life in an effort to perplex Claudius and Polonius and/or make them believe he is overwhelmed with grief for his recently deceased father.

Whatever the case, it’s clear that Hamlet is an intelligent man who is attempting to grapple with a difficult decision. Whether or not he is truly "mad" here or later in the play is up to you to decide!

4 Key Literary Devices in "To Be or Not to Be"

In the "To be or not to be" soliloquy, Shakespeare has Hamlet use a wide array of literary devices to bring more power, imagination, and emotion to the speech. Here, we look at some of the key devices used , how they’re being used, and what kinds of effects they have on the text.

#1: Metaphor

Shakespeare uses several metaphors in "To be or not to be," making it by far the most prominent literary device in the soliloquy. A metaphor is when a thing, person, place, or idea is compared to something else in non-literal terms, usually to create a poetic or rhetorical effect.

One of the first metaphors is in the line "to take arms against a sea of troubles," wherein this "sea of troubles" represents the agony of life, specifically Hamlet’s own struggles with life and death and his ambivalence toward seeking revenge. Hamlet’s "troubles" are so numerous and seemingly unending that they remind him of a vast body of water.

Another metaphor that comes later on in the soliloquy is this one: "The undiscover'd country from whose bourn / No traveller returns." Here, Hamlet is comparing the afterlife, or what happens after death, to an "undiscovered country" from which nobody comes back (meaning you can’t be resurrected once you’ve died).

This metaphor brings clarity to the fact that death truly is permanent and that nobody knows what, if anything, comes after life.

#2: Metonymy

A metonym is when an idea or thing is substituted with a related idea or thing (i.e., something that closely resembles the original idea). In "To be or not to be," Shakespeare uses the notion of sleep as a substitute for death when Hamlet says, "To die, to sleep."

Why isn’t this line just a regular metaphor? Because the act of sleeping looks very much like death. Think about it: we often describe death as an "eternal sleep" or "eternal slumber," right? Since the two concepts are closely related, this line is a metonym instead of a plain metaphor.

#3: Repetition

The phrase "to die, to sleep" is an example of repetition, as it appears once in line 5 and once in line 9 . Hearing this phrase twice emphasizes that Hamlet is really (albeit futilely) attempting to logically define death by comparing it to what we all superficially know it to be: a never-ending sleep.

This literary device also paves the way for Hamlet’s turn in his soliloquy, when he realizes that it’s actually better to compare death to dreaming because we don’t know what kind of afterlife (if any) there is.

#4: Anadiplosis

A far less common literary device, anadiplosis is when a word or phrase that comes at the end of a clause is repeated at the very beginning of the next clause.

In "To be or not to be," Hamlet uses this device when he proclaims, "To die, to sleep; / To sleep: perchance to dream." Here, the phrase "to sleep" comes at the end of one clause and at the start of the next clause.

The anadiplosis gives us a clear sense of connection between these two sentences . We know exactly what’s on Hamlet’s mind and how important this idea of "sleep" as "death" is in his speech and in his own analysis of what dying entails.

The Cultural Impact of "To Be or Not to Be"

The "To be or not to be" soliloquy in Shakespeare’s Hamlet is one of the most famous passages in English literature, and its opening line, "To be, or not to be, that is the question," is one of the most quoted lines in modern English .

Many who’ve never even read Hamlet (even though it’s said to be one of the greatest Shakespeare plays ) know about "To be or not to be." This is mainly due to the fact that the iconic line is so often quoted in other works of art and literature — even pop culture .

And it’s not just quoted, either; some people use it ironically or sarcastically .

For example, this Calvin and Hobbes comic from 1994 depicts a humorous use of the "To be or not to be" soliloquy by poking fun at its dreary, melodramatic nature.

Many movies and TV shows have references to "To be or not to be," too. In an episode of Sesame Street , famed British actor Patrick Stewart does a parodic version of the soliloquy ("B, or not a B") to teach kids the letter "B":

There’s also the 1942 movie (and its 1983 remake) To Be or Not to Be , a war comedy that makes several allusions to Shakespeare’s Hamlet . Here’s the trailer for the 1983 version:

Finally, here’s one AP English student’s original song version of "To be or not to be":

As you can see, over the more than four centuries since Hamlet first premiered, the "To be or not to be" soliloquy has truly made a name for itself and continues to play a big role in society.

Conclusion: The Legacy of Hamlet ’s "To Be or Not to Be"

William Shakespeare’s Hamlet is one of the most popular, well-known plays in the world. Its iconic "To be or not to be" soliloquy, spoken by the titular Hamlet in Scene 3, Act 1, has been analyzed for centuries and continues to intrigue scholars, students, and general readers alike.

The soliloquy is essentially all about life and death : "To be or not to be" means "To live or not to live" (or "To live or to die") . Hamlet discusses how painful and miserable human life is, and how death (specifically suicide) would be preferable, would it not be for the fearful uncertainty of what comes after death.

The soliloquy contains three main themes :

It also uses four unique literary devices :

- Anadiplosis

Even today, we can see evidence of the cultural impact of "To be or not to be," with its numerous references in movies, TV shows, music, books, and art. It truly has a life of its own!

What’s Next?

In order to analyze other texts or even other parts of Hamlet effectively, you'll need to be familiar with common poetic devices , literary devices , and literary elements .

What is iambic pentameter? Shakespeare often used it in his plays —including Hamlet . Learn all about this type of poetic rhythm here .

Need help understanding other famous works of literature? Then check out our expert guides to F. Scott Fitzgerald's The Great Gatsby , Arthur Miller's The Crucible , and quotations in Harper Lee's To Kill a Mockingbird .

Hannah received her MA in Japanese Studies from the University of Michigan and holds a bachelor's degree from the University of Southern California. From 2013 to 2015, she taught English in Japan via the JET Program. She is passionate about education, writing, and travel.

Ask a Question Below

Have any questions about this article or other topics? Ask below and we'll reply!

Improve With Our Famous Guides

- For All Students

The 5 Strategies You Must Be Using to Improve 160+ SAT Points

How to Get a Perfect 1600, by a Perfect Scorer

Series: How to Get 800 on Each SAT Section:

Score 800 on SAT Math

Score 800 on SAT Reading

Score 800 on SAT Writing

Series: How to Get to 600 on Each SAT Section:

Score 600 on SAT Math

Score 600 on SAT Reading

Score 600 on SAT Writing

Free Complete Official SAT Practice Tests

What SAT Target Score Should You Be Aiming For?

15 Strategies to Improve Your SAT Essay

The 5 Strategies You Must Be Using to Improve 4+ ACT Points

How to Get a Perfect 36 ACT, by a Perfect Scorer

Series: How to Get 36 on Each ACT Section:

36 on ACT English

36 on ACT Math

36 on ACT Reading

36 on ACT Science

Series: How to Get to 24 on Each ACT Section:

24 on ACT English

24 on ACT Math

24 on ACT Reading

24 on ACT Science

What ACT target score should you be aiming for?

ACT Vocabulary You Must Know

ACT Writing: 15 Tips to Raise Your Essay Score

How to Get Into Harvard and the Ivy League

How to Get a Perfect 4.0 GPA

How to Write an Amazing College Essay

What Exactly Are Colleges Looking For?

Is the ACT easier than the SAT? A Comprehensive Guide

Should you retake your SAT or ACT?

When should you take the SAT or ACT?

Stay Informed

Get the latest articles and test prep tips!

Looking for Graduate School Test Prep?

Check out our top-rated graduate blogs here:

GRE Online Prep Blog

GMAT Online Prep Blog

TOEFL Online Prep Blog

Holly R. "I am absolutely overjoyed and cannot thank you enough for helping me!”

Plot Your Novel -- Plot Your Scenes with John Claude Bemis is now open for enrollment. Space is strictly limited. For those interested, you are encouraged to learn more right away.

Written by Emily Harstone October 3rd, 2013

Writing Prompts: To Be or Not To Be

“To be or not be” is the world’s most famous soliloquy. It is act 3, scene 1 in Hamlet, and it is among the many lines from Shakespeare that are still commonly spoofed in current culture. At the end of this article I have included the entire text of the soliloquy.

