Essay on Breastfeeding

Students are often asked to write an essay on Breastfeeding in their schools and colleges. And if you’re also looking for the same, we have created 100-word, 250-word, and 500-word essays on the topic.

Let’s take a look…

100 Words Essay on Breastfeeding

What is breastfeeding.

Breastfeeding is a natural way of feeding a baby. It involves a mother giving her milk to her baby directly from her breasts. This milk is produced in the mother’s body and is rich in nutrients that are perfect for the baby’s growth and development.

Benefits of Breastfeeding

Breastfeeding has many benefits. It helps the baby grow strong and healthy. It also helps the mother and baby bond. The mother’s milk has antibodies that protect the baby from illnesses. It’s also free and always available, making it convenient.

Challenges in Breastfeeding

Some mothers may face challenges in breastfeeding. These can include pain, difficulty in the baby latching on, or not producing enough milk. It’s important to seek help from a doctor or a lactation consultant if these problems occur.

Support for Breastfeeding

Support for breastfeeding mothers is very important. Family members, friends, and healthcare providers can provide this support. They can help by offering encouragement, providing comfortable spaces for breastfeeding, and giving helpful advice.

Breastfeeding is a natural and beneficial way of feeding a baby. While it can present challenges, with the right support, these can be overcome. It’s a beautiful way to bond with the baby and provide the best nutrition.

250 Words Essay on Breastfeeding

Breastfeeding is the process of feeding a baby with milk directly from the mother’s breast. It is a natural act that has been practiced since the beginning of human existence. Breast milk is the best food source for newborns and infants.

The Importance of Breastfeeding

Breastfeeding is very important for both the baby and the mother. For the baby, breast milk provides all the necessary nutrients. It is easy to digest and helps protect the baby from illnesses. For the mother, breastfeeding can help her body recover faster after giving birth. It also creates a strong bond between the mother and the baby.

The Benefits of Breastfeeding

Breastfeeding offers many benefits. It helps the baby grow and develop properly. It also reduces the risk of the baby getting sick. For mothers, breastfeeding can help them lose weight after pregnancy. It can also lower their risk of certain health problems like breast cancer.

Breastfeeding Challenges

Even though breastfeeding is natural, it can be challenging for some mothers. Some common problems include pain, difficulty getting the baby to latch, and concerns about producing enough milk. But with support and practice, most of these challenges can be overcome.

There are many resources available to support breastfeeding mothers. These include lactation consultants, breastfeeding classes, and support groups. Remember, it’s okay to ask for help if you’re having trouble with breastfeeding.

In conclusion, breastfeeding is a beneficial and natural process that provides numerous health benefits for both the mother and the baby. Despite the challenges, with the right support, most mothers can successfully breastfeed their babies.

500 Words Essay on Breastfeeding

Understanding breastfeeding.

Breastfeeding is a natural process where a mother feeds her baby with milk produced from her breasts. It’s the first food a baby eats after they are born. This milk is rich in nutrients, which helps the baby grow strong and healthy. It’s the best food for newborns and infants.

Benefits of Breastfeeding for Babies

Breastfeeding offers many benefits to babies. First, breast milk has all the necessary nutrients that a baby needs for the first six months of life. It has proteins, fats, vitamins, and minerals in the right amounts. It also has antibodies, which are like soldiers in our bodies. They fight off harmful germs and keep the baby healthy.

Breast milk is also easy for the baby to digest. It helps the baby gain weight and grow at a healthy pace. Besides, it lowers the baby’s risk of getting allergies, asthma, and infections. It even makes the baby smarter as it boosts brain development.

Benefits of Breastfeeding for Mothers

Not only babies, but mothers also gain from breastfeeding. It helps the mother’s body recover from childbirth more quickly. It can also help the mother lose the weight she gained during pregnancy.

Breastfeeding can also lower the mother’s risk of getting certain diseases later in life. These include breast cancer, ovarian cancer, and type 2 diabetes. Besides health benefits, breastfeeding also helps to build a strong emotional bond between the mother and the baby.

Challenges of Breastfeeding

While breastfeeding is beneficial, it can sometimes be challenging. Some mothers may have difficulty producing enough milk. Others may find it painful or uncomfortable. Babies may also have trouble latching on to the breast correctly.

But don’t worry, help is available. Doctors, nurses, and lactation consultants can provide support and advice to make breastfeeding easier. They can teach mothers how to position the baby correctly and how to handle common breastfeeding problems.

In conclusion, breastfeeding is a wonderful gift that mothers can give to their babies. It provides the best nutrition for the baby and offers many health benefits for both the mother and the baby. Despite the challenges, with the right support and guidance, most mothers can successfully breastfeed their babies. Remember, every drop of breast milk counts, and every breastfeeding journey is unique and special.

That’s it! I hope the essay helped you.

If you’re looking for more, here are essays on other interesting topics:

- Essay on Education For Development

- Essay on Education As A Human Right

- Essay on Education And Success

Apart from these, you can look at all the essays by clicking here .

Happy studying!

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Open access

- Published: 26 November 2021

Women’s Perceptions and Experiences of Breastfeeding: a scoping review of the literature

- Bridget Beggs 1 ,

- Liza Koshy 1 &

- Elena Neiterman 1

BMC Public Health volume 21 , Article number: 2169 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

12k Accesses

23 Citations

4 Altmetric

Metrics details

Despite public health efforts to promote breastfeeding, global rates of breastfeeding continue to trail behind the goals identified by the World Health Organization. While the literature exploring breastfeeding beliefs and practices is growing, it offers various and sometimes conflicting explanations regarding women’s attitudes towards and experiences of breastfeeding. This research explores existing empirical literature regarding women’s perceptions about and experiences with breastfeeding. The overall goal of this research is to identify what barriers mothers face when attempting to breastfeed and what supports they need to guide their breastfeeding choices.

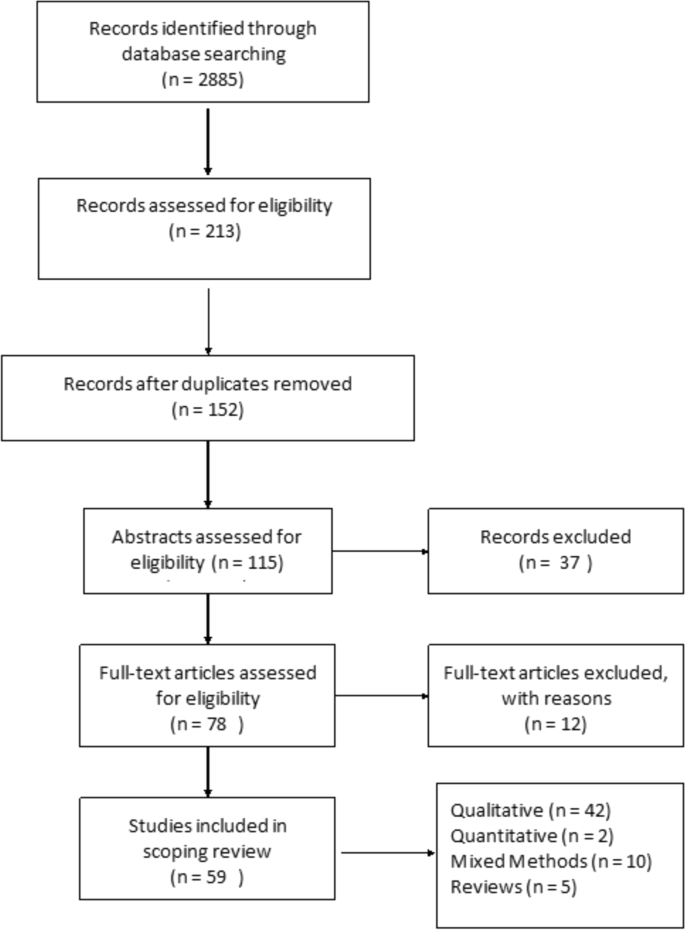

This paper uses a scoping review methodology developed by Arksey and O’Malley. PubMed, CINAHL, Sociological Abstracts, and PsychInfo databases were searched utilizing a predetermined string of keywords. After removing duplicates, papers published in 2010–2020 in English were screened for eligibility. A literature extraction tool and thematic analysis were used to code and analyze the data.

In total, 59 papers were included in the review. Thematic analysis showed that mothers tend to assume that breastfeeding will be easy and find it difficult to cope with breastfeeding challenges. A lack of partner support and social networks, as well as advice from health care professionals, play critical roles in women’s decision to breastfeed.

