Clive Wearing (Amnesia Patient)

Imagine waking up every day without remembering anything from your past and then immediately forgetting that you woke up at all. This life without memories is the reality for British musician Clive Wearing who suffers from one of the most severe case of amnesia ever known.

Who is Clive Wearing?

Clive Wearing was born on 11 May 1938. He was an accomplished musicologist, keyboardist, conductor, music producer, and professional tenor at the Westminster Cathedral. When on 27 March 1985 he contracted a virus that attacked his central nervous system resulting in a brain infection, Clive’s life was changed forever.

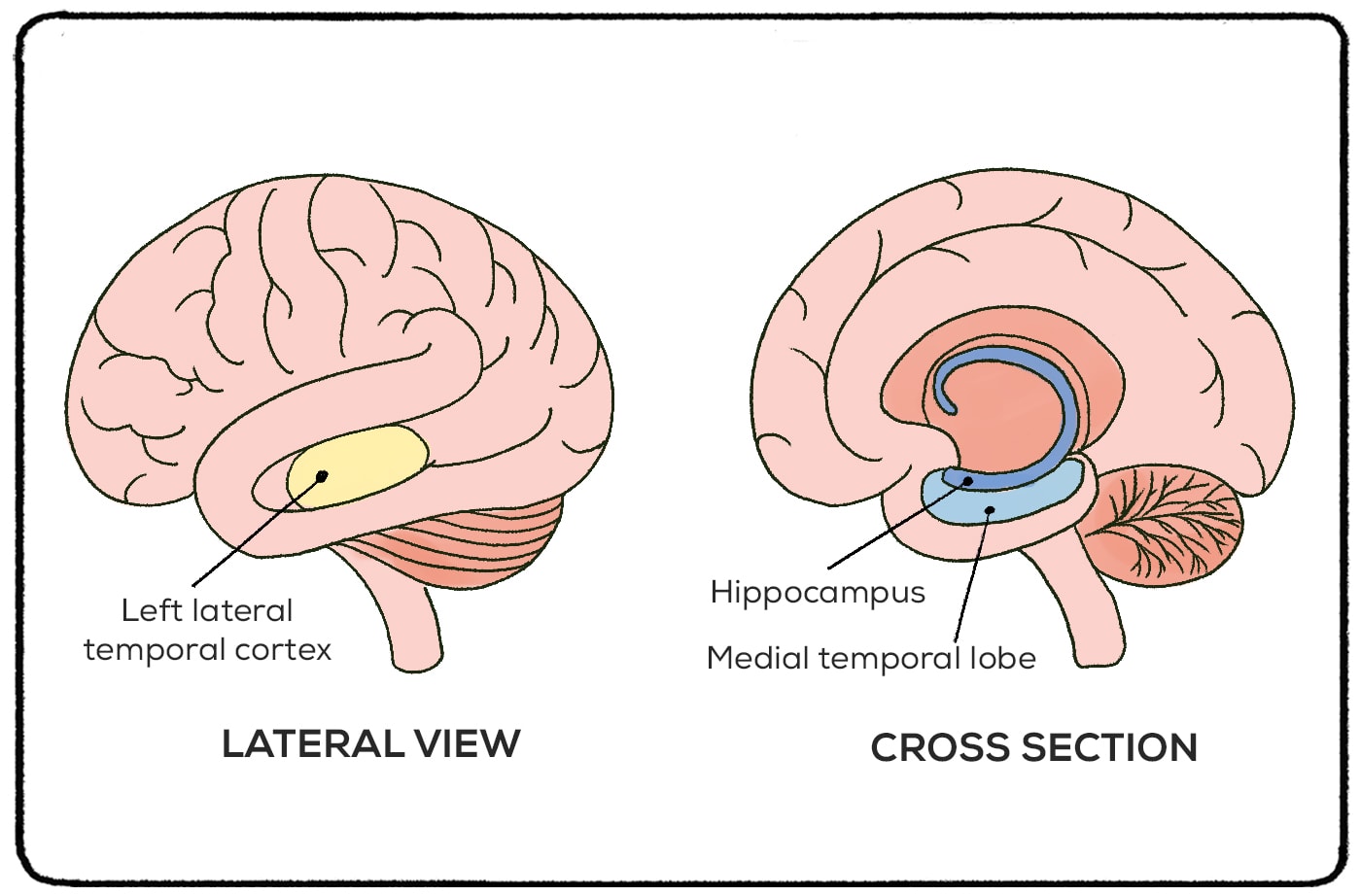

The rare neurological condition called herpes encephalitis caused profound and irreparable damage to Clive’s hippocampus. The hippocampus is a part of the brain that plays an important role in consolidating short-term memory into long-term memory. It is essential for recalling facts and remembering how, where, and when an event happened.

Clive’s hippocampus and medial temporal lobes where it is located were ravaged by the disease. As a consequence, he was left with both anterograde amnesia, the inability to make or keep memories, and retrograde amnesia, the loss of past memories. Most patients suffer one or the other, so it's notable that Clive suffered both.

Clive Wearing and Dual Retrograde-Anterograde Amnesia

Clive’s rare dual retrograde-anterograde amnesia, also known as global or total amnesia, is one of the most extreme cases of memory loss ever recorded. In psychology, the phenomenon is often referred to as "30-second Clive" in reference to Clive Wearing’s case.

Anterograde amnesia

Anterograde amnesia is the loss of the possibility to make new memories after the event that caused the condition, such as an injury or illness. People with anterograde amnesia don’t recall their recent past and are not able to retain any new information. (If you have ever seen the movie 50 First Dates, you might be familiar with this type of condition.)

The duration of Clive’s short-term memory is anywhere between 7 seconds and 30 seconds. He can’t remember what he was doing only a few minutes earlier nor recognize people he had just seen. By the time he gets to the end of a sentence, Clive may have already forgotten what he was talking about. It is impossible for him to watch a movie or read a book since he can’t remember any sentences before the last one.

Because he has no memory of any previous events, Clive constantly thinks that he has just awoken from a coma. In a way, his consciousness is rebooted every 30 seconds. It restarts as soon as the time span of his short-term memory has elapsed.

Retrograde amnesia

Retrograde amnesia is a loss of memory of events that occurred before its onset. Retrograde amnesia is usually gradual and recent memories are more likely to be lost than the older ones .

Due to his severe case of retrograde amnesia, however, Clive doesn’t remember anything that has happened in his entire life. He completely lacks the episodic or autobiographical memory, the memory of his personal experience.

But although he can’t remember them, Clive does know that certain events have occurred in his life. He is aware, for example, that he has children from a previous marriage, even though he doesn’t remember their names or any other detail about them. He knows that he used to be a musician, yet he has no recollection of any part of his career.

