A Guide to Writing Dialogue, With Examples

“Guess what?” Tanika asked her mother.

“What?” her mother replied.

“I’m writing a short story,” Tanika said.

“Make sure you practice writing dialogue!” her mother instructed. “Because dialogue is one of the most effective tools a writer has to bring characters to life.” Give your writing extra polish Grammarly helps you communicate confidently Write with Grammarly

What is dialogue, and what is its purpose?

Dialogue is what the characters in your short story , poem , novel, play, screenplay, personal essay —any kind of creative writing where characters speak—say out loud.

For a lot of writers, writing dialogue is the most fun part of writing. It’s your opportunity to let your characters’ motivations, flaws, knowledge, fears, and personality quirks come to life. By writing dialogue, you’re giving your characters their own voices, fleshing them out from concepts into three-dimensional characters. And it’s your opportunity to break grammatical rules and express things more creatively. Read these lines of dialogue:

- “NoOoOoOoO!” Maddie yodeled as her older sister tried to pry her hands from the merry-go-round’s bars.

- “So I says, ‘You wanna play rough? C’mere, I’ll show you playin’ rough!’”

- “Get out!” she shouted, playfully swatting at his arm. “You’re kidding me, right? We couldn’t have won . . . ”

Dialogue has multiple purposes. One of them is to characterize your characters. Read the examples above again, and think about who each of those characters are. You learn a lot about somebody’s mindset, background, comfort in their current situation, emotional state, and level of expertise from how they speak.

Another purpose dialogue has is exposition, or background information. You can’t give readers all the exposition they need to understand a story’s plot up-front. One effective way to give readers information about the plot and context is to supplement narrative exposition with dialogue. For example, the protagonist might learn about an upcoming music contest by overhearing their coworkers’ conversation about it, or an intrepid adventurer might be told of her destiny during an important meeting with the town mystic. Later on in the story, your music-loving protagonist might express his fears of looking foolish onstage to his girlfriend, and your intrepid adventurer might have a heart-to-heart with the dragon she was sent to slay and find out the truth about her society’s cultural norms.

Dialogue also makes your writing feel more immersive. It breaks up long prose passages and gives your reader something to “hear” other than your narrator’s voice. Often, writers use dialogue to also show how characters relate to each other, their setting, and the plot they’re moving through.

It can communicate subtext, like showing class differences between characters through the vocabulary they use or hinting at a shared history between them. Sometimes, a narrator’s description just can’t deliver information the same way that a well-timed quip or a profound observation by a character can.

In contrast to dialogue, a monologue is a single, usually lengthy passage spoken by one character. Monologues are often part of plays.

The character may be speaking directly to the reader or viewer, or they could be speaking to one or more other characters. The defining characteristic of a monologue is that it’s one character’s moment in the spotlight to express their thoughts, ideas, and/or perspective.

Often, a character’s private thoughts are delivered via monologue. If you’re familiar with the term internal monologue , it’s referring to this. An internal monologue is the voice an individual ( though not all individuals ) “hears” in their head as they talk themselves through their daily activities. Your story might include one or more characters’ inner monologues in addition to their dialogue. Just like “hearing” a character’s words through dialogue, hearing their thoughts through a monologue can make a character more relatable, increasing a reader’s emotional investment in their story arc.

Types of dialogue

There are two broad types of dialogue writers employ in their work: inner and outer dialogue.

Inner dialogue is the dialogue a character has inside their head. This inner dialogue can be a monologue. In most cases, inner dialogue is not marked by quotation marks . Some authors mark inner dialogue by italicizing it.

Outer dialogue is dialogue that happens externally, often between two or more characters. This is the dialogue that goes inside quotation marks.

How to structure dialogue

Dialogue is a break from a story’s prose narrative. Formatting it properly makes this clear. When you’re writing dialogue, follow these formatting guidelines:

- All punctuation in a piece of dialogue goes inside the quotation marks.

- Quoted dialogue within a line of dialogue goes inside single quotation marks (“I told my brother, ‘Don’t do my homework for me.’ But he did it anyway!”). In UK English, quoted dialogue within a line of dialogue goes inside double quotation marks.

- Every time a new character speaks, start a new paragraph. This is true even when a character says only one word. Indent every new paragraph.

- When a character’s dialogue extends beyond a paragraph, use quotation marks at the beginning of the second and/or subsequent paragraph. However, there is no need for closing quotation marks at the end of the first paragraph—or any paragraph other than the final one.

- Example: “Thank you for—” “Is that a giant spider?!”

- “Every night,” he began, “I heard a rustling in the trees.”

- “Every day,” he stated. “Every day, I get to work right on time.”

Things to avoid when writing dialogue

When you’re writing dialogue, avoid these common pitfalls:

- Using a tag for every piece of dialogue: Dialogue tags are words like said and asked . Once you’ve established that two characters are having a conversation, you don’t need to tag every piece of dialogue. Doing so is redundant and breaks the reader’s flow. Once readers know each character’s voice, many lines of dialogue can stand alone.

- Not using enough tags: On the flip side, some writers use too few dialogue tags, which can confuse readers. Readers should always know who’s speaking. When a character’s mannerisms and knowledge don’t make that abundantly obvious, tag the dialogue and use their name.

- Dense, unrealistic speech: As we mentioned above, dialogue doesn’t need to be grammatically correct. In fact, when it’s too grammatically correct, it can make characters seem stiff and unrealistic.

- Anachronisms: A pirate in 1700s Barbados wouldn’t greet his captain with “what’s up?” Depending on how dedicated you (and your readers) are to historical accuracy, this doesn’t need to be perfect. But it should be believable.

- Eye dialect: This is an important one to keep in mind. Eye dialect is the practice of writing out characters’ mispronunciations phonetically, like writing “wuz” for “was.” Eye dialect can be (and has been) used to create offensive caricatures, and even when it’s not used in this manner, it can make dialogue difficult for readers to understand. Certain well-known instances of eye dialect, like “fella” for “fellow” and “‘em” for “them,” are generally deemed acceptable, but beyond these, it’s often best to avoid it.

How to write dialogue

Write how people actually speak (with some editing).

You want your characters to sound like real people. Real people don’t always speak in complete sentences or use proper grammar. So when you’re writing dialogue, break grammatical rules as you need to.

That said, your dialogue needs to still be readable. If the grammar is so bad that readers don’t understand what your characters are saying, they’ll probably just stop reading your story. Even if your characters speak in poor grammar, using punctuation marks correctly, even when they’re in the wrong places, will help readers understand the characters.

Here’s a quick example:

“I. Do. Not. WANT. to go back to boarding school!” Caleb shouted.

See how the period after each word forces your brain to stop and read each word as if it were its own sentence? The periods are doing what they’re supposed to do; they just aren’t being used to end sentences like periods typically do. Here’s another example of a character using bad grammar but the author using proper punctuation to make the dialogue understandable:

“Because no,” she said into the phone. “I need a bigger shed to store all my stuff in . . . yeah, no, that’s not gonna work for me, I told you what I need and now you gotta make it happen.”

Less is more

When you’re editing your characters’ dialogue, cut back all the parts that add nothing to the story. Real-life conversations are full of small talk and filler. Next time you read a story, take note of how little small talk and filler is in the dialogue. There’s a reason why TV characters never say “good-bye” when they hang up the phone: the “good-bye” adds nothing to the storyline. Dialogue should characterize people and their relationships, and it should also advance the plot.

Vary up your tags, but don’t go wild with them

“We love basketball!” he screamed.

“Why are you screaming?” the coach asked.

“Because I’m just so passionate about basketball!” he replied.

Dialogue tags show us a character’s tone. It’s good to have a variety of dialogue tags in your work, but there’s also nothing wrong with using a basic tag like “said” when it’s the most accurate way to describe how a character delivered a line. Generally, it’s best to keep your tags to words that describe actual speech, like:

You’ve probably come across more unconventional tags like “laughed” and “dropped.” If you use these at all, use them sparingly. They can be distracting to readers, and some particularly pedantic readers might be bothered because people don’t actually laugh or drop their words.

Give each character a unique voice (and keep them consistent)

If there is more than one character with a speaking role in your work, give each a unique voice. You can do this by varying their vocabulary, their speech’s pace and rhythm, and the way they tend to react to dialogue.

Keep each character’s voice consistent throughout the story by continuing to write them in the style you established. When you go back and proofread your work, check to make sure each character’s voice remains consistent—or, if it changed because of a perspective-shifting event in the story, make sure that this change fits into the narrative and makes sense. One way to do this is to read your dialogue aloud and listen to it. If something sounds off, revise it.

Dialogue examples

Inner dialogue.

