You are using an outdated browser. Please upgrade your browser or activate Google Chrome Frame to improve your experience.

90+ Mexican Slang Words and Expressions (with Audio and Examples)

Looking to have a huge head start when you travel to Mexico?

You’ve gotta learn the slang.

In this post, I’m going to give you a brief introduction to the country’s unique version of Spanish—and by the time we’re done, you’ll be better prepared to navigate a slang-filled conversation with Mexicans!

The Most Common Mexican Slang Words and Expressions

1. ¡qué padre — cool, 2. me vale madre — i don’t care, 3. poca madre — really cool, 4. fresa — preppy.

- 5. ¡Aguas! — Watch out!

6. En el bote — In jail

7. estar crudo — to be hungover, 8. ¡a huevo — **** yeah, 9. chilango — someone from mexico city, 10. te crees muy muy — you think you’re something special, 11. ese — dude, 12. metiche — busybody, 13. pocho / pocha — a mexican who’s left mexico, 14. naco — tacky, 15. cholo — mexican gangster, 16. güey — dude, 17. carnal — close friend, 18. ¿neta — really.

- 19. Eso que ni que — I agree

20. Ahorita — Right now

21. ni modo — whatever, 22. no hay tos — no problem, 23. sale — okay, sure, 24. coda / codo — someone who’s cheap, 25. tener feria — to have money/change, 26. buena onda — good vibes, 27. ¿qué onda — what’s up, 28. ¡viva méxico — long live mexico.

- 29. Pendejo — Jerk

- 30. Cabrón — Mean, not very smart, awesome

- 31. Pedo — Drunk, problem

- 32. Pinche — Ugly, cheap

33. Verga — Male genitalia

34. chingar — to f***, 35. ¡no manches / ¡no mames — no way, don’t mess with me, 36. está cañón — difficult, 37. chido — nice, cool, 38. chulo / chula — good-looking person, 39. ¿a poco — really, 40. ¡órale — right on, 41. chela — beer, 42. la tira — the cops, 43. ¿mande — what, 44. suave — cool, 45. gacho — mean, 46. ándale — hurry up, 47. chale — give me a break, 48. chamba / chambear — work, 49. bronca — problem, 50. paro — favor, 51. chido / chida — cool, 52. padre — awesome, 53. chingón — badass, 54. chamba — job, 55. vato — guy, 56. morro — kid, 57. jefa / jefe — mom/dad, 58. vieja / viejo — girlfriend, wife/boyfriend, husband, 59. carnalito — little brother, 60. chiquitín — little one, 61. chavito / chavita — young guy/young girl, 62. camión — bus, 63. chulear — to show off, 64. chingar — to bother, 65. estrenar — to wear or use something for the first time, 66. guacala — yuck, 67. huevón — lazy person, 68. jato — car, 69. mamacita — attractive woman, 70. pisto — money, 71. ¿que pex — what’s up, 72. rola — song, 73. ¿sapbe — what’s up , 74. valedor — friend, 75. vato loco — crazy guy, 76. wacha — look / watch, 77. ¡ya nos cargó el payaso — we’re in trouble, 78. cuate — buddy, 79. jeta — face, 80. madrazo — a strong hit, 81. nalga — buttocks, 82. ñero — dark-skinned person, 83. pacheco — drunk, 84. pirata — fake, 85. relajo — mess, 86. riata — belt, 87. sobres — okay, got it, 88. tapado — conceited, 89. troca — truck, 90. zarape — blanket or shawl, what you need to know about mexican spanish, resources for learning more mexican slang, quick guide to mexican slang, na’atik language and culture institute, why you should learn mexican slang, mexican slang quiz: test yourself, and one more thing….

Download: This blog post is available as a convenient and portable PDF that you can take anywhere. Click here to get a copy. (Download)

Mexican slang could be a language of its own.

Just a word of warning: some terms on this list may be considered rude and should be used with caution.

This phrase’s literal translation, “How father!”, doesn’t make much sense at all, but it can be understood to mean “cool!” or “awesome!”

¡Conseguí entradas para Daddy Yankee! (I got tickets for Daddy Yankee!)

¡ Qué padre , güey! (Awesome, dude!)

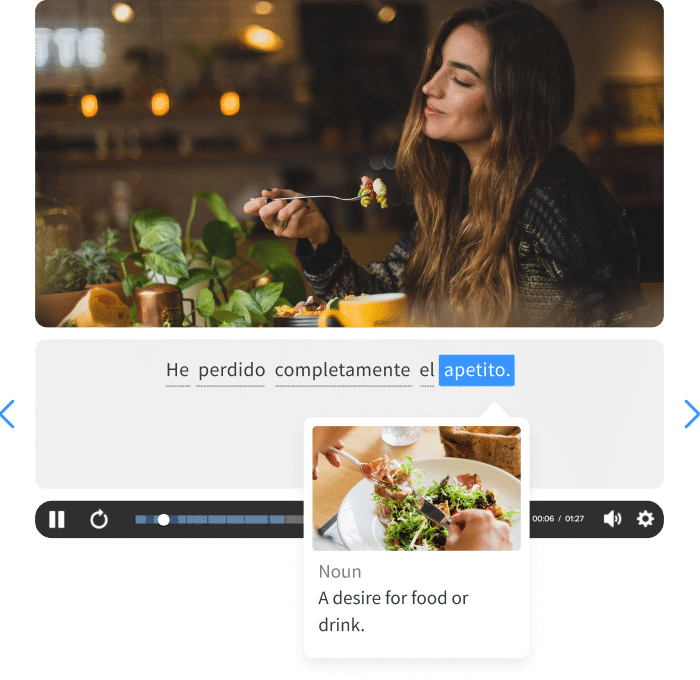

- Thousands of learner friendly videos (especially beginners)

- Handpicked, organized, and annotated by FluentU's experts

- Integrated into courses for beginners

This phrase is used to say “I don’t care.” It’s not quite a curse, but it can be considered offensive in more formal situations.

If used with the word que (that), remember you need to use the subjunctive .

Me vale madre lo que haga con su vida. (I don’t care what he does with his life).

Literally translated as “little mother,” this phrase is used to describe something really cool.

Once again, this phrase can be considered offensive (and is mostly used among groups of young men).

Esta canción está poca madre . (This song is really cool).

Literally a “strawberry,” a fresa is not something you want to be.

Somewhat similar to the word “preppy” in the United States , a fresa is a young person from a wealthy family who’s self-centered, superficial and materialistic.

Ella es una fresa. (She’s preppy/rich/stuck up).

- Interactive subtitles: click any word to see detailed examples and explanations

- Slow down or loop the tricky parts

- Show or hide subtitles

- Review words with our powerful learning engine

5. ¡Aguas! — Watch out!

This phrase is used throughout Mexico to mean “be careful!” or “look out!”

Literally meaning “waters,” it’s possible that this usage evolved from housewives throwing buckets of water to clean the sidewalks in front of their homes.

¡Aguas! El piso está mojado. (Be careful! The floor’s wet).

The word bote means “can” (as in a can of soda).

However, when a Mexican says someone is “en el bote,” they mean someone is “in the slammer,” “in jail.”

Adrián no puede venir, ¡está en el bote ! (Adrian can’t come, he’s in jail!)

Estar crudo means “to be raw,” as in food that hasn’t been cooked.

However, if someone in Mexico tells you they’re crudo, it means they’re hungover because they’ve drunk too much alcohol.

Estoy muy crudo hoy. (I’m really hungover today).

- Learn words in the context of sentences

- Swipe left or right to see more examples from other videos

- Go beyond just a superficial understanding

Huevos (eggs) are often used to denote a specific part of the male anatomy —you can probably guess which—and they’re also used in a wide variety of slang phrases.

¡A huevo! is a vulgar way to show excitement or approval. Think “eff yeah!” without the self-censorship.

¡Ganamos el partido! (We won the game!)

¡A huevo! Me alegra. (**** yeah! I’m glad)

This slang term means something, usually a person, who comes from Mexico City.

Calling someone a chilango is saying that they’re representative of the culture of the city.

¿Eres chilango ? (Are you from Mexico City?)

This literally means “you think you’re very very” but the slang meaning is more of “you think you’re something special,” or “you think you’re all that.”

Often, this is used to power down someone who’s boastful or thinks they’re better than anyone else.

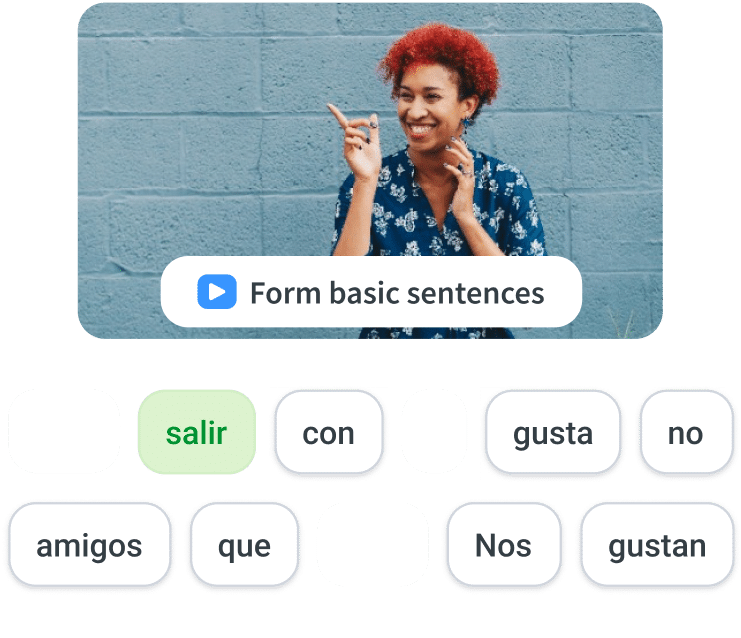

- FluentU builds you up, so you can build sentences on your own

- Start with multiple-choice questions and advance through sentence building to producing your own output

- Go from understanding to speaking in a natural progression.

Te crees muy muy desde que conseguiste ese trabajo. (You think you’re all that since you got that job).

Supposedly, in the 1960s members of a Mexican gang called the Sureños (“Southerners”) used to call each other “ese” (after the first letter of the gang’s name).