Clive also knows that he has a wife. In fact, his second wife Deborah is the only person he recognizes. Whenever Deborah enters the room, Clive greets her with great joy and affection. He has no episodic memories of Deborah, and no memory of their life together. For him, each meeting with her is the first one. But he knows that she is his wife and that he is happy to see her. His memory of emotions associated with Deborah provokes his reactions even in the absence of the episodic memory.

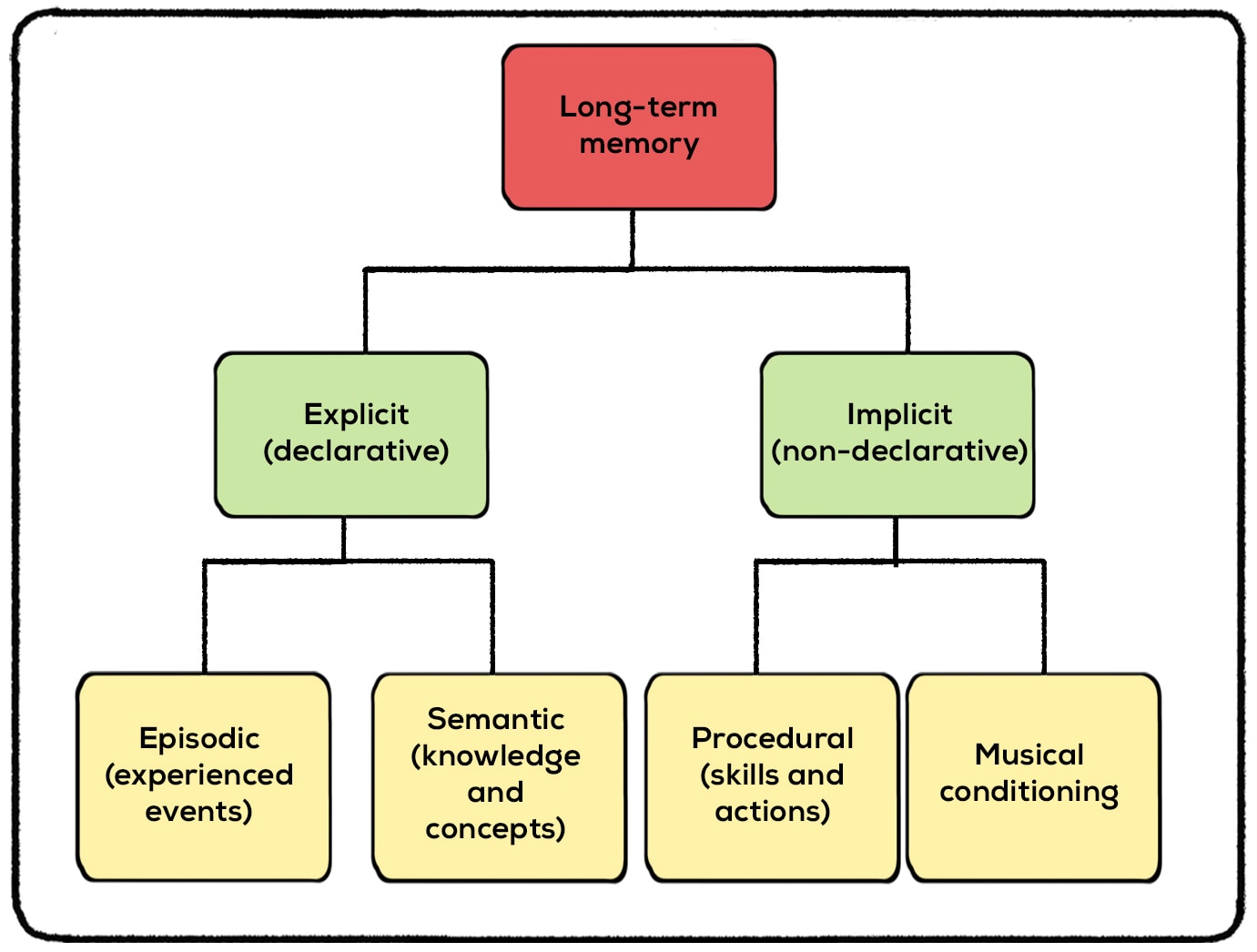

In spite of his complex amnesia, Clive still has some types of memories that remain intact, including semantic and procedural memory.

Clive Wearing’s Semantic and Procedural Memories

Clive Wearing’s example shows that memory is not as simple as we might think. Although the physical location of memory remains largely unknown, scientists believe that different types of memories are stored in neural networks in various parts of the brain.

Semantic memory

Semantic memory is our general factual knowledge, like knowing the capital of France, or the months of the year. Studies show that retrieving episodic and semantic memories activate different areas of the brain. Despite his amnesia, therefore, Clive still has much of his semantic memory and retains his humor and intelligence.

Procedural memory

Clive may not have any episodic memories of his life before the illness, but he has a largely unimpaired procedural memory and some residual learning capacity.

Procedural or muscle memory is remembering how to perform everyday actions like tying shoelaces, writing, or using a knife and fork. People can retain procedural memories even after they have forgotten being taught how to do them. This is why Clive’s procedure memory including language abilities and performing motor tasks that he learned prior to his brain damage are unchanged.

Using procedural memory, Clive can learn new skills and facts through repetition. If he hears a piece of information repeated over and over again, he can eventually retain it although he doesn’t know when or where he had heard it.

While episodic memory is mainly encoded in the hippocampus, the encoding of the procedural memory takes place in different brain areas and in particular the cerebellum, which in Clive’s case has not been damaged.

Musical memory

What’s more, Clive’s musical memory has been perfectly preserved even decades after the onset of his amnesia. In fact, people who suffer from amnesia often have exceptional musical memories. Research shows that these memories are stored in a part of the brain separate from the regions involved in long-term memory.

That’s why Clive is capable of reading music, playing complex piano and organ pieces, and even conducting a choir. But just minutes after the performance, he has no more recollection of ever having played an instrument or having any musical knowledge at all.

Is Clive Wearing Still Alive?

Yes! Clive Wearing is in his early 80s and lives in a residential care facility. Recent reports show that he continues to approve. He renewed his vows with his wife in 2002, and his wife wrote a memoir about her experiences with him.

You can take a look at Clive Wearing's diary entry, as well as access a documentary on him, by checking out this Reddit post .