While breastfeeding mothers are generally aware of the benefits of breastfeeding, they experience barriers at individual, interpersonal, and organizational levels. It is important to acknowledge that breastfeeding is associated with challenges and provide adequate supports for mothers so that their experiences can be improved, and breastfeeding rates can reach those identified by the World Health Organization.

Peer Review reports

Public health efforts to educate parents about the importance of breastfeeding can be dated back to the early twentieth century [ 1 ]. The World Health Organization is aiming to have at least half of all the mothers worldwide exclusively breastfeeding their infants in the first 6 months of life by the year 2025 [ 2 ], but it is unlikely that this goal will be achieved. Only 38% of the global infant population is exclusively breastfed between 0 and 6 months of life [ 2 ], even though breastfeeding initiation rates have shown steady growth globally [ 3 ]. The literature suggests that while many mothers intend to breastfeed and even make an attempt at initiation, they do not always maintain exclusive breastfeeding for the first 6 months of life [ 4 , 5 ]. The literature identifies various barriers, including return to paid employment [ 6 , 7 ], lack of support from health care providers and significant others [ 8 , 9 ], and physical challenges [ 9 ] as potential factors that can explain premature cessation of breastfeeding.

From a public health perspective, the health benefits of breastfeeding are paramount for both mother and infant [ 10 , 11 ]. Globally, new mothers following breastfeeding recommendations could prevent 974,956 cases of childhood obesity, 27,069 cases of mortality from breast cancer, and 13,644 deaths from ovarian cancer per year [ 11 ]. Global economic loss due to cognitive deficiencies resulting from cessation of breastfeeding has been calculated to be approximately USD $285.39 billion dollars annually [ 11 ]. Evidently, increasing exclusive breastfeeding rates is an important task for improving population health outcomes. While public health campaigns targeting pregnant women and new mothers have been successful in promoting breastfeeding, they also have been perceived as too aggressive [ 12 ] and failing to consider various structural and personal barriers that may impact women’s ability to breastfeed [ 1 ]. In some cases, public health messaging itself has been identified as a barrier due to its rigid nature and its lack of flexibility in guidelines [ 13 ]. Hence, while the literature on women’s perceptions regarding breastfeeding and their experiences with breastfeeding has been growing [ 14 , 15 , 16 ], it offers various, and sometimes contradictory, explanations on how and why women initiate and maintain breastfeeding and what role public health messaging plays in women’s decision to breastfeed.

The complex array of the barriers shaping women’s experiences of breastfeeding can be broadly categorized utilizing the socioecological model, which suggests that individuals’ health is a result of the interplay between micro (individual), meso (institutional), and macro (social) factors [ 17 ]. Although previous studies have explored barriers and supports to breastfeeding, the majority of articles focus on specific geographic areas (e.g. United States or United Kingdom), workplaces, or communities. In addition, very few articles focus on the analysis of the interplay between various micro, meso, and macro-level factors in shaping women’s experiences of breastfeeding. Synthesizing the growing literature on the experiences of breastfeeding and the factors shaping these experiences, offers researchers and public health professionals an opportunity to examine how various personal and institutional factors shape mothers’ breastfeeding decision-making. This knowledge is needed to identify what can be done to improve breastfeeding rates and make breastfeeding a more positive and meaningful experience for new mothers.

The aim of this scoping review is to synthesize evidence gathered from empirical literature on women’s perceptions about and experiences of breastfeeding. Specifically, the following questions are examined:

What does empirical literature report on women’s perceptions on breastfeeding?

What barriers do women face when they attempt to initiate or maintain breastfeeding?

What supports do women need in order to initiate and/or maintain breastfeeding?

Focusing on women’s experiences, this paper aims to contribute to our understanding of women’s decision-making and behaviours pertaining to breastfeeding. The overarching aim of this review is to translate these findings into actionable strategies that can streamline public health messaging and improve breastfeeding education and supports offered by health care providers working with new mothers.

This research utilized Arksey & O’Malley’s [ 18 ] framework to guide the scoping review process. The scoping review methodology was chosen to explore a breadth of literature on women’s perceptions about and experiences of breastfeeding. A broad research question, “What does empirical literature tell us about women’s experiences of breastfeeding?” was set to guide the literature search process.

Search methods

The review was undertaken in five steps: (1) identifying the research question, (2) identifying relevant literature, (3) iterative selection of data, (4) charting data, and (5) collating, summarizing, and reporting results. The inclusion criteria were set to empirical articles published between 2010 and 2020 in peer-reviewed journals with a specific focus on women’s self-reported experiences of breastfeeding, as well as how others see women’s experiences of breastfeeding. The focus on women’s perceptions of breastfeeding was used to capture the papers that specifically addressed their experiences and the barriers that they may encounter while breastfeeding. Only articles written in English were included in the review. The keywords utilized in the search strategy were developed in collaboration with a librarian (Table 1 ). PubMed, CINAHL, Sociological Abstracts, and PsychInfo databases were searched for the empirical literature, yielding a total of 2885 results.

Search outcome

The articles deemed to fit the inclusion criteria ( n = 213) were imported into RefWorks, an online reference manager tool and further screened for eligibility (Fig. 1 ). After the removal of 61 duplicates and title/abstract screening, 152 articles were kept for full-text review. Two independent reviewers assessed the papers to evaluate if they met the inclusion criteria of having an explicit analytic focus on women’s experiences of breastfeeding.

Prisma Flow Diagram

Quality appraisal

Consistent with scoping review methodology [ 18 ], the quality of the papers included in the review was not assessed.

Data abstraction

A literature extraction tool was created in MS Excel 2016. The data extracted from each paper included: (a) authors names, (b) title of the paper, (c) year of publication, (d) study objectives, (e) method used, (f) participant demographics, (g) country where the study was conducted, and (h) key findings from the paper.

Thematic analysis was utilized to identify key topics covered by the literature. Two reviewers independently read five papers to inductively generate key themes. This process was repeated until the two reviewers reached a consensus on the coding scheme, which was subsequently applied to the remainder of the articles. Key themes were added to the literature extraction tool and each paper was assigned a key theme and sub-themes, if relevant. The themes derived from the analysis were reviewed once again by all three authors when all the papers were coded. In the results section below, the synthesized literature is summarized alongside the key themes identified during the analysis.

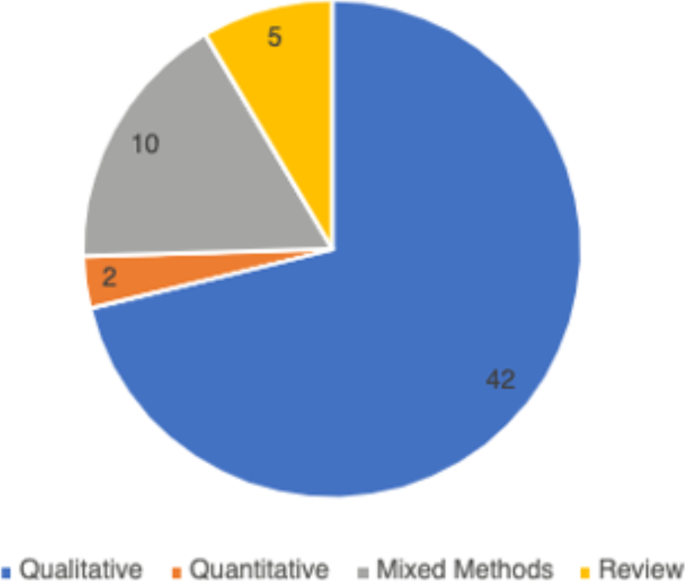

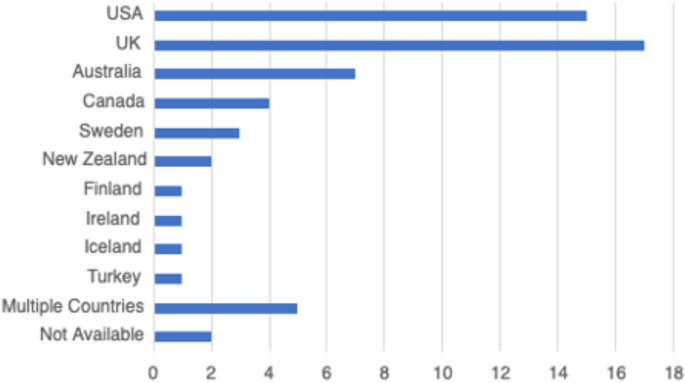

In total, 59 peer-reviewed articles were included in the review. Since the review focused on women’s experiences of breastfeeding, as would be expected based on the search criteria, the majority of articles ( n = 42) included in the sample were qualitative studies, with ten utilizing a mixed method approach (Fig. 2 ). Figure 3 summarizes the distribution of articles by year of publication and Fig. 4 summarizes the geographic location of the study.