However, in the ’80s, the word ese started to be used to refer to men in general, meaning something like “dude” or “dawg”.

It’s also possible ese originated from expressions like ese vato (“that guy”), and from that, the word ese started to be used to refer to a man.

“¿Qué pedo, ese ?” “What up, dawg?”

Metiche is a slang word for someone who loves to get the scoop on everyone’s everything.

Some people would refer to this sort of person as a busybody!

¿De qué hablaste con tu amiga? (What did you talk about with your friend?)

Nada, ¡no seas tan metiche ! (Nothing, don’t be such a busybody!)

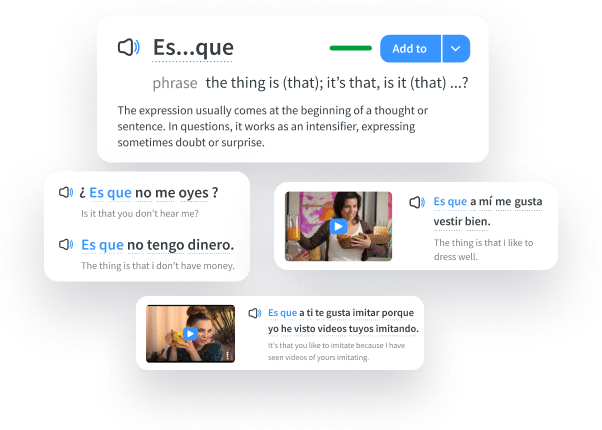

- Images, examples, video examples, and tips

- Covering all the tricky edge cases, eg.: phrases, idioms, collocations, and separable verbs

- No reliance on volunteers or open source dictionaries

- 100,000+ hours spent by FluentU's team to create and maintain

This Mexican slang term refers to a Mexican who’s left Mexico or someone who’s perhaps forgotten their Mexican roots or heritage.

It can be used as just an observatory expression, but also as a derogatory slang word used to point out that someone’s at fault for not remembering their heritage.

Mis primos pochos vienen a visitar este fin de semana. (My pocho cousins are coming to visit this weekend).

Naco is a word used to describe someone or something poorly educated and bad-mannered.

The closest American equivalent would be “tacky” or “ghetto.”

The word has its origins in insulting indigenous and poor people, so be careful with this word!

Me parece un poco naco . (It seems a bit tacky).

Although the word cholo can have several meanings, it often refers to Mexican gangsters, especially Mexican American teens and youngsters who are in a street gang.

Vi unos cholos en la esquina. (I saw some gang members on the corner).

This one is pronounced like the English word “way” and it’s one of the most quintessential Mexican slang words.

Originally used to mean “a stupid person,” the word eventually morphed into a term of endearment similar to the English “dude.”

¡Apúrate, güey ! (Hurry up, dude!)

Carnal comes from Spanish carne (meat).

It’s perhaps for this reason that carnal is used to describe a close friend who’s like a sibling to you, carne de tu carne or flesh of your flesh.

Allí está mi carnala Laura . (There’s my close friend Laura).

“Truth?” or “really?” is what someone’s saying when they use this little word.

This popular conversational interjection is used to fill a lull in the chatter or to give someone the opportunity to come clean on an exaggeration.

Oftentimes, though, it’s just said to express agreement with the last comment in a conversation or to clarify something.

¿ Neta ? Pero ¿qué pasó? (Really? But what happened?)

19. Eso que ni que — I agree

Don’t try to translate this literally—just know that this convenient phrase means that you’re in agreement with whatever’s being discussed.

Es muy bueno para bailar. (He’s really good at dancing).

Sí, baila mejor que todos, eso que ni que . (Yes, he dances better than everyone, no doubt about it).

This translates as “little now” but the small word means right now, or at this very moment.

¡Tenemos que irnos ahorita ! (We have to leave right now!)

Ni modo , which can be literally translated as “not way” or “either way,” is possibly one of the most popular Mexican expressions.

It’s generally used to say “eh, whatever” or “it is what it is.”

Ni modo can also be used with que (that) and a present subjunctive to say you can’t do something at the moment or there’s no way you’d do it.

It’s like saying “there’s no way” or “are you nuts?” in English.

Ni modo , hay mejores chicas/chicos en el mundo. (Oh well, there are better girls/guys in the world)

Ni modo que conteste, güey. (There’s no way I’m answering, man).

No hay tos literally means “there’s no cough,” but it’s used to say “no problem” or “don’t worry about it.”

Lo siento, me olvidé mi billetera. ¿Tienes plata? (Sorry, I forgot my wallet. Do you have cash?)

No, pero no hay tos , comamos en la casa. (No, but no problem, let’s eat at home).

Sale means “okay,” “sure,” “yeah” or “let’s do it,” so it’s normally used in situations when someone suggests doing something and you agree.

It can also be used as a question tag when you want someone’s opinion or to see if they’re on the same page as you.

¿Vamos al concierto? (Shall we go to the concert?)

Sale , pero tendrás que prestarme lana. (Sure, but you’ll have to lend me some money.)

Codo literally means “elbow” in English but Mexican slang has turned it into a term used to describe someone who’s cheap.

It can be applied to either gender, so pay attention to the -a or -o ending of this descriptive noun.

¡Ese codo ni pagó la cena! (That cheapskate didn’t even pay for dinner!)

Feria means “fair” so the literal translation of this expression is “to have or be fair.”

However, feria also refers to coins when it’s used in Mexico. So, the phrase basically means “to have money” or “to have pocket change.”

¿Tienes feria ? (Do you have money?).

Buena onda literally translates to “good wave” but it’s used to indicate that there are good vibes or a good energy present.

Tienes buena onda . (You give off good vibes).

This slangy Mexican expression translates to “what wave?” but is a cool way to ask “what’s up?”

It’s another feel-good, casual conversational expression that really adds a lot of good feelings to any chat.

¿ Qué onda ? ¿Cómo has estado? (What’s up? How have you been?)

¡Viva México! literally means “long live Mexico!”

It’s the unifying phrase that says the country should grow, prosper and see happy times for its citizens and visitors.

It’s often shortened to “¡viva!” which means the same as the full phrase .

¡Ganamos el mundial! ¡ Viva México ! (We won the world cup! Long live Mexico!)

29. P endejo — Jerk

Pendejo is one of those magical words that appear in almost every Spanish variety but have a different meaning depending on where you are.

In Mexico, it has a rather rude meaning: “unpleasant or stupid person,” “jerk.”

No me hables, pendejo . (Don’t talk to me, jerk).

30. C abrón — Mean, not very smart, awesome

While technically cabrón means “big [male] goat,” it has plenty of other meanings.

Used as a rude word its meaning is quite similar to pendejo, but cabrón is higher in the rudeness scale: meaning unpleasant, mean or not very bright.

But change the tone a bit and you might, instead, be saying someone is awesome!

The word can even be used in place of the f-bomb, very often following bien— very, to mean you’re really awesome at doing something.

Soy bien cabrón jugando a Minecraft. (I’m friggin’ awesome at playing Minecraft).

31. P edo — Drunk, problem

A pedo is a fart, literally.

This word has lots of different meanings, depending on how you say it and the situation:

- Estar pedo — to be drunk

- Peda — drinking session

- Ser buen pedo — to give off good vibes

- Ser mal pedo — to be unfriendly or hostile

- ¿Qué pedo? — what’s up?

- Pedo — problem or argument

- Ponerse al pedo — to want a fight, or to have an attitude of defiance

- ¿Qué pedo contigo, cabrón? (What’s your problem, man?)

Here’s Mexican actress Salma Hayek explaining qué pedo and other Mexican slang:

32. P inche — Ugly, cheap

The word pinche may sound quite unproblematic for many Spanish speakers because it literally means “kitchen helper.”

However, when in Mexico, this word goes rogue and acquires a couple of interesting meanings.

It can mean “ugly,” “substandard,” “poor” or “cheap,” but it can also be used as an a ll-purpose enhancer, much like the meaner cousin of “hecking” is used in English.

Eres un pinche loco . (You’re effing crazy).

Originally, the verga was the horizontal beam from which a ship’s sails were hung, but this word has come to mean a man’s schlong in Spanish nowadays.

You can also use this word as a standalone exclamation with the meaning of the f-bomb.

Here are a few more uses of the word:

- Creerse verga — to think you’re all that

- Valer verga — to be worthless

- Irse a la verga — a “lovely” way of telling someone to eff off

- Tus palabras me valen verga . (Your words mean nothing to me).

Chingar means “to do the deed.” It’s Mexico’s version of the f-word. Simple.

Chingar is a word that’s prevalent in Mexican culture in its various forms and meanings.

¡Deja de chingar ! (Stop f***ing around!)

These two phrases are essentially one and the same, hence why they’re grouped together.

Literally meaning “don’t stain!” and “don’t suck,” these are used to say “no way! You’re kidding me!” or “don’t mess with me!”

No manches is totally benign, but no mames is considered vulgar and can potentially be offensive.

¡No manches! ¿Pensé que habían terminado? (No way! I thought they had broken up?)

Here are actors Eva Longoria and Michael Peña explaining no manches and other Mexican slang words:

When you say that something is está cañón (literally, “it’s cannon”), you’re saying “it’s hard/difficult.”

Some believe that the phrase arose as a more polite euphemism for está cabrón.

As a Spaniard, I find this meaning quite funny, because estar cañón means “to be very attractive” in Castilian Spanish.

El examen estuvo bien cañón . (The exam was very difficult).

This word is simply a fun way to say “nice” or “cool” in Mexican Spanish.

Despite its status as slang, it’s not vulgar or offensive in the least—so have fun with it!

It can be used as both a standalone exclamation (¡qué chido! — cool!) or as an adjective.

Tienes un carro bien chido. (You have a really cool car).

When it comes to Mexico, chulo is used as an adjective to refer to people you find hot, good-looking or pretty.

You can also use it to refer to things with the meaning of “cute,” however if you travel to Spain, don’t use this word to refer to people—since a chulo is “a pimp.”

¿Viste ese chulo en la panadería? (Did you see that hot guy in the bakery?)

There’s no way to translate this one literally, it just comes back as nonsense. Mexicans, however, use it to say “really?” when they’re feeling incredulous.

