An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Int J Environ Res Public Health

Factors Influencing Abortion Decision-Making Processes among Young Women

Mónica frederico.

1 International Centre for Reproductive Health (ICRH), Ghent University, 9000 Gent, Belgium; [email protected]

2 Centro de Estudos Africanos, Universidade Eduardo Mondlane, C. P. 1993, Maputo, Mozambique; [email protected]

Kristien Michielsen

Carlos arnaldo, peter decat.

3 Department of Family Medicine and primary health care, Ghent University, 9000 Gent, Belgium; [email protected]

Background: Decision-making about if and how to terminate a pregnancy is a dilemma for young women experiencing an unwanted pregnancy. Those women are subject to sociocultural and economic barriers that limit their autonomy and make them vulnerable to pressures that influence or force decisions about abortion. Objective : The objective of this study was to explore the individual, interpersonal and environmental factors behind the abortion decision-making process among young Mozambican women. Methods : A qualitative study was conducted in Maputo and Quelimane. Participants were identified during a cross-sectional survey with women in the reproductive age (15–49). In total, 14 women aged 15 to 24 who had had an abortion participated in in-depth interviews. A thematic analysis was used. Results : The study found determinants at different levels, including the low degree of autonomy for women, the limited availability of health facilities providing abortion services and a lack of patient-centeredness of health services. Conclusions : Based on the results of the study, the authors suggest strategies to increase knowledge of abortion rights and services and to improve the quality and accessibility of abortion services in Mozambique.

1. Introduction

Abortion among adolescents and youth is a major public health issue, especially in developing countries. Estimates indicate that 2.2 million unplanned pregnancies and 25% (2.5 million) unsafe abortions occur each year, in sub-Saharan Africa, among adolescents [ 1 ]. In 2008, of the 43.8 million induced abortions, 21.6 million were estimated to be unsafe, and nearly all of them (98%) took place in developing countries, with 41% (8.7 million) being performed on women aged 15 to 24 [ 2 ].

The consequences of abortion, especially unsafe abortion, are well documented and include physical complications (e.g., sepsis, hemorrhage, genital trauma), and even death [ 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 ]. The physical complications are more severe among adolescents than older women and increase the risk of morbidity and mortality [ 6 , 7 ]. However, the detrimental effects of unsafe abortion are not limited to the individual but also affect the entire healthcare system, with the treatment of complications consuming a significant share of resources (e.g., including hospital beds, blood supply, drugs) [ 5 , 8 ].

The decision if and how to terminate a pregnancy is influenced by a variety of factors at different levels [ 9 ]. At the individual level these factors include: their marital status, whether they were the victim of rape or incest [ 10 , 11 ], their economic independence and their education level [ 10 , 12 ]. Interpersonally factors include support from one’s partner and parental support [ 12 ]. Societal determinants include social norms, religion [ 9 , 13 ], the stigma of premarital and extra-marital sex [ 14 ], adolescents’ status, and autonomy within society [ 12 ]. At the organizational level, the existence of sex education [ 10 , 14 ], the health care system, and abortion laws influence the decisions if and where to have an abortion.

Those factors are related to power and (gender) inequalities. They limit young women’s autonomy and make them vulnerable to pressure. Additionally, the situation is exacerbated when there is a lack of clarity and information on abortion status, despite the existence of a progressive law in this regard.

For example, Mozambican law has allowed abortion if the woman’s health is at risk since the 1980s [ 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 ]. In 2014, a new abortion law was established that broadened the scope of the original law: women are now also allowed to terminate their pregnancy: (1) if they requested it and it is performed during the first 12 weeks; (2) in the first 16 weeks if it was the result of rape or incest, or (3) in the first 24 weeks if the mother’s physical or mental health was in danger or in cases of fetus disease or anomaly. Women younger than 16 or psychically incapable of deciding need parental consent [ 19 , 20 ].

Notwithstanding the progressive abortion laws in Mozambique, hospital-based studies report that unsafe abortion remains one of the main causes of maternal death in Mozambique [ 3 ]. However, hospital cases are only a small share of unsafe abortions in the country. Many women undergo an abortion in illegal and unsafe circumstances for a variety of reasons [ 3 ], such as legal restrictions, the fear of stigma [ 21 , 22 , 23 ], and a lack of knowledge of the availability of abortion services [ 3 , 9 , 23 ].

According to the 2011 Mozambican Demographic Health Survey (DHS), at least 4.5% of all adolescents reported having terminated a pregnancy [ 24 ]. Unpublished data from the records of Mozambican Association for Family Development (AMODEFA) which has a clinic that offers sexual and reproductive health services, including safe abortion, indicate that from 2010 to 2016 a total of 70,895 women had an induced abortion in this clinic, of which 43% were aged 15 to 24. Of the 1500 women that had an induced abortion in the AMODEFA clinic in the first three months of 2017, 27.9% were also in this age group [ 25 ]. These data show the high demand for (safe) abortion among young women.

For all this described above, Mozambique is an interesting place to study this decision-making process; given the changing legal framework, women may have to navigate gray areas in terms of legality, safety, and access when seeking abortion, which is stigmatized but necessary for the health, well-being, and social position of many young women.

The objective of this study is to explore the individual, interpersonal and environmental factors behind the abortion decision-making process. This entails both the decision to have an abortion and the decision on how to have the abortion. By examining fourteen stories of young women with an episode of induced abortion, we contribute to the documentation of the circumstances around the abortion decision making, and also to inform the policymakers on complexity of this issue for, which in turn can contribute to improve the strategies designed to reduce the cases of maternal morbidity and mortality in Mozambique.

2. Materials and Methods

This is an exploratory study using in-depth interview to explore factors related to abortion decision-making in a changing context. As research on this topic is limited, we opted for a qualitative research framework that aims to identify factors influencing this decision-making process.

2.1. Location of the Study

The study was conducted in two Mozambican cities, Maputo and Quelimane. These cities were selected because they registered more abortions than other cities in the same region. According to the 2014 data from the Direcção Nacional de Planificação, 629 and 698 women, respectively, were admitted to the hospital due to induced abortion complications in Maputo and Quelimane [ 26 ]. Furthermore, the two differ radically in terms of culture, with Maputo in the South being patrilineal and Quelimane in the Central Region matrilineal, which could influence the abortion decision-making process. The fieldwork took place between July–August 2016 and January–February 2017.

2.2. Data Collection

The data were collected through in-depth interviews, asking participants about their experiences with induced abortion and what motivated them to get an abortion. To approach and recruit participants ( Figure 1 ), we used the information collected during a cross-sectional survey with women in the reproductive age (15–49), These women were selected randomly applying multistage cluster based on household registers. The survey was designed to understand women’s sexual and reproductive health and included filter questions that allowed us to identify participants who had undergone an abortion. The information sheet and informed consent form for this household survey included information about a possible follow-up study.

The process of recruitment of the participants.

Participants who were within the age-range 15–24 years and who reported having had an abortion were contacted by phone. In this contact, the researcher (MF) introduced herself, reminded the participant of the study she took part in, explained the follow-up study and asked whether she was willing to participate in this. If she did, an appointment was made at a convenient location. Before each interview, we explained to each participant why she was invited to the second interview. Participants were also informed of interview procedures, confidentiality and anonymity in the management of the data, and the possibility to withdraw from the interview at any time. In total 14, young women (15–24) agreed to participate: nine in Maputo and five in Quelimane. Six of them were interviewed twice to explore further aspects that remained unclear after the first interview. The interviews were conducted in Portuguese.

To start the interview, the participant was invited to tell her life history from puberty until the moment when the abortion occurred. During the conversation, we used probing questions to elicit more details. Gradually, we added questions related to the abortion and factors that influenced the decision process. The main questions were related to the pregnancy history, abortion decision-making, and help-seeking behaviour. The guideline was adapted from WHO tools [ 27 , 28 ]. Before the implementation of the guideline, it was discussed first with another Mozambican researcher to see how they fell regarding the question. After those questions were revised or removed from the guideline.

