Saving our livelihoods from COVID-19: Toward an economic recovery

We are now living through the most uncertain moment of our times. Many countries have been in lockdown since early March 2020. Even Japan, once a beacon of hope for controlling COVID-19, is now moving toward total isolation. Many political leaders realize that physical distancing might be the norm for at least several months. They wonder how—or if—they can maintain indefinite lockdowns without compromising the livelihoods of their people.

Political leaders aren’t alone in their fears. As the pandemic continues its exponential course, workers in most countries wonder what will become of their jobs when the lockdowns end. Businesses struggling to pay their employees and cover operational costs wonder if they will have clients or customers when they reopen. Banks and investors realize that many companies, especially small and midsize ones, will default and are trying to protect both financial stability and public savings. Meanwhile, governments are working to calculate the magnitude of the shock and sharpening their tools to save economies from collapse. They know that history will judge them by the decisions they make now.

This daunting scenario poses several basic questions. How can we save both lives and livelihoods? Which decisions are best managed by governments? How can they evaluate the risks that experts predict from a prolonged lockdown, such as starvation, domestic violence, and chronic depression—as well as protect jobs, income security, food supplies, and the general welfare of the most vulnerable people among us? How and to what extent should they try to save banks, prevent fiscal ruin, and safeguard future generations?

Governments could address all these questions strategically. In effect, they are caring for two patients who react to the same medicine—physical distancing—in very different ways. The first patient is the public-health system. Physical distancing might cure or alleviate its symptoms but could exacerbate those of the second patient, the economy. This trade-off suggests a physical-distancing strategy for governments: ensuring the health system’s ability to deal with COVID-19 and protecting the economy.

Exhibit 1 shows how different levels of physical isolation affect economic conditions. A recession could occur if faltering demand, restricted supply, and lost income reach critical levels. The differences between scenarios could be tenfold: a country that applies physical distancing in a lax way and ends it too soon could face zero GDP growth, but if the same country imposed a very strict and prolonged quarantine, GDP might plunge by 20 percent. In some Western economies, the latter scenario might increase government control of strategic sectors.

Countries can avoid the worst scenarios if they work quickly along three principal lines of action: first, minimizing the impact of physical distancing on the economy; second, spending deeply to keep it afloat; and third, spending even more to accelerate the crisis recovery and to close historical gaps.

Minimize the economic impact of physical distancing

In a recent article , we showed how different isolation strategies can have different effects on the ability of countries to save both lives and livelihoods. Policies for localized physical distancing at the regional, sectoral, or individual level might have better results than blanket lockdowns of entire countries. The time has therefore come to quantify the impact of lockdowns on people’s livelihoods.

Advanced analytics could help countries estimate—with a high level of confidence—the shock to the economy by aggregating data on power consumption, debit- and credit-card spending, applications for unemployment insurance, default rates, and tax collections. Exhibit 2 estimates the changes in demand for goods and services by using visits to Google services as a proxy. We calculate that the number of these visits in several countries fell by as much as 95 percent during the first two weeks of the lockdowns.

Individual countries that implement localized physical distancing might be able to keep track of how many people are in the streets at any given time and how much economic activity those people generate. But approaches to physical distancing will probably vary a good deal from country to country, depending on how they balance public-health issues with privacy concerns. Countries could plan prolonged lockdowns for the elderly and children and estimate their levels of consumption. They could quantify the number of employees in essential sectors that continue to operate (health, security, food and beverages, agriculture, utilities, and transportation). They could determine which regions or states should remain under complete lockdown and which sectors are operating under strict health protocols in other places. And they could track how many people are working from home in each sector and their contributions to the economy.

Analyzing a granular level of information might help countries quantify the weekly impact of physical distancing on various key indicators by region and by economic sector.

This granular level of information might help countries quantify the weekly impact of physical distancing on GDP, productivity, aggregated demand, income loss, unemployment, poverty, and fiscal-deficit levels by region and by economic sector (Exhibit 3). If countries knew all that information, they would know the cost of the lockdowns on the livelihoods of their people.

Spend deeply to keep the economy afloat

Armed with information on the economic impact of physical-distancing strategies, governments can prepare their next moves (Exhibit 4).

To recover from the pandemic’s health and economic consequences, we must uphold the social contract—the implicit relationship between individuals and institutions. The market economy and the social fabric that holds it together will be deeply compromised, or perhaps undermined, if massive numbers of jobs are lost, vendors can’t fulfill their contracts, tenants can’t make their rent, borrowers default at scale, and taxes go unpaid. Governments could therefore quantify the minimum level of income that households need to cover their basic necessities, the minimum level of liquidity that companies need to cover their costs (including payrolls) and to protect their long-term solvency, the minimum liquidity levels that banks need to support defaults, and the minimum amount of money that governments need to supply all those requirements. Let’s examine each of them.

Formal, informal, or independent workers will all have their own particular financial needs. So will vulnerable populations, such as people at higher risk of infection, which might not be able to return to work for some time. Leaders in the public sector should determine the level of support that each population segment requires and the appropriate distribution channels for fast delivery. Familias en Acción in Colombia and Janani Suraksha Yojana (JSY) in India, for example, are conditional-cash-transfer (CCT) programs that support millions of vulnerable people. Such programs could temporarily expand to cover other segments of the population, such as informal and independent workers. It might also be necessary to consolidate databases and information systems and to digitize all payments.

Since revenues have plummeted, many companies require help to safeguard employment. Their needs vary widely among sectors of the economy; professional-service firms, for example, usually have twice as many working-capital days as restaurants do. What’s more, physical distancing will affect different kinds of companies in different ways. As a first move to help them, several countries have already frozen short-term fiscal, parafiscal, and social-security payments. Some are using innovative instruments to irrigate money—for instance, capitalizing national reinsurance agencies to cover most of the expected losses from the new loans required to bridge payroll payments and working capital.

Banks can play a meaningful role during the crisis in two fundamental ways: lending money to companies in distress and recognizing that some companies simply can’t survive. If default rates on current loan portfolios skyrocket, the expected shock to incomes and to supply and demand could compromise the solvency of some banking systems. Besides thinking about loosening solvency and warranty regulations, governments might consider creative solutions, such as distinguishing among banks according to their credit portfolios to strengthen financial institutions’ balance sheets and injecting government-backed convertible loans against their long-term warrants and restructuring targets. (Governments implemented these mechanisms successfully in other financial emergencies, such as the 1997 Asian market crisis, the 1999 Latin American crisis, and, most recently, the 2008 crisis in Europe and the United States.)

Strengthening the balance sheets of banks might not be enough to deal with the aftermath of COVID-19; governments might have to use monetary expansion through debt and equity emissions backed by central banks. Countries with deeper capital markets could not only securitize loans and new instruments but also use the financial strength and long-term view of pension funds and other institutional investors to ease short-term crisis-related pressures on public finance.

Governments shouldn’t be shy about using such instruments extensively if that’s needed to keep economies running. Since such stimuli would have a cost, additional fiscal requirements could complement them in the medium term. To preserve national solvency, governments might also reexamine historical exemptions from taxation.

Spend more to accelerate the crisis recovery and close historical gaps

After countries estimate the size of the stimulus packages needed to help households, companies, and financial systems, they can start designing additional, customized programs to restore demand and accelerate recovery. People who receive direct subsidies to stay at home could gradually return to work as each sector of the economy introduced new health and behavioral practices. Meanwhile, as many workers as possible should receive new job opportunities. To provide them, governments could introduce innovative labor regulations and help companies operate 24/7 under flexible schemes. They might also turn old-fashioned CCT programs into universal-income alternatives linked to new jobs in ambitious, government-led programs for infrastructure, housing, and industrial reconversion. Each country could find its equivalent of Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal.

Governments may also find it advisable to relax their regulatory regimes to help businesses not only reopen but also grow. Most countries have national, local, and sectoral regulations that were perfectly appropriate before the coming of COVID-19 but will be extremely expensive in the next normal. National programs to eliminate red tape at scale will help a good deal. Speed and flexibility are essential.

