- Craft and Criticism

- Fiction and Poetry

- News and Culture

- Lit Hub Radio

- Reading Lists

- Literary Criticism

- Craft and Advice

- In Conversation

- On Translation

- Short Story

- From the Novel

- Bookstores and Libraries

- Film and TV

- Art and Photography

- Freeman’s

- The Virtual Book Channel

- Behind the Mic

- Beyond the Page

- The Cosmic Library

- The Critic and Her Publics

- Emergence Magazine

- Fiction/Non/Fiction

- First Draft: A Dialogue on Writing

- Future Fables

- The History of Literature

- I’m a Writer But

- Just the Right Book

- Lit Century

- The Literary Life with Mitchell Kaplan

- New Books Network

- Tor Presents: Voyage Into Genre

- Windham-Campbell Prizes Podcast

- Write-minded

- The Best of the Decade

- Best Reviewed Books

- BookMarks Daily Giveaway

- The Daily Thrill

- CrimeReads Daily Giveaway

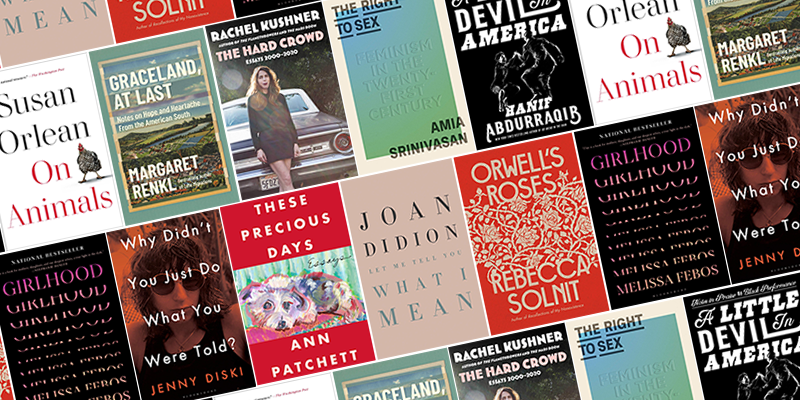

The Best Reviewed Essay Collections of 2021

Featuring joan didion, rachel kushner, hanif abdurraqib, ann patchett, jenny diski, and more.

Well, friends, another grim and grueling plague year is drawing to a close, and that can mean only one thing: it’s time to put on our Book Marks stats hats and tabulate the best reviewed books of the past twelve months.

Yes, using reviews drawn from more than 150 publications, over the next two weeks we’ll be revealing the most critically-acclaimed books of 2021, in the categories of (deep breath): Memoir and Biography ; Sci-Fi, Fantasy, and Horror ; Short Story Collections ; Essay Collections; Poetry; Mystery and Crime; Graphic Literature; Literature in Translation; General Fiction; and General Nonfiction.

Today’s installment: Essay Collections .

Brought to you by Book Marks , Lit Hub’s “Rotten Tomatoes for books.”

1. These Precious Days by Ann Patchett (Harper)

21 Rave • 3 Positive • 1 Mixed Read Ann Patchett on creating the work space you need, here

“… excellent … Patchett has a talent for friendship and celebrates many of those friends here. She writes with pure love for her mother, and with humor and some good-natured exasperation at Karl, who is such a great character he warrants a book of his own. Patchett’s account of his feigned offer to buy a woman’s newly adopted baby when she expresses unwarranted doubts is priceless … The days that Patchett refers to are precious indeed, but her writing is anything but. She describes deftly, with a line or a look, and I considered the absence of paragraphs freighted with adjectives to be a mercy. I don’t care about the hue of the sky or the shade of the couch. That’s not writing; it’s decorating. Or hiding. Patchett’s heart, smarts and 40 years of craft create an economy that delivers her perfectly understated stories emotionally whole. Her writing style is most gloriously her own.”

–Alex Witchel ( The New York Times Book Review )

2. Let Me Tell You What I Mean by Joan Didion (Knopf)

14 Rave • 12 Positive • 6 Mixed Read an excerpt from Let Me Tell You What I Mean here

“In five decades’ worth of essays, reportage and criticism, Didion has documented the charade implicit in how things are, in a first-person, observational style that is not sacrosanct but common-sensical. Seeing as a way of extrapolating hypocrisy, disingenuousness and doubt, she’ll notice the hydrangeas are plastic and mention it once, in passing, sorting the scene. Her gaze, like a sentry on the page, permanently trained on what is being disguised … The essays in Let Me Tell You What I Mean are at once funny and touching, roving and no-nonsense. They are about humiliation and about notions of rightness … Didion’s pen is like a periscope onto the creative mind—and, as this collection demonstrates, it always has been. These essays offer a direct line to what’s in the offing.”

–Durga Chew-Bose ( The New York Times Book Review )

3. Orwell’s Roses by Rebecca Solnit (Viking)

12 Rave • 13 Positive • 1 Mixed Read an excerpt from Orwell’s Roses here

“… on its simplest level, a tribute by one fine essayist of the political left to another of an earlier generation. But as with any of Solnit’s books, such a description would be reductive: the great pleasure of reading her is spending time with her mind, its digressions and juxtapositions, its unexpected connections. Only a few contemporary writers have the ability to start almost anywhere and lead the reader on paths that, while apparently meandering, compel unfailingly and feel, by the end, cosmically connected … Somehow, Solnit’s references to Ross Gay, Michael Pollan, Ursula K. Le Guin, and Peter Coyote (to name but a few) feel perfectly at home in the narrative; just as later chapters about an eighteenth-century portrait by Sir Joshua Reynolds and a visit to the heart of the Colombian rose-growing industry seem inevitable and indispensable … The book provides a captivating account of Orwell as gardener, lover, parent, and endlessly curious thinker … And, movingly, she takes the time to find the traces of Orwell the gardener and lover of beauty in his political novels, and in his insistence on the value and pleasure of things .”

–Claire Messud ( Harper’s )

4. Girlhood by Melissa Febos (Bloomsbury)

16 Rave • 5 Positive • 1 Mixed Read an excerpt from Girlhood here

“Every once in a while, a book comes along that feels so definitive, so necessary, that not only do you want to tell everyone to read it now, but you also find yourself wanting to go back in time and tell your younger self that you will one day get to read something that will make your life make sense. Melissa Febos’s fierce nonfiction collection, Girlhood , might just be that book. Febos is one of our most passionate and profound essayists … Girlhood …offers us exquisite, ferocious language for embracing self-pleasure and self-love. It’s a book that women will wish they had when they were younger, and that they’ll rejoice in having now … Febos is a balletic memoirist whose capacious gaze can take in so many seemingly disparate things and unfurl them in a graceful, cohesive way … Intellectual and erotic, engaging and empowering[.]”

–Michelle Hart ( Oprah Daily )

5. Why Didn’t You Just Do What You Were Told by Jenny Diski (Bloomsbury)

14 Rave • 7 Positive

“[Diski’s] reputation as an original, witty and cant-free thinker on the way we live now should be given a significant boost. Her prose is elegant and amused, as if to counter her native melancholia and includes frequent dips into memorable images … Like the ideal artist Henry James conjured up, on whom nothing is lost, Diski notices everything that comes her way … She is discerning about serious topics (madness and death) as well as less fraught material, such as fashion … in truth Diski’s first-person voice is like no other, selectively intimate but not overbearingly egotistic, like, say, Norman Mailer’s. It bears some resemblance to Joan Didion’s, if Didion were less skittish and insistently stylish and generated more warmth. What they have in common is their innate skepticism and the way they ask questions that wouldn’t occur to anyone else … Suffice it to say that our culture, enmeshed as it is in carefully arranged snapshots of real life, needs Jenny Diski, who, by her own admission, ‘never owned a camera, never taken one on holiday.’” It is all but impossible not to warm up to a writer who observes herself so keenly … I, in turn, wish there were more people around who thought like Diski. The world would be a more generous, less shallow and infinitely more intriguing place.”

–Daphne Merkin ( The New York Times Book Review )

6. The Hard Crowd: Essays 2000-2020 by Rachel Kushner (Scribner)

12 Rave • 7 Positive Listen to an interview with Rachel Kushner here

“Whether she’s writing about Jeff Koons, prison abolition or a Palestinian refugee camp in Jerusalem, [Kushner’s] interested in appearances, and in the deeper currents a surface detail might betray … Her writing is magnetised by outlaw sensibility, hard lives lived at a slant, art made in conditions of ferment and unrest, though she rarely serves a platter that isn’t style-mag ready … She makes a pretty convincing case for a political dimension to Jeff Koons’s vacuities and mirrored surfaces, engages repeatedly with the Italian avant garde and writes best of all about an artist friend whose death undoes a spell of nihilism … It’s not just that Kushner is looking back on the distant city of youth; more that she’s the sole survivor of a wild crowd done down by prison, drugs, untimely death … What she remembers is a whole world, but does the act of immortalising it in language also drain it of its power,’neon, in pink, red, and warm white, bleeding into the fog’? She’s mining a rich seam of specificity, her writing charged by the dangers she ran up against. And then there’s the frank pleasure of her sentences, often shorn of definite articles or odd words, so they rev and bucket along … That New Journalism style, live hard and keep your eyes open, has long since given way to the millennial cult of the personal essay, with its performance of pain, its earnest display of wounds received and lessons learned. But Kushner brings it all flooding back. Even if I’m skeptical of its dazzle, I’m glad to taste something this sharp, this smart.”

