Reducing Underage Drinking: A Collective Responsibility (2004)

Chapter: executive summary, executive summary.

A lcohol use by young people is dangerous, not only because of the risks associated with acute impairment, but also because of the threat to their long-term development and well-being. Traffic crashes are perhaps the most visible of these dangers, with alcohol being implicated in nearly one-third of youth traffic fatalities. Underage alcohol use is also associated with violence, suicide, educational failure, and other problem behaviors. All of these problems are magnified by early onset of teen drinking: the younger the drinker, the worse the problem. Moreover, frequent heavy drinking by young adolescents can lead to mild brain damage. The social cost of underage drinking has been estimated at $53 billion including $19 billion from traffic crashes and $29 billion from violent crime.

More youth drink than smoke tobacco or use other illegal drugs. Yet federal investments in preventing underage drinking pale in comparison with resources targeted (mostly to youths) at preventing illicit drug use. In fiscal 2000, $71.1 million was targeted at preventing underage alcohol use by the U.S. Departments of Health and Human Services (HHS), Justice, and Transportation. In contrast, the fiscal 2000 federal budget authority for drug abuse prevention (including prevention research) was 25 times higher, $1.8 billion; for tobacco prevention, funding for the Office of Smoking and Health, only one of several HHS agencies involved with smoking prevention, was approximately $100 million, with states spending a great deal more with resources from the states’ Medicaid reimbursement suits against the tobacco companies.

Although it is illegal to sell or give alcohol to youths under age 21, they

do not have a hard time getting it, and they often get it from adults. More than 90 percent of twelfth graders report that alcohol is “very easy” or “fairly easy” to get. And when underage youths drink, they drink more heavily and recklessly than adults. They report that they “usually” drink an average of four and a half drinks, an amount very close to the threshold of five drinks typically used to define heavy drinking (also referred to as binge drinking). In contrast, adult drinkers report usually drinking fewer than three drinks.

In response to a congressional request in the HHS fiscal 2002 appropriations act, the Board on Children, Youth, and Families of the National Research Council and the Institute of Medicine formed the Committee on Developing a Strategy to Reduce and Prevent Underage Drinking. The committee was directed to review a broad range of federal, state, and nongovernmental programs, from environmental interventions to programs focusing directly on youth attitudes and behaviors, and to develop a cost-effective strategy to reduce and prevent underage drinking. In conducting this review, the committee relied on the available scientific literature, including a series of papers written for the committee, public input, and its expertise.

The committee conducted its work within the framework of the current national policy establishing 21 as the minimum legal drinking age in every state. We concentrated more on population-based primary prevention approaches rather than on individually oriented approaches.

STRATEGY OVERVIEW

The committee reached the fundamental conclusion that underage drinking cannot be successfully addressed by focusing on youth alone. Youth drink within the context of a society in which alcohol use is normative behavior and images about alcohol are pervasive. They usually obtain alcohol—either directly or indirectly—from adults. Efforts to reduce underage drinking, therefore, need to focus on adults and must engage the society at large.

The preeminent goal of the recommended strategy is to create and sustain a broad societal commitment to reduce underage drinking. Such a commitment will require participation by multiple individuals and organizations at the national, state, local, and community levels who are in a position to affect youth decisions—including parents and other adults, alcohol producers, wholesalers and retail outlets, restaurants and bars, entertainment media, schools, colleges and universities, the military, landlords, community organizations, and youths themselves. The nation must collectively pursue opportunities to reduce the availability of alcohol to underage

drinkers, the occasions for underage drinking, and the demand for alcohol among young people.

THE STRATEGY

The committee’s proposed strategy for broad societal commitment to reduce underage drinking has ten main components.

National Adult-Oriented Media Campaign

Most adults express concern about youth drinking and support public policy actions to reduce youth access to alcohol. Nonetheless, youth obtain alcohol from adults. Parents tend to dramatically underestimate underage drinking generally and their own children’s drinking in particular. The first component in the strategy calls for the development of a media campaign, including rigorous formative research on effective messages, aimed at increasing specific actions by adults meant to reduce underage drinking and decreasing adult conduct that facilitates underage drinking.

Recommendation 6-1: The federal government should fund and actively support the development of a national media effort, as a major component of an adult-oriented campaign to reduce underage drinking.

Partnership to Prevent Underage Drinking

Despite laws that aim to preclude drinking by those under the age of 21, a significant amount of underage drinking occurs, generating revenues for producers, wholesalers, and retailers of alcoholic beverages, especially beer. The alcohol industry has declared its commitment to reducing underage drinking and has invested in programs with that aim. However, the outcomes of these efforts are not always apparent, and the motives are sometimes questioned. A partnership between the alcohol industry, government, and other private partners would facilitate a coordinated, evidence-based approach to reduce and prevent underage drinking.

Recommendation 7-1: All segments of the alcohol industry that profit from underage drinking, inadvertently or otherwise, should join with other private and public partners to establish and fund an independent nonprofit foundation with the sole mission of reducing and preventing underage drinking.

Alcohol Advertising

A substantial proportion of alcohol advertising reaches an underage audience and is presented in a style that is attractive to youths. For example, television alcohol advertisements routinely appear on programs for which the percentage of underage viewers is greater than the percentage of underage youths in the population. Although a clear causal link between advertising and youth consumption has not been established, youth exposure to advertising and marketing of products with particular appeal to youths should be reduced. Strengthened self-regulation would be in keeping with the industry’s stated commitment to avoid sale to minors and with recommendations by the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) in 1999 regarding industry advertising standards. Only one company has adopted the FTC’s 1999 recommendation that the industry create independent external review boards to address complaints regarding violations of advertising codes. In light of constitutional constraints on direct advertising restrictions, and to enable the industry to be responsive to public concerns about advertising, the most fruitful governmental response would be to facilitate public awareness of advertising practices.

Recommendation 7-2: Alcohol companies, advertising companies, and commercial media should refrain from marketing practices (including product design, advertising, and promotional techniques) that have substantial underage appeal and should take reasonable precautions in the time, place, and manner of placement and promotion to reduce youthful exposure to other alcohol advertising and marketing activity.

Recommendation 7-3: The alcohol industry trade associations, as well as individual companies, should strengthen their advertising codes to preclude placement of commercial messages in venues where a significant proportion of the expected audience is underage, to prohibit the use of commercial messages that have substantial underage appeal, and to establish independent external review boards to investigate complaints and enforce the codes.

Recommendation 7-4: Congress should appropriate the necessary funding for the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services to monitor underage exposure to alcohol advertising on a continuing basis and to report periodically to Congress and the public. The report should include information on the underage percentage of the exposed audience and estimated number of underage viewers of print and broadcasting alcohol advertising in national markets and, for television and radio broadcasting, in a selection of large local or regional markets.

Entertainment Media

Since artistic expression inevitably reflects the culture in which it is embedded, it is hardly surprising that alcohol use and alcohol products are frequently displayed or mentioned in prime-time television, movies, and music. Although the viewing or listening audiences for most of these media products are predominantly adult, some of them are disproportionately underage, and even the predominantly adult audiences inevitably include large numbers of young people. As in the case of commercial alcohol advertising, the entertainment media have a social responsibility to eschew displays or lyrics that portray underage drinking in a favorable light or that glamorize or promote alcohol consumption in products that are targeted toward or likely to be heard or viewed by large underage audiences. Labeling and notice requirements have been voluntarily adopted in analogous contexts. Although the industry restrictions should be undertaken on a voluntary basis, some independent oversight and public awareness of these standards is warranted.

Recommendation 8-1: The entertainment industries should use rating systems and marketing codes to reduce the likelihood that underage audiences will be exposed to movies, recordings, or television programs with unsuitable alcohol content, even if adults are expected to predominate in the viewing or listening audiences

Recommendation 8-2: The film rating board of the Motion Picture Association of America should consider alcohol content in rating films, avoiding G or PG ratings for films with unsuitable alcohol content, and assigning mature ratings for films that portray underage drinking in a favorable light.

Recommendation 8-3: The music recording industry should not market recordings that promote or glamorize alcohol use to young people; should include alcohol content in a comprehensive rating system, similar to those used by the television, film, and video game industries; and should establish an independent body to assign ratings and oversee the industry code.

Recommendation 8-4: Television broadcasters and producers should take appropriate precautions to ensure that programs do not portray underage drinking in a favorable light, and that unsuitable alcohol content is included in the category of mature content for purposes of parental warnings.

Recommendation 8-5: Congress should appropriate the necessary funds to enable the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services to conduct a periodic review of a representative sample of movies, televi -

sion programs, and music recordings and videos that are offered at times or in venues likely to have a significant youth audience (e.g., 15 percent) to ascertain the nature and frequency of lyrics or images pertaining to alcohol. The results of these reviews should be reported to Congress and the public.

Limiting Access

Limiting youth access to alcohol has been shown to be effective in reducing and preventing underage drinking and drinking-related problems. Since 21 became the nationwide legal drinking age, there have been significant decreases in drinking, fatal traffic crashes, alcohol-related crashes, and arrests for “driving under the influence” (DUI) among young people. Given the widespread availability of alcohol and easy access by underage drinkers, minimum drinking age laws must be enforced more effectively, along with social sanctions. The effectiveness of underage drinking laws could be enhanced through such approaches as compliance checks, server training, zero tolerance laws, and graduated driver licensing laws.

Recommendation 9-1: The minimum drinking age laws of each state should prohibit

purchase or attempted purchase, possession, and consumption of alcoholic beverages by persons under 21;

possession of and use of falsified or fraudulent identification to purchase or attempt to purchase alcoholic beverages;

provision of any alcohol to minors by adults, except to their own children in their own residences; and

underage drinking in private clubs and establishments.

Recommendation 9-2: States should strengthen their compliance check programs in retail outlets, using media campaigns and license revocation to increase deterrence.

Communities and states should undertake regular and comprehensive compliance check programs, including notification of retailers concerning the program and follow-up communication to them about the outcome (sale/no sale) for their outlet.

Enforcement agencies should issue citations for violations of underage sales laws, with substantial fines and temporary suspension of license for first offenses and increasingly stronger penalties thereafter, leading to permanent revocation of license after three offenses.

