The Research Gap (Literature Gap)

Everything you need to know to find a quality research gap

By: Ethar Al-Saraf (PhD) | Expert Reviewed By: Eunice Rautenbach (DTech) | November 2022

If you’re just starting out in research, chances are you’ve heard about the elusive research gap (also called a literature gap). In this post, we’ll explore the tricky topic of research gaps. We’ll explain what a research gap is, look at the four most common types of research gaps, and unpack how you can go about finding a suitable research gap for your dissertation, thesis or research project.

Overview: Research Gap 101

- What is a research gap

- Four common types of research gaps

- Practical examples

- How to find research gaps

- Recap & key takeaways

What (exactly) is a research gap?

Well, at the simplest level, a research gap is essentially an unanswered question or unresolved problem in a field, which reflects a lack of existing research in that space. Alternatively, a research gap can also exist when there’s already a fair deal of existing research, but where the findings of the studies pull in different directions , making it difficult to draw firm conclusions.

For example, let’s say your research aims to identify the cause (or causes) of a particular disease. Upon reviewing the literature, you may find that there’s a body of research that points toward cigarette smoking as a key factor – but at the same time, a large body of research that finds no link between smoking and the disease. In that case, you may have something of a research gap that warrants further investigation.

Now that we’ve defined what a research gap is – an unanswered question or unresolved problem – let’s look at a few different types of research gaps.

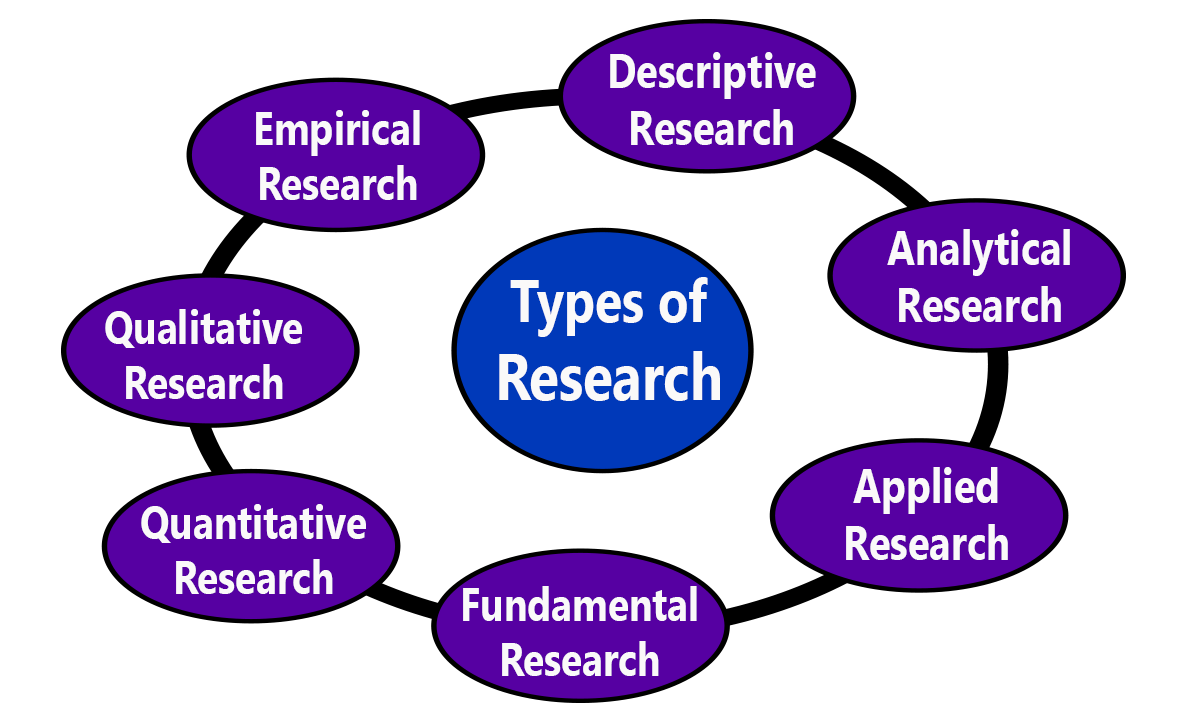

Types of research gaps

While there are many different types of research gaps, the four most common ones we encounter when helping students at Grad Coach are as follows:

- The classic literature gap

- The disagreement gap

- The contextual gap, and

- The methodological gap

Need a helping hand?

1. The Classic Literature Gap

First up is the classic literature gap. This type of research gap emerges when there’s a new concept or phenomenon that hasn’t been studied much, or at all. For example, when a social media platform is launched, there’s an opportunity to explore its impacts on users, how it could be leveraged for marketing, its impact on society, and so on. The same applies for new technologies, new modes of communication, transportation, etc.

Classic literature gaps can present exciting research opportunities , but a drawback you need to be aware of is that with this type of research gap, you’ll be exploring completely new territory . This means you’ll have to draw on adjacent literature (that is, research in adjacent fields) to build your literature review, as there naturally won’t be very many existing studies that directly relate to the topic. While this is manageable, it can be challenging for first-time researchers, so be careful not to bite off more than you can chew.

2. The Disagreement Gap

As the name suggests, the disagreement gap emerges when there are contrasting or contradictory findings in the existing research regarding a specific research question (or set of questions). The hypothetical example we looked at earlier regarding the causes of a disease reflects a disagreement gap.

Importantly, for this type of research gap, there needs to be a relatively balanced set of opposing findings . In other words, a situation where 95% of studies find one result and 5% find the opposite result wouldn’t quite constitute a disagreement in the literature. Of course, it’s hard to quantify exactly how much weight to give to each study, but you’ll need to at least show that the opposing findings aren’t simply a corner-case anomaly .

3. The Contextual Gap

The third type of research gap is the contextual gap. Simply put, a contextual gap exists when there’s already a decent body of existing research on a particular topic, but an absence of research in specific contexts .

For example, there could be a lack of research on:

- A specific population – perhaps a certain age group, gender or ethnicity

- A geographic area – for example, a city, country or region

- A certain time period – perhaps the bulk of the studies took place many years or even decades ago and the landscape has changed.

The contextual gap is a popular option for dissertations and theses, especially for first-time researchers, as it allows you to develop your research on a solid foundation of existing literature and potentially even use existing survey measures.

Importantly, if you’re gonna go this route, you need to ensure that there’s a plausible reason why you’d expect potential differences in the specific context you choose. If there’s no reason to expect different results between existing and new contexts, the research gap wouldn’t be well justified. So, make sure that you can clearly articulate why your chosen context is “different” from existing studies and why that might reasonably result in different findings.

4. The Methodological Gap

Last but not least, we have the methodological gap. As the name suggests, this type of research gap emerges as a result of the research methodology or design of existing studies. With this approach, you’d argue that the methodology of existing studies is lacking in some way , or that they’re missing a certain perspective.

For example, you might argue that the bulk of the existing research has taken a quantitative approach, and therefore there is a lack of rich insight and texture that a qualitative study could provide. Similarly, you might argue that existing studies have primarily taken a cross-sectional approach , and as a result, have only provided a snapshot view of the situation – whereas a longitudinal approach could help uncover how constructs or variables have evolved over time.

Practical Examples

Let’s take a look at some practical examples so that you can see how research gaps are typically expressed in written form. Keep in mind that these are just examples – not actual current gaps (we’ll show you how to find these a little later!).

Context: Healthcare

Despite extensive research on diabetes management, there’s a research gap in terms of understanding the effectiveness of digital health interventions in rural populations (compared to urban ones) within Eastern Europe.

Context: Environmental Science

While a wealth of research exists regarding plastic pollution in oceans, there is significantly less understanding of microplastic accumulation in freshwater ecosystems like rivers and lakes, particularly within Southern Africa.