–Olivia Laing ( The Guardian )

7. The Right to Sex: Feminism in the Twenty-First Century by Amia Srinivasan (FSG)

12 Rave • 7 Positive • 5 Mixed • 1 Pan

“[A] quietly dazzling new essay collection … This is, needless to say, fraught terrain, and Srinivasan treads it with determination and skill … These essays are works of both criticism and imagination. Srinivasan refuses to resort to straw men; she will lay out even the most specious argument clearly and carefully, demonstrating its emotional power, even if her ultimate intention is to dismantle it … This, then, is a book that explicitly addresses intersectionality, even if Srinivasan is dissatisfied with the common—and reductive—understanding of the term … Srinivasan has written a compassionate book. She has also written a challenging one … Srinivasan proposes the kind of education enacted in this brilliant, rigorous book. She coaxes our imaginations out of the well-worn grooves of the existing order.”

–Jennifer Szalai ( The New York Times )

8. A Little Devil in America by Hanif Abdurraqib (Random House)

13 Rave • 4 Positive Listen to an interview with Hanif Abdurraqib here

“[A] wide, deep, and discerning inquest into the Beauty of Blackness as enacted on stages and screens, in unanimity and discord, on public airwaves and in intimate spaces … has brought to pop criticism and cultural history not just a poet’s lyricism and imagery but also a scholar’s rigor, a novelist’s sense of character and place, and a punk-rocker’s impulse to dislodge conventional wisdom from its moorings until something shakes loose and is exposed to audiences too lethargic to think or even react differently … Abdurraqib cherishes this power to enlarge oneself within or beyond real or imagined restrictions … Abdurraqib reminds readers of the massive viewing audience’s shock and awe over seeing one of the world’s biggest pop icons appearing midfield at this least radical of American rituals … Something about the seemingly insatiable hunger Abdurraqib shows for cultural transaction, paradoxical mischief, and Beauty in Blackness tells me he’ll get to such matters soon enough.”

–Gene Seymour ( Bookforum )

9. On Animals by Susan Orlean (Avid Reader Press)

11 Rave • 6 Positive • 1 Mixed Listen to an interview with Susan Orlean here

“I very much enjoyed Orlean’s perspective in these original, perceptive, and clever essays showcasing the sometimes strange, sometimes sick, sometimes tender relationships between people and animals … whether Orlean is writing about one couple’s quest to find their lost dog, the lives of working donkeys of the Fez medina in Morocco, or a man who rescues lions (and happily allows even full grown males to gently chew his head), her pages are crammed with quirky characters, telling details, and flabbergasting facts … Readers will find these pages full of astonishments … Orlean excels as a reporter…Such thorough reporting made me long for updates on some of these stories … But even this criticism only testifies to the delight of each of the urbane and vivid stories in this collection. Even though Orlean claims the animals she writes about remain enigmas, she makes us care about their fates. Readers will continue to think about these dogs and donkeys, tigers and lions, chickens and pigeons long after we close the book’s covers. I hope most of them are still well.”

–Sy Montgomery ( The Boston Globe )

10. Graceland, at Last: Notes on Hope and Heartache from the American South by Margaret Renkl (Milkweed Editions)

9 Rave • 5 Positive Read Margaret Renkl on finding ideas everywhere, here

“Renkl’s sense of joyful belonging to the South, a region too often dismissed on both coasts in crude stereotypes and bad jokes, co-exists with her intense desire for Southerners who face prejudice or poverty finally to be embraced and supported … Renkl at her most tender and most fierce … Renkl’s gift, just as it was in her first book Late Migrations , is to make fascinating for others what is closest to her heart … Any initial sense of emotional whiplash faded as as I proceeded across the six sections and realized that the book is largely organized around one concept, that of fair and loving treatment for all—regardless of race, class, sex, gender or species … What rises in me after reading her essays is Lewis’ famous urging to get in good trouble to make the world fairer and better. Many people in the South are doing just that—and through her beautiful writing, Renkl is among them.”

–Barbara J. King ( NPR )

Our System:

RAVE = 5 points • POSITIVE = 3 points • MIXED = 1 point • PAN = -5 points

- Share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Google+ (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Tumblr (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pocket (Opens in new window)

Previous Article

Next article, support lit hub..

Join our community of readers.

to the Lithub Daily

Popular posts.

Follow us on Twitter

Prayers for the Stolen: How Two Artists Portray the Violence of Human Trafficking in Mexico

- RSS - Posts

Literary Hub

Created by Grove Atlantic and Electric Literature

Sign Up For Our Newsletters

How to Pitch Lit Hub

Advertisers: Contact Us

Privacy Policy

Support Lit Hub - Become A Member

Become a Lit Hub Supporting Member : Because Books Matter

For the past decade, Literary Hub has brought you the best of the book world for free—no paywall. But our future relies on you. In return for a donation, you’ll get an ad-free reading experience , exclusive editors’ picks, book giveaways, and our coveted Joan Didion Lit Hub tote bag . Most importantly, you’ll keep independent book coverage alive and thriving on the internet.

Become a member for as low as $5/month

- NONFICTION BOOKS

- BEST NONFICTION 2023

- BEST NONFICTION 2024

- Historical Biographies

- The Best Memoirs and Autobiographies

- Philosophical Biographies

- World War 2

- World History

- American History

- British History

- Chinese History

- Russian History

- Ancient History (up to 500)

- Medieval History (500-1400)

- Military History

- Art History

- Travel Books

- Ancient Philosophy

- Contemporary Philosophy

- Ethics & Moral Philosophy

- Great Philosophers

- Social & Political Philosophy

- Classical Studies

- New Science Books

- Maths & Statistics

- Popular Science

- Physics Books

- Climate Change Books

- How to Write

- English Grammar & Usage

- Books for Learning Languages

- Linguistics

- Political Ideologies

- Foreign Policy & International Relations

- American Politics

- British Politics

- Religious History Books

- Mental Health

- Neuroscience

- Child Psychology

- Film & Cinema

- Opera & Classical Music

- Behavioural Economics

- Development Economics

- Economic History

- Financial Crisis

- World Economies

- How to Invest

- Artificial Intelligence/AI Books

- Data Science Books

- Sex & Sexuality

- Death & Dying

- Food & Cooking

- Sports, Games & Hobbies

- FICTION BOOKS

- BEST NOVELS 2024

- BEST FICTION 2023

- New Literary Fiction

- World Literature

- Literary Criticism

- Literary Figures

- Classic English Literature

- American Literature

- Comics & Graphic Novels

- Fairy Tales & Mythology

- Historical Fiction

- Crime Novels

- Science Fiction

- Short Stories

- South Africa

- United States

- Arctic & Antarctica

- Afghanistan

- Myanmar (Formerly Burma)

- Netherlands

- Kids Recommend Books for Kids

- High School Teachers Recommendations

- Prizewinning Kids' Books

- Popular Series Books for Kids

- BEST BOOKS FOR KIDS (ALL AGES)

- Ages Baby-2

- Books for Teens and Young Adults

- THE BEST SCIENCE BOOKS FOR KIDS

- BEST KIDS' BOOKS OF 2023

- BEST BOOKS FOR TEENS OF 2023

- Best Audiobooks for Kids

- Environment

- Best Books for Teens of 2023

- Best Kids' Books of 2023

- Political Novels

- New History Books

- New Historical Fiction

- New Biography

- New Memoirs

- New World Literature

- New Economics Books

- New Climate Books

- New Math Books

- New Philosophy Books

- New Psychology Books

- New Physics Books

- THE BEST AUDIOBOOKS

- Actors Read Great Books

- Books Narrated by Their Authors

- Best Audiobook Thrillers

- Best History Audiobooks

- Nobel Literature Prize

- Booker Prize (fiction)

- Baillie Gifford Prize (nonfiction)

- Financial Times (nonfiction)

- Wolfson Prize (history)

- Royal Society (science)

- Pushkin House Prize (Russia)

- Walter Scott Prize (historical fiction)

- Arthur C Clarke Prize (sci fi)

- The Hugos (sci fi & fantasy)

- Audie Awards (audiobooks)

Nonfiction Books » Essays

Browse book recommendations:

Nonfiction Books

- Best Nonfiction Books of 2022

- Best Nonfiction Books of 2023

- Best Nonfiction Books of 2024

- Best Nonfiction Books of the Past 25 Years

- Graphic Nonfiction

- Literary Nonfiction

- Narrative Nonfiction

- Nonfiction Series

- Short Nonfiction

“Essays root ideas in personal experience”, the philosopher Alain de Botton tells us in his interview in which he discussed five books of “illuminating essays”. He chooses The Crowded Dance of Modern Life by Virginia Woolf, as well as a selection of DW Winnicott , The Wisdom of Life by Arthur Schopenhauer, The Secret Power of Beauty by John Armstrong and Yoga for People Who Can’t be Bothered to Do It by Geoff Dyer, which “is in praise of slacker-dom and not doing very much. It’s not about Yoga at all.”

David Russell, Associate Professor at Oxford University, recommends the best Victorian essays , including selections by Charles Lamb , Matthew Arnold , George Eliot , Walter Pater and (one twentieth-century writer) Marion Milner and discusses the connection between the essay and the development of urban culture in the 19 th century.

Dame Hermione Lee, the writer's biographer, chooses her best books on Virginia Woolf . She discusses how and why her stature has grown so much since the 1960s and selects a range of her books including diaries and novels, as well as essays, including To the Lighthouse , which she considers Woolf’s greatest novel, her Diaries and her essay " Walter Sickert: A Conversation " , which can be seen as a meditation on the disparities between painting and writing as art forms.

