An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Indian J Psychiatry

- v.53(2); Apr-Jun 2011

How to write a good abstract for a scientific paper or conference presentation

Chittaranjan andrade.

Department of Psychopharmacology, National Institute of Mental Health and Neurosciences, Bangalore, Karnataka, India

Abstracts of scientific papers are sometimes poorly written, often lack important information, and occasionally convey a biased picture. This paper provides detailed suggestions, with examples, for writing the background, methods, results, and conclusions sections of a good abstract. The primary target of this paper is the young researcher; however, authors with all levels of experience may find useful ideas in the paper.

INTRODUCTION

This paper is the third in a series on manuscript writing skills, published in the Indian Journal of Psychiatry . Earlier articles offered suggestions on how to write a good case report,[ 1 ] and how to read, write, or review a paper on randomized controlled trials.[ 2 , 3 ] The present paper examines how authors may write a good abstract when preparing their manuscript for a scientific journal or conference presentation. Although the primary target of this paper is the young researcher, it is likely that authors with all levels of experience will find at least a few ideas that may be useful in their future efforts.

The abstract of a paper is the only part of the paper that is published in conference proceedings. The abstract is the only part of the paper that a potential referee sees when he is invited by an editor to review a manuscript. The abstract is the only part of the paper that readers see when they search through electronic databases such as PubMed. Finally, most readers will acknowledge, with a chuckle, that when they leaf through the hard copy of a journal, they look at only the titles of the contained papers. If a title interests them, they glance through the abstract of that paper. Only a dedicated reader will peruse the contents of the paper, and then, most often only the introduction and discussion sections. Only a reader with a very specific interest in the subject of the paper, and a need to understand it thoroughly, will read the entire paper.

Thus, for the vast majority of readers, the paper does not exist beyond its abstract. For the referees, and the few readers who wish to read beyond the abstract, the abstract sets the tone for the rest of the paper. It is therefore the duty of the author to ensure that the abstract is properly representative of the entire paper. For this, the abstract must have some general qualities. These are listed in Table 1 .

General qualities of a good abstract

SECTIONS OF AN ABSTRACT

Although some journals still publish abstracts that are written as free-flowing paragraphs, most journals require abstracts to conform to a formal structure within a word count of, usually, 200–250 words. The usual sections defined in a structured abstract are the Background, Methods, Results, and Conclusions; other headings with similar meanings may be used (eg, Introduction in place of Background or Findings in place of Results). Some journals include additional sections, such as Objectives (between Background and Methods) and Limitations (at the end of the abstract). In the rest of this paper, issues related to the contents of each section will be examined in turn.

This section should be the shortest part of the abstract and should very briefly outline the following information:

- What is already known about the subject, related to the paper in question

- What is not known about the subject and hence what the study intended to examine (or what the paper seeks to present)

In most cases, the background can be framed in just 2–3 sentences, with each sentence describing a different aspect of the information referred to above; sometimes, even a single sentence may suffice. The purpose of the background, as the word itself indicates, is to provide the reader with a background to the study, and hence to smoothly lead into a description of the methods employed in the investigation.

Some authors publish papers the abstracts of which contain a lengthy background section. There are some situations, perhaps, where this may be justified. In most cases, however, a longer background section means that less space remains for the presentation of the results. This is unfortunate because the reader is interested in the paper because of its findings, and not because of its background.

A wide variety of acceptably composed backgrounds is provided in Table 2 ; most of these have been adapted from actual papers.[ 4 – 9 ] Readers may wish to compare the content in Table 2 with the original abstracts to see how the adaptations possibly improve on the originals. Note that, in the interest of brevity, unnecessary content is avoided. For instance, in Example 1 there is no need to state “The antidepressant efficacy of desvenlafaxine (DV), a dual-acting antidepressant drug , has been established…” (the unnecessary content is italicized).

Examples of the background section of an abstract

The methods section is usually the second-longest section in the abstract. It should contain enough information to enable the reader to understand what was done, and how. Table 3 lists important questions to which the methods section should provide brief answers.

Questions regarding which information should ideally be available in the methods section of an abstract

Carelessly written methods sections lack information about important issues such as sample size, numbers of patients in different groups, doses of medications, and duration of the study. Readers have only to flip through the pages of a randomly selected journal to realize how common such carelessness is.

Table 4 presents examples of the contents of accept-ably written methods sections, modified from actual publications.[ 10 , 11 ] Readers are invited to take special note of the first sentence of each example in Table 4 ; each is packed with detail, illustrating how to convey the maximum quantity of information with maximum economy of word count.

Examples of the methods section of an abstract

The results section is the most important part of the abstract and nothing should compromise its range and quality. This is because readers who peruse an abstract do so to learn about the findings of the study. The results section should therefore be the longest part of the abstract and should contain as much detail about the findings as the journal word count permits. For example, it is bad writing to state “Response rates differed significantly between diabetic and nondiabetic patients.” A better sentence is “The response rate was higher in nondiabetic than in diabetic patients (49% vs 30%, respectively; P <0.01).”

Important information that the results should present is indicated in Table 5 . Examples of acceptably written abstracts are presented in Table 6 ; one of these has been modified from an actual publication.[ 11 ] Note that the first example is rather narrative in style, whereas the second example is packed with data.

Information that the results section of the abstract should ideally present

Examples of the results section of an abstract

CONCLUSIONS

This section should contain the most important take-home message of the study, expressed in a few precisely worded sentences. Usually, the finding highlighted here relates to the primary outcome measure; however, other important or unexpected findings should also be mentioned. It is also customary, but not essential, for the authors to express an opinion about the theoretical or practical implications of the findings, or the importance of their findings for the field. Thus, the conclusions may contain three elements:

- The primary take-home message

- The additional findings of importance

- The perspective

Despite its necessary brevity, this section has the most impact on the average reader because readers generally trust authors and take their assertions at face value. For this reason, the conclusions should also be scrupulously honest; and authors should not claim more than their data demonstrate. Hypothetical examples of the conclusions section of an abstract are presented in Table 7 .

Examples of the conclusions section of an abstract

MISCELLANEOUS OBSERVATIONS

Citation of references anywhere within an abstract is almost invariably inappropriate. Other examples of unnecessary content in an abstract are listed in Table 8 .

Examples of unnecessary content in a abstract

It goes without saying that whatever is present in the abstract must also be present in the text. Likewise, whatever errors should not be made in the text should not appear in the abstract (eg, mistaking association for causality).

As already mentioned, the abstract is the only part of the paper that the vast majority of readers see. Therefore, it is critically important for authors to ensure that their enthusiasm or bias does not deceive the reader; unjustified speculations could be even more harmful. Misleading readers could harm the cause of science and have an adverse impact on patient care.[ 12 ] A recent study,[ 13 ] for example, concluded that venlafaxine use during the second trimester of pregnancy may increase the risk of neonates born small for gestational age. However, nowhere in the abstract did the authors mention that these conclusions were based on just 5 cases and 12 controls out of the total sample of 126 cases and 806 controls. There were several other serious limitations that rendered the authors’ conclusions tentative, at best; yet, nowhere in the abstract were these other limitations expressed.