Not Just Clive Wearing: Other Cases of Amnesia

Clive Wearing is one of the most famous patients with amnesia, but he is far from the only one. Amnesia can affect people temporarily or permanently, and it doesn’t discriminate. Famous authors, former NFL players, and just regular people going to the dentist may deal with a bout of amnesia at one point in their lives. And some of these stories are so stranger than fiction that they are doubted by medical professionals and the general public!

Neuroscientists have been carefully studying amnesia since the 1950s. One of their first notable patients was a man named Henry Molaison, or “H.M.” H.M. suffered amnesia after having surgery at the age of 27. H.M. forgot things almost as soon as they took place. His condition was the subject of studies for decades until he died in 2008. Many scientists still refer to his case when discussing amnesia and other memory disorders.

Scott Bolzan

Imagine waking up one day in the hospital with little to no memories of your life. You’re 47, the woman by your bedside is telling you that you have been married for 25 years. The terms “marriage” and “wife” don’t even register in your brain! As your family tells you about your life, you learn that you spent two years playing in the NFL, have two teenage children, and have decades of memories that just aren’t accessible. This is what happened to Scott Bolzan.

Scott Bolzan developed retrograde amnesia after a simple slip and fall. Little to no blood flow and damaged brain cells in the right temporal lobe erased many of Bolzan’s long-term memories. He knew basic skills, like eating with utensils, but memories of people and events completely disappeared. His case is one of the most severe cases of retrograde amnesia in history, but even his story is doubted by some neurologists. Since his fall, he has written a book about his memory loss and is now a motivational speaker.

Agatha Christie

The story of Agatha Christie’s amnesia is largely buried under her other accomplishments. She’s one of the world’s best-selling authors (only outsold by the Bible and Shakespeare!) Her brain was always in use as she wrote 66 detective novels, but before that, she may have suffered great memory loss. Did she have total amnesia? The jury is actually out on that. I’ll explain why.

Christie found out that her husband was cheating on her shortly after the death of Christie’s mother. The stress was tough for Christie to handle, so it’s not surprising that she fled home after an argument with her husband. Her car turned up in a ditch, and after 11 days of searching, she was found at a hotel. Christie had checked into the hotel using the same name as the “other woman” in her husband’s affair.

Upon discovering Christie, her husband reported that she was suffering from amnesia and had no idea who she was. Two doctors confirmed the diagnosis, but it did not debilitate her for life, like Clive Wearing. This alleged bout with amnesia happened in 1926, years before she wrote the genius novels that we still know today. Some sources are not sure whether she suffered amnesia, was faking the condition to seek revenge on her husband or was simply experiencing a dissociative state after traumatic events. It would not be completely unusual if she did experience memory loss while staying in that hotel. Dissociative amnesia can affect anyone who has been through trauma or extreme levels of stress.

One patient, identified only as “ WO ,” started living the life of Drew Barrymore’s character in 50 First Dates after a…root canal? While anterograde amnesia was the result of a car crash in the popular movie, other types of trauma or events can bring on this condition. For WO, it was a routine root canal. Nothing dramatic happened during the procedure. Nothing dramatic took place in WO’s brain after they went home. And yet, the patient wakes up every day believing it is March 14, 2005. They were 38 years old at the time of the root canal.

Every day, the patient must wake up and remind themselves that it is not 2005, but much later. An electronic journal keeps them up to date with their life and the events of the past years. Although the cause behind their amnesia is truly baffling, it goes to show that our brains can be fragile and there is still a lot to learn about them!

Related posts:

- Long Term Memory

- Semantic Memory (Definition + Examples + Pics)

- Memory (Types + Models + Overview)

- Short Term Memory

- Declarative Memory (Definition + Examples)

Reference this article:

About The Author

Free Personality Test

Free Memory Test

Free IQ Test

PracticalPie.com is a participant in the Amazon Associates Program. As an Amazon Associate we earn from qualifying purchases.

Follow Us On:

Youtube Facebook Instagram X/Twitter

Psychology Resources

Developmental

Personality

Relationships

Psychologists

Serial Killers

Psychology Tests

Personality Quiz

Memory Test

Depression test

Type A/B Personality Test

© PracticalPsychology. All rights reserved

Privacy Policy | Terms of Use

Find anything you save across the site in your account

By Oliver Sacks

In March of 1985, Clive Wearing, an eminent English musician and musicologist in his mid-forties, was struck by a brain infection—a herpes encephalitis—affecting especially the parts of his brain concerned with memory. He was left with a memory span of only seconds—the most devastating case of amnesia ever recorded. New events and experiences were effaced almost instantly. As his wife, Deborah, wrote in her 2005 memoir, “Forever Today”:

His ability to perceive what he saw and heard was unimpaired. But he did not seem to be able to retain any impression of anything for more than a blink. Indeed, if he did blink, his eyelids parted to reveal a new scene. The view before the blink was utterly forgotten. Each blink, each glance away and back, brought him an entirely new view. I tried to imagine how it was for him. . . . Something akin to a film with bad continuity, the glass half empty, then full, the cigarette suddenly longer, the actor’s hair now tousled, now smooth. But this was real life, a room changing in ways that were physically impossible.

In addition to this inability to preserve new memories, Clive had a retrograde amnesia, a deletion of virtually his entire past.

When he was filmed in 1986 for Jonathan Miller’s extraordinary documentary “Prisoner of Consciousness,” Clive showed a desperate aloneness, fear, and bewilderment. He was acutely, continually, agonizingly conscious that something bizarre, something awful, was the matter. His constantly repeated complaint, however, was not of a faulty memory but of being deprived, in some uncanny and terrible way, of all experience, deprived of consciousness and life itself. As Deborah wrote:

It was as if every waking moment was the first waking moment. Clive was under the constant impression that he had just emerged from unconsciousness because he had no evidence in his own mind of ever being awake before. . . . “I haven’t heard anything, seen anything, touched anything, smelled anything,” he would say. “It’s like being dead.”

Desperate to hold on to something, to gain some purchase, Clive started to keep a journal, first on scraps of paper, then in a notebook. But his journal entries consisted, essentially, of the statements “I am awake” or “I am conscious,” entered again and again every few minutes. He would write: “2:10 P.M : This time properly awake. . . . 2:14 P.M : this time finally awake. . . . 2:35 P.M : this time completely awake,” along with negations of these statements: “At 9:40 P.M. I awoke for the first time, despite my previous claims.” This in turn was crossed out, followed by “I was fully conscious at 10:35 P.M. , and awake for the first time in many, many weeks.” This in turn was cancelled out by the next entry.

This dreadful journal, almost void of any other content but these passionate assertions and denials, intending to affirm existence and continuity but forever contradicting them, was filled anew each day, and soon mounted to hundreds of almost identical pages. It was a terrifying and poignant testament to Clive’s mental state, his lostness, in the years that followed his amnesia—a state that Deborah, in Miller’s film, called “a never-ending agony.”

