Child Growth and Development

(12 reviews)

Jennifer Paris

Antoinette Ricardo

Dawn Rymond

Alexa Johnson

Copyright Year: 2018

Last Update: 2019

Publisher: College of the Canyons

Language: English

Formats Available

Conditions of use.

Learn more about reviews.

Reviewed by Mistie Potts, Assistant Professor, Manchester University on 11/22/22

This text covers some topics with more detail than necessary (e.g., detailing infant urination) yet it lacks comprehensiveness in a few areas that may need revision. For example, the text discusses issues with vaccines and offers a 2018 vaccine... read more

Comprehensiveness rating: 4 see less

This text covers some topics with more detail than necessary (e.g., detailing infant urination) yet it lacks comprehensiveness in a few areas that may need revision. For example, the text discusses issues with vaccines and offers a 2018 vaccine schedule for infants. The text brushes over “commonly circulated concerns” regarding vaccines and dispels these with statements about the small number of antigens a body receives through vaccines versus the numerous antigens the body normally encounters. With changes in vaccines currently offered, shifting CDC viewpoints on recommendations, and changing requirements for vaccine regulations among vaccine producers, the authors will need to revisit this information to comprehensively address all recommended vaccines, potential risks, and side effects among other topics in the current zeitgeist of our world.

Content Accuracy rating: 3

At face level, the content shared within this book appears accurate. It would be a great task to individually check each in-text citation and determine relevance, credibility and accuracy. It is notable that many of the citations, although this text was updated in 2019, remain outdated. Authors could update many of the in-text citations for current references. For example, multiple in-text citations refer to the March of Dimes and many are dated from 2012 or 2015. To increase content accuracy, authors should consider revisiting their content and current citations to determine if these continue to be the most relevant sources or if revisions are necessary. Finally, readers could benefit from a reference list in this textbook. With multiple in-text citations throughout the book, it is surprising no reference list is provided.

Relevance/Longevity rating: 4

This text would be ideal for an introduction to child development course and could possibly be used in a high school dual credit or beginning undergraduate course or certificate program such as a CDA. The outdated citations and formatting in APA 6th edition cry out for updating. Putting those aside, the content provides a solid base for learners interested in pursuing educational domains/careers relevant to child development. Certain issues (i.e., romantic relationships in adolescence, sexual orientation, and vaccination) may need to be revisited and updated, or instructors using this text will need to include supplemental information to provide students with current research findings and changes in these areas.

Clarity rating: 4

The text reads like an encyclopedia entry. It provides bold print headers and brief definitions with a few examples. Sprinkled throughout the text are helpful photographs with captions describing the images. The words chosen in the text are relatable to most high school or undergraduate level readers and do not burden the reader with expert level academic vocabulary. The layout of the text and images is simple and repetitive with photographs complementing the text entries. This allows the reader to focus their concentration on comprehension rather than deciphering a more confusing format. An index where readers could go back and search for certain terms within the textbook would be helpful. Additionally, a glossary of key terms would add clarity to this textbook.

Consistency rating: 5

Chapters appear in a similar layout throughout the textbook. The reader can anticipate the flow of the text and easily identify important terms. Authors utilized familiar headings in each chapter providing consistency to the reader.

Modularity rating: 4

Given the repetitive structure and the layout of the topics by developmental issues (physical, social emotional) the book could be divided into sections or modules. It would be easier if infancy and fetal development were more clearly distinct and stages of infant development more clearly defined, however the book could still be approached in sections or modules.

Organization/Structure/Flow rating: 4

The text is organized in a logical way when we consider our own developmental trajectories. For this reason, readers learning about these topics can easily relate to the flow of topics as they are presented throughout the book. However, when attempting to find certain topics, the reader must consider what part of development that topic may inhabit and then turn to the portion of the book aligned with that developmental issue. To ease the organization and improve readability as a reference book, authors could implement an index in the back of the book. With an index by topic, readers could quickly turn to pages covering specific topics of interest. Additionally, the text structure could be improved by providing some guiding questions or reflection prompts for readers. This would provide signals for readers to stop and think about their comprehension of the material and would also benefit instructors using this textbook in classroom settings.

Interface rating: 4

The online interface for this textbook did not hinder readability or comprehension of the text. All information including photographs, charts, and diagrams appeared to be clearly depicted within this interface. To ease reading this text online authors should create a live table of contents with bookmarks to the beginning of chapters. This book does not offer such links and therefore the reader must scroll through the pdf to find each chapter or topic.

Grammatical Errors rating: 5

No grammatical errors were found in reviewing this textbook.

Cultural Relevance rating: 3

Cultural diversity is represented throughout this text by way of the topics described and the images selected. The authors provide various perspectives that individuals or groups from multiple cultures may resonate with including parenting styles, developmental trajectories, sexuality, approaches to feeding infants, and the social emotional development of children. This text could expand in the realm of cultural diversity by addressing current issues regarding many of the hot topics in our society. Additionally, this textbook could include other types of cultural diversity aside from geographical location (e.g., religion-based or ability-based differences).

While this text lacks some of the features I would appreciate as an instructor (e.g., study guides, review questions, prompts for critical thinking/reflection) and it does not contain an index or glossary, it would be appropriate as an accessible resource for an introduction to child development. Students could easily access this text and find reliable and easily readable information to build basic content knowledge in this domain.

Reviewed by Caroline Taylor, Instructor, Virginia Tech on 12/30/21

Each chapter is comprehensively described and organized by the period of development. Although infancy and toddlerhood are grouped together, they are logically organized and discussed within each chapter. One helpful addition that would largely... read more

Each chapter is comprehensively described and organized by the period of development. Although infancy and toddlerhood are grouped together, they are logically organized and discussed within each chapter. One helpful addition that would largely contribute to the comprehensiveness is a glossary of terms at the end of the text.

From my reading, the content is accurate and unbiased. However, it is difficult to confidently respond due to a lack of references. It is sometimes clear where the information came from, but when I followed one link to a citation the link was to another textbook. There are many citations embedded within the text, but it would be beneficial (and helpful for further reading) to have a list of references at the end of each chapter. The references used within the text are also older, so implementing updated references would also enhance accuracy. If used for a course, instructors will need to supplement the textbook readings with other materials.

This text can be implemented for many semesters to come, though as previously discussed, further readings and updated materials can be used to supplement this text. It provides a good foundation for students to read prior to lectures.

Clarity rating: 5

This text is unique in its writing style for a textbook. It is written in a way that is easily accessible to students and is also engaging. The text doesn't overly use jargon or provide complex, long-winded examples. The examples used are clear and concise. Many key terms are in bold which is helpful to the reader.

For the terms that are in bold, it would be helpful to have a definition of the term listed separately on the page within the side margins, as well as include the definition in a glossary at the end.

Each period of development is consistently described by first addressing physical development, cognitive development, and then social-emotional development.

Modularity rating: 5

This text is easily divisible to assign to students. There were few (if any) large blocks of texts without subheadings, graphs, or images. This feature not only improves modularity but also promotes engagement with the reading.

Organization/Structure/Flow rating: 5

The organization of the text flows logically. I appreciate the order of the topics, which are clearly described in the first chapter by each period of development. Although infancy and toddlerhood are grouped into one period of development, development is appropriately described for both infants and toddlers. Key theories are discussed for infants and toddlers and clearly presented for the appropriate age.

Interface rating: 5

There were no significant interface issues. No images or charts were distorted.

It would be helpful to the reader if the table of contents included a navigation option, but this doesn't detract from the overall interface.