Ale dijo que ganó la lotería! (Alex said that he won the lottery!)

¿ A poco ? ¿Lo crees? (Really? Do you believe him?)

This exclamation basically means “right on!” or in some situations is used as a message of approval like “let’s do it!”

Órale is another Mexican slang word that’s considered inoffensive and is appropriate for almost any social situation.

It can be said quickly and excitedly or offered up with a long, drawn-out “o” sound.

Creo que te puedo ganar. (I think I can beat you).

¡Órale! A ver. (Bring it on! Let’s see).

Simple enough, chela is a Mexican slang word for beer.

In other parts of Latin America, chela is a woman who’s blond (usually with fair skin and blue eyes).

No one is quite sure if there’s a link between the two, and it seems unclear how the word came to mean “beer” in the first place.

¿Quieres tomar unas chelas ? (Do you want to have a few beers?)

A tira is a “strip,” but when you use it as a Mexican slang word, you mean the cops.

¡Aguas! ¡Ahí viene la tira ! (Watch out! The fuzz are coming!)

This is used in Mexico in place of ¿qué? or ¿cómo? to respond when someone says your name.

Luis, ¿estás allí? (Luis, are you there?)

¿ Mande ? ¿Me llamaste? (What? Did you call me?)

Technically, suave translates to “soft,” but suave is a way to say “cool.”

¡Ese mural es suave ! (That mural is cool!)

This literally means “slouch,” but it’s used to say something is mean or ugly .

Enrique es gacho . (Enrique is mean.)

Andar means “to walk,” so ándale is a shortened version of the verb combined with the suffix “- le ,” a sort of grammatical placeholder that adds no meaning to the word.

Use this to tell someone to hurry up .

¡ Ándale ! Necesitamos estar ahi a las 8. (Hurry up! We need to be there at 8.)

Chale doesn’t really have a clear literal translation, but it’s most often used to show your annoyance.

It’s similar to the English “give me a break.”

Su coche tardará dos semanas en arreglarse. (Your car will take two weeks to fix.)

¡Chale! (Give me a break!)

Chamba and chambear mean “work” and “to work,” respectively.

No me gusta mi chamba. (I don’t like my job.)

The word bronca means “problem,” and it’s used in expressions like no hay bronca (“no problem”) and tengo broncotas (“I’m in big trouble”).

Mi familia tiene broncas con mi hermano. (My family has problems with my brother.)

Though the official word for “favor” in Spanish is the cognate favor, paro is another way of referring to a favor in Mexico.

Hazme el paro means “do me a favor.”

Puedes hacerme el paro ? (Can you do me a favor?)

Though “cool” in Spanish is commonly expressed as genial , chido is a colloquial way of describing something as cool or awesome in Mexican slang.

Esa película estuvo bien chida . (That movie was really cool!)

Similar to chido , padre is another slang term used to convey that something is awesome or great.

¡La fiesta estuvo bien padre ! (The party was really awesome!)

Chingón is an informal term used to describe something or someone as extraordinary, impressive, or badass.

¡Ese tatuaje está bien chingón ! (That tattoo is really badass!)

Chamba is a slang term used to refer to work or a job.

Tengo mucha chamba esta semana . (I have a lot of work this week.)

Vato is a slang term for a guy or dude.

Ese vato es muy amable . (That guy is very friendly.)

Morro is an informal term for a young boy.

Mi hermanito es un buen morro . (My little brother is a good kid.)

Jefa and jefo, which both mean “boss” are just informal terms for “mom” and “dad.”

Mi jefa siempre cocina delicioso . (My mom always cooks deliciously.)

Vieja and viejo , which technically mean “old,” are similar to the English saying of “old man,” referring to a boyfriend, or “old lady,” referring to one’s girlfriend or wife.

Salí con mi vieja al cine . (I went to the movies with my girlfriend.)

Carnalito is a diminutive form of carnal , referring to a younger brother.

Mi carnalito siempre quiere jugar . (My little brother always wants to play.)

Chiquitín is an affectionate term for someone small or younger.

¡Hola, chiquitín ! ¿Cómo estás? (Hi, little one! How are you?)

These are affectionate slang terms for a young man or young woman.

Ese chavito es muy talentoso . (That young guy is very talented.)

Camión which literally means “truck,” is a colloquial term for a bus.

Voy a tomar el camión a la escuela . (I’m going to take the bus to school.)

Chulear literally means “to pimp,” but in Mexico, it’s a verb used to describe showing off or flaunting something.

Deja de chulear tu nuevo auto . (Stop showing off your new car.)

Here’s a great explanation of chulear (in Spanish):

Chingar is a versatile verb with various meanings, but it can be used to express annoyance or bother.

No me chingues , estoy ocupado . (Don’t bother me; I’m busy.)

Estrenar is a verb used when someone wears or uses something for the first time.

Voy a estrenar mis zapatos nuevos hoy .

This expression is an informal way to express disgust or dislike, similar to saying “yuck” in English.

¡ Guacala ! Esta comida no tiene buen sabor . (Yuck! This food doesn’t taste good.)

Used to describe someone who is lazy, this term is derived from the word huevo, meaning “egg,” which is associated with laziness.

Mi amigo es muy huevón , siempre está descansando . (My friend is very lazy, he’s always resting.)

While the standard term for “car” is coche , jato is a slang word used in Mexico to refer to a car or automobile.

Vamos en mi jato al cine esta noche . (Let’s go to the movies in my car tonight.)

Used as a term of endearment, mamacita refers to an attractive or beautiful woman.

¡Ay, mamacita , estás muy guapa hoy! (Oh, beautiful, you look very pretty today!)

This slang term is used to refer to money, similar to saying “cash” in English.

Necesito un poco de pisto para el transporte . (I need some cash for transportation.)

An informal and colloquial way of asking “what’s up?” or “what’s going on?”

¿ Qué pex, cómo estás? (What’s up, how are you?)

Used to refer to a song or piece of music, rola is a common slang term in Mexican Spanish.

Esta rola es mi favorita. (This song is my favorite.)

An alternative and informal way of asking “what’s up?”

Sapbe , nos vemos en el centro . (What’s up, see you downtown.)

Literally meaning “brave,” this slang term simply means “good friend.”

Mi valedor siempre está allí para ayudarme . (My friend is always there to help me.)

Describes someone as a crazy or wild guy, often used in a lighthearted or affectionate manner.

Mi amigo es un vato loco , siempre hace cosas divertidas . (My friend is a crazy guy, always doing funny things.)

Wacha , which is taken from the English “watch,” is an informal and colloquial way of saying “look” or “watch.”

Wacha esa película, está buenísima . (Look at that movie, it’s really good.)

This expression is used to convey that a difficult or troublesome situation has arisen. It literally means “the clown has already killed us.”

Se nos olvidaron las entradas, ya nos cargó el payaso . (We forgot the tickets, we’re in trouble.)

An informal term used to refer to a friend or buddy, indicating camaraderie.

Ese cuate siempre me ayuda cuando lo necesito . (That buddy always helps me when I need it.)

Used to refer to someone’s face, especially when expressing a negative emotion. It’s just like the English “mug.”

No me gusta su jeta , siempre está enojado . (I don’t like his face, he’s always angry.)

This slang term is used to describe a strong hit or punch.

Le di un madrazo al balón y entró en la portería . (I gave the ball a strong hit and it went into the goal.)

This slang term, literally “cheek,” is used informally to refer to this part of the body.

Le dieron un golpe en la nalga . (They gave him a hit on the buttocks.)

Although “dark-skinned person” is a direct translation, ñero is a colloquial term used in some regions to describe someone with a dark complexion. Be careful not to offend with this one.

No importa si eres ñero o güero, todos somos iguales . (It doesn’t matter if you’re dark-skinned or fair-skinned, we are all equal.)

Pacheco is often used in Mexico to describe someone who is intoxicated or inebriated.

No puedo hablar con él cuando está pacheco . (I can’t talk to him when he’s drunk.)

Go deeper into pacheco here:

Literally meaning “pirate,” this term is often used in Mexican slang to describe counterfeit or knockoff items.

No compres ese reloj, es pirata . (Don’t buy that watch, it’s fake.)

This literally means “relax,” but in Mexican slang, it means a mess, or a chaotic or disorderly situation.

No quiero más relajo en casa . (I don’t want more mess in the house.)

This slang term for a belt is often used in casual or regional contexts.

Me apreté la riata para que no se me cayera el pantalón . (I tightened the belt so my pants wouldn’t fall.)

Literally meaning “envelopes,” this term means “I got it,” a casual way of expressing understanding or acknowledgment.

—¿Vamos al cine mañana? —¡ Sobres ! (Are we going to the movies tomorrow? – Okay, got it!)

While “covered” is the direct translation, tapado is a slang term used in some regions to describe someone who is arrogant or full of themselves.

No me gusta hablar con él, está muy tapado . (I don’t like talking to him, he’s very conceited.)

Instead of the standard camión , troca is commonly used in Mexico to refer to a pickup truck or a large vehicle.

Vamos a cargar la troca con las cosas para la mudanza . (Let’s load the truck with the things for the move.)

Zarape specifically refers to a colorful Mexican blanket or shawl often used for warmth or decoration.

Me envolví en el zarape porque hacía frío . (I wrapped myself in the blanket because it was cold.)

Check out this video to hear some of these Mexican slang words in context:

Here’s some good things to know about Mexican Spanish:

- In Mexican Spanish, the pronoun t ú is used for the second-person familiar form. Mexicans don’t use v os .

- The pronoun vosotros isn’t used in Mexican Spanish. Mexicans use ustedes even in informal settings.

- Mexican Spanish features more loanwords from English than other national dialects. You will hear a lot more English words in Mexican Spanish than other dialects.

This is a compact volume filled with definitions, example sentences, online links and lots of relevant information about Mexican Spanish.

There are more than 500 words and phrases included in this book.

“Mexislang” is the end result of a blog that was intended to teach readers about Mexican slang.

It offers insight into the history of slang expressions and tips for how to use each word or phrase.

The option to stay with Mexican families to immerse in the language is a great way to learn about culture—including slang!