As I stepped onto the bus, I had to ask myself: why was I going to the amusement park today, and not my graduation ceremony?

He thought to himself, this must be what paradise looks like.

Outer dialogue

“Mom, can I have a quarter so I can buy a gumball?”

Without skipping a beat, she responded, “I’ve dreamed of working here my whole life.”

“Ren, are you planning on stopping by the barbecue?”

“No, I’m not,” Ren answered. “I’ll catch you next time.”

Here’s a tip: Grammarly’s Citation Generator ensures your essays have flawless citations and no plagiarism. Try it for citing dialogue in Chicago , MLA , and APA styles.

Dialogue FAQs

What is dialogue.

Dialogue is the text that represents the spoken word.

How does dialogue work?

Dialogue expresses exactly what a character is saying. In contrast, a narrator might paraphrase or describe a character’s thoughts or speech.

What are different kinds of dialogue?

Inner dialogue is the dialogue a character has inside their own head. Often, it’s referred to as an inner monologue.

Outer dialogue is a conversation between two or more characters.

Joining the Dialogue: Practices for Ethical Research Writing. Bettina Stumm. Broadview Press, 2021

Author biography, andreas herzog.

Dr. Andreas Herzog

Visiting Assistant Professor

Claflin University

English Department

2 Trustee Hall

400 Magnolia Street

Orangeburg, SC 29115

Office phone: 803-535-5554

E-mail: [email protected]

Stumm, B. Joining the dialogue: Practices for ethical research writing. Broadview Press, 2021.

How to Cite

- Endnote/Zotero/Mendeley (RIS)

Copyright (c) 2022 Andreas Herzog

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License .

If this article is selected for publication in Discourse and Writing/Rédactologie, the work shall be published electronically under the terms of Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike ( CC BY-SA 4.0 ). This license allows users to adapt and build upon the published work, but requires them to attribute the original publication and license their derivative works under the same terms. There is no fee required for submission or publication. Authors retain unrestricted copyright and all publishing rights, and are permitted to deposit all versions of their paper in an institutional or subject repository.

Similar Articles

- Randy Allen Harris, Designing visual language: Strategies for professional communicators by Kostelnick, Charles, and David D. Roberts , Discourse and Writing/Rédactologie: Vol. 15 No. 1 (1999)

- Qinghua Chen, Higher Education Internationalization and English Language Instruction. Xiangying Huo. Springer, 2020 , Discourse and Writing/Rédactologie: Vol. 33 (2023)

- Lynette Hunter, Science: An Epitome of Democratic Politics , Discourse and Writing/Rédactologie: Vol. 16 No. 1 (2000)

- Lilita Rodman, Dynamics in Document Design: Creating Text for Readers by Karen Schriver , Discourse and Writing/Rédactologie: Vol. 14 No. 1 (1998)

- Russ Hunt, World Apart: Acting and Writing in Academic and Workplace Contexts" by Patrick Dias, Aviva Freedman, Peter Medway, and Anthony Pare , Discourse and Writing/Rédactologie: Vol. 18 No. 1 (2002)

- Mimi Zeiger, Essentials of Writing Biomedical Research Papers , Discourse and Writing/Rédactologie: Vol. 11 No. 1 (1993)

- Sandra Dueck, Humanistic Aspects of Technical Communication , Discourse and Writing/Rédactologie: Vol. 16 No. 2 (2000)

- Michael P. Jordan, Analyzing Everyday Texts: Discourse, Rhetoric and Social Perspectives , Discourse and Writing/Rédactologie: Vol. 16 No. 2 (2000)

- Lilita Rodman, Writing in the Workplace: New Research Perspectives by Rachel Spilka , Discourse and Writing/Rédactologie: Vol. 12 No. 2 (1995)

- Yaying Zhang, English and the Discourses of Colonialism , Discourse and Writing/Rédactologie: Vol. 17 No. 2 (2002)

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 > >>

You may also start an advanced similarity search for this article.

- Français (Canada)

Information

- For Readers

- For Authors

Part of the PKP Publishing Services Network

Sponsored by PKP Publishing Services

ISSN 2563-7320

Joining the Dialogue: Practices for Ethical Research Writing

About this ebook.

With this in mind, Joining the Dialogue is geared to helping students discover the key ethical practices of dialogue—receptivity and response-ability—as they join a research conversation. It also helps students master the dialogic structure of research essays as they write in and for their academic communities. Combining an ethical approach with accessible prose, dialogic structures and templates, practical exercises, and ample illustrations from across the disciplines, Joining the Dialogue teaches students not only how to write research essays but also how to write those essays ethically as a dialogue with other researchers and readers.

Ratings and reviews

Rate this ebook, reading information, similar ebooks.

Joining the Dialogue: Practices for Ethical Research Writing. Bettina Stumm. Broadview Press, 2021

- Andreas Herzog

…more information

Andreas Herzog Claflin University [email protected]

Online publication: Feb. 16, 2022

A review of the journal Discourse and Writing/Rédactologie

This article is a review of another work such as a book or a film. The original work discussed here is not available on this platform.

Volume 32, 2022 , p. 59–62

© Andreas Herzog, 2022

Download the article in PDF to read it. Download

Citation Tools

Cite this article, export the record for this article.

RIS EndNote, Papers, Reference Manager, RefWorks, Zotero

ENW EndNote (version X9.1 and above), Zotero

BIB BibTeX, JabRef, Mendeley, Zotero

Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

OWL Conversations

OWL Conversations are essays, arguments, interviews, think pieces, and other forms of media that don't fit elsewhere on the site. By sharing these conversations, the OWL aims to start an open dialogue about the ways that writing is discussed, studied, taught, and performed today.

This page contains a record of all conversations that have been published thus far. New links will be added as pages are published.

Summer 2020

Remote Teaching: a Student's Perspective (Essay)

Remote Teaching: an Instructor's Perspective (Essay)

Spring 2019

Dr. Margie Berns (Interview)

The Myth of the Good Writer (Essay)

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

Margin Size

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

1.7: Research Writing as Conversation

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 7499

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

Writing is a social process. Texts are created to be read by others, and in creating those texts, writers should be aware of not only their personal assumptions, biases, and tastes, but also those of their readers. Writing, therefore, is an interactive process. It is a conversation, a meeting of minds, during which ideas are exchanged, debates and discussions take place and, sometimes, but not always, consensus is reached. You may be familiar with the famous quote by the 20th century rhetorician Kenneth Burke who compared writing to a conversation at a social event. In his 1974 book The Philosophy of Literary Form Burke writes,

Imagine that you enter a parlor. You come late. When you arrive, others have long preceded you, and they are engaged in a heated discussion, a discussion too heated for them to pause and tell you exactly what it is about. In fact, the discussion had already begun long before any of them got there, so that no one present is qualified to retrace for you all the steps that had gone before. You listen for a while, until you decide that you have caught the tenor of the argument; then you put in your oar. Someone answers; you answer him, another comes to your defense; another aligns himself against you, to either the embarrassment of gratification of your opponent, depending upon the quality of your ally's assistance. However, the discussion is interminable. The hour grows late, you must depart. And you do depart, with the discussion still vigorously in progress (110-111).

