Reference management. Clean and simple.

How to make a scientific presentation

Scientific presentation outlines

Questions to ask yourself before you write your talk, 1. how much time do you have, 2. who will you speak to, 3. what do you want the audience to learn from your talk, step 1: outline your presentation, step 2: plan your presentation slides, step 3: make the presentation slides, slide design, text elements, animations and transitions, step 4: practice your presentation, final thoughts, frequently asked questions about preparing scientific presentations, related articles.

A good scientific presentation achieves three things: you communicate the science clearly, your research leaves a lasting impression on your audience, and you enhance your reputation as a scientist.

But, what is the best way to prepare for a scientific presentation? How do you start writing a talk? What details do you include, and what do you leave out?

It’s tempting to launch into making lots of slides. But, starting with the slides can mean you neglect the narrative of your presentation, resulting in an overly detailed, boring talk.

The key to making an engaging scientific presentation is to prepare the narrative of your talk before beginning to construct your presentation slides. Planning your talk will ensure that you tell a clear, compelling scientific story that will engage the audience.

In this guide, you’ll find everything you need to know to make a good oral scientific presentation, including:

- The different types of oral scientific presentations and how they are delivered;

- How to outline a scientific presentation;

- How to make slides for a scientific presentation.

Our advice results from delving into the literature on writing scientific talks and from our own experiences as scientists in giving and listening to presentations. We provide tips and best practices for giving scientific talks in a separate post.

There are two main types of scientific talks:

- Your talk focuses on a single study . Typically, you tell the story of a single scientific paper. This format is common for short talks at contributed sessions in conferences.

- Your talk describes multiple studies. You tell the story of multiple scientific papers. It is crucial to have a theme that unites the studies, for example, an overarching question or problem statement, with each study representing specific but different variations of the same theme. Typically, PhD defenses, invited seminars, lectures, or talks for a prospective employer (i.e., “job talks”) fall into this category.

➡️ Learn how to prepare an excellent thesis defense

The length of time you are allotted for your talk will determine whether you will discuss a single study or multiple studies, and which details to include in your story.

The background and interests of your audience will determine the narrative direction of your talk, and what devices you will use to get their attention. Will you be speaking to people specializing in your field, or will the audience also contain people from disciplines other than your own? To reach non-specialists, you will need to discuss the broader implications of your study outside your field.

The needs of the audience will also determine what technical details you will include, and the language you will use. For example, an undergraduate audience will have different needs than an audience of seasoned academics. Students will require a more comprehensive overview of background information and explanations of jargon but will need less technical methodological details.

Your goal is to speak to the majority. But, make your talk accessible to the least knowledgeable person in the room.

This is called the thesis statement, or simply the “take-home message”. Having listened to your talk, what message do you want the audience to take away from your presentation? Describe the main idea in one or two sentences. You want this theme to be present throughout your presentation. Again, the thesis statement will depend on the audience and the type of talk you are giving.

Your thesis statement will drive the narrative for your talk. By deciding the take-home message you want to convince the audience of as a result of listening to your talk, you decide how the story of your talk will flow and how you will navigate its twists and turns. The thesis statement tells you the results you need to show, which subsequently tells you the methods or studies you need to describe, which decides the angle you take in your introduction.

➡️ Learn how to write a thesis statement

The goal of your talk is that the audience leaves afterward with a clear understanding of the key take-away message of your research. To achieve that goal, you need to tell a coherent, logical story that conveys your thesis statement throughout the presentation. You can tell your story through careful preparation of your talk.