As a parting note: Most journals provide clear instructions to authors on the formatting and contents of different parts of the manuscript. These instructions often include details on what the sections of an abstract should contain. Authors should tailor their abstracts to the specific requirements of the journal to which they plan to submit their manuscript. It could also be an excellent idea to model the abstract of the paper, sentence for sentence, on the abstract of an important paper on a similar subject and with similar methodology, published in the same journal for which the manuscript is slated.

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

How to write a good abstract for a scientific paper or conference presentation

Affiliation.

- 1 Department of Psychopharmacology, National Institute of Mental Health and Neurosciences, Bangalore, Karnataka, India.

- PMID: 21772657

- PMCID: PMC3136027

- DOI: 10.4103/0019-5545.82558

s of scientific papers are sometimes poorly written, often lack important information, and occasionally convey a biased picture. This paper provides detailed suggestions, with examples, for writing the background, methods, results, and conclusions sections of a good abstract. The primary target of this paper is the young researcher; however, authors with all levels of experience may find useful ideas in the paper.

Keywords: Abstract; preparing a manuscript; writing skills.

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Dissertation

- How to Write an Abstract | Steps & Examples

How to Write an Abstract | Steps & Examples

Published on February 28, 2019 by Shona McCombes . Revised on July 18, 2023 by Eoghan Ryan.

An abstract is a short summary of a longer work (such as a thesis , dissertation or research paper ). The abstract concisely reports the aims and outcomes of your research, so that readers know exactly what your paper is about.

Although the structure may vary slightly depending on your discipline, your abstract should describe the purpose of your work, the methods you’ve used, and the conclusions you’ve drawn.

One common way to structure your abstract is to use the IMRaD structure. This stands for:

- Introduction

Abstracts are usually around 100–300 words, but there’s often a strict word limit, so make sure to check the relevant requirements.

In a dissertation or thesis , include the abstract on a separate page, after the title page and acknowledgements but before the table of contents .

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

Abstract example, when to write an abstract, step 1: introduction, step 2: methods, step 3: results, step 4: discussion, tips for writing an abstract, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about abstracts.

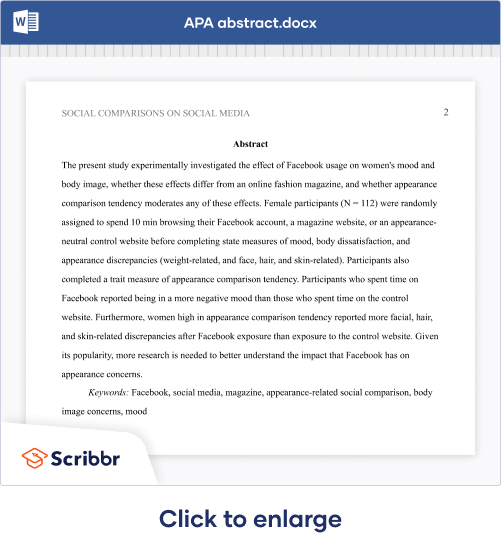

Hover over the different parts of the abstract to see how it is constructed.

This paper examines the role of silent movies as a mode of shared experience in the US during the early twentieth century. At this time, high immigration rates resulted in a significant percentage of non-English-speaking citizens. These immigrants faced numerous economic and social obstacles, including exclusion from public entertainment and modes of discourse (newspapers, theater, radio).

Incorporating evidence from reviews, personal correspondence, and diaries, this study demonstrates that silent films were an affordable and inclusive source of entertainment. It argues for the accessible economic and representational nature of early cinema. These concerns are particularly evident in the low price of admission and in the democratic nature of the actors’ exaggerated gestures, which allowed the plots and action to be easily grasped by a diverse audience despite language barriers.

Keywords: silent movies, immigration, public discourse, entertainment, early cinema, language barriers.

The only proofreading tool specialized in correcting academic writing - try for free!

The academic proofreading tool has been trained on 1000s of academic texts and by native English editors. Making it the most accurate and reliable proofreading tool for students.

Try for free

You will almost always have to include an abstract when:

- Completing a thesis or dissertation

- Submitting a research paper to an academic journal

- Writing a book or research proposal

- Applying for research grants

It’s easiest to write your abstract last, right before the proofreading stage, because it’s a summary of the work you’ve already done. Your abstract should:

- Be a self-contained text, not an excerpt from your paper

- Be fully understandable on its own

- Reflect the structure of your larger work

Start by clearly defining the purpose of your research. What practical or theoretical problem does the research respond to, or what research question did you aim to answer?

You can include some brief context on the social or academic relevance of your dissertation topic , but don’t go into detailed background information. If your abstract uses specialized terms that would be unfamiliar to the average academic reader or that have various different meanings, give a concise definition.

After identifying the problem, state the objective of your research. Use verbs like “investigate,” “test,” “analyze,” or “evaluate” to describe exactly what you set out to do.

This part of the abstract can be written in the present or past simple tense but should never refer to the future, as the research is already complete.

- This study will investigate the relationship between coffee consumption and productivity.

- This study investigates the relationship between coffee consumption and productivity.

Next, indicate the research methods that you used to answer your question. This part should be a straightforward description of what you did in one or two sentences. It is usually written in the past simple tense, as it refers to completed actions.

- Structured interviews will be conducted with 25 participants.

- Structured interviews were conducted with 25 participants.

Don’t evaluate validity or obstacles here — the goal is not to give an account of the methodology’s strengths and weaknesses, but to give the reader a quick insight into the overall approach and procedures you used.

Receive feedback on language, structure, and formatting

Professional editors proofread and edit your paper by focusing on:

- Academic style

- Vague sentences

- Style consistency

See an example

Next, summarize the main research results . This part of the abstract can be in the present or past simple tense.

- Our analysis has shown a strong correlation between coffee consumption and productivity.

- Our analysis shows a strong correlation between coffee consumption and productivity.

- Our analysis showed a strong correlation between coffee consumption and productivity.

Depending on how long and complex your research is, you may not be able to include all results here. Try to highlight only the most important findings that will allow the reader to understand your conclusions.

Finally, you should discuss the main conclusions of your research : what is your answer to the problem or question? The reader should finish with a clear understanding of the central point that your research has proved or argued. Conclusions are usually written in the present simple tense.

- We concluded that coffee consumption increases productivity.

- We conclude that coffee consumption increases productivity.

If there are important limitations to your research (for example, related to your sample size or methods), you should mention them briefly in the abstract. This allows the reader to accurately assess the credibility and generalizability of your research.

If your aim was to solve a practical problem, your discussion might include recommendations for implementation. If relevant, you can briefly make suggestions for further research.

If your paper will be published, you might have to add a list of keywords at the end of the abstract. These keywords should reference the most important elements of the research to help potential readers find your paper during their own literature searches.

Be aware that some publication manuals, such as APA Style , have specific formatting requirements for these keywords.

It can be a real challenge to condense your whole work into just a couple of hundred words, but the abstract will be the first (and sometimes only) part that people read, so it’s important to get it right. These strategies can help you get started.

Read other abstracts

The best way to learn the conventions of writing an abstract in your discipline is to read other people’s. You probably already read lots of journal article abstracts while conducting your literature review —try using them as a framework for structure and style.

You can also find lots of dissertation abstract examples in thesis and dissertation databases .

Reverse outline

Not all abstracts will contain precisely the same elements. For longer works, you can write your abstract through a process of reverse outlining.