Today’s prompt is a simple one, read the soliloquy, and then recreate it in a modern setting. I don’t mean that you should focus on modernizing every ’tis and Bodkin, instead you should focus on rephrasing and conveying the ideas. That leaves a lot of room for creative wiggle room.

Your re-writing of the famous scene could change it from a soliloquy into a conversation, an email, or a twitter rant, anything really. Depending on what you change, the setting to be the whole piece could become comedic instead of dramatic.

These are just ideas though. Have fun and be creative. See where this exercise takes you.

The soliloquy:

To be, or not to be, that is the question: Whether ’tis Nobler in the mind to suffer The Slings and Arrows of outrageous Fortune, Or to take Arms against a Sea of troubles, And by opposing end them: to die, to sleep No more; and by a sleep, to say we end The Heart-ache, and the thousand Natural shocks That Flesh is heir to? ‘Tis a consummation Devoutly to be wished. To die, to sleep, To sleep, perchance to Dream; Aye, there’s the rub, For in that sleep of death, what dreams may come, When we have shuffled off this mortal coil, Must give us pause. There’s the respect That makes Calamity of so long life: For who would bear the Whips and Scorns of time, The Oppressor’s wrong, the proud man’s Contumely, The pangs of despised Love, the Law’s delay, The insolence of Office, and the Spurns That patient merit of the unworthy takes, When he himself might his Quietus make With a bare Bodkin? Who would Fardels bear, To grunt and sweat under a weary life, But that the dread of something after death, The undiscovered Country, from whose bourn No Traveller returns, Puzzles the will, And makes us rather bear those ills we have, Than fly to others that we know not of. Thus Conscience does make Cowards of us all, And thus the Native hue of Resolution Is sicklied o’er, with the pale cast of Thought, And enterprises of great pitch and moment, With this regard their Currents turn awry , And lose the name of Action. Soft you now, The fair Ophelia? Nymph, in thy Orisons Be all my sins remembered.

We Send You Publishers Seeking Submissions.

Sign up for our free e-magazine and we will send you reviews of publishers seeking short stories, poetry, essays, and books.

Subscribe now and we'll send you a free copy of our book Submit, Publish, Repeat

Enter Your Email Address:

June 11, 2024

Free Talk: An Introduction to Publishing Your Writing in Literary Journals

You can download the slides here, and take a look at the sample submission tracker here. Shannan Mann is the Founding Editor of ONLY POEMS. She has been awarded or placed for the Palette Love and Eros Prize, Rattle Poetry Prize, and Auburn Witness Poetry Prize among others. Her poems appear in Poetry Daily, EPOCH,…

Available to watch right now, completely free.

June 4, 2024

Free Talk: How to Write Romance Novels Readers Love

July 1, 2024

35 Themed Submissions Calls and Contests for July 2024

These are themed calls and contests for fiction, nonfiction, and poetry. Some of the call themes are: seaside gothic; Halloween; black cats; false memories; madame, don’t forget your sword; mafia horror; mystery stories; cowboy up; demagogues; ghost stories; pirate horror; holidays as a parent. Zoetic Press: Non-Binary Review – False MemoriesThey want poetry, fiction,…

June 27, 2024

Antiphony: Now Seeking Poetry Submissions

A new publication seeking poetry, critical essays, interviews, and poetry manuscripts.

The Other Side of the Desk: Shannan Mann

An interview with the founding editor of ONLY POEMS.

We’re Not Robots: Why AI Chatbots Can’t Replace Good Writing

As a living human being with a mind and imagination all your own, you are able to create something no AI can create.

- Entire Site Manuscript Publishers Literary Journals Search

A little something about you, the author. Nothing lengthy, just an overview.

- 180 Literary Journals for Creative Writers

- 182 Short Fiction Publishers

- Authors Publish Magazine

- Back Issues

- Confirmation: The Authors Publish Introduction to Marketing Your Book

- Download “How to Publish Your Book!”

- Download Page: How to Market Your Novel on Facebook

- Download Page: Self-Publishing Success – 8 Case Studies

- Download Page: Submit, Publish, Repeat

- Download Page: Submit, Publish, Repeat –– 4th Edition

- Download Page: Submit, Publish, Repeat: 3rd Edition

- Download Page: The 2015 Guide to Manuscript Publishers

- Download Page: The Unofficial Goodreads Author Guide

- Download: “The Authors Publish Compendium of Writing Prompts”

- Download: Get Your Book Published

- Download: The Authors Publish Compendium of Writing Prompts

- Emily Harstone

- Free Book: 8 Ways Through Publisher’s Block

- Free Books from Authors Publish Press

- Free Lecture & Discussion: Senior Book Publicist Isabella Nugent on Setting Yourself Up for Success

- Free Lecture from Kim Addonizio: Make a Book – Shaping Your Poetry Manuscript

- Free Lecture: Everyday Activities to Improve Your Writing

- Free Lecture: How to Publish Your Writing in Literary Journals

- Free Lecture: How to Write a Book that Keeps Readers Up All Night

- Free Lecture: How to Write Layered Stories that Keep Readers Glued to the Page with Nev March

- Free Lecture: Introduction to Diversity Reading for Authors

- Free Lecture: Passion, Professionalized – How to Build an Authentic & Thriving Writing Career

- Free Lecture: The Art of Book Reviewing — How to Write & Get Paid for Book Reviews

- Free Lecture: The Art of Fresh Imagery in Poetry

- Free Lecture: The Art of the Zuihitsu with Eugenia Leigh

- Free Lecture: The Magic of Productivity – How to Write Effortlessly and Quickly

- Free Lecture: Write Like a Wild Thing – 6 Lessons on Crafting an Unforgettable Story

- Free Lectures from Award Winning Authors & Publishing Professionals

- How to Promote Your Book

- How to Revise Your Writing for Publication, While Honoring Your Vision as an Author

- How to Write a Dynamic Act One ‒ A Guide for Novelists

- How to Write With Surprising Perspectives — What Dutch Masters Can Teach Us About Telling Stories

- Lecture: How to Keep Readers Glued to Every Page of Your Book with Microplotting

- Lecture: How to Publish Your Creative Writing in Literary Journals

- Lecture: How to Write a Memoir that Wins Over Readers and Publishers

- Lecture: How to Write Opening Pages that Hook Readers and Publishers

- Lecture: How to Write Romance Novels Readers Will Love

- Lecture: The Art of Collaboration With Vi Khi Nao

- Lecture: The Art of Poetic Efficiency – Strategies for Elevating Your Prose and Poetry

- Lecture: The First Twenty Pages

- Lecture: The Magic of Metaphor – How to Create Vivid Metaphors that Can Transform Your Writing

- Lecture: Tips and Tricks for Revising Your Manuscript to Make It Shine

- Lecture: Writing from Dreams

- Lecture: Writing to Save the World with Danté Stewart

- New Front Page

- Now Available: The 2017 Guide to Manuscript Publishers

- Now Available: The 2018 Guide to Manuscript Publishers

- Office Hours With Ella Peary

- Poem to Book: The Poet’s Path to a Traditional Publisher

- Privacy Policy

- Random Prompt

- River Woman, River Demon Pre-Order Event: Discussing Book Marketing With Jennifer Givhan and Her Book Publicist, Isabella Nugent

- Submit to Authors Publish Magazine

- Submit, Publish, Repeat: 2023 Edition

- Taming the Wild Beast: Making Inspiration Work for You

- Test Live Stream

- Thank You for Attending the Lecture

- Thank You For Subscribing

- The 2018 Guide to Manuscript Publishers — 172 Traditional Book Publishers

- The 2019 Guide to Manuscript Publishers – 178 Traditional Book Publishers

- The 2023 Guide to Manuscript Publishers – 280 Traditional Book Publishers

- The Art of Narrative Structures

- The Authors Publish Guide to Children’s and Young Adult Publishing – Second Edition

- The Authors Publish Guide to Manuscript Submission

- The Authors Publish Guide to Manuscript Submission (Fifth Edition)

- The Authors Publish Guide to Memoir Writing and Publishing

- The Authors Publish Quick-Start Guide to Flash Fiction

- The First Twenty Pages

- The Six Month Novel Writing Plan: Download Page

- The Writer’s Workshop – Office Hours with Emily Harstone

- How to Add a Document to a Discussion

- How to Mark All of the Lessons in a Thinkific Course “Complete”

- How to Navigate a Thinkific Course

- How to Start a Discussion on Thinkific

- How to Upload an Assignment in Thinkific

- We Help Authors Find the Right Publisher for Their Books

- Welcome to Authors Publish: We Help Writers Get Published

- Work With Us

- Writing from the Upside Down – Stranger Things, Duende, & Subverting Expectations

- Your Book On The Kindle!

