- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- World History

- Health & Medicine

- Browse Biographies

- Birds, Reptiles & Other Vertebrates

- Bugs, Mollusks & Other Invertebrates

- Environment

- Fossils & Geologic Time

- Geography & Travel

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Sports & Recreation

- Visual Arts

- Introduction

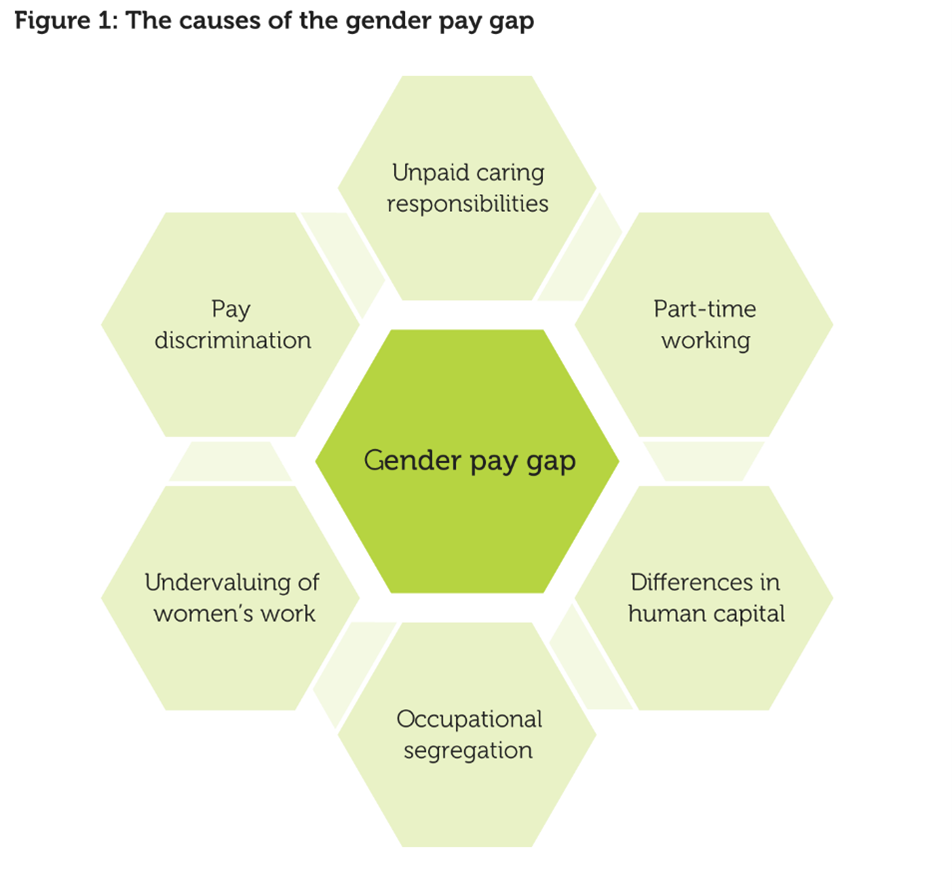

Causes of the gender pay gap

The cost of the gender pay gap, beyond binary, the bottom line.

Why we still have a gender pay gap in 2024

The gender wage gap continues to be a subject of study—mainly because it still exists even after women have made decades of progress in education and the workforce . So, why does the disparity in pay between men and women still exist?

- Societal expectations of caregiving prompt many women to take lower-paying jobs that offer flexibility.

- Even when women who are married to men earn the same as their spouses, they often spend more time on housekeeping and caregiving.

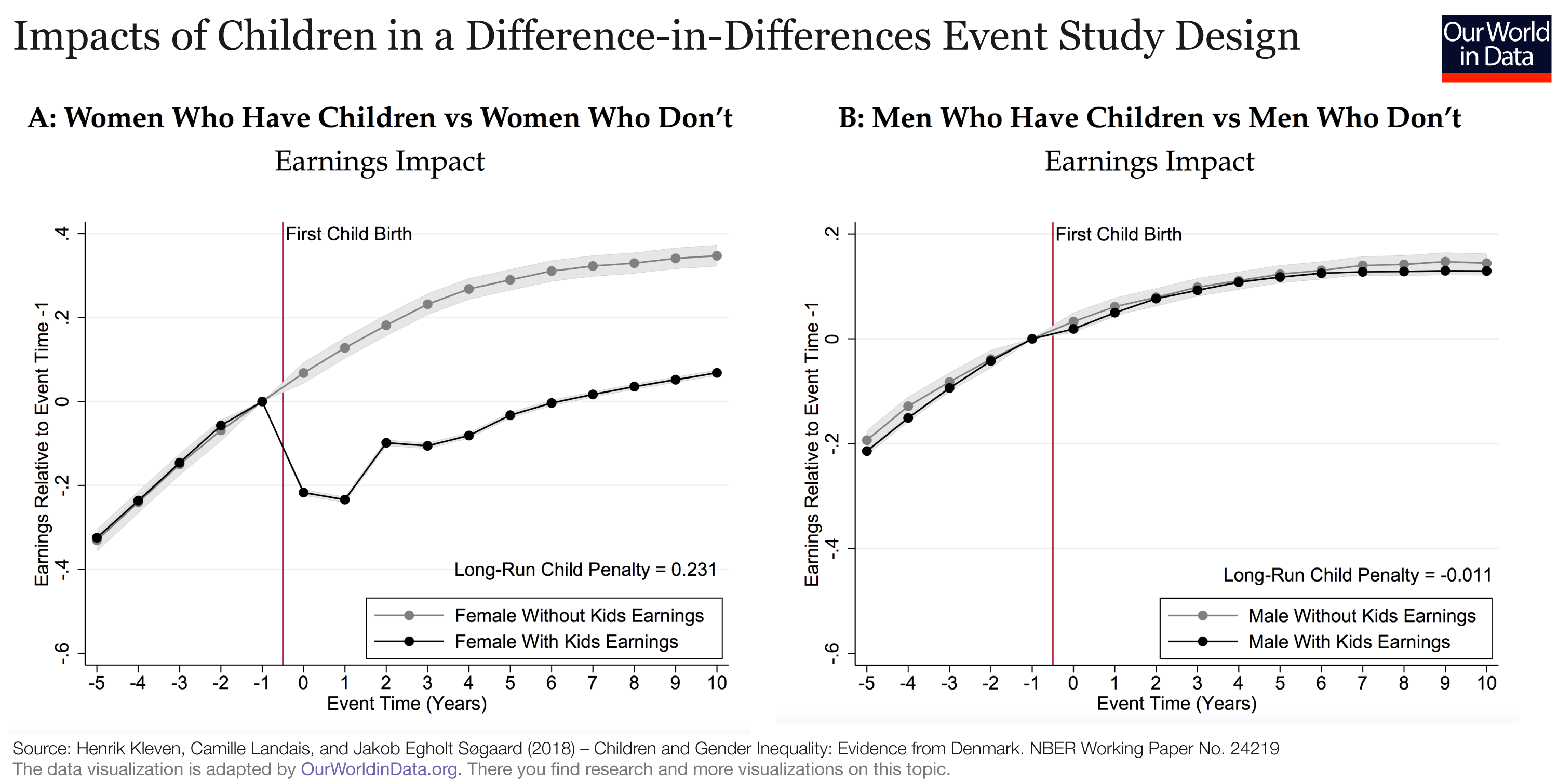

- On average, women who have children give up 15% of their wages to provide care, resulting in $295,000 in losses over a lifetime.

There’s no one cause of the gender pay gap. The Government Accountability Office (GAO) has found that women continue to be underrepresented in management positions . Also, the agency’s findings persistently show that a large portion of the gender pay gap is “unexplained” but might be “due to factors not captured in the data we analyzed, such as non-federal work experience, discrimination, and individual career choices, among others.”

Discrimination. The unjust or prejudiced views of other people or groups can be hard to quantify, since the government doesn’t analyze potential historical or systemic reasons for the pay gap, according to the GAO report. In addition to the conclusion by the U.S. Department of Labor (DOL) that 70% of the gap is “unexplained,” it’s also generally acknowledged that the pay gap is wider for women of color.

For every $1 paid to non-Hispanic white men, for example, Black women earned 67 cents, and Hispanic women were paid 57 cents. So even though it’s expected that equal pay laws and antidiscrimination laws cut down on pay disparity, it appears a large portion of the “unexplained” pay gap is attributable to discrimination, whether it’s based on sex, race, or both.

Career choice. The occupations workers find themselves in also contribute to gaps in pay, with some experts positing that women might simply “choose” to go into lower-paying careers. Claudia Goldin , who won the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences in 2023 for her work on the gender pay gap, has noted that just 10% to 33% of the gender pay gap is based on choice of occupation.

And “choice” might be the wrong word:

- Women are still expected to do the lion’s share of caregiving, meaning they often need to take lower-paying jobs that have more time flexibility, Goldin says.

- Women and “women’s work” continue to be undervalued in society, according to the Labor Department. When women enter a career field in greater numbers, the average pay for that occupation starts to decrease.

- Caregiving often results in women being forced out of the workforce, at least for a time, leading to increased chances for missed raises and promotions.

- About 63% of women with children under the age of 6 are employed in some capacity, compared to 71% of those with children age 6 or older. For men, there’s almost no difference in employment rates based on the ages of their children.

For women, the gender wage gap can be costly in a variety of ways:

- Lower starting salaries mean lower bases from which to get raises.

- Taking time out for caregiving duties leads to missed opportunities for higher pay and leads to gaps in contributing to retirement accounts .

- Less money saved for retirement is a problem when women have a longer life expectancy and are more likely to live in poverty during retirement .

- Some estimates indicate that the employment-related costs of women’s caregiving roles amount to about $295,000 for those born from 1981 to 1985 (in 2021 dollars adjusted for inflation ).