Businesses in sectors facing strict physical-distancing policies might need additional long-term capital. Governments could use innovative special-purpose vehicles to inject fresh equity and provide fiscal incentives to attract long-term investors. Businesses receiving that sort of aid should expect to commit themselves to restructuring: rescue packages could promote leaner operations, digital and industrial reconversions, the introduction of new channels, agile organizational structures, and innovative learning techniques. Governments could also ensure that such aid programs encourage competition—poorly designed policies that strengthen oligopolies and threaten the interests of consumers will be costly in the long run.

Although governments should carefully weigh the impact of their aggressive programs against long-term fiscal sustainability, they can play a significant role in restoring demand for goods and services and in fostering investment in new business models. Many initiatives—for instance, accelerating infrastructure projects; fast-tracking private investment to build hospitals, schools, and other social projects; encouraging urban renewal and very large housing projects; sponsoring the development of digital clusters to digitize government services; easing investment conditions to take advantage of global supply chains; capturing near-shore production opportunities; promoting large agribusiness developments; and stimulating exporting—could promote those goals. It is time to spend—but wisely.

The COVID-19 pandemic is a global tragedy. But that shouldn’t—and needn’t—prevent us from finding innovative ways to accelerate progress. It would not be the first disaster to do so. This may be the right time to introduce fiscal, labor, pension, social, environmental, and economic reforms to speed up progress toward sustainable development. Ameliorating poverty, diminishing inequality, and protecting the environment could figure prominently in global and national agendas. Governments, companies, and social organizations could act quickly to promote full financial inclusion, the transition to cashless economies, and the provision of better and more efficient social and public services. Political leaders might condition access to massive economic-stimulus programs on efforts to reduce informality, rethink healthcare systems, digitize entire sectors of the economy to accelerate productivity, and encourage digital innovation—especially high-quality public education with universal internet access.

Governments ought to act quickly. The first step is to understand the economic impact of the crisis in both the short and medium terms. Second, governments could inject the minimum viable liquidity to keep markets alive. Finally, they could expedite ambitious fiscal and monetary policies to accelerate recovery. In most economies and markets—national and international alike—ratios of debt to GDP will likely rise. Confidence that tax frameworks will gradually support next-normal debt levels will be necessary.

Once the pandemic ends, countries around the world will probably find themselves more in debt than ever. If they restructure and innovate, attract investment, and increase their productivity, a new era of human development will begin . But if they spend haphazardly and imprudently, economic and social development might falter for decades to come. The societies, governments, institutions, companies, and people of the Earth now face basic choices. Let’s hope they think about them seriously.

Andres Cadena and Fernando Ferrari-Haines are senior partners in McKinsey’s Bogotá office.

The authors wish to thank Andres Arboleda, Clara Gianola, Juan Martinez, and Sebastian Riomalo for their contributions to this article.

Explore a career with us

Related articles.

How to restart national economies during the coronavirus crisis

Safeguarding our lives and our livelihoods: The imperative of our time

The future is not what it used to be: Thoughts on the shape of the next normal

COVID-19’s Economic Impact around the World

Key takeaways.

- Although the COVID-19 pandemic affected all parts of the world in 2020, low-, middle- and high-income nations were hit in different ways.

- In low-income countries, average excess mortality reached 34%, followed by 14% in middle-income countries and 10% in high-income ones.

- However, middle-income nations experienced the largest hit to their gross domestic product (GDP) growth, followed by high-income nations.

Since the COVID-19 pandemic began in March 2020, the world economy has been affected in many ways. Poorer countries have suffered the most, but, despite their greater resources, wealthier countries have faced their own challenges. This article looks at the impact of COVID-19 in different areas of the world.

First, I put 171 nations into three groups according to per capita income: low, middle and high income. Second, I examined health statistics to show how hard-hit by the virus these nations were. Then, by comparing economic forecasts the International Monetary Fund (IMF) made in October 2019 (pre-pandemic) for 2020 with their actual values, I obtained estimates for the pandemic’s impact on growth and key economic policy variables.

Low- and high-income groups each compose 25% of the world’s countries, and the middle-income group makes up 50%. Average income per capita in 2019 was more than five times larger in the middle-income group than in the low-income group. In the high-income countries, it was almost 20 times larger.

Health Outcomes and Policies

The first table shows that COVID-19 had a significant impact on all three groups. Average excess mortality, which indicates how much larger the number of deaths was relative to previous years, was more than 34% in low-income countries, almost 14% in middle-income countries and about 10% in high-income countries. And even though poorer countries were more affected by deaths, their COVID-19 testing was much more limited given their smaller resources.

Since the beginning of the pandemic, high-income countries did more than one test per person, while low-income countries did only one test per 27 people (or 0.037 per person). Given the significant differences in testing, it is not surprising that reported cases were much higher in wealthier countries. Finally, note that there were significant differences in the progress of vaccination. As of June 2021, nearly 20% of the population in the wealthiest countries was fully vaccinated compared to about 2% in the poorest countries.

Impact on GDP Growth

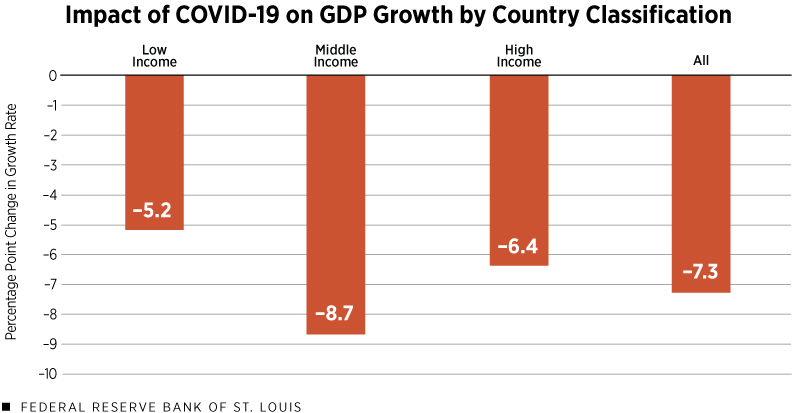

COVID-19-related lockdowns were very common during 2020-21, directly impacting economic activity. The figure below shows the impact on GDP. To isolate the impact of COVID-19 from previous trends, I plotted the difference between the actual GDP growth in 2020 and the IMF forecast made in October 2019.

The immediate consequence of closing many sectors of the economy was a significant decline in GDP growth, which was as large as 8.7 percentage points for the median middle-income countries. Wealthier countries suffered a bit less, with a median of 6.4 percentage points, mainly because they began to recover before the end of 2020. The impact of COVID-19 was smaller in poorer countries because many did not have the resources to implement strict lockdowns. However, even in this group of countries, median GDP growth was 5.2 percentage points lower than expected.

SOURCES: IMF World Economic Outlook Reports (April 2021 and October 2019), Penn World Table (version 10.0) and author’s calculations.

NOTE: The COVID-19 impact is the difference between the actual gross domestic product growth rate in 2020 and the IMF forecast for it made in October 2019.

Economic Policies

Differences in GDP performance are not only related to lockdowns but also to economic policy responses. The second table contains information about six policy variables.

In particular, the first three rows present the fiscal response to the pandemic computed as the difference between the actual value in 2020 and the IMF forecast made before the pandemic in October 2019 relative to GDP. Revenue relative to GDP declined slightly in all regions, but mostly in middle-income countries, reaching more than 1 percentage point of GDP.

Expenditures relative to GDP, however, increased in middle- and high-income countries while remaining stable in low-income countries. These expenditures increased by nearly 7 percentage points of GDP in high-income countries. The more significant fiscal deficit relative to GDP implied a larger increase in net government borrowing, which reached 7 percentage points of GDP in the median high-income countries.