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- February 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- December 2014

- November 2014

- October 2014

- September 2014

- August 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- November 2013

- October 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- Announcement 1

- Calls for Submissions 93

- Case Studies 9

- Completely ready unscheduled article 3

- Issue Two Hundred Twenty Two 1

- Issue Eight 4

- Issue Eighteen 5

- Issue Eighty 6

- Issue Eighty-Eight 6

- Issue Eighty-Five 6

- Issue Eighty-Four 5

- Issue Eighty-Nine 7

- Issue Eighty-One 6

- Issue Eighty-Seven 4

- Issue Eighty-Six 6

- Issue Eighty-Three 5

- Issue Eighty-Two 4

- Issue Eleven 5

- Issue Fifteen 4

- Issue Fifty 6

- Issue Fifty Eight 6

- Issue Fifty Five 6

- Issue Fifty Four 5

- Issue Fifty Nine 5

- Issue Fifty One 6

- Issue Fifty Seven 5

- Issue Fifty Six 6

- Issue Fifty Three 4

- Issue Fifty Two 6

- Issue Five 4

- Issue Five Hundred 3

- Issue Five Hundred Eight 3

- Issue Five Hundred Eighteen 5

- Issue Five Hundred Eleven 5

- Issue Five Hundred Fifteen 4

- Issue Five Hundred Fifty 4

- Issue Five Hundred Fifty Eight 4

- Issue Five Hundred Fifty Five 4

- Issue Five Hundred Fifty Four 5

- Issue Five Hundred Fifty Nine 4

- Issue Five Hundred Fifty One 4

- Issue Five Hundred Fifty Seven 4

- Issue Five Hundred Fifty Six 3

- Issue Five Hundred Fifty Three 4

- Issue Five Hundred Fifty Two 5

- Issue Five Hundred Five 4

- Issue Five Hundred Forty 5

- Issue Five Hundred Forty Eight 4

- Issue Five Hundred Forty Five 4

- Issue Five Hundred Forty Four 5

- Issue Five Hundred Forty Nine 4

- Issue Five Hundred Forty One 4

- Issue Five Hundred Forty Seven 4

- Issue Five Hundred Forty Six 4

- Issue Five Hundred Forty Three 3

- Issue Five Hundred Forty Two 3

- Issue Five Hundred Four 4

- Issue Five Hundred Fourteen 6

- Issue Five Hundred Nine 4

- Issue Five Hundred Nineteen 4

- Issue Five Hundred One 5

- Issue Five Hundred Seven 4

- Issue Five Hundred Seventeen 3

- Issue Five Hundred Seventy 4

- Issue Five Hundred Seventy Eight 3

- Issue Five Hundred Seventy Five 4

- Issue Five Hundred Seventy Four 4

- Issue Five Hundred Seventy One 4

- Issue Five Hundred Seventy Seven 4

- Issue Five Hundred Seventy Six 3

- Issue Five Hundred Seventy Three 3

- Issue Five Hundred Seventy Two 3

- Issue Five Hundred Six 4

- Issue Five Hundred Sixteen 5

- Issue Five Hundred Sixty 2

- Issue Five Hundred Sixty Eight 4

- Issue Five Hundred Sixty Five 3

- Issue Five Hundred Sixty Four 4

- Issue Five Hundred Sixty Nine 4

- Issue Five Hundred Sixty One 3

- Issue Five Hundred Sixty Seven 4

- Issue Five Hundred Sixty Six 4

- Issue Five Hundred Sixty Three 4

- Issue Five Hundred Sixty Two 4

- Issue Five Hundred Ten 3

- Issue Five Hundred Thirteen 3

- Issue Five Hundred Thirty 4

- Issue Five Hundred Thirty Eight 4

- Issue Five Hundred Thirty Five 3

- Issue Five Hundred Thirty Four 3

- Issue Five Hundred Thirty Nine 3

- Issue Five Hundred Thirty One 4

- Issue Five Hundred Thirty Seven 4

- Issue Five Hundred Thirty Six 4

- Issue Five Hundred Thirty Three 4

- Issue Five Hundred Thirty Two 4

- Issue Five Hundred Three 4

- Issue Five Hundred Twelve 3

- Issue Five Hundred Twenty 5

- Issue Five Hundred Twenty Eight 4

- Issue Five Hundred Twenty Five 3

- Issue Five Hundred Twenty Four 4

- Issue Five Hundred Twenty Nine 4

- Issue Five Hundred Twenty One 3

- Issue Five Hundred Twenty Seven 4

- Issue Five Hundred Twenty Six 4

- Issue Five Hundred Twenty Three 3

- Issue Five Hundred Twenty Two 4

- Issue Five Hundred Two 4

- Issue Forty 4

- Issue Forty Eight 5

- Issue Forty Five 6

- Issue Forty Four 6

- Issue Forty Nine 6

- Issue Forty One 4

- Issue Forty Seven 5

- Issue Forty Six 6

- Issue Forty Three 5

- Issue Forty Two 5

- Issue Four 5

- Issue Four Hundred 3

- Issue Four Hundred Eight 2

- Issue Four Hundred Eighteen 4

- Issue Four Hundred Eighty 4

- Issue Four Hundred Eighty Eight 4

- Issue Four Hundred Eighty Five 5

- Issue Four Hundred Eighty Four 3

- Issue Four Hundred Eighty Nine 4

- Issue Four Hundred Eighty One 4

- Issue Four Hundred Eighty Seven 3

- Issue Four Hundred Eighty Six 4

- Issue Four Hundred Eighty Three 4

- Issue Four Hundred Eighty Two 3

- Issue Four Hundred Eleven 3

- Issue Four Hundred Fifteen 3

- Issue Four Hundred Fifty 3

- Issue Four Hundred Fifty Eight 4

- Issue Four Hundred Fifty Five 4

- Issue Four Hundred Fifty Four 4

- Issue Four Hundred Fifty Nine 4

- Issue Four Hundred Fifty One 3

- Issue Four Hundred Fifty Seven 4

- Issue Four Hundred Fifty Six 4

- Issue Four Hundred Fifty Three 4

- Issue Four Hundred Fifty Two 4

- Issue Four Hundred Five 4

- Issue Four Hundred Forty 4

- Issue Four Hundred Forty Eight 3

- Issue Four Hundred Forty Five 3

- Issue Four Hundred Forty Four 4

- Issue Four Hundred Forty Nine 3

- Issue Four Hundred Forty One 3

- Issue Four Hundred Forty Seven 3

- Issue Four Hundred Forty Six 3

- Issue Four Hundred Forty Three 2

- Issue Four Hundred Forty Two 5

- Issue Four Hundred Four 3

- Issue Four Hundred Fourteen 4

- Issue Four Hundred Nine 5

- Issue Four Hundred Nineteen 4

- Issue Four Hundred Ninety 4

- Issue Four Hundred Ninety Eight 4

- Issue Four Hundred Ninety Five 3

- Issue Four Hundred Ninety Four 4

- Issue Four Hundred Ninety Nine 3

- Issue Four Hundred Ninety One 3

- Issue Four Hundred Ninety Seven 3

- Issue Four Hundred Ninety Six 4

- Issue Four Hundred Ninety Three 4

- Issue Four Hundred Ninety Two 5

- Issue Four Hundred One 3

- Issue Four Hundred Seven 3

- Issue Four Hundred Seventeen 3

- Issue Four Hundred Seventy 4

- Issue Four Hundred Seventy Eight 4

- Issue Four Hundred Seventy Five 4

- Issue Four Hundred Seventy Four 4

- Issue Four Hundred Seventy Nine 4

- Issue Four Hundred Seventy One 5

- Issue Four Hundred Seventy Seven 4

- Issue Four Hundred Seventy Six 3

- Issue Four Hundred Seventy Three 3

- Issue Four Hundred Seventy Two 4

- Issue Four Hundred Six 4

- Issue Four Hundred Sixteen 3

- Issue Four Hundred Sixty 3

- Issue Four Hundred Sixty Eight 4

- Issue Four Hundred Sixty Five 5

- Issue Four Hundred Sixty Four 4

- Issue Four Hundred Sixty Nine 2

- Issue Four Hundred Sixty One 3

- Issue Four Hundred Sixty Seven 4

- Issue Four Hundred Sixty Six 4

- Issue Four Hundred Sixty Three 4

- Issue Four Hundred Sixty Two 4

- Issue Four Hundred Ten 3

- Issue Four Hundred Thirteen 3

- Issue Four Hundred Thirty 3

- Issue Four Hundred Thirty Eight 3

- Issue Four Hundred Thirty Five 4

- Issue Four Hundred Thirty Four 3

- Issue Four Hundred Thirty Nine 4

- Issue Four Hundred Thirty One 4

- Issue Four Hundred Thirty Seven 4