This passage by Burke is extremely popular among writers because it captures the interactive nature of writing so precisely. Reading Burke’s words carefully, we will notice that the interaction between readers and writers is continuous. A writer always enters a conversation in progress. In order to participate in the discussion, just like in real life, you need to know what your interlocutors have been talking about. So you listen (read). Once you feel you have got the drift of the conversation, you say (write) something. Your text is read by others who respond to your ideas, stories, and arguments with their own. This interaction never ends! To write well, it is important to listen carefully and understand the conversations that are going on around you. Writers who are able to listen to these conversations and pick up important topics, themes, and arguments are generally more effective at reaching and impressing their audiences. It is also important to treat research, writing, and every occasion for these activities as opportunities to participate in the on-going conversation of people interested in the same topics and questions which interest you. Our knowledge about our world is shaped by the best and most up-to-date theories available to them. Sometimes these theories can be experimentally tested and proven, and sometimes, when obtaining such proof is impossible, they are based on consensus reached as a result of conversation and debate. Even the theories and knowledge that can be experimentally tested (for example in sciences) do not become accepted knowledge until most members of the scientific community accept them. Other members of this community will help them test their theories and hypotheses, give them feedback on their writing, and keep them searching for the best answers to their questions. As Burke says in his famous passage, the interaction between the members of intellectual communities never ends. No piece of writing, no argument, no theory or discover is ever final. Instead, they all are subject to discussion, questioning, and improvement. A simple but useful example of this process is the evolution of humankind’s understanding of their planet Earth and its place in the Universe. As you know, in Medieval Europe, the prevailing theory was that the Earth was the center of the Universe and that all other planets and the Sun rotated around it. This theory was the result of the church’s teachings, and thinkers who disagreed with it were pronounced heretics and often burned. In 1543, astronomer Nikolaus Kopernikus argued that the Sun was at the center of the solar system and that all planets of the system rotate around the Sun. Later, Galieo experimentally proved Kopernikus’ theory with the help of a telescope. Of course, the Earch did not begin to rotate around the Sun with this discovery. Yet, Kopernikus’ and Galileo’s theories of the Universe went against the Catholic Church’s teachings which dominated the social discourse of Medieval Europe. The Inquisition did not engage in debate with the two scientists. Instead, Kopernikus was executed for his views and Galileo was sentenced to house arrest for his views. Although in the modern world, dissenting thinkers are unlikely to suffer such harsh punishment, the examples of Kopernikus and Galileo teach us two valuable lessons about the social nature of knowledge. Firstly, Both Kopernikus and Galileo tried to improve on an existing theory of the Universe that placed our planet at the center. They did not work from nothing but used beliefs that already existed in their society and tried to modify and disprove those beliefs. Time and later scientific research proved that they were right. Secondly, even after Galileo was able to prove the structure of the Solar system experimentally, his theory did not become widely accepted until the majority of people in society assimilated it. Therefore, new findings do not become accepted knowledge until they penetrate the fabric of social discourse and until enough people accept them as true.

Complete " Writing Activity 1E: Finding the Origins of Knowledge " in the "Writing Activities" section of this chapter.

Writing Dialogue [20 Best Examples + Formatting Guide]

Have you ever found yourself cringing at clunky dialogue while reading a book or watching a movie? I know I have.

It’s like nails on a chalkboard, completely ruining the experience. But on the flip side, well-written dialogue can transform a story. It’s the magic that makes characters leap off the page, immersing us in their world.

As a writer, I’m fascinated by the mechanics of great dialogue.

So here are 20 of the best examples of writing dialogue that brings your story to life.

Example 1: Dialogue that Reveals Character

Table of Contents

One of the most powerful functions of dialogue is to shed light on your characters’ personalities.

The way they speak – their word choice, tone, even their hesitations – can tell us so much about who they are. Check out this example:

“Look, I ain’t gonna sugarcoat this,” the detective growled, his knuckles whitening as he gripped the chair. “You were spotted leaving the scene, and the murder weapon’s got your prints all over it.”

Without any lengthy description, we get a sense of this detective as a no-nonsense, direct type of guy.

Example 2: Dialogue that Builds Tension

Dialogue can become this amazing tool to ratchet up the tension in a scene.

Short, clipped exchanges and carefully placed silences can leave the reader on the edge of their seat.

Here’s how it might play out:

“Do you hear that?” Sarah whispered. “Hear what?” A scratching noise echoed from the attic. Sarah’s eyes widened. “It’s coming back.”

The suspense is killing me just writing that!

Example 3: Dialogue that Drives the Plot

Conversations aren’t just about characters sitting around and chatting.

Great dialogue should actively push the story forward. It can set up a conflict, reveal key information, or change the course of events.

Take a look at this:

“I’ve made my decision,” the king declared, the crown heavy on his brow. “We go to war.”

A single line, and the whole trajectory of the story shifts.

Formatting Tips: The Basics

Now, before we get carried away, let’s cover some essential dialogue formatting rules.

Think of these as the grammar of a good conversation.

- Quotation Marks: Yep, those little squiggles are your best friend. They signal to the reader: “Hey! Someone’s talking!”

- New Speaker, New Paragraph: Whenever a different character starts talking, give them a new paragraph. It’s all about keeping things easy to follow.

- Dialogue Tags: These are the little phrases like “he said” or “she replied.” Use them, but try not to overuse them. A well-placed action beat can often do a better job of showing who’s speaking.

Example 4: Dialogue that Creates Humor

Dialogue can be ridiculously funny when done well.

The key? Snappy exchanges, playful misunderstandings, and just a dash of absurdity. Consider this:

“I saw the weirdest thing at the grocery store today,” Tom said, “A woman arguing with a head of lettuce.” “Was she winning?” Lily asked, a grin playing on her lips.

You can almost hear the deadpan delivery, can’t you?

Example 5: Dialogue that Shows Relationships

The way characters speak to each other says a ton about the dynamics between them.

Is there warmth, hostility, an underlying power struggle? Dialogue can paint a crystal-clear picture. Imagine this exchange:

“You didn’t do the dishes again?” Sarah sighed, hands planted on her hips. “Aw, c’mon babe. I was busy,” Mike whined, avoiding her gaze.

We instantly sense the long-suffering tone from Sarah and the playful guilt from Mike.

Example 6: Dialogue with Subtext

The most interesting dialogue often has layers. What the characters say might not be exactly what they mean.

This is where subtext comes in – the unspoken thoughts and feelings bubbling beneath the surface.

Take this snippet:

“It’s a nice ring,” Emily said, her voice flat. “You don’t like it?” Mark’s brow furrowed. Emily shrugged. “It’s fine.”

Is Emily truly indifferent? Or is she masking disappointment, perhaps a sense of something not being quite right? Subtext makes us read between the lines.

Formatting Tips: Getting Fancy

Now, let’s spice things up with a few more advanced formatting tricks:

- Ellipses (…): These little dots are perfect for showing a character trailing off, hesitating, or searching for words. Example: “I…I don’t know what to say.”

- Em Dashes (—): These guys can interrupt a thought or indicate a sudden change in direction. Example: “I was going to apologize, but then — well, you’re still being a jerk.”

- Internal Dialogue: Instead of quotation marks, sometimes you’ll want to italicize a character’s inner thoughts. Example: Why did I say that? I’m such an idiot.

Cautionary Note

It’s important to remember: dialogue shouldn’t feel like an interrogation. Avoid rigid “question-answer, question-answer” patterns. Real conversations flow and meander naturally.

Example 7: Dialogue with Dialects and Accents

Regional dialects and accents can bring so much flavor to your characters, but it’s a delicate balance.

You want to add authenticity without it becoming a caricature or making it hard to understand.

Here’s a subtle example:

“Well, I’ll be darned,” drawled the farmer, squinting at the sky. “Looks like a storm’s brewin’.”

Notice how just a few word choices and a slight change in pronunciation hint at the speaker’s background.

Example 8: Dialogue in Groups

Writing conversations with more than two people can get chaotic fast. The key is clarity.

Here are a few tips:

- Strong Dialogue Tags: Sometimes, you need to be more specific than just “he said” or “she said”. Example: “Don’t be ridiculous,” scoffed Sarah.

- Action Beats: Break up chunks of dialogue with actions that show who’s speaking. Example: Tom slammed his fist on the table. “I won’t stand for this!”

Example 9: Dialogue Over the Phone (or Other Technology)

Conversations where characters aren’t physically together pose unique challenges.

You can’t rely on body language cues. Instead, focus on conveying tone and potential misunderstandings.

For instance:

“Hello?” Sarah’s voice crackled through the phone. A long pause. “Sarah, is that you?” “Mom? Why are you whispering?”

Instantly there’s a sense of distance and something not being quite right.

Example 10: Inner Monologue with a Twist

We often think of internal dialogue as a single character reflecting, but sometimes our inner voices can argue.

This can be a powerful way to showcase internal conflict.

Here’s how it might look:

You should just tell him how you feel, one voice chimed. Are you crazy? the other shrieked back. He’ll never feel the same way .

This creates a vivid picture of a character torn between opposing desires.

Example 11: Dialogue With a Manipulative Character

Manipulative characters often use language as a weapon.

They might use guilt trips, flattery, or veiled threats to get what they want.

Consider this:

“After everything I’ve done for you…” The old woman sighed, a flicker of disappointment in her eyes. “Well, I guess I shouldn’t expect gratitude.”

Notice how she doesn’t directly ask for anything, instead hinting at a debt, leaving the listener feeling uneasy and obligated.

Example 12: Dialogue Across Time Periods

If you’re writing historical fiction or anything with time travel elements, you’ll need to capture the distinct speech patterns of different eras.

Imagine this exchange:

“Gadzooks! What manner of contraption is this?” The Victorian gentleman exclaimed, staring in bewilderment at the smartphone. “It’s a phone,” the teenager replied, barely suppressing a laugh. “Let me show you.”

This little snippet highlights the potential for both humor and linguistic challenges when worlds collide.