Communities and states should implement media campaigns in conjunction with compliance check programs detailing the program, its purpose, and outcomes.

Recommendation 9-3: The federal government should require states to achieve designated rates of retailer compliance with youth access prohibitions as a condition of receiving relevant block grant funding, similar to the Synar Amendment’s requirements for youth tobacco sales.

Recommendation 9-4: States should require all sellers and servers of alcohol to complete state-approved training as a condition of employment.

Recommendation 9-5: States should enact or strengthen dram shop liability statutes to authorize negligence-based civil actions against commercial providers of alcohol for serving or selling alcohol to a minor who subsequently causes injury to others, while allowing a defense for sellers who have demonstrated compliance with responsible business practices. States should include in their dram shop statutes key portions of the Model Alcoholic Beverage Retail Licensee Liability Act of 1985, including the responsible business practices defense.

Recommendation 9-6: States that allow Internet sales and home delivery of alcohol should regulate these activities to reduce the likelihood of sales to underage purchasers. States should

require all packages for delivery containing alcohol to be clearly labeled as such;

require persons who deliver alcohol to record the recipient’s age identification information from a valid government-issued document (such as a driver’s license or ID card); and

require recipients of home delivery of alcohol to sign a statement verifying receipt of alcohol and attesting that he or she is of legal age to purchase alcohol.

Recommendation 9-7: States and localities should implement enforcement programs to deter adults from purchasing alcohol for minors. States and communities should

routinely undertake shoulder tap or other prevention programs targeting adults who purchase alcohol for minors, using warnings, rather than citations, for the first offense;

enact and enforce laws to hold retailers responsible, as a condition of licensing, for allowing minors to loiter and solicit adults to purchase alcohol for them on outlet property; and

use nuisance and loitering ordinances as a means of discouraging youth from congregating outside of alcohol outlets in order to solicit adults to purchase alcohol.

Recommendation 9-8: States and communities should establish and implement a system requiring registration of beer kegs that records information on the identity of purchasers.

Recommendation 9-9: States should facilitate enforcement of zero tolerance laws in order to increase their deterrent effect. States should

modify existing laws to allow passive breath testing, streamlined administrative procedures, and administrative penalties and

implement media campaigns to increase young peoples’ awareness of reduced blood alcohol content (BAC) limits and of enforcement efforts.

Recommendation 9-10: States should enact and enforce graduated driver licensing laws.

Recommendation 9-11: States and localities should routinely implement sobriety checkpoints.

Recommendation 9-12: Local police, working with community leaders, should adopt and announce policies for detecting and terminating underage drinking parties, including:

routinely responding to complaints from the public about noisy teenage parties and entering the premises when there is probable cause to suspect underage drinking is taking place;

routinely checking, as a part of regular weekend patrols, open areas where teenage drinking parties are known to occur; and

routinely citing underage drinkers and, if possible, the person who supplied the alcohol when underage drinking is observed at parties.

Recommendation 9-13: States should strengthen efforts to prevent and detect use of false identification by minors to make alcohol purchases. States should

prohibit the production, sale, distribution, possession, and use of false identification for attempted alcohol purchase;

issue driver’s licenses and state identification cards that can be electronically scanned;

allow retailers to confiscate apparently false identification for law enforcement inspection; and

implement administrative penalties (e.g., immediate confiscation of a driver’s license and issuance of a citation resulting in a substantial fine) for attempted use of false identification by minors for alcohol purchases.

Recommendation 9-14: States should establish administrative procedures and noncriminal penalties, such as fines or community service, for alcohol infractions by minors.

Youth-Oriented Interventions

Although the proposed strategy focuses mainly on adult attitudes and behavior toward underage drinking and on reducing the availability of alcohol to underage youth, approaches that directly target youth are also needed. A national youth-oriented media campaign to reduce and prevent underage drinking would be premature in the absence of more evidence supporting this approach. However, effective education-oriented approaches in schools and other settings aimed at preventing alcohol use by youths, as well as interventions with youths who have already developed alcohol problems, play a role. Interventions that rely on provision of information alone, or that focus on increasing self-esteem or resisting peer pressure, have not been demonstrated to be effective.

Residential colleges and universities have witnessed serious drinking problems among students under 21. Despite efforts by nearly all campuses to address this problem, heavy drinking has not declined over the past decade. Residential colleges and universities are in a unique position to develop and evaluate comprehensive approaches that address both individual and population-level issues.

Recommendation 10-1: Intensive research and development for a youth-focused national media campaign relating to underage drinking should be initiated. If this work yields promising results, the inclusion of a youth-focused campaign in the strategy should be reconsidered.

Recommendation 10-2: The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and the U.S. Department of Education should fund only evidence-based education interventions, with priority given both to those that incorporate elements known to be effective and those that are part of comprehensive community programs.

Recommendation 10-3: Residential colleges and universities should adopt comprehensive prevention approaches, including evidence-based screening, brief intervention strategies, consistent policy enforcement, and environmental changes that limit underage access to alcohol. They should use universal education interventions, as well as selective and indicated approaches with relevant populations.

Recommendation 10-4: The National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism and the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration should continue to fund evaluations of college-based interventions, with a particular emphasis on targeting of interventions to specific college characteristics, and should maintain a list of evidence-based programs.

Recommendation 10-5: The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and states should expand the availability of effective clinical services for treating alcohol abuse among underage populations and for following up on treatment. The U.S. Department of Education, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, and the U.S. Department of Justice should establish policies that facilitate diagnosing and referring underage alcohol abusers and those who are alcohol dependent for clinical treatment.

Community Interventions

Community mobilization can be a powerful vehicle to implement and support interventions, especially those that target community-level policies and practices. Communities can design multipronged comprehensive initiatives that rely on scientifically based strategies and are responsive to the specific problems of their communities. College campuses and local communities have a reciprocal influence on one another in relation to student alcohol use and the need to develop complementary strategies.

Recommendation 11-1: Community leaders should assess the underage drinking problem in their communities and consider effective approaches—such as community organizing, coalition building, and the strategic use of the mass media—to reduce drinking among underage youth.

Recommendation 11-2: Public and private funders should support community mobilization to reduce underage drinking. Federal funding for reducing and preventing underage drinking should be available under a national program dedicated to community-level approaches to reducing underage drinking, similar to the Drug Free Communities Act, which supports communities in addressing substance abuse with targeted, evidence-based prevention strategies.

Government Assistance and Coordination

The ultimate responsibility for preventing and reducing underage drinking lies with the entire national community, not with government alone.

However, the federal and state governments have important responsibilities in addition to enforcing the law. These responsibilities include funding media campaigns, supporting community efforts, monitoring alcohol and entertainment industry portrayals of drinking, monitoring trends in underage drinking and the effectiveness of efforts to reduce it, coordinating multiple agency activities, and supporting continued research and evaluation.

Recommendation 12-1: A federal interagency coordinating committee on prevention of underage drinking should be established, chaired by the secretary of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Recommendation 12-2: A National Training and Research Center on Underage Drinking should be established in the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. This body would provide technical assistance, training, and evaluation support and would monitor progress in implementing national goals.

Recommendation 12-3: The secretary of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services should issue an annual report on underage drinking to Congress summarizing all federal agency activities, progress in reducing underage drinking, and key surveillance data.

Recommendation 12-4: Each state should designate a lead agency to coordinate and spearhead its activities and programs to reduce and prevent underage drinking.

Recommendation 12-5: The annual report of the secretary of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services on underage drinking should include key indicators of underage drinking.

Recommendation 12-6: The Monitoring the Future Survey and the National Survey on Drug Use and Health should be revised to elicit more precise information on the quantity of alcohol consumed and to ascertain brand preferences of underage drinkers.

Alcohol Excise Taxes

Alcoholic beverages are far cheaper (after adjusting for overall inflation) today than they were in the 1960s and 1970s. While raising excise taxes, and therefore prices, would have some effect on alcohol use by adults, price has been documented to have a differential effect on youth alcohol consumption patterns. Taxes can also be a source of revenue for funding strategies aimed at reducing underage drinking and its associated harms.

Recommendation 12-7: Congress and state legislatures should raise excise taxes to reduce underage consumption and to raise additional revenues for this purpose. Top priority should be given to raising beer taxes, and excise tax rates for all alcoholic beverages should be indexed to the consumer price index so that they keep pace with inflation without the necessity of further legislative action.

Research and Evaluation

Rigorous research and evaluation are needed to assess the effectiveness of specific interventions and to ensure that future refinements of the strategy are grounded in evidence-based approaches. Research related to prototype development for the proposed adult media campaign is a core component of the strategy outlined in this report. In addition, continued research and evaluation are necessary to develop new approaches aimed at reaching all segments of the underage population.

Recommendation 12-8: All interventions, including media messages and education programs, whether funded by public or private sources, should be rigorously evaluated, and a portion of all federal grant funds for alcohol-related programs should be designated for evaluation.

Recommendation 12-9: States and the federal government—particularly the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and the U.S. Department of Education—should fund the development and evaluation of programs to cover all underage populations.

In sum, our proposed strategy calls for development of a national campaign to engage adults in a concerted effort to stop enabling or ignoring youth drinking. The proposed strategy calls on the alcohol industry to enter a partnership with government and other private funders to implement a coordinated, evidence-based approach to reducing underage drinking. It proposes steps to increase compliance with laws against selling or providing alcohol to minors. It calls for reducing youth exposure to alcohol advertising or music and other entertainment with products and ads that glorify drinking. It recognizes the potential importance of school-based education approaches and the need for residential colleges and universities to implement comprehensive approaches. It calls on local leaders to apply the multiple tools available to address underage drinking within the context of their communities. And it challenges federal and state governments to coordinate their efforts and to raise excise taxes to reduce underage consumption and raise revenues for the proposed strategy. Finally, it recommends ongoing monitoring and continued research and evaluation to facilitate continued refinement of the strategy and its implementation.

Alcohol use by young people is extremely dangerous - both to themselves and society at large. Underage alcohol use is associated with traffic fatalities, violence, unsafe sex, suicide, educational failure, and other problem behaviors that diminish the prospects of future success, as well as health risks – and the earlier teens start drinking, the greater the danger. Despite these serious concerns, the media continues to make drinking look attractive to youth, and it remains possible and even easy for teenagers to get access to alcohol.