- Issue Four Hundred Thirty Six 4

- Issue Four Hundred Thirty Three 3

- Issue Four Hundred Thirty Two 3

- Issue Four Hundred Three 4

- Issue Four Hundred Twelve 3

- Issue Four Hundred Twenty 3

- Issue Four Hundred Twenty Eight 3

- Issue Four Hundred Twenty Five 3

- Issue Four Hundred Twenty Four 4

- Issue Four Hundred Twenty Nine 3

- Issue Four Hundred Twenty One 3

- Issue Four Hundred Twenty Seven 4

- Issue Four Hundred Twenty Six 3

- Issue Four Hundred Twenty Three 4

- Issue Four Hundred Twenty Two 4

- Issue Four Hundred Two 3

- Issue Fourteen 4

- Issue Nine 5

- Issue Nineteen 4

- Issue Ninety 5

- Issue Ninety-Eight 3

- Issue Ninety-Five 4

- Issue Ninety-Four 4

- Issue Ninety-Nine 3

- Issue Ninety-one 6

- Issue Ninety-Seven 2

- Issue Ninety-Six 3

- Issue Ninety-Three 5

- Issue Ninety-Two 4

- Issue Nintey-Three 1

- Issue One 5

- Issue One Hundred 4

- Issue One Hundred Eight 3

- Issue One Hundred Eighteen 3

- Issue One Hundred Eighty 3

- Issue One Hundred Eighty Eight 3

- Issue One Hundred Eighty Five 3

- Issue One Hundred Eighty Four 3

- Issue One Hundred Eighty Nine 3

- Issue One Hundred Eighty One 4

- Issue One Hundred Eighty Seven 3

- Issue One Hundred Eighty Six 3

- Issue One Hundred Eighty Three 3

- Issue One Hundred Eighty Two 3

- Issue One Hundred Eleven 3

- Issue One Hundred Fifteen 4

- Issue One Hundred Fifty 3

- Issue One Hundred Fifty Eight 3

- Issue One Hundred Fifty Five 2

- Issue One Hundred Fifty Four 3

- Issue One Hundred Fifty Nine 4

- Issue One Hundred Fifty One 2

- Issue One Hundred Fifty Seven 3

- Issue One Hundred Fifty Six 4

- Issue One Hundred Fifty Three 2

- Issue One Hundred Fifty Two 6

- Issue One Hundred Five 3

- Issue One Hundred Forty 3

- Issue One Hundred Forty Eight 4

- Issue One Hundred Forty Five 4

- Issue One Hundred Forty Four 2

- Issue One Hundred Forty Nine 4

- Issue One Hundred Forty One 3

- Issue One Hundred Forty Seven 3

- Issue One Hundred Forty Six 4

- Issue One Hundred Forty Three 4

- Issue One Hundred Forty Two 3

- Issue One Hundred Four 4

- Issue One Hundred Fourteen 4

- Issue One Hundred Nine 3

- Issue One Hundred Nineteen 5

- Issue One Hundred Ninety 3

- Issue One Hundred Ninety Eight 3

- Issue One Hundred Ninety Five 4

- Issue One Hundred Ninety Four 3

- Issue One Hundred Ninety Nine 4

- issue One Hundred Ninety One 3

- Issue One Hundred Ninety Seven 2

- Issue One Hundred Ninety Six 3

- Issue One Hundred Ninety Three 3

- Issue One Hundred Ninety Two 3

- Issue One Hundred One 3

- Issue One Hundred Seven 3

- Issue One Hundred Seventeen 3

- Issue One Hundred Seventy 4

- Issue One Hundred Seventy Eight 3

- Issue One Hundred Seventy Five 3

- Issue One Hundred Seventy Four 3

- Issue One Hundred Seventy Nine 3

- Issue One Hundred Seventy One 4

- Issue One Hundred Seventy Seven 2

- Issue One Hundred Seventy Six 3

- Issue One Hundred Seventy Three 3

- Issue One Hundred Seventy Two 2

- Issue One Hundred Six 3

- Issue One Hundred Sixteen 4

- Issue One Hundred Sixty 4

- Issue One Hundred Sixty Eight 4

- Issue One Hundred Sixty Five 3

- Issue One Hundred Sixty Four 3

- Issue One Hundred Sixty Nine 3

- Issue One Hundred Sixty One 4

- Issue One Hundred Sixty Seven 3

- Issue One Hundred Sixty Six 2

- Issue One Hundred Sixty Three 4

- Issue One Hundred Sixty Two 4

- Issue One Hundred Ten 4

- Issue One Hundred Thirteen 4

- Issue One Hundred Thirty 4

- Issue One Hundred Thirty Eight 3

- Issue One Hundred Thirty Five 4

- Issue One Hundred Thirty Four 7

- Issue One Hundred Thirty Nine 4

- Issue One Hundred Thirty One 4

- Issue One Hundred Thirty Seven 3

- Issue One Hundred Thirty Six 4

- Issue One Hundred Thirty Three 4

- Issue One Hundred Thirty Two 5

- Issue One Hundred Three 3

- Issue One Hundred Twelve 2

- Issue One Hundred Twenty 4

- Issue One Hundred Twenty Eight 4

- Issue One Hundred Twenty Five 3

- Issue One Hundred Twenty Four 4

- Issue One Hundred Twenty Nine 4

- Issue One Hundred Twenty One 4

- Issue One Hundred Twenty Seven 4

- Issue One Hundred Twenty Six 4

- Issue One Hundred Twenty Three 5

- Issue One Hundred Twenty Two 3

- Issue One Hundred Two 3

- Issue Seven 4

- Issue Seventeen 5

- Issue Seventy 5

- Issue Seventy-Eight 6

- Issue Seventy-Five 7

- Issue Seventy-Four 6

- Issue Seventy-Nine 6

- Issue Seventy-One 6

- Issue Seventy-Seven 6

- Issue Seventy-Six 6

- Issue Seventy-Three 5

- Issue Seventy-Two 6

- Issue Six 4

- Issue Six Hundred Thirty Four 1

- Issue Sixteen 5

- Issue Sixty 7

- Issue Sixty Eight 6

- Issue Sixty Five 5

- Issue Sixty Four 5

- Issue Sixty Nine 6

- Issue Sixty One 5

- Issue Sixty Seven 6

- Issue Sixty Six 6

- Issue Sixty Three 5

- Issue Sixty Two 6

- Issue Ten 5

- Issue Thirteen 5

- Issue Thirty 7

- Issue Thirty Eight 4

- Issue Thirty Five 3

- Issue Thirty Four 6

- Issue Thirty Nine 5

- Issue Thirty One 5

- Issue Thirty Seven 5

- Issue Thirty Six 4

- Issue Thirty Three 7

- Issue Thirty Two 5

- Issue Thirty Two 1

- Issue Three 5

- Issue Three Hundred 3

- Issue Three Hundred and Eighty 4

- Issue Three Hundred and Sixty Five 2

- Issue Three Hundred Eight 4

- Issue Three Hundred Eighteen 3

- Issue Three Hundred Eighty Eight 4

- Issue Three Hundred Eighty Five 4

- Issue Three Hundred Eighty Four 4

- Issue Three Hundred Eighty Nine 4

- Issue Three Hundred Eighty One 4

- Issue Three Hundred Eighty Seven 4

- Issue Three Hundred Eighty Six 3

- Issue Three Hundred Eighty Three 4

- Issue Three Hundred Eighty Two 3

- Issue Three Hundred Eleven 3

- Issue Three Hundred Fifteen 4

- Issue Three Hundred Fifty 4

- Issue Three Hundred Fifty Eight 4

- Issue Three Hundred Fifty Five 3

- Issue Three Hundred Fifty Four 4

- Issue Three Hundred Fifty Nine 3

- Issue Three Hundred Fifty One 3

- Issue Three Hundred Fifty Seven 3

- Issue Three Hundred Fifty Six 3

- Issue Three Hundred Fifty Three 3

- Issue Three Hundred Fifty Two 3

- Issue Three Hundred Five 3

- Issue Three Hundred Forty 3

- Issue Three Hundred Forty Eight 3

- Issue Three Hundred Forty Five 3

- Issue Three Hundred Forty Four 3

- Issue Three Hundred Forty Nine 3

- Issue Three Hundred Forty One 4

- Issue Three Hundred Forty Seven 3

- Issue Three Hundred Forty Six 3

- Issue Three Hundred Forty Three 3

- Issue Three Hundred Forty Two 3

- Issue Three Hundred Four 3

- Issue Three Hundred Fourteen 3

- Issue Three Hundred Nine 3

- Issue Three Hundred Nineteen 4

- Issue Three Hundred Ninety 3

- Issue Three Hundred Ninety Eight 3

- Issue Three Hundred Ninety Five 3

- Issue Three Hundred Ninety Four 3

- Issue Three Hundred Ninety Nine 3

- Issue Three Hundred Ninety One 3

- Issue Three Hundred Ninety Seven 4

- Issue Three Hundred Ninety Six 4

