More From Forbes

A guide to writing the covid-19 essay for the common app.

- Share to Facebook

- Share to Twitter

- Share to Linkedin

Students can use the Common App's new Covid-19 essay to expand on their experiences during the ... [+] pandemic.

Covid-19 has heavily impacted students applying to colleges in this application cycle. High schools have gone virtual, extracurricular activities have been canceled and family situations might have changed. Having recognized this, the Common App added a new optional 250-word essay that will give universities a chance to understand the atypical high school experience students have had. The prompt will be:

“Community disruptions such as COVID-19 and natural disasters can have deep and long-lasting impacts. If you need it, this space is yours to describe those impacts. Colleges care about the effects on your health and well-being, safety, family circumstances, future plans, and education, including access to reliable technology and quiet study spaces.”

Should I Write About The Coronavirus Pandemic?

For many high schoolers, the pandemic will have had a lasting impact on their education and everyday lives. Some students might have had a negative experience: a parent laid off or furloughed, limited access to online classes or a family member (or the student) having fallen ill from the virus.

Other students might have had the opposite experience. Even though they might have undergone a few negative events or stressful times, they might have learned something new, started a new project or gained a new perspective that changed their future major or career choice.

If you fit into either of these categories, writing the optional essay might be a good idea.

Remember, the admission officers have also been dealing with the crisis and understand the situation students are going through. They are well aware that the AP exams were administered remotely, SAT/ACT test dates were canceled and numerous schools transitioned to a virtual learning model. There is likely no need to reiterate this in an essay unless there was a direct impact on an aspect of your application.

Godzilla Minus One Dethroned In Netflix s Top 10 List By A New Movie

Why christina ricci is giving up ownership of wednesday addams, wwe smackdown results winners and grades on june 7 2024, what not to write .

As with every college essay you write, it is important to think about the tone and word choice. You want to remain sensitive to the plight of other students during this global crisis. While every student has likely been affected by the pandemic, the level of impact will vary greatly. For some, classes moved online, but life remained more or less the same. For these types of students, it might not be a strategic move to write about the coronavirus if you don’t have anything meaningful, unique or personal to say. If you only have a limited time to impress the admission officer, you want to ensure that each word is strategically thought out and showcases a new aspect of your personality.

Using this space as a time to complain about how you weren’t able to go to the beach, see friends or eat out could be seen as you flaunting your privilege. Careful consideration of how you portray yourself will be key.

Nearly every student has had an activity or event canceled. It likely won’t be a good use of your word count lamenting on the missed opportunities. Instead, it would be more illuminating to talk about how you remained flexible and pivoted to other learning opportunities.

How To Write The Covid-19 Essay

The Covid-19 essay was introduced so universities could gain a better understanding of how their applicants have had their lives and education disrupted due to the pandemic. You’ll want to give the admission officers context to understand your experiences better.

Here are some examples of how to write this optional essay.

- Outline any extenuating circumstances related to Covid-19. Some students might find themselves crammed in a small apartment or home with their entire family. This disruptive environment might have made it difficult for the student to concentrate on their classes. Some students might be required to care for younger siblings during the day. In many areas of the country, lack of access to high-speed internet or smart devices meant that students couldn’t participate in online learning. Now is the time to share those details.

- Include the impact. Ultimately, this essay is about you. Things likely happened to family members, friends or your community, but you need to show how it altered your life specifically.

- Provide specific details. Give the admission officers a peek into your everyday life. Including specific details can help make your story come alive. For example, don’t just say that it was hard dealing with the emotional trauma of seeing friends and family fall ill. Instead, be specific and talk about how your friend was diagnosed with Covid-19 and had to be hospitalized. Seeing the long-term effects caused you to take the pandemic much more seriously and moved you to take action. Perhaps you were inspired to start a nonprofit that makes masks or to help your neighbors through this difficult time.

Covid-19 Essay for School Counselors

It’s not just students who will get to submit an additional statement regarding the impact of the coronavirus: Counselors will also get a chance to submit a 500-word essay. Their prompt will be:

Your school may have made adjustments due to community disruptions such as COVID–19 or natural disasters. If you have not already addressed those changes in your uploaded school profile or elsewhere, you can elaborate here. Colleges are especially interested in understanding changes to:

- Grading scales and policies

- Graduation requirements

- Instructional methods

- Schedules and course offerings

- Testing requirements

- Your academic calendar

- Other extenuating circumstances

The counselor’s response will populate to all the applications of students from the high school. They will cover any school or district policies that have impacted students. No specific student details will be included.

Students can ask to see a copy of this statement so they know what information has already been shared with colleges. For example, if the school states that classes went virtual starting in March, you don’t need to repeat that in your Covid-19 essay.

Should I Write About The Covid-19 In My Personal Statement?

The world before Covid-19 might seem like a distant memory, but you did spend more than 15 years engaging in a multitude of meaningful activities and developing your passions. It’s important to define yourself from more than just the coronavirus crisis. You likely will want to spend the personal statement distinguishing yourself from other applicants. With the Covid-19 optional essay and the additional information section, you should have plenty of space to talk about how you’ve changed—for better or for worse—due to the pandemic. Use the personal statement to talk about who you were before quarantining.

- Editorial Standards

- Reprints & Permissions

45,000+ students realised their study abroad dream with us. Take the first step today

Meet top uk universities from the comfort of your home, here’s your new year gift, one app for all your, study abroad needs, start your journey, track your progress, grow with the community and so much more.

Verification Code

An OTP has been sent to your registered mobile no. Please verify

Thanks for your comment !

Our team will review it before it's shown to our readers.

- School Education /

Essay On Covid-19: 100, 200 and 300 Words

- Updated on

- Apr 30, 2024

COVID-19, also known as the Coronavirus, is a global pandemic that has affected people all around the world. It first emerged in a lab in Wuhan, China, in late 2019 and quickly spread to countries around the world. This virus was reportedly caused by SARS-CoV-2. Since then, it has spread rapidly to many countries, causing widespread illness and impacting our lives in numerous ways. This blog talks about the details of this virus and also drafts an essay on COVID-19 in 100, 200 and 300 words for students and professionals.

Table of Contents

- 1 Essay On COVID-19 in English 100 Words

- 2 Essay On COVID-19 in 200 Words

- 3 Essay On COVID-19 in 300 Words

- 4 Short Essay on Covid-19

Essay On COVID-19 in English 100 Words

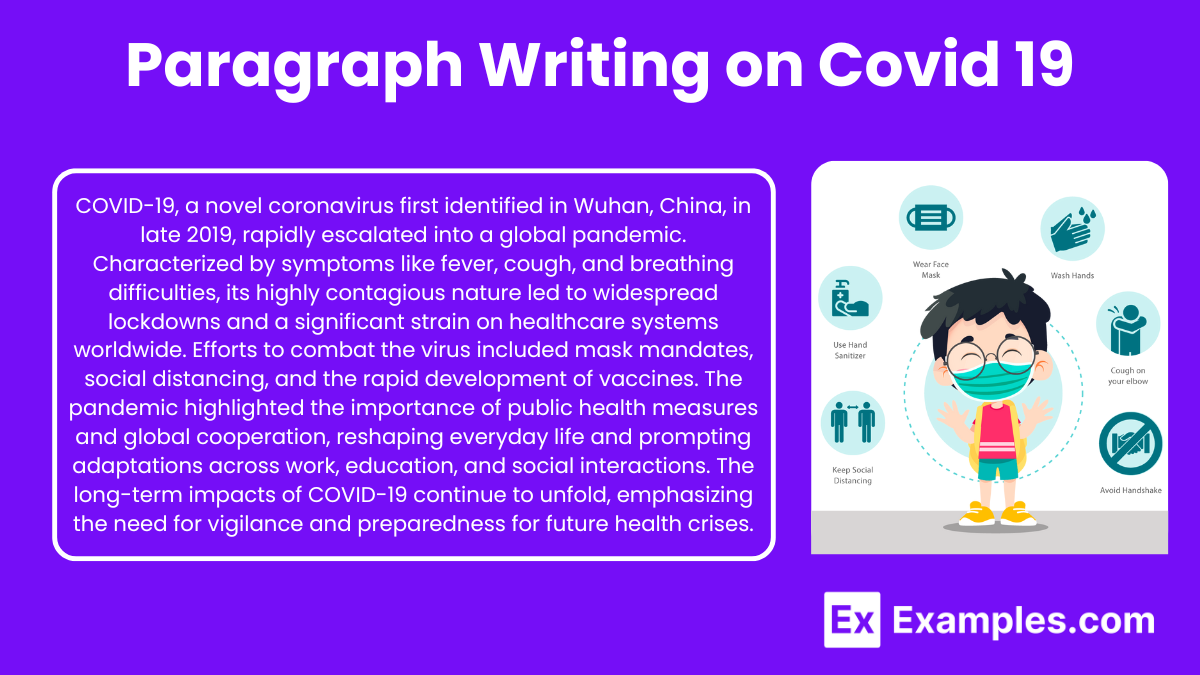

COVID-19, also known as the coronavirus, is a global pandemic. It started in late 2019 and has affected people all around the world. The virus spreads very quickly through someone’s sneeze and respiratory issues.