Why is this dangerous behavior so pervasive? What can be done to prevent it? What will work and who is responsible for making sure it happens? Reducing Underage Drinking addresses these questions and proposes a new way to combat underage alcohol use. It explores the ways in which may different individuals and groups contribute to the problem and how they can be enlisted to prevent it. Reducing Underage Drinking will serve as both a game plan and a call to arms for anyone with an investment in youth health and safety.

READ FREE ONLINE

Welcome to OpenBook!

You're looking at OpenBook, NAP.edu's online reading room since 1999. Based on feedback from you, our users, we've made some improvements that make it easier than ever to read thousands of publications on our website.

Do you want to take a quick tour of the OpenBook's features?

Show this book's table of contents , where you can jump to any chapter by name.

...or use these buttons to go back to the previous chapter or skip to the next one.

Jump up to the previous page or down to the next one. Also, you can type in a page number and press Enter to go directly to that page in the book.

Switch between the Original Pages , where you can read the report as it appeared in print, and Text Pages for the web version, where you can highlight and search the text.

To search the entire text of this book, type in your search term here and press Enter .

Share a link to this book page on your preferred social network or via email.

View our suggested citation for this chapter.

Ready to take your reading offline? Click here to buy this book in print or download it as a free PDF, if available.

Get Email Updates

Do you enjoy reading reports from the Academies online for free ? Sign up for email notifications and we'll let you know about new publications in your areas of interest when they're released.

Reducing the Alcohol Abuse Among the Youth Essay

- To find inspiration for your paper and overcome writer’s block

- As a source of information (ensure proper referencing)

- As a template for you assignment

Introduction

Statement of the problem, alternative solutions, the preferred solution, budgetary requirements.

The US government has paid considerable attention to the development of the most favorable environment for the youth. Educational programs are aimed at helping teenagers find their place in American society. Many programs exist to help this population address the most urgent challenges. Too Smart To Start is a program focusing on the prevention of underage alcohol abuse (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration [SAMHSA], 2017).

The program involves the provision of strategies, as well as resources, to help schools and communities to prevent alcohol abuse among the youth. Davis (2017) notes that initiative groups within communities use this program to address the problem. However, the program can be improved significantly and reach more people. This paper includes a brief discussion of two possible ways to improve the problem and the justification for the use of one of the options.

The level of alcohol abuse among the youth has decreased during the past three decades, but in some cases the changes are insignificant. The most significant improvements are apparent when the use of alcohol within the past 12 months is assessed. For example, almost 80% of 12 – graders, over 70% of 10-graders, and almost 55% of 8-graders reported alcohol use and binge drinking during the past 12 months in 1991 (Patrick & Schulenberg, 2014).

The recent studies show that 70% of 12 th -grade students, 55% of 10 th -grade students, and 30% of 8 th -grade students reported binge drinking and alcohol use during the past 12 months in 2011. The trend is promising, but another assessment shows that the level of alcohol abuse is still rather high and has not changed during the past three decades. Approximately 30% of 12 th -grade students and 20% of 10 th -grade students reported binge drinking or alcohol use within the past 30 days in 1991 (Patrick & Schulenberg, 2014). The figures were almost the same in 2011. It is also important to note that the prevalence of alcohol use is higher in underprivileged communities.

The negative effects of alcohol use on adolescents’ health and academic performance have been explored in detail. Importantly, the levels of alcohol use among adolescents are quite alarming as there is a ban on selling alcohol to people under 21. Researchers stress that teenage alcohol abuse may lead to the persistence of the addiction in adulthood, the development of serious health issues (ulcers, cancer, depression, and so on), poor academic performance (Patrick & Schulenberg, 2014).

As a result, young people can have limited access to higher education and a wide range of employment opportunities, which deteriorates American communities. In simple words, teenagers coming from underprivileged families are at a high risk of alcohol abuse, which results in these populations’ socioeconomic issues. The implementation of effective programs aimed at preventing alcohol abuse among adolescents can break this vicious circle.

Too Smart To Start is one of such programs. It is funded by SAMHSA that is an agency within the USDHHS (United States Department of Health and Human Services). The organization’s budget for the promotion of preventing efforts is $150 million in 2018 (Department of Health and Human Services, 2017). The mission of SAMHSA is to “reduce the impact of substance abuse and mental illness on America’s communities” (SAMHSA, 2017). As has been mentioned above the program in question assists in communities’ struggle against the problem. Organizations, initiative groups, schools, and even individuals can address the program and benefit from the use of resources or assistance in the development of effective strategies to solve issues.

Solution One

Nevertheless, a third of adolescents still use alcohol so more effective solutions should be developed. One of the possible solutions can be the development of a personality-targeted intervention. Conrod et al. (2013) evaluated the effectiveness of a personality-targeted selective program aimed at the prevention of alcohol abuse among adolescents. The researchers claim that such an approach is effective and can be applied in school-based contexts. One of the key factors contributing to the success of the program was the provision of training to the faculty.

To implement this program, it is important to undertake several steps. First, it is important to develop personality-targeted interventions for different personality types. This step will require thorough research and possible collaboration with researchers, mental health professionals, or educators. The next step will be the development of effective training programs for the faculty. It is possible to extend the boundaries of the school-based setting and come up with strategies that can be used by parents or other relatives. Finally, it is important to inform communities about the existence of the new program. The information can be provided through newsletters.

The budgetary requirements for this solution will be comparatively small. The vast majority of the funds will be used to develop the strategies. These resources will be allocated to access databases to search for scholarly resources on the matter, pay to researchers and professionals involved in the process of the development of the programs, etc. It is also necessary to allocate funds to provide the stakeholders with the necessary materials (manuals and other resources). The budget for this program can be up to $100 thousand (with $70,000 for the development of the interventions and $30,000 for the materials and resources).

Solution Two

Another solution can be based on the one mentioned above, but it will require more time and funds. The use of personality-targeted interventions in school-based and family-based settings can be implemented more effectively. The first steps involving the development of the programs will be unchanged. The basis for the new interventions will be the research implemented by Conrod et al. (2013). At that, it is possible to extend the limits of the interventions.

It is necessary to create effective programs that could address the needs of different groups. Apart from focusing on personality types, it is necessary to pay attention to age, ethnicity, culture, socioeconomic status, and academic performance.

The steps associated with communication should also be further developed. Apart from the newsletters, it is essential to develop a far-reaching promotion campaign. Social media can become the primary channel to make communities aware of the new opportunities. To encourage educational establishments and various initiative groups to participate in this program, it is possible to establish a prize. The award can be one of the grants provided by SAMHSA (SAMHSA, 2017).

It can also be effective to send some information directly to the most struggling communities. In many cases, these communities have many issues to address and can simply miss this opportunity. This solution will require a larger investment, but is far-reaching and can improve the situation significantly. The budget requirements will be discussed in detail below (see Table 1).

The second option is the preferred solution as it will reach more people and will be able to address the organization’s mission, which is reducing the effects of substance abuse on American communities. Personality-targeted interventions have proved to be effective and beneficial for the target audience and overall communities (Conrod et al., 2013). Adolescents learn about harms of the alcohol use, about ways to fit in different groups, come to terms with themselves, and feel empowered.

The new program will potentially reduce the number of adolescents who use and abuse alcohol. Specific attention will be paid to underprivileged groups, which will allow them to improve their socioeconomic status in the future. The program can be funded from several resources. SAMHSA can provide the major part of the funds. As for the provision of training to the participants of the program (educators, parents, social workers, etc.), SAMHSA can address state governments as well as local charities or communities to fund the necessary activities.

Although quite substantial investment may be needed, the benefits of the program cannot be overestimated. The necessary funds may reach up to $150,000 depending on the number of participants (see Table 1). 2018 budget of SAMHSA has the necessary funds, but the organization can address other agencies and organizations to help in the implementation of the interventions. One of SAMHSA grants (or several grants if necessary) will be provided to the winners.

Table 1. Budgetary Requirements.

| Activities | US Dollars |

| Research | 30,000 |

| Program Development | 30,000 |

| Staff Training | 10,000 |

| Materials | Over 30,000 |

| Media and Promotion (including materials) | 5,000 |

| Training of the educators or initiative groups | Over 15,000 |

| Award (grant) | 10,000 |

On balance, it is necessary to note that the program that will reduce the level of alcohol use among adolescents will be based on the personality-targeted intervention. The program will address the needs of teenagers who will receive a chance to integrate into society more effectively. The program can become a basis or a starting point for the development of interventions aimed at preventing drug abuse among teenagers. American communities can benefit from such programs if they are implemented properly.

Conrod, P., O’Leary-Barrett, M., Newton, N., Topper, L., Castellanos-Ryan, N., Mackie, C., & Girard, A. (2013). Effectiveness of a selective, personality-targeted prevention program for adolescent alcohol use and misuse. JAMA Psychiatry, 70 (3), 334-342.

Davis, N. (2017). It takes a community. The Southside Times . Web.

Department of Health and Human Services. (2017). Putting America’s health first . Web.

Patrick, M. E., & Schulenberg, J. E. (2014). Prevalence and predictors of adolescent alcohol use and binge drinking in the United States. Alcohol Research, 35 (2), 193-200.

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2017). Too smart to start . Web.

- The Psychology of Addiction and Addictive Behaviors

- Crack Cocaine Abuse and Its Social Effects

- Drug and Alcohol Abuse Among Teenagers

- Underage Drinking and Teen Alcohol Abuse

- Drug and Alcohol Abuse

- Illegal Importation of Drugs

- Reflection on Drugs, Narcotics and Treatment Options

- Paul Chabot: Reality Check Concerning Drugs

- Walter Green: Theoretical Orientation of the Practitioner

- Decreasing Overall Alcohol Consumption

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2021, March 23). Reducing the Alcohol Abuse Among the Youth. https://ivypanda.com/essays/reducing-the-alcohol-abuse-among-the-youth/

"Reducing the Alcohol Abuse Among the Youth." IvyPanda , 23 Mar. 2021, ivypanda.com/essays/reducing-the-alcohol-abuse-among-the-youth/.

IvyPanda . (2021) 'Reducing the Alcohol Abuse Among the Youth'. 23 March.

IvyPanda . 2021. "Reducing the Alcohol Abuse Among the Youth." March 23, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/reducing-the-alcohol-abuse-among-the-youth/.

1. IvyPanda . "Reducing the Alcohol Abuse Among the Youth." March 23, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/reducing-the-alcohol-abuse-among-the-youth/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Reducing the Alcohol Abuse Among the Youth." March 23, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/reducing-the-alcohol-abuse-among-the-youth/.

IvyPanda uses cookies and similar technologies to enhance your experience, enabling functionalities such as:

- Basic site functions

- Ensuring secure, safe transactions

- Secure account login

- Remembering account, browser, and regional preferences

- Remembering privacy and security settings

- Analyzing site traffic and usage

- Personalized search, content, and recommendations

- Displaying relevant, targeted ads on and off IvyPanda

Please refer to IvyPanda's Cookies Policy and Privacy Policy for detailed information.

Certain technologies we use are essential for critical functions such as security and site integrity, account authentication, security and privacy preferences, internal site usage and maintenance data, and ensuring the site operates correctly for browsing and transactions.

Cookies and similar technologies are used to enhance your experience by:

- Remembering general and regional preferences

- Personalizing content, search, recommendations, and offers

Some functions, such as personalized recommendations, account preferences, or localization, may not work correctly without these technologies. For more details, please refer to IvyPanda's Cookies Policy .

To enable personalized advertising (such as interest-based ads), we may share your data with our marketing and advertising partners using cookies and other technologies. These partners may have their own information collected about you. Turning off the personalized advertising setting won't stop you from seeing IvyPanda ads, but it may make the ads you see less relevant or more repetitive.

Personalized advertising may be considered a "sale" or "sharing" of the information under California and other state privacy laws, and you may have the right to opt out. Turning off personalized advertising allows you to exercise your right to opt out. Learn more in IvyPanda's Cookies Policy and Privacy Policy .

Our systems are now restored following recent technical disruption, and we’re working hard to catch up on publishing. We apologise for the inconvenience caused. Find out more: https://www.cambridge.org/universitypress/about-us/news-and-blogs/cambridge-university-press-publishing-update-following-technical-disruption

We use cookies to distinguish you from other users and to provide you with a better experience on our websites. Close this message to accept cookies or find out how to manage your cookie settings .

Login Alert

- > Journals

- > Cambridge Prisms: Global Mental Health

- > Global Mental Health

- > Volume 9

- > Alcohol use among adolescents in India: a systematic...

Article contents

Introduction, financial support, conflict of interest, ethical standards, alcohol use among adolescents in india: a systematic review.

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 07 January 2022

- Supplementary materials

Alcohol use is typically established during adolescence and initiation of use at a young age poses risks for short- and long-term health and social outcomes. However, there is limited understanding of the onset, progression and impact of alcohol use among adolescents in India. The aim of this review is to synthesise the evidence about prevalence, patterns and correlates of alcohol use and alcohol use disorders in adolescents from India.

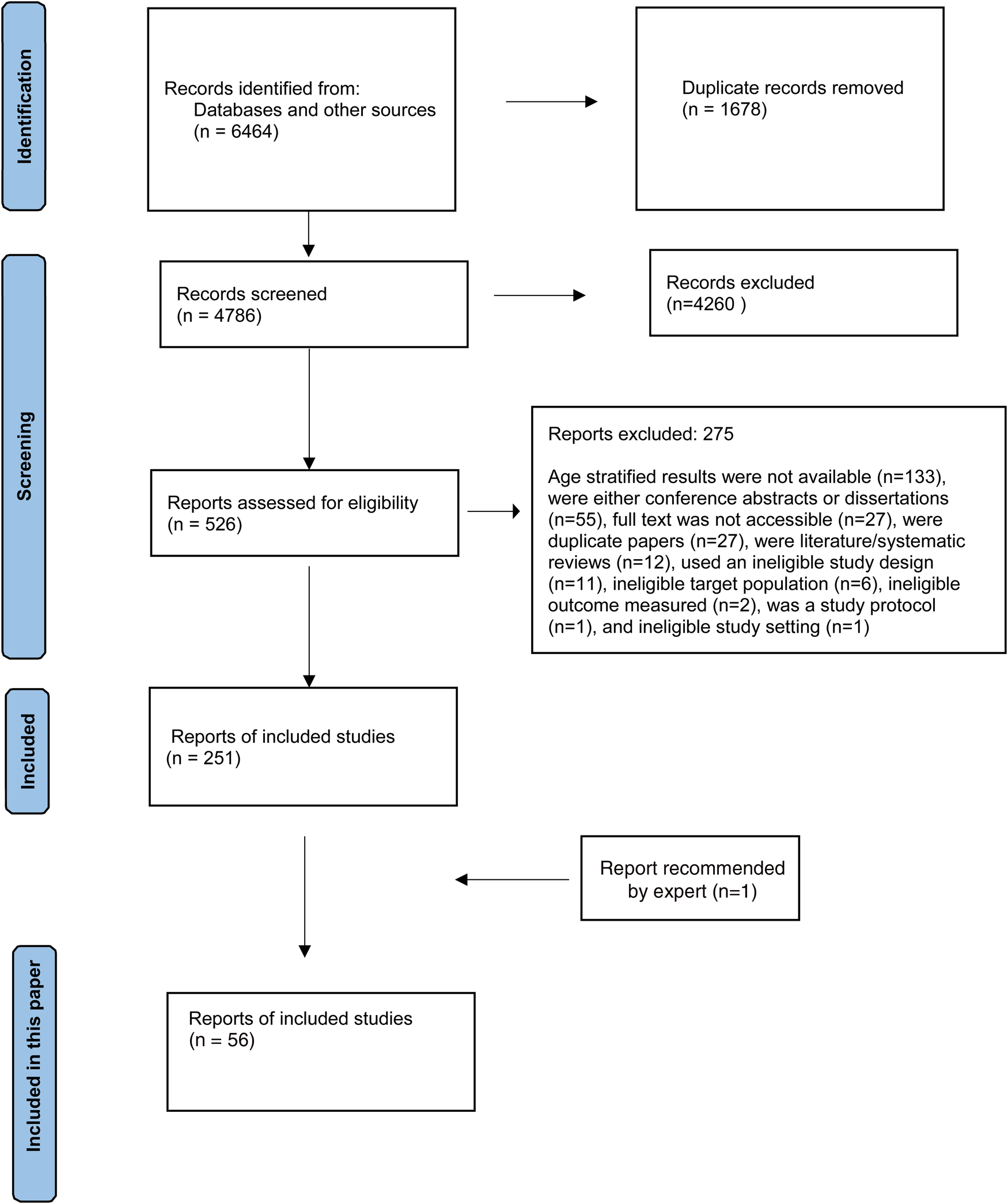

Systematic review was conducted using relevant online databases, grey literature and unpublished data/outcomes from subject experts. Inclusion and exclusion criteria were developed and applied to screening rounds. Titles and abstracts were screened by two independent reviewers for eligibility, and then full texts were assessed for inclusion. Narrative synthesis of the eligible studies was conducted.

Fifty-five peer-reviewed papers and one report were eligible for inclusion in this review. Prevalence of ever or lifetime alcohol consumption ranged from 3.9% to 69.8%; and prevalence of alcohol consumption at least once in the past year ranged from 10.6% to 32.9%. The mean age for initiation of drinking ranged from 14.4 to 18.3 years. Some correlates associated with alcohol consumption included being male, older age, academic difficulties, parental use of alcohol or tobacco, non-contact sexual abuse and perpetuation of violence.

The evidence base for alcohol use among adolescents in India needs a deeper exploration. Despite gaps in the evidence base, this synthesis provides a reasonable understanding of alcohol use among adolescents in India and can provide direction to policymakers.

According to the Global Burden of Diseases, Injuries, and Risk Factors Study (GBD) 2019, among adolescents and young adults (aged 10–24 years), alcohol-attributable burden is second highest among all risk factors contributing to disability-adjusted life years in this age group (GBD 2019 Risk Factors Collaborators, 2020 ). The exposure of the adolescent brain to alcohol is shown to result in various cognitive and functional deficits related to verbal learning, attention, and visuospatial and memory tasks, and behavioural inefficiencies such as disinhibition and elevated risk-taking (Spear, Reference Spear 2018 ). Alcohol consumption in adolescents results in a range of adverse outcomes across several domains and includes road traffic accidents and other non-intentional injuries, violence, mental health problems, intentional self-harm and suicide, HIV and other infectious diseases, poor school performance and drop-out, and poor employment opportunities (Hall et al ., Reference Hall, Patton, Stockings, Weier, Lynskey, Morley and Degenhardt 2016 ).

Adolescence is a critical period in which exposure to adversities such as poverty, family conflict and negative life experiences (e.g. violence) can have long-term emotional and socio-economic consequences for adolescents, their families and communities (Knapp et al ., Reference Knapp, Scott and Davies 1999 ; Knapp et al ., Reference Knapp, McCRONE, Fombonne, Beecham and Wostear 2002 ). Substance use, including alcohol, is typically established during adolescence and this period is peak risk for onset and intensification of substance use behaviours that pose risks for short- and long-term health (Anthony and Petronis, Reference Anthony and Petronis 1995 ; DeWit et al ., Reference DeWit, Adlaf, Offord and Ogborne 2000 ; Hallfors et al ., Reference Hallfors, Waller, Bauer, Ford and Halpern 2005 ; Schmid et al ., Reference Schmid, Hohm, Blomeyer, Zimmermann, Schmidt, Esser and Laucht 2007 ; Hadland and Harris, Reference Hadland and Harris 2014 ). As such, early initiation of alcohol use among adolescents can provide a useful indication of the potential future burden among adults including increased risk for academic failure, mental health problems, antisocial behaviour, physical illness, risky sexual behaviours, sexually transmitted diseases, early-onset dementia and the development of alcohol use disorders (AUDs) (Hingson et al ., Reference Hingson, Heeren and Winter 2006 ; King and Chassin, Reference King and Chassin 2007 ; Dawson et al ., Reference Dawson, Goldstein, Patricia Chou, June Ruan and Grant 2008 ; Nordström et al ., Reference Nordström, Nordström, Eriksson, Wahlund and Gustafson 2013 ).

India continues to develop rapidly, and accounts for most of the increase in alcohol consumption per capita for WHO's South-East Asia region (World Health Organization, 2018 ). Although India has a relatively high abstinence rate, many people who do drink are either risky drinkers or have AUDs (Benegal, Reference Benegal 2005 ; Rehm et al ., Reference Rehm, Mathers, Popova, Thavorncharoensap, Teerawattananon and Patra 2009 ). Finally, the existing policies in India have failed to reduce the harm from alcohol because the implementation of alcohol control efforts is fragmented, lacks consensus, is influenced by political considerations, and is driven by narrow economic and not health concerns (Gururaj et al ., Reference Gururaj, Gautham and Arvind 2021 ).

India has the largest population of adolescents globally (253 million people aged 10–19 years), constituting 21% of the population (Government of India, 2011 ; Boumphrey, Reference Boumphrey 2012 ). Additionally, adolescents as young as 13–15 years of age have started consuming alcohol in India (Gururaj et al ., Reference Gururaj, Varghese, Benegal, Rao, Pathak, Singh and Singh 2016 ). Despite this growing public health problem, the official policy response in India remains primarily focused on AUDs, particularly alcohol dependence in adults, with an absolute disregard for the potential of prevention programmes. One potential reason for this is the limited understanding of the onset and progression of alcohol use and AUDs amongst adolescents in India. The aim of this paper is to bridge that knowledge gap by synthesising the evidence about the prevalence and correlates of alcohol use and AUDs in adolescents from India.

The specific objectives are to examine the following in adolescents from India: (a) prevalence of current and lifetime use of alcohol, (b) prevalence of current AUDs, (c) patterns (e.g. frequency, quantity) of alcohol use, (d) sociodemographic, social and clinical correlates of alcohol use and AUDs, and (e) explanatory models of and attitudes towards alcohol use and AUDs, e.g. perceptions of the problem and its causes. This paper synthesises the evidence about alcohol and AUDs using data from a comprehensive review that we conducted of any substance use and substance use disorders amongst adolescents in India.

Systematic review . The review protocol was registered prospectively on Prospero (registration ID CRD 42017080344).

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

There were no limits placed on the year of publication of the paper, gender of the participants and study settings in India. We only included English language publications as academic literature from India is predominantly published in such publications. Adolescents were defined as anyone between 10 and 24 years of age (Sawyer et al ., Reference Sawyer, Azzopardi, Wickremarathne and Patton 2018 ). Studies reporting alcohol use and/or AUDs in a wider age range (including 10–24 years) were included only if data were separately presented for the 10–24-year age group. We included observational studies (surveys, case-control studies, cohort studies), qualitative studies and intervention studies (only if baseline prevalence data were presented). We included studies which examined alcohol use and AUDs defined as per the International Classification of Diseases (ICD)/Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM)/clinical criteria or using a standardised screening or diagnostic tool.

We searched the following databases: PsycARTICLES, PsycInfo, Embase, Global Health, CINAHL, Medline and Indmed. The search strategy was organised under the following concepts: substance (e.g. alcohol, drug), misuse/use disorder (e.g. addiction, intoxication), young people (e.g. adolescent, child) and India (e.g. India, names of individual Indian states). The detailed search strategy is listed in Appendix A .

Two reviewers (DG and KW) independently inspected the titles and abstracts of studies identified through the database search. Any conflicts about eligibility between the two reviewers were resolved by AN. If the title and abstract did not offer enough information, the full paper was retrieved to ascertain whether it was eligible for inclusion. Screening of full texts was done by AN, AG and DG; and any conflicts about eligibility were resolved by UB. Screening of the results of the search was done using Covidence ( https://www.covidence.org/ ), an online screening and data extraction tool.

AN searched the following resources to identify relevant grey literature: Open Grey, OAlster, Google, ProQuest, official English language websites of the World Health Organization and World Bank, English language websites of ministries of each state and union territory within India responsible for substance misuse as well as the official websites of the Indian Narcotics Control Bureau and Ministry of Social Justice and Empowerment.

Any grey literature with relevant data published by a recognised non-governmental organisation, state, national or international organisation was included. Studies were included based on the robustness of study design and quality of data. If there were multiple editions of any published piece of grey literature, only the latest published edition of that report was included. Once retrieved, their titles, content pages and summaries were read by AN and if deemed eligible they were added to a list of potentially eligible reports. If the grey literature's summary, content and title did not include enough information, then the full text was examined by AN to determine eligibility for inclusion.

Finally, experts in the field of substance use disorders in India were contacted to explore if they could identify any further useful sources of information and were invited to submit unpublished data and unreported outcomes for possible inclusion into the review. Reference lists of selected studies, grey literature and relevant reviews were inspected for additional potential studies.

A formal data extraction worksheet was designed to extract data relevant to the study aims. The following data were extracted: centre (e.g. name of city), sampling technique, sample (e.g. general population), sample size, age(s), tool used to measure alcohol use and/or AUD, definitions of alcohol use and AUD, prevalence of alcohol use and/or AUD, age of initiation, type of alcohol, quantity and frequency of alcohol use, attitudes towards alcohol use, effect of alcohol on health, social, educational and other domains, and risk factors/correlates of alcohol use and or AUD. Following Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (Moher et al ., Reference Moher, Shamseer, Clarke, Ghersi, Liberati and Petticrew 2015 ), a record was made of the number of papers retrieved, the number of papers excluded and the reasons for their exclusion. AT independently performed data extraction, AG checked the data extraction, and AN arbitrated any unresolved issues. The quality of reporting of included studies was examined using the STROBE Statement – checklist of items that should be included in reports of observational studies (Von Elm et al ., Reference Von Elm, Altman, Egger, Pocock, Gøtzsche and Vandenbroucke 2007 ).

A descriptive analysis of the data was conducted, and the results are mainly reported in a narrative format focusing on each of the objectives described above (Popay et al ., Reference Popay, Roberts, Sowden, Petticrew, Arai, Rodgers and Duffy 2006 ).

In total, 6464 references were identified through the search strategies described above. Overall, 251 records were eligible for the wider review, of which 55 were about alcohol use and have been reported in this paper ( Fig. 1 ). Additionally, one report of magnitude of substance use in India which was recommended by an expert was also included (Ambekar et al ., Reference Ambekar, Agrawal, Rao, Mishra, Khandelwal and Chadda 2019 ).

Fig. 1. PRISMA flow diagram.

Study descriptions

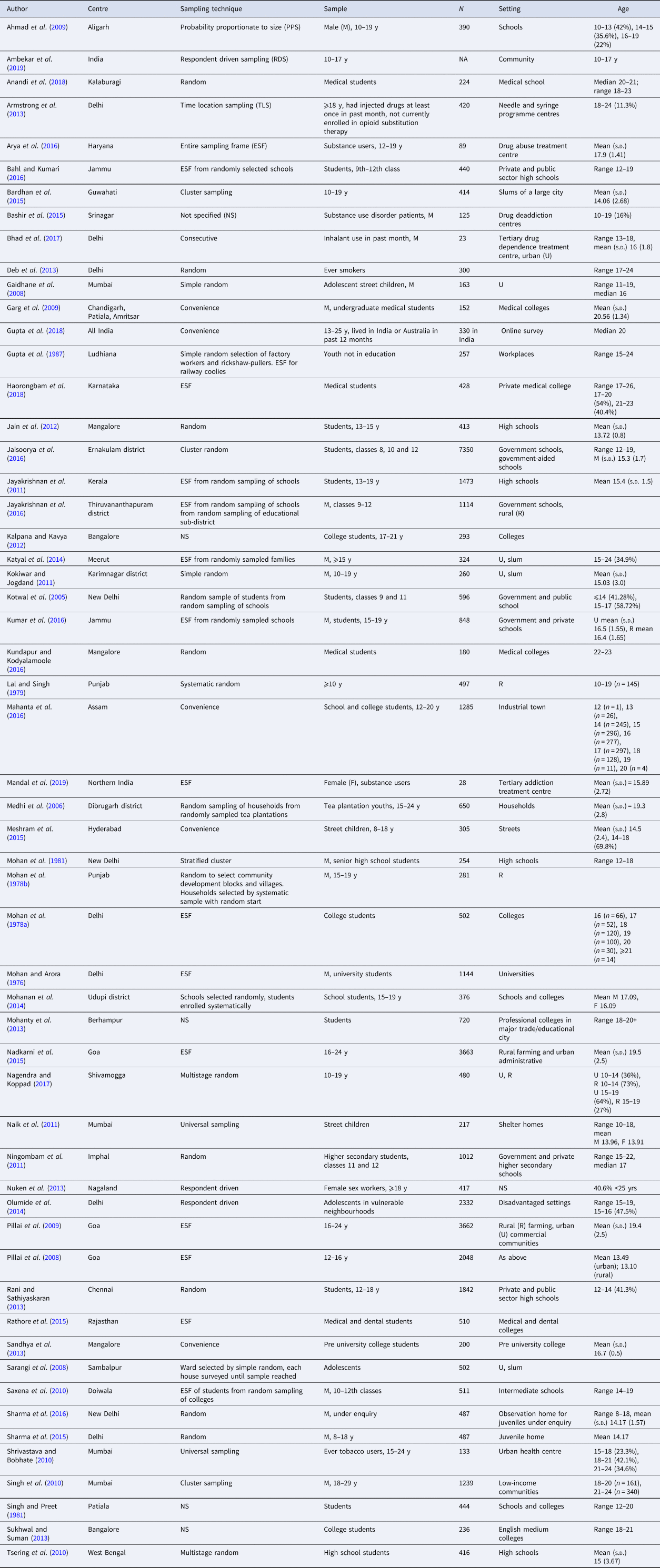

One study was conducted online (Gupta et al ., Reference Gupta, Lam, Pettigrew and Tait 2018 ) and one in a national treatment centre in North India (Mandal et al ., Reference Mandal, Parmar, Ambekar and Dhawan 2019 ), both of which potentially had access to participants from across the country ( Table 1 ). All the rest were conducted at a single or multiple settings in a city, town, district, village or state. The sample size of the studies ranged from 23 (Bhad et al ., Reference Bhad, Jain, Dhawan and Mehta 2017 ) to 7350 (Jaisoorya et al ., Reference Jaisoorya, Beena, Beena, Ellangovan, Jose, Thennarasu and Benegal 2016 ). In studies that reported mean age of the samples, it ranged from 13.10 years (Pillai et al ., Reference Pillai, Patel, Cardozo, Goodman, Weiss and Andrew 2008 ) to 20.56 years (Garg et al ., Reference Garg, Chavan, Singh and Bansal 2009 ).

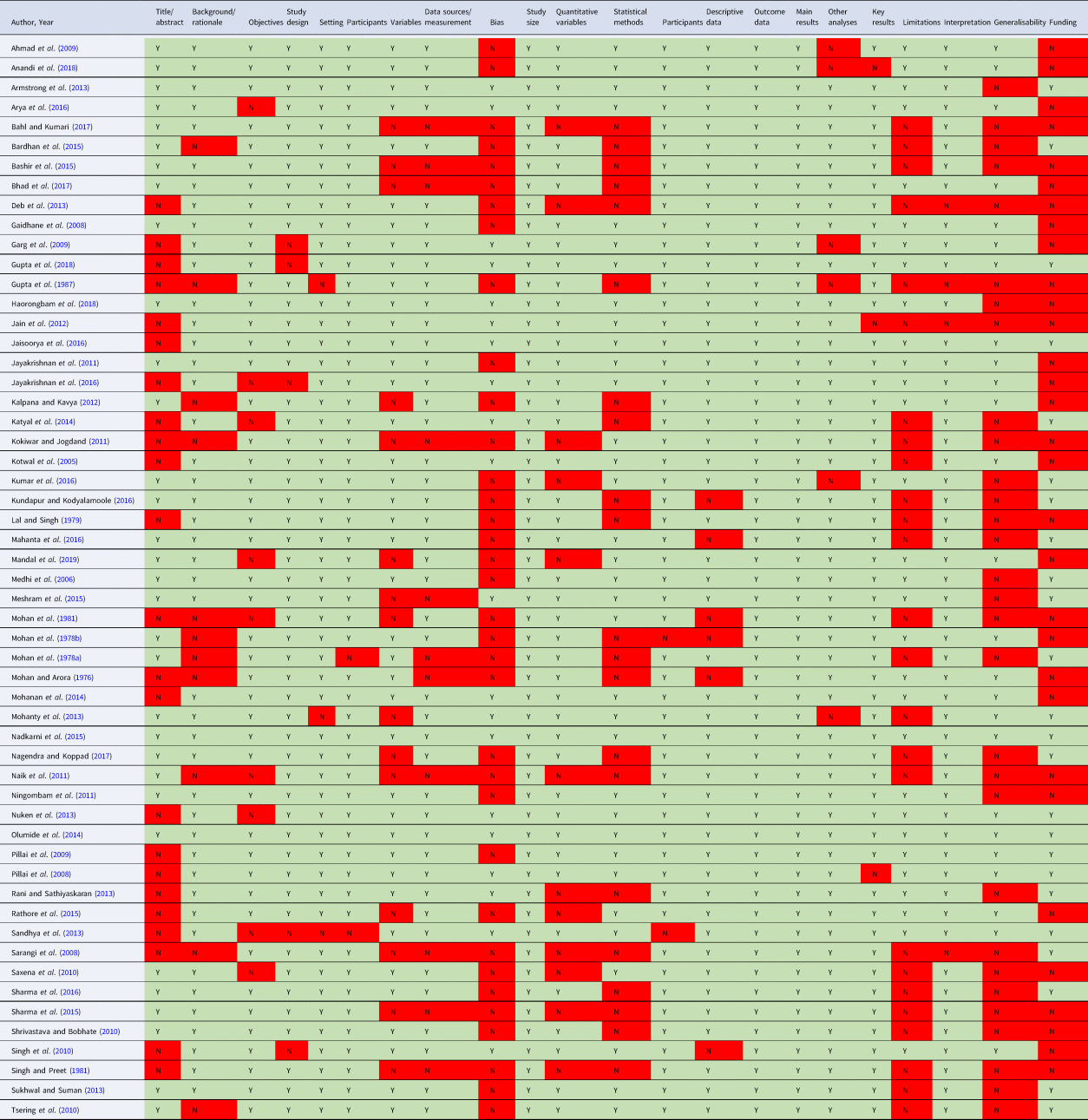

Table 1 Description of studies included in the review

Prevalence of alcohol use and AUD

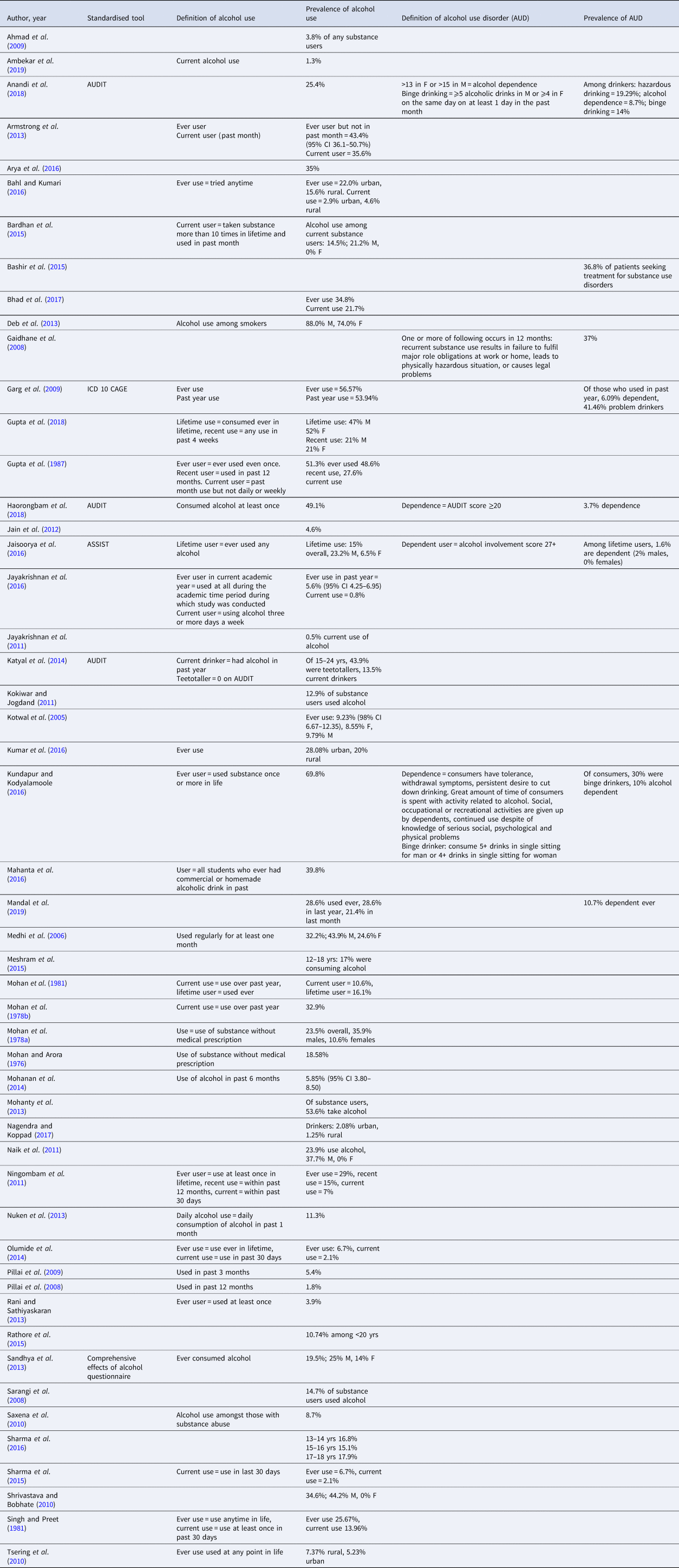

The prevalence of ever use or lifetime use, broadly defined as consumption of alcohol at least once in their lifetime, ranged from 3.9% in school students aged 12–18 years (Rani and Sathiyaskaran, Reference Rani and Sathiyaskaran 2013 ) to 69.8% in 22–23-year-old medical students (Kundapur and Kodyalamoole, Reference Kundapur and Kodyalamoole 2016 ) ( Table 2 ). Ever use in females ranged from 6.5% in students from class 8 to class 12 (age 12–19 years) (Jaisoorya et al ., Reference Jaisoorya, Beena, Beena, Ellangovan, Jose, Thennarasu and Benegal 2016 ) to 52% in an online survey of adolescents aged 13–17 years (Gupta et al ., Reference Gupta, Lam, Pettigrew and Tait 2018 ), and in males it ranged from 9.79% in students from classes 9 and 11 (age up to 17 years) (Kotwal et al ., Reference Kotwal, Thakur and Seth 2005 ) to 47% in an online survey of adolescents aged 13–17 years (Gupta et al ., Reference Gupta, Lam, Pettigrew and Tait 2018 ). The prevalence of ever use in rural areas ranged from 7.37% in high school students (Tsering et al ., Reference Tsering, Pal and Dasgupta 2010 ) to 20% in students aged 15–19 years (Kumar et al ., Reference Kumar, Kumar, Shora, Dewan, Mengi and Razaq 2016 ), and in urban areas it ranged from 5.23% in high school students (Tsering et al ., Reference Tsering, Pal and Dasgupta 2010 ) to 23.08% in students aged 15–19 years (Kumar et al ., Reference Kumar, Kumar, Shora, Dewan, Mengi and Razaq 2016 ).

Table 2 Prevalence of alcohol use and alcohol use disorders

Current use

The definition of current use of alcohol varied across studies. The more commonly used definitions were alcohol consumption at least once in the past year for which the prevalence ranged from 10.6% in senior high school students aged 12–18 years (Mohan et al ., Reference Mohan, Rustagi, Sundaram and Prabhu 1981 ) to 32.9% in 15–19-year-old individuals from rural settings (Mohan et al ., Reference Mohan, Sharma, Darshan, Sundaram and Neki 1978b ); and at least once in the past 30 days (month) for which the prevalence ranged from 2.1% (Sharma et al ., Reference Sharma, Singh, Lal and Goel 2015 ) in 15–19-year olds from disadvantaged urban settings and 35.6% in injectable drug users attending needle and syringe programme centres (Armstrong et al ., Reference Armstrong, Nuken, Samson, Singh, Jorm and Kermode 2013 ). Some studies did not define current use and others used non-standard definition of current use such as ‘who had not used drugs either daily or weekly in the past month’ (27.6%) (Gupta et al ., Reference Gupta, Narang, Verma, Panda, Garg, Munjal and Singh 1987 ), and ‘habit of using alcohol, 3 days or more a week’ (0.8%) (Jayakrishnan et al ., Reference Jayakrishnan, Geetha, Mohanan Nair, Thomas and Sebastian 2016 ). The biggest countrywide survey of substance use in India reported a prevalence of current alcohol use to be 1.3% amongst those aged 10–17 years (Ambekar et al ., Reference Ambekar, Agrawal, Rao, Mishra, Khandelwal and Chadda 2019 ).

Some studies reported the prevalence of AUDs and defined them using standardised tools (Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test [AUDIT], CAGE questionnaire, Alcohol, Smoking and Substance Involvement Screening Test [ASSIST]), ICD 10 criteria or bespoke definitions. Among medical students (18–23 years) who were drinkers, the prevalence of hazardous drinking was 19.29% (Anandi et al ., Reference Anandi, Halgar, Reddy and Indupalli 2018 ), alcohol dependence was 3.7–10% (Kundapur and Kodyalamoole, Reference Kundapur and Kodyalamoole 2016 ; Haorongbam et al ., Reference Haorongbam, Sathyanarayana and Dhanashree 2018 ), binge drinking 14–30% (Kundapur and Kodyalamoole, Reference Kundapur and Kodyalamoole 2016 ; Anandi et al ., Reference Anandi, Halgar, Reddy and Indupalli 2018 ) and ‘problem drinking’ (not defined) was 41.46% (Garg et al ., Reference Garg, Chavan, Singh and Bansal 2009 ). Among students of classes 8, 10 and 12 (12–19 years), 1.6% (2% males, 0% females) of lifetime users had alcohol dependence (Jaisoorya et al ., Reference Jaisoorya, Beena, Beena, Ellangovan, Jose, Thennarasu and Benegal 2016 ). In adolescent street children (11–19 years), 37% had AUD defined as recurrent substance use resulting in one or more of the following occurring in 12 months: failure to fulfil major role obligations at work or home leads to a physically hazardous situation, or causes legal problems (Gaidhane et al ., Reference Gaidhane, Syed Zahiruddin, Waghmare, Shanbhag, Zodpey and Joharapurkar 2008 ).

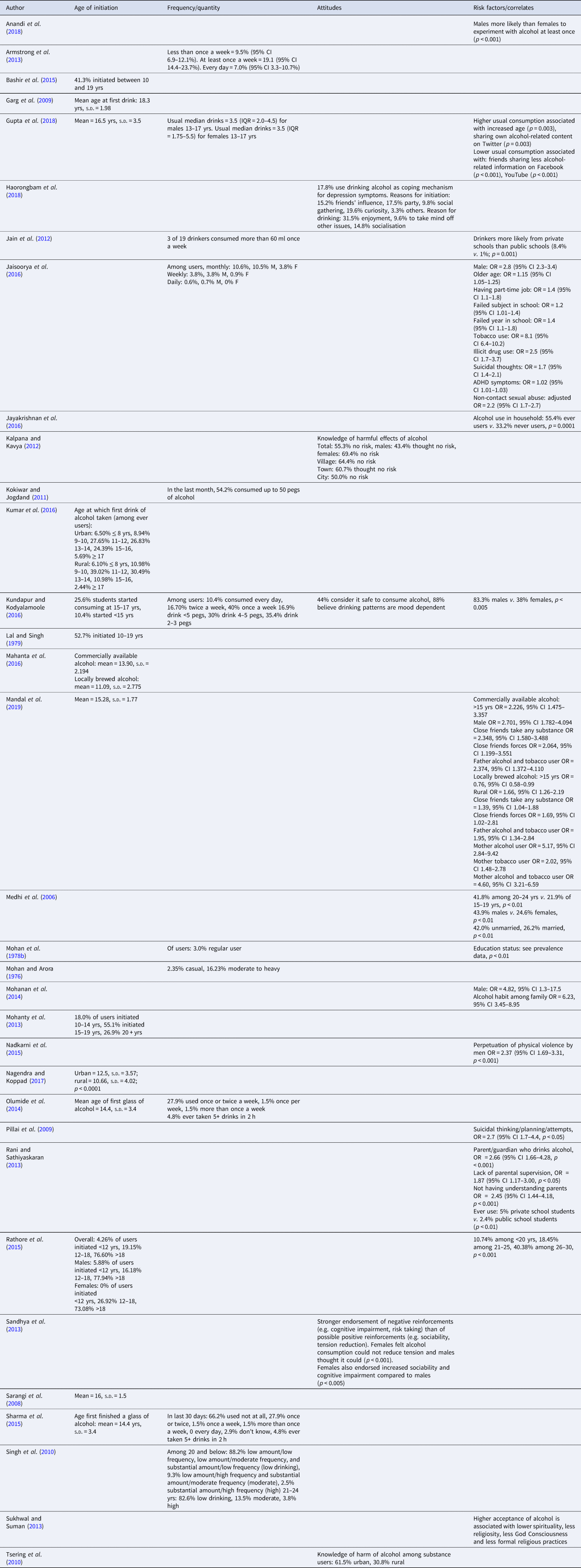

Patterns of drinking

Among drinkers, 0.6–10.4% consumed every day (Armstrong et al ., Reference Armstrong, Nuken, Samson, Singh, Jorm and Kermode 2013 ; Jaisoorya et al ., Reference Jaisoorya, Beena, Beena, Ellangovan, Jose, Thennarasu and Benegal 2016 ; Kundapur and Kodyalamoole, Reference Kundapur and Kodyalamoole 2016 ), 19.1–40% consumed at least once a week (Armstrong et al ., Reference Armstrong, Nuken, Samson, Singh, Jorm and Kermode 2013 ; Kundapur and Kodyalamoole, Reference Kundapur and Kodyalamoole 2016 ), 3.8% consumed weekly (Jaisoorya et al ., Reference Jaisoorya, Beena, Beena, Ellangovan, Jose, Thennarasu and Benegal 2016 ), 9.5% consumed less than once a week (Armstrong et al ., Reference Armstrong, Nuken, Samson, Singh, Jorm and Kermode 2013 ) and 10.6% consumed monthly (Jaisoorya et al ., Reference Jaisoorya, Beena, Beena, Ellangovan, Jose, Thennarasu and Benegal 2016 ) ( Table 3 ). Usual median number of drinks consumed among those between 13 and 17 years was 3.5 for both males and females (Gupta et al ., Reference Gupta, Lam, Pettigrew and Tait 2018 ). Among 10–19-year-old males from an urban slum over the past month, 54.2% consumed up to 50 ‘pegs’ of alcohol (Kokiwar and Jogdand, Reference Kokiwar and Jogdand 2011 ). Among males from a low-income community, in those between 18 and 20 years, 88.2% were ‘low drinking’ (low amount/low frequency, low amount/moderate frequency or substantial amount/low frequency), 9.3% were moderate drinking (low amount/high frequency or substantial amount/moderate frequency) and 2.5% were high drinking (substantial amount/high frequency); and in those between 20 and 24 years, 82.6% were low drinking, 13.5% were moderate drinking and 3.8% were high drinking (Singh et al ., Reference Singh, Schensul, Gupta, Maharana, Kremelberg and Berg 2010 ).

Table 3 Initiation of, attitudes towards, patterns of and correlates of drinking

Initiation age

The mean age for initiation of drinking ranged from 14.4 to 18.3 years ( Table 3 ). The mean age of initiation was significantly lower in rural areas compared to urban areas [10.66 ( s.d. 4.02) v . 12.5 ( s.d. 3.57); p < 0.0001] (Nagendra and Koppad, Reference Nagendra and Koppad 2017 ); and locally brewed alcohol [mean ( s.d. ) 11.09 (2.775)] was initiated at a younger age compared to commercially available alcohol in an industrial town [mean ( s.d. ) 13.90 (2.194)] (Mahanta et al ., Reference Mahanta, Mohapatra, Phukan and Mahanta 2016 ).

Among male substance use disorder patients at drug deaddiction centres, 41.3% had initiated alcohol use between 10 and 19 years (Bashir et al ., Reference Bashir, Sheikh, Bilques and Firdosi 2015 ). Among 22–23-year-old medical students, 25.6% had started consuming alcohol between 15 and 17 years, and 10.4% had started consuming alcohol before they were 15 years (Kundapur and Kodyalamoole, Reference Kundapur and Kodyalamoole 2016 ).

In students between 18 and 22 years, 18.0% had initiated drinking between 10 and 14 years, 55.1% had initiated between 15 and 19 years, and 26.9% after 19 years (Mohanty et al ., Reference Mohanty, Tripathy, Palo and Jena 2013 ). Among medical and dental students, 4.26% initiated before 12 years, 19.15% initiated between 12 and 18 years, and 76.60% initiated after 18 years (Rathore et al ., Reference Rathore, Pankaj, Mangal and Saini 2015 ). Comparing males and females, 5.88% males ( v . 0% females) initiated before 12 years, 16.18% ( v . 26.92%) initiated between 12 and 18 years, and 77.94% ( v . 73.08%) initiated after 18 years (Rathore et al ., Reference Rathore, Pankaj, Mangal and Saini 2015 ). Finally, comparing urban and rural drinkers, 6.50% urban drinkers ( v . 6.10% rural) initiated before 8 years, 8.94% ( v . 10.98%) initiated between 9 and 10 years, 27.65% ( v . 39.02%) initiated between 11 and 12 years, 26.83% ( v . 30.49%) initiated between 12 and 14 years, 24.39% ( v . 10.98%) initiated between 15 and 16 years, and 5.69% ( v . 2.44%) initiated after 17 years (Kumar et al ., Reference Kumar, Kumar, Shora, Dewan, Mengi and Razaq 2016 ).

Knowledge and attitudes

Overall, 55.3% of college-going students (17–21 years) believed that there was no risk of harmful effects of alcohol; with more females than males who believed that there was no risk (69.4% v . 43.4%); and a higher proportion from villages (64.4%) thought there was no risk as compared to those from towns (60.7%) or cities (50.0%) (Kalpana and Kavya, Reference Kalpana and Kavya 2012 ) ( Table 3 ). Among medical students (22–23 years), 44% considered it safe to consume alcohol, and 88% believe drinking patterns are mood-dependent (Kundapur and Kodyalamoole, Reference Kundapur and Kodyalamoole 2016 ).

In medical students (17–23 years), reasons for initiation of drinking included curiosity (19.6%), attending a party (17.5%), friends' influence (15.2%) and social gatherings (9.8%); and reasons for continued use included enjoyment (31.5%), as a coping mechanism for depressive symptoms (17.8%), socialisation (14.8%) and to take mind off other issues (9.6%) (Haorongbam et al ., Reference Haorongbam, Sathyanarayana and Dhanashree 2018 ). Among college-going students (mean age 16.7 years; s.d. 0.5) there was a stronger endorsement of negative reinforcements (e.g. cognitive impairment, risk taking) than of possible positive reinforcements (e.g. sociability, tension reduction); and compared to males, significantly more females felt alcohol consumption could not reduce tension and endorsed increased sociability and cognitive impairment (Sandhya et al ., Reference Sandhya, Carol, Kotian and Ganaraja 2013 ). Knowledge of harm of alcohol among substance users was greater in adolescents from urban than rural areas (61.5% v . 30.8%) (Tsering et al ., Reference Tsering, Pal and Dasgupta 2010 ).

Risk factors/correlates

The cross-sectional nature of the studies only allowed the examination of correlates of alcohol use ( Table 3 ). Alcohol consumption was associated with being male (Medhi et al ., Reference Medhi, Hazarika and Mahanta 2006 ; Mohanan et al ., Reference Mohanan, Swain, Sanah, Sharma and Ghosh 2014 ; Jaisoorya et al ., Reference Jaisoorya, Beena, Beena, Ellangovan, Jose, Thennarasu and Benegal 2016 ; Kundapur and Kodyalamoole, Reference Kundapur and Kodyalamoole 2016 ; Anandi et al ., Reference Anandi, Halgar, Reddy and Indupalli 2018 ; Mandal et al ., Reference Mandal, Parmar, Ambekar and Dhawan 2019 ), older age (Medhi et al ., Reference Medhi, Hazarika and Mahanta 2006 ; Rathore et al ., Reference Rathore, Pankaj, Mangal and Saini 2015 ; Jaisoorya et al ., Reference Jaisoorya, Beena, Beena, Ellangovan, Jose, Thennarasu and Benegal 2016 ; Gupta et al ., Reference Gupta, Lam, Pettigrew and Tait 2018 ; Mandal et al ., Reference Mandal, Parmar, Ambekar and Dhawan 2019 ) and going to private rather than public schools (Jain et al ., Reference Jain, Dhanawat, Kotian and Angeline 2012 ; Rani and Sathiyaskaran, Reference Rani and Sathiyaskaran 2013 ). Specifically for locally brewed alcohol, it was associated with younger age and rural residence (Mandal et al ., Reference Mandal, Parmar, Ambekar and Dhawan 2019 ). Alcohol consumption was associated with having a part-time job, and failing a subject or a year in school (Jaisoorya et al ., Reference Jaisoorya, Beena, Beena, Ellangovan, Jose, Thennarasu and Benegal 2016 ).

Alcohol use in adolescents was associated with parental/guardian's use of alcohol or tobacco, lack of parental supervision, and not having ‘understanding’ parents (Rani and Sathiyaskaran, Reference Rani and Sathiyaskaran 2013 ; Mohanan et al ., Reference Mohanan, Swain, Sanah, Sharma and Ghosh 2014 ; Jayakrishnan et al ., Reference Jayakrishnan, Geetha, Mohanan Nair, Thomas and Sebastian 2016 ; Mandal et al ., Reference Mandal, Parmar, Ambekar and Dhawan 2019 ). Alcohol use decreased with a decrease in the frequency of friends sharing alcohol-related information on Facebook and YouTube; and increased frequency of sharing personal alcohol-related content on Twitter was associated with an increase in alcohol use (Gupta et al ., Reference Gupta, Lam, Pettigrew and Tait 2018 ). Alcohol consumption was also associated with close friends using substances (any type) or peer pressure to drink alcohol (Mandal et al ., Reference Mandal, Parmar, Ambekar and Dhawan 2019 ).

Alcohol consumption was associated with tobacco use, illicit drug use, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) symptoms, suicidal thinking, planning and attempts, and non-contact sexual abuse and perpetuation of violence (Nadkarni et al ., Reference Nadkarni, Dean, Weiss and Patel 2015 ; Jaisoorya et al ., Reference Jaisoorya, Beena, Beena, Ellangovan, Jose, Thennarasu and Benegal 2016 ). Finally, higher acceptance of alcohol is associated with lower spirituality, less religiosity, less ‘God Consciousness’ and less formal religious practices (Sukhwal and Suman, Reference Sukhwal and Suman 2013 ).

Quality of reporting studies

In 42 of the 57 studies, there was appropriate reporting of more than 70% of the 22 STROBE criteria ( Appendix B ). Only one study reported on all the 22 criteria (Nadkarni et al ., Reference Nadkarni, Dean, Weiss and Patel 2015 ). For 15 of the 22 criteria, there was appropriate reporting in more than 70% of the studies. The poorest reporting was about study biases, generalisability of the findings, and role of the funder.

The existing evidence base has several limitations which preclude a robust synthesis and any conclusions we draw are, at best, exploratory in nature. Although the information about AUDs is relatively limited, the prevalence among drinkers appears to be high, and the patterns of drinking in a reasonably high proportion were suggestive of risky drinking (heavy drinking that puts the drinker at risk of developing problems), especially considering that this is a young population with a relatively short drinking history.

This is consistent with the steady rise in recorded alcohol consumption in most developing countries, albeit from relatively low base prevalence rates. It also parallels the increases in adult per capita consumption of alcohol and heavy episodic drinking that have been observed in India and other developing economies in east Asia, south Asia and southeast Asia (Shield et al ., Reference Shield, Manthey, Rylett, Probst, Wettlaufer, Parry and Rehm 2020 ). Amongst adolescents, the prevalence of current alcohol use in Sri Lanka was 3.4% (95% CI 2.6–4.3) (Senanayake et al ., Reference Senanayake, Gunawardena, Kumbukage, Wickramasnghe, Gunawardena, Lokubalasooriya and Peiris 2018 ), lifetime alcohol use in males was 45% (26% risky drinking) in Pakistan (Shahzad et al ., Reference Shahzad, Kliewer, Ali and Begum 2020 ), alcohol use was reported by 19% from traditional non-alcohol using ethnic groups and 40% from traditional alcohol using ethnic groups in Nepal (Parajuli et al ., Reference Parajuli, Macdonald and Jimba 2015 ), and 13% in Bhutan (Norbu and Perngparn, Reference Norbu and Perngparn 2014 ).

The data about patterns of drinking observed among adolescents in India are inconclusive but there appears to be some tendency towards heavy drinking. Among adolescents across several countries, there are consistent reports of binge drinking as a social norm among peer groups (Russell-Bennett et al ., Reference Russell-Bennett, Hogan and Perks 2010 ). The prevalence of binge drinking increases from age 15–19 years to the age of 20–24 years, and among drinkers, binge drinking is higher among the 15–19 years age group compared with the total population of drinkers (World Health Organization, 2018 ). This means that 15–24-year-old current drinkers often drink in heavy drinking sessions, and hence, except for the Eastern Mediterranean Region, the prevalence of such drinking among drinkers is high in adolescents (around 45–55%) (World Health Organization, 2018 ).

In India, the age of initiation commonly was mid- to late-teens; and male gender, rural residence and locally brewed alcohol were associated with earlier initiation of drinking. Across most of the world, initiation of alcohol use among adolescents takes place at an early age, usually before the age of 15 years. Among 15-year-olds, there is a high prevalence of alcohol use (50–70%) during the past 30 days in many countries of the Americas, Europe and Western Pacific; and the prevalence is relatively lower in African countries (10–30%) (World Health Organization, 2018 ). However, across the world, there is a huge variation in alcohol use among boys and girls of 15 years of age and vary from 1.2% to 74.0% in boys and 0% to 73.0% in girls (World Health Organization, 2018 ). Finally, with the strategic targeting of adolescents as alcohol consumers by the industry, increasing overall population prevalence and normalisation of drinking alcohol, and the increasing normalisation by virtue of learning more about how adolescents in other countries drink, one could speculate that the age of initiation would reduce and prevalence of alcohol consumption in adolescents in India would rise, in the coming years.

In India, knowledge about alcohol and its potential harms was limited in rural areas. The reasons for starting and continuing drinking were a mix of expected enhancement of positive experiences and dampening of negative affect. This is consistent with findings in Indian adults where alcohol consumption was seen to be mainly associated with expectations about reduction in psychosocial stress and providing pleasure (Nadkarni et al ., Reference Nadkarni, Dabholkar, McCambridge, Bhat, Kumar, Mohanraj and Patel 2013 ). Across the world, adolescents primarily report drinking for social motives or enjoyment – enjoyment (Argentina) (Jerez and Coviello, Reference Jerez and Coviello 1998 ), to make nights out more pleasurable (UK) (Plant et al ., Reference Plant, Bagnall and Foster 1990 ) and being social (Canada) (Kairouz et al ., Reference Kairouz, Gliksman, Demers and Adlaf 2002 ). Coping motives, on the other hand, are less common, but are associated with AUDs later in adulthood (Carpenter and Hasin, Reference Carpenter and Hasin 1999 ). The difference in drinking motives between adolescents from India (a mix of pleasure and coping) and other countries (primarily pleasure), and the similarity between reasons given by Indian adolescents and Indian adults, possibly reflect contextual/cultural differences and will have implications on transferability of interventions from other contexts and wider age-applicability of interventions developed for adults in India.