Context: Education

While empirical research surrounding online learning has grown over the past five years, there remains a lack of comprehensive studies regarding the effectiveness of online learning for students with special educational needs.

As you can see in each of these examples, the author begins by clearly acknowledging the existing research and then proceeds to explain where the current area of lack (i.e., the research gap) exists.

How To Find A Research Gap

Now that you’ve got a clearer picture of the different types of research gaps, the next question is of course, “how do you find these research gaps?” .

Well, we cover the process of how to find original, high-value research gaps in a separate post . But, for now, I’ll share a basic two-step strategy here to help you find potential research gaps.

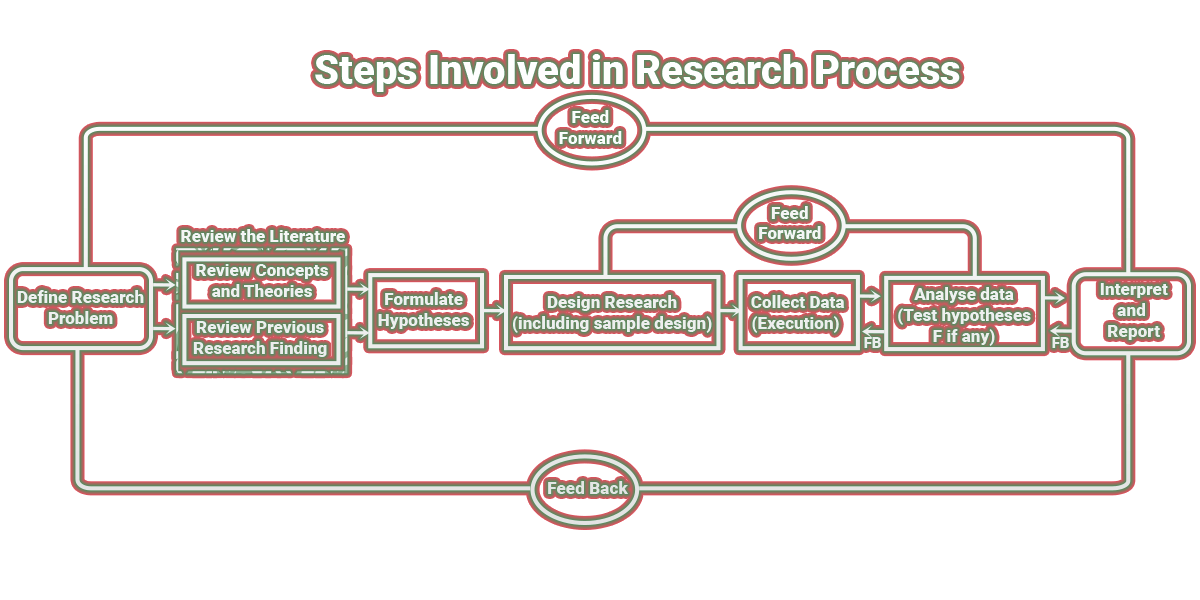

As a starting point, you should find as many literature reviews, systematic reviews and meta-analyses as you can, covering your area of interest. Additionally, you should dig into the most recent journal articles to wrap your head around the current state of knowledge. It’s also a good idea to look at recent dissertations and theses (especially doctoral-level ones). Dissertation databases such as ProQuest, EBSCO and Open Access are a goldmine for this sort of thing. Importantly, make sure that you’re looking at recent resources (ideally those published in the last year or two), or the gaps you find might have already been plugged by other researchers.

Once you’ve gathered a meaty collection of resources, the section that you really want to focus on is the one titled “ further research opportunities ” or “further research is needed”. In this section, the researchers will explicitly state where more studies are required – in other words, where potential research gaps may exist. You can also look at the “ limitations ” section of the studies, as this will often spur ideas for methodology-based research gaps.

By following this process, you’ll orient yourself with the current state of research , which will lay the foundation for you to identify potential research gaps. You can then start drawing up a shortlist of ideas and evaluating them as candidate topics . But remember, make sure you’re looking at recent articles – there’s no use going down a rabbit hole only to find that someone’s already filled the gap 🙂

Let’s Recap

We’ve covered a lot of ground in this post. Here are the key takeaways:

- A research gap is an unanswered question or unresolved problem in a field, which reflects a lack of existing research in that space.

- The four most common types of research gaps are the classic literature gap, the disagreement gap, the contextual gap and the methodological gap.

- To find potential research gaps, start by reviewing recent journal articles in your area of interest, paying particular attention to the FRIN section .

If you’re keen to learn more about research gaps and research topic ideation in general, be sure to check out the rest of the Grad Coach Blog . Alternatively, if you’re looking for 1-on-1 support with your dissertation, thesis or research project, be sure to check out our private coaching service .

Psst... there’s more!

This post was based on one of our popular Research Bootcamps . If you're working on a research project, you'll definitely want to check this out ...

You Might Also Like:

38 Comments

This post is REALLY more than useful, Thank you very very much

Very helpful specialy, for those who are new for writing a research! So thank you very much!!

I found it very helpful article. Thank you.

it very good but what need to be clear with the concept is when di we use research gap before we conduct aresearch or after we finished it ,or are we propose it to be solved or studied or to show that we are unable to cover so that we let it to be studied by other researchers ?

Just at the time when I needed it, really helpful.

Very helpful and well-explained. Thank you

VERY HELPFUL

We’re very grateful for your guidance, indeed we have been learning a lot from you , so thank you abundantly once again.

hello brother could you explain to me this question explain the gaps that researchers are coming up with ?

Am just starting to write my research paper. your publication is very helpful. Thanks so much

How to cite the author of this?

your explanation very help me for research paper. thank you

Very important presentation. Thanks.

Very helpful indeed

Best Ideas. Thank you.

I found it’s an excellent blog to get more insights about the Research Gap. I appreciate it!

Kindly explain to me how to generate good research objectives.

This is very helpful, thank you

How to tabulate research gap

Very helpful, thank you.

Thanks a lot for this great insight!

This is really helpful indeed!

This article is really helpfull in discussing how will we be able to define better a research problem of our interest. Thanks so much.

Reading this just in good time as i prepare the proposal for my PhD topic defense.

Very helpful Thanks a lot.

Thank you very much

This was very timely. Kudos

Great one! Thank you all.

Thank you very much.

This is so enlightening. Disagreement gap. Thanks for the insight.

How do I Cite this document please?

Research gap about career choice given me Example bro?

I found this information so relevant as I am embarking on a Masters Degree. Thank you for this eye opener. It make me feel I can work diligently and smart on my research proposal.

This is very helpful to beginners of research. You have good teaching strategy that use favorable language that limit everyone from being bored. Kudos!!!!!

This plat form is very useful under academic arena therefore im stil learning a lot of informations that will help to reduce the burden during development of my PhD thesis

This information is beneficial to me.

Insightful…

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates

How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates

Published on January 2, 2023 by Shona McCombes . Revised on September 11, 2023.

What is a literature review? A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources on a specific topic. It provides an overview of current knowledge, allowing you to identify relevant theories, methods, and gaps in the existing research that you can later apply to your paper, thesis, or dissertation topic .

There are five key steps to writing a literature review:

- Search for relevant literature

- Evaluate sources

- Identify themes, debates, and gaps

- Outline the structure

- Write your literature review

A good literature review doesn’t just summarize sources—it analyzes, synthesizes , and critically evaluates to give a clear picture of the state of knowledge on the subject.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

What is the purpose of a literature review, examples of literature reviews, step 1 – search for relevant literature, step 2 – evaluate and select sources, step 3 – identify themes, debates, and gaps, step 4 – outline your literature review’s structure, step 5 – write your literature review, free lecture slides, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions, introduction.