But if you’re not up for traveling, courses are also available in online one-on-one or small group format.

Online classes focus on grammar and conversational skills, so you’re sure to pick up plenty of slang along the way.

Also, they have a fantastic blog that’s both informative and entertaining.

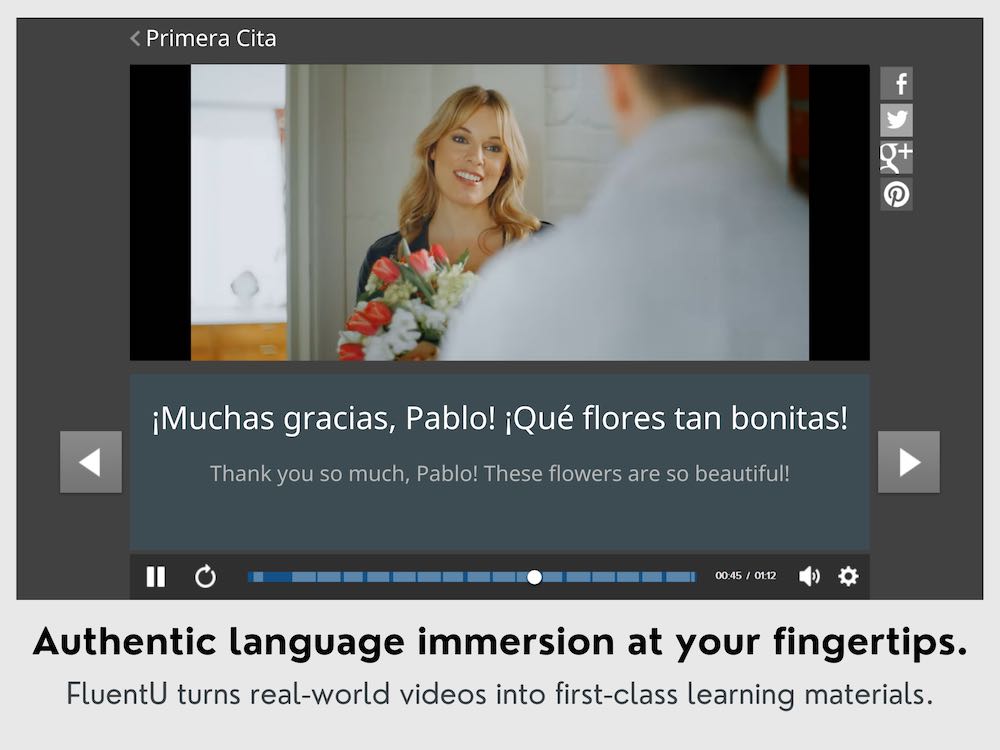

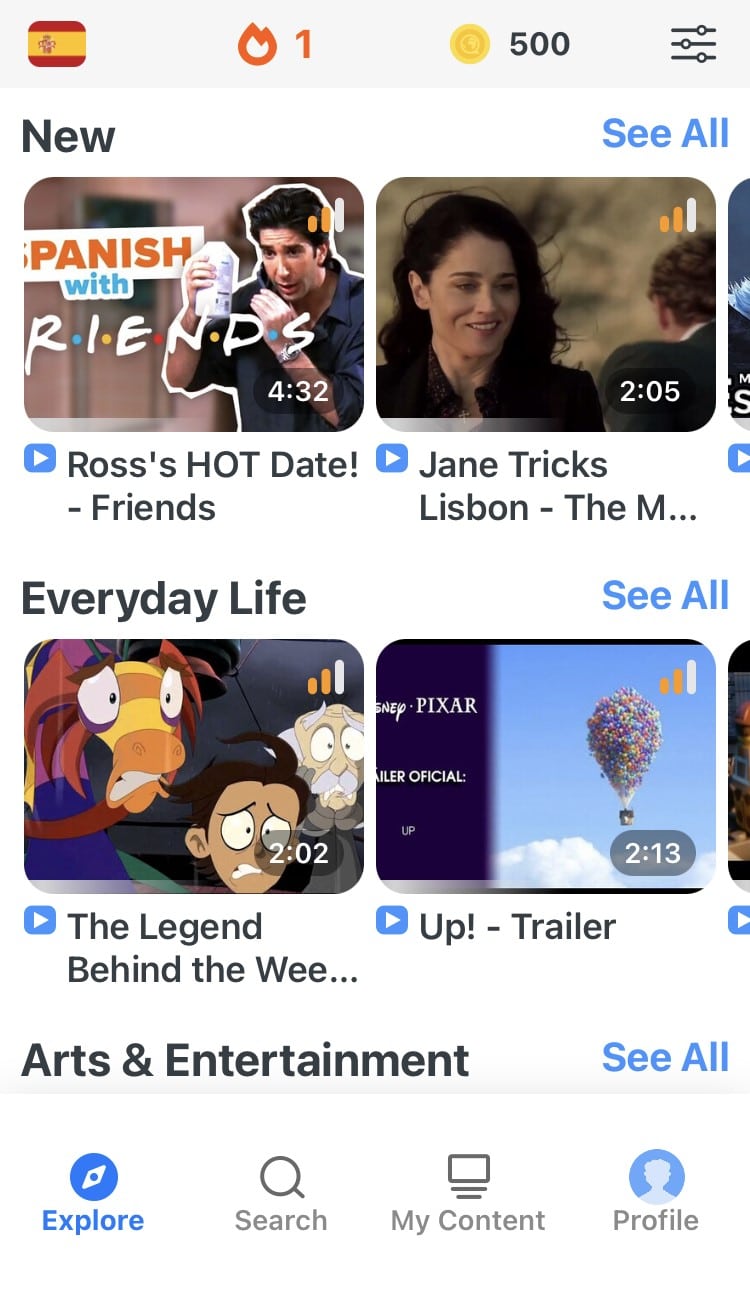

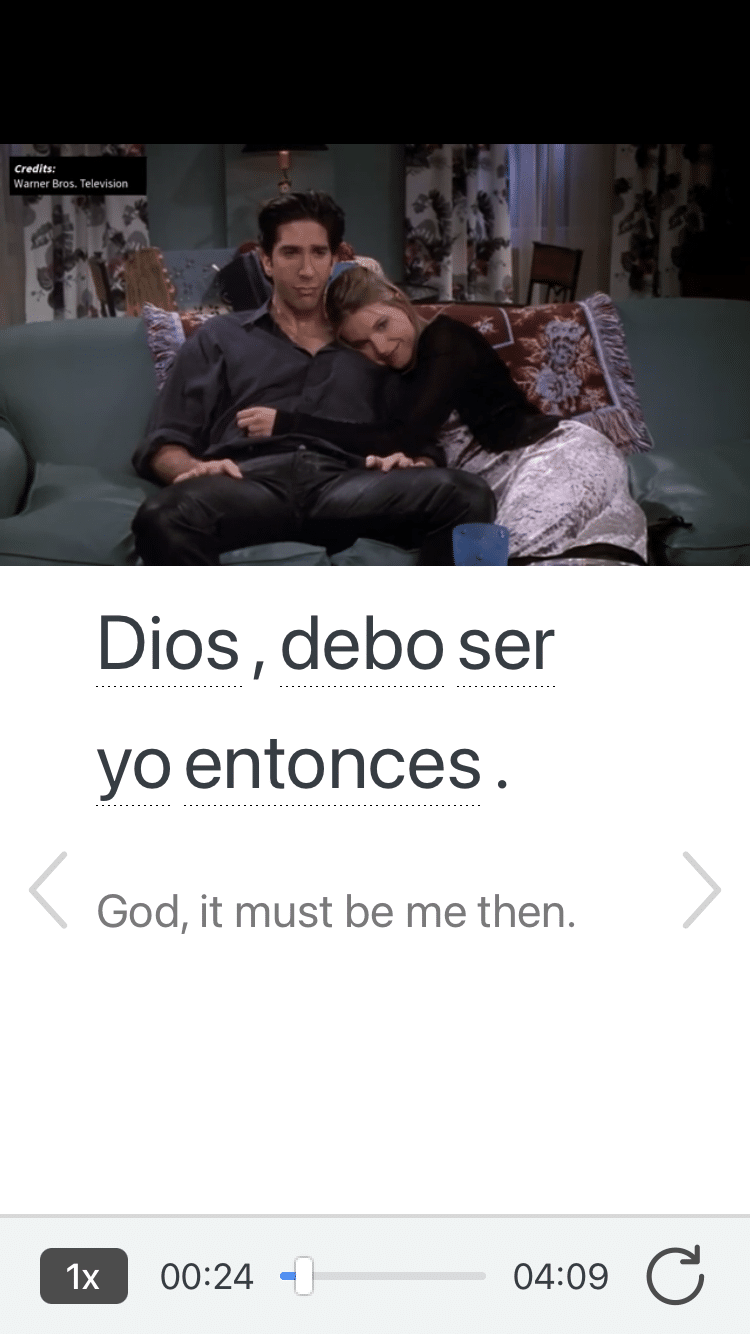

FluentU takes authentic videos—like music videos, movie trailers, news and inspiring talks—and turns them into personalized language learning lessons.

You can try FluentU for free for 2 weeks. Check out the website or download the iOS app or Android app.

P.S. Click here to take advantage of our current sale! (Expires at the end of this month.)

Try FluentU for FREE!

Like with English, Spanish is spoken differently depending on the country—in fact, you could argue that Spanish differs even more than English!

In order to understand and be understood in Mexican Spanish, it’s pretty essential that you learn some common Mexican slang.

If you’re not convinced, here are some reasons you might want to learn the lingo:

- To avoid awkward situations. Don’t count on every Spanish word being transferable from place to place—something that is perfectly polite in Spanish from Spain could be considered rude in Mexican Spanish.

- If you’re learning Spanish in the United States. Considering that the States has such a huge Mexican population, chances are that you’ll encounter lots of Mexican Spanish speakers!

- For travel in Mexico. For both safety reasons and to ensure smooth travels, it’s a good idea to brush up on your slang.

- To sound more fluent. Of course, learning slang words is one of the surest ways of making your Spanish sound more natural and fluent!

Slang is perfect for instantly turning “program” Spanish into street Spanish.