Another profoundly amnesic patient I knew some years ago dealt with his abysses of amnesia by fluent confabulations. He was wholly immersed in his quick-fire inventions and had no insight into what was happening; so far as he was concerned, there was nothing the matter. He would confidently identify or misidentify me as a friend of his, a customer in his delicatessen, a kosher butcher, another doctor—as a dozen different people in the course of a few minutes. This sort of confabulation was not one of conscious fabrication. It was, rather, a strategy, a desperate attempt—unconscious and almost automatic—to provide a sort of continuity, a narrative continuity, when memory, and thus experience, was being snatched away every instant.

Though one cannot have direct knowledge of one’s own amnesia, there may be ways to infer it: from the expressions on people’s faces when one has repeated something half a dozen times; when one looks down at one’s coffee cup and finds that it is empty; when one looks at one’s diary and sees entries in one’s own handwriting. Lacking memory, lacking direct experiential knowledge, amnesiacs have to make hypotheses and inferences, and they usually make plausible ones. They can infer that they have been doing something, been somewhere , even though they cannot recollect what or where. Yet Clive, rather than making plausible guesses, always came to the conclusion that he had just been “awakened,” that he had been “dead.” This seemed to me a reflection of the almost instantaneous effacement of perception for Clive—thought itself was almost impossible within this tiny window of time. Indeed, Clive once said to Deborah, “I am completely incapable of thinking.” At the beginning of his illness, Clive would sometimes be confounded at the bizarre things he experienced. Deborah wrote of how, coming in one day, she saw him

holding something in the palm of one hand, and repeatedly covering and uncovering it with the other hand as if he were a magician practising a disappearing trick. He was holding a chocolate. He could feel the chocolate unmoving in his left palm, and yet every time he lifted his hand he told me it revealed a brand new chocolate. “Look!” he said. “It’s new!” He couldn’t take his eyes off it. “It’s the same chocolate,” I said gently. “No . . . look! It’s changed. It wasn’t like that before . . .” He covered and uncovered the chocolate every couple of seconds, lifting and looking. “Look! It’s different again! How do they do it?”

Within months, Clive’s confusion gave way to the agony, the desperation, that is so clear in Miller’s film. This, in turn, was succeeded by a deep depression, as it came to him—if only in sudden, intense, and immediately forgotten moments—that his former life was over, that he was incorrigibly disabled.

As the months passed without any real improvement, the hope of significant recovery became fainter and fainter, and toward the end of 1985 Clive was moved to a room in a chronic psychiatric unit—a room he was to occupy for the next six and a half years but which he was never able to recognize as his own. A young psychologist saw Clive for a period of time in 1990 and kept a verbatim record of everything he said, and this caught the grim mood that had taken hold. Clive said at one point, “Can you imagine one night five years long? No dreaming, no waking, no touch, no taste, no smell, no sight, no sound, no hearing, nothing at all. It’s like being dead. I came to the conclusion that I was dead.”

The only times of feeling alive were when Deborah visited him. But the moment she left, he was desperate once again, and by the time she got home, ten or fifteen minutes later, she would find repeated messages from him on her answering machine: “Please come and see me, darling—it’s been ages since I’ve seen you. Please fly here at the speed of light.”

To imagine the future was no more possible for Clive than to remember the past—both were engulfed by the onslaught of amnesia. Yet, at some level, Clive could not be unaware of the sort of place he was in, and the likelihood that he would spend the rest of his life, his endless night, in such a place.

But then, seven years after his illness, after huge efforts by Deborah, Clive was moved to a small country residence for the brain-injured, much more congenial than a hospital. Here he was one of only a handful of patients, and in constant contact with a dedicated staff who treated him as an individual and respected his intelligence and talents. He was taken off most of his heavy tranquillizers, and seemed to enjoy his walks around the village and gardens near the home, the spaciousness, the fresh food.

For the first eight or nine years in this new home, Deborah told me, “Clive was calmer and sometimes jolly, a bit more content, but often with angry outbursts still, unpredictable, withdrawn, spending most of his time in his room alone.” But gradually, in the past six or seven years, Clive has become more sociable, more talkative. Conversation (though of a “scripted” sort) has come to fill what had been empty, solitary, and desperate days.

Though I had corresponded with Deborah since Clive first became ill, twenty years went by before I met Clive in person. He was so changed from the haunted, agonized man I had seen in Miller’s 1986 film that I was scarcely prepared for the dapper, bubbling figure who opened the door when Deborah and I went to visit him in the summer of 2005. He had been reminded of our visit just before we arrived, and he flung his arms around Deborah the moment she entered.

Deborah introduced me: “This is Dr. Sacks.” And Clive immediately said, “You doctors work twenty-four hours a day, don’t you? You’re always in demand.” We went up to his room, which contained an electric organ console and a piano piled high with music. Some of the scores, I noted, were transcriptions of Orlandus Lassus, the Renaissance composer whose works Clive had edited. I saw Clive’s journal by the washstand—he has now filled up scores of volumes, and the current one is always kept in this exact location. Next to it was an etymological dictionary with dozens of reference slips of different colors stuck between the pages and a large, handsome volume, “The 100 Most Beautiful Cathedrals in the World.” A Canaletto print hung on the wall, and I asked Clive if he had ever been to Venice. No, he said. (Deborah told me they had visited several times before his illness.) Looking at the print, Clive pointed out the dome of a church: “Look at it,” he said. “See how it soars—like an angel!”

When I asked Deborah whether Clive knew about her memoir, she told me that she had shown it to him twice before, but that he had instantly forgotten. I had my own heavily annotated copy with me, and asked Deborah to show it to him again.

“You’ve written a book!” he cried, astonished. “Well done! Congratulations!” He peered at the cover. “All by you? Good heavens!” Excited, he jumped for joy. Deborah showed him the dedication page: “For my Clive.” “Dedicated to me?” He hugged her. This scene was repeated several times within a few minutes, with almost exactly the same astonishment, the same expressions of delight and joy each time.

Clive and Deborah are still very much in love with each other, despite his amnesia. (Indeed, Deborah’s book is subtitled “A Memoir of Love and Amnesia.”) He greeted her several times as if she had just arrived. It must be an extraordinary situation, I thought, both maddening and flattering, to be seen always as new, as a gift, a blessing.

