School Mental Health

A Multidisciplinary Research and Practice Journal

- Focuses on children and adolescents with emotional and behavioral disorders.

- Welcomes empirical studies, quantitative and qualitative research, and systematic and scoping review articles.

- Features work from many disciplines that are involved in school mental health, including but not limited to child and school psychology, education, child and adolescent psychiatry, developmental psychology, school counseling, and social work.

- Covers innovative school-based treatment practices, training procedures, educational techniques for children with emotional and behavioral disorders, racial, ethnic, and cultural issues, the role of families in school mental health, and simlar topics.

This is a transformative journal , you may have access to funding.

- Steven Evans

Latest issue

Volume 16, Issue 1

Latest articles

Socially prescribed perfectionism and depression: roles of academic pressure and hope.

Adolescents’ Covitality Patterns: Relations with Student Demographic Characteristics and Proximal Academic and Mental Health Outcomes

- Stephanie A. Moore

- Delwin Carter

Partnering with Schools to Adapt a Team Science Intervention: Processes and Challenges

- Aparajita Biswas Kuriyan

- Jordan Albright

- Courtney Benjamin Wolk

#TEBWorks: Engaging Youth in a Community-Based Participatory Research and User-Centered Design Approach to Intervention Adaptation

- Anna D. Bartuska

- Lillian Blanchard

- Luana Marques

Teaching Adolescents about Stress Using a Universal School-Based Psychoeducation Program: A Cluster Randomised Controlled Trial

- Simone Vogelaar

- Anne C. Miers

- P. Michiel Westenberg

Journal updates

Solicitation for papers for special issue: “suicide prevention in k-12 schools”, researcher reflexive self-description, virtual issue, publish in this journal.

Read more here about why publishing in School Mental Health is right for you!

Journal information

- Current Contents/Social & Behavioral Sciences

- Google Scholar

- Japanese Science and Technology Agency (JST)

- OCLC WorldCat Discovery Service

- Social Science Citation Index

- TD Net Discovery Service

- UGC-CARE List (India)

Rights and permissions

Springer policies

© Springer Science+Business Media, LLC, part of Springer Nature

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

Log in using your username and password

- Search More Search for this keyword Advanced search

- Latest content

- Current issue

- BMJ Journals More You are viewing from: Google Indexer

You are here

- Volume 76, Issue 5

- Research priorities for mental health in schools in the wake of COVID-19

- Article Text

- Article info

- Citation Tools

- Rapid Responses

- Article metrics

- http://orcid.org/0000-0001-7854-6810 Rhiannon Barker 1 ,

- http://orcid.org/0000-0001-9153-7126 Greg Hartwell 1 ,

- http://orcid.org/0000-0002-6253-6498 Chris Bonell 2 ,

- Matt Egan 1 ,

- Karen Lock 1 ,

- http://orcid.org/0000-0003-3047-2247 Russell M Viner 3

- 1 SPHR , London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine , London , UK

- 2 PHES , London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine , London , UK

- 3 Institute of Child Health , University College London , London , UK

- Correspondence to Dr Rhiannon Barker, SPHR, London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, London WC1E 7HT, UK; rhiannon.barker{at}lshtm.ac.uk

Children and young people (CYP) have suffered challenges to their mental health as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic; effects have been most pronounced on those already disadvantaged. Adopting a whole-school approach embracing changes to school environments, cultures and curricula is key to recovery, combining social and emotional skill building, mental health support and interventions to promote commitment and belonging. An evidence-based response must be put in place to support schools, which acknowledges that the mental health and well-being of CYP should not be forfeited in the drive to address the attainment gap. Schools provide an ideal setting for universal screening of mental well-being to help monitor and respond to the challenges facing CYP in the wake of the pandemic. Research is needed to support identification and implementation of suitable screening methods.

- mental health

- public health

- child health

- health policy

This is an open access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited, appropriate credit is given, any changes made indicated, and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ .

https://doi.org/10.1136/jech-2021-217902

Statistics from Altmetric.com

Request permissions.

If you wish to reuse any or all of this article please use the link below which will take you to the Copyright Clearance Center’s RightsLink service. You will be able to get a quick price and instant permission to reuse the content in many different ways.

COVID-19 has had significant impacts on the physical and mental well-being of children and young people (CYP) around the world. 1 Schools provide essential structure, routine and support for many students, particularly the most vulnerable. Growing evidence suggests a strong link between mental health and academic attainment 2 ; a recent English study suggests mental health at ages 11–14 predicts attainment at age 16. 3 This relationship is likely bidirectional, with data suggesting that exam anxiety is more significant in those who perceive their academic ability as low. 4 Additionally, analysis from a large longitudinal cohort of parents and children in Bristol, UK, indicates that low attainment at 16 predicts increased depressive symptoms at age 18. 5

The pandemic has presented enormous challenges, creating crises in both academic attainment and CYP’s mental health. As education sectors worldwide try to return to normality following periods of lockdown, there are dual imperatives: to provide effective support to address student mental health and well-being, while also addressing gaps and inequalities in academic progress. We argue that, following the upheaval of the pandemic, schools must be supported to address the mental health and well-being of both students and staff. This can be most effectively achieved via delivery of whole-school initiatives and promotion of positive whole-school culture by school leaders. Specifically, we highlight the importance of routine screening of student well-being in schools, and outline evidence demonstrating that both mental health and attainment can be addressed through a range of interventions relating to school culture including social and emotional learning, school mental health provision and work to promote a sense of commitment and belonging.

The impact of COVID-19 on CYP’s mental health

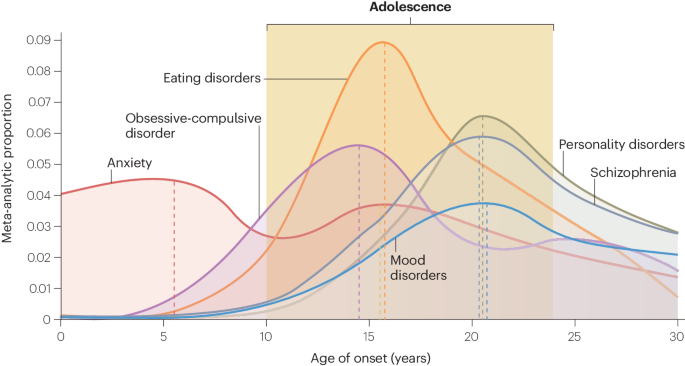

Approximately half of adult mental health disorders begin during adolescence. 6 International evidence indicates that CYP’s mental health was already deteriorating before pandemic, with increasing proportions of teenagers experiencing symptoms of distress or anxiety, or engaging in self-harm. 7 This is concerning given that poor mental health in these age groups is associated with adverse socioeconomic and mental health outcomes in later life. Results from a meta-analysis show that adolescents who suffer depression are 76% more likely to fail to complete secondary school and 66% more likely to be unemployed. 8 The burden is furthermore socially patterned, with socioeconomically disadvantaged CYP more likely to experience mental health problems and self-harm, 9 10 while being less likely to receive referrals into mental health services. 9

The long periods of isolation and uncertainty that the pandemic has forced on CYP have generated additional challenges. Systematic reviews examining impacts of school closures conclude that they have significantly harmed health and well-being in CYP. 11 The isolation and upheaval created by closures are most likely to have impacted adversely on CYP from lower socioeconomic groups for whom school can be a crucial source of support. 12 Adolescents from black, Asian and minority ethnic (BAME) groups show similar patterns to the adult BAME population, for whom pre-existing inequities have been exacerbated. 3 13