- Issue Three Hundred Ninety Three 4

- Issue Three Hundred Ninety Two 5

- Issue Three Hundred One 3

- Issue Three Hundred Seven 3

- Issue Three Hundred Seventeen 3

- Issue Three Hundred Seventy 3

- Issue Three Hundred Seventy Eight 3

- Issue Three Hundred Seventy Five 3

- Issue Three Hundred Seventy Four 3

- Issue Three Hundred Seventy Nine 4

- Issue Three Hundred Seventy One 3

- Issue Three Hundred Seventy Seven 3

- Issue Three Hundred Seventy Six 4

- Issue Three Hundred Seventy Three 3

- Issue Three Hundred Seventy Two 3

- Issue Three Hundred Six 4

- Issue Three Hundred Sixteen 3

- Issue Three Hundred Sixty 3

- Issue Three Hundred Sixty Eight 3

- Issue Three Hundred Sixty Four 4

- Issue Three Hundred Sixty Nine 3

- Issue Three Hundred Sixty One 4

- Issue Three Hundred Sixty Seven 5

- Issue Three Hundred Sixty Six 5

- Issue Three Hundred Sixty Three 4

- Issue Three Hundred Sixty Two 3

- Issue Three Hundred Ten 3

- Issue Three Hundred Thirteen 3

- Issue Three Hundred Thirty 2

- Issue Three Hundred Thirty Eight 4

- Issue Three Hundred Thirty Five 2

- Issue Three Hundred Thirty Four 3

- Issue Three Hundred Thirty Nine 3

- Issue Three Hundred Thirty One 2

- Issue Three Hundred Thirty Seven 4

- Issue Three Hundred Thirty Six 3

- Issue Three Hundred Thirty Three 3

- Issue Three Hundred Thirty Two 3

- Issue Three Hundred Three 3

- Issue Three Hundred Twelve 3

- Issue Three Hundred Twenty 3

- Issue Three Hundred Twenty Eight 4

- Issue Three Hundred Twenty Five 3

- Issue Three Hundred Twenty Four 4

- Issue Three Hundred Twenty Nine 4

- Issue Three Hundred Twenty One 3

- Issue Three Hundred Twenty Seven 3

- Issue three hundred twenty six 2

- Issue Three Hundred Twenty Three 4

- Issue Three Hundred Twenty Two 3

- Issue Three Hundred Two 4

- Issue Thrity Five 1

- Issue Twelve 4

- Issue Twenty 5

- Issue Twenty Eight 5

- Issue Twenty Five 4

- Issue Twenty Four 4

- Issue Twenty Nine 4

- Issue Twenty One 5

- Issue Twenty Seven 3

- Issue Twenty Six 4

- Issue Twenty Three 4

- Issue Twenty Two 5

- Issue Two 4

- Issue Two Hundred 4

- Issue Two Hundred Eight 3

- Issue Two Hundred Eighteen 1

- Issue Two Hundred Eighty 2

- Issue Two Hundred Eighty Eight 3

- Issue Two Hundred Eighty Five 3

- Issue Two Hundred Eighty Four 3

- Issue Two Hundred Eighty Nine 2

- Issue Two Hundred Eighty One 4

- Issue Two Hundred Eighty Seven 3

- Issue Two Hundred Eighty Six 4

- Issue Two Hundred Eighty Three 2

- Issue Two Hundred Eighty Two 3

- Issue Two Hundred Eleven 3

- Issue Two Hundred Fifteen 3

- Issue Two Hundred Fifty 3

- Issue Two Hundred Fifty Eight 3

- Issue Two Hundred Fifty Five 3

- Issue Two Hundred Fifty Four 3

- Issue Two Hundred Fifty Nine 2

- Issue Two Hundred Fifty One 3

- Issue Two Hundred Fifty Seven 2

- Issue Two Hundred Fifty Six 3

- Issue Two Hundred Fifty Three 1

- Issue Two Hundred Fifty Two 3

- Issue Two Hundred Five 3

- Issue Two Hundred Forty 3

- Issue Two Hundred Forty Eight 3

- Issue Two Hundred Forty Five 2

- Issue Two Hundred Forty Four 3

- Issue Two Hundred Forty Nine 3

- Issue Two Hundred Forty One 3

- Issue Two Hundred Forty Seven 3

- Issue Two Hundred Forty Six 2

- Issue Two Hundred Forty Three 1

- Issue Two Hundred Forty Two 2

- Issue Two Hundred Four 2

- Issue Two Hundred Fourteen 3

- Issue Two Hundred Nine 3

- Issue Two Hundred Nineteen 3

- Issue Two Hundred Ninety 3

- Issue Two Hundred Ninety Eight 4

- Issue Two Hundred Ninety Five 2

- Issue Two Hundred Ninety Four 3

- Issue Two Hundred Ninety Nine 3

- Issue Two Hundred Ninety One 4

- Issue Two Hundred Ninety Seven 4

- Issue Two Hundred Ninety Six 3

- Issue Two Hundred Ninety Three 4

- Issue Two Hundred Ninety Two 3

- Issue Two Hundred One 3

- Issue Two Hundred Seven 3

- Issue Two Hundred Seventeen 3

- Issue Two Hundred Seventy 3

- Issue Two Hundred Seventy Eight 3

- Issue Two Hundred Seventy Five 3

- Issue Two Hundred Seventy Four 3

- Issue Two Hundred Seventy Nine 3

- Issue Two Hundred Seventy One 2

- Issue Two Hundred Seventy Seven 3

- Issue Two Hundred Seventy Six 3

- Issue Two Hundred Seventy Three 3

- Issue Two Hundred Seventy Two 3

- Issue Two Hundred Six 3

- Issue Two Hundred Sixteen 3

- Issue Two Hundred Sixty 3

- Issue Two Hundred Sixty Eight 3

- Issue Two Hundred Sixty Five 4

- Issue Two Hundred Sixty Four 3

- Issue Two Hundred Sixty Nine 3

- Issue Two Hundred Sixty One 3

- Issue Two Hundred Sixty Seven 3

- Issue Two Hundred Sixty Six 3

- Issue Two Hundred Sixty Three 6

- Issue Two Hundred Sixty Two 3

- Issue Two Hundred Ten 2

- Issue Two Hundred Thirteen 4

- Issue Two Hundred Thirty 4

- Issue Two Hundred Thirty Eight 4

- Issue Two Hundred Thirty Five 4

- Issue Two Hundred Thirty Four 3

- Issue Two Hundred Thirty Nine 2

- Issue Two Hundred Thirty One 2

- Issue Two Hundred Thirty Seven 2

- Issue Two Hundred Thirty Six 4

- Issue Two Hundred Thirty Three 3

- Issue Two Hundred Thirty Two 3

- Issue Two Hundred Three 3

- Issue Two Hundred Twelve 3

- Issue Two Hundred Twenty 3

- Issue Two Hundred Twenty Eight 4

- Issue Two Hundred Twenty Five 3

- Issue Two Hundred Twenty Four 4

- Issue Two Hundred Twenty Nine 3

- Issue Two Hundred Twenty One 4

- Issue Two Hundred Twenty Seven 2

- Issue Two Hundred Twenty Six 4

- Issue Two Hundred Twenty Three 2

- Issue Two Hundred Twenty Two 3

- Issue Two Hundred Two 3

- No Fee Contest 1

- One Hundred Forty Seven 1

- Letter from the Editor 8

- Always open to submissions 40

- Anthology 4

- Chapbooks 2

- Creative Non Fiction 267

- Electronic 4

- Fiction 391

- Paying Market 50

- Translation 3

- Academic 17

- Accept Previously Published Work 1

- All Genres 29

- Chick Lit 5

- Children's Books 114

- Christian 29

- Cookbooks 15

- Gift Books 15

- Graphic Novel 6

- Historical Fiction 20

- Literary Fiction 65

- New Adult 4

- Non Fiction 182

- Offers Advances 8

- Paranormal 16

- Science Fiction 61

- Self Help 7

- Southern Fiction 2

- Speculative Fiction 8

- Women's Fiction 17

- Young Adult 79

- Issue Four 1

- Issue Six 1

- Issue Three 1

- Issue Two 1

- Publishing Guides 76

- Publishing Industry News 1

- Quote of the Week 78

- Self Publishing 22

- Issue One Hundred Ninety One 1

- Special Issue 365

- Success Stories 6

- The Authors Publish Fund for Literary Journals 1

- The Other Side of the Desk 6

- Uncategorized 108

- Writing Prompt 85

About Us: We're dedicated to helping authors build their writing careers. We send you reviews of publishers accepting submissions, and articles to help you become a successful, published, author. Everything is free and delivered via email. You can view our privacy policy here. To get started sign up for our free email newsletter .

To be, or not to be from Hamlet

