An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

The Obesity Pandemic—Whose Responsibility? No Blame, No Shame, Not More of the Same

“ Imprisoned in every fat man, a thin man is wildly signaling to be let out” Cyril Connolly, rotund British writer, (1903–1974) Can we say this, let alone think it, in 2020?

Introduction

No one doubts the economic costs of obesity, estimated at 5–14% of health expenditure for 2020–2050 ( 1 ), but there is disagreement whether fatness is considered a disease ( 2 ) or a behavioral risk factor, similar to smoking, alcohol and substance abuse that may lead to a disease ( 3 ). Current opinion also emphasizes social determinants and equity, thereby moving away from personal responsibility concepts ( 4 ). Although recent competencies for medical training do recommend chronic disease models and personalized obesity management care plans ( 5 ), there is no mention of topics such as self-management, locus of control or responsibility . It is not clear whether this is because they are considered unimportant or because they are not politically correct—yet, they are critical components for chronic disease management such as diabetes, post-transplant care and obesity ( 6 ). The paradigm chosen has major implications for prevention and treatment strategies.

That the obesity pandemic continues unabated represents a catastrophic failure of government policy, public health, and medicine—but not only of these domains. Table 1 lists different levels of responsibility incorporating the sociotype ecological framework ( 6 ). Levels 1–4 represent context and systems; levels 5–7 society and interpersonal relationships; and levels 8–9 parental and intrapersonal health and psychological make-up. Personal editorial input from a leading obesity journal suggested that “at this point in time, … emphasis on the personal responsibility (rather than the biology), would only add to the stigmatization of obesity in general.” I disagree—and concerning the biology—see the beginning of the discussion section. Without considering aspects of responsibility, obesity management is severely compromised. There are at least two sides to personal responsibility: medicalizing obesity, which reduces it, and parental supervision, which emphasizes it, since fat children are at high risk for adult obesity ( 7 ). Finally, I suggest an integrated nine-level approach that eschews political correctness and hopefully is not more of the same.

The nine multilevel responsibilities and examples of strategies required for tackling obesity.

Why Medicalize Obesity Management?

Insurance regulations may be part of the reason to promote a medical rather than a personal choice paradigm. This has two consequences. First, medicalizing the diagnosis helps ensure continuing insurance coverage for the severely obese. Second, it guarantees long-term reimbursement for the treating physicians. Unfortunately, such medicalization externalizes locus of control ( 8 ), decreases incentives to change lifestyle behaviors and deters self-management necessary to take active responsibility for weight regulation, noting that intelligence has little to do with self-control.

Personal preferences determine what, and how much to eat and to exercise, and how important is body shape (aesthetics) to maintaining a healthy lifestyle. No healthy person chooses to go hungry or be malnourished, but there is an element of choice in becoming obese. These issues are closely linked to socio-economic status, culture, and education. Eating should be enjoyable and potentially controllable, but there are often mitigating factors such as the dependability and affordability of the food supply, peer group and advertising pressures. The price of fast food sometimes makes it irresistible. In the U.S., food security among the disadvantaged is cyclical and highest around the time people get their SNAP (Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program) food stamp dollars. Intake decreases or switches to higher calorie-per-dollar alternatives as the month progresses, when SNAP purchases run out ( 9 ). Such feast/famine cycles of food assistance may paradoxically contribute to unhealthy eating patterns.

Parental Responsibility for Childhood Obesity?

Parents naturally want to provide for the best growth and development of their children. Parental legal rights are generally overturned to protect a minor if harm is potentially permanent and avoidable (such as refusal of life-sustaining treatment on religious grounds) ( 10 ). Obviously, obesity is serious and can lead to lifelong morbidity. The gap between chronological and biological age widens as obesity increases. Car seats, seat belts, motorcycle helmets, vaccinations, and education are nearly all universally mandated and followed, especially when freely accessible; high-quality food is not. Upstream causes, such as inappropriate overfeeding, food to placate crying, high-calorie, low-nutrient so-called addictive foods, and lack of opportunities to exercise safely in school or in home neighborhoods, all challenge the avoidability criterion.

Holding parents answerable for their child's weight implies that they have the parenting skills (which, universally are not taught) to ensure optimal nutrition quality and quantity and lifestyle for their children. Infant nutrition begins at minus 9 months and breast-feeding protects against obesity. Healthy weight children perform 13% better at school ( 1 ). Throughout childhood, parents are usually well-intentioned and serve, by example, what they eat themselves. Parents have control until the age of about 10, for their children's nutritional choices, exercise and screen time but, by adolescence, the major influencers are peer groups and social media.

Integrated Action Strategies: Not More of the Same

In the final analysis, any change in body weight must follow the first law of thermodynamics. The fact that body fat mass is defended emphasizes, according to the fat cell hypothesis, the importance of early feeding practices, and parental responsibility. Obesity is caused by multifactorial bio-psycho-socio-behavioral influences; it may be inherited but it is not necessarily inevitable. Sometimes, the problem seems genetic because children adopt the eating habits and activity lifestyles of their parents. During evolution Homo sapiens has been programmed to store fat ( 11 ) and to be metabolically efficient. Metabolic efficiency actually increases as a result of weight loss and this is one of the main reasons why weight regain occurs after stopping a diet. Most of our biology as a species has evolved to survive periods of famines (with occasional feasts); but now it is ill equipped to resist the deleterious impact of a sustained surplus of food. Genes have not changed over the past 60 years ( pace epigenetic influences); so the toxic, obesogenic environment is the main culprit for the obesity pandemic. Genes cannot be manipulated from a realistic public health or ethical standpoint. Even if we could attack the biology, say with a drug, this also is not a viable solution. For how long should it be taken—for life? What would be the economic costs? Would the people most in need of it adhere to such treatment? What about the side-effects? Medical management (including bariatric surgery) only helps re-inforce externalizing the “locus of control” without which there can be no long-term chronic disease self-management.

Human history has shown through the sad examples of wars, pestilence and economic deprivations and disparities that obesity cannot occur if food is unavailable. Therefore, we have to attack predominantly the input side of the energy equation through interventions involving the nine levels of responsibility as shown in the Table. The action points listed are not exhaustive, and must be context and time-specific, multi-level and coordinated. They do show, however, the very many options available in tailoring prevention and intervention programs to a particular setting. Preventing obesity is primarily a public health behavior and literacy issue, empowering parental and personal choices. Only when there are health complications should the medical paradigm be appropriate. There are many factors involved, including: cultural issues (norms, values, attitudes) regarding diet (especially the Mediterranean diet) and body shape; lack of knowledge about breast feeding and infant nutrition; lack of physical and economic access to quality food, especially fruits and vegetables (“food deserts,” where neighborhoods lack nearby grocery stores); lack of kitchen facilities (or time) to cook; lack of potable water which leads to over-consumption of sweetened drinks; and lack of protected, well-lit exercise facilities.

To change the environment from obesogenic to leptogenic requires government and municipal policies targeting schools, workplaces, hospitals, and public places. Interventions should be age-appropriate and involve the social media with role models, influencers, sports people, pop stars, and advertising campaigns with the same types of compelling marketing strategies that are used to sell unhealthy, calorie-rich foods. Here, health and politically correct messages are often at odds. Slogans from body-positive activists such as “fat is beautiful” or “proud to be fat” should be replaced by “fat is unhealthy and dangerous.” Smokers do not glorify their habits, neither should the obese; but, no one should be body shamed. Should cultural and identity inappropriateness prevent a thin actor/singer from adding artificial girth to play Falstaff?–of course not. We need to keep a sense of humor and proportion. However, these pressures have become more complicated. When an advertisement or social media post of a well-toned body is portrayed, the ad agency or social media poster is vilified for promoting “unrealistic expectations.” Results from the recent ACTION study ( 12 ), reporting on over 3,000 people with obesity, showed that 82% considered that weight loss was completely their own responsibility while only 5% did not agree. In this paper, “stigma” only appeared once and only in the introduction. However, stigmatization is a worldwide phenomenon with cultural differences ( 13 ). These also apply to underdiagnosed causes of obesity such as binge eating disorders ( 14 ). Addressing and avoiding stigmatization, especially in the media and social networks, are major challenges in managing and dealing with patients with obesity.

Health professionals and society must not be judgmental in treating obesity as an individual moral failing or lack of self-discipline and will power. Instead, we have to recognize that patients with obesity are also products of a society of inequality, yet we must not let society “normalize” obesity and also, at the other extreme, “too thin” models. Mis-placed medical and political correctness that leads to hands-off management of obesity, means abrogation of the physician's responsibility: it should not stop recognizing the health problems and consequences and pressing for treatment. For example, some doctors are now even reluctant to raise the issue of obesity lest they be accused of fat shaming by not accepting their patients' proportions (despite the quote at the head of this opinion piece), and thereby receive poor approval ratings in an atmosphere where popularity is equated with good healthcare.

How much involvement should there be of public health authorities, school personnel or physicians? Should there be mandatory reporting of obesity and eating disorders as for child neglect/abuse or truancy? Much depends on how measurements are made and on what follow-up programs are in place. Lifestyle education and practice should continue throughout schooling, and lunchtimes may serve as educative experiences in manners and food habits, as practiced in Norway, Japan, and elsewhere.

Legislative interventions such as sin taxes and banning soft drink vending machines and junk food advertising to children are all relevant ( 15 ). Regressive taxation may be used to benefit the population for whom it is most oppressive. Such tax revenues may go to providing parks, playgrounds, and education programs for disadvantaged children, all of which improve health outcomes. The food industry, which is part of the problem [high-calorie, nutrient-poor, hyper-palatable products ( 16 )], must also be part of the solution by encouraging reformulations with healthier ingredients, comprehensible front-of-package food labeling and making price reductions for wholesome foods.