Formatting Tip: Dialogue Without Tags

Sometimes, for a rapid-fire or dreamlike effect, you might want to ditch the “he said” or “she asked” altogether.

It’s a bold move, but it can be effective if done sparingly.

Check this out:

“Where are you going?” “Away.” “When will you be back?” “I don’t know.” “Please don’t leave me.”

This creates a sense of urgency, the raw exchange forcing us to focus solely on the words themselves.

Example 13: Dialogue that Shows Transformation

A great way to showcase how a character develops is through shifts in how they speak.

Maybe they become bolder, quieter, or their vocabulary changes.

Let’s see an example:

Scene 1: “I-I don’t know,” Emily whimpered, cowering in the corner. Scene 2 (Later in the story): “That’s it. I’m not taking this anymore!” Emily declared, her chin held high.

The dialogue itself reflects her transformation from victim to someone ready to stand up for herself.

Example 14: Dialogue that’s Just Plain Weird

It’s okay to get strange sometimes.

Absurdist humor or unsettling conversations can add a unique flavor to your story. Just be sure it fits the overall tone.

“Do you believe in cucumbers?” the man asked, his eyes wide and unblinking. “Excuse me?” “Cucumbers, my dear. Agents of the underground vegetable kingdom.”

This immediately creates a sense of oddness and perhaps a touch of unease. Is this guy crazy, or is there something more going on?

Example 15: Dialogue with a Purpose

Remember, good dialogue isn’t just about being entertaining.

It should move your story along. Here are some functions dialogue can serve:

- Providing Exposition: Sometimes, you need to inform the reader of backstory or world-building details. Trickle information through natural conversation rather than an information dump.

- Foreshadowing: Subtle hints within a conversation can foreshadow future events or create a sense of unease for the reader.

- Revealing a Twist: A single line of dialogue can completely flip the script and reframe everything that came before.

Example 16: Dialogue with Non-Verbal Elements

So much of communication happens beyond just words.

Sighs, laughs, and gestures can add richness to dialogue on the page.

“I’m fine,” she said, crossing her arms and looking away.

Notice how the body language contradicts her words, hinting at inner turmoil.

Example 17: Silence as Dialogue

Sometimes, what isn’t said is the most powerful thing of all.

A pregnant pause or a character refusing to speak can convey volumes.

Imagine this:

“So, will you help me or not?” Tom pleaded. Sarah stared at him, her lips a thin line. Finally, she turned and walked away.

The lack of a verbal response speaks louder than any words could.

Example 18: Dialogue With Humorous Effect

A well-timed O.S. voice can deliver a funny remark or punchline, undercutting the seriousness of a scene or taking a moment in an unexpected comedic direction.

INT. CLASSROOM – DAY The teacher drones on about the causes of the American Revolution, his voice as dull as the worn textbook in front of him. KEVIN tries to stifle his yawns, failing miserably. STUDENT (O.S.) Is he ever going to stop talking? My brain just turned to mush. Snickers ripple through the class. The teacher pauses, a look of annoyance flickering across his face. Kevin shoots a desperate look towards the source of the O.S. voice.

- Timing is everything. The best comedic O.S. lines act as a witty reaction to something else happening in a scene. The student’s comment comes right as Kevin’s boredom peaks.

- Subverting expectations is funny. The audience expects the scene to continue with a stern reprimand for speaking out of turn, but the script doesn’t give us that. This leaves room for further humor.

- Consider the tone of the voice – sarcastic, matter-of-fact, or outright whiny? This adds to the comedic effect.

Example 19: Dialogue With Unexpected Reveals

Think of this as a surprise twist using O.S. dialogue.

The audience (and maybe even some characters) are led to believe one thing, only for an O.S. voice to reveal something completely unexpected, shifting the scene’s dynamic.

INT. POLICE INTERROGATION ROOM – NIGHTDETECTIVE HARRIS paces in front of a nervous SUSPECT. Photos of the crime scene are scattered on the table. HARRIS Don’t lie to me! We’ve got witnesses who saw you at the scene. SUSPECT I – I swear, I had nothing to do with it! I was… I was with my girlfriend. Harris leans in, a triumphant glint in her eyes. She claps her hands sharply, startling the suspect. WOMAN (O.S.) That’s a lie! He was nowhere near me last night! The suspect whips around. His face pales as we hear the sound of the interrogation room door swinging open…

- The power lies in the build-up. The initial dialogue and the characters’ reactions should lead the audience to believe one outcome, making the O.S. interruption all the more impactful.

- Consider who speaks the O.S. line. Is it someone the audience recognizes, or a totally new character whose identity becomes a new mystery?

- Play with the proximity of the voice. Is it right outside the room, adding to the dramatic reveal as the door opens, or is it more distant – perhaps a voice over an intercom – for an even more unsettling effect?

Example 20: Dialogue With a “Haunted” Feeling

Explanation: O.S. can be used to create an eerie or unsettling atmosphere, particularly in horror or psychological thrillers. This could be unexplained voices, creepy whispers, or sounds that hint at a supernatural (or simply unnerving) presence.

INT. OLD MANSION – NIGHTSARAH explores the abandoned mansion, flashlight cutting through the thick dust. Cobwebs cling to every surface. A faint WHISPER drifts through the air, seeming to come from everywhere at once. Sarah freezes. VOICE (O.S.) Get out… leave this place… Sarah’s breath catches in her throat. She hesitantly follows the direction of the voice, her flashlight beam trembling.

- Less is more. The vaguer and more inexplicable the O.S. voice, the more chilling it becomes.

- Layer sounds for a full creepy effect. Combine whispers with unexpected bangs, creaks, or the faint sound of footsteps following behind Sarah.

- Play with audience expectations. If the script initially leads the audience to think the house is merely abandoned, the O.S. voices become that much more terrifying.

Here is a good video about writing dialogue:

Additional Dialogue Tips & Tricks

- Read Your Dialogue Aloud: This is the best way to catch awkward phrasing or unnatural rhythms. Our ears often pick up on what our eyes might miss.

- Less is More: Don’t feel the need to have every single interaction be profound. Sometimes a simple “Hey” or “Thanks” can do the job just fine.

- Eavesdrop: Paying attention to real-life conversations is fantastic research. Note the pauses, the filler words, the way people interrupt each other.

Final Thoughts: Writing Dialogue

Phew! We did it!

Does that feel like a solid collection of dialogue examples? We haven’t covered absolutely every scenario, but I hope these illustrate the vast potential within dialogue to bring your stories to life.

Read This Next:

- How To Use Action Tags in Dialogue: Ultimate Guide

- How Do Writers Fill a Natural Pause in Dialogue? [7 Crazy Effective Ways]

- Can You Start a Novel with Dialogue?

- How To Write A Southern Accent (17 Tips + Examples)

- How to Write a French Accent (13 Best Tips with Examples)

VIDEO COURSE

Finish your draft in our 3-month master class. Sign up now to watch a free lesson!

Learn How to Write a Novel

Finish your draft in our 3-month master class. Enroll now for daily lessons, weekly critique, and live events. Your first lesson is free!

Guides • Perfecting your Craft

Last updated on Jul 24, 2023

15 Examples of Great Dialogue (And Why They Work So Well)

Great dialogue is hard to pin down, but you know it when you hear or see it. In the earlier parts of this guide, we showed you some well-known tips and rules for writing dialogue. In this section, we'll show you those rules in action with 15 examples of great dialogue, breaking down exactly why they work so well.

1. Barbara Kingsolver, Unsheltered

In the opening of Barbara Kingsolver’s Unsheltered, we meet Willa Knox, a middle-aged and newly unemployed writer who has just inherited a ramshackle house.

“The simplest thing would be to tear it down,” the man said. “The house is a shambles.” She took this news as a blood-rush to the ears: a roar of peasant ancestors with rocks in their fists, facing the evictor. But this man was a contractor. Willa had called him here and she could send him away. She waited out her panic while he stood looking at her shambles, appearing to nurse some satisfaction from his diagnosis. She picked out words. “It’s not a living thing. You can’t just pronounce it dead. Anything that goes wrong with a structure can be replaced with another structure. Am I right?” “Correct. What I am saying is that the structure needing to be replaced is all of it. I’m sorry. Your foundation is nonexistent.”

Alfred Hitchcock once described drama as "life with the boring bits cut out." In this passage, Kingsolver cuts out the boring parts of Willa's conversation with her contractor and brings us right to the tensest, most interesting part of the conversation.

By entering their conversation late , the reader is spared every tedious detail of their interaction.

Instead of a blow-by-blow account of their negotiations (what she needs done, when he’s free, how she’ll be paying), we’re dropped right into the emotional heart of the discussion. The novel opens with the narrator learning that the home she cherishes can’t be salvaged.