For each chapter or section, list keywords and draft one to two sentences that summarize the central point or argument. This will give you a framework of your abstract’s structure. Next, revise the sentences to make connections and show how the argument develops.

Write clearly and concisely

A good abstract is short but impactful, so make sure every word counts. Each sentence should clearly communicate one main point.

To keep your abstract or summary short and clear:

- Avoid passive sentences: Passive constructions are often unnecessarily long. You can easily make them shorter and clearer by using the active voice.

- Avoid long sentences: Substitute longer expressions for concise expressions or single words (e.g., “In order to” for “To”).

- Avoid obscure jargon: The abstract should be understandable to readers who are not familiar with your topic.

- Avoid repetition and filler words: Replace nouns with pronouns when possible and eliminate unnecessary words.

- Avoid detailed descriptions: An abstract is not expected to provide detailed definitions, background information, or discussions of other scholars’ work. Instead, include this information in the body of your thesis or paper.

If you’re struggling to edit down to the required length, you can get help from expert editors with Scribbr’s professional proofreading services or use the paraphrasing tool .

Check your formatting

If you are writing a thesis or dissertation or submitting to a journal, there are often specific formatting requirements for the abstract—make sure to check the guidelines and format your work correctly. For APA research papers you can follow the APA abstract format .

Checklist: Abstract

The word count is within the required length, or a maximum of one page.

The abstract appears after the title page and acknowledgements and before the table of contents .

I have clearly stated my research problem and objectives.

I have briefly described my methodology .

I have summarized the most important results .

I have stated my main conclusions .

I have mentioned any important limitations and recommendations.

The abstract can be understood by someone without prior knowledge of the topic.

You've written a great abstract! Use the other checklists to continue improving your thesis or dissertation.

If you want to know more about AI for academic writing, AI tools, or research bias, make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples or go directly to our tools!

Research bias

- Anchoring bias

- Halo effect

- The Baader–Meinhof phenomenon

- The placebo effect

- Nonresponse bias

- Deep learning

- Generative AI

- Machine learning

- Reinforcement learning

- Supervised vs. unsupervised learning

(AI) Tools

- Grammar Checker

- Paraphrasing Tool

- Text Summarizer

- AI Detector

- Plagiarism Checker

- Citation Generator

An abstract is a concise summary of an academic text (such as a journal article or dissertation ). It serves two main purposes:

- To help potential readers determine the relevance of your paper for their own research.

- To communicate your key findings to those who don’t have time to read the whole paper.

Abstracts are often indexed along with keywords on academic databases, so they make your work more easily findable. Since the abstract is the first thing any reader sees, it’s important that it clearly and accurately summarizes the contents of your paper.

An abstract for a thesis or dissertation is usually around 200–300 words. There’s often a strict word limit, so make sure to check your university’s requirements.

The abstract is the very last thing you write. You should only write it after your research is complete, so that you can accurately summarize the entirety of your thesis , dissertation or research paper .

Avoid citing sources in your abstract . There are two reasons for this:

- The abstract should focus on your original research, not on the work of others.

- The abstract should be self-contained and fully understandable without reference to other sources.

There are some circumstances where you might need to mention other sources in an abstract: for example, if your research responds directly to another study or focuses on the work of a single theorist. In general, though, don’t include citations unless absolutely necessary.

The abstract appears on its own page in the thesis or dissertation , after the title page and acknowledgements but before the table of contents .

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

McCombes, S. (2023, July 18). How to Write an Abstract | Steps & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved April 11, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/dissertation/abstract/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, how to write a thesis or dissertation introduction, shorten your abstract or summary, how to write a literature review | guide, examples, & templates, unlimited academic ai-proofreading.

✔ Document error-free in 5minutes ✔ Unlimited document corrections ✔ Specialized in correcting academic texts

How to Write an Abstract for a Scientific Paper

- Chemical Laws

- Periodic Table

- Projects & Experiments

- Scientific Method

- Biochemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Medical Chemistry

- Chemistry In Everyday Life

- Famous Chemists

- Activities for Kids

- Abbreviations & Acronyms

- Weather & Climate

- Ph.D., Biomedical Sciences, University of Tennessee at Knoxville

- B.A., Physics and Mathematics, Hastings College

If you're preparing a research paper or grant proposal, you'll need to know how to write an abstract. Here's a look at what an abstract is and how to write one.

An abstract is a concise summary of an experiment or research project. It should be brief -- typically under 200 words. The purpose of the abstract is to summarize the research paper by stating the purpose of the research, the experimental method, the findings, and the conclusions.

- How to Write an Abstract

The format you'll use for the abstract depends on its purpose. If you're writing for a specific publication or a class assignment, you'll probably need to follow specific guidelines. If there isn't a required format, you'll need to choose from one of two possible types of abstracts.

Informational Abstracts

An informational abstract is a type of abstract used to communicate an experiment or lab report .

- An informational abstract is like a mini-paper. Its length ranges from a paragraph to 1 to 2 pages, depending on the scope of the report. Aim for less than 10% the length of the full report.

- Summarize all aspects of the report, including purpose, method, results, conclusions, and recommendations. There are no graphs, charts, tables, or images in an abstract. Similarly, an abstract does not include a bibliography or references.

- Highlight important discoveries or anomalies. It's okay if the experiment did not go as planned and necessary to state the outcome in the abstract.

Here is a good format to follow, in order, when writing an informational abstract. Each section is a sentence or two long:

- Motivation or Purpose: State why the subject is important or why anyone should care about the experiment and its results.

- Problem: State the hypothesis of the experiment or describe the problem you are trying to solve.

- Method: How did you test the hypothesis or try to solve the problem?

- Results: What was the outcome of the study? Did you support or reject a hypothesis? Did you solve a problem? How close were the results to what you expected? State-specific numbers.

- Conclusions: What is the significance of your findings? Do the results lead to an increase in knowledge, a solution that may be applied to other problems, etc.?

Need examples? The abstracts at PubMed.gov (National Institutes of Health database) are informational abstracts. A random example is this abstract on the effect of coffee consumption on Acute Coronary Syndrome .

Descriptive Abstracts

A descriptive abstract is an extremely brief description of the contents of a report. Its purpose is to tell the reader what to expect from the full paper.

- A descriptive abstract is very short, typically less than 100 words.

- Tells the reader what the report contains, but doesn't go into detail.

- It briefly summarizes the purpose and experimental method, but not the results or conclusions. Basically, say why and how the study was made, but don't go into findings.

Tips for Writing a Good Abstract

- Write the paper before writing the abstract. You might be tempted to start with the abstract since it comes between the title page and the paper, but it's much easier to summarize a paper or report after it has been completed.

- Write in the third person. Replace phrases like "I found" or "we examined" with phrases like "it was determined" or "this paper provides" or "the investigators found".

- Write the abstract and then pare it down to meet the word limit. In some cases, a long abstract will result in automatic rejection for publication or a grade!

- Think of keywords and phrases a person looking for your work might use or enter into a search engine. Include those words in your abstract. Even if the paper won't be published, this is a good habit to develop.

- All information in the abstract must be covered in the body of the paper. Don't put a fact in the abstract that isn't described in the report.

- Proof-read the abstract for typos, spelling mistakes, and punctuation errors.