I did not see any grammatical errors.

This text includes some cultural examples across each area of development, such as differences in first words, parenting styles, personalities, and attachments styles (to list a few). The photos included throughout the text are inclusive of various family styles, races, and ethnicities. This text could implement more cultural components, but does include some cultural examples. Again, instructors can supplement more cultural examples to bolster the reading.

This text is a great introductory text for students. The text is written in a fun, approachable way for students. Though the text is not as interactive (e.g., further reading suggestions, list of references, discussion points at the end of each chapter, etc.), this is a great resource to cover development that is open access.

Reviewed by Charlotte Wilinsky, Assistant Professor of Psychology, Holyoke Community College on 6/29/21

This text is very thorough in its coverage of child and adolescent development. Important theories and frameworks in developmental psychology are discussed in appropriate depth. There is no glossary of terms at the end of the text, but I do not... read more

Comprehensiveness rating: 5 see less

This text is very thorough in its coverage of child and adolescent development. Important theories and frameworks in developmental psychology are discussed in appropriate depth. There is no glossary of terms at the end of the text, but I do not think this really hurts its comprehensiveness.

Content Accuracy rating: 5

The citations throughout the textbook help to ensure its accuracy. However, the text could benefit from additional references to recent empirical studies in the developmental field.

It seems as if updates to this textbook will be relatively easy and straightforward to implement given how well organized the text is and its numerous sections and subsections. For example, a recent narrative review was published on the effects of corporal punishment (Heilmann et al., 2021). The addition of a reference to this review, and other more recent work on spanking and other forms of corporal punishment, could serve to update the text's section on spanking (pp. 223-224; p. 418).

The text is very clear and easily understandable.

Consistency rating: 4

There do not appear to be any inconsistencies in the text. The lack of a glossary at the end of the text may be a limitation in this area, however, since glossaries can help with consistent use of language or clarify when different terms are used.

This textbook does an excellent job of dividing up and organizing its chapters. For example, chapters start with bulleted objectives and end with a bulleted conclusion section. Within each chapter, there are many headings and subheadings, making it easy for the reader to methodically read through the chapter or quickly identify a section of interest. This would also assist in assigning reading on specific topics. Additionally, the text is broken up by relevant photos, charts, graphs, and diagrams, depending on the topic being discussed.

This textbook takes a chronological approach. The broad developmental stages covered include, in order, birth and the newborn, infancy and toddlerhood, early childhood, middle childhood, and adolescence. Starting with the infancy and toddlerhood stage, physical, cognitive, and social emotional development are covered.

There are no interface issues with this textbook. It is easily accessible as a PDF file. Images are clear and there is no distortion apparent.

I did not notice any grammatical errors.

Cultural Relevance rating: 4

This text does a good job of including content relevant to different cultures and backgrounds. One example of this is in the "Cultural Influences on Parenting Styles" subsection (p. 222). Here the authors discuss how socioeconomic status and cultural background can affect parenting styles. Including references to specific studies could further strengthen this section, and, more broadly, additional specific examples grounded in research could help to fortify similar sections focused on cultural differences.

Overall, I think this is a terrific resource for a child and adolescent development course. It is user-friendly and comprehensive.

Reviewed by Lois Pribble, Lecturer, University of Oregon on 6/14/21

This book provides a really thorough overview of the different stages of development, key theories of child development and in-depth information about developmental domains. read more

This book provides a really thorough overview of the different stages of development, key theories of child development and in-depth information about developmental domains.

The book provides accurate information, emphasizes using data based on scientific research, and is stated in a non-biased fashion.

Relevance/Longevity rating: 5

The book is relevant and provides up-to-date information. There are areas where updates will need to be made as research and practices change (e.g., autism information), but it is written in a way where updates should be easy to make as needed.

The book is clear and easy to read. It is well organized.

Good consistency in format and language.

It would be very easy to assign students certain chapters to read based on content such as theory, developmental stages, or developmental domains.

Very well organized.

Clear and easy to follow.

I did not find any grammatical errors.

Cultural Relevance rating: 5

General content related to culture was infused throughout the book. The pictures used were of children and families from a variety of cultures.

This book provides a very thorough introduction to child development, emphasizing child development theories, stages of development, and developmental domains.

Reviewed by Nancy Pynchon, Adjunct Faculty, Middlesex Community College on 4/14/21

Overall this textbook is comprehensive of all aspects of children's development. It provided a brief introduction to the different relevant theorists of childhood development . read more

Overall this textbook is comprehensive of all aspects of children's development. It provided a brief introduction to the different relevant theorists of childhood development .

Content Accuracy rating: 4

Most of the information is accurately written, there is some outdated references, for example: Many adults can remember being spanked as a child. This method of discipline continues to be endorsed by the majority of parents (Smith, 2012). It seems as though there may be more current research on parent's methods of discipline as this information is 10 years old. (page 223).

The content was current with the terminology used.

Easy to follow the references made in the chapters.

Each chapter covers the different stages of development and includes the theories of each stage with guided information for each age group.

The formatting of the book makes it reader friendly and easy to follow the content.

Very consistent from chapter to chapter.

Provided a lot of charts and references within each chapter.

Formatted and written concisely.

Included several different references to diversity in the chapters.

There was no glossary at the end of the book and there were no vignettes or reflective thinking scenarios in the chapters. Overall it was a well written book on child development which covered infancy through adolescents.

Reviewed by Deborah Murphy, Full Time Instructor, Rogue Community College on 1/11/21

The text is excellent for its content and presentation. The only criticism is that neither an index nor a glossary are provided. read more

Comprehensiveness rating: 3 see less

The text is excellent for its content and presentation. The only criticism is that neither an index nor a glossary are provided.

The material seems very accurate and current. It is well written. It is very professionally done and is accessible to students.

This text addresses topics that will serve this field in positive ways that should be able to address the needs of students and instructors for the next several years.

Complex concepts are delivered accurately and are still accessible for students . Figures and tables complement the text . Terms are explained and are embedded in the text, not in a glossary. I do think indices and glossaries are helpful tools. Terminology is highlighted with bold fonts to accentuate definitions.

Yes the text is consistent in its format. As this is a text on Child Development it consistently addresses each developmental domain and then repeats the sequence for each age group in childhood. It is very logically presented.

Yes this text is definitely divisible. This text addresses development from conception to adolescents. For the community college course that my department wants to use it is very adaptable. Our course ends at middle school age development; our courses are offered on a quarter system. This text is adaptable for the content and our term time schedule.

This text book flows very clearly from Basic principles to Conception. It then divides each stage of development into Physical, Cognitive and Social Emotional development. Those concepts and information are then repeated for each stage of development. e.g. Infants and Toddler-hood, Early Childhood, and Middle Childhood. It is very clearly presented.

It is very professionally presented. It is quite attractive in its presentation .

I saw no errors

The text appears to be aware of being diverse and inclusive both in its content and its graphics. It discusses culture and represents a variety of family structures representing contemporary society.

It is wonderfully researched. It will serve our students well. It is comprehensive and constructed very well. I have enjoyed getting familiar with this text and am looking forward to using it with my students in this upcoming term. The authors have presented a valuable, well written book that will be an addition to our field. Their scholarly efforts are very apparent. All of this text earns high grades in my evaluation. My only criticism is, as mentioned above, is that there is not a glossary or index provided. All citations are embedded in the text.

Reviewed by Ida Weldon, Adjunct Professor, Bunker Hill Community College on 6/30/20

The overall comprehensiveness was strong. However, I do think some sections should have been discussed with more depth read more

The overall comprehensiveness was strong. However, I do think some sections should have been discussed with more depth

Most of the information was accurate. However, I think more references should have been provided to support some claims made in the text.