By starting off in the middle of (relatively obscure) dialogue, it takes a moment for the reader to orient themselves in the story and figure out who is speaking, and what they’re speaking about. This disorientation almost mirrors Willa’s own reaction to the bad news, as her expectations for a new life in her new home are swiftly undermined.

FREE COURSE

How to Write Believable Dialogue

Master the art of dialogue in 10 five-minute lessons.

2. Jane Austen, Pride and Prejudice

In the first piece of dialogue in Pride and Prejudice , we meet Mr and Mrs Bennet, as Mrs Bennet attempts to draw her husband into a conversation about neighborhood gossip.

“My dear Mr. Bennet,” said his lady to him one day, “have you heard that Netherfield Park is let at last?” Mr. Bennet replied that he had not. “But it is,” returned she; “for Mrs. Long has just been here, and she told me all about it.” Mr. Bennet made no answer. “Do you not want to know who has taken it?” cried his wife impatiently. “You want to tell me, and I have no objection to hearing it.” This was invitation enough. “Why, my dear, you must know, Mrs. Long says that Netherfield is taken by a young man of large fortune from the north of England; that he came down on Monday in a chaise and four to see the place, and was so much delighted with it, that he agreed with Mr. Morris immediately; that he is to take possession before Michaelmas, and some of his servants are to be in the house by the end of next week.”

Austen’s dialogue is always witty, subtle, and packed with character. This extract from Pride and Prejudice is a great example of dialogue being used to develop character relationships .

We instantly learn everything we need to know about the dynamic between Mr and Mrs Bennet’s from their first interaction: she’s chatty, and he’s the beleaguered listener who has learned to entertain her idle gossip, if only for his own sake (hence “you want to tell me, and I have no objection to hearing it”).

There is even a clear difference between the two characters visually on the page: Mr Bennet responds in short sentences, in simple indirect speech, or not at all, but this is “invitation enough” for Mrs Bennet to launch into a rambling and extended response, dominating the conversation in text just as she does audibly.

The fact that Austen manages to imbue her dialogue with so much character-building realism means we hardly notice the amount of crucial plot exposition she has packed in here. This heavily expository dialogue could be a drag to get through, but Austen’s colorful characterization means she slips it under the radar with ease, forwarding both our understanding of these people and the world they live in simultaneously.

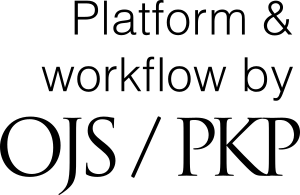

3. Naomi Alderman, The Power

In The Power , young women around the world suddenly find themselves capable of generating and controlling electricity. In this passage, between two boys and a girl who just used those powers to light her cigarette.

Kyle gestures with his chin and says, “Heard a bunch of guys killed a girl in Nebraska last week for doing that.” “For smoking? Harsh.” Hunter says, “Half the kids in school know you can do it.” “So what?” Hunter says, “Your dad could use you in his factory. Save money on electricity.” “He’s not my dad.” She makes the silver flicker at the ends of her fingers again. The boys watch.

Alderman here uses a show, don’t tell approach to expositional dialogue. Within this short exchange, we discover a lot about Allie, her personal circumstances, and the developing situation elsewhere. We learn that women are being punished harshly for their powers; that Allie is expected to be ashamed of those powers and keep them a secret, but doesn’t seem to care to do so; that her father is successful in industry; and that she has a difficult relationship with him. Using dialogue in this way prevents info-dumping backstory all at once, and instead helps us learn about the novel’s world in a natural way.

Show, Don't Tell

Master the golden rule of writing in 10 five-minute lessons.

4. Kazuo Ishiguro, Never Let Me Go

Here, friends Tommy and Kathy have a conversation after Tommy has had a meltdown. After being bullied by a group of boys, he has been stomping around in the mud, the precise reaction they were hoping to evoke from him.

“Tommy,” I said, quite sternly. “There’s mud all over your shirt.” “So what?” he mumbled. But even as he said this, he looked down and noticed the brown specks, and only just stopped himself crying out in alarm. Then I saw the surprise register on his face that I should know about his feelings for the polo shirt. “It’s nothing to worry about.” I said, before the silence got humiliating for him. “It’ll come off. If you can’t get it off yourself, just take it to Miss Jody.” He went on examining his shirt, then said grumpily, “It’s nothing to do with you anyway.”

This episode from Never Let Me Go highlights the power of interspersing action beats within dialogue. These action beats work in several ways to add depth to what would otherwise be a very simple and fairly nondescript exchange. Firstly, they draw attention to the polo shirt, and highlight its potential significance in the plot. Secondly, they help to further define Kathy’s relationship with Tommy.

We learn through Tommy’s surprised reaction that he didn’t think Kathy knew how much he loved his seemingly generic polo shirt. This moment of recognition allows us to see that she cares for him and understands him more deeply than even he realized. Kathy breaking the silence before it can “humiliate” Tommy further emphasizes her consideration for him. While the dialogue alone might make us think Kathy is downplaying his concerns with pragmatic advice, it is the action beats that tell the true story here.

5. J R R Tolkien, The Hobbit

The eponymous hobbit Bilbo is engaged in a game of riddles with the strange creature Gollum.

"What have I got in my pocket?" he said aloud. He was talking to himself, but Gollum thought it was a riddle, and he was frightfully upset. "Not fair! not fair!" he hissed. "It isn't fair, my precious, is it, to ask us what it's got in its nassty little pocketses?" Bilbo seeing what had happened and having nothing better to ask stuck to his question. "What have I got in my pocket?" he said louder. "S-s-s-s-s," hissed Gollum. "It must give us three guesseses, my precious, three guesseses." "Very well! Guess away!" said Bilbo. "Handses!" said Gollum. "Wrong," said Bilbo, who had luckily just taken his hand out again. "Guess again!" "S-s-s-s-s," said Gollum, more upset than ever.

Tolkein’s dialogue for Gollum is a masterclass in creating distinct character voices . By using a repeated catchphrase (“my precious”) and unconventional spelling and grammar to reflect his unusual speech pattern, Tolkien creates an idiosyncratic, unique (and iconic) speech for Gollum. This vivid approach to formatting dialogue, which is almost a transliteration of Gollum's sounds, allows readers to imagine his speech pattern and practically hear it aloud.

We wouldn’t recommend using this extreme level of idiosyncrasy too often in your writing — it can get wearing for readers after a while, and Tolkien deploys it sparingly, as Gollum’s appearances are limited to a handful of scenes. However, you can use Tolkien’s approach as inspiration to create (slightly more subtle) quirks of speech for your own characters.

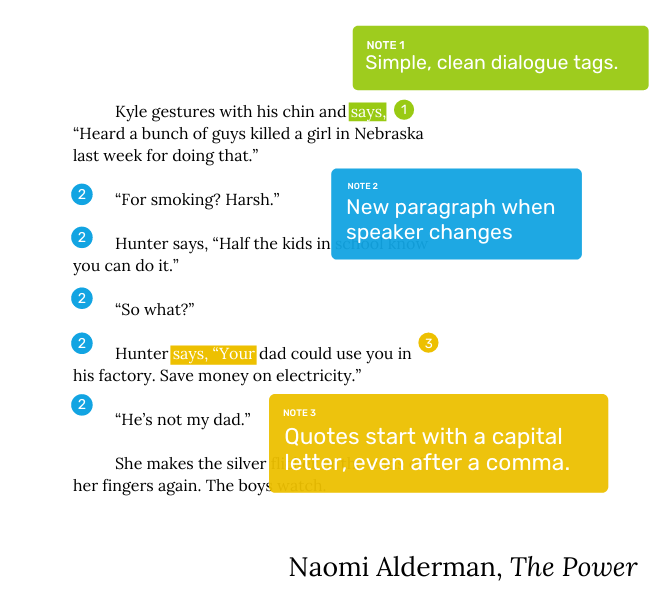

6. F Scott Fitzgerald, The Great Gatsby

The narrator, Nick has just done his new neighbour Gatsby a favor by inviting his beloved Daisy over to tea. Perhaps in return, Gatsby then attempts to make a shady business proposition.

“There’s another little thing,” he said uncertainly, and hesitated. “Would you rather put it off for a few days?” I asked. “Oh, it isn’t about that. At least —” He fumbled with a series of beginnings. “Why, I thought — why, look here, old sport, you don’t make much money, do you?” “Not very much.” This seemed to reassure him and he continued more confidently. “I thought you didn’t, if you’ll pardon my — you see, I carry on a little business on the side, a little side line, if you understand. And I thought that if you don’t make very much — You’re selling bonds, aren’t you, old sport?” “Trying to.”