Types of Articles

Years of Publication

Countries of Focus Examined in Literature Review

Perceptions about breastfeeding

Women’s perceptions about breastfeeding were covered in 83% ( n = 49) of the papers. Most articles ( n = 31) suggested that women perceived breastfeeding as a positive experience and believed that breastfeeding had many benefits [ 19 , 20 ]. The phrases “breast is best” and “breastmilk is best” were repeatedly used by the participants of studies included in the reviewed literature [ 21 ]. Breastfeeding was seen as improving the emotional bond between the mother and the child [ 20 , 22 , 23 ], strengthening the child’s immune system [ 24 , 25 ], and providing a booster to the mother’s sense of self [ 1 , 26 ]. Convenience of breastfeeding (e.g., its availability and low cost) [ 19 , 27 ] and the role of breastfeeding in weight loss during the postpartum period were mentioned in the literature as other factors that positively shape mothers’ perceptions about breastfeeding [ 28 , 29 ].

The literature suggested that women’s perceptions of breastfeeding and feeding choices were also shaped by the advice of healthcare providers [ 30 , 31 ]. Paradoxically, messages about the importance and relative simplicity of breastfeeding may also contribute to misalignment between women’s expectations and the actual experiences of breastfeeding [ 32 ]. For instance, studies published in Canada and Sweden reported that women expected breastfeeding to occur “naturally”, to be easy and enjoyable [ 23 ]. Consequently, some women felt unprepared for the challenges associated with initiation or maintenance of breastfeeding [ 31 , 33 ]. The literature pointed out that mothers may feel overwhelmed by the frequency of infant feedings [ 26 ] and the amount as well as intensity of physical difficulties associated with breastfeeding initiation [ 33 ]. Researchers suggested that since many women see breastfeeding as a sign of being a “good” mother, their inability to breastfeed may trigger feelings of personal failure [ 22 , 34 ].

Women’s personal experiences with and perceptions about breastfeeding were also influenced by the cultural pressure to breastfeed. Welsh mothers interviewed in the UK, for instance, revealed that they were faced with judgement and disapproval when people around them discovered they opted out of breastfeeding [ 35 ]. Women recalled the experiences of being questioned by others, including strangers, when they were bottle feeding their infants [ 9 , 35 , 36 ].

Barriers to breastfeeding

The vast majority ( n = 50) of the reviewed literature identified various barriers for successful breastfeeding. A sizeable proportion of literature (41%, n = 24) explored women’s experiences with the physical aspects of breastfeeding [ 23 , 33 ]. In particular, problems with latching and the pain associated with breastfeeding were commonly cited as barriers for women to initiate breastfeeding [ 23 , 28 , 37 ]. Inadequate milk supply, both actual and perceived, was mentioned as another barrier for initiation and maintenance of breastfeeding [ 33 , 37 ]. Breastfeeding mothers were sometimes unable to determine how much milk their infants consumed (as opposed to seeing how much milk the infant had when bottle feeding), which caused them to feel anxious and uncertain about scheduling infant feedings [ 28 , 37 ]. Women’s inability to overcome these barriers was linked by some researchers to low self-efficacy among mothers, as well as feeling overwhelmed or suffering from postpartum depression [ 38 , 39 ].

In addition to personal and physical challenges experienced by mothers who were planning to breastfeed, the literature also highlighted the importance of social environment as a potential barrier to breastfeeding. Mothers’ personal networks were identified as a key factor in shaping their breastfeeding behaviours in 43 (73%) articles included in this review. In a study published in the UK, lack of role models – mothers, other female relatives, and friends who breastfeed – was cited as one of the potential barriers for breastfeeding [ 36 ]. Some family members and friends also actively discouraged breastfeeding, while openly questioning the benefits of this practice over bottle feeding [ 1 , 17 , 40 ]. Breastfeeding during family gatherings or in the presence of others was also reported as a challenge for some women from ethnic minority groups in the United Kingdom and for Black women in the United States [ 41 , 42 ].

The literature reported occasional instances where breastfeeding-related decisions created conflict in women’s relationships with significant others [ 26 ]. Some women noted they were pressured by their loved one to cease breastfeeding [ 22 ], especially when women continued to breastfeed 6 months postpartum [ 43 ]. Overall, the literature suggested that partners play a central role in women’s breastfeeding practices [ 8 ], although there was no consistency in the reviewed papers regarding the partners’ expressed level of support for breastfeeding.

Knowledge, especially practical knowledge about breastfeeding, was mentioned as a barrier in 17% ( n = 10) of the papers included in this review. While health care providers were perceived as a primary source of information on breastfeeding, some studies reported that mothers felt the information provided was not useful and occasionally contained conflicting advice [ 1 , 17 ]. This finding was reported across various jurisdictions, including the United States, Sweden, the United Kingdom and Netherlands, where mothers reported they had no support at all from their health care providers which made it challenging to address breastfeeding problems [ 26 , 38 , 44 ].

Breastfeeding in public emerged as a key barrier from the reviewed literature and was cited in 56% ( n = 33) of the papers. Examining the experiences of breastfeeding mothers in the United States, Spencer, Wambach, & Domain [ 45 ] suggested that some participants reported feeling “erased” from conversations while breastfeeding in public, rendering their bodies symbolically invisible. Lack of designated public spaces for breastfeeding forced many women to alter their feeding in public and to retreat to a private or a more secluded space, such as one’s personal car [ 25 ]. The oversexualization of women’s breasts was repeatedly noted as a core reason for the United States women’s negative experiences and feelings of self-consciousness about breastfeeding in front of others [ 45 ]. Studies reported women’s accounts of feeling the disapproval or disgust of others when breastfeeding in public [ 46 , 47 ], and some reported that women opted out of breastfeeding in public because they did not want to make those around them feel uncomfortable [ 25 , 40 , 48 ].

Finally, return to paid employment was noted in the literature as a significant challenge for continuation of breastfeeding [ 48 ]. Lack of supportive workplace environments [ 39 ] or inability to express milk were cited by women as barriers for continuing breastfeeding in the United States and New Zealand [ 39 , 49 ].

Supports needed to maintain breastfeeding

Due to the central role family members played in women’s experiences of breastfeeding, support from partners as well as female relatives was cited in the literature as key factors shaping women’s breastfeeding decisions [ 1 , 9 , 48 ]. In the articles published in Canada, Australia, and the United Kingdom, supportive family members allowed women to share the responsibility of feeding and other childcare activities, which reduced the pressures associated with being a new mother [ 19 , 20 ]. Similarly, encouragement, breastfeeding advice, and validation from healthcare professionals were identified as positively impacting women’s experiences with breastfeeding [ 1 , 22 , 28 ].

Community resources, such as peer support groups, helplines, and in-home breastfeeding support provided mothers with the opportunity to access help when they need it, and hence were reported to be facilitators for breastfeeding [ 19 , 22 , 33 , 44 ]. An increase in the usage of social media platforms, such as Facebook, among breastfeeding mothers for peer support were reported in some studies [ 47 ]. Public health breastfeeding clinics, lactation specialists, antenatal and prenatal classes, as well as education groups for mothers were identified as central support structures for the initiation and maintenance of breastfeeding [ 23 , 24 , 28 , 33 , 39 , 50 ]. Based on the analysis of the reviewed literature, however, access to these services varied greatly geographically and by socio-economic status [ 33 , 51 ]. It is also important to note that local and cultural context played a significant role in shaping women’s perceptions of breastfeeding. For example, a study that explored women’s breastfeeding experiences in Iceland highlighted the importance of breastfeeding in Icelandic society [ 52 ]. Women are expected to breastfeed and the decision to forgo breastfeeding is met with disproval [ 52 ]. Cultural beliefs regarding breastfeeding were also deemed important in the study of Szafrankska and Gallagher (2016), who noted that Polish women living in Ireland had a much higher rate of initiating breastfeeding compared to Irish women [ 53 ]. They attributed these differences to familial and societal expectations regarding breastfeeding in Poland [ 53 ].

Overall, the reviewed literature suggested that women faced socio-cultural pressure to breastfeed their infants [ 36 , 40 , 54 ]. Women reported initiating breastfeeding due to recognition of the many benefits it brings to the health of the child, even when they were reluctant to do it for personal reasons [ 8 ]. This hints at the success of public health education campaigns on the benefits of breastfeeding, which situates breastfeeding as a new cultural norm [ 24 ].