Finally, COVID-19 also had a clear impact on the evolution of monetary aggregates such as cash and deposits. In the table, to isolate the impact of COVID-19 from previous trends, I present the growth rate of M1 and M2 M1 generally includes physical currency, demand deposits, traveler’s checks and other checkable deposits. M2 generally includes M1 plus savings deposits, money market securities, mutual funds and other time deposits. Note that the above definitions can differ slightly by country. net of the yearly growth rates of these variables between 2017 and 2019. The pandemic implied an increase in the growth rate of monetary aggregates across countries in all income groups, but more significantly in wealthier countries.

For instance, the growth rate in M1 was over 10 percentage points larger than in the previous two years in the median high-income countries. Without a change in money demand, such an acceleration in the quantity of money would have implied increasing inflation.

However, the last row of the table shows that inflation remained stable in 2020. In fact, for middle- and high-income countries, inflation in 2020 was lower than the IMF forecast made in October 2019.

Conclusions

COVID-19 impacted health outcomes in all regions of the world. Wealthier countries responded with more testing and quicker vaccination rates. Comparing actual outcomes with pre-pandemic forecasts, I found a significant impact of the pandemic on GDP growth, which is more prominent in middle-income countries.

I conjecture that the impact on GDP growth was less significant in the poorest countries because of less restrictive lockdowns and in the wealthiest countries because of more aggressive economic policies.

- M1 generally includes physical currency, demand deposits, traveler’s checks and other checkable deposits. M2 generally includes M1 plus savings deposits, money market securities, mutual funds and other time deposits. Note that the above definitions can differ slightly by country.

Juan M. Sánchez is an economist and senior economic policy advisor at the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. He has conducted research on several topics in macroeconomics involving financial decisions by firms, households and countries. He has been at the St. Louis Fed since 2010. View more about the author and his research.

Related Topics

Views expressed in Regional Economist are not necessarily those of the St. Louis Fed or Federal Reserve System.

For the latest insights from our economists and other St. Louis Fed experts, visit On the Economy and subscribe .

Media questions

Covering a story? Visit our page for journalists or call (773) 702-8360.

New Certificate Program

Top Stories

- Scientists may have found the spot where our supermassive black hole “vents”

- UChicago scientist seeks to make plastic more recyclable

- UChicago announces 2024 winners of Quantrell and PhD Teaching Awards

How COVID-19 has changed the global economy

Chicago booth scholars discuss what recovery might look like in the wake of a pandemic.

The worldwide economic landscape has changed dramatically over the past four months, as the COVID-19 pandemic has stalled activity in nearly every corner of the world.

With these dramatic changes in mind, the University of Chicago Booth School of Business has convened its inaugural virtual Economic Outlook, focusing on the U.S., Asia and Europe in three events over three weeks.

During the April 30 debut of the online series, Profs. Randall S. Kroszner , Austan D. Goolsbee and Raghuram G. Rajan discussed the critical economic questions facing the world amid the COVID-19 crisis.

Moderated by Kathleen Hays of Bloomberg, the conversation ranged from the possible paths and pitfalls for recovery, to how economic sectors such as manufacturing and hospitality will fare, to concerns about incurring debt.

While much uncertainty remains, the Chicago Booth economists shared their perspectives and concerns around key questions facing business leaders, policymakers, employees, and families worldwide. Portions of the first event are highlighted below.

How have stay-at-home orders affected economies?

With tens of millions of unemployment claims in the United States, as well as more than 100 million jobs lost in India, global economies are suffering.

“We sent everyone home. We didn't allow people to go out and buy anything,” said Kroszner, a former governor of the Federal Reserve System who serves as Booth’s deputy dean for executive programs and Norman R. Bobins Professor of Economics. “So it's not a surprise that you get this astonishing contraction in demand and production.”

Hoping for a ‘reverse check mark’

A former chair of the Council of Economic Advisers and a member of President Barack Obama's cabinet, Goolsbee warned that a traditional recession recovery is a slow process.

“We could go from less than 4% unemployment to 15% in a short period of time. In a normal recovery, the unemployment rate only goes down 1 to 1.5 percentage points a year,” said Goolsbee, the Robert P. Gwinn Professor of Economics.

“Hopefully there is the possibility of a rapid recovery—maybe a reverse check mark where you went down, and then you came back at least part of the way at kind of a rapid pace. We absolutely have to do everything we can to go in that direction because the alternative is much more grim.”

Should the government bail out everyone?

Some sectors, such as manufacturing, can likely come back quickly, said Rajan, who previously served as the governor of the Reserve Bank of India and the chief economist and director of research at the International Monetary Fund. Others, however, will take much longer to fully recover—if they ever do at all. Those differences need to be taken into account when considering government interventions.

“One of the decisions we have to make soon is how the government spends that money,” said Rajan, the Katherine Dusak Miller Distinguished Service Professor of Finance. “It’s going to be expensive to keep the hospitality industry alive for a year or more until people feel comfortable going out again.”

Which sectors might expand or contract?

Kroszner said that an effective recovery strategy should consider which types of jobs will be available in the coming years and how to ensure that employees have the skills to fill them.

“Well-intentioned programs that are trying to freeze things as they were in February are going to make it more difficult for people to find new positions,” Kroszner said. “At some point we're going to have to allow for a transition. We've got to get the support structures right to get people moving into new sectors.”

Restarting regular economic activity

Goolsbee said that the shortest path to recovery is by spending on health care and testing.

“The most important thing you can do for the economy is slow the spread of the virus,” he said. “That’s how you stimulate the economy, because people have to feel safe leaving their homes. We’ve now got six countries that have gotten out of lockdown and are going back to normal. Each of them has done extensive testing to get the rate of the spread of the virus low enough that it peters itself out.”

Paying off debt

Goolsbee said there’s no alternative to adding to the debt, but we should be considering the long-term implications for paying off these debts.

“Nobody in June of 1944 questioned how to pay for D-Day and keep it revenue neutral,” he said. “If you look post-World War II, we went through a period of heavy taxation to pay back the debts that we accumulated. It's what we should have done, and spreading that over time is better than trying to pay for it all at once. The same is true here.”

Rajan added that these burdens could also affect future investment.

“This was the debt overhang problem that many emerging markets had,” Rajan said. “We should be wary when we have lots of debt and potential taxation down the line. A lot of investors are going to be worrying about where it's going to fall, and that could be perhaps very damaging for investment and growth.”

—This story was first published by Chicago Booth . Register here to attend the next event in the virtual Economic Outlook series on May 13, featuring Profs. Veronica Guerrieri, Randall S. Kroszner and Brent Neiman.

Recommended stories

Prof. Raghuram Rajan examines COVID-19’s impact on the global economy

During pandemic, states could save lives by sharing ventilators

Get more with UChicago News delivered to your inbox.

Related Topics

Latest news, big brains podcast: storm warning: why hurricanes are growing beyond measure.

‘Inside the Lab’ series provides a unique look at UChicago research

Geophysical Sciences

Scientists find evidence that meltwater is fracturing ice shelves in Antarctica

Mavis Staples, legendary singer and activist, returns to UChicago to inspire next generation

Where do breakthrough discoveries and ideas come from?

Explore The Day Tomorrow Began

W. Ralph Johnson, pre-eminent UChicago critic of Latin poetry, 1933‒2024

Pulitzer Prize

Trina Reynolds-Tyler, MPP'20, wins Pulitzer Prize in Local Reporting

Around uchicago, uchicago to offer new postbaccalaureate premedical certificate program.

Carnegie Fellow

UChicago political scientist Molly Offer-Westort named Carnegie Fellow

National Academy of Sciences

Five UChicago faculty elected to National Academy of Sciences in 2024

Laing Award

UChicago Press awards top honor to Margareta Ingrid Christian for ‘Objects in A…

Winners of the 2024 UChicago Science as Art competition announced

Six UChicago scholars elected to American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 2024

Biological Sciences Division

“You have to be open minded, planning to reinvent yourself every five to seven years.”