This dialogue from The Great Gatsby is a great example of how to make dialogue sound natural. Gatsby tripping over his own words (even interrupting himself , as marked by the em-dashes) not only makes his nerves and awkwardness palpable but also mimics real speech. Just as real people often falter and make false starts when they’re speaking off the cuff, Gatsby too flounders, giving us insight into his self-doubt; his speech isn’t polished and perfect, and neither is he despite all his efforts to appear so.

Fitzgerald also creates a distinctive voice for Gatsby by littering his speech with the character's signature term of endearment, “old sport”. We don’t even really need dialogue markers to know who’s speaking here — a sign of very strong characterization through dialogue.

7. Arthur Conan Doyle, A Study in Scarlet

In this first meeting between the two heroes of Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes stories, Sherlock Holmes and John Watson, John is introduced to Sherlock while the latter is hard at work in the lab.

“How are you?” he said cordially, gripping my hand with a strength for which I should hardly have given him credit. “You have been in Afghanistan, I perceive.” “How on earth did you know that?” I asked in astonishment. “Never mind,” said he, chuckling to himself. “The question now is about hemoglobin. No doubt you see the significance of this discovery of mine?” “It is interesting, chemically, no doubt,” I answered, “but practically— ” “Why, man, it is the most practical medico-legal discovery for years. Don’t you see that it gives us an infallible test for blood stains. Come over here now!” He seized me by the coat-sleeve in his eagerness, and drew me over to the table at which he had been working. “Let us have some fresh blood,” he said, digging a long bodkin into his finger, and drawing off the resulting drop of blood in a chemical pipette. “Now, I add this small quantity of blood to a litre of water. You perceive that the resulting mixture has the appearance of pure water. The proportion of blood cannot be more than one in a million. I have no doubt, however, that we shall be able to obtain the characteristic reaction.” As he spoke, he threw into the vessel a few white crystals, and then added some drops of a transparent fluid. In an instant the contents assumed a dull mahogany colour, and a brownish dust was precipitated to the bottom of the glass jar. “Ha! ha!” he cried, clapping his hands, and looking as delighted as a child with a new toy. “What do you think of that?”

This passage uses a number of the key techniques for writing naturalistic and exciting dialogue, including characters speaking over one another and the interspersal of action beats.

Sherlock cutting off Watson to launch into a monologue about his blood experiment shows immediately where Sherlock’s interest lies — not in small talk, or the person he is speaking to, but in his own pursuits, just like earlier in the conversation when he refuses to explain anything to John and is instead self-absorbedly “chuckling to himself”. This helps establish their initial rapport (or lack thereof) very quickly.

Breaking up that monologue with snippets of him undertaking the forensic tests allows us to experience the full force of his enthusiasm over it without having to read an uninterrupted speech about the ins and outs of a science experiment.

Starting to think you might like to read some Sherlock? Check out our guide to the Sherlock Holmes canon !

8. Brandon Taylor, Real Life

Here, our protagonist Wallace is questioned by Ramon, a friend-of-a-friend, over the fact that he is considering leaving his PhD program.

Wallace hums. “I mean, I wouldn’t say that I want to leave, but I’ve thought about it, sure.” “Why would you do that? I mean, the prospects for… black people, you know?” “What are the prospects for black people?” Wallace asks, though he knows he will be considered the aggressor for this question.

Brandon Taylor’s Real Life is drawn from the author’s own experiences as a queer Black man, attempting to navigate the unwelcoming world of academia, navigating the world of academia, and so it’s no surprise that his dialogue rings so true to life — it’s one of the reasons the novel is one of our picks for must-read books by Black authors .

This episode is part of a pattern where Wallace is casually cornered and questioned by people who never question for a moment whether they have the right to ambush him or criticize his choices. The use of indirect dialogue at the end shows us this is a well-trodden path for Wallace: he has had this same conversation several times, and can pre-empt the exact outcome.

This scene is also a great example of the dramatic significance of people choosing not to speak. The exchange happens in front of a big group, but — despite their apparent discomfort — nobody speaks up to defend Wallace, or to criticize Ramon’s patronizing microaggressions. Their silence is deafening, and we get a glimpse of Ramon’s isolation due to the complacency of others, all due to what is not said in this dialogue example.

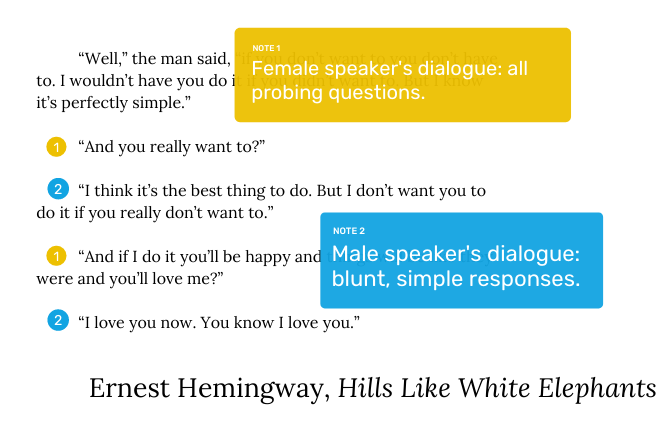

9. Ernest Hemingway, Hills Like White Elephants

In this short story, an unnamed man and a young woman discuss whether or not they should terminate a pregnancy while sitting on a train platform.

“Well,” the man said, “if you don’t want to you don’t have to. I wouldn’t have you do it if you didn’t want to. But I know it’s perfectly simple.” “And you really want to?” “I think it’s the best thing to do. But I don’t want you to do it if you really don’t want to.” “And if I do it you’ll be happy and things will be like they were and you’ll love me?” “I love you now. You know I love you.” “I know. But if I do it, then it will be nice again if I say things are like white elephants, and you’ll like it?” “I’ll love it. I love it now but I just can’t think about it. You know how I get when I worry.” “If I do it you won’t ever worry?” “I won’t worry about that because it’s perfectly simple.”

This example of dialogue from Hemingway’s short story Hills Like White Elephants moves at quite a clip. The conversation quickly bounces back and forth between the speakers, and the call-and-response format of the woman asking and the man answering is effective because it establishes a clear dynamic between the two speakers: the woman is the one seeking reassurance and trying to understand the man’s feelings, while he is the one who is ultimately in control of the situation.

Note the sparing use of dialogue markers: this minimalist approach keeps the dialogue brisk, and we can still easily understand who is who due to the use of a new paragraph when the speaker changes .

Like this classic author’s style? Head over to our selection of the 11 best Ernest Hemingway books .

10. Madeline Miller, Circe

In Madeline Miller’s retelling of Greek myth, we witness a conversation between the mythical enchantress Circe and Telemachus (son of Odysseus).

“You do not grieve for your father?” “I do. I grieve that I never met the father everyone told me I had.” I narrowed my eyes. “Explain.” “I am no storyteller.” “I am not asking for a story. You have come to my island. You owe me truth.” A moment passed, and then he nodded. “You will have it.”

This short and punchy exchange hits on a lot of the stylistic points we’ve covered so far. The conversation is a taut tennis match between the two speakers as they volley back and forth with short but impactful sentences, and unnecessary dialogue tags have been shaved off . It also highlights Circe’s imperious attitude, a result of her divine status. Her use of short, snappy declaratives and imperatives demonstrates that she’s used to getting her own way and feels no need to mince her words.

11. Andre Aciman, Call Me By Your Name

This is an early conversation between seventeen-year-old Elio and his family’s handsome new student lodger, Oliver.

What did one do around here? Nothing. Wait for summer to end. What did one do in the winter, then? I smiled at the answer I was about to give. He got the gist and said, “Don’t tell me: wait for summer to come, right?” I liked having my mind read. He’d pick up on dinner drudgery sooner than those before him. “Actually, in the winter the place gets very gray and dark. We come for Christmas. Otherwise it’s a ghost town.” “And what else do you do here at Christmas besides roast chestnuts and drink eggnog?” He was teasing. I offered the same smile as before. He understood, said nothing, we laughed. He asked what I did. I played tennis. Swam. Went out at night. Jogged. Transcribed music. Read. He said he jogged too. Early in the morning. Where did one jog around here? Along the promenade, mostly. I could show him if he wanted. It hit me in the face just when I was starting to like him again: “Later, maybe.”

Dialogue is one of the most crucial aspects of writing romance — what’s a literary relationship without some flirty lines? Here, however, Aciman gives us a great example of efficient dialogue. By removing unnecessary dialogue and instead summarizing with narration, he’s able to confer the gist of the conversation without slowing down the pace unnecessarily. Instead, the emphasis is left on what’s unsaid, the developing romantic subtext.

