6c. The Importance of Committees

Bills begin and end their lives in committees , whether they are passed into law or not. Hearings from interest groups and agency bureaucrats are held at the committee and subcommittee level, and committee members play key roles in floor debate about the bills that they foster.

Committees help to organize the most important work of Congress — considering, shaping, and passing laws to govern the nation. 8,000 or so bills go to committee annually. Fewer than 10% of those bills make it out for consideration on the floor.

Types of Committees

There are four types of congressional committees:

Committee Assignments

After each congressional election , political parties assign newly elected Representatives and Senators to standing committees. They consider a member's own wishes in making the assignments, but they also assess the needs of the committees, in terms of region of the country, personalities, and party connections.

Since the House has 435 members, most Representatives only serve on one or two committees. On the other hand, Senators often serve on several committees and subcommittees . Committee assignment is one of the most important decisions for a new member's future work in Congress. Usually, members seek appointment on committees that will allow them to serve their districts or state the most directly. However, a members from a "safe" district — where his or her reelection is not in jeopardy — and who wants to be a leader in Congress, may want to be named to a powerful committee, such as Foreign Relations, Judiciary, or the House Ways and Means . There they are more likely to come into contact with current leaders and perhaps even gain some media attention.

Standing Committees of Congress (as of 2021)

| Agriculture | Agriculture, Nutrition, and Forestry |

| Appropriations | Appropriations |

| Armed Services | Armed Services |

| Budget | Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs |

| Education and Labor | Budget |

| Energy and Commerce | Commerce, Science, and Transportation |

| Ethics | Energy and Natural Resources |

| Financial Services | Environment and Public Works |

| Foreign Affairs | Finance |

| House Administration | Foreign Relations |

| Judiciary | Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions |

| Natural Resources | Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions |

| Oversight and Reform | Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs |

| Rules | Judiciary |

| Science, Space and Technology | Rules and Administration |

| Small Business | Small Business and Entrepreneurship |

| Transportation and Infrastructure | Veterans Affairs |

| Veterans Affairs | |

| Ways and Means |

Report broken link

If you like our content, please share it on social media!

Copyright ©2008-2022 ushistory.org , owned by the Independence Hall Association in Philadelphia, founded 1942.

THE TEXT ON THIS PAGE IS NOT PUBLIC DOMAIN AND HAS NOT BEEN SHARED VIA A CC LICENCE. UNAUTHORIZED REPUBLICATION IS A COPYRIGHT VIOLATION Content Usage Permissions

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

12.6 Committees

Learning objectives.

After reading this section, you should be able to answer the following questions:

- What criteria do members use when seeking congressional committee assignments?

- What are the prestige committees in the House and Senate?

- What is the function of investigative committees?

In 1885, Woodrow Wilson famously observed, “Congress in session is Congress on public exhibition, whilst Congress in its committee-rooms is Congress at work” (Wilson, 1885). This statement is no less true today. Committees are the lifeblood of Congress. They develop legislation, oversee executive agencies and programs, and conduct investigations.

There are different types of committees that are responsible for particular aspects of congressional work. Standing committees are permanent legislative committees. Select committees are special committees that are formed to deal with a particular issue or policy. Special committees can investigate problems and issue reports. Joint committees are composed of members of the House and Senate and handle matters that require joint jurisdiction, such as the Postal Service and the Government Printing Office. Subcommittees handle specialized aspects of legislation and policy.

Committee Assignments

Members seek assignments to committees considering the overlapping goals of getting reelected, influencing policy, and wielding power and influence. They can promote the interests of their constituencies through committee service and at the same time help their chances at reelection. Members from rural districts desire appointments to the Agriculture Committee where they can best influence farm policy. Those most interested in foreign policy seek appointment to committees such as the House Foreign Relations and Senate International Affairs Committees, where they can become embroiled in the pressing issues of the day. Power or prestige committee assignments in the House include Appropriations, Budget, Commerce, Rules, and Ways and Means. The most powerful committees in the Senate are Appropriations, Armed Services, Commerce, Finance, and Foreign Relations.

House and Senate Committees

A list and description of House and Senate committees can be found at https://www.govtrack.us/congress/committees/ .

Table 12.1 Congressional Committees

Most House members end up getting assigned to at least one committee that they request. In the House, committee assignments can be a ticket to visibility and influence. Committees provide House members with a platform for attracting media attention as journalists will seek them out as policy specialists. Senate committee assignments are not as strongly linked to press visibility as virtually every senator is appointed to at least one powerful committee. The average senator serves on eleven committees and subcommittees, while the average House member serves on five.

Figure 12.11

In the 1950s, Senator Estes Kefauver used controversial comics like “Frisco Mary” to generate press attention for his hearings on juvenile delinquency. This practice of using powerful exhibits to attract media attention to issues continues today.

Wikimedia Commons – public domain.

Service on powerful subcommittees can provide a platform for attracting media attention. In 1955, the Senate Subcommittee on Juvenile Delinquency staged three days of hearings in New York City as part of its investigation into allegations brought by Senator Estes Kefauver (D-TN), a subcommittee member, that violent comic books could turn children into criminals. The press-friendly hearings featured controversial speakers and slides of comic strips depicting a machine gun–toting woman character named “Frisco Mary” blowing away law enforcement officials without remorse that were circulated widely in the media. Kefauver anticipated that the press generated by these hearings would help him gain publicity for a bid to get on the 1956 Democratic presidential ticket. He lost the presidential nomination battle but ended up the vice presidential candidate for the losing side (Nyberg, 1998).

Committee Work

Committees are powerful gatekeepers. They decide the fate of bills by determining which ones will move forward and be considered by the full House and Senate. Committee members have tremendous influence over the drafting and rewriting of legislation. They have access to experts and information, which gives them an advantage when debating bills on the floor (Shepsle & Weingast).

Committee chairs are especially influential, as they are able to employ tactics that can make or break bills. Powerful chairs master the committee’s subject matter, get to know committee members well, and form coalitions to back their positions. Chairs can reward cooperative members and punish those who oppose them by granting or withholding favors, such as supporting pork barrel legislation that will benefit a member’s district (Fenno, 1973).

Most committee work receives limited media coverage. Investigative hearings are the exception, as they can provide opportunities for high drama.

Committee Investigations

Conducting investigations is one of the most public activities in which congressional committees engage. During the Progressive Era of the 1890s through 1920s, members could gain the attention of muckraking journalists by holding investigative hearings to expose corruption in business and government. The first of these was the 1913 “Pujo hearings,” in which Rep. Arsene Pujo (D-LA) headed a probe of Wall Street financiers. High-profile investigations in the 1920s included an inquiry into the mismanagement of the Teapot Dome oil reserves. During the Great Depression of the 1930s, Congress conducted an investigation of the stock market, targeting Wall Street once again. Newspapers were willing to devote much front-page ink to these hearings, as reports on the hearings increased newspaper readership. In 1950, Senator Kefauver held hearings investigating organized crime that drew 30 million television viewers at a time when the medium was new to American homes (Mayhew, 2000).