By William Shakespeare

“To be, or not to be,” the opening line of Hamlet’s mindful soliloquy, is one of the most thought-provoking quotes of all time. The monologue features the important theme of existential crisis.

William Shakespeare

His plays and poems are read all over the world.

Poem Analyzed by Sudip Das Gupta

First-class B.A. Honors Degree in English Literature

The “To be, or not to be” quote is taken from the first line of Hamlet’s soliloquy that appears in Act 3, Scene 1 of the eponymous play by William Shakespeare ( Bio | Poems ) , “Hamlet”. The full quote, “To be, or not to be, that is the question” is famous for its open-ended meaning that not only encompasses the thoughts raging inside Hamlet’s mind but also features the theme of existential crisis. Digging deeper into the soliloquy reveals a variety of concepts and meanings that apply to all human beings. For this reason, the quote has become a specimen for understanding how Shakespeare thought.

Explore To be, or not to be

- 3 Structure

- 4 Literary Devices

- 5 Detailed Analysis

- 6 Historical Context

- 7 Notable Usage

- 9 Similar Quotes

In Act 3, Scene 1, also known as the “nunnery scene,” of the tragedy , “Hamlet” by William Shakespeare ( Bio | Poems ) , this monologue appears. Hamlet, torn between life and death, utters the words to the audience revealing what is happening inside his mind. It is a soliloquy because Hamlet does not express his thoughts to other characters. Rather he discusses what he thinks in that critical juncture with his inner self.

Before reading this soliloquy, readers have to go through the plots that happened in the play. In the previous plots, Hamlet has lost his father. He is broken to know the fact that his uncle Claudius killed his father treacherously and married his mother, Gertrude. Having a conversation with the ghost of his father, he is torn between perception and reality.

In such a critical situation, Hamlet feels extremely lonely as there are no other persons to console him. Besides, Ophelia is not accepting his love due to the pressure from her family. For all the things happening in his life, he feels it is better to die rather than living and mutely bearing the pangs that life is sending him in a row. Being engrossed with such thoughts, he utters this soliloquy, “To be, or not to be.”

“To be, or not to be” by William Shakespeare ( Bio | Poems ) describes how Hamlet is torn between life and death. His mental struggle to end the pangs of his life gets featured in this soliloquy.

Hamlet’s soliloquy begins with the memorable line, “To be, or not to be, that is the question.” It means that he cannot decide what is better, ending all the sufferings of life by death, or bearing the mental burdens silently. He is in such a critical juncture that it seems death is more rewarding than all the things happening with him for the turn of fortune.

Death is like sleep, he thinks, that ends this fitful fever of life. But, what dreams are stored for him in the pacifying sleep of death. This thought makes him rethink and reconsider. Somehow, it seems to him that before diving deeper into the regions of unknown and unseen, it is better to wait and see. In this way, his subconscious mind makes him restless and he suffers in inaction.

The full quotation is regarded as a soliloquy. Though in the plot , Ophelia is on stage pretending to read, Hamlet expresses his thoughts only to himself. He is unaware of the fact that Ophelia is already there. Being engrossed in his self-same musing, he clarifies his thoughts to himself first as he is going to take a tough decision.

Therefore, this quote is a soliloquy that Shakespeare uses as a dramatic device to let Hamlet make his thoughts known to the audience, addressing them indirectly.

In the earliest version of the play, this monologue is 35 lines long. The last two lines are often excluded from the soliloquy as those lines contain the mental transition of the speaker , from thoughts to reality.

The overall soliloquy is in blank verse as the text does not have a rhyming scheme . Most of Shakespeare’s dramas are written in this form. Besides, it is written in iambic pentameter with a few metrical variations.

For example, let’s have a look at the metrically scanned opening line of the soliloquy:

To be ,/ or not / to be ,/ that is / the quest(io)n :

The last syllable of the line contains an elision .

Literary Devices

The first line of the speech , “To be, or not to be, that is the question” contains two literary devices. These are antithesis and aporia . The following lines also contain aporia.

Readers come across a metaphor in, “The slings and arrows of outrageous fortune.” This line also contains a personification . Another device is embedded in the line. After rereading the line, it can be found that there is a repetition of the “r” sound. It’s an alliteration .

There is another metaphor in the phrase, “sea of troubles.” In the next two lines, Shakespeare uses enjambment and internally connects the lines for maintaining the speech’s flow.

Readers can find a use of synecdoche in the line, “That flesh is heir to.” They can find an anadiplosis in the lines, “To die, to sleep;/ To sleep, perchance to dream.” Besides, a circumlocution or hyperbaton can be found in this line, “When we have shuffled off this mortal coil.”

After this line, the speaker presents a series of causes that lead to his suffering. These lines collectively contain a device called the climax . Using this device, Shakespeare presents the most shocking idea at the very end. He uses a rhetorical question , “With a bare bodkin?” at the end to heighten this dramatic effect.

There is an epigram in the line, “Thus conscience doth make cowards of us all.” The following lines contain this device as well.

Detailed Analysis

To be, or not to be, that is the question:

The first line of Hamlet’s soliloquy, “To be, or nor to be” is one of the best-known quotes from all the Shakespearean works combined. In the play, “Hamlet” the tragic hero expresses this soliloquy to the audience in Act 3, Scene 1. As the plots reflect, Hamlet is facing an existential crisis after coming across the harsh reality of his father’s death and his mother’s subsequent marriage with his uncle, Claudius, the murderer of King Hamlet. Everything was happening so quickly that it was difficult to digest their effect.

The truth, like arrows bolting directly toward his mind, made him so vulnerable that he was just a step behind madness or death. It is not clear whether Hamlet’s deliriously spoke this soliloquy or he was preparing himself to die. Whatsoever, through this dramatic device, Shakespeare projects how Hamlet’s mind is torn between life and death.

