More money is not enough: The case for reconsidering federal special education funding formulas

Subscribe to the brown center on education policy newsletter, tammy kolbe , tammy kolbe principal researcher - air @takolbe elizabeth dhuey , and elizabeth dhuey associate professor - university of toronto sara menlove doutre sara menlove doutre senior program associate - wested.

October 3, 2022

Recently, Congress has showed a renewed interest, and possibly even the political will, to put federal appropriations for the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) on a glidepath toward “full funding.” From its inception in 1974, IDEA authorized federal funding for up to 40% of average per-pupil spending nationwide to pay a portion of what it costs to provide special education services for students with disabilities. Yet, in the more than four decades since the law was originally enacted, federal funding has never reached this target. In a change of course, for FY2023, Congress approved a 20% increase in appropriations for IDEA and there are strong signals that Congress plans to steadily grow appropriations in coming years .

Still, amidst anticipation for increased federal funding for special education, another important consideration has largely been overlooked: The formula used to determine how IDEA funds are allocated to states. IDEA’s funding formula is one of the law’s most critical components. Since the law’s inception, Congress has attempted to allocate IDEA appropriations to states according to each state’s share of children needing special education services.

That said, there are concerns that IDEA’s existing formula falls short of meeting policymakers’ expectations. In our recent work, we evaluated whether IDEA’s existing formula equitably distributes federal funding for special education among states and what will happen if the current formula is used to distribute potential future increases in IDEA appropriations . What we found is concerning.

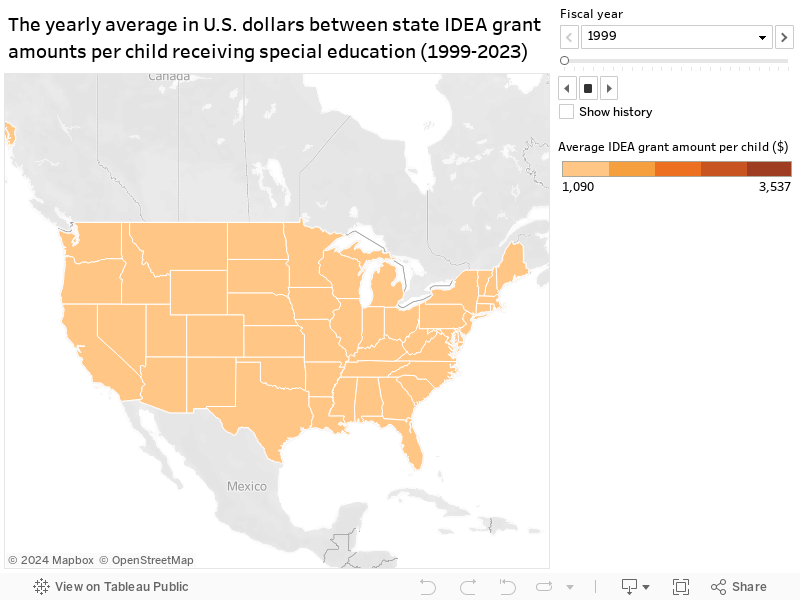

Disparities Among States in IDEA Funding

The existing formula generates substantial differences among states in the amount of federal funding available to pay for a child’s special education services, and these differences have grown over time. For FY2020, the difference in IDEA grant amounts between the states at the top and bottom of the distribution was about $1,442 per child; Wyoming received about $2,826 for each child receiving special education and Nevada received $1,384 per child (see Figure 1) . To put this difference in context, for that year federal IDEA funding covered about 23% of the national average additional cost of educating a student with a disability in Wyoming, whereas federal dollars covered about 11% of additional spending in Nevada.

Disparities among states in IDEA funding are systematic. Contrary to policymakers’ original intent, states with larger shares of children eligible for special education receive, on average, fewer dollars per child than other states with less need (Figure 2). In addition, large states and states with more children experiencing poverty also receive fewer IDEA dollars per child. Put differently, states that likely need at least as much and perhaps even more funding to meet higher levels of student need than other states, on average get fewer federal special education dollars for each child who receives special education services.

Predictions for the Future

We simulated the potential impact of two policy proposals on the distribution of IDEA funding among states: (1) a 20% increase in appropriations for IDEA; and (2) full funding for IDEA. In both instances, we demonstrated how increased IDEA appropriations may affect federal grants to states.

Policy simulations show that increasing IDEA appropriations without modifying the current formula will perpetuate existing disparities in federal grant amounts to states . For the first simulation, the difference between states with the most and least funding grew to $1,805 per child ($3,537 in Vermont vs. $1,732 in Nevada). Moving to “full funding” further increases the difference between the states at the top and bottom of the distribution to $4,331 per child ($8,408 in Vermont vs. $4,076 in Nevada).

Allocating proposed increases to IDEA appropriations using the existing formula also preserves the distributional patterns that systematically advantage and disadvantage certain types of states (Figure 2) . On average, states with the largest populations of children ages 3-21 will continue to receive fewer IDEA dollars per child. Similarly, states with larger shares of children experiencing poverty, children receiving special education, and non-White and Black children would on average receive smaller IDEA grants per child.

The Root of the Problem

Disparities among states in federal special education funding emerged after Congress changed IDEA’s funding formula at the law’s 1997 reauthorization. In FY1999, the year prior to when the formula change went into effect, the difference between the states at the top and bottom of the distribution was $155 per child eligible for special education; however, by FY2021 this gap widened to $1,511 per child (Figure 3).

It is the complex interplay among these multiple calculations and adjustments that prevents the existing formula from effectively distributing IDEA appropriations among states according to contemporary and future differences in need.

The FY1999 base became a static fixed amount that states receive each year rather than an amount that is recalibrated annually according to cross-state differences in need. In the years immediately following the formula change, there weren’t significant federal IDEA appropriations beyond states’ FY1999 base funding amount (Figure 4). However, as time passed, by fixing this portion of states’ IDEA grants in perpetuity, the distribution of federal dollars among states became increasingly disconnected from changes to states’ special education child count.

Finally, the formula’s adjustments that hold states “harmless” from substantial reductions in IDEA funding further undermine the population-poverty calculations’ capacity to effectively adjust for changes in states’ student population counts over time. Instead, the formula protects small states and states with declining student populations from possible reductions in IDEA dollars, and in doing so, prevents IDEA funding from being shifted to states with growing and increasingly diverse student populations.

More Money Is Not Enough

Policy proposals that would significantly increase federal funding for special education – including efforts to “fully fund” IDEA – bring a new sense of urgency to reconsidering the formula used to allocate IDEA appropriations. Simply adding dollars to existing IDEA appropriations without modifying the current formula works against IDEA’s promise to equalize educational opportunities for students with disabilities. Our research shows that states and the students receiving special education in those states have not equally benefited from federal appropriations for IDEA. Moving forward, achieving goals for equitably allocating IDEA funding will require changes to the formula used to calculate states’ grant allocations .

Related Content

Briana Ballis, Katelyn Heath

May 26, 2021

Elizabeth Setren, Nora Gordon

April 20, 2017

Nora Gordon

April 5, 2018

Education Access & Equity K-12 Education

Governance Studies

Brown Center on Education Policy

Phillip Levine

April 12, 2024

Hannah C. Kistler, Shaun M. Dougherty

April 9, 2024

Katharine Meyer, Rachel M. Perera, Michael Hansen

- Special Education Funding In Washington State

- Contact Information

Special Education

There are two primary sources of revenue to support special education services to students: basic education and special education. Each student receiving special education and related services is first and foremost a basic education student.

- State Special Education Formula

- Federal Special Education Formula

The state special education formula has two parts. The first part is for calculating funding for students ages 3–5 who are not enrolled in kindergarten and are eligible for and receiving special education services. The second part applies to students ages 5–21 who are eligible for and receiving special education services and enrolled in K–12.

Special education funding is in addition to, or in “excess” of, the full basic education allocation (BEA) available for any student. The result is that school districts have two primary sources of revenue to support special education services to students: basic education and special education.