COVID-19 has had a significant impact on our lives, with lockdowns, travel restrictions, and changes in daily routines. To prevent the spread of COVID-19, we should wear masks, practice social distancing, and wash our hands frequently.

People should follow social distancing and other safety guidelines and also learn the tricks to be safe stay healthy and work the whole challenging time.

Also Read: National Safe Motherhood Day 2023

Essay On COVID-19 in 200 Words

COVID-19 also known as coronavirus, became a global health crisis in early 2020 and impacted mankind around the world. This virus is said to have originated in Wuhan, China in late 2019. It belongs to the coronavirus family and causes flu-like symptoms. It impacted the healthcare systems, economies and the daily lives of people all over the world.

The most crucial aspect of COVID-19 is its highly spreadable nature. It is a communicable disease that spreads through various means such as coughs from infected persons, sneezes and communication. Due to its easy transmission leading to its outbreaks, there were many measures taken by the government from all over the world such as Lockdowns, Social Distancing, and wearing masks.

There are many changes throughout the economic systems, and also in daily routines. Other measures such as schools opting for Online schooling, Remote work options available and restrictions on travel throughout the country and internationally. Subsequently, to cure and top its outbreak, the government started its vaccine campaigns, and other preventive measures.

In conclusion, COVID-19 tested the patience and resilience of the mankind. This pandemic has taught people the importance of patience, effort and humbleness.

Also Read : Essay on My Best Friend

Essay On COVID-19 in 300 Words

COVID-19, also known as the coronavirus, is a serious and contagious disease that has affected people worldwide. It was first discovered in late 2019 in Cina and then got spread in the whole world. It had a major impact on people’s life, their school, work and daily lives.

COVID-19 is primarily transmitted from person to person through respiratory droplets produced and through sneezes, and coughs of an infected person. It can spread to thousands of people because of its highly contagious nature. To cure the widespread of this virus, there are thousands of steps taken by the people and the government.

Wearing masks is one of the essential precautions to prevent the virus from spreading. Social distancing is another vital practice, which involves maintaining a safe distance from others to minimize close contact.

Very frequent handwashing is also very important to stop the spread of this virus. Proper hand hygiene can help remove any potential virus particles from our hands, reducing the risk of infection.

In conclusion, the Coronavirus has changed people’s perspective on living. It has also changed people’s way of interacting and how to live. To deal with this virus, it is very important to follow the important guidelines such as masks, social distancing and techniques to wash your hands. Getting vaccinated is also very important to go back to normal life and cure this virus completely.

Also Read: Essay on Abortion in English in 650 Words

Short Essay on Covid-19

Please find below a sample of a short essay on Covid-19 for school students:

Also Read: Essay on Women’s Day in 200 and 500 words

to write an essay on COVID-19, understand your word limit and make sure to cover all the stages and symptoms of this disease. You need to highlight all the challenges and impacts of COVID-19. Do not forget to conclude your essay with positive precautionary measures.

Writing an essay on COVID-19 in 200 words requires you to cover all the challenges, impacts and precautions of this disease. You don’t need to describe all of these factors in brief, but make sure to add as many options as your word limit allows.

The full form for COVID-19 is Corona Virus Disease of 2019.

Related Reads

Hence, we hope that this blog has assisted you in comprehending with an essay on COVID-19. For more information on such interesting topics, visit our essay writing page and follow Leverage Edu.

Simran Popli

An avid writer and a creative person. With an experience of 1.5 years content writing, Simran has worked with different areas. From medical to working in a marketing agency with different clients to Ed-tech company, the journey has been diverse. Creative, vivacious and patient are the words that describe her personality.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Contact no. *

Connect With Us

45,000+ students realised their study abroad dream with us. take the first step today..

Resend OTP in

Need help with?

Study abroad.

UK, Canada, US & More

IELTS, GRE, GMAT & More

Scholarship, Loans & Forex

Country Preference

New Zealand

Which English test are you planning to take?

Which academic test are you planning to take.

Not Sure yet

When are you planning to take the exam?

Already booked my exam slot

Within 2 Months

Want to learn about the test

Which Degree do you wish to pursue?

When do you want to start studying abroad.

January 2024

September 2024

What is your budget to study abroad?

How would you describe this article ?

Please rate this article

We would like to hear more.

Have something on your mind?

Make your study abroad dream a reality in January 2022 with

India's Biggest Virtual University Fair

Essex Direct Admission Day

Why attend .

Don't Miss Out

Writing about COVID-19 in a college admission essay

by: Venkates Swaminathan | Updated: September 14, 2020

Print article

For students applying to college using the CommonApp, there are several different places where students and counselors can address the pandemic’s impact. The different sections have differing goals. You must understand how to use each section for its appropriate use.

The CommonApp COVID-19 question

First, the CommonApp this year has an additional question specifically about COVID-19 :

Community disruptions such as COVID-19 and natural disasters can have deep and long-lasting impacts. If you need it, this space is yours to describe those impacts. Colleges care about the effects on your health and well-being, safety, family circumstances, future plans, and education, including access to reliable technology and quiet study spaces. Please use this space to describe how these events have impacted you.

This question seeks to understand the adversity that students may have had to face due to the pandemic, the move to online education, or the shelter-in-place rules. You don’t have to answer this question if the impact on you wasn’t particularly severe. Some examples of things students should discuss include:

- The student or a family member had COVID-19 or suffered other illnesses due to confinement during the pandemic.

- The candidate had to deal with personal or family issues, such as abusive living situations or other safety concerns

- The student suffered from a lack of internet access and other online learning challenges.

- Students who dealt with problems registering for or taking standardized tests and AP exams.

Jeff Schiffman of the Tulane University admissions office has a blog about this section. He recommends students ask themselves several questions as they go about answering this section:

- Are my experiences different from others’?

- Are there noticeable changes on my transcript?

- Am I aware of my privilege?

- Am I specific? Am I explaining rather than complaining?

- Is this information being included elsewhere on my application?

If you do answer this section, be brief and to-the-point.

Counselor recommendations and school profiles

Second, counselors will, in their counselor forms and school profiles on the CommonApp, address how the school handled the pandemic and how it might have affected students, specifically as it relates to:

- Grading scales and policies

- Graduation requirements

- Instructional methods

- Schedules and course offerings

- Testing requirements

- Your academic calendar

- Other extenuating circumstances

Students don’t have to mention these matters in their application unless something unusual happened.

Writing about COVID-19 in your main essay

Write about your experiences during the pandemic in your main college essay if your experience is personal, relevant, and the most important thing to discuss in your college admission essay. That you had to stay home and study online isn’t sufficient, as millions of other students faced the same situation. But sometimes, it can be appropriate and helpful to write about something related to the pandemic in your essay. For example:

- One student developed a website for a local comic book store. The store might not have survived without the ability for people to order comic books online. The student had a long-standing relationship with the store, and it was an institution that created a community for students who otherwise felt left out.

- One student started a YouTube channel to help other students with academic subjects he was very familiar with and began tutoring others.

- Some students used their extra time that was the result of the stay-at-home orders to take online courses pursuing topics they are genuinely interested in or developing new interests, like a foreign language or music.

Experiences like this can be good topics for the CommonApp essay as long as they reflect something genuinely important about the student. For many students whose lives have been shaped by this pandemic, it can be a critical part of their college application.