More importantly, they offer insight into some cultural nuances that language learners don’t always get to see.

Use slangy terms to power up conversations and go from basic to vivid in a heartbeat!

If you've made it this far that means you probably enjoy learning Spanish with engaging material and will then love FluentU .

Other sites use scripted content. FluentU uses a natural approach that helps you ease into the Spanish language and culture over time. You’ll learn Spanish as it’s actually spoken by real people.

FluentU has a wide variety of videos, as you can see here:

FluentU brings native videos within reach with interactive transcripts. You can tap on any word to look it up instantly. Every definition has examples that have been written to help you understand how the word is used. If you see an interesting word you don’t know, you can add it to a vocab list.

Review a complete interactive transcript under the Dialogue tab, and find words and phrases listed under Vocab .

Learn all the vocabulary in any video with FluentU’s robust learning engine. Swipe left or right to see more examples of the word you’re on.

The best part is that FluentU keeps track of the vocabulary that you’re learning, and gives you extra practice with difficult words. It'll even remind you when it’s time to review what you’ve learned. Every learner has a truly personalized experience, even if they’re learning with the same video.

Start using the FluentU website on your computer or tablet or, better yet, download the FluentU app from the iTunes or Google Play store. Click here to take advantage of our current sale! (Expires at the end of this month.)

Enter your e-mail address to get your free PDF!

We hate SPAM and promise to keep your email address safe

20 Mexican Slang Terms That Are Funny as Hell

:upscale()/2022/04/04/973/n/37139775/f9dac104624b6fa07fe6a2.04514903_.jpg)

Mexicans are known for our food, music, incredible beaches, rich traditions, and beautiful history. But when it comes to our culture, one of the things I love the most is our colorful colloquialisms. It doesn't take much time around Mexican-Americans to notice that there is a whole different set of terminology on top of the already beautiful and rich traditions that make up Mexican cultura . Like most Latin American countries, a lot of our terms and slang come from observing nature and Indigenous languages. And similar to Dominican and Puerto Rican slang , Mexicans love to play on words.

We say things like "buena onda," which means "good deep" but also describes someone easygoing and cool. We say things are "gacho" when they're bad and "chafa" when something is of bad quality. Not to mention, there are way too many terms that have to do with farts and sex organs. Here are 20 Mexican slang words that you may have heard and should definitely know.

Mexican Slang Word: Mames

What it means: "Mamar" means "to suck." "No mames" is generally a response, like "stop messing around," "stop messing with me," and "quit bullsh*tting."

In a sentence: "My friend told me she's dating J Lo. I told her, '¡No mames!'"

Mexican Slang Word: Pedo

What it means: Pedo translates to "what fart." It's a way of saying "no way," "what's up?" or "what's the problem?" You can also jazz it up by saying "puro pedo," or "pure farts." It means "you're full of sh*t" or "you're lying."

In a sentence: "Why are you giving me attitude? Que pedo?"

Mexican Slang Word: Cabron

What it means: Technically a cabron is a male goat. It can also mean "assh*le" and "dumb*ss." But when Mexicans say that a situation is a male goat, they typically mean that it's difficult or "that sucks."

In a sentence: "Comadre my sister is getting evicted."

"No pos wow, esta cabron."

Mexican Slang Word: Ahuevo

What it means: "Huevo" means "egg" or "testicle" depending on the context. You're basically saying "egg/balls" as a way of saying "hell yeah," "of course," or "for sure." It can also be used as a way of expressing you're being forced to do something.

In a sentence: "The medicine was gross but I had to take it. ¡Ahuevo!"

Mexican Slang Word: Órale

What It means: "Órale" is a way of expressing many emotions. It can be celebratory. It can indicate surprise or discomfort. It can be used as encouragement or as in "hurry up." It can also be used to agree with someone.

In a sentence: "¡Órale mija! I've been waiting for 15 minutes."

Mexican Slang Word: Pendejo/a

What it means: Stupid person.

In a sentence: "¡Eso es lo que te pasa por pendeja!"

Mexican Slang Word: Güey

What it means: "Güey" literally means "ox" or "slow and stupid." But it's basically Mexico's version of "dude."

In a sentence: "Ese güey me cae gordo."

Mexican Slang Word: Morra/o

What It means: "Morro/a" can mean "buddy" or "dude," or it may refer to a small child.

In a sentence: "Me gusta la camisa que trae esa morra."

Mexican Slang Word: Cruda/o

What it means: "Crudo/a" means "raw." It also means "hungover."

In a sentence: "I only had three drinks last night. ¡Me siento bien cruda!"

Mexican Slang Word: Aguas

What it means: It literally translates to "waters" but is often used to mean "watch out" or "be careful."

In a sentence: "¡Aguas! Don't fall down."

Mexican Slang Word: Chiflado/a

What it means: "Chiflar" means "to whistle." A chiflado is someone who is always calling attention to themselves by showing off, bragging, or being conceited.

In a sentence: "No quiero salir con Rudy, es bien chiflado el güey."

Mexican Slang Word: Fresa

What it means: Strawberry, but also a rich, spoiled girl/child.

In a sentence: "¿Qué quiere la niña fresa?"

Mexican Slang Word: Neta

What it means: "Seriously," "real talk," or "the truth is."

In a sentence: "La neta, I don't like exercising. Let's go eat!"

Mexican Slang Word: Padre

What it means: It means father but also means cool.

In a sentence: "Gas esta carsimo, que padre que vivo cerca del centro commercial."

Mexican Slang Word: Chorro

What it means: "Chorro" refers to a jet of water. It can mean "a lot," "a ton," or "a bunch."

In a sentence: "Ese morro me gusta un chorro."

Mexican Slang Word: Pinche

What it means: It can mean "damned," "sh*tty," or "f*cking."

In a sentence: "¡No encuentro mis pinches llaves!"

Mexican Slang Word: Chula/o

What it means: Cute, pretty, or attractive.

In a sentence: "Te ves bien chula."

Mexican Slang Word: Chamba

What it means: Job or work.

In a sentence: "Ya me voy a poner a chambear."

Mexican Slang Word: Gacho

What it means: "Gacho" can mean "awful," "bad," "ugly," or "mean," depending on the context.

In a sentence: "¡No seas gacho!"

Mexican Slang Word: Me Vale Verga

What it means: "Verga" refers to the male genitalia. "Me vale" means "it's worth to me." "It's worth d*ck" is a way of saying "I don't care" or "I don't give a damn."

In a sentence: "Me vale verga si no quieres salir. ¡Nos llama la calle!"

- Food & Drink

- Real Estate

- Mexico Living

Neta no vas a leer este artículo? La neta te conviene. Are you really not going to read this article? Honestly, you better!

Neta no. Neta sí. Es neta. Dime la neta.

Neta is one of the most common slang words in Mexico. Its origin traces back to the Spanish word “neto,” meaning “net” or “clear.” Over time, “neto” evolved into “neta,” and it was adopted as a fundamental part of Mexican Spanish. Today, the word has different meanings, including truth, honesty, authenticity, coolness and sincerity. It serves as a linguistic tool for expressing agreement, affirmation, or emphasis, depending on the context.

–”¿Es cierto que van a cerrar la tienda?” (Is it true that the store is closing?)

–”Sí, es neta. La dueña ya lo confirmó.” (Yes, it’s true. The owner already confirmed it.)

–”¿Confías en él?” (Do you trust him?)

–”¡Sí, ese wey es súper neta.” (Yeah, that dude is super legit.)

View this post on Instagram A post shared by Mexico News Daily (@mexiconewsdaily)

Example 3:

–¿Te cae bien? (Do you like her?)

–¡Sí, ella es la neta! (Yes, she is super cool!)

In these examples, “neta” is used to affirm the truthfulness of a statement or to emphasize the authenticity, honesty of a person. It adds a layer of sincerity and certainty to the conversation, making it a powerful tool for effective communication in Mexican Spanish.

Example 4:

–Supiste que Karla ya no va a ir al viaje? (Did you know that Karla is ditching the trip?)

¿Es neta?, ¿por? (Are you serious? why?)

–La neta ni idea (I really I don’t know)

Whether used to express agreement, confirm information, or convey sincerity, when you hear the word “neta,” know that the truth is being spoken in the most authentic way possible.

Paulina Gerez is a translator-interpreter, content creator, and founder of Crack The Code, a series of online courses focused on languages. Through her social media, she helps people see learning a language from another perspective through her fun experiences. Instagram: paulinagerezm / Tiktok: paugerez3 / YT: paulina gerez

Breeze through your virtual meetings with these Spanish phrases

MND Where to Live in Mexico 2024 Guide: Pacific Trio

When my husband and I decided to retire, we devised a plan. We wanted to rent out our home in California and visit the UNESCO World Heritage city of Guanajuato.

We planned on staying in the city for just six months, but 20 years later, we now live in Mexico as expats part time.

Even though my husband and I have been living in Mexico part time for two decades years, I'm still surprised at how different the culture is compared to the American culture I have lived in all my life.

The biggest cultural differences are always in the way we communicate.

People in Mexico tend to be more indirect

I found Americans to be very direct. In Mexico, however, if I speak bluntly and to the point, it can be misinterpreted as rude and offensive since it clashes with a more diplomatic communication style. The priority, as in other Latin countries , is to preserve harmony.

To avoid conflict or confrontation, the Mexicans I met rarely say "no" directly but rather speak in a roundabout way to convey their message. If asked a "yes" or "no" question, they might meander around inconclusively before reaching a vague answer like: "Let me think about it."

For example, in my yoga class , one member coordinates a monthly breakfast. A few weeks ago, I chuckled when I read the message she wrote to the group. She took 160 words to basically say, "We need to decide where to have breakfast this month."

It's different from my minimalist English style .

For some Mexicans, lateness is acceptable

As an American, I have noticed some Mexicans have a casual attitude toward time, which can be frustrating.

Related stories

Recently, for example, I had an appointment with the director of a nonprofit to discuss updating the agency's newsletter. Before arriving at her office , I was already flustered because her directions had been ambiguous — at best — and in Guanajuato's nonlinear streets, house numbers aren't consecutive.

When I finally arrived, her staff told me she was out of the office and would be back ahorita, which means "soonish."

Instead of recognizing that she was late only by my definition, not hers, I started to feel unimportant and ignored. When she showed up half an hour later, I felt less confident in my Spanish. While I'm fluent in the language, my conversational ease still fluctuates depending on different circumstances, and that day, it wasn't as strong as usual. I left feeling very deflated.

My takeaway is not to take lateness personally in Mexico.

Cheeky jokes are the norm

The Mexicans I met like to tease each other, give friends cheesy nicknames, and make jokes about things that in the US would be inappropriate.

For example, at a concert I attended, one of the musicians referred to another as gordito, meaning plump. I can't imagine a performer joking about someone's weight in the US — and never in front of an audience.

Personal space and alone time isn't important to most Mexican people

In Guanajuato — the city in central Mexico where we live — there are many festivities with crowds, and as a gringa, I still find all the jostling and physical contact with strangers unsettling at times.

A few years ago, our 25-year-old Spanish tutor told my British husband Barry that after her sister married, she would have a room to herself for the first time. He could think of nothing better.

"Isn't that wonderful?" he said.

"Oh, no," she said. "I'll be lonely."

Their respective reactions reflected very different cultural values .

Most Mexicans I meet appreciate simple courtesies

When we first bought our home, I didn't realize how important courtesy is in Mexico. Thankfully, I have since softened and, in fact, have grown very fond of the gentle niceties many Mexicans use.

If, for example, I'm asking directions or entering a shop, I know to first say Buenos días or Buenos tardes . Similarly, I always greet the driver and my fellow passengers when getting on a bus. When leaving a restaurant, I'm sure to say, as many Mexicans do, Buen provecho (meaning bon appetit ) to the remaining diners.

Some courtesies make me laugh. If a person walks down the street in Mexico and sneezes, complete strangers from a block away will exclaim, Salud!, which means "good health" but also "cheers."

After almost 20 years of living in Guanajuato, I'm still discovering quirky-to-me aspects of Mexican communication. The unexpected twists in the way Mexicans express themselves occasionally confuse me, but they are mostly a source of laughter and pleasure.

Watch: How firearms smuggling actually works, according to a weapons specialist

- Main content

24 Spanish Slang Terms Commonly Used By Native Speakers

- Read time 13 mins

Sounding like a fluent Spanish speaker requires a mastery of Spanish verbs , a wide Spanish vocabulary and, believe it or not, a little bit of slang!

Although they don’t always teach you the full range of colloquial terms in Spanish classes and schools, slang words and phrases are a staple of social interactions and are used abundantly in conversations between friends.

You might therefore be feeling a bit like an outsider among native speakers if you’re just getting used to Spanish slang, but ¡no te preocupes!

With this list of commonly used Spanish slang words and phrases you’ll soon be able to catch some of the quirkier expressions, slang phrases and colloquialisms that are used by the natives.

Why is Spanish slang important and when should it be used?

Spanish slang is important for various reasons.

Not only does using certain phrases help you sound like a native Spanish speaker, you will be able to fully immerse yourself in informal dialogues and understand the more subtle, nuanced meanings of conversations between friends.

Because, just like Spanish greetings , context is key and dictates how you should speak with others, you should always be aware of who you are speaking to and who else might be present when using Spanish slang.

After all, you wouldn’t address your boss or in-laws with the word ‘mate’, would you? 😊

A good friend might use a range of slang terms when they speak to you because they are familiar with you. You’re their tío / tía (in this context, good friend/dude), and the context is informal. They know that you’ll completely understand their intended meaning because they’ve known you for a very long time.

Native speakers reserve their Spanish slang for the right conversations and the right people, and that’s exactly what you should do as well.

Now you know why Spanish slang is important, here is our list of Spanish slang words, phrases and colloquial expressions that you’ll frequently hear from native Spanish speakers.

Take a look — which ones have you heard recently?

Spanish slang phrases that have negative connotations (and insults)

Sometimes you’ll need a slang word that conveys a negative meaning, or to express how annoyed something has made you feel. These are some of the common colloquial Spanish words and phrases that have a negative connotation behind them.

They might help you vent your frustration, but always consider the context in which you use them!

Ser un pijo/ser una pija (to be a brat/spoiled)

This slang phrase is used by Spaniards when referring to a ‘posh’, ‘snobby’ person who might have inherited a lot of money and gained their wealth without working very hard. When using this slang term, be careful!

In some Spanish speaking countries un pijo can mean ‘penis’. 🤣

Usage example:

Que no seas una pija. No te comprare nada mas.

Ser cutre (to be stingy)

The Spanish slang term cutre refers to someone who supposedly never has any money.

They are ‘stingy’ when it comes to covering the tab, so you can bet that a person who is cutre will never offer to pay for a round of drinks.

Nunca me ha regalado nada en toda mi vida. Es que, es tan cutre.

Joder (shit, f**k)

This slang term is also a palabrota or swear word , which has a range of meanings. Commonly exclaimed when someone wants to express their annoyance or disapproval, joder is a word that you’ll frequently hear in Spanish movies.

If your friend says it, you’ll know they’re irritated, upset or angry.

¡Joder! El Barca ha perdido el partido. ¿Pero, como es posible?

Es una cotilla (he’s/she’s a busybody, a snooper)

This Spanish slang phrase is an epithet used to describe someone who gossips a lot or knows too much about other people’s lives.

Chances are, if you’re in Spain, you’ll probably have a vecino (neighbour), who is a typical cotilla .

Mi vecina es una cotilla. Está siempre escuchando los escándalos de la gente.

Caray/caramba (damn)

We use the Spanish slang term caray , which is short for caramba , when we’re shocked, annoyed or appalled by something unjust that might have happened.

If someone is constantly nagging or nitpicking, and you feel frustrated by it, you might use this term to express how annoyed you are.

¡Cállate mujer, caray! Que no seas una cotilla. Siempre hablas demasiado.

Estar en la luna (absent-minded)

Though this Spanish slang term literally means ‘to be at the moon’, we use it to describe someone who is figuratively a million miles away or ‘absent-minded’.

If you’re en la luna , it means you are not focused or concentrating at that moment.

Pero, estáis en la luna hoy. No me estáis escuchando.

Tirar la toalla (concede/surrender)

This Spanish slang phrase might bring to mind the English expression ‘throw in the towel’, as the Spanish noun toalla translates as ‘towel’.

As with the English phrase, it means that you plan to abandon a difficult task or to admit you’ve been beaten by an impossible challenge.

Es la hora de tirar la toalla. No me puedes vencer ahora.

Me cae mal/me cae gordo (he/she annoys me)

We use this Spanish phrase to describe someone who has given you a bad impression of themselves — or to refer to someone who annoys you.

The phrase me cae gordo similarly conveys this meaning, and can also refer to the bad gut feeling or intuition a person gave you.

Este tío me cae mal. Es muy presumido y arrogante. No sabe cuando callarse.

Spanish slang phrases that have positive connotations

There are so many occasions where you’ll need to express your respect for someone, to address your group of friends with a positive or inclusive phrase, or use a term that shows how much you admire them.

Check out these Spanish slang terms that connote positivity or admiration.

Ser mono/ser mona/eres tan mono (to be adorable, cute)

Don’t get confused by this Spanish slang phrase — while mono translates as ‘monkey’, when used with the verb ser its meaning changes.

We use the colloquial adjective ser mono / mona to refer to someone who is cute or adorable.

Mira, ¡eres tan mono y precioso que no tengo palabras!

Molar/cómo mola (cool)

This common Spanish word is heard everywhere in Spain! Used in a similar way to the phrase que guay , something described with the word molar is ‘awesome’ or ‘cool’.

Este coche es muy grande. Tiene mucho espacio. ¡Cómo mola!

Guay (cool)

Guay is another Spanish slang term for ‘cool’. With young people using it frequently, you’ll hear it everywhere in Spain.

Like the word mola , it’s a common word that can be used to compliment a situation or express admiration for someone on account of how amazing they are.

Que guay, tío. Me alegro que estéis mas felices que antes.

Tío/tía (dude, chico, chica)

In Spain, you’ll hear young people referring to their friends as tío / tía all the time.

A direct translation would give you the word ‘uncle’ or ‘aunty’, but among friends it means ‘dude’ or ‘mate’.

¡Has comprado una casa! Pues, que guay, ¡tío!

Chaval/chavala/chavales (guys)

There are many meanings to this Spanish slang term. The phrase ser un chaval refers to someone who is young in terms of their attitude.

It has connotations of being inexperienced or naïve, but it’s also a colloquial term used between friends meaning ‘dude’ or ‘guys’.

¿Que pasa chavales? ¿Ya estáis cenando? Llegare dentro de cinco minutos.

Qué chulo/chula (how cool, how stylish)

If something is described as chulo / chula , we mean that object is cool, stylish or amazing.

It’s a compliment, so you can use this slang phrase to express how much you like your friend’s new iPhone or their new car.

¡Tienes botas muy chulas! ¡Que envidia!

Hincar los codos/voy a hincar los codos (to study a lot)

Have you pulled an all-nighter before an all-important exam? The Spanish slang phrase you’ll need to convey just that is hincar los codos .

It means ‘study hard’ and might bring to mind the English expressions ‘put some elbow grease into it’ or ‘roll your sleeves up’ because your codos are your elbows in English.

Quiere aprobar el examen de ciencias. Tiene que hincar los codos.

Es la leche (it’s awesome/amazing)

It’s easy to get confused by the many Spanish terms that feature the word leche or milk. A person might be in a bad mood, in which case you might say está de mala leche. But in this context, the slang term es la leche refers to how amazing something is.

That really cool book you finished reading last week — if it was fantastic and resonated with you, you might describe it as la leche .

Hombre, esta peli es la leche. A mi me gustó un montón.

Spanish slang terms for amazement, shock or disgust

If something has stunned you silent and you just don’t know how to express your feelings, these Spanish slang words might describe the situation perfectly.

Take a look at these colloquial expressions that are frequently used by native Spanish speakers when there simply are no ideal words.

Hostia/la hostia (wow, no way!)

Though the word hostia is literally the Spanish term for the wafer given to you during communion, it also means ‘my God!’ and is commonly used to express shock or complete surprise caused by something or someone.