UChicago paleontologist Paul Sereno’s fossil lab moves to Washington Park

The Economic Impact of COVID-19 around the World

This article provides an account of the worldwide economic impact of the COVID-19 shock. In 2020, it severely impacted output growth and employment, particularly in middle-income countries. Governments responded primarily by increasing expenditure, supported by an expansion of the supply of money and debt. These policies did not put upward pressure on prices until 2021. International trade was severely disrupted across all regions in 2020 but subsequently recovered. For 2021, we find that the adverse effects of the COVID-19 shock on output and prices were significant and persistent, especially in emerging and developing countries.

Fernando Martin is an assistant vice president and economist, Juan M. Sánchez is a vice president and economist, and Olivia Wilkinson is a senior research associate at the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis.

INTRODUCTION

For over two years, the world has been battling the health and economic consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic. As of the writing of this article, deaths attributed to COVID-19 have surpassed six-and-a-half million people. Global economic growth was severely impacted: World output by the end of 2021 was more than 4 percentage points below its pre-pandemic trend. International trade was also significantly disrupted at the onset of the pandemic. The pandemic also prompted a strong policy response, resulting in a rise of government deficits and debt as well as widespread increases in the money supply. Finally, after an initial decline, prices have soared, resulting in elevated inflation rates.

This article provides an account of the worldwide economic impact of the COVID-19 shock. This shock was not felt simultaneously around the world, and mitigation policies, both health related and economic, varied substantially across countries. Yet there are some significant similarities in outcomes, especially when considering the pandemic period as a whole. Our analysis focuses on the shock's effects on specific groups of countries, related by their level of development and geographical location.

We find that the COVID-19 shock severely impacted output growth and employment in 2020, particularly in middle-income countries. The government response, mainly consisting of increased expenditure, implied a rise in debt levels. Advanced countries, having easier access to credit markets, experienced the highest increase in indebtedness. All regions also relied on monetary policy to support the fiscal expansion, and hence the money supply increased everywhere. The specific circumstances surrounding the shock implied that the expansionary fiscal and monetary policies did not put upward pressure on prices until 2021. International trade was severely disrupted across all regions in 2020 but subsequently recovered. When extending the analysis to 2021, we find that the adverse effects of the shock on output and prices have been significant and persistent, especially in emerging and developing countries.

Read the full article .

Cite this article

Subscribe to Our Newsletter

Stay current with brief essays, scholarly articles, data news, and other information about the economy from the Research Division of the St. Louis Fed.

SUBSCRIBE TO THE RESEARCH DIVISION NEWSLETTER

Research division.

- Legal and Privacy

One Federal Reserve Bank Plaza St. Louis, MO 63102

Information for Visitors

The Global Economy: on Track for Strong but Uneven Growth as COVID-19 Still Weighs

A year and a half since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, the global economy is poised to stage its most robust post-recession recovery in 80 years in 2021. But the rebound is expected to be uneven across countries, as major economies look set to register strong growth even as many developing economies lag.

Global growth is expected to accelerate to 5.6% this year, largely on the strength in major economies such as the United States and China. And while growth for almost every region of the world has been revised upward for 2021, many continue to grapple with COVID-19 and what is likely to be its long shadow. Despite this year’s pickup, the level of global GDP in 2021 is expected to be 3.2% below pre-pandemic projections, and per capita GDP among many emerging market and developing economies is anticipated to remain below pre-COVID-19 peaks for an extended period. As the pandemic continues to flare, it will shape the path of global economic activity.

The United States and China are each expected to contribute about one quarter of global growth in 2021. The U.S. economy has been bolstered by massive fiscal support, vaccination is expected to become widespread by mid-2021, and growth is expected to reach 6.8% this year, the fastest pace since 1984. China’s economy – which did not contract last year – is expected to grow a solid 8.5% and moderate as the country’s focus shifts to reducing financial stability risks.

Lasting Legacies

Growth among emerging market and developing economies is expected to accelerate to 6% this year, helped by increased external demand and higher commodity prices. However, the recovery of many countries is constrained by resurgences of COVID-19, uneven vaccination, and a partial withdrawal of government economic support measures. Excluding China, growth is anticipated to unfold at a more modest 4.4% pace. In the longer term, the outlook for emerging market and developing economies will likely be dampened by the lasting legacies of the pandemic – erosion of skills from lost work and schooling; a sharp drop in investment; higher debt burdens; and greater financial vulnerabilities. Growth among this group of economies is forecast to moderate to 4.7% in 2022 as governments gradually withdraw policy support.

Among low-income economies, where vaccination has lagged, growth has been revised lower to 2.9%. Setting aside the contraction last year, this would be the slowest pace of expansion in two decades. The group’s output level in 2022 is projected to be 4.9% lower than pre-pandemic projections. Fragile and conflict-affected low-income economies have been the hardest hit by the pandemic, and per capita income gains have been set back by at least a decade.

Regionally, the recovery is expected to be strongest in East Asia and the Pacific, largely due to the strength of China’s recovery. In South Asia, recovery has been hampered by serious renewed outbreaks of the virus in India and Nepal. The Middle East and North Africa and Latin America and the Caribbean are expected to post growth too shallow to offset the contraction of 2020. Sub-Saharan Africa’s recovery, while helped by spillovers from the global recovery, is expected to remain fragile given the slow pace of vaccination and delays to major investments in infrastructure and the extractives sector.

Uncertain Outlook

The June forecast assumes that advanced economies will achieve widespread vaccination of their populations and effectively contain the pandemic by the end of the year. Major emerging market and developing economies are anticipated to substantially reduce new cases. However, the outlook is subject to considerable uncertainty. A more persistent pandemic, a wave of corporate bankruptcies, financial stress, or even social unrest could derail the recovery. At the same time, more rapid success in stamping out COVID-19 and greater spillovers from advanced economy growth could generate more vigorous global growth.

Even so, the pandemic is expected to have caused serious setbacks to development gains. Although per capita income growth is projected to be 4.9% among emerging market and developing economies this year, it is forecast to be essentially flat in low-income countries. Per capita income lost in 2020 will not be fully recouped by 2022 in about two-thirds of emerging market and developing economies, including three-quarters of fragile and conflict-affected low-income countries. By the end of this year, about 100 million people are expected to have fallen back into extreme poverty. These adverse impacts have been felt hardest by the most vulnerable groups – women, children, and unskilled and informal workers.

Global inflation, which has increased along with the economic recovery, is anticipated to continue to rise over the rest of the year; however, it is expected to remain within the target range for most countries. In those emerging market and developing economies in which inflation rises above target, this trend may not warrant a monetary policy response provided it is temporary and inflation expectations remain well-anchored.

Climbing Food Costs

Rising food prices and accelerating aggregate inflation may compound rising food insecurity in low-income countries. Policymakers should ensure that rising inflation rates do not lead to a de-anchoring of inflation expectations and resist using subsidies or price controls to reduce the burden of rising food prices, as these risk adding to high debt and creating further upward pressure on global agricultural prices.

A recovery in global trade after the recession last year offers an opportunity for emerging market and developing economies to bolster economic growth. Trade costs are on average one-half higher among emerging market and developing economies than advanced economies and lowering them could boost trade and stimulate investment and growth.

With relief from the pandemic tantalizingly close in many places but far from reach in others, policy actions will be critical. Securing equitable vaccine distribution will be essential to ending the pandemic. Far-reaching debt relief will be important to many low-income countries. Policymakers will need to nurture the economic recovery with fiscal and monetary measures while keeping a close eye on safeguarding financial stability. Policies should take the long view, reinvigorating human capital, expanding access to digital connectivity, and investing in green infrastructure to bolster growth along a green, resilient, and inclusive path.

It will take global coordination to end the pandemic through widespread vaccination and careful macroeconomic stewardship to avoid crises until we get there.

- Foreword by World Bank Group President David Malpass

- Report website

- Report download

- Press Release

- Blog: The Global Economic Outlook in five charts

- Download report data

- Download all charts (zip)

This site uses cookies to optimize functionality and give you the best possible experience. If you continue to navigate this website beyond this page, cookies will be placed on your browser. To learn more about cookies, click here .