Want more? Read 6 ways to improve a college essay , What the &%$! should I write about in my college essay , and Just how important is a college admissions essay? .

Homes Nearby

Homes for rent and sale near schools

How our schools are (and aren't) addressing race

The truth about homework in America

What should I write my college essay about?

What the #%@!& should I write about in my college essay?

Yes! Sign me up for updates relevant to my child's grade.

Please enter a valid email address

Thank you for signing up!

Server Issue: Please try again later. Sorry for the inconvenience

- +44 (0) 207 391 9032

Recent Posts

- Everything You Should Know About Academic Writing: Types, Importance, and Structure

Concise Writing: Tips, Importance, and Exercises for a Clear Writing Style

- How to Write a PhD Thesis: A Step-by-Step Guide for Success

- How to Use AI in Essay Writing: Tips, Tools, and FAQs

- Copy Editing Vs Proofreading: What’s The Difference?

- How Much Does It Cost To Write A Thesis? Get Complete Process & Tips

- How Much Do Proofreading Services Cost in 2024? Per Word and Hourly Rates With Charts

- Academic Editing: What It Is and Why It Matters

- How to Identify Research Gaps

- How to Use AI to Prepare for Exams

- Academic News

- Custom Essays

- Dissertation Writing

- Essay Marking

- Essay Writing

- Essay Writing Companies

- Model Essays

- Model Exam Answers

- Oxbridge Essays Updates

- PhD Writing

- Significant Academics

- Student News

- Study Skills

- University Applications

- University Essays

- University Life

- Writing Tips

How to write an essay on coronavirus (COVID-19)

(Last updated: 10 November 2021)

Since 2006, Oxbridge Essays has been the UK’s leading paid essay-writing and dissertation service

We have helped 10,000s of undergraduate, Masters and PhD students to maximise their grades in essays, dissertations, model-exam answers, applications and other materials. If you would like a free chat about your project with one of our UK staff, then please just reach out on one of the methods below.

With the coronavirus pandemic affecting every aspect of our lives for the last 18 months, it is no surprise that it has become a common topic in academic assignments. Writing a COVID-19 essay can be challenging, whether you're studying biology, philosophy, or any course in between.

Your first question might be, how would an essay about a pandemic be any different from a typical academic essay? Well, the answer is that in many ways it is largely similar. The key difference, however, is that this pandemic is much more current than usual academic topics. That means that it may be difficult to rely on past research to demonstrate your argument! As a result, COVID-19 essay writing needs to balance theories of past scholars with very current data (that is constantly changing).

In this post, we are going to give you our top tips on how to write a coronavirus academic essay, so that you are able to approach your writing with confidence and produce a great piece of work.

1. Do background reading

Critical reading is an essential component for any essay, but the question is – what should you be reading for a coronavirus essay? It might seem like a silly question, but the choices that you make during the reading process may determine how well you actually do on the paper. Therefore, we recommend the following steps.

First, read (and re-read) the assignment prompt that you have been given by the instructor. If you write an excellent essay, but it is off topic, you’ll likely be marked down. Make notes on the words that explain what is being asked of you – perhaps the essay asks you to “analyse”, “describe”, “list”, or “evaluate”. Make sure that these same words actually appear in your paper.

Second, look for specific things you have been instructed to do. This might include using themes from your textbook or incorporating assigned readings. Make a note of these things and read them first. Remember to take good notes while you read.

Once you have done your course readings, the question then becomes: what types of external readings are you going to need? Typically, at this point, you are going to be left with newspapers/websites, and a few scholarly articles (books on coronavirus might not be readily available at this stage, but could still be useful!). If it is a research essay, you are likely going to need to rely on a variety of sources as you work through this assignment. This might seem different than other academic writing where you would typically focus on only peer-reviewed articles or books. With coronavirus essays, there is a need for a more diverse set of sources, including;

Newspaper articles and websites

Just like with academic articles, not all newspaper articles and/or websites are created equal. Further, there are likely to be a variety of different statistics released, as the way that countries calculate coronavirus cases, deaths, and other components of the virus are not always the same.

Try to pick sources that are reputable. This might be reports done by key governmental organisations or even the World Health Organisation. If you are reading through an article and can identify obvious areas of bias, you may need to find alternate readings for your paper.

Academic articles

You may be surprised to discover the variety of articles published so far on COVID-19 - a lot can be achieved over multiple lockdowns! The research that has been done has been fairly extensive, covering a broad range of topics. Therefore, when preparing to write your academic essay, make sure to check the literature frequently as new publications are being released all the time.

If you do a search and you cannot find anything on the coronavirus specifically, you will have to widen your search. Think about the topic more widely. Are there theories that you have learned about in your classes that you can link to academic articles? Surely the answer must be yes! Just because there is limited research on this topic does not mean that you should avoid academic articles all together. Relying solely on websites or newspapers can lead you to a biased piece of writing, which usually is not what an academic essay is all about.

2. Plan your essay

Brainstorming.

Taking the time to brainstorm out your ideas can be the first step in a super successful essay. Brainstorming does not have to take a lot of time, and can be done in about 20 minutes if you have already done some background reading on the topic.

First, figure out how many points you need to identify. Each point is likely to equate to one paragraph of your paper, so if you are writing a 1500-word essay (and you use 300 words for the introduction and conclusion) you will be left with 1200 words, which means you will need between 5-6 paragraphs (and 5-6 points).

Start with a blank piece of paper. In the middle of the paper write the question or statement that you are trying to answer. From there, draw 5 or 6 lines out from the centre. At the end of each of these lines will be a point you want to address in your essay. From here, write down any additional ideas that you have.

It might look messy, but that’s OK! This is just the first step in the process and an opportunity for you to get your ideas down on paper. From this messiness, you can easily start to form a logical and linear outline that will soon become the template for your essay.

Creating an outline

Once you have a completed brainstorm, the next step is to put your ideas into a logical format The first step in this process is usually to write out a rough draft of the argument you are attempting to make. In doing this, you are then able to see how your subsequent paragraphs are addressing this topic (and if they are not addressing the topic, now is the time to change this!).

Once you have a position/argument/thesis statement, create space for your body paragraphs, but numbering each section. Then, write a rough draft of the topic sentence that you think will fit well in that section. Once you have done this, pull up the coronavirus articles, data, and other reports that you have read. Determine where each will fit best in your paper (and exclude the ones that do not fit well). Put a citation of the document in each paragraph section (this will make it easier to construct your reference list at the end).

Once every paragraph is organised, double check to make sure they are all still on track to address your main thesis. At this point you are ready to write an excellent and well-organised COVID-19 essay!

3. Structure your paragraphs

When structuring an academic essay on COVID-19, there will be a need to balance the news, evidence from academic articles, and course theory. This adds an extra layer of complexity because there are just so many things to juggle.

One strategy that can be helpful is to structure all your paragraphs in the same way. Now, you might be thinking, how boring! In reality, it is likely that the reader will appreciate the fact that you have carefully thought out your process and how you are going to approach this essay.

How to design your essay paragraphs

- Create a topic sentence. A topic sentence is a sentence that presents the main idea for the paragraph. Usually it links back to your thesis, argument, or position.

- Start to introduce your evidence. Use the next sentence in your introduction as a bridge between the topic sentence and the evidence/data you are going to present.

- Add evidence. Take 2-4 sentences to give the reader some good information that supports your topic sentence. This can be statistics, details from an empirical study, information from a news article, or some other form of information.

- Give some critical thought. It is essential to make a connection for the reader between your evidence and your topic sentence. Tell the reader why the information you have presented is important.

- Provide a concluding sentence. Make sure you wrap up your argument or transition to the next one.

4. Write your essay

Keep it academic.

There is a lot of information available about the coronavirus, but because much of it is coming from newspaper articles, the evidence that you might use for your paper can be skewed. In order to keep your paper academic, it is best to maintain a professional and academic style.

Present statistics from reputable sources (like the World Health Organisation), rather than those that have been selected by third parties. Furthermore, if you are writing a COVID-19 essay that is about a specific region (e.g. the United Kingdom), make sure that your statistics and evidence also come from this region.

Use up-to-date sources

The information on coronavirus is constantly changing. By now, everyone has seen the exponential curve of cases reoccurring all over the world at different times. Therefore, what was true last month may not necessarily be the case now. This can be challenging when you are planning an essay, because your outline from a previous week may need to be modified.