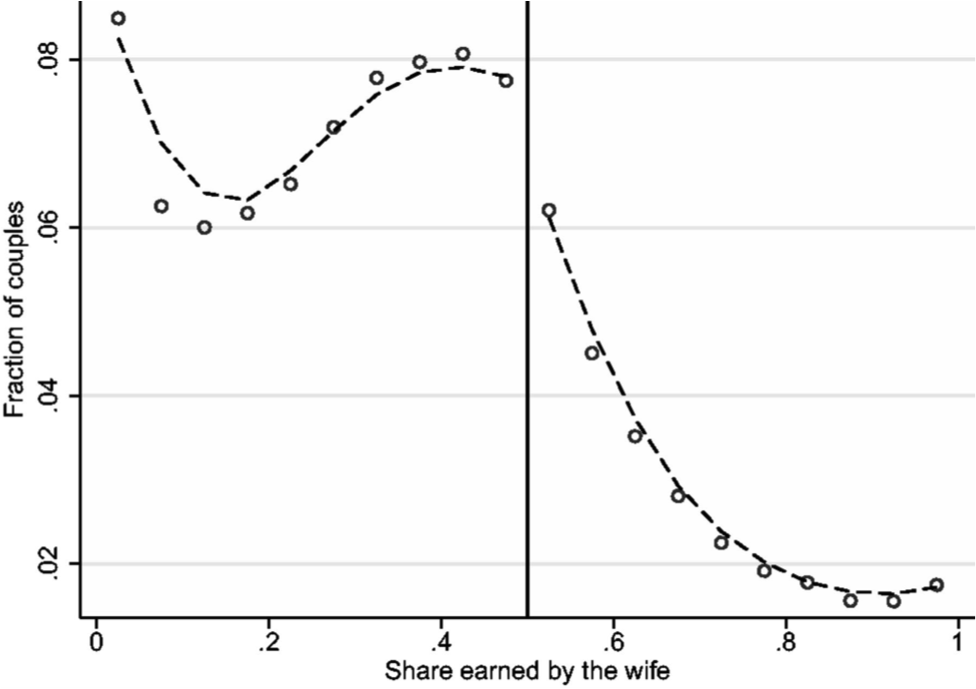

What about breadwinning women? Women who earn as much or more than their spouses in heterosexual marriages face nonmonetary costs, such as mental health issues or relationship challenges. The Pew Research Center found:

- In marriages where earnings were equal, women still spent more time on housework and caregiving, while men took more time for leisure.

- In marriages where wives were the primary earners, husbands’ leisure time increased significantly (compared with egalitarian marriages), while the time they spent on caregiving and housework stayed about the same.

- As the gender gap closes, male partners are less likely to pick up the slack at home, leaving more work for women.

In same-sex relationships , these discrepancies are less pronounced because gay and lesbian couples typically adhere less to stereotypical gender roles.

Disparity in wages doesn’t exist only between cisgender men and women. Those who identify as transgender or nonbinary earn 30% to 40% less than the typical worker, according to data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics and the Human Rights Campaign , an LGBTQ+ advocacy organization.

Because they earn less, lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender people are more likely to be poorer than their heterosexual counterparts. Research shows that lesbian and bisexual women, as well as lesbian, gay, and bisexual people of color, are especially vulnerable to poverty.

The pay gap between men and women is an entrenched issue with roots in the types of jobs women have typically performed (or were expected to do) and in gender stereotypes. Little progress has been made in closing the disparity in wages during the last 30 years. But the increasing number of women in leadership roles—including Mary Barra, CEO of General Motors ; U.S. Vice President Kamala Harris ; and entertainer Taylor Swift , who has fought for fair pay and whose enormous success has become a symbol of female empowerment—offer some promise that closing the gap may gain greater momentum.

By one estimate, however, the current, meager rate of increase means it will take at least another 35 years for women to reach pay parity. And for many working women, that day won’t come soon enough.

- Women Continue to Struggle for Equal Pay and Representation | gao.gov

- Women in the Workforce: Underrepresentation in Management Positions Persists, and the Gender Pay Gap Varies by Industry and Demographics | goa.gov

- [PDF] Understanding the Gender Wage Gap | dol.gov

- Gender Gap | econlib.org

- Gender Pay Gap? Culprit Is “Greedy Work” | news.harvard.edu

- In a Growing Share of U.S. Marriages, Husbands and Wives Earn About the Same | pewresearch.org

- Connecting the Dots: “Women’s Work” and the Wage Gap | blog.dol.gov

- Unpaid Family Care Continues to Suppress Women’s Earnings | urban.org

- Race and the Pay Gap | aauw.org

- Old-Age Poverty Has a Woman’s Face | un.org

- Getting a Job: Is There a Motherhood Penalty? | gap.hks.harvard.edu

- Full-Time Trans Workers Face a Wage Gap, Poll Finds | 19thnews.org

Report | Wages, Incomes, and Wealth

“Women’s work” and the gender pay gap : How discrimination, societal norms, and other forces affect women’s occupational choices—and their pay

Report • By Jessica Schieder and Elise Gould • July 20, 2016

Download PDF

Press release

Share this page:

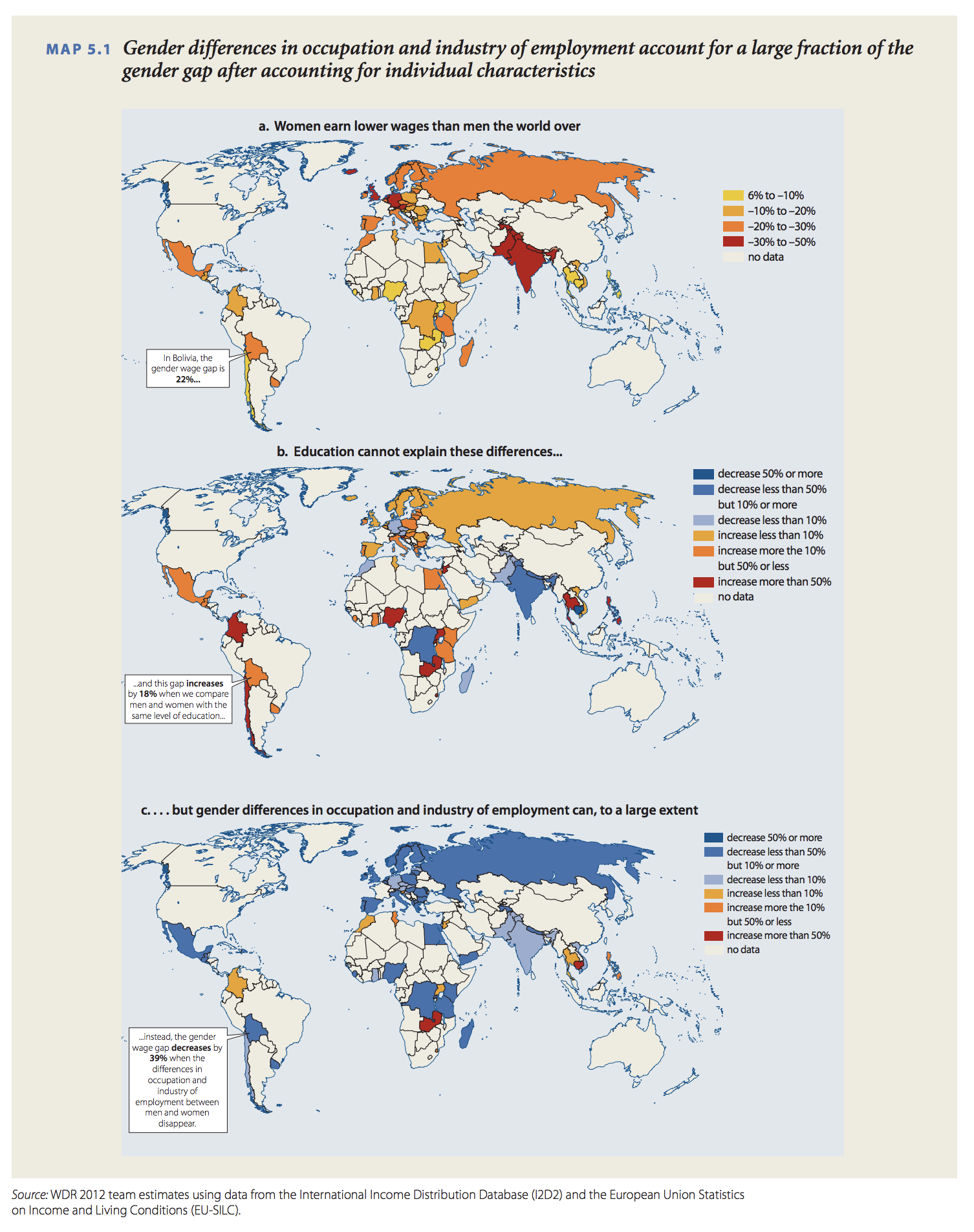

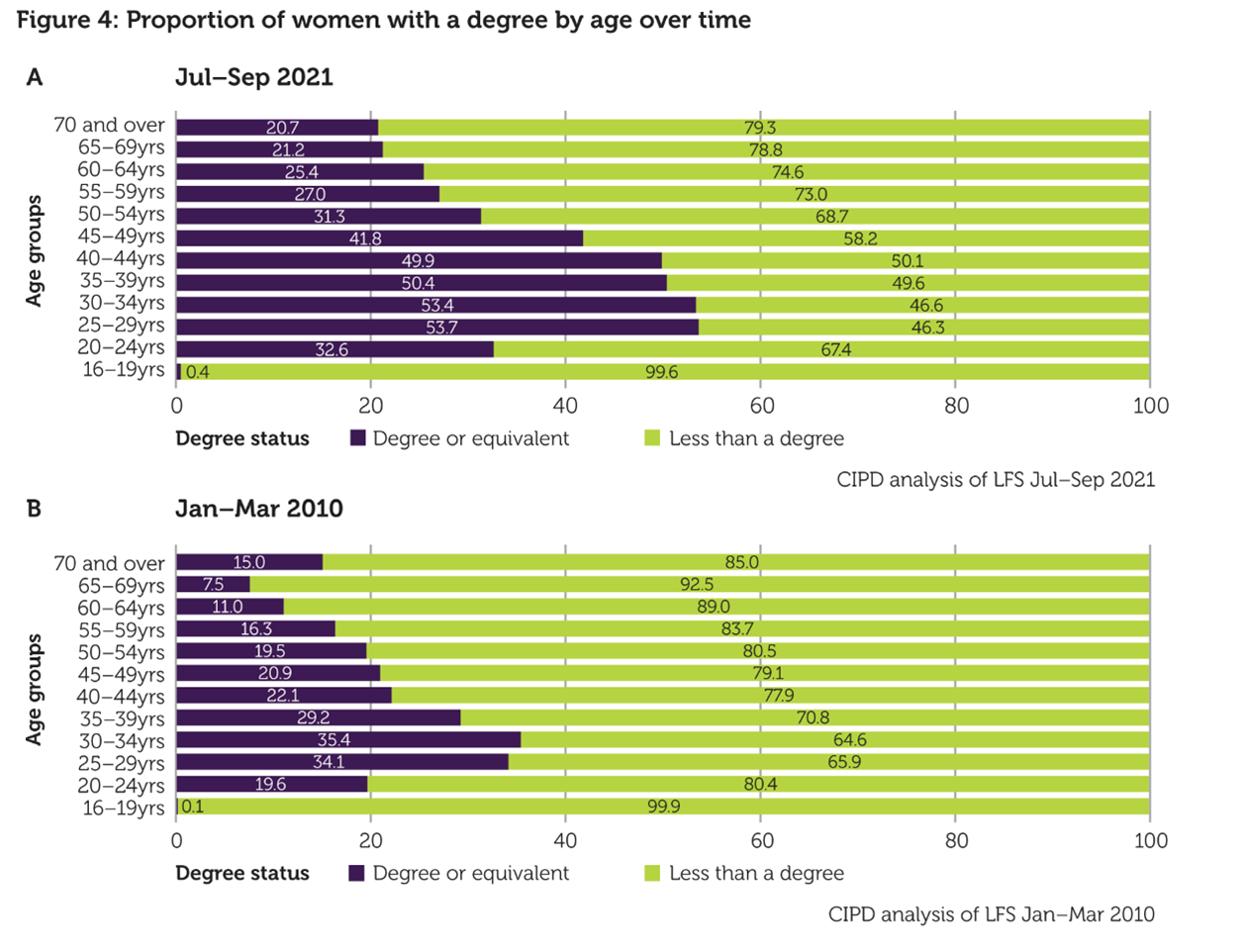

What this report finds: Women are paid 79 cents for every dollar paid to men—despite the fact that over the last several decades millions more women have joined the workforce and made huge gains in their educational attainment. Too often it is assumed that this pay gap is not evidence of discrimination, but is instead a statistical artifact of failing to adjust for factors that could drive earnings differences between men and women. However, these factors—particularly occupational differences between women and men—are themselves often affected by gender bias. For example, by the time a woman earns her first dollar, her occupational choice is the culmination of years of education, guidance by mentors, expectations set by those who raised her, hiring practices of firms, and widespread norms and expectations about work–family balance held by employers, co-workers, and society. In other words, even though women disproportionately enter lower-paid, female-dominated occupations, this decision is shaped by discrimination, societal norms, and other forces beyond women’s control.