Suitable community-valid interventions can be based on Positive Deviant behaviors of the non-obese living in similar disadvantaged situations ( 17 ). There are also Positive Deviant countries such as Japan, Italy, and Switzerland where obesity rates are below 20%.

Obesity is one of the most difficult conditions to manage in healthcare. No-one has found the correct solution because there is no one solution. Comprehensive programs dealing with obesity require coordinated actions at all the nine levels of involvement—national, food system, educational, medical, public health, municipal, societal, parental, and individual. Parental and individual responsibility, choice and self-management clearly have a place near the center of the stage in the obesity tragedy. Otherwise, it is like going to see the play Hamlet and the Prince fails to make an appearance. Individuals are indeed responsible for their health-promoting behaviors but should be held accountable only when they have adequate resources to do so ( 18 ). In conclusion, no one is to be blamed, but everyone has a collective responsibility for working to combat the obesity pandemic—business as usual is no longer an option.

Author Contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

Conflict of Interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

I thank Professor Janet Fleetwood for very constructive discussions in preparing this opinion piece.

Obesity in America: A Public Health Crisis

Obesity is a public health issue that impacts more than 100 million adults and children in the U.S.

What You Need to Know About Obesity

Getty Images

Obesity has become a public health crisis in the United States. The medical condition, which involves having an excessive amount of body fat, is linked to severe chronic diseases including type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, high blood pressure and cancer. It causes about 1 in 5 deaths in the U.S. each year – nearly as many as smoking, according to a study published in the American Journal of Public Health.

The financial cost of obesity is high as well. According to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention , "The estimated annual medical cost of obesity in the United States was $147 billion in 2008 U.S. dollars; the medical cost for people who have obesity was $1,429 higher than those of normal weight."

While researchers say the obesity epidemic began in the U.S. in the 1980s, there has been a sharp increase in obesity rates in the U.S. over the last decade. Nearly 40% of all adults over the age of 20 in the U.S. – about 93.3 million people – are currently obese, according to data published in JAMA in 2018. Every state in the U.S. has more than 20% of adults with obesity, according to the CDC – a significant uptick since 1985, when no state had an obesity rate higher than 15%. Certain states have higher rates than others: there are more obese people living in the South (32.4%) and Midwest (32.3%) than in other parts of the country.

Sugar Taxes and Other Efforts to Reduce Obesity

Federal, state and local governments have moved to address obesity in several ways. On the federal level, several programs – such as the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), Women, Infants and Children (WIC) Program, Child and Adult Care Food Program (CACFP) and the Healthy Food FInancing Initiative – as well as the U.S. Departments of Agriculture and Health and Human Services work to make healthier foods affordable and available in underserved communities. To prevent childhood obesity in particular, there are also school and early childhood policies, such as Head Start – a comprehensive early childhood education program – school-based physical education and Safe Routes to School, which promotes walking and biking to and from school and increasing healthy eating and physical activity while reducing the risk of obesity.

In March, the American Academy of Pediatrics and the American Heart Association offered several public policy recommendations , including raising the price of sugary drinks, encouraging federal and state governments to limit the marketing of sugary drinks to kids and teenagers, having vending machines offer water, milk and other healthy beverages, improving nutritional information on labels, restaurant menus and advertisements, and supporting hospitals in establishing policies to discourage the purchase of sugary drinks in their facilities.

Meanwhile, states have implemented laws, largely through early childhood education settings, to improve access to healthy food and increase physical activity in order to promote a healthy weight. These policies stretch from breastfeeding, providing available drinking water and daily physical activity to limited screen time as well as meals and snacks that meet healthy eating standards set by the USDA or CACFP.

City governments have considered, and in some cases implemented, so-called "sin taxes" that aim to make potentially unhealthy food choices less attractive and accessible. Cities including Philadelphia, Boulder, Colorado, and Berkeley, California, levy a tax on sugar-sweetened beverages; The American Public Health Association noted in 2016 that the tax led to a 21% drop in the consumption of sugary drinks in Berkeley alone. (A proposal to expand it to all of California stalled this year .) In Philadelphia , the price of sugary beverages sold in supermarkets, mass merchandisers and pharmacies rose – and sales fell – after the city implemented a tax on those products, but a study found that sales in towns bordering Philadelphia increased.

Some researchers say there's little proof that taxing food or drink choices really changes behavior. In spite of taxes and warnings about the health effects of drinking sugary beverages, eight of every 10 American households buys sodas and other sugary drinks each week, adding up to 2,000 calories per household per week, new research shows .

"Large authoritative systematic reviews of the peer-reviewed scientific literature have failed to illustrate any compelling evidence that economic interventions are effective in promoting any type of dietary behavior change," says Taylor Wallace , principal and CEO of the Think Healthy Group and an adjunct professor in the department of nutrition and food studies at George Mason University.

But others contend that making it more expensive to buy sugary drinks is a step in the right direction.

"We need to ensure that people understand the threat of these products to their health, so they want to reduce their consumption," says Sandra Mullin, senior vice president of policy, advocacy and communication for Vital Strategies, an organization that works to implement health initiatives, and a former public health official in New York City "And [hiking] the price is a prompt for them to do that."

Learn more about obesity:

What is obesity?

Obesity is a chronic disease . It occurs when an excessive amount of body fat affects a person's overall health.

How is obesity diagnosed?

According to the Obesity Action Coalition , a healthcare provider may diagnose a patient with obesity if his or her body mass index, or BMI, is 30 or greater. BMI is a value derived from the weight and height of a person; normal BMI ranges from 20 to 25. There is no lab test, blood screening or other diagnostic used to diagnose obesity.

What is morbid obesity?

Morbid obesity is diagnosed when a person has a BMI of 40 or greater. People can also be diagnosed with morbid obesity if their BMI is 35 if they are also experiencing health complications like high blood pressure or diabetes.

How is being overweight different from being obese?

Obesity has to do with having too much body fat and a Body Mass Index, or BMI, of 30 or more. Being overweight can involve having too much body fat, the Department of Health and Human Services says , but having extra muscle, bone or water can also be a factor.

What causes obesity?

Obesity occurs when a person takes in more calories than he or she burns through normal daily activities and exercise, according to the Mayo Clinic . It is not simply a matter of over-indulgence or a lack of self control, obesity researcher Dr. George Bray said at the first annual U.S. News Combating Childhood Obesity summit , held at Texas Children's Hospital in May.

"Obesity isn't a disease of willpower – it's a biological problem," he said . "Genes load the gun, and environment pulls the trigger."

Certain scientific and societal factors – including genetics, the increased consumption of processed foods and sugar-sweetened beverages, and some medications and medical conditions – can increase a person's risk of becoming obese. Age and pregnancy can also trigger weight gain.

The 10 Fattest States in the U.S.

Diet has an important connection to obesity. Studies show the amount of soybean oil Americans consume spiked in the 1960s and 1970s, most likely as highly processed foods became popular, and American adults and children started to weight more around that time, Bray said.

"The fats in our food supply may well be playing a part in our inability to regulate" food intake, Bray said at the obesity summit . Consumption of sugary soft drinks also skyrocketed between 1950 and 2000, he pointed out, as Americans tripled the amount of sweet beverages they drank each year.

Artificial sweeteners have also been linked to obesity . A study presented at the 2018 Experimental Biology meeting suggests artificial sweeteners alter how bodies process fat and obtain energy.

"Despite the addition of these non-caloric artificial sweeteners to our everyday diets, there has still been a drastic rise in obesity and diabetes," one of the study's authors, Brian Hoffmann, assistant professor in the department of biomedical engineering at the Medical College of Wisconsin and Marquette University , said. "In our studies, both sugar and artificial sweeteners seem to exhibit negative effects linked to obesity and diabetes, albeit through very different mechanisms from each other."

What are some of the risk factors for obesity?

Genetic factors include: the amount of body fat a person stores, where it's distributed and how efficiently his or her body metabolizes food into energy.

Medical conditions include: Prader-Willi syndrome, Cushing's syndrome, arthritis and other diseases that can lead to decreased activity. Certain medications – some antidepressants, anti-seizure, diabetes, antipsychotic medications, steroids and beta blockers – can also cause weight gain.

Lifestyle and behavioral factors include: a lack of physical activity that burns calories, smoking, lack of sleep (which can lead to an increased desire to consume calories), eating an unhealthy diet.

Social and economic factors include: not having a safe space to exercise, not having enough money to afford healthier foods, food deserts where grocery stores that carry fresh fruits and vegetables are not available, lack of transportation to access healthy food options.

Can children be obese?

Obesity can be diagnosed at any age. The prevalence of obesity among children and adolescents between ages 2 and 19 was estimated to be 18.5% – more than one in six – between 2015 and 2016, with 13.7 million impacted, according to the CDC's National Center for Health Statistics .

Children who are obese are at risk for developing premature heart disease , the American Heart Association reports. A study of nearly 2.3 million people monitored over the course of 40 years found that the risk of dying from heart disease was two to three times higher if they had been overweight or obese as teens.

Obesity is a problem in other countries as well. A study published in the Lancet in 2017 found that the number of obese 5 to 19 year olds worldwide increased from 11 million in 1975 and to 124 million in 2016. The researchers projected the number of children and adolescents who are obese will surpass those that are moderately or severly underweight by 2022.

How many adult men and women are obese?

U.S. adult obesity prevalence between 2015 and 2016 was nearly 40% – about 93.3 million people, according to the CDC . The highest rate (42.8%) was among adults between the ages of 40 and 59; the prevalence among adults age 20 to 39 years was 35.7%, and 41% among adults age 60 and older. There was no significant difference between men and women overall or by age group, according to the data brief.