There are a number of ways you can address this. One way is, obviously, to continue going back and refreshing the data. Another way, which can be equally useful, is to outline the scope of the problem in your paper, writing something like, “data on COVID-19 is constantly changing, but the data presented was accurate at the time of writing”.

Avoid personal bias or opinion (unless asked!)

Everybody has an opinion – this opinion can often relate to how you or your family members have been affected by the pandemic (and the government response to this). People have lost jobs, have had to avoid family/friends, or have lost someone as a result of this pandemic. Life, for many, is very different.

While all of this is extremely important, it may not necessarily be relevant for an academic essay. One of the more challenging components of this type of academic paper is to try and remove yourself from the evidence you are providing. Now… there are exceptions. If you are writing a COVID-19 reflective essay, then it is your responsibility to include your opinion; otherwise, do your best to remain objective.

Avoid personal pronouns

Along the same lines as avoiding bias, it is also a good idea to avoid personal pronouns in your academic essay (except in a reflection, of course). This means avoiding words like “I, we, our, my”. While you may agree (or disagree) with the sentiment you are presenting, try and present your information from a distanced perspective.

Proofread carefully

Finally (and this is true of any essay), make sure that you take the time to proofread your essay carefully. Is it free from spelling errors? Have you checked the grammar? Have you made sure that your references are correct and in order? Have you carefully reviewed the submission requirements of your instructor (e.g. font, margins, spacing, etc.)? If the answer is yes, it sounds as if you are finally ready to submit your essay.

Final thoughts

Writing an essay is not easy. Writing an essay on a pandemic while living in that same pandemic is even more difficult.

A good essay is appropriately structured with a clear purpose and is presented according to the recommended guidelines. Unless it is a personal reflection, it attempts to present information as if it were free from bias.

So before you start to panic about having to write an essay about a pandemic, take a breath. You can do this. Take all the same steps as you would in a conventional academic essay, but expand your search to include relevant and up-to-date information that you know will make your essay a success. Once you have done this, make sure to have your university writing centre or an academic at Oxbridge Essays check it over and make suggestions! Now, stop reading and get writing! Good luck.

Essay exams: how to answer ‘To what extent…’

How to write a master’s essay

Writing Services

- Essay Plans

- Critical Reviews

- Literature Reviews

- Presentations

- Dissertation Title Creation

- Dissertation Proposals

- Dissertation Chapters

- PhD Proposals

- CV Writing Service

- Business Proofreading Services

Editing Services

- Proofreading Service

- Editing Service

- Academic Editing Service

Additional Services

- Marking Services

- Consultation Calls

- Personal Statements

- Tutoring Services

Our Company

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Become a Writer

Terms & Policies

- Fair Use Policy

- Policy for Students in England

- Privacy Policy

- Terms & Conditions

- [email protected]

- More contact options

Payment Methods

Cryptocurrency payments.

Read these 12 moving essays about life during coronavirus

Artists, novelists, critics, and essayists are writing the first draft of history.

by Alissa Wilkinson

The world is grappling with an invisible, deadly enemy, trying to understand how to live with the threat posed by a virus . For some writers, the only way forward is to put pen to paper, trying to conceptualize and document what it feels like to continue living as countries are under lockdown and regular life seems to have ground to a halt.

So as the coronavirus pandemic has stretched around the world, it’s sparked a crop of diary entries and essays that describe how life has changed. Novelists, critics, artists, and journalists have put words to the feelings many are experiencing. The result is a first draft of how we’ll someday remember this time, filled with uncertainty and pain and fear as well as small moments of hope and humanity.

- The Vox guide to navigating the coronavirus crisis

At the New York Review of Books, Ali Bhutto writes that in Karachi, Pakistan, the government-imposed curfew due to the virus is “eerily reminiscent of past military clampdowns”:

Beneath the quiet calm lies a sense that society has been unhinged and that the usual rules no longer apply. Small groups of pedestrians look on from the shadows, like an audience watching a spectacle slowly unfolding. People pause on street corners and in the shade of trees, under the watchful gaze of the paramilitary forces and the police.

His essay concludes with the sobering note that “in the minds of many, Covid-19 is just another life-threatening hazard in a city that stumbles from one crisis to another.”

Writing from Chattanooga, novelist Jamie Quatro documents the mixed ways her neighbors have been responding to the threat, and the frustration of conflicting direction, or no direction at all, from local, state, and federal leaders:

Whiplash, trying to keep up with who’s ordering what. We’re already experiencing enough chaos without this back-and-forth. Why didn’t the federal government issue a nationwide shelter-in-place at the get-go, the way other countries did? What happens when one state’s shelter-in-place ends, while others continue? Do states still under quarantine close their borders? We are still one nation, not fifty individual countries. Right?

- A syllabus for the end of the world

Award-winning photojournalist Alessio Mamo, quarantined with his partner Marta in Sicily after she tested positive for the virus, accompanies his photographs in the Guardian of their confinement with a reflection on being confined :

The doctors asked me to take a second test, but again I tested negative. Perhaps I’m immune? The days dragged on in my apartment, in black and white, like my photos. Sometimes we tried to smile, imagining that I was asymptomatic, because I was the virus. Our smiles seemed to bring good news. My mother left hospital, but I won’t be able to see her for weeks. Marta started breathing well again, and so did I. I would have liked to photograph my country in the midst of this emergency, the battles that the doctors wage on the frontline, the hospitals pushed to their limits, Italy on its knees fighting an invisible enemy. That enemy, a day in March, knocked on my door instead.

In the New York Times Magazine, deputy editor Jessica Lustig writes with devastating clarity about her family’s life in Brooklyn while her husband battled the virus, weeks before most people began taking the threat seriously:

At the door of the clinic, we stand looking out at two older women chatting outside the doorway, oblivious. Do I wave them away? Call out that they should get far away, go home, wash their hands, stay inside? Instead we just stand there, awkwardly, until they move on. Only then do we step outside to begin the long three-block walk home. I point out the early magnolia, the forsythia. T says he is cold. The untrimmed hairs on his neck, under his beard, are white. The few people walking past us on the sidewalk don’t know that we are visitors from the future. A vision, a premonition, a walking visitation. This will be them: Either T, in the mask, or — if they’re lucky — me, tending to him.

Essayist Leslie Jamison writes in the New York Review of Books about being shut away alone in her New York City apartment with her 2-year-old daughter since she became sick:

The virus. Its sinewy, intimate name. What does it feel like in my body today? Shivering under blankets. A hot itch behind the eyes. Three sweatshirts in the middle of the day. My daughter trying to pull another blanket over my body with her tiny arms. An ache in the muscles that somehow makes it hard to lie still. This loss of taste has become a kind of sensory quarantine. It’s as if the quarantine keeps inching closer and closer to my insides. First I lost the touch of other bodies; then I lost the air; now I’ve lost the taste of bananas. Nothing about any of these losses is particularly unique. I’ve made a schedule so I won’t go insane with the toddler. Five days ago, I wrote Walk/Adventure! on it, next to a cut-out illustration of a tiger—as if we’d see tigers on our walks. It was good to keep possibility alive.

At Literary Hub, novelist Heidi Pitlor writes about the elastic nature of time during her family’s quarantine in Massachusetts:

During a shutdown, the things that mark our days—commuting to work, sending our kids to school, having a drink with friends—vanish and time takes on a flat, seamless quality. Without some self-imposed structure, it’s easy to feel a little untethered. A friend recently posted on Facebook: “For those who have lost track, today is Blursday the fortyteenth of Maprilay.” ... Giving shape to time is especially important now, when the future is so shapeless. We do not know whether the virus will continue to rage for weeks or months or, lord help us, on and off for years. We do not know when we will feel safe again. And so many of us, minus those who are gifted at compartmentalization or denial, remain largely captive to fear. We may stay this way if we do not create at least the illusion of movement in our lives, our long days spent with ourselves or partners or families.

- What day is it today?