The allocation for students with disabilities is indexed at 15 percent of the resident K–21 full time enrollment. The allocation for students with disabilities aged 3 to 5 and not yet enrolled in kindergarten is not indexed.

Special Education Allocation Formulas

For students ages 3–5 not enrolled in kindergarten.

The annual average headcount of students ages 3–5 who have not enrolled in kindergarten who are eligible for and receiving special education, multiplied by the district's BEA, multiplied by 1.2.

Your district has 10 students, ages 3–5 not enrolled in kindergarten, and eligible for special education services. Your district's BEA is $5,022.90 Your district receives $60,274.80

10 students * $5,022.90 * 1.2 = $60,274.80

For students ages 5-21 and enrolled in K–12

The annual average headcount of students eligible for and receiving special education services ages 5–21 and enrolled in K–12 multiplied by the district's BEA, multiplied by the special education cost multiplier rate of:

- Tier 1: 1.12 for students eligible for and receiving special education who spend 80 percent or more of their school day in general education settings.

- Tier 2: 1.06 for students eligible for and receiving special education who spend less than 80 percent of their school day in general education settings.

- The special education enrollment percent above 15% multiplied by the total of Tier 1 and Tier 2 divided by the special education enrollment percent equals apportionment payment.

Your district has 100 students with IEPs in Tier 1 Your district has 60 students with IEPs in Tier 2 Your district is over the 15% threshold by 1% Your district's BEA is $5,022.90 Your district's Fed Funds Integration Rate Per Student is $17.75

- Tier 1 Multiplier: 100 * ($5,022.90 * 1.12) – 17.75) = $560,789.80

- Tier 2 Multiplier: 60 * ($5,022.90 * 1.06) – 17.75) = $318,391.44

- Percent of Special Ed Students: (100 + 60) / 1,000 = 16.0%

- Percent over 15% threshold: 16.0% - 15% = 1%

- Excess funding: (($560,789.8 + $318,391.44)/16.0%) * 1% = $54,948.82

- Total Allocation: $560,789.8 + $318,391.44 - 54,948.82 = $824,232.42

State Special Education Funding For Districts

- Navigate to the Apportionment, Enrollment, and Fiscal Reports | OSPI

- On the Apportionment Web page, select Apportionment, District (CCDDD), then your district from the drop down menu in the center of the Web page

- Choose the Apportionment report, the current month is sorted at the top of the list

- Search for the 1191SE Special Education Report

For questions about state special education funding please contact the Apportionment Office at 360-725-6300.

Federal IDEA Part B funds are allocated to states and local districts on a census based formula of eligible children age 3–21 receiving special education and related services on the established count date.

Federal IDEA Part B funds

- Section 611 - for eligible students aged 3–21

- Section 619 - for eligible students aged 3–5

IDEA Part B Sections 611 & 619

IDEA Part B Sections 611 & 619 flow-through allocations to LEAs are based on three distribution factors:

- A BASE amount is allocated based on 75% of FY1999's federal grant for minimum flow-through required by Federal IDEA Statute;

- 85% of remaining funds are allocated on the basis of relative POPULATION of children aged 3–21. This is the previous year's October Enrollment of Public and Private Schools (final October Student Enrollment Report submitted to OSPI); and

- 15% of remaining funds are allocated based on POVERTY in which the previous year's October Free and Reduced School Lunch rates are used.

School District Allocation Tables

These tables detail the amount of federal funding each district received by school year.

- IDEA-B Sections 611 and 619 2023–24 FP 267 Allocations posted 9/7/2023

- IDEA-B Sections 611 and 619 2022–23 FP 267 Allocations posted 1/3/2023

- IDEA-B Sections 611 and 619 2021–22 Carryover into 2022–23 posted 1/3/2023

- IDEA-B ARP Sections 611 and 619 2021–22 Carryover into 2022–23 posted 1/4/2023

- IDEA-B Sections 611 and 619 2021–22 FP 267 Allocations posted 11/9/2021

- IDEA-B Sections 611 and 619 2021–22 FP 149 Allocations posted 7/2/2021

- IDEA-B Sections 611 and 619 2021–22 FP 156 Allocations for ESA Members posted 7/2/2021

Federal Special Education Funding

- Read the Use of Funds Bulletin (B047-19)

- Learn more about IDEA Section 611 and Section 619 Funds

- Contact OSPI, Special Education Operations at 360-725-6075.

Grant Award Notifications (GAN)

- FFY 2023 IDEA-B 611 GAN

- FFY 2023 IDEA-B 619 GAN

Tools & Templates

Excess cost.

- Federal Excess Cost Guidance Handbook (updated 1/27/23)

- 2022–23 Federal Excess Cost Template (updated 3/6/24)

- 2021–22 Federal Excess Cost Template (updated 2/10/23)

- 2020–21 Federal Excess Cost Template (posted 1/20/22)

- 2019–20 Federal Excess Cost Template (updated 02/01/21)

Federal Fund Application

- Form package 267 Hints and Tips

- Recorded walkthrough – Budgets and Page 1 (Assurances)

- Recorded walkthrough – Page 2 (Use of Funds/Spending Plans)

- Recorded walkthrough – Page 3 (Proportionate Share/Private Schools)

- Recorded walkthrough – Page 5 (Appendices)

Fiscal Monitoring

- Fiscal Monitoring Procedures Manual for Local Education Agencies (LEA) and Subrecipients

- Fiscal Monitoring Procedures Manual for Educational Service Districts (ESDs) and Subrecipients

- Washington Integrated System of Monitoring (WISM) Fiscal Risk Matrix (revised 9/7/2023) - This Excel document has been designed to assist LEA staff in assessing potential fiscal risk in the special education program.

Maintenance of Effort

- MOE 50% Adjustment Request (updated 11/1/2023)

- Allowable Exceptions and Adjustments to MOE (updated 2/21/2022)

- IDEA, Part B Local Educational Agency (LEA) Maintenance of Effort (MOE) Guidance Handbook (updated 12/27/22)

- Local Education Agency (LEA) Maintenance of Effort (MOE) Organizer from the Center for IDEA Fiscal Reporting (CIFR)

- LEA MOE Calculator (updated 9/5/2023)

Other Tools & Templates

- Comprehensive Coordinated Early Intervening Services (CCEIS) Resources Step-by-Step from the Center for IDEA Fiscal Reporting (CIFR)

- FAQ from the U.S. Department of Education on Appropriately Using Federal Funds for Conferences and Meetings

- Least Restrictive Environment (LRE) Verification Calculator (posted 2/10/2020)

- Participant Support Costs Preapproval Request Form

- Apportionment Reports Tips and Tricks

- Unlocking Federal and State program Funds to Support Student Success

- Artificial Intelligence (AI)

- Learning Standards

- Performance Assessments

- Resources and Laws

- K-12 Learning Standards

- Computer Science Grants

- Learning Standards and Best Practices for Instruction

- Comprehensive Literacy Plan (CLP)

- Strengthening Student Educational Outcomes (SSEO)