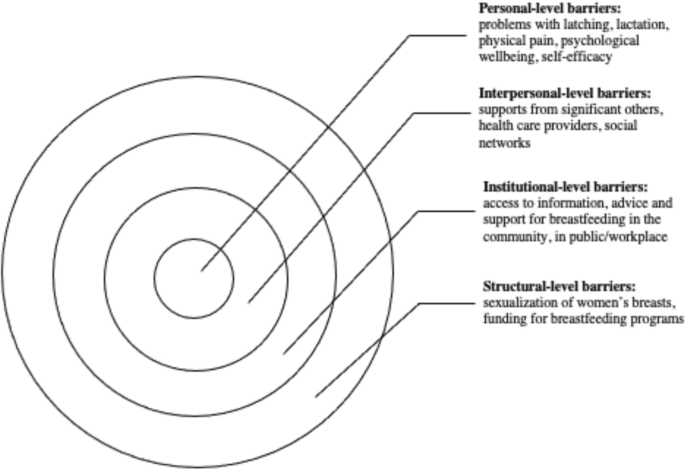

This scoping review examined the existing empirical literature on women’s perceptions about and experiences of breastfeeding to identify how public health messaging can be tailored to improve breastfeeding rates. The literature suggests that, overall, mothers are aware of the positive impacts of breastfeeding and have strong motivation to breastfeed [ 37 ]. However, women who chose to breastfeed also experience many barriers related to their social interactions with significant others and their unique socio-cultural contexts [ 25 ]. These different factors, summarized in Fig. 5 , should be considered in developing public health activities that promote breastfeeding. Breastfeeding experiences for women were very similar across the United Kingdom, United States, Canada, and Australia based on the studies included in this review. Likewise, barriers and supports to breastfeeding identified by women across the countries situated in the global north were quite similar. However, local policy context also impacted women’s experiences of breastfeeding. For example, maintaining breastfeeding while returning to paid employment has been identified as a challenge for mothers in the United States [ 39 , 45 ], a country with relatively short paid parental leave. Still, challenges with balancing breastfeeding while returning to paid employment were also noticed among women in New Zealand, despite a more generous maternity leave [ 49 ]. This suggests that while local and institutional policies might shape women’s experiences of breastfeeding, interpersonal and personal factors can also play a central role in how long they breastfeed their infants. Evidently, the importance of significant others, such as family members or friends, in providing support to breastfeeding mothers was cited as a key facilitator for breastfeeding across multiple geographic locations [ 29 , 34 , 48 ]. In addition, cultural beliefs and practices were also cited as an important component in either promoting breastfeeding or deterring women’s desire to initiate or maintain breastfeeding [ 15 , 29 , 37 ]. Societal support for breastfeeding and cultural practices can therefore partly explain the variation in breastfeeding rates across different countries [ 15 , 21 ]. Figure 5 summarizes the key barriers identified in the literature that inhibit women’s ability to breastfeed.

Barriers to Breastfeeding

At the individual level, women might experience challenges with breastfeeding stemming from various physiological and psychological problems, such as issues with latching, perceived or actual lack of breastmilk, and physical pain associated with breastfeeding. The onset of postpartum depression or other psychological problems may also impact women’s ability to breastfeed [ 54 ]. Given that many women assume that breastfeeding will happen “naturally” [ 15 , 40 ] these challenges can deter women from initiating or continuing breastfeeding. In light of these personal challenges, it is important to consider the potential challenges associated with breastfeeding that are conveyed to new mothers through the simplified message “breast is best” [ 21 ]. While breastfeeding may come easy to some women, most papers included in this review pointed to various challenges associated with initiating or maintaining breastfeeding [ 19 , 33 ]. By modifying public health messaging regarding breastfeeding to acknowledge that breastfeeding may pose a challenge and offering supports to new mothers, it might be possible to alleviate some of the guilt mothers experience when they are unable to breastfeed.

Barriers that can be experienced at the interpersonal level concern women’s communication with others regarding their breastfeeding choices and practices. The reviewed literature shows a strong impact of women’s social networks on their decision to breastfeed [ 24 , 33 ]. In particular, significant others – partners, mothers, siblings and close friends – seem to have a considerable influence over mothers’ decision to breastfeed [ 42 , 53 , 55 ]. Hence, public health messaging should target not only mothers, but also their significant others in developing breastfeeding campaigns. Social media may also be a potential medium for sharing supports and information regarding breastfeeding with new mothers and their significant others.

There is also a strong need for breastfeeding supports at the institutional and community levels. Access to lactation consultants, sound and practical advice from health care providers, and availability of physical spaces in the community and (for women who return to paid employment) in the workplace can provide more opportunities for mothers who want to breastfeed [ 18 , 33 , 44 ]. The findings from this review show, however, that access to these supports and resources vary greatly, and often the women who need them the most lack access to them [ 56 ].

While women make decisions about breastfeeding in light of their own personal circumstances, it is important to note that these circumstances are shaped by larger structural, social, and cultural factors. For instance, mothers may feel reluctant to breastfeed in public, which may stem from their familiarity with dominant cultural perspectives that label breasts as objects for sexualized pleasure [ 48 ]. The reviewed literature also showed that, despite the initial support, mothers who continue to breastfeed past the first year may be judged and scrutinized by others [ 47 ]. Tailoring public health care messaging to local communities with their own unique breastfeeding-related beliefs might help to create a larger social change in sociocultural norms regarding breastfeeding practices.

The literature included in this scoping review identified the importance of support from community services and health care providers in facilitating women’s breastfeeding behaviours [ 22 , 24 ]. Unfortunately, some mothers felt that the support and information they received was inadequate, impractical, or infused with conflicting messaging [ 28 , 44 ]. To make breastfeeding support more accessible to women across different social positions and geographic locations, it is important to acknowledge the need for the development of formal infrastructure that promotes breastfeeding. This includes training health care providers to help women struggling with breastfeeding and allocating sufficient funding for such initiatives.

Overall, this scoping review revealed the need for healthcare professionals to provide practical breastfeeding advice and realistic solutions to women encountering difficulties with breastfeeding. Public health messaging surrounding breastfeeding must re-invent breastfeeding as a “family practice” that requires collaboration between the breastfeeding mother, their partner, as well as extended family to ensure that women are supported as they breastfeed [ 8 ]. The literature also highlighted the issue of healthcare professionals easily giving up on women who encounter problems with breastfeeding and automatically recommending the initiation of formula use without further consideration towards solutions for breastfeeding difficulties [ 19 ]. While some challenges associated with breastfeeding are informed by local culture or health care policies, most of the barriers experienced by breastfeeding women are remarkably universal. Women often struggle with initiation of breastfeeding, lack of support from their significant others, and lack of appropriate places and spaces to breastfeed [ 25 , 26 , 33 , 39 ]. A change in public health messaging to a more flexible messaging that recognizes the challenges of breastfeeding is needed to help women overcome negative feelings associated with failure to breastfeed. Offering more personalized advice and support to breastfeeding mothers can improve women’s experiences and increase the rates of breastfeeding while also boosting mothers’ sense of self-efficacy.

Limitations

This scoping review has several limitations. First, the focus on “women’s experiences” rendered broad search criteria but may have resulted in the over or underrepresentation of specific findings in this review. Also, the exclusion of empirical work published in languages other than English rendered this review reliant on the papers published predominantly in English-speaking countries. Finally, consistent with Arksey and O’Malley’s [ 18 ] scoping review methodology, we did not appraise the quality of the reviewed literature. Notwithstanding these limitations, this review provides important insights into women’s experiences of breastfeeding and offers practical strategies for improving dominant public health messaging on the importance of breastfeeding.

Women who breastfeed encounter many difficulties when they initiate breastfeeding, and most women are unsuccessful in adhering to current public health breastfeeding guidelines. This scoping review highlighted the need for reconfiguring public health messaging to acknowledge the challenges many women experience with breastfeeding and include women’s social networks as a target audience for such messaging. This review also shows that breastfeeding supports and counselling are needed by all women, but there is also a need to tailor public health messaging to local social norms and culture. The role social institutions and cultural discourses have on women’s experiences of breastfeeding must also be acknowledged and leveraged by health care professionals promoting breastfeeding.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article [and its supplementary information files].

Wolf JH. Low breastfeeding rates and public health in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2003;93(12):2000–2010. [cited 2021 Apr 21] Available from: http://ajph.aphapublications.org/doi/ https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.93.12.2000

World Health Organization, UNICEF. Global nutrition targets 2015: Breastfeeding policy brief 2014.