Building back better: A sustainable, resilient recovery after COVID-19

For the economic recovery from the COVID-19 crisis to be durable and resilient, a return to ‘business as usual’ and environmentally destructive investment patterns and activities must be avoided. Unchecked, global environmental emergencies such as climate change and biodiversity loss could cause social and economic damages far larger than those caused by COVID-19. To avoid this, economic recovery packages should be designed to “build back better”. This means doing more than getting economies and livelihoods quickly back on their feet. Recovery policies also need to trigger investment and behavioural changes that will reduce the likelihood of future shocks and increase society’s resilience to them when they do occur. Central to this approach is a focus on well-being and inclusiveness. Other key dimensions for assessing whether recovery packages can “build back better” include alignment with long-term emission reduction goals, factoring in resilience to climate impacts, slowing biodiversity loss and increasing circularity of supply chains. In practice, well-designed recovery policies can cover several of these dimensions at once, such as catalysing the shift towards accessibility-based mobility systems, and investing in low-carbon and decentralised electricity systems.

1. Governments’ first priorities in tackling the COVID-19 pandemic have been to overcome the health emergency and to implement rapid economic rescue measures, the latter mostly aimed at providing essential liquidity and protecting livelihoods in the face of abrupt losses of income. As the health crisis gradually abates in some countries, attention is now turning to preparing stimulus measures for triggering economic recovery. This policy brief examines how these stimulus packages can create a recovery that “builds back better”, i.e. not only getting economies and livelihoods back on their feet quickly, but also safeguarding prosperity for the longer term. This means triggering investments and societal changes that will both reduce the likelihood of future shocks and improve our resilience to those shocks when they do occur, whether from disease or environmental degradation. At the heart of this approach is the transition to more inclusive, more resilient societies with net-zero GHG emissions and much reduced impacts on nature. Other OECD policy briefs examine the role of environmental health in strengthening resilience to pandemics (OECD, 2020[1]) and COVID-19 and the low-carbon transition (OECD, forthcoming).

A more resilient economy depends on a shift to sustainable practices

2. In addition to the immediate human suffering caused by the disease itself and the loss of livelihoods for millions, the COVID-19 pandemic has also highlighted several key vulnerabilities of our societies and economic system . Global interconnectedness has helped to create huge economic and social benefits for decades, albeit unequally, but also facilitated the rapid spread of the pandemic. More broadly, the speed and depth of the economic crisis have shown that a core principle of the global economy – prioritising short-term economic growth and efficiency over long-term resilience – can have huge societal costs. The precariousness of long and complex global value chains has been revealed, with many countries struggling to acquire medical and other strategic supplies. Social inequalities have been exposed and rapidly exacerbated by the massive but uneven loss of employment, with the equivalent of more than 300 million jobs potentially at risk (ILO, 2020[2]) . Although this is not the first economic crisis to expose these frailties, the depth and breadth of the current circumstances have brought the issue of resilience and preparedness high in the public consciousness.

3. The exposed vulnerabilities are particularly sobering when seen in the light of an even bigger future threat to the global economy: environmental degradation driven by our current economic system. The world’s environmental emergencies are as pressing as ever, even if they may seem distant during such a very human crisis. The impacts of climate change, air pollution, biodiversity loss and poor ocean health already cause immense suffering globally and harbour further systemic vulnerabilities for the global economy that could ultimately eclipse the current crisis. Physical and economic impacts from climate change are already being felt, and some regions have experienced extreme weather events at the same time as tackling COVID-19, such as super-cyclone Amphan in Bangladesh and Typhoon Vongfong in the Philippines (UN, 2020[3]) . Without structural changes to our economies, continued accumulation of greenhouse gases (GHGs) in the atmosphere will lead to potentially catastrophic further impacts. While the economic shut-down has led to some widely-reported environmental improvements, such as reduced emissions of GHGs and air pollutants and less water pollution, these in themselves will have almost no long-term impact (Le Quéré et al., 2020[4]) . If economic activity resumes as before, they are likely to be temporary and quickly erased. Indeed, GHG emissions rebounded and resumed growth in the aftermath of the recent economic crises (OECD, 2020 forthcoming).

4. These interlinked environmental crises may also heighten the likelihood and likely impact of future infectious diseases. The economic pressures driving biodiversity loss and the destruction of ocean health can have cascading impacts on societies, and may increase the risk of future zoonotic viruses (those which jump from animals to humans) due to the expansion of human activities leading to deforestation, combined with the increased demand for and trafficking of wildlife (Jones et al., 2013[5]) . Declines in local environmental quality, including air and water pollution, can influence the vulnerability of societies both to disease and to the effects of a less stable climate, with impacts likely to affect poorer communities more (OECD, 2020[1]) .

5. Returning to “business as usual” will not deliver a sustained long-term economic recovery that also improves well-being and reduces inequality. With massive stimulus packages starting to be unveiled around the world, governments, businesses and societies as a whole have both a responsibility and self-interest to not only look for near-term measures to shore-up livelihoods and employment, but also to take a step back and reflect on the political and economic driving forces leading to the current crisis.