What preventable diseases and health issues are associated with obesity?

Mental and physical health problems involving obesity include:

- Type 2 diabetes

- High blood pressure

- Heart disease

- Gallbladder disease

- Cancers (including breast, liver, pancreas, endometrial, colorectal, prostate and kidney)

- High cholesterol

- Osteoarthritis of weight-bearing joints

- Sleep apnea

- Respiratory problems

- Gastroesophageal reflux disease

- Urinary stress incontinence

- Infertility

- Sexual dysfunction

- Physical disability

- Lower work achievement

- Social isolation

What are the financial costs of obesity in the U.S.?

Researchers from the University of Cincinnati in 2008 estimated the cost of medical care to diagnose and treat obesity and its associated health issues to be about $147 billion annually.

The CDC estimates the indirect costs of obesity-related health issues – including absenteeism, premature disability, declines in productiving and earlier mortality – to range from $3 billion and $6.4 billion annually.

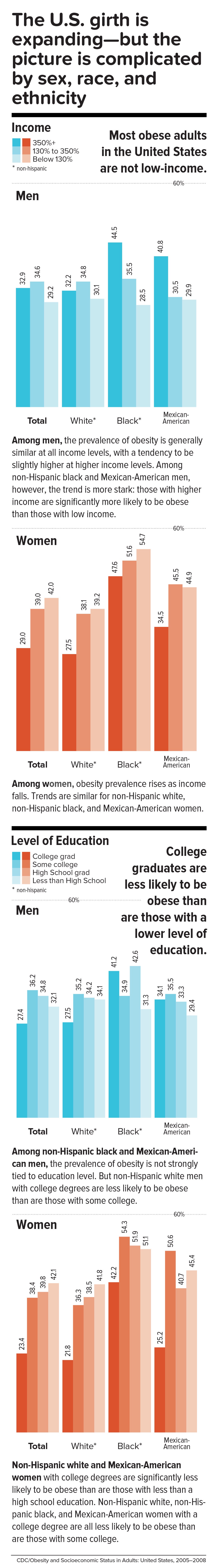

Are certain races more likely to become obese than others?

At 25.8%, Hispanic children and adolescents between the ages of 2 and 19 had the highest prevalence of obesity between 2015 and 2016, according to the National Center for Health Statistics . Meanwhile, obesity prevalence was about 22% among black youths; 14.1% among non-Hispanic whites; and 11% among non-Hispanic Asians. While the report notes that there were no significant differences in the prevalence of obesity between boys and girls by race and Hispanic origin, Hispanic boys in particular had a higher prevalence of obesity than non-Hispanic black boys.

Similarly, non-hispanic black (46.8%) and Hispanic (47%) adults in the U.S. have higher obesity rates than non-Hispanic white (37.9%) and non-Hispanic Asian (12.7%) adults, according to the NCHS. Rates of obesity were especially high among black and Hispanic women, according to the report, surpassing 50%.

How is obesity treated?

Treatment of obesity primarily involves changing a patient's behavior, but surgery to reduce the size of a patient's stomach or alter the digestive tract and medication may also be options for those who have trouble losing weight on their own.

The National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases says common treatments include eating more healthy foods, incorporating more physical activity and changing other habits , such as taking the stairs instead of the elevator. Developing a healthy eating plan with fewer calories, setting realistic and measurable goals, participating in formal weight-management programs and seeking help from family, friends, health professionals and support groups can make it easier to develop healthier habits, though the federal agency warns that setbacks occur and people should be prepared.

Experts say obese patients who lose 5% to 10% of their body weight – about 10 to 20 pounds for a 200-lb person with a BMI indicating obesity, for example – can reduce his or her risk of obesity-related health problems like type 2 diabetes as well as lower blood pressure and cholesterol levels.

Can obesity be prevented?

When it comes to suggestions about how to prevent obesity, common principles stand out across local, state and federal guidelines :

- increase physical activity

- improve nutrition through increased consumption of fruits and vegetables

- encourage breastfeeding

- encourage mobility between work, school and communities.

Some researchers also say that the food industry has a role to play in solving the obesity crisis: Making highly processed and fast food much more expensive could curb consumption and lower the obesity rate in the U.S. over time.

"My former brethren in the soft drink business really fought the issue of obesity early on rather than stepping up and saying, 'OK, we don't wish to be blamed totally for this issue but we still can do something,'" Hank Cardello, a former food company executive who now works as a food policy analyst at the Hudson Institute, a Washington, D.C. think tank, said during the U.S. News Combating Childhood Obesity summit in May. "Larger portions, the whole supersize phenomenon – it's actually proven that that made more money for them" while helping trigger the national obesity epidemic, he explained.

What are the most-obese states in America?

According to the CDC, as of 2017 (the most-recent data available) the most-obese states in America are:

- West Virginia (38.1% of adults)

- Mississippi (37.3%)

- Oklahoma (36.5%)

- Iowa (36.4%)

- Alabama (36.2%)

- Louisiana (36.2%)

- Arkansas (35%)

- Kentucky (34.3%)

- Alaska (34.2%)

- South Carolina (34.1%)

What are the least-obese states in America?

These states have the lowest obesity rates in the U.S., according to the CDC:

- Colorado (22.6% of adults)

- Hawaii (23.8%)

- California (25.1%)

- Utah (25.25%)

- Montana (25.27%)

- New York (25.7%)

- Massachuestts (25.9%)

- Nevada (26.7%)

- Connecticut (26.9%)

- New Jersey (27.3%)

Is obesity a problem in other countries?

The World Health Organization estimates 39% of women and 39% of men ages 18 and older are overweight, with the highest prevalence of obesity on the island of Nauru, at 61%. (The U.S. ranked 12th worldwide, at 36.2%).

Among the 20 most-populous countries worldwide, the United States had the highest level of age-standardized childhood obesity, at 12.7%, while China and India had the highest numbers of obese children in 2015, according to a 2017 University of Washington study . Further, the United States and China had the highest number of obese adults, the study found. That same year, the researchers determined excess body weight to be associated with about 4 million deaths and 120 million disability-adjusted life-years lost.

Rates of adult obesity among the 36 countries in the Organization for Economic Cooperation were highest in the U.S., Mexico, New Zealand and Hungary. They were lowest in Japan and South Korea in 2017, according to an OECD "Obesity Update" report .

Tags: obesity , weight loss , public health

Recommended Articles

National News

Healthiest Communities Health News

Best Countries

Healthiest Communities

- # 1 Los Alamos County, NM

- # 2 Falls Church city, VA

- # 3 Douglas County, CO

- # 4 Morgan County, UT

- # 5 Carver County, MN

You May Also Like

The un says a quarter of the world's children under 5 have severe food poverty. many are in africa.

Associated Press June 6, 2024

EV Sales Boom in Nepal, Helping to Save on Oil Imports, Alleviate Smog

Man in Mexico Died of a Bird Flu Strain That Hadn't Been Confirmed Before in a Human, WHO Says

Associated Press June 5, 2024

FDA Advisers Urge Targeting JN.1 Strain in Recipe for Fall's COVID Vaccines

The Next COVID Vaccine Is Coming

Cecelia Smith-Schoenwalder June 5, 2024

Prevention, prevention, prevention.

Losing weight is hard to do.

In the U.S., only one in six adults who have dropped excess pounds actually keep off at least 10 percent of their original body weight. The reason: a mismatch between biology and environment. Our bodies are evolutionarily programmed to put on fat to ride out famine and preserve the excess by slowing metabolism and, more important, provoking hunger. People who have slimmed down and then regain their weight don’t lack willpower—their bodies are fighting them every inch of the way.