Adam Gopnik , of the New Yorker , chooses Woolf’s The Common Reader as well as collections by Max Beerbohm , EB White , Randall Jarrell and Clive James .

The Best Essays: the 2021 PEN/Diamonstein-Spielvogel Award , recommended by Adam Gopnik

Had i known: collected essays by barbara ehrenreich, unfinished business: notes of a chronic re-reader by vivian gornick, nature matrix: new and selected essays by robert michael pyle, terroir: love, out of place by natasha sajé, maybe the people would be the times by luc sante.

Every year, the judges of the PEN/Diamonstein-Spielvogel Award for the Art of the Essay search out the best book of essays written in the past year and draw attention to the author's entire body of work. Here, Adam Gopnik , writer, journalist and PEN essay prize judge, emphasizes the role of the essay in bearing witness and explains why the five collections that reached the 2021 shortlist are, in their different ways, so important.

Every year, the judges of the PEN/Diamonstein-Spielvogel Award for the Art of the Essay search out the best book of essays written in the past year and draw attention to the author’s entire body of work. Here, Adam Gopnik, writer, journalist and PEN essay prize judge, emphasizes the role of the essay in bearing witness and explains why the five collections that reached the 2021 shortlist are, in their different ways, so important.

David Russell on The Victorian Essay

Selected prose by charles lamb, culture and anarchy and other writings by matthew arnold, selected essays, poems, and other writings by george eliot, studies in the history of the renaissance by walter pater, the hands of the living god: an account of a psychoanalytic treatment by marion milner.

With the advent of the Victorian age, polite maxims of eighteenth-century essays in the Spectator were replaced by a new generation of writers who thought deeply—and playfully—about social relationships, moral responsibility, education and culture. Here, Oxford literary critic David Russell explores the distinct qualities that define the Victorian essay and recommends five of its greatest practitioners.

With the advent of the Victorian age, polite maxims of eighteenth-century essays in the Spectator were replaced by a new generation of writers who thought deeply—and playfully—about social relationships, moral responsibility, education and culture. Here, Oxford literary critic David Russell explores the distinct qualities that define the Victorian essay and recommends five of its greatest practitioners.

The Best Virginia Woolf Books , recommended by Hermione Lee

To the lighthouse by virginia woolf, the years by virginia woolf, walter sickert: a conversation by virginia woolf, on being ill by virginia woolf, selected diaries by virginia woolf.

Virginia Woolf was long dismissed as a 'minor modernist' but now stands as one of the giants of 20th century literature. Her biographer, Hermione Lee , talks us through the novels, essays, and diaries of Virginia Woolf.

Virginia Woolf was long dismissed as a ‘minor modernist’ but now stands as one of the giants of 20th century literature. Her biographer, Hermione Lee, talks us through the novels, essays, and diaries of Virginia Woolf.

Adam Gopnik on his Favourite Essay Collections

And even now by max beerbohm, the common reader by virginia woolf, essays of e.b. white by e.b. white, a sad heart at the supermarket by randall jarrell, visions before midnight by clive james.

What makes a great essayist? Who had it, who didn’t? And whose work left the biggest mark on the New Yorker ? Longtime writer for the magazine, Adam Gopnik , picks out five masters of the craft

What makes a great essayist? Who had it, who didn’t? And whose work left the biggest mark on the New Yorker ? Longtime writer for the magazine, Adam Gopnik, picks out five masters of the craft

Illuminating Essays , recommended by Alain de Botton

The crowded dance of modern life by virginia woolf, home is where we start from by d w winnicott, the wisdom of life by arthur schopenhauer, the secret power of beauty by john armstrong, yoga for people who can’t be bothered to do it by geoff dyer.

The essay format allows the author to develop ideas but add a personal touch, says the popular philosopher Alain de Botton . Here, he chooses his favourite essay collections

The essay format allows the author to develop ideas but add a personal touch, says the popular philosopher Alain de Botton. Here, he chooses his favourite essay collections

We ask experts to recommend the five best books in their subject and explain their selection in an interview.

This site has an archive of more than one thousand seven hundred interviews, or eight thousand book recommendations. We publish at least two new interviews per week.

Five Books participates in the Amazon Associate program and earns money from qualifying purchases.

© Five Books 2024

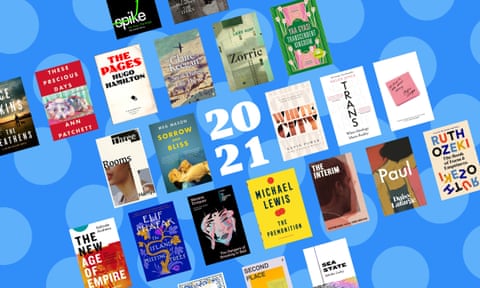

The best books of 2021, chosen by our guest authors

From piercing studies of colonialism to powerful domestic sagas, our panel of writers, all of whom had books published this year, share their favourite titles of 2021

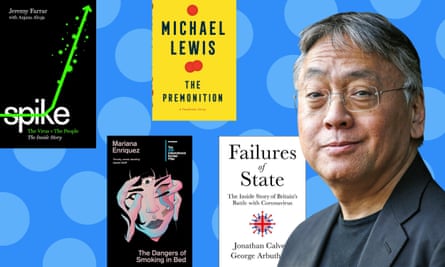

Kazuo Ishiguro

Author of Klara and the Sun (Faber)

The beautiful, horrible world of Mariana Enriquez, as glimpsed in The Dangers of Smoking in Bed (Granta), with its disturbed adolescents, ghosts, decaying ghouls, the sad and angry homeless of modern Argentina, is the most exciting discovery I’ve made in fiction for some time. Horrifying in another way, Jonathan Calvert and George Arbuthnott’s Failures of State (Mudlark) is a brilliantly presented indictment of the UK’s fumbling attempt to meet the Covid challenge. Read alongside Jeremy Farrar’s more personal Spike: The Virus v The People (Profile) and Michael Lewis’s compelling The Premonition (Allen Lane), we see a disturbing common trait emerging in our country and others: the unwillingness to prioritise people’s lives over ideas and ingrained structures.

Bernardine Evaristo

Author of Manifesto: On Never Giving Up (Hamish Hamilton)

I have been deeply impressed by recent books that invite us to reconsider aspects of British and global history, culture and identity beyond the often distorted, dishonest and pumped-up myth-making that has long prevailed. History is an interpretation of the past and these three books, each one powerfully persuasive and offering new ways of seeing, are in conversation with each other. Empireland : How Imperialism Has Shaped Modern Britain (Penguin) by Sathnam Sanghera, The New Age of Empire : How Racism and Colonialism Still Rule the World (Allen Lane) by Kehinde Andrews and Green Unpleasant Land : Creative Responses to Rural England’s Colonial Connection s (Peepal Tree Press) by Corinne Fowler.

Damon Galgut

Author of The Promise (Chatto & Windus)

I seldom read books when they first appear, but there were two slim volumes that especially impressed me this year. Burntcoat (Faber) by Sarah Hall is in the vanguard of a new genre of pandemic/lockdown fiction: the connections between isolation and creation are laid bare in a disquieting dystopia of the not-quite-now. Small Things Like These (Faber) by Claire Keegan, on the other hand, casts its gaze backward, to Ireland in 1985; its balance of crystalline language and moral seriousness makes it profoundly moving.

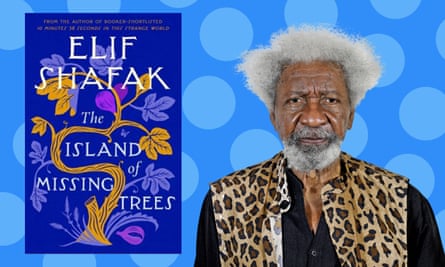

Wole Soyinka

Author of Chronicles From the Land of the Happiest People on Earth (Bloomsbury)

I sometimes suspect that I was actually found abandoned in a tree, adopted and raised as a family secret. Amos Tutuola, Gabriel García Márquez, DO Fagunwa, Shahrnush Parsipur and other exponents of tree anthropomorphism are perhaps the outsiders in the know. Now they are joined by Elif Shafak in The Island of Missing Trees (Viking) with her integrative literary sensibility, and the genre sprang back on its feet, tender and savage by turns in a Greco-Turkish-Cypriot historic setting. The rigorous questioning of nation and identity, given my incessant preoccupations, made it a truly therapeutic literary meal.

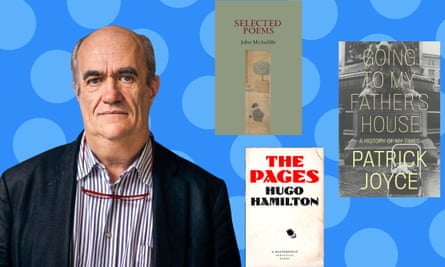

Colm Tóibín

Author of The Magician (Viking)

I enjoyed Hugo Hamilton’s The Pages (Fourth Estate), narrated with verve and ingenuity by an actual book, a novel by Joseph Roth, which got saved from the Nazi bonfire and then taken on a picaresque journey across the Atlantic and back to Germany. I also enjoyed the social historian Patrick Joyce’s Going to My Father’s House (Verso), a haunting meditation on Ireland and England, war and migration, Derry and Manchester. I admired the originality of his observations and his tone of melancholy, calm wisdom. I love John McAuliffe’s Selected Poems (Gallery) for the way that ordinary things are rendered and rhythm handled so deftly and artfully.