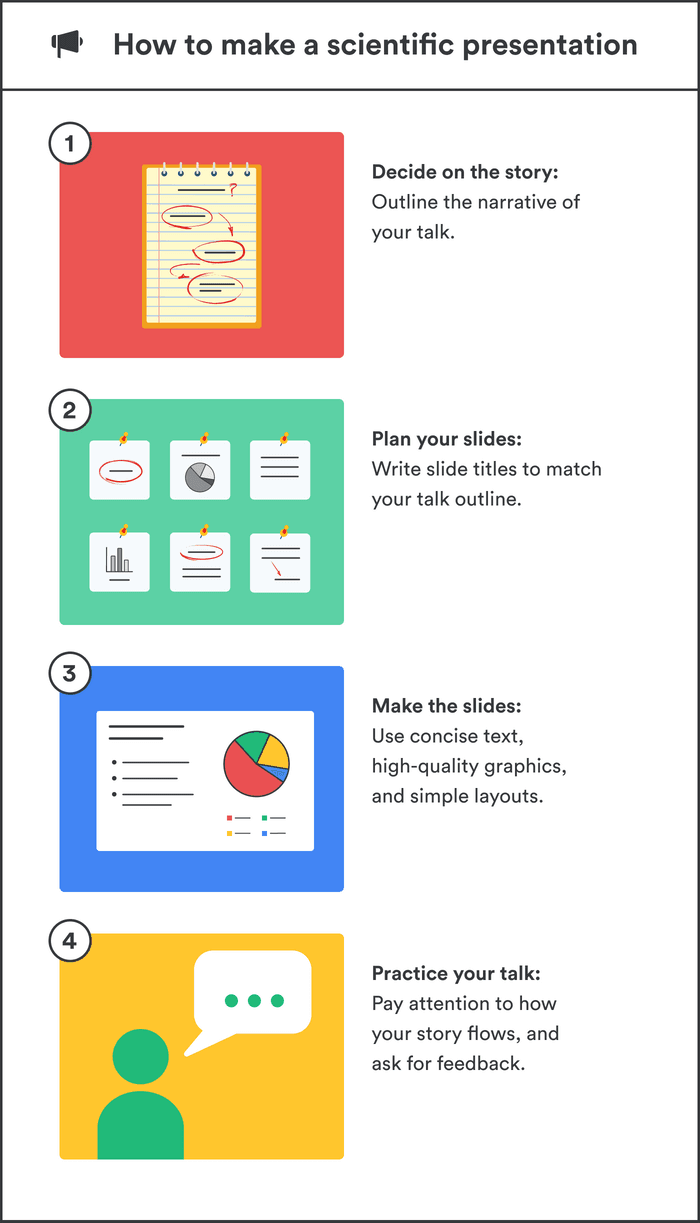

Preparation of a scientific presentation involves three separate stages: outlining the scientific narrative, preparing slides, and practicing your delivery. Making the slides of your talk without first planning what you are going to say is inefficient.

Here, we provide a 4 step guide to writing your scientific presentation:

- Outline your presentation

- Plan your presentation slides

- Make the presentation slides

- Practice your presentation

Writing an outline helps you consider the key pieces of your talk and how they fit together from the beginning, preventing you from forgetting any important details. It also means you avoid changing the order of your slides multiple times, saving you time.

Plan your talk as discrete sections. In the table below, we describe the sections for a single study talk vs. a talk discussing multiple studies:

Introduction | Introduction - main idea behind all studies |

Methods | Methods of study 1 |

Results | Results of study 1 |

Summary (take-home message ) of study 1 | |

Transition to study 2 (can be a visual of your main idea that return to) | |

Brief introduction for study 2 | |

Methods of study 2 | |

Results of study 2 | |

Summary of study 2 | |

Transition to study 3 | |

Repeat format until done | |

Summary | Summary of all studies (return to your main idea) |

Conclusion | Conclusion |

The following tips apply when writing the outline of a single study talk. You can easily adapt this framework if you are writing a talk discussing multiple studies.

Introduction: Writing the introduction can be the hardest part of writing a talk. And when giving it, it’s the point where you might be at your most nervous. But preparing a good, concise introduction will settle your nerves.

The introduction tells the audience the story of why you studied your topic. A good introduction succinctly achieves four things, in the following order.

- It gives a broad perspective on the problem or topic for people in the audience who may be outside your discipline (i.e., it explains the big-picture problem motivating your study).

- It describes why you did the study, and why the audience should care.

- It gives a brief indication of how your study addressed the problem and provides the necessary background information that the audience needs to understand your work.

- It indicates what the audience will learn from the talk, and prepares them for what will come next.

A good introduction not only gives the big picture and motivations behind your study but also concisely sets the stage for what the audience will learn from the talk (e.g., the questions your work answers, and/or the hypotheses that your work tests). The end of the introduction will lead to a natural transition to the methods.

Give a broad perspective on the problem. The easiest way to start with the big picture is to think of a hook for the first slide of your presentation. A hook is an opening that gets the audience’s attention and gets them interested in your story. In science, this might take the form of a why, or a how question, or it could be a statement about a major problem or open question in your field. Other examples of hooks include quotes, short anecdotes, or interesting statistics.

