- Tools and Resources

- Customer Services

- Addictions and Substance Use

- Administration and Management

- Aging and Older Adults

- Biographies

- Children and Adolescents

- Clinical and Direct Practice

- Couples and Families

- Criminal Justice

- Disabilities

- Ethics and Values

- Gender and Sexuality

- Health Care and Illness

- Human Behavior

- International and Global Issues

- Macro Practice

- Mental and Behavioral Health

- Policy and Advocacy

- Populations and Practice Settings

- Race, Ethnicity, and Culture

- Religion and Spirituality

- Research and Evidence-Based Practice

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Work Profession

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Article contents

Gender identity and gender expression.

- Jama Shelton Jama Shelton Hunter College, City University of New York

- https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780199975839.013.1324

- Published online: 21 June 2023

Gender identity and gender expression are aspects of personal identity that impact an individual across multiple social dimensions. As such, it is critical that social workers understand the role of gender identity and gender expression in an individual’s life. Many intersecting factors contribute to an individual’s gender identity development and gender expression, as well as their experiences interacting with individuals, communities, and systems. For instance, an individual’s race, geographic location, disability status, cultural background, religious affiliation, age, economic status, and access to gender-affirming healthcare are some of the factors that may impact experiences of gender identity and gender expression. Gender identity and expression are dimensions of diversity that social workers will interact with at all levels of practice. As such, it is important for social work educational institutions to ensure their students are prepared for practice with people of all gender identities and expression, while also understanding the historical context of the social work profession in relation to transgender populations and the ways in which the profession has reinforced the sex and gender binaries.

- gender binary

- gender equity

- gender identity

- gender expression

What Are Gender Identity and Gender Expression?

Every individual has a gender identity, and every individual expresses their gender (see Table 1 ). Gender identity and gender expression are often referenced in relation to transgender, nonbinary, and gender-expansive people, yet one’s gender and the expression of gender are dimensions of identity that every individual possesses. Gender identity can be understood as an individual’s internal sense of self as it relates to gender. One’s gender is a deeply felt, personal sense of self as a girl/woman, boy/man, both a girl/woman and a boy/man, neither a girl/woman nor a boy/man, or a combination of a girl/woman and a boy/man. Additional words people may use to describe their gender include (but are not limited to): nonbinary, gender expansive, agender, multigender, two-spirited, gender-fluid, genderqueer, and muxe. Importantly, there is no external source that can dictate an individual’s gender identity.

Gender expression refers to the ways in which an individual expresses their gender outwardly. Gender expression may include an individual’s dress, hairstyle, mannerisms, and behaviors. These are typically based on stereotypes about gender within a particular cultural context. An individual’s gender expression may or may not conform to social norms that are typically associated with an individual’s gender or with gendered assumptions based on an individual’s assigned sex. Importantly, an individual’s gender presentation may or may not reflect their gender identity. Issues such as personal safety and access to accurately gendered items may impact an individual’s ability to express their gender in a way that aligns with their gender identity.

Table 1. Additional Relevant Terms

The sex and gender binaries.

The terms gender and sex are often used interchangeably. While these terms may be related in some instances, they are not the same. An individual’s sex is connected to their chromosomes, hormones, and anatomy. Typically, an individual is assigned a sex at birth, if not prior to birth. A sex assignment is most often made based on the appearance of a baby’s genitals. The options for sex assignment have historically been either male or female, which is then listed on an individual’s birth certificate. This is still often the case in the United States, even though evidence demonstrates that sex is not a binary construct ( Fausto-Sterling, 2018 ). Some states in the country allow an additional option (X) for the classification of sex on the birth certificate. While it is beyond the scope of this article to examine the category of intersex (discussed in “XXX”), intersex people cannot be overlooked in discussions of sex and gender. The binary construction of sex assumes the existence of only two sexes. This is an inaccurate and limiting construct that ignores human variability. Not only is it inaccurate and limiting, it is also harmful. Intersex babies and children often undergo surgical procedures that they do not consent to, and are required to take hormones in order to make their bodies fit within a binary that their bodies directly challenge.

An individual’s gender is most often presumed based on their sex assignment, and is presumed to fall within the binary gender categories of girl/woman and boy/man. For instance, if a baby is assigned female, the assumption is that the baby is a girl and will grow up to be a woman. With this assumption comes a set of gendered norms and expectations, societally reinforced in myriad ways including options for grooming and dress, presumptions about appropriate behavior and presentation, and even the choice of language used to praise or discipline (“such a pretty girl” or “that’s not ladylike”). However, an individual’s assigned sex does not always predict their gender; gender identity is more strongly linked to an individual’s experience of gender than to assigned sex ( Olson et al., 2015 ). Yet, the connection between an individual’s sex and their gender and the binary constructions of both sex and gender are so widely taught that this misperception is pervasive in the United States and in many Western countries despite the fact that “defining gender as a condition determined strictly by a person’s genitals is based on a notion that doctors and scientists abandoned long ago as oversimplified and often medically meaningless” ( Grady, 2018 ). In addition to the limitations of these binary categories, sex and gender are often viewed as immutable and stable over time. The lived experiences of intersex, nonbinary, transgender, and gender-expansive people demonstrate the inaccuracy of the binary system of sex and gender categorization.