¡Hostia! Que barbaridad, los politcos siempre son corruptos.

Ostras (wow, oh my!)

If you’re looking for a way to express your shock and surprise in a ‘non-blasphemous’ way, the Spanish slang term ostras is one option.

It is the same as exclaiming hostia , and conveys the same meaning, but is an expression typically used to avoid saying ‘oh my God’.

¡Ostras! Tienes mucho dinero. ¿Que vas a hacer con eso?

Flipar/te vas a flipar (freak out, go nuts)

Flipar is a Spanish slang expression that conveys shock or astonishment. It means ‘go crazy’ and can be used in a range of contexts. You might have discovered that someone is having an affair.

Or perhaps someone you know has suddenly inherited a fortune…

The phrase you’re going to need if you’re going to tell someone about that shocking news is te vas a flipar .

You’re going to freak out… I’m going to marry her!

Estar como una cabra (he’s/she’s nuts)

Though this slang term literally translates to English as ‘to be like a goat’, in Spain we use this phrase to refer to or describe someone who is totally crazy or behaving in a peculiar, silly way!

¿Pero, está borracho? ¡Está como una cabra!

Other frequently used Spanish slang terms

The world of Spanish slang is vast and varied. There are so many colloquial terms that Spaniards use on a daily basis.

We’ve only scratched the surface! Here are a few more that might be of interest to you.

Me piro/pirarse (I’m leaving)

The full phrase sometimes used by Spanish speakers is me piro vampiro . It’s a funny slang term similar to ‘see you later alligator’.

The verb pirarse means ‘to leave’, so if you want to decline an invitation from your friends to go for more drinks later in the evening you can say lo siento, me piro.

No tengo ganas de ir a la fiesta. Lo siento, me piro.

Tomarse el pelo (pulling someone’s leg/having you on)

The literal translation of tomarse el pelo would be ‘pulling my hair’, but this slang term is used when someone is teasing you or making fun of you.

Sin duda, hombre, esa mujer te estaba tomando el pelo. No puede ser que ella tenga 59 años.

Es un lío/liar (it’s a mess/screwed up)

We use the slang term es un lío when we’ve made a mistake or done something wrong.

One example of this could be if someone has an affair, which we would describe by using the verb liarse . If something is un lío we mean it’s a mess.

Es todo un lio. Esta vez, no creo que entienda.

Duro/no tengo un duro (penniless, broke)

Duro is a Spanish slang term that means ‘money’. If you don’t have any, you can say no tengo un duro.

Lo siento, no te puedo comprar la bici. No tengo un duro.

How can you sound like a native when using Spanish slang?

The key to sounding like a native — and to avoid using the wrong Spanish slang term — is not only to consult lists and examples, but to listen to native speakers and actually hear the colloquial terms used in context.

When in doubt, consider how the person speaking to you addresses you and analyse the way they speak.

By listening and taking note of the phrases they use, you’ll soon be able to use them yourself.

Every person is unique, though. You might not use the exact same Spanish slang terms as your friends on every occasion. But having a good knowledge of these common terms is important as it will enhance your understanding.

There are also some excellent Spanish courses and apps that cover slang terms in greater detail.

Did I miss any Spanish slang terms?

Comment below!

🎓 Cite article

Learning Spanish ?

Spanish Resources:

Let me help you learn spanish join the guild:.

Donovan Nagel - B. Th, MA AppLing

Bruna Misuno Child

Really nice article, thank you! I speak more Latin American Spanish so I didn’t know some of these words. Now I’m going to use both!

REPLY TO BRUNA MISUNO CHILD

- Affiliate Disclaimer

- Privacy Policy

- About The Mezzofanti Guild

- About Donovan Nagel

- Essential Language Tools

- Language Calculator

SOCIAL MEDIA

Current mission.

Let Me Help You Learn Spanish

- Get my exclusive Spanish content delivered straight to your inbox.

- Learn about the best Spanish language resources that I've personally test-driven.

- Get insider tips for learning Spanish.

Don’t fill this out if you're human:

No spam. Ever.

As new real estate agent rule goes into effect, will buyers and sellers see impact?

New rules for the residential real estate market mean that starting Saturday, anyone in the market to buy or sell a home will encounter unfamiliar processes, and possibly a bit of confusion.

The “practice changes” stem from a 2023 legal decision over the way real estate agents were compensated.

Traditionally, when a home was sold, a commission of roughly 5% to 6% was paid by the seller and divided between the agents for the buyer and the seller. That structure helped keep commissions higher than they would otherwise be, the lawsuit alleged. It also meant a seller had to pay the agent representing the other side of the deal, a practice many observers thought was inappropriate.

“So much of the industry doesn’t make sense from a common sense point of view,” said Stephen Brobeck, a senior fellow with the Consumer Federation of America, who’s been advocating for realtor commission changes for decades. “The key argument was it’s just not fair for sellers to pay both the listing agent and the buyer’s agent.”

Now, a seller will need to decide whether, and how much, to pay a buyer’s broker. Whatever the decision, that information can no longer be included in what’s known as the “multiple listing service” or MLS, the official real estate data service used by local realtor associations.

Whatever the seller decides about compensation may, however, be communicated personally by phone or text, or advertised by social media, a sign on the lawn, or other informal means.

Buyers, meanwhile, will be required to sign an agreement with their own broker before starting to view homes. The buyer and the agent must agree, and put in writing, how much the agent can expect to receive from the buyer.

There's some latitude on what exactly that means. A recent explanation of the rules from the National Association of Realtors says it must be "objective (e.g., $0, X flat fee, X percent, X hourly rate) – and not open-ended (e.g., cannot be 'buyer broker compensation shall be whatever the amount the seller is offering to the buyer')."

“Any time we have the opportunity to have a conversation with the consumer about the value that we bring to the transaction, the services that we’ll be able to give to them in what is likely one of the largest financial transactions of their lives, and that we expect to get paid for it which is entirely negotiable, that’s a good thing,” said National Association of Realtors President Kevin Sears.

The group is a powerful Washington lobby with more than 1.5 million member agents – about 85% of the real estate agents in the country.

“The more the consumer is educated and empowered, the more conversations we have with consumers, the better off everyone will be,” Sears said.

Many elements of the new practices are familiar to many real estate agents, buyers, and sellers. Many states have long required buyers to sign a broker agreement before starting the process. The rise of alternative brokerage models, such as Redfin, means many homeowners are aware they have options beyond the typical method of paying 3% to a listing agent and 3% to a buyer’s agent.

But questions about what the changes will mean in practice are stymying agents across the country. What happens if a buyer has the money to compensate her broker up to a certain amount, but falls in love with a home that would cost more than the commission would work out to? On the flip side, what happens if it turns out that the seller of a particular home is also willing to compensate a buyer’s broker?

Many real estate agents say a process that was meant to bring transparency is just creating more confusion.

“Now a buyer’s agent has to reach out to every listing they’re going to show to figure out what the commission is,” said Aaron Farmer, owner of Texas Discount Realty in Austin.

In Austin, where a booming pandemic market turned sharply , leading to unsold inventory piling up, Farmer thinks it’s only natural that sellers will want to compensate buyer’s brokers, as a deal sweetener. That may not be the case everywhere, however, and Farmer also worries egos may get in the way of smart business decisions in some transactions.

Andi DeFelice, owner of Savannah, Georgia-based Exclusive Buyer’s Realty, thinks first-time buyers stand to lose the most from the rule changes. Many who are already strapped for cash may have trouble also coming up with the money for the commission, forcing them to negotiate on their own, she thinks.

"Don’t force our clients into a situation where they have no representation in the biggest transaction in their lives,” DeFelice said. “If you’ve never done it before, it’s not easy. There are so many steps to buying a house. Do you know a good termite inspector, a good insurance agent, a good lender? There are so many aspects to the transaction.”

DeFelice says she’s confident the industry will move past what she calls the “hiccup” of the Saturday deadline and adapt relatively quickly, but others expect bigger changes ahead.

“For consumers, things are not going to change much in the immediate future,” Brobeck told USA TODAY. "But it’s like a dam that’s springing a leak. I’m fairly confident that within five years the industry will look quite different.”

Farmer, of Texas Discount Realty, agreed.

"I'm already seeing a lot of people saying, 'I’m going to get out of the industry, I don’t want to deal with the changes,'" he said. "The way I’ve always looked at it is if there’s fewer agents, it helps the industry. You could drop commission rates that way and do more volume."

Andrea Riquier covers the housing market.

Watch CBS News

Fact checking DNC 2024 Day One speeches from Biden, Hillary Clinton and other Democrats

By Laura Doan , Amelia Donhauser

Updated on: August 20, 2024 / 9:54 AM EDT / CBS News

CBS News is fact checking some of the statements made by speakers during the 2024 Democratic National Convention, which is taking place in Chicago from Monday, Aug. 19 through Thursday, Aug. 22.

The convention began with unity as the theme, and the featured speakers Monday were President Biden and 2016 Democratic presidential nominee Hillary Clinton, as well as a host of others.

Some of the comments that CBS News' Confirmed team fact checked involved Democrats' comments about GOP nominee Donald Trump's record as president, as well as the Biden administration's record.

CBS News is covering the DNC live.

Fact check on Wisconsin Lt. Gov. Sara Rodriguez's claim that Trump promises "to terminate the Affordable Care Act": Misleading

Details: In 2016, former President Donald Trump promised to repeal and replace the nation's health care law, the Affordable Care Act (ACA), if elected. During his presidency, he backed attempts by Republicans to repeal parts of the law while carrying over other parts.

In this election cycle, Trump has continued to criticize the law but has said he doesn't support terminating all of its policies outright. In November, Trump said he intends to "replace" the Affordable Care Act with another package of health reforms.

In March, he said that he was "not running to terminate the ACA" but instead to make it better and cheaper.

By Alexander Tin, Amelia Donhauser

Fact check on California Rep. Robert Garcia's claim that Trump "told us to inject bleach into our bodies": False

Details: In an April 2020 White House news briefing with members of the government's coronavirus task force, Trump, who was then president, speculated about combating COVID-19 by injecting disinfectant into the body. He suggested doctors should study this possibility, but he did not tell people to inject bleach into their bodies.

"I see the disinfectant, where it knocks it out in a minute, one minute," Trump said. "And is there a way we can do something like that — by injection inside or almost a cleaning — because you see it gets in the lungs and it does a tremendous number on the lungs, so it'd be interesting to check that, so that you're going to have to use medical doctors with, but it sounds interesting to me."

The Trump White House later offered differing excuses for the remark. It first said Trump's comments were taken out of context. A day later, Trump told reporters that he was being sarcastic when he raised the possibility of injecting disinfectants.

"I was asking a question sarcastically to reporters like you just to see what would happen," he said.

By Amelia Donhauser

Fact check on Senate Majority Whip Dick Durbin's claim that the U.S. economy added 16 million jobs during the Biden administration: True, but needs context

Details: Under President Biden, the U.S. economy has added more than 15.8 million jobs, according to July data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics .

However, it's important to note that the number includes roughly 9 million jobs that were lost during the COVID-19 pandemic. The U.S. economy under Mr. Biden has seen an increase of approximately 6.4 million jobs above February 2020 levels, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics .

By comparison, 6.7 million jobs were created in the first three years of former President Donald Trump's term between January 2017 and February 2020, before the pandemic left Trump with record job losses.

By Laura Doan

Fact checking Kentucky Gov. Andy Beshear's claim that Vance thinks women should stay in violent marriages, and pregnancies from rape are "inconvenient": Misleading

Beshear: "JD Vance says women should stay in violent marriages and that pregnancies resulting from rape are simply inconvenient."

Details: Before he was a Republican Ohio senator, JD Vance spoke of being raised by his grandparents and their relationship at an event in 2021. He contrasted their commitment to each other during an "incredibly chaotic" marriage with modern divorce rates.

"I think the sexual revolution pulled on the American populace, which is the idea that, like, 'Well, okay, these marriages were fundamentally, you know, they were maybe even violent, but certainly they were unhappy," he said. "And so getting rid of them and making it easier for people to shift spouses like they change their underwear, that's going to make people happier in the long term."

"And maybe it worked out for the moms and dads, though I'm skeptical," Vance added. "But it really didn't work out for the kids of those marriages."

Vance has repeatedly said these remarks were taken out of context. In a statement to VICE News in 2022 he said, "In my life, I have seen siblings, wives, daughters, and myself abused by men. It's disgusting for you to argue that I was defending those men."

In 2021, Vance was asked if anti-abortion laws should include exceptions for rape or incest. He replied: "It's not whether a woman should be forced to bring a child to term, it's whether a child should be allowed to live, even though the circumstances of that child's birth are somehow inconvenient or a problem to the society. The question really, to me, is about the baby," he continued. "We want women to have opportunities, we want women to have choices, but above all, we want women— and young boys in the womb — to have the right to life."

In July, Vance told Fox News, "The Democrats have completely twisted my words. What I did say is that we sometimes in this society see babies as inconveniences, and I absolutely want us to change that."

By Amelia Donhauser

Fact checking Biden's claim there are fewer border crossings today than when Trump left office: True, needs context

President Biden : "There are fewer border crossings today than when Donald Trump left office."

Details: In July, migrant apprehensions along the U.S. southern border dropped to 56,408 , the lowest level since September 2020, according to U.S. Customs and Border Protection data. When Trump left office in January 2021, the number of apprehensions was around 75,000.

The decline in illegal border crossings had been dropping steadily since the spring and accelerated after Mr. Biden issued a proclamation on June 4 banning most migrants from seeking asylum at the U.S.-Mexico border. Officials have also said scorching summer temperatures and Mexico's efforts to stop migrants have contributed to the drop.

Yearly apprehensions at the U.S. southern border also reached record highs during Mr. Biden's term, according to the data . In fiscal year 2023, the number reached 2.2 million. The number of yearly apprehensions under Trump peaked at around 852,000 in the fiscal year 2019.

By Camilo Montoya-Galvez, Laura Doan

Alexander Tin contributed to this report.

- Hillary Clinton

- Kamala Harris

Laura Doan is a fact checker for CBS News Confirmed. She covers misinformation, AI and social media.

More from CBS News

Littleton PD investigates allegations of assault among LHS football team

Coloradan on Harris's team continuing legacy of activist family

Conductors have minor injuries in 2-train crash in Boulder

Hickenlooper says 2026 re-election bid will be his last campaign for Senate

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

2024 Election

The dnc roll call featured a musical salute to each state. here's what your state chose.

DJ Cassidy performs during the second day of the Democratic National Convention at the United Center on Tuesday in Chicago. Andrew Harnik/Getty Images hide caption

The NPR Network will be reporting live from Chicago throughout the week bringing you the latest on the Democratic National Convention .

DJ Cassidy and the Democrats played special tracks for each state and territory during Tuesday night's roll call.

WATCH: The full Democratic National Convention celebratory roll call

But what song — or songs, in some cases — repped your state? We found them all so you don't have to. Better yet, we offer some reasons behind the choices.

Alabama : Sweet Home Alabama - Lynyrd Skynyrd

While Lynyrd Skynyrd's ode to Alabama might seem like an obvious choice, the band was formed in Jacksonville, Fla.

Alaska : Feel It Still - Portugal. The Man

The rock band is from Wasilla, Alaska, where two of its members met in high school and began playing music together.

American Samoa : Edge of Glory - Lady Gaga

The song choice is a tongue-in-cheek nod to the territory's position as the southernmost territory in the United States.

Arizona : Edge of Seventeen - Stevie Nicks

Singer-songwriter Stevie Nicks, known for both her solo career and her work in the band Fleetwood Mac, is from Phoenix.

Arkansas : Don't Stop - Fleetwood Mac

Speaking of Nicks, her band's track "Don't Stop" became the official song of Bill Clinton's 1992 presidential campaign, with the band even uniting to perform at the former president's first inaugural ball. Clinton is famously from Hope, Arkansas, and served as the state's governor from 1979 to 1981 and again from 1983 to 1992.

Then-President Clinton shakes hands with Michael Jackson as Stevie Nicks sings during inauguration festivities in Landover, Md. AFP/via Getty Images hide caption

California : The Next Episode - Dr. Dre featuring Snoop Dogg, California Love - Tupac Shakur, featuring Dr. Dre, Alright - Kendrick Lamar, Not Like Us - Kendrick Lamar

Nearly all of the above artists are legendary California musicians, with Dr. Dre and Kendrick Lamar born in Compton, and Snoop Dogg born in Long Beach. Only Tupac stands out among the native Californians, having been born in New York City.

Colorado : September - Earth, Wind & Fire

Philip James Bailey, one of two lead singers of Earth, Wind & Fire was born in Denver. What's more, he turned to Denver East High School friends Larry Dunn and Andrew Woolfolk to shore up the band after some original members left, according to the Colorado Music Hall of Fame .

Connecticut : Signed, Sealed, Delivered (I'm Yours) - Stevie Wonder

It’s “kind of a perfect campaign song,” as Chris Willman, the chief music critic at Variety , notes on Morning Edition . Wonder is from Michigan, but that didn’t stop Barack Obama from making “Signed, Sealed, Delivered” a hallmark of his two presidential campaigns.

Delaware : Higher Love - Kygo & Whitney Houston

Higher Love has been a staple of President Biden's campaign, with the track playing at the end of his 2020 acceptance speech.

President Biden delivers remarks after his election on Nov. 7, 2020. JIim Watson/AFP via Getty Images hide caption

Democrats abroad: Love Train - The O'Jays

Washington, D.C. : Let Me Clear My Throat - DJ Kool

The legendary rapper was born and raised in our nation's capital.

Florida : I Won't Back Down - Tom Petty

Tom Petty was born in Gainesville, Fla. His “American Girl” was also used by Hillary Clinton’s campaign.

Georgia : Turn Down For What - DJ Snake and Lil Jon

Lil Jon made a surprise convention appearance to express his support for Kamala Harris. The rapper is from Atlanta, while DJ Snake, his counterpart on the track, is from Guam : Espresso - Sabrina Carpenter

The summer hit, which has over a billion streams on Spotify, is one of several songs that may have been chosen simply for their mass appeal — and understandably so. In June, Carpenter became the first artist since The Beatles to have two songs debut within the top three spots on the Billboard Hot 100.

Hawai’i : 24K Magic - Bruno Mars

R&B and funk musician Mars is from Honolulu, Hawai'i.

Idaho : Private Idaho - The B-52's

"Private Idaho" was a single off the Georgia band's second album, though they didn't play a show in the state of Idaho until 2011.

Illinois : Sirius - The Alan Parsons Project

"Sirius" was the walk-on music for the Chicago's NBA team, the Bulls.

Indiana - Don't Stop 'til You Get Enough - Michael Jackson

Jackson was born in Gary, Ind. — the eighth of 10 children.

Iowa : Celebration - Kool & The Gang

A classic party anthem, Kool & The Gang actually hail from New Jersey. Meanwhile, Iowa passed on their hometown heroes of the band Slipknot.

Kansas : Carry On Wayward Son - Kansas

The band Kansas was formed in the state in 1973, hailing from its capital city of Topeka.

Kentucky : First Class - Jack Harlow

Rapper and singer Harlow was born in Louisville, Ky., and raised in Shelbyville.

Louisiana : All I Do Is Win - DJ Khaled

Rapper and producer DJ Khaled is from New Orleans.

Maine : Shut Up and Dance - WALK THE MOON

It’s a universally adored pop hit, even if the state did borrow it from a Cincinnati, Ohio, band.

Maryland : Respect - Aretha Franklin

Using an anthem by the queen of soul — with roots in Tennessee and Michigan — is the only reason we can think of to pass on Billie Holiday, Toni Braxton and David Byrne, who are among other talent with Maryland ties.

Massachusetts : I’m Shipping Up to Boston - Dropkick Murphys

The American Celtic band was formed in Quincy, Mass. The song itself describes a sailor with a missing leg, who is going to Boston in search of a wooden prosthetic.

Michigan : Lose Yourself - Eminem

The rapper famously grew up in Detroit and his 2002 movie 8 Mile is set in the Motor City.

Minnesota : Kiss - Prince & The Revolution, 1999 - Prince & The Revolution