Why should the audience care? Next, decide on the angle you are going to take on your hook that links to the thesis of your talk. In other words, you need to set the context, i.e., explain why the audience should care. For example, you may introduce an observation from nature, a pattern in experimental data, or a theory that you want to test. The audience must understand your motivations for the study.

Supplementary details. Once you have established the hook and angle, you need to include supplementary details to support them. For example, you might state your hypothesis. Then go into previous work and the current state of knowledge. Include citations of these studies. If you need to introduce some technical methodological details, theory, or jargon, do it here.

Conclude your introduction. The motivation for the work and background information should set the stage for the conclusion of the introduction, where you describe the goals of your study, and any hypotheses or predictions. Let the audience know what they are going to learn.

Methods: The audience will use your description of the methods to assess the approach you took in your study and to decide whether your findings are credible. Tell the story of your methods in chronological order. Use visuals to describe your methods as much as possible. If you have equations, make sure to take the time to explain them. Decide what methods to include and how you will show them. You need enough detail so that your audience will understand what you did and therefore can evaluate your approach, but avoid including superfluous details that do not support your main idea. You want to avoid the common mistake of including too much data, as the audience can read the paper(s) later.

Results: This is the evidence you present for your thesis. The audience will use the results to evaluate the support for your main idea. Choose the most important and interesting results—those that support your thesis. You don’t need to present all the results from your study (indeed, you most likely won’t have time to present them all). Break down complex results into digestible pieces, e.g., comparisons over multiple slides (more tips in the next section).

Summary: Summarize your main findings. Displaying your main findings through visuals can be effective. Emphasize the new contributions to scientific knowledge that your work makes.

Conclusion: Complete the circle by relating your conclusions to the big picture topic in your introduction—and your hook, if possible. It’s important to describe any alternative explanations for your findings. You might also speculate on future directions arising from your research. The slides that comprise your conclusion do not need to state “conclusion”. Rather, the concluding slide title should be a declarative sentence linking back to the big picture problem and your main idea.

It’s important to end well by planning a strong closure to your talk, after which you will thank the audience. Your closing statement should relate to your thesis, perhaps by stating it differently or memorably. Avoid ending awkwardly by memorizing your closing sentence.

By now, you have an outline of the story of your talk, which you can use to plan your slides. Your slides should complement and enhance what you will say. Use the following steps to prepare your slides.

- Write the slide titles to match your talk outline. These should be clear and informative declarative sentences that succinctly give the main idea of the slide (e.g., don’t use “Methods” as a slide title). Have one major idea per slide. In a YouTube talk on designing effective slides , researcher Michael Alley shows examples of instructive slide titles.

- Decide how you will convey the main idea of the slide (e.g., what figures, photographs, equations, statistics, references, or other elements you will need). The body of the slide should support the slide’s main idea.

- Under each slide title, outline what you want to say, in bullet points.

In sum, for each slide, prepare a title that summarizes its major idea, a list of visual elements, and a summary of the points you will make. Ensure each slide connects to your thesis. If it doesn’t, then you don’t need the slide.

Slides for scientific presentations have three major components: text (including labels and legends), graphics, and equations. Here, we give tips on how to present each of these components.

- Have an informative title slide. Include the names of all coauthors and their affiliations. Include an attractive image relating to your study.

- Make the foreground content of your slides “pop” by using an appropriate background. Slides that have white backgrounds with black text work well for small rooms, whereas slides with black backgrounds and white text are suitable for large rooms.

- The layout of your slides should be simple. Pay attention to how and where you lay the visual and text elements on each slide. It’s tempting to cram information, but you need lots of empty space. Retain space at the sides and bottom of your slides.

- Use sans serif fonts with a font size of at least 20 for text, and up to 40 for slide titles. Citations can be in 14 font and should be included at the bottom of the slide.

- Use bold or italics to emphasize words, not underlines or caps. Keep these effects to a minimum.

- Use concise text . You don’t need full sentences. Convey the essence of your message in as few words as possible. Write down what you’d like to say, and then shorten it for the slide. Remove unnecessary filler words.

- Text blocks should be limited to two lines. This will prevent you from crowding too much information on the slide.

- Include names of technical terms in your talk slides, especially if they are not familiar to everyone in the audience.

- Proofread your slides. Typos and grammatical errors are distracting for your audience.

- Include citations for the hypotheses or observations of other scientists.

- Good figures and graphics are essential to sustain audience interest. Use graphics and photographs to show the experiment or study system in action and to explain abstract concepts.