The pandemic’s impact is however not uniform; some studies note a protective effect with certain students reporting mental health benefits from reduced school-based academic pressures and more relaxed timetables. 14 A systematic review 15 examining COVID-19’s impact on adolescent mental health identifies several protective factors such as awareness of transmission routes, good parent–child relationships and strong family structure. It appears that those children receiving less stability and support from their home environment are at heightened risk. Commentators have also conjectured that the ability to stay in touch with peers, through good internet availability and access to social media, may have helped guard against loneliness and isolation. 14

Promising interventions for the school sector’s recovery

Work to build support for improving the mental health of CYP in schools needs to learn from the range of promising interventions that have been shown to be effective in improving measures of student well-being. In particular, many successful behavioural interventions have focused on developing social and emotional competencies which can positively impact on student mental health and academic and behavioural development. 16

Yet challenges have been highlighted around the implementation and embedding of classroom-based interventions to improve health and well-being. 17 Notably, there have been tendencies to overlook the specific context of the school or failure to consider the wider system that may create barriers. 18 Emphasis has now turned from the adoption of programmes targeting health-related behaviours to more comprehensive system-wide approaches. The focus on a whole-school approach to positive mental health is particularly urgent following the almost ubiquitous rise in need during the pandemic and the imperative to provide more generic well-being awareness. Practitioners are looking beyond classroom-based initiatives to interventions that impact on the ‘whole-school’, such as the Learning Together Programme, 19 focusing on reducing school-based bullying and aggression, and improving mental health. While the need for more rigorous evidence has been highlighted, an association is apparent between the school-level environment and mental health. 20 In addition, several studies have reported positive impacts of whole-school interventions on student well-being and mental health. 20 21 Systematic reviews have also considered whole-school approaches to tackling health-related behaviours. 22–24 Despite methodological challenges, these show promising findings linking school ethos and culture to positive mental health outcomes.

Central to a clear understanding of student outcomes is an insight into the mechanisms responsible for CYP engagement, the impact of school culture and the way students negotiate social networks. Greater clarity regarding how change is brought about will support the building of social and emotional skills, shown to be protective against behaviours which impact negatively on mental health. 17 This may help, for instance, with growing anxieties around the areas of harmful social media use, image sharing and sexual harassment, as highlighted by Ofsted’s recent report. 25 Work to foster positive school culture can aim to denormalise such harmful behaviours.

School environments are complex and the way a school impacts on those who study or work within it is influenced by a wide range of causal mechanisms, all of which need to be considered in a whole-school strategy. The Anna Freud Centre sets out a strategic framework for achieving improved mental health and well-being in schools: strong leadership promoting a supportive culture; working together at all levels (staff, students, parents and wider communities); understanding need through routine measurement and monitoring; promoting well-being through a range of whole-school initiatives and interventions; and supporting staff with their own well-being. 26

Moving forward

The temptation to adopt practices which react to immediate crises rather than to invest in longer term support based on best evidence must be avoided. Positive results emerging from whole-school interventions 22 27 28 can guide future work to strengthen school culture and point towards the particular importance of aspects such as student/teacher relationships, bullying reduction and student participation and engagement. The danger is that pressures on schools to focus on academic attainment and ‘curriculum catch-up’ will over-ride the need to address student well-being and mental health. This may in turn adversely impact those aspects of school culture which have been shown to have protective effects on mental health, such as the participation of CYP in school governance. Crucially, a system-wide commitment to the teaching of social and emotional skills and the provision of mental health support is required, as well as interventions to promote commitment and belonging. 27 Together, these have the potential not just to improve student mental health, but to increase attainment and lead to healthier, happier adult lives. Positive correlations found between good mental health and improved academic outputs 2 3 add further support to the importance of working, synergistically, on both these goals.

Leadership strategies that recognise the importance of staff and student mental health in COVID-19 recovery will be key. These should recognise the inequalities that have been exacerbated by lockdowns, improve schools’ physical environments, foster staff/student relationships and address bullying. Evidence from studies of school mental health initiatives is relevant here, given they suggest the effects of interventions are higher when targeting higher risk children. 29 Parallel to this is the need for adequate regulatory leverage, delivered through organisations such as Ofsted, to continue to support and incentivise mental health promotion in schools.

While schools collect multiple data relating to attainment, standardised information on the mental health and well-being of their students is rarely collected. Yet commentators suggest that, given their universality and extensive engagement with CYP, schools provide ideal settings for identifying those at risk of developing mental health difficulties. We recommend, that to monitor rising mental health challenges in our schools, a more standardised system of screening be implemented backed by increased research funding to explore and guide how to make best use of existing resources. All proposals should acknowledge the existing pressures on staff time and school resource, focusing on identifying a viable and pragmatic working model.

Within these future plans, a range of complex factors need to be considered including: an agreed definition of mental health (holistic well-being vs absence of clinical symptoms); reliability and validity of selected tools; design and implementation of screening (including staff training); cultural appropriateness and diversity; and costs and benefits. 30 Processes to seek informed consent from students and parents should be established, while recognition is needed that screening for mental health issues should be backed by the resources to enable appropriate responses to identified need. Intense pressures on finite resources require that, once need is identified, the most appropriate ‘response route’ is followed. The establishing of Mental Health Support Teams, 31 intended to provide extra capacity to deliver evidence-based interventions in schools and create better links to existing services, is an encouraging step. However, research is needed to monitor how support is delivered and to test new approaches such as the colocation of mental health staff in schools.

We propose that the complexity of school-based mental health research benefits from the guidance of a conceptual framework which acknowledges the interaction and influence of a wide range of factors at all system levels. The Systems View of School Climate 32 framework is one such model which adopts a system perspective and demonstrates the importance, both of factors within the school microsystem such as beliefs, values and relationships, as well as more distal ones in the mesosystem and macrosystem, which can all contribute towards creating an environment that works to build positive mental health in students and staff.

Finally, the importance of identifying interventions which address priorities articulated by CYP should not be overlooked, with students themselves involved in this work. Enabling this may require the development of new measures which consider concepts of ‘positive mental health’ and ‘flourishing’. Useful results should begin to emerge, for instance, from ongoing innovative projects 33 where students are collaborating as ‘active co-researchers’ using participatory approaches to measure well-being and respond to the rising mental health challenges faced by CYP.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication.

Not required.

- Loades ME ,

- Chatburn E ,

- Higson-Sweeney N , et al

- Lereya ST ,

- Dos Santos JPGA , et al

- Marshall L ,

- López-López JA ,

- Kwong ASF ,

- Washbrook E , et al

- Kessler RC ,

- Berglund P ,

- Demler O , et al

- Collishaw S

- Clayborne ZM ,

- Carr MJ , et al

- Russell S ,

- Widnall E ,

- Winstone L ,

- Octavius GS ,

- Silviani FR ,

- Lesmandjaja A , et al

- Durlak JA ,

- Weissberg RP ,

- Dymnicki AB , et al

- Clarke AM ,

- Caldwell DM ,

- Davies SR ,

- Hetrick SE , et al

- O'Reilly M ,

- Svirydzenka N ,

- Adams S , et al

- Warren E , et al

- Lister-Sharp D ,

- Chapman S ,

- Stewart-Brown S , et al

- MacArthur G ,

- Redmore J , et al

- Langford R ,

- Jones H , et al

- Wolpert M ,

- Fletcher A ,

- Hargreaves J

- Humphrey N ,

- Wigelsworth M

- Rudasill KM ,

- Snyder KE ,

- Levinson H , et al

- Jessiman T ,

Twitter @BarkingMc, @russellviner

Contributors RB wrote the initial article which was scoped during the initial phase of work for an NIHR-funded Public Mental Health Programme. The draft was commented on by GH, CB, ME, KL and RMV.