- Abstract Writing for Sociology

- How to Write a Science Fair Project Report

- How to Format a Biology Lab Report

- Six Steps of the Scientific Method

- How to Write a Lab Report

- Science Lab Report Template - Fill in the Blanks

- An Introduction to Academic Writing

- Null Hypothesis Definition and Examples

- Scientific Method Flow Chart

- How To Design a Science Fair Experiment

- How to Write a Research Paper That Earns an A

- What Is Depth of Knowledge?

- What Is a Testable Hypothesis?

- How to Write a Great Book Report

Important Tips for Writing an Effective Conference Abstract

Academic conferences are an important part of graduate work. They offer researchers an opportunity to present their work and network with other researchers. So, how does a researcher get invited to present their work at an academic conference ? The first step is to write and submit an abstract of your research paper .

The purpose of a conference abstract is to summarize the main points of your paper that you will present in the academic conference. In it, you need to convince conference organizers that you have something important and valuable to add to the conference. Therefore, it needs to be focused and clear in explaining your topic and the main points of research that you will share with the audience.

The Main Points of a Conference Abstract

There are some general formulas for creating a conference abstract .

Formula : topic + title + motivation + problem statement + approach + results + conclusions = conference abstract

Here are the main points that you need to include.

The title needs to grab people’s attention. Most importantly, it needs to state your topic clearly and develop interest. This will give organizers an idea of how your paper fits the focus of the conference.

Problem Statement

You should state the specific problem that you are trying to solve.

The abstract needs to illustrate the purpose of your work. This is the point that will help the conference organizer determine whether or not to include your paper in a conference session.

You have a problem before you: What approach did you take towards solving the problem? You can include how you organized this study and the research that you used.

Important Things to Know When Developing Your Abstract

Do your research on the conference.

You need to know the deadline for abstract submissions. And, you should submit your abstract as early as possible.

Do some research on the conference to see what the focus is and how your topic fits. This includes looking at the range of sessions that will be at the conference. This will help you see which specific session would be the best fit for your paper.

Select Your Keywords Carefully

Keywords play a vital role in increasing the discoverability of your article. Use the keywords that most appropriately reflect the content of your article.

Once you are clear on the topic of the conference, you can tailor your abstract to fit specific sessions.

An important part of keeping your focus is knowing the word limit for the abstract. Most word limits are around 250-300 words. So, be concise.

Use Example Abstracts as a Guide

Looking at examples of abstracts is always a big help. Look at general examples of abstracts and examples of abstracts in your field. Take notes to understand the main points that make an abstract effective.

Avoid Fillers and Jargon

As stated earlier, abstracts are supposed to be concise, yet informative. Avoid using words or phrases that do not add any specific value to your research. Keep the sentences short and crisp to convey just as much information as needed.

Edit with a Fresh Mind

After you write your abstract, step away from it. Then, look it over with a fresh mind. This will help you edit it to improve its effectiveness. In addition, you can also take the help of professional editing services that offer quick deliveries.

Remain Focused and Establish Your Ideas

The main point of an abstract is to catch the attention of the conference organizers. So, you need to be focused in developing the importance of your work. You want to establish the importance of your ideas in as little as 250-300 words.

Have you attended a conference as a student? What experiences do you have with conference abstracts? Please share your ideas in the comments. You can also visit our Q&A forum for frequently asked questions related to different aspects of research writing, presenting, and publishing answered by our team that comprises subject-matter experts, eminent researchers, and publication experts.

best article to write a good abstract

Excellent guidelines for writing a good abstract.

Rate this article Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published.

Enago Academy's Most Popular Articles

- Career Corner

- Trending Now

Recognizing the signs: A guide to overcoming academic burnout

As the sun set over the campus, casting long shadows through the library windows, Alex…

- Diversity and Inclusion

Reassessing the Lab Environment to Create an Equitable and Inclusive Space

The pursuit of scientific discovery has long been fueled by diverse minds and perspectives. Yet…

- AI in Academia

- Reporting Research

How to Improve Lab Report Writing: Best practices to follow with and without AI-assistance

Imagine you’re a scientist who just made a ground-breaking discovery! You want to share your…

Achieving Research Excellence: Checklist for good research practices

Academia is built on the foundation of trustworthy and high-quality research, supported by the pillars…

- Promoting Research

Concept Papers in Research: Deciphering the blueprint of brilliance

Concept papers hold significant importance as a precursor to a full-fledged research proposal in academia…

7 Steps of Writing an Excellent Academic Book Chapter

When Your Thesis Advisor Asks You to Quit

Virtual Defense: Top 5 Online Thesis Defense Tips

Sign-up to read more

Subscribe for free to get unrestricted access to all our resources on research writing and academic publishing including:

- 2000+ blog articles

- 50+ Webinars

- 10+ Expert podcasts

- 50+ Infographics

- 10+ Checklists

- Research Guides

We hate spam too. We promise to protect your privacy and never spam you.

I am looking for Editing/ Proofreading services for my manuscript Tentative date of next journal submission:

What should universities' stance be on AI tools in research and academic writing?

Europe PMC requires Javascript to function effectively.

Either your web browser doesn't support Javascript or it is currently turned off. In the latter case, please turn on Javascript support in your web browser and reload this page.

Search life-sciences literature (43,910,776 articles, preprints and more)

- Free full text

- Citations & impact

- Similar Articles

How to write a good abstract for a scientific paper or conference presentation.

Author information, affiliations.

- Andrade C 1

Indian Journal of Psychiatry , 01 Apr 2011 , 53(2): 172-175 https://doi.org/10.4103/0019-5545.82558 PMID: 21772657 PMCID: PMC3136027

Abstract

Free full text , how to write a good abstract for a scientific paper or conference presentation, chittaranjan andrade.

Department of Psychopharmacology, National Institute of Mental Health and Neurosciences, Bangalore, Karnataka, India

Abstracts of scientific papers are sometimes poorly written, often lack important information, and occasionally convey a biased picture. This paper provides detailed suggestions, with examples, for writing the background, methods, results, and conclusions sections of a good abstract. The primary target of this paper is the young researcher; however, authors with all levels of experience may find useful ideas in the paper.

- INTRODUCTION

This paper is the third in a series on manuscript writing skills, published in the Indian Journal of Psychiatry . Earlier articles offered suggestions on how to write a good case report,[ 1 ] and how to read, write, or review a paper on randomized controlled trials.[ 2 , 3 ] The present paper examines how authors may write a good abstract when preparing their manuscript for a scientific journal or conference presentation. Although the primary target of this paper is the young researcher, it is likely that authors with all levels of experience will find at least a few ideas that may be useful in their future efforts.

The abstract of a paper is the only part of the paper that is published in conference proceedings. The abstract is the only part of the paper that a potential referee sees when he is invited by an editor to review a manuscript. The abstract is the only part of the paper that readers see when they search through electronic databases such as PubMed. Finally, most readers will acknowledge, with a chuckle, that when they leaf through the hard copy of a journal, they look at only the titles of the contained papers. If a title interests them, they glance through the abstract of that paper. Only a dedicated reader will peruse the contents of the paper, and then, most often only the introduction and discussion sections. Only a reader with a very specific interest in the subject of the paper, and a need to understand it thoroughly, will read the entire paper.