The material appeared to be relevant. However, it did not provide guidance for teachers in addressing topics of social justice, equality that most children will ask as they try to make sense of their environment.

The information was presented (use of language) that added to its understand-ability. However, I think more discussions and examples would be helpful.

The text appeared to be consistent. The purpose and intent of the text was understandable throughout.

The text can easily be divided into smaller reading sections or restructured to meet the needs of the professor.

The organization of the text adds to its consistency. However, some sections can be included in others decreasing the length of the text.

Interface issues were not visible.

The text appears to be free of grammatical errors.

While cultural differences are mentioned, more time can be given to helping teachers understand and create a culturally and ethnically focused curriculum.

The textbook provides a comprehensive summary of curriculum planing for preschool age children. However, very few chapters address infant/toddlers.

Reviewed by Veronica Harris, Adjunct Faculty, Northern Essex Community College on 6/28/20

This text explores child development from genetics, prenatal development and birth through adolescence. The text does not contain a glossary. However, the Index is clear. The topics are sequential. The text addresses the domains of physical,... read more

This text explores child development from genetics, prenatal development and birth through adolescence. The text does not contain a glossary. However, the Index is clear. The topics are sequential. The text addresses the domains of physical, cognitive and social emotional development. It is thorough and easy to read. The theories of development are inclusive to give the reader a broader understanding on how the domains of development are intertwined. The content is comprehensive, well - researched and sequential. Each chapter begins with the learning outcomes for the upcoming material and closes with an outline of the topics covered. Furthermore, a look into the next chapter is discussed.

The content is accurate, well - researched and unbiased. An historical context is provided putting content into perspective for the student. It appears to be unbiased.

Updated and accurate research is evidenced in the text. The text is written and organized in such a way that updates can be easily implemented. The author provides theoretical approaches in the psychological domains with examples along with real - life scenarios providing meaningful references invoking understanding by the student.

The text is written with clarity and is easily understood. The topics are sequential, comprehensive and and inclusive to all students. This content is presented in a cohesive, engaging, scholarly manner. The terminology used is appropriate to students studying Developmental Psychology spanning from birth through adolescents.

The book's approach to the content is consistent and well organized. . Theoretical contexts are presented throughout the text.

The text contains subheadings chunking the reading sections which can be assigned at various points throughout the course. The content flows seamlessly from one idea to the next. Written chronologically and subdividing each age span into the domains of psychology provides clarity without overwhelming the reader.

The book begins with an overview of child development. Next, the text is divided logically into chapters which focus on each developmental age span. The domains of each age span are addressed separately in subsequent chapters. Each chapter outlines the chapter objectives and ends with an outline of the topics covered and share an idea of what is to follow.

Pages load clearly and consistently without distortion of text, charts and tables. Navigating through the pages is met with ease.

The text is written with no grammatical or spelling errors.

The text did not present with biases or insensitivity to cultural differences. Photos are inclusive of various cultures.

The thoroughness, clarity and comprehensiveness promote an approach to Developmental Psychology that stands alongside the best of texts in this area. I am confident that this text encompasses all the required elements in this area.

Reviewed by Kathryn Frazier, Assistant Professor, Worcester State University on 6/23/20

This is a highly comprehensive, chronological text that covers genetics and conception through adolescence. All major topics and developmental milestones in each age range are given adequate space and consideration. The authors take care to... read more

This is a highly comprehensive, chronological text that covers genetics and conception through adolescence. All major topics and developmental milestones in each age range are given adequate space and consideration. The authors take care to summarize debates and controversies, when relevant and include a large amount of applied / practical material. For example, beyond infant growth patterns and motor milestone, the infancy/toddler chapters spend several pages on the mechanics of car seat safety, best practices for introducing solid foods (and the rationale), and common concerns like diaper rash. In addition to being generally useful information for students who are parents, or who may go on to be parents, this text takes care to contextualize the psychological research in the lived experiences of children and their parents. This is an approach that I find highly valuable. While the text does not contain an index, the search & find capacity of OER to make an index a deal-breaker for me.

The text includes accurate information that is well-sourced. Relevant debates, controversies and historical context is also provided throughout which results in a rich, balanced text.

This text provides an excellent summary of classic and updated developmental work. While the majority of the text is skewed toward dated, classic work, some updated research is included. Instructors may wish to supplement this text with more recent work, particularly that which includes diverse samples and specifically addresses topics of class, race, gender and sexual orientation (see comment below regarding cultural aspects).

The text is written in highly accessible language, free of jargon. Of particular value are the many author-generated tables which clearly organize and display critical information. The authors have also included many excellent figures, which reinforce and visually organize the information presented.

This text is consistent in its use of terminology. Balanced discussion of multiple theoretical frameworks are included throughout, with adequate space provided to address controversies and debates.

The text is clearly organized and structured. Each chapter is self-contained. In places where the authors do refer to prior or future chapters (something that I find helps students contextualize their reading), a complete discussion of the topic is included. While this may result in repetition for students reading the text from cover to cover, the repetition of some content is not so egregious that it outweighs the benefit of a flexible, modular textbook.

Excellent, clear organization. This text closely follows the organization of published textbooks that I have used in the past for both lifespan and child development. As this text follows a chronological format, a discussion of theory and methods, and genetics and prenatal growth is followed by sections devoted to a specific age range: infancy and toddlerhood, early childhood (preschool), middle childhood and adolescence. Each age range is further split into three chapters that address each developmental domain: physical, cognitive and social emotional development.

All text appears clearly and all images, tables and figures are positioned correctly and free of distortion.

The text contains no spelling or grammatical errors.

While this text provides adequate discussion of gender and cross-cultural influences on development, it is not sufficient. This is not a problem unique to this text, and is indeed a critique I have of all developmental textbooks. In particular, in my view this text does not adequately address the role of race, class or sexual orientation on development.

All in all, this is a comprehensive and well-written textbook that very closely follows the format of standard chronologically-organized child development textbooks. This is a fantastic alternative for those standard texts, with the added benefit of language that is more accessible, and content that is skewed toward practical applications.

Reviewed by Tony Philcox, Professor, Valencia College on 6/4/20

The subject of this book is Child Growth and Development and as such covers all areas and ideas appropriate for this subject. This book has an appropriate index. The author starts out with a comprehensive overview of Child Development in the... read more

The subject of this book is Child Growth and Development and as such covers all areas and ideas appropriate for this subject. This book has an appropriate index. The author starts out with a comprehensive overview of Child Development in the Introduction. The principles of development were delineated and were thoroughly presented in a very understandable way. Nine theories were presented which gave the reader an understanding of the many authors who have contributed to Child Development. A good backdrop to start a conversation. This book discusses the early beginnings starting with Conception, Hereditary and Prenatal stages which provides a foundation for the future developmental stages such as infancy, toddler, early childhood, middle childhood and adolescence. The three domains of developmental psychology – physical, cognitive and social emotional are entertained with each stage of development. This book is thoroughly researched and is written in a way to not overwhelm. Language is concise and easily understood.

This book is a very comprehensive and detailed account of Child Growth and Development. The author leaves no stone unturned. It has the essential elements addressed in each of the developmental stages. Thoroughly researched and well thought out. The content covered was accurate, error-free and unbiased.