United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund (UNICEF). Breastfeeding in the UK. 2019 [cited 2021 Apr 21]. Available from: https://www.unicef.org.uk/babyfriendly/about/breastfeeding-in-the-uk/

Semenic S, Loiselle C, Gottlieb L. Predictors of the duration of exclusive breastfeeding among first-time mothers. Res Nurs Health. 2008;31(5):428–441. [cited 2021 Apr 21] Available from: http://doi.wiley.com/ https://doi.org/10.1002/nur.20275

Hauck YL, Bradfield Z, Kuliukas L. Women’s experiences with breastfeeding in public: an integrative review. Women Birth. 2020;34:e217–27.

Hendaus MA, Alhammadi AH, Khan S, Osman S, Hamad A. Breastfeeding rates and barriers: a report from the state of Qatar. Int. J Women's Health. 2018;10:467–75 [cited 2021 Apr 20] Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC6110662/.

Google Scholar

Ogbo FA, Ezeh OK, Khanlari S, Naz S, Senanayake P, Ahmed KY, et al. Determinants of exclusive breastfeeding cessation in the early postnatal period among culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD) Australian mothers. Nutrients. 2019;11(7):1611 [cited 2021 Apr 21] Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/2072-6643/11/7/1611 .

Article Google Scholar

Ayton JE, Tesch L, Hansen E. Women’s experiences of ceasing to breastfeed: Australian qualitative study. BMJ Open. 2019;9(5):26234 [cited 2021 Apr 20] Available from: http://bmjopen.bmj.com/ .

Brown CRL, Dodds L, Legge A, Bryanton J, Semenic S. Factors influencing the reasons why mothers stop breastfeeding. Can J Public Heal. 2014;105(3):e179–e185. [cited 2021 Apr 20] Available from: https://link.springer.com/article/ https://doi.org/10.17269/cjph.105.4244

Sharma AJ, Dee DL, Harden SM. Adherence to breastfeeding guidelines and maternal weight 6 years after delivery. Pediatrics. 2014;134(Supplement 1):S42–S49. [cited 2021 Apr 21] Available from: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/doi/ https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2014-0646H

Walters DD, Phan LTH, Mathisen R. The cost of not breastfeeding: Global results from a new tool. Health Policy Plan. 2019;34(6):407–17 [cited 2021 Apr 21] Available from: https://academic.oup.com/heapol/article/34/6/407/5522499 .

Friedman M. For whom is breast best? Thoughts on breastfeeding, feminism and ambivalence. J Mother Initiat Res Community Involv. 2009;11(1):26–35 [cited 2021 Apr 20] Available from: https://jarm.journals.yorku.ca/index.php/jarm/article/viewFile/22506/20986 .

Blixt I, Johansson M, Hildingsson I, Papoutsi Z, Rubertsson C. Women’s advice to healthcare professionals regarding breastfeeding: “offer sensitive individualized breastfeeding support” - an interview study. Int Breastfeed J 2019;14(1):51. [cited 2021 Apr 20] Available from: https://internationalbreastfeedingjournal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13006-019-0247-4

Obeng C, Dickinson S, Golzarri-Arroyo L. Women’s perceptions about breastfeeding: a preliminary study. Children. 2020;7(6):61 [cited 2021 Apr 21] Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/2227-9067/7/6/61 .

Choudhry K, Wallace LM. ‘Breast is not always best’: South Asian women’s experiences of infant feeding in the UK within an acculturation framework. Matern Child Nutr. 2012;8(1):72–87. [cited 2021 Apr 20] Available from: http://doi.wiley.com/ https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1740-8709.2010.00253.x

Da Silva TD, Bick D, Chang YS. Breastfeeding experiences and perspectives among women with postnatal depression: a qualitative evidence synthesis. Women Birth. 2020;33(3):231–9.

Kilanowski JF. Breadth of the socio-ecological model. J Agromedicine. 2017;22(4):295–7 [cited 2021 Apr 20] Available from: https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=wagr20 .

Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol Theory Pract. 2005;8(1):19–32 [cited 2021 Apr 20] Available from: https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=tsrm20 .

Brown A, Lee M. An exploration of the attitudes and experiences of mothers in the United Kingdom who chose to breastfeed exclusively for 6 months postpartum. Breastfeed Med. 2011;6(4):197–204. [cited 2021 Apr 20] Available from: http://www.liebertpub.com/doi/ https://doi.org/10.1089/bfm.2010.0097

Morns MA, Steel AE, Burns E, McIntyre E. Women who experience feelings of aversion while breastfeeding: a meta-ethnographic review. Women Birth. 2021;34:128–35.

Jackson KT, Mantler T, O’Keefe-McCarthy S. Women’s experiences of breastfeeding-related pain. MCN Am J Matern Nurs. 2019;44(2):66–72 [cited 2021 Apr 20] Available from: https://journals.lww.com/00005721-201903000-00002 .

Burns E, Schmied V, Sheehan A, Fenwick J. A meta-ethnographic synthesis of women’s experience of breastfeeding. Matern Child Nutr. 2009;6(3):201–219. [cited 2021 Apr 20] Available from: http://doi.wiley.com/ https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1740-8709.2009.00209.x

Claesson IM, Larsson L, Steen L, Alehagen S. “You just need to leave the room when you breastfeed” Breastfeeding experiences among obese women in Sweden - A qualitative study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2018;18(1):1–10. [cited 2021 Apr 20] Available from: https://link.springer.com/articles/ https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-017-1656-2

Asiodu IV, Waters CM, Dailey DE, Lyndon • Audrey. Infant feeding decision-making and the influences of social support persons among first-time African American mothers. Matern Child Health J. 2017;21:863–72.

Forster DA, McLachlan HL. Women’s views and experiences of breast feeding: positive, negative or just good for the baby? Midwifery. 2010;26(1):116–25.

Demirci J, Caplan E, Murray N, Cohen S. “I just want to do everything right:” Primiparous Women’s accounts of early breastfeeding via an app-based diary. J Pediatr Heal Care. 2018;32(2):163–72.

Furman LM, Banks EC, North AB. Breastfeeding among high-risk Inner-City African-American mothers: a risky choice? Breastfeed Med. 2013;8(1):58–67. [cited 2021 Apr 20]Available from: http://www.liebertpub.com/doi/ https://doi.org/10.1089/bfm.2012.0012

Cottrell BH, Detman LA. Breastfeeding concerns and experiences of african american mothers. MCN Am J Matern Nurs. 2013;38(5):297–304 [cited 2021 Apr 20] Available from: https://journals.lww.com/00005721-201309000-00009 .

Wambach K, Domian EW, Page-Goertz S, Wurtz H, Hoffman K. Exclusive breastfeeding experiences among mexican american women. J Hum Lact. 2016;32(1):103–111. [cited 2021 Apr 21] Available from: http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/ https://doi.org/10.1177/0890334415599400

Regan P, Ball E. Breastfeeding mothers’ experiences: The ghost in the machine. Qual Health Res. 2013;23(5):679–688. [cited 2021 Apr 21] Available from: http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/ https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732313481641

Hinsliff-Smith K, Spencer R, Walsh D. Realities, difficulties, and outcomes for mothers choosing to breastfeed: Primigravid mothers experiences in the early postpartum period (6-8 weeks). Midwifery. 2014;30(1):e14–9.

Palmér L. Previous breastfeeding difficulties: an existential breastfeeding trauma with two intertwined pathways for future breastfeeding—fear and longing. Int J Qual Stud Health Well-being. 2019;14(1) [cited 2021 Apr 21] Available from: https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=zqhw20 .

Francis J, Mildon A, Stewart S, Underhill B, Tarasuk V, Di Ruggiero E, et al. Vulnerable mothers’ experiences breastfeeding with an enhanced community lactation support program. Matern Child Nutr 2020;16(3):16. [cited 2021 Apr 20] Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/ https://doi.org/10.1111/mcn.12957

Palmér L, Carlsson G, Mollberg M, Nyström M. Breastfeeding: An existential challenge - Women’s lived experiences of initiating breastfeeding within the context of early home discharge in Sweden. Int J Qual Stud Health Well-being 2010;5(3). [cited 2021 Apr 21] Available from: https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=zqhw20https://doi.org/ https://doi.org/10.3402/qhw.v5i3.5397

Grant A, Mannay D, Marzella R. ‘People try and police your behaviour’: the impact of surveillance on mothers and grandmothers’ perceptions and experiences of infant feeding. Fam Relationships Soc. 2018;7(3):431–47.

Thomson G, Ebisch-Burton K, Flacking R. Shame if you do - shame if you don’t: women’s experiences of infant feeding. Matern Child Nutr. 2015;11(1):33–46. [cited 2021 Apr 21] Available from: http://doi.wiley.com/ https://doi.org/10.1111/mcn.12148

Dietrich Leurer M, Misskey E. The psychosocial and emotional experience of breastfeeding: reflections of mothers. Glob Qual. Nurs Res. 2015;2:2333393615611654 [cited 2021 Apr 20] Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28462320 .