Thus, for the vast majority of readers, the paper does not exist beyond its abstract. For the referees, and the few readers who wish to read beyond the abstract, the abstract sets the tone for the rest of the paper. It is therefore the duty of the author to ensure that the abstract is properly representative of the entire paper. For this, the abstract must have some general qualities. These are listed in Table 1 .

General qualities of a good abstract

- SECTIONS OF AN ABSTRACT

Although some journals still publish abstracts that are written as free-flowing paragraphs, most journals require abstracts to conform to a formal structure within a word count of, usually, 200–250 words. The usual sections defined in a structured abstract are the Background, Methods, Results, and Conclusions; other headings with similar meanings may be used (eg, Introduction in place of Background or Findings in place of Results). Some journals include additional sections, such as Objectives (between Background and Methods) and Limitations (at the end of the abstract). In the rest of this paper, issues related to the contents of each section will be examined in turn.

This section should be the shortest part of the abstract and should very briefly outline the following information:

What is already known about the subject, related to the paper in question

What is not known about the subject and hence what the study intended to examine (or what the paper seeks to present)

In most cases, the background can be framed in just 2–3 sentences, with each sentence describing a different aspect of the information referred to above; sometimes, even a single sentence may suffice. The purpose of the background, as the word itself indicates, is to provide the reader with a background to the study, and hence to smoothly lead into a description of the methods employed in the investigation.

Some authors publish papers the abstracts of which contain a lengthy background section. There are some situations, perhaps, where this may be justified. In most cases, however, a longer background section means that less space remains for the presentation of the results. This is unfortunate because the reader is interested in the paper because of its findings, and not because of its background.

A wide variety of acceptably composed backgrounds is provided in Table 2 ; most of these have been adapted from actual papers.[ 4 – 9 ] Readers may wish to compare the content in Table 2 with the original abstracts to see how the adaptations possibly improve on the originals. Note that, in the interest of brevity, unnecessary content is avoided. For instance, in Example 1 there is no need to state “The antidepressant efficacy of desvenlafaxine (DV), a dual-acting antidepressant drug , has been established…” (the unnecessary content is italicized).

Examples of the background section of an abstract

The methods section is usually the second-longest section in the abstract. It should contain enough information to enable the reader to understand what was done, and how. Table 3 lists important questions to which the methods section should provide brief answers.

Questions regarding which information should ideally be available in the methods section of an abstract

Carelessly written methods sections lack information about important issues such as sample size, numbers of patients in different groups, doses of medications, and duration of the study. Readers have only to flip through the pages of a randomly selected journal to realize how common such carelessness is.

Table 4 presents examples of the contents of accept-ably written methods sections, modified from actual publications.[ 10 , 11 ] Readers are invited to take special note of the first sentence of each example in Table 4 ; each is packed with detail, illustrating how to convey the maximum quantity of information with maximum economy of word count.

Examples of the methods section of an abstract

The results section is the most important part of the abstract and nothing should compromise its range and quality. This is because readers who peruse an abstract do so to learn about the findings of the study. The results section should therefore be the longest part of the abstract and should contain as much detail about the findings as the journal word count permits. For example, it is bad writing to state “Response rates differed significantly between diabetic and nondiabetic patients.” A better sentence is “The response rate was higher in nondiabetic than in diabetic patients (49% vs 30%, respectively; P <0.01).”

Important information that the results should present is indicated in Table 5 . Examples of acceptably written abstracts are presented in Table 6 ; one of these has been modified from an actual publication.[ 11 ] Note that the first example is rather narrative in style, whereas the second example is packed with data.

Information that the results section of the abstract should ideally present

Examples of the results section of an abstract

- CONCLUSIONS

This section should contain the most important take-home message of the study, expressed in a few precisely worded sentences. Usually, the finding highlighted here relates to the primary outcome measure; however, other important or unexpected findings should also be mentioned. It is also customary, but not essential, for the authors to express an opinion about the theoretical or practical implications of the findings, or the importance of their findings for the field. Thus, the conclusions may contain three elements:

The primary take-home message

The additional findings of importance

The perspective

Despite its necessary brevity, this section has the most impact on the average reader because readers generally trust authors and take their assertions at face value. For this reason, the conclusions should also be scrupulously honest; and authors should not claim more than their data demonstrate. Hypothetical examples of the conclusions section of an abstract are presented in Table 7 .

Examples of the conclusions section of an abstract

- MISCELLANEOUS OBSERVATIONS

Citation of references anywhere within an abstract is almost invariably inappropriate. Other examples of unnecessary content in an abstract are listed in Table 8 .

Examples of unnecessary content in a abstract

It goes without saying that whatever is present in the abstract must also be present in the text. Likewise, whatever errors should not be made in the text should not appear in the abstract (eg, mistaking association for causality).

As already mentioned, the abstract is the only part of the paper that the vast majority of readers see. Therefore, it is critically important for authors to ensure that their enthusiasm or bias does not deceive the reader; unjustified speculations could be even more harmful. Misleading readers could harm the cause of science and have an adverse impact on patient care.[ 12 ] A recent study,[ 13 ] for example, concluded that venlafaxine use during the second trimester of pregnancy may increase the risk of neonates born small for gestational age. However, nowhere in the abstract did the authors mention that these conclusions were based on just 5 cases and 12 controls out of the total sample of 126 cases and 806 controls. There were several other serious limitations that rendered the authors’ conclusions tentative, at best; yet, nowhere in the abstract were these other limitations expressed.

As a parting note: Most journals provide clear instructions to authors on the formatting and contents of different parts of the manuscript. These instructions often include details on what the sections of an abstract should contain. Authors should tailor their abstracts to the specific requirements of the journal to which they plan to submit their manuscript. It could also be an excellent idea to model the abstract of the paper, sentence for sentence, on the abstract of an important paper on a similar subject and with similar methodology, published in the same journal for which the manuscript is slated.

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

Full text links

Read article at publisher's site: https://doi.org/10.4103/0019-5545.82558

Citations & impact

Impact metrics, citations of article over time, alternative metrics.

Article citations

How to make your abstract noticeable during submission for paper presentation in a conference: points to ponder.

Ahuja V , Theerth K , Garg R

Indian J Anaesth , 68(suppl 1):S6-S7, 23 Feb 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 38481734 | PMCID: PMC10929758

Writing a Scientific Review Article: Comprehensive Insights for Beginners.

Amobonye A , Lalung J , Mheta G , Pillai S

ScientificWorldJournal , 2024:7822269, 17 Jan 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 38268745

Evaluation of Spin in the Clinical Literature of Suture Tape Augmentation for Ankle Instability.

Thompson AA , Hwang NM , Mayfield CK , Petrigliano FA , Liu JN , Peterson AB

Foot Ankle Orthop , 8(2):24730114231179218, 01 Apr 2023

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 37325695 | PMCID: PMC10262628

Did AI get more negative recently?

Beese D , Altunbaş B , Güzeler G , Eger S

R Soc Open Sci , 10(3):221159, 08 Mar 2023

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 36908991 | PMCID: PMC9993047

Reporting quality of abstracts from randomised controlled trials published in leading critical care nursing journals: a methodological quality review.

Villa M , Le Pera M , Cassina T , Bottega M

BMJ Open , 13(3):e070639, 15 Mar 2023

Cited by: 1 article | PMID: 36921935 | PMCID: PMC10030738

Similar Articles

To arrive at the top five similar articles we use a word-weighted algorithm to compare words from the Title and Abstract of each citation.