The content is very relevant to the subject of Child Growth and Development. It is comprehensive and thoroughly researched. The author has included a number of relevant subjects that highlight the three domains of developmental psychology, physical, cognitive and social emotional. Topics are included that help the student see the relevancy of the theories being discussed. Any necessary updates along the way will be very easy and straightforward to insert.

The text is easily understood. From the very beginning of this book, the author has given the reader a very clear message that does not overwhelm but pulls the reader in for more information. The very first chapter sets a tone for what is to come and entices the reader to learn more. Well organized and jargon appropriate for students in a Developmental Psychology class.

This book has all the ingredients necessary to address Child Growth and Development. Even at the very beginning of the book the backdrop is set for future discussions on the stages of development. Theorists are mentioned and embellished throughout the book. A very consistent and organized approach.

This book has all the features you would want. There are textbooks that try to cover too much in one chapter. In this book the sections are clearly identified and divided into smaller and digestible parts so the reader can easily comprehend the topic under discussion. This book easily flows from one subject to the next. Blocks of information are being built, one brick on top of another as you move through the domains of development and the stages of development.

This book starts out with a comprehensive overview in the introduction to child development. From that point forward it is organized into the various stages of development and flows well. As mentioned previously the information is organized into building blocks as you move from one stage to the next.

The text does not contain any significant interface issued. There are no navigation problems. There is nothing that was detected that would distract or confuse the reader.

There are no grammatical errors that were identified.

This book was not culturally insensitive or offensive in any way.

This book is clearly a very comprehensive approach to Child Growth and Development. It contains all the essential ingredients that you would expect in a discussion on this subject. At the very outset this book went into detail on the principles of development and included all relevant theories. I was never left with wondering why certain topics were left out. This is undoubtedly a well written, organized and systematic approach to the subject.

Reviewed by Eleni Makris, Associate Professor, Northeastern Illinois University on 5/6/20

This book is organized by developmental stages (infancy, toddler, early childhood, middle childhood and adolescence). The book begins with an overview of conception and prenatal human development. An entire chapter is devoted to birth and... read more

This book is organized by developmental stages (infancy, toddler, early childhood, middle childhood and adolescence). The book begins with an overview of conception and prenatal human development. An entire chapter is devoted to birth and expectations of newborns. In addition, there is a consistency to each developmental stage. For infancy, early childhood, middle childhood, and adolescence, the textbook covers physical development, cognitive development, and social emotional development for each stage. While some textbooks devote entire chapters to themes such as physical development, cognitive development, and social emotional development and write about how children change developmentally in each stage this book focuses on human stages of development. The book is written in clear language and is easy to understand.

There is so much information in this book that it is a very good overview of child development. The content is error-free and unbiased. In some spots it briefly introduces multicultural traditions, beliefs, and attitudes. It is accurate for the citations that have been provided. However, it could benefit from updating to research that has been done recently. I believe that if the instructor supplements this text with current peer-reviewed research and organizations that are implementing what the book explains, this book will serve as a strong source of information.

While the book covers a very broad range of topics, many times the citations have not been updated and are often times dated. The content and information that is provided is correct and accurate, but this text can certainly benefit from having the latest research added. It does, however, include a great many topics that serve to inform students well.

The text is very easy to understand. It is written in a way that first and second year college students will find easy to understand. It also introduces students to current child and adolescent behavior that is important to be understood on an academic level. It does this in a comprehensive and clear manner.

This book is very consistent. The chapters are arranged by developmental stage. Even within each chapter there is a consistency of theorists. For example, each chapter begins with Piaget, then moves to Vygotsky, etc. This allows for great consistency among chapters. If I as the instructor decide to have students write about Piaget and his development theories throughout the life span, students will easily know that they can find this information in the first few pages of each chapter.

Certainly instructors will find the modularity of this book easy. Within each chapter the topics are self-contained and extensive. As I read the textbook, I envisioned myself perhaps not assigning entire chapters but assigning specific topics/modules and pages that students can read. I believe the modules can be used as a strong foundational reading to introduce students to concepts and then have students read supplemental information from primary sources or journals to reinforce what they have read in the chapter.

The organization of the book is clear and flows nicely. From the table of context students understand how the book is organized. The textbook would be even stronger if there was a more detailed table of context which highlights what topics are covered within each of the chapter. There is so much information contained within each chapter that it would be very beneficial to both students and instructor to quickly see what content and topics are covered in each chapter.

The interface is fine and works well.

The text is free from grammatical errors.

While the textbook does introduce some multicultural differences and similarities, it does not delve deeply into multiracial and multiethnic issues within America. It also offers very little comment on differences that occur among urban, rural, and suburban experiences. In addition, while it does talk about maturation and sexuality, LGBTQ issues could be more prominent.

Overall I enjoyed this text and will strongly consider using it in my course. The focus is clearly on human development and has very little emphasis on education. However, I intend to supplement this text with additional readings and videos that will show concrete examples of the concepts which are introduced in the text. It is a strong and worthy alternative to high-priced textbooks.

Reviewed by Mohsin Ahmed Shaikh, Assistant Professor, Bloomsburg University of Pennsylvania on 9/5/19

The content extensively discusses various aspects of emotional, cognitive, physical and social development. Examples and case studies are really informative. Some of the areas that can be elaborated more are speech-language and hearing... read more

The content extensively discusses various aspects of emotional, cognitive, physical and social development. Examples and case studies are really informative. Some of the areas that can be elaborated more are speech-language and hearing development. Because these components contribute significantly in development of communication abilities and self-image.

Content covered is pretty accurate. I think the details impressive.

The content is relevant and is based on the established knowledge of the field.

Easy to read and follow.

The terminology used is consistent and appropriate.

I think of using various sections of this book in some of undergraduate and graduate classes.

The flow of the book is logical and easy to follow.

There are no interface issues. Images, charts and diagram are clear and easy to understand.

Well written

The text appropriate and do not use any culturally insensitive language.

I really like that this is a book with really good information which is available in open text book library.

Table of Contents

- Chapter 1: Introduction to Child Development

- Chapter 2: Conception, Heredity, & Prenatal Development

- Chapter 3: Birth and the Newborn

- Chapter 4: Physical Development in Infancy & Toddlerhood

- Chapter 5: Cognitive Development in Infancy and Toddlerhood

- Chapter 6: Social and Emotional Development in Infancy and Toddlerhood

- Chapter 7: Physical Development in Early Childhood

- Chapter 8: Cognitive Development in Early Childhood

- Chapter 9: Social Emotional Development in Early Childhood

- Chapter 10: Middle Childhood - Physical Development

- Chapter 11: Middle Childhood – Cognitive Development

- Chapter 12: Middle Childhood - Social Emotional Development

- Chapter 13: Adolescence – Physical Development

- Chapter 14: Adolescence – Cognitive Development

- Chapter 15: Adolescence – Social Emotional Development

Ancillary Material

About the book.

Welcome to Child Growth and Development. This text is a presentation of how and why children grow, develop, and learn. We will look at how we change physically over time from conception through adolescence. We examine cognitive change, or how our ability to think and remember changes over the first 20 years or so of life. And we will look at how our emotions, psychological state, and social relationships change throughout childhood and adolescence.

About the Contributors

Contribute to this page.