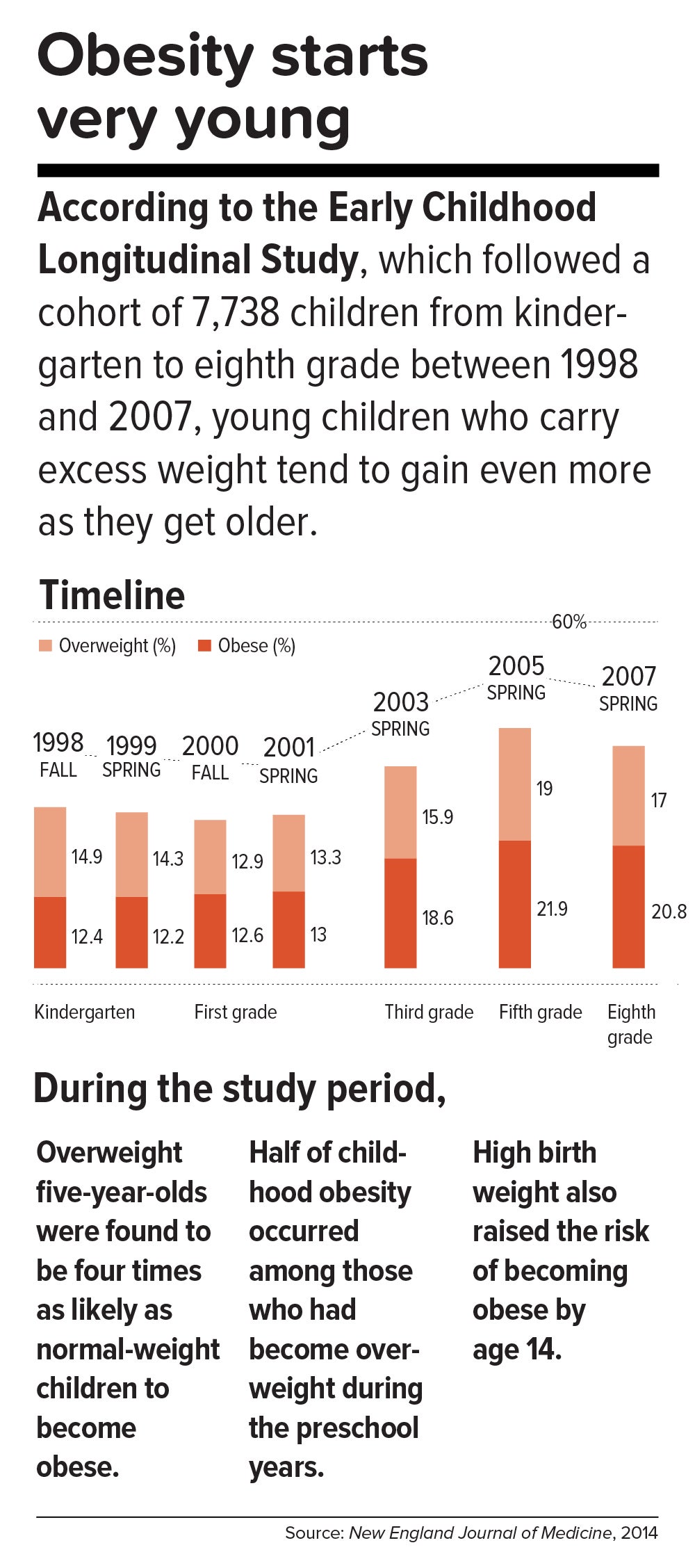

This inborn predisposition to hold on to added weight reverberates down the life course. Few children are born obese, but once they become heavy, they are usually destined to be heavy adolescents and heavy adults. According to a 2016 study in the New England Journal of Medicine , approximately 90 percent of children with severe obesity will become obese adults with a BMI of 35 or higher. Heavy young adults are generally heavy in middle and old age. Obesity also jumps across generations; having a mother who is obese is one of the strongest predictors of obesity in children.

All of which means that preventing child obesity is key to stopping the epidemic. By the time weight piles up in adulthood, it is usually too late. Luckily, preventing obesity in children is easier than in adults, partly because the excess calories they absorb are minimal and can be adjusted by small changes in diet—substituting water, for example, for sugary fruit juices or soda.

Still, the bulk of the obesity problem—literally—is in adults. According to Frank Hu, chair of the Harvard Chan Department of Nutrition, “Most people gain weight during young and middle adulthood. The weight-gain trajectory is less than 1 pound per year, but it creeps up steadily from age 18 to age 55. During this time, people gain fat mass, not muscle mass. When they reach age 55 or so, they begin to lose their existing muscle mass and gain even more fat mass. That’s when all the metabolic problems appear: insulin resistance, high cholesterol, high blood pressure.”

Adds Walter Willett, Frederick John Stare Professor of Epidemiology and Nutrition at Harvard Chan, “The first 5 pounds of weight gain at age 25—that’s the time to be taking action. Because someone is on a trajectory to end up being 30 pounds overweight by the time they’re age 50.”

The most realistic near-term public health goal, therefore, is not to reverse but rather to slow down the trend—and even this will require strong commitment from government at many levels. In May 2017, the Trump administration rolled back recently-enacted standards for school meals, delaying a rule to lower sodium and allowing waivers for regulations requiring cafeterias to serve foods rich in whole grains. If recent expansions in food entitlements and school meals are undermined, “It would be a ‘disaster,’ to use the president’s word,” says Marlene Schwartz, director of the Rudd Center for Obesity & Food Policy at the University of Connecticut. “The federal food programs are incredibly important, not just because of the food and money they provide families, but because supporting better nutrition in child care, schools, and the WIC [Women, Infants, and Children] program has created new social norms. We absolutely cannot undo the progress that we’ve made in helping this generation transition to a healthier diet.”

Get the science right.

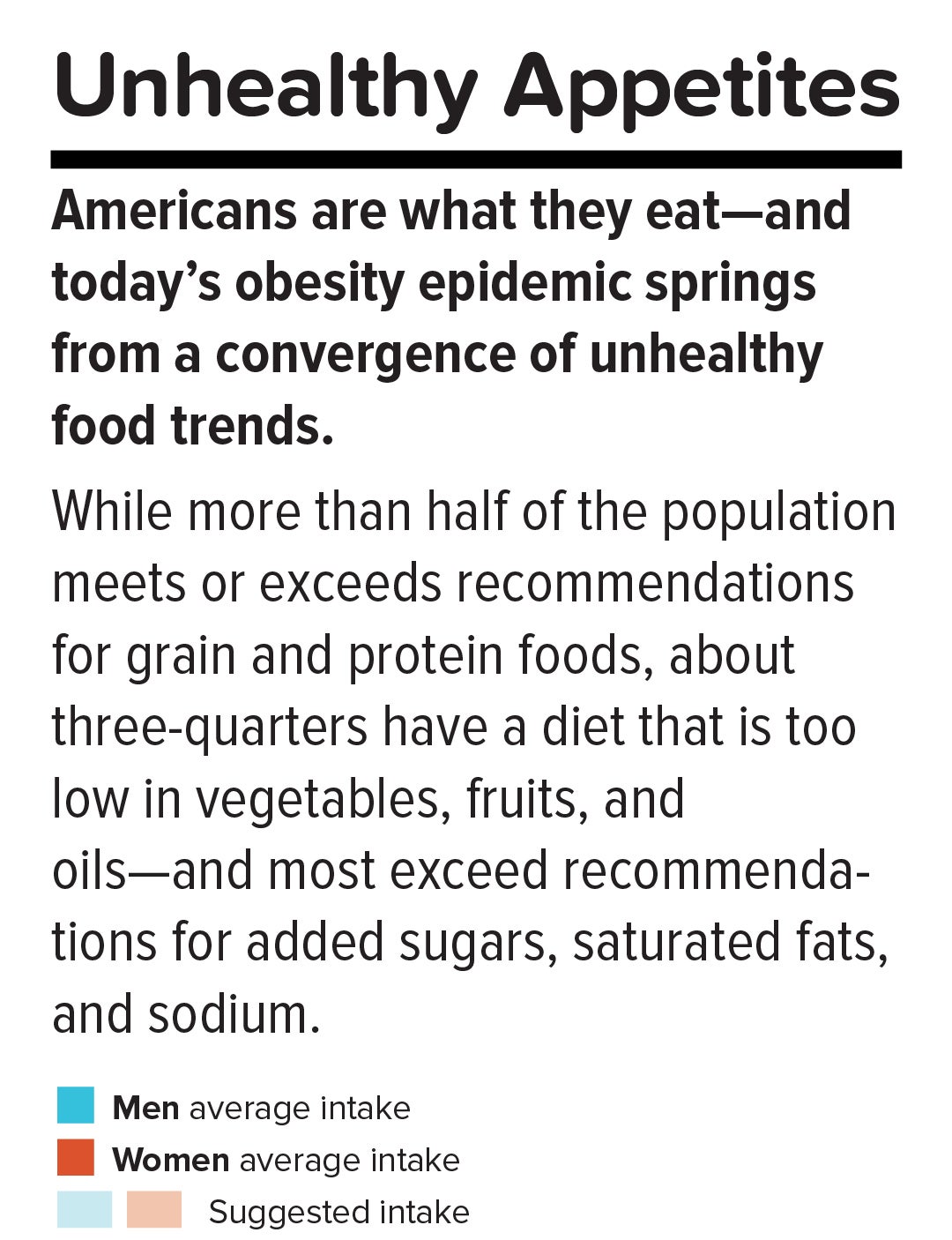

It is impossible to prescribe solutions to obesity without reminding ourselves that nutrition scientists botched things decades ago and probably sent the epidemic into overdrive. Beginning in the 1970s, the U.S. government and major professional groups recommended for the first time that people eat a low-fat/high-carbohydrate diet. The advice was codified in 1977 with the first edition of The Dietary Goals for the United States , which aimed to cut diet-related conditions such as heart disease and diabetes. What ensued amounted to arguably the biggest public health experiment in U.S. history, and it backfired.

At the time, saturated fat and dietary cholesterol were believed to be the main factors responsible for cardiovascular disease—an oversimplified theory that ignored the fact that not all fats are created equal. Soon, the public health blitz against saturated fat became a war on all fat. In the American diet, fat calories plummeted and carb calories shot up.

“We can’t blame industry for this. It was a bandwagon effect in the scientific community, despite the lack of evidence—even with evidence to the contrary,” says Willett. “Farmers have known for thousands of years that if you put animals in a pen, don’t let them run around, and load them up with grains, they get fat. That’s basically what has been happening to people: We created the great American feedlot. And we added in sugar, coloring, and seductive promotion for low-fat junk food.”

Scientists now know that whole fruits and vegetables (other than potatoes), whole grains, high-quality proteins (such as from fish, chicken, beans, and nuts), and healthy plant oils (such as olive, peanut, or canola oil) are the foundations of a healthy diet.

But there is also a lot scientists don’t yet know. One unanswered question is why some people with obesity are spared the medical complications of excess weight. Another concerns the major mechanisms by which obesity ushers in disease. Although surplus body weight can itself directly cause problems—such as arthritis due to added load on joints, or breast cancer caused by hormones secreted by fat cells—in general, obesity triggers myriad biological processes. Many of the resulting conditions—such as atherosclerosis, diabetes, and even Alzheimer’s disease—are mediated by inflammation, in which the body’s immune response becomes damagingly self-perpetuating. In this sense, today’s food system is as inflammagenic as it is obesigenic.