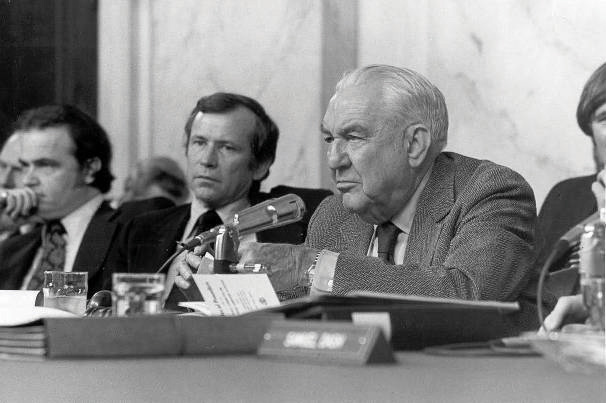

The Senate convened a special committee to investigate the Watergate burglaries and cover-up in 1973. The burglars had been directed by President Richard Nixon’s reelection committee to break into and wiretap the Democratic National Committee headquarters at the Watergate building complex. The Watergate hearings became a national television event as 319 hours of the hearings were broadcast and watched by 85 percent of American households. Gavel-to-gavel coverage of the hearings was broadcast on National Public Radio. The senators who conducted the investigation, especially Chairman Sam Ervin (D-NC) and Senator Howard Baker (R-TN), became household names. The hearings resulted in the conviction of several of President Nixon’s aides for obstruction of justice and ultimately led to Nixon’s resignation (Gray, 1984).

Figure 12.12

The Senate Watergate hearings in 1973 were a major television and radio event that brought Congress to the attention of the entire nation. Film clips of highlights from the Watergate hearings are available on the Watergate Files website of the Gerald R. Ford Library & Museum.

Wikimedia Commons – CC BY-SA 3.0.

In 2002, the House Financial Services Committee held thirteen hearings to uncover how Enron Corporation was able to swindle investors and drive up electricity rates in California while its executives lived the high life. Prior to the hearings, which made “Enron” a household word, there was little press coverage of Enron’s questionable operating procedures.

Enron’s Skilling Answers Markey at Hearing; Eyes Roll

(click to see video)

A clip of the Enron hearings before the House illustrates how Congress exercises its investigative power.

Enduring Image

The House Un-American Activities Committee and Hollywood

Following World War II, chilly relations existed between the United States and the Communist Soviet Union, a nation that had emerged as a strong power and had exploded an atomic bomb (Giglio, 2000). The House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC), which was established in 1939 to investigate subversive activities, decided to look into allegations that Communists were threatening to overthrow American democracy using force and violence. People in government, the labor movement, and the motion picture industry were accused of being communists. Especially sensational were hearings where Hollywood actors, directors, and writers were called before the HUAC. It was not uncommon for people in Hollywood to have joined the Communist Party during the Great Depression of the 1930s, although many were inactive at the time of the hearings. HUAC alleged that film “was the principle medium through which Communists have sought to inject their propaganda” (Gianos, 1998).

Those accused of being communists, nicknamed “reds,” were called before the HUAC. They were subject to intense questioning by members of Congress and the committee’s counsel. In 1947, HUAC held hearings to investigate the influence of Communists in Hollywood. The “ Hollywood Ten ,” a group of nine screenwriters, including Ring Lardner, Jr. and Dalton Trumbo, and director Edward Dmytryk, were paraded before the committee. Members of Congress shouted to the witnesses, “Are you now or have you ever been a member of the Communist Party?” They were commanded to provide the names of people they knew to be Communists or face incarceration. Some of the Hollywood Ten responded aggressively to the committee, not answering questions and making statements asserting their First Amendment right to free expression. Blinding flashbulbs provided a constant backdrop to the hearings, as photographers documented images of dramatic face-offs between committee members and the witnesses. Images of the hearings were disseminated widely in front-page photos in newspapers and magazines and on television.

The HUAC hearings immortalized the dramatic image of the congressional investigation featuring direct confrontations between committee members and witnesses.

The Hollywood Ten refused to cooperate with HUAC, were cited for contempt of Congress, and sent to prison (Ceplair, 1994). They were blacklisted by the leaders of the film industry, along with two hundred other admitted or suspected communists, and were unable to work in the motion picture industry. Pressured by personal and financial ruin, Edward Dmytryk eventually gave in to HUAC’s demands.

Commercial films have perpetuated the dramatic image of congressional hearings made popular by the HUAC investigations. Films released around the time of the hearings tended to justify the actions the HUAC, including Big Jim McClain (1952) and On the Waterfront (1954). The few films made later are more critical. Woody Allen plays a small-time bookie who fronts for blacklisted writers in The Front (1976), a film depicting the personal toll exacted by the HUAC and blacklisting. In Guilty by Suspicion (1991), Robert DeNiro’s character refuses to name names and jeopardizes his career as a director. One of the Hollywood Ten (2000), graphically depicts film director Herbert Biberman’s experience in front of the HUAC before he is jailed for not cooperating.

Key Takeaways

Much of the important work in Congress is accomplished through committees. The fate of legislation—which bills will make it to the floor of the House and Senate—is determined in committees. Members seek committee assignments considering their desire to influence policy, exert influence, and get reelected. Most committee work receives little, if any, media coverage. Investigative committees are the exception when they are covering hearings on high-profile matters.

- What is the role of congressional committees? What determines which committees members of Congress seek to be on?

- What are generally considered to be the most powerful and prestigious committees in Congress? What do you think makes those committees so influential?

Ceplair, L., “The Hollywood Blacklist,” in The Political Companion to American Film , ed. Gary Crowdus (Chicago: Lakeview Press, 1994), 193–99.

Fenno, R., Congressmen in Committees (Boston: Little, Brown, 1973).

Gianos, P. L., Politics and Politicians in American Film (Westport, CT: Praeger, 1998), 65.

Giglio, E., Here’s Looking at You (New York: Peter Lang, 2000).

Gray, R., Congressional Television: A Legislative History (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1984).

Mayhew, D. R., America’s Congress (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2000).

Nyberg, A. K., Seal of Approval (Oxford: University of Mississippi Press, 1998).

Shepsle, K. A., and Barry R. Weingast, “The Institutional Foundations of Committee Power,” American Political Science Review 81: 85–104.

Wilson, W., Congressional Government (New York: Houghton Mifflin, 1885), 69.

American Government and Politics in the Information Age Copyright © 2016 by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

- Search Menu

Sign in through your institution

- Advance articles

- Editor's Choice

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access

- Aims and Scope

- About The Hansard Society

- Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Dispatch Dates

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

- < Previous

Committee Assignments: Theories, Causes and Consequences

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Shane Martin, Tim A Mickler, Committee Assignments: Theories, Causes and Consequences, Parliamentary Affairs , Volume 72, Issue 1, January 2019, Pages 77–98, https://doi.org/10.1093/pa/gsy015

- Permissions Icon Permissions

Conventional wisdom suggests that a strong legislature is built on a strong internal committee system, both in terms of committee powers and the willingness of members to engage in committee work. Committee assignments are the behavioural manifestation of legislative organisation. Despite this, much remains unknown about how committee assignments happen and with what causes and consequences. Our focus in this article is on providing the context for, and introducing new research on, what we call the political economy of committee assignments —which members get selected to sit on which committees, why and with what consequences.

Personal account

- Sign in with email/username & password

- Get email alerts

- Save searches

- Purchase content

- Activate your purchase/trial code

- Add your ORCID iD

Institutional access

Sign in with a library card.

- Sign in with username/password

- Recommend to your librarian

- Institutional account management

- Get help with access

Access to content on Oxford Academic is often provided through institutional subscriptions and purchases. If you are a member of an institution with an active account, you may be able to access content in one of the following ways:

IP based access

Typically, access is provided across an institutional network to a range of IP addresses. This authentication occurs automatically, and it is not possible to sign out of an IP authenticated account.

Choose this option to get remote access when outside your institution. Shibboleth/Open Athens technology is used to provide single sign-on between your institution’s website and Oxford Academic.

- Click Sign in through your institution.

- Select your institution from the list provided, which will take you to your institution's website to sign in.

- When on the institution site, please use the credentials provided by your institution. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

- Following successful sign in, you will be returned to Oxford Academic.

If your institution is not listed or you cannot sign in to your institution’s website, please contact your librarian or administrator.