- Quick Run-through

- Step 1 & 2

When you write a thesis , dissertation , or research paper , you will likely have to conduct a literature review to situate your research within existing knowledge. The literature review gives you a chance to:

- Demonstrate your familiarity with the topic and its scholarly context

- Develop a theoretical framework and methodology for your research

- Position your work in relation to other researchers and theorists

- Show how your research addresses a gap or contributes to a debate

- Evaluate the current state of research and demonstrate your knowledge of the scholarly debates around your topic.

Writing literature reviews is a particularly important skill if you want to apply for graduate school or pursue a career in research. We’ve written a step-by-step guide that you can follow below.

Here's why students love Scribbr's proofreading services

Discover proofreading & editing

Writing literature reviews can be quite challenging! A good starting point could be to look at some examples, depending on what kind of literature review you’d like to write.

- Example literature review #1: “Why Do People Migrate? A Review of the Theoretical Literature” ( Theoretical literature review about the development of economic migration theory from the 1950s to today.)

- Example literature review #2: “Literature review as a research methodology: An overview and guidelines” ( Methodological literature review about interdisciplinary knowledge acquisition and production.)

- Example literature review #3: “The Use of Technology in English Language Learning: A Literature Review” ( Thematic literature review about the effects of technology on language acquisition.)

- Example literature review #4: “Learners’ Listening Comprehension Difficulties in English Language Learning: A Literature Review” ( Chronological literature review about how the concept of listening skills has changed over time.)

You can also check out our templates with literature review examples and sample outlines at the links below.

Download Word doc Download Google doc

Before you begin searching for literature, you need a clearly defined topic .

If you are writing the literature review section of a dissertation or research paper, you will search for literature related to your research problem and questions .

Make a list of keywords

Start by creating a list of keywords related to your research question. Include each of the key concepts or variables you’re interested in, and list any synonyms and related terms. You can add to this list as you discover new keywords in the process of your literature search.

- Social media, Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, Snapchat, TikTok

- Body image, self-perception, self-esteem, mental health

- Generation Z, teenagers, adolescents, youth

Search for relevant sources

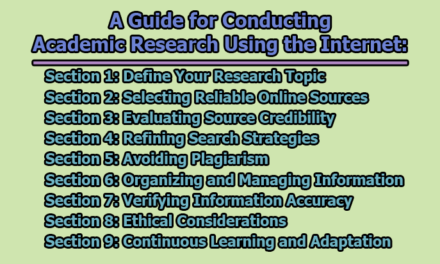

Use your keywords to begin searching for sources. Some useful databases to search for journals and articles include:

- Your university’s library catalogue

- Google Scholar

- Project Muse (humanities and social sciences)

- Medline (life sciences and biomedicine)

- EconLit (economics)

- Inspec (physics, engineering and computer science)

You can also use boolean operators to help narrow down your search.

Make sure to read the abstract to find out whether an article is relevant to your question. When you find a useful book or article, you can check the bibliography to find other relevant sources.

You likely won’t be able to read absolutely everything that has been written on your topic, so it will be necessary to evaluate which sources are most relevant to your research question.

For each publication, ask yourself:

- What question or problem is the author addressing?

- What are the key concepts and how are they defined?

- What are the key theories, models, and methods?

- Does the research use established frameworks or take an innovative approach?

- What are the results and conclusions of the study?

- How does the publication relate to other literature in the field? Does it confirm, add to, or challenge established knowledge?

- What are the strengths and weaknesses of the research?

Make sure the sources you use are credible , and make sure you read any landmark studies and major theories in your field of research.

You can use our template to summarize and evaluate sources you’re thinking about using. Click on either button below to download.

Take notes and cite your sources

As you read, you should also begin the writing process. Take notes that you can later incorporate into the text of your literature review.

It is important to keep track of your sources with citations to avoid plagiarism . It can be helpful to make an annotated bibliography , where you compile full citation information and write a paragraph of summary and analysis for each source. This helps you remember what you read and saves time later in the process.

To begin organizing your literature review’s argument and structure, be sure you understand the connections and relationships between the sources you’ve read. Based on your reading and notes, you can look for:

- Trends and patterns (in theory, method or results): do certain approaches become more or less popular over time?

- Themes: what questions or concepts recur across the literature?

- Debates, conflicts and contradictions: where do sources disagree?

- Pivotal publications: are there any influential theories or studies that changed the direction of the field?

- Gaps: what is missing from the literature? Are there weaknesses that need to be addressed?

This step will help you work out the structure of your literature review and (if applicable) show how your own research will contribute to existing knowledge.

- Most research has focused on young women.

- There is an increasing interest in the visual aspects of social media.

- But there is still a lack of robust research on highly visual platforms like Instagram and Snapchat—this is a gap that you could address in your own research.

There are various approaches to organizing the body of a literature review. Depending on the length of your literature review, you can combine several of these strategies (for example, your overall structure might be thematic, but each theme is discussed chronologically).

Chronological

The simplest approach is to trace the development of the topic over time. However, if you choose this strategy, be careful to avoid simply listing and summarizing sources in order.

Try to analyze patterns, turning points and key debates that have shaped the direction of the field. Give your interpretation of how and why certain developments occurred.

If you have found some recurring central themes, you can organize your literature review into subsections that address different aspects of the topic.

For example, if you are reviewing literature about inequalities in migrant health outcomes, key themes might include healthcare policy, language barriers, cultural attitudes, legal status, and economic access.

Methodological

If you draw your sources from different disciplines or fields that use a variety of research methods , you might want to compare the results and conclusions that emerge from different approaches. For example:

- Look at what results have emerged in qualitative versus quantitative research

- Discuss how the topic has been approached by empirical versus theoretical scholarship

- Divide the literature into sociological, historical, and cultural sources

Theoretical

A literature review is often the foundation for a theoretical framework . You can use it to discuss various theories, models, and definitions of key concepts.

You might argue for the relevance of a specific theoretical approach, or combine various theoretical concepts to create a framework for your research.

Like any other academic text , your literature review should have an introduction , a main body, and a conclusion . What you include in each depends on the objective of your literature review.

The introduction should clearly establish the focus and purpose of the literature review.

Depending on the length of your literature review, you might want to divide the body into subsections. You can use a subheading for each theme, time period, or methodological approach.

As you write, you can follow these tips:

- Summarize and synthesize: give an overview of the main points of each source and combine them into a coherent whole

- Analyze and interpret: don’t just paraphrase other researchers — add your own interpretations where possible, discussing the significance of findings in relation to the literature as a whole

- Critically evaluate: mention the strengths and weaknesses of your sources

- Write in well-structured paragraphs: use transition words and topic sentences to draw connections, comparisons and contrasts

In the conclusion, you should summarize the key findings you have taken from the literature and emphasize their significance.

When you’ve finished writing and revising your literature review, don’t forget to proofread thoroughly before submitting. Not a language expert? Check out Scribbr’s professional proofreading services !

This article has been adapted into lecture slides that you can use to teach your students about writing a literature review.

Scribbr slides are free to use, customize, and distribute for educational purposes.

Open Google Slides Download PowerPoint

If you want to know more about the research process , methodology , research bias , or statistics , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Sampling methods

- Simple random sampling

- Stratified sampling

- Cluster sampling

- Likert scales

- Reproducibility

Statistics

- Null hypothesis

- Statistical power

- Probability distribution

- Effect size

- Poisson distribution

Research bias

- Optimism bias

- Cognitive bias

- Implicit bias

- Hawthorne effect

- Anchoring bias

- Explicit bias

A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources (such as books, journal articles, and theses) related to a specific topic or research question .

It is often written as part of a thesis, dissertation , or research paper , in order to situate your work in relation to existing knowledge.