- Don’t use figures straight from your paper as they may be too detailed for your talk, and details like axes may be too small. Make new versions if necessary. Make them large enough to be visible from the back of the room.

- Use graphs to show your results, not tables. Tables are difficult for your audience to digest! If you must present a table, keep it simple.

- Label the axes of graphs and indicate the units. Label important components of graphics and photographs and include captions. Include sources for graphics that are not your own.

- Explain all the elements of a graph. This includes the axes, what the colors and markers mean, and patterns in the data.

- Use colors in figures and text in a meaningful, not random, way. For example, contrasting colors can be effective for pointing out comparisons and/or differences. Don’t use neon colors or pastels.

- Use thick lines in figures, and use color to create contrasts in the figures you present. Don’t use red/green or red/blue combinations, as color-blind audience members can’t distinguish between them.

- Arrows or circles can be effective for drawing attention to key details in graphs and equations. Add some text annotations along with them.

- Write your summary and conclusion slides using graphics, rather than showing a slide with a list of bullet points. Showing some of your results again can be helpful to remind the audience of your message.

- If your talk has equations, take time to explain them. Include text boxes to explain variables and mathematical terms, and put them under each term in the equation.

- Combine equations with a graphic that shows the scientific principle, or include a diagram of the mathematical model.

- Use animations judiciously. They are helpful to reveal complex ideas gradually, for example, if you need to make a comparison or contrast or to build a complicated argument or figure. For lists, reveal one bullet point at a time. New ideas appearing sequentially will help your audience follow your logic.

- Slide transitions should be simple. Silly ones distract from your message.

- Decide how you will make the transition as you move from one section of your talk to the next. For example, if you spend time talking through details, provide a summary afterward, especially in a long talk. Another common tactic is to have a “home slide” that you return to multiple times during the talk that reinforces your main idea or message. In her YouTube talk on designing effective scientific presentations , Stanford biologist Susan McConnell suggests using the approach of home slides to build a cohesive narrative.

To deliver a polished presentation, it is essential to practice it. Here are some tips.

- For your first run-through, practice alone. Pay attention to your narrative. Does your story flow naturally? Do you know how you will start and end? Are there any awkward transitions? Do animations help you tell your story? Do your slides help to convey what you are saying or are they missing components?

- Next, practice in front of your advisor, and/or your peers (e.g., your lab group). Ask someone to time your talk. Take note of their feedback and the questions that they ask you (you might be asked similar questions during your real talk).

- Edit your talk, taking into account the feedback you’ve received. Eliminate superfluous slides that don’t contribute to your takeaway message.

- Practice as many times as needed to memorize the order of your slides and the key transition points of your talk. However, don’t try to learn your talk word for word. Instead, memorize opening and closing statements, and sentences at key junctures in the presentation. Your presentation should resemble a serious but spontaneous conversation with the audience.

- Practicing multiple times also helps you hone the delivery of your talk. While rehearsing, pay attention to your vocal intonations and speed. Make sure to take pauses while you speak, and make eye contact with your imaginary audience.

- Make sure your talk finishes within the allotted time, and remember to leave time for questions. Conferences are particularly strict on run time.

- Anticipate questions and challenges from the audience, and clarify ambiguities within your slides and/or speech in response.

- If you anticipate that you could be asked questions about details but you don’t have time to include them, or they detract from the main message of your talk, you can prepare slides that address these questions and place them after the final slide of your talk.

➡️ More tips for giving scientific presentations

An organized presentation with a clear narrative will help you communicate your ideas effectively, which is essential for engaging your audience and conveying the importance of your work. Taking time to plan and outline your scientific presentation before writing the slides will help you manage your nerves and feel more confident during the presentation, which will improve your overall performance.

A good scientific presentation has an engaging scientific narrative with a memorable take-home message. It has clear, informative slides that enhance what the speaker says. You need to practice your talk many times to ensure you deliver a polished presentation.

First, consider who will attend your presentation, and what you want the audience to learn about your research. Tailor your content to their level of knowledge and interests. Second, create an outline for your presentation, including the key points you want to make and the evidence you will use to support those points. Finally, practice your presentation several times to ensure that it flows smoothly and that you are comfortable with the material.

Prepare an opening that immediately gets the audience’s attention. A common device is a why or a how question, or a statement of a major open problem in your field, but you could also start with a quote, interesting statistic, or case study from your field.