Enter your library card number to sign in. If you cannot sign in, please contact your librarian.

Society Members

Society member access to a journal is achieved in one of the following ways:

Sign in through society site

Many societies offer single sign-on between the society website and Oxford Academic. If you see ‘Sign in through society site’ in the sign in pane within a journal:

- Click Sign in through society site.

- When on the society site, please use the credentials provided by that society. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

If you do not have a society account or have forgotten your username or password, please contact your society.

Sign in using a personal account

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members. See below.

A personal account can be used to get email alerts, save searches, purchase content, and activate subscriptions.

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members.

Viewing your signed in accounts

Click the account icon in the top right to:

- View your signed in personal account and access account management features.

- View the institutional accounts that are providing access.

Signed in but can't access content

Oxford Academic is home to a wide variety of products. The institutional subscription may not cover the content that you are trying to access. If you believe you should have access to that content, please contact your librarian.

For librarians and administrators, your personal account also provides access to institutional account management. Here you will find options to view and activate subscriptions, manage institutional settings and access options, access usage statistics, and more.

Short-term Access

To purchase short-term access, please sign in to your personal account above.

Don't already have a personal account? Register

| Month: | Total Views: |

|---|---|

| March 2018 | 34 |

| April 2018 | 25 |

| May 2018 | 33 |

| June 2018 | 24 |

| July 2018 | 35 |

| August 2018 | 18 |

| September 2018 | 7 |

| October 2018 | 9 |

| November 2018 | 30 |

| December 2018 | 29 |

| January 2019 | 30 |

| February 2019 | 30 |

| March 2019 | 56 |

| April 2019 | 17 |

| May 2019 | 27 |

| June 2019 | 16 |

| July 2019 | 20 |

| August 2019 | 14 |

| September 2019 | 43 |

| October 2019 | 30 |

| November 2019 | 17 |

| December 2019 | 15 |

| January 2020 | 24 |

| February 2020 | 21 |

| March 2020 | 16 |

| April 2020 | 21 |

| May 2020 | 15 |

| June 2020 | 16 |

| July 2020 | 29 |

| August 2020 | 11 |

| September 2020 | 15 |

| October 2020 | 23 |

| November 2020 | 18 |

| December 2020 | 12 |

| January 2021 | 9 |

| February 2021 | 11 |

| March 2021 | 17 |

| April 2021 | 8 |

| May 2021 | 16 |

| June 2021 | 23 |

| July 2021 | 61 |

| August 2021 | 24 |

| September 2021 | 62 |

| October 2021 | 60 |

| November 2021 | 46 |

| December 2021 | 48 |

| January 2022 | 10 |

| February 2022 | 10 |

| March 2022 | 14 |

| April 2022 | 16 |

| May 2022 | 6 |

| June 2022 | 2 |

| July 2022 | 1 |

| August 2022 | 10 |

| September 2022 | 31 |

| October 2022 | 6 |

| November 2022 | 6 |

| December 2022 | 6 |

| January 2023 | 6 |

| February 2023 | 11 |

| March 2023 | 26 |

| April 2023 | 18 |

| May 2023 | 5 |

| June 2023 | 6 |

| July 2023 | 4 |

| August 2023 | 8 |

| September 2023 | 12 |

| October 2023 | 11 |

| November 2023 | 6 |

| December 2023 | 20 |

| January 2024 | 3 |

| February 2024 | 15 |

| March 2024 | 10 |

| April 2024 | 9 |

| May 2024 | 8 |

| June 2024 | 3 |

Email alerts

Citing articles via.

- About Parliamentary Affairs

- Contact the Hansard Society

- Despatch Box

- Recommend to your Library

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 1460-2482

- Print ISSN 0031-2290

- Copyright © 2024 Hansard Society

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Rights and permissions

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

Committees – History & Purpose In The United States Congress

LISTEN ON SOUNDCLOUD:

The Constitution is entirely silent on the question of committees in Congress. It does not require the existence of any committees at all. In fact, during the first few decades of our nation’s history, there were no permanent standing committees. Those early congresses, many of which contained so many of the Framers of the Constitution, decided that the nation’s laws could be crafted without the assistance of committees.

In other words, we have not always had committees and we have not always needed them. Even when we have had committees in Congress, their power, purposes, and processes have changed dramatically over time. Committees began as weak bodies accountable to everyone in Congress, eventually became the most powerful institutions in Congress, and recently have seen their influence diminish. Understanding the history of committees’ rise and fall helps us to see what effect they have on Congress. While committees can and should play a role in helping Congress do its work, they often have perverse effects on how our representatives behave and the laws they enact.

Originally, Congress used “Select” or ad hoc committees to do its work. These committees were not permanent, but merely temporary, formed only for a single purpose. When an issue was presented to the whole House of Representatives for debate, the members would discuss it and come to agreement before sending it to a select committee. Once the select committee wrote a bill based on the agreement reached by the entire House, it would dissolve, and the bill would go to the floor of the House for further discussion and passage. In this process, the committees’ role was minimal, and serving on a committee did not give a member any additional power.

During the 1810s and 1820s, Congress saw the need to create permanent committees with settled jurisdiction. These “Standing” committees, which remain in existence today, took on more authority, including the ability to write and amend legislation. Members sought to be assigned to the committees that gave them more influence over the issues that mattered to their constituents. For instance, members from farm districts might wish to be on agricultural committees so that they could influence legislation that affected their constituents’ interests.

These standing committees, therefore, present both advantages and problems for Congress’s functioning. On the one hand, they allow for a more efficient legislative process and give Congress greater expertise on specific issues. Instead of being forced to discuss every issue as a whole body, committees allow Congress to divide into smaller units to screen legislation, managing its workload. It also allows members to specialize in certain areas through longstanding membership on committees. On the other hand, if committees have influence over legislation, and members seek committee assignments that allow them to advance their constituents’ interests, then committees can enable special interests to gain greater influence in the legislative process.

The history of committees’ rise and fall in Congress shows these advantages and disadvantages in action. During the middle part of the 19th Century, committees became so powerful that Woodrow Wilson famously wrote that “Congress in session is Congress on public exhibition, whilst Congress in its committee-rooms is Congress at work.” Committees wrote most legislation, and amendments to their legislation were minimal. Once a bill reached the floor, it would be passed in largely the same form as it was written by a committee.

After the Civil War, however, strong political parties emerged to discipline these committees. Members like the Speaker of the House controlled the legislative process through the power of recognition, the power of appointment, and through controlling the rules committee which was in charge of sending bills to the floor for passage. Committees and their chairs knew that they could not pass legislation if the party leadership opposed it. The emergence of party leadership allowed the majority party to resist the influence of narrow, special interests that might dominate at the committee level.

But the party discipline of the post-Civil War period was short-lived. In the early 20th Century, Progressives succeeded in weakening the Speaker of the House, and imposed new rules that limited party leaders’ influence over legislation. In 1910 George Norris led the minority Democrats of the House in a revolt against Speaker Joe Cannon. Soon after the Speaker was stripped of his power to decide membership on House committees, and power became decentralized. As a result, committees once again emerged as the most powerful bodies in Congress. They were so powerful that their chairs gained complete control of the legislative agenda. These committee chairs were called the “barons” of Congress. Unfortunately, they refused to follow the will of Congress as a whole, and followed their own wishes instead. Congress became out of touch with the people in the middle of the 20th Century as a result of the power and autonomy of these committees.

Today, committees are weaker than they were in the middle of the last century. Both parties limit the tenure of their committee chairs, so that they do not become too powerful and independent of the whole Congress. Members of Congress receive their committee assignments from their parties, and can be removed from committees if they fail to act in the party’s interest. Committees are still very powerful, but they are now more accountable to parties than they were fifty years ago. The late-19th Century era of party dominance has not returned, but we are no longer in the era of strong, independent committees either.