Rachel Kushner

Author of The Hard Crowd: Essays 2000–2020 (Jonathan Cape)

My generation is very much marked by Dennis Cooper’s George Miles cycle: in the 1990s, everyone read these books; I was awed by them. For many years, Dennis took a break from novels to focus on theatre and film. He’s back with I Wished (Soho Press), which is classic Dennis Cooper: intricate, funny, destabilising and totally unforeseen. Wolfgang Hilbig is apparently one of the most acclaimed German writers, but was new to me. I’ll confess I fell for the blurb on the back of The Interim (Two Lines Press): the great László Krasznahorkai calls him “an artist of immense stature”. As soon as I started reading, I had to agree. This novel, translated by Isabel Fargo Cole, is comic and terrifying and profound.

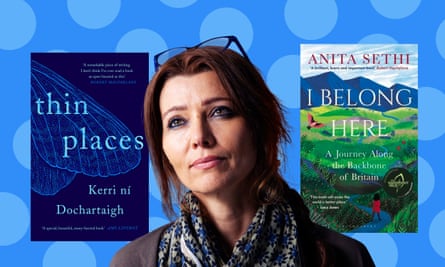

Elif Shafak

Author of The Island of Missing Trees (Viking)

This year, reading Anita Sethi’s I Belong Here (Bloomsbury) was an unforgettable journey. Sethi wrote this book after being the victim of a horrible racist attack on a train from Liverpool to Newcastle. The genius of the author is how she takes the narrative of hatred and discrimination hurled at her and turns it upside down by “going back to where she is from” – the landscapes of the north. Through long walks in nature as she finds a true sense of belonging, connectivity, renewal and hope, so do we, her readers. I found it not only deeply moving but also quietly transformative. Another read that stayed with me this year has been Kerri ní Dochartaigh’s fabulous Thin Places (Canongate). Born in Derry, at the height of the Troubles, the author’s voice is piercingly honest, movingly heartfelt. There is so much soul and knowledge and compassion, it gave me shivers.

Author of Burntcoat (Faber)

Sea State (Fourth Estate) by Tabitha Lasley completely took me by surprise. Part memoir, part investigation into oil-rig culture, part critique of gender and class dynamics, it’s incredibly compelling, often dark as the drilled-for product. Lasley infiltrates this masculine offshore industry, with its dangers, profit and comradeship. She also explores female loneliness and desire, accommodation of a male-designed world and the spaces where women hold power. Reissued this year with impassioned praise from fellow authors such as Marlon James, Patricia Lockwood and Max Porter, Mrs Caliban (Faber) by Rachel Ingalls is a work of true verve and imagination. Along with her suburban housewife and lab-tested reptilian lover, Ingalls deftly, wittily and rather incredibly liberates readers from the awfulness of convention to a state where weirdness and otherness are beautiful and right.

Author of Sorrow and Bliss (Weidenfeld and Nicolson)

After the joy of discovering that one of your favourite authors has a new book out can follow a peculiar kind of anxiety, because what if you don’t like it as much as the others? I needn’t have worried with Rachel Cusk’s Second Place (Faber). It is stunning, in all senses. Assembly (Hamish Hamilton) by Natasha Brown left me winded for how clever and sad and beautiful and spare it was. Truly the perfect novel. And I adored Ann Patchett’s new essay collection, These Precious Days (Bloomsbury), which I read in November and will end the year by listening to her read, as audio. Because it’s Ann Patchett, one time through isn’t enough.

Caleb Azumah Nelson

Author of Open Water (Viking)

This year, I loved Transcendent Kingdom (Viking) by Yaa Gyasi, the story of a family of four who travel from Ghana to Alabama to make a new life for themselves. Through the course of the novel, the family’s history begins to unfold, illuminating stories that have gone unspoken for generations. It’s a brilliant novel, with not a word out of place. I also really enjoyed Vanessa Onwuemezi’s Dark Neighbourhood (Fitzcarraldo), a collection of short stories from an unforgettable, searing voice. They occupy a hallucinatory landscape, often veering into the surreal, and each pulses with an electric energy.

Lauren Groff

Author of Matrix (Heinemann)

I have been in headlong love with Patricia Lockwood’s hilarious and subversive mind since her memoir Priestdaddy , but her first novel, No One Is Talking About This (Bloomsbury) , sent me reeling. Everything about this book, from its structure to its prose to the way it hits a reader unawares in the second half, is testament to Lockwood’s wicked genius. Everyone Knows Your Mother Is a Witch (Fourth Estate) by Rivka Galchen flew a bit under the radar, but it is a wise meditation on the kind of hysterical scapegoating we see so often in the age of the internet, though based on a historical fact: that the mother of astronomer Johannes Kepler was once accused of witchcraft. I loved this book intensely when I read it this summer and have thought of it nearly every day through this strange autumn. I’ve been thinking deeply about anagogical literature recently and very few living writers write so achingly toward God as Kaveh Akbar. Real faith, Akbar writes in Pilgrim Bell (Chatto & Windus), “passes first through the body/ like an arrow”; each of the poems in this collection finds its target.

Chibundu Onuzo

Author of Sankofa (Virago)

My favourite nonfiction book published in 2021 was Otegha Uwagba’s We Need to Talk About Money (Fourth Estate). It’s a memoir that shows how money has affected every stage of Uwagba’s life, from growing up on a council estate, to winning a scholarship to a private school, to negotiating her salary when she entered the workforce. Uwagba is particularly nuanced about class and race. My favourite novel published in 2021 was Our Lady of the Nile (Daunt) by Scholastique Mukasonga. It’s set in the 1980s, in a Rwandan girls boarding school. It follows all the girlish intrigues, of who is the most popular, who is the prettiest, but this is no Malory Towers . Looming in the background is the coming genocide. Both playful and sinister, this is an excellent read.

Olivia Laing

Author of Everybody: A Book About Freedom (Picador)

Anyone with a mother ought to read My Phantoms by Gwendoline Riley (Granta), a novelist of uncompromising brilliance. It mines the same narrow, dangerous territory as Beryl Bainbridge and Ivy Compton-Burnett: the dysfunctional family unit. Riley homes in on the failing relationship between a mother and daughter, anatomised by way of astonishingly precise dialogue, alongside angular, razor-sharp sentences that delineate an entire emotional landscape. Ouch and wow. There’s a similar marvel of ventriloquism in Adam Mars-Jones’s Batlava Lake (Fitzcarraldo), a story about war and soldiers delivered by the hopeless, weirdly endearing Barry, which builds to a blindsiding final paragraph.

Sunjeev Sahota

Author of China Room (Harvill Secker)

Barbara Ehrenreich is an incisive diagnostician of societies and in Had I Known: Collected Essays (Granta) she is clear-eyed on the ways in which the American working class has been politically abandoned and culturally demonised. Much of the analysis applies to our own country. On the novel front, I could not recommend more strongly Gwendoline Riley’s My Phantoms (Granta): flinty, bracing, exquisite.

Anthony Doerr

Author of Cloud Cuckoo Land (Fourth Estate)

In The Dawn of Everything: A New History of Humanity (Allen Lane), David Graeber and David Wengrow offer an engrossing series of insights into how “the conventional narrative of human history is not only wrong, but quite needlessly dull”. They re-inject humanity into our distant forebears, suggesting that our prevailing story about human history – that not much innovation occurred in human societies until the invention of agriculture – is utterly wrong. I could have lived in the first hundred pages of Piranesi (Bloomsbury) by Susanna Clarke for ever. It’s a dream of a novel. Zorrie (Riverrun; published early next year) by Laird Hunt is a tender, glowing novel that is just as beautiful as Marilynne Robinson’s Gilead or Denis Johnson’s Train Dreams .

Ferdinand Mount

Author of Kiss Myself Goodbye: The Many Lives of Aunt Munca (Bloomsbury)

These days, I seem to read mostly female novelists from the colder parts of North America. You can’t get much farther north than the Ontario of Mary Lawson’s icy, compelling stories of calamity and redemption. A Town Called Solace (Chatto) keeps you breathless with anxiety, then relief and finally even joy. I felt the same total engagement with Gill Hornby’s Miss Austen (Arrow). She reconstructs in beautifully simple detail the story of Jane Austen’s sister, Cassandra, and her struggle to protect Jane in life and death. It is also an unforgettable account of an unremembered life.

Kehinde Andrews

Author of The New Age of Empire (Allen Lane)

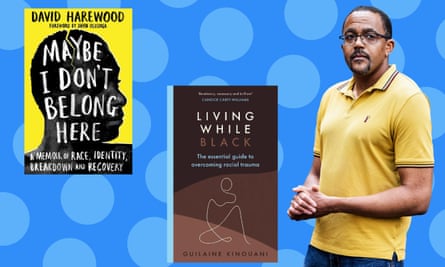

David Harewood’s documentary Psychosis and Me was an eye-opener for his honesty in reflecting on his experiences in the mental health system. His book Maybe I Don’t Belong Here (Bluebird) is one of the most powerful testimonies to the impact of racism I have ever read. In a similar vein, Guilaine Kinouani’s Living While Black (Ebury) highlighted the severe problem of racism in the psychological professions that has hallmarked so much of our experiences in the UK, an unfortunate experience we have in common with our American cousins. I had been looking forward to learning more about one of the most important US civil rights activists Fannie Lou Hamer and Keisha Blain’s Until I Am Free (Beacon) did not disappoint.