- Washington Reading Corps

- Assessments

- Environmental and Sustainability Literacy Plan

- Resources and Research

- About FEPPP

- Trainings and Events

- Committees, Meetings, and Rosters

- Partnership

- Resources and Links

- Legislation and Policy

- Laws & Resources

- ASB Frequently Asked Questions

- Comprehensive Sexual Health Education Implementation

- Sexual Health Education Standards Comparison

- 2023 Sexual Health Education Curriculum Review

- Sexual Health Curriculum Review Tools

- Training/Staff Development

- Math Graduation Requirements

- Family Resources

- Modeling Our World with Mathematics

- Modern Algebra 2

- Outdoor Education for All Program

- Grants, Resources, and Supports

- Professional Learning Network

- SEL Online Education Module

- Academic Learning is Social and Emotional: Integration Tools

- Washington-Developed SEL Resources

- Learning Standards & Graduation Requirements

- OSPI-Developed Social Studies Assessments

- Resources for K-12 Social Studies

- Civic Education

- Holocaust Education

- History Day Program Components

- Washington History Day and Partners

- Temperance and Good Citizenship Day

- Social Studies Grant Opportunities

- Social Studies Laws and Regulations

- Social Studies Cadre of Educators

- Social Studies Showcase

- Early Learning Curriculum

- Elementary Curriculum

- Middle School Unit 1C Washington State History—Medicine Creek Treaty of 1854

- High School Unit 1 Contemporary World Problems

- High School Unit 1 US History

- High School Unit 2 Contemporary World Problems

- High School Unit 2 US History

- High School Unit 3 Contemporary World Problems

- High School Unit 3 US History

- High School Unit 4 Contemporary World Problems

- High School Unit 4 US History

- High School Unit 5 US History

- High School Unit 6 US History

- Tribes within Washington State

- Implementation and Training

- Indigenous Historical Conceptual Framework

- Regional Learning Project Videos

- Language Proficiency Custom Testing

- Proficiency Assessment Options

- Credits & Testing for Students

- Testing Process For Districts

- Laws/Regulations

- Washington State Seal of Biliteracy

- Talking to Young People About Race, Racism, & Equity

- Open Educational Resources

- Course Design & Instructional Materials

- Reporting Instruction and Assessment

- Washington State Learning Standards Review

- High School and Beyond Plan

- Waivers and CIA

- Career Guidance Washington Lessons

- High School Transcripts

- Graduation Pathways

- Credit Requirements

- Career and College Readiness

- Family Connection

- Whole-child Assessment

- Early Learning Collaboration

- Training and Webinars

- WaKIDS Contacts

- Professional Development

- Calculator Policy

- ELA Assessment

- Smarter Balanced Tools for Teachers

- 1% Alternate Assessment Threshold

- Access Point Frameworks and Performance Tasks

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Scoring and Reporting

- INSIGHT Portal

- State Testing Frequently Asked Questions

- Achievement Level Descriptors

- Technical Reports

- Testing Statistics (Frequency Distribution)

- Scale Scores State Assessments

- Sample Score Reports

- Request to View Your Student’s Test

- ELP Annual Assessments

- English Language Proficiency Screeners

- Alternate ACCESS

- WIDA Consortium

- Trainings, Modules, and Presentations

- Assessment Resources

- Monitoring of State Assessments

- Principal Letter Templates

- NAEP State Results

- NAEP Publications

- Timelines & Calendar

- Approval Process

- Carl D. Perkins Act

- Program of Study and Career Clusters

- 21st Century Skills

- Career Connect Washington

- Methods of Administration (MOA)

- Statewide Course Equivalencies

- Work-Based Learning

- Skill Centers

- Federal Data Collection Forms

- Special Education Data Collection Summaries

- File a Community Complaint

- Special Education Due Process Hearing Decisions

- Request Mediation (Special Education)

- Request a Due Process Hearing

- Special Education Request Facilitation

- Early Childhood Outcomes (Indicator 7)

- Transition from Part C to Part B (Indicator 12)

- Preschool Least Restrictive Environment (LRE) - Indicator 6

- Behavior and Discipline

- Disagreements and Complaints about Special Education

- Eligibility for Special Education

- Evaluations

- How Special Education Works

- Individualized Education Program (IEP)

- Making a Referral for Special Education

- Need Assistance?

- Parent and Student Rights (Procedural Safeguards)

- Placement Decisions and the Least Restrictive Environment (LRE)

- Prior Written Notice

- Transition Services (Ages 16–21)

- What Is Special Education?

- Current Nonpublic Agencies

- Rulemaking and Public Comment

- Special Education WAC and Federal IDEA

- Personnel Qualifications Guidance

- Annual Determinations

- Model Forms for Services to Students in Special Education

- Self-Study and System Analysis

- Significant Disproportionality

- Washington Integrated System of Monitoring

- Technical Assistance

- Special Education Community Complaint Decisions

- State Needs Projects

- Mental Health Related Absences

- Attendance Awareness Materials

- Improving Attendance for Schools

- Attendance Resources

- Policies, Guidance, and Data Reporting

- District Truancy Liaison

- Building Bridges Grant Program

- GATE Equity Webinar Series

- Contact Us - CISL

- Course-Based Dual Credit

- Exam-Based Dual Credit

- Transitional Kindergarten

- Early Learning Resources

- Early Learning District Liaisons

- Early Learning Fellows Lead Contact List

- How the IPTN Works

- Menus of Best Practices & Strategies

- MTSS Events

- Integrated Student Support

- MTSS Components and Resources

- Ninth Grade Success

- Equity in Student Discipline

- Student Discipline Training

- Student Transfers

- Whole Child Initiative

- Continuous School Improvement Resources

- Migrant Education Health Program

- Migrant Education Parent Advisory Council

- Migrant Education Workshops and Webinars

- Migrant Education Student Resources

- TBIP Program Guidance

- WIDA Resources

- Dual Language Education and Resources

- Title III Services

- Family Communication Templates

- Webinars and Newsletters

- Migrant & Multilingual Education Program Directory

- Tribal Languages

- Types of Tribal Schools

- State-Tribal Education Compact Schools (STECs)

- Support for Indian Education and Culture

- Curriculum Support Materials

- Rules and Regulations

- Title VI Indian Education Programs — By District

- Native Educator Cultivation Program

- Tribal Consultation

- McKinney-Vento Act

- Liaison Training Update Webform

- Homeless Student Data and Legislative Reports

- Homeless Education Posters and Brochures for Outreach

- Resources for Homeless Children and Youth

- Interstate Compact for Military Children

- Foster Care Liaison Update

- Building Point of Contact Update Form

- State and Federal Requirements

- Foster Care Resources and Training

- Postsecondary Education for Foster Care

- Children and Families of Incarcerated Parents

- Project AWARE

- Youth Suicide Prevention, Intervention, & Postvention

- Best Practices & Resources

- Prevention/Intervention SAPISP Coordinators

- Behavioral Health Resources

- Continuity of Operations Plan (COOP)

- Digital/Internet Safety

- HIB Compliance Officers Contact List

- Student Threat Assessment

- School Safety and Security Staff

- Active Shooter

- Bomb Threat & Swatting

- Gangs in Schools

- School Drills

- Terrorism and Schools

- Weapons and Schools

- Youth-Centered Environmental Shift Program

- Erin's Law 2018 Curriculum Review

- Erin’s Law – House Bill 1539

- Allergies and Anaphylaxis

- Health Services Resources

- Immunizations

- School Nurse Corps

- Workforce Secondary Traumatic Stress

- 2021 COVID-19 Student Survey Results

- Healthy Youth Survey

- School Health Profiles

- Alternative Learning Experience

- Continuous Learning

- Graduation, Reality And Dual-Role Skills (GRADS)

- Guidance and Resources for Educators and Families

- HiCapPLUS Professional Learning Modules for Educators

- Home-Based Instruction

- Home/Hospital Instruction

- For Applicants

- For Schools & Districts

- Course Catalog

- Online Learning Approval Application

- Approved Online Schools and School Programs

- Approved Online Course Providers

- Getting Started Toolkit

- Open Doors Reports

- Washington's Education Options

- The Superintendent's High School Art Show

- Daniel J. Evans Civic Education Award for Students

- Washington State Honors Award

- Pre-Residency Clearance In-State Applicant

- Teacher College Recommendation

- Conditional Teacher Certificate - In-State

- Intern Substitute Certification In-State Applicants

- Emergency Substitute Certification In-State Applicants

- First Peoples' Language, Culture and Oral Traditions Certification

- Pre-Residency Clearance Out-of-State Applicant

- Residency Teacher Out-of-State

- Professional Teacher Out-of-State

- Substitute Teaching Out-of-State

- Conditional Teacher Out-of-State

- Intern Substitute Teacher Certificate Out-of-State

- Emergency Substitute Teacher Certification Out-of-State

- Foreign Trained Applicants Teacher Certification

- Residency Teacher Renewal

- Professional Teacher

- Transitional Teaching Certificate

- Conditional Teacher Certification

- Emergency Substitute Certificate

- First Peoples' Language, Culture and Oral Traditions Renewal

- Initial Teaching Certificate

- Standard/Continuing Teaching Certificate

- Provisional Teaching Certificate

- Upgrading Initial to Continuing

- Upgrade from Residency to Professional

- Converting Initial to Residency Teaching Certificate

- STEM Renewal Requirement for Teacher Certification

- Adding a CTE Certification Vocational Code (V-Code)

- Renewal of a Career and Technical Educator (CTE) Initial Certificate

- Renewal of a Career and Technical Educator (CTE) Continuing Certificate

- Career and Technical Educator Conditional Certificate

- Initial/Continuing CTE Career Guidance Specialist Certificate

- Career and Technical Educator (CTE) Director Certificate

- Washington State Certification - Frequently Asked Questions

- General Paraeducator

- English Language Learner Subject Matter

- Special Education Subject Matter

- Paraeducator First Time Applicant - Advanced Paraeducator

- English Language Learner Subject Matter Renewal

- Special Education Subject Matter Renewal

- Advanced Paraeducator Renewal

- Administrator College Recommendation

- Substitute Administrator Certificate In-State

- Conditional Administrator (Principals Only)

- Superintendent College Recommendation

- Residency Principal or Program Administrator

- Substitute Administrator Out-of-State

- Professional Principal or Program Administrator

- Initial Superintendent

- Professional Principal or Program Administrator Renewal

- Initial (Superintendent, Program Administrator, or Principal)

- Continuing (Superintendent, Program Administrator, Principal)

- Standard/Continuing Administrator Certificate

- Transitional Administrator Certificate

- Residency Principal and Program Administrator Upgrade to Professional

- Initial Upgrading to Continuing

- Initial Converting to Residency Administrator

- School Orientation and Mobility Specialist

- School Counselor First Time Applicant

- School Psychologist First Time

- School Nurse

- School Social Worker First Time

- School Occupational Therapist First Time

- School Physical Therapist First Time

- Speech Language Pathologist/Audiologist First Time

- School Behavior Analyst

- Substitute ESA

- School Behavior Analyst Renewal

- School Orientation and Mobility Specialist Renewal

- School Counselor Reissue and Renewal

- School Psychologist Reissue and Renewal Applicant

- School Nurse Renewal

- School Social Worker Renewal Applicant

- School Occupational Therapist Renewal

- School Physical Therapist Renewal Applicant

- Speech Language Pathologist/Audiologist Renewal Applicant

- Conditional ESA

- Transitional ESA Renewal

- Upgrade from Residency to Professional ESA

- Upgrade from Initial to Continuing ESA

- Converting Residency to Initial Applicant ESA

- Converting Initial to Residency ESA

- National Board Candidate FAQ

- OSPI National Board Conditional Loan

- Support National Board Candidates

- National Board Certification and Washington State Teaching Certificate

- National Board Candidate and NBCT Clock Hours

- Washington State National Board Certified Teacher Bonus

- National Board Cohort Facilitator

- National Board Certification Regional Coordinators

- Washington State National Board Certification - NBCT Spotlight

- Professional Certification Webinars and Presentations

- Regulations and Reports

- Helpful Links

- Certification-Forms

- Professional Certification Fee Schedule

- Fingerprint Office Locations

- Fingerprint Records Forms and Resources

- Fingerprint Records Alternatives for Applicants

- Fingerprint Records Private School Applicants

- Fingerprint Records Frequently Asked Questions

- International Education

- Washington State Recommended Core Competencies for Paraeducators

- Standards for Beginning Educator Induction

- Washington State Standards for Mentoring

- Mentor Foundational Opportunities

- Mentor Specialty Opportunities

- Mentor On-going Opportunities

- Induction Leader Opportunities

- Educator Clock Hour Information

- STEM Clock Hours

- Approved Providers

- Become an Approved Provider

- Department of Health License Hours as Clock Hours Information

- Comprehensive School Counseling Programs

- School Psychology

- School Social Work

- Laws, Regulations & Guidance

- Support & Training

- Teacher-Librarians

- School Library Programs - Standards and LIT Framework

- School Library Research and Reports

- Student Growth

- Research and Reports

- Training Modules

- AWSP Leadership Framework

- CEL 5D+ Instructional Framework

- Danielson Instructional Framework

- Marzano Instructional Framework

- CEL 5D+ Teacher Evaluation Rubric 3.0

- Charlotte Danielson’s Framework for Teaching

- Marzano’s Teacher Evaluation Model

- Washington State Fellows' Network

- NBCT Leadership Opportunities

- Teacher of the Year and Regional Winners

- History Teacher of the Year

- Winners' Gallery

- Presidential Awards for Excellence in Mathematics and Science Teaching (PAEMST)

- From Seed to Apple

- ESEA Distinguished Schools Award Program

- U.S. Department of Education Green Ribbon Schools

- Blue Ribbon Schools Program

- Notification of Discipline Actions

- Investigation Forms

- Investigations FAQ

- OSPI Reports to the Legislature

- Asset Preservation Program

- High-Performance School Buildings Program

- School District Organization

- School Facilities Construction Projects Funding

- Building Condition Assessment (BCA)

- Information and Condition of Schools (ICOS)

- Forms and Applications

- Small District Energy Assessment Grant

- Emergency Repair Pool Grant

- CTE Equipment Grant Program

- Health and Safety ADA Access Grants

- Healthy Kids-Healthy Schools Grants

- Skill Centers Capital Funding

- Lead in Water Remediation Grant

- Small School District Modernization Grant

- Urgent Repair Grant

- Regulations and Guidance

- Applying for Safety Net Funding

- Apportionment, Enrollment, and Fiscal Reports

- Apportionment Attachments

- Budget Preparations

- District Allocation of State Resources Portal

- Election Results for School Financing

- ESD Reports and Resources

- Tools and Forms

- ABFR Guidelines

- Accounting Manual

- EHB 2242 Accounting Changes

- EHB 2242 Guidance

- Enrollment Reporting

- Federal Allocations

- Indirect Cost Rates

- Personnel Reporting

- School Apportionment Staff

- 1801 Personnel Reports

- Financial Reporting Summary

- Organization and Financing of Washington Public Schools

- Personnel Summary Reports

- Property Tax Levies

- Training and Presentations

- Legislative Budget Requests

- 2022 Proviso Reports

- Washington State Innovates

- Washington State Common School Manual

- OER Project Grants

- Community-Based Organizations Grants

- Nita M. Lowey Grant Competition

- Program Guidance

- Balanced Calendar

- Beginning Educator Support Team Grants

- Ask a Question about the Citizen Complaint Process

- Professional Learning Opportunities for Title I, Part A and LAP

- Fiscal Guidance

- Digital Equity and Inclusion Grant

- Education Grant Management System (EGMS)

- Private School Participation in Federal Programs

- Public Notices & Waiver Requests to the U.S. Department of Education

- State Applications and Reports Submitted to U.S. Department of Education

- Washington School Improvement Framework

- Homeless Education Grants

- Allowable Costs

- Educator Equity Data Collection

- LifeSkills Training (LST) Substance Abuse Prevention Grants

- Rural Education Initiative

- Student Support and Academic Enrichment (Title IV, Part A)

- Washington School Climate Transformation Grant (SCTG)

- Federal Funding Contact Information

- CGA Contacts

- Meals for Washington Students

- Washington School Meals Application Finder

- At-Risk Afterschool Meals

- Family Day Care Home Providers/Sponsors

- Meal Patterns and Menu Planning

- CACFP Requirements and Materials

- Child and Adult Care Food Program Training

- Menu Planning and Meal Patterns

- Bulletins and Updates

- Summer Food Service Program Training

- Food Distribution

- Procurement

- Farm to Child Nutrition Programs

- Food Service Management Companies

- Claims, Fiscal Information and Resources

- Washington Integrated Nutrition System (WINS)

- Child Nutrition Program Reports

- Child Nutrition Grants

- EdTech Plan for K-12 Public Schools in Washington State

- IP Address Assignment

- School Technology Technical Support

- E-rate Program

- Computers 4 Kids (C4K)

- Digital Equity and Inclusion

- Legislation & Policies

- Media Literacy & Digital Citizenship Grants

- Best Practices

- State Technology Survey

- 2023-24 State Quote Specifications

- Student Transportation Allocation (STARS) Reports

- Instructor Training Programs

- CWU Training Program

- Publications and Bulletins

- Online School Bus Information System

- Online Bus Driver Certification

- Complaints and Concerns About Discrimination

- Information for Families: Civil Rights in Washington Schools

- Resources for School Districts

- Nondiscrimination Law & Policy

- Language Access

- Report Card

- Data Portal

- Data Administration

- Education Data System Administration (EDS)

- EDS Application User Guides

- Training and Materials

- District and School Resources

- Student Growth Percentiles FAQ

- Student Data Sharing

- Educator Data Sharing

- Protecting Student Privacy

- Discipline COVID-19 Data Display

- Monthly Enrollment and Absences Display

- Substitute Teachers Data

- K-12 Education Vision & McCleary Framework

- Use of the OSPI Logo

- Nondiscrimination Policy & Procedure

- Agency Leadership

- News Releases and Stories

- Special Projects

- Job Opportunities

- OSPI Interlocal Agreements

- Competitive Procurements

- Sole Source Contracts

- Accounting Manual Committee

- Children & Families of Incarcerated Parents Advisory Committee

- Committee of Practitioners (COP), Title I, Part A

- Publications and Reports

- Family Engagement Framework Workgroup

- GATE Partnership Advisory Committee

- Institutional Education Structure and Accountability Advisory Group

- K-12 Data Governance

- Language Access Advisory Committee

- Multilingual Education Advisory Committee

- Online Learning Advisory Committee

- Reopening Washington Schools 2020-21 Workgroup

- School Facilities Advisory Groups

- School Safety and Student Well-Being Advisory Committee Meetings

- Social Emotional Learning Advisory Committee

- Special Education Advisory Council (SEAC)

- Teacher Residency Technical Advisory Workgroup

- About Dyslexia

- Screening Tools and Best Practices

- Washington State Native American Education Advisory Committee (WSNAEAC)

- Work-Integrated Learning Advisory Committee

- African American Studies Workgroup

- Compensation Technical Working Group

- Ethnic Studies Advisory Committee

- Expanded Learning Opportunities Council

- K–12 Basic Education Compensation Advisory Committee

- Language Access Workgroup

- Race and Ethnicity Student Data Task Force

- Past Meeting Materials

- School Day Task Force

- Sexual Health Education Workgroup

- Staffing Enrichment Workgroup

- Student Discipline Task Force

- Transitional Bilingual Instruction Program (TBIP) Accountability Task Force

- OSPI Public Records Request

- How to File a Complaint

- Directions to OSPI

- Social Media Terms of Use

- 2023-24 School Breaks

- 180-Day School Year Waivers

- ESD Contact Info

- Maps & Applications

- Websites and Contact Info

- Web Accessibility Request Form

- Emergency Relief Funding Priorities

- State & Federal Funding

- School Employee Vaccination Data

- Washington’s Education Stimulus Funds

- Special Education Guidance for COVID-19

- Academic and Student Well-being Responses

- School Reopening Data

Make your reading count!

You Earned a Ticket!

Which school do you want to support?

- 1. Education is…

- 2. Students...

- 3. Teachers

- 4. Spending Time...

- 5. Places For Learning

- 6. The Right Stuff

- 7. And a System…

- 8. …with Resources…

- 10. So Now What?

Categorical funds: Special education and other exceptions

Yep, there are always exceptions..

The previous lesson explained California's school funding system, particularly the Local Control Funding Formula (LCFF) .

In This Lesson

What are the exceptions to lcff, how are special education funds allocated, how are school facilities funded, where does money come from in an emergency, are there secret funds for schools, ★ discussion guide.

This lesson focuses on the important funds that are not part of LCFF.

What are categorical funds?

In public education finance, funds that may only be used for specific purposes are known as categorical or restricted funds. They work kind of like coupons — valuable, but inflexible and a bit cumbersome to keep track of.

In many cases, categorical programs are connected with Federal funding. In other cases, they are created as temporary state-funded programs.

How does funding work for special education?

Federal law requires schools to provide "specially defined instruction, and related services… to meet the unique needs of a child with a disability." It's the biggest categorical program in education.

Approximately one of every eight students in California students is identified for Special Education services, an increase from one in ten in the early 2000s, driven significantly by autism. Most of these students require services that cost only modestly more than a normal program, but some students need intensive interventions that cost far more. The average cost of education for special ed students is more than double the norm.

Both federal and state laws require public schools to educate all students, including those with special needs. Categorical funds from the state and federal government are meant to support the cost of Special Education , but the categorical funds do not cover the full cost of providing these services. Much of the cost of providing special education falls to local school districts.

The federal government has a weak record when it comes to delivering on its commitments to fund special education. In 2018-19, federal funding for special education fell short by a whopping $3.2 billion , more than $4,000 per identified student. Local school districts are obligated to use their general purpose funding to make up the difference, effectively reducing the amount they have for their basic programs.

In a 2020 study, California Special Education Funding System , WestEd estimated that schools in California spent $13 billion on special education in 2018-19, and well over half came from local sources. During the 2021-22 school year, combined state and federal categorical funding covered about a third of the extra cost of special education. Roughly two-thirds of the additional special education costs were paid by local funding sources.

The state disburses categorical funds for special education to local consortia of schools and districts primarily based on the total student population in those schools, rather than an actual count of students with special needs. This is known as a census-based method. The consortia, called Special Education Local Planning Areas or SELPA s, develop local plans for allocating the funds to their districts and charter schools. The actual per-pupil amounts for each SELPA vary based on historical factors.

Federal funds cover about a tenth of the cost of special education

Special education funding is a lightning rod for complaints. Local districts say it costs them too much. Parents and teachers worry that students don’t get the services they should. And policymakers struggle to even make sense of how the system works. There is widespread agreement that the system needs to be rebuilt, but not strong agreement about how to do it. LCFF reform specifically excluded special education funding, leaving improvement of that part of the school funding system for another time. For more about special education, see Ed100 Lesson 2.7 .

How does funding work for school facilities?

With nearly 6 million school children and tens of thousands of buildings, facility costs are a substantial and ongoing expense that school district and state officials must plan for.

The money associated with building and renovating school facilities comes from a combination of local and (sometimes) state sources. These capital funds and expenses involve debt and depreciation, so the accounting is kept separately from the operational funds used to run the schools. This topic is explained in Ed100 Lesson 5.9: School Facilities .

Special programs and partnerships

Both the state and federal governments from time to time provide financial incentives to encourage K-12 schools to take actions or participate in programs.

For example, as part of the fiscal stimulus measures enacted under the Obama administration, the federal government created the Investing in Innovation Fund , better known as the i3 grants. These awards provided temporary funding to local education agencies and community-based organizations to test new ideas and demonstrate the value of new practices.

California officials perhaps took a page from the federal book when they set aside $250 million to encourage innovation in the area of career-technical education by creating the " California Career Pathways Trust ." The program awarded grants to schools and community colleges to work in partnership with local business to create new technical programs and curriculum. The Low Performing Schools block grant directed $300 million to schools with low results, subject to an application process and two rounds of reporting, one due in early 2019, the other in late 2021.

Emergency funds

Sometimes, California’s schools face special circumstances that require funding beyond what is allocated at the beginning of the fiscal year.

Covid-19 was an example. Because the pandemic imposed dramatic costs on California’s education system – distance learning required new technology and teacher training – spending on education spiked during the 2020-2021 school year.

During times of crisis, aid from the federal government is crucial. California's constitution requires a balanced budget. The federal government can take on debt, so it is far better equipped to expend large sums. The Coronavirus Aid, Recovery, and Economic Security ( CARES ) Act, passed in March of 2020, provided $30.75 billion to states for education. California increased education spending in 2020 in part by taking funds from other state programs. That strategy was only viable because Congress passed the American Rescue Plan , granting states the financial support they needed to respond to the calamity.