Scientists also need to ferret out the nuanced effects of particular foods. For example, do fermented products—such as yogurt, tempeh, or sauerkraut—have beneficial properties? Some studies have found that yogurt protects against weight gain and diabetes, and suggest that healthy live bacteria (known as probiotics) may play a role. Other reports point to fruits being more protective than vegetables in weight control and diabetes prevention, although the types of fruits and vegetables make a difference.

A 2017 article in the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition showed that substituting whole grains for refined grains led to a loss of nearly 100 calories a day—by speeding up metabolism, cutting the number of calories that the body hangs on to, and, more surprisingly, by changing the digestibility of other foods on the plate. That extra energy lost daily—by substituting, say, brown rice for white rice or barley for pita bread—was equivalent to a brisk 30-minute walk. One hundred calories a day, sustained over years, and multiplied by the population is one mathematical equivalent of the obesity epidemic.

A companion study found that adults who ate a whole-grain-rich diet developed healthier gut bacteria and improved immune responses. That particular foods alter the gut microbiome—the dense and vital community of bacteria and other microorganisms that work symbiotically with the body’s own digestive system—is another critical insight. The microbiome helps determine weight by controlling how our bodies extract calories and store fat in the liver, and the microbiomes of obese individuals are startlingly efficient at harvesting calories from food. [To learn more about Harvard Chan research on the gut microbiome, read “ Bugs in the System .”] The hormonal effects of sleep deprivation and stress—two epidemics concurrent and intertwined with the obesity trend—are other promising avenues of research.

And then there are the mystery factors. One recent hypothesis is that an agent known as adenovirus 36 partly accounts for our collective heft. A 2010 article in The Royal Society described a study in which researchers examined samples of more than 20,000 animals from eight species living with or around humans in industrialized nations, a menagerie that included macaques, chimpanzees, vervets, marmosets, lab mice and rats, feral rats, and domestic dogs and cats. Like their Homo sapiens counterparts, all of the study populations had gained weight over the past several decades—wild, domestic, and lab animals alike. The chance that this is a coincidence is, according to the scientists’ estimate, 1 in 10 million. The stumped authors surmise that viruses, gene expression changes, or “as-of-yet unidentified and/or poorly understood factors” are to blame.

Master the art of persuasion.

A 2015 paper in the American Journal of Public Health revealed the philosophical chasm that hampers America’s progress on obesity prevention. It found that 72 to 98 percent of obesity-related media reports emphasize personal responsibility for weight, compared with 40 percent of scientific papers.

A recent study by Drexel University researchers also quantified the political polarization around public health measures. From 1998 through 2013, Democrats voted in line with recommendations from the American Public Health Association 88.3 percent of the time, on average, while Republicans voted for the proposals just 21.3 percent of the time.

Clearly, we can’t count on bipartisan goodwill to stem the obesity crisis. But we can ask what kinds of messages appeal to politically divergent audiences. A stealth strategy may be to avoid even uttering the word “obesity.” On January 1 of this year, Philadelphia’s 1.5-cents-per-ounce excise tax on sugar-sweetened and diet beverages took effect. When Philadelphia Mayor Jim Kenney lobbied voters to approve the tax, his bid centered not on improving health—the unsuccessful pitch of his predecessor—but on raising $91 million annually for prekindergarten programs.

“That’s something lots of people care about and can get behind—it’s a feel-good policy, and it makes sense,” says psychologist Christina Roberto, assistant professor of medical ethics and health policy at the University of Pennsylvania, and a former assistant professor of social and behavioral sciences and nutrition at Harvard Chan. The provision for taxing diet beverages was also shrewd, she adds, because it spread the tax’s pain; since wealthier people are more likely than less-affluent individuals to buy diet drinks, the tax could not be slapped with the label “regressive.”

But Roberto sees a larger lesson in the Philadelphia story. Public health messaging that appeals to values that transcend the individual is less fraught, less stigmatizing, and perhaps more effective. As she puts it, “It’s very different to hear the message, ‘Eat less red meat, help the planet’ versus ‘Eat less red meat, help yourself avoid saturated fat and cardiovascular disease.’”

Supermarket makeovers

Supermarket aisles are other places where public health can shuffle a deck stacked against healthy consumer choices.

With slim profit margins and 50,000-plus products on their shelves, grocery stores depend heavily on food manufacturers’ promotional incentives to make their bottom lines. “Manufacturers pay slotting fees to get their products on the shelf, and they pay promotion allowances: We’ll give you this much off a carton of Coke if you put it on sale for a certain price or if you put it on an end-of-aisle display,” says José Alvarez, former president and chief executive officer of Stop & Shop/Giant-Landover, now senior lecturer of business administration at Harvard Business School. Such promotional payments, Alvarez adds, often exceed retailers’ net profits.

Healthy new products—like flash-frozen dinners prepared with heaps of vegetables and whole grains, and relatively little salt—can’t compete for prized shelf space against boxed mac and cheese or cloying breakfast cereals. One solution, says Alvarez, is for established consumer packaged goods companies to buy out what he calls the “hippie in the basement” firms that have whipped up more nutritious items. The behemoths could apply their production, marketing, and distribution prowess to the new offerings—and indeed, this has started to happen over the last five years.

Another approach is to make nutritious foods more convenient to eat. “We have all of these cooking shows and upscale food magazines, but most people don’t have the time or inclination—or the skills, quite frankly—to cook,” says Alvarez. “Instead, we should focus on creating high-quality, healthy, affordable prepared foods.”

An additional model is suggested by Jeff Dunn, a 20-year veteran of the soft drink industry and former president of Coca-Cola North America, who went on to become an advocate for fresh, healthy food. Dunn served as president and chief executive officer of Bolthouse Farms from 2008 to 2015, where he dramatically increased sales of baby carrots by using marketing techniques common in the junk food business. “We operated on the principles of the three 3 A’s: accessibility, availability, and affordability,” says Dunn. “That, by the way, is Coke’s more-than-70-year-old formula for success.”

Show them the money.

Obesity kills budgets. According to the Campaign to End Obesity, a collaboration of leaders from industry, academia, public health, and policymakers, annual U.S. health costs related to obesity approach $200 billion. In 2010, the nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office reported that nearly 20 percent of the rise in health care spending from 1987 to 2007 was linked to obesity. And the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) found that full-time workers in the U.S. who are overweight or obese and have other chronic health conditions miss an estimated 450 million more days of work each year than do healthy employees—upward of $153 billion in lost productivity annually.

But making the money case for obesity prevention isn’t straightforward. For interventions targeting children and youth, only a small fraction of savings is captured in the first decade, since most serious health complications don’t emerge for many years. Long-term obesity prevention, in other words, doesn’t fit into political timetables for elected officials.

Yet lawmakers are keen to know how “best for the money” obesity-prevention programs can help them in the short run. Over the past two years, Harvard Chan’s Steve Gortmaker and his colleagues have been working with state health departments in Alaska, Mississippi, New Hampshire, Oklahoma, Washington, and West Virginia and with the city of Philadelphia and other locales, building cost-effectiveness models using local data for a wide variety of interventions—from improved early child care to healthy school environments to communitywide campaigns. “We collaborate with health departments and community stakeholders, provide them with the evidence base, help assess how much different options cost, model the results over a decade, and they pick what they want to work on. One constant that we’ve seen—and these are very different political environments—is a strong interest in cost-effectiveness,” he says.

In a 2015 study in Health Affairs , Gortmaker and colleagues outlined three interventions that would more than pay for themselves: an excise tax on sugar-sweetened beverages implemented at the state level; elimination of the tax subsidy for advertising unhealthy food to children; and strong nutrition standards for food and drinks sold in schools outside of school meals. Implemented nationally, these interventions would prevent 576,000, 129,100, and 345,000 cases of childhood obesity, respectively, by 2025. The projected net savings to society in obesity-related health care costs for each dollar invested: $31, $33, and $4.60, respectively.

Gortmaker is one of the leaders of a collaborative modeling effort known as CHOICES—for Childhood Obesity Intervention Cost-Effectiveness Study—an acronym that seems a pointed rebuttal to the reflexive conservative argument that government regulation tramples individual choice. Having grown up not far from Des Plaines, Illinois, site of the first McDonald’s franchise in the country, he emphasizes to policymakers that at this late date, America cannot treat its way out of obesity, given current medical know-how. Only a thoroughgoing investment in prevention will turn the tide. “Clinical interventions produce too small an effect, with too small a population, and at high cost,” Gortmaker says. “The good news is that there are many cost-effective options to choose from.”

While Gortmaker underscores the importance of improving both food choices and options for physical activity, he has shown that upgrading the food environment offers much more benefit for the buck. This is in line with the gathering scientific consensus that what we eat plays a greater role in obesity than does sedentary lifestyle (although exercise protects against many of the metabolic consequences of excess weight). “The easiest way to explain it,” Gortmaker says, “is to talk about a sugary beverage—140 calories. You could quickly change a kid’s risk of excess energy balance by 140 calories a day just by switching from a sugary drink a day to water or sparkling water. But for a 10-year-old boy to burn an extra 140 calories, he’d have to replace an hour-and-a-half of sitting with an hour-and-a-half of walking.”

Small tweaks in adults’ diets can likewise make a big difference in short order. “With adults, health care costs rise rapidly with excess weight gain,” Gortmaker says. “If you can slow the onset of obesity, you slow the onset of diabetes, and potentially not only save health care costs but also boost people’s productivity in the workforce.”