Author of The Book of Form and Emptiness (Canongate)

Double Blind (Harvill Secker) by Edward St Aubyn is about nature, science, rapacious capitalism, psychoanalysis and human folly, and it is both moving and so funny I had to stop every few pages to wipe tears from my eyes. Nobody’s Normal (WW Norton) by Roy Richard Grinker is a compassionate, well-researched chronicle of the historical stigmatisation of mental illness. Since “normal” is a social construct, why can’t we change it? I love how Katie Kitamura can channel a mind and in Intimacies (Vintage) it is the mind of an unnamed interpreter living in The Hague, interpreting for a former president on trial for war crimes.

Monique Roffey

Author of The Mermaid of Black Conch (Vintage)

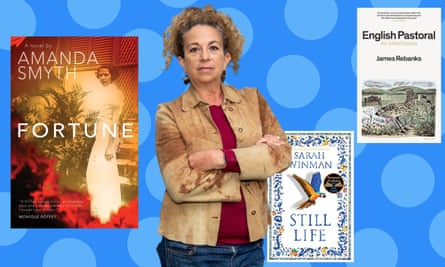

Still Life (Fourth Estate) by Sarah Winman gets my vote, not just for its mastery and sweep (Tuscany, the East End of London, war and beyond war, old gay ladies, young men) and the overarching theme of the power of love, but for its talking parrot as character, Claude. Claude gets some of the best lines. Also, Fortune (Peepal Tree Press) , by Amanda Smyth, another historic novel, a clandestine love story set amid Trinidad’s early oil drilling years in the 1920s. I also loved English Pastoral : An Inheritanc e (Penguin) by James Rebanks, out in paperback this year. His family have farmed the same land for 600 years. We’ve lost so much, but Rebanks gives us solutions and myth-busts; a poignant and sad book we need in a time of climate emergency.

Elizabeth Day

Author of Magpie (Fourth Estate)

My two favourite novels of the year were Sorrow and Bliss (Weidenfeld & Nicolson) by Meg Mason, for being hilarious, moving and utterly humane, and Damon Galgut’s The Promise (Chatto). The label “masterpiece” is far too liberally applied these days, but I did think Galgut’s book was deserving of it. In nonfiction, I enjoyed We Need to Talk About Money (Fourth Estate) by Otegha Uwagba, which challenged me to rethink my relationship with my finances and did so in a witty, intelligent and surprisingly touching way.

Author of The Echo Chamber (Doubleday)

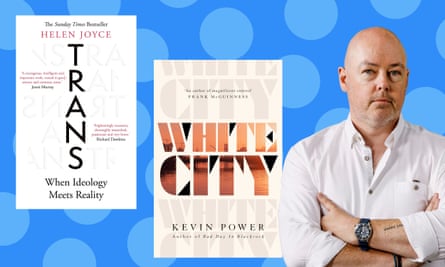

Kevin Power’s long-awaited second novel, White City (Scribner), was a triumph. There’s not enough humour in contemporary fiction but Power brought the laughs and the pathos to this account of a young Dubliner, reared with privilege, who gets involved in a dodgy land deal in the Balkans. In nonfiction, I was impressed by Helen Joyce’s Trans: When Ideology Meets Reality (Oneworld), a scholarly, compassionate and courageous examination of a subject that’s sparked an unhelpful civil war within the LGBTQ community. Unlike those of her online counterparts, Joyce’s arguments are well researched, soundly made and avoid the toxicity that mars so much conversation on this topic.

Courttia Newland

Author of A River Called Time (Canongate)

Keeping the House (And Other Stories) by Tice Cin is a truly beautiful debut. A mistress of deftly sketched characters that become whole humans in a few lines, Cin tells stories of working-class, inner-city life steeped in truth, emotion and vulnerability. She is one of a new generation of writers who see the splendour of these streets and articulate it with great majesty. Jo Hamya’s Three Rooms (Vintage) is written in a classical style that’s no less incisive for its formality. From the first paragraph, I was hooked. Tension drips through every scene and Hamya depicts London so well. There’s quiet, raw power in this book and its author.

Cathy Rentzenbrink

Author of Everyone Is Still Alive (Phoenix)

I like a novel to grab me and The Book of Form and Emptiness (Canongate) by Ruth Ozeki gave me very peculiar dreams for a long time, as though it did not want to release me to other things. I enjoyed the robust style of Empireland (Penguin) by Sathnam Sanghera, an illuminating examination of the “toxic cocktail of nostalgia and amnesia” that still hugely influences our life today. Erudite and reassuring , Four Thousand Weeks (Vintage) by Oliver Burkeman persuaded me to accept that my time on Earth is finite so I should therefore not fritter it away in overwork and overwhelm.

Author of Razorblade Tears (Headline)

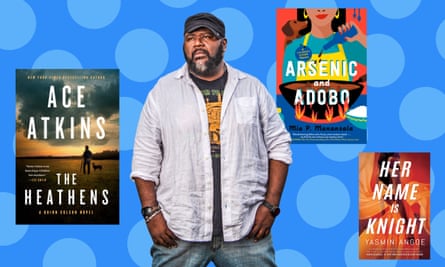

Her Name Is Knight (Thomas & Mercer) by Yasmin Angoe is a dazzling, suspenseful tale of international intrigue and revenge with a protagonist who is as deadly as she is beautiful. A feared assassin, Nena Knight soon finds her latest mission to be her most dangerous as it puts her life and her heart at risk. Arsenic and Adobo by Mia Manansala is a quirky, cosy mystery full of humour and heart with a clever heroine who is as talented in the kitchen as she is at a murder scene. A fantastic debut. The Heathens (Little, Brown) by Ace Atkins is pure, uncut, US southern noir with a modern social media twist. Few writers know the tortured soul of the south better than Atkins and he is at the top of his game here.

Fintan O’Toole

Author of We Don’t Know Ourselves: A Personal History of Ireland Since 1958 (Head of Zeus)

Sally Rooney’s Beautiful World, Where Are You (Faber) has really stayed with me. For all its wit and style, it has a deep seriousness about the world. Rooney has an old-fashioned belief that the novel can be a place in which the question of how we should live is continually at play. Damon Galgut’s The Promise (Chatto) sustains the same moral purpose while being funny, angry and absurd all at once. Paul Muldoon had a remarkable year. His conversations with Paul McCartney for The Lyrics (Allen Lane) spark endlessly fascinating reflections on the relationship between life and creativity. And his new collection, Howdie-Skelp (Faber), is dazzling, moving, profound and playful.

Author of Bessie Smith (Faber)

I loved Neil Bartlett’s Address Book (Inkandescent). It took me back to all the addresses I’ve lived in - the lesbian squat in Vauxhall, John le Carré’s house in Hampstead! Brilliantly written, interweaving seven different characters across various times, Bartlett’s precise storytelling pulled me in. I’m glad we have him. He is a pioneering chronicler of queer lives. Ian Duhig’s New and Selected Poems (Picador) is a must have, must read gathering of the best of his work. Always fascinating, Duhig is poetry’s best chronicler of both ordinary lives, strange lives. His eclectic and effervescent work draws on folklore and myth to tell the stories we never get to hear. Duhig is interested in everything. He makes his reader sit up and take stock. I was inspired by the beauty and the power of the fabulous collective 4 Brown Girls Who Write – their poetry reminds me of the strength and exhilaration of a collective voice. Beautifully produced by Rough Trade Books, each of the four poets produces a standalone pamphlet that comes to form part of an incredible whole. The perfect stocking pressie. I was touched by Michelle Zauner’s cathartic memoir about losing her mother, Crying in H Mart (Picador). Zauner writes about food, music, grief and love candidly, bravely.

Chris Power

Author of A Lonely Man (Faber)

Two novels that stunned me this year involve characters overwhelmed by the force of another’s personality. The narrator of Gwendoline Riley’s My Phantoms (Granta) reckons with her parents, one dead, one ailing, who emerge as both spiteful and pitiable. Riley is an immensely talented writer whose sentences cut like knives and she doesn’t flinch when blade meets bone. Similarly dauntless, in Second Place (Faber), Rachel Cusk abandons the distinctive style of her Outline trilogy for a new voice. When M invites L, a painter she admires, to her remote coastal home, psychic combat ensues. It’s a profound book and a funny one, which hasn’t been mentioned enough.

Megan Nolan

Author of Acts of Desperation (Jonathan Cape)

After the past few years, when even the most ignorant among us took to slinging around virology terms as though we knew what we were talking about, I’ve found myself drawn to accounts and oral histories of the Aids crisis. Let the Record Show (Farrar) by Sarah Schulman is profoundly moving, as most are, but also does the important work of reasserting the place of women and people of colour in the history of Act Up. Paul (Granta) by Daisy Lafarge is a mesmerising novel about a young woman’s trip to France and ensuing entanglement with a man whose grotesque secrets begin to surface. It moves at a pace it feels Lafarge invented herself. It’s enviably, coolly intelligent without ever becoming ironic or snide and just one more exposition of Lafarge’s many gifts following on from her poetry collection Life Without Air .

Joshua Ferris

Author of A Calling for Charlie Barnes (Viking)

Three great pleasures for me this year came from reliable sources. Jo Ann Beard’s essays in Festival Days (Little, Brown) are some of her finest. Dana Spiotta’s novel Wayward (Virago) is razor-sharp on any number of things, above all the insoluble ravages of time. Then there were three writers new to me whose books were both reinvigorating and enlightening: Angélique Lalonde’s Glorious Frazzled Beings (Astoria), Miriam Toews’s Fight Night (Bloomsbury) and Casey Plett’s A Dream of a Woman (Arsenal Pulp Press).