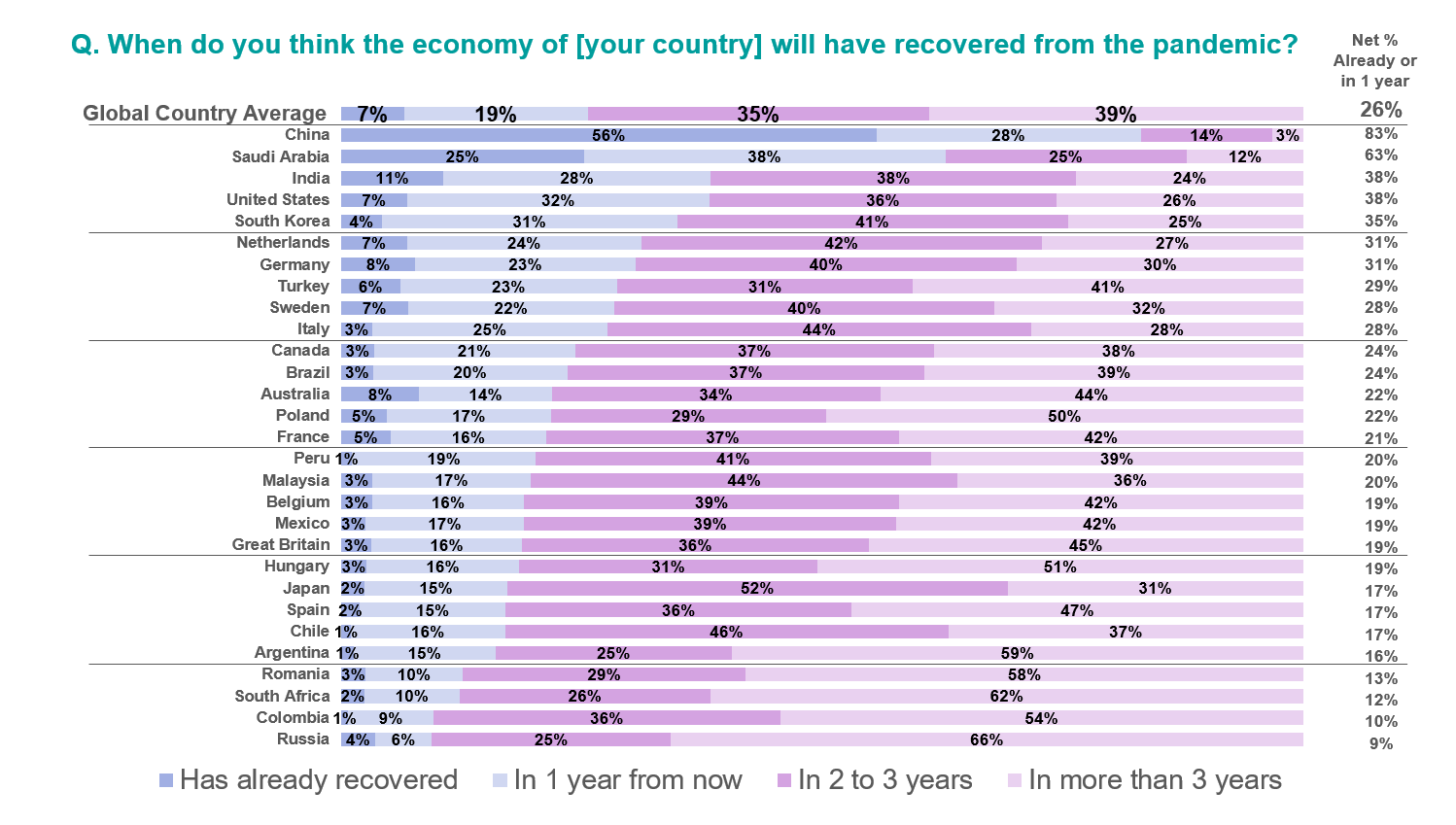

6. Despite encouraging signs from governments, businesses and citizens, recovery plans have so far mostly fallen short. Many governments have recognised the need and opportunity of a sustainable recovery. For example, in April 2020, the G20 Finance Ministers agreed to “commit to support an environmentally sustainable and inclusive recovery” (G20, 2020[6]) . Encouragingly, an international poll covering developed and developing countries also suggests that a majority of citizens see a focus on environmental issues as a continued priority as we emerge from the COVID-19 crisis (IPSOS MORI, 2020[7]) . The fragilities exposed by the pandemic may act to underline the reasons that environmental issues were becoming top political priorities around the world before COVID-19 struck. In 2019, millions of people, spearheaded by youth, protested in the streets for climate action, leading to several governments officially declaring a “climate emergency”. Biodiversity loss and the ongoing mass species extinction were also gaining headlines around the world, and the visible crisis engulfing the world’s oceans had become a front-line political issue in several countries. As recently as January 2020, climate change and biodiversity loss topped the World Economic Forum’s list of global risks (World Economic Forum, 2020[8]) . The social and economic case for a sustainable, resilient recovery is very clear. Despite this, economic recovery measures proposed so far have mostly scored poorly on environmental metrics, with unsustainable support outstripping sustainable measures in many countries (Vivid Economics, 2020[9]) . While there is significant support for “green” technologies and industries, in particular in European countries, in many cases this is outweighed by ongoing support for “brown” activities that may lock-in emissions intensive pathways.

“Building Back Better”: key dimensions for a resilient economic recovery

7. The term “Building Back Better” has been increasingly and widely used in the context of the economic recovery from COVID-19 (WRI, 2020[10]) (We Mean Business Coalition, 2020[11]) . The notion originated in the context of recovery and reconstruction from physical disasters 1 , with an emphasis on making preventative investments that improve resilience to, and so reduce the costs of, future disasters. The challenge of re-igniting the global economy in the aftermath of the economic crisis triggered by COVID-19 is of course different. There has been no physical disaster, and the focus is global. Yet the economic crisis is so severe, the risks from returning to previous patterns so high, and the opportunity to embrace a more sustainable recovery so clear, that the term is relevant in this context. Even at the global level, there is still an emphasis on prevention, as the investments and behavioural changes made will pay dividends in the future through reduced exposure and increased resilience to costly future disruptions – whether due to climate change, disease, or a confluence of these or other factors.

8. To “build back better”, recovery measures can be assessed across a number of key dimensions (Figure 1). Common to all these dimensions is the need for urgent decisions taken today to incorporate a longer-term perspective. For example, assessing measures against these dimensions can expose where competing potential targets for stimulus spending may offer similar near-term benefits in terms of job creation, but very different long-term outcomes for sustainability and resilience (for example, whether or not the stimulus leads to investment in long-lived high-emitting infrastructure that may lock-in GHG emissions far into the future).

9. A central dimension of building back better is the need for a people-centred recovery that focuses on well-being, improves inclusiveness and reduces inequality. To improve public support, recovery policies need to be measured on more than just economic growth and total job creation. Emphasising other elements that improve well-being, such as income, job quality, housing and health is important to achieve this (OECD, 2020[12]) . More specifically, where stimulus packages target environmental objectives, a focus on people’s well-being is also crucial to cement the social and political acceptance of environmental measures (OECD, 2019[13]) . Even before the crisis, the impact of environmental policies on inequalities among and within countries, and between genders, was a mounting key concern in several regions, and this is even more critical in the current context. Means for ensuring that environmental measures are socially inclusive include making taxes and subsidies progressive (supporting the most vulnerable) and preparing the workforce for the green transition, for example by adapting and adopting “Just Transition” principles refocused for an era of economic crisis and recovery (OECD, 2017[14]) .

10. The relative importance of the other dimensions will likely vary across different country contexts, according to their development priorities, infrastructure needs and social circumstances, in particular for developing countries. These dimensions include:

Aligning recovery measures with long-term objectives for reducing GHG emissions. Avoiding the worst impacts of climate change is key to future resilience and stability. A careful assessment of the influence of stimulus packages on future GHG emissions trajectories is crucial, including in the context of moving towards net-zero emissions. This relates both to near-term emissions of economic activities receiving liquidity support, as well as long-term structural implications of potential lock-in through infrastructure investment decisions facilitated by recovery packages. The long-lived nature of infrastructure investments likely to be made through stimulus packages means that decisions made now will have implications for decades to come, and could determine whether the world can achieve its goals of averting the worst impacts of climate change.

Strengthening resilience to the impacts of climate change. Resilience to climate change is one specific aspect of improving the overall resilience of economies and societies. In particular, infrastructure networks will face increasing pressures from the impacts of climate change, but also play an important role in building society’s resilience to those impacts. Infrastructure investment is likely to be a key component of recovery measures in many countries – in part because of job creation potential – and it is important to ensure that infrastructure investments are climate resilient and do not increase exposure and vulnerability. This will reduce direct economic damages from climate related disasters and minimise the indirect costs created by the cascading impacts caused by the disruption of both critical services and economic activities. New infrastructure investments, including in low-carbon developments, need to build in resilience against future climate impacts, by assessing climate risks across the lifetime of the project. Retrofitting existing infrastructure is more costly, both organisationally and in terms of physical investment (OECD, 2018[15]) .

Integrating more ambitious policies to halt and reverse biodiversity loss and restore ecosystem services, including through nature-based solutions. Biodiversity and ecosystem services are fundamental to economic activities and human health; deforestation and other land use change have been linked to the spread of diseases. Investment in natural infrastructure such as reforestation and wetland and mangrove restoration are not only a cost effective and sustainable way to improving resilience to climate impacts, but offer employment opportunities similar to man-made infrastructure investments. Investments targeted through stimulus packages need to better assess and value biodiversity and ecosystem services, and integrate these values into decision-making. In addition, government support that is potentially harmful to biodiversity must be identified and reformed. Additionally, valuing natural capital is integral to improving a range of environmental health dimensions that are important for societal resilience to pandemics and other shocks (such as cleaner air and water (these issues are covered in detail in another policy brief (OECD, 2020[1]) )

Fostering innovation that builds on enduring behaviour changes . Continued technological and process innovation will be critical to achieving climate and other sustainability goals. Governments play a key role in fostering an innovation ecosystem, well beyond funding basic research and development (OECD/The World Bank/UN Environment, 2018[16]) . However, the COVID-19 pandemic will affect cultural norms and behaviour in ways that are not yet known. To be effective at creating jobs and improving resilience, stimulus packages need to take into account potential behaviour changes that could affect the saliency of different policy measures, including for innovation. For example, tackling reluctance to take public transport by encouraging measures to reduce crowding, improve hygiene and to encourage “active” transport modes; introducing measures that better support remote working (including well-being aspects) in order to reduce demand for transport such as encouraging remote working and events.

Improving resilience of supply chains, including through increased adherence to circular economy principles: the COVID-19 pandemic and containment measures have raised new questions about the systemic resilience of complex global production methods and value chains, triggering renewed interest in more diversified and more localised production and shorter supply chains in certain sectors. The environmental implications of such a shift are far from clear, but there is a role for policy, including through stimulus packages to ensure that local supply chains do genuinely improve resilience and reduce environmental impacts, including by improving resource efficiency and increasing circularity of supply chains.

11. Fortunately, designing stimulus measures in this way does not mean starting with a blank slate. International agreements already exist across many of these dimensions, such as the Paris Agreement on climate change, the Aichi Biodiversity Targets, and the Sendai Framework for disaster risk reduction. The UN Sustainable Development Goals also provide an overarching compass for ensuring that social development and well-being is fully integrated with environmental objectives. In terms of policy measures, many of the needed actions to build back better and improve resilience through stimulus packages can build on existing knowledge of policy design implementation. For example, although GHG emissions were growing until 2019, the experience from more than two decades of designing and implementing climate responses and assessing their effectiveness remains relevant. Similar policy knowledge exists for halting and reversing biodiversity loss, and improving circularity of material use, among others. Additionally, there are some key lessons from environmental measures integrated into stimulus measures following the global financial crisis in 2008-09 (Agrawala, Dussaux and Monti, 2020[17]) . 2

“Building Back Better” in practice

12. This section provides some key examples of opportunities for “building back better” across sectors, highlighting where public stimulus spending could be oriented to align across several of the above dimensions simultaneously. These examples are clearly not exhaustive, but are highlighted here because of their relevance for where stimulus investments can catalyse important systemic change in economic sectors while also meeting the urgent need for creating employment, or otherwise trigger changes necessary to support longer-term resilience outcomes. While these examples cover a wide range of specific policy areas, some overarching policy guidance is provided in Box 1.

Enhancing biodiversity while ensuring a resilient supply of food

13. Biodiversity and natural infrastructure such as forest, wetland and mangrove ecosystems, are essential inputs for many economic activities, and are central to hundreds of millions of livelihoods. Natural ecosystems are also essential pillars of resilience. Yet most of this natural capital is undervalued in the economy, or valued only as a harvestable commodity and not for the vital ecosystem services provided. The unpriced natural capital consumed by primary production (agriculture, forestry, fisheries and mining) and some primary processing sectors (including cement, steel, pulp and paper) was valued at USD 7.3 trillion in 2013 (Natural Capital Coalition, 2016[18]) . However, despite the introduction of some policies to value biodiversity, in particular through payments for ecosystem services, most existing approaches to measure and value natural capital loss remain limited (OECD, 2019[19]) . Through recovery packages, governments may have leverage to increase private finance for nature-based solutions and to enlarge the commitment of businesses and investors to measure biodiversity impacts, dependencies, risks and opportunities, e.g. through conditions for financial support in recovery packages to agriculture and other sectors with close links to biodiversity (OECD, 2019[19]) .

While the multiple dimensions of “building back better” span many specific policy areas, some key recommendations for governments to consider are:

Screen all elements of stimulus packages for their longer terms implications across the key dimensions outlined above, prioritising actions that:

Combine benefits for jobs and reducing inequality with implications for longer-term resilience, including by avoiding locking-in emissions intensive infrastructure and systems.

Can be implemented quickly, including “shovel-ready” targets for public investment and existing policy frameworks that can be rapidly scaled up

Favour cross-sectoral, cross-government approaches that take a long-term, systemic view rather than single technological outcomes

Build pipelines of “shovel-ready” sustainable infrastructure projects: take co-ordinated cross-ministry action to build pipelines of sustainable projects that can be implemented quickly, while avoiding favouring established emissions-intensive activities just because they are fast

Maintain (and increase) ambition of long-term environmental objectives (including net-zero GHG emissions) and ensure that policies and investments triggered through stimulus packages are aligned with those outcomes , for example:

Avoid relaxing existing environmental regulations to provide near-term relief, as the costs of longer-term vulnerability will often outweigh short-term economic relief

Make subsidies and other government support for specific industries conditional on both environmental improvements (including GHG emissions) and better overall resilience (including for the workforce)

Make energy pricing coherent as part of fiscal reorganisation post-crisis, including phasing out fossil-fuel subsidies and building carbon pricing that includes social protections (e.g. using carbon pricing revenue to mitigate distributional implications for households, as well as to finance support for structural adjustment of workers and communities).

Actively support development of green finance flows to improve resilience, encouraging longer-term horizon for financial decisions :

Measure the consistency of investments and financing with climate change mitigation and resilience, building on existing private and public sector initiatives (Jachnik, Mirabile and Dobrinevski, 2019[20])

Promote robust and transparent definitions and standards for green finance in order to guide financial allocations and investment (including taxonomy approaches);

Increase potential for public finance to catalyse private investment by further empowering public finance institutions: e.g. by increasing lending authority and ability to co-invest.

Increase and improve capacities to assess, manage and publicly disclose climate change-related financial risks, building on existing frameworks and approaches (e.g. TCFD, NGFS).

Design public procurement processes that value both resilience and low-carbon as well as promoting innovation : for example ranking bids based costs over the asset lifetime under different climate impact scenarios, and accounting for life-cycle GHG emissions.

Provide specific support for reskilling and training for industries affected by the immediate crisis and longer-term decarbonisation, along with supportive policies such as reforming housing policies to encourage mobility.

14. The food sector is fundamentally important for the conservation and sustainable use of natural capital, and ultimately dependent on it. Secure food supply is essential for well-being and economic stability – indeed even to sustain life – meaning that the availability and affordability of food are likely to be key government priorities coming out of the crisis (OECD, 2020[21]) .

15. The agriculture sector faces growing threats including from climate change and infectious diseases of plants and livestock. It is also a major driver of environmental degradation. Land-use change, including for agriculture, is responsible for a large part of deforestation. Furthermore, excessive fertilizer use has important implications for freshwater and ocean ecosystems due to nutrient run-off. Increased ecosystem pressures due to agriculture could also have implications for potential creation of new human diseases. Agricultural expansion into zones close to wilderness areas increases pressures on biodiversity, and agricultural intensification, for example with denser livestock populations, can increase the chance of zoonotic transfer of viruses across species (Jones et al., 2013[5]) .

16. Agriculture already receives substantial government support globally. In 53 countries analysed by the OECD, farmers received around USD 528 million in support in 2019 (OECD, 2019[22]) . In addition to securing jobs and preventing near-term supply disruption, recovery measures should aim to reshape policies in the sector to promote environmental sustainability and resilience, and innovation for improved productivity. In the context of the COVID crisis, there is potential to focus on reform of the most harmful and distortive measures, including but not limited to the reinforcement of coupled supports (i.e. those proportional to production or livestock), as well as the relaxation of environmental regulation. Such measures could otherwise contribute to locking-in unsustainable practices and delay the transition of food systems towards sustainable practices. Investments and training aimed at triggering farmers’ transition to more sustainable agricultural practices would benefit the environment, climate, as well as farmers’ livelihoods.

17. More generally, patterns of consumer food choices can be important levers for ambitious climate mitigation as well as for improving health and well-being through balanced diets. Where access to sufficient protein is not an issue, policies to promote lower-emission food choices may also help, such as encouraging more plant-based food choices or shifting to sourcing from lower-emission livestock systems. Measures that could contribute to such objectives include public communication campaigns or education. It is also crucial that, governments address the issue of food security for vulnerable populations. Food stamps and increased subsidies may also be an option to help vulnerable populations, as long as physical access to healthy food and diets is ensured.

Investing for low-carbon, resilient electricity systems

18. Economic stimulus packages can help accelerate the shift towards a zero-carbon, climate-resilient electricity system while creating jobs. While large-scale renewables remain important in this regard, distributed renewables, demand-side energy efficiency and improving the flexibility of the power system are also important opportunities.

19. Energy-related stimulus measures need to consider the changed context of the global energy system, with a historic reduction in energy demand expected in 2020, contributing to extremely low and volatile fossil fuel prices (IEA, 2020[23]) . Enduring low oil and gas prices reduce incentives for energy efficiency and renewables, as well as leading to reduced investment in fossil fuel industries. Energy investment is expected to decline sharply in 2020, even for renewables (IEA, 2020[24]) . In this context, using stimulus spending to invest in and mobilise finance for ‘shovel-ready’ utility-scale renewables (e.g. wind and solar photovoltaic) remain key levers for a sustainable economic recovery. But this is only part of the story. Stimulus packages can additionally seek to drive investment in other measures that accelerate decarbonisation while also improving resilience of the electricity system, both to climate impacts and demand shocks such as that triggered by the current crisis. Examples include energy efficiency, distributed energy resources and improving the flexibility of the power system. In developing countries, measures that increase electricity access, including through off-grid or mini-grid renewable systems, can have many benefits for employment, well-being, health and societal resilience ( (IEA, 2017[25]) .

20. Energy efficiency is a clear candidate for a green recovery package but it is essential to achieve climate goals and is often generally labour-intensive. More than 3.3 million people are employed in energy efficiency in the US and EU alone, most of them in small and medium sized enterprises (IEA, 2020[26]) . Prioritising energy conservation and distributed energy resources also improves the resilience of the power system while delivering on a number of well-being benefits (enhanced affordability, lower environmental footprint, lower investment needs in network infrastructure). Beyond power, an important target for energy efficiency is the building sector (covered below). Energy efficiency across the economy can also mean a switch to electricity for energy uses previously directly using fossil fuels, such as electrification in industry, roll-out of electric vehicles and electric heat pumps as part of building energy efficiency measures (IEA, 2018[27]) . While this electrification trend can have substantial benefits for reduced air pollution at the point of use, the implications for GHG emissions depend on the decarbonisation of the underlying electricity system, as well as its ability to handle the increased demand pattern.

21. Challenges to scaling up energy conservation and distributed energy resources during the recovery include the relatively small scale of these projects and potential liquidity constraints for both households and firms. Governments could leverage on existing programmes, create ‘project pipelines’ of shovel-ready projects, and identify partners (e.g. utilities, municipalities, housing associations) and channels (e.g. energy efficiency obligations, on-bill financing) that help scale up the programmes in the short-term without creating a boom and bust cycle (IEA, 2020[26]) . These measures can be accompanied by investments in training to reduce skill shortages in the power and energy sector, including for energy system engineers and building retrofit specialists.

22. Another important target for stimulus packages is public investment in flexibility of power systems. This can include electricity storage (notably lithium ion batteries, also essential for electric transport), smart grids (e.g. rollout of smart meters) that are crucial for demand response, facilitating the integration of variable renewable energy sources and improving interconnection of grids. The lock-down measures imposed during the COVID-19 crisis have shone a spotlight on the importance of grid system flexibility, because falling demand has raised the share of renewables due to their priority dispatch and low-running costs. Finally, innovation in the energy sector is essential for technologies that will be essential for reaching net-zero emissions over the longer-term, including carbon capture and storage.

Energy efficient housing as part of compact, resilient and sustainable cities:

23. The confinement of hundreds of millions of people to their homes due to COVID-19 has highlighted major failures in the housing sector and illuminating social inequalities related to the quality and comfort of dwellings and building services such as sanitation. Situations where poor quality housing increases inequality by posing major threats for security and health have become ever more visible, including through indoor air-pollution, as well through increased living costs due to poor energy efficiency.

24. Cities, and the building sector more broadly, are key targets for energy efficiency improvements. Buildings account for nearly 30% of global CO 2 emissions, both through direct burning of fossil fuels for heating and indirectly through their electricity consumption (IEA, 2019[28]) . To achieve the goals of the Paris Agreement, there is a strong need both for retrofit of existing building stock and for new builds to meet stringent energy-efficiency standards. Despite the clear benefits of investing in building efficiency, the barriers are well-known, including the need for upfront capital, behavioural inertia and split incentives between landlords and tenants. In emerging economies, the investment gap for green buildings is estimated at USD 1 trillion annually according to the IFC. While country contexts vary for both types of investments, policy gaps (e.g. the need for building standards and incentives for energy efficiency), and the need for robust and scalable business and financing models, are typically key factors standing in the way of accelerated investment. Stimulus packages could therefore be critical to invest in the massive retrofits needed to reduce GHG emissions from the building stock at the same time as improving living conditions and creating jobs. Measures include direct grants, tax breaks for efficiency investments and potentially scrappage schemes for inefficient household appliances. Good experience with such measures was gained from stimulus measures following the 2008 financial crisis (Agrawala, Dussaux and Monti, 2020[17]) . Policy incentives for residential energy efficiency also present clear opportunities for attracting private sector investment ( (I4CE, 2020[29]) .

25. More broadly, economic recovery measures need to consider better coordination between housing policies and wider urban planning. In many countries urban planning has led to sprawling cities, with structurally higher GHG emissions and air pollution than dense cities, for several reasons including increased reliance on private cars. The COVID-19 pandemic could exacerbate this trend through an increase in demand for less dense neighbourhoods. For example, city dwellers may seek single-family homes in less dense neighbourhoods, due to a perception of higher infection risk in more dense housing. This could run counter to efforts to curb GHG emissions and could create a tension between balancing future resilience with mitigation. Transforming cities into liveable places where people want to live and stay can help offset this trend and contribute to both decarbonisation, resilience and lower inequality. Measures could include integrating programmes to retrofit buildings as part of wider sustainable development plans for neighbourhoods. In addition, creating the conditions for the uptake of eco-districts, both as part of urban revitalization and new developments, can help to make cities attractive places to live, as well as improving resilience to climate change impacts such as more intense heatwaves. Finally, promoting mixed land-uses and enhancing walking and cycling accessibility are key, providing redundancy in transport options that is a pillar of improved resilience, discussed further below.

Catalysing the shift towards accessibility-based mobility systems

26. For passenger transport, stimulus packages should aim to combine support for a transition to less polluting cars with investments that initiate a shift towards accessibility-based mobility. The automotive sector is a major global employer, accounting for around 14 million jobs globally, and has been severely affected by the COVID-19 crisis (ILO, 2020[30]) . As governments consider longer-term support for ailing car manufacturers, they can ensure that such support is contingent on environmental improvements including accelerating the shift to electric cars as well as more efficient, cleaner ICE vehicles. However, recovery measures should also embrace a shift towards mobility systems designed around accessibility (the ease of reaching jobs, services, leisure activities, etc.), rather than only emphasising an accelerated uptake of private electric vehicles. The latter would lock-in private vehicle ownership and low-occupancy vehicle use. This would limit the overall emissions reduction potential of the transport sector, and also implies a less resilient system due to overreliance on one transport mode. A mobility system based heavily on private vehicles is also badly equipped to achieve other social and economic goals (e.g. reduced inequality, better health and less congestion).

27. Investing in public transport remains essential both for mobility and for jobs: almost as many people work in public transport as in the car industry (13 million) (UITP, 2017[31]) . However, governments need to recognise new challenges for public transport, such as people being reluctant to take mass transit for sanitary reasons (ITF, 2020[32]) . As well as urgent hygiene and social distancing measures, over the longer term financial support and infrastructure spending could be targeted to enhance capacity, reduce crowding and rebuild the appeal of public transport, especially as capacity is likely to be strained while social distancing measures remain in place (Liebreich, 2020[33]) . Already some cities have benefited from traffic drops during the contingency phase to speed up public transport projects, such as the Bus Rapid Transit extension in Reno, and the metro construction in Los Angeles. 3

28. Governments could also envisage cooperation with both public transport providers and businesses in two ways. Firstly, to support the shift towards public transport pricing schemes that make more efficient use of transport capacity (e.g. peak/off-peak pricing) and secondly, to encourage more flexible working schedules and remote working where possible. In parallel, investment in electric vehicle charging infrastructure is a key opportunity for recovery packages, both for private vehicles and electrified public transport such as buses. Charging plans need to take into account the opportunity cost for other modes as well as public space used.