There are several reasons to conduct a literature review at the beginning of a research project:

- To familiarize yourself with the current state of knowledge on your topic

- To ensure that you’re not just repeating what others have already done

- To identify gaps in knowledge and unresolved problems that your research can address

- To develop your theoretical framework and methodology

- To provide an overview of the key findings and debates on the topic

Writing the literature review shows your reader how your work relates to existing research and what new insights it will contribute.

The literature review usually comes near the beginning of your thesis or dissertation . After the introduction , it grounds your research in a scholarly field and leads directly to your theoretical framework or methodology .

A literature review is a survey of credible sources on a topic, often used in dissertations , theses, and research papers . Literature reviews give an overview of knowledge on a subject, helping you identify relevant theories and methods, as well as gaps in existing research. Literature reviews are set up similarly to other academic texts , with an introduction , a main body, and a conclusion .

An annotated bibliography is a list of source references that has a short description (called an annotation ) for each of the sources. It is often assigned as part of the research process for a paper .

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

McCombes, S. (2023, September 11). How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates. Scribbr. Retrieved July 8, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/dissertation/literature-review/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, what is a theoretical framework | guide to organizing, what is a research methodology | steps & tips, how to write a research proposal | examples & templates, get unlimited documents corrected.

✔ Free APA citation check included ✔ Unlimited document corrections ✔ Specialized in correcting academic texts

- Privacy Policy

Home » Research Gap – Types, Examples and How to Identify

Research Gap – Types, Examples and How to Identify

Table of Contents

Research Gap

Definition:

Research gap refers to an area or topic within a field of study that has not yet been extensively researched or is yet to be explored. It is a question, problem or issue that has not been addressed or resolved by previous research.

How to Identify Research Gap

Identifying a research gap is an essential step in conducting research that adds value and contributes to the existing body of knowledge. Research gap requires critical thinking, creativity, and a thorough understanding of the existing literature . It is an iterative process that may require revisiting and refining your research questions and ideas multiple times.

Here are some steps that can help you identify a research gap:

- Review existing literature: Conduct a thorough review of the existing literature in your research area. This will help you identify what has already been studied and what gaps still exist.

- Identify a research problem: Identify a specific research problem or question that you want to address.

- Analyze existing research: Analyze the existing research related to your research problem. This will help you identify areas that have not been studied, inconsistencies in the findings, or limitations of the previous research.

- Brainstorm potential research ideas : Based on your analysis, brainstorm potential research ideas that address the identified gaps.

- Consult with experts: Consult with experts in your research area to get their opinions on potential research ideas and to identify any additional gaps that you may have missed.

- Refine research questions: Refine your research questions and hypotheses based on the identified gaps and potential research ideas.

- Develop a research proposal: Develop a research proposal that outlines your research questions, objectives, and methods to address the identified research gap.

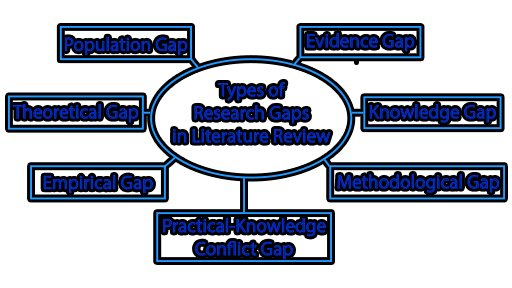

Types of Research Gap

There are different types of research gaps that can be identified, and each type is associated with a specific situation or problem. Here are the main types of research gaps and their explanations:

Theoretical Gap

This type of research gap refers to a lack of theoretical understanding or knowledge in a particular area. It can occur when there is a discrepancy between existing theories and empirical evidence or when there is no theory that can explain a particular phenomenon. Identifying theoretical gaps can lead to the development of new theories or the refinement of existing ones.

Empirical Gap

An empirical gap occurs when there is a lack of empirical evidence or data in a particular area. It can happen when there is a lack of research on a specific topic or when existing research is inadequate or inconclusive. Identifying empirical gaps can lead to the development of new research studies to collect data or the refinement of existing research methods to improve the quality of data collected.

Methodological Gap

This type of research gap refers to a lack of appropriate research methods or techniques to answer a research question. It can occur when existing methods are inadequate, outdated, or inappropriate for the research question. Identifying methodological gaps can lead to the development of new research methods or the modification of existing ones to better address the research question.

Practical Gap

A practical gap occurs when there is a lack of practical applications or implementation of research findings. It can occur when research findings are not implemented due to financial, political, or social constraints. Identifying practical gaps can lead to the development of strategies for the effective implementation of research findings in practice.

Knowledge Gap

This type of research gap occurs when there is a lack of knowledge or information on a particular topic. It can happen when a new area of research is emerging, or when research is conducted in a different context or population. Identifying knowledge gaps can lead to the development of new research studies or the extension of existing research to fill the gap.

Examples of Research Gap

Here are some examples of research gaps that researchers might identify:

- Theoretical Gap Example : In the field of psychology, there might be a theoretical gap related to the lack of understanding of the relationship between social media use and mental health. Although there is existing research on the topic, there might be a lack of consensus on the mechanisms that link social media use to mental health outcomes.

- Empirical Gap Example : In the field of environmental science, there might be an empirical gap related to the lack of data on the long-term effects of climate change on biodiversity in specific regions. Although there might be some studies on the topic, there might be a lack of data on the long-term effects of climate change on specific species or ecosystems.

- Methodological Gap Example : In the field of education, there might be a methodological gap related to the lack of appropriate research methods to assess the impact of online learning on student outcomes. Although there might be some studies on the topic, existing research methods might not be appropriate to assess the complex relationships between online learning and student outcomes.

- Practical Gap Example: In the field of healthcare, there might be a practical gap related to the lack of effective strategies to implement evidence-based practices in clinical settings. Although there might be existing research on the effectiveness of certain practices, they might not be implemented in practice due to various barriers, such as financial constraints or lack of resources.

- Knowledge Gap Example: In the field of anthropology, there might be a knowledge gap related to the lack of understanding of the cultural practices of indigenous communities in certain regions. Although there might be some research on the topic, there might be a lack of knowledge about specific cultural practices or beliefs that are unique to those communities.

Examples of Research Gap In Literature Review, Thesis, and Research Paper might be:

- Literature review : A literature review on the topic of machine learning and healthcare might identify a research gap in the lack of studies that investigate the use of machine learning for early detection of rare diseases.

- Thesis : A thesis on the topic of cybersecurity might identify a research gap in the lack of studies that investigate the effectiveness of artificial intelligence in detecting and preventing cyber attacks.

- Research paper : A research paper on the topic of natural language processing might identify a research gap in the lack of studies that investigate the use of natural language processing techniques for sentiment analysis in non-English languages.

How to Write Research Gap

By following these steps, you can effectively write about research gaps in your paper and clearly articulate the contribution that your study will make to the existing body of knowledge.

Here are some steps to follow when writing about research gaps in your paper:

- Identify the research question : Before writing about research gaps, you need to identify your research question or problem. This will help you to understand the scope of your research and identify areas where additional research is needed.

- Review the literature: Conduct a thorough review of the literature related to your research question. This will help you to identify the current state of knowledge in the field and the gaps that exist.

- Identify the research gap: Based on your review of the literature, identify the specific research gap that your study will address. This could be a theoretical, empirical, methodological, practical, or knowledge gap.

- Provide evidence: Provide evidence to support your claim that the research gap exists. This could include a summary of the existing literature, a discussion of the limitations of previous studies, or an analysis of the current state of knowledge in the field.

- Explain the importance: Explain why it is important to fill the research gap. This could include a discussion of the potential implications of filling the gap, the significance of the research for the field, or the potential benefits to society.

- State your research objectives: State your research objectives, which should be aligned with the research gap you have identified. This will help you to clearly articulate the purpose of your study and how it will address the research gap.