Lisa Taddeo

Author of Animal (Bloomsbury)

Magpie (Fourth Estate) by Elizabeth Day is that rare novel that moves and taunts like a thriller, but also envelops and comforts like Middlemarch . I didn’t want it to end, I wanted to read it in fancy bars for ever. As for The Right to Sex (Bloomsbury) by Amia Srinivasan , I cannot say enough about this book. How crucial. How brilliant. How absolutely gratifying to see a mind at work like Srinivisan’s, handling the profane and the erudite with equal clear, unflinching diamond prose.

Sathnam Sanghera

Author of Empireland (Viking)

My novel of the year would be A Calling for Charlie Barnes (Viking) by Joshua Ferris, a hilarious skewering of the American Dream by the man who must be the funniest writer we have. I also really appreciated The Anarch y (Bloomsbury) by William Dalrymple, out in paperback this year, which does a great job explaining the East India Company, responsible, more than anything else, for Britain’s involvement in the subcontinent. And Imperial Nostalgia (Manchester University Press) by Peter Mitchell, which explains how the delusions of the Raj continue to shape our national psychology today.

Joan Bakewell

Author of The Tick of Two Clocks: A Tale of Moving On (Virago)

The sensitivity of Susie Boyt’s story of family love, Loved and Missed (Little, Brown), wrings the heart: it shows tenderness to each, makes you care for all… a gentle masterpiece. The Promise (Chatto) by Damon Galgut is a remarkable tale of four generations of one South African family and of the country itself. Like his earlier books, which I have also enjoyed, it reveals him as a master of human complexity. No wonder it won the Booker. Mothering Sunday (Scribner) by Graham Swift was not published this year, I know, but was picked up by me at the secondhand stall of Didcot Parkway station. It’s now released as a film. Reading it, I discovered a total gem: not a word out of place, not a false sentiment. Can the film be as good?

To order any of these books for a special price click on the titles or go to guardianbookshop.com . Delivery charges may apply

Let us know what your favourite books of the year were in the comments below

- Best books of 2021

- History books

- Politics books

- Short stories

Five of the Best Books of 2021

The novels, nonfiction, and memoirs that stood out most: Your weekly guide to the best in books

Much of 2021 has been filled with a dull sense of déjà vu as the coronavirus pandemic has continued to shrink social worlds and batter morale. Many of the books our writers and editors were drawn to investigated failure, grief, apocalypse—resonant themes at a time of constant rupture and regression. Others helped jolt readers out of routines, and stretched the imagination. The works below span fiction, poetry, memoir, and reportage, but they share a keen sense of the world as it is and as it could be.

You can read the Culture team’s full selections here .

Every Friday in the Books Briefing , we thread together Atlantic stories on books that share similar ideas. Know other book lovers who might like this guide? Forward them this email. When you buy a book using a link in this newsletter, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.

What We’re Reading

Little, Brown

Assembly , by Natasha Brown

“Dissolve yourself into the melting-pot,” says the narrator of Assembly . “And then flow out, pour into the mould. Bend your bones until they splinter and crack and you fit. Force yourself into their form.” Natasha Brown’s debut novel is propelled by elegant, elliptical, violent lines like that. Its story, on the surface, is sparse. The narrator, a Black woman living in London whose name is never revealed, goes to work (the job is a financially lucrative and spiritually vampiric role in banking). She goes to a party (thrown by the parents of her wealthy, white boyfriend, on their ancient estate). She goes to the doctor. There is a pointed plot twist I won’t spoil, but what makes Assembly singular, in the end, is less its story than the manner of its storytelling . The narrator’s assessments of her life, rendered primarily in the first person, are studies of evocative contrasts. She reveals, and she withholds. She observes, and she watches herself being observed. She documents the casual cruelties that shape her daily life—and she defies them. — Megan Garber

Tin House Books

Always Crashing in the Same Car: On Art, Crisis, and Los Angeles, California , by Matthew Specktor

Matthew Specktor’s sad and entrancing book takes as its topic failure, “a pattern of mind,” he writes, that is also, “when we are close to it, delicious.” A child of Hollywood—his mother was an unhappy screenwriter, his father a high-powered agent—he focuses his attention on its denizens, exploring artists meaningful to him “whose careers carry an aura of what might … have been.” Specktor is a sharp cultural critic, but he also writes with the sweet conviction of someone who still has heroes, and he opts to consider foundering a virtue. With that lens, he examines the lives of folks such as the coolly talented writer Eleanor Perry, who never got sufficient credit for work that she’d done with her husband, Frank, but then wrote a gimlet-eyed novel about her marriage; or the vibrant yet aloof actor Tuesday Weld, constantly on the verge of becoming a starlet but perhaps also saved by her ambivalence about fame. Specktor threads into these essaylike chapters a portrait of his own tempestuous allegiance to this city of dashed fantasies. Dreams, he suggests, don’t protect you. But he begins to wonder, as I did, whether failure, brutal though it is, “mightn’t have been the real pursuit all along.” — Jane Yong Kim

Farrar, Straus and Giroux

The Right to Sex , by Amia Srinivasan

In 2018, the philosopher Amia Srinivasan published a viral essay for the London Review of Books that interrogated the formation of our sexual desires. Modern feminism’s impulse to think about sex in individualistic terms, she wrote, fails to acknowledge how broader political forces shape what we want. Her incisive book expands on the original essay, covering sexual assault, false rape accusations, porn, #MeToo, and sex work. Srinivasan excels at closely analyzing, then questioning, the facts of our sexual lives that we might take for granted. In the essay “Talking to My Students About Porn,” she is surprised by both her students’ and her own conservatism, expressing wariness of porn’s power to define sex for kids raised in the internet age. She doesn’t accomplish her lofty aim of completely reimagining sex, but that very ambition is what makes the book so successful. The Right to Sex clears the slate for others to imagine a future in which physical intimacy is, in her words, equal, joyful, and free. — Kate Cray

Afterparties , by Anthony Veasna So

Afterparties often moves like a boomerang––zippily flitting back and forth among its characters to create a ricochet effect. The nine short stories in Anthony Veasna So’s debut collection feature an ensemble of young Cambodian Americans whose parents and grandparents fled the horrors of the Khmer Rouge regime; this generation, though, is more familiar with the streets and storefronts of Stockton, California. So writes about this community—and about family, sex, and cultural inheritance— with a sharp-toothed, darkly comic bent . “Every Ma has been a psycho since the genocide,” one character muses; another achieves enlightened clarity about his boyfriend’s VC-funded “safe space” app while in the throes of a threesome. This Khmer choir of voices is, at turns, horny, haunted, irreverent, and hustling. The stories careen between doughnut shops and Buddhist temples, and spiritual reincarnation figures into several plotlines. So’s narrators sometimes balk at their parents’ religiosity, but they still can’t quite abandon the belief that their ancestors move among them. The author died last year unexpectedly, months before the book’s publication; one can’t shake the feeling that he, too, meanders through these stories now. — Nicole Acheampong

Random House

Invisible Child: Poverty, Survival & Hope in an American City , by Andrea Elliott

The investigative reporter Andrea Elliott met Dasani, an 11-year-old Black girl living in a Brooklyn homeless shelter, in 2012. Her family of 10 was crammed into a single room where roaches scaled the walls and the baby’s crib was heated by a hair dryer; just blocks away were posh townhouses. One of 22,000 unhoused children in one of the most unequal cities in America, Dasani—named after the bottled water that her mother could never afford—stood out to Elliott for her astuteness and idealism. Every morning, before getting her siblings ready for school, she would stare out at the Empire State Building, which, she told Elliott, made her “feel like there’s something going on out there.” For eight years, Elliott followed the family almost everywhere—to school, court, welfare offices, and therapy sessions—and researched their ancestors. (Elliot learned that Dasani’s great-grandfather was a decorated World War II veteran who—unaided by the GI Bill that elevated millions of white veterans into the middle class—was unable to secure a mortgage in redlined Brooklyn.) The resulting book is at once a tender portrait of a family, and a tour of America’s broken welfare systems and racist policies. — Stephanie Hayes

About us: This week’s newsletter is written by the Atlantic’s Culture desk. Comments, questions, typos? Reply to this email to reach the Books Briefing team. Did you get this newsletter from a friend? Sign yourself up .

Most Read in 2021

Year-End Lists!

We don’t publish a lot of lists. But this year, having launched this new website with nearly complete access to 30 years of magazine archives, we thought it seemed like a good time to look back at the stories that resonated with our readers.

In that spirit, we’ve compiled the most-read pieces published on our website in 2021, as well as the most-read work from our archives.

And for good measure, we’ve pulled together a few pieces worth an honorable mention; our favorite Sunday Short Reads ; CNF content that was republished elsewhere; and the best advice, inspiration, and think pieces from some of our favorite publications.

Finally, if you enjoy what follows, please know there’s plenty more! We have a soft paywall on our site, which allows for three free reads a month. To get unlimited access for as little as $4/month, simply subscribe today.