Funding This article was compiled as part of a scoping study undertaken within the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) School for Public Health Research (SPHR)-funded Public Mental Health Programme (grant reference: SPHR-PROG-PMH-WP6.1&6.2). NIHR SPHR is a partnership between the Universities of Sheffield; Bristol; Cambridge; Imperial; and the University College London; the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine (LSHTM); LiLaC–a collaboration between the Universities of Liverpool and Lancaster; and Fuse–the Centre for Translational Research in Public Health, a collaboration between Newcastle, Durham, Northumbria, Sunderland and Teesside Universities.

Disclaimer The funders had no role in the design of the study, or collection, analysis and interpretation of the data, or in the decision to publish, or in writing the manuscript.

Competing interests None declared.

Provenance and peer review Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Read the full text or download the PDF:

- Open access

- Published: 30 March 2022

School culture and student mental health: a qualitative study in UK secondary schools

- Patricia Jessiman ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-5805-2415 1 ,

- Judi Kidger 1 ,

- Liam Spencer 2 ,

- Emma Geijer-Simpson 2 ,

- Greta Kaluzeviciute 3 ,

- Anne–Marie Burn 3 ,

- Naomi Leonard 1 &

- Mark Limmer 4

BMC Public Health volume 22 , Article number: 619 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

29k Accesses

15 Citations

5 Altmetric

Metrics details

There is consistency of evidence on the link between school culture and student health. A positive school culture has been associated with positive child and youth development, effective risk prevention and health promotion efforts, with extensive evidence for the impact on student mental health. Interventions which focus on socio-cultural elements of school life, and which involve students actively in the process, are increasingly understood to be important for student mental health promotion. This qualitative study was undertaken in three UK secondary schools prior to the implementation of a participative action research study bringing students and staff together to identify changes to school culture that might impact student mental health. The aim was to identify how school culture is conceptualised by students, parents and staff in three UK secondary schools. A secondary aim was to explore which components of school culture were perceived to be most important for student mental health.

Across three schools, 27 staff and seven parents participated in in-depth interviews, and 28 students participated in four focus groups. The Framework Method of thematic analysis was applied.

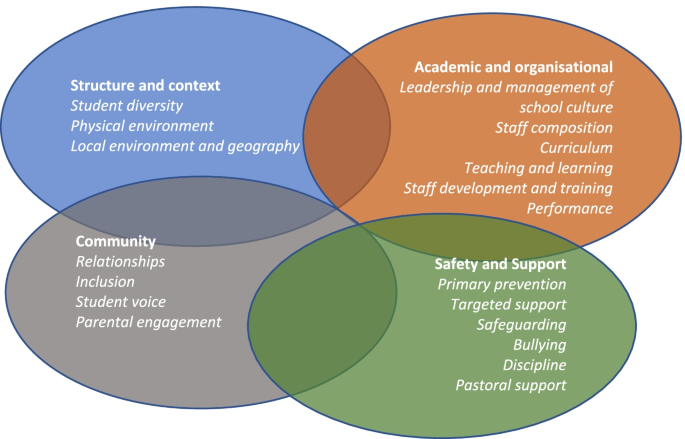

Respondents identified elements of school culture that aligned into four dimensions; structure and context, organisational and academic, community, and safety and support. There was strong evidence of the interdependence of the four dimensions in shaping the culture of a school.

Conclusions

School staff who seek to shape and improve school culture as a means of promoting student mental health may have better results if this interdependence is acknowledged, and improvements are addressed across all four dimensions.

Peer Review reports

Schools are key settings for health promotion, and the concept of a health promoting school has been supported globally [ 1 ]. This holistic approach involves not only health education via the curriculum but also having a school environment and ethos that is conducive to health and wellbeing, and by engaging with families and the wider community, recognising the importance of this wider environment in supporting children and young people’s health. There is evidence of positive effects on physical health (including weight, physical activity and diet), and limited evidence for the impact of the health promoting school approach on student mental health [ 2 ]. This matters; approximately half of adult mental disorders begin during adolescence [ 3 ], making these early years of life a key time at which to intervene to support good mental health, and to prevent or reduce later poor mental health outcomes.

Discreet mental health interventions delivered in schools often focus on improving individual students’ capacity for resilience, empathy, and communication skills and less on school-level factors [ 4 , 5 , 6 ]. A systematic review of school-based stress, anxiety and depression interventions in secondary schools found that while those aimed at reducing anxiety and depression were often successful, effect-sizes were mediated by student demographics and dosage, and effects were not long lasting. There was no evidence that interventions targeting stress were effective [ 7 ]. The limited impact of discreet mental health interventions may be because they do not address aspects of the school context or system that are determinants of poor mental health, or prevent the intervention becoming embedded [ 8 ]. Interventions which focus on socio-cultural elements of school life, and which involve students actively in the process, are increasingly understood to be important for student health and wellbeing [ 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 ]. Mental health promotion, defined by the World Health Organisation as actions to create an environment that supports mental health [ 13 ] is likely to be best achieved in schools that offer a continuum of interventions, including a focus on social and emotional learning, and the active involvement of students [ 14 , 15 ]. Markham and Aveyard’s theory of health promoting schools proposes that health is rooted in human functioning, which itself is dependent on essential capacities, the most important of which are practical reasoning and affiliation (human interactions and relationships) [ 16 ]. These, alongside other (less essential) capacities, make autonomy possible, and allow individuals to maximise their health potential. This is further supported by a systematic review of theories of how the school environment influences health which concludes that for young people to make healthy decisions, they must have autonomy, be able to reason, and form relationships. These capacities are better developed in schools where students are engaged, have good relationships with teachers, and feel a sense of belonging and participation in the school community [ 17 ].

The school environment is often termed ‘school culture’ or ‘school climate’; both are used in education literature but neither are well defined and both often encompass many differing and nebulous aspects of the school ethos and environment [ 12 , 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 ]. Some authors use the terms interchangeably; conversely they are also described as separate but overlapping concepts [ 22 ]. Van Houtte and Van Maele conclude that ‘climate’ is the broader of the two constructs, encompassing infrastructure, social composition, physical surroundings and culture itself, while ‘culture’ is focused on the shared assumptions, beliefs, norms and values within the school [ 23 ]. Rudasill and colleagues propose a Systems View of School Climate (SVSC) as a theoretical framework for school climate research, itself heavily influenced by Ecological Systems Theory [ 24 , 25 ]. They define school climate as “composed of the affective and cognitive perceptions regarding social interactions, relationships, safety, values, and beliefs held by students, teachers, administrators, and staff within a school.” Wang and Degol reviewed the existing literature and consulted with expert scholars to construct a conceptualization of school climate that includes four dimensions: academic (teaching and learning, leadership, professional development); community (quality of relationships, connectedness, respect for diversity, partnerships); safety (social and emotional safety, physical safety, discipline and order); and institutional environment (environmental adequacy, structural organisation, availability of resources) [ 21 ]. In our study, we use the term culture rather than climate deliberately; in a UK context, the term “culture” is far more commonly associated with school environment than “climate” [ 26 ]. We use “culture” to capture the broad sense of shared norms, values and relationships specific to each school, and also how student feelings of belonging, safety and support are impacted by the infrastructure and social composition of schools (considered by Van Houtte and Van Maele as part of the broader construct of ‘climate’ [ 23 ]).

A positive school culture has been associated with positive child and youth development, effective risk prevention and health promotion efforts, with extensive evidence for the impact on student mental health [ 23 ]. Two evidence reviews report strong associations between the student perceptions of the quality of interpersonal relationships within the school, and school safety, and student mental health [ 18 , 21 ]. School culture may be particularly important to the mental health of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender students who may be more likely to perceive it less positively and be at greater risk of poor mental health, feeling unsafe, and absenteeism [ 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 ].

Given the evidence base highlighting the importance of school culture and active participation of students in school life on mental health promotion [ 9 , 10 , 31 ], we developed a participatory action research (PAR) approach [ 32 ] to understanding and improving school culture in UK secondary schools. Participatory Action Research seeks to enable action within a specific research context by involving study participants as co-researchers. Undertaken in three English secondary schools, our study involves bringing together a small group of students and school staff, facilitated by an external mental health practitioner, to develop a shared understanding of the culture in their own school, and identify changes that might impact student mental health. Participants consider school culture and student mental health, implement changes and/or interventions intended to improve both, and reflect on whether these changes have had an impact. This means that participants are involved in a cycle of data collection, reflection, and action (Act-Observe-Reflect-Plan cycles; [ 33 ]. Further information about the PAR study is available elsewhere, including the study protocol [ 34 ] and the use of PAR as a research method [ 34 , 35 ]. At the launch of the PAR intervention, staff and students were asked to reflect on their conceptualisation of school culture in order to develop a shared understanding. Alongside this, the research team undertook qualitative research in each of the intervention schools. Given the differences in the definition and conceptualisation of school culture identified in the literature, we wanted to better understand how it is conceptualised by those most closely impacted by it. The aim of the current study is to identify how school culture in conceptualised by students, parents and staff in three UK secondary schools. A secondary aim is to explore which elements of school culture are perceived to be most important to student mental health.

This was a qualitative study using semi-structured interviews and focus groups as the primary data collection method. We have followed the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ) checklist [ 36 ].

Research team

The study research team comprised academics from public health centres at four English universities. The development of data collection tools was led by PJ; data collection was led by PJ, LS, and EGT; all of the research team were involved in analysis and reporting.

Sampling and recruitment

We used a purposeful sampling approach to select schools with variability in school performance (using Ofsted inspection outcomes as a proxy measure for this), and diversity of student intake across ethnicity, and eligibility for free school meals. Three secondary schools were recruited in October 2020, one of which agreed to run two PAR intervention groups. A lead staff contact in each of the schools supported the recruitment of school staff, parents, and students to take part in an interview (adults) or focus group (students), prior to the PAR groups beginning. We worked with this contact to identify school staff with insight into school culture and student mental health and wellbeing. Participants were drawn from the senior management team, teaching staff, other support staff, particularly those with responsibility for student wellbeing (e.g. pastoral support staff, Personal, Social, Health and Economic education (PSHE) lead, head of year, form tutor). For parent participants, we asked for parents with particular insight into the school, for example parent governors, parent volunteers, or those whose children had required extra pastoral support or similar. Potential interviewees were sent a Participant Information Sheet (PIS) that detailed the objectives of the study, interview length and summary of topics covered, recording arrangements, confidentiality, and data protection details, and use of data for reporting. Participation in interviews was voluntary. A consent form was sent to participants by email in advance of an online interview and consent recorded at the start.

In each participating school, all students in the selected year group were invited to take part in the PAR group. School staff shared an information sheet about the PAR group and encouraged students who wanted to take part to contact school staff and also send a short paragraph detailing why they wanted to take part and what skills and attributes they would bring to the group. School staff selected students with guidance and support from the research team (prioritising diversity across gender and ethnicity and those students who were not already involved in any student councils or similar in the school). Students who had volunteered to take part in the PAR intervention, but not selected, were asked if they would participate in the focus group. An information sheet was sent to both students and their carers and consent sought from both to participate (in one school, parents were informed but consent not sought as students were aged 16 years or over). Signed consent forms were collected prior to the focus group and the researchers reaffirmed that consent was informed and voluntarily given verbally at the start of the focus group.

Data collection

Semi-structured interviews support a structured and flowing interview whilst allowing some flexibility to ensure the respondent can engage with the subject, maintaining more autonomy in how they choose to respond to the topic areas in comparison to a more structured survey method (Adams 2015). Topic guides for the interviews were developed following a rapid review of the research literature on school culture to develop a comprehensive list of components that may impact on student mental health, as well as potential mechanisms through which this may happen (see Additional file 1 : Appendix 1). Interviews lasted 30–45 min and guides were used flexibly, using prompts and probes where appropriate. A similar approach was used to develop the topic guide for student focus groups, which included participatory methods to facilitate a discussion about school culture. Focus groups lasted around 45 min.

Data collection took place between December 2020 and April 2021, coinciding with school mitigation measures in place in response to the COVID19 pandemic. These included social distancing, face masks, and year group ‘bubbles’. Although schools were open to all students when data collection began, they were closed to all but vulnerable students and those with key worker parents from the beginning of January until March 2021. As a result, all data collection with school staff and parents took place online. Student focus groups occurred after schools re-opened were a mixture of face to face (3 groups), and online (1 groups) depending on what the school allowed.

All data collection activity was recorded using an encrypted digital recorder and transcribed verbatim. We used the Framework Method of thematic analysis [ 37 , 38 ]. One of the researchers (PJ) developed a thematic framework after reading several transcripts to familiarise herself with the data and referring to the research questions and topic guide to inform an initial coding stage. This framework was augmented by subthemes that emerged in further transcripts. A short summary of each subtheme was developed to describe the data that it was designed to capture. This initial framework was shared with the whole research team and the thematic framework was further refined until the team were confident that it encompassed all the data in the transcripts, the data within each subtheme was coherent, and that there were clear distinctions between subthemes. The final thematic framework is included in Additional file 2 : Appendix 2. PJ then developed a matrix framework, using the subthemes as column headings and participant transcripts as rows. The matrix cells were populated with verbatim and summarised data from the transcripts, as well as analytical notes made by the researchers (‘charting’). Charting reliability was tested by all six researchers charting the same two transcripts independently, and comparing the contents of each cell to ensure that we were applying the subthemes consistently and capturing and summarising the data consistently across all team members. This data management approach produced a data matrix showing data from every respondent under each subtheme, thus providing a detailed and accessible overview of the qualitative dataset. The Framework Method makes possible the capacity to explore the dataset through themes and subthemes, and also by respondent type. A summary of the data under each subtheme was developed to inform the next stage of the analysis, moving up the analytical hierarchy to explore patterns and associations between themes in the data [ 38 , 39 ].

Information about the sample schools and participants is shown in Table 1 .

Across all three schools, 27 school staff participated in an interview for the study. Staff interviewed included members of the senior leadership teams, teaching staff, learning and support assistants, pastoral support staff, and staff with particular responsibility for the Year group which was taking part in PAR in each school. The parent sample was comprised of seven parents of students in the relevant year groups across the three schools (five mothers, two fathers).

Four student focus groups were held in total; one from each of the year groups participating in PAR across the three schools. Twenty-eight students took part across the four groups; student demographics and online/in school data collection method are outlined in Table 2 .

The findings are presented under four overarching dimensions of school culture that emerged from the data and were perceived by respondents to impact on student mental health. These are structure and context, organisational and academic, community, and safety and support (see Fig. 1 ). Anonymised quotations are included from a wide range of participants in order to illustrate the responses rather than indicate representativeness. Where differences between participant groups were apparent (e.g. parents, school staff and students) we highlight these in the findings.

Dimensions of school culture

Dimension 1. Structure and context

Local environment and geography.

School staff noted the impact of geographical location on school culture, with pupils often not living in the immediate locality. This resulted in students living socially deprived areas attending a school in an affluent area, and vice versa. As a result any sense of a school sited within a ‘neighbourhood’ or ‘local community’ setting was depleted. However the impact of the wider locality was recognised. Public events and demonstrations that had occurred in the South-West of England in the 12 months preceding the study generated publicity and awareness amongst the students at all three schools, which staff tried to reflect and respond to.

“So, being in a city centre, if there’s a protest, it’s on our doorstep. So, the student strikes, on our doorstep, Greta Thunberg, when she came, on our doorstep, Black Lives Matter protests, on our doorstep…[]…So, all these issues, our students are even more exposed to, and, you know, in shaping our culture at school, that’s what we’ve tried to move towards. Not just focussing on inclusivity and care, but also in terms of they’re going to be engaged and informed citizens.” School B staff 8

Student diversity

Almost all respondents referred to the three schools as having a very ethnically diverse student body, bringing both opportunities and challenges. Ethnic diversity was perceived by most respondents as one of the key influences over school culture. Parents often spoke of valuing it as a learning opportunity for their children, and a source of high cultural capital. Many staff shared this view and enjoyed working with such a diverse cohort.

“The cultural mix at [School A] was really important for me...So culturally, I think the diversity in [School A] is amazing and although it brings with it many challenges, that was a really important thing for me. That my children could see the struggles. I think it is more of a reflection of society…modern society, multicultural society.” School A parent 1

Many staff noted however that while students may integrate during school hours, they often fell back into homogenous groups at the end of the school day, reflecting the reality of the wider community.

“This is a diverse school, and the city is sometimes perceived to be a diverse melting pot but it is not, it is still very segregated. There is a lot of work to be done between communities.” School C staff 5

There was also diversity across the socio-economic status of students. Staff reflected on the severe poverty faced by many of their students, exacerbated during the COVID19 pandemic, and the efforts made to ensure that students were able to access the same educational and wider opportunities as more affluent students. Staff also reported examples of where ethnicity and socio-economic status intersect, impacting the engagement of students and their families with the school.

“For some BAME families, education is the highest priority. For others who are possibly asylum seekers or who have not really had an education themselves because of issues back home in their own countries, education is much further down the list. You’ve got other families, massive poverty in the families, and so education is the last thing they can think about.” School C staff 4

Finally staff also noted the influence of students with SEND on school culture. Two schools in particular were perceived to have a high proportion of students with SEND, and staff adapted the curriculum and employed additional support staff to ensure the school environment and offer was inclusive. This included working with all students to promote greater awareness and acceptance of disability.

Physical environment

Many staff spoke about the impact of the physical environment of the school on student interactions and wellbeing, and in particular the impact of being quite constrained in a small space. Although efforts were made to create private and safe spaces during break times, often both the number of people, and building and grounds design made it difficult for students to find quiet or perceived safer places to be. This finding emerged in all schools, despite one being an older, traditional building and two being more recently rebuilt to incorporate more light and space.

“Students do struggle with the building sometimes - a big long tin, built around previous ideas of supervision. So offices are glass, toilets are open, they are non-gendered toilets which are open aside from cubicles, but does mean we are restricted on indoor space - not many places where kids can just sit and relax in social time…So, I think that that’s something they do struggle with.” School C staff

Students’ capacity to navigate school buildings was further constrained during the pandemic by social distancing measures. Students were often confined to one classroom all day while teachers moved round the school, one-way systems were put in place, and dining areas and school grounds segregated by year group to limit social mixing. Staff perceived this impacted on the school culture, making small incidents amongst students more likely to escalate, and removing teachers’ sense of control in classrooms that no longer felt like their own.

“All of a sudden they’re crammed, 30 students, into [one] classroom [all day] and I think that’s had a negative influence on a lot of students….[]… As a result small things escalate fairly quickly, which isn’t helping the dynamic within the school. …[]… Before, every time I ever had a class, I would be at the door. I would welcome them into my room, and there’s an automatic element of control and influence where, if there is something, you can address it before you come into the room and the room is the area of control. There isn’t that available anymore, and I thought that that does have an impact.” School A staff 7

Dimension 2. Organisational and academic

Leadership and management of school culture.

The role of the school senior leadership team in shaping school culture was mediated through their support for staff, visibility and transparency to students, and active management of school culture. School staff reported that having a leadership team that listened to and empowered staff was important. This was especially important during the pandemic and related mitigation measures resulting in schools being closed to most pupils and a move to online learning, although for some staff this made the leadership teams less visible. Visibility to students was also seen as key to promoting a welcoming culture in schools; availability and presence during the school day was frequently mentioned by both staff and students.

“The senior leadership team are very visible to students. They’re out every single lunch and break, every lesson changeover, they’re very hands-on, and I would say that’s probably, I think that’s quite a good sign.” School A staff respondent 3

The importance of senior staff being present and welcoming students to school each morning was also perceived by student focus group participants as a reason for valuing their school.

Culture emerged as a key priority amongst the leadership team in all three schools, which all take a proactive stance on leading and shaping it, including having senior leaders responsible for it. Stated reasons for prioritising culture included to reflect the needs of a diverse student intake (particularly across ethnicity and socioeconomic status); mitigate the impact of Covid mitigation measures on student wellbeing; and in response to the UK national government’s push for better mental health provision in schools. There was also a sense that newer staff, and staff recently promoted to managerial posts, were more likely to prioritise culture (and student wellbeing).

“I am aware of how important [mental health in schools] is at the moment from the government.” School A Parent 1 “It can be alienating, but they [new leadership team] spoke a lot about culture - something that people say is important, and in general staff are happy…[]...he [Principal] he would start using these quotes from people, and one of the ones that always sticks in my head is ‘culture eats strategy for breakfast’, is one he loved which, again, is on culture.” School C staff respondent 9

Despite the active management of school culture, there were staff in all schools who questioned whether a narrative of prioritising school culture was tokenistic, without implementing real changes or having noticeable impact.

Staff composition

School staff composition was perceived to influence the culture of the school, and mental health of students, through dedicated pastoral and inclusion roles, their ethnic and gender diversity (or lack of), and staff turnover rates.

All three schools had non-teaching staff with roles dedicated to supporting student mental health and wellbeing, including safeguarding (promoting child welfare and protection from harm), pastoral support, mental health support (counsellors), and support and inclusion for pupils with special educational needs and disabilities (SEND). Staff and parents from two schools perceived the wellbeing teams as unusually large compared to other secondary schools. These staff were especially busy monitoring and supporting students during school closures. The importance of staff dedicated to mental health and wider wellbeing support was recognized by all stakeholder groups, including parents.

“The fact that she [pastoral support lead] doesn’t teach any of them and that they know they can just drop in and they can just go and sit down and say, “I’m having a rubbish day today.” Sometimes that’s what you need. You don’t always need someone to come up with an answer. You just sometimes need somebody to listen.” School B Parent 1

Beyond dedicated non-teaching staff, many school respondents recognised the role that staff diversity had in shaping and informing school culture. Respondents in all schools were conscious that school staff did not reflect the ethnic diversity of students. Gender representation across teaching subjects and leadership roles was also of concern. There was recognition amongst school teaching staff and leadership teams that students need to see ethnic minority and female role models in all roles, and effort is needed to address this through better recruitment practice.

“It's the best leadership team I’ve ever worked in [but] If we're talking about representation in there, I am the only non-white person in our leadership team...[]… It's only really in our pastoral teams where we start to see some diversity. That's a real problem in schools that I've always found, is that any kind of black or ethnic minority staff tend to be in the pastoral teams rather than in the teaching and learning teams.” School C staff 5

Parent respondents highlighted staff turnover and consistency as important. When staff consistency was low, this had a negative impact on students’ wellbeing and school culture as they struggled to build relationships with ever-changing staff. This was particularly important to students who needed additional pastoral and/or inclusion support for SEND or mental health reasons, and also impacted on parents’ ability to build trust and confidence with their child’s key staff contacts in school.

Staff development and training

Few respondents mentioned staff development and training as an important aspect of school culture, although some school staff did raise training in specific areas that would influence their capacity to support student mental health and wider wellbeing (including on safeguarding, mental health promotion and prevention, inclusion, and support for students with SEND). Some reported training in new behaviour management policies specifically intended to impact school culture, including restorative justice and holistic approaches. In one school effort had been made to train staff in anti-discriminatory practice, to give them greater confidence in addressing diversity-related issues and supporting students.

“We need to make sure that, on every bit of our culture that we want to work on, we have staff that are educated in that. I know we've done a lot of work on this year’s staff feeling scared to broach certain subjects, especially with our anti-discriminative practice… They're worried about saying the wrong thing and being accused of being a racist, or being accused of being a homophobe, or being accused of saying something. There's a real fear of that, which I think leads to disengagement, potentially, from trying to be an active participant in the change [to school culture].” School C staff 5.

Respondents across all schools described ongoing changes towards a more inclusive, holistic curriculum, reflective of the diverse student body. The most prominent changes to emerge from interviews were efforts to decolonialise the curriculum across all taught subjects, the inclusion of more content about Black history, and inclusive and diverse content with regard to gender and sexuality. In one school, changes to the curriculum were informed by feedback from student Black and Minority Ethnicity (BAME) and lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender (LGBTQ +) groups. Staff respondents noted the importance of embedding minority role models across all subject areas, and not simply providing one-off lessons about minority groups. The lack of diversity amongst staff increased the difficulties of delivering a diverse and inclusive curriculum as many reported lacking expert insight, knowledge and confidence. There was consensus however that continuing to work on the curriculum offer was likely to facilitate a more supportive school culture.

“So, we’re working at the moment unit of work by unit of work by just inputting BAME and female role models and careers. So, that it’s not a tokenistic lesson, it’s actually… it just becomes part of the normal conversation at [School C], and no matter what ethnic group a pupil is from or what their sexuality is, there should be, within the curriculum somewhere, role models popping up…, it becomes part of the day to day conversation.” School C staff 2

PSHE education was highly valued by both staff and students as an important means of addressing diversity, inclusion, and health. PSHE time was used to deliver universal mental health provision including education, advice, and interventions such as meditation or mindfulness. Students reported that alongside Relationships and Sex Education (RSE), this helped them to develop an understanding of different cultures and to be mindful and respectful of them.

“I think RSE, PSHE are good because they teach about other people’s cultures and I think it is important since that- say if you don’t know something about another person’s culture you might offend them.” School C student focus group

For some students, the opportunity to discuss mental health during PHSE was welcomed but could feel tokenistic, without enough time to cover issues in depth, and some stigma around discussing mental health remained.

“We had a PSHE assembly quite recently and this is going back to the whole 'surface level' thing, because even though the assembly itself was good, it was, like, all the students [in year 12] in one Zoom. So, it was very difficult for us to have actual, proper, discussions. So, it felt quite, "See, we need to have a PSHE lesson at some point, therefore we'll have one big, fat assembly, so we can tick that off our quota," instead of having smaller groups where people can actually discuss their problems and really learn.” School B student focus group

Staff, parents and students all discussed the importance of non-academic subjects such as Physical Education (PE), Music, Dance and Art, and the ability for students to access these formally through lessons and through lunchtime and after-school clubs. The noted benefits of these include providing an opportunity for self-expression and creativity, a focus on processes rather than outcomes (an important part of mental health), and ‘safe’ spaces to take risks and use failures as opportunities. Staff perceived that having a wider range of music, arts and sports on offer to students allowed them an opportunity to find something they enjoy and may excel in, which may be particularly important for the self-esteem of less academically able students. Respondents across all schools noted that although schools make efforts, there was still not enough emphasis on these wider curriculum areas, and this was exacerbated by the curtailment of after-school and extra-curriculum activities during the pandemic.

Teaching and learning

Most respondents’ comments on teaching styles focused on teachers’ attitudes to discipline in the classroom. Where teachers were perceived as overly strict, students and parents worried that this had a detrimental effect on student mental health. Some students and parents perceived that teachers’ focus on academic performance meant they were more likely to overlook student anxiety and stress.

“For some reason I think [daughter] overthinks things maybe and she second guesses everything she does…[]… They’d set the essay and then she’d spend another week researching which she didn’t need to do. Then she’d start writing the essay by which time other work was coming in, so it got on top of her….[]…She was scared of failing. She was scared of letting them down.” School B Parent 1

The COVID-19 pandemic may have alleviated this problem and encouraged teaching staff to afford greater consideration of student mental health. Staff were aware that not all students coped well with the closure of schools and move to online teaching and learning for extended periods of time alongside the other stressors of the pandemic.

“I’ve spent a lot of time on the phone with parents, and sometimes their kids are having a really tough time and they are ditching the distance learning thing. I’m just like, “You know what? Your kid needs to feel better and then we’ll look at the learning again.” School C staff 3

Academic performance

Pressure on schools to be ‘high performing’ was driven both by external regulators and national performance measures (Office for Standards in Education, Children's Services and Skills (Ofsted); Progress 8 scores (progress a pupil makes from the end of primary school to the end of secondary school), and school staff’s ambition to equip individual students with the skills and qualifications for later life. Respondents also noted the impact of schools’ local and historical context; comparisons with other schools in the area (e.g. higher performing schools more attractive to prospective students and parents) and prior status (e.g. as a grammar school, private school or under-performing school) also influenced how the schools’ current academic performance was perceived by parents and staff. All of this influenced how ‘high performance’ was conceptualised. In one school, staff and parents describe the school as highly academic with an expectation that most students would achieve high academic grades and proceed to higher education. In contrast, staff from a school with lower academic outcomes noted that they are driven to maintain year on year improvements in Progress 8 scores, (a ‘value added’ measure) and equip students for a wider range of next steps, including further education, and vocational routes.

“It is a very high-end sixth form. So you are working with a lot of young people that want to be doctors, vets, quite high-end.” School B staff 4 “We were one of the only schools of our kind, really, to see a… I think it for six years, an improvement in our progress 8 scores, which I know are not everything, but actually are quite a good measure for us. We’re an academy that is massively based around progress, and equal progress.” School C staff 2

Respondents of all types were aware of the impact of high academic expectations on school culture and consequently, student mental health. In school B, which is known for high academic standards, staff reported high levels of anxiety and stress-related disorders amongst students, including eating disorders and self-harming behaviour. School staff acknowledged that expectations of high achievement can cause students stress and anxiety, but addressing this is challenging because it is not always driven by the school culture but by parents or the students themselves.

“There is a big, big drive for students to apply to Oxford or medicine degrees, dentistry, and in my experience this has caused some significant mental health issues in the students. It’s not necessarily a school issue, I would say it’s more due to the demographics of the students that attend the school. They tend to come from very supportive families, often families that actually want the students to attend Oxford or want the students to be doctors... So there is still this sort of competition with their peers and maybe the frustration of not meeting expectations that come from the parents.” School B staff 6

Dimension 3: Community

Quality of relationships in school.

The quality of interactions and relationships with others in school was perceived as another key element of school culture important to student mental health. Staff respondents distinguished between ‘staff’ and ‘student’ culture, though also recognized that the relationships between staff and students would impact on the school culture overall. Relationships amongst staff were generally described as friendly, supportive and collaborative. This was especially important during the past months when school closures necessitated the move to online teaching, with repercussions for students through better practice, and better support.

“It’s really noticeable that no matter what department you’re in, what level of teaching, if you’ve got your head around something that other departments or individuals haven’t, people have voluntarily made tutorial videos and just sent them to all staff, it’s not that you have to go knocking and asking all the time, actually people are just pulling together and trying to promote best practice.” School C staff 2

There was some disagreement over the role of the senior leadership team in reinforcing positive staff culture. Some respondents described working with an empowering leadership team that actively supported good staff relationships. For others, leadership influence over high workloads, pressure to maintain high academic performance, pandemic-related changes and recent staffing decisions (including redundancies) had damaged relationships amongst staff. There was also some stigma around disclosing mental health concerns, particularly those caused or exacerbated by work pressures, although this may be improving.

“Lots of people are worried about the consequences [of disclosing] and they’re worried about having the label of someone who cannot cope, there’s a lot of that.” School B staff 6

The quality of interactions between students and staff were perceived as highly influential over how students experienced school culture, and to their mental health. There was recognition amongst school staff that while those in pastoral or other support roles would prioritise maintaining good relationships with students, teaching staff may differ in their perception of their role; some would focus on teaching and learning only, while others would see the creation of positive and trusting relationships with students as important and conducive to better learning and healthy development. Other influences on the quality of relationships between staff and students included pressure on staff and students to maintain high academic standards. Staff willingness to be accessible and approachable to students was also important, and this had been adversely been affected by school closures and subsequent social distancing measures in place in school.

“Relationships between student and staff are really important, because if you don't really have a good relationship with your teacher, you may feel uncomfortable with asking them for help. It can cause a lot of stress if you're beginning to struggle and you don't get any help.” School B student focus group

Inclusion and diversity-related factors were key; staff from schools with a more ethnically diverse student intake reported that the lack of diversity amongst staff damaged relationships with students from minority groups. There was also concern that Black and Minority Ethnicity students were over-represented in disciplinary statistics, possibly a result of unconscious bias or prejudice from staff.

“In our school, when almost all staff are White and then you’ve got an over-representation of Black students in our behaviour data, race becomes an issue. Not just for the students, but for parents as well. That is something we’re continually trying to overcome and work on.” School A staff 1

Friendships with peers and the quality of interactions between students in school were also recognized as having an important influence on school culture and student mental health by all stakeholders. Respondents across all schools generally described peer relationships as positive, though there was recognition that individual students would have different experiences.

“If you have good relationships with other students, then your mental health will just, overall, feel better. You'll have someone to talk to, someone to rely on and you'll just, overall, have a better experience at school.” School B student FG

Diversity, particularly ethnic diversity, was seen as very influential over peer relationships by staff and parent respondents. As noted earlier, it is valued as a key attribute of a school and there is an expectation amongst staff and parents that students will benefit from relationships with peers from different backgrounds. They also report that peer support is strong amongst minority groups, and students with SEND and minority ethnic groups looking out for and supporting each other. However, where problems arise in student relations this is generally attributed to differences across ethnicity, age, gender or disability (with SEND students at particular disadvantage). Respondents describe concerns with discrimination amongst peers in all three schools, which can manifest in a lack of integration during social and break times, and bullying.

Efforts to promote inclusion were apparent in all schools, as this was perceived to be another key influence on school culture and student mental health. Across all schools, respondents describe a diverse student intake with regard to ethnicity, socio-economic status, geography, and religion. This was highly valued; forming peer relationships across these divides is seen as an opportunity for students to learn from each other and encourage acceptance and valuing difference. Staff from all schools reported an emphasis on inclusive practices, driven by both the need to ensure that all students felt safe and welcomed in school, and by recent Black Lives matters protests that have highlighted awareness of prejudice and discrimination amongst students.

School staff were conscious that for many students, time in such a diverse environment was limited, and hence the opportunity to gain the most advantage should be optimised.

“We don't want people to tolerate each other…[]…We want to teach you to celebrate, actually, differences, and learn from each other and be able to have high cultural capital, based on you've got this experience to come to this environment every day where you're mixing with so many different people that maybe, once you leave school, you're not going to be able to access.” School A staff 5

Staff were keen to emphasise the activities undertaken promote inclusion, such as running groups for under-represented or minority students, (e.g. BAME and LGBTQ + students), increased pastoral support for minority groups, events/displays to celebrate diversity and difference; ‘stamping down’ on issues of intolerance and bullying, and the provision of unisex toilets. There was some recognition of the intersectionality of race, gender and sexuality.

“Quite often, we find that if you belong to a BAME community, talking about or being open about your sexuality can sometimes be a big no-no…[]…We’ve got a lot of children, students from the BAME community that aren’t out, but actually want to go to the LGBTQ club group to learn and talk and debate and discuss and learn more about themselves. So, you know, making sure they do that in a safe place.” School C staff 4

School staff perceived some improvements were still to be made, including increasing the ethnic diversity of staff, and addressing potential staff bias that may result in BAME groups being over-represented in disciplinary actions. Staff also report increasing incidences of misogynistic language and bullying amongst students, and this may be the next inclusion issue to be targeted. Students recognise the work that schools are doing around inclusion and value it, although agree that there is still some progress to be made.