Importance of Research Gap

The importance of research gaps can be summarized as follows:

- Advancing knowledge: Identifying research gaps is crucial for advancing knowledge in a particular field. By identifying areas where additional research is needed, researchers can fill gaps in the existing body of knowledge and contribute to the development of new theories and practices.

- Guiding research: Research gaps can guide researchers in designing studies that fill those gaps. By identifying research gaps, researchers can develop research questions and objectives that are aligned with the needs of the field and contribute to the development of new knowledge.

- Enhancing research quality: By identifying research gaps, researchers can avoid duplicating previous research and instead focus on developing innovative research that fills gaps in the existing body of knowledge. This can lead to more impactful research and higher-quality research outputs.

- Informing policy and practice: Research gaps can inform policy and practice by highlighting areas where additional research is needed to inform decision-making. By filling research gaps, researchers can provide evidence-based recommendations that have the potential to improve policy and practice in a particular field.

Applications of Research Gap

Here are some potential applications of research gap:

- Informing research priorities: Research gaps can help guide research funding agencies and researchers to prioritize research areas that require more attention and resources.

- Identifying practical implications: Identifying gaps in knowledge can help identify practical applications of research that are still unexplored or underdeveloped.

- Stimulating innovation: Research gaps can encourage innovation and the development of new approaches or methodologies to address unexplored areas.

- Improving policy-making: Research gaps can inform policy-making decisions by highlighting areas where more research is needed to make informed policy decisions.

- Enhancing academic discourse: Research gaps can lead to new and constructive debates and discussions within academic communities, leading to more robust and comprehensive research.

Advantages of Research Gap

Here are some of the advantages of research gap:

- Identifies new research opportunities: Identifying research gaps can help researchers identify areas that require further exploration, which can lead to new research opportunities.

- Improves the quality of research: By identifying gaps in current research, researchers can focus their efforts on addressing unanswered questions, which can improve the overall quality of research.

- Enhances the relevance of research: Research that addresses existing gaps can have significant implications for the development of theories, policies, and practices, and can therefore increase the relevance and impact of research.

- Helps avoid duplication of effort: Identifying existing research can help researchers avoid duplicating efforts, saving time and resources.

- Helps to refine research questions: Research gaps can help researchers refine their research questions, making them more focused and relevant to the needs of the field.

- Promotes collaboration: By identifying areas of research that require further investigation, researchers can collaborate with others to conduct research that addresses these gaps, which can lead to more comprehensive and impactful research outcomes.

Disadvantages of Research Gap

While research gaps can be advantageous, there are also some potential disadvantages that should be considered:

- Difficulty in identifying gaps: Identifying gaps in existing research can be challenging, particularly in fields where there is a large volume of research or where research findings are scattered across different disciplines.

- Lack of funding: Addressing research gaps may require significant resources, and researchers may struggle to secure funding for their work if it is perceived as too risky or uncertain.

- Time-consuming: Conducting research to address gaps can be time-consuming, particularly if the research involves collecting new data or developing new methods.

- Risk of oversimplification: Addressing research gaps may require researchers to simplify complex problems, which can lead to oversimplification and a failure to capture the complexity of the issues.

- Bias : Identifying research gaps can be influenced by researchers’ personal biases or perspectives, which can lead to a skewed understanding of the field.

- Potential for disagreement: Identifying research gaps can be subjective, and different researchers may have different views on what constitutes a gap in the field, leading to disagreements and debate.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Purpose of Research – Objectives and Applications

Appendix in Research Paper – Examples and...

Research Project – Definition, Writing Guide and...

Research Objectives – Types, Examples and...

Research Contribution – Thesis Guide

APA Table of Contents – Format and Example

- Planning to Write

Q: How do I identify a research gap during the literature review?

When writing the literature review of a particular research topic, how do I know what the previous literature is missing and what needs to be addressed?

Asked on 29 Jan, 2021

Specifically in the context of doing and writing the literature review, you can identify a gap in any/all of the following ways:

- Look up papers that build on previous papers, be it by the same author/s or others. Find out what gaps the later papers have addressed, and if there are still any.

- On the same lines, you may also wish to go through papers cited by the present paper.

- Go through the Discussion/Conclusion section of the paper, where the author(s) talk(s) of the shortcomings of their research and suggest ways in which they think their research could be improved in the future. Also go through the implications and recommendations mentioned (if any) in case there are any ideas there.

- Finally, it also comes down to your knowledge of the topic you are studying and your research acumen, your astuteness in being able to identify a gap that could lead to a potential study of considerable significance/impact. This, as you can gauge, will come with time.

For now, here are some resources for further help with your question.

- How does a problem statement lend itself to further inquiry on confirming a gap in research?

- How can I describe the gap in literature when no previous research has been done on the problem?

- Would my work be considered addressing a research gap or making a contribution?

And here are some resources for help with writing a literature review .

- What a journal editor expects to see in a literature review

- How to write the literature review of your research paper

And in case you’re presently writing a review paper, all the best!

Answered by Editage Insights on 02 Feb, 2021

- Upvote this Answer

This content belongs to the Conducting Research Stage

Confirm that you would also like to sign up for free personalized email coaching for this stage.

Trending Searches

- Statement of the problem

- Background of study

- Scope of the study

- Types of qualitative research

- Rationale of the study

- Concept paper

- Literature review

- Introduction in research

- Under "Editor Evaluation"

- Ethics in research

Recent Searches

- Review paper

- Responding to reviewer comments

- Predatory publishers

- Scope and delimitations

- Open access

- Plagiarism in research

- Journal selection tips

- Editor assigned

- Types of articles

- "Reject and Resubmit" status

- Decision in process

- Conflict of interest

Research Methods

- Getting Started

- Literature Review Research

- Research Design

- Research Design By Discipline

- SAGE Research Methods

- Teaching with SAGE Research Methods

Literature Review

- What is a Literature Review?

- What is NOT a Literature Review?

- Purposes of a Literature Review

- Types of Literature Reviews

- Literature Reviews vs. Systematic Reviews

- Systematic vs. Meta-Analysis

Literature Review is a comprehensive survey of the works published in a particular field of study or line of research, usually over a specific period of time, in the form of an in-depth, critical bibliographic essay or annotated list in which attention is drawn to the most significant works.

Also, we can define a literature review as the collected body of scholarly works related to a topic:

- Summarizes and analyzes previous research relevant to a topic

- Includes scholarly books and articles published in academic journals

- Can be an specific scholarly paper or a section in a research paper

The objective of a Literature Review is to find previous published scholarly works relevant to an specific topic

- Help gather ideas or information

- Keep up to date in current trends and findings

- Help develop new questions

A literature review is important because it:

- Explains the background of research on a topic.

- Demonstrates why a topic is significant to a subject area.

- Helps focus your own research questions or problems

- Discovers relationships between research studies/ideas.

- Suggests unexplored ideas or populations

- Identifies major themes, concepts, and researchers on a topic.

- Tests assumptions; may help counter preconceived ideas and remove unconscious bias.

- Identifies critical gaps, points of disagreement, or potentially flawed methodology or theoretical approaches.

- Indicates potential directions for future research.

All content in this section is from Literature Review Research from Old Dominion University

Keep in mind the following, a literature review is NOT:

Not an essay

Not an annotated bibliography in which you summarize each article that you have reviewed. A literature review goes beyond basic summarizing to focus on the critical analysis of the reviewed works and their relationship to your research question.

Not a research paper where you select resources to support one side of an issue versus another. A lit review should explain and consider all sides of an argument in order to avoid bias, and areas of agreement and disagreement should be highlighted.

A literature review serves several purposes. For example, it

- provides thorough knowledge of previous studies; introduces seminal works.