This history suggests two lessons for us today. First, the rules regarding how committee members are chosen and what powers committees have to write legislation are highly important to how Congress works. If committee power is unchecked by Congress as a whole, their advantages (efficiency and expertise) and disadvantages (influence of narrow interests) will be increased. If committees are more accountable to Congress as a whole, including their party leaders, Congress will be more inefficient and have less expertise, but narrow interests will be disciplined by the national majority. Many of the problems we see in Congress today are the result of reforms to the committee process.

Second, committees provide Congress with a double-edged sword. They help Congress do its job, but they also threaten to subvert the legislative process, dividing Congress into many subunits, each of which advance a narrow, special interest rather than the common good. If they are not held accountable to the whole Congress, through rules that allow party leaders to influence committees and allow members to amend legislation after it leaves committees, they can threaten the very purpose of Congress: to make laws that reflect the sense of the majority rather than the interests of the powerful.

Joseph Postell is Associate Professor of Political Science at the University of Colorado-Colorado Springs. He is the author of Bureaucracy in America: The Administrative State’s Challenge to Constitutional Government . He is also the editor of Rediscovering Political Economy and Toward an American Conservatism: Constitutional Conservatism during the Progressive Era . Follow him on Twitter @JoePostell.

Samuel Postell is a Ph.D. student at the University of Dallas.

A neatly concise explanation of one of the main ways the power of our government has become isolated from the influence of the people they were elected to serve.

I agree, excellent essay. I believe the overarching theme is that when checks and balances do not exist or are poorly designed, power will coalesce into a few hands. Based on the essay it appears C&Bs are being applied to the committees. But where are the C&Bs for House and Senate leaders (bosses). The notion they can prevent the people’s voice from being heard and addressed by stopping legislation from reaching the floor is repulsive – at best.

One of my favorite quotes applies to this essay, “There are men in all ages who mean to govern well, but they mean to govern. They promise to be good masters, but they mean to be masters” ― Daniel Webster

Join the discussion! Post your comments below.

Leave a reply cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Last updated 20/06/24: Online ordering is currently unavailable due to technical issues. We apologise for any delays responding to customers while we resolve this. For further updates please visit our website: https://www.cambridge.org/news-and-insights/technical-incident

We use cookies to distinguish you from other users and to provide you with a better experience on our websites. Close this message to accept cookies or find out how to manage your cookie settings .

Login Alert

- > Journals

- > American Political Science Review

- > Volume 55 Issue 2

- > Committee Assignments in the House of Representatives*

Article contents

Committee assignments in the house of representatives *.

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 01 August 2014

Any attempt to understand the legislative process, or to reckon how well it fulfills its purported functions, calls for a careful consideration of the relationships among congressmen. The beginning weeks of the first session of every congress are dominated by the internal politics of one phase of those relationships, the assignment of members to committees. Since congressmen devote most of their energies—constituents' errands apart—to the committees on which they serve, the political stakes in securing a suitable assignment are high. Competition for the more coveted posts is intense in both houses; compromises and adjustments are necessary. Members contest with each other over particularly desirable assignments; less frequently, one member challenges the entire body, as when Senator Wayne Morse fought for his committee assignments in 1953.

The processes and patterns of committee assignments have been only generally discussed by political scientists and journalists. Perhaps the reason for this is too ready an acceptance of the supposition that these assignments are made primarily on the basis of seniority. Continuous service, it is true, insures a member of his place on a committee once he is assigned, but seniority may have very little to do with transfers to other committees, and it has virtually nothing to do with the assignment of freshman members. On what basis, then, are assignments made? Surely, not on the basis of simple random selection.

A recent student sees the committee assignment process as analogous to working out a “giant jig saw puzzle” in which the committees-on-committees observe certain limitations.

Access options

This study was made possible by the support of the Ford Foundation and Wayne State University. Neither of them, of course, is responsible for any errors of fact or interpretation.

1 Huitt , Ralph K. , “ The Morse Committee Assignment Controversy: A Study in Senate Norms ,” this Review ( 06 , 1957 ), pp. 313 – 329 Google Scholar

2 Goodwin , George Jr. , “ The Seniority System in Congress ,” this Review ( 06 , 1959 ), pp. 412 – 436 Google Scholar .

3 Data have been derived from unstructured interviews with members and staffs of the various committees, personal letters and similar papers, official documents of various types, and personal observations. I interviewed members of the committees-on-committees, deans of state delegations, and other members affected by the decisions. The survey covered the 80th through the 86th Congresses, with special attention to the 86th.

4 The Congressional Party: A Case Study ( New York , 1959 ), p. 195 Google Scholar .

5 In the 87th Congress a serious conflict arose over the Rules Committee ratio. There was newspaper talk of “purging” two ranking Democratic members, Colmer and Whitten, both from Mississippi, who had supported the Dixiecrat presidential candidacy of Mississippi's Governor Barnett in the 1960 campaign, and who regularly voted with Chairman Howard Smith in the coalition of southern Democrats and conservative Republicans that controlled theRules Committee. But Speaker Rayburn, in order to break the “stranglehold” the coalition would have over the impending legislation of the Kennedy Administration, advocated instead an increase in the Committee's size. The conflict was resolved in Rayburn's favor by a narrow margin with the entire House participating in the vote. The subsequent appointments, however, were made along the lines suggested in this article.

6 “ The Role of the Representative: Some Empirical Observations on the Theory of Edmund Burke ,” this Review, Vol. 53 ( 09 1959 ), pp. 742 – 756 Google Scholar .

7 Cf. Scher , Seymour , “ Congressional Committee Members as Independent Agency Overseers: A Case Study ,” this Review, Vol. 54 ( 12 1960 ), pp. 911 – 920 Google Scholar .

8 Truman, op. cit. , p. 279.

This article has been cited by the following publications. This list is generated based on data provided by Crossref .

- Google Scholar

View all Google Scholar citations for this article.

Save article to Kindle

To save this article to your Kindle, first ensure [email protected] is added to your Approved Personal Document E-mail List under your Personal Document Settings on the Manage Your Content and Devices page of your Amazon account. Then enter the ‘name’ part of your Kindle email address below. Find out more about saving to your Kindle .

Note you can select to save to either the @free.kindle.com or @kindle.com variations. ‘@free.kindle.com’ emails are free but can only be saved to your device when it is connected to wi-fi. ‘@kindle.com’ emails can be delivered even when you are not connected to wi-fi, but note that service fees apply.

Find out more about the Kindle Personal Document Service.

- Volume 55, Issue 2

- Nicholas A. Masters (a1)

- DOI: https://doi.org/10.2307/1952245

Save article to Dropbox

To save this article to your Dropbox account, please select one or more formats and confirm that you agree to abide by our usage policies. If this is the first time you used this feature, you will be asked to authorise Cambridge Core to connect with your Dropbox account. Find out more about saving content to Dropbox .

Save article to Google Drive

To save this article to your Google Drive account, please select one or more formats and confirm that you agree to abide by our usage policies. If this is the first time you used this feature, you will be asked to authorise Cambridge Core to connect with your Google Drive account. Find out more about saving content to Google Drive .

Reply to: Submit a response

- No HTML tags allowed - Web page URLs will display as text only - Lines and paragraphs break automatically - Attachments, images or tables are not permitted

Your details

Your email address will be used in order to notify you when your comment has been reviewed by the moderator and in case the author(s) of the article or the moderator need to contact you directly.

You have entered the maximum number of contributors

Conflicting interests.