The first line of his soliloquy is open-ended. It is a bit difficult to understand what the question is. “To be, or not be” is an intellectual query that a princely mind is asking the readers. This antithetical idea reveals Hamlet is not sure whether he wants to live or die. If readers strictly adhere to the plot, they can decode this line differently. It seems that the hero is asking whether it is right to be a murderer for the right cause or be merciful for saving his soul from damnation.

Firstly, if he chooses to avenge his father’s death, it will eventually kill the goodness in him. Secondly, if he refuses to submit to his animalistic urges, the pain lying deep in his subconscious mind is going to torture his soul. For this reason, he is going through a mental crisis regarding which path to choose. This question is constantly confusing his mind.

Lines 2–5

Whether ’tis nobler in the mind to suffer The slings and arrows of outrageous fortune, Or to take arms against a sea of troubles And by opposing end them.

From these lines, it becomes clear what questions are troubling the tragic hero, Hamlet. He is asking just a simple question. Readers should not take this question at its surface value. They have to understand what is going on in his mind. He asks whether a noble mind like him has to suffer the metaphorical “slings and arrows of outrageous fortune.” In this phrase, Shakespeare compares fortune to an archer who releases arrows and hurts Hamlet’s mind.

The speaker talks about the events happening in his life for his misfortune . Those situations not only make his mind bruised but also make him vulnerable to the upcoming arrows. In such a critical mental state, a single blow of fortune can end his life. But, he has not submitted himself to fate yet. He is ready to fight against those troubles and end them all at once.

The phrase, “sea of troubles” contains hyperbole . It also contains a metaphor. The comparison is between the vastness of the sea to the incalculable troubles of the speaker’s life. It is important to mention here that the speaker just wants an answer. He badly wants to end the troubles but he thinks by choosing the safest path of embracing death, he can also finish his mental sufferings.

Lines 5–9

To die—to sleep, No more; and by a sleep to say we end The heart-ache and the thousand natural shocks That flesh is heir to: ’tis a consummation Devoutly to be wish’d.

In this section of the soliloquy, “To be, or not to be” Hamlet’s utterings reflect a sense of longing for death. According to him, dying is like sleeping. Through this sleep that will help him to end the mental sufferings, he can get a final relief. The phrase, “No more” emphasizes how much he longs for this eternal sleep.

This path seems more relieving for Hamlet. Why is it so? Hamlet has to undergo a lot of troubles to be free from the shackles of “outrageous fortune.” While if he dies, there is no need to do anything. Just a moment can end, all of his troubles. It seems easier than said. However, for a speaker like Hamlet who has seen much, the cold arm of death is more soothing than the tough punches of fortune.

For this reason, he wants to take a nap in the bosom of death. In this way, the heartache and shocks will come to an end. The speaker refers to two types of pain. One is natural that troubles every human being. While another pain is inflicted by the wrongs of others. The sufferer cannot put an end to such suffering. However, death can end both of these pains.

There are thousands of natural shocks that the human body is destined to suffer. What are these shocks? It includes the death of a loved one, disease, bodily impairment, and many more. In Hamlet’s case, losing his dear father tragically is a natural shock. But, the cause of the death increases the intensity of the shock. The subsequent events, one by one, add more burdens on Hamlet’s mind.

To end this mental tension, Hamlet devoutly wishes for the “consummation” that will not only relieve him but also end the cycle of events. Here, Shakespeare uses the word “consummation” in its metaphorical sense. The final moment when all the sufferings come to an end is death. So, it’s a consummation that is devoutly wished.

Lines 9–14

To die, to sleep; To sleep, perchance to dream—ay, there’s the rub: For in that sleep of death what dreams may come, When we have shuffled off this mortal coil, Must give us pause—there’s the respect That makes calamity of so long life.

Again, Shakespeare uses the repetition of the phrase, “To die, to sleep.” It is the second instance where Hamlet uses these words. If readers closely analyze the lines, it will be clear that Hamlet uses this phrase to mark a transition in his thoughts. Besides, it also clarifies what the dominant thought of his mind is. Undoubtedly, it is the thoughts of death. Not death, to be specific. He sees death as sleeping. How he thinks about death, reveals the way he thinks about life.

According to him, life means a concoction of troubles and shocks. While death is something that has an embalming effect on his mind. Therefore, he values death over life. When does a person think like that? Just before committing suicide or yielding to death wholeheartedly, such thoughts appear in a person’s mind.

From the next lines, there is an interesting transition in Hamlet’s thinking process. Previously, death seems easier than living. But, when he thinks about the dreams he is going to see in his eternal sleep, he becomes aware of the reality. From his thought process, it becomes clear. According to him, when humans die, they are not aware of what dreams will come in their sleep. It makes them stretch out their sufferings for so long.

Lines 15–21

For who would bear the whips and scorns of time, Th’oppressor’s wrong, the proud man’s contumely, The pangs of dispriz’d love, the law’s delay, The insolence of office, and the spurns That patient merit of th’unworthy takes, When he himself might his quietus make With a bare bodkin?

In this part of the “To be, or not to be” quote, Hamlet’s subconscious mind reminds him about his sufferings. The situations mentioned here have occurred in others’ lives too. Let’s see what Hamlet is saying to the audience.

According to him, none can bear the “whips and scorns” of time. Readers have to take note of the fact that Hamlet is referring to “time” here. Whereas in the first few lines, he talks about “fortune.” So, in one way or another, he is becoming realistic.

The sufferings that time sends are out of one’s control. A person has to bear whatever it sends and react accordingly. There is nothing more he can do to change the course of time as it is against nature. Not only that, Hamlet is quite depressed by the wrongs inflicted upon the innocents by the haughty kings.

The insults of proud men, pangs of unrequited love, delay in judgment, disrespectful behavior of those in power, and last but not least the mistreatment that a “patient merit” receives from the “unworthy” pain him deeply. He is mistreated in all spheres, be it on a personal level such as love, or in public affairs. In all cases, he is the victim. He has gone through all such pangs while he can end his life with a “bare bodkin.” Bodkin is an archaic term for a dagger.

In this way, Hamlet is feeling death is the easiest way to end all the pains and mistreatment he received from others. These lines reveal how the mental tension is reaching its climax.

Lines 21–27

Who would fardels bear, To grunt and sweat under a weary life, But that the dread of something after death, The undiscovere’d country, from whose bourn No traveller returns, puzzles the will, And makes us rather bear those ills we have Than fly to others that we know not of?

The first two lines of this section refer to the fact that none choose to “grunt and sweat” through the exhausting life. In the first line, “fardels” mean the burdens of life. According to the narrator , life seems an exhausting journey that has nothing to offer instead of suffering and pain. To think about life in this way makes the speaker’s mind wearier than before.

From the following lines, Hamlet makes clear why he cannot proceed further and die. He is not sure whether life after death is that smooth as he thinks. It is possible that even after his death, he will not be relieved. He knows death is an “undiscovered country.” Only those who have already gone there know how it is. Besides, nobody can return from death’s dominion. A living being cannot know what happens there.

Such thoughts confuse the speaker more. It puzzles his will to do something that can end his mental pain. Therefore, he has to bear the ills of life throughout the journey than flying to the unknown regions of death. In the last line, Shakespeare uses a rhetorical question to make readers think about what the speaker is trying to mean.

At this point of the whole soliloquy, it becomes crystal clear that Hamlet is not ready to embrace death easily. He is just thinking. At one point, he gives the hint that death seems easier than bearing life’s ills. On the other hand, he negates his idea and says it is better to bear the reality rather than finding solace in perception.

Lines 28–35

Thus conscience doth make cowards of us all, And thus the native hue of resolution Is sicklied o’er with the pale cast of thought, And enterprises of great pith and moment With this regard their currents turn awry And lose the name of action.—Soft you now, The fair Ophelia!—Nymph, in thy orisons Be all my sins remembered.

The last section of the soliloquy, “To be, or not to be” begins with an epigrammatic idea. Here, the speaker says the “conscience doth make cowards of us all.” It means that the fear of death in one’s awareness makes him a coward. In Hamlet’s case, his aware mind makes him confused regarding the happenings after death. Not knowing a solid answer, he makes a coward of himself.

Alongside that, the natural boldness metaphorically referred to as “the native hue of resolution ,” becomes sick for the “pale cast of thought.” In “pale cast of thought,” Shakespeare personifies “thought” and invests it with the idea of casting pale eyes on a person. It means that when Hamlet thinks about death, his natural boldness fades away and he becomes a coward.