Scientific presentations typically either focus on a single study (e.g., a 15-minute conference presentation) or tell the story of multiple studies (e.g., a PhD defense or 50-minute conference keynote talk). For a single study talk, the structure follows the scientific paper format: Introduction, Methods, Results, Summary, and Conclusion, whereas the format of a talk discussing multiple studies is more complex, but a theme unifies the studies.

Ensure you have one major idea per slide, and convey that idea clearly (through images, equations, statistics, citations, video, etc.). The slide should include a title that summarizes the major point of the slide, should not contain too much text or too many graphics, and color should be used meaningfully.

Tips for Scientific Writing & Presentation

The following resources will assist students with scientific writing and presentation skills including how to write an abstract and create a poster for a conference.

Abstract Guidelines

- Abstract Guidelines for the Medical Student Research Symposium

BU Authorship Guidelines

- What does it mean to be an author?

Manuscript Tips

- Me write pretty one day: how to write a scientific paper

- Improving your scientific writing: a short guide

- Online writing lab

- Bibliography software (Zotero has a lot of advantages (including that it is free).

Poster Tips

- Tips on Poster Design & Presentation

- Presentation Skills Toolkit for Medical Students (resources on developing and delivering formal lectures and presentations, poster and oral abstract presentations, patient presentations, and leading small group sessions)

- Conference presentations: Lead the poster parade

- Posters and Presentations (BU Alumni Medical Library—template here)

- Poster Template 2023 (template to create your poster; includes BMC and BU logos)

Printing Your Poster

- Fedex (700 Albany St., Boston) will print posters at a discount (tell them you are from BU). Most posters are printed on photo satin paper and can be emailed as a PDF to this Fedex location using the following email: [email protected] .

- PhD Posters

- Poster Presentations

- Posters should be created as a PowerPoint file at final size (check your meeting for dimensions; 4′ wide x 3′ tall is common).

Presentation Tips

- Slide Template for Short Talks (Note: The “presenter notes” in the file have tips and tricks.)

- Three Tips for Giving a Great Research Talk

- How to Speak (Patrick Winston’s famous MIT lecture)

- How to Give a Talk

If you have found other great resources please let us know .

- Program Design

- Peer Mentors

- Excelling in Graduate School

- Oral Communication

- Written communication

- About Climb

Creating a 10-15 Minute Scientific Presentation

In the course of your career as a scientist, you will be asked to give brief presentations -- to colleagues, lab groups, and in other venues. We have put together a series of short videos to help you organize and deliver a crisp 10-15 minute scientific presentation.

First is a two part set of videos that walks you through organizing a presentation.

Part 1 - Creating an Introduction for a 10-15 Minute Scientfic Presentation

Part 2 - Creating the Body of a 10-15 Minute Presentation: Design/Methods; Data Results, Conclusions

Two additional videos should prove useful:

Designing PowerPoint Slides for a Scientific Presentation walks you through the key principles in designing powerful, easy to read slides.

Delivering a Presentation provides tips and approaches to help you put your best foot forward when you stand up in front of a group.

Other resources include:

Quick Links

Northwestern bioscience programs.

- Biomedical Engineering (BME)

- Chemical and Biological Engineering (ChBE)

- Driskill Graduate Program in the Life Sciences (DGP)

- Interdepartmental Biological Sciences (IBiS)

- Northwestern University Interdepartmental Neuroscience (NUIN)

- Campus Emergency Information

- Contact Northwestern University

- Report an Accessibility Issue

- University Policies

- Northwestern Home

- Northwestern Calendar: PlanIt Purple

- Northwestern Search

Chicago: 420 East Superior Street, Rubloff 6-644, Chicago, IL 60611 312-503-8286

- Langson Library

- Science Library

- Grunigen Medical Library

- Law Library

- Connect From Off-Campus

- Accessibility

- Gateway Study Center

Email this link

Writing a scientific paper.