Please list any fees and grants from, employment by, consultancy for, shared ownership in or any close relationship with, at any time over the preceding 36 months, any organisation whose interests may be affected by the publication of the response. Please also list any non-financial associations or interests (personal, professional, political, institutional, religious or other) that a reasonable reader would want to know about in relation to the submitted work. This pertains to all the authors of the piece, their spouses or partners.

- Lesson Plans

- Teacher's Guides

- Media Resources

Congressional Committees and the Legislative Process

U.S. Capitol dome.

Library of Congress

This lesson plan introduces students to the pivotal role that Congressional committees play in the legislative process, focusing on how their own Congressional representatives influence legislation through their committee appointments. Students begin by reviewing the stages of the legislative process, then learn how committees and subcommittees help determine the outcome of this process by deciding which bills the full Congress will consider and by shaping the legislation upon which votes are finally cast. With this background, students research the committee and subcommittee assignments of their Congressional representatives, then divide into small groups to prepare class reports on the jurisdictions of these different committees and their representatives' special responsibilities on each one. Finally, students consider why representation on these specific committees might be important to the people of their state or community, and examine how the committee system reflects some of the basic principles of American federalism.

Guiding Questions

What role do Committees play during the legislative process?

How is Committee membership determined?

What role do Committees play with regard to oversight and checks and balances?

Learning Objectives

Analyze the legislative process of the United States Congress by focusing on the role of Committees.

Evaluate how Congressional representatives can influence legislation through their specific committee assignments.

Evaluate how Committees uphold the Constitutional responsibilities of the Legislative Branch.

Lesson Plan Details

NCSS.D2.His.1.9-12. Evaluate how historical events and developments were shaped by unique circumstances of time and place as well as broader historical contexts.

NCSS.D2.His.2.9-12. Analyze change and continuity in historical eras.

NCSS.D2.His.3.9-12. Use questions generated about individuals and groups to assess how the significance of their actions changes over time and is shaped by the historical context.

NCSS.D2.His.12.9-12. Use questions generated about multiple historical sources to pursue further inquiry and investigate additional sources.

NCSS.D2.His.14.9-12. Analyze multiple and complex causes and effects of events in the past.

NCSS.D2.His.15.9-12. Distinguish between long-term causes and triggering events in developing a historical argument.

NCSS.D2.His.16.9-12. Integrate evidence from multiple relevant historical sources and interpretations into a reasoned argument about the past.

Begin this lesson by guiding students through the basic process by which a bill becomes law in the United States Congress. The Schoolhouse Rock cartoon "I'm Just a Bill" below provides a look at the process and can be accompanied by a flow-chart diagram of this process.

A detailed explanation of the legislative process is available through EDSITEment at the CongressLink website. At the website homepage, click "Table of Contents" in the lefthand menu, then look under the heading, "Know Your Congress" for the link to How Our Laws Are Made , which describes lawmaking from the House of Representatives' point of view.

For a corresponding description from the Senate's perspective, look under the "Know Your Congress" heading for the link to "Information about Congress," then select "... The Legislative Process," and click " ... Enactment of a Law ." CongressLink also provides access to a more succinct account of the legislative process: on the "Table of Contents" page, scroll down and click "Related Web Sites," then scroll down again and click THOMAS , a congressional information website maintained by the Library of Congress. Click "About the U.S. Congress" and select "About the U.S. Congress" from the list that follows for a chapter from the U.S. Government Manual that includes this outline of the process:

- When a bill ... is introduced in the House, [it is assigned] to the House committee having jurisdiction.

- If favorably considered, it is reported to the House either in its original form or with recommended amendments.

- If ... passed by the House, it is messaged to the Senate and referred to the committee having jurisdiction.

- In the Senate committee the bill, if favorably considered, may be reported in the form it is received from the House, or with recommended amendments.

- The approved bill ... is reported to the Senate and, if passed by that body, returned to the House.

- If one body does not accept the amendments to a bill by the other body, a conference committee comprised of Members of both bodies is usually appointed to effect a compromise.

- When the bill ... is finally approved by both Houses, it is signed by the Speaker ... and the Vice President ... and is presented to the President.

- Once the President's signature is affixed, the measure becomes a law. If the President vetoes the bill, it cannot become law unless it is re-passed by a two-thirds vote of both Houses.

Point out to students the important role that Congressional committees play in this process. Public attention usually focuses on the debate over legislation that occurs on the floor of the House and Senate, but in order for a bill to reach the floor on either side, it must first be approved by a committee, which can also amend the bill to reflect its views on the underlying issue. Congressional committees, in other words, largely control the legislative process by deciding which bills come to a vote and by framing the language of each bill before it is debated.

Provide students with background on the organization and operation of Congressional committees, using resources available through the U.S. Congress website. A schedule of Congressional committee hearings can be used to identify topics currently under consideration.

- Although committees are not mentioned in the Constitution, Congress has used committees to manage its business since its first meetings in 1789.

- Committees enable Congress to divide responsibility for its many tasks, including legislation, oversight, and internal administration, and thereby cope effectively with the great number and complexity of the issues placed before it.

- There are today approximately 200 Congressional committees and subcommittees in the House and Senate, each of which is responsible for considering all matters that fall within its jurisdiction.

- Congress has three types of committees: (1) Standing Committees are permanent panels with jurisdiction over broad policy areas (e.g., Agriculture, Foreign Relations) or areas of continuing legislative concern (e.g., Appropriations, Rules); (2) Select Committees are temporary or permanent panels created to consider a specific issue that lies outside the jurisdiction of other committees or that demands special attention (e.g., campaign contributions); (3) Joint Committees are panels formed by the House and Senate together, usually to investigate some common concern rather than to consider legislation, although joint committees known as Conference Committees are formed to resolve differences between House and Senate versions of a specific measure.

- Many committees divide their work among subcommittees, upon which a limited number of the committee members serve. Subcommittees are responsible for specific areas within the committee's jurisdiction and report their work on a bill to the full committee, which must approve it before reporting the bill to its branch of Congress.

- Party leaders determine the size of each committee, which average about 40 members in the House and about 18 members in the Senate, and determine the proportion of majority and minority committee members. The majority party always has more seats on a committee and one of its members chairs the committee. Each party also determines committee assignments for its members, observing rules that have been adopted to limit the number and type of committees and subcommittees upon which one member can serve.

- Each committee's chairperson has authority over its operation. He or she usually sets the committee's agenda, decides when to take or delay action, presides at most committee meetings, and controls the committee's operating budget. Subcommittee chairpersons exercise similar authority over their smaller panels, subject to approval by the committee chair.

- The work of Congressional committees begins when a bill that has been introduced to the House or Senate is referred to the committee for consideration. Most committees take up only a small percentage of the bills referred to them; those upon which the committee takes no action are said to "die in committee." The committee's first step in considering a bill is usually to ask for written comment by the executive agency that will be responsible for administering it should it become law. Next, the committee will usually hold hearings to gather opinions from outside experts and concerned citizens. If the committee decides to move forward with the bill, it will meet to frame and amend the measure through a process called markup. Finally, when the committee has voted to approve the bill, it will report the measure to its branch of Congress, usually with a written report explaining why the measure should be passed.

- Once a bill comes to the floor of the House or Senate, the committee that reported it is usually responsible for guiding it through debate and securing its passage. This can involve working out parliamentary strategies, responding to questions raised by colleagues, and building coalitions of support. Likewise, if the House and Senate pass different versions of a bill, the committees that reported each version will take the lead in working out a compromise through a conference committee.

Activity 1. Research the committees and subcommittees

Begin by viewing the Library of Congress video on Congressional Committees . Have students research the committees and subcommittees upon which their Congressional representatives serve, using library resources or the resources available through the U.S. Congress website.