“The school discourse is specifically- I feel like the school used to be a very majority white school and it is slowly integrating and becoming a more culturally diverse school. So, I think the school, in itself, is still learning how to make different cultural identities more heard, more safe, more whatever, but I think the school definitely has a lot more to learn and to do.” School B student FG

Student voice

Student voice and empowerment mechanisms and the success of these varied across the schools and again, were impacted by the pandemic mitigation measures. There was consensus amongst school staff that the degree to which students felt listened to was a key aspect of school culture which would impact on student-staff relationships and student mental health. All schools had systems in place for consultation with and engagement of students (for example student councils). Staff also reported using surveys as a regular means of monitoring student health and wellbeing and gaining feedback on specific issues. There were examples of student-led groups, for example BAME or gender equality groups, being involved in changes to the curriculum or school rules that which particularly affected these groups.

School staff varied in their perception of effectiveness of these mechanisms, with some reporting that school leadership teams were responsive to student feedback and willing to reflect student views. Student councils and surveys had been disrupted during school closures, although respondents across all schools reported that changes had been made to practice (for example, how online learning was delivered), as a result of student feedback. This was a minority view however; the majority of respondents perceived that student views were often ignored and had little tangible impact on the how the school was run. Some attributed this to a lack of staff resource devoted to facilitating and supporting student engagement; conversely other staff report that too much engagement work is staff-led, rather than student-led.

The overwhelming perception of students and parents is that school leadership teams are unwilling to engage with and reflect student views.

“My personal experience of school councils is that they are a bit of a- we all have a school council because we know it’s the only thing to do but actually when it comes to decision making they kind of ignore it or they’ll steer the kids in a direction they want to go.” School A parent 1 'I feel like they try to say that they do a lot [around student voice], especially with student leaders and stuff, but a lot of the ideas and rules that we might want to change get shut down real quick.' School A student FG

Parent engagement

Parental engagement was perceived as good across all three schools. Mechanisms included parent forums, parent teacher association (PTA), email newsletters and social media groups. School staff also liaised with parents of students over specific issues (typically about academic, behavioural, health or SEND support). The degree of communication and engagement with parents increased during the pandemic, as staff conducted additional and regular welfare checks while most students were not attending school in person.

There was recognition that some parents were more willing and easier to engage with than others; factors influencing this include parents’ motivation for their child’s academic success, concern about student support needs, and ‘second generation’ students whose parents also attended the school. The relationship with some parents could be challenging for school staff, either because parents are reluctant to engage, may blame school staff for their child’s behavioural issues or be critical over the perceived lack of support for their child. Engagement was also perceived to vary across socio-demographic status and ethnicity. Some staff reported that higher earning families may have greater expectations of their child’s academic success and will seek out opportunities to engage with school staff to facilitate this. In one school, concerns about problematic disengagement of parents from one particular community was addressed by the employment of a family support worker to liaise between families and schools to help overcome language and cultural barriers.

Most parents were pleased with the level of engagement they had with school staff, particularly where their child had additional needs or existing mental health issues. They report feeling listened to by school staff, who were quick to respond to issues and make necessary changes, making parents feel like they are working together with staff in the child’s best interests.

“I feel they always know who I am, they know, when I talk about my children they seem to know everything that I’m talking about, and they’re always quick to respond. They actually take you seriously - they sort of think: “Well you’re the parent, you must know your child so tell us what we can do to help.” And I just find that really helpful.” School A parent 3

Students were aware of parental communication, especially where this was concerned with behaviour or achievement. Many appreciated school staff contacting their parents with positive feedback about them. Students were clear about the links between positive feedback from the school, their parents, and their mental health.

“Keeping in touch with parents is really important - I would say keeping in touch with parents as when they tell your parents that you’ve been excellent it raises your self-esteem and makes you feel like your parents are proud of you which makes you feel proud of yourself.” School C student focus group

Dimension 4: Safety and support

Pastoral support.

As previously noted, schools all had designated staff for student wellbeing and pastoral support.

Most staff were confident that students would know who to approach, usually a tutor or a member of the pastoral support team. Pastoral staff report being especially busy during school closures, conducting regular welfare checks on all students, and providing additional support for those in need. The pandemic mitigation measures made providing pastoral support harder, by limiting in-person contact while schools were closed, and use of face masks making communication harder.

“It’s been harder this year because of closures and mask wearing - there’s still a swathe of other [students] that don’t have a connection. You only need a strong connection with one staff member to feel like you’re supported, valued and have someone that you can go to.” School B staff 8

Parents were universal in their praise for the pastoral support provided to their children, with staff seen as skilled and responsive to both student and parental needs. Students’ views were more mixed, with concerns about anonymity, embarrassment about raising mental health issues in school, unwillingness to approach pastoral staff where they were also teaching staff, and having better support systems in peer groups or at home.

“There are pretty much only one or two people that I would tell private stuff to, and it definitely isn’t any of the teachers.” School A Student focus group

Primary prevention

Most school staff describe two main mechanisms for mental health promotion; speaking often about the importance of good mental health, and ensuring students in need of support know who to approach for help and guidance at the earliest opportunity. Mental health is addressed during assemblies, as part of the PHSE curriculum. and in tutor time. School staff also used these opportunities to communicate support available to students both within the school from external agencies (via face to face, telephone or online). Teaching staff also have a role in promoting good mental health by having an accessible ‘open door’ policy for students, and being aware of, and not putting further pressure on, students with known mental health issues. Schools also frequently used noticeboards, websites and student newsletters to communicate about mental health.

“We do things like toilet door campaigns in our school. The inside of toilet doors are just covered in different posters and stuff like that. They’re unisex open-plan toilets. So, we’re targeting everyone with everything”. School C staff 4

Respondents often commented on the stigma attached to mental health difficulties, and like staff, students may be reluctant to talk about them in school. This was perceived as particularly true for students from some ethnic minority communities. Staff believed that talking often about the important of mental health would encourage students to ask for support if they needed it. Some staff report that as mental health awareness increased, students were becoming more likely to report issues about themselves, or for other students.

“In terms of preventative support, I want to say the kids really have each other’s back. I would say they really do. There have been lots of cases in the past of friends of students coming to me or going to [Name] or [Name] to say, “So and so is having a panic attack,” or, “So and so is having a tough time.” School B staff 6

All schools had processes in place to monitor student mental health though the degree to which this was formally structured varied. One had a range of pre-emptive measures in place including regular face-to-face monitoring by safeguarding leads or tutors, and monitoring through proxy measures such as attendance and engagement. School staff also mentioned the importance of staff communication to spot and support students needing support. Student feedback on this was mixed; not all students agreed that it is the role of teaching staff to monitor student mental health.

“I don't think it’s the teacher’s job to look after people’s mental health. I think their job is just to teach.” School A student focus group “There’s a survey asking you how well do you feel out of one to ten, do you need to talk to someone, how is it going, and all these questions….[]…I think that’s pretty good because then you can just answer it, even though it says your name, no one else is going to see it except the teacher which is fine because they’re the ones who help you.” School C focus group

Targeted support

Targeted mental health support was mainly comprised of access to a school counsellor or a mentor. School respondents often said they would have more targeted support available but this was unaffordable. Staff from two schools also mentioned targeted group interventions for anger management, stress and anxiety, body image, and understanding emotions. Again it was stated than this would be useful for all students as health promotion activities, but the resources were not available. Other barriers to accessing targeted support included pressure on curriculum time; staff reported difficulty in removing a child from a taught class to take part in a mental health intervention. Learning support assistants (LSA) for students with SEND were also perceived to provide high levels of mental health support. Students in all schools were aware of these support systems.