One of Gortmaker’s most intriguing calculations spins off of the food industry’s estimated $633 million spent on television marketing aimed at kids. Currently, federal tax treatment of advertising as an ordinary business expense means that the government, in effect, subsidizes hawking of junk food to children. Gortmaker modeled a national intervention that would eliminate this subsidy of TV ads for nutritionally empty foods and beverages aimed at 2- to 19-year-olds. Drawing on well-delineated relationships between exposure to these advertisements and subsequent weight gain, he found that the intervention would save $260 million in downstream health care costs. Although the effect would probably be small at the individual level, it would be significant at the population level.

Level the playing field through taxes and regulation.

When public health took on cigarette smoking, starting in the 1960s, it did so with robust policies banning television ads and other marketing, raising taxes to increase prices, making public places smoke-free, and offering people treatment such as the nicotine patch. In 1965, the smoking rate for U.S. adults was 42.2 percent; today, it is 16.8 percent.

Similarly, America reduced the rate of deaths caused by motor vehicle accidents—a 90 percent decrease over the 20th century, according to the CDC—with mandatory seat belt laws, safer car designs, stop signs, speed limits, rumble strips, and the stigmatization of drunk driving.

Change the product. Change the environment. Change the culture. That is also the policy recipe for stopping obesity.

Laws that make healthy behaviors easier are often followed by positive changes in those behaviors. And people who are trying to adopt healthy behaviors tend to support policies that make their personal aspirations achievable, which in turn nudges lawmakers to back the proposals.

One debate today revolves around whether recipients of federal Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) benefits (formerly known as food stamps) should be restricted from buying sodas or junk food. The largest component of the USDA budget, SNAP feeds one in seven Americans. A USDA report, issued last November, found that the number-one purchase by SNAP households was sweetened beverages, a category that included soft drinks, fruit juices, energy drinks, and sweetened teas, accounting for nearly 10 percent of SNAP money spent on food. Is the USDA therefore underwriting the soda industry and planting the seeds for chronic disease that the government will pay to treat years down the line?

Eric Rimm, a professor in the Departments of Epidemiology and Nutrition at the Harvard Chan School, frames the issue differently. In a 2017 study in the American Journal of Preventive Medicine , he and his colleagues asked SNAP participants whether they would prefer the standard benefits package or a “SNAP-plus” that prohibited the purchase of sugary beverages but offered 50 percent more money for buying fruits and vegetables. Sixty-eight percent of the participants chose the healthy SNAP-plus option.

“A lot of work around SNAP policy is done by academics and politicians, without reaching out to the beneficiaries,” says Rimm. “We haven’t asked participants, ‘What’s your say in this? How can we make this program better for you?’” To be sure, SNAP is riddled with nutritional contradictions. Under current rules, for example, participants can use benefits to buy a 12-pack of Pepsi or a Snickers bar or a giant bag of Lay’s potato chips but not real food that happens to be heated, such as a package of rotisserie chicken. “This is the most vulnerable population in the country,” says Rimm. “We’re not listening well enough to our constituency.”

Other innovative fiscal levers to alter behavior could also drive down obesity. In 2014, a trio of strong voices on food industry practices—Dariush Mozaffarian, DrPH ’06, dean of Tufts University’s Friedman School of Nutrition Science and Policy and former associate professor of epidemiology at the Harvard Chan School; Kenneth Rogoff, professor of economics at Harvard; and David Ludwig, professor in the Department of Nutrition at Harvard Chan and a physician at Boston Children’s Hospital—broached the idea of a “meaningful” tax on nearly all packaged retail foods and many chain restaurants, with the proceeds used to pay for minimally processed foods and healthier meals for school kids. In essence, the tax externalizes the social costs of harmful individual behavior.

“We made a straightforward proposal to tax all processed foods and then use the income to subsidize whole foods in a short-term, revenue-neutral way,” explains Ludwig. “The power of this idea is that, since there is so much processed food consumption, even a modest tax—in the 10 to 15 percent range—is not going to greatly inflate the cost of these foods. Their price would increase moderately, but the proceeds would not disappear into government coffers. Instead, the revenue would make healthy foods affordable for virtually the entire population, and the benefits would be immediately evident. Yes, people will pay moderately more for their Coke or for their cinnamon bear claw but a lot less for nourishing, whole foods.”

Another suggestion comes from Sandro Galea, dean of the Boston University School of Public Health, and Abdulrahman M. El-Sayed, a public health physician and epidemiologist. In a 2015 issue of the American Journal of Public Health , they called for “calorie offsets,” similar to the carbon offsets used to mitigate environmental harm caused by the gas and oil industries. A “calorie offset” scheme could hand the food and beverage industries a chance at redemption by inviting them to invest in such undertakings as city farms, cooking classes for parents, healthy school cafeterias, and urban green spaces.

These ambitious proposals face almost impossibly high hurdles. Political battle lines typically pit public health against corporations, with Big Food casting doubt on solid nutrition science, deeming government regulation a threat to free choice, and making self-policing pledges that it has never kept. On the website for the Americans for Food and Beverage Choice, a group spearheaded by the American Beverage Association, is the admonition: “[W]hether it’s at a restaurant or in a grocery store, it’s never the government’s job to decide what you choose to eat and drink.”

Yet surprisingly, many public health professionals are convinced that the only way to stop obesity is to make common cause with the food industry. “This isn’t like tobacco, where it’s a fight to the death. We need the food industry to make healthier food and to make a profit,” says Mozaffarian. “The food industry is much more diverse and heterogeneous than tobacco or even cars. As long as we can help them—through carrots and sticks, tax incentives and disincentives—to move towards healthier products, then they are part of the solution. But we have to be vigilant, because they use a lot of the same tactics that tobacco did.”

Sow what we want to reap.

Americans overeat what our farmers overproduce.

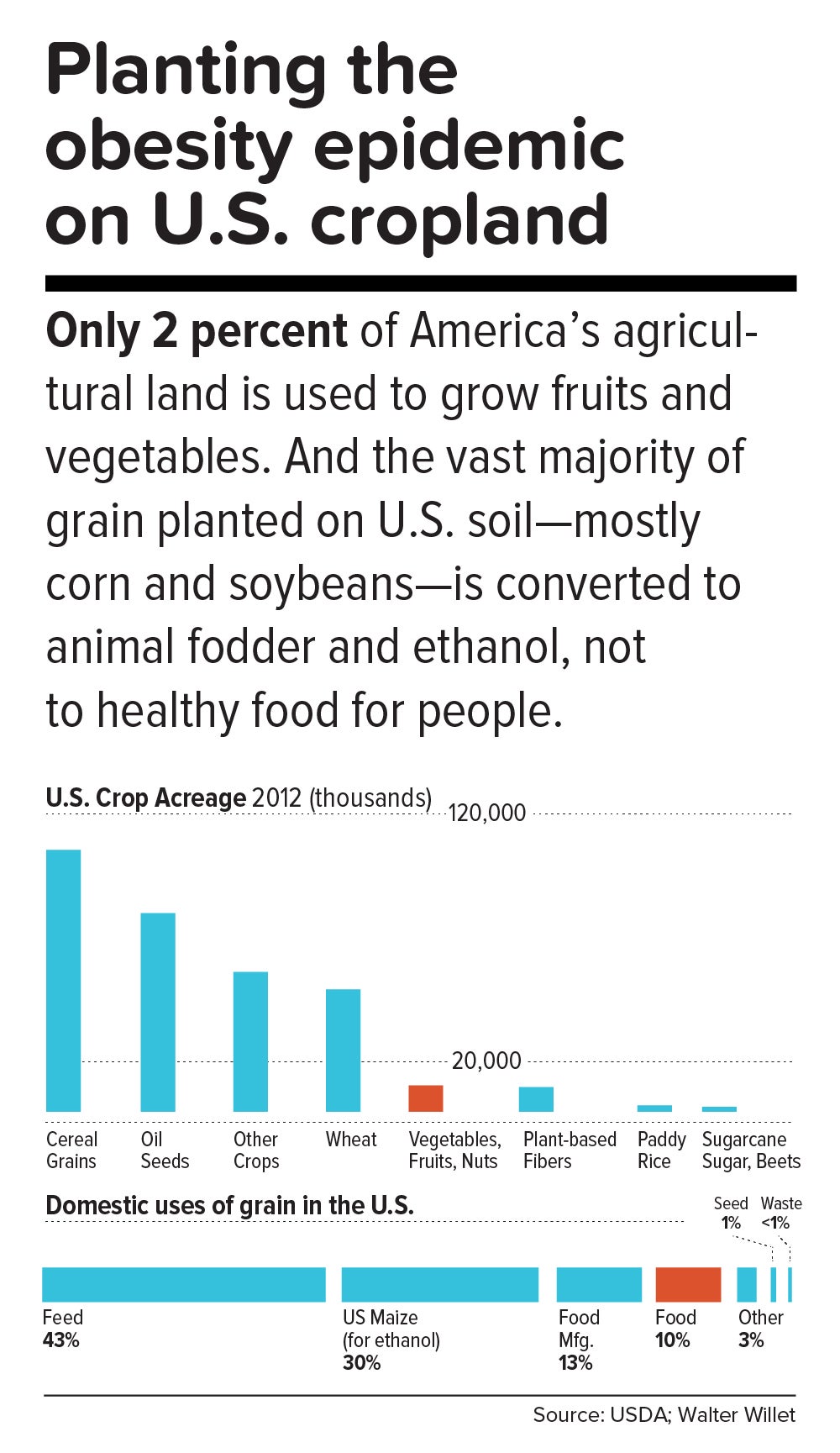

“The U.S. food system is egregiously terrible for human and planetary health,” says Walter Willett. It’s so terrible, Willett made a pie chart of American grain production consumed domestically. It shows that most of the country’s agricultural land goes to the two giant commodity crops: corn and soy. Most of those crops, in turn, go to animal fodder and ethanol, and are also heavily used in processed snack foods. Today, only about 10 percent of grain grown in the U.S. for domestic use is eaten directly by human beings. According to a 2013 report from the Union of Concerned Scientists, only 2 percent of U.S. farmland is used to grow fruits and vegetables, while 59 percent is devoted to commodity crops.