- helps focus one’s own research topic.

- identifies a conceptual framework for one’s own research questions or problems; indicates potential directions for future research.

- suggests previously unused or underused methodologies, designs, quantitative and qualitative strategies.

- identifies gaps in previous studies; identifies flawed methodologies and/or theoretical approaches; avoids replication of mistakes.

- helps the researcher avoid repetition of earlier research.

- suggests unexplored populations.

- determines whether past studies agree or disagree; identifies controversy in the literature.

- tests assumptions; may help counter preconceived ideas and remove unconscious bias.

As Kennedy (2007) notes*, it is important to think of knowledge in a given field as consisting of three layers. First, there are the primary studies that researchers conduct and publish. Second are the reviews of those studies that summarize and offer new interpretations built from and often extending beyond the original studies. Third, there are the perceptions, conclusions, opinion, and interpretations that are shared informally that become part of the lore of field. In composing a literature review, it is important to note that it is often this third layer of knowledge that is cited as "true" even though it often has only a loose relationship to the primary studies and secondary literature reviews.

Given this, while literature reviews are designed to provide an overview and synthesis of pertinent sources you have explored, there are several approaches to how they can be done, depending upon the type of analysis underpinning your study. Listed below are definitions of types of literature reviews:

Argumentative Review This form examines literature selectively in order to support or refute an argument, deeply imbedded assumption, or philosophical problem already established in the literature. The purpose is to develop a body of literature that establishes a contrarian viewpoint. Given the value-laden nature of some social science research [e.g., educational reform; immigration control], argumentative approaches to analyzing the literature can be a legitimate and important form of discourse. However, note that they can also introduce problems of bias when they are used to to make summary claims of the sort found in systematic reviews.

Integrative Review Considered a form of research that reviews, critiques, and synthesizes representative literature on a topic in an integrated way such that new frameworks and perspectives on the topic are generated. The body of literature includes all studies that address related or identical hypotheses. A well-done integrative review meets the same standards as primary research in regard to clarity, rigor, and replication.

Historical Review Few things rest in isolation from historical precedent. Historical reviews are focused on examining research throughout a period of time, often starting with the first time an issue, concept, theory, phenomena emerged in the literature, then tracing its evolution within the scholarship of a discipline. The purpose is to place research in a historical context to show familiarity with state-of-the-art developments and to identify the likely directions for future research.

Methodological Review A review does not always focus on what someone said [content], but how they said it [method of analysis]. This approach provides a framework of understanding at different levels (i.e. those of theory, substantive fields, research approaches and data collection and analysis techniques), enables researchers to draw on a wide variety of knowledge ranging from the conceptual level to practical documents for use in fieldwork in the areas of ontological and epistemological consideration, quantitative and qualitative integration, sampling, interviewing, data collection and data analysis, and helps highlight many ethical issues which we should be aware of and consider as we go through our study.

Systematic Review This form consists of an overview of existing evidence pertinent to a clearly formulated research question, which uses pre-specified and standardized methods to identify and critically appraise relevant research, and to collect, report, and analyse data from the studies that are included in the review. Typically it focuses on a very specific empirical question, often posed in a cause-and-effect form, such as "To what extent does A contribute to B?"

Theoretical Review The purpose of this form is to concretely examine the corpus of theory that has accumulated in regard to an issue, concept, theory, phenomena. The theoretical literature review help establish what theories already exist, the relationships between them, to what degree the existing theories have been investigated, and to develop new hypotheses to be tested. Often this form is used to help establish a lack of appropriate theories or reveal that current theories are inadequate for explaining new or emerging research problems. The unit of analysis can focus on a theoretical concept or a whole theory or framework.

* Kennedy, Mary M. "Defining a Literature." Educational Researcher 36 (April 2007): 139-147.

All content in this section is from The Literature Review created by Dr. Robert Larabee USC

Robinson, P. and Lowe, J. (2015), Literature reviews vs systematic reviews. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health, 39: 103-103. doi: 10.1111/1753-6405.12393

What's in the name? The difference between a Systematic Review and a Literature Review, and why it matters . By Lynn Kysh from University of Southern California

Systematic review or meta-analysis?

A systematic review answers a defined research question by collecting and summarizing all empirical evidence that fits pre-specified eligibility criteria.

A meta-analysis is the use of statistical methods to summarize the results of these studies.

Systematic reviews, just like other research articles, can be of varying quality. They are a significant piece of work (the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination at York estimates that a team will take 9-24 months), and to be useful to other researchers and practitioners they should have:

- clearly stated objectives with pre-defined eligibility criteria for studies

- explicit, reproducible methodology

- a systematic search that attempts to identify all studies

- assessment of the validity of the findings of the included studies (e.g. risk of bias)

- systematic presentation, and synthesis, of the characteristics and findings of the included studies

Not all systematic reviews contain meta-analysis.

Meta-analysis is the use of statistical methods to summarize the results of independent studies. By combining information from all relevant studies, meta-analysis can provide more precise estimates of the effects of health care than those derived from the individual studies included within a review. More information on meta-analyses can be found in Cochrane Handbook, Chapter 9 .

A meta-analysis goes beyond critique and integration and conducts secondary statistical analysis on the outcomes of similar studies. It is a systematic review that uses quantitative methods to synthesize and summarize the results.

An advantage of a meta-analysis is the ability to be completely objective in evaluating research findings. Not all topics, however, have sufficient research evidence to allow a meta-analysis to be conducted. In that case, an integrative review is an appropriate strategy.

Some of the content in this section is from Systematic reviews and meta-analyses: step by step guide created by Kate McAllister.

- << Previous: Getting Started

- Next: Research Design >>

- Last Updated: Aug 21, 2023 4:07 PM

- URL: https://guides.lib.udel.edu/researchmethods

Warning: The NCBI web site requires JavaScript to function. more...

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it's official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you're on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Browse Titles

NCBI Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

Robinson KA, Akinyede O, Dutta T, et al. Framework for Determining Research Gaps During Systematic Review: Evaluation [Internet]. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2013 Feb.

Framework for Determining Research Gaps During Systematic Review: Evaluation [Internet].

Introduction.

The identification of gaps from systematic reviews is essential to the practice of “evidence-based research.” Health care research should begin and end with a systematic review. 1 - 3 A comprehensive and explicit consideration of the existing evidence is necessary for the identification and development of an unanswered and answerable question, for the design of a study most likely to answer that question, and for the interpretation of the results of the study. 4

In a systematic review, the consideration of existing evidence often highlights important areas where deficiencies in information limit our ability to make decisions. We define a research gap as a topic or area for which missing or inadequate information limits the ability of reviewers to reach a conclusion for a given question. A research gap may be further developed, such as through stakeholder engagement in prioritization, into research needs. Research needs are those areas where the gaps in the evidence limit decision making by patients, clinicians, and policy makers. A research gap may not be a research need if filling the gap would not be of use to stakeholders that make decisions in health care. The clear and explicit identification of research gaps is a necessary step in developing a research agenda. Evidence reports produced by Evidence-based Practice Centers (EPCs) have always included a future research section. However, in contrast to the explicit and transparent steps taken in the completion of a systematic review, there has not been a systematic process for the identification of research gaps.

In a prior methods project, our EPC set out to identify and pilot test a framework for the identification of research gaps. 5 , 6 We searched the literature, conducted an audit of EPC evidence reports, and sought information from other organizations which conduct evidence synthesis. Despite these efforts, we identified little detail or consistency in the frameworks used to determine research gaps within systematic reviews. In general, we found no widespread use or endorsement of a specific formal process or framework for identifying research gaps using systematic reviews.

We developed a framework to systematically identify research gaps from systematic reviews. This framework facilitates the classification of where the current evidence falls short and why the evidence falls short. The framework included two elements: (1) the characterization the gaps and (2) the identification and classification of the reason(s) for the research gap.