- To help students find out who your Congressional representatives are, use the U.S. Congress website to search by state.

- Click on the name of each representative for a profile, including a photograph, which lists the representative's committee assignments.

- The U.S. Congress website page provides information pertaining to sponsored and cosponsored legislation, member websites, and allows users to track legislation.

- To find out which committees and subcommittees a representative serves on, use the U.S. Congress Committee Reports page .

- For an overview of Congressional committees and their jurisdictions, use the U.S. Congress Committee Reports page .

Congressional Committee Activity:

Divide the class into small groups and have each group prepare a report on one of the committees (or subcommittees) upon which one of your Congressional representatives serves, including the size of the committee, its jurisdiction, and whether your representative has a leadership post on the committee. Encourage students to include as well information about legislation currently before the committee. They can find this information using library resources or through the U.S. Congress Committee Reports page .

After students present their reports, discuss how committee assignments can affect a Congressional representative's ability to effectively represent his or her constituents.

- Do your representatives have seats on committees with jurisdiction over issues that have special importance for your state or community? If so, how might their presence on these committees help assure that Congress takes action on questions of local interest?

- Do your representatives have seats on committees with jurisdiction over important legislative activities, such as budget-making or appropriations? If so, how might their presence on these powerful committees help assure that your community's views receive careful Congressional consideration?

After exploring these questions, have students debate the extent to which a Congressional representative's committee vote may be more influential than his or her vote on the floor of the House or Senate. Which vote has more impact on legislation? In this regard, have students consider President Woodrow Wilson's observation that "Congress in session is Congress on public exhibition, whilst Congress in its committee-rooms is Congress at work."

Activity 2. How do Congressional committees reflects some of the fundamental principles of federalism?

Conclude by having students consider how the structure and function of Congressional committees reflects some of the fundamental principles of federalism. For a broad discussion of federalism, have students read The Federalist No. 39 , in which James Madison highlights the Constitution's provisions for a federal, as distinguished from a national, form of government.

Have students imagine, for example, that they are members of a Congressional committee that is considering a bill with special importance for the people of your community.

- How would they balance their responsibilities to their constituents with their responsibilities to the nation as a whole?

- To what extent is this a question each Congressional representative must answer individually?

- To what extent is it a question that the mechanisms of our government answer through the legislative process?

Related on EDSITEment

Commemorating constitution day, a day for the constitution, balancing three branches at once: our system of checks and balances.

- Developmental Psychology

Committee Assignments: Theories, Causes and Consequences

- January 2019

- Parliamentary Affairs 72(1):77-98

- 72(1):77-98

- This person is not on ResearchGate, or hasn't claimed this research yet.

- Leiden University

Discover the world's research

- 25+ million members

- 160+ million publication pages

- 2.3+ billion citations

No full-text available

To read the full-text of this research, you can request a copy directly from the authors.

- Viacheslav O. Rumiantsev

- K.M. Lisohorova

- PARLIAMENT AFF

- Asmir Hajdarevic

- Maya Kornberg

- Charlotte van Kleef

- Matthew S. Shugart

- Rebecca Eissler

- Matthew Loftis

- Nate Monroe

- David Fortunato

- Jerome Cairney

- Sergiu Gherghina

- Miguel Alquezar-Yus

- Josep Amer-Mestre

- Sergio A. Bárcena Juárez

- Mark Goodwin

- Stephen Holden Bates

- Erika García Méndez

- Christopher D. Raymond

- Jorge M. Fernandes

- Martin Ejnar Hansen

- Yusuf Tekin

- Richard L. Hall

- Gary W. Cox

- Nicholas A. Masters

- J.S. Lapinski

- Shane Martin

- Radoslaw Zubek

- Keith E. Hamm

- Kenneth A. Shepsle

- James M. Snyder

- E. Scott Adler

- John S. Lapinski

- Peter C. Ordeshook

- BRIT J POLIT SCI

- Kristin Kanthak

- Stephanie Shirley Post

- Mary Sprague

- Nikoleta Yordanova

- COMP POLIT STUD

- Gerhard Loewenberg

- ECONOMETRICA

- Duncan Black

- David W. Prince

- Recruit researchers

- Join for free

- Login Email Tip: Most researchers use their institutional email address as their ResearchGate login Password Forgot password? Keep me logged in Log in or Continue with Google Welcome back! Please log in. Email · Hint Tip: Most researchers use their institutional email address as their ResearchGate login Password Forgot password? Keep me logged in Log in or Continue with Google No account? Sign up

Committee Assignments Chart and Commentary

Twelve action committees.

There are important moments in the life of a political gathering, such as an assembly of delegates, when recourse to a smaller number of the membership is necessary. The Constitutional Convention of 1787 found the need to resort to this on twelve different occasions during their four months. Each one of these twelve committees of the Convention is an “Action Committee,” in the sense that each one helps the Convention move to the next stage of the deliberative and decision-making process.

We suggest that it is useful to distinguish between two different kinds of action committees. The first is on behalf of the deliberative process and is an effort to set down the rules or secure a breakthrough so that deliberation can continue in a productive fashion. The second is on behalf of the decision-making process itself. In other words, the action involved is not primarily focused on keeping the deliberative process alive and well, but bringing the gathering toward making some decisions from which there is little possibility of reversal.

During the months of May, June, and July, the Convention sat as a Committee of the Whole. That meant that the entire membership was involved in the give and take together on essential questionssitting as a Committee of the Whole makes it far easier to explore, alter, and prodrather than the emphasis being on the delegates having to decide, once and for all as it were, on specific articles, sections, and clauses. The decision-making stage occurs during the months of August and September where the task of filling in the details and hammering out specific compromises are delegated to members of committees selected by the entire Convention. This is where the votes of the delegates become crucial to the outcome.

Act I and Act II

Acts I and II of the Four Act Drama capture the deliberative stage of the Convention. Accordingly, it is not surprising that out of the twelve committees listed, only four occur during this earlier phase of the Convention: the Rules Committee and the three Committees of Representation, which can be collapsed into the Gerry Committee.” So we actually have only two important committees to examine in this stage of the conversation.

The three member Rules Committee, under the leadership of the Virginia legal scholar, George Wythe, laid down rules for what they considered to be a civilized conversation. Hamilton and Pinckney—later accused of being a monarchist and aristocrat respectively—joined Wythe in proposing rules aimed to foster open deliberation among the delegates. One of the more controversial recommendations was the rule of secrecy. Madison, both at the time of the Convention and later, vigorously defended this rule; he thought it encouraged the free exchange of ideas among the members so vital for the success of the deliberative process. The secrecy rule has been criticized by influential Progressive Historians of the twentieth century who portray it as evidence of an upper class and reactionary disposition at the Convention to undermine the democratic spirit of the Revolution of 1776.

The membership of the Gerry Committee provides a crucial insight into the mood of the Convention at the end of June and the beginning of July. At the end of Act One, the wholly national Virginia Plan, albeit slightly amended, was on the table for further consideration. But the opposition, led by Sherman and Ellsworth of Connecticut, insisted on a compromise between the wholly national Virginia Plan and the wholly federal New Jersey Plan introduced by Paterson of New Jersey. Or if no compromise were possible, then they favored the adoption of the federal New Jersey Plan.

The last two weeks of June marks the low point of the Convention. Conversation and deliberation had given way to threats of secession, lines were drawn in the sand, and frustration ran high. At the end of June, Ellsworth tried one more time to break the deadlock with his partly national-partly federal proposal. This time it worked, and the more pragmatic delegates decided to create a committee to move the deliberative process forward. The Convention, still sitting as a committee of the Whole, on July 2 elected 11 members—one from each State present—to seek a partly national-partly federal compromise.