2.3. Data Analysis

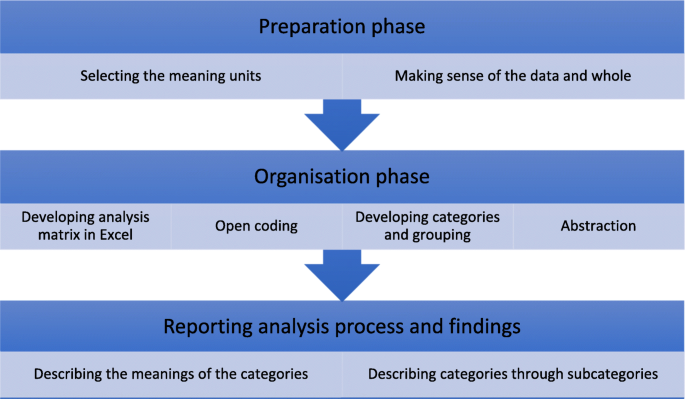

The analysis consisted of three steps: transcription, reading, and codification with NVivo version 11(QSR International Pty Ltd., Doncaster, Australia). After an initial reading, one of the authors (MF) developed a coding tree on factors determining the decision-making. A structured thematic analysis was used to make inferences and elicit key emerging themes from the text-based data [ 29 , 30 ]. The coding tree was based on the ecological model, which is a comprehensive framework that emphasizes the interaction between, and interdependence of factors within and across all levels of a health problem since it considers that the behaviour affects and is affected by multiple levels of influence [ 31 , 32 ].

Next, the codes and the classification were discussed among the researchers (Mónica Frederico, Kristien Michielsen, Carlos Arnaldo and Peter Decat). Finally, the data was interpreted, and conclusions were drawn [ 33 ].

2.4. Ethical Consideration

Before the implementation of this research, we obtained ethical approval from the Institutional Committee of the Faculty of Medicine and Nacional Bioethical Committee for Health (IRB00002657). We also asked for the institutional approval of the Minister of Health and authorities at the provincial and community levels. The participants gave their informed consent after the objectives and interview procedures had been explained to them. The participants were informed that they might be contacted and invited, within six months, to participate in another interview.

2.5. Concepts

The providers are the people who carried out the abortion procedure. These may be categorized into skilled and unskilled providers: the former refers to a professional (i.e., nurse or doctor) offering abortion services to a client, while the latter is someone without any medical training. Another concept that requires further explanation is the legal procedure. This corresponds to a set of steps to be followed to comply with the law [ 19 , 20 ]. Specifically, this means that a committee should authorize the induced abortion and an identification document should be available, as well as an informed consent form from the pregnant woman. If the woman is a minor, consent is given by her legal guardian. An ultrasound exam is required to determine the gestational age.

3.1. Characteristics of the Participants

The characteristics of the interviewees are summarized in Table 1 . The 14 participants were aged 17 to 24 years. Eight had completed secondary school, four had achieved the second level of primary school, and two were university students. Almost all (13) were Christian. Five participants were studying, eight were unemployed, and one was working. The median age of their first sexual intercourse was 15.5 years. Participants reported living with one or both parents (12), with their uncle (1) or alone (1). They lived in suburban areas of Maputo and Quelimane, which are slums with poor living conditions. In these areas, most households earn their income through small businesses that also involve child labour (e.g., selling food or drinks).

Socio-demographic characteristics and abortion procedure.

| Characteristics of Respondents | Categories | Median/Number |

|---|---|---|

| Age (median, range) | - | 21 (min: 17; max: 24) |

| Age at sexual activity onset (median, range) | - | 15.5 (min: 14; max: 18) |

| Education attainment (number) | Primary school | 4 |

| Secondary School | 8 | |

| University | 2 | |

| Religion (number) | Catholic + Evangelic | 13 |

| Muslim | 1 | |

| Occupation (number) | Studying | 5 |

| Without occupation | 8 | |

| Vendor | 1 | |

| Abortion procedure | ||

| Provider characteristics | Skilled | 12 |

| Unskilled | 2 | |

| Location of abortion | Health facility | 7 |

| Outside of health facility | 7 | |

| Treatment for abortion | Pills | 5 |

| Aspiration/curettage | 8 | |

| Traditional medicine | 1 | |

| Followed legal procedure | Yes | 0 |

| No | 14 |

Among the participants, five reported more than one pregnancy. One interviewee first had a stillbirth and then two abortions. Another woman gave birth to a girl and afterward terminated two pregnancies. Two interviewees reported two pregnancies, the first of which was brought to full term and the second one terminated. One woman first had an abortion and afterward gave birth to a child. In short, 14 interviewees in total reported on the experiences and decision-making of 16 abortions. One participant stated that the pregnancy was the consequence of rape. Of the 16 reported abortions, seven were performed after the new law came into force at the end of 2014, and nine were carried out before this time.

3.2. Abortions Stories

In this study, 12 abortions were done by skilled providers and two by unskilled providers. The unskilled providers were a mother and a husband, respectively. None of the cases, whose abortion was done by a skilled provider, included in this study followed the legal procedure.

In the analysis of the interviews, we studied the personal, interpersonal and environmental factors that influenced six different types of abortion stories, see Table 2 : (1) an abortion was performed because the pregnancy was unwanted; (2) an abortion was carried out although the pregnancy was wanted; (3) the abortion was done by an unskilled provider at home; (4) an abortion was carried out by a skilled provider outside the hospital; (5) a particular abortion procedure (medical or chirurgical) was chosen, and (6) the legal procedure was not followed in the hospital. Factors influencing the choice for a particular technical procedure were also examined.

Summary of induced abortion stories. (We changed the table format, please confirm.)

| Abortion Stories | Personal | Interpersonal | Environmental |

|---|---|---|---|

| Unwanted pregnancy (5 + 1 *) | Unable to be a mother | Lack of support | The result of rape |

| Had a bad past experience | |||

| Has another child | |||

| Wanted to study | |||

| Financial problems | |||

| Felt depressed | |||

| Abortion although pregnancy is wanted (7) | Partner did not recognize the child | ||

| Convinced by sister | |||

| Afraid of being sent away | |||

| Convinced/forced by mother | |||

| Partner did not want the child | |||

| Partner’s behaviour changed | |||

| Partner was married | |||

| Unskilled provider (2) | Carried out by partner Carried out by mother | ||

| Abortion outside hospital (8) | Unaware of legal obligations | Provider told us to go to his home | Abortion services are not available in the local healthcare settings |

| Lack of money | Fear of signing a document | ||

| Abortion at home (2) | Mother said that they would kill me at hospital | ||

| Decided by partner | |||

| Technical procedure | Decided by provider (aspiration, curettage **, pills ***) | ||

| Husband gave traditional medicine (1) | |||

| Why the legal procedure is not followed in the hospital (6) | Provider did not inform us about it | Information about legal procedures was not available |

* The result of rape; ** Seven participants; *** six participants.

3.3. Abortion Following an Unwanted Pregnancy

In the stories about unwanted pregnancies, mostly personal factors were mentioned as reasons, with some interviewees stating that they felt unable to be a mother at the time of the pregnancy: “ (It) was at the time that I was taking pills that I got pregnant, and I induced abortion because I was not prepared (for motherhood). ” (24 years)

Some had had a bad experience in the past: “ Maybe I would be abandoned and it would be the same. (Sigh)... I learned with my first pregnancy. ” (23 years)

Also, the existence of another child was mentioned as a reason to have an abortion: “ I got pregnant when I was 20, and I had a baby. When I became pregnant again, my daughter was a child, and I could not have another child. ” (23 years)

For other participants, studies were the main reason why the pregnancy was not wanted: “ He was informed about it, and he said that I should keep it. However, as I wanted to continue my studies, I told him no, no (I) do not. ” (17 years)

At the interpersonal level, a lack of support from the partner was often mentioned as a reason for not wanting the baby: “ He said that he recognizes the paternity, but it is not to keep that pregnancy. ” (22 years)

Women frequently mentioned environmental circumstances related to their poor socio-economic situation: “ I am staying at Mom's house; it is not okay to still be having babies there.” (23 years)

“ At home, we do not have any resources to take care of this child! ” (20 years)

3.4. Abortion Following a Wanted Pregnancy

In these cases, the decision to abort the pregnancy was not made by the woman herself but imposed by others or by the circumstances.

Some participants reported that their parents/family had decided what had to be done: “ They decided while I was at school. If (it) was my decision I would keep it because I wanted it. ” (18 years).

Other young women indicated the refusal of paternity as a reason to terminate the pregnancy.