Clive had, in the meantime, addressed me as “Your Highness” and inquired at intervals, “Been at Buckingham Palace? . . . Are you the Prime Minister? . . . Are you from the U.N.?” He laughed when I answered, “Just the U.S.” This joking or jesting was of a somewhat waggish, stereotyped nature and highly repetitive. Clive had no idea who I was, little idea who anyone was, but this bonhomie allowed him to make contact, to keep a conversation going. I suspected he had some damage to his frontal lobes, too—such jokiness (neurologists speak of Witzelsucht, joking disease), like his impulsiveness and chattiness, could go with a weakening of the usual social frontal-lobe inhibitions.

He was excited at the notion of going out for lunch—lunch with Deborah. “Isn’t she a wonderful woman?” he kept asking me. “Doesn’t she have marvellous kisses?” I said yes, I was sure she had.

As we drove to the restaurant, Clive, with great speed and fluency, invented words for the letters on the license plates of passing cars: “JCK” was Japanese Clever Kid; “NKR” was New King of Russia; and “BDH” (Deborah’s car) was British Daft Hospital, then Blessed Dutch Hospital. “Forever Today,” Deborah’s book, immediately became “Three-Ever Today,” “Two-Ever Today,” “One-Ever Today.” This incontinent punning and rhyming and clanging was virtually instantaneous, occurring with a speed no normal person could match. It resembled Tourettic or savantlike speed, the speed of the preconscious, undelayed by reflection.

When we arrived at the restaurant, Clive did all the license plates in the parking lot and then, elaborately, with a bow and a flourish, let Deborah enter: “Ladies first!” He looked at me with some uncertainty as I followed them to the table: “Are you joining us, too?”

When I offered him the wine list, he looked it over and exclaimed, “Good God! Australian wine! New Zealand wine! The colonies are producing something original—how exciting!” This partly indicated his retrograde amnesia—he is still in the nineteen-sixties (if he is anywhere), when Australian and New Zealand wines were almost unheard of in England. “The colonies,” however, was part of his compulsive waggery and parody.

At lunch he talked about Cambridge—he had been at Clare College, but had often gone next door to King’s, for its famous choir. He spoke of how after Cambridge, in 1968, he joined the London Sinfonietta, where they played modern music, though he was already attracted to the Renaissance and Lassus. He was the chorus master there, and he reminisced about how the singers could not talk during coffee breaks; they had to save their voices (“It was often misunderstood by the instrumentalists, seemed standoffish to them”). These all sounded like genuine memories. But they could equally have reflected his knowing about these events, rather than actual memories of them—expressions of “semantic” memory rather than “event” or “episodic” memory. Then he spoke of the Second World War (he was born in 1938) and how his family would go to bomb shelters and play chess or cards there. He said that he remembered the doodlebugs: “There were more bombs in Birmingham than in London.” Was it possible that these were genuine memories? He would have been only six or seven, at most. Or was he confabulating or simply, as we all do, repeating stories he had been told as a child?

At one point, he talked about pollution and how dirty petrol engines were. When I told him I had a hybrid with an electric motor as well as a combustion engine, he was astounded, as if something he had read about as a theoretical possibility had, far sooner than he had imagined, become a reality.

In her remarkable book, so tender yet so tough-minded and realistic, Deborah wrote about the change that had so struck me: that Clive was now “garrulous and outgoing . . . could talk the hind legs off a donkey.” There were certain themes he tended to stick to, she said, favorite subjects (electricity, the Tube, stars and planets, Queen Victoria, words and etymologies), which would all be brought up again and again:

“Have they found life on Mars yet?” “No, darling, but they think there might have been water . . .” “Really? Isn’t it amazing that the sun goes on burning? Where does it get all that fuel? It doesn’t get any smaller. And it doesn’t move. We move round the sun. How can it keep on burning for millions of years? And the Earth stays the same temperature. It’s so finely balanced.” “They say it’s getting warmer now, love. They call it global warming.” “No! Why’s that?” “Because of the pollution. We’ve been emitting gases into the atmosphere. And puncturing the ozone layer.” “ OH NO ! That could be disastrous!” “People are already getting more cancers.” “Oh, aren’t people stupid! Do you know the average IQ is only 100? That’s terribly low, isn’t it? One hundred. It’s no wonder the world’s in such a mess.” Clive’s scripts were repeated with great frequency, sometimes three or four times in one phone call. He stuck to subjects he felt he knew something about, where he would be on safe ground, even if here and there something apocryphal crept in. . . . These small areas of repartee acted as stepping stones on which he could move through the present. They enabled him to engage with others.

I would put it even more strongly and use a phrase that Deborah used in another connection, when she wrote of Clive being poised upon “a tiny platform . . . above the abyss.” Clive’s loquacity, his almost compulsive need to talk and keep conversations going, served to maintain a precarious platform, and when he came to a stop the abyss was there, waiting to engulf him. This, indeed, is what happened when we went to a supermarket and he and I got separated briefly from Deborah. He suddenly exclaimed, “I’m conscious now . . . . Never saw a human being before . . . for thirty years . . . . It’s like death!” He looked very angry and distressed. Deborah said the staff calls these grim monologues his “deads”—they make a note of how many he has in a day or a week and gauge his state of mind by their number.

Deborah thinks that repetition has slightly dulled the very real pain that goes with this agonized but stereotyped complaint, but when he says such things she will distract him immediately. Once she has done this, there seems to be no lingering mood—an advantage of his amnesia. And, indeed, once we returned to the car Clive was off on his license plates again.

Back in his room, I spotted the two volumes of Bach’s “Forty-eight Preludes and Fugues” on top of the piano and asked Clive if he would play one of them. He said that he had never played any of them before, but then he began to play Prelude 9 in E Major and said, “I remember this one.” He remembers almost nothing unless he is actually doing it; then it may come to him. He inserted a tiny, charming improvisation at one point, and did a sort of Chico Marx ending, with a huge downward scale. With his great musicality and his playfulness, he can easily improvise, joke, play with any piece of music.

His eye fell on the book about cathedrals, and he talked about cathedral bells—did I know how many combinations there could be with eight bells? “Eight by seven by six by five by four by three by two by one,” he rattled off. “Factorial eight.” And then, without pause: “That’s forty thousand.” (I worked it out, laboriously: it is 40,320.)

I asked him about Prime Ministers. Tony Blair? Never heard of him. John Major? No. Margaret Thatcher? Vaguely familiar. Harold Macmillan, Harold Wilson: ditto. (But earlier in the day he had seen a car with “JMV” plates and instantly said, “John Major Vehicle”—showing that he had an implicit memory of Major’s name.) Deborah wrote of how he could not remember her name, “but one day someone asked him to say his full name, and he said, ‘Clive David Deborah Wearing—funny name that. I don’t know why my parents called me that.’ ” He has gained other implicit memories, too, slowly picking up new knowledge, like the layout of his residence. He can go alone now to the bathroom, the dining room, the kitchen—but if he stops and thinks en route he is lost. Though he could not describe his residence, Deborah tells me that he unclasps his seat belt as they draw near and offers to get out and open the gate. Later, when he makes her coffee, he knows where the cups, the milk, and the sugar are kept. He cannot say where they are, but he can go to them; he has actions, but few facts, at his disposal.