But the Gerry Committee could not have made that recommendation, and made it stick, unless the members of the committee, and thus the Convention itself, were so inclined. Davie from North Carolina announced his support for the partly national and partly federal compromise in late June, as did Franklin, Luther Martin, Paterson, Sherman-Ellsworth, and Yates. The Convention could have chosen Madison rather than Mason from Virginia, Wilson rather than Franklin from Pennsylvania, and King rather than Gerry from Massachusetts, but the delegates did not. The 11 members chosen by the entire body of delegates were selected because of their inclination to seek a compromise; the members of the Gerry Committee were those representatives from each state that could be relied upon to propose and secure the passage of the Connecticut Compromise on July 16.

Act III and Act IV

8 of the 12 committees met during Act Three and Act Four, and four of these committees were crucial in the framing of the Constitution: The Committee of Detail, the Committee of Slave Trade, the Brearly Committee, and the Committee of Style. Of the other four, the Committee of Trade was actually a companion to the Slave Trade Committee and worked out the final North South compromise on navigation issues. Two other committees dealt with existing state debts and state commitments under the new Constitution. The eighth committee on “economy, frugality, and manufactures” was created during the last week of the Convention and never filed a report.

The 5 members of the Committee of Detail Rutledge (chair), Ellsworth, Gorham, Randolph, and Wilson—were chosen by the entire Convention to turn the various proposals and recommendations made in Act One and Act Two into the first draft of the Constitution. They met for nearly two weeks and produced the Committee of Detail Report that became the focus of conversation of the entire Convention during August. It is beyond the scope of this commentary to speculate on the twists and turns that must have taken place among the delegates over that period. Or even why these five were chosen. Suffice it to note, that Rutledge managed to secure a strong pro-slave trade provision, Randolph, by his subsequent actions, must have been insistent upon the money bills provision of the Connecticut Compromise, Ellsworth was there to secure the structural importance and reserved powers of the states, and Wilson and King probably urged the inclusion of as much high-toned government as possible in the elevation of the Senate to a central player. Interestingly, the Committee agreed that the powers of Congress be enumerated—this is where the interstate and international commerce clause and the necessary and proper clause make their appearance—but the structure and powers of the Executive branch are still in an inconclusive situation.

I suggest that once the Convention shifted from an emphasis on committees of deliberation to an emphasis on committees of decision-making, then the work of the committees takes on a privileged position. Accordingly, the delegates reviewing and debating the work of the committees are probably likely to challenge the recommendations of the committee only when something big is at stake. Thus, we should pay close attention to important concerns generated by the Committee of Detail Report.

There were two major concerns that attracted the attention of the delegates. The provision in the Report that banned Congress from ever regulating (international commerce just granted in) the slave trade generated considerable division near the end of August. The Slave Trade Committee, also known as the Livingston Committee, was created to find a “middle ground” between the Committee of Detail Report that guaranteed the permanent existence of the international slave trade and those delegates who wished to limit the slave trade in the foreseeable future. This committee recommended that Congress be released from this restriction in 1800. Anti-slave trade delegates Madison, L. Martin, King, and Dickinson were members of the Committee of the 11 elected by the entire Convention. The final decision of the Convention was to release the Congressional prohibition in 1808.

The delegates were also concerned about “left overs,” especially the Presidency. The Brearly Committee that included Madison, King, G. Morris, Dickinson and Sherman settled on the Electoral College as the compromise mode of electing the President. And in the process they elevated the Executive to a position of importance in the separation of powers system.

The Convention, in mid-September, also elected five members to the Committee of Style: Hamilton, Johnson (Chairman), King, Madison, and G. Morris. With the possible exception of Johnson, the members were very warm supporters of the original Virginia Plan that proposed a wholly national remedy for the ills of republicanism and defended time and again any possible move for a higher toned government.

The mood of the Convention had shifted once again, but this time, in September, it had shifted back toward the supporters of the original Virginia Plan. This is revealed by the election of Madison, King, and G. Morris to the Brearly Committee and the Committee of Style. It’s almost like the delegates at the Convention let the initial promoters of the national movement have the last say after the Sherman opposition had their say in July and August.

The Committees

- Rules Committee (created May 25, delivered report on May 28) 3 members

- First Committee of Representation (created July 2, also known as the Gerry Committee”) 11 members

- Second Committee of Representation (created July 6, also known as “the Committee of Five”) 5 members

- Third Committee of Representation (created July 9) 11 members

- Committee of Detail (created July 24, report delivered on August 6 and discussed throughout August) 5 members

- Committee of Assumption of State Debts (created August 18) 11 members

- Committee of Slave Trade (created Aug. 22, also known as “the Livingston Committee,” delivered report on Aug. 24) 11 members

- Committee of Trade (created August 25) 11 members

- Committee of State Commitments (created August 29) 11 members

- Committee of Leftovers (created August 31, also known as “the Brearly Committee”) 11 members

- Committee of Style (created Sept. 10, report delivered on Sept. 12 and discussed during the remainder of the Convention) 5 members

- Committee of Economy, Frugality and Manufactures (created September 13) 5 members

Committee Assignments by State and Delegate

| Name | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 |

| , NH (1) | ♦ | |||||||||||

| , NH (3) | ♦ | ♦ | ♦ | |||||||||

| , MA (1) | ‡ | |||||||||||

| , MA (4) | ♦ | ♦ | ♦ | ♦ | ||||||||

| , MA (6) | ♦ | ‡ | ♦ | ♦ | ♦ | ♦ | ||||||

| , MA (0) | ||||||||||||

| , CT (1) | § | ♦ | ||||||||||

| , CT (4) | ♦ | ♦ | ‡ | ♦ | ||||||||

| , CT (5) | § | ♦ | ♦ | ‡ | ♦ | |||||||

| , NY (2) | ♦ | ♦ | ||||||||||

| , NY (0) | ||||||||||||

| , NY (2) | ♦ | ♦ | ||||||||||

| , PA (2) | ♦ | ♦ | ||||||||||

| , PA (1) | ♦ | |||||||||||

| , PA (2) | ♦ | ♦ | ||||||||||

| , PA (0) | ||||||||||||

| , PA (0) | ||||||||||||

| , PA (4) | ‡ | ♦ | ♦ | ♦ | ||||||||

| , PA (0) | ||||||||||||

| , PA (2) | ♦ | ♦ | ||||||||||

| , NJ (2) | ♦ | ‡ | ||||||||||

| , NJ (1) | ♦ | |||||||||||

| , NJ (0) | ||||||||||||

| , NJ (3) | ‡ | ‡ | ♦ | |||||||||

| , NJ (1) | ♦ | |||||||||||

| , DE (0) | ||||||||||||

| , DE (1) | ♦ | |||||||||||

| , DE (0) | ||||||||||||

| , DE (4) | ♦ | ♦ | ♦ | ♦ | ||||||||

| , DE (2) | ♦ | ♦ | ||||||||||

| , MD (3) | ♦ | ♦ | ♦ | |||||||||

| , MD (0) | ||||||||||||

| , MD (2) | ♦ | ♦ | ||||||||||

| , MD (1) | ♦ | |||||||||||

| , MD (0) | ||||||||||||

| , VA (0) | ||||||||||||

| , VA (4) | ♦ | ♦ | ♦ | ♦ | ||||||||

| , VA (4) | ♦ | ♦ | ♦ | ‡ | ||||||||

| , VA (0) | ||||||||||||

| , VA (3) | ♦ | ♦ | ♦ | |||||||||

| , VA (0) | ||||||||||||

| , VA (1) | ‡ | |||||||||||

| , NC (0) | ||||||||||||

| , NC (1) | ♦ | |||||||||||

| , NC (0) | ||||||||||||

| , NC (0) | ||||||||||||

| , NC (5) | ♦ | ♦ | ♦ | ♦ | ♦ | |||||||

| , SC (2) | ♦ | ♦ | ||||||||||

| , SC (1) | ♦ | |||||||||||

| , SC (2) | ♦ | ♦ | ||||||||||

| , SC (5) | ♦ | ♦ | ♦ | ‡ | ‡ | |||||||

| , GA (4) | ♦ | ♦ | ♦ | ♦ | ||||||||

| , GA (1) | ♦ | |||||||||||

| , GA (1) | ♦ | |||||||||||

| , GA (0) |

♦ — Member of Committee ‡ — Chairman of Committee § — Ellsworth was “indisposed;” Sherman substituted.