“ Because my son’s father did not accept the (second) pregnancy. There was a time, we argued with each other, and we terminated the relationship. Later, we started dating again, and I got pregnant. He said it was not possible. ” (21 years)

“ (he) impregnated me and after that, he dumped me, (smiles)… I went to him, and I said that I was pregnant. He said eee: I do not know, that is not my child. ” (20 years).

Some women told the interviewers that they were convinced by their boyfriend to have an abortion: “ I talked to him, and he said okay we are going to have an abortion and I accepted. ” (22 years)

Others mentioned their partner’s indecision and changing attitude as a reason to get an abortion, even though they did want the baby:

“ I told him I was pregnant. First, he said to keep it. (Next) He was different. Sometimes he was calling me, and other times not. I understood that he did not want me. ” (20 years)

The fear of being excluded from their family due to their pregnancy was another reason reported by participants: “ So I went to talk with my older sister, and she said eee, you must abort because daddy will kick you out of our home. ” (20 years)

“ As I am an orphan, and I live with my uncle, they were going to kick me out. No one would assist me. ” (20 years)

3.5. Location of the Abortion: Home-Based Versus Hospital-Based

Two young women reported having had the abortion at home by an unskilled provider. It seems that these unskilled providers than the women (i.e. family members, partner) made the decisions.

“ It was mammy and my sister (who provided the induced abortion services). My sister knows these things. ” (18 years)

“ He (the father of the child) came to my house and took me back to his house. It was that moment when I aborted. ” (21 years)

Of the 16 abortions, seven were performed through health services, by a skilled provider. For some of them, the choice for a health service was influenced by the fact of knowing someone at the health facility.

“ I went to talk to her (friend), and she said that “I have an aunt who works at the hospital, she can help you. Just take money”. ” (20 years)

“ I Already knew who could induce it (abortion). No, I knew that person. I went to the hospital, and I talked to her, (and) she helped me. ” (22 years)

Other participants went to the health facility, but due to the lack of money to pay for an abortion at the facilities they sought help out of the health facility: “ They charged us money that we did not have. The ladies did not want to negotiate anything. I think they wanted 1200 mt (17.1 euros) if I am not wrong. He had a job, but he (boyfriend) did not have that amount of money. ” (22 years)

Some participants reported that they had an abortion outside regular facilities because the health provider recommended going to his house: “ She (mother) was the one who accompanied me. She is the one who knows the doctor. We went to the central hospital, but he (the doctor) was very busy, and he told us to go to his house. ” (17 years)

Others reported the fear of signing a document as a reason to seek help outside of official channels: “ I heard that to induce abortion at the hospital it is necessary for an adult to sign a consent form. I was afraid because I did not know who could accompany me. Because at that time I only wanted to hide it from others. ” (22 years).

3.6. Abortion Procedure

The women were not able to explain why a particular abortion procedure (i.e., pills or aspiration, curettage) was used. It appears that they were not given the opportunity to choose and that they submitted themselves to the procedure proposed by the provider.

“ The abortion was done here at home. They just went to the pharmacy, bought pills and gave them to me. ” (18 years)

3.7. Legal Procedure

None of those treated at the hospital stated that legal procedures were followed. They also mentioned that they had to pay without receiving any official receipt.

“ First we got there and talked to a servant (a helper of the hospital). The servant asked for money for a refreshment so he could talk to a doctor. After we spoke (with servant), he went to the doctor, and the doctor came, and we arranged everything with him. ” (22 years)

“ We went to the health center, and we talked to those doctors or nurses I mean, they said that they could provide that service. It was 1200 mt (17.1 euros), and they were going to deal with everything. They did not give us the chance to sign a document and follow those procedures. ” (20 years)

4. Discussion

The objective of this study was to describe abortion procedures and to explore factors influencing the abortion decision-making process among young women in Maputo and Quelimane.

The study pointed out determinants at the personal, interpersonal and environmental level. Analysing the results, we were confronted with four recurring factors that negatively impacted on the decision-making process: (1) women’s lack of autonomy to make their own decisions regarding the termination of the pregnancy, (2) their general lack of knowledge, (3) the poor availability of local abortion services, and (4) the overpowering influence of providers on the decisions made.

The first factor involves women’s lack of autonomy. In our study, most women indicate that decisions regarding the termination of a pregnancy are mostly taken by others, sometimes against their will. Parents, family members, partners, and providers decide what should happen. As shown in the literature, this lack of autonomy in abortion decision-making is linked to power and gender inequality [ 34 , 35 , 36 , 37 , 38 ]. On the one hand, power reflects the degree to which individuals or groups can impose their will on others, with or without the consent of those others [ 34 , 37 , 38 ]. In this case, the power of the parent/family is observed when they, directly or indirectly, influence their daughters to induce an abortion, for instance by threatening to kick them out of their home. On the other hand, gender inequality is also a factor. This refers to the power imbalance between men and women and is reflected by cases in which the partner makes the decision to terminate the pregnancy [ 38 ]. Besides this, the contextual environment of male chauvinism in Mozambique also makes it more socially acceptable for men to reject responsibility for a pregnancy [ 34 , 35 , 37 , 39 , 40 ]. Finally, women’s economic dependence makes them more vulnerable, dependent and subordinated. For economic reasons, women, have no other choice but to obey and follow the family or partner’s decisions. Closely linked with women’s lack of autonomy is their lack of knowledge. Interviewees report that they do not know where abortion services are provided. They are not acquainted with the legal procedures and do not know their sexual rights. This lack of knowledge among women contributes to the high prevalence of pregnancy termination outside of health facilities and not in accordance with legal procedures.

Our participants often report that abortion services are absent at a local level, as has also been pointed out by Ngwena [ 41 ]. This is a particular problem in Mozambique. Not all tertiary or quaternary health facilities are authorized to perform abortions. The fact that only some tertiary and quaternary facilities are allowed to do so creates a shortage of abortion centres to cover the demand. In fact, only people with a certain level of education and a sufficiently large social network have access to legal and proper abortion procedures.

Finally, our study shows that providers mostly decide on the location, the methods used and the legality of abortion procedures. Patients are highly dependent on the health providers’ commitment, professionality and accuracy and the selected procedures are not mutually decided by the provider and the patient. Providers often do not refer the client to the reference health facility or do not inform them of the legal procedures, creating a gap between law and practice that stimulates illegal and unsafe procedures. The reasons for this are unclear. It might be due to a lack of knowledge among health providers too, and, perhaps, provider saw here an opportunity to supplement the low salary [ 42 ]. Participants who seek help at the health facility they do so contacting the provider in particular, as indication given by someone.

This corroborates with studies conducted by Ngwena [ 41 , 43 ], Doran et al. [ 44 ], Pickles [ 45 ], Mantshi [ 46 ], and Ngwena [ 47 ], which pointed out the obstacles related to the availability of services and providers’ attitudes towards safe abortion, although the law grants the population this right [ 41 , 43 , 44 , 45 , 46 , 47 ]. As Ngwena [ 41 , 43 ] argues, the liberalization of abortion laws is not always put into practice and abortion rights merely exist on paper. Braam’ study [ 48 ] therefore highlights the necessity of clarifying and informing women and providers of the current legislation and ensuring that abortion services are available in all circumstances described in the law.

Finally, despite cultural differences between Maputo and Quelimane, the result did not suggest differences between two areas studied regarding factors influencing the decision to terminate and how the abortion is done. However, the Figure 1 suggests that there was trend to have more participants from Maputo reporting abortion episode in her life than Quelimane. This difference maybe be because Maputo is much more multicultural and the people of this city have more access to information that gives them the opportunity to learn about matter of reproductive health including abortion, than Quelimane. So, due to this there is trend decrease the taboo relation to abortion in Maputo than in Quelimane.

These abortion stories illustrate the lack of autonomy in decision-making process given the power and gender inequalities between adults and young women, and also between man and women . They also show the lack of knowledge not only on the availability of abortion services at some health facilities, as well as, on the new law on abortion. All these lacks that women have are reinforced by poor availability of abortion services and the fact that the providers we not taking their role to help those women, as it is exposed in the next sections.

This study interviewed young women who had an induced abortion at some point in their lives (15 years up to their age at interview date). As such, it does not provide any information on the factors behind the decisions of those who did not terminate their pregnancy.