Top 10 Published in 2021

- Almost Behind Us A dental emergency interrupts a meaningful anniversary // JENNIFER BOWERING DELISLE

- El Valle, 1991 An early lesson in strength and fragility // AURELIA KESSLER

- Stay at Home All those hours alone with a new baby can be rough // JARED HANKS

- The Desert Was His Home There are many things we don’t know about Mr. Otomatsu Wada, and a few things we do // ERIC L. MULLER

- Just a Big Cat The dramatic boredom of jury duty // ERICA GOSS

- What Will We Do for Fun Now? Her parents survived World War II and the Blitz just fine … didn’t they? // JANE RATCLIFFE

- Harriet Two brothers and a turtle // TYLER McANDREW

- Rango Getting existential at a funeral for a lizard // JARRETT G. ZIEMER

- Mouse Lessons from a hamster emergency // BEVERLY PETRAVICIUS

- Roxy & the Worm Box Trying to recapture a childhood love of dirt // ANJOLI ROY

Top 5 from the Archive

- Picturing the Personal Essay A visual guide // TIM BASCOM

- The 5 Rs of Creative Nonfiction The essayist at work // LEE GUTKIND

- The Line Between Fact & Fiction Do not add, and do not deceive // ROY PETER CLARK

- The Braided Essay as Social Justice Action The braided essay may be the most effective form for our times // NICOLE WALKER

- On Fame, Success, and Writing Like a Mother#^@%*& An interview with Cheryl Strayed // ELISSA BASSIST

Honorable Mention ( ICYMI Essays)

- Latinx Heritage Month Who do you complain to when it’s HR you have a problem with? // MELISSA LUJAN MESKU

- Women’s Work Sometimes, freedom means choosing your obligations // EILEEN GARVIN

- Bloodlines and Bitter Syrup Avoiding prison in Huntsville, Texas, is nearly impossible // WILL BRIDGES

- Stealth A nontraditional couple struggles with keeping part of their life together private while undertaking the public act of filing for marriage // HEATHER OSTERMAN-DAVIS

- Something Like Vertigo An environmental writer sees parallels between her father’s declining equilibrium and a world turned upside down // ELIZABETH RUSH

Our favorite Sunday Short Reads from our partners

from BREVITY

- What Joy Looks Like SSR #128 // DORIAN FOX

- How to Do Nothing SSR #156 // ABIGAIL THOMAS

from DIAGRAM

- At 86, My Grandmother Regrets Two Things SSR #134 // DIANA XIN

- The Seedy Corner SSR #140 // KIMBERLY GARZA

from RIVER TEETH

- Waste Not SSR #131 // DESIREE COOPER

- This Is Orange SSR #141 // JILL KOLONGOWSKI

from SWEET LITERARY

- The Pilgrim’s Prescription SSR #122 // CAROLYN ALESSIO

- Leaves in the Hall SSR #160 // ANNE GUDGER

Our favorite stories from around the internet.

Advice & Inspiration

- In Praise of the Meander Rebecca Solnit on letting nonfiction narrative find its own way (via Lit Hub )

- What’s Missing Here? A Fragmentary, Lyric Essay About Fragmentary, Lyric Essays Julie Marie Wade on the mode that never quite feels finished (via Lit Hub )

- Getting Honest about Om A brief essay on audience (via Brevity )

- Using the Personal to Write the Global Intimate details, personal exploration and respect for facts (via Nieman Storyboard )

- Fix Your Scene Shapes And quickly improve your manuscript (via Jane Friedman’s blog)

The State of Nonfiction

- What the NYT ‘Guest Essay’ Means for the Future of Creative Nonfiction Description (via Brevity )

- How the Role of Personal Expression and Experience Is Changing Journalism On the future of the newsroom (via Poynter )

- 50 Shades of Nuance in a Polarized World An essayist ponders when to write black-and-white polemics that attract clicks, and when to be more considered (via Nieman Storyboard )

- These Literary Memoirs Take a Different Tack Description (via NY Times )

- The Politics of Gatekeeping On reconsidering the ethics of blind submissions (via Poets & Writers )

Our Most-Read Stories of 2021

In a year that was haunted by the continuing pandemic, The Yale Review saw a lot of change. We launched a new website, where we now regularly publish online pieces, along with slideshows by visual artists and audio of our poets reading their poems. Through the ups and downs of these past twelve months, we have felt lucky to be able to publish a host of powerful stories and essays in both our print journal and on our new website.

For your enjoyment over the winter break, we have collected our most-read stories of the year. They include a short story that skewers white progressive hypocrisy around race; a sharp, moving re-reading of the poet John Ashbery; a meditation on the complexities of being a twin; and an essay that interrogates the ways that photography shapes our views of protest and racial violence. We hope you’ll find much on this list to linger with over the coming weeks, and we look forward to bringing you more great writing next year. –The Editors

“ Colonial Conditions ” by Brandon Taylor Taylor’s short story takes place at a Covid-era Halloween party where the protagonist—queer, Black, and raised in rural poverty—finds himself in uneasy conversation with progressive white guests. “ The Wild, Sublime Body " by Melissa Febos Febos recounts how she developed contempt for her body in early puberty but eventually regained the self-love she'd known as a young girl. “ There I Almost Am ” by Jean Garnett This portrayal of being a twin grapples with envy in its many forms. “ Stalking ” by Becca Rothfeld Rothfeld plumbs the depths of social media stalking in an essay about our desire to see without being seen. “ Picturing Catastrophe ” by Rizvana Bradley Bradley argues that photography has historically functioned as an anti-Black medium, and looks at the way that a dominantly white media covered racial protests after George Floyd’s death. “ The Wrong Daddy ” by Jeremy Atherton Lin Lin tells the story of his love for—and then disillusionment with—the musician Morrissey in a reflection on fandom and identity. “ How to Come Back to Life ” by Emily Ogden Ogden considers what it means to reach middle age, lyrically weaving together readings of Ovid’s Orpheus and Eurydice and Federico Fellini’s Le notti di Cabiria . “ The Brink of Destruction ” by Edward Hirsch Hirsch writes a love letter to the poet John Ashbery. “ Olga Tokarczuk's Radical Tenderness ” by Marek Makowski Makowski reflects on Nobel Prize winner Olga Tokarczuk’s genre-defying body of work. “ Going to Lvov ” by Ilya Kaminsky Kaminsky remembers the gentle profundity of the late Adam Zagajewski, who died in 2021, and explains why he was one of the most important poets of our time.

Rachel Cusk

Renaissance women, fady joudah, you might also like, our most-read poems of 2021, our most-read archival pieces of 2021, wood working at the end of the world, the yale review festival 2024.

Join us April 16–19 for readings, panels, and workshops with Hernan Diaz, Katie Kitamura, and many others.

The 10 Best Nonfiction Books of 2021 (So Far)

Our favorite nonfiction of the year encompasses everything from reporting on the global climate crisis to literary essays about motorcycles.

Every product was carefully curated by an Esquire editor. We may earn a commission from these links.

Nothing expands the mind—or the heart—quite like a superb work of nonfiction. But if you hear "nonfiction" and think "dry as a bone," don't get it twisted. Nonfiction doesn't have to feel like homework—in fact, the very best of it can be just as much of a page-turner as a thriller. Our favorite nonfiction of the year encompasses everything from reporting on the global climate crisis to literary essays about motorcycles. This list has true crime, memoirs about identity, and firmament-shattering works that know no boundaries. No matter what your nonfiction niche is, there's something for everyone here. Watch this space for updates, as we'll be expanding our list throughout the year.

Scribner The Hard Crowd, by Rachel Kushner

Kushner’s signature literary sensibility emerges and matures in this two decades-long collection of cultural criticism, literary journalism, and memoir, all of it proof positive of her singular way of seeing. In these nineteen forceful, blistering essays, Kushner turns her lens to everything from Jeff Koons to Denis Johnson, Palestinian refugees to Italian radical politics, classic muscle cars to San Francisco’s indie music scene. And yes, of course, there are motorcycles.

Simon & Schuster Jackpot: How the Super-Rich Really Live―and How Their Wealth Harms Us All, by Michael Mechanic

Have you done your part to rail against capitalism today? If you haven’t, pick up Jackpot , Mechanic’s meticulously reported guide to the opulent world of the ultra-rich, and you’ll be seeing red in no time. Mechanic pulls back the velvet curtain on how our highest earners make, build, and hide their staggering wealth, while also taking aim at the commonly-held fantasy that hitting the jackpot would turn our lives to gold. With palpable glee, Mechanic lays out the lived reality behind the age-old truism that money can’t buy happiness—just ask the bored, miserable, and spiritually bankrupt .01%. Character-driven and far more rollicking fun than it should be, this riveting guide to how the other half lives illuminates how economic inequality leaves everyone worse off.

Harper Perennial An Ordinary Age, by Rainesford Stauffer

All too often, we’re told that young adulthood will be the time of our lives—so why isn’t it? Stauffer explores the diminishing returns of young adulthood in this soulful book, providing a meticulous cartography of how outer forces shape young people’s inner lives. From chronic burnout to the loneliness epidemic to the strictures of social media, An Ordinary Age leads with empathy in exploring the myriad challenges facing young adults, while also advocating for a better path forward: one where young people can live authentic lives filled with love, community, and self-knowledge.

Farrar, Straus and Giroux On Violence and On Violence Against Women, by Jacqueline Rose

No stone goes unturned in Rose’s exhaustive inquiry into the enduring global crisis of sexual violence. Drawing on data and contemporary examples, while also braiding in the work of feminist philosophers like Judith Butler and Hannah Arendt, Rose builds a compellingly argued theory that sexual violence is rooted in male fragility. Rose’s framework examines how systemic power structures reinforce themselves, and how sexual violence intersects with gender, sexuality, race, and class. For anyone looking to educate themselves on this essential subject, start here and now.