Furthermore, the fact that we receive this scene in half-reported snippets rather than as an uninterrupted transcript emphasizes the fact that this is Elio’s own recollection of the story, as the manipulation of the dialogue in this way serves to mimic the nostalgic haziness of memory.

Understanding Point of View

Learn to master different POVs and choose the best for your story.

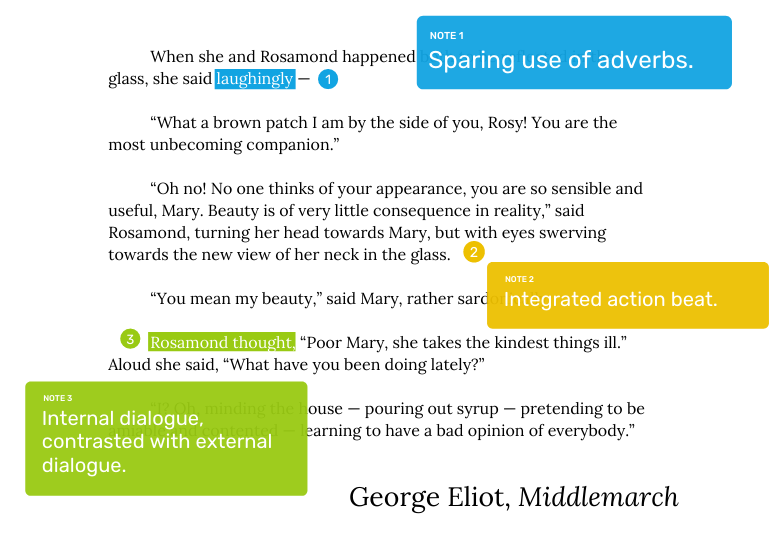

12. George Eliot, Middlemarch

Two of Eliot’s characters, Mary and Rosamond, are out shopping,

When she and Rosamond happened both to be reflected in the glass, she said laughingly — “What a brown patch I am by the side of you, Rosy! You are the most unbecoming companion.” “Oh no! No one thinks of your appearance, you are so sensible and useful, Mary. Beauty is of very little consequence in reality,” said Rosamond, turning her head towards Mary, but with eyes swerving towards the new view of her neck in the glass. “You mean my beauty,” said Mary, rather sardonically. Rosamond thought, “Poor Mary, she takes the kindest things ill.” Aloud she said, “What have you been doing lately?” “I? Oh, minding the house — pouring out syrup — pretending to be amiable and contented — learning to have a bad opinion of everybody.”

This excerpt, a conversation between the level-headed Mary and vain Rosamond, is an example of dialogue that develops character relationships naturally. Action descriptors allow us to understand what is really happening in the conversation.

Whilst the speech alone might lead us to believe Rosamond is honestly (if clumsily) engaging with her friend, the description of her simultaneously gazing at herself in a mirror gives us insight not only into her vanity, but also into the fact that she is not really engaged in her conversation with Mary at all.

The use of internal dialogue cut into the conversation (here formatted with quotation marks rather than the usual italics ) lets us know what Rosamond is actually thinking, and the contrast between this and what she says aloud is telling. The fact that we know she privately realizes she has offended Mary, but quickly continues the conversation rather than apologizing, is emphatic of her character. We get to know Rosamond very well within this short passage, which is a hallmark of effective character-driven dialogue.

13. John Steinbeck, The Winter of our Discontent

Here, Mary (speaking first) reacts to her husband Ethan’s attempts to discuss his previous experiences as a disciplined soldier, his struggles in subsequent life, and his feeling of impending change.

“You’re trying to tell me something.” “Sadly enough, I am. And it sounds in my ears like an apology. I hope it is not.” “I’m going to set out lunch.”

Steinbeck’s Winter of our Discontent is an acute study of alienation and miscommunication, and this exchange exemplifies the ways in which characters can fail to communicate, even when they’re speaking. The pair speaking here are trapped in a dysfunctional marriage which leaves Ethan feeling isolated, and part of his loneliness comes from the accumulation of exchanges such as this one. Whenever he tries to communicate meaningfully with his wife, she shuts the conversation down with a complete non sequitur.

We expect Mary’s “you’re trying to tell me something” to be followed by a revelation, but Ethan is not forthcoming in his response, and Mary then exits the conversation entirely. Nothing is communicated, and the jarring and frustrating effect of having our expectations subverted goes a long way in mirroring Ethan’s own frustration.

Just like Ethan and Mary, we receive no emotional pay-off, and this passage of characters talking past one another doesn’t further the plot as we hope it might, but instead gives us insight into the extent of these characters’ estrangement.

14. Bret Easton Ellis , Less Than Zero

The disillusioned main character of Bret Easton Ellis’ debut novel, Clay, here catches up with a college friend, Daniel, whom he hasn’t seen in a while.

He keeps rubbing his mouth and when I realize that he’s not going to answer me, I ask him what he’s been doing. “Been doing?” “Yeah.” “Hanging out.” “Hanging out where?” “Where? Around.”

Less Than Zero is an elegy to conversation, and this dialogue is an example of the many vacuous exchanges the protagonist engages in, seemingly just to fill time. The whole book is deliberately unpoetic and flat, and depicts the lives of disaffected youths in 1980s LA. Their misguided attempts to fill the emptiness within them with drink and drugs are ultimately fruitless, and it shows in their conversations: in truth, they have nothing to say to one another at all.

This utterly meaningless exchange would elsewhere be considered dead weight to a story. Here, rather than being fat in need of trimming, the empty conversation is instead thematically resonant.

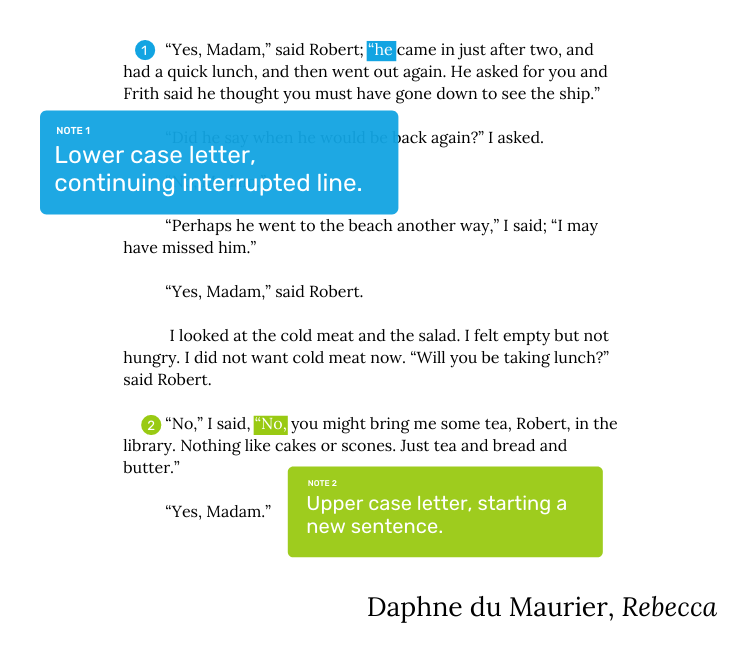

15. Daphne du Maurier, Rebecca

The young narrator of du Maurier’s classic gothic novel here has a strained conversation with Robert, one of the young staff members at her new husband’s home, the unwelcoming Manderley.

“Has Mr. de Winter been in?” I said. “Yes, Madam,” said Robert; “he came in just after two, and had a quick lunch, and then went out again. He asked for you and Frith said he thought you must have gone down to see the ship.” “Did he say when he would be back again?” I asked. “No, Madam.” “Perhaps he went to the beach another way,” I said; “I may have missed him.” “Yes, Madam,” said Robert. I looked at the cold meat and the salad. I felt empty but not hungry. I did not want cold meat now. “Will you be taking lunch?” said Robert. “No,” I said, “No, you might bring me some tea, Robert, in the library. Nothing like cakes or scones. Just tea and bread and butter.” “Yes, Madam.”

We’re including this one in our dialogue examples list to show you the power of everything Du Maurier doesn’t do: rather than cycling through a ton of fancy synonyms for “said”, she opts for spare dialogue and tags.

This interaction's cold, sparse tone complements the lack of warmth the protagonist feels in the moment depicted here. By keeping the dialogue tags simple , the author ratchets up the tension — without any distracting flourishes taking the reader out of the scene. The subtext of the conversation is able to simmer under the surface, and we aren’t beaten over the head with any stage direction extras.