Advertisement

Psychosocial Development Research in Adolescence: a Scoping Review

- Original Article

- Published: 01 February 2022

- Volume 30 , pages 640–669, ( 2022 )

Cite this article

- Nuno Archer de Carvalho ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-6620-0804 1 , 2 &

- Feliciano Henriques Veiga ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-2977-6238 1 , 2

3746 Accesses

Explore all metrics

Erikson’s psychosocial development is a well-known and sound framework for adolescent development. However, despite its importance in scientific literature, the scarcity of literature reviews on Erikson’s theory on adolescence calls for an up-to-date systematization. Therefore, this study’s objectives are to understand the extent and nature of published research on Erikson’s psychosocial development in adolescence (10–19 years) in the last decade (2011–2020) and identify directions for meaningful research and intervention. A scoping review was conducted following Arksey and O’Malley’s framework, PRISMA-ScR guidelines, and a previous protocol, including a comprehensive search in eight databases. From 932 initial studies, 58 studies were selected. These studies highlighted the burgeoning research on Erikson’s approach, with a more significant representation of North American and European studies. The focus of most studies was on identity formation, presenting cross-cultural evidence of its importance in psychosocial development. Most of the studies used quantitative designs presenting a high number of different measures. Regarding topics and variables, studies emphasized the critical role of identity in adolescents’ development and well-being and the relevance of supporting settings in psychosocial development. However, shortcomings were found regarding the study of online and school as privileged developmental settings for adolescents. Suggestions included the need to consider the process of identity formation in the context of lifespan development and invest in supporting adolescents’ identity formation. Overall, conclusions point out Erikson’s relevance in understanding adolescents’ current challenges while offering valuable research and intervention directions to enhance adolescent growth potential.

Similar content being viewed by others

Why do children and adolescents (not) seek and access professional help for their mental health problems? A systematic review of quantitative and qualitative studies

The Role of School in Adolescents’ Identity Development. A Literature Review

Narrative Research

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Adolescence, the second decade of life, is also the second window of opportunity to influence developmental trajectories, promoting health, well-being, full potential development, and positive contribution to society (UNICEF, 2018 ). For this reason, adolescence is a pivotal phase of the life course that requires not only the basic conditions to survive but the best opportunities to thrive (e.g., Alfvén et al., 2019 ; Patton et al., 2016 ; UNICEF, 2018 ; WHO, 2019 ). These opportunities are intrinsically connected to education as a human right, which encompasses the mission of each person’s personality and full potential development (United Nations, 1989 , Art. 29), with particular attention to school as a privileged developmental setting (United Nations, 2001 ).

To better understand that mission, Erikson’s psychosocial development approach was convened as a key theory of human development that still challenges researchers, practitioners, and educators. Firstly, its understanding of development as a lifelong continuum of opportunities for growth, reconstruction, and positive change (Newman & Newman, 2015 ; Sprinthall & Collins, 2011 ) challenges research to go beyond sickness and to strive for a new and dynamic meaning for being alive and vital personality (Erikson, 1968/ 1994b , p. 91). This suggestion seems to anticipate positive psychology’s focus on the qualities, strengths, and virtues that enhance thriving (Newman & Newman, 2015 ; Seligman & Csikszentmihalyi, 2000 ). Secondly, psychosocial development has its cornerstone on the dynamic and complementary interplay between biological, psychological, and social dimensions (Erikson, 1968/ 1994b ; Erikson & Erikson, 1998 ). Therefore, its study implies overcoming disciplinary reifying restrictions or isolated dimensions (Newman & Newman, 2015 ). Thirdly, the theory presents a roadmap for development, with eight stages built around main developmental tasks and challenges from birth to old age. More than a rigid timetable as some authors present it (e.g., Lerner, 2002 ), Erikson’s framework should be read from a non-deterministic and interactionist perspective (Caldeira & Veiga, 2013 ; Sprinthall & Collins, 2011 ). This perspective assumes that the emphasis of psychosocial development’s stages should be set on the relation between the person and the social world, which accounts for development and the differences between persons and cultures (Koepke & Denissen, 2012 ; Newman & Newman, 2015 ). Similar attention toward bidirectional relation person context, and resulting developmental plasticity, is suggested in positive youth development approaches (Burkhard et al., 2020 ; Lerner et al., 2005 ; Silbereisen & Lerner, 2007 ).

For the above reasons, the psychosocial approach, grounded on Erikson’s care for human growth and fulfillment (Erikson, 1968/ 1994b ), is an influential, enduring, positive, and comprehensive framework, which continues to inspire abundant research and intervention (Dunkel & Harbke, 2017 ; Marcia, 2015 ; Zhang, 2015 ). Nevertheless, 70 years have passed since the publication of Childhood and Society (Erikson, 1950/ 1993 ), and children and adolescents’ process of growing has been undergoing fast-paced change (Dahl et al., 2018 ; Patton et al., 2016 ). This reality calls for a better understanding of how research on Erikson’s psychosocial development currently addresses these changes and their effects on adolescent development, thus contributing to enhance their optimum development and thriving. This call for understanding led the authors to conduct a prior and exploratory search of existing literature reviews published in the last decade, focusing on adolescents’ broad psychosocial development, using Google, Scopus, and Web of Science (Dec. 2020). The search rendered 362 literature reviews after removing duplicates. Four critical ideas of this exploratory search not only justified the need for a new and more comprehensive study, but also guided its options and design.

The first idea was the small number of psychosocial development reviews grounded on Erikson’s theory, focusing on adolescence and school setting, peer-reviewed, and published in the last decade. Only eight literature reviews fulfilled all the selection criteria (Chávez, 2016 ; Dunkel & Harbke, 2017 ; Knight et al., 2014 ; Koepke & Denissen, 2012 ; Meeus, 2011 , 2016 ; Ragelienė, 2016 ; Tsang et al., 2012 ). The most recent of these eight literature reviews was from 2017, and six were from Europe or North America. These findings heightened the question regarding the presence of Erikson’s theory in recent research on adolescent development. They also raised the question regarding research’s social and cultural comprehensiveness (Chávez, 2016 ), especially in a time of increased connection beyond geographical borders (Dunkel & Harbke, 2017 ).

The second idea of the exploratory search was the focus on identity, which was the main subject of five of the eight reviews. This emphasis on identity is not surprising. Erikson defended that personal identity, the “style of one’s individuality” (Erikson, 1968/ 1994b , p. 50), was the core striving of adolescent development (Rosenthal et al., 1981 ; Zacarés & Iborra, 2015 ). However, in the small set of five literature reviews on personal identity, different theoretical and empirical approaches were found, highlighting three main approaches. The first is identity resolution, centered on Erikson’s crisis between identity synthesis and identity confusion (Claes et al., 2014 ; Hatano et al., 2018 ). The second is identity exploration and commitment (Waterman, 2015 ), based on James Marcia’s identity status paradigm and complemented, in the last decades, with newer models aiming to deepen the processes and domains of identity development (Hatano et al., 2018 ; Waterman, 2015 ). Looking at these new and extended models, Waterman ( 2015 ) highlights two: the five dimension models of identity formation, including exploration in breadth, in-depth exploration, ruminative exploration, commitment making, and identification with commitment (Bogaerts et al., 2019 ), and the three dimension models of identity formation, including commitment, in-depth exploration, and reconsideration of commitment (Crocetti et al., 2011 ; Meeus, 2011 ). An appealing feature of this last model, also known as Meeus-Crocetti model, is the study of identity development across different identity domains (Crocetti, 2017 ; Crocetti et al., 2011 ), including the educational and interpersonal domains, particularly important in adolescence (Hatano et al., 2020 ). Finally, the third approach is known as identity styles, and it is anchored on Berzonsky’s identification of adolescents’ social-cognitive strategies to manage self-relevant information (Crocetti et al., 2014 ). Finally, in what concerns other identity types, one literature review calls attention to the growth of studies focusing on ethnic identity and its association with academic achievement (Meeus, 2011 ).