California schools feed all children

Food service is one of the oldest federal interventions in school systems. Meals are prepared or coordinated through schools, with the costs supported by a mix of federal, state and local funds. In 2022-23, California became the first state in the country to provide all students with free lunch.

More exceptions to come

The initial implementation of LCFF was a form of housecleaning. It purged the system of little categorical programs in favor of local control. Over time, categorical program exceptions will almost certainly re-blossom. Some will be framed as trial programs, or temporary investments. Many will be made separate from the Prop. 98 budget so that if the state budget has a bad year, it is somewhat easier to cut them without affecting ongoing core funding. This page on the Department of Education website is a good source for information about exceptions to the Local Control Funding Formula.

Of course none of these funds and programs are meaningful unless they ultimately benefit students, right? The next lesson examines how little we know about how funds are actually used.

Updated August 2017 February 2019 October 2021 September 2022

What can categorical funds be used for?

Answer the question correctly and earn a ticket. Learn More

Questions & Comments

To comment or reply, please sign in .

Jamie Kiffel-Alcheh November 30, 2019 at 8:04 pm

Caryn-c september 11, 2017 at 6:46 pm, jamie kiffel-alcheh november 30, 2019 at 8:05 pm, …with resources….

- …with Resources… Overview of Chapter 8

- Spending Does California Spend Enough on Education?

- Education Spending What can education dollars buy?

- Who Pays for Schools? Where California's Public School Funds Come From

- Prop 13 and Prop 98 Initiatives that shaped California's education system

- LCFF The formula that controls most school funding

- Categorical funds Special education and other exceptions

- School Funding How Money Reaches the Classroom

- Effectiveness Is Education Money Well Spent?

- More Money for Education What Are the Options?

- Parcel Taxes Only in California...

- Volunteers Hidden Treasure Trove for Schools

- There are no related lessons.

Sharing is caring!

Password reset.

Change your mind? Sign In.

Search all lesson and blog content here.

Not a member? Join now.

Login with Email

We will send your Login Link to your email address. Click on the link and you will be logged into Ed100. No more passwords to remember!

Share via Email

Or Create Account

Your Email Address

Ed100 Requires an Email Address

Language of Preference

Can't find school? Search by City or contact us . More than one school? Select the school of your youngest child enrolled in K-12. No School? Type "No School" and click the "Next" button.

Are you one of the leaders in a PTA, PTSA, PTO or Parent Group?

Great! Please tell us how you help:

You will be going to your first lesson in

Your Ed100 Team

Hmm. Looks like you are already a user. We can send you a link to log into your account.

Don't Miss Out!

Subscribe to the E-Bulletin for regular updates on research, free resources, solutions, and job postings from WestEd.

Subscribe Now

- Resources Home

- New Releases

- Top Downloads

- Webinar Archives

- Best Sellers

- Login / Create Account

Special Education Funding: Three Critical Moves State Policymakers Can Make to Maintain Funding and Bolster Performance

By Sara Menlove Doutre , Tammy Kolbe

Description

Special education takes up a large share of many states’ education budgets. When finances are tight, policymakers may look for options to limit or reduce the state’s share of special education spending.

However, unlike general education funds, state funding for special education operates in the context of a unique regulatory framework designed to protect the rights of students with disabilities. State and local education agencies are compelled by federal law to maintain funding levels and ensure a free and appropriate public education for students with disabilities. These rights cannot be waived, even in the midst of a fiscal crisis.

To provide guidance on how to navigate current fiscal challenges, this brief focuses on systemic reforms that can include integrating and coordinating programs for serving students with diverse learning needs, including students with and without disabilities, and developing new approaches for funding such integrated systems of support. The brief guides policymakers to reaffirm the state’s commitment to educating students with disabilities, to use state policy to promote early intervention and to coordinate services, and to leverage flexibility in using federal and state special education funds.

About This Series

The National Conference of State Legislatures (NCSL) has partnered with WestEd to publish a series of briefs summarizing the evidence and research on common school finance issues that arise during an economic downturn. Specifically, with the onset of an economic downturn, states face the prospect of reduced tax revenue available to fund public services, including public education. This series of briefs leverages what we know from evidence and research to present approaches that state policymakers may take to address these funding realities while supporting public education.

Also available from this series is, Loosening the Reins: Evidence and Considerations for Lifting Restrictions on Resources for Schools.

Resource Details

Product information, related resources.

Blending and Braiding Funds to Mitigate the Impact of COVID-19 on the Most Vulnerable Students

In this archived webinar, find out how you can apply the concepts of blending and braiding funds in K-12 education to support all students.

Managing Public Education Resources During the Coronavirus Crisis: Practical Tips and Considerations for School District Leaders

This brief offers practical information and guidance to help education leaders manage and allocate resources during and after the school closures and economic challenges caused by COVID-19.

Fair and Equitable Reductions to State Education Budgets: Evidence and Considerations for the 2020/21 Fiscal Year

In this paper, WestEd authors suggest three key strategies intended to help ensure that any cuts in education expenditures as a result of a likely recession are fair and equitable.

Stay Connected

Subscribe to the E-Bulletin and receive regular updates on research, free resources, solutions, and job postings from WestEd.

Your download will be available after you subscribe, or choose no thanks .

Ask a question, request information, make a suggestion, or sign up for our newsletter.

- WestEd Bulletin

- Insights & Impact

- Equity in Focus

- Areas of Work

- Charters & School Choice

- Comprehensive Assessment Solutions

- Culturally Responsive & Equitable Systems

- Early Childhood Development, Learning, and Well-Being

- Economic Mobility, Postsecondary, and Workforce Systems

- English Learner & Migrant Education Services

- Justice & Prevention

- Learning & Technology

- Mathematics Education

- Resilient and Healthy Schools and Communities

- School and District Transformation

- Special Education Policy and Practice

- Strategic Resource Allocation and Systems Planning

- Supporting and Sustaining Teachers

- Professional Development

- Research & Evaluation

- How We Can Help

- Reports & Publications

- Technical Assistance

- Technical Assistance Services

- Policy Analysis and Other Support

- R&D Alert

- Board of Directors

- Equity at WestEd

- WestEd Pressroom

- WestEd Offices

- Work with WestEd

Work at WestEd

- Donate/Ways To Give

Special Education Funding in Wisconsin

How it works and why it matters, february 2019.

One of the foremost fiscal challenges for state government and school districts throughout Wisconsin is the cost of providing special education.

School leaders from across the state testified at last year’s Blue Ribbon Commission on School Funding hearings on the acute fiscal strain caused by special education costs. Meanwhile, during his gubernatorial campaign, Governor Tony Evers called for a $1.4 billion boost in state K-12 education aid in the 2019-21 budget. His proposal included a $600 million increase for special education—the largest increase over the current budget of any other education line item by far.

Calls for additional resources stem from a growing gap between available state and federal funding for mandated special education and rising special education costs (which are considerably higher per pupil than general education costs). To satisfy the mandate, school districts are diverting resources away from programs intended to meet the needs of all students.

Recent state funding trends illustrate the dimensions of this financial challenge. Between the 2007-08 and 2017-18 school years, special education costs eligible for state aid increased by 18.3% to about $1.4 billion. At the same time, the state’s primary funding source has remained flat at far below aidable costs (i.e., those eligible for state reimbursement)—$369 million—for a decade. As a result, state funding of special education has fallen from 28.9% in 2007-08 to an estimated 24.5% in 2018-19 (and is down from a peak of 70% in 1973).

In the 2015-16 academic year, to pay for special education costs, school districts used more than $1.0 billion in resources that otherwise would have served all students. For two-thirds of Wisconsin school districts (283), this equates to 10% or more of resources available under their state-imposed per pupil revenue limits. These diversions appear to be especially prevalent in school districts serving high poverty, high minority schools, which raises equity concerns.