The results presented in this paper only reflect the perceptions of the young women who had an induced abortion, not those of their parents or partners. The paper is based on qualitative data that provides insights into factors influencing abortion decision-making. Since the sample included in the study is not representative for the population of young women in Mozambique, the results cannot be generalized.

5. Conclusions

Based on the results of the study, we recommend the following measures to improve the abortion decision-making process among young women:

First, strategies should be implemented to increase women's autonomy in decision-making: The study highlighted that gender and power inequalities obstructed young women to make their decision with autonomy. We reiterate the Chandra-Mouli and colleges [ 49 ] message. There is a need to address gender and power inequalities. Addressing gender inequality, and promotion of more equitable power relations leads to improved health outcomes. The interventions to promote gender-equitable and power relationships, as well as human rights, need to be central to all future programming and policies [ 49 ].

Second, patients and the whole population should be better informed about national abortion laws, the recommended and legal procedures and the location of abortion services, since, despite the decision to terminate pregnancy resulted to the imposition, if they were well informed on that, maybe they could be decide on safe and legal abortion, avoiding double autonomy deprivation. At the same time, providers must be informed about the status of national abortion laws. Additionally, they should be trained in communication skills to promote shared decision-making and patient orientation in abortion counseling.

Third, the number of health facilities providing abortions services should be increased, particularly in remote areas.

Finally, health providers should be trained in communication skills to promote shared decision-making and patient orientation in abortion counseling.

The abortion decision-making by young women is an important topic because it refers the decision made during the transitional period from childhood to adulthood. The decision may have life-long consequences, compromising the individual health, career, psychological well-being, and social acceptance. This paper, on abortion decision-making, calls attention to some attitudes that lead to the illegality of abortion despite it was done at a health facility.

Acknowledgments

Authors gratefully acknowledge the support, contribution, and comments from all those who collaborated direct or indirectly, especially Olivier Degomme, Eunice Remane Jethá, Emilia Gonçalves, Cátia Taibo, Beatriz Chongo, Hélio Maúngue and Rehana Capruchand.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed significantly to the manuscript. Mónica Frederico collected data and developed the first analysis. The themes were intensively discussed with Kristien Michielsen, Carlos Arnaldo and Peter Decat. The subsequent versions of the article were written with the active participation of all authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

- Open access

- Published: 28 June 2021

Impact of abortion law reforms on women’s health services and outcomes: a systematic review protocol

- Foluso Ishola ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-8644-0570 1 ,

- U. Vivian Ukah 1 &

- Arijit Nandi 1

Systematic Reviews volume 10 , Article number: 192 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

21k Accesses

3 Citations

3 Altmetric

Metrics details

A country’s abortion law is a key component in determining the enabling environment for safe abortion. While restrictive abortion laws still prevail in most low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), many countries have reformed their abortion laws, with the majority of them moving away from an absolute ban. However, the implications of these reforms on women’s access to and use of health services, as well as their health outcomes, is uncertain. First, there are methodological challenges to the evaluation of abortion laws, since these changes are not exogenous. Second, extant evaluations may be limited in terms of their generalizability, given variation in reforms across the abortion legality spectrum and differences in levels of implementation and enforcement cross-nationally. This systematic review aims to address this gap. Our aim is to systematically collect, evaluate, and synthesize empirical research evidence concerning the impact of abortion law reforms on women’s health services and outcomes in LMICs.

We will conduct a systematic review of the peer-reviewed literature on changes in abortion laws and women’s health services and outcomes in LMICs. We will search Medline, Embase, CINAHL, and Web of Science databases, as well as grey literature and reference lists of included studies for further relevant literature. As our goal is to draw inference on the impact of abortion law reforms, we will include quasi-experimental studies examining the impact of change in abortion laws on at least one of our outcomes of interest. We will assess the methodological quality of studies using the quasi-experimental study designs series checklist. Due to anticipated heterogeneity in policy changes, outcomes, and study designs, we will synthesize results through a narrative description.

This review will systematically appraise and synthesize the research evidence on the impact of abortion law reforms on women’s health services and outcomes in LMICs. We will examine the effect of legislative reforms and investigate the conditions that might contribute to heterogeneous effects, including whether specific groups of women are differentially affected by abortion law reforms. We will discuss gaps and future directions for research. Findings from this review could provide evidence on emerging strategies to influence policy reforms, implement abortion services and scale up accessibility.

Systematic review registration

PROSPERO CRD42019126927

Peer Review reports

An estimated 25·1 million unsafe abortions occur each year, with 97% of these in developing countries [ 1 , 2 , 3 ]. Despite its frequency, unsafe abortion remains a major global public health challenge [ 4 , 5 ]. According to the World health Organization (WHO), nearly 8% of maternal deaths were attributed to unsafe abortion, with the majority of these occurring in developing countries [ 5 , 6 ]. Approximately 7 million women are admitted to hospitals every year due to complications from unsafe abortion such as hemorrhage, infections, septic shock, uterine and intestinal perforation, and peritonitis [ 7 , 8 , 9 ]. These often result in long-term effects such as infertility and chronic reproductive tract infections. The annual cost of treating major complications from unsafe abortion is estimated at US$ 232 million each year in developing countries [ 10 , 11 ]. The negative consequences on children’s health, well-being, and development have also been documented. Unsafe abortion increases risk of poor birth outcomes, neonatal and infant mortality [ 12 , 13 ]. Additionally, women who lack access to safe and legal abortion are often forced to continue with unwanted pregnancies, and may not seek prenatal care [ 14 ], which might increase risks of child morbidity and mortality.

Access to safe abortion services is often limited due to a wide range of barriers. Collectively, these barriers contribute to the staggering number of deaths and disabilities seen annually as a result of unsafe abortion, which are disproportionately felt in developing countries [ 15 , 16 , 17 ]. A recent systematic review on the barriers to abortion access in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) implicated the following factors: restrictive abortion laws, lack of knowledge about abortion law or locations that provide abortion, high cost of services, judgmental provider attitudes, scarcity of facilities and medical equipment, poor training and shortage of staff, stigma on social and religious grounds, and lack of decision making power [ 17 ].

An important factor regulating access to abortion is abortion law [ 17 , 18 , 19 ]. Although abortion is a medical procedure, its legal status in many countries has been incorporated in penal codes which specify grounds in which abortion is permitted. These include prohibition in all circumstances, to save the woman’s life, to preserve the woman’s health, in cases of rape, incest, fetal impairment, for economic or social reasons, and on request with no requirement for justification [ 18 , 19 , 20 ].

Although abortion laws in different countries are usually compared based on the grounds under which legal abortions are allowed, these comparisons rarely take into account components of the legal framework that may have strongly restrictive implications, such as regulation of facilities that are authorized to provide abortions, mandatory waiting periods, reporting requirements in cases of rape, limited choice in terms of the method of abortion, and requirements for third-party authorizations [ 19 , 21 , 22 ]. For example, the Zambian Termination of Pregnancy Act permits abortion on socio-economic grounds. It is considered liberal, as it permits legal abortions for more indications than most countries in Sub-Saharan Africa; however, abortions must only be provided in registered hospitals, and three medical doctors—one of whom must be a specialist—must provide signatures to allow the procedure to take place [ 22 ]. Given the critical shortage of doctors in Zambia [ 23 ], this is in fact a major restriction that is only captured by a thorough analysis of the conditions under which abortion services are provided.

Additionally, abortion laws may exist outside the penal codes in some countries, where they are supplemented by health legislation and regulations such as public health statutes, reproductive health acts, court decisions, medical ethic codes, practice guidelines, and general health acts [ 18 , 19 , 24 ]. The diversity of regulatory documents may lead to conflicting directives about the grounds under which abortion is lawful [ 19 ]. For example, in Kenya and Uganda, standards and guidelines on the reduction of morbidity and mortality due to unsafe abortion supported by the constitution was contradictory to the penal code, leaving room for an ambiguous interpretation of the legal environment [ 25 ].

Regulations restricting the range of abortion methods from which women can choose, including medication abortion in particular, may also affect abortion access [ 26 , 27 ]. A literature review contextualizing medication abortion in seven African countries reported that incidence of medication abortion is low despite being a safe, effective, and low-cost abortion method, likely due to legal restrictions on access to the medications [ 27 ].