- Writing a lab report

- INTRODUCTION

- LITERATURE CITED

- Bibliography of guides to scientific writing and presenting

- Peer Review

What "Not" to Do

Figures and Captions in Lab Reports

More Books to Help

- Lab Report Writing Guides on the Web

- 15 ways to get your audience to leave you From Physics Today August , 1998 p. 86

A short article by Dr. Brett Couch and Dr. Deena Wassenberg, Biology Program, University of Minnesota

- Presentation Skills for Scientists : A Practical Guide, 2018 - ONLINE

- Student's Guide to Writing College Papers (5th ed.), 2019 - LL LB2369 .T82 2019

- Learning to Communicate in Science and Engineering : Case Studies from MIT , 2010 - ONLINE

- Explaining Research: How to Reach Key Audiences to Advance Your Work , 2010 - ONLINE

- Presentation Zen: Simple Ideas on Presentation Design and Delivery - LL HF5718.22 .R49 2008

- Slide:ology: The Art and Science of Creating Great Presentations, 2008- ONLINE

- Speaking About Science: Manual for Creating Clear Presentations , 2006. SL Q223 .M67 2006

- Writing for Engineering and Science Students : Staking Your Claim, 2019 - ONLINE

- << Previous: Peer Review

- Next: Lab Report Writing Guides on the Web >>

- Last Updated: Aug 4, 2023 9:33 AM

- URL: https://guides.lib.uci.edu/scientificwriting

Off-campus? Please use the Software VPN and choose the group UCIFull to access licensed content. For more information, please Click here

Software VPN is not available for guests, so they may not have access to some content when connecting from off-campus.

- My presentations

Auth with social network:

Download presentation

We think you have liked this presentation. If you wish to download it, please recommend it to your friends in any social system. Share buttons are a little bit lower. Thank you!

Presentation is loading. Please wait.

Introduction to Scientific Writing

Published by Buck Golden Modified over 5 years ago

Similar presentations

Presentation on theme: "Introduction to Scientific Writing"— Presentation transcript:

Results, Implications and Conclusions. Results Summarize the findings. – Explain the results that correspond to the hypotheses. – Present interesting.

Scientific Writing Jan Gustafsson IDE, Mälardalen University April 16, 2007.

ALEC 604: Writing for Professional Publication

Experimental Psychology PSY 433

Chapter One of Your Thesis

Business Memo purpose of writer needs of reader Memos solve problems

Dr Sue Watts January 7, 2014.

Succeeding in the World of Work Effective Writing.

Publication in scholarly journals Graham H Fleet Food Science Group School of Chemical Engineering, University of New South Wales Sydney Australia .

Chris Luszczek Biol2050 week 3 Lecture September 23, 2013.

Methodologies. The Method section is very important because it tells your Research Committee how you plan to tackle your research problem. Chapter 3 Methodologies.

Infectious Disease Seminar TRMD 7020

Scientific Communication

Writing a Thesis for a Literary Analysis Grade 11 English.

Written Presentations of Technical Subject Writing Guide vs. Term paper Writing style: specifics Editing Refereeing.

Report Writing. Introduction A report is a presentation of facts and findings, usually as a basis for recommendations; written for a specific readership,

Abstract An abstract is a concise summary of a larger project (a thesis, research report, performance, service project, etc.) that concisely describes.

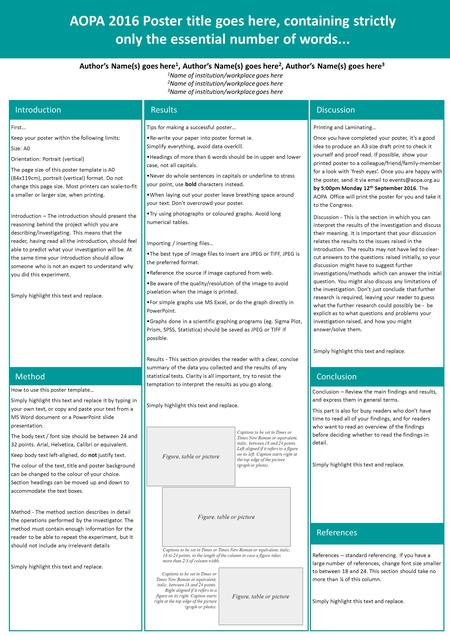

AOPA 2016 Poster title goes here, containing strictly only the essential number of words... Introduction First… Keep your poster within the following limits:

Unit 6: Report Writing. What is a Report? A report is written for a clear purpose and to a particular audience. Specific information and evidence is presented,

(almost) EVERYTHING ABOUT SUMMARIZING Adapted from A Sequence for Academic Writing by L. Behrens, L Rosen and B. Beedles.

About project

© 2024 SlidePlayer.com Inc. All rights reserved.