In the following lines, he remarks about how he suffers for inaction. According to him, such thoughts stop him from taking great action. It should be taken in a moment. In that place, the currents of action get misdirected and lose the name of action. It means that Hamlet is trying to take the final step but somehow his thoughts are holding him back. For this reason, the action of ending his sufferings loses the name of action.

The last few lines of the soliloquy present how Hamlet stops his musings when he discovers his beloved Ophelia is coming that way. He wishes that she may remember him in her prayers.

Historical Context

The text of “To be, or not to be” is taken from the Second Quarto (Q2) of the play, “Hamlet” which was published in 1604. It is considered the earliest version of the play. William Shakespeare ( Bio | Poems ) wrote, “The Tragedy of Hamlet, Prince of Denmark,” best-known as only “Hamlet” sometime between 1599 and 1601. It is the longest play of Shakespeare containing 29,551 words.

Shakespeare derived the story of Hamlet from the legend of Amleth. He may also have drawn on the play, “Ur-Hamlet,” an earlier Elizabethan play. Scholars believe that Shakespeare wrote this play and later revised it.

Before the 18th century, there was not any concrete idea regarding how the character of Hamlet is. After reading his soliloquies such as “To be, or not to be,” it became more confusing for the scholars to understand what category this Shakespearean hero falls in. Later, the 19th-century scholars valued the character for his internal struggles and tensions.

Through this soliloquy, readers can know a lot about Hamlet’s overall character. Firstly, he is consciously protestant in his thoughts. On the other hand, he is a philosophical character. His monologue, “To be, or not to be, that is the question” expounds the ideas of relativism, existentialism , and skepticism.

Notable Usage

The quote, “To be, or not to be” is the most widely known line and overall Hamlet’s soliloquy has been referenced in several works of theatre, literature, and music. Let’s have a look at some of the works where the opening line of Hamlet’s soliloquy is mentioned.

- The plot of the comedy , “To Be or Not to Be” by Ernst Lubitsch, is focused on Hamlet’s soliloquy.

- Charlie Chaplin recites this monologue in the comedy film A King in New York (1957).

- The line, “To be or not to be” inspired the title of the short story , “2 B R 0 2 B” by Kurt Vonnegut.

- Black liberation leader Malcolm X quoted the first lines of the soliloquy in a debate in Oxford in 1963 to make a point about “extremism in defense of liberty”.

- The sixth movie of Star Trek, “Undiscovered Country” was named after the line, “The undiscover’d country, from whose borne…” from the soliloquy.

Let’s watch two of the notable actors portraying the character of Hamlet.

Benedict Cumberbatch

Benedict Cumberbatch performed Hamlet at the Barbican Centre in London in 2015. Let’s see how our on-screen “Sherlock” performs Hamlet’s “To be, or not to be” onstage.

Andrew Scott

At the Almeida, Andrew Scott played Hamlet under the direction of Robert Icke in 2016. It’s interesting to know how “Moriarty” delves deeper into the character through this soliloquy.

In William Shakespeare’s play “Hamlet,” the titular character, Hamlet says this soliloquy .

“To be, or not be” means Hamlet’s mind is torn between two things, “being” and “not being.” “Being” means life and action. While “not being” refers to death and inaction.

The greatest English writer of all time, William Shakespeare wrote: “To be, or not be.” This quote appears in his tragedy Hamlet written sometime between 1599 and 1601.

In Act 3, Scene 1 of the play, Hamlet seems to be puzzled by the question of whether to live or die. He is standing in such a critical situation that life seems painful to bear and death appears to be an escape route from all the sufferings. In this existential crisis, Hamlet utters the soliloquy , “To be, or not to be, that is the question.”

In Shakespeare’s tragedy “Hamlet,” the central figure asks this question to himself. It is the first line of Hamlet’s widely known soliloquy .

This soliloquy is all about a speaker ’s existential crisis. In the play, Hamlet is going through a tough phase. He is torn between life and death, action and inaction. On both the way, he is aware of the fact that he is destined to suffer.

In Act 3 Scene 1 of “Hamlet,” Polonius forces Ophelia to return the love letters of Hamlet. In the meanwhile, he and Claudius watch from afar to understand Hamlet’s reaction. They wait for Ophelia to enter the scene. At that time, Hamlet is seen walking alone in the hall asking whether “to be or not to be.”

The opening line of Hamlet’s soliloquy , “To be, or not to be” is one of the most-quoted lines in English. The lines are famous for their simplicity. At the same time, the lines explore some of the deeper concepts such as action and inaction, life and death. Besides, the repetition of the phrase, “to be” makes this line easy to remember.

In Act 3 Scene 1, Hamlet is seen walking in the hall and musing whether “To be, or not be” to himself. It is a soliloquy that Hamlet speaks directly to the audience to make his thoughts and intentions known to them.

This soliloquy is 33 lines long and contains 262 words. It takes up to 4 minutes to perform.

Similar Quotes

Here is a list of some thought-provoking Shakespearean quotes that are similar to Hamlet’s soliloquy, ‘To be, or not to be” . Explore the greatest Shakespearean poetry and more works of William Shakespeare .

- All the World’s A Stage from As You Like It – In this monologue, the speaker considers the nature of the world, the roles men and women play, and how one turns old.

- Is This A Dagger Which I See Before Me from Macbeth – This famous soliloquy of Macbeth describes how he is taken over by guilt and insanity. His imagination brings forth a dagger that symbolizes the impending murder of Duncan.

- The quality of mercy is not strained from The Merchant of Venice – In this monologue of Ophelia, Shakespeare describes how mercy, an attribute of God, can save a person’s soul and elevate him to the degree of God.

- Tomorrow, and tomorrow, and tomorrow from Macbeth – In this soliloquy, the speaker sees life as a meaningless one that leads people to their inevitable death.

You can also read these heartfelt poems about depression and incredible poems about death .

Home » William Shakespeare » To be, or not to be from Hamlet

About Sudip Das Gupta

Join the poetry chatter and comment.

Exclusive to Poetry + Members

Join Conversations

Share your thoughts and be part of engaging discussions.

Expert Replies

Get personalized insights from our Qualified Poetry Experts.

Connect with Poetry Lovers

Build connections with like-minded individuals.

Good morning, I had a few questions.

- What is the language style of shakespeare in this solliluquy?

- What is the language technique of shakespeare in this solliluquy?

- What is the language structure in this solliluquy?

- Please explain all the literary devices used in here, I am very confused about them.

- What is the significance of the points presented in the soliloquy?

- Explain the modern day relevance as well

I am struggling with these questions, if you could reply as fast as possible, it would have been very helpful. Explain them perfectly, please.

This is a lot of questions! Have you read the article? It has a section on the structure and the techniques used which should answer many of these. So once you have had a read. If you still have a couple of pressing questions I will gladly help you out

Please help me, I know the answers, but how do I explain them?

Have you read the article? As I said to you the answers to most of your questions are in the article. I’m going to assume these questions are for a piece of homework. If that is the case then it’s really important to be able to read and synthesise information. Copying and pasting may get you out of an awkward situation but it won’t help you learn. So with that in mind, if you answer three of these questions (the answers are in the article) I will help you with the others. I don’t mind if the answers aren’t quite right. Do your best. If you head into an exam and right nothing you get no marks. If you give an answer you give yourself the potential to score some marks even if you’re unsure.

You attribute ‘The quality of mercy …’ to Ophelia (similar quotes, supra) when it should be attributed to Portia.

Thank you for highlighting this.

Access the Complete PDF Guide of this Poem

Poetry+ PDF Guides are designed to be the ultimate PDF Guides for poetry. The PDF Guide consists of a front cover, table of contents, with the full analysis, including the Poetry+ Review Corner and numerically referenced literary terms, plus much more.

Get the PDF Guide

Experts in Poetry

Our work is created by a team of talented poetry experts, to provide an in-depth look into poetry, like no other.

Cite This Page

Gupta, SudipDas. "To be, or not to be from Hamlet". Poem Analysis , https://poemanalysis.com/william-shakespeare/to-be-or-not-to-be/ . Accessed 3 July 2024.

Help Center