Fahlquist JN. Experience of non-breastfeeding mothers: Norms and ethically responsible risk communication. Nurs Ethics. 2016;23(2):231–241. [cited 2021 Apr 20] Available from: http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/ https://doi.org/10.1177/0969733014561913

Gross TT, Davis M, Anderson AK, Hall J, Hilyard K. Long-term breastfeeding in African American mothers: a positive deviance inquiry of WIC participants. J Hum Lact. 2017;33(1):128–139. [cited 2021 Apr 20] Available from: http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/ https://doi.org/10.1177/0890334416680180

Spencer RL, Greatrex-White S, Fraser DM. ‘I thought it would keep them all quiet’. Women’s experiences of breastfeeding as illusions of compliance: an interpretive phenomenological study. J Adv Nurs. 2015;71(5):1076–1086. [cited 2021 Apr 21] Available from: http://doi.wiley.com/ https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.12592

Twamley K, Puthussery S, Harding S, Baron M, Macfarlane A. UK-born ethnic minority women and their experiences of feeding their newborn infant. Midwifery. 2011;27(5):595–602.

PubMed Google Scholar

Lutenbacher M, Karp SM, Moore ER. Reflections of Black women who choose to breastfeed: influences, challenges, and supports. Matern Child Health J. 2016;20(2):231–9.

Dowling S, Brown A. An exploration of the experiences of mothers who breastfeed long-term: what are the issues and why does it matter? Breastfeed Med. 2013;8(1):45–52. [cited 2021 Apr 20] Available from: http://www.liebertpub.com/doi/ https://doi.org/10.1089/bfm.2012.0057

Fox R, McMullen S, Newburn M. UK women’s experiences of breastfeeding and additional breastfeeding support: a qualitative study of baby Café services. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2015;15(1):147. [cited 2021 Apr 20] Available from: http://bmcpregnancychildbirth.biomedcentral.com/articles/ https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-015-0581-5

Spencer B, Wambach K, Domain EW. African American women’s breastfeeding experiences: cultural, personal, and political voices. Qual Health Res. 2015;25(7):974–987. [cited 2021 Apr 21] Available from: http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/ https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732314554097

McBride-Henry K. The influence of the They: An interpretation of breastfeeding culture in New Zealand. Qual Health Res. 2010;20(6):768–777. [cited 2021 Apr 21] Available from: http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/ https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732310364220

Newman KL, Williamson IR. Why aren’t you stopping now?!’ Exploring accounts of white women breastfeeding beyond six months in the east of England. Appetite. 2018 Oct;1(129):228–35.

Dowling S, Pontin D. Using liminality to understand mothers’ experiences of long-term breastfeeding: ‘Betwixt and between’, and ‘matter out of place.’ Heal (United Kingdom). 2017;21(1):57–75. [cited 2021 Apr 20] Available from: http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/ https://doi.org/10.1177/1363459315595846

Payne D, Nicholls DA. Managing breastfeeding and work: a Foucauldian secondary analysis. J Adv Nurs. 2010;66(8):1810–1818. [cited 2021 Apr 21] Available from: http://doi.wiley.com/ https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2009.05156.x

Keely A, Lawton J, Swanson V, Denison FC. Barriers to breast-feeding in obese women: a qualitative exploration. Midwifery. 2015;31(5):532–9.

Afoakwah G, Smyth R, Lavender DT. Women’s experiences of breastfeeding: A narrative review of qualitative studies. Afr J Midwifery Womens Health. 2013 ;7(2):71–77. [cited 2021 Apr 21] Available from: https://www.magonlinelibrary.com/doi/abs/ https://doi.org/10.12968/ajmw.2013.7.2.71

Símonardóttir S. Getting the green light: experiences of Icelandic mothers struggling with breastfeeding. Sociol Res Online. 2016;21(4):1.

Szafranska M, Gallagher DL. Polish women’s experiences of breastfeeding in Ireland. Pract Midwife. 2016;19(1):30–2 [cited 2021 Apr 21] Available from: https://europepmc.org/article/med/26975131 .

Pratt BA, Longo J, Gordon SC, Jones NA. Perceptions of breastfeeding for women with perinatal depression: a descriptive phenomenological study. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2020;41(7):637–644. [cited 2021 Apr 21] Available from: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/ https://doi.org/10.1080/01612840.2019.1691690

Durmazoğlu G, Yenal K, Okumuş H. Maternal emotions and experiences of mothers who had breastfeeding problems: a qualitative study. Res Theory Nurs Pract. 2020;34(1):3–20. [cited 2021 Apr 20] Available from: http://connect.springerpub.com/lookup/doi/ https://doi.org/10.1891/1541-6577.34.1.3

Burns E, Triandafilidis Z. Taking the path of least resistance: a qualitative analysis of return to work or study while breastfeeding. Int Breastfeed J. 2019;14(1):1–13.

Download references

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the assistance of Jackie Stapleton, the University of Waterloo librarian, for her assistance with developing the search strategy used in this review.

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

School of Public Health Sciences, University of Waterloo, 200 University Ave West, Waterloo, ON, N2L 3G1, Canada

Bridget Beggs, Liza Koshy & Elena Neiterman

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

BB was responsible for the formal analysis and organization of the review. LK was responsible for data curation, visualization and writing the original draft. EN was responsible for initial conceptualization and writing the original draft. BB and LK were responsible for reviewing and editing the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ information

BB is completing her Bachelor of Science (BSc) degree at the School of Public Health Sciences at the University of Waterloo.

LK is completing her Bachelor of Public Health (BPH) degree at the School of Public Health Sciences at the University of Waterloo.

EN (PhD), is a continuing lecturer at the School of Public Health Sciences at the University of Waterloo. Her areas of expertise are in women’s reproductive health and sociology of health, illness, and healthcare.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Bridget Beggs .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate, consent for publication, competing interests.

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Beggs, B., Koshy, L. & Neiterman, E. Women’s Perceptions and Experiences of Breastfeeding: a scoping review of the literature. BMC Public Health 21 , 2169 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-12216-3

Download citation

Received : 23 June 2021

Accepted : 10 November 2021

Published : 26 November 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-12216-3

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Breastfeeding

- Experiences

- Public health

BMC Public Health

ISSN: 1471-2458

- General enquiries: [email protected]

The Radical Joy of Breastfeeding My 3-Year-Old

I’m not supposed to say that I breastfeed my 3-year-old because I like it. I’m supposed to say he needs it, he won’t quit. That I’m surrendering my body and time on the altar of attentive, attached motherhood. He enjoys it too, of course. He usually asks. I rarely offer. We do it a couple of times a day. More on weekends or when he’s hurt, sick, or just wants to. It also feels good. To me. It eases my anxiety. It is sentimental, sensory, and sensual. It fills me with love.

My son is large—in the 99th percentile for weight and height—so when he sits in my lap, his legs extend off the furniture, though he tries to curl them to become the smaller baby he once was. He squeals, then smushes my breast to his face with both hands, sometimes sucking and looking at me, sometimes drinking while driving a Matchbox car along my collarbone.

Years earlier, back in college, I sat beside a mother on an airplane who asked if I minded as she nursed her toddler. I said no, of course not. She schooled me on benefits for babies and the politics of nursing in public. I nodded, tried not to look. I remember feeling a blend of sympathy and discomfort as I tried on a mother identity in my mind—imagined whether I would ever breastfeed in that way, in public, a kid old enough to run, to feed himself, to speak multiclause sentences. It was my first exposure to a person nursing in front of me. I would barely experience that again until my own baby was at my breast.

More from TIME

Read More: I Thought I Had to Breastfeed My Babies. Then I Lost My Breasts

Breastfeeding is necessary and magical, yet American society stymies it from go. Babies need near constant access to their mothers’ bodies and uninterrupted time to figure out feeding, all but impossible in a country that sends a quarter of moms back to work two weeks after birth, denies postpartum support and paid leave, and assaults women’s autonomy. Any modicum of breastfeeding tolerance is for infants doing it, “breast is best” and all. It’s taboo to practice extended breastfeed (i.e., to breastfeed full-on kids). Calling it “extended” makes it an oddity—past what is expected, normal, or reasonable. Beyond its purpose to supply a product that can be extracted in private, fed to your kid by anyone. A pediatrician and an obstetrician separately told me that breastfeeding beyond six months is “just for the mom.” It’s almost certainly not. But so what if it is? It’s curious that when the act tips from benefiting babies to benefiting mothers, the censure flares.