This report does not cover all aspects of Wisconsin’s system for financing special education. Rather, it looks at how the conflict between special education mandates and available funding drives a key fiscal challenge for Wisconsin’s policymakers and local education providers. Continue reading…

Media Coverage

How Fresno Unified is getting missing students back in class

How can we get more Black teachers in the classroom?

California college savings accounts aren’t getting to all the kids who need them

Patrick Acuña’s journey from prison to UC Irvine | Video

Family reunited after four years separated by Trump-era immigration policy

School choice advocate, CTA opponent Lance Christensen would be a very different state superintendent

Black teachers: How to recruit them and make them stay

Lessons in higher education: What California can learn

Keeping California public university options open

Superintendents: Well-paid and walking away

The debt to degree connection

College in prison: How earning a degree can lead to a new life

Is dual admission a solution to California’s broken transfer system?

April 24, 2024

March 21, 2024

Raising the curtain on Prop 28: Can arts education help transform California schools?

February 27, 2024

Keeping options open: Why most students aren’t eligible to apply to California’s public universities

Policy & Finance

Why special education funding will be more equitable under new state law

State to spend an additional $650 million on special education under new law.

Carolyn Jones

August 7, 2020.

California’s method of funding special education will become streamlined and a little more equitable, thanks to a provision in the recently passed state budget.

The 2020-21 budget fixes a decades-old quirk in the funding formula that had left vast differences between school districts in how much money schools received to educate special education students.

The old formula, created in the late 1970s and last updated in the early 2000s, based funding on how many students a district had overall, not just its number of students in special education. The result was that some districts received up to $800 extra per student per year to educate students in special education, while others received as little as $500.

The new formula adjusts some of those criteria, and brings districts at the lower end up to the state average of $625 per student per year. Districts that previously were receiving more will still get that same amount annually, so they won’t be penalized. To make up the difference, the state will be spending an additional $550 million on special education, plus an additional $100 million set aside for students with costly disabilities, such as genetic disorders that require specialized services.

“This is a very significant increase in special education funding. It’s the culmination of many years’ work,” said David Toston, associate superintendent of the El Dorado County Office of Education and chair of the California Advisory Commission on Special Education. “Considering the economy, we were bracing for the worst. I was very surprised and appreciative the (Newsom) administration was able to follow through on its commitment.”

The budget also includes funding to fix other wrinkles in California’s special education policy. It creates several workgroups to address key areas, such as alternative diploma pathways for students with disabilities. It also will address the sometimes-rocky transitions children make when they move to schools from regional disability centers, which provide programs for infants and toddlers, as well as from school to the California Department of Rehabilitation, which provides independent living and employment services for adults with disabilities.

It also sets aside $15 million to recruit and train special education teachers.

The new funding is part of a broader, multi-year state effort to tackle some long-standing hurdles to how schools provide special education, said Jason Willis, area director of strategic resource planning and implementation at WestEd, a research and technical assistance firm.

“California is trying to think about this holistically,” he said. “But right now, for administrators, this will offer a little relief, especially in an environment where the economy is struggling.”

Gov. Gavin Newsom, who has dyslexia, has long championed special education. In his May speech about his proposed budget revisions, he said the additional special education funding will be renewed annually.

“I care deeply about special education, and I could not in good conscience be part of dismantling of a commitment we had made well over a year ago to substantially improve special education in the state of California,” he said. “Nothing breaks my heart more than seeing people with physical and emotional disabilities, people so often left behind and forgotten, falling even further behind.”

He also acknowledged that the state has more work to do.

“We are not even close to where we need to be in terms of protecting those folks,” he said.

Carolynne Beno, a former director for the Yolo County Special Education Local Plan Area and an education lecturer at UC Davis, agreed that the additional funding is a good start, but not nearly enough to address schools’ growing needs.

She pointed out that while overall enrollment is declining in California, the number of children in special education is growing. In 2018-19, almost 800,000 California students — about 13% of overall K-12 enrollment — were enrolled in special education, receiving services for dyslexia, autism, emotional disorders, cerebral palsy and other conditions.

Schools are also seeing an increase in students with disabilities that are costly to address, such as severe autism, she said. And staffing shortages are forcing districts to hire outside workers, such as speech therapists and psychologists, which also adds to expenses.

“Consequently, despite the increased funding in the budget, students with disabilities and their families probably won’t see significant differences in the services they receive,” she said. “We need to remain committed to (making funding more equitable), funding for preschoolers with disabilities and additional funding for students with the most needs.”

She also noted that most families might not notice a difference in services because districts try to provide a full range of services regardless of how much money they receive from the state.

Special education funding in California has been a challenge for decades. When the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act passed in 1975, mandating that schools provide a free, appropriate education to all children, the federal government agreed to fund 40% of states’ special education costs. But federal spending has never reached that level, and in recent years has provided only about 15% of California’s costs. The remainder is covered by the state and local districts.

As the state navigates economic uncertainties caused by the pandemic, advocates for special education say they’re heartened that so far, programs for students with disabilities have been spared.

“It’s clear that this administration is making special education finance reforms a priority,” Willis, from WestEd, said. “That’s significant, especially as we’re walking into a recession.

To get more reports like this one, click here to sign up for EdSource’s no-cost daily email on latest developments in education.

Share Article

Comments (7)

Leave a comment, your email address will not be published. required fields are marked * *.

Click here to cancel reply.

XHTML: You can use these tags: <a href="" title=""> <abbr title=""> <acronym title=""> <b> <blockquote cite=""> <cite> <code> <del datetime=""> <em> <i> <q cite=""> <s> <strike> <strong>

Comments Policy

We welcome your comments. All comments are moderated for civility, relevance and other considerations. Click here for EdSource's Comments Policy .

Jonathan Goodwin 3 years ago 3 years ago

Special education needs to be improved. I was born in 1956; back then it was too easy they would not change it. It was too hard they wouldn’t change; it should be in the middle.

Todd Maddison 4 years ago 4 years ago

The issues around special ed funding are a good example of how we often fail to understand that all funding in our schools is interconnected. As they say in finance, money is “fungible”, meaning if I give you $10 to buy lunch and you put it in your bank account, it is then difficult to know if that $10 was actually spent on lunch, or on something else. When it comes to CA school funding, … Read More

The issues around special ed funding are a good example of how we often fail to understand that all funding in our schools is interconnected. As they say in finance, money is “fungible”, meaning if I give you $10 to buy lunch and you put it in your bank account, it is then difficult to know if that $10 was actually spent on lunch, or on something else.

When it comes to CA school funding, what we know, based on actual data is since we passed Prop 30 in 2012 school funding has literally skyrocketed.

According to the state’s SACS database, in 2012 total school funding was $9,656/ADA. In 2019 that was $14,983/ADA. That’s an increase of $5,327/ADA during this time, growth of 55.17% with a 6.48% compound annual growth rate.

During this same time, inflation in CA has averaged 2.37%/year, meaning school funding per ADA has risen at a rate almost 3 times faster than inflation.

Where has this money gone?

Not to special education, which has supposedly been recognized as a priority during this time.

Last November Edsource highlighted a state audit that found money being allocated for high-needs students “has not ensured that funding is benefiting students as intended”.

https://edsource.org/2019/state-audit-finds-education-money-not-serving-high-needs-students-calls-for-changes-in-funding-law/619504

Now… “high needs” is not necessarily all special education, but do we really think if our districts are not spending money specifically allocated to high needs students in ways that benefit them, special education is being handled differently?

In April 2019 the San Diego Union Tribune published a great study of special ed funding and it’s use in San Diego County districts. In their analysis, if we look at their numbers starting in 2012 also, we see that special ed funding has risen 26% (note they claim 32% in the text but that doesn’t match the math – going from $792M to $1B is a 26% increase…)

https://www.sandiegouniontribune.com/focus/story/2019-04-05/districts-struggle-with-rising-special-ed-costs

If we look at education funding for only San Diego County schools, using the same CDE data we see funding for all SD County districts has risen from $8,383/ADA in 2012 to $12,068/ADA in 2019 – a 43.96% increase. A rate of 6.26% per year.