Historically, those skewed proportions made sense. Federal food policies, drafted with the goal of alleviating hunger, preferentially subsidize corn and soy production. And whereas corn or soybeans could be shipped for days on a train, fruits and vegetables had to be grown closer to cities by truck farmers so the produce wouldn’t spoil. But those long-ago constraints don’t explain today’s upside-down agricultural priorities.

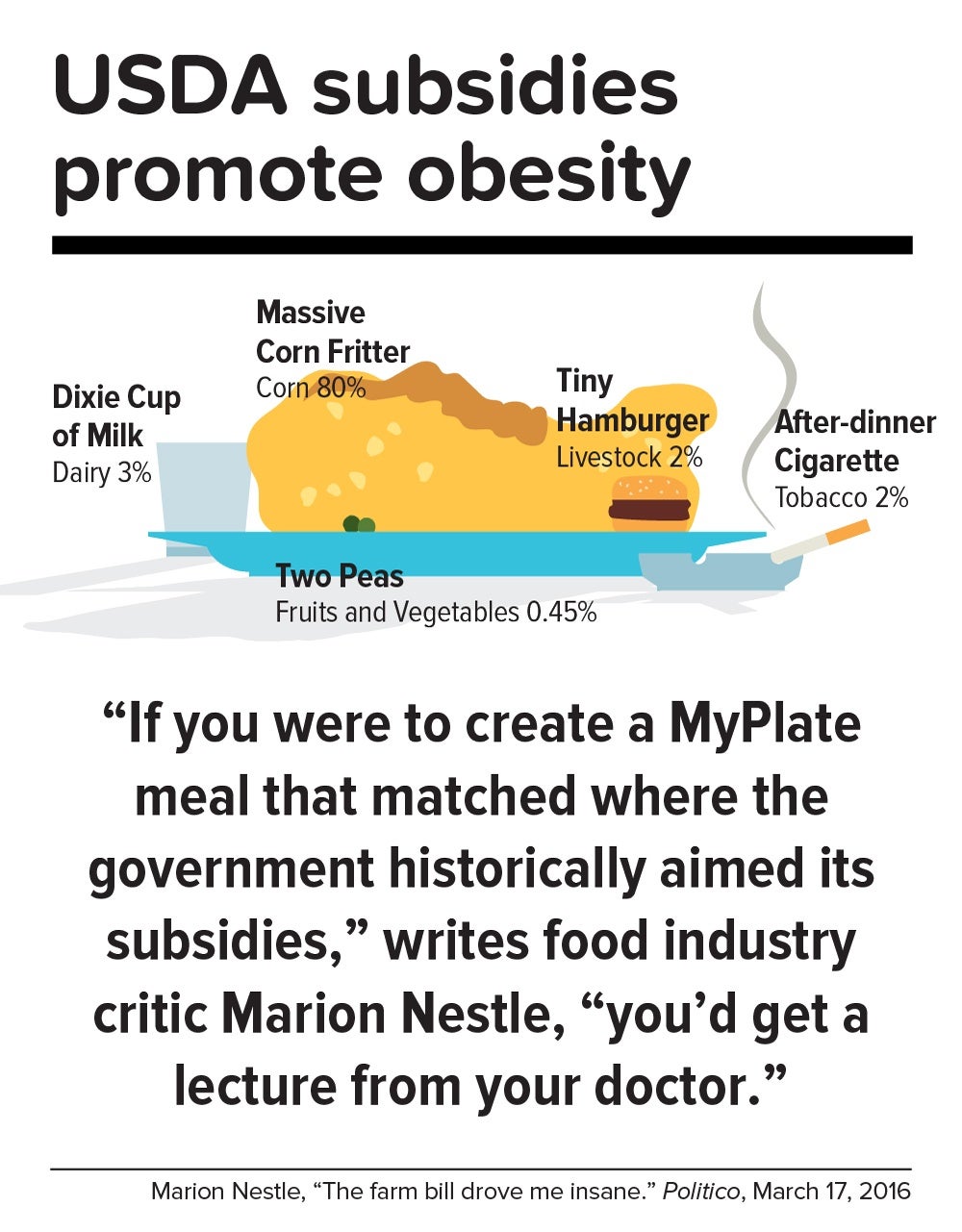

In a now-classic 2016 Politico article titled “The farm bill drove me insane,” Marion Nestle illustrated the irrational gap between what the government recommends we eat and what it subsidizes: “If you were to create a MyPlate meal that matched where the government historically aimed its subsidies, you’d get a lecture from your doctor. More than three-quarters of your plate would be taken up by a massive corn fritter (80 percent of benefits go to corn, grains and soy oil). You’d have a Dixie cup of milk (dairy gets 3 percent), a hamburger the size of a half dollar (livestock: 2 percent), two peas (fruits and vegetables: 0.45 percent) and an after-dinner cigarette (tobacco: 2 percent). Oh, and a really big linen napkin (cotton: 13 percent) to dab your lips.”

In this sense, the USDA marginalizes human health. Many of the foods that nutritionists agree are best for us—notably, fruits, vegetables, and tree nuts—fall under the bureaucratic rubric “specialty crops,” a category that also includes “dried fruits, horticulture, and nursery crops (including floriculture).” Farm bills, which get passed every five years or so, fortify the status quo. The 2014 Farm Bill, for example, provided $73 million for the Specialty Crop Block Grant Program in 2017, out of a total of about $25 billion for the USDA’s discretionary budget. (The next Farm Bill, now under debate, will be coming out in 2018.)

By contrast, a truly anti-obesigenic agricultural system would stimulate USDA support for crop diversity—through technical assistance, research, agricultural training programs, and financial aid for farmers who are newly planting or transitioning their land into produce. It would also enable farmers, most of whom survive on razor-thin profit margins, to make a decent living.

In the early 1970s, Finland’s death rate from coronary heart disease was the highest in the world, and in the eastern region of North Karelia—a pristine, sparsely populated frontier landscape of forest and lakes—the rate was 40 percent worse than the national average. Every family saw physically active men, loggers and farmers who were strong and lean, dying in their prime.

Thus was born the North Karelia Project, which became a model worldwide for saving lives by transforming lifestyles. The project was launched in 1972 and officially ended 25 years later. While its initial goal was to reduce smoking and saturated fat in the diet, it later resolved to increase fruit and vegetable consumption.

The North Karelia Project fulfilled all of these ambitions. When it started, for example, 86 percent of men and 82 percent of women smeared butter on their bread; by the early 2000s, only 10 percent of men and 4 percent of women so indulged. Use of vegetable oil for cooking jumped from virtually zero in 1970 to 50 percent in 2009. Fruit and vegetables, once rare visitors to the dinner plate, became regulars. Over the project’s official quarter-century existence, coronary heart disease deaths in working-age North Karelian men fell 82 percent, and life expectancy rose seven years.

The secret of North Karelia’s success was an all-out philosophy. Team members spent innumerable hours meeting with residents and assuring them that they had the power to improve their own health. The volunteers enlisted the assistance of an influential women’s group, farmers’ unions, homemakers’ organizations, hunting clubs, and church congregations. They redesigned food labels and upgraded health services. Towns competed in cholesterol-cutting contests. The national government passed sweeping legislation (including a total ban on tobacco advertising). Dairy subsidies were thrown out. Farmers were given strong incentives to produce low-fat milk, or to get paid for meat and dairy products based not on high-fat but on high-protein content. And the newly established East Finland Berry and Vegetable Project helped locals switch from dairy farming—which had made up more than two-thirds of agriculture in the region—to cultivation of cold-hardy currants, gooseberries, and strawberries, as well as rapeseed for heart-healthy canola oil.

“A mass epidemic calls for mass action,” says the project’s director, Pekka Puska, “and the changing of lifestyles can only succeed through community action. In this case, the people pulled the government—the government didn’t pull the people.”

Could the United States in 2017 learn from North Karelia’s 1970s grand experiment?

“Americans didn’t become an obese nation overnight. It took a long time—several decades, the same timeline as in individuals,” notes Frank Hu. “What were we doing over the past 20 years or 30 years, before we crossed this threshold? We haven’t asked these questions. We haven’t done this kind of soul-searching, as individuals or society as a whole.”

Today, Americans may finally be willing to take a hard look at how food figures in their lives. In a July 2015 Gallup phone poll of Americans 18 and older, 61 percent said they actively try to avoid regular soda (the figure was 41 percent in 2002); 50 percent try to avoid sugar; and 93 percent try to eat vegetables (but only 57.7 percent in 2013 reported they ate five or more servings of fruits and vegetables at least four days of the previous week).

Individual resolve, of course, counts for little in problems as big as the obesity epidemic. Most successes in public health bank on collective action to support personal responsibility while fighting discrimination against an epidemic’s victims. [To learn more about the perils of stigma against people with obesity, read “ The Scarlet F .”]

Yet many of public health’s legendary successes also took what seems like an agonizingly long time to work. Do we have that luxury?

“Right now, healthy eating in America is like swimming upstream. If you are a strong swimmer and in good shape, you can swim for a little while, but eventually you’re going to get tired and start floating back down,” says Margo Wootan, SD ’93, director of nutrition policy for the Center for Science in the Public Interest. “If you’re distracted for a second—your kid tugs on your pant leg, you had a bad day, you’re tired, you’re worried about paying your bills—the default options push you toward eating too much of the wrong kinds of food.”