The bulk of research devoted to understanding breastfeeding is on the nutritive benefits during the first six months to the first year of an infant’s life.While bodies like the WHO recommend breastfeeding babies for up to two years or beyond , we know practically nothing about breastfeeding beyond year one because we don’t study it. Still, we do know that breastfeeding’s rewards for mom–at least for the period that’s been the focus of research–are manifold and significant. It has been linked to a reduction in breast and ovarian cancer, and thanks to the oxytocin hit you get when you do it, you may experience a reduction in postpartum depression, stress, and anxiety. It can feel good in your head, in your body. It can create a closeness with your kid. Yet, by the time breastfeeding moves beyond necessity, beyond engorgement, spraying milk everywhere and soaking clothes, you’re urged to quit. Because doing it “for the mom” is wrong.

No one should feel shame about their feeding choices—everyone should make decisions that suit their body and family. I really appreciate that my kid comes to nurse for comfort, to regroup, as a pick-me-up or expression of love, rather than for a meal. Most women won’t experience this. The majority of people giving birth want to breastfeed, but only a quarter of moms exclusively breastfeed for their infant’s first six months as the CDC recommends .

We’re told infant feeding is individual choice. But the hurdles are institutional. “Women not meeting breastfeeding goals is presented as individual failure. That is such a lie. It’s such a fiction,” says Katie Hinde, a lactation researcher and professor of evolutionary biology at Arizona State University. We should receive far more support—from caregivers, health providers, work, family, the government, society. We all deserve the possibility of breastfeeding our kids for as long as we want, if we want to at all, but it’s a choice far too few people get to make.

Read More: Allyson Felix on How Motherhood Made Her an Activist

Even for those who manage to overcome the societal stigma and dearth of support to breastfeed babies in the early months, extended breastfeeding remains largely elusive, because stopping is what’s expected, or demanded. What feels like a natural conclusion to breastfeeding is actually a confluence of forces masquerading as care. As concern for mom, even—her body, space, money, and time. Breastfeeding your kid takes away your productivity and time with other people, so the pump and the bottle are presented as paths to freedom. Instead, they are the beginning of the end.

I think about this now, as I look forward to returning home at the end of the day to nurse my kid who is almost 4. It’s when my shoulders lower, I exhale deeply, snuggle him close, look in his eyes, and get a shot of oxytocin. To nurse is to be flooded with love. Sometimes I wonder why we must find verbal substitutes for what our bodies know and can communicate.

We are a universe away from the existential chaos of infant feeding—stressing that he isn’t getting enough ounces, trying to soothe cracked nipples, and being milked by my partner to unclog my ducts. Breastfeeding now feels gratifying, pleasurable, and anxiety reducing. The longer I do it and enjoy it, the more radical it feels. I’m saying I can do with my body what I want.

This article has been adapted from Birth Control: The Insidious Power of Men Over Motherhood, by Allison Yarrow. Copyright © 2023. Available from Seal Press, an imprint of Perseus Books, LLC, a subsidiary of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- How Selena Gomez Is Revolutionizing the Celebrity Beauty Business

- TIME100 Most Influential Companies 2024

- Javier Milei’s Radical Plan to Transform Argentina

- How Private Donors Shape Birth-Control Choices

- The Deadly Digital Frontiers at the Border

- What's the Best Measure of Fitness?

- The 31 Most Anticipated Movies of Summer 2024

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at [email protected]

Home — Essay Samples — Nursing & Health — Breastfeeding — Persuasive Speech On Breastfeeding

Persuasive Speech on Breastfeeding

- Categories: Breastfeeding

About this sample

Words: 581 |

Published: Mar 14, 2024

Words: 581 | Page: 1 | 3 min read

Cite this Essay

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Verified writer

- Expert in: Nursing & Health

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

2 pages / 866 words

3 pages / 1486 words

1 pages / 536 words

2 pages / 910 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on Breastfeeding

In conclusion, breastfeeding is a natural and beneficial method of feeding infants. It provides numerous health benefits for both mother and child, including improved immune function, cognitive development, and reduced risk of [...]

In the research article, a qualitative data analysis method has been used in order to verify the main research question. The four reasons can be provided in support of the claim that it was a qualitative research method. Seven [...]

Breastfeeding in connection with intelligence has long been a study of scientists in psychological professions in the years succeeding a 1929 study on the subject. Argumentation has gone back and forth, with some arguing that [...]

The United States is one of the highest birth rate for teens. If more teens were to take Birth control we would have less abortion rates and less teen pregnancies in the United States. There are many types and the [...]

The healthcare sector substantially has developed over the years thanks to the convenience brought by the current technologies advancements. Nevertheless, there are still many difficulties that the industry has to deal with, [...]

In 2013, Venka Child aged 16 from Bristol worked with Fixers to create a short video about challenges teen mothers go through. In some part of the video, a teen mother is shown opening a fridge which is almost empty. The teen [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

Benefits of Breastfeeding Versus Formula-Feeding Essay

- To find inspiration for your paper and overcome writer’s block

- As a source of information (ensure proper referencing)

- As a template for you assignment

Introduction

History of breastfeeding, advantages of breastfeeding over bottle-feeding, advantages of bottle-feeding over breastfeeding, importance of research.

Nowadays, one of the most challenging tasks many young mothers have to face is the necessity of choosing between breastfeeding and formula/bottle-feeding. It is easy to surf the web and find several correlational, cohort, or experimental studies where different authors defend their positions on the chosen topic. On the one hand, breastfeeding is deemed preferable due to its perfect balance of nutrients, protection against allergies and diseases, and easy digestion for babies.

On the other hand, formula-feeding is characterized by certain merits, such as the possibility for another person to feed a baby anytime, a mother’s freedom to be involved in different activities or even start working, and no dependence on the mother-child diet. Although some mothers might still choose to bottle-feed their infants with formula due to practical concerns, research shows that breastfeeding is preferable due to its impact on maternal and child health.

The history of breastfeeding is as long as the existence of life on the planet. In ancient cultures and in modern times women continued to breastfeed children to nourish them. However, some cultures did not focus on breastfeeding as an intimate link between the mother and the child. For example, while most ancient civilizations had mothers feed their children, more structurally segregated Western European countries created the role of a wet nurse – a woman whose job was to breastfeed children of royal and noblewomen.

Various cultures assigned different meanings to the process of breastfeeding and followed their sets of rules to determine how, when, and where to feed children. In ancient times, Egyptian and Greek civilizations did not treat breastfeeding as a job fit only for common folk and allowed women of all social statuses to feed their children. Nevertheless, wet nurses still had a place in the culture and were respected for their work. In Japan, breastfeeding was common but declined in popularity in the 20th century due to the interest of mothers in modern medicine and artificial feeding options. However, with a well-thought-out campaign, the government was able to elevate breastfeeding to be the primary choice of mothers in the country.

Western countries faced similar challenges earlier, during the middle ages, and then again at the beginning of the 19th century. Here, the history of breastfeeding was firmly connected to the cultural aspects of these civilizations. Countries with a rigid societal structure viewed breastfeeding as a job for lower classes and the process became plagued with many preconceptions. The combination of men’s opinions on breastfeeding and their lack of medical knowledge pressured women into declining breastfeeding. Later efforts in raising the popularity of breastfeeding emphasized health benefits for mothers and children and an establishment of an emotional connection between the parent and the child.

The breastfeeding vs. formula-feeding dilemma appears as soon as women find out that they are pregnant. They have to evaluate all the pros and cons of their pregnancy outcomes, understand if they want to take sick leave, and recognize the relationship between baby feeding and health. All circumstances have to be taken into consideration to make the best decision. Both methods, breastfeeding and bottle-feeding, have their advantages and disadvantages.

Sometimes, it is hard to make a choice, and extensive research is required. This dilemma may be considered through the prism of health, social factors, emotional stability, and personal convenience. In this paper, special attention to the works by Belfort et al. (2013), Boué et al. (2018), Fallon, Komninou, Bennett, Halford, and Harrold (2017), Horta and Victoria (2013) will be made to clarify if the benefits of breastfeeding prevail over the benefits of bottle-feeding in terms of health.

The first months after a baby is born may be defined as the period when it is necessary to choose to breastfeed over bottle-feeding and establish a strong mother-child contact. There are many short- and long-term health benefits for both participants of a process that may be enhanced through its exclusivity and duration (Fallon et al., 2017). The representatives of the World Health Organization admit that exclusive breastfeeding during the first six months can decrease morbidity from allergies and gastrointestinal diseases due to the presence of nutritional benefits in human milk (Horta & Victoria, 2013).