It’s pretty obvious that if overall funding goes up 44% but special education funding only goes up 26%, the difference is being used elsewhere.

Most of education spending – typically over 80% and sometimes up to 90% in many districts – is on labor costs, pay and benefits for employees.

Complete data for 2019 is not yet available for San Diego County, but if we use the public pay data available through Transparent California for 2012 through 2018, a longitudinal analysis of that data shows a compound annual growth rate for pay alone of 5.17%, and for pay and benefits 6.39%.

That is, of course, even higher than the growth rate of total funding.

So it’s pretty clear that schools have no problem prioritizing increases in their own pay and benefits- at rates actually greater than their increase in funding, again almost three times faster than inflation, but not prioritizing special education funding.

And, before we hear “but they’re so underpaid, don’t they deserve higher raises?”, I need to point out that, again in San Diego county, in 2018 the total compensation for all full time employees of school districts was $94,907/year. For administrators that number is $156,214/year, for certificated staff $114,257/year.

I think we’re long past the era where education was a calling that required a vow of poverty supported by a pantry full of Top Ramen packets.

This is the real problem. It may have specific impact on special education as we see here, but it has general impact on everything we do in education.

Again, in San Diego County, if pay and benefit increases had been held to the rate of inflation, there would be $1.3 billion dollars available for education there overall.

We’ve heard much about the financial difficulties school districts were having even prior to the Covid crises. Again from the Union-Tribune, an article in February 2020 headlined “Nearly every San Diego County school district may be spending more than it can afford” details some of that distress.

https://www.sandiegouniontribune.com/news/education/story/2020-02-09/nearly-every-san-diego-county-school-district-is-spending-more-than-they-have-or-they-will-be

Can we see why? It seems pretty obvious.

John Fensterwald 4 years ago 4 years ago

Todd, Thanks for your comment. I write not to argue but to clarify two points. By making your comparison starting with 2012, you are choosing the low point in funding during the last recession. Funding that year was down $9 billion from 2007-08. There had been substantial layoffs, and districts restored positions. See this graph; ignore the red -- the slide was prepared to make a separate point for another article I wrote. Second, special education … Read More

Thanks for your comment. I write not to argue but to clarify two points.

By making your comparison starting with 2012, you are choosing the low point in funding during the last recession. Funding that year was down $9 billion from 2007-08. There had been substantial layoffs, and districts restored positions. See this graph; ignore the red — the slide was prepared to make a separate point for another article I wrote.

Second, special education students are entitled under federal and state laws to whatever funding is needed to provide them with a free and appropriate public education. That’s important to keep in mind when making comparisons between what is spent for other students. Courts have decided that the Legislature decides what is adequate funding, and that can change yearly based on their funding choices.

Tim Morgan (personal viewpoint only) 4 years ago 4 years ago

Since when would removal of a windfall, only prospectively, constitute a penalty? Any reason to think Serrano v. Priest should not apply to state special ed funding?

Bo Loney 4 years ago 4 years ago

Governor Newsom's story is inspiring. I've read a little about his journey and have loved watching his daily well researched briefings. I wonder if Edsource can have him for a podcast or article with questions about how the adversity of dyslexia ultimately strengthened his gifts and helps with his career? I would like to know his perspective and inner thoughts as a child while in school. I feel like he … Read More

Governor Newsom’s story is inspiring. I’ve read a little about his journey and have loved watching his daily well researched briefings. I wonder if Edsource can have him for a podcast or article with questions about how the adversity of dyslexia ultimately strengthened his gifts and helps with his career?

I would like to know his perspective and inner thoughts as a child while in school. I feel like he could give a voice to students with learning differences and would his could be uplifting story for all students facing the myriad of diverse hurdles and adversities.

Demetrio 4 years ago 4 years ago

Newsome’s career was made possible by his rich patrons–the Getty family.

Robert Bartlett 4 years ago 4 years ago

The coverage of financial issues regarding special education was really helpful. Over the past couple of years, it has seemed like special education services are operating in a climate of austerity, and this scarcity is leading to a lot of ethical breaches by school administrators who apparently see disabled children as adversaries. It's great to hear Governor Newsom depict special education services as important to the state. Of all the officials that I have worked … Read More

The coverage of financial issues regarding special education was really helpful. Over the past couple of years, it has seemed like special education services are operating in a climate of austerity, and this scarcity is leading to a lot of ethical breaches by school administrators who apparently see disabled children as adversaries.

It’s great to hear Governor Newsom depict special education services as important to the state. Of all the officials that I have worked with over the past 16 years as a highly-qualified California special education teacher, he is the first and only one to do so. If Governor Newsom actually knew the full extent of the intellectual bigotry operating in his state’s school system, he might be calling for an end to a human-rights crisis. It’s not just fine tuning that is needed. Children are being seriously neglected and even mistreated at every level of the system.

EdSource Special Reports

Bill to mandate ‘science of reading’ in California classrooms dies

A bill to mandate use of the method will not advance in the Legislature this year in the face of teachers union opposition.

Interactive Map: Chronic absenteeism up in nearly a third of 930 California districts

Nearly a third of the 930 districts statewide that reported data had a higher rate of chronic absenteeism in 2022-23 than the year before.

Bill to mandate ‘science of reading’ in California schools faces teachers union opposition

The move puts the fate of AB 2222 in question, but supporters insist that there is room to negotiate changes that can help tackle the state’s literacy crisis.

California, districts try to recruit and retain Black teachers; advocates say more should be done

In the last five years, state lawmakers have made earning a credential easier and more affordable, and have offered incentives for school staff to become teachers.

EdSource in your inbox!

Stay ahead of the latest developments on education in California and nationally from early childhood to college and beyond. Sign up for EdSource’s no-cost daily email.

Stay informed with our daily newsletter

Kansas Senate rejects K-12 schools budget changing special education spending calculations

The Kansas Senate blocked a budget for K-12 schools on Thursday after intense opposition from public education groups.

The Kansas Senate voted 12 to 26 to reject a proposed budget that fully funded schools, and provided $77.5 million in new funding for special education but altered the way the state calculates special education spending. The House had narrowly approved the bill earlier in the day.

Key public education advocates, including the Kansas Association of School Boards and the Kansas National Educators Association, the state’s largest teachers union, had opposed the measure, arguing it amounted to an accounting trick that denied schools the funding for disabled students they desperately need.

“This bill does not include a long-range plan to fully fund special education. Instead, it offers a one-time $77 million increase, along with a series of accounting gimmicks to falsely promise that Special Education will be fully funded in the future,” the groups said in a statement Wednesday.

The bill’s failure likely means the Legislature will start a weeks-long break on Friday without passing funding for public schools.

In recent years public education advocates have loudly called for a massive increase in special education funding. Democratic Gov. Laura Kelly proposed such an influx – a $375 million increase over the next five years in $75 million installments.

Instead, the bill Republicans crafted allocated $77.5 million in new funds while counting local discretionary dollars as a portion of the state’s special education spending – an accounting maneuver that may bring Kansas into compliance with spending requirements without significant funding increases.

Several Republicans joined Democrats in rejecting the bill, arguing it harms their local school districts that depend on that funding and would create an excuse for the Legislature to underfund special education in the future.

Rep. Bill Cliffford, a Garden City Republican, opposed the bill and referred to the alterations in the special education formula as “a shell game.”

“Certainly my school districts would be negatively impacted at some point,” he said.

Senate Democrats spoke against the bill, arguing it was understudied and could harm districts across the state. “That is something we all need to be concerned about,” Sen. Cindy Holscher, an Overland Park Democrat, said.

Republican proponents had argued those funds were meant for special education students and should be spent in that manner.

“For the last seven years the LOB money that has been generated off of the excess costs of special education students has gone not into the special education fund where it should rightly go but it has gone into the general fund or the athletic fund or the increase the salary for the superintendent fund,” Rep. Scott Hill, an Abilene Republican said.

“Increasing our responsibility for special ed and at the same time cleaning up what local districts do with special ed money makes sense.”