Over the past two decades, many LMICs have reformed their abortion laws [ 3 , 28 ]. Most have expanded the grounds on which abortion may be performed legally, while very few have restricted access. Countries like Uruguay, South Africa, and Portugal have amended their laws to allow abortion on request in the first trimester of pregnancy [ 29 , 30 ]. Conversely, in Nicaragua, a law to ban all abortion without any exception was introduced in 2006 [ 31 ].

Progressive reforms are expected to lead to improvements in women’s access to safe abortion and health outcomes, including reductions in the death and disabilities that accompany unsafe abortion, and reductions in stigma over the longer term [ 17 , 29 , 32 ]. However, abortion law reforms may yield different outcomes even in countries that experience similar reforms, as the legislative processes that are associated with changing abortion laws take place in highly distinct political, economic, religious, and social contexts [ 28 , 33 ]. This variation may contribute to abortion law reforms having different effects with respect to the health services and outcomes that they are hypothesized to influence [ 17 , 29 ].

Extant empirical literature has examined changes in abortion-related morbidity and mortality, contraceptive usage, fertility, and other health-related outcomes following reforms to abortion laws [ 34 , 35 , 36 , 37 ]. For example, a study in Mexico reported that a policy that decriminalized and subsidized early-term elective abortion led to substantial reductions in maternal morbidity and that this was particularly strong among vulnerable populations such as young and socioeconomically disadvantaged women [ 38 ].

To the best of our knowledge, however, the growing literature on the impact of abortion law reforms on women’s health services and outcomes has not been systematically reviewed. A study by Benson et al. evaluated evidence on the impact of abortion policy reforms on maternal death in three countries, Romania, South Africa, and Bangladesh, where reforms were immediately followed by strategies to implement abortion services, scale up accessibility, and establish complementary reproductive and maternal health services [ 39 ]. The three countries highlighted in this paper provided unique insights into implementation and practical application following law reforms, in spite of limited resources. However, the review focused only on a selection of countries that have enacted similar reforms and it is unclear if its conclusions are more widely generalizable.

Accordingly, the primary objective of this review is to summarize studies that have estimated the causal effect of a change in abortion law on women’s health services and outcomes. Additionally, we aim to examine heterogeneity in the impacts of abortion reforms, including variation across specific population sub-groups and contexts (e.g., due to variations in the intensity of enforcement and service delivery). Through this review, we aim to offer a higher-level view of the impact of abortion law reforms in LMICs, beyond what can be gained from any individual study, and to thereby highlight patterns in the evidence across studies, gaps in current research, and to identify promising programs and strategies that could be adapted and applied more broadly to increase access to safe abortion services.

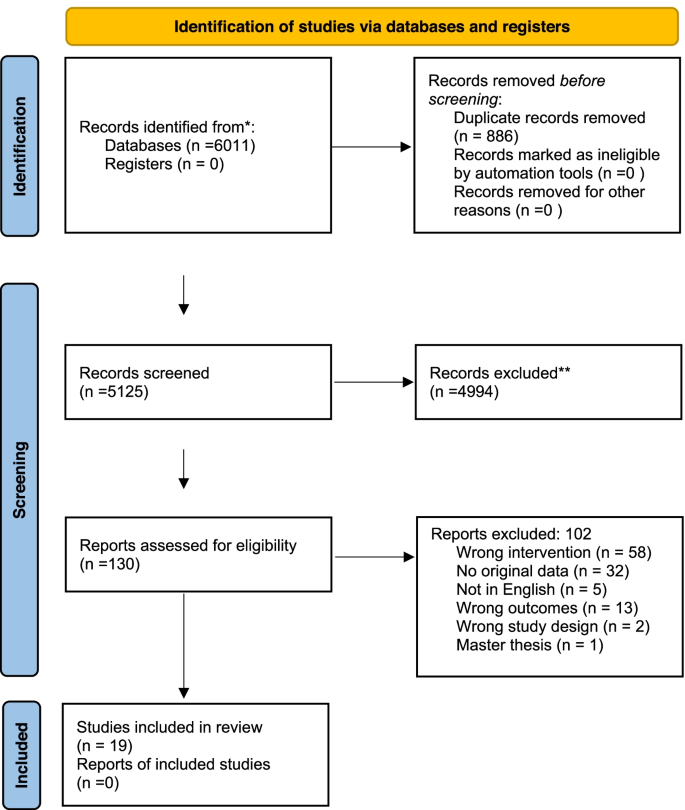

The review protocol has been reported using Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic review and Meta-Analysis Protocols (PRISMA-P) guidelines [ 40 ] (Additional file 1 ). It was registered in the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) database CRD42019126927.

Eligibility criteria

Types of studies.

This review will consider quasi-experimental studies which aim to estimate the causal effect of a change in a specific law or reform and an outcome, but in which participants (in this case jurisdictions, whether countries, states/provinces, or smaller units) are not randomly assigned to treatment conditions [ 41 ]. Eligible designs include the following:

Pretest-posttest designs where the outcome is compared before and after the reform, as well as nonequivalent groups designs, such as pretest-posttest design that includes a comparison group, also known as a controlled before and after (CBA) designs.

Interrupted time series (ITS) designs where the trend of an outcome after an abortion law reform is compared to a counterfactual (i.e., trends in the outcome in the post-intervention period had the jurisdiction not enacted the reform) based on the pre-intervention trends and/or a control group [ 42 , 43 ].

Differences-in-differences (DD) designs, which compare the before vs. after change in an outcome in jurisdictions that experienced an abortion law reform to the corresponding change in the places that did not experience such a change, under the assumption of parallel trends [ 44 , 45 ].

Synthetic controls (SC) approaches, which use a weighted combination of control units that did not experience the intervention, selected to match the treated unit in its pre-intervention outcome trend, to proxy the counterfactual scenario [ 46 , 47 ].

Regression discontinuity (RD) designs, which in the case of eligibility for abortion services being determined by the value of a continuous random variable, such as age or income, would compare the distributions of post-intervention outcomes for those just above and below the threshold [ 48 ].

There is heterogeneity in the terminology and definitions used to describe quasi-experimental designs, but we will do our best to categorize studies into the above groups based on their designs, identification strategies, and assumptions.

Our focus is on quasi-experimental research because we are interested in studies evaluating the effect of population-level interventions (i.e., abortion law reform) with a design that permits inference regarding the causal effect of abortion legislation, which is not possible from other types of observational designs such as cross-sectional studies, cohort studies or case-control studies that lack an identification strategy for addressing sources of unmeasured confounding (e.g., secular trends in outcomes). We are not excluding randomized studies such as randomized controlled trials, cluster randomized trials, or stepped-wedge cluster-randomized trials; however, we do not expect to identify any relevant randomized studies given that abortion policy is unlikely to be randomly assigned. Since our objective is to provide a summary of empirical studies reporting primary research, reviews/meta-analyses, qualitative studies, editorials, letters, book reviews, correspondence, and case reports/studies will also be excluded.

Our population of interest includes women of reproductive age (15–49 years) residing in LMICs, as the policy exposure of interest applies primarily to women who have a demand for sexual and reproductive health services including abortion.

Intervention

The intervention in this study refers to a change in abortion law or policy, either from a restrictive policy to a non-restrictive or less restrictive one, or vice versa. This can, for example, include a change from abortion prohibition in all circumstances to abortion permissible in other circumstances, such as to save the woman’s life, to preserve the woman’s health, in cases of rape, incest, fetal impairment, for economic or social reasons, or on request with no requirement for justification. It can also include the abolition of existing abortion policies or the introduction of new policies including those occurring outside the penal code, which also have legal standing, such as:

National constitutions;

Supreme court decisions, as well as higher court decisions;

Customary or religious law, such as interpretations of Muslim law;

Medical ethical codes; and

Regulatory standards and guidelines governing the provision of abortion.

We will also consider national and sub-national reforms, although we anticipate that most reforms will operate at the national level.

The comparison group represents the counterfactual scenario, specifically the level and/or trend of a particular post-intervention outcome in the treated jurisdiction that experienced an abortion law reform had it, counter to the fact, not experienced this specific intervention. Comparison groups will vary depending on the type of quasi-experimental design. These may include outcome trends after abortion reform in the same country, as in the case of an interrupted time series design without a control group, or corresponding trends in countries that did not experience a change in abortion law, as in the case of the difference-in-differences design.

Outcome measures

Primary outcomes.