For example, the nutrient n-3 fatty acid docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) found in breast milk aims at improving the functions of the brain (Belfort et al., 2013). Therefore, when the advantages of breastfeeding have to be identified, this point plays an important role.

In addition to nutrients, breastfeeding is a method in terms of which infants can control their condition and take as much amount of milk as they may need. They do not take more or less, just the portion they need at that moment. Mothers should take responsibility for the quality of milk they offer to their children and follow simple hygiene rules and schedules.

Another important aspect that underlines the necessity of breastfeeding is the protection of children against diseases and other health threats. Probiotics and prebiotics, also known as important live microorganisms, protect the body and establish a gut microbiota that promotes positive health outcomes through the creation of barriers to pathogens, improvement of metabolic function, and energy salvation (Boué et al., 2018). Stomach viruses and other conditions that may cause discomfort are also significantly reduced with breastfeeding.

Allergies pose another serious threat to infants. It is hard for a mother to comprehend what product is safe for a child and what ingredients should be avoided. Breast milk is characterized by appropriate natural filters and the possibility to avoid ingesting real food until the body is properly developed. It helps babies digest food and uses the enzymes in a mother’s milk to speed up digestion and avoid complications.

Finally, breastfeeding is preferable because of the promotion of the bond between a mother and a child, and its price. This process of feeding is a unique chance for mothers to be relieved from anxiety and develop an emotional attachment to their children. Sometimes, it is not enough for mothers to talk to their children, observe their smile, and touch them. Breastfeeding is an exclusive type of contact that is not available to other people, including even the closest family members. This relationship is priceless. Indeed, when talking about the price, it is also necessary to admit that compared to bottle-feeding, which requires buying special ingredients, bottles, and hygienic goods, breastfeeding is a cheap process with no additional products except a mother and a child being present in it.

However, despite all the benefits of breastfeeding, it is wrong to believe that formula-feeding is solely negative or does not have important characteristics that breast-feeding cannot offer. Many significant aspects should be considered by mothers who still have some doubts about their choice. For example, some mothers may be challenged by poor health or inappropriate health status for breastfeeding.

Mothers may suffer from the inability to breastfeed as they are unable to produce milk or the milk is of poor quality. In these cases, mothers still want to find new ways to be close to their children and support them and formula-feeding is one option that they can rely on on under any condition. No connection between the health problems of a mother and a child is observed. Bottle-feeding creates several good opportunities for mothers to stabilize their personal and professional lives. Fallon et al. (2017) admit that the choice of the formula is usually explained by breastfeeding management, not biological issues. Therefore, the advantages of bottle-feeding over breastfeeding in terms of health care are based on the emotional aspects and mental health of mothers.

An understanding of the differences between breastfeeding and formula-feeding should be based on thorough research. For example, a study developed by Horta and Victoria (2013) asserts that formula-fed children may have serious hormonal and insulin responses to feeding and an increased number of adipocytes compared to breast-fed children. Bottles have to be cleaned and properly stored to avoid the growth of bacteria that may harm a child (Boué et al., 2018). Finally, the study by Fallon et al. (2017) shows that mothers may feel guilt and stigma in case they choose formula as the main method of feeding. All these studies prove that research is a crucial step to comprehend the benefits of breastfeeding nowadays.

In general, it is hard to neglect the existing dilemma of breastfeeding vs. bottle-feeding. Mothers have to weigh all the pros and cons of both processes and understand what method is more appropriate to them. Regarding the chosen cohort and experimental studies and past research, it is concluded that despite several positive socio-cultural and emotional outcomes of formula-feeding, breastfeeding remains the preferred method due to its effects on health, the establishment of mother-child relations, and the promotion of the cognitive development of children.

Belfort, M. B., Rifas-Shiman, S. L., Kleinman, K. P., Guthrie, L. B., Bellinger, D. C., Taveras, E. M.,… Oken, E. (2013). Infant feeding and childhood cognition at ages 3 and 7 years: Effects of breastfeeding duration and exclusivity. JAMA Pediatrics, 167 (9), 836-844.

Boué, G., Cummins, E., Guillou, S., Antignac, J. P., Le Bizec, B., & Membré, J. M. (2018). Public health risks and benefits associated with breast milk and infant formula consumption. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition, 58 (1), 126-145.

Fallon, V., Komninou, S., Bennett, K. M., Halford, J. C., & Harrold, J. A. (2017). The emotional and practical experiences of formula‐feeding mothers. Maternal & Child Nutrition, 13 (4), 1-14.

Horta, B. L., & Victoria, C. G. (2013). Long-term effects of breastfeeding: A systematic review . Geneva, Switzerland: WHO Press.

- Breastfeeding and Bottle Feeding: Pros and Cons

- Breastfeeding Health Teaching Project

- Transportation and Public Health Issues

- Breastfeeding and Children Immunity

- Angelman Syndrome, Communication and Behavior

- At-Risk Children's Healthcare Programs

- Premature Infants and Their Challenges

- Pediatric Health Care and Insurance in the USA

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2020, October 23). Benefits of Breastfeeding Versus Formula-Feeding. https://ivypanda.com/essays/benefits-of-breastfeeding-versus-formula-feeding/

"Benefits of Breastfeeding Versus Formula-Feeding." IvyPanda , 23 Oct. 2020, ivypanda.com/essays/benefits-of-breastfeeding-versus-formula-feeding/.

IvyPanda . (2020) 'Benefits of Breastfeeding Versus Formula-Feeding'. 23 October.

IvyPanda . 2020. "Benefits of Breastfeeding Versus Formula-Feeding." October 23, 2020. https://ivypanda.com/essays/benefits-of-breastfeeding-versus-formula-feeding/.

1. IvyPanda . "Benefits of Breastfeeding Versus Formula-Feeding." October 23, 2020. https://ivypanda.com/essays/benefits-of-breastfeeding-versus-formula-feeding/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Benefits of Breastfeeding Versus Formula-Feeding." October 23, 2020. https://ivypanda.com/essays/benefits-of-breastfeeding-versus-formula-feeding/.

- Open access

- Published: 20 February 2018

Breastfeeding knowledge and attitudes of health professional students: a systematic review

- Shu-Fei Yang ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-7056-2613 1 , 3 ,

- Yenna Salamonson 1 , 2 ,

- Elaine Burns 1 &

- Virginia Schmied 1

International Breastfeeding Journal volume 13 , Article number: 8 ( 2018 ) Cite this article

31k Accesses

59 Citations

55 Altmetric

Metrics details

Breastfeeding support from health professionals can be effective in influencing a mother’s decision to initiate and maintain breastfeeding. However, health professionals, including nursing students, do not always receive adequate breastfeeding education during their foundational education programme to effectively help mothers. In this paper, we report on a systematic review of the literature that aimed to describe nursing and other health professional students’ knowledge and attitudes towards breastfeeding, and examine educational interventions designed to increase breastfeeding knowledge and attitudes amongst health professional students.

A systematic review of peer reviewed literature was performed. The search for literature was conducted utilising six electronic databases, CINAHL, MEDLINE, ProQuest, PubMed, Scopus, and Cochrane, for studies published in English from January 2000 to March 2017. Studies focused on nursing students’ or other health professional students’ knowledge, attitudes or experiences related to breastfeeding. Intervention studies to improve knowledge and attitudes, were also included. All papers were reviewed using the relevant Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) checklist.

Fourteen studies were included in the review. This review indicates that in some settings, health professional students demonstrated mid-range scores on breastfeeding attitudes, and their knowledge of breastfeeding was limited, particularly in relation to breastfeeding assessment and management. All of the studies that tested a specialised breastfeeding education programme, appeared to increase nursing students’ knowledge overall or aspects of their knowledge related to breastfeeding. Several factors were found to influence breastfeeding knowledge and attitudes, including timing of maternal and child health curriculum component, previous personal breastfeeding experience, gender, cultural practices and government legislation.

Conclusions

Based on this review, it appears that nursing curriculum, or specialised programmes that emphasise the importance of breastfeeding initiation, can improve breastfeeding knowledge and attitudes and students’ confidence in helping and guiding breastfeeding mothers.

To achieve the health and optimal growth of infants, the World Health Organization (WHO) and the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) recommends that all infants should be exclusively breastfed for the first 6 months and continue to receive breast milk until 2 years of age to supplement other foods [ 1 ]. In addition, the policy statement of American Academy of Paediatrics cites breastfeeding as the ideal form of infant nutrition, providing health benefits for both mothers and infants [ 2 ].