I decided to widen the testing and asked Clive to tell me the names of all the composers he knew. He said, “Handel, Bach, Beethoven, Berg, Mozart, Lassus.” That was it. Deborah told me that at first, when asked this question, he would omit Lassus, his favorite composer. This seemed appalling for someone who had been not only a musician but an encyclopedic musicologist. Perhaps it reflected the shortness of his attention span and recent immediate memory—perhaps he thought that he had in fact given us dozens of names. So I asked him other questions on a variety of topics that he would have been knowledgeable about in his earlier days. Again, there was a paucity of information in his replies and sometimes something close to a blank. I started to feel that I had been beguiled, in a sense, by Clive’s easy, nonchalant, fluent conversation into thinking that he still had a great deal of general information at his disposal, despite the loss of memory for events. Given his intelligence, ingenuity, and humor, it was easy to think this on meeting him for the first time. But repeated conversations rapidly exposed the limits of his knowledge. It was indeed as Deborah wrote in her book, Clive “stuck to subjects he knew something about” and used these islands of knowledge as “stepping stones” in his conversation. Clearly, Clive’s general knowledge, or semantic memory, was greatly affected, too—though not as catastrophically as his episodic memory.

Yet semantic memory of this sort, even if completely intact, is not of much use in the absence of explicit, episodic memory. Clive is safe enough in the confines of his residence, for instance, but he would be hopelessly lost if he were to go out alone. Lawrence Weiskrantz comments on the need for both sorts of memory in his 1997 book “Consciousness Lost and Found”:

The amnesic patient can think about material in the immediate present. . . . He can also think about items in his semantic memory, his general knowledge. . . . But thinking for successful everyday adaptation requires not only factual knowledge, but the ability to recall it on the right occasion, to relate it to other occasions, indeed the ability to reminisce.

This uselessness of semantic memory unaccompanied by episodic memory is also brought out by Umberto Eco in his novel “The Mysterious Flame of Queen Loana,” in which the narrator, an antiquarian bookseller and polymath, is a man of Eco-like intelligence and erudition. Though amnesic from a stroke, he retains the poetry he has read, the many languages he knows, his encyclopedic memory of facts; but he is nonetheless helpless and disoriented (and recovers from this only because the effects of his stroke are transient).

It is similar, in a way, with Clive. His semantic memory, while of little help in organizing his life, does have a crucial social role: it allows him to engage in conversation (though it is occasionally more monologue than conversation). Thus, Deborah wrote, “he would string all his subjects together in a row, and the other person simply needed to nod or mumble.” By moving rapidly from one thought to another, Clive managed to secure a sort of continuity, to hold the thread of consciousness and attention intact—albeit precariously, for the thoughts were held together, on the whole, by superficial associations. Clive’s verbosity made him a little odd, a little too much at times, but it was highly adaptive—it enabled him to reënter the world of human discourse.

In the 1986 film, Deborah quoted Proust’s description of Swann waking from a deep sleep, not knowing at first where he was, who he was, what he was. He had only “the most rudimentary sense of existence, such as may lurk and flicker in the depths of an animal’s consciousness,” until memory came back to him, “like a rope let down from heaven to draw me up out of the abyss of not-being, from which I could never have escaped by myself.” This gave him back his personal consciousness and identity. No rope from Heaven, no autobiographical memory will ever come down in this way to Clive. F rom the start there have been, for Clive, two realities of immense importance. The first of these is Deborah, whose presence and love for him have made life tolerable, at least intermittently, in the twenty or more years since his illness. Clive’s amnesia not only destroyed his ability to retain new memories; it deleted almost all of his earlier memories, including those of the years when he met and fell in love with Deborah. He told Deborah, when she questioned him, that he had never heard of John Lennon or John F. Kennedy. Though he always recognized his own children, Deborah told me, “he would be surprised at their height and amazed to hear he is a grandfather. He asked his younger son what O-level exams he was doing in 2005, more than twenty years after Edmund left school.” Yet somehow he always recognized Deborah as his wife, when she visited, and felt moored by her presence, lost without her. He would rush to the door when he heard her voice, and embrace her with passionate, desperate fervor. Having no idea how long she had been away—since anything not in his immediate field of perception and attention would be lost, forgotten, within seconds—he seemed to feel that she, too, had been lost in the abyss of time, and so her “return” from the abyss seemed nothing short of miraculous. As Deborah put it:

Clive was constantly surrounded by strangers in a strange place, with no knowledge of where he was or what had happened to him. To catch sight of me was always a massive relief—to know that he was not alone, that I still cared, that I loved him, that I was there. Clive was terrified all the time. But I was his life, I was his lifeline. Every time he saw me, he would run to me, fall on me, sobbing, clinging.

How, why, when he recognized no one else with any consistency, did Clive recognize Deborah? There are clearly many sorts of memory, and emotional memory is one of the deepest and least understood.

The neuroscientist Neal J. Cohen recounts the famous story of Édouard Claparède, a Swiss physician who, upon shaking hands with a severely amnesic woman,

pricked her finger with a pin hidden in his hand. Subsequently, whenever he again attempted to shake the patient’s hand, she promptly withdrew it. When he questioned her about this behavior, she replied, “Isn’t it allowed to withdraw one’s hand?” and “Perhaps there is a pin hidden in your hand,” and finally, “Sometimes pins are hidden in hands.” Thus the patient learned the appropriate response based on previous experience, but she never seemed to attribute her behavior to the personal memory of some previously experienced event.

For Claparède’s patient, some sort of memory of the pain, an implicit and emotional memory, persisted. It seems certain, likewise, that in the first two years of life, even though one retains no explicit memories (Freud called this infantile amnesia), deep emotional memories or associations are nevertheless being made in the limbic system and other regions of the brain where emotions are represented—and these emotional memories may determine one’s behavior for a lifetime. A recent paper by Oliver Turnbull, Evangelos Zois, et al., in the journal Neuro-Psychoanalysis, has shown that patients with amnesia can form emotional transferences to an analyst, even though they retain no explicit memory of the analyst or their previous meetings. Nonetheless, a strong emotional bond begins to develop. Clive and Deborah were newly married at the time of his encephalitis, and deeply in love for a few years before that. His passionate relationship with her, a relationship that began before his encephalitis, and one that centers in part on their shared love for music, has engraved itself in him—in areas of his brain unaffected by the encephalitis—so deeply that his amnesia, the most severe amnesia ever recorded, cannot eradicate it.