Rules to be adopted for publishing a scientific paper.

Ann Ital Chir , 87:1-3, 01 Jan 2016

Cited by: 5 articles | PMID: 28474609

[Personal suggestions to write and publish SCI cited papers].

Shanghai Kou Qiang Yi Xue , 15(2):221-223, 01 Apr 2006

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 16685372

How to write and publish scientific papers: scribing information for pharmacists.

Hamilton CW

Am J Hosp Pharm , 49(10):2477-2484, 01 Oct 1992

Cited by: 2 articles | PMID: 1442826

How to write a research paper.

Alexandrov AV

Cerebrovasc Dis , 18(2):135-138, 23 Jun 2004

Cited by: 20 articles | PMID: 15218279

[Introduction on how to write a scientific abstract].

Kaspersen AE , Hasenkam JM , Leipziger JG , Djurhuus JC

Ugeskr Laeger , 181(21):V02190103, 01 May 2019

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 31124438

Europe PMC is part of the ELIXIR infrastructure

- About the LSE Impact Blog

- Comments Policy

- Popular Posts

- Recent Posts

- Subscribe to the Impact Blog

- Write for us

- LSE comment

January 27th, 2015

How to write a killer conference abstract: the first step towards an engaging presentation..

34 comments | 130 shares

Estimated reading time: 6 minutes

Helen Kara responds to our previously published guide to writing abstracts and elaborates specifically on the differences for conference abstracts. She offers tips for writing an enticing abstract for conference organisers and an engaging conference presentation. Written grammar is different from spoken grammar. Remember that conference organisers are trying to create as interesting and stimulating an event as they can, and variety is crucial.

Enjoying this blogpost? 📨 Sign up to our mailing list and receive all the latest LSE Impact Blog news direct to your inbox.

The Impact blog has an ‘essential ‘how-to’ guide to writing good abstracts’ . While this post makes some excellent points, its title and first sentence don’t differentiate between article and conference abstracts. The standfirst talks about article abstracts, but then the first sentence is, ‘Abstracts tend to be rather casually written, perhaps at the beginning of writing when authors don’t yet really know what they want to say, or perhaps as a rushed afterthought just before submission to a journal or a conference.’ This, coming so soon after the title, gives the impression that the post is about both article and conference abstracts.

I think there are some fundamental differences between the two. For example:

- Article abstracts are presented to journal editors along with the article concerned. Conference abstracts are presented alone to conference organisers. This means that journal editors or peer reviewers can say e.g. ‘great article but the abstract needs work’, while a poor abstract submitted to a conference organiser is very unlikely to be accepted.

- Articles are typically 4,000-8,000 words long. Conference presentation slots usually allow 20 minutes so, given that – for good listening comprehension – presenters should speak at around 125 words per minute, a conference presentation should be around 2,500 words long.

- Articles are written to be read from the page, while conference presentations are presented in person. Written grammar is different from spoken grammar, and there is nothing so tedious for a conference audience than the old-skool approach of reading your written presentation from the page. Fewer people do this now – but still, too many. It’s unethical to bore people! You need to engage your audience, and conference organisers will like to know how you intend to hold their interest.

Image credit: allanfernancato ( Pixabay, CC0 Public Domain )

The competition for getting a conference abstract accepted is rarely as fierce as the competition for getting an article accepted. Some conferences don’t even receive as many abstracts as they have presentation slots. But even then, they’re more likely to re-arrange their programme than to accept a poor quality abstract. And you can’t take it for granted that your abstract won’t face much competition. I’ve recently read over 90 abstracts submitted for the Creative Research Methods conference in May – for 24 presentation slots. As a result, I have four useful tips to share with you about how to write a killer conference abstract.

First , your conference abstract is a sales tool: you are selling your ideas, first to the conference organisers, and then to the conference delegates. You need to make your abstract as fascinating and enticing as possible. And that means making it different. So take a little time to think through some key questions:

- What kinds of presentations is this conference most likely to attract? How can you make yours different?

- What are the fashionable areas in your field right now? Are you working in one of these areas? If so, how can you make your presentation different from others doing the same? If not, how can you make your presentation appealing?

There may be clues in the call for papers, so study this carefully. For example, we knew that the Creative Research Methods conference , like all general methods conferences, was likely to receive a majority of abstracts covering data collection methods. So we stated up front, in the call for papers, that we knew this was likely, and encouraged potential presenters to offer creative methods of planning research, reviewing literature, analysing data, writing research, and so on. Even so, around three-quarters of the abstracts we received focused on data collection. This meant that each of those abstracts was less likely to be accepted than an abstract focusing on a different aspect of the research process, because we wanted to offer delegates a good balance of presentations.

Currently fashionable areas in the field of research methods include research using social media and autoethnography/ embodiment. We received quite a few abstracts addressing these, but again, in the interests of balance, were only likely to accept one (at most) in each area. Remember that conference organisers are trying to create as interesting and stimulating an event as they can, and variety is crucial.

Second , write your abstract well. Unless your abstract is for a highly academic and theoretical conference, wear your learning lightly. Engaging concepts in plain English, with a sprinkling of references for context, is much more appealing to conference organisers wading through sheaves of abstracts than complicated sentences with lots of long words, definitions of terms, and several dozen references. Conference organisers are not looking for evidence that you can do really clever writing (save that for your article abstracts), they are looking for evidence that you can give an entertaining presentation.

Third , conference abstracts written in the future tense are off-putting for conference organisers, because they don’t make it clear that the potential presenter knows what they’ll be talking about. I was surprised by how many potential presenters did this. If your presentation will include information about work you’ll be doing in between the call for papers and the conference itself (which is entirely reasonable as this can be a period of six months or more), then make that clear. So, for example, don’t say, ‘This presentation will cover the problems I encounter when I analyse data with homeless young people, and how I solve those problems’, say, ‘I will be analysing data with homeless young people over the next three months, and in the following three months I will prepare a presentation about the problems we encountered while doing this and how we tackled those problems’.

Fourth , of course you need to tell conference organisers about your research: its context, method, and findings. It will also help enormously if you can take a sentence or three to explain what you intend to include in the presentation itself. So, perhaps something like, ‘I will briefly outline the process of participatory data analysis we developed, supported by slides. I will then show a two-minute video which will illustrate both the process in action and some of the problems encountered. After that, again using slides, I will outline each of the problems and how we tackled them in practice.’ This will give conference organisers some confidence that you can actually put together and deliver an engaging presentation.

So, to summarise, to maximise your chances of success when submitting conference abstracts:

- Make your abstract fascinating, enticing, and different.

- Write your abstract well, using plain English wherever possible.

- Don’t write in the future tense if you can help it – and, if you must, specify clearly what you will do and when.

- Explain your research, and also give an explanation of what you intend to include in the presentation.

While that won’t guarantee success, it will massively increase your chances. Best of luck!

This post originally appeared on the author’s personal blog and is reposted with permission.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Impact of Social Science blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Please review our Comments Policy if you have any concerns on posting a comment below.