Novelist Lauren Groff writes at the New York Review of Books about trying to escape the prison of her fears while sequestered at home in Gainesville, Florida:

Some people have imaginations sparked only by what they can see; I blame this blinkered empiricism for the parks overwhelmed with people, the bars, until a few nights ago, thickly thronged. My imagination is the opposite. I fear everything invisible to me. From the enclosure of my house, I am afraid of the suffering that isn’t present before me, the people running out of money and food or drowning in the fluid in their lungs, the deaths of health-care workers now growing ill while performing their duties. I fear the federal government, which the right wing has so—intentionally—weakened that not only is it insufficient to help its people, it is actively standing in help’s way. I fear we won’t sufficiently punish the right. I fear leaving the house and spreading the disease. I fear what this time of fear is doing to my children, their imaginations, and their souls.

At ArtForum , Berlin-based critic and writer Kristian Vistrup Madsen reflects on martinis, melancholia, and Finnish artist Jaakko Pallasvuo’s 2018 graphic novel Retreat , in which three young people exile themselves in the woods:

In melancholia, the shape of what is ending, and its temporality, is sprawling and incomprehensible. The ambivalence makes it hard to bear. The world of Retreat is rendered in lush pink and purple watercolors, which dissolve into wild and messy abstractions. In apocalypse, the divisions established in genesis bleed back out. My own Corona-retreat is similarly soft, color-field like, each day a blurred succession of quarantinis, YouTube–yoga, and televized press conferences. As restrictions mount, so does abstraction. For now, I’m still rooting for love to save the world.

At the Paris Review , Matt Levin writes about reading Virginia Woolf’s novel The Waves during quarantine:

A retreat, a quarantine, a sickness—they simultaneously distort and clarify, curtail and expand. It is an ideal state in which to read literature with a reputation for difficulty and inaccessibility, those hermetic books shorn of the handholds of conventional plot or characterization or description. A novel like Virginia Woolf’s The Waves is perfect for the state of interiority induced by quarantine—a story of three men and three women, meeting after the death of a mutual friend, told entirely in the overlapping internal monologues of the six, interspersed only with sections of pure, achingly beautiful descriptions of the natural world, a day’s procession and recession of light and waves. The novel is, in my mind’s eye, a perfectly spherical object. It is translucent and shimmering and infinitely fragile, prone to shatter at the slightest disturbance. It is not a book that can be read in snatches on the subway—it demands total absorption. Though it revels in a stark emotional nakedness, the book remains aloof, remote in its own deep self-absorption.

- Vox is starting a book club. Come read with us!

In an essay for the Financial Times, novelist Arundhati Roy writes with anger about Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s anemic response to the threat, but also offers a glimmer of hope for the future:

Historically, pandemics have forced humans to break with the past and imagine their world anew. This one is no different. It is a portal, a gateway between one world and the next. We can choose to walk through it, dragging the carcasses of our prejudice and hatred, our avarice, our data banks and dead ideas, our dead rivers and smoky skies behind us. Or we can walk through lightly, with little luggage, ready to imagine another world. And ready to fight for it.

From Boston, Nora Caplan-Bricker writes in The Point about the strange contraction of space under quarantine, in which a friend in Beirut is as close as the one around the corner in the same city:

It’s a nice illusion—nice to feel like we’re in it together, even if my real world has shrunk to one person, my husband, who sits with his laptop in the other room. It’s nice in the same way as reading those essays that reframe social distancing as solidarity. “We must begin to see the negative space as clearly as the positive, to know what we don’t do is also brilliant and full of love,” the poet Anne Boyer wrote on March 10th, the day that Massachusetts declared a state of emergency. If you squint, you could almost make sense of this quarantine as an effort to flatten, along with the curve, the distinctions we make between our bonds with others. Right now, I care for my neighbor in the same way I demonstrate love for my mother: in all instances, I stay away. And in moments this month, I have loved strangers with an intensity that is new to me. On March 14th, the Saturday night after the end of life as we knew it, I went out with my dog and found the street silent: no lines for restaurants, no children on bicycles, no couples strolling with little cups of ice cream. It had taken the combined will of thousands of people to deliver such a sudden and complete emptiness. I felt so grateful, and so bereft.

And on his own website, musician and artist David Byrne writes about rediscovering the value of working for collective good , saying that “what is happening now is an opportunity to learn how to change our behavior”:

In emergencies, citizens can suddenly cooperate and collaborate. Change can happen. We’re going to need to work together as the effects of climate change ramp up. In order for capitalism to survive in any form, we will have to be a little more socialist. Here is an opportunity for us to see things differently — to see that we really are all connected — and adjust our behavior accordingly. Are we willing to do this? Is this moment an opportunity to see how truly interdependent we all are? To live in a world that is different and better than the one we live in now? We might be too far down the road to test every asymptomatic person, but a change in our mindsets, in how we view our neighbors, could lay the groundwork for the collective action we’ll need to deal with other global crises. The time to see how connected we all are is now.

The portrait these writers paint of a world under quarantine is multifaceted. Our worlds have contracted to the confines of our homes, and yet in some ways we’re more connected than ever to one another. We feel fear and boredom, anger and gratitude, frustration and strange peace. Uncertainty drives us to find metaphors and images that will let us wrap our minds around what is happening.

Yet there’s no single “what” that is happening. Everyone is contending with the pandemic and its effects from different places and in different ways. Reading others’ experiences — even the most frightening ones — can help alleviate the loneliness and dread, a little, and remind us that what we’re going through is both unique and shared by all.

Most Popular

The hottest place on earth is cracking from the stress of extreme heat, the backlash against children’s youtuber ms rachel, explained, india just showed the world how to fight an authoritarian on the rise, trump’s felony conviction has hurt him in the polls, take a mental break with the newest vox crossword, today, explained.

Understand the world with a daily explainer plus the most compelling stories of the day.

More in Culture

Kate Middleton’s cancer diagnosis, explained

Why are we so obsessed with morning routines?

Here are all 50+ sexual misconduct allegations against Kevin Spacey

Is TikTok breaking young voters’ brains?

Backgrid paparazzi photos are everywhere. Is that such a big deal?

World leaders neglected this crisis. Now genocide looms.

Cities know how to improve traffic. They keep making the same colossal mistake.

Why China is winning the EV war Video

The messy discussion around Caitlin Clark, Chennedy Carter, and the WNBA, explained

Modi won the Indian election. So why does it seem like he lost?

- Today's news

- Reviews and deals

- Climate change

- 2024 election

- Fall allergies

- Health news

- Mental health

- Sexual health

- Family health

- So mini ways

- Unapologetically

- Buying guides

Entertainment

- How to Watch

- My watchlist

- Stock market

- Biden economy

- Personal finance

- Stocks: most active

- Stocks: gainers

- Stocks: losers

- Trending tickers

- World indices

- US Treasury bonds

- Top mutual funds

- Highest open interest

- Highest implied volatility

- Currency converter

- Basic materials

- Communication services

- Consumer cyclical

- Consumer defensive

- Financial services

- Industrials

- Real estate

- Mutual funds

- Credit cards

- Balance transfer cards

- Cash back cards

- Rewards cards

- Travel cards

- Online checking

- High-yield savings

- Money market

- Home equity loan

- Personal loans

- Student loans

- Options pit

- Fantasy football

- Pro Pick 'Em

- College Pick 'Em

- Fantasy baseball

- Fantasy hockey

- Fantasy basketball

- Download the app

- Daily fantasy

- Scores and schedules

- GameChannel

- World Baseball Classic

- Premier League

- CONCACAF League

- Champions League

- Motorsports

- Horse racing

- Newsletters

New on Yahoo

- Privacy Dashboard

How to Write About the Impact of the Coronavirus in a College Essay

The global impact of COVID-19, the disease caused by the novel coronavirus, means colleges and prospective students alike are in for an admissions cycle like no other. Both face unprecedented challenges and questions as they grapple with their respective futures amid the ongoing fallout of the pandemic.

Colleges must examine applicants without the aid of standardized test scores for many -- a factor that prompted many schools to go test-optional for now . Even grades, a significant component of a college application, may be hard to interpret with some high schools adopting pass-fail classes last spring due to the pandemic. Major college admissions factors are suddenly skewed.

"I can't help but think other (admissions) factors are going to matter more," says Ethan Sawyer, founder of the College Essay Guy, a website that offers free and paid essay-writing resources.

College essays and letters of recommendation , Sawyer says, are likely to carry more weight than ever in this admissions cycle. And many essays will likely focus on how the pandemic shaped students' lives throughout an often tumultuous 2020.