The PICOS structure (Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome and Setting) was used in this framework to describe questions or parts of questions inadequately addressed by the evidence synthesized in the systematic review. The issue of timing, sometimes included as PICOTS, was considered separately for Intervention, Comparison, and Outcome. The PICOS elements were the only sort of framework we had identified in an audit of existing methods for the identification of gaps used by EPCs and other related organizations (i.e., health technology assessment organizations). We chose to use this structure as it is one familiar to EPCs, and others, in developing questions.

It is not only important to identify research gaps but also to determine how the evidence falls short, in order to maximally inform researchers, policy makers, and funders on the types of questions that need to be addressed and the types of studies needed to address these questions. Thus, the second element of the framework was the classification of the reasons for the existence of a research gap. For each research gap, the reason(s) that most preclude conclusions from being made in the systematic review is chosen by the review team completing the framework. To leverage work already being completed by review teams, we mapped the reasons for research gaps to concepts from commonly used evidence grading systems. Briefly, these categories of reasons, explained in detail in the prior JHU EPC report 5 , are:

- Insufficient or imprecise information

- Biased information

- Inconsistent or unknown consistency results

- Not the right information

The framework facilitates a systematic approach to identifying research gaps and the reasons for those gaps. The identification of where the evidence falls short and how the evidence falls short is essential to the development of important research questions and in providing guidance in how to address these questions.

As part of the previous methods product, we developed a worksheet and instructions to facilitate the use of the framework when completing a systematic review (See Appendix A ). Preliminary evaluation of the framework and worksheet was completed by applying the framework to two completed EPC evidence reports. The framework was further refined through peer review. In this current project, we extend our work on this research gaps framework.

Our objective in this project was to complete two types of further evaluation: (1) application of the framework across a larger sample of existing systematic reviews in different topic areas, and (2) implementation of the framework by EPCs. These two objectives were used to evaluate the framework and instructions for usability and to evaluate the application of the framework by others, outside of our EPC, including as part of the process of completing an EPC report. Our overall goal was to produce a revised framework with guidance that could be used by EPCs to explicitly identify research gaps from systematic reviews.

- Cite this Page Robinson KA, Akinyede O, Dutta T, et al. Framework for Determining Research Gaps During Systematic Review: Evaluation [Internet]. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2013 Feb. Introduction.

- PDF version of this title (425K)

Other titles in these collections

- AHRQ Methods for Effective Health Care

- Health Services/Technology Assessment Texts (HSTAT)

Recent Activity

- Introduction - Framework for Determining Research Gaps During Systematic Review:... Introduction - Framework for Determining Research Gaps During Systematic Review: Evaluation

Your browsing activity is empty.

Activity recording is turned off.

Turn recording back on

Connect with NLM

National Library of Medicine 8600 Rockville Pike Bethesda, MD 20894

Web Policies FOIA HHS Vulnerability Disclosure

Help Accessibility Careers

info This is a space for the teal alert bar.

notifications This is a space for the yellow alert bar.

Research Process

- Brainstorming

- Explore Google This link opens in a new window

- Explore Web Resources

- Explore Background Information

- Explore Books

- Explore Scholarly Articles

- Narrowing a Topic

- Primary and Secondary Resources

- Academic, Popular & Trade Publications

- Scholarly and Peer-Reviewed Journals

- Grey Literature

- Clinical Trials

- Evidence Based Treatment

- Scholarly Research

- Database Research Log

- Search Limits

- Keyword Searching

- Boolean Operators

- Phrase Searching

- Truncation & Wildcard Symbols

- Proximity Searching

- Field Codes

- Subject Terms and Database Thesauri

- Reading a Scientific Article

- Website Evaluation

- Article Keywords and Subject Terms

- Cited References

- Citing Articles

- Related Results

- Search Within Publication

- Database Alerts & RSS Feeds

- Personal Database Accounts

- Persistent URLs

- Literature Gap and Future Research

- Web of Knowledge

- Annual Reviews

- Systematic Reviews & Meta-Analyses

- Finding Seminal Works

- Exhausting the Literature

- Finding Dissertations

- Researching Theoretical Frameworks

- Research Methodology & Design

- Tests and Measurements

- Organizing Research & Citations This link opens in a new window

- Scholarly Publication

- Learn the Library This link opens in a new window

Research Articles

These examples below illustrate how researchers from different disciplines identified gaps in existing literature. For additional examples, try a NavigatorSearch using this search string: ("Literature review") AND (gap*)

- Addressing the Recent Developments and Potential Gaps in the Literature of Corporate Sustainability

- Applications of Psychological Science to Teaching and Learning: Gaps in the Literature

- Attitudes, Risk Factors, and Behaviours of Gambling Among Adolescents and Young People: A Literature Review and Gap Analysis

- Do Psychological Diversity Climate, HRM Practices, and Personality Traits (Big Five) Influence Multicultural Workforce Job Satisfaction and Performance? Current Scenario, Literature Gap, and Future Research Directions

- Entrepreneurship Education: A Systematic Literature Review and Identification of an Existing Gap in the Field

- Evidence and Gaps in the Literature on HIV/STI Prevention Interventions Targeting Migrants in Receiving Countries: A Scoping Review

- Homeless Indigenous Veterans and the Current Gaps in Knowledge: The State of the Literature

- A Literature Review and Gap Analysis of Emerging Technologies and New Trends in Gambling

- A Review of Higher Education Image and Reputation Literature: Knowledge Gaps and a Research Agenda

- Trends and Gaps in Empirical Research on Open Educational Resources (OER): A Systematic Mapping of the Literature from 2015 to 2019

- Where Should We Go From Here? Identified Gaps in the Literature in Psychosocial Interventions for Youth With Autism Spectrum Disorder and Comorbid Anxiety

What is a ‘gap in the literature’?

The gap, also considered the missing piece or pieces in the research literature, is the area that has not yet been explored or is under-explored. This could be a population or sample (size, type, location, etc.), research method, data collection and/or analysis, or other research variables or conditions.

It is important to keep in mind, however, that just because you identify a gap in the research, it doesn't necessarily mean that your research question is worthy of exploration. You will want to make sure that your research will have valuable practical and/or theoretical implications. In other words, answering the research question could either improve existing practice and/or inform professional decision-making (Applied Degree), or it could revise, build upon, or create theoretical frameworks informing research design and practice (Ph.D Degree). See the Dissertation Center for additional information about dissertation criteria at NU.

For a additional information on gap statements, see the following:

- How to Find a Gap in the Literature

- Write Like a Scientist: Gap Statements

How do you identify the gaps?

Conducting an exhaustive literature review is your first step. As you search for journal articles, you will need to read critically across the breadth of the literature to identify these gaps. You goal should be to find a ‘space’ or opening for contributing new research. The first step is gathering a broad range of research articles on your topic. You may want to look for research that approaches the topic from a variety of methods – qualitative, quantitative, or mixed methods.

See the videos below for further instruction on identifying a gap in the literature.

Identifying a Gap in the Literature - Dr. Laurie Bedford

How Do You Identify Gaps in Literature? - SAGE Research Methods

Literature Gap & Future Research - Library Workshop

This workshop presents effective search techniques for identifying a gap in the literature and recommendations for future research.

Where can you locate research gaps?

As you begin to gather the literature, you will want to critically read for what has, and has not, been learned from the research. Use the Discussion and Future Research sections of the articles to understand what the researchers have found and where they point out future or additional research areas. This is similar to identifying a gap in the literature, however, future research statements come from a single study rather than an exhaustive search. You will want to check the literature to see if those research questions have already been answered.