Why it matters, and how to fix it: The gender wage gap is real—and hurts women across the board by suppressing their earnings and making it harder to balance work and family. Serious attempts to understand the gender wage gap should not include shifting the blame to women for not earning more. Rather, these attempts should examine where our economy provides unequal opportunities for women at every point of their education, training, and career choices.

Introduction and key findings

Women are paid 79 cents for every dollar paid to men (Hegewisch and DuMonthier 2016). This is despite the fact that over the last several decades millions more women have joined the workforce and made huge gains in their educational attainment.

Critics of this widely cited statistic claim it is not solid evidence of economic discrimination against women because it is unadjusted for characteristics other than gender that can affect earnings, such as years of education, work experience, and location. Many of these skeptics contend that the gender wage gap is driven not by discrimination, but instead by voluntary choices made by men and women—particularly the choice of occupation in which they work. And occupational differences certainly do matter—occupation and industry account for about half of the overall gender wage gap (Blau and Kahn 2016).

To isolate the impact of overt gender discrimination—such as a woman being paid less than her male coworker for doing the exact same job—it is typical to adjust for such characteristics. But these adjusted statistics can radically understate the potential for gender discrimination to suppress women’s earnings. This is because gender discrimination does not occur only in employers’ pay-setting practices. It can happen at every stage leading to women’s labor market outcomes.

Take one key example: occupation of employment. While controlling for occupation does indeed reduce the measured gender wage gap, the sorting of genders into different occupations can itself be driven (at least in part) by discrimination. By the time a woman earns her first dollar, her occupational choice is the culmination of years of education, guidance by mentors, expectations set by those who raised her, hiring practices of firms, and widespread norms and expectations about work–family balance held by employers, co-workers, and society. In other words, even though women disproportionately enter lower-paid, female-dominated occupations, this decision is shaped by discrimination, societal norms, and other forces beyond women’s control.

This paper explains why gender occupational sorting is itself part of the discrimination women face, examines how this sorting is shaped by societal and economic forces, and explains that gender pay gaps are present even within occupations.

Key points include:

- Gender pay gaps within occupations persist, even after accounting for years of experience, hours worked, and education.

- Decisions women make about their occupation and career do not happen in a vacuum—they are also shaped by society.

- The long hours required by the highest-paid occupations can make it difficult for women to succeed, since women tend to shoulder the majority of family caretaking duties.

- Many professions dominated by women are low paid, and professions that have become female-dominated have become lower paid.

This report examines wages on an hourly basis. Technically, this is an adjusted gender wage gap measure. As opposed to weekly or annual earnings, hourly earnings ignore the fact that men work more hours on average throughout a week or year. Thus, the hourly gender wage gap is a bit smaller than the 79 percent figure cited earlier. This minor adjustment allows for a comparison of women’s and men’s wages without assuming that women, who still shoulder a disproportionate amount of responsibilities at home, would be able or willing to work as many hours as their male counterparts. Examining the hourly gender wage gap allows for a more thorough conversation about how many factors create the wage gap women experience when they cash their paychecks.

Within-occupation gender wage gaps are large—and persist after controlling for education and other factors

Those keen on downplaying the gender wage gap often claim women voluntarily choose lower pay by disproportionately going into stereotypically female professions or by seeking out lower-paid positions. But even when men and women work in the same occupation—whether as hairdressers, cosmetologists, nurses, teachers, computer engineers, mechanical engineers, or construction workers—men make more, on average, than women (CPS microdata 2011–2015).

As a thought experiment, imagine if women’s occupational distribution mirrored men’s. For example, if 2 percent of men are carpenters, suppose 2 percent of women become carpenters. What would this do to the wage gap? After controlling for differences in education and preferences for full-time work, Goldin (2014) finds that 32 percent of the gender pay gap would be closed.

However, leaving women in their current occupations and just closing the gaps between women and their male counterparts within occupations (e.g., if male and female civil engineers made the same per hour) would close 68 percent of the gap. This means examining why waiters and waitresses, for example, with the same education and work experience do not make the same amount per hour. To quote Goldin:

Another way to measure the effect of occupation is to ask what would happen to the aggregate gender gap if one equalized earnings by gender within each occupation or, instead, evened their proportions for each occupation. The answer is that equalizing earnings within each occupation matters far more than equalizing the proportions by each occupation. (Goldin 2014)

This phenomenon is not limited to low-skilled occupations, and women cannot educate themselves out of the gender wage gap (at least in terms of broad formal credentials). Indeed, women’s educational attainment outpaces men’s; 37.0 percent of women have a college or advanced degree, as compared with 32.5 percent of men (CPS ORG 2015). Furthermore, women earn less per hour at every education level, on average. As shown in Figure A , men with a college degree make more per hour than women with an advanced degree. Likewise, men with a high school degree make more per hour than women who attended college but did not graduate. Even straight out of college, women make $4 less per hour than men—a gap that has grown since 2000 (Kroeger, Cooke, and Gould 2016).

Women earn less than men at every education level : Average hourly wages, by gender and education, 2015

| Education level | Men | Women |

|---|---|---|

| Less than high school | $13.93 | $10.89 |

| High school | $18.61 | $14.57 |

| Some college | $20.95 | $16.59 |

| College | $35.23 | $26.51 |

| Advanced degree | $45.84 | $33.65 |

The data below can be saved or copied directly into Excel.

The data underlying the figure.

Source : EPI analysis of Current Population Survey Outgoing Rotation Group microdata

Copy the code below to embed this chart on your website.

Steering women to certain educational and professional career paths—as well as outright discrimination—can lead to different occupational outcomes

The gender pay gap is driven at least in part by the cumulative impact of many instances over the course of women’s lives when they are treated differently than their male peers. Girls can be steered toward gender-normative careers from a very early age. At a time when parental influence is key, parents are often more likely to expect their sons, rather than their daughters, to work in science, technology, engineering, or mathematics (STEM) fields, even when their daughters perform at the same level in mathematics (OECD 2015).

Expectations can become a self-fulfilling prophecy. A 2005 study found third-grade girls rated their math competency scores much lower than boys’, even when these girls’ performance did not lag behind that of their male counterparts (Herbert and Stipek 2005). Similarly, in states where people were more likely to say that “women [are] better suited for home” and “math is for boys,” girls were more likely to have lower math scores and higher reading scores (Pope and Sydnor 2010). While this only establishes a correlation, there is no reason to believe gender aptitude in reading and math would otherwise be related to geography. Parental expectations can impact performance by influencing their children’s self-confidence because self-confidence is associated with higher test scores (OECD 2015).

By the time young women graduate from high school and enter college, they already evaluate their career opportunities differently than young men do. Figure B shows college freshmen’s intended majors by gender. While women have increasingly gone into medical school and continue to dominate the nursing field, women are significantly less likely to arrive at college interested in engineering, computer science, or physics, as compared with their male counterparts.

Women arrive at college less interested in STEM fields as compared with their male counterparts : Intent of first-year college students to major in select STEM fields, by gender, 2014

| Intended major | Percentage of men | Percentage of women |

|---|---|---|

| Biological and life sciences | 11% | 16% |

| Engineering | 19% | 6% |

| Chemistry | 1% | 1% |

| Computer science | 6% | 1% |

| Mathematics/ statistics | 1% | 1% |

| Physics | 1% | 0.3% |

Source: EPI adaptation of Corbett and Hill (2015) analysis of Eagan et al. (2014)

These decisions to allow doors to lucrative job opportunities to close do not take place in a vacuum. Many factors might make it difficult for a young woman to see herself working in computer science or a similarly remunerative field. A particularly depressing example is the well-publicized evidence of sexism in the tech industry (Hewlett et al. 2008). Unfortunately, tech isn’t the only STEM field with this problem.

Young women may be discouraged from certain career paths because of industry culture. Even for women who go against the grain and pursue STEM careers, if employers in the industry foster an environment hostile to women’s participation, the share of women in these occupations will be limited. One 2008 study found that “52 percent of highly qualified females working for SET [science, technology, and engineering] companies quit their jobs, driven out by hostile work environments and extreme job pressures” (Hewlett et al. 2008). Extreme job pressures are defined as working more than 100 hours per week, needing to be available 24/7, working with or managing colleagues in multiple time zones, and feeling pressure to put in extensive face time (Hewlett et al. 2008). As compared with men, more than twice as many women engage in housework on a daily basis, and women spend twice as much time caring for other household members (BLS 2015). Because of these cultural norms, women are less likely to be able to handle these extreme work pressures. In addition, 63 percent of women in SET workplaces experience sexual harassment (Hewlett et al. 2008). To make matters worse, 51 percent abandon their SET training when they quit their job. All of these factors play a role in steering women away from highly paid occupations, particularly in STEM fields.

The long hours required for some of the highest-paid occupations are incompatible with historically gendered family responsibilities

Those seeking to downplay the gender wage gap often suggest that women who work hard enough and reach the apex of their field will see the full fruits of their labor. In reality, however, the gender wage gap is wider for those with higher earnings. Women in the top 95th percentile of the wage distribution experience a much larger gender pay gap than lower-paid women.