But Wootan has not lowered her sights. “What we need is mobilization,” she says. “Mobilize the public to address nutrition and obesity as societal problems—recognizing that each of us makes individual choices throughout the day, but that right now the environment is stacked against us. If we don’t change that, stopping obesity will be impossible.”

The passing of power to younger generations may aid the cause. Millennials are more inclined to view food not merely as nutrition but also as narrative—a trend that leaves Duke University’s Kelly Brownell optimistic. “Younger people have been raised to care about the story of their food. Their interest is in where it came from, who grew it, whether it contributes to sustainable agriculture, its carbon footprint, and other factors. The previous generation paid attention to narrower issues, such as hunger or obesity. The Millennials are attuned to the concept of food systems.”

We are at a public health inflection point. Forty years from now, when we gaze at the high-resolution digital color photos from our own era, what will we think? Will we realize that we failed to address the obesity epidemic, or will we know that we acted wisely?

The question brings us back to the 1970s, and to Pekka Puska, the physician who directed the North Karelia Project during its quarter-century existence. Puska, now 71, was all of 27 and burning with big ideas when he signed up to lead the audacious effort. He knows the promise and the perils of idealism. “Changing the world may have been utopic,” he says, “but changing public health was possible.”

News from the School

At Convocation, Harvard Chan School graduates urged to meet climate and public health crises with fresh thinking, collective action

Graduation 2024: Award winners

Once a malaria patient, student now has sights set on stopping the deadly disease

Providing compassionate care to marginalized people

Over one billion obese people globally, health crisis must be reversed - WHO

Facebook Twitter Print Email

On World Obesity Day, marked on Friday, the World Health Organization (WHO) urged countries to do more to reverse what is a preventable health crisis.

According to recent data , more than one billion people worldwide are obese , including 650 million adults, 340 million adolescents and 39 million children. With the numbers still increasing, WHO estimates that by 2025, approximately 167 million people will become less healthy because they are overweight or obese.

Impacts of obesity

Overweight and obesity are defined as abnormal or excessive fat accumulation that may impair health. As a disease that impacts most body systems, obesity affects the heart, liver, kidneys, joints, and reproductive system.

WHO underlined that obesity also leads to a range of noncommunicable diseases (NCDs), such as type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, hypertension and stroke, various forms of cancer, as well as mental health issues.

According to the UN health agency, people with obesity are also three times more likely to be hospitalized for COVID-19 .

Key to prevention: act early

Worldwide obesity has nearly tripled since 1975.

WHO said the key to preventing obesity is to act early. For example, before even considering having a baby, get healthy.

“ Good nutrition in pregnancy, followed by exclusive breastfeeding until the age of 6 months and continued breastfeeding until two years and beyond, is best for all infants and young children,” WHO reiterated.

Global response

At the same time, countries need to work together to create a better food environment so that everyone can access and afford a healthy diet .

To achieve that, steps to be taken include restricting the marketing to children of food and drinks high in fats, sugar, and salt, taxing sugary drinks, and providing better access to affordable, healthy food.

Along with changes in diet , WHO also mentioned the need for exercise.

“Cities and towns need to make space for safe walking, cycling, and recreation, and schools need to help households teach children healthy habits from early on.”

WHO continues to address the global obesity crisis by monitoring global trends and prevalence, developing a broad range of guidance to prevent and treat overweight and obesity, and providing support and guidance for countries.

Action plan to stop obesity

Following a request from Member States, the WHO secretariat is also developing an acceleration action plan to stop obesity, tackle the epidemic in high burden countries and catalyze global action. The plan will be discussed at the 76 World Health Assembly to be held in May.

- food and nutrition

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Perspective

- Open access

- Published: 02 December 2022

Epidemiology and Population Health

Obesity and the cost of living crisis

- Eric Robinson ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-3586-5533 1

International Journal of Obesity volume 47 , pages 93–94 ( 2023 ) Cite this article

10k Accesses

9 Citations

73 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Public health

- Risk factors

2022 has seen the emergence of a global cost of living crisis driven by rapid increases in the cost of energy and food. The result will be a growing number of families experiencing short-term financial turmoil and long-term financial hardship [ 1 ]. Increasing inflation results in households with proportionately less disposable income, and this will invariably impact on food purchasing. One likely impact will be the tipping of many people from lesser economically developed countries into extreme poverty and starvation [ 2 ]. Furthermore, in the context of an already well-established obesity crisis, the cost of living crisis may also create the perfect storm for driving global obesity prevalence further upwards.

Families already have to choose between cheap and readily available energy-dense foods vs. more costly healthier food options, often financially and also in terms of preparation time. As financial hardship hits, choosing the latter will become more difficult. Households with the lowest incomes are less able to place long-term health at the top of their considerations when buying, choosing and cooking food. Recent research suggests that this is one likely reason why lower socioeconomic status is associated with higher BMI [ 3 ]. If left unchecked, the cost of living crisis has the potential to further widen socioeconomic inequalities in obesity by disproportionately affecting disadvantaged families and communities already at risk of obesity.

The stress of financial crises is thought to damage mental health, and the well-being of many of those experiencing financial hardship will be at risk [ 4 ]. Poorer mental health likely decreases motivation in the context of obesity management [ 5 ] and is a risk factor for increased weight gain among the general population, potentially through biopsychological mechanisms such as comfort eating [ 6 ]. Although research is less convincing and comprehensive in humans than in non-human animals, resource deprivation and insecurity may directly impact on biological systems to increase fat deposition and weight gain [ 7 ]. Well before the emergence of the current cost of living crisis, research had documented the concerning number of people worldwide living in food insecurity. Experiencing food insecurity is a risk factor for obesity and other health problems [ 8 ]. The cost of living crisis therefore has potential to move many more into food insecurity and further increase obesity among those already experiencing financial hardship.

Obesity research in the context of the current and future financial crises will have both theoretical and applied value. The COVID-19 pandemic stimulated a large amount of research into understanding how obesity increased risk of death, how those living with obesity were disproportionately affected, and the impact the pandemic has had on obesity prevalence [ 9 ]. The current cost of living crisis provides an (unfortunate) opportunity to study how and why diet, physical activity and obesity are affected in those experiencing acute financial hardship. Furthermore, documenting the impacts that the cost of living crisis has on absolute and relative inequalities in obesity prevalence will be important.

How countries respond to the cost of living crisis will matter, and invariably will differ from one government to another. Although there will be universal efforts to address inflation and financial hardship, in the context of obesity the devil will be in the detail. In recent years the UK government have implemented and proposed the introduction of a range of population-level anti-obesity measures including, among others, banning of price promotions and advertisement of unhealthy food products. However, in response to the cost of living crisis, there are suggestions that government will reverse the introduction of such measures in order to remove constraints on businesses and drive promote economic growth [ 10 ].

If governments deprioritise obesity policy to instead try and spur short-term economic growth, not only will obesity be worsened, but it is likely that there be damaging longer-term economic impacts. The current global burden of obesity is large and will continue to grow if upwards obesity prevalence trends continue. Obesity policy in many countries has historically been fragmented and not been considered in the wider context of other major societal challenges, such as climate change and financial crises. If this continues, then the obesity crisis will be with us for a very long time or even worse, indefinitely.

World Economic Forum. The cost-of-living crisis is having a global impact. Here’s what countries are doing to help. 2022. https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2022/09/cost-of-living-crisis-global-impact/

Ortiz-Juarez E, Molina G, Montoya-Aguire M. United Nations Development Programme, Cost-of-Living Report. 2022. https://www.undp.org/germany/publications/cost-living-report

Robinson E, Jones A, Marty L. The role of health-based food choice motives in explaining the relationship between lower socioeconomic position and higher BMI in UK and US adults. Int J Obes. 2022;46:1818–24.

Frasquilho D, Matos MG, Salonna F, Guerreiro D, Storti CC, Gaspar T, et al. Mental health outcomes in times of economic recession: a systematic literature review. BMC Public Health. 2015;16:1–40.

Article Google Scholar

Jones RA, Mueller J, Sharp SJ, Vincent A, Duschinsky R, Griffin SJ, et al. The impact of participant mental health on attendance and engagement in a trial of behavioural weight management programmes: secondary analysis of the WRAP randomised controlled trial. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Activity. 2021;18:1–3.

Konttinen H, Van Strien T, Männistö S, Jousilahti P, Haukkala A. Depression, emotional eating and long-term weight changes: a population-based prospective study. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Activity. 2019;16:1.

Nettle D, Andrews C, Bateson M. Food insecurity as a driver of obesity in humans: the insurance hypothesis. Behav Brain Sci. 2017;40:e105.

Moradi S, Mirzababaei A, Dadfarma A, Rezaei S, Mohammadi H, Jannat B, et al. Food insecurity and adult weight abnormality risk: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Nutr. 2019;58:45–61.

Jones RA, Christiansen P, Maloney NG, Duckworth JJ, Hugh-Jones S, Ahern AL, et al. Perceived weight-related stigma, loneliness, and mental wellbeing during COVID-19 in people with obesity: a cross-sectional study from ten European countries. Int J Obes. 2022;46:2120–7.

BBC News. Anti-obesity strategy to be reviewed due to cost-of-living crisis. 2022. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-politics-62900076 .

Download references

ER is funded by a European Research Council starter grant under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (Grant reference: PIDS, 803194).

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Psychology, Eleanor Rathbone Building, University of Liverpool, Liverpool, L69 7ZA, UK

Eric Robinson

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Eric Robinson .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

ER has previously received research funding from Unilever and the American Beverage Association for unrelated research projects.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions