- Recently Active

- Top Discussions

- Best Content

By Industry

- Investment Banking

- Private Equity

- Hedge Funds

- Real Estate

- Venture Capital

- Asset Management

- Equity Research

- Investing, Markets Forum

- Business School

- Fashion Advice

- Technical Skills

- Trading & Investing Guides

Efficient Markets Hypothesis

The efficient market hypothesis (EMH) suggests that financial markets operate in such a way that the prices of equities, or shares in companies, are always efficient.

Elliot currently works as a Private Equity Associate at Greenridge Investment Partners, a middle market fund based in Austin, TX. He was previously an Analyst in Piper Jaffray 's Leveraged Finance group, working across all industry verticals on LBOs , acquisition financings, refinancings, and recapitalizations. Prior to Piper Jaffray, he spent 2 years at Citi in the Leveraged Finance Credit Portfolio group focused on origination and ongoing credit monitoring of outstanding loans and was also a member of the Columbia recruiting committee for the Investment Banking Division for incoming summer and full-time analysts.

Elliot has a Bachelor of Arts in Business Management from Columbia University.

- What Is The Efficient Market Hypothesis (EMH)?

- Variations Of The Efficient Markets Hypothesis

- Are Capital Markets Efficient?

What Is the Efficient Market Hypothesis (EMH)?

The efficient market hypothesis (EMH) suggests that financial markets operate in such a way that the prices of equities, or shares in companies, are always efficient. In simpler terms, these prices accurately reflect the true value of the underlying companies they represent.

The efficient market hypothesis is one of the most foundational theories developed in finance. It was developed by Nobel laureate Eugene Fama in the 1960s and is widely known amongst finance professionals in the industry.

There are many implications arising from this hypothesis; however, the main proposition is that it is impossible to “beat the market” and generate alpha.

What does beating the market or generating alpha mean? Broadly speaking, you can think of how much the return of your risk-adjusted investments exceeds benchmark indices.

For example, a proxy for the US market will be the S&P 500, which covers the top 500 companies in the United States or over 80% of its total market capitalization .

If your portfolio of investments generated an alpha of 3%, then it is considered that your portfolio outperformed the S&P 500 by 3% (assuming that you trade in the US market)

How is it possible that share prices are always efficient and reflect the actual value of the underlying company following the efficient market hypothesis?

It is because, at all times, a company's share price reflects certain relevant available information to all investors who trade upon it, and the type of information required to ensure efficient prices depends on what form of efficiency the market is in.

If you are interested in a profession surrounding capital markets, be it asset management , sales & trading, or even hedge funds, the EMH is a theory you need to know to ace your interviews.

However, this is only one topic in the diverse world of finance that you will truly need to know if you want to break into these careers. To gain a deeper understanding of finance, look at Wall Street Oasis's courses. For a link to our courses, click here .

Key Takeaways

- Developed by Eugene Fama, the EMH suggests that financial markets reflect all available information and that it's impossible to consistently "beat the market" to generate abnormal returns (alpha).

- The EMH has three forms: weak, semi-strong, and strong. Each form describes the extent of information already reflected in stock prices.

- Under this form, stock prices incorporate historical information like past earnings and price movements. Investors can't gain alpha by trading on this historical data as it's already "priced in."

- In this form, stock prices reflect all publicly available information, including recent news and announcements. Even with access to this information, investors can't consistently beat the market.

- The strongest form of EMH incorporates all information, including insider information. Even with insider knowledge, investors can't generate abnormal returns. However, some argue that real-world markets may not fully adhere to this hypothesis due to behavioral biases and inefficiencies.

Variations of the Efficient Markets Hypothesis

According to Eugene Fama, there are three variations of efficient markets:

Semi-strong form

Strong form

Depending on which form the market takes, the share price of companies incorporates different types of information. Let’s go over what kind of information is required for each form of the efficient market.

Weak form efficiency

Under the weak form of efficient markets, share prices incorporate all historical information of stocks. This would typically cover a company’s historical earnings, price movements, technical indicators, etc.

Another way to look at it is that when a market is weakly efficient, it means - there is no predictive power from historical information.

Investors are unlikely to generate alpha from investing in a company just because they saw that the company outperformed earnings estimates last week. That information was already “priced in,” and there is nothing to gain trading off that information.

Semi-strong form efficiency

The semi-strong form of efficiency within markets is believed to be most prevalent across markets. Under this form of efficiency, share prices incorporate all historical information of stocks and go a step further by including all publicly available information.

This implies that share prices practically adjust immediately following the announcement of relevant information to a company’s stock.

What this means is that investors are not able to generate alpha by trading off relevant information that is publicly available, no matter how recent that piece of information became public.

This partially explains why you’ve probably heard those investment gurus tell you to buy the rumors and sell on the news.

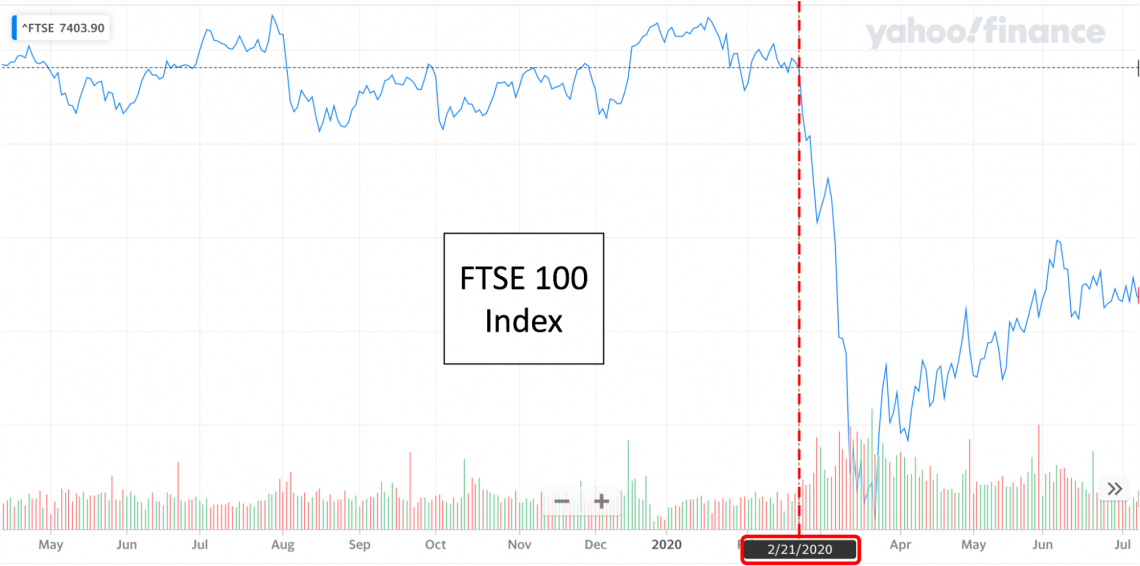

One relevant example would be the reaction from every stock exchange worldwide on specific key dates surrounding the World Health Organization and the Covid-19 pandemic.

The market crashed following specific announcements because, at that time, the market anticipated lockdowns to occur, which would damage every company’s supply chain and sales.

If lockdowns did occur, companies wouldn’t be able to produce goods and services. Furthermore, customers wouldn’t be able to purchase goods, resulting in companies taking a hit on their earnings. And this was exactly what happened.

Although Covid was known since November 2019, If you look at the S&P 500 and the FTSE 100 , they both crashed on the same date (21st February 2020), with the impact on markets being equally significant.

It would be safe to say that this was the date that the market started incorporating the impact of Covid-19 on a company’s share price. It is no coincidence that the World Health Organization also hosted a press conference that day.

You can look at the FTSE 100 and S&P 500 index, which represent the UK and US market conditions. The following images show the drop in benchmark indices due to Covid-19:

Unfortunately, there are a couple of caveats to this example.

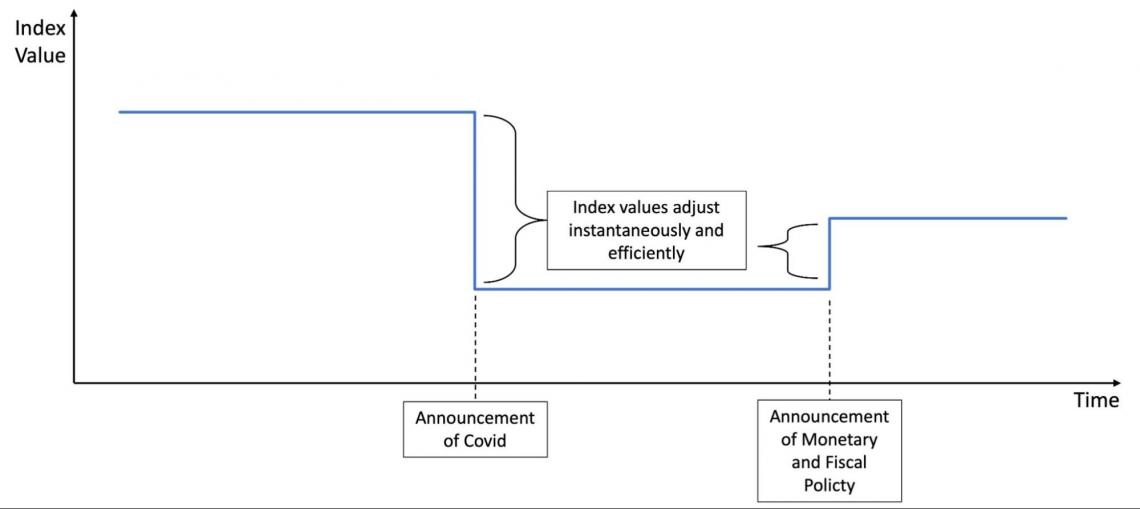

In Eugene Fama’s purest depiction of the semi-strong form of an efficient market hypothesis, prices are meant to adjust instantaneously following the public announcement of relevant information, with the new prices reflecting the market’s new actual value.

When you look at the market’s reaction to Covid-19, the market crash happened gradually over a certain period.

Furthermore, if you look at the FTSE 100 and S&P 500, the index started showing signs of recovery immediately after the market crash.

Broadly speaking, there are two reasons this could have happened:

There was an announcement of new publicly available information with a positive impact on markets

The market had initially overreacted to the Covid-19 pandemic

An excellent example of newly announced publicly available information with a positive impact on markets would be something like the respective countries’ governments and central banks both promoting aggressive monetary and fiscal policies designed to improve economic situations.

Although it is impossible to say, and every investor will have a different opinion on the market, the consensus is that the market has reacted to monetary and fiscal policies. As a result, there was an initial overreaction to Covid-19 in the market.

This is where the practical example strays away from theory. In the market’s reaction to Covid-19, the impact of new information was gradual (but still quick) and argued to be inefficient at the trough.

However, Eugene Fama’s efficient market hypothesis anticipates rapid price movements following the release of public information, and prices are always efficient, moving from one true value to another.

Market indices that genuinely follow the semi-strong form efficient market hypothesis would look something like this:

And this is what the true efficient market hypothesis envisions. There is no exaggeration in this graph, and the market index isn't expected to have any daily fluctuation because it reflects the valid, efficient value pricing in all the publicly available information.

Reaction to new relevant information is instant and accurate, leaving no room for values to readjust over time.

This example applies to all forms of efficient markets, including the weak and strong forms. However, the difference is the type of information that will cause a company's share price to readjust.

Strong form efficiency

The share prices of companies in strongly efficient markets incorporate everything that the semi-strong form efficiency incorporates but go a step further by also incorporating insider information.

This implies that investors who know something about a company that isn't publicly known cannot generate abnormal returns trading off that information.

Generally speaking, you should expect more developed countries to have more efficient markets, mainly because more asset managers are analyzing stocks and more educated individuals make better investment decisions.

However, if any country were likely to display powerfully efficient markets, you would expect them to exist within more corrupt and opaque countries. This is because countries like the US and UK have implemented sanctions against insider trading purely because of how profitable it is.

Investors with insider information are known to have an edge in markets, which is why there are policies in place dictating that asset managers and substantial shareholders must disclose their trades to the Securities and Exchange Commission ( SEC ).

Under Rule 10b-5 , the SEC explicitly states that insiders are prohibited from trading on material non-public information.

In November 2021, a McKinsey partner was charged with insider trading because he assisted Goldman Sachs with its acquisition of GreenSky.

The Mckinsey partner had private information regarding the GreenSky acquisition and purchased multiple call options on GreenSky, profiting over $450,000.

Aside from the fact that the man was blatantly insider trading, the fact that he was able to profit off insider information is evidence that the US market does NOT possess strong form efficiency.

The above is somewhat considered to be proof by contradiction. If markets were efficient, trading off insider information would not let investors generate abnormal returns. But in this case, the Mckinsey partner could make almost half a million dollars!

To put that into perspective, $450 thousand is more than two years of the average investment banking analyst’s total compensation and slightly over four years of base pay.

Are capital markets efficient?

After developing a decent understanding of the efficient market hypothesis, the real question is: is the market truly efficient, and do they follow the EMH? This topic is controversial, and many individuals will support different sides of the argument.

Supporters of the efficient market hypothesis generally believe in traditional neoclassical finance. Neoclassical finance has been around since the twentieth century, and its approach revolves around key assumptions like perfect knowledge or rationality among individuals.

In fact, most of the material taught at university and in textbooks are materials that talk about neoclassical finance - one might argue that the world of finance was built by theories such as the EMH.

However, some of the assumptions in neoclassical finance have always been known to be overly restrictive and not at all realistic. For example, humans are not the objective supercomputers that neoclassical finance believes us to be.

The fact is that humans are ruled by emotions and subjected to behavioral biases. We do not act the same as everyone else, and it is absurd to believe that we all behave rationally or even have perfect knowledge about a subject before making decisions.

Some of the latest developments in academics have been surrounding behavioral finance, with Nobel laureates including Robert Shiller and Richard Thaler (cameo in a classic finance film titled The Big Short) leading the field and relaxing unrealistic assumptions in neoclassical finance.

Aside from being unable to generate alpha, another significant implication arising from the EMH is that investors can blindly purchase any stock in the exchange without any prior analysis and still receive a fair return on equity .

That does not make sense because if everyone did that, then it would be safe to assume that the share prices would be wildly inaccurate and far apart from the company’s actual value.

The fact is that there is some reliance upon financial institutions such as asset managers or arbitrageurs to constantly monitor and exploit inefficiencies within capital markets (such as buying underpriced and shorting overpriced equities) to keep the market efficient.

Therefore, another argument arising from this is the idea that markets are efficiently inefficient where money managers who use costly financial information software such as Bloomberg Terminal or FactSet can gain a competitive edge in the market.

These money managers generate abnormal returns by exploiting inefficiencies within markets, such as longing for undervalued stocks or shorting overvalued stocks. A beneficial outcome of this activity is that market prices are slowly shifting towards efficient values.

The biggest argument supporting the efficient market hypothesis is that many money managers cannot outperform benchmark indices such as the S&P 500 on a year-to-year basis.

That argument is further supported when you compare the average 20-year annual return of the S&P 500 to any hedge fund’s average 20-year yearly return. You will find that MOST money managers underperform compared to the benchmark.

The table below displays the November 2021 return of the top hedge funds. For reference, the S&P 500 had a total return of 26.89% .

Therefore, if you compare the hedge funds to the S&P 500 (ignoring the hedge funds’ December 2021 performance), you can see that only three hedge funds outperformed the index.

Hedge funds are also costly, with many institutions imposing a minimum 2-20 fee structure where there is a 2% fee charged on the AUM of the fund and a 20% fee for any profit above the hurdle rate.

Nevertheless, while the data seems to point to the fact that hedge funds can be somewhat lackluster, a common argument is that the concept of a hedge fund is to “hedge,” which means to protect money.

Therefore, perhaps some hedge funds have a greater purpose of maintaining their AUM rather than growing it despite the fact that hedge funds are known for having the most aggressive investment strategies .

Overall, being a part of a hedge fund is still highly lucrative. For example, Kenneth Griffin, CEO of Citadel LLC, had total compensation of over $2 billion in 2021, whereas David Solomon, CEO of Goldman Sachs, had a total payment of $35 million in 2021.

If you want to make $2 billion a year in a hedge fund one day, you need to polish up your interviewing skills. To impress your interviewers, look at Wall Street Oasis’s Hedge Fund Interview Prep Course. For a link to our courses, click here .

Everything You Need To Master Financial Modeling

To Help You Thrive in the Most Prestigious Jobs on Wall Street.

Researched and authored by Jasper Lim | Linkedin

Free Resources

To continue learning and advancing your career, check out these additional helpful WSO resources:

- Call Option

- Eurex Exchange

- Fallen Angel

Get instant access to lessons taught by experienced private equity pros and bulge bracket investment bankers including financial statement modeling, DCF, M&A, LBO, Comps and Excel Modeling.

or Want to Sign up with your social account?

11.5 Efficient Markets

Learning outcomes.

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Understand what is meant by the term efficient markets .

- Understand the term operational efficiency when referring to markets.

- Understand the term informational efficiency when referring to markets.

- Distinguish between strong, semi-strong, and weak levels of efficiency in markets.

Efficient Markets

For the public, the real concern when buying and selling of stock through the stock market is the question, “How do I know if I’m getting the best available price for my transaction?” We might ask an even broader question: Do these markets provide the best prices and the quickest possible execution of a trade? In other words, we want to know whether markets are efficient. By efficient markets , we mean markets in which costs are minimal and prices are current and fair to all traders. To answer our questions, we will look at two forms of efficiency: operational efficiency and informational efficiency.

Operational Efficiency

Operational efficiency concerns the speed and accuracy of processing a buy or sell order at the best available price. Through the years, the competitive nature of the market has promoted operational efficiency.

In the past, the NYSE (New York Stock Exchange) used a designated-order turnaround computer system known as SuperDOT to manage orders. SuperDOT was designed to match buyers and sellers and execute trades with confirmation to both parties in a matter of seconds, giving both buyers and sellers the best available prices. SuperDOT was replaced by a system known as the Super Display Book (SDBK) in 2009 and subsequently replaced by the Universal Trading Platform in 2012.

NASDAQ used a process referred to as the small-order execution system (SOES) to process orders. The practice for registered dealers had been for SOES to publicly display all limit orders (orders awaiting execution at specified price), the best dealer quotes, and the best customer limit order sizes. The SOES system has now been largely phased out with the emergence of all-electronic trading that increased transaction speed at ever higher trading volumes.

Public access to the best available prices promotes operational efficiency. This speed in matching buyers and sellers at the best available price is strong evidence that the stock markets are operationally efficient.

Informational Efficiency

A second measure of efficiency is informational efficiency, or how quickly a source reflects comprehensive information in the available trading prices. A price is efficient if the market has used all available information to set it, which implies that stocks always trade at their fair value (see Figure 11.12 ). If an investor does not receive the most current information, the prices are “stale”; therefore, they are at a trading disadvantage.

Forms of Market Efficiency

Financial economists have devised three forms of market efficiency from an information perspective: weak form, semi-strong form, and strong form. These three forms constitute the efficient market hypothesis. Believers in these three forms of efficient markets maintain, in varying degrees, that it is pointless to search for undervalued stocks, sell stocks at inflated prices, or predict market trends.

In weak form efficient markets, current prices reflect the stock’s price history and trading volume. It is useless to chart historical stock prices to predict future stock prices such that you can identify mispriced stocks and routinely outperform the market. In other words, technical analysis cannot beat the market. The market itself is the best technical analyst out there.

As an Amazon Associate we earn from qualifying purchases.

This book may not be used in the training of large language models or otherwise be ingested into large language models or generative AI offerings without OpenStax's permission.

Want to cite, share, or modify this book? This book uses the Creative Commons Attribution License and you must attribute OpenStax.

Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/principles-finance/pages/1-why-it-matters

- Authors: Julie Dahlquist, Rainford Knight

- Publisher/website: OpenStax

- Book title: Principles of Finance

- Publication date: Mar 24, 2022

- Location: Houston, Texas

- Book URL: https://openstax.org/books/principles-finance/pages/1-why-it-matters

- Section URL: https://openstax.org/books/principles-finance/pages/11-5-efficient-markets

© Jan 8, 2024 OpenStax. Textbook content produced by OpenStax is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License . The OpenStax name, OpenStax logo, OpenStax book covers, OpenStax CNX name, and OpenStax CNX logo are not subject to the Creative Commons license and may not be reproduced without the prior and express written consent of Rice University.

- Investing 101

- The 4 Best S&P 500 Index Funds

- World's Top 20 Economies

- Stock Basics Tutorial

- Options Basics Tutorial

- Economics Basics

- Mutual Funds

- Bonds/Fixed Income

- Commodities

- Company News

- Market/Economy News

- Apple (AAPL)

- Tesla (TSLA)

- Amazon (AMZN)

- Facebook (FB)

- Netflix (NFLX)

- Create an Account

- Join a Game

- Create a Game

- Budgeting/Saving

- Small Business

- Wealth Management

- Broker Reviews

- Charles Schwab Review

- E*TRADE Review

- Robinhood Review

- Advisor Insights

- Investopedia 100

- Join Advisor Insights

- Your Practice

- Investing for Beginners

- Become a Day Trader

- Trading for Beginners

- Technical Analysis

- All Courses

- Trading Courses

- Investing Courses

- Financial Professional Courses

- Advisor Login

- Newsletters

Financial Analysis

Investing Strategy

- Bonds / Fixed Income

- Real Estate

- International / Global

- Alternative Investments

- Asset Allocation

- Sustainable Investing

The Weak, Strong and Semi-Strong Efficient Market Hypotheses

Though the efficient market hypothesis as a whole theorizes that the market is generally efficient, the theory is offered in three different versions: weak, semi-strong and strong.

The basic efficient market hypothesis posits that the market cannot be beaten because it incorporates all important determinative information into current share prices . Therefore, stocks trade at the fairest value, meaning that they can't be purchased undervalued or sold overvalued . The theory determines that the only opportunity investors have to gain higher returns on their investments is through purely speculative investments that pose substantial risk.

The three versions of the efficient market hypothesis are varying degrees of the same basic theory. The weak form suggests that today’s stock prices reflect all the data of past prices and that no form of technical analysis can be effectively utilized to aid investors in making trading decisions. Advocates for the weak form efficiency theory believe that if fundamental analysis is used, undervalued and overvalued stocks can be determined, and investors can research companies' financial statements to increase their chances of making higher-than-market-average profits.

Semi-Strong Form

The semi-strong form efficiency theory follows the belief that because all information that is public is used in the calculation of a stock's current price , investors cannot utilize either technical or fundamental analysis to gain higher returns in the market. Those who subscribe to this version of the theory believe that only information that is not readily available to the public can help investors boost their returns to a performance level above that of the general market.

Strong Form

The strong form version of the efficient market hypothesis states that all information – both the information available to the public and any information not publicly known – is completely accounted for in current stock prices, and there is no type of information that can give an investor an advantage on the market. Advocates for this degree of the theory suggest that investors cannot make returns on investments that exceed normal market returns, regardless of information retrieved or research conducted.

There are anomalies that the efficient market theory cannot explain and that may even flatly contradict the theory. For example, the price/earnings (P/E) ratio shows that firms trading at lower P/E multiples are often responsible for generating higher returns. The neglected firm effect suggests that companies that are not covered extensively by market analysts are sometimes priced incorrectly in relation to their true value and offer investors the opportunity to pick stocks with hidden potential. The January effect shows historical evidence that stock prices – especially smaller cap stocks – tend to experience an upsurge in January.

Though the efficient market hypothesis is an important pillar of modern financial theories and has a large backing, primarily in the academic community, it also has a large number of critics. The theory remains controversial, and investors continue attempting to outperform market averages with their stock selections.

Related Articles

Has the efficient market hypothesis been proven correct or incorrect, is the stock market efficient, what does the efficient market hypothesis have to say about fundamental analysis, what is the efficient market hypothesis, why does the efficient market hypothesis state that technical analysis is bunk, top 7 market anomalies investors should know.

- Privacy Policy

- Terms of Use

Forgot password? New user? Sign up

Existing user? Log in

Efficient Market Hypothesis

Already have an account? Log in here.

The efficient market hypothesis is a theory that market prices fully reflect all available information, i.e. that market assets, like stocks , are worth what their price is. The theory suggests that it's impossible for any individual investor to leverage superior intelligence or information to outperform the market, since markets should react to information and adjust themselves. Any intelligent investor buying a stock is doing so because they believe the stock is worth more than the data (typically historical returns, projected returns, macroeconomic trends , industry trends, etc.) support it being worth. They think that the data is wrong and undervaluing the stock. Economists counter that investors are either buying riskier stocks and undervaluing the risk or succeeding through chance. Put another way, as Burton Malkiel says in his book, A Random Walk Down Wall Street , the efficient market hypothesis means that "a blindfolded chimpanzee throwing darts at the Wall Street Journal could select a portfolio that would do as well as the experts."

As this, essentially, suggests that the tens of thousands of experts who work as active investors are worthless, it has been heavily critiqued. These critiques, themselves, come from successful investors like Warren Buffett who points to the undervaluing of "value stocks" (as opposed to the sexier growth stocks), behavioral economists who point to humanity's inefficiencies, and experts who have used valuations techniques, like dividend yields and price-earnings ratios to generate higher returns.

French mathematician, Louis Bachelier is considered to many to be the first to apply probability theory to markets. [1] Though his work didn't reach a wide audience until the 1950s and 1960s. Eugene Fama is credited, over the course of his career, for much of modern theories of efficient markets, expanding Bachelier's initial work, and starting with Fama's publication, in 1965 of his PhD thesis. Both used mathematical models of random walks and were influenced by Hayek's 1945 argument that markets are the most efficient way to aggregate information.

Weak, Semi-Strong, and Strong Efficiency

Attacks (and responses to attacks) on the efficient market hypothesis, response to attacks on the efficient market hypothesis, how stocks respond to interest rates, investment strategies for proponents of the efficient market hypothesis, possible paradoxes.

Efficient markets are said to exist in varying degrees of efficiency, generally categorized as weak, semi-strong, and strong. These degrees of strength pertain markets responding to information.

In strong efficiency markets, all public and private information is reflected in market prices. This includes insider information (and thus if there are laws prohibiting insider information from being made public, strong efficiency is not in place). In such a market investors, overall, cannot earn excess returns because the market has priced in historical and future (trend) information. Those individual investors are said to consistently outperform the market, maybe doing so simply because any log-normal distribution of thousands of fund managers will include some that consistently outperform the average.

In semi-strong efficiency markets, investors respond very quickly to new information. Because of the speed of information being responded to, investors cannot make excess returns from information. (There are cases where investors set up communications networks to arbitrage information faster than other investors could, but this is a market inefficiency that was corrected for over time). The contention around semi-strong markets is that they have factored in all available information, so fundamental and technical analysis (i.e. doing analysis from available information) does not reveal underpriced securities for investors to make excess returns from.

In weak efficiency markets, there is a chance that investors can make some money in the short term, that markets only reflect all currently available information in the long term. However, markets do, eventually, reflect all available information, and it contends that historical data does not have a relationship with future prices, i.e. Investors cannot use past data to predict future prices and gain excess returns.

There is one anomaly to weak efficiency, one that even Fama has acknowledged, and that has been observed in multiple international markets: the momentum effect. Stocks that have historically gone up in the past 3-12 months, tend to continue to go up. Stocks that have historically gone down in the past 3-12 months, tend to continue to go down.

Behavioral Economics Behavioral economists (and behavioral psychologists) study the cognitive bias that humans have and that lead to irrational decision making. At a high level, these biases could prove that investors are inefficient, both signaling that they aren't going to beat the market (consistent with EMH) and that there are arbitrage opportunities to exploit their inefficiencies (inconsistent with EMH). For instance, people have been shown to employ something called hyperbolic discounting, i.e. given two rewards, humans tend to prefer the reward that comes sooner to the one that comes later. And investment fund managers can suffer from this same bias; in some cases their bonus this year is predicated on their returns this year, not their long-term returns, potentially leading to making okay short-term decisions at the expense of great long-term options. Other economists point to herd mentality , loss aversion , and the sunk cost fallacy for reasons why investors will not outperform the market.

Bubbles Stock market bubbles--like the dot-com bubble of the late 90s, and the housing market bubble of the early 2000s--are acknowledged analomies in the EMH. For a period of time markets (and investors) systematically overestimated a set of assets, until they came crashing down. Economists contend that even rare statistical events are allowed under log-normal distributions. But investors counter that there is an arbitrage opportunity here--that some savvy investors made money by realizing these assets were inflated, and that once the market crashed, the assets were deflated. Economists, in turn, counter back that it's hard or abnormal to realize this in real time, and that few investors arbitraged successfully. For instance, in the case of the dot-com bubble, the available information actually supported some of the prevailing high valuations. With internet usage doubling every few months, one could conceive that this would continue (as it inevitably did with a handful of dot-com era companies--Amazon, Ebay, Yahoo--deservedly achieving the same or higher valuations that they had back in the late 90s).

Successful Investors and Value Investing Some notable investors, Warren Buffett being one, contend that investment techniques, like value investing , have let them outperform the market, even when most other investors do only as well as index funds would. Value investing is a technique, pioneered by Benjamin Graham and David Dodd, in which the investor, generally, buys securities that are underpriced according to some form of analysis (see dividend yields and P/E ratios below).

In a famous 1984 lecture at Columbia Business School, Warren Buffett talked about nine successful investors that are not merely statistically outliers on a log-normal distribution curve of efficient markets, “So these are nine records of 'coin-flippers' from Graham-and-Doddsville. I haven’t selected them with hindsight from among thousands. It’s not like I am reciting to you the names of a bunch of lottery winners...I selected these men years ago based upon their framework for investment decision-making...It’s very important to understand that this group has assumed far less risk than average; note their record in years when the general market was weak. While they differ greatly in style, these investors are, mentally, always buying the business, not buying the stock. A few of them sometimes buy whole businesses. Far more often they simply buy small pieces of businesses. Their attitude, whether buying all or a tiny piece of a business, is the same. Some of them hold portfolios with dozens of stocks; others concentrate on a handful. But all exploit the difference between the market price of a business and its intrinsic value.”

These, and other value investors, look at fundamental analysis like the following to determine predictable patters: Bar graph of 10-year stock returns grouped by dividend yields [2]

Have high dividend yields : Dividends are cash returns that companies choose to pass on to their shareholders. For instance a company might return $100 million to it's shareholders by giving $1 for each of the 1 million shares outstanding. The chart to the right takes the dividend yield of the S&P 500 each quarter from 1926 - 1990 and then finds the ten-year return (through 2000). It shows that investors have earned a greater rate of return from high-dividend yielding stocks. However, as Malkiel notes: "These findings are not necessarily inconsistent with efficiency. Dividend yields of stocks tend to be high when interest rates are high, and they tend to be low when interest rates are low (see below ). Consequently, the ability of initial yields to predict returns may simply reflect the adjustment of the stock market to general economic conditions. Moreover, the use of dividend yields to predict future returns has been ineffective since the mid-1980s. Dividend yields have been at the three percent level or below continuously since the mid-1980s, indicating very low forecasted returns." [2] This low-dividend trend has continued through the 21st century, with many companies electing for share repurchases as a theoretically "better way" to return capital to investors. Bar graph of 10-year stock returns grouped by P/E ratios [2]

Have low price-to-earning multiples or have low price-to-book ratios (P/E ratios): Another favored metric of value investors is the Price to earnings ratio. Some companies, like Facebook, have relatively high multiples of earnings, as of December 1st 2016, it was \(\approx 44\) meaning that the total return Facebook earned for the previous four quarters was \(\frac{1}{44}\)th of the stock price. Or, put another way, it would take 44 years, at the current rate of net earnings for Facebook to pay an investor back for their purchase price. The key here being that investors who are choosing to buy Facebook believe those earnings will increase. However the size of this P/E ratio would, traditionally, make it not a good candidate for value investors. In the chart to the right, S&P 500 stocks are grouped by their quarterly P/E ratios from 1926 - 1990 and then the average of their ten-year return (through 2000) is calculated. Stocks with P/E ratios under 9.9 outperformed others in this study, and are generally considered "value stocks" or stocks bought "at a discount". The famous saying for value investors is "buy low, sell high" or buy when the stock is undervalued, sell when it's at par or overvalued. Where the advocate of the efficient market hypothesis would respond that the market prices in all information stocks will only be temporarily under or over valued.

The primary evidence for the efficient market hypothesis is the preponderance of studies showing that active investors do not outperform the market. There is a substantial body of work showing that mutual fund managers do not outperform the market [3] [4] [5] [6] . This is even true for investors that have performed well in the past. Like stocks, past performance is not an indicator of future success. And many have concluded that the fees that investment advisors charge cause their customers to underperform the market overall.

A number of studies have specifically looked at how the market responses to new information , theorizing that if it is an efficient market individual announcements should not, on average, raise the price of stocks because this information would already be priced in. [7] [8]

Fama's response to significant anomalies , where the market over or under reacts, is that "an efficient market generates categories of events that individually suggest that prices over-react to information. But in an efficient market, apparent underreaction will be about as frequent as overreaction. If anomalies split randomly between underreaction and overreaction, they are consistent with market efficiency." "The important point is that the literature does not lean cleanly toward either [over or under reaction] as the behavioral alternative to market efficiency. "

Stocks are highly sensitive to interest rates. If low-risk government bonds general significantly high levels of interest, investors will prefer them to their risky stock alternatives. As such, stock prices can go up or down based on interest rate prices (again the market should price in expectations about whether interest rates will change). As an example, suppose that stocks are priced as the present value of the expected future stream of dividends: \[r = \frac{D}{P} + g\] Where \(r\) is the rate of return, \(D\) is the dividend yield, \(P\) is the price, and \(g\) is the growth rate.

Suppose the "riskless rate" on government securities is 4%, and the risk premium on equity investments is 2%. Also suppose that there is a stock that is expected to have a growth rate of 2% and a dividend of $2 per share, what should the equity be priced at? This expected rate of return, if the interest rate is 4% and the risk premium is 2%, would be 6%. And formula is as follows: \(r = \frac{D}{P} + g\) \(0.06 = $2.00/P + 0.02\) \(0.04 = $2.00/P\) \(P = $2.00/0.04 = $50.00\) The equity should be priced at $50.

In the example on the efficient market hypothesis wiki, we said that in a market where the "riskless rate" is 4%, the risk premium is 2%, the dividend yield is $2, and the expected growth rate is 2% then the stock, priced only as the present value of the expected value of the stream of future dividends, should be worth $50.00. This follows from the formula: \[r= \frac{D}{P} + g\] What happens when the interest rate rises to 5%? How much should the stock price increase or decrease if nothing else changes?

The principal suggestion from Efficient Market Hypothesis Advocates is to minimize costs (both fees and taxes if possible). Warren Buffett himself has agreed that most investors do not outperform the market, saying in his 2013 letter [9] that after his passing, his money will be invested for his family in the following way: "10% of the cash in short-term government bonds and 90% in a very low-cost S&P 500 index fund. (I suggest Vanguard’s.) I believe the trust’s long-term results from this policy will be superior to those attained by most investors--whether pension funds, institutions or individuals--who employ high-fee managers."

In general, large institutions (pension funds, endowments, foundations, etc.) have followed this advice and have been shifting from actively managed funds to passively managed ones . According to Morningstar's 2015 Annual report, " In 2015, actively managed mutual funds suffered more than $200 billion of net outflows, compared with net inflows of more than $400 billion for passively managed funds." [10]

In private, some active investors gleefully appreciate the spread of the Efficient Market Hypothesis and the shift to passively managed funds. Because the fewer people actively managing funds means fewer people to compete with. They would argue that active managers play a role in ensuring market efficiency and with fewer active managers the market will become less efficient, presenting the few that are left with more opportunities. I.E. that as more people believe in the efficient market hypothesis and passively manage their funds in indexes, the markets will become less efficient and open up opportunities for active money managers.

Overall, some consider the whole theory something of a paradox. Statistically it seems valid, but there are numerous anomalies and numerous investors with long term periods of success (for instance Berkshire Hathaway's 51 year compound annual return is 19-20% a year versus the S&P's 9.7%). There is compelling evidence on both sides, but one of the greatest advantages the theory has propelled is to point out investors' historical overreliance on investment professionals and the massive industry predicated on this need.

- Bachelier, L. The Theory of Speculation . Retrieved December 1st 2016, from http://press.princeton.edu/chapters/s8275.pdf

- Malkiel, B. The Efficient Market Hypothesis and Its Critics . Retrieved December 1st 2016, from http://www.princeton.edu/ceps/workingpapers/91malkiel.pdf

- Jensen, M. The Performance of Mutual Funds in the Period 1945-1964 . Retrieved November 23rd 2016, from http://www.e-m-h.org/Jens68.pdf

- Fama, E. Efficient Capital Markets: A Review of Theory and Empirical Work . Retrieved November 23rd, 2016, from http://www.jstor.org/stable/2325486

- Fama, E. Efficient Capital Markets: II . Retrieved November 23rd 2016, from http://faculty.chicagobooth.edu/jeffrey.russell/teaching/Finecon/readings/fama.pdf

- Sommer, J. Who Routinely Trounces the Stock Market? Try 2 Out of 2,862 Funds . Retrieved November 23rd 2016, from http://www.nytimes.com/2014/07/20/your-money/who-routinely-trounces-the-stock-market-try-2-out-of-2862-funds.html

- Ball, R., & Brown, P. An Empirical Evaluation of Accounting Income Numbers . Retrieved December 1st 2016, from http://www.drthomaswu.com/uicfat/1.pdf

- Fama, E., Fisher, L., Jensen, M., & Roll, R. The Adjustment of Stock Prices to New Information . Retrieved December 1st 2016, from https://www.jstor.org/stable/2525569?seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents

- Hathaway, B. Berkshire Hathaway . Retrieved November 29th 2016, from http://www.berkshirehathaway.com/letters/2013ltr.pdf

- Morningstar, . 2015 Annual Report . Retrieved December 1st 2106, from https://corporate.morningstar.com/us/documents/PR/Morningstar-Annual-Report-2015.pdf

Problem Loading...

Note Loading...

Set Loading...

Efficient Market Hypothesis

- Living reference work entry

- Later version available View entry history

- First Online: 01 January 2016

- Cite this living reference work entry

- Burton G. Malkiel 2

241 Accesses

7 Citations

A capital market is said to be efficient if it fully and correctly reflects all relevant information in determining security prices. Formally, the market is said to be efficient with respect to some information set, ϕ, if security prices would be unaffected by revealing that information to all participants. Moreover, efficiency with respect to an information set, ϕ, implies that it is impossible to make economic profits by trading on the basis of ϕ.

This chapter was originally published in The New Palgrave: A Dictionary of Economics , 1st edition, 1987. Edited by John Eatwell, Murray Milgate and Peter Newman

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

Institutional subscriptions

Bibliography

Bachelier, L. 1900. Théorie de la speculation . Annales de l’Ecole normale Superieure , 3rd series, 17: 21–86. Trans. by A.J. Boness in The random character of stock market prices , ed. P.H. Cootner. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1967.

Google Scholar

Ball, R. 1978. Anomalies in relationships between securities’ yields and yield-surrogates. Journal of Financial Economics 6(2–3): 103–126, June/September, 1981.

Article Google Scholar

Banz, R. 1981. The relationship between return and market value of common stocks. Journal of Financial Economics 9(1): 3–18.

Basu, S. 1977. Investment performance of common stocks in relation to their price earnings ratios: A test of the efficient markets hypothesis. Journal of Finance 32(3): 663–682.

Basu, S. 1983. The relationship between earnings’ yield, market value and the return of NYSE common stocks: Further evidence. Journal of Financial Economics 12(1): 129–156.

Cornell, B., and R. Roll. 1981. Strategies for pairwise competitions in markets and organizations. Bell Journal of Economics 12(1): 201–213.

Cowles, A. 1933. Can stock market forecasters forecast? Econometrica 1(3): 309–324.

Cowles, A., and H. Jones. 1937. Some posteriori probabilities in stock market action. Econometrica 5(3): 280–294.

Dodd, P. 1981. The effect on market value of transactions in the market for corporate control. In Proceedings of seminar on the analysis of security prices , CRSP. Chicago: University of Chicago.

Fama, E. 1965. The behavior of stock market prices. Journal of Business 38(1): 34–105.

Fama, E., and M. Blume. 1966. Filter rules and stock market trading. Security Prices: A Supplement, Journal of Business 39(1): 226–241.

Fama, E., L. Fisher, M. Jensen, and R. Roll. 1969. The adjustment of stock prices to new information. International Economic Review 10(1): 1–21.

French, K. 1980. Stock returns and the weekend effect. Journal of Financial Economics 8(1): 55–69.

Friend, I., F. Brown, E. Herman, and D. Vickers. 1962. A study of mutual funds . Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office.

Granger, D., and O. Morgenstern. 1963. Spectral analysis of New York stock market prices. Kyklos 16: 1–27.

Grossman, S., and J. Stiglitz. 1980. On the impossibility of informationally efficient markets. American Economics Review 70(3): 393–408.

Gultekin, M., and N. Gultekin. 1983. Stock market seasonality, international evidence. Journal of Financial Economics 12(4): 469–481.

Jaffe, J. 1974. The effect of regulation changes on insider trading. Bell Journal of Economics and Management Science 5(1): 93–121.

Jaffe, J., and R. Westerfield. 1984. The week-end effect in common stock returns: The international evidence . Unpublished manuscript, University of Pennsylvania.

Jensen, M. 1969. Risk, the pricing of capital assets, and the evaluation of investment portfolios. Journal of Business 42(2): 167–247.

Jensen, M. 1978. Some anomalous evidence regarding market efficiency. Journal of Financial Economics 6(2–3): 95–101.

Keim, D. 1983. Size related anomalies and stock return seasonality: Further empirical evidence. Journal of Financial Economics 12(1): 13–32.

Kendall, M. 1953. The analysis of economic time series. Part I: Prices. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society 96(1): 11–25.

Kleidon, A. 1986. Variance bounds tests and stock price valuation models. Journal of Political Economy 94(5): 953–10001.

Kraus, A., and H. Stoll. 1972. Price impacts of block trading on the New York Stock Exchange. Journal of Finance 27(3): 569–588.

Malkiel, B. 1980. The inflation-beater’s investment guide . New York: Norton.

Malkiel, B. 1985. A random walk down Wall Street , 4th ed. New York: Norton.

Mandelbrot, B. 1966. Forecasts of future prices, unbiased markets, and martingale models. Security Prices: A Supplement, Journal of Business 39(1): 242–255.

Marsh, T., and R. Merton. 1983. Aggregate dividend behavior and its implications for tests of stock market rationality . Working Paper, Sloan School of Management.

Merton, R. 1980. On estimating the expected return on the market: An exploratory investigation. Journal of Financial Economics 8(4): 323–361.

Osborne, M. 1959. Brownian motions in the stock market. Operations Research 7(2): 145–173.

Pearson, K., and Lord Rayleigh. 1905. The problem of the random walk. Nature 72: 294, 318, 342.

Rendleman, R., C. Jones, and H. Latané. 1982. Empirical anomalies based on unexpected earnings and the importance of risk adjustments. Journal of Financial Economics 10(3): 269–287.

Roberts, H. 1959. Stock market ‘patterns’ and financial analysis: Methodological suggestions. Journal of Finance 14(1): 1–10.

Roberts, H. 1967. Statistical versus clinical prediction of the stock market . Unpublished manuscript, CRSP. Chicago: University of Chicago.

Roll, R. 1984. Orange juice and weather. American Economic Review 74(5): 861–880.

Samuelson, P. 1965. Proof that properly anticipated prices fluctuate randomly. Industrial Management Review 6(2): 41–49.

Scholes, M. 1972. The market for securities; substitution versus price pressure and the effects of information on share prices. Journal of Business 45(2): 179–211.

Shiller, R.J. 1981. Do stock prices move too much to be justified by subsequent changes in dividends? American Economic Review 71(3): 421–436.

Solnik, B. 1973. Note on the validity of the random walk for European stock prices. Journal of Finance 28(5): 1151–1159.

Thompson, R. 1978. The information content of discounts and premiums on closed-end fund shares. Journal of Financial Economics 6(2–3): 151–186.

Watts, R. 1978. Systematic ‘abnormal’ returns after quarterly earnings announcements. Journal of Financial Economics 6(2–3): 127–150.

Working, H. 1934. A random difference series for use in the analysis of time series. Journal of the American Statistical Association 29: 11–24.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

http://link.springer.com/referencework/10.1007/978-1-349-95121-5

Burton G. Malkiel

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Editor information

Editors and affiliations, copyright information.

© 1987 The Author(s)

About this entry

Cite this entry.

Malkiel, B.G. (1987). Efficient Market Hypothesis. In: The New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics. Palgrave Macmillan, London. https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-349-95121-5_42-1

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-349-95121-5_42-1

Received : 12 August 2016

Accepted : 12 August 2016

Published : 03 November 2016

Publisher Name : Palgrave Macmillan, London

Online ISBN : 978-1-349-95121-5

eBook Packages : Springer Reference Economics and Finance Reference Module Humanities and Social Sciences Reference Module Business, Economics and Social Sciences

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

Chapter history

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-349-95121-5_42-2

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-349-95121-5_42-1

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Oblivious Investor

Low-Maintenance Investing with Index Funds and ETFs

- 2024 Tax Brackets

- 2023 Tax Brackets

- How Are S-Corps Taxed?

- How to Calculate Self-Employment Tax

- LLC vs. S-Corp vs. C-Corp

- SEP vs. SIMPLE vs. Solo 401(k)

- How to Calculate Amortization Expense

- How to Calculate Cost of Goods Sold

- How to Calculate Depreciation Expense

- Contribution Margin Formula

- Direct Costs vs. Indirect Costs

- 401k Rollover to IRA: How, Why, and Where

- What’s Your Funded Ratio?

- Why Invest in Index Funds?

- 8 Simple Portfolios

- How is Social Security Calculated?

- How Social Security Benefits Are Taxed

- When to Claim Social Security

- Social Security Strategies for Married Couples

- Deduction Bunching

- Donor-Advised Funds: What’s the Point?

- Qualified Charitable Distributions (QCDs)

Get new articles by email:

Oblivious Investor offers a free newsletter providing tips on low-maintenance investing, tax planning, and retirement planning.

Join over 20,000 email subscribers:

Articles are published every Monday. You can unsubscribe at any time.

Efficient Market Hypothesis: Strong, Semi-Strong, and Weak

If I were to choose one thing from the academic world of finance that I think more individual investors need to know about, it would be the efficient market hypothesis.

The name “efficient market hypothesis” sounds terribly arcane. But its significance is huge for investors, and (at a basic level) it’s not very hard to understand.

So what is the efficient market hypothesis (EMH)?

As professor Eugene Fama (the man most often credited as the father of EMH) explains*, in an efficient market, “the current price [of an investment] should reflect all available information…so prices should change only based on unexpected new information.”

It’s important to note that, as Fama himself has said, the efficient market hypothesis is a model, not a rule. It describes how markets tend to work. It does not dictate how they must work.

EMH is typically broken down into three forms (weak, semi-strong, and strong) each with their own implications and varying levels of data to back them up.

Weak Efficient Market Hypothesis

The weak form of EMH says that you cannot predict future stock prices on the basis of past stock prices. Weak-form EMH is a shot aimed directly at technical analysis. If past stock prices don’t help to predict future prices, there’s no point in looking at them — no point in trying to discern patterns in stock charts.

From what I’ve seen, most academic studies seem to show that weak-form EMH holds up pretty well. (Take, for example, the recent study which tested over 5,000 technical analysis rules and showed them to be unsuccessful at generating abnormally high returns.)

Semi-Strong Efficient Market Hypothesis

The semi-strong form of EMH says that you cannot use any published information to predict future prices. Semi-strong EMH is a shot aimed at fundamental analysis. If all published information is already reflected in a stock’s price, then there’s nothing to be gained from looking at financial statements or from paying somebody (i.e., a fund manager) to do that for you.

Semi-strong EMH has also held up reasonably well. For example, the number of active fund managers who outperform the market has historically been no more than can be easily attributed to pure randomness .

Semi-strong EMH does not appear to be ironclad, however, as there have been a small handful of investors (e.g., Peter Lynch, Warren Buffet) whose outperformance is of a sufficient degree that it’s extremely difficult to explain as just luck.

The trick, of course, is that it’s nearly impossible to identify such an investor in time to profit from it. You must either:

- Invest with a fund manager after only a few years of outperformance (at which point his/her performance could easily be due to luck), or

- Wait until the manager has provided enough data so that you can be sure that his performance is due to skill (at which point his fund will be sufficiently large that he’ll have trouble outperforming in the future).

Strong Efficient Market Hypothesis

The strong form of EMH says that everything that is knowable — even unpublished information — has already been reflected in present prices. The implication here would be that even if you have some inside information and could legally trade based upon it, you would gain nothing by doing so.

The way I see it, strong-form EMH isn’t terribly relevant to most individual investors, as it’s not too often that we have information not available to the institutional investors.

Why You Should Care About EMH

Given the degree to which they’ve held up, the implications of weak and semi-strong EMH cannot be overstated. In short, the takeaway is that there’s very little evidence indicating that individual investors can do anything better than simply buy & hold a low-cost, diversified portfolio .

*Update: The video from which this quote came has since been taken offline.

New to Investing? See My Related Book:

- Asset Allocation: Why it's so important, and how to determine your own,

- How to to pick winning mutual funds,

- Roth IRA vs. traditional IRA vs. 401(k),

- Click here to see the full list .

A Testimonial:

- Read other reviews on Amazon

A good point to keep in mind is that even if the EMH models aren’t a perfect model of the stock market- if it is close enough that technical analysis or fundamental analysis won’t give you a real advantage then it doesn’t make sense to try them. A Random Walk Down Wall Street: The Time-Tested Strategy for Successful Investing presents that case very well.

-Rick Francis

Wonderfully concise summary, Mike.

Just for completeness, re: the Semi-Strong EMH, there’s a third option – you could try to invest in stocks and beat the market yourself.

I know, I know – but before I get my hat I’d argue that there’s benefits to this approach over picking one or more active fund managers, in that your dealing charges *may* be lower than the fund’s charges (and at least they’re transparent and under your control) and also you don’t have to try to predict two potentially understandable things – a manager’s performance AND the performance of the sort of stocks he invests in (or even a third – whether he or she is going to stick around).

Of course, a tracker fund sidesteps all of this for most people to deliver better than average results compared to funds, and only slightly worse results compared to the market. 🙂

Click here to read more, or enter your email address in the blue form to the left to receive free updates.

Recommended Reading

Investing Made Simple: Investing in Index Funds Explained in 100 Pages or Less See it on Amazon Read customer reviews on Amazon

My Latest Books

After the Death of Your Spouse: Next Financial Steps for Surviving Spouses See it on Amazon

More than Enough: A Brief Guide to the Questions That Arise After Realizing You Have More Than You Need See it on Amazon

Market Efficiency

The efficient market hypothesis.

The EMH asserts that financial markets are informationally efficient with different implications in weak, semi-strong, and strong form.

LEARNING OBJECTIVE

Differentiate between the different versions of the Efficient Market Hypothesis

- In weak-form efficiency, future prices cannot be predicted by analyzing prices from the past.

- In semi-strong-form efficiency, it is implied that share prices adjust to publicly available new information very rapidly and in an unbiased fashion, such that no excess returns can be earned by trading on that information.

- In strong-form efficiency, share prices reflect all information, public and private, and no one can earn excess returns.

Buying or selling securities of a publicly held company by a person who has privileged access to information concerning the company's financial condition or plans.

A stock or commodity market analysis technique which examines only market action, such as prices, trading volume, and open interest.

An analysis of a business with the goal of financial projections in terms of income statement, financial statements and health, management and competitive advantages, and competitors and markets.

The efficient-market hypothesis (EMH) asserts that financial markets are "informationally efficient". In consequence of this, one cannot consistently achieve returns in excess of average market returns on a risk-adjusted basis, given the information available at the time the investment is made.

There are three major versions of the hypothesis: weak, semi-strong, and strong.

- The weak-form EMH claims that prices on traded assets (e.g., stocks, bonds, or property) already reflect all past publicly available information.

- The semi-strong-form EMH claims both that prices reflect all publicly available information and that prices instantly change to reflect new public information.

- The strong-form EMH additionally claims that prices instantly reflect even hidden or "insider" information.

Weak-Form Efficiency

In weak-form efficiency, future prices cannot be predicted by analyzing prices from the past. Excess returns cannot be earned in the long run by using investment strategies based on historical share prices or other historical data. Technical analysis techniques will not be able to consistently produce excess returns, though some forms of fundamental analysis may still provide excess returns. Share prices exhibit no serial dependencies, meaning that there are no "patterns" to asset prices. This implies that future price movements are determined entirely by information not contained in the price series. Hence, prices must follow a random walk. This "soft" EMH does not require that prices remain at or near equilibrium, but only that market participants not be able to systematically profit from market "inefficiencies". However, while EMH predicts that all price movement (in the absence of change in fundamental information) is random (i.e., non-trending), many studies have shown a marked tendency for the stock markets to trend over time periods of weeks or longer and that, moreover, there is a positive correlation between degree of trending and length of time period studied (but note that over long time periods, the trending is sinusoidal in appearance). Various explanations for such large and apparently non-random price movements have been promulgated.

Semi-Strong-Form Efficiency

In semi-strong-form efficiency, it is implied that share prices adjust to publicly available new information very rapidly and in an unbiased fashion, such that no excess returns can be earned by trading on that information. Semi-strong-form efficiency implies that neither fundamental analysis nor technical analysis techniques will be able to reliably produce excess returns. To test for semi-strong-form efficiency, the adjustments to previously unknown news must be of a reasonable size and must be instantaneous. To test for this, consistent upward or downward adjustments after the initial change must be looked for. If there are any such adjustments it would suggest that investors had interpreted the information in a biased fashion and, hence, in an inefficient manner.

Strong-Form Efficiency

In strong-form efficiency, share prices reflect all information, public and private, and no one can earn excess returns. If there are legal barriers to private information becoming public, as with insider trading laws, strong-form efficiency is impossible, except in the case where the laws are universally ignored. To test for strong-form efficiency, a market needs to exist where investors cannot consistently earn excess returns over a long period of time. Even if some money managers are consistently observed to beat the market, no refutation even of strong-form efficiency follows–with hundreds of thousands of fund managers worldwide, even a normal distribution of returns (as efficiency predicts) should be expected to produce a few dozen "star" performers.

Critics have blamed the belief in rational markets for much of the late 2000s financial crisis. In response, proponents of the hypothesis have stated that market efficiency does not mean having no uncertainty about the future, that market efficiency is a simplification of the world which may not always hold true, and that the market is practically efficient for investment purposes for most individuals.

- Search Search Please fill out this field.

- Assets & Markets

- Mutual Funds

Efficient Markets Hypothesis (EMH)

EMH Definition and Forms

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/ScreenShot2020-03-23at2.04.43PM-59de96b153e540c498f1f1da8ce5c965.png)

What Is Efficient Market Hypothesis?

What are the types of emh, emh and investing strategies, the bottom line, frequently asked questions (faqs).

The Efficient Market Hypothesis (EMH) is one of the main reasons some investors may choose a passive investing strategy. It helps to explain the valid rationale of buying these passive mutual funds and exchange-traded funds (ETFs).

The Efficient Market Hypothesis (EMH) essentially says that all known information about investment securities, such as stocks, is already factored into the prices of those securities. If that is true, no amount of analysis can give you an edge over "the market."

EMH does not require that investors be rational; it says that individual investors will act randomly. But as a whole, the market is always "right." In simple terms, "efficient" implies "normal."

For example, an unusual reaction to unusual information is normal. If a crowd suddenly starts running in one direction, it's normal for you to run that way as well, even if there isn't a rational reason for doing so.

There are three forms of EMH: weak, semi-strong, and strong. Here's what each says about the market.

- Weak Form EMH: Weak form EMH suggests that all past information is priced into securities. Fundamental analysis of securities can provide you with information to produce returns above market averages in the short term. But no "patterns" exist. Therefore, fundamental analysis does not provide a long-term advantage, and technical analysis will not work.

- Semi-Strong Form EMH: Semi-strong form EMH implies that neither fundamental analysis nor technical analysis can provide you with an advantage. It also suggests that new information is instantly priced into securities.

- Strong Form EMH: Strong form EMH says that all information, both public and private, is priced into stocks; therefore, no investor can gain advantage over the market as a whole. Strong form EMH does not say it's impossible to get an abnormally high return. That's because there are always outliers included in the averages.

EMH does not say that you can never outperform the market . It says that there are outliers who can beat the market averages. But there are also outliers who lose big to the market. The majority is closer to the median. Those who "win" are lucky; those who "lose" are unlucky.

Proponents of EMH, even in its weak form, often invest in index funds or certain ETFs. That is because those funds are passively managed and simply attempt to match, not beat, overall market returns.

Index investors might say they are going along with this common saying: "If you can't beat 'em, join 'em." Instead of trying to beat the market, they will buy an index fund that invests in the same securities as the benchmark index.

Some investors will still try to beat the market, believing that the movement of stock prices can be predicted, at least to some degree. For that reason, EMH does not align with a day trading strategy. Traders study short-term trends and patterns. Then, they attempt to figure out when to buy and sell based on these patterns. Day traders would reject the strong form of EMH.

For more on EMH, including arguments against it, check out the EMH paper from economist Burton G. Malkiel. Malkiel is also the author of the investing book "A Random Walk Down Main Street." The random walk theory says that movements in stock prices are random.

If you believe that you can't predict the stock market, you would most often support the EMH. But a short-term trader might reject the ideas put forth by EMH, because they believe that they are able to predict changes in stock prices.

For most investors, a passive, buy-and-hold , long-term strategy is useful. Capital markets are mostly unpredictable with random up and down movements in price.

When did the Efficient Market Hypothesis first emerge?

At the core of EMH is the theory that, in general, even professional traders are unable to beat the market in the long term with fundamental or technical analysis . That idea has roots in the 19th century and the "random walk" stock theory. EMH as a specific title is sometimes attributed to Eugene Fama's 1970 paper "Efficient Capital Markets: A Review of Theory and Empirical Work."

How is the Efficient Market Hypothesis used in the real world?

Investors who utilize EMH in their real-world portfolios are likely to make fewer decisions than investors who use fundamental or technical analysis. They are more likely to simply invest in broad market products, such as S&P 500 and total market funds.

Corporate Finance Institute. " Efficient Markets Hypothesis ."

IG.com. " Random Walk Theory Definition ."

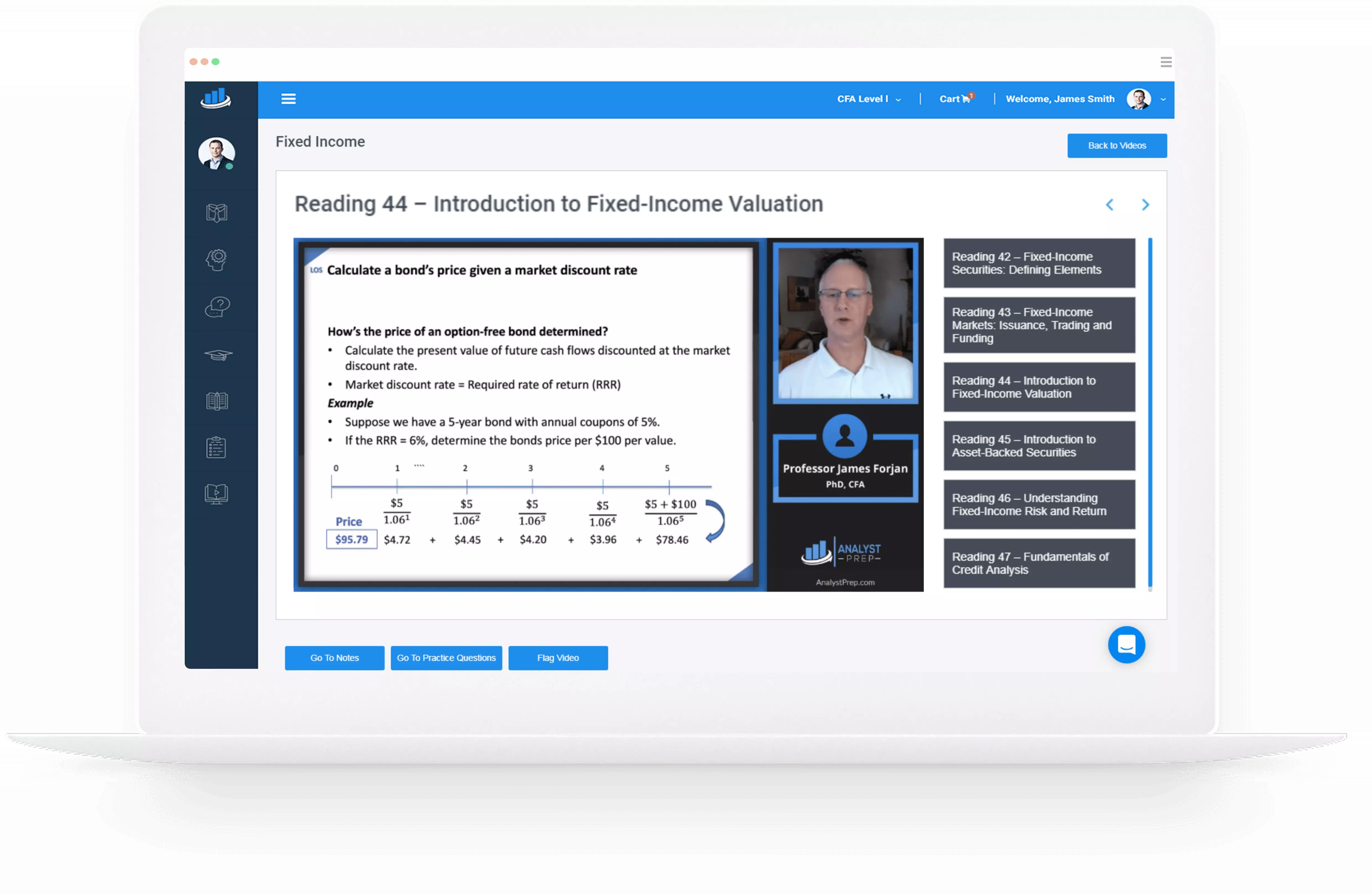

Save 10% on All AnalystPrep 2024 Study Packages with Coupon Code BLOG10 .

- Payment Plans

- Product List

- Partnerships

- Try Free Trial

- Study Packages

- Levels I, II & III Lifetime Package

- Video Lessons

- Study Notes

- Practice Questions

- Levels II & III Lifetime Package

- About the Exam

- About your Instructor

- Part I Study Packages

- Part I & Part II Lifetime Package

- Part II Study Packages

- Exams P & FM Lifetime Package

- Quantitative Questions

- Verbal Questions

- Data Insight Questions

- Live Tutoring

- About your Instructors

- EA Practice Questions

- Data Sufficiency Questions

- Integrated Reasoning Questions

Weak, Semi-strong, and Strong Forms Market Efficiency

Eugene Fama developed a framework of market efficiency that laid out three forms of efficiency: weak, semi-strong, and strong. Each form is defined with respect to the available information that is reflected in prices. Investors trading on available information that is not priced into the market would earn abnormal returns, defined as excess risk-adjusted returns.

In the weak-form efficient market hypothesis, all historical prices of securities have already been reflected in the market prices of securities. In other words, technicians – those trading on analysis of historical trading information – should earn no abnormal returns. Research has shown that this is likely the case in developed markets, but less developed markets may still offer the opportunity to profit from technical analysis.

Semi-strong Form

In a semi-strong-form efficient market, prices reflect all publicly known and available information, including all historical price information. Under this assumption, analyzing any public financial disclosures made by a company to determine a stock’s intrinsic value would be futile since every detail would be taken into account in the stock’s market price. Similarly, an investor could not earn consistent abnormal returns by acting on surprise announcements since the market would quickly react to the new information.

Strong Form

In a strong-form efficient market, security prices fully reflect both public and private information. Therefore, insiders could not generate abnormal returns by trading on private information because it would already figure into market prices. However, researchers find that markets are generally not strong-form efficient as abnormal profits can be earned when nonpublic information is used.

In the following graph, we can clearly see that the weak form of market efficiency reflects only past market data. In contrast, the strong form reflects all past data, public market information, and insider information.

Market Prices Reflect

$$ \begin{array}{cccc} \textbf{Forms of market efficiency} & \textbf{Past market data} & \textbf{Public information} & \textbf{Private information} \\ \hline \text{Weak form} & \checkmark & & \\ \text{Semi-strong form} & \checkmark & \checkmark & \\ \text{Strong form} & \checkmark & \checkmark & \checkmark \\ \end{array} $$

Question If a skilled fundamental financial analyst and an insider trader all earn the same long-run risk-adjusted returns, what form of market efficiency is likely to apply? Weak form. Strong form. Semi-strong form. Solution The correct answer is B . Since the insider trader can’t even earn higher risk-adjusted returns than the skilled fundamental financial analyst, the market must be strong-form efficient.

Offered by AnalystPrep

Key Differences Between US GAAP and IFRS

Standard 1(a) – knowledge of the law, types of equity indices.

Types of equity indices include broad market, multi-market, sector, and style indices. Broad... Read More

Public vs. Private Equity Securities

The public securities market is larger than the private securities market, but private... Read More

Weighting Methods Used in Index Constr ...

There is no perfect index weighting method, as each one has its own... Read More

Overvalued, Fairly Valued, and Underva ...

When a security’s current market price is approximately equal to its value estimate,... Read More

- Cost of Capital

- Marginal Cost of Capital

- Required Rate of Return

- Risk Free Rate

- Inflation Premium

- Default Premium

- Liquidity Premium

- Maturity Premium

- Cost of Equity

- Cost of New Equity

- Cost of Preferred Stock

- Flotation Costs

- Cost of Debt

- Sustainable Growth Rate

- Internal Growth Rate

- After-Tax Cost of Debt

- Net Asset Value

- Pure Play Method

- Unlevered Beta

- Strong Form Market Efficiency

- Semi-strong Form Market Efficiency

- Weak Form Market Efficiency

- Theoretical Ex-rights Price

- Yield to Maturity (YTM)

- Current Yield

Semi-strong form of market efficiency exists where security prices already reflect all publicly available information and it is not possible to earn excess return.

Semi-strong form of market efficiency lies between the two other forms of market efficiency, namely the weak form and strong form . A semi-strong form encompasses a weak-form which means that if a market is semi-strong efficient, it is also weak-form efficient.

When a market is semi-strong form efficient, neither technical analysis, which is based on past pattern of return, nor fundamental analysis, which incorporates current information, can help predict future price movements. However, non-public information can be used to earn above average return.

Semi-strong form of efficiency is typically tested by studying how prices and volumes respond to specific events. If price reflect new information quickly, markets are semi-strong form efficient. Such events may include special dividends, stock splits , lawsuits, mergers and acquisitions, tax changes, etc. Evidence suggests that developed markets might be semi-strong efficient while developing markets are not.

Alex held 100 shares of Cure Inc. which he had purchased on 1 January 20X3 for $25 per share. Cure Inc. is a company engaged in research and development of new antibiotics against resistant microbes. Alex is not an active investor so he does not checks the stock performance daily. On 14 January 20X2 (Sunday), he came across an article shared by his friend on Facebook. The article was published on 11 January 20X2 (Friday). According to the article, Cure Inc. has failed in a project worth a net present value of $20 million. Total outstanding shares of Cure Inc. are 5 million. Alex sold off his holding for $2,050 (at $20.5 per share) in the opening hours of 15 January 20X2 (Monday). He was glad that he minimized his loss but towards the end of 15 January 20X2, the company's stock price had even climbed to $21. He is wondering what happened.

The market seems to be semi-strong form efficient. The market had adjusted itself to the public information on Friday (11 January 20X2) as soon as the market came to know about it. Alex should not have used this public information to project a decline on Monday. The drop in price is almost equal to the net present value per share no longer available ($20 million divided by 5 million).