[ Read: How to Write a College Essay. ]

But before writing a college essay focused on the coronavirus, students should explore whether it's the best topic for them.

Writing About COVID-19 for a College Application

Much of daily life has been colored by the coronavirus. Virtual learning is the norm at many colleges and high schools, many extracurriculars have vanished and social lives have stalled for students complying with measures to stop the spread of COVID-19.

"For some young people, the pandemic took away what they envisioned as their senior year," says Robert Alexander, dean of admissions, financial aid and enrollment management at the University of Rochester in New York. "Maybe that's a spot on a varsity athletic team or the lead role in the fall play. And it's OK for them to mourn what should have been and what they feel like they lost, but more important is how are they making the most of the opportunities they do have?"

That question, Alexander says, is what colleges want answered if students choose to address COVID-19 in their college essay.

But the question of whether a student should write about the coronavirus is tricky. The answer depends largely on the student.

"In general, I don't think students should write about COVID-19 in their main personal statement for their application," Robin Miller, master college admissions counselor at IvyWise, a college counseling company, wrote in an email.

"Certainly, there may be exceptions to this based on a student's individual experience, but since the personal essay is the main place in the application where the student can really allow their voice to be heard and share insight into who they are as an individual, there are likely many other topics they can choose to write about that are more distinctive and unique than COVID-19," Miller says.

[ Read: What Colleges Look for: 6 Ways to Stand Out. ]

Opinions among admissions experts vary on whether to write about the likely popular topic of the pandemic.

"If your essay communicates something positive, unique, and compelling about you in an interesting and eloquent way, go for it," Carolyn Pippen, principal college admissions counselor at IvyWise, wrote in an email. She adds that students shouldn't be dissuaded from writing about a topic merely because it's common, noting that "topics are bound to repeat, no matter how hard we try to avoid it."

Above all, she urges honesty.

"If your experience within the context of the pandemic has been truly unique, then write about that experience, and the standing out will take care of itself," Pippen says. "If your experience has been generally the same as most other students in your context, then trying to find a unique angle can easily cross the line into exploiting a tragedy, or at least appearing as though you have."

But focusing entirely on the pandemic can limit a student to a single story and narrow who they are in an application, Sawyer says. "There are so many wonderful possibilities for what you can say about yourself outside of your experience within the pandemic."

He notes that passions, strengths, career interests and personal identity are among the multitude of essay topic options available to applicants and encourages them to probe their values to help determine the topic that matters most to them -- and write about it.

That doesn't mean the pandemic experience has to be ignored if applicants feel the need to write about it.

Writing About Coronavirus in Main and Supplemental Essays

Students can choose to write a full-length college essay on the coronavirus or summarize their experience in a shorter form.

To help students explain how the pandemic affected them, The Common App has added an optional section to address this topic. Applicants have 250 words to describe their pandemic experience and the personal and academic impact of COVID-19.

[ Read: The Common App: Everything You Need to Know. ]

"That's not a trick question, and there's no right or wrong answer," Alexander says. Colleges want to know, he adds, how students navigated the pandemic, how they prioritized their time, what responsibilities they took on and what they learned along the way.

If students can distill all of the above information into 250 words, there's likely no need to write about it in a full-length college essay, experts say. And applicants whose lives were not heavily altered by the pandemic may even choose to skip the optional COVID-19 question.

"This space is best used to discuss hardship and/or significant challenges that the student and/or the student's family experienced as a result of COVID-19 and how they have responded to those difficulties," Miller notes. Using the section to acknowledge a lack of impact, she adds, "could be perceived as trite and lacking insight, despite the good intentions of the applicant."

To guard against this lack of awareness, Sawyer encourages students to tap someone they trust to review their writing , whether it's the 250-word Common App response or the full-length essay.

Experts tend to agree that the short-form approach to this as an essay topic works better, but there are exceptions. And if a student does have a coronavirus story that he or she feels must be told, Alexander encourages the writer to be authentic in the essay.

"My advice for an essay about COVID-19 is the same as my advice about an essay for any topic -- and that is, don't write what you think we want to read or hear," Alexander says. "Write what really changed you and that story that now is yours and yours alone to tell."

Sawyer urges students to ask themselves, "What's the sentence that only I can write?" He also encourages students to remember that the pandemic is only a chapter of their lives and not the whole book.

Miller, who cautions against writing a full-length essay on the coronavirus, says that if students choose to do so they should have a conversation with their high school counselor about whether that's the right move. And if students choose to proceed with COVID-19 as a topic, she says they need to be clear, detailed and insightful about what they learned and how they adapted along the way.

"Approaching the essay in this manner will provide important balance while demonstrating personal growth and vulnerability," Miller says.

Pippen encourages students to remember that they are in an unprecedented time for college admissions.

"It is important to keep in mind with all of these (admission) factors that no colleges have ever had to consider them this way in the selection process, if at all," Pippen says. "They have had very little time to calibrate their evaluations of different application components within their offices, let alone across institutions. This means that colleges will all be handling the admissions process a little bit differently, and their approaches may even evolve over the course of the admissions cycle."

Searching for a college? Get our complete rankings of Best Colleges.

- CBSE Class 10th

- CBSE Class 12th

- UP Board 10th

- UP Board 12th

- Bihar Board 10th

- Bihar Board 12th

- Top Schools in India

- Top Schools in Delhi

- Top Schools in Mumbai

- Top Schools in Chennai

- Top Schools in Hyderabad

- Top Schools in Kolkata

- Top Schools in Pune

- Top Schools in Bangalore

Products & Resources

- JEE Main Knockout April

- Free Sample Papers

- Free Ebooks

- NCERT Notes

- NCERT Syllabus

- NCERT Books

- RD Sharma Solutions

- Navodaya Vidyalaya Admission 2024-25

- NCERT Solutions

- NCERT Solutions for Class 12

- NCERT Solutions for Class 11

- NCERT solutions for Class 10

- NCERT solutions for Class 9

- NCERT solutions for Class 8

- NCERT Solutions for Class 7

- JEE Main 2024

- MHT CET 2024

- JEE Advanced 2024

- BITSAT 2024

- View All Engineering Exams

- Colleges Accepting B.Tech Applications

- Top Engineering Colleges in India

- Engineering Colleges in India

- Engineering Colleges in Tamil Nadu

- Engineering Colleges Accepting JEE Main

- Top IITs in India

- Top NITs in India

- Top IIITs in India

- JEE Main College Predictor

- JEE Main Rank Predictor

- MHT CET College Predictor

- AP EAMCET College Predictor

- GATE College Predictor

- KCET College Predictor

- JEE Advanced College Predictor

- View All College Predictors

- JEE Advanced Cutoff

- JEE Main Cutoff

- MHT CET Result 2024

- JEE Advanced Result

- Download E-Books and Sample Papers

- Compare Colleges

- B.Tech College Applications

- AP EAMCET Result 2024

- MAH MBA CET Exam

- View All Management Exams

Colleges & Courses

- MBA College Admissions

- MBA Colleges in India

- Top IIMs Colleges in India

- Top Online MBA Colleges in India

- MBA Colleges Accepting XAT Score

- BBA Colleges in India

- XAT College Predictor 2024

- SNAP College Predictor

- NMAT College Predictor

- MAT College Predictor 2024

- CMAT College Predictor 2024

- CAT Percentile Predictor 2024

- CAT 2024 College Predictor

- TS ICET 2024 Results

- AP ICET Counselling 2024

- CMAT Result 2024

- MAH MBA CET Cutoff 2024

- Download Helpful Ebooks

- List of Popular Branches

- QnA - Get answers to your doubts

- IIM Fees Structure

- AIIMS Nursing

- Top Medical Colleges in India

- Top Medical Colleges in India accepting NEET Score

- Medical Colleges accepting NEET

- List of Medical Colleges in India

- List of AIIMS Colleges In India

- Medical Colleges in Maharashtra

- Medical Colleges in India Accepting NEET PG

- NEET College Predictor

- NEET PG College Predictor

- NEET MDS College Predictor

- NEET Rank Predictor

- DNB PDCET College Predictor

- NEET Result 2024

- NEET Asnwer Key 2024

- NEET Cut off

- NEET Online Preparation

- Download Helpful E-books

- Colleges Accepting Admissions

- Top Law Colleges in India

- Law College Accepting CLAT Score

- List of Law Colleges in India

- Top Law Colleges in Delhi

- Top NLUs Colleges in India

- Top Law Colleges in Chandigarh

- Top Law Collages in Lucknow

Predictors & E-Books

- CLAT College Predictor

- MHCET Law ( 5 Year L.L.B) College Predictor

- AILET College Predictor

- Sample Papers

- Compare Law Collages

- Careers360 Youtube Channel

- CLAT Syllabus 2025

- CLAT Previous Year Question Paper

- NID DAT Exam

- Pearl Academy Exam

Predictors & Articles

- NIFT College Predictor

- UCEED College Predictor

- NID DAT College Predictor

- NID DAT Syllabus 2025

- NID DAT 2025

- Design Colleges in India

- Top NIFT Colleges in India

- Fashion Design Colleges in India

- Top Interior Design Colleges in India

- Top Graphic Designing Colleges in India

- Fashion Design Colleges in Delhi

- Fashion Design Colleges in Mumbai

- Top Interior Design Colleges in Bangalore

- NIFT Result 2024

- NIFT Fees Structure

- NIFT Syllabus 2025

- Free Design E-books

- List of Branches

- Careers360 Youtube channel

- IPU CET BJMC

- JMI Mass Communication Entrance Exam

- IIMC Entrance Exam

- Media & Journalism colleges in Delhi

- Media & Journalism colleges in Bangalore

- Media & Journalism colleges in Mumbai

- List of Media & Journalism Colleges in India

- CA Intermediate

- CA Foundation

- CS Executive

- CS Professional

- Difference between CA and CS

- Difference between CA and CMA

- CA Full form

- CMA Full form

- CS Full form

- CA Salary In India

Top Courses & Careers

- Bachelor of Commerce (B.Com)

- Master of Commerce (M.Com)

- Company Secretary

- Cost Accountant

- Charted Accountant

- Credit Manager

- Financial Advisor

- Top Commerce Colleges in India

- Top Government Commerce Colleges in India

- Top Private Commerce Colleges in India

- Top M.Com Colleges in Mumbai

- Top B.Com Colleges in India

- IT Colleges in Tamil Nadu

- IT Colleges in Uttar Pradesh

- MCA Colleges in India

- BCA Colleges in India

Quick Links

- Information Technology Courses

- Programming Courses

- Web Development Courses

- Data Analytics Courses

- Big Data Analytics Courses

- RUHS Pharmacy Admission Test

- Top Pharmacy Colleges in India

- Pharmacy Colleges in Pune

- Pharmacy Colleges in Mumbai

- Colleges Accepting GPAT Score

- Pharmacy Colleges in Lucknow

- List of Pharmacy Colleges in Nagpur

- GPAT Result

- GPAT 2024 Admit Card

- GPAT Question Papers

- NCHMCT JEE 2024

- Mah BHMCT CET

- Top Hotel Management Colleges in Delhi

- Top Hotel Management Colleges in Hyderabad

- Top Hotel Management Colleges in Mumbai

- Top Hotel Management Colleges in Tamil Nadu

- Top Hotel Management Colleges in Maharashtra

- B.Sc Hotel Management

- Hotel Management

- Diploma in Hotel Management and Catering Technology

Diploma Colleges

- Top Diploma Colleges in Maharashtra

- UPSC IAS 2024

- SSC CGL 2024

- IBPS RRB 2024

- Previous Year Sample Papers

- Free Competition E-books

- Sarkari Result

- QnA- Get your doubts answered

- UPSC Previous Year Sample Papers

- CTET Previous Year Sample Papers

- SBI Clerk Previous Year Sample Papers

- NDA Previous Year Sample Papers

Upcoming Events

- NDA Application Form 2024

- UPSC IAS Application Form 2024

- CDS Application Form 2024

- CTET Admit card 2024

- HP TET Result 2023

- SSC GD Constable Admit Card 2024

- UPTET Notification 2024

- SBI Clerk Result 2024

Other Exams

- SSC CHSL 2024

- UP PCS 2024

- UGC NET 2024

- RRB NTPC 2024

- IBPS PO 2024

- IBPS Clerk 2024

- IBPS SO 2024

- Top University in USA

- Top University in Canada

- Top University in Ireland

- Top Universities in UK

- Top Universities in Australia

- Best MBA Colleges in Abroad

- Business Management Studies Colleges

Top Countries

- Study in USA

- Study in UK

- Study in Canada

- Study in Australia

- Study in Ireland

- Study in Germany

- Study in China

- Study in Europe

Student Visas

- Student Visa Canada

- Student Visa UK

- Student Visa USA

- Student Visa Australia

- Student Visa Germany

- Student Visa New Zealand

- Student Visa Ireland

- CUET PG 2024

- IGNOU B.Ed Admission 2024

- DU Admission 2024

- UP B.Ed JEE 2024

- LPU NEST 2024

- IIT JAM 2024

- IGNOU Online Admission 2024

- Universities in India

- Top Universities in India 2024

- Top Colleges in India

- Top Universities in Uttar Pradesh 2024

- Top Universities in Bihar

- Top Universities in Madhya Pradesh 2024

- Top Universities in Tamil Nadu 2024

- Central Universities in India

- CUET DU Cut off 2024

- IGNOU Date Sheet

- CUET DU CSAS Portal 2024

- CUET Response Sheet 2024

- CUET Result 2024

- CUET Participating Universities 2024

- CUET Previous Year Question Paper

- CUET Syllabus 2024 for Science Students

- E-Books and Sample Papers

- CUET Exam Pattern 2024

- CUET Exam Date 2024

- CUET Cut Off 2024

- CUET Exam Analysis 2024

- IGNOU Exam Form 2024

- CUET PG Counselling 2024

- CUET Answer Key 2024

Engineering Preparation

- Knockout JEE Main 2024

- Test Series JEE Main 2024

- JEE Main 2024 Rank Booster

Medical Preparation

- Knockout NEET 2024

- Test Series NEET 2024

- Rank Booster NEET 2024

Online Courses

- JEE Main One Month Course

- NEET One Month Course

- IBSAT Free Mock Tests

- IIT JEE Foundation Course

- Knockout BITSAT 2024

- Career Guidance Tool

Top Streams

- IT & Software Certification Courses

- Engineering and Architecture Certification Courses

- Programming And Development Certification Courses

- Business and Management Certification Courses

- Marketing Certification Courses

- Health and Fitness Certification Courses

- Design Certification Courses

Specializations

- Digital Marketing Certification Courses

- Cyber Security Certification Courses

- Artificial Intelligence Certification Courses

- Business Analytics Certification Courses

- Data Science Certification Courses

- Cloud Computing Certification Courses

- Machine Learning Certification Courses

- View All Certification Courses

- UG Degree Courses

- PG Degree Courses

- Short Term Courses

- Free Courses

- Online Degrees and Diplomas

- Compare Courses

Top Providers

- Coursera Courses

- Udemy Courses

- Edx Courses

- Swayam Courses

- upGrad Courses

- Simplilearn Courses

- Great Learning Courses

Covid 19 Essay in English

Essay on Covid -19: In a very short amount of time, coronavirus has spread globally. It has had an enormous impact on people's lives, economy, and societies all around the world, affecting every country. Governments have had to take severe measures to try and contain the pandemic. The virus has altered our way of life in many ways, including its effects on our health and our economy. Here are a few sample essays on ‘CoronaVirus’.

100 Words Essay on Covid 19

200 words essay on covid 19, 500 words essay on covid 19.

COVID-19 or Corona Virus is a novel coronavirus that was first identified in 2019. It is similar to other coronaviruses, such as SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV, but it is more contagious and has caused more severe respiratory illness in people who have been infected. The novel coronavirus became a global pandemic in a very short period of time. It has affected lives, economies and societies across the world, leaving no country untouched. The virus has caused governments to take drastic measures to try and contain it. From health implications to economic and social ramifications, COVID-19 impacted every part of our lives. It has been more than 2 years since the pandemic hit and the world is still recovering from its effects.

Since the outbreak of COVID-19, the world has been impacted in a number of ways. For one, the global economy has taken a hit as businesses have been forced to close their doors. This has led to widespread job losses and an increase in poverty levels around the world. Additionally, countries have had to impose strict travel restrictions in an attempt to contain the virus, which has resulted in a decrease in tourism and international trade. Furthermore, the pandemic has put immense pressure on healthcare systems globally, as hospitals have been overwhelmed with patients suffering from the virus. Lastly, the outbreak has led to a general feeling of anxiety and uncertainty, as people are fearful of contracting the disease.