Receive resources and noteworthy updates.

- Election 2024

- Entertainment

- Newsletters

- Photography

- Personal Finance

- AP Investigations

- AP Buyline Personal Finance

- AP Buyline Shopping

- Press Releases

- Israel-Hamas War

- Russia-Ukraine War

- Global elections

- Asia Pacific

- Latin America

- Middle East

- Election Results

- Delegate Tracker

- AP & Elections

- Auto Racing

- 2024 Paris Olympic Games

- Movie reviews

- Book reviews

- Personal finance

- Financial Markets

- Business Highlights

- Financial wellness

- Artificial Intelligence

- Social Media

Speaker Johnson appoints two Trump allies to a committee that handles classified intelligence

Speaker of the House Mike Johnson, R-La., and other Republican leaders meet with reporters to condemn former President Donald Trump’s guilty conviction in a New York court last week, at the Capitol in Washington, Tuesday, June 4, 2024. Johnson also called President Joe Biden the worst president in American history. (AP Photo/J. Scott Applewhite)

- Copy Link copied

WASHINGTON (AP) — House Speaker Mike Johnson on Wednesday appointed two far-right Republicans to the powerful House Intelligence Committee, positioning two close allies of Donald Trump who worked to overturn the 2020 presidential election on a panel that receives sensitive classified briefings and oversees the work of America’s spy agencies.

The appointments of GOP Reps. Scott Perry of Pennsylvania and Ronny Jackson of Texas to the House Intelligence Committee were announced on the House floor Wednesday. Johnson, a hardline conservative from Louisiana who has aligned himself with Trump, was replacing spots on the committee that opened up after the resignations of Republican Reps. Mike Gallagher of Wisconsin and Chris Stewart of Utah.

Committee spots have typically been given to lawmakers with backgrounds in national security and who have gained respect across the aisle. But the replacements with two close Trump allies comes as Johnson has signaled his willingness to use the full force of the House to aid Trump’s bid to reclaim the Oval Office. It also hands the hard-right faction of the House two coveted spots on a committee that handles the nation’s secrets and holds tremendous influence over the direction of foreign policy.

Trump has long displayed adversarial and flippant views of the U.S. intelligence community, flouted safeguards over classified information and directly berated law enforcement agencies like the FBI. The former president faces 37 felony counts for improperly storing in his Florida estate sensitive documents on nuclear capabilities, repeatedly enlisting aides and lawyers to help him hide records demanded by investigators and cavalierly showing off a Pentagon “plan of attack” and classified map.

Johnson did not release a statement on his picks for the committee.

Perry, who formerly chaired the ultraconservative House Freedom Caucus, was ordered by a federal judge last year to turn over more than 1,600 texts and emails to FBI agents investigating efforts to keep Trump in office after his 2020 election loss and illegally block the transfer of power to Democrat Joe Biden.

Perry’s personal cellphone was also seized by federal authorities who have explored his role in helping install an acting attorney general who would be receptive to Trump’s false claims of election fraud.

Perry and other conservatives have also pushed Congress to curtail a key U.S. government surveillance tool. They want to restrict the FBI’s ability to use the program to search for Americans’ data.

“I look forward to providing not only a fresh perspective, but conducting actual oversight — not blind obedience to some facets of our Intel Community that all too often abuse their powers, resources, and authority to spy on the American People,” Perry said in a statement.

Jackson, who was elected to the House in 2020, was formerly a top White House physician under former presidents Barack Obama and Trump. Known for his over-the-top pronouncements about Trump’s health, Jackson was nominated by Trump to be the secretary of Veterans Affairs.

He withdrew his nomination amid allegations of professional misconduct. An internal investigation at the Department of Defense later concluded that Jackson made “sexual and denigrating” comments about a female subordinate, violated the policy on drinking alcohol on a presidential trip and took prescription-strength sleeping medication that prompted worries from his colleagues about his ability to provide proper medical care.

Jackson has denied those allegations and described them as politically motivated.

The House committee that investigated the Jan. 6 insurrection at the Capitol also requested testimony from Jackson as it looked into lawmakers’ meetings at the White House, direct conversations with Trump as he sought to challenge his election loss and the planning and coordination of rallies. Jackson declined to testify.

The presence of Jackson and Perry on the committee could damage the trust between the president and the committee in handling classified information, said Ira Goldman, a former Republican congressional aide who worked as a counsel to the intelligence committee in the 1970s and 1980s.

He said, “You’re giving members seats on the committee when, based on the public record, they couldn’t get a security clearance if they came through any other door.”

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Committees help to organize the most important work of Congress — considering, shaping, and passing laws to govern the nation. 8,000 or so bills go to committee annually. ... Committee Assignments. After each congressional election, political parties assign newly elected Representatives and Senators to standing committees. They consider a ...

Party conferences appoint a "committee on committees" or a "steering committee" to make committee assignments, considering such qualifications as seniority, areas of expertise, and relevance of committee jurisdiction to a senator's state. In both conferences, the floor leader has authority to make some committee assignments, which can ...

Committee reports are documents produced by Senate committees that address investigations, committee business, and legislative or policy measures. There are different types of committee reports: Reports that accompany a legislative measure when reported to the full chamber. Oversight or investigative findings.

About the Committee System. Committees are essential to the effective operation of the Senate. Through investigations and hearings, committees gather information on national and international problems within their jurisdiction in order to draft, consider, and recommend legislation to the full membership of the Senate.

Committee Assignments1 Committee assignments often determine the character of a Member's career. They are also important to the party leaders who organize the chamber and shape the composition of the committees. House rules identify some procedures for making committee assignments;

The rules of the Senate divide its standing and other committees into categories for purposes of assigning all Senators to committees. In particular, Rule XXV, paragraphs 2 and 3 establish the categories of committees, popularly called the "A," "B," and "C" committees. The "A" and "B" categories, are as follows:2.

Much of the important work in Congress is accomplished through committees. The fate of legislation—which bills will make it to the floor of the House and Senate—is determined in committees. Members seek committee assignments considering their desire to influence policy, exert influence, and get reelected.

Committee assignments are the behavioural manifestation of legislative organisation, a process by which 'resources and parliamentary rights [are assigned] to individual legislators or groups of legislators' ( Krehbiel, 1992, p. 2). Our specific focus is on understanding which members sit in which committees, why, and with what consequences.

Committees provide Congress with a double-edged sword. They help Congress do its job, but they also threaten to subvert the legislative process, dividing Congress into many subunits, each of which advance a narrow, special interest rather than the common good. If they are not held accountable to the whole Congress, through rules that allow party leaders to influence committees and allow ...

committees, why, and with what consequences. Prepared for Parliamentary Affairs 1 ... assignments offers an important stepping stone to better understand decision-making processes and power relations within modern legislatures. Although parliamentary parties are, in many legislatures, the dominating organisational structures (Damgaard, 1995; ...