Steven Pifer

June 25, 2024

Keesha Middlemass

June 26, 2024

Jenny Schuetz, Eve Devens

June 24, 2024

Elizabeth Cox, Chloe East, Isabelle Pula

June 20, 2024

The Brookings Institution conducts independent research to improve policy and governance at the local, national, and global levels

We bring together leading experts in government, academia, and beyond to provide nonpartisan research and analysis on the most important issues in the world.

From deep-dive reports to brief explainers on trending topics, we analyze complicated problems and generate innovative solutions.

Brookings has been at the forefront of public policy for over 100 years, providing data and insights to inform critical decisions during some of the most important inflection points in recent history.

Subscribe to the Brookings Brief

Get a daily newsletter with our best research on top issues.

This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

Already a subscriber? Manage your subscriptions

Support Our Work

Invest in solutions. Drive impact.

Business Insider highlights research by Jon Valant showing that Arizona's universal education savings accounts are primarily benefiting wealthy families.

Valerie Wirtschafter spoke to the Washington Post about her latest study finding that Russian state media are ramping up on TikTok in both Spanish and English.

Tony Pipa writes in the New York Times about what's necessary for rural communities to benefit from federal investments made in the IIJA, IRA, & CHIPs.

What does the death of Iran’s President really mean? Suzanne Maloney writes in Politico about a transition already underway.

America’s foreign policy: A conversation with Secretary of State Antony Blinken

Online Only

10:30 am - 11:15 am EDT

The Brookings Institution, Washington D.C.

10:00 am - 11:15 am EDT

10:00 am - 11:00 am EDT

AEI, Washington DC

12:45 pm - 1:45 pm EDT

Jonathan Rothwell Andre M. Perry

June 21, 2024

Tom Wheeler

Janice C. Eberly Carol Graham Stephen Kissler Jón Steinsson

Diana Fu Emile Dirks

Afua Osei Landry Signé

Brookings Explains

Unpack critical policy issues through fact-based explainers.

Listen to informative discussions on important policy challenges.

COMMENTS

Scientific report writing. Nov 21, 2014 • Download as PPTX, PDF •. 21 likes • 15,460 views. AI-enhanced description. Shamim Mukhtar. This document provides an overview of scientific report writing. It defines a scientific report as a document that describes the process, progress, and results of technical or scientific research.

The document outlines best practices for writing research reports and scientific papers, preparing oral presentations, and selecting appropriate communication methods and outlets. Key aspects covered include writing in the IMRAD format, crafting a clear title, writing an informative abstract, and effectively communicating the introduction ...

Related Articles. This guide provides a 4-step process for making a good scientific presentation: outlining the scientific narrative, preparing slide outlines, constructing slides, and practicing the talk. We give advice on how to make effective slides, including tips for text, graphics, and equations, and how to use rehearsals of your talk to ...

Scientific Writing 26-27 August 2015 Mark A. Bell and Thomas L. Rost University of California, Davis, CA 95616 ... and key points in writing a scientific paper. Ending and beginning •End day 1. 5-10 minute reflection -what ... research is complete, 2. There is a need for further validation of

This handout provides a general guide to writing reports about scientific research you've performed. In addition to describing the conventional rules about the format and content of a lab report, we'll also attempt to convey why these rules exist, so you'll get a clearer, more dependable idea of how to approach this writing situation.

Scientific writing and presentation skills - Download as a PDF or view online for free ... This document provides an overview of the key sections and considerations for writing a scientific research paper. It discusses selecting an appropriate title, writing an abstract, introduction, methods, results, discussion, and conclusion. ...

PowerPoint Presentation. How to write a scientific paper. By Prof. Dr. Khadiga Gaafar. Zoology Dept., Faculty of Science, Cairo University. A scientific experiment is not complete until the results have been published and understood. A scientific paper is a written and published report describing original research results.

This format is often used for lab reports as well as for reporting any planned, systematic research in the social sciences, natural sciences, or engineering and computer sciences. Introduction - Make a case for your research. The introduction explains why this research is important or necessary or important. Begin by describing the problem or ...

8 Some major features of scientific writing. • Communicate information in concise and logical way • Make your paper stand out: convey how your results have changed the world. • Audience, forma, grammar, spelling and politics impose constraints on the scientific writing. • The secret is to match the mind of the reader.

The scientific writing process can be a daunting and often procrastinated "last step" in the scientific process, leading to cursory attempts to get scientific arguments and results down on paper. However, scientific writing is not an afterthought and should begin well before drafting the first outline.