My Experience of COVID-19

I still remember how abruptly colleges and schools shut down in March 2020. I was a college student at that time and I was under the impression that everything would go back to normal in a few weeks. I could not have been more wrong. The situation only got worse every week and the government had to impose a lockdown. There were so many restrictions in place. For example, we had to wear face masks whenever we left the house, and we could only go out for essential errands. Restaurants and shops were only allowed to operate at take-out capacity, and many businesses were shut down.

In the current scenario, coronavirus is dominating all aspects of our lives. The coronavirus pandemic has wreaked havoc upon people’s lives, altering the way we live and work in a very short amount of time. It has revolutionised how we think about health care, education, and even social interaction. This virus has had long-term implications on our society, including its impact on mental health, economic stability, and global politics. But we as individuals can help to mitigate these effects by taking personal responsibility to protect themselves and those around them from infection.

Effects of CoronaVirus on Education

The outbreak of coronavirus has had a significant impact on education systems around the world. In China, where the virus originated, all schools and universities were closed for several weeks in an effort to contain the spread of the disease. Many other countries have followed suit, either closing schools altogether or suspending classes for a period of time.

This has resulted in a major disruption to the education of millions of students. Some have been able to continue their studies online, but many have not had access to the internet or have not been able to afford the costs associated with it. This has led to a widening of the digital divide between those who can afford to continue their education online and those who cannot.

The closure of schools has also had a negative impact on the mental health of many students. With no face-to-face contact with friends and teachers, some students have felt isolated and anxious. This has been compounded by the worry and uncertainty surrounding the virus itself.

The situation with coronavirus has improved and schools have been reopened but students are still catching up with the gap of 2 years that the pandemic created. In the meantime, governments and educational institutions are working together to find ways to support students and ensure that they are able to continue their education despite these difficult circumstances.

Effects of CoronaVirus on Economy

The outbreak of the coronavirus has had a significant impact on the global economy. The virus, which originated in China, has spread to over two hundred countries, resulting in widespread panic and a decrease in global trade. As a result of the outbreak, many businesses have been forced to close their doors, leading to a rise in unemployment. In addition, the stock market has taken a severe hit.

Effects of CoronaVirus on Health

The effects that coronavirus has on one's health are still being studied and researched as the virus continues to spread throughout the world. However, some of the potential effects on health that have been observed thus far include respiratory problems, fever, and coughing. In severe cases, pneumonia, kidney failure, and death can occur. It is important for people who think they may have been exposed to the virus to seek medical attention immediately so that they can be treated properly and avoid any serious complications. There is no specific cure or treatment for coronavirus at this time, but there are ways to help ease symptoms and prevent the virus from spreading.

Applications for Admissions are open.

Aakash iACST Scholarship Test 2024

Get up to 90% scholarship on NEET, JEE & Foundation courses

ALLEN Digital Scholarship Admission Test (ADSAT)

Register FREE for ALLEN Digital Scholarship Admission Test (ADSAT)

JEE Main Important Physics formulas

As per latest 2024 syllabus. Physics formulas, equations, & laws of class 11 & 12th chapters

PW JEE Coaching

Enrol in PW Vidyapeeth center for JEE coaching

JEE Main Important Chemistry formulas

As per latest 2024 syllabus. Chemistry formulas, equations, & laws of class 11 & 12th chapters

ALLEN JEE Exam Prep

Start your JEE preparation with ALLEN

Download Careers360 App's

Regular exam updates, QnA, Predictors, College Applications & E-books now on your Mobile

Certifications

We Appeared in

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Springer Nature - PMC COVID-19 Collection

An Introduction to COVID-19

Simon james fong.

4 Department of Computer and Information Science, University of Macau, Taipa, Macau, China

Nilanjan Dey

5 Department of Information Technology, Techno International New Town, Kolkata, West Bengal India

Jyotismita Chaki

6 School of Information Technology and Engineering, Vellore Institute of Technology, Vellore, Tamil Nadu India

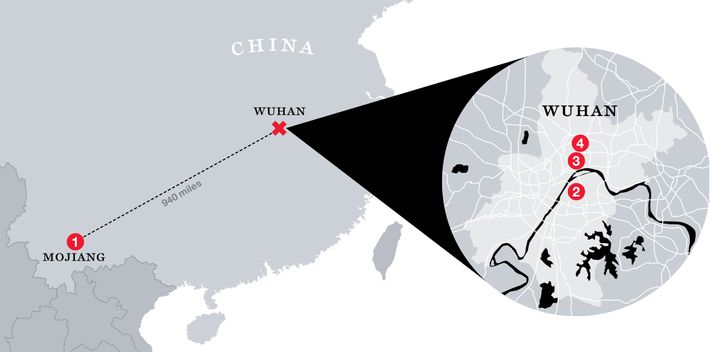

A novel coronavirus (CoV) named ‘2019-nCoV’ or ‘2019 novel coronavirus’ or ‘COVID-19’ by the World Health Organization (WHO) is in charge of the current outbreak of pneumonia that began at the beginning of December 2019 near in Wuhan City, Hubei Province, China [1–4]. COVID-19 is a pathogenic virus. From the phylogenetic analysis carried out with obtainable full genome sequences, bats occur to be the COVID-19 virus reservoir, but the intermediate host(s) has not been detected till now.

A Brief History of the Coronavirus Outbreak

A novel coronavirus (CoV) named ‘2019-nCoV’ or ‘2019 novel coronavirus’ or ‘COVID-19’ by the World Health Organization (WHO) is in charge of the current outbreak of pneumonia that began at the beginning of December 2019 near in Wuhan City, Hubei Province, China [ 1 – 4 ]. COVID-19 is a pathogenic virus. From the phylogenetic analysis carried out with obtainable full genome sequences, bats occur to be the COVID-19 virus reservoir, but the intermediate host(s) has not been detected till now. Though three major areas of work already are ongoing in China to advise our awareness of the pathogenic origin of the outbreak. These include early inquiries of cases with symptoms occurring near in Wuhan during December 2019, ecological sampling from the Huanan Wholesale Seafood Market as well as other area markets, and the collection of detailed reports of the point of origin and type of wildlife species marketed on the Huanan market and the destination of those animals after the market has been closed [ 5 – 8 ].

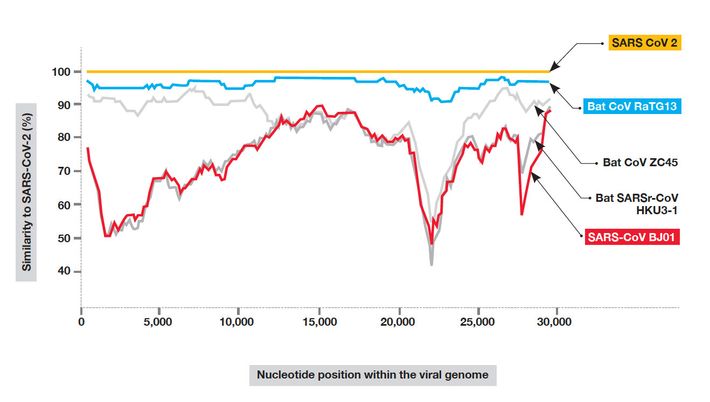

Coronaviruses mostly cause gastrointestinal and respiratory tract infections and are inherently categorized into four major types: Gammacoronavirus, Deltacoronavirus, Betacoronavirus and Alphacoronavirus [ 9 – 11 ]. The first two types mainly infect birds, while the last two mostly infect mammals. Six types of human CoVs have been formally recognized. These comprise HCoVHKU1, HCoV-OC43, Middle East Respiratory Syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV), Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV) which is the type of the Betacoronavirus, HCoV229E and HCoV-NL63, which are the member of the Alphacoronavirus. Coronaviruses did not draw global concern until the 2003 SARS pandemic [ 12 – 14 ], preceded by the 2012 MERS [ 15 – 17 ] and most recently by the COVID-19 outbreaks. SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV are known to be extremely pathogenic and spread from bats to palm civets or dromedary camels and eventually to humans.