It is important to note that an individual’s identification within the gender binary is not itself problematic. Because many laws and policies in the United States are based on a binary construction of sex and/or gender, it is the classification system itself that is flawed. Binary classifications are problematic when identification with the gender binary and associated gender expressions are required for entry within social and legal systems.

Beyond the Binary: Reconceptualizing Gender Identity and Gender Expression

Some think about gender identity and gender expression as a continuum, with binary classifications marking the endpoints and a range of identities and expressions in between. More contemporary understandings assert that gender identity and gender expression exist more as a “galaxy” rather than a continuum ( Action Canada for Sexual Health and Rights, n.d. ). This thinking is more in alignment with moving beyond binary conceptualizations of gender altogether and situates all gender identities and gender expressions as equally viable, without relying on the containment of binary categories.

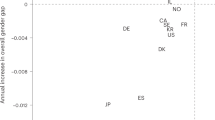

Moving beyond the gender binary not only improves the lived experiences of transgender, nonbinary, and gender-expansive people but also opens up possibilities for everyone . The construct of gender carries with it prescribed ways of being ranging from what is “appropriate” physical and behavioral gender expression to what are appropriate fields of study and career choices. Truly moving beyond the gender binary can liberate all people from the constraints inherent in presumptive and prescribed notions of what is deemed socially, culturally, and politically appropriate.

How could moving beyond the gender binary be operationalized within the social work profession? Prior to discussing suggestions for moving beyond the binary in social work education, practice, and research, it is important to first examine the history of the social work profession as it relates to gender identity and gender expression.

Social Work, Gender Identity, and Gender Expression: A Brief History

Historically, the social work profession is rife with demands that nonconforming gender expressions and bodies adapt to mainstream gendered expectations. Examples include the profession’s support for the assimilative Native American Residential Schools, electroconvulsive therapies intended to “cure” homosexuality, and a host of welfare eligibility requirements that serve to police Black families for their deviation from White heteronormative standards ( Bowles & Hopps, 2014 ). Thus, common practices centered around promoting access to resources through acclimating and gaining membership to the status quo. As such, the profession of social work has been complicit in the policing of gender and the maintenance of the gender binary. It is important for the profession to reckon with this disciplinary approach to gender identity and expression in the past, while also developing equitable frameworks for the future.

The primary formal mechanism for the policing of gender and, thus the reification of the gender binary, is the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM). Gender identity disorder was first included in the DSM-III in 1980 , and included the diagnoses “gender identity disorder of childhood” and “transsexualism.” When updated in 1987 , the new DSM-III-R included gender identity disorder of adolescence and adulthood, nontranssexual type ( Drescher, 2009 ). Gender identity disorder of adolescence and adulthood, nontranssexual type, was removed from the DSM-IV and replaced with the category gender identity disorder, a diagnosis encompassing both gender identity disorder of childhood and transsexualism ( Shelton et al., 2019 ). The most recent version of the DSM (the DSM-5) replaced gender identity disorder with gender dysphoria. This shift in diagnostic terminology signifies a change in the understanding of the root causes of the challenges individuals face when their gender identity and gender expression fall outside of the dominant societal norms prescribed to the gender associated with their assigned sex. Namely that societal definitions of and expectations surrounding gender do not accurately reflect people’s lived experience of gender. However, the fact that a mental health diagnosis remains in the DSM is considered problematic by many, as gender related dissonance continues to be constructed as individual pathology.

The DSM solidified the notion of a gendered norm any deviation from which required correction. For decades, the remedy was to fit an individual into a gender that aligned with the expectations associated with their assigned sex. Through modern medicine, a new type of “correction” emerged for those who could gain access, through hormone treatment and affirming surgeries. Though these interventions are medical in nature, the psychiatric diagnoses remain a driving force in accessing these treatments. Further, gender-affirming treatments have reinforced the necessity of binary gender conformity, by supporting an individual in their transition from one gender to the other gender. It is important to note here that these treatments have been and continue to be life-saving for many individuals, and that identifying with the gender binary is not in itself problematic. As already stated, the gender binary is problematic when a binary classification is imposed and/or presumed and is not in alignment with an individual’s stated gender and understanding of their own body ( Ansara & Hegarty, 2012 ), and when identification or categorization within the gender binary is required for entry into and acceptance within social and legal systems ( Shelton et al., 2019 ).

The National Association of Social Workers released a position statement denouncing the continued inclusion of gender identity related diagnoses in the DSM-5, stating that diagnoses such as gender dysphoria should be approached from a medical model rather than a mental health model. Because of the authority that the DSM holds in social work and related professions, the inclusion of gender dysphoria perpetuates the notion that the variability of gender is a psychiatric condition, reinforcing cisnormativity and the binary gender system. Advocacy organizations argue that until gender related diagnoses are removed from the DSM, transgender and gender-expansive people will continue to suffer from stigma, discrimination, and the invalidation of their identities and experiences.

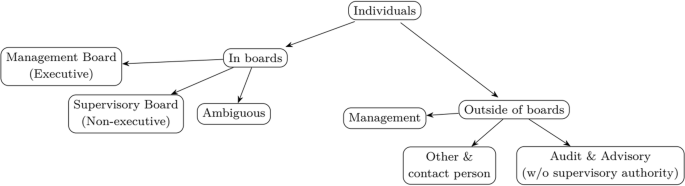

Social workers may find themselves in a gatekeeping role when working with individuals whose gender identity and/or gender expression expand beyond binary classifications or stretch the boundaries of what is typically considered appropriate gendered behavior based on an individual’s sex assignment. For instance, according to the Standards of Care put forth by the World Professional Association for Transgender Health ( WPATH, 2012 ), in order to access gender-affirming care (such as hormone treatment or surgery), an individual must obtain a letter of recommendation from a qualified mental health professional diagnosing their persistent gender dysphoria and indicating their readiness for care ( Coleman et al, 2022 ). Thus, the notion that individuals whose gender identities expand beyond the binary cisgender norm are not only pathologized but also viewed as incapable of owning their own bodily expertise. The same requirements are not expected from cisgender individuals seeking body altering surgeries, such as breast augmentation, hair implants, or facelifts.

Notably, not every nonbinary, gender-expansive, or transgender individual desires gender-affirming medical procedures. There is no single way to be nonbinary, gender expansive, or transgender, just as there is no single way to be a girl, woman, boy, or man. Each individual person experiences and expresses their gender in their own unique way.

Social Work and Gender Equity

Social workers are charged with confronting injustice; social justice is a core value of the profession. In recognition of the social worker’s responsibility to work toward social justice, the Council on Social Work Education (CSWE) (2015 ) generated accreditation standards requiring social workers to understand diversity and difference in the context of privilege, power, oppression, and marginalization to eliminate biases (Competency 2). Because gender identity and gender expression are included as dimensions of diversity that professionals must understand and value, social workers have an ethical commitment to advance gender equity in all professional practice, education, and research activities. The National Association of Social Workers (NASW) Code of Ethics ( 2017 / 1996 ) includes gender identity and gender expression as specific categories to include when confronting discrimination. The Code of Ethics ( 2017 / 1996 , p. 21) states that “social workers should not practice, condone, facilitate, or collaborate with any form of discrimination on the basis of ... sexual orientation, gender identity or expression.”

In order to meet CSWE’s Competency 2—that social workers must understand diversity and difference in the context of privilege, power, oppression, and marginalization to eliminate biases—it is important that the profession broadens its analysis from individual and interpersonal acts of discrimination to include social systems and institutions that permit individual and interpersonal acts of discrimination. In other words, the role of structural discrimination in the oppression of people based on their gender identity and/or gender expression must be addressed. Structural discrimination can be understood as “the policies of dominant race/ethnic/gender institutions and the behavior of the individuals who implement these policies and control these institutions, which are race/ethnic/gender neutral in intent but which have a differential and/or harmful effect on minority race/ethnic/gender groups” ( Pincus, 1996 , p. 186).

To engage from within a structural framework would require social workers to address the structural conditions that marginalize people on the basis of their gender identity and/or gender expression. For example, rather than working with people to cope with the gender identity and expression based marginalization they face, social workers would also address the systems and structures that produce and reinforce marginalization. This may include challenging policies and practices within institutions of social work practice and education that rely on a binary classification of gender as a way to organize and categorize people. It may include insisting that all gender restrooms are accessible to all clients in one’s agency, or becoming involved in advocacy efforts aimed at removing gender identity based diagnoses from the DSM.

Social workers can begin to move beyond the gender binary by taking an inventory of the policies and practices within their organizations, critically examining the ways in which they may be inadvertently marginalizing clients and communities based on gender identity and gender expression. By centering transgender and nonbinary people in their examinations of policy and practice, social workers can intentionally assess their inclusion of and impact on transgender, nonbinary, and gender-expansive people. Because societal systems and services were built on the premise of binary sex and gender, they are rooted in the presumption that every individual who comes into contact with them can be categorized within these binary constructions. Public restrooms provide a concrete example. Social norms around restroom use necessitate that males and females are separated in different rooms, even with the physical separation of locked and partitioned stalls. In instances when public restrooms are single occupancy, they are most often still labeled male and female. The rationale for this separation is often safety and privacy. As Davis (