Tips on Poster Design & Presentation. Presentation Skills Toolkit for Medical Students (resources on developing and delivering formal lectures and presentations, poster and oral abstract presentations, patient presentations, and leading small group sessions) Conference presentations: Lead the poster parade. Posters and Presentations (BU Alumni ...

Eliminating Redundancy: Scientific writing requires a writer to convey complex information directly and concisely. Add all the detail needed to convey the idea, but leave out extraneous information. Write concisely and omit redundancy by: Using precise action verbs. Avoiding hedging verbs such as appear and seem.

First is a two part set of videos that walks you through organizing a presentation. Part 1 - Creating an Introduction for a 10-15 Minute Scientfic Presentation. Part 2 - Creating the Body of a 10-15 Minute Presentation: Design/Methods; Data Results, Conclusions. Two additional videos should prove useful: Designing PowerPoint Slides for a ...

SCIENTIFIC RESEARCH WRITING SKILLS. Dr. R.K. Nivas provides an overview of how to write a well-structured research paper for publication. He discusses the key components of a research paper including the title, abstract, introduction, methods, results, discussion/conclusion, and references. He emphasizes formatting the paper according to the ...

When reporting the methods used in a sample -based study, the usual convention is to. discuss the following topics in the order shown: Chapter 13 Writing a Research Report 8. • Sample (number in ...

Student's Guide to Writing College Papers (5th ed.), 2019 - LL LB2369 .T82 2019. Learning to Communicate in Science and Engineering : Case Studies from MIT, 2010 - ONLINE. Explaining Research: How to Reach Key Audiences to Advance Your Work, 2010 - ONLINE. Presentation Zen: Simple Ideas on Presentation Design and Delivery - LL HF5718.22 .R49 2008.

Dec 19, 2019. 600 likes | 638 Views. Scientific Writing. Mehmet Tevfik DORAK, MD PhD Robert Stempel College of Public Health and Social Work Department of Epidemiology November 14, 2013. ( www ). Scientific Writing.

Presentation on theme: "Introduction to Scientific Writing"— Presentation transcript: 1 Introduction to Scientific Writing. COM 116 MH Rajab. 3 Introduction Writing a term paper, proposal or a scientific article is different from writing a short story or an essay as you used to do in the UPP. It takes time, training and effort.

Writing A Research Paper: A Guide. 2021 •. bishal joshi. INTRODUCTION A research paper is a part of academic writing where there is a gathering of information from different sources. It is multistep process. Selection of title is the most important part of research writing. The title which is interesting should be chosen for the research purpose.

41 likes • 25,432 views. Jessore University of Science and Technology. Follow. Scientific research articles provide a method for scientists to communicate with other scientists about the results of their research. The true value of any research is only realised when the results are subject to peer review and then published in journals. Education.

Writing Scientific Reports. Oct 14, 2014. 530 likes | 1.39k Views. Writing Scientific Reports. Mrs Seyma Akdag (KD) Student Learning Development. In this workshop we will. Review purpose and qualities of scientific writing Look at the component parts of the lab report - structure and format Explore the writing process. Download Presentation.

About the Programme LaTex: A Tool for Technical Writing, Presentation and Scientific Research with Hands-On Training 11-12th March 2024. Competence in technical writing holds great importance in the present era. ... technical reports, etc. This two days' training programme has been designed to provide a clear understanding of the basics of ...

Scientific paper writing ppt shalini phd. SHALINI BISHT This document provides an overview of the key sections and considerations for writing a scientific research paper. It discusses selecting an appropriate title, writing an abstract, introduction, methods, results, discussion, and conclusion. It also addresses statistical analysis, citing ...

The Brookings Institution is a nonprofit public policy organization based in Washington, DC. Our mission is to conduct in-depth research that leads to new ideas for solving problems facing society ...

ML/AI Applications to the Atmosphere Science Data and Simulations (Demonstration and Vision) Artificial Intelligence has been recognized as one of the most powerful tools for scientific research. It has a wide range of applications in atmospheric science and plays a significant role in advancing our understanding of the Earth-Atmosphere system, as well as improving our ability to monitor ...

In this ppt viewer will be able to know about how to write the report for the particular research. There are ethics to write means it should be easily understandable to the audience. Need to keep in mind that who is going to be audience. Portion covered: 1. Characteristics of a Research Report 2.