Nonetheless, for many years he failed to recognize Deborah if she chanced to walk past, and even now he cannot say what she looks like unless he is actually looking at her. Her appearance, her voice, her scent, the way they behave with each other, and the intensity of their emotions and interactions—all this confirms her identity, and his own.

The other miracle was the discovery Deborah made early on, while Clive was still in the hospital, desperately confused and disoriented: that his musical powers were totally intact. “I picked up some music,” Deborah wrote,

and held it open for Clive to see. I started to sing one of the lines. He picked up the tenor lines and sang with me. A bar or so in, I suddenly realized what was happening. He could still read music. He was singing. His talk might be a jumble no one could understand but his brain was still capable of music. . . . When he got to the end of the line I hugged him and kissed him all over his face. . . . Clive could sit down at the organ and play with both hands on the keyboard, changing stops, and with his feet on the pedals, as if this were easier than riding a bicycle. Suddenly we had a place to be together, where we could create our own world away from the ward. Our friends came in to sing. I left a pile of music by the bed and visitors brought other pieces.

Miller’s film showed dramatically the virtually perfect preservation of Clive’s musical powers and memory. In these scenes from only a year or so after his illness, his face often appeared tight with torment and bewilderment. But when he was conducting his old choir, he performed with great sensitivity and grace, mouthing the melodies, turning to different singers and sections of the choir, cuing them, encouraging them, to bring out their special parts. It is obvious that Clive not only knew the piece intimately—how all the parts contributed to the unfolding of the musical thought—but also retained all the skills of conducting, his professional persona, and his own unique style.

Clive cannot retain any memory of passing events or experience and, in addition, has lost most of the memories of events and experiences preceding his encephalitis—how, then, does he retain his remarkable knowledge of music, his ability to sight-read, play the piano and organ, sing, and conduct a choir in the masterly way he did before he became ill?

H.M., a famous and unfortunate patient described by Scoville and Milner in 1957, was rendered amnesic by the surgical removal of both hippocampi, along with adjacent structures of the medial temporal lobes. (This was a desperate attempt at treating his intractable seizures; it was not yet realized that autobiographical memory and the ability to form new memories of events depended on these structures.) Yet H.M., though he lost many memories of his former life, did not lose any of the skills he had acquired, and indeed he could learn and perfect new skills with training and practice, even though he would retain no memory of the practice sessions.

Larry Squire, a neuroscientist who has spent a lifetime exploring mechanisms of memory and amnesia, emphasizes that no two cases of amnesia are the same. He wrote to me:

If the damage is limited to the medial temporal lobe, then one expects an impairment such as H.M. had. With somewhat more extensive medial temporal lobe damage, one can expect something more severe, as in E.P. [a patient whom Squire and his colleagues have investigated intensively]. With the addition of frontal damage, perhaps one begins to understand Clive’s impairment. Or perhaps one needs lateral temporal damage as well, or basal forebrain damage. Clive’s case is unique, because a particular pattern of anatomical damage occurred. His case is not like H.M. or like Claparède’s patient. We cannot write about amnesia as if it were a single entity like mumps or measles.

Yet H.M.’s case and subsequent work made it clear that two very different sorts of memory could exist: a conscious memory of events (episodic memory) and an unconscious memory for procedures—and that such procedural memory is unimpaired in amnesia.

This is dramatically clear with Clive, too, for he can shave, shower, look after his grooming, and dress elegantly, with taste and style; he moves confidently and is fond of dancing. He talks abundantly, using a large vocabulary; he can read and write in several languages. He is good at calculation. He can make phone calls, and he can find the coffee things and find his way about the home. If he is asked how to do these things, he cannot say, but he does them. Whatever involves a sequence or pattern of action, he does fluently, unhesitatingly.

But can Clive’s beautiful playing and singing, his masterly conducting, his powers of improvisation be adequately characterized as “skills” or “procedures”? For his playing is infused with intelligence and feeling, with a sensitive attunement to the musical structure, the composer’s style and mind. Can any artistic or creative performance of this calibre be adequately explained by “procedural memory”? Episodic or explicit memory, we know, develops relatively late in childhood and is dependent on a complex brain system involving the hippocampi and medial temporal-lobe structures, the system that is compromised in severe amnesiacs and all but obliterated in Clive. The basis of procedural or implicit memory is less easy to define, but it certainly involves larger and more primitive parts of the brain—subcortical structures like the basal ganglia and cerebellum and their many connections to each other and to the cerebral cortex. The size and variety of these systems guarantee the robustness of procedural memory and the fact that, unlike episodic memory, procedural memory can remain largely intact even in the face of extensive damage to the hippocampi and medial temporal-lobe structures.

Episodic memory depends on the perception of particular and often unique events, and one’s memories of such events, like one’s original perception of them, are not only highly individual (colored by one’s interests, concerns, and values) but prone to be revised or recategorized every time they are recalled. This is in fundamental contrast to procedural memory, where it is all-important that the remembering be literal, exact, and reproducible. Repetition and rehearsal, timing and sequence are of the essence here. Rodolfo Llinás, the neuroscientist, uses the term “fixed action pattern” ( FAP ) for such procedural memories. Some of these may be present even before birth (fetal horses, for example, may gallop in the womb). Much of the early motor development of the child depends on learning and refining such procedures, through play, imitation, trial and error, and incessant rehearsal. All of these start to develop long before the child can call on any explicit or episodic memories.

Is the concept of fixed action patterns any more illuminating than that of procedural memories in relation to the enormously complex, creative performances of a professional musician? In his book “I of the Vortex,” Llinás writes:

When a soloist such as Heifetz plays with a symphony orchestra accompanying him, by convention the concerto is played purely from memory. Such playing implies that this highly specific motor pattern is stored somewhere and subsequently released at the time the curtain goes up.

But for a performer, Llinás writes, it is not sufficient to have implicit memory only; one must have explicit memory as well:

Without intact explicit memory, Jascha Heifetz would not remember from day to day which piece he had chosen to work on previously, or that he had ever worked on that piece before. Nor would he recall what he had accomplished the day before or by analysis of past experience what particular problems in execution should be a focus of today’s practice session. In fact, it would not occur to him to have a practice session at all; without close direction from someone else he would be effectively incapable of undertaking the process of learning any new piece, irrespective of his considerable technical skills.

This, too, is very much the case with Clive, who, for all his musical powers, needs “close direction” from others. He needs someone to put the music before him, to get him into action, and to make sure that he learns and practices new pieces.