The third idea was the wide range of different methodological approaches (Erikson, 1968/ 1994b ; Ragelienė, 2016 ). Erikson’s research, mostly grounded on his clinical experience and logic, soon demanded empirical validation (Rosenthal et al., 1981 ; Santrock, 2011 ), which engaged many researchers using qualitative and quantitative approaches (Newman & Newman, 2015 ). Regarding quantitative studies, one review pointed to the need for more longitudinal approaches on psychosocial development (Chávez, 2016 ), while one meta-analysis showed that longitudinal studies have increased in the first decade of the twenty first century (Meeus, 2011 ). On the subject of measures of psychosocial development, studies conveyed evidence of researchers’ efforts to assess identity (Meeus, 2011 , 2016 ) and include different psychosocial stages (Dunkel & Harbke, 2017 ). Other authors reinforce the significance of this strive for instruments with good psychometric properties for adolescent samples that aim to assess psychosocial development and not only its isolated stages (Markstrom et al., 1997 ; Newman & Newman, 2015 ; Rosenthal et al., 1981 ).

The fourth idea was the broad and scattered set of topics and variables. Reviews encompass evidence of psychosocial development and identity’s critical role in adolescent’s health and well-being (Meeus, 2011 , 2016 ; Tsang et al., 2012 ); the relationship with personality features and psychological strengths (Chávez, 2016 ; Ragelienė, 2016 ; Tsang et al., 2012 ); and the role of parents (Chávez, 2016 ; Koepke & Denissen, 2012 ; Meeus, 2016 ; Tsang et al., 2012 ), peers (Meeus, 2016 ; Ragelienė, 2016 ), intergenerational voluntary interaction (Knight et al., 2014 ), and school safety (Tsang et al., 2012 ). One meta-analysis presented evidence to defend a general factor of psychosocial development (Dunkel & Harbke, 2017 ), and different suggestions were found regarding identity understanding and promotion (Tsang et al., 2012 ). Finally, some authors defended that the importance of Erikson’s theory for adolescents’ development is related to present-day challenges, namely, technological advances and Internet possibilities (Dunkel & Harbke, 2017 ; Tsang et al., 2012 ).

Current Study

The exploratory analysis of existing literature reviews on Erikson’s theory has confirmed a systematization shortcoming. It also confirmed the need for a present-day understanding of the extent and nature of the research on Erikson’s psychosocial development in adolescence. Aiming to fill in the gap, a rigorous and comprehensive scoping review was conducted. The scoping review is a recent methodology for literature review with an increasing presence in health and education research (O’Flaherty & Phillips, 2015 ; Pham et al., 2014 ). Oriented by a research problem, the scoping review thoroughly searches, selects, and synthesizes knowledge with the purpose of mapping “key concepts, types of evidence, and gaps in research related to a defined area or field” (Colquhoun et al., 2014 , pp. 1292–1294). It differs from a systematic review by presenting a research problem that aims for a wider breadth of coverage, but not for exhaustiveness, nor the quality assessment of the studies (Arksey & O’Malley, 2005 ; Levac et al., 2010 ; Tricco et al., 2018 ).

The present study aims to review and summarize the piecemeal research on Erikson’s psychosocial development, with the following research problem: what are the main features of the research on Erikson’s psychosocial development in adolescence produced over the last decade (2011–2020)? Five overarching study questions were derived from the research problem: (Q1) What is the extent of the research? (Q2) What conceptual definitions are used? (Q3) What designs and measures are used? (Q4) What are the main topics and variables studied? (Q5) What implications for research and intervention can be suggested?

This scoping review was conducted following Arksey and O’Malley’s ( 2005 ; Levac et al., 2010 ) five-stage framework and PRISMA-ScR standards checklist (Tricco et al., 2018 ). In addition, a scoping review protocol was developed and is available as supplementary material (Appendix 1 ) in the online version of the article. Other relevant references in the structuring of this review were a study about the use of scoping review methodology in research (Pham et al., 2014 ) and a scoping review about educational strategies in higher education (O’Flaherty & Phillips, 2015 ).

Identifying Relevant Studies

The information sources for this review included eight bibliographic databases: (1) Academic Search Complete, (2) Education Source, (3) Eric—Educational Resources Information Center, (4) PsycARTICLES, (5) PsycINFO, (6) Scielo, (7) Scopus, and (8) Web of Science (WoS). The search started in January 2021, and the last search was done on the 22nd of February 2021. The search strategy was based on a previous and exploratory search of existing literature reviews (December) and the discussion between researchers (January). Aiming to answer to the research problem balancing comprehensiveness and feasibility (Levac et al., 2010 ), the search focus was on the term “Erikson” and not on “psychosocial development.” To assess the adequacy of the search strategy, we selected a small set of authors and articles considered unavoidable to identify amid the results. An example of the final search string is presented in Table 1 .

Study Selection

The selection was an iterative process (Arksey & O’Malley, 2005 ; Levac et al., 2010 ) that engaged researchers in a permanent discussion and decision-making. Table 2 presents the eligibility criteria. About adolescence definition, the study followed WHO and UNICEF’s recommendation to consider the life period between 10 and 19 years (e.g., Patton et al., 2016 ; Sawyer et al., 2018 ; UNICEF, 2018 ; WHO, 2019 ).

The sources of evidence were selected using Microsoft Office Excel in three phases: (i) organization - the records were imported to a table, organized by authors, and duplicates were removed; (ii) screening - the titles, keywords, and abstracts were analyzed, allowing the exclusion of the records not complying with the eligibility criteria; and (iii) eligibility - a deeper analysis of each study was conducted to decide on its selection according to the eligibility criteria.

Charting the Data

Like the eligibility process, data charting was an iterative process of understanding the categories that will define the information to be sought, extracted, and charted (Arksey & O’Malley, 2005 ; Levac et al., 2010 ). This process was done for each study question, implying the permanent engagement and discussion between researchers. For the first three study questions, researchers previously defined the categories and refined them along the review process. For the fourth and fifth study questions, researchers built the categories upon the information extracted from each study, aiming to identify a set of common clusters to organize and present the results meaningfully. More than full coverage of all the topics of the studies, this process aimed to underpin their main features for each study question. The categories were defined using concepts from APA thesaurus (APA, 2021 ) or APA dictionary (APA, 2020 ), thus allowing more meaningful conceptual clusters. Data extraction was done using a characterization tool, filled in excel. The tool is presented as supplementary material (Appendix 2 ) in the online version of the article.

Collating, Summarizing, and Reporting Results

This phase of the work is visible in the presentation of results and their discussion. The Results section begins with a clear indication of the studies/ sources of evidence selection process, using the flow diagram suggested by PRISMA (Tricco et al., 2018 ) and a brief list of each study included. Because of the large number of studies involved, two options were taken. The first was to use O’Flaherty and Phillips’s ( 2015 ) suggestion to number each study and to use this number to mention or quote the study in the text. The second option was to use Pham’s et al. (2014) suggestion of presenting more detailed information of each study as supplementary information (Appendix 3 ), available in the online version of the article.

The presentation of the results also includes a summary table with a synthesis of the main results for each study question, followed by a narrative synthesis using the same order (Levac et al., 2010 ). The Discussion section follows, using the study question order and ending with the study’s main implications and limitations. A final section of Conclusion is presented.

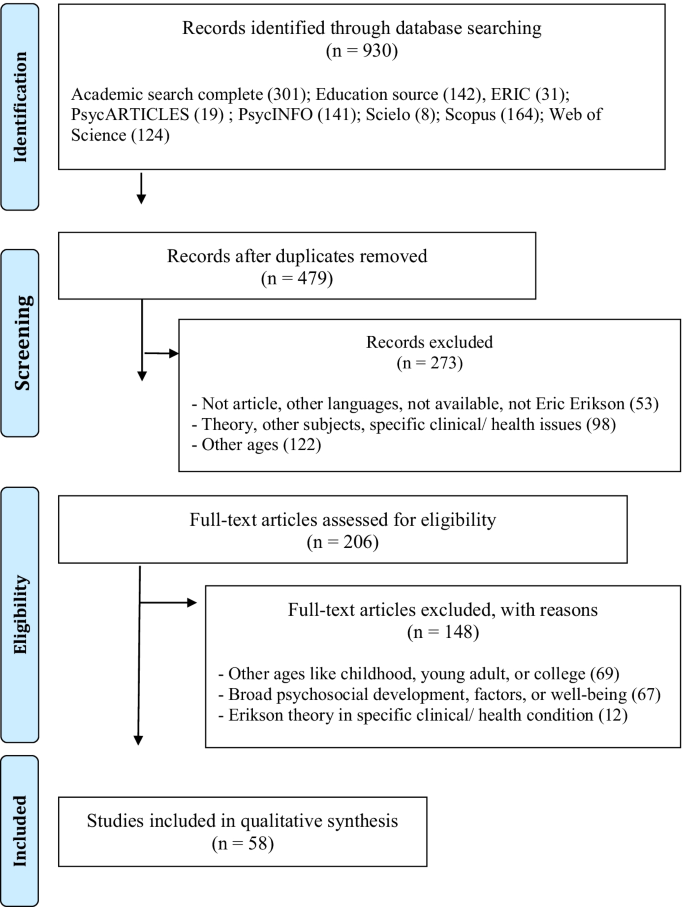

The initial search on the eight databases rendered 930 studies. After duplicates removal, screening, and eligibility assessment, 58 studies entered the final selection. This process is presented in Fig. 1 using the PRISMA flow diagram (Tricco et al., 2018 ). The studies included in the final selection are shown in Table 3 , organized by authors and with a numerical reference used throughout the text.

PRISMA flowchart of study selection process

Research Extent

Answering the first study question (Q1), the selection points to an increase in the number of studies from 2011–2015 (22 studies) to 2016–2020 (36 studies). Regarding the origin of the studies, 80% of the studies were from western provenance, with a slight difference between North America (25 studies) and Europe (21 studies). In the European studies, a substantive contribution of Belgium and Netherlands was found, related to research teams highly active in identity development study. The other regions account for a small percentage of the selection (3 or 4 studies). South America was represented with only one study from Brazil on the identity of adolescents living in institutional shelters (5). These results are visible in Table 4 , which summarizes the results for all the study questions.

Conceptual Approaches

The focus of 78% of the studies in this research was identity. Nevertheless, because identity summons different conceptual approaches, it is essential to understand which conceptual lenses were used. For this purpose, three main categories were suggested. The first category, named general identity issues , includes studies addressing more general questions regarding identity and accounts for 20% of the references. The second category, called identity formation , includes the studies addressing identity development throughout adolescence and accounts for 46% of the references. Finally, the third category is named specific identities and includes the studies focusing on specific elements valued in personal identity formation and accounts for 12% of the references. Table 5 presents the distribution of the studies in these three categories related to identity.

The general identity issues category includes important broad themes regarding identity. The first theme is identity’s central role in adolescent psychosocial development and well-being in western samples (e.g., 16, 29, 54, 55) and non-western samples, where interesting contextual specificities are presented (1, 13, 29, 36, 47). Another theme is the value of studying identity in the lifespan context, encompassing earlier stages of development, and considering identity development throughout life (9, 15). Other studies acknowledge the role of the context in adolescents’ development, including the relation with peers (39, 50), and the need to consider change and novelty, visible in the study of urban configurations like tagging cliques (7) or the study of online settings (30). Apart from this last reference, whose subject is drama education and the online environment, no other study was found that addressed online settings or social media. Still, in the context of this category, a single study was found focusing on Erikson’s moratoria (11).

In the category identity formation, three different conceptual approaches were found. The most represented approach was identity resolution (22 studies), which focuses on the tension between identity synthesis and identity confusion. Most of the studies in this approach point to the distinction between identity synthesis and identity confusion, whose differences are visible in adolescent development and well-being outcomes. Regarding other approaches, identity exploration and commitment is the primary approach of 12 studies, and identity styles appear in just one study (12). Finally, in the category addressing specific identities, ethnic identity is the guiding approach of seven studies from North America (8, 24, 25, 26, 44, 48, 54), while gender identity and occupational and vocational identity are approached in a single study each (52, 9).

Besides identity, there are four other categories of conceptual approaches. The first is psychosocial development (13% of the studies). In this category, five studies discussed the importance of understanding development as permanent growth. Some of them remind us of Erikson’s epigenetic continuum and the value of the association between stages and each stage-specific tasks and challenges across development (9, 15, 18, 37, 42). Despite this, only one literature review on occupational and vocational identity (9) approached adolescent’s identity integrating pre-adolescent stages. In the same category, another important conceptual focus was the biological dimension of development (33, 46, 53) and the social dimension, including family, school, and peers (14, 32). The last three categories of conceptual approaches included the study of other stages in adolescence, like intimacy or generativity (34, 35, 49, 58), the study of Erikson’s ego strengths (6, 24), and a single study focusing on the gifted students (51).

Designs and Measures

Erikson’s psychosocial development research presents a high number of studies with quantitative designs (72%), with a slight difference between longitudinal (40%) and cross-sectional studies (33%). Qualitative studies (10%) and literature reviews (10%) were also found in a smaller number, followed by studies using mixed methods (4%) and by two studies using quasi-experimental designs (4%).

Regarding measures, twenty different instruments were found. The Erikson Psychosocial Stage Inventory (EPSI) (Rosenthal et al., 1981 ) must be highlighted as the instrument used in more studies (43%). However, caution is required regarding this result because, with one exception (58), only the identity subscale of the instrument was used. A second important finding was the number of scales used exclusively in one study (28.57%). The measures used in two or more studies were different versions of the Utrecht-Management of Identity Commitments Scale (U-MICS) (2, 3, 29, 45); the Extended Objective Measure of Ego Identity Status (EOM-EIS) (5, 33, 36); the Identity Style Inventory (ISI) (12, 34); the Psychosocial Inventory of Ego Strengths (PIES) (24, 36); and the Loyola Generativity Scale (LGS) (34, 35, 49) present in three of the studies.

Main Topics and Variables

From the review of all the studies, a set of categories was created to present the main topics and variables. These topics were distributed in three complementary dimensions of psychosocial development: biological, psychological, and social (Erikson, 1968/ 1994b ; Erikson & Erikson, 1998 ). Table 6 presents the three dimensions, the main topics, the variables found, and the number of studies addressing them. Because the same study may examine more than one variable, some studies appear in the table more than once.

The biological dimension is the dimension with fewer studies. Nevertheless, these studies illustrate the importance of the physical component in identity development (33, 46, 53). The psychological dimension , which addresses the person’s mental functions, attributes, or states (APA, 2021 ), includes two topics. The first is adolescent characteristics , which groups the studies on adolescents’ features, traits, or qualities (APA, 2021 ). Besides attachment (35), results highlight the relation between identity and personality traits, including the “big five” (31), reactivity and regulation (21), sociotropy and autonomy (19), differentiation of self (50), and self-concept (55). Other results express the relations between identity and a set of psychological factors or strengths related to adolescents’ personality, health, or well-being (APA, 2020 ), such as fidelity (6), life goals (17), purpose in life (31), trust (20, 32), resilience and cognitive autonomy (36), optimism and self-esteem (44), and empathy (50). A single study was found focusing on the need to attend to the specific needs of gifted adolescent development (51).