About the Author

Dr Helen Kara has been an independent social researcher in social care and health since 1999, and is an Associate Research Fellow at the Third Sector Research Centre , University of Birmingham. She is on the Board of the UK’s Social Research Association , with lead responsibility for research ethics. She also teaches research methods to practitioners and students, and writes on research methods. Helen is the author of Research and Evaluation for Busy Practitioners (2012) and Creative Research Methods in the Social Sciences (April 2015) , both published by Policy Press . She did her first degree in Social Psychology at the LSE.

About the author

Dr Helen Kara has been an independent researcher since 1999 and also teaches research methods and ethics. She is not, and never has been, an academic, though she has learned to speak the language. In 2015 Helen was the first fully independent researcher to be conferred as a Fellow of the Academy of Social Sciences. She is also an Honorary Senior Research Fellow at the Cathie Marsh Institute for Social Research, University of Manchester. She has written widely on research methods and ethics, including Research Ethics in the Real World: Euro-Western and Indigenous Perspectives (2018, Policy Press).

34 Comments

Personally, I’d rather not see reading a presentation written off so easily, for three off the cuff reasons:

1) Reading can be done really well, especially if the paper was written to be read.

2) It seems to be well suited to certain kinds of qualitative studies, particularly those that are narrative driven.

3) It seems to require a different kind of focus or concentration — one that requires more intensive listening (as opposed to following an outline driven presentation that’s supplemented with visuals, i.e., slides).

Admittedly, I’ve read some papers before, and writing them to be read can be a rewarding process, too. I had to pay attention to details differently: structure, tone, story, etc. It can be an insightful process, especially for works in progress.

Sean, thanks for your comment, which I think is a really useful addition to the discussion. I’ve sat through so many turgid not-written-to-be-read presentations that it never occurred to me they could be done well until I heard your thoughts. What you say makes a great deal of sense to me, particularly with presentations that are consciously ‘written to be read’ out loud. I think where they can get tedious is where a paper written for the page is read out loud instead, because for me that really doesn’t work. But I love to listen to stories, and I think of some of the quality storytelling that is broadcast on radio, and of audiobooks that work well (again, in my experience, they don’t all), and I do entirely see your point.

Helen, I appreciate your encouraging me remark on such a minor part of your post(!), which I enjoyed reading and will share. And thank you for the reply and the exchange on Twitter.

Very much enjoyed your post Helen. And your subsequent comments Sean. On the subject of the reading of a presentation. I agree that some people can write a paper specifically to be read and this can be done well. But I would think that this is a dying art. Perhaps in the humanities it might survive longer. Reading through the rest of your post I love the advice. I’m presenting at my first LIS conference next month and had I read your post first I probably would have written it differently. Advice for the future for me.

Martin – and Sean – thank you so much for your kind comments. Maybe there are steps we can take to keep the art alive; advocates for it, such as Sean, will no doubt help. And, Martin, if you’re presenting next month, you must have done perfectly well all by yourself! Congratulations on the acceptance, and best of luck for the presentation.

Great article! Obvious at it may seem, a point zero may be added before the other four: which _are_ your ideas?

A scientific writing coach told me she often runs a little exercise with her students. She tells them to put away their (journal) abstract and then asks them to summarize the bottom line in three statements. After some thinking, the students come up with an answer. Then the coach tells the students to reach for the abstract, read it and look for the bottom line they just summarised. Very often, they find that their own main observations and/or conclusions are not clearly expressed in the abstract.

PS I love the line “It’s unethical to bore people!” 🙂

Thanks for your comment, Olle – that’s a great point. I think something happens to us when we’re writing, in which we become so clear about what we want to say that we think we’ve said it even when we haven’t. Your friend’s exercise sounds like a great trick for finding out when we’ve done that. And thanks for the compliments, too!

- Pingback: How to write a conference abstract | Blog @HEC Paris Library

- Pingback: Writer’s Paralysis | Helen Kara

- Pingback: Weekend reads: - Retraction Watch at Retraction Watch

- Pingback: The Weekly Roundup | The Graduate School

- Pingback: My Top 10 Abstract Writing tips | Jon Rainford's Blog

- Pingback: Review of the Year 2015 | Helen Kara

- Pingback: Impact of Social Sciences – 2015 Year-In-Review: LSE Impact Blog’s Most Popular Posts

Thank you very much for the tips, they are really helpful. I have actually been accepted to present a PuchaKucha presentation in an educational interdisciplinary conference at my university. my presentation would be about the challenges faced by women in my country. So, it would be just a review of the literature. from what I’ve been reading, conferences are about new research and your new ideas… Is what I’m doing wrong??? that’s my first conference I’ll be speaking in and I’m afraid to ruin it!!! I will be really grateful about any advice ^_^

First of all: you’re not going to ruin the conference, even if you think you made a bad presentation. You should always remember that people are not very concerned about you–they are mostly concerned about themselves. Take comfort in that thought!

Here are some notes: • If it is a Pecha Kucha night, you stand in front of a mixed audience. Remember that scientists understand layman’s stuff, but laymen don’t understand scientists stuff. • Pecha Kucha is also very VISUAL! Remember that you can’t control the flow of slides – they change every 20 seconds. • Make your main messages clear. You can use either one of these templates.

A. Which are the THREE most important observations, conclusions, implications or messages from your study?

B. Inform them! (LOGOS) Engage them! (PATHOS) Make an impression! (ETHOS)

C. What do you do as a scientist/is a study about? What problem(s) do you address? How is your research different? Why should I care?

Good luck and remember to focus on (1) the audience, (2) your mission, (3) your stuff and (4) yourself, in that order.

- Pingback: How to choose a conference then write an abstract that gets you noticed | The Research Companion

- Pingback: Impact of Social Sciences – Impact Community Insights: Five things we learned from our Reader Survey and Google Analytics.

- Pingback: Giving Us The Space To Think Things Through… | Research Into Practice Group

- Pingback: The Scholar-Practitioner Paradox for Academic Writing [@BreakDrink Episode No. 8] – techKNOWtools

I don’t know whether it’s just me or if perhaps everybody else encountering problems with your site. It appears as if some of the text in your content are running off the screen. Can someone else please comment and let me know if this is happening to them as well? This could be a issue with my browser because I’ve had this happen before. Thank you

- Pingback: Exhibition, abstracts and a letter from Prince Harry – EAHIL 2018

- Pingback: How to write a great abstract | DEWNR-NRM-Science-Conference

- Pingback: Abstracting and postering for conferences – ECRAG

Thank you Dr Kara for the great guide on creating killer abstracts for conferences. I am preparing to write an abstract for my first conference presentation and this has been educative and insightful. ‘ I choose to be ethical and not bore my audience’.

Thank you Judy for your kind comment. I wish you luck with your abstract and your presentation. Helen

- Pingback: Tips to Write a Strong Abstract for a Conference Paper – Research Synergy Institute

Dear Dr. Helen Kara, Can there be an abstract for a topic presentation? I need to present a topic in a conference.I searched in the net and couldnt find anything like an abstract for a topic presentation but only found abstract for article presentation. Urgent.Help!

Dear Rekha Sthapit, I think it would be the same – but if in doubt, you could ask the conference organisers to clarify what they mean by ‘topic presentation’. Good luck!