Access to abortion services: There is no consensus on how to measure access but we will use the following indicators, based on the relevant literature [ 49 ]: [ 1 ] the availability of trained staff to provide care, [ 2 ] facilities are geographically accessible such as distance to providers, [ 3 ] essential equipment, supplies and medications, [ 4 ] services provided regardless of woman’s ability to pay, [ 5 ] all aspects of abortion care are explained to women, [ 6 ] whether staff offer respectful care, [ 7 ] if staff work to ensure privacy, [ 8 ] if high-quality, supportive counseling is provided, [ 9 ] if services are offered in a timely manner, and [ 10 ] if women have the opportunity to express concerns, ask questions, and receive answers.

Use of abortion services refers to induced pregnancy termination, including medication abortion and number of women treated for abortion-related complications.

Secondary outcomes

Current use of any method of contraception refers to women of reproductive age currently using any method contraceptive method.

Future use of contraception refers to women of reproductive age who are not currently using contraception but intend to do so in the future.

Demand for family planning refers to women of reproductive age who are currently using, or whose sexual partner is currently using, at least one contraceptive method.

Unmet need for family planning refers to women of reproductive age who want to stop or delay childbearing but are not using any method of contraception.

Fertility rate refers to the average number of children born to women of childbearing age.

Neonatal morbidity and mortality refer to disability or death of newborn babies within the first 28 days of life.

Maternal morbidity and mortality refer to disability or death due to complications from pregnancy or childbirth.

There will be no language, date, or year restrictions on studies included in this systematic review.

Studies have to be conducted in a low- and middle-income country. We will use the country classification specified in the World Bank Data Catalogue to identify LMICs (Additional file 2 ).

Search methods

We will perform searches for eligible peer-reviewed studies in the following electronic databases.

Ovid MEDLINE(R) (from 1946 to present)

Embase Classic+Embase on OvidSP (from 1947 to present)

CINAHL (1973 to present); and

Web of Science (1900 to present)

The reference list of included studies will be hand searched for additional potentially relevant citations. Additionally, a grey literature search for reports or working papers will be done with the help of Google and Social Science Research Network (SSRN).

Search strategy

A search strategy, based on the eligibility criteria and combining subject indexing terms (i.e., MeSH) and free-text search terms in the title and abstract fields, will be developed for each electronic database. The search strategy will combine terms related to the interventions of interest (i.e., abortion law/policy), etiology (i.e., impact/effect), and context (i.e., LMICs) and will be developed with the help of a subject matter librarian. We opted not to specify outcomes in the search strategy in order to maximize the sensitivity of our search. See Additional file 3 for a draft of our search strategy.

Data collection and analysis

Data management.

Search results from all databases will be imported into Endnote reference manager software (Version X9, Clarivate Analytics) where duplicate records will be identified and excluded using a systematic, rigorous, and reproducible method that utilizes a sequential combination of fields including author, year, title, journal, and pages. Rayyan systematic review software will be used to manage records throughout the review [ 50 ].

Selection process

Two review authors will screen titles and abstracts and apply the eligibility criteria to select studies for full-text review. Reference lists of any relevant articles identified will be screened to ensure no primary research studies are missed. Studies in a language different from English will be translated by collaborators who are fluent in the particular language. If no such expertise is identified, we will use Google Translate [ 51 ]. Full text versions of potentially relevant articles will be retrieved and assessed for inclusion based on study eligibility criteria. Discrepancies will be resolved by consensus or will involve a third reviewer as an arbitrator. The selection of studies, as well as reasons for exclusions of potentially eligible studies, will be described using a PRISMA flow chart.

Data extraction

Data extraction will be independently undertaken by two authors. At the conclusion of data extraction, these two authors will meet with the third author to resolve any discrepancies. A piloted standardized extraction form will be used to extract the following information: authors, date of publication, country of study, aim of study, policy reform year, type of policy reform, data source (surveys, medical records), years compared (before and after the reform), comparators (over time or between groups), participant characteristics (age, socioeconomic status), primary and secondary outcomes, evaluation design, methods used for statistical analysis (regression), estimates reported (means, rates, proportion), information to assess risk of bias (sensitivity analyses), sources of funding, and any potential conflicts of interest.

Risk of bias and quality assessment

Two independent reviewers with content and methodological expertise in methods for policy evaluation will assess the methodological quality of included studies using the quasi-experimental study designs series risk of bias checklist [ 52 ]. This checklist provides a list of criteria for grading the quality of quasi-experimental studies that relate directly to the intrinsic strength of the studies in inferring causality. These include [ 1 ] relevant comparison, [ 2 ] number of times outcome assessments were available, [ 3 ] intervention effect estimated by changes over time for the same or different groups, [ 4 ] control of confounding, [ 5 ] how groups of individuals or clusters were formed (time or location differences), and [ 6 ] assessment of outcome variables. Each of the following domains will be assigned a “yes,” “no,” or “possibly” bias classification. Any discrepancies will be resolved by consensus or a third reviewer with expertise in review methodology if required.

Confidence in cumulative evidence

The strength of the body of evidence will be assessed using the Grades of Recommendation, Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) system [ 53 ].

Data synthesis

We anticipate that risk of bias and heterogeneity in the studies included may preclude the use of meta-analyses to describe pooled effects. This may necessitate the presentation of our main findings through a narrative description. We will synthesize the findings from the included articles according to the following key headings:

Information on the differential aspects of the abortion policy reforms.

Information on the types of study design used to assess the impact of policy reforms.

Information on main effects of abortion law reforms on primary and secondary outcomes of interest.

Information on heterogeneity in the results that might be due to differences in study designs, individual-level characteristics, and contextual factors.

Potential meta-analysis

If outcomes are reported consistently across studies, we will construct forest plots and synthesize effect estimates using meta-analysis. Statistical heterogeneity will be assessed using the I 2 test where I 2 values over 50% indicate moderate to high heterogeneity [ 54 ]. If studies are sufficiently homogenous, we will use fixed effects. However, if there is evidence of heterogeneity, a random effects model will be adopted. Summary measures, including risk ratios or differences or prevalence ratios or differences will be calculated, along with 95% confidence intervals (CI).

Analysis of subgroups

If there are sufficient numbers of included studies, we will perform sub-group analyses according to type of policy reform, geographical location and type of participant characteristics such as age groups, socioeconomic status, urban/rural status, education, or marital status to examine the evidence for heterogeneous effects of abortion laws.

Sensitivity analysis

Sensitivity analyses will be conducted if there are major differences in quality of the included articles to explore the influence of risk of bias on effect estimates.

Meta-biases

If available, studies will be compared to protocols and registers to identify potential reporting bias within studies. If appropriate and there are a sufficient number of studies included, funnel plots will be generated to determine potential publication bias.

This systematic review will synthesize current evidence on the impact of abortion law reforms on women’s health. It aims to identify which legislative reforms are effective, for which population sub-groups, and under which conditions.

Potential limitations may include the low quality of included studies as a result of suboptimal study design, invalid assumptions, lack of sensitivity analysis, imprecision of estimates, variability in results, missing data, and poor outcome measurements. Our review may also include a limited number of articles because we opted to focus on evidence from quasi-experimental study design due to the causal nature of the research question under review. Nonetheless, we will synthesize the literature, provide a critical evaluation of the quality of the evidence and discuss the potential effects of any limitations to our overall conclusions. Protocol amendments will be recorded and dated using the registration for this review on PROSPERO. We will also describe any amendments in our final manuscript.

Synthesizing available evidence on the impact of abortion law reforms represents an important step towards building our knowledge base regarding how abortion law reforms affect women’s health services and health outcomes; we will provide evidence on emerging strategies to influence policy reforms, implement abortion services, and scale up accessibility. This review will be of interest to service providers, policy makers and researchers seeking to improve women’s access to safe abortion around the world.

Abbreviations

Cumulative index to nursing and allied health literature

Excerpta medica database

Low- and middle-income countries

Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols

International prospective register of systematic reviews

Ganatra B, Gerdts C, Rossier C, Johnson BR, Tuncalp O, Assifi A, et al. Global, regional, and subregional classification of abortions by safety, 2010-14: estimates from a Bayesian hierarchical model. Lancet. 2017;390(10110):2372–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31794-4 .