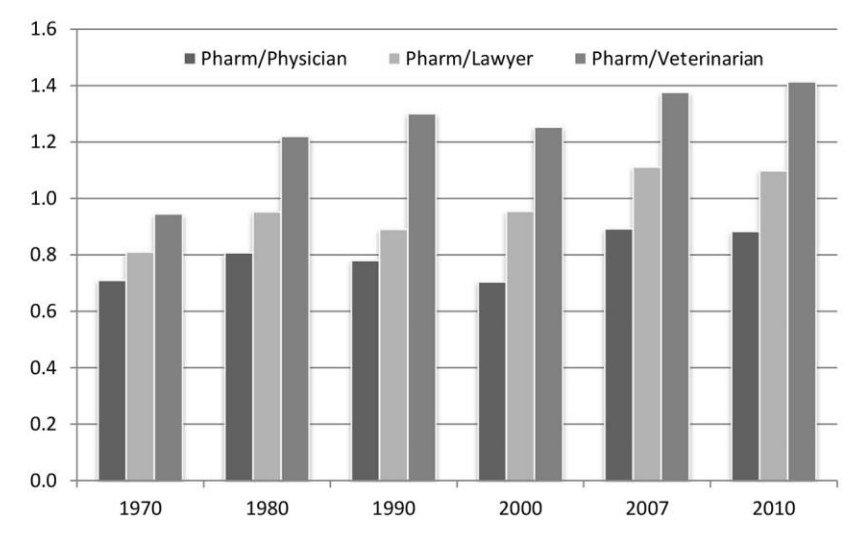

Again, this large gender pay gap between the highest earners is partially driven by gender bias. Harvard economist Claudia Goldin (2014) posits that high-wage firms have adopted pay-setting practices that disproportionately reward individuals who work very long and very particular hours. This means that even if men and women are equally productive per hour, individuals—disproportionately men—who are more likely to work excessive hours and be available at particular off-hours are paid more highly (Hersch and Stratton 2002; Goldin 2014; Landers, Rebitzer, and Taylor 1996).

It is clear why this disadvantages women. Social norms and expectations exert pressure on women to bear a disproportionate share of domestic work—particularly caring for children and elderly parents. This can make it particularly difficult for them (relative to their male peers) to be available at the drop of a hat on a Sunday evening after working a 60-hour week. To the extent that availability to work long and particular hours makes the difference between getting a promotion or seeing one’s career stagnate, women are disadvantaged.

And this disadvantage is reinforced in a vicious circle. Imagine a household where both members of a male–female couple have similarly demanding jobs. One partner’s career is likely to be prioritized if a grandparent is hospitalized or a child’s babysitter is sick. If the past history of employer pay-setting practices that disadvantage women has led to an already-existing gender wage gap for this couple, it can be seen as “rational” for this couple to prioritize the male’s career. This perpetuates the expectation that it always makes sense for women to shoulder the majority of domestic work, and further exacerbates the gender wage gap.

Female-dominated professions pay less, but it’s a chicken-and-egg phenomenon

Many women do go into low-paying female-dominated industries. Home health aides, for example, are much more likely to be women. But research suggests that women are making a logical choice, given existing constraints . This is because they will likely not see a significant pay boost if they try to buck convention and enter male-dominated occupations. Exceptions certainly exist, particularly in the civil service or in unionized workplaces (Anderson, Hegewisch, and Hayes 2015). However, if women in female-dominated occupations were to go into male-dominated occupations, they would often have similar or lower expected wages as compared with their female counterparts in female-dominated occupations (Pitts 2002). Thus, many women going into female-dominated occupations are actually situating themselves to earn higher wages. These choices thereby maximize their wages (Pitts 2002). This holds true for all categories of women except for the most educated, who are more likely to earn more in a male profession than a female profession. There is also evidence that if it becomes more lucrative for women to move into male-dominated professions, women will do exactly this (Pitts 2002). In short, occupational choice is heavily influenced by existing constraints based on gender and pay-setting across occupations.

To make matters worse, when women increasingly enter a field, the average pay in that field tends to decline, relative to other fields. Levanon, England, and Allison (2009) found that when more women entered an industry, the relative pay of that industry 10 years later was lower. Specifically, they found evidence of devaluation—meaning the proportion of women in an occupation impacts the pay for that industry because work done by women is devalued.

Computer programming is an example of a field that has shifted from being a very mixed profession, often associated with secretarial work in the past, to being a lucrative, male-dominated profession (Miller 2016; Oldenziel 1999). While computer programming has evolved into a more technically demanding occupation in recent decades, there is no skills-based reason why the field needed to become such a male-dominated profession. When men flooded the field, pay went up. In contrast, when women became park rangers, pay in that field went down (Miller 2016).

Further compounding this problem is that many professions where pay is set too low by market forces, but which clearly provide enormous social benefits when done well, are female-dominated. Key examples range from home health workers who care for seniors, to teachers and child care workers who educate today’s children. If closing gender pay differences can help boost pay and professionalism in these key sectors, it would be a huge win for the economy and society.

The gender wage gap is real—and hurts women across the board. Too often it is assumed that this gap is not evidence of discrimination, but is instead a statistical artifact of failing to adjust for factors that could drive earnings differences between men and women. However, these factors—particularly occupational differences between women and men—are themselves affected by gender bias. Serious attempts to understand the gender wage gap should not include shifting the blame to women for not earning more. Rather, these attempts should examine where our economy provides unequal opportunities for women at every point of their education, training, and career choices.

— This paper was made possible by a grant from the Peter G. Peterson Foundation. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the authors.

— The authors wish to thank Josh Bivens, Barbara Gault, and Heidi Hartman for their helpful comments.

About the authors

Jessica Schieder joined EPI in 2015. As a research assistant, she supports the research of EPI’s economists on topics such as the labor market, wage trends, executive compensation, and inequality. Prior to joining EPI, Jessica worked at the Center for Effective Government (formerly OMB Watch) as a revenue and spending policies analyst, where she examined how budget and tax policy decisions impact working families. She holds a bachelor’s degree in international political economy from Georgetown University.

Elise Gould , senior economist, joined EPI in 2003. Her research areas include wages, poverty, economic mobility, and health care. She is a co-author of The State of Working America, 12th Edition . In the past, she has authored a chapter on health in The State of Working America 2008/09; co-authored a book on health insurance coverage in retirement; published in venues such as The Chronicle of Higher Education , Challenge Magazine , and Tax Notes; and written for academic journals including Health Economics , Health Affairs, Journal of Aging and Social Policy, Risk Management & Insurance Review, Environmental Health Perspectives , and International Journal of Health Services . She holds a master’s in public affairs from the University of Texas at Austin and a Ph.D. in economics from the University of Wisconsin at Madison.

Anderson, Julie, Ariane Hegewisch, and Jeff Hayes 2015. The Union Advantage for Women . Institute for Women’s Policy Research.

Blau, Francine D., and Lawrence M. Kahn 2016. The Gender Wage Gap: Extent, Trends, and Explanations . National Bureau of Economic Research, Working Paper No. 21913.

Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS). 2015. American Time Use Survey public data series. U.S. Census Bureau.

Corbett, Christianne, and Catherine Hill. 2015. Solving the Equation: The Variables for Women’s Success in Engineering and Computing . American Association of University Women (AAUW).

Current Population Survey Outgoing Rotation Group microdata (CPS ORG). 2011–2015. Survey conducted by the Bureau of the Census for the Bureau of Labor Statistics [ machine-readable microdata file ]. U.S. Census Bureau.

Goldin, Claudia. 2014. “ A Grand Gender Convergence: Its Last Chapter .” American Economic Review, vol. 104, no. 4, 1091–1119.

Hegewisch, Ariane, and Asha DuMonthier. 2016. The Gender Wage Gap: 2015; Earnings Differences by Race and Ethnicity . Institute for Women’s Policy Research.

Herbert, Jennifer, and Deborah Stipek. 2005. “The Emergence of Gender Difference in Children’s Perceptions of Their Academic Competence.” Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology , vol. 26, no. 3, 276–295.

Hersch, Joni, and Leslie S. Stratton. 2002. “ Housework and Wages .” The Journal of Human Resources , vol. 37, no. 1, 217–229.

Hewlett, Sylvia Ann, Carolyn Buck Luce, Lisa J. Servon, Laura Sherbin, Peggy Shiller, Eytan Sosnovich, and Karen Sumberg. 2008. The Athena Factor: Reversing the Brain Drain in Science, Engineering, and Technology . Harvard Business Review.

Kroeger, Teresa, Tanyell Cooke, and Elise Gould. 2016. The Class of 2016: The Labor Market Is Still Far from Ideal for Young Graduates . Economic Policy Institute.

Landers, Renee M., James B. Rebitzer, and Lowell J. Taylor. 1996. “ Rat Race Redux: Adverse Selection in the Determination of Work Hours in Law Firms .” American Economic Review , vol. 86, no. 3, 329–348.

Levanon, Asaf, Paula England, and Paul Allison. 2009. “Occupational Feminization and Pay: Assessing Causal Dynamics Using 1950-2000 U.S. Census Data.” Social Forces, vol. 88, no. 2, 865–892.

Miller, Claire Cain. 2016. “As Women Take Over a Male-Dominated Field, the Pay Drops.” New York Times , March 18.

Oldenziel, Ruth. 1999. Making Technology Masculine: Men, Women, and Modern Machines in America, 1870-1945 . Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). 2015. The ABC of Gender Equality in Education: Aptitude, Behavior, Confidence .

Pitts, Melissa M. 2002. Why Choose Women’s Work If It Pays Less? A Structural Model of Occupational Choice. Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta, Working Paper 2002-30.

Pope, Devin G., and Justin R. Sydnor. 2010. “ Geographic Variation in the Gender Differences in Test Scores .” Journal of Economic Perspectives , vol. 24, no. 2, 95–108.

See related work on Wages, Incomes, and Wealth | Women

See more work by Jessica Schieder and Elise Gould

What Causes the Wage Gap?

By deborah rho | february 24, 2021.

This post is the fourth in a series that provides deeper context for the findings of the 2020 Status of Women and Girls in Minnesota report , a research collaboration between the Women’s Foundation of Minnesota and the Center on Women, Gender, and Public Policy . The data show that the wage gap between women and white men in Minnesota is twice as large for Hmong, Native American, and Latina women, nearly that for African American women, and 2.5 times greater for Somali women. Here, University of St. Thomas economist Deborah Rho explores the upstream racial and gender inequalities that give rise to the wage gap.

The headlines are stark: “ How the Pandemic Is Breaking Women ,” “ The Economy Could Lose a Generation of Working Mothers ” and, bluntly, “ Primal Scream .” The COVID-19 pandemic has amplified longstanding inequities in American society, with particularly alarming implications for the progress of gender equality in the labor market.

According to a study by the U.S. Census Bureau , in July 2020, one in five working-age adults said that the reason they were not working was because of the disruption of childcare arrangements due to COVID-19. Of those not working, women were nearly three times as likely as men to not be employed as a result of childcare demands. Despite progress in equality within the household, gender norms and expectations continue to contribute to differences in labor market outcomes of men and women, exemplified by the gender wage gap.

Flexibility vs. Higher Wages

Even before the pandemic, in Minnesota, women made $0.79 for every dollar made by men. While many factors contribute to the gender wage gap, including discriminatory practices , research suggests that time away from employment, occupational clustering, and the time demands of jobs explain much of the difference in wages between men and women. Traditionally, many women dropped out of the labor force for some time in their childbearing years. Though there have been significant changes in this pattern in recent decades, women often do not have the same continuity of work experience as their male counterparts, which contributes to lower wages .

Additionally, women’s expectations about their careers may affect their educational and occupational choices, which greatly affect earnings. Women are overrepresented in low-earning occupations, such as cashiers, administrative assistants, and childcare workers.

Women may be pushed into low-earning occupations through discrimination, which excludes them from higher paying occupations, or socialization, which makes them more likely to seek these jobs.

Women may be pushed into these occupations through discrimination, which excludes them from higher paying occupations, or socialization, which makes them more likely to seek these jobs. One study finds evidence of a “care penalty,” when workers in jobs that require higher levels of caregiving earn lower wages than workers with similar skills in jobs that involve less caregiving. This penalty disproportionately affects women.

Although these are important considerations, recent research suggests that the wage gap can be attributed more to differences in pay within occupation than across occupation. One study finds that only 15 percent of the gender wage gap would be eliminated if men and women were equally represented in each occupation, but 85 percent would be eliminated if they were paid equally within each occupation. This is in part because even within occupations, women disproportionately seek positions that lend themselves to family responsibilities, jobs that are more flexible in the timing of work hours and less likely to have weekend and evening obligations.

These positions pay less than more inflexible jobs within the same occupation , especially in higher paying fields such as law and finance, where employees face many deadlines, develop close relationships with clients, and work in specialized teams. In such jobs, workers are not as easily substituted for one another, which makes flexibility in the timing of work costly to the firm. Within an occupation, men are more likely than women to be willing to take a job with long and inflexible hours and receive the corresponding higher compensation.

The number of hours of work also appear to affect the hourly wages of low- and moderate-income workers. However, rather than receiving a pay premium for working long hours, workers are penalized for working fewer hours. Both men and women experience a large hourly wage penalty for working less than 40 hours a week, but women are more likely to work part-time and therefore are affected to a greater extent.

Both men and women experience a large hourly wage penalty for working less than 40 hours a week, but women are more likely to work part-time and therefore are affected to a greater extent.

To the extent that women are more likely than men to seek particular work arrangements because they are expected to take on greater family responsibilities, it is unlikely that the wage gap will be eliminated until gender equity is attained within the home. For instance, there is growing evidence that parents’ gender attitudes affect the labor supply of daughters and the women their sons marry. Even if parents do not intentionally transmit gender stereotypes within the family, children develop attitudes and norms by observing gender roles at home and in society.

Racial Pay Disparities Compound the Gender Gap

In addition to differences between men and women, a closer look at earnings reveals dramatic disparities in wages across race. Economics research has typically considered the gender wage gap separately from racial wage gaps, but this may miss important dynamics between gender and race in the labor market. While on average, a white woman in Minnesota earns $0.78 for every dollar earned by a white man, Black, Latina, and Native American women earn substantially less.

Minnesota Cents on the Dollar

Average Wage and Salary Income Relative to White Men

Source: 2020 Status of Women and Girls in Minnesota . CWGPP analysis of American Community Survey, 2013-17. Average earnings of full-time, year-round workers age 16 and over in Minnesota.

Black and brown women are not only affected by a gender wage penalty but by racial disparities in the labor market. This difference is more troublesome given that African American and Native American mothers are more likely to be the primary breadwinner in the family and more likely to be single parents.

A Significant Portion of Minnesota’s Mothers Are the Primary Breadwinner

Source: 2020 Status of Women and Girls in Minnesota . Percent of mothers with children under 18 who are either single with earned income or earn more income than their spouse or partner. CWGPP analysis of the American Community Survey, 2013-17.

There is much evidence of unfair treatment of minority workers. Researchers have conducted experiments in which they send fictitious resumes to real employers using the name of the applicant to signal race. The quality of the resume is held constant so any differences in callback rates across race can be interpreted as discrimination. One such study found that white sounding names received 50 percent more callbacks for interviews than African American sounding names. Using a similar methodology, my coauthor and I found that in the Twin Cities, employers were less likely to call back applicants with names that sounded African American or Somali American than they were to call back those that sounded white.

In the Twin Cities, employers were less likely to call back applicants with names that sounded African American or Somali American than they were to call back those that sounded white.

Experiments like these are designed to parse out whether unequal labor market outcomes are a result of employer discrimination or because of differences across groups in characteristics such as level and quality of education, which are themselves impacted by discrimination. In the United States, compared to white students, Black and Hispanic students are more likely to drop out of high school and less likely to attend college given that they graduate. Unsurprisingly, disparities in “premarket factors” such as education also contribute to income inequality.

Early Childhood Investments Can Level the Field

There are no simple solutions to these longstanding disparities. But among family policies, access to high quality early childhood programs can be one way to help address both gender and racial inequality. A growing body of research has established that early childhood environments greatly influence later life outcomes. Numerous studies show that programs that have targeted disadvantaged children in their earliest years have had large positive impacts on earnings and education. Given that children of color are more likely to be living in poverty, programs that focus on quality care and education for children of low-income families will contribute to diminishing the racial wage gap.

In addition to benefiting the children who participate, high quality early childhood programs may also be a way to support working mothers. Affordable childcare is especially important for single mothers to remain in the labor force. Unfortunately, Minnesota is the fifth least affordable state when it comes to center-based childcare. While there is mixed evidence on the impact of government subsidized childcare on maternal labor force participation in general, recent research suggests that such programs increase the employment of single mothers. The expansion of programs that have proven to be valuable to disadvantaged children could contribute to diminishing the gender wage gap by helping mothers stay in the labor market.

The pandemic has revealed the crucial role childcare plays in the careers of parents. In addressing the current crisis, policymakers have an opportunity to invest in better, more equitable early childhood spending that will have an impact for years to come.

Deborah Rho is an associate professor of economics at the University of St. Thomas.

Photo: iStock.com/chabybucko

HUMPHREY SCHOOL OF PUBLIC AFFAIRS

Center on women, gender, and public policy, quick links.

- Write for Us

- Email Sign-Up

Write For Us

- Click to Learn More

Social Media

Sign-up to receive the lastest news from the Gender Policy Report.

Understanding the gender pay gap: definition and causes

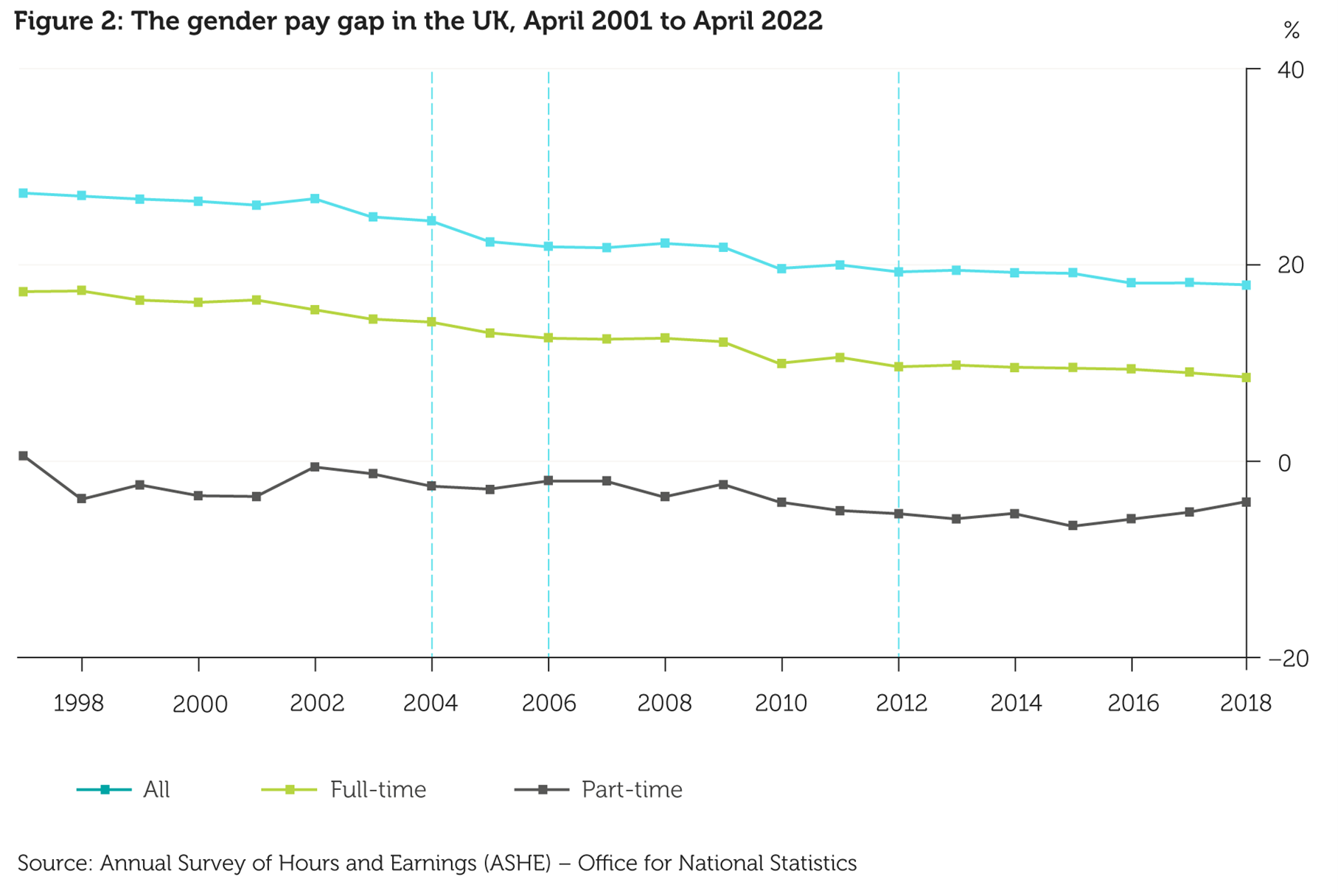

Working women in the EU earn on average 12.7% less per hour than men. Find out how this gender pay gap is calculated and the reasons behind it.

Although the equal pay for equal work principle was introduced in the Treaty of Rome in 1957, the so-called gender pay gap stubbornly persists with only marginal improvements being achieved in recent years.

What is the gender pay gap and how is it calculated?

The gender pay gap is the difference in average gross hourly earnings between women and men. It is based on salaries paid directly to employees before income tax and social security contributions are deducted. Only companies of 10 or more employees are taken into account in the calculations. The EU average gender pay gap was 12.7% in 2021 .

Some of the reasons for the gender pay gap are structural and are related to differences in employment, level of education and work experience. If we remove this part, what remains is known as the adjusted gender pay gap.