- Pingback: 2020: The Top Posts of the Decade | Impact of Social Sciences

- Pingback: Capturing the abstract: what ARE conference abstracts and what are they FOR? (James Burford & Emily F. Henderson) – Conference Inference

- Pingback: LSEUPR 2022 Conference | LSE Undergraduate Political Review

- Pingback: New Occupational Therapy Research Conference: Integrating research into your role – Glasgow Caledonian University Occupational Therapy Blog

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Notify me of follow-up comments by email.

Related Posts

‘It could be effective…’: Uncertainty and over-promotion in the abstracts of COVID-19 preprints

September 30th, 2021.

How to design an award-winning conference poster

May 11th, 2018.

Are scientific findings exaggerated? Study finds steady increase of superlatives in PubMed abstracts.

January 26th, 2016.

An antidote to futility: Why academics (and students) should take blogging / social media seriously

October 26th, 2015.

Visit our sister blog LSE Review of Books

- Search Menu

- Advance Articles

- Editor's Choice

- CME Reviews

- Best of 2021 collection

- Abbreviated Breast MRI Virtual Collection

- Contrast-enhanced Mammography Collection

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Accepted Papers Resource Guide

- About Journal of Breast Imaging

- About the Society of Breast Imaging

- Guidelines for Reviewers

- Resources for Reviewers and Authors

- Editorial Board

- Advertising Disclaimer

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

Conclusions, conflict of interest statement.

- < Previous

How to Write a Scientific Abstract for Symposium Submission †

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Dianne Georgian-Smith, Jessica Leung, John Lewin, Emily F Conant, Margarita Zuley, How to Write a Scientific Abstract for Symposium Submission, Journal of Breast Imaging , Volume 1, Issue 3, September 2019, Pages 159–160, https://doi.org/10.1093/jbi/wbz037

- Permissions Icon Permissions

The expansion of the Society of Breast Imaging (SBI), now with annual symposiums and a new journal, offers more opportunities for radiologists to share academic ideas and achieve peer-reviewed recognition for their scientific and educational work. Specifically, the process of designing and completing a research project often passes through the steps of presenting work at a scientific session of a conference and ultimately to publication of a manuscript. For acceptance as a presentation, the investigating team must compose and submit an abstract, summarizing pertinent findings to pique the interest of the abstract reviewers for the meeting. Unlike manuscript reviews, there is no feedback to abstract authors giving reasons for rejection. Thus, the learning curve for creating successful abstract submissions may be one of trial-and-error. Therefore, suggestions on formatting an abstract are presented.

The process of writing an abstract for presentation at a scientific session is different from the writing of a manuscript because sometimes the abstract submission may occur before completion of the study, and the word or character limits are much more restrictive than those for a manuscript are. Importantly, data (albeit preliminary at times) must be included; scientific abstracts should not be “promissory notes” of potential future data. The purpose of this editorial is to highlight points to improve chances of acceptance.

The first goal is to state clearly and succinctly what was studied and why it was studied, using specific aims. The specific aims should be described in one to three focused statements. If word limit permits, one background sentence at the beginning of the paragraph justifying why the study was conducted may be helpful, but it is not always necessary. The expectation is that the results presented in the abstract are tied directly to each specific aim.

A common mistake is to write one or two very general goals. The reviewer is subsequently “surprised” by the results because the aims had not been specifically laid out. The reviewer then needs to work to figure out what was done. This is not the role of the reviewer. It is the job of the primary investigator to outline the objectives of the study clearly. A good practice is to articulate to a colleague what was studied, using one sentence per aim. Remember that reviewers have many abstracts to evaluate. If an abstract is confusing, wordy, and laborious, it may end up with a less-than-favorable rank, regardless of the merits of the project.

This section is the key to success! The significance of the results is completely based on how the study was conducted. Take your time to be succinct and specific, yet provide sufficient details so that the study can be reconstructed by the reader.

In the first sentence, state the form of study: prospective versus retrospective, randomized-controlled, matched case-controlled, observational reader study, etc., and include if the study was approved by an institutional review board or internal quality board, and if patient consent was obtained or waived. Next, describe the selection process of cases and/or readers and inclusion/exclusion criteria. Include data sources (eg, Electronic Medical Record, Radiology Information System, research database, etc.), and the time frame of the cohort. This is the portion of the abstract where the reviewer is looking for selection biases that will affect the results. Lastly, note how the collected data were statistically analyzed to determine significance.

At the time of writing the abstract, the results should have been tabulated, and if pertinent, statistical significance should have been calculated. This section is therefore the easiest to write. The results section should be formatted to reflect each specific aim in the order they were listed in the objectives section. If space allows, subaims per specific aim can be presented, but not at the expense of leaving out the key results of a primary aim. Presenting the results in the order of the aims is a good outline to follow to reduce confusion for the reviewer. When presenting data, include the number, the total number, and the percent. Include statistical measures such as P values or confidence intervals as appropriate.

If a table or figure is allowed, choose carefully. This may be a way to include your primary results without including all of the numbers in the abstract. An example figure may be helpful for the reviewer if a new technique is being studied.

The purpose of the conclusions section is to summarize the clinical impact of the results. Every study should clearly answer the “So what?” question posed in the objective section, even when that question is implied and not spelled out. Can the results be generalized to other radiologists or practices? If the results cannot be applied or used by others because of lack of relevance, then there is little value in a general forum. The investigation may be very important for one’s personal or group practice, but those data are not applicable to a national meeting. Even when the effect on clinical practice is obvious, spell it out clearly in the conclusion section. The reviewer wants to know both if the investigators have thought about the results and whether they transcend the single practice or radiologist so that they are of interest to most of the audience.

In the recent annual SBI meeting, there were three oral scientific sessions with 20 abstracts selected from over 100 submissions. The Journal of Breast Imaging invites all investigators with accepted abstracts to submit manuscripts for peer review. This trend in increased research presentation bodes well for investigators to further individual careers and for the field of breast imaging.

None declared.

This article is submitted by selected members of the Abstract Review Committee.

Email alerts

Citing articles via.

- Recommend to your Librarian

- Journals Career Network

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 2631-6129

- Print ISSN 2631-6110

- Copyright © 2024 Society of Breast Imaging

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

INTRODUCTION. This paper is the third in a series on manuscript writing skills, published in the Indian Journal of Psychiatry.Earlier articles offered suggestions on how to write a good case report,[] and how to read, write, or review a paper on randomized controlled trials.[2,3] The present paper examines how authors may write a good abstract when preparing their manuscript for a scientific ...

DOI: 10.4103/0019-5545.82558. s of scientific papers are sometimes poorly written, often lack important information, and occasionally convey a biased picture. This paper provides detailed suggestions, with examples, for writing the background, methods, results, and conclusions sections of a good abstract. The primary target of t ….

What is an Abstract? •"The abstract is a brief, clear summary of the information in your presentation. A well-prepared abstract enables readers to identify the basic content quickly and accurately, to determine its relevance to their interests or purpose and then to decide whether they want to listen to the presentation in its entirety."

When an IMRaD paper or other presentable research is submitted to a conference, an abstract for the presentation will be submitted with it for the program. These abstracts are often the shortened version of the paper abstract; for example, an IMRaD abstract with max word count of 500 words will need to be shortened to fit a smaller max count ...

Step 2: Methods. Next, indicate the research methods that you used to answer your question. This part should be a straightforward description of what you did in one or two sentences. It is usually written in the past simple tense, as it refers to completed actions.