What is the relationship of action patterns and procedural memories, which are associated with relatively primitive portions of the nervous system, to consciousness and sensibility, which depend on the cerebral cortex? Practice involves conscious application, monitoring what one is doing, bringing all one’s intelligence and sensibility and values to bear—even though what is so painfully and consciously acquired may then become automatic, coded in motor patterns at a subcortical level. Each time Clive sings or plays the piano or conducts a choir, automatism comes to his aid. But what happens in an artistic or creative performance, though it depends on automatisms, is anything but automatic. The actual performance reanimates him, engages him as a creative person; it becomes fresh and perhaps contains new improvisations or innovations. Once Clive starts playing, his “momentum,” as Deborah writes, will keep him, and the piece, going. Deborah, herself a musician, expresses this very precisely:

The momentum of the music carried Clive from bar to bar. Within the structure of the piece, he was held, as if the staves were tramlines and there was only one way to go. He knew exactly where he was because in every phrase there is context implied, by rhythm, key, melody. It was marvellous to be free. When the music stopped Clive fell through to the lost place. But for those moments he was playing he seemed normal.

Clive’s performance self seems, to those who know him, just as vivid and complete as it was before his illness. This mode of being, this self, is seemingly untouched by his amnesia, even though his autobiographical self, the self that depends on explicit, episodic memories, is virtually lost. The rope that is let down from Heaven for Clive comes not with recalling the past, as for Proust, but with performance—and it holds only as long as the performance lasts. Without performance, the thread is broken, and he is thrown back once again into the abyss.

Deborah speaks of the “momentum” of the music in its very structure. A piece of music is not a mere sequence of notes but a tightly organized organic whole. Every bar, every phrase arises organically from what preceded it and points to what will follow. Dynamism is built into the nature of melody. And over and above this there is the intentionality of the composer, the style, the order, and the logic that he has created to express his musical ideas and feelings. These, too, are present in every bar and phrase. Schopenhauer wrote of melody as having “significant intentional connection from beginning to end” and as “one thought from beginning to end.” Marvin Minsky compares a sonata to a teacher or a lesson:

No one remembers, word for word, all that was said in any lecture, or played in any piece. But if you understood it once, you now own new networks of knowledge, about each theme and how it changes and relates to others. Thus, no one could remember Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony entire, from a single hearing. But neither could one ever hear again those first four notes as just four notes! Once but a tiny scrap of sound; it is now a Known Thing—a locus in the web of all the other things we know, whose meanings and significances depend on one another.

A piece of music will draw one in, teach one about its structure and secrets, whether one is listening consciously or not. This is so even if one has never heard a piece of music before. Listening to music is not a passive process but intensely active, involving a stream of inferences, hypotheses, expectations, and anticipations. We can grasp a new piece—how it is constructed, where it is going, what will come next—with such accuracy that even after a few bars we may be able to hum or sing along with it. Such anticipation, such singing along, is possible because one has knowledge, largely implicit, of musical “rules” (how a cadence must resolve, for instance) and a familiarity with particular musical conventions (the form of a sonata, or the repetition of a theme). When we “remember” a melody, it plays in our mind; it becomes newly alive.

Thus we can listen again and again to a recording of a piece of music, a piece we know well, and yet it can seem as fresh, as new, as the first time we heard it. There is not a process of recalling, assembling, recategorizing, as when one attempts to reconstruct or remember an event or a scene from the past. We recall one tone at a time, and each tone entirely fills our consciousness yet simultaneously relates to the whole. It is similar when we walk or run or swim—we do so one step, one stroke at a time, yet each step or stroke is an integral part of the whole. Indeed, if we think of each note or step too consciously, we may lose the thread, the motor melody.

It may be that Clive, incapable of remembering or anticipating events because of his amnesia, is able to sing and play and conduct music because remembering music is not, in the usual sense, remembering at all. Remembering music, listening to it, or playing it, is wholly in the present. Victor Zuckerkandl, a philosopher of music, explored this paradox beautifully in 1956 in “Sound and Symbol”:

The hearing of a melody is a hearing with the melody. . . . It is even a condition of hearing melody that the tone present at the moment should fill consciousness entirely, that nothing should be remembered, nothing except it or beside it be present in consciousness. . . . Hearing a melody is hearing, having heard, and being about to hear, all at once. . . . Every melody declares to us that the past can be there without being remembered, the future without being foreknown.

It has been twenty years since Clive’s illness, and, for him, nothing has moved on. One might say he is still in 1985 or, given his retrograde amnesia, in 1965. In some ways, he is not anywhere at all; he has dropped out of space and time altogether. He no longer has any inner narrative; he is not leading a life in the sense that the rest of us do. And yet one has only to see him at the keyboard or with Deborah to feel that, at such times, he is himself again and wholly alive. It is not the remembrance of things past, the “once” that Clive yearns for, or can ever achieve. It is the claiming, the filling, of the present, the now, and this is only possible when he is totally immersed in the successive moments of an act. It is the “now” that bridges the abyss.

As Deborah recently wrote to me, “Clive’s at-homeness in music and in his love for me are where he transcends amnesia and finds continuum—not the linear fusion of moment after moment, nor based on any framework of autobiographical information, but where Clive, and any of us, are finally, where we are who we are.” ♦

By signing up, you agree to our User Agreement and Privacy Policy & Cookie Statement . This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

By Manvir Singh

By Joyce Carol Oates

By Sam Knight

By Alexandra Schwartz

- Search Menu

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Emotions

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Acquisition

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Religion

- Music and Culture

- Music and Media

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Lifestyle, Home, and Garden

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Politics

- Law and Society

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Oncology

- Medical Toxicology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Medical Ethics

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Security

- Computer Games

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Cognitive Psychology

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Strategy

- Business History

- Business Ethics

- Business and Government

- Business and Technology

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic Systems

- Economic Methodology

- Economic History

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- International Political Economy

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Political Theory

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Politics and Law

- Public Administration

- Public Policy

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Developmental and Physical Disabilities Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

- < Previous chapter

- Next chapter >

38 Clive Wearing and Henry Molaison Reconsidered

- Published: September 2022

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

Varying extents of damage to the hippocampi and amygdalas of Henry Molaison and Clive Wearing may account for the differences in severity of their respective memory losses and consequent behaviours.

Signed in as

Institutional accounts.

- Google Scholar Indexing

- GoogleCrawler [DO NOT DELETE]

Personal account

- Sign in with email/username & password

- Get email alerts

- Save searches

- Purchase content

- Activate your purchase/trial code

Institutional access

- Sign in with a library card Sign in with username/password Recommend to your librarian

- Institutional account management

- Get help with access