The gender pay gap in the EU

Across the EU, the pay gap differs widely , being the highest in the following countries in 2021: Estonia (20.5%), Austria (18.8%), Germany (17.6%), Hungary (17.3%) and Slovakia (16.6). Luxembourg has closed the gender pay gap. Other countries with lower gender pay gaps in 2021 are: Romania (3.6%), Slovenia (3.8%), Poland (4.5%), Italy (5.0%) and Belgium (5.0%).

Read about the European Parliament’s fight for gender equality

Interpreting the numbers is not as simple as it seems, as a smaller gender pay gap in a specific country does not necessarily mean more gender equality. In some EU countries lower pay gaps tend to be because of women having fewer paid jobs. High gaps tend to be related to a high proportion of women working part time or being concentrated in a restricted number of professions. Still, some structural causes of the gender pay gap can be identified.

Check out more data on the gender pay gap

Causes of the gender pay gap

Part-time work.

On average, women do more hours of unpaid work , such as childcare or housework.

This leaves less time for paid work. According to figures from 2020 , almost one-third of women (28%) work part-time, while only 8% of men work part-time. When both unpaid and paid work are considered, women work more hours per week than men.

Career choices influenced by family responsibilities

Women are also much more likely to be the ones who have career breaks : in 2018, a third of employed women in the EU had a work interruption for childcare reasons, compared to 1.3% of men. Some career choices made by female workers are influenced by care and family responsibilities .

More women in low-paying sectors

About 24% of the total gender pay gap can be explained by an overrepresentation of women in relatively low-paying sectors, such as care, health or education. The number of women in science, technology and engineering has increased. Women accounted for 41% of the workforce in 2021 .

Fewer and lower-paid female managers

Women also hold fewer executive positions: in 2020 they made up a third (34%) of managers in the EU, although they represent almost half of the employees. If we look at the gap in different occupations, female managers are at the greatest disadvantage: they earn 23% less per hour than male managers.

A combination of factors

Women do not only earn less per hour, but they also perform more unpaid work as well as fewer paid hours and are more likely to be unemployed than men. All these factors combined bring the difference in overall earnings between men and women to almost 37% in the EU (in 2018).

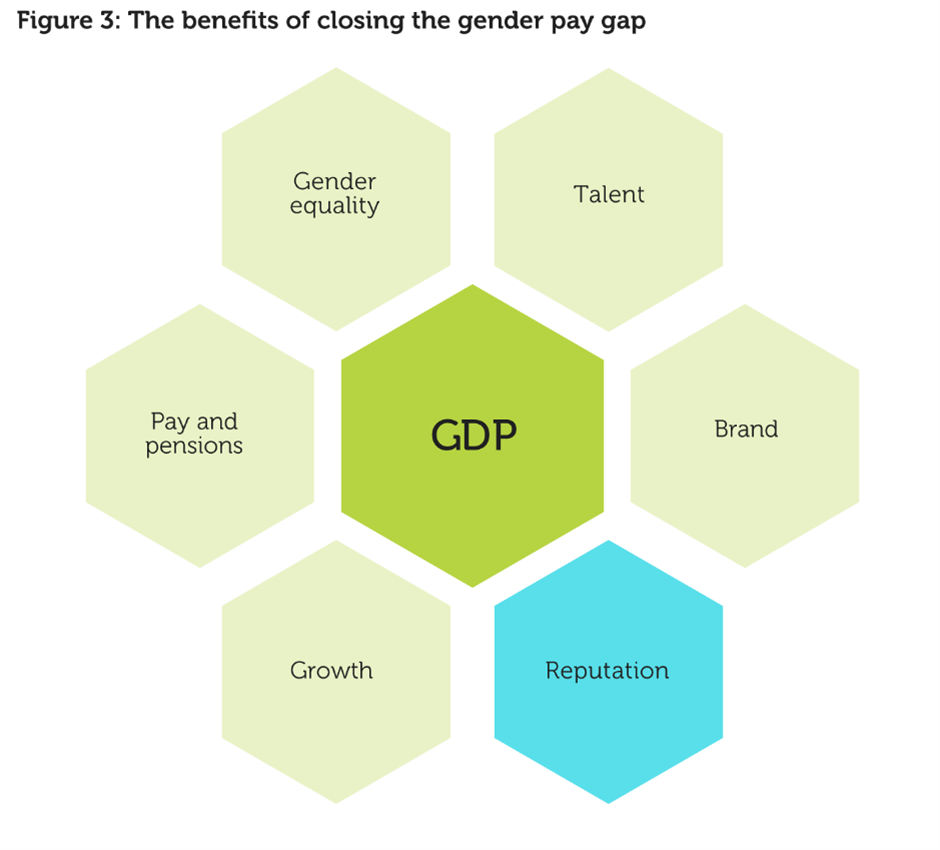

Closing the gap: the benefits

The gender pay gap increases with age throughout the career and alongside increasing family demands, while it is rather low when women enter the labour market. With less money to save and invest, these gaps accumulate and women are consequently at a higher risk of poverty and social exclusion at an older age. The gender pension gap was over 28% in the EU in 2020.

Reducing the gender pay gap creates greater gender equality while reducing poverty and stimulating the economy as women would get more to spend more. This would increase the tax base and would relieve some of the burden on welfare systems. Assessments show that reducing the gender pay gap by one percentage point would increase the gross domestic product by 0.1%.

Parliament's actions against the gender pay gap

In December 2022, negotiators from the Parliament and EU countries agreed that EU companies will be required to disclose information that makes it easier to compare salaries for those working for the same employer, helping to expose gender pay gaps. In March 2023 Parliament adopted those new rules on binding pay-transparency measures . If pay reporting shows a gender pay gap of at least 5%, employers will have to conduct a joint pay assessment in cooperation with workers’ representatives. EU countries will have to impose penalties, such as fines, for employers that infringe the rules. Vacancy notices and job titles will have to be gender neutral. The Council still has to formally approve the agreement for the rules to come into effect.

The proposal for the new rules follows the Parliament’s resolution on the EU Strategy for Gender Equality from January 2021, in which MEPs called on the Commission to draw up an ambitious new gender pay gap action plan with clear targets for EU countries to reduce the gender pay gap over the next five years.

In addition, Parliament wants to make it easier for women and girls to reach top positions and boost gender equality on corporate boards . In November 2022, MEPs approved rules, which aim to introduce transparent recruitment procedures, so that at least 40% of non-executive director posts or 33% of all director posts are occupied by the women by the end of June 2026.

Find out more about what the Parliament does to tackle the gender pay gap

Find out more about equal pay and equal opportunities

- Equal pay for equal work between men and women

- Study: women on board policies in EU countries and the effects on corporate governance

Share this article on:

- Sign up for mail updates

- PDF version

Gender Wage Gap: Causes, Impacts, and Ways to Close the Gap

- Reference work entry

- First Online: 01 January 2021

- Cite this reference work entry

- Laura Schifman 6 ,

- Rikki Oden 7 &

- Carolyn Koestner 8

Part of the book series: Encyclopedia of the UN Sustainable Development Goals ((ENUNSDG))

512 Accesses

Economy ; Equality ; Income ; Occupational segregation ; Sustainable Development Goals

Pay inequity between men and women in the same position is defined as inequal pay and is consistently found across the globe in varying degrees and in many different sectors of labor (UN 2015 ). Inequal pay within an organization or within the labor market leads to a difference in average earnings between men and women, which is defined as the gender wage gap . The European Union defines the gender wage gap as “the relative difference in the average gross hourly earnings of women and men within the economy as a whole” (European Commission 2012 ). Statistically, this difference at the time of writing means about 20% lower earnings for women or 83 cents for every US dollar earned by a man (Geiger and Parker 2018 ). This means that over the course of a 40-year career, a woman experiences a lifetime wage gap of $403,440 (NWLC 2018 ).

Introduction

Goal 5 of the United Nation Sustainable...

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

Institutional subscriptions

Aisenbrey S, Evertsson M, Grunow D (2009) Is there a career penalty for mothers’ time out? A comparison of Germany, Sweden and the United States. Soc Forces, Oxford University Press 88(2):573–605

Article Google Scholar

American Association of University Women (2016) The simple truth about the gender pay gap: AAUW. American Association of University Women. https://www.aauw.org/research/the-simple-truth-about-the-gender-pay-gap/ . Accessed 3 Jul 2018

Australian Bureau of Statistics (2017) Labor force, Australia Jan 2017. Australian Bureau of Statistics, c=AU; o=Commonwealth of Australia; ou=Australian Bureau of Statistics

Google Scholar

Badgett MVL, Lau H, Sears B, Ho D (2007) Bias in the workplace: consistent evidence of sexual orientation and gender identity discrimination. Williams Institute at the UCLA School of Law, Los Angeles

Beaman L, Duflo E, Pande R, Topalova P (2012) Female leadership raises aspirations and educational attainment for girls: a policy experiment in India. Science (New York), NIH Public Access 335(6068):582–586

Article CAS Google Scholar

Berdahl JL, Moore C (2006) Workplace harassment: double jeopardy for minority women. J Appl Psychol 91:426–436

Bershidsky L (2018) No, iceland hasn’t solved the gender pay gap – Bloomberg. Bloomberg. https://www.bloomberg.com/view/articles/2018-01-04/no-iceland-hasn-t-solved-the-gender-pay-gap . 5 July 2018

Bianchi SM, Sayer LC, Milkie MA, Robinson JP (2012) Housework: who did, does or will do it, and how much does it matter? Soc Forces, Oxford University Press 91(1):55–63

Black SE, Schanzenbach DW, Breitwieser A (2017) The recent decline in women’s labor force participation. In: Whitmore Schanzenbach D, Nunn R (eds) The 51% driving growth through women’s economic participation, Washington, DC, p 9

Blau FD, Kahn LM (2017) The gender wage gap: extent, trends, and explanations. J Econ Lit 55(3):789–865

Blickenstaff CJ (2005) Women and science careers: leaky pipeline or gender filter? Gend Educ, Taylor & Francis Group 17(4):369–386

Boris E, Nadasen P (2008) Domestic workers organize! Work USA, Wiley/Blackwell (10.1111) 11(4):413–437

Bruckmüller S, Branscombe NR (2010) The glass cliff: when and why women are selected as leaders in crisis contexts. Br J Soc Psychol 49(3):433–451

Budig MJ, England P (2001) The wage penalty for motherhood. Am Sociol Rev, American Sociological Association 66(2):204

Bureau of Labor Statistics (2018) Employed persons by detailed industry, sex, race, and Hispanic or Latino ethnicity. https://www.bls.gov/cps/cpsaat18.htm . 7 July 2018

Burke RJ, Mattis MC (2007) Women and minorities in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics: upping the numbers. Edward Elgar, Cheltenham

Book Google Scholar

Carrell S, Page M, West J (2009) Sex and science: how professor gender perpetuates the gender gap. National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge, MA