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Guttmacher Institute. Induced Abortion Worldwide; Global Incidence and Trends 2018. https://www.guttmacher.org/fact-sheet/induced-abortion-worldwide . Accessed 15 Dec 2019.

Singh S, Remez L, Sedgh G, Kwok L, Onda T. Abortion worldwide 2017: uneven progress and unequal access. NewYork: Guttmacher Institute; 2018.

Book Google Scholar

Fusco CLB. Unsafe abortion: a serious public health issue in a poverty stricken population. Reprod Clim. 2013;2(8):2–9.

Google Scholar

Rehnstrom Loi U, Gemzell-Danielsson K, Faxelid E, Klingberg-Allvin M. Health care providers’ perceptions of and attitudes towards induced abortions in sub-Saharan Africa and Southeast Asia: a systematic literature review of qualitative and quantitative data. BMC Public Health. 2015;15(1):139. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-015-1502-2 .

Say L, Chou D, Gemmill A, Tuncalp O, Moller AB, Daniels J, et al. Global causes of maternal death: a WHO systematic analysis. Lancet Glob Health. 2014;2(6):E323–E33. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(14)70227-X .

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Benson J, Nicholson LA, Gaffikin L, Kinoti SN. Complications of unsafe abortion in sub-Saharan Africa: a review. Health Policy Plan. 1996;11(2):117–31. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapol/11.2.117 .

Abiodun OM, Balogun OR, Adeleke NA, Farinloye EO. Complications of unsafe abortion in South West Nigeria: a review of 96 cases. Afr J Med Med Sci. 2013;42(1):111–5.

CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Singh S, Maddow-Zimet I. Facility-based treatment for medical complications resulting from unsafe pregnancy termination in the developing world, 2012: a review of evidence from 26 countries. BJOG. 2016;123(9):1489–98. https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-0528.13552 .

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Vlassoff M, Walker D, Shearer J, Newlands D, Singh S. Estimates of health care system costs of unsafe abortion in Africa and Latin America. Int Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2009;35(3):114–21. https://doi.org/10.1363/3511409 .

Singh S, Darroch JE. Adding it up: costs and benefits of contraceptive services. Estimates for 2012. New York: Guttmacher Institute and United Nations Population Fund; 2012.

Auger N, Bilodeau-Bertrand M, Sauve R. Abortion and infant mortality on the first day of life. Neonatology. 2016;109(2):147–53. https://doi.org/10.1159/000442279 .

Krieger N, Gruskin S, Singh N, Kiang MV, Chen JT, Waterman PD, et al. Reproductive justice & preventable deaths: state funding, family planning, abortion, and infant mortality, US 1980-2010. SSM Popul Health. 2016;2:277–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmph.2016.03.007 .

Banaem LM, Majlessi F. A comparative study of low 5-minute Apgar scores (< 8) in newborns of wanted versus unwanted pregnancies in southern Tehran, Iran (2006-2007). J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2008;21(12):898–901. https://doi.org/10.1080/14767050802372390 .

Bhandari A. Barriers in access to safe abortion services: perspectives of potential clients from a hilly district of Nepal. Trop Med Int Health. 2007;12:87.

Seid A, Yeneneh H, Sende B, Belete S, Eshete H, Fantahun M, et al. Barriers to access safe abortion services in East Shoa and Arsi Zones of Oromia Regional State, Ethiopia. J Health Dev. 2015;29(1):13–21.

Arroyave FAB, Moreno PA. A systematic bibliographical review: barriers and facilitators for access to legal abortion in low and middle income countries. Open J Prev Med. 2018;8(5):147–68. https://doi.org/10.4236/ojpm.2018.85015 .

Article Google Scholar

Boland R, Katzive L. Developments in laws on induced abortion: 1998-2007. Int Fam Plan Perspect. 2008;34(3):110–20. https://doi.org/10.1363/3411008 .

Lavelanet AF, Schlitt S, Johnson BR Jr, Ganatra B. Global Abortion Policies Database: a descriptive analysis of the legal categories of lawful abortion. BMC Int Health Hum Rights. 2018;18(1):44. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12914-018-0183-1 .

United Nations Population Division. Abortion policies: A global review. Major dimensions of abortion policies. 2002 [Available from: https://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/publications/abortion/abortion-policies-2002.asp .

Johnson BR, Lavelanet AF, Schlitt S. Global abortion policies database: a new approach to strengthening knowledge on laws, policies, and human rights standards. Bmc Int Health Hum Rights. 2018;18(1):35. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12914-018-0174-2 .

Haaland MES, Haukanes H, Zulu JM, Moland KM, Michelo C, Munakampe MN, et al. Shaping the abortion policy - competing discourses on the Zambian termination of pregnancy act. Int J Equity Health. 2019;18(1):20. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-018-0908-8 .

Schatz JJ. Zambia’s health-worker crisis. Lancet. 2008;371(9613):638–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60287-1 .

Erdman JN, Johnson BR. Access to knowledge and the Global Abortion Policies Database. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2018;142(1):120–4. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijgo.12509 .

Cleeve A, Oguttu M, Ganatra B, Atuhairwe S, Larsson EC, Makenzius M, et al. Time to act-comprehensive abortion care in east Africa. Lancet Glob Health. 2016;4(9):E601–E2. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(16)30136-X .

Berer M, Hoggart L. Medical abortion pills have the potential to change everything about abortion. Contraception. 2018;97(2):79–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.contraception.2017.12.006 .

Moseson H, Shaw J, Chandrasekaran S, Kimani E, Maina J, Malisau P, et al. Contextualizing medication abortion in seven African nations: A literature review. Health Care Women Int. 2019;40(7-9):950–80. https://doi.org/10.1080/07399332.2019.1608207 .

Blystad A, Moland KM. Comparative cases of abortion laws and access to safe abortion services in sub-Saharan Africa. Trop Med Int Health. 2017;22:351.

Berer M. Abortion law and policy around the world: in search of decriminalization. Health Hum Rights. 2017;19(1):13–27.

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Johnson BR, Mishra V, Lavelanet AF, Khosla R, Ganatra B. A global database of abortion laws, policies, health standards and guidelines. B World Health Organ. 2017;95(7):542–4. https://doi.org/10.2471/BLT.17.197442 .

Replogle J. Nicaragua tightens up abortion laws. Lancet. 2007;369(9555):15–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60011-7 .

Keogh LA, Newton D, Bayly C, McNamee K, Hardiman A, Webster A, et al. Intended and unintended consequences of abortion law reform: perspectives of abortion experts in Victoria, Australia. J Fam Plann Reprod Health Care. 2017;43(1):18–24. https://doi.org/10.1136/jfprhc-2016-101541 .

Levels M, Sluiter R, Need A. A review of abortion laws in Western-European countries. A cross-national comparison of legal developments between 1960 and 2010. Health Policy. 2014;118(1):95–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthpol.2014.06.008 .

Serbanescu F, Morris L, Stupp P, Stanescu A. The impact of recent policy changes on fertility, abortion, and contraceptive use in Romania. Stud Fam Plann. 1995;26(2):76–87. https://doi.org/10.2307/2137933 .

Henderson JT, Puri M, Blum M, Harper CC, Rana A, Gurung G, et al. Effects of Abortion Legalization in Nepal, 2001-2010. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(5):e64775. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0064775 .

Goncalves-Pinho M, Santos JV, Costa A, Costa-Pereira A, Freitas A. The impact of a liberalisation law on legally induced abortion hospitalisations. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2016;203:142–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejogrb.2016.05.037 .

Latt SM, Milner A, Kavanagh A. Abortion laws reform may reduce maternal mortality: an ecological study in 162 countries. BMC Women’s Health. 2019;19(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-018-0705-y .

Clarke D, Muhlrad H. Abortion laws and women’s health. IZA discussion papers 11890. Bonn: IZA Institute of Labor Economics; 2018.

Benson J, Andersen K, Samandari G. Reductions in abortion-related mortality following policy reform: evidence from Romania, South Africa and Bangladesh. Reprod Health. 2011;8(39). https://doi.org/10.1186/1742-4755-8-39 .

Shamseer L, Moher D, Clarke M, Ghersi D, Liberati A, Petticrew M, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015: elaboration and explanation. Bmj-Brit Med J. 2015;349.

William R. Shadish, Thomas D. Cook, Donald T. Campbell. Experimental and quasi-experimental designs for generalized causal inference. Boston, New York; 2002.