The inclusion of three sentences of internal dialogue in the middle of the dialogue (“I looked at the cold meat and the salad. I felt empty but not hungry. I did not want cold meat now.”) is also a masterful touch. What could have been a single sentence is stretched into three, creating a massive pregnant pause before Robert continues speaking, without having to explicitly signpost one. Manipulating the pace of dialogue in this way and manufacturing meaningful silence is a great way of adding depth to a scene.

Phew! We've been through a lot of dialogue, from first meetings to idle chit-chat to confrontations, and we hope these dialogue examples have been helpful in illustrating some of the most common techniques.

If you’re looking for more pointers on creating believable and effective dialogue, be sure to check out our course on writing dialogue. Or, if you find you learn better through examples, you can look at our list of 100 books to read before you die — it’s packed full of expert storytellers who’ve honed the art of dialogue.

Join a community of over 1 million authors

Reedsy is more than just a blog. Become a member today to discover how we can help you publish a beautiful book.

We have an app for that

Build a writing routine with our free writing app.

1 million authors trust the professionals on Reedsy. Come meet them.

Enter your email or get started with a social account:

Write, talk and rewrite: the effectiveness of a dialogic writing intervention in upper elementary education

- Open access

- Published: 30 August 2023

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Renske Bouwer ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-0434-0224 1 &

- Chiel van der Veen 2 , 3

1880 Accesses

Explore all metrics

In this research, we developed and empirically tested a dialogic writing intervention, an integrated language approach in which grade 5/6 students learn how to write, talk about their writing with peers, and rewrite. The effectiveness of this intervention was experimentally tested in ten classes from eight schools, using a pretest–posttest control group design. Classes were randomly assigned to the intervention group (5 classes; 95 students) or control group (5 classes; 115 students). Both groups followed the same eight lessons in which students wrote four argumentative texts about sustainability. For each text, students wrote a draft version, which they discussed in groups of three students. Based on these peer conversations, students revised their text. The intervention group received additional support to foster dialogic peer conversations, including a conversation chart for students and a practice-based professional development program for teachers. Improvements in writing were measured by an argumentative writing task (same genre, but different topic; near transfer) and an instructional writing task (different genre and topic; far transfer). Text quality was holistically assessed using a benchmark rating procedure. Results show that our dialogic writing intervention with support for dialogic talk significantly improved students’ argumentative writing skills (ES = 1.09), but that the effects were not automatically transferable to another genre. Based on these results we conclude that a dialogic writing intervention is a promising approach to teach students how to talk about their texts and to write texts that are more persuasive to readers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Examining Science Education in ChatGPT: An Exploratory Study of Generative Artificial Intelligence

The Impact of Peer Assessment on Academic Performance: A Meta-analysis of Control Group Studies

Discourses of artificial intelligence in higher education: a critical literature review.

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

In primary schools, only little teaching time is devoted to the productive language skills of writing and speaking (Inspectorate of Education, 2019 , 2021 ). Also, writing, reading and speaking are often covered in separate lessons, making it difficult for students to use language in a variety of meaningful contexts as a means of communication (Sperling, 1996 ). This is particularly problematic for the teaching of writing, as writing is a social act–writers not only write for a general purpose, but they also particularly write to communicate ideas to others (Graham, 2018 ). Demonstrating audience awareness before, during and after writing is therefore considered to be one of the most important aspects of writing proficiency (Rijlaarsdam et al., 2009 ). However, beginning writers do not automatically take the perspective of the reader into account while writing and afterwards, they hardly revise their text accordingly (Bereiter & Scardamalia, 1987 ; Kellogg, 2008 ). As a result, the majority of students in primary school are unable to write texts in which they successfully convey their message to a reader (Inspectorate of Education, 2021 ; National Center for Education Statistics, 2012 ).

Based on previous research (see for example Casado-Ledesma, 2021 ), we argue that fostering a direct dialogue between writers and readers can support students to become more aware of their audience, and hence, support them in writing texts in which they communicate their ideas more effectively. For this purpose, together with educational practitioners, we developed a dialogic writing intervention, which is an integrated approach to written and oral language skills in primary education. This intervention consists of three steps: (1) writing a first draft of an argumentative text, (2) engaging students in small group dialogue about their own written texts, and (3) revising their text based on these conversations. The effectiveness of this writing intervention for fifth- and sixth-grade students (aged 9–13 years) was empirically tested in this study.

Developing audience awareness through dialogic peer talk

From a sociocultural perspective, writing and speaking have a similar function: to convey information to a recipient through language (Sperling, 1996 ). However, where in spoken language there is a direct dialogue between speaker and hearer, the dialogue between writer and reader is indirect. This implies that writers have to anticipate whether their text has the intended communicative effect on the reader and adjust their text accordingly. Experienced writers do this by consistently taking a reader's perspective during the writing process (Kellogg, 2008 ). Putting themselves in the reader's shoes is, however, very difficult for beginning writers; they write as they talk, resulting in "and then, and then"-like stories (Bereiter & Scardamalia, 1987 ). They also hardly revise their text; once the first ideas are on paper, the text barely changes and the only revisions that they make are superficial (Chanquoy, 2001 ). This is particularly problematic when writing argumentative texts, as in this genre revision is an important process to ensure the text becomes as convincing as possible. For example, for argumentative text it is essential to critically re-read the text from the perspective of the reader, in order to determine whether the arguments are convincing enough and what substantial changes in the text are needed to persuade the reader more effectively.

Fostering a dialogue between writer and reader, combined with strategies before and after writing, can support elementary students to write persuasive texts (Casado-Ledesma, 2021 ; Rijlaarsdam et al., 2009 ). In addition, meta-analyses show strong effects of peer interaction on text quality (Graham et al., 2012 ; Koster et al., 2015 ). In these peer conversations, writers themselves experience how their text comes across to readers, which provides them with concrete suggestions for improving the text. These evidence-based instructional practices have been translated into the strategy-based writing method Tekster for upper-elementary students (Bouwer & Koster, 2016 ). Two large-scale intervention studies showed that after four months of strategy-focused instructions, the writing skills of students aged 10–12 improved by one-and-a-half grade (Bouwer et al., 2018 ; Koster et al., 2017 ). Despite these positive results, classroom observations showed that students still found it difficult to have meaningful conversations about each other's texts, taking the reader's perspective and providing the other with substantive feedback.

That peer conversations are hardly ever about arguments in the text was also seen in a small-scale pilot study with elementary students prior to the current research project (Bodewitz, 2020 ). Again, without any instructional support, peer conversations about students’ own written texts turned out to be mostly superficial and mainly focused on the formal aspects of the text, such as spelling, punctuation and layout. Also, the conversations were hardly dialogic in nature; students did not ask each other questions about the ideas in the text and rarely deepened each other's contributions. Not surprisingly, they made almost no meaningful changes when revising their text; their revisions focused mainly on superficial aspects of the text, such as language errors or layout. This raises the question of how we can support students in deepening their conversations about each other's texts.

Research on classroom conversations shows that dialogic conversations in which teachers ask open-ended questions and students are challenged to take the other's perspective, reason, think together and listen critically (Hennessy et al., 2016 ) have a positive effect on students' reasoning skills, motivation and domain-specific knowledge (Dobber, 2018 ; Resnick et al., 2015 ; Van der Veen, 2017 ). Such dialogic conversations also have a positive effect on students’ communication skills (Van der Veen et al., 2017 ). However, there is hardly any scientific research on the use of dialogic conversations in the context of writing instruction (Fisher et al., 2010 ; Herder et al., 2018 ). Also, existing research tends to be correlational and focused on how teachers employ dialogic conversation techniques during whole-class conversations (cf. Myhill & Newman, 2019 ). For example, a recent study shows that teachers' asking open-ended questions and questioning is correlated with higher text quality for argumentative writing (Al-Adeimi & O'Connor, 2021 ). Yet, little is known about what support students need to have dialogic conversations with each other about their own written texts and how this kind of dialogic peer talk improves students’ writing skills.

Research aims

In this research project, we build on the knowledge that already exists about learning to engage in dialogic conversations and explore the extent to which a dialogic writing intervention can contribute to the improvement of writing skills. More specifically, we were interested in the following research questions: what is the effect of a dialogic writing intervention on students’ writing improvements in (a) argumentative writing between pre- and posttest (same genre, near transfer; RQ1), and (b) instructional writing on the posttest (other genre, far transfer; RQ2). In addition, we examined whether (c) possible effects of the intervention on students’ writing performance at posttest can be explained by level of writing proficiency at pretest (RQ3). Finally, we investigated the fidelity and social validity of our dialogic writing intervention (RQ4).