Carter ME, Franco F, Gine M (2017) Executive gender pay gaps: the roles of female risk aversion and board representation. Contemp Account Res, Wiley/Blackwell (10.1111) 34(2):1232–1264

Cech EA (2013) Ideological wage inequalities? The technical/social dualism and the gender wage gap in engineering. Soc Forces 91(4):1147–1182

Crittenden A (2002) The price of motherhood: why the most important job in the world is still the least valued. 323. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886109902173010

Croson R, Gneezy U (2009) Gender differences in preferences. J Econ Lit 47(2):448–474

Daneshvary N, Waddoups C, Wimmer BS (2009) Previous marriage and the lesbian wage premium. Ind Relat 48(3):432–453. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-232X.2009.00567.x

Desta Y (2018) The hollywood wage gap isn’t getting better – but actresses are pushing back|vanity fair. Vanity Fair. https://www.vanityfair.com/hollywood/2018/01/hollywood-wage-gap-times-up . 5 July 2018

European Commission (2012) The gender pay gap situation in the EU. https://ec.europa.eu/info/policies/justice-and-fundamental-rights/combatting-discrimination/gender-equality/equal-pay/gender-pay-gap-situation-eu_en . 3 July 2018

Geiger A, Parker K (2018) A look at gender gains and gaps in the U.S.|Pew Research Center. Pew Research Center. http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2018/03/15/for-womens-history-month-a-look-at-gender-gains-and-gaps-in-the-u-s/ . 3 July 2018

Glass C, Cook A (2016) Leading at the top: understanding women’s challenges above the glass ceiling. Leadersh Q JAI 27(1):51–63

Gneezy U, Niederle M, Rustichini A (2003) Performance in competitive environments: Gender differences. Quarterly Journal of Economics. https://doi.org/10.1162/00335530360698496

Golbeck AL, Ash A, Gray M, Gumpertz M, Jewell NP, Kettenring JR, Singer JD, Gel YR (2016) A conversation about implicit bias. Statist J IAOS, IOS Press 32(4):739–755

Goodman JM, Guendelman S, Kjerulff KH (2017) Antenatal maternity leave and childbirth using the first baby study: a propensity score analysis. Womens Health Issues 27(1):50–59. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.whi.2016.09.006

Guarino CM, Borden VMH (2017) Faculty service loads and gender: are women taking care of the academic family? Res High Educ, Springer Netherlands 58(6):672–694

Guendelman S, Goodman J, Kharrazi M, Lahiff M (2014) Work–family balance after childbirth: the association between employer-offered leave characteristics and maternity leave duration. Matern Child Health J 18(1):200–208

Hochschild A, Machung A (1989) The second shift: Working families and the revolution at home. The Second Shift: Working Parents and the Revolution at Home

Horne RM, Johnson MD, Galambos NL, Krahn HJ (2018) Time, money, or gender? Predictors of the division of household labour across life stages. Sex Roles, Springer US 78(11–12):731–743

Ilo.org. (2017) Breaking barriers: Unconscious gender bias in the workplace. [online] Available at: https://www.ilo.org/actemp/publications/WCMS_601276/lang--en/index.htm [Accessed 20 Jun 2019]

Longhi S (2017) The disability pay gap. Equality and Human Rights Commission (EHRC). Research Report Series. Available at: https://www.equalityhumanrights.com/en/pay-gaps , Manchester M4 3AQ UK

Miegroet, Helga (2019) Advancement To The Highest Faculty Ranks In Academic STEM: Explaining The Gender Gap At USU. Digitalcommons@USU. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd/6936/ . Accessed 20 Jun 2019

Muralidharan K, Sheth K (2016) Bridging education gender gaps in developing countries: the role of female teachers. J Hum Resour, University of Wisconsin Press 51(2):269–297

National Committee on Pay Equity (2018) Equal pay day. National Committee on Pay Equity. https://www.pay-equity.org/day.html . 3 July 2018

National Science Foundation, National Center for Science and Engineering Statistics (2017) Women, minorities, and persons with disabilities in science and engineering: 2017. Special Report NSF 17–310. Arlington. Available at www.nsf.gov/statistics/wmpd/

National Women’s Law Center (2018) The lifetime wage gap, state by state – NWLC. National Women’s Law Center. https://nwlc.org/resources/the-lifetime-wage-gap-state-by-state/ . 3 July 2018

Nielsen MW, Alegria S, Börjeson L, Etzkowitz H, Falk-Krzesinski HJ, Joshi A, Leahey E, Smith-Doerr L, Woolley AW, Schiebinger L (2017) Opinion: gender diversity leads to better science. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, National Academy of Sciences 114(8):1740–1742

O’Neil DA, Hopkins MM (2015) The impact of gendered organizational systems on women’s career advancement. Front Psychol, Frontiers 6:905

Olafsdottir K (2018) Iceland is the best, but still not equal. Søkelys på arbeidslivet, Universitetsforlaget 35(1–2):111–126

Oyanedel-Craver V, Cotel A, Saito L, Abu-Dalo M, Gough H, Verstraeten I (2017) Women–water Nexus for sustainable global water resources. J Water Resour Plan Manag 143(8):01817001

Palvia A, Vähämaa E, Vähämaa S (2015) Are female CEOs and chairwomen more conservative and risk averse? Evidence from the banking industry during the financial crisis. J Bus Ethics, Springer Netherlands 131(3):577–594

De Pater IE, Judge TA, Scott BA (2014) Age, Gender, and Compensation. Journal of Management Inquiry. https://doi.org/10.1177/1056492613519861

Press Association (2014) 40% of managers avoid hiring younger women to get around maternity leave. The Guardian. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/money/2014/aug/12/managers-avoid-hiring-younger-women-maternity-leave . Accessed 20 Jun 2019

Progress of the World’s Women 2015–2016 (2015) Progress of the World’s Women 2015-2016. https://doi.org/10.18356/2d5f74e3-en

Rosser SV (2004) The science glass ceiling. Routledge, New York

Schilt K, Wiswall M (2008) Before and after: gender transitions, human capital, and workplace experiences. The B.E. J Econ Anal Policy, De Gruyter 8(1). https://doi.org/10.2202/1935-1682.1862

Sears B, Mallory C (2011) Documented evidence of employment discrimination & its effects on LGBT people discrimination based on sexual orientation during the five years prior to the survey, General Social Survey, 2008

Sen A (2001) The many faces of gender inequality. The New Republic, 35–39

Smith N, Smith V, Verner M (2006) Do women in top management affect firm performance? A panel study of 2,500 Danish firms. Int J Product Perform Manag, Emerald Group Publishing Limited 55(7):569–593

Spear MG (1984) The biasing influence of pupil sex in a science marking exercise. Res Sci Technol Educ, Taylor & Francis Group 2(1):55–60

The Economist (2009) The glass ceiling. Retrieved from http://www.economist.com/node/13604240

The World Bank (2018) Labor force, female (% of total labor force)|Data. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SL.TLF.TOTL.FE.ZS?end=2017&start=1990&view=chart&year_high_desc=false . 19 Aug 2018

UN (2015) Transforming our world: The 2030 agenda for sustainable development. A/RES/70/1. United Nations General Assembly. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13398-014-0173-7.2

UN Women (2017) What does gender have to do with reducing and addressing disaster risk? UN Women. http://www.unwomen.org/en/news/stories/2017/5/compilation-women-in-disaster-risk-reduction . Accessed 20 Jun 2019

United Nations (2015) The world’s women 2015: trends and statistics|multimedia library – United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Statistics Division, New York. https://doi.org/10.18356/9789210573719

UNESCO (2018) Women in Science: The gender gap in science. UNESCO Statistics

United States Department of Labor (2018) Women’s Bureau (WB) most common occupations for women. United States Department of Labor. https://www.dol.gov/wb/stats/most_common_occupations_for_women.htm . Accessed 3 Jul 2018

Walpole B (2018) Bridging the gender wage gap. ASCE News. https://news.asce.org/bridging-the-gender-wage-gap/ . Accessed 7 July 2018

Wilson V (2015) Women are more likely to work multiple jobs than men|Economic Policy Institute. Economic Policy Institute. https://www.epi.org/publication/women-are-more-likely-to-work-multiple-jobs-than-men/ . Accessed 3 Jul 2018

Wodon QT, de la Brière B (2018) Unrealized potential: the high cost of gender inequality. World Bank, Washington, DC

Wolfers J (2015) Fewer women run big companies than men named John – The New York Times. New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2015/03/03/upshot/fewer-women-run-big-companies-than-men-named-john.html . Accessed 3 Jul 2018

World Bank (2010) World Development Indicators (WDI)

Xu Y (2015) Focusing on women in STEM: a longitudinal examination of gender-based earning gap of college graduates. J High Edu 86(4):489–523

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Biology, Boston University, Boston, MA, USA

Laura Schifman

Environmental Science and Management Department, Portland State University, Portland, OR, USA

New England Interstate, Water Pollution Control Commission, Albany, NY, USA

Carolyn Koestner

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Laura Schifman .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

European School of Sustainability Science and Research, Hamburg University of Applied Sciences, Hamburg, Germany

Walter Leal Filho

Center for Neuroscience and Cell Biology, Institute for Interdisciplinary Research, University of Coimbra, Coimbra, Portugal

Anabela Marisa Azul

Faculty of Engineering and Architecture, The University of Passo Fundo, Passo Fundo, Brazil

Luciana Brandli

The University of Passo Fundo, Passo Fundo, Brazil

Amanda Lange Salvia

International Centre for Thriving, University of Chester, Chester, UK

Section Editor information

Environmental Science and Management, Portland State University, Portland, OR, USA

Melissa Haeffner

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2021 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this entry

Cite this entry.

Schifman, L., Oden, R., Koestner, C. (2021). Gender Wage Gap: Causes, Impacts, and Ways to Close the Gap. In: Leal Filho, W., Marisa Azul, A., Brandli, L., Lange Salvia, A., Wall, T. (eds) Gender Equality. Encyclopedia of the UN Sustainable Development Goals. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-95687-9_50

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-95687-9_50

Published : 29 January 2021

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-319-95686-2

Online ISBN : 978-3-319-95687-9

eBook Packages : Earth and Environmental Science Reference Module Physical and Materials Science Reference Module Earth and Environmental Sciences

Share this entry

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Numbers, Facts and Trends Shaping Your World

Read our research on:

Full Topic List

Regions & Countries

Publications

- Our Methods

- Short Reads

- Tools & Resources

Read Our Research On:

Gender Pay Gap

Half of latinas say hispanic women’s situation has improved in the past decade and expect more gains.

Government data shows gains in education, employment and earnings for Hispanic women, but gaps with other groups remain.

For Women’s History Month, a look at gender gains – and gaps – in the U.S.

Women made up 47% of the U.S. civilian labor force in 2023, up from 30% in 1950 – but growth has stagnated.