Bernal JL, Cummins S, Gasparrini A. Interrupted time series regression for the evaluation of public health interventions: a tutorial. Int J Epidemiol. 2017;46(1):348–55. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyw098 .

Bernal JL, Cummins S, Gasparrini A. The use of controls in interrupted time series studies of public health interventions. Int J Epidemiol. 2018;47(6):2082–93. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyy135 .

Meyer BD. Natural and quasi-experiments in economics. J Bus Econ Stat. 1995;13(2):151–61.

Strumpf EC, Harper S, Kaufman JS. Fixed effects and difference in differences. In: Methods in Social Epidemiology ed. San Francisco CA: Jossey-Bass; 2017.

Abadie A, Diamond A, Hainmueller J. Synthetic control methods for comparative case studies: estimating the effect of California’s Tobacco Control Program. J Am Stat Assoc. 2010;105(490):493–505. https://doi.org/10.1198/jasa.2009.ap08746 .

Article CAS Google Scholar

Abadie A, Diamond A, Hainmueller J. Comparative politics and the synthetic control method. Am J Polit Sci. 2015;59(2):495–510. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajps.12116 .

Moscoe E, Bor J, Barnighausen T. Regression discontinuity designs are underutilized in medicine, epidemiology, and public health: a review of current and best practice. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 2015;68(2):132–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2014.06.021 .

Dennis A, Blanchard K, Bessenaar T. Identifying indicators for quality abortion care: a systematic literature review. J Fam Plan Reprod H. 2017;43(1):7–15. https://doi.org/10.1136/jfprhc-2015-101427 .

Ouzzani M, Hammady H, Fedorowicz Z, Elmagarmid A. Rayyan-a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst Rev. 2016;5(1):210. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-016-0384-4 .

Jackson JL, Kuriyama A, Anton A, Choi A, Fournier JP, Geier AK, et al. The accuracy of Google Translate for abstracting data from non-English-language trials for systematic reviews. Ann Intern Med. 2019.

Reeves BC, Wells GA, Waddington H. Quasi-experimental study designs series-paper 5: a checklist for classifying studies evaluating the effects on health interventions-a taxonomy without labels. J Clin Epidemiol. 2017;89:30–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2017.02.016 .

Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Vist GE, Kunz R, Falck-Ytter Y, Alonso-Coello P, et al. GRADE: an emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ. 2008;336(7650):924–6. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.39489.470347.AD .

Higgins JP, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med. 2002;21(11):1539–58. https://doi.org/10.1002/sim.1186 .

Download references

Acknowledgements

We thank Genevieve Gore, Liaison Librarian at McGill University, for her assistance with refining the research question, keywords, and Mesh terms for the preliminary search strategy.

The authors acknowledge funding from the Fonds de recherche du Quebec – Santé (FRQS) PhD doctoral awards and Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) Operating Grant, “Examining the impact of social policies on health equity” (ROH-115209).

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Epidemiology, Biostatistics and Occupational Health, Faculty of Medicine, McGill University, Purvis Hall 1020 Pine Avenue West, Montreal, Quebec, H3A 1A2, Canada

Foluso Ishola, U. Vivian Ukah & Arijit Nandi

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

FI and AN conceived and designed the protocol. FI drafted the manuscript. FI, UVU, and AN revised the manuscript and approved its final version.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Foluso Ishola .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

Not applicable

Consent for publication

Competing interests.

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1:.

PRISMA-P 2015 Checklist. This checklist has been adapted for use with systematic review protocol submissions to BioMed Central journals from Table 3 in Moher D et al: Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Systematic Reviews 2015 4:1

Additional File 2:.

LMICs according to World Bank Data Catalogue. Country classification specified in the World Bank Data Catalogue to identify low- and middle-income countries

Additional File 3: Table 1

. Search strategy in Embase. Detailed search terms and filters applied to generate our search in Embase

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Ishola, F., Ukah, U.V. & Nandi, A. Impact of abortion law reforms on women’s health services and outcomes: a systematic review protocol. Syst Rev 10 , 192 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-021-01739-w

Download citation

Received : 02 January 2020

Accepted : 08 June 2021

Published : 28 June 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-021-01739-w

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Abortion law/policies; Impact

- Unsafe abortion

- Contraception

Systematic Reviews

ISSN: 2046-4053

- Submission enquiries: Access here and click Contact Us

- General enquiries: [email protected]

- Open access

- Published: 03 October 2018

Decision-making preceding induced abortion: a qualitative study of women’s experiences in Kisumu, Kenya

- Ulrika Rehnström Loi ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-3455-8606 1 ,

- Matilda Lindgren 1 ,

- Elisabeth Faxelid 1 ,

- Monica Oguttu 2 , 3 &

- Marie Klingberg-Allvin 4 , 5

Reproductive Health volume 15 , Article number: 166 ( 2018 ) Cite this article

37k Accesses

41 Citations

1 Altmetric

Metrics details

Unwanted pregnancies and unsafe abortions are prevalent in regions where women and adolescent girls have unmet contraceptive needs. Globally, about 25 million unsafe abortions take place every year. In countries with restrictive abortion laws, safe abortion care is not always accessible. In Kenya, the high unwanted pregnancy rate resulting in unsafe abortions is a serious public health issue. Gaps exist in knowledge regarding women’s decision-making processes in relation to induced abortions in Kenya. Decision-making is a fundamental factor for consideration when planning and implementing contraceptive services. This study explored decision-making processes preceding induced abortion among women with unwanted pregnancy in Kisumu, Kenya.

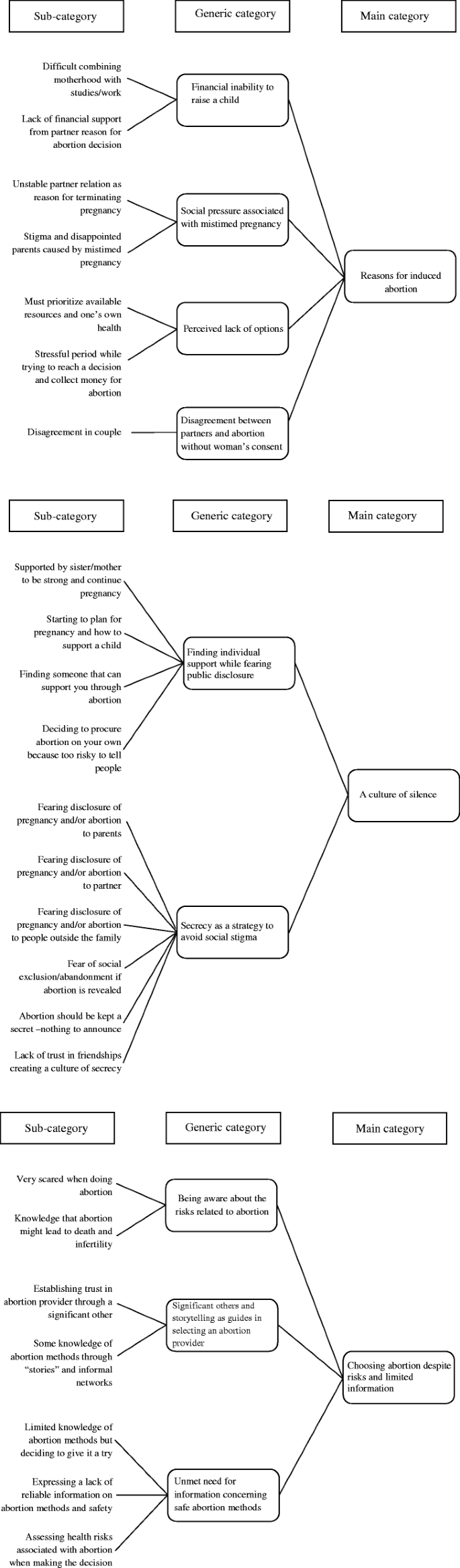

Individual face-to-face in-depth interviews were conducted with nine women aged 19–32 years old. Women who had experienced induced abortion were recruited after receiving post-abortion care at the Jaramogi Oginga Odinga Teaching and Referral Hospital (JOOTRH) or Kisumu East District Hospital (KDH) in Kisumu, Kenya. In total, 15 in-depth interviews using open-ended questions were conducted. All interviews were tape-recorded, transcribed and coded manually using inductive content analysis.