The second topic in the psychological dimension was adolescent health , addressing the adolescent state of complete well-being (WHO, 1948 ) and all related behaviors, services, activities, and other factors that promote well-being (APA, 2021 ). This topic is undoubtedly the one that concentrates more studies, which speaks loudly of the importance of identity formation (identity synthesis, identity confusion, identity status, or identity maturity) as pivotal in adolescent health, development, and well-being. This topic includes a set of studies with the subject of well-being, including subjective well-being (29), psychological well-being (25), and the relation between identity resolution and identity exploration (4). It also includes a set of studies focused on risk factors that may affect identity formation, including the state of “lostness” (32), confusion (44), gender identity issues (52), or self-definition problems (55). Another set of studies brought forward identity as a protective factor regarding nonsuicidal self-injury (10, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 27, 38), substance use (26, 48), and eating disorders (56), and also, psychological and mental adjustment, namely, anxiety (2, 28) and depression symptoms (10, 28, 43). Another interesting result was the study of identity in the framework of positive youth development (PYD) (6, 16, 17).

Social dimension variables were organized according to different settings of the adolescent ecosystem, thus including community, family, peers, and school. In general, the set of studies in the social dimension draws attention to the importance of the context in adolescent development and how context-specific challenges, expectations, possibilities, and constraints may promote or hinder identity. Looking at the community topic, some studies tackle the question of cultural change, approaching issues affecting many immigrant adolescents or adolescents with immigrant families (24, 25, 26, 48), and adolescents in cultures whose values are in accelerated change (e.g., 1, 47). Still looking at the community topic, studies also point to specific opportunities like extracurricular activities (14) and support for occupational identity (9), or to their absence, of which a study (11) discussing how youth prospects may transform Erikson’s moratoria into a kind of waithood, is a good example. Other studies focus on the relation between development–identity and prosocial behavior, understood as contribution to the community (6, 49). Another study shows how religion is related to a more mature and adaptive identity style (12). Looking at the family topic, a first result is that almost all the studies focused on parents–adolescent relations, highlighting parenting practices (49) and the relation adolescent–mother (20, 23). Three studies focus on challenging family situations and their impact on adolescent development, like growing up in shelters (5), exposure to violence (40), and emotional abuse (27). Looking at peers topic, one study focuses on the relation between identity and group belonging (50), and several studies value the association between identity formation and positive relationships with peers (20, 23, 28, 34, 39, 50) including dating goals (58). Two studies focused on issues related to the formation of negative identities, including the urban cliques (7) and delinquency (45). One study brought up the romantic involvement subject and the impact of early romantic relationships on adolescents’ development (18). Looking at the school topic, the first finding is that none of the studies specifically addresses school. Some studies refer to the educational domain of identity development (2, 3, 29); others present results regarding the relation between development–identity and school adjustment (8, 9), including student connectedness (32), student engagement, and student achievement (54). Apart from one study analyzing immigrant adolescents’ lack of interest in social studies class (8), which included some concrete pedagogical features, and another study examining after-school activities (14), no other study specifically addresses school as a psychosocial developmental setting. In addition to this dim investment in studying the relationship between development and the school setting, there is a blatant absence in this selection of studies regarding technology, online settings, and social media in adolescence.

In the intervention topic , only four studies were found. One intervention focused on drama learning online (30). Another intervention, aiming to promote ethnic-racial identity, presented promising results regarding psychosocial functioning, including school adjustment (54). The most striking result on intervention oriented to enhance identity is the concept of cascade effects, that is, the evidence that the promotion of psychosocial resources like identity has positive effects in other personal and social adolescent resources, which affect others’ resources, and so on (16, 17, 54). In the methodology topic , our attention was drawn to the possibility and interest of combining identity statuses and identity narrative approaches in the study of identity (3, 42), as well as to the concern with identity measurement psychometry (13, 37, 57) and conceptual definition (41). Finally, in this topic, one literature review analyzed the data from Erikson’s psychosocial development measures, confirming not only the strong association between stages but a “general factor” of psychosocial development (15).

Research and Intervention Suggestions

About research , some common limitations were found regarding sample issues such as size or composition (19 studies), instruments or measures issues (10 studies), and the value of longitudinal research to study development (10 studies). Beyond these general limitations, Table 7 presents more specific suggestions regarding psychosocial development research. Some of these suggestions are more related to methodological issues, including the advantage of complementing self-report assessment with more objective information (4, 10, 20, 27, 38, 54, 56) or combining identity status with identity narrative (42). Other suggestions include the widening of the geographical and cultural scope of research (4, 56, 29) or the deepening of the relation between development and different developmental settings (2, 4), with particular regard to contexts marked by change, technology innovations, social media, and online communication (30). Finally, some suggestions valued the need for a more integrated understanding of identity in lifespan development, that is, considering identity along with other psychosocial stages of infancy and adult life (9, 34, 35, 49).

Because the subject of most of the studies was identity, the results regarding intervention also focus primarily on identity. Table 6 presents five different ideas conveyed by the different studies. The first idea highlights the importance of personal identity for adolescent development and well-being. In this sense, not only the role played by identity synthesis and confusion is amplified (e.g., 43), but also exploration processes (45) and different identity styles (12) are valued, with benefits for adolescents and also for society well-being (6, 46, 48). The second idea considers identity’s preventive power (10, 38, 20, 21, 22, 46, 56) and its value in promoting self-discovery and coping with contexts and life challenges (5, 17, 47). The third idea is the need for opportunities for active identity development through self-construction and self-discovery (43), including the importance of investing in contexts like school community (33), school and educators’ cultural responsiveness (8), extracurricular opportunities (14), and online contexts (30), among others. A fourth idea arises from studies with adolescents from minority groups that defend the importance of identifying with their own cultural or social group background (24, 25, 44, 54) and, concurrently, with the larger society (25). Finally, the fifth suggestion appears from the evidence that personal identity development fosters other personal and social resources in a cascade effect (16, 33, 34, 54).

Our research problem aimed to identify the main features of research on Erikson’s psychosocial development in adolescence over the last decade. This section discusses results for each study question (Q1 to Q5), ending with the main implications and limitations of the study.

Erikson’s Inspired Research Growth

Starting with the extent of the research (Q1), the studies show a growing trend throughout the decade. These results stress the actuality of Erikson’s way of looking at things (Erikson, 1950/ 1993 , p. 403), acknowledged in some studies included in the review (e.g., 31, 42, 6 15, 32) but also in the work of other authors (Marcia, 2015 ; Newman & Newman, 2015 ; Zhang, 2015 ). About the western affiliation of most of the studies, although in part due to the methodological search and selection options, it is consistent with the predominance of North America and Western Europe in psychological research (García-Martínez et al., 2012 ; O'Gorman et al., 2012 ) and in identity research (Schwartz et al., 2012 ). This reality is a challenge to give voice to researchers from other geographies, fostering a deeper understanding of human psychology (Arnett, 2008 ) and psychosocial development (Chávez, 2016 ; Hatano et al., 2020 ), moreover at the present time of heightened international contact (Dunkel & Harbke, 2017 ).

Identity in the Center of Research