In a Growing Share of U.S. Marriages, Husbands and Wives Earn About the Same

Among married couples in the United States, women’s financial contributions have grown steadily over the last half century. Even when earnings are similar, husbands spend more time on paid work and leisure, while wives devote more time to caregiving and housework.

When negotiating starting salaries, most U.S. women and men don’t ask for higher pay

Most U.S. workers say they did not ask for higher pay the last time they were hired for a job, according to a new Pew Research Center survey.

The Enduring Grip of the Gender Pay Gap

The difference between the earnings of men and women has barely closed in the United States in the past two decades. This gap persists even as women today are more likely than men to have graduated from college, suggesting other factors are at play such as parenthood and other family needs.

Gender pay gap in U.S. hasn’t changed much in two decades

In 2022, women earned an average of 82% of what men earned, according to a new analysis of median hourly earnings of full- and part-time workers.

What is the gender wage gap in your metropolitan area? Find out with our pay gap calculator

In 2019 women in the United States earned 82% of what men earned, according to a Pew Research Center analysis of median annual earnings of full-time, year-round workers. The gender wage gap varies by age and metropolitan area, and in most places, has narrowed since 2000. See how women’s wages compare with men’s in your metro area.

Some gender disparities widened in the U.S. workforce during the pandemic

Among adults 25 and older who have no education beyond high school, more women have left the labor force than men.

Despite the pandemic, wage growth held firm for most U.S. workers, with little effect on inequality

Earnings overall have held steady through the pandemic in part because lower-wage workers experienced steeper job losses.

Key findings on gains made by women amid a rising demand for skilled workers

There is a growing need for high-skill workers in the U.S., and this has helped to narrow gender disparities in the labor market.

REFINE YOUR SELECTION

Research teams.

1615 L St. NW, Suite 800 Washington, DC 20036 USA (+1) 202-419-4300 | Main (+1) 202-857-8562 | Fax (+1) 202-419-4372 | Media Inquiries

Research Topics

- Email Newsletters

ABOUT PEW RESEARCH CENTER Pew Research Center is a nonpartisan fact tank that informs the public about the issues, attitudes and trends shaping the world. It conducts public opinion polling, demographic research, media content analysis and other empirical social science research. Pew Research Center does not take policy positions. It is a subsidiary of The Pew Charitable Trusts .

© 2024 Pew Research Center

- Submit content

- Subscribe to content

- Orientation

- Participate

The Gender Pay Gap: Understanding the Economic and Social Causes and Consequences

Related content.

| Perspective: | Feminist Economics |

|---|---|

| Topic: | Labour & Care, Race & Gender |

| Format: | Teaching Material |

| Link: |

The gender pay gap is a pressing issue that affects individuals and society as a whole, so it is important for economics students to understand it. Despite recent progress, women still earn less than men for the same jobs, leading to economic inequalities and reduced efficiency (see, for example, the recent report released by Moody’s ). Understanding the causes and consequences of the gender pay gap is critical in developing policies that promote fairness and equality.

These teaching packs are designed for 30-minute (online or offline) sessions that can be included within any lecture or tutorial class. They are designed to be suitable for university students, but could easily be adapted for higher or lower levels. Every month, we will publish at least one exercise that you can use to engage your students with current events. The main aims of these exercises are to give students practice in relating economic ideas to the real world and their own lived experiences.

Newspaper articles or videos are used as the entry point to an economic topic, which is then expanded upon by the instructor before the students are broken into small groups to engage in an activity. This will help students to develop the skills required to work as economists in the real world, and all the materials you need are provided for you. These teaching packs are published as creative commons (CC BY) and can be freely used and adopted.

Download PowerPoint Slides

You can request the Instructor's Guide on the Economy Studies Website.

Comment from our editors:

This teaching material was designed by Economy Studies and is part of the "This Month in the Economy Exercises" series. Further information on the gender pay gap in Germany and on labour law can be found here .

Go to: The Gender Pay Gap: Understanding the Economic and Social Causes and Consequences

This project is brought to you by the Network for Pluralist Economics ( Netzwerk Plurale Ökonomik e.V. ). It is committed to diversity and independence and is dependent on donations from people like you. Regular or one-off donations would be greatly appreciated.

Economic Inequality by Gender

How big are the inequalities in pay, jobs, and wealth between men and women? What causes these differences?

By: Esteban Ortiz-Ospina , Joe Hasell and Max Roser

This page was first published in March 2018 and last revised in March 2024.

On this page, you can find writing, visualizations, and data on how big the inequalities in pay, jobs, and wealth are between men and women, how they have changed over time, and what may be causing them

Although economic gender inequalities remain common and large, they are today smaller than they used to be some decades ago.

Related topics

Women's Employment

How does women’s labor force participation differ across countries? How has it changed over time? What is behind these differences and changes?

Women’s Rights

How has the protection of women’s rights changed over time? How does it differ across countries? Explore global data and research on women’s rights.

Maternal Mortality

What could be more tragic than a mother losing her life in the moment that she is giving birth to her newborn? Why are mothers dying and what can be done to prevent these deaths?

See all interactive charts on economic inequality by gender ↓

How does the gender pay gap look like across countries and over time?

The 'gender pay gap' comes up often in political debates , policy reports , and everyday news . But what is it? What does it tell us? Is it different from country to country? How does it change over time?

Here we try to answer these questions, providing an empirical overview of the gender pay gap across countries and over time.

The gender pay gap measures inequality but not necessarily discrimination

The gender pay gap (or the gender wage gap) is a metric that tells us the difference in pay (or wages, or income) between women and men. It's a measure of inequality and captures a concept that is broader than the concept of equal pay for equal work.

Differences in pay between men and women capture differences along many possible dimensions, including worker education, experience, and occupation. When the gender pay gap is calculated by comparing all male workers to all female workers – irrespective of differences along these additional dimensions – the result is the 'raw' or 'unadjusted' pay gap. On the contrary, when the gap is calculated after accounting for underlying differences in education, experience, etc., then the result is the 'adjusted' pay gap.

Discrimination in hiring practices can exist in the absence of pay gaps – for example, if women know they will be treated unfairly and hence choose not to participate in the labor market. Similarly, it is possible to observe large pay gaps in the absence of discrimination in hiring practices – for example, if women get fair treatment but apply for lower-paid jobs.

The implication is that observing differences in pay between men and women is neither necessary nor sufficient to prove discrimination in the workplace. Both discrimination and inequality are important. But they are not the same.

In most countries, there is a substantial gender pay gap

Cross-country data on the gender pay gap is patchy, but the most complete source in terms of coverage is the United Nation's International Labour Organization (ILO). The visualization here presents this data. You can add observations by clicking on the option 'add country' at the bottom of the chart.

The estimates shown here correspond to differences between the average hourly earnings of men and women (expressed as a percentage of average hourly earnings of men), and cover all workers irrespective of whether they work full-time or part-time. 1

As we can see: (i) in most countries the gap is positive – women earn less than men, and (ii) there are large differences in the size of this gap across countries. 2

In most countries, the gender pay gap has decreased in the last couple of decades

How is the gender pay gap changing over time? To answer this question, let's consider this chart showing available estimates from the OECD. These estimates include OECD member states, as well as some other non-member countries, and they are the longest available series of cross-country data on the gender pay gap that we are aware of.

Here we see that the gap is large in most OECD countries, but it has been going down in the last couple of decades. In some cases the reduction is remarkable. In the United States, for example, the gap declined by more than half.

These estimates are not directly comparable to those from the ILO, because the pay gap is measured slightly differently here: The OECD estimates refer to percent differences in median earnings (i.e. the gap here captures differences between men and women in the middle of the earnings distribution), and they cover only full-time employees and self-employed workers (i.e. the gap here excludes disparities that arise from differences in hourly wages for part-time and full-time workers).

However, the ILO data shows similar trends.

The conclusion is that in most countries with available data, the gender pay gap has decreased in the last couple of decades.

The gender pay gap is larger for older workers

The United States Census Bureau defines the pay gap as the ratio between median wages – that is, they measure the gap by calculating the wages of men and women at the middle of the earnings distribution, and dividing them.

By this measure, the gender wage gap is expressed as a percent (median earnings of women as a share of median earnings of men) and it is always positive. Here, values below 100% mean that women earn less than men, while values above 100% mean that women earn more. Values closer to 100% reflect a lower gap.

The next chart shows available estimates of this metric for full-time workers in the US, by age group.

First, we see that the series trends upwards, meaning the gap has been shrinking in the last couple of decades. Secondly, we see that there are important differences by age.

The second point is crucial to understanding the gender pay gap: the gap is a statistic that changes during the life of a worker. In most rich countries, it’s small when formal education ends and employment begins, and it increases with age. As we discuss in our analysis of the determinants below, the gender pay gap tends to increase when women marry and when/if they have children.

The gender pay gap is smaller in middle-income countries – which tend to be countries with low labor force participation of women

The chart here plots available ILO estimates on the gender pay gap against GDP per capita. As we can see there is a weak positive correlation between GDP per capita and the gender pay gap. However, the chart shows that the relationship is not really linear. Actually, middle-income countries tend to have the smallest pay gap.

The fact that middle-income countries have low gender wage gaps is, to a large extent, the result of selection of women into employment . Olivetti and Petrongolo (2008) explain it as follows: “[I]f women who are employed tend to have relatively high‐wage characteristics, low female employment rates may become consistent with low gender wage gaps simply because low‐wage women would not feature in the observed wage distribution.” 3

Olivetti and Petrongolo (2008) show that this pattern holds in the data: unadjusted gender wage gaps across countries tend to be negatively correlated with gender employment gaps. That is, the gender pay gaps tend to be smaller where relatively fewer women participate in the labor force .

So, rather than reflect greater equality, the lower wage gaps observed in some countries could indicate that only women with certain characteristics – for instance, with no husband or children – are entering the workforce.

Why is there a gender pay gap?

In almost all countries, if you compare the wages of men and women you find that women tend to earn less than men. These inequalities have been narrowing across the world. In particular, most high-income countries have seen sizeable reductions in the gender pay gap over the last couple of decades.

How did these reductions come about and why do substantial gaps remain?

Before we get into the details, here is a preview of the main points.

- An important part of the reduction in the gender pay gap in rich countries over the last decades is due to a historical narrowing, and often even reversal of the education gap between men and women.

- Today, education is relatively unimportant in explaining the remaining gender pay gap in rich countries. In contrast, the characteristics of the jobs that women tend to do, remain important contributing factors.

- The gender pay gap is not a direct metric of discrimination. However, evidence from different contexts suggests discrimination is indeed important to understand the gender pay gap. Similarly, social norms affecting the gender distribution of labor are important determinants of wage inequality.

- On the other hand, the available evidence suggests differences in psychological attributes and non-cognitive skills are at best modest factors contributing to the gender pay gap.

Differences in human capital

The adjusted pay gap.