Roadrunner Search

Identifying the gap in the research relies on an exhaustive review of the literature. Remember, researchers may not explicitly state that a gap in the literature exists; you may need to thoroughly review and assess the research to make that determination yourself.

However, there are techniques that you can use when searching in NavigatorSearch to help identify gaps in the literature. You may use search terms such as "literature gap " or "future research" "along with your subject keywords to pinpoint articles that include these types of statements.

Was this resource helpful?

- << Previous: Resources for a Literature Review

- Next: Web of Knowledge >>

- Last Updated: Jun 12, 2024 1:44 PM

- URL: https://resources.nu.edu/researchprocess

© Copyright 2024 National University. All Rights Reserved.

Privacy Policy | Consumer Information

Research to Action

The Global Guide to Research Impact

Social Media

Framing challenges

Gap analysis for literature reviews and advancing useful knowledge

By Steve Wallis and Bernadette Wright 02/06/2020

The basics of research are seemingly clear. Read a lot of articles, see what’s missing, and conduct research to fill the gap in the literature. Wait a minute. What is that? ‘See what’s missing?’ How can we see something that is not there?

Imagine you are videoconferencing a colleague who is showing you the results of their project. Suddenly, the screen and sound cut out for a minute. After pressing some keys, you manage to restore the link; only to have your colleague ask, ‘What do you think?’. Of course, you know that you missed something from the presentation because of the disconnection. You can see that something is missing, and you know what to ask for to get your desired results, ‘Sorry, could you repeat that last minute of your presentation, please’. It’s not so easy when we’re looking at research results, proposals, or literature reviews.

While all research is, to some extent, useful, we’ve seen a lot of research that does not have the expected impact. That means wasted time, wasted money, under-served clients, and frustration on multiple levels. A big part of that problem is that directions for research are often chosen intuitively; in a sort of ad-hoc process. While we deeply respect the intuition of experts, that kind of process is not very rigorous.

In this post, we will show you how to ‘see the invisible’: How to identify the missing pieces in any study, literature review, or program analysis. With these straight-forward techniques, you will be able to better target your research in a more cost-effective way to fill those knowledge gaps to develop more effective theories, plans, and evaluations.

The first step is to choose your source material. That can be one or more articles, reports, or other study results. Of course, you want to be sure that the material you use is of high quality . Next, you want to create a causal map of your source material.

We’re going to go a bit abstract on you here because people sometimes get lost in the ‘content’ when what we are looking at here is more about the ‘structure’. Think of it like choosing how to buy a house based on how well it is built, rather than what color it is painted. So, instead of using actual concepts, we’ll refer to them as concepts A, B, C… and so on.

So, the text might say something like: ‘Our research shows that A causes B, B causes C, and D causes less C. Oh yes, and E is also important (although we’re not sure how it’s causally connected to A, B, C, or D)’.

When we draw causal maps from the source material we’ve found, we like to have key concepts in circles, with causal connections represented by arrows.

Figure 1. Abstract example of a causal map of a theory

There are really three basic kinds of gaps for you to find: relevance/meaning, logic/structure, and data/evidence. Starting with structure, there is a gap any place where there are two circles NOT connected by a causal arrow. It is important to have at least two arrows pointing at each concept/circle for the same reason we like to have multiple independent variables for each dependent variable (although, with more complex maps, we’re learning to see these as interdependent variables).

For example, there is no arrow between A and D. Also, there is no arrow between E and any of the other concepts. Each of those is a structural gap – an opening for additional research.

You might also notice that there are two arrows pointing directly at C. Like having two independent variables and one dependent variable, it is structurally better to have at least two arrows pointing at each concept.

So, structurally , C is in good shape. This part of the map has the least need for additional research. A larger gap exists around B, because it has only one arrow pointing at it (the arrow from A to B). Larger still is the gap around A, D, and E; because they have no arrows pointing at them.

To get the greatest leverage for your research dollar, it is generally best to search for that second arrow. In short, one research question would be: What (aside from A) has a causal influence on B? Other good research questions would be (a) Is there a causal relationship between A and D? (b) Is there a causal relationship between E and any of the other concepts? (c) What else besides A helps cause B? (d) What are the causes of A, D, and E?

Now, let’s take a look at gaps in the data, evidence, or information upon which each causal arrow is established.

From structure to data

Here, we add to the drawing by making a note showing (very briefly) the kind of data supporting each causal arrow. We like to have that in a box – with a loopy line ‘typing’ the evidence to the connection. You can also use different colors to more easily differentiate between the concepts and the evidence on your map. You can also write the note along the length of the arrow.

Figure 2. Tying the data to the structure

From data to stakeholder relevance

Finally, the gap in meaning (relevance) asks if those studies were done with the ‘right’ people. By this, we mean people related to the situation or topic you are studying. Managers, line workers, clients, suppliers, those providing related services; all of those and more should be included. Similarly, you might look to a variety of academic disciplines, drawing expertise from psychology, sociology, business, economics, policy, and others.

Which participants or stakeholders are actually part of your research depends on the project. However, in general, having a broader selection of stakeholder groups results in a better map. This applies to both choosing what concepts go on the map and also who to contact for interviews and surveys.

Visualizing the gaps

All of these three gaps – gaps in structure, data, and stakeholder perspectives – can (and should) be addressed to help you choose more focused directions for your research – to generate research results that will have more impact. As a final note, remember that many gaps may be filled with secondary research; a new literature review that fills the gaps in the logic/structure, data/information, and meaning/relevance of your map so that your organisation can have a greater impact.

Figure 3. Visualizing the gaps (shown in green)

Some deeper reading on literature reviews may be found here:

- Practical Mapping for Applied Research and Program Evaluation (SAGE) provides a ‘jargon free’ explanation for every phase of research:

https://us.sagepub.com/en-us/nam/practical-mapping-for-applied-research-and-program-evaluation/book261152 (especially Chapter 3)

- This paper uses theories for addressing poverty from a range of academic disciplines and from policy centers from across the political spectrum as an example of interdisciplinary knowledge mapping and synthesis:

https://www.emerald.com/insight/content/doi/10.1108/K-03-2018-0136/full/html

- Restructuring evaluation findings into useful knowledge:

http://journals.sfu.ca/jmde/index.php/jmde_1/article/download/481/436/

This approach helps you to avoid fuzzy understandings and the dangerous ‘pretence of knowledge’ that occasionally crops up in some reports and recommendations. Everyone can see that a piece is missing and so more easily agree where more research is needed to advance our knowledge to better serve our organisational and community constituents.

Contribute Write a blog post, post a job or event, recommend a resource

Partner with Us Are you an institution looking to increase your impact?

Most Recent Posts

- Health Adviser – Ethiopia and Nigeria, FCDO – Deadline 29th July

- A guide to research evaluation frameworks

- Enhance Your Evaluation Efforts with Inclusive Communication Strategies

- Six mechanisms to strengthen citizen engagement in public service governance

- Senior Research and Learning Manager: UK Humanitarian Innovation Hub – Deadline 7th July

🌟 This week, #R2ARecommends this webinar on demystifying evaluation practice, produced by the Global Evaluation Initiative. 🌟 🔗Follow the #R2ARecommends link in our linktree to find out more! #Evaluation #Webinar #InclusiveCommunication #GEI #GlobalEval

This week #R2Arecommends this blog from AgileFacil examining the power of the 1-2-4-All structure for facilitation and effective, and inclusive, engagement. Follow the link in our bio to find this and many other recommended wisdom and resources.

"Co-production involves researchers, practitioners and the public working together and sharing power all the way through a research project." This week, #R2AImpactPractitioners spotlights this guide on co-producing a research project from the NIHR (National Institute for Health and Care Research). Follow the link in our Linktree to find this and other resources in the series.

Research To Action (R2A) is a learning platform for anyone interested in maximising the impact of research and capturing evidence of impact.