Celadon Books Last Call, by Elon Green

In this gripping true crime story about the Last Call Killer, who preyed on New York City’s queer men during the 80s and 90s, Green foregrounds the shamefully forgotten lives of the killer’s known victims. Not only does he consider the profound losses carved out by their murders, but also the role of homophobia in shaping their lives and deaths. Green thoroughly sketches the queer bar scene of the era, ravaged by the AIDS crisis, and the law enforcement indifference that allowed the killer to lure men to their gruesome deaths. In these riveting pages, Green reclaims a time, a place, and a community, weaving together a decades-long forensic investigation with a poignant elegy to murdered men.

Random House A Swim in a Pond in the Rain, by George Saunders

Crown under a white sky, by elizabeth kolbert.

The Pulitzer Prize-winning author of The Sixth Extinction returns with another sobering look at our Anthropocene Epoch, this time centered not on the countless calamities ahead, but on the trailblazing efforts of scientists to turn back the doomsday clock. Kolbert describes the subjects of Under a White Sky as “people trying to solve problems created by people trying to solve problems”; she turns her lens to human interventions in nature, like the storied redirection of the Chicago River, and to the pressing need for further intervention to correct our folly. Traveling everywhere from the Great Lakes to the Great Barrier Reef, she chronicles her encounters with scientists, who are pioneering cutting-edge technologies to turn carbon emissions to stone and shoot diamonds in the stratosphere. Heralded by everyone from Barack Obama to Al Gore, Kolbert’s urgent, deeply researched text asks if our ingenuity can outrun our hubris.

Simon & Schuster Surviving the White Gaze, by Rebecca Carroll

Carroll’s searing memoir recounts her complicated childhood as the only Black person in a rural New Hampshire town, where even the love of her adoptive white parents could not answer the incompleteness within her. When her white birth mother enters the picture to cruelly undermine Carroll’s Blackness and self-worth, the aftershocks reverberate across Carroll’s lifetime, sending her spiraling through a pattern of self-destructive behaviors in search of her racial identity. In this vulnerable and layered meditation on race, adoption, and family, chosen and otherwise, Carroll unspools a poignant story of becoming.

Simon & Schuster We Had a Little Real Estate Problem, by Kliph Nesteroff

Nesteroff traces the long and shameful marginalization of Native American comedians in this deeply researched volume, beginning as early as the 1800s, when Native Americans were forced to perform as caricatures of themselves in traveling Wild West shows in order to avoid imprisonment. The book toggles between historical analysis and modern-day interviews with emerging Native comedians, who are struggling to break into show business amid the dearth of opportunities on reservations. Nesteroff also deconstructs caricatures of Native Americans as stoic people, highlighting an irreverent and often hilarious chorus of voices aching to be heard. Read an exclusive excerpt here at Esquire .

Catapult Craft in the Real World, by Matthew Salesses

In this firmament-shattering examination of how we teach creative writing, Salesses, a novelist and professor, builds a persuasive argument for tearing up the rulebook. Tracing the traditional writing workshop to its roots in white, male cultural values, Salesses challenges received wisdom about the benchmarks of “good” fiction, arguing that we must reimagine how we write and how we teach. Only then will our canon and our classrooms be the inclusive, expansive spaces we want them to be.

@media(max-width: 73.75rem){.css-1ktbcds:before{margin-right:0.4375rem;color:#FF3A30;content:'_';display:inline-block;}}@media(min-width: 64rem){.css-1ktbcds:before{margin-right:0.5625rem;color:#FF3A30;content:'_';display:inline-block;}} Books

Why ‘Carrie’ Is Still Scary as Shit

Holly Gramazio Can Solve Your Dating Burnout

Hanif Abdurraqib Knows What Makes Basketball Great

Percival Everett's New Novel Is a Modern Classic

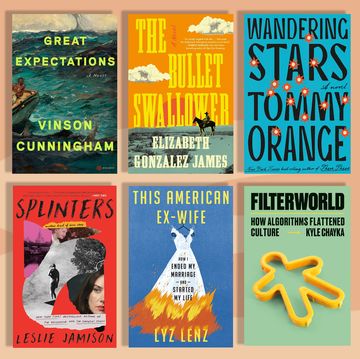

The Best Books of 2024 (So Far)

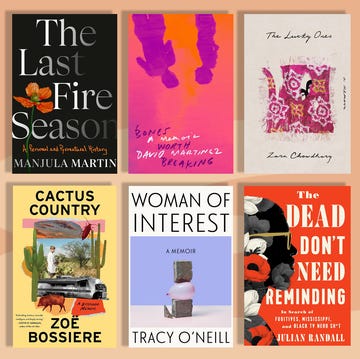

The Best Memoirs of 2024 (So Far)

Is It A Betrayal To Publish Dead Writers' Books?

The Best Sci-Fi Books of 2024 (So Far)

A Crime Fiction Master Flips the Script

How to Read the 'Dune' Book Series in Order

Tommy Orange Is Not Your Tour Guide

50 Must-Read Contemporary Essay Collections

Liberty Hardy

Liberty Hardy is an unrepentant velocireader, writer, bitey mad lady, and tattoo canvas. Turn-ons include books, books and books. Her favorite exclamation is “Holy cats!” Liberty reads more than should be legal, sleeps very little, frequently writes on her belly with Sharpie markers, and when she dies, she’s leaving her body to library science. Until then, she lives with her three cats, Millay, Farrokh, and Zevon, in Maine. She is also right behind you. Just kidding! She’s too busy reading. Twitter: @MissLiberty

View All posts by Liberty Hardy

I feel like essay collections don’t get enough credit. They’re so wonderful! They’re like short story collections, but TRUE. It’s like going to a truth buffet. You can get information about sooooo many topics, sometimes in one single book! To prove that there are a zillion amazing essay collections out there, I compiled 50 great contemporary essay collections, just from the last 18 months alone. Ranging in topics from food, nature, politics, sex, celebrity, and more, there is something here for everyone!

I’ve included a brief description from the publisher with each title. Tell us in the comments about which of these you’ve read or other contemporary essay collections that you love. There are a LOT of them. Yay, books!

Must-Read Contemporary Essay Collections

They can’t kill us until they kill us by hanif abdurraqib.

“In an age of confusion, fear, and loss, Hanif Willis-Abdurraqib’s is a voice that matters. Whether he’s attending a Bruce Springsteen concert the day after visiting Michael Brown’s grave, or discussing public displays of affection at a Carly Rae Jepsen show, he writes with a poignancy and magnetism that resonates profoundly.”

Would Everybody Please Stop?: Reflections on Life and Other Bad Ideas by Jenny Allen

“Jenny Allen’s musings range fluidly from the personal to the philosophical. She writes with the familiarity of someone telling a dinner party anecdote, forgoing decorum for candor and comedy. To read Would Everybody Please Stop? is to experience life with imaginative and incisive humor.”

Longthroat Memoirs: Soups, Sex and Nigerian Taste Buds by Yemisi Aribisala

“A sumptuous menu of essays about Nigerian cuisine, lovingly presented by the nation’s top epicurean writer. As well as a mouth-watering appraisal of Nigerian food, Longthroat Memoirs is a series of love letters to the Nigerian palate. From the cultural history of soup, to fish as aphrodisiac and the sensual allure of snails, Longthroat Memoirs explores the complexities, the meticulousness, and the tactile joy of Nigerian gastronomy.”

Beyond Measure: Essays by Rachel Z. Arndt

“ Beyond Measure is a fascinating exploration of the rituals, routines, metrics and expectations through which we attempt to quantify and ascribe value to our lives. With mordant humor and penetrating intellect, Arndt casts her gaze beyond event-driven narratives to the machinery underlying them: judo competitions measured in weigh-ins and wait times; the significance of the elliptical’s stationary churn; the rote scripts of dating apps; the stupefying sameness of the daily commute.”

Magic Hours by Tom Bissell

“Award-winning essayist Tom Bissell explores the highs and lows of the creative process. He takes us from the set of The Big Bang Theory to the first novel of Ernest Hemingway to the final work of David Foster Wallace; from the films of Werner Herzog to the film of Tommy Wiseau to the editorial meeting in which Paula Fox’s work was relaunched into the world. Originally published in magazines such as The Believer , The New Yorker , and Harper’s , these essays represent ten years of Bissell’s best writing on every aspect of creation—be it Iraq War documentaries or video-game character voices—and will provoke as much thought as they do laughter.”

Dead Girls: Essays on Surviving an American Obsession by Alice Bolin

“In this poignant collection, Alice Bolin examines iconic American works from the essays of Joan Didion and James Baldwin to Twin Peaks , Britney Spears, and Serial , illuminating the widespread obsession with women who are abused, killed, and disenfranchised, and whose bodies (dead and alive) are used as props to bolster men’s stories. Smart and accessible, thoughtful and heartfelt, Bolin investigates the implications of our cultural fixations, and her own role as a consumer and creator.”

Betwixt-and-Between: Essays on the Writing Life by Jenny Boully

“Jenny Boully’s essays are ripe with romance and sensual pleasures, drawing connections between the digression, reflection, imagination, and experience that characterizes falling in love as well as the life of a writer. Literary theory, philosophy, and linguistics rub up against memory, dreamscapes, and fancy, making the practice of writing a metaphor for the illusory nature of experience. Betwixt and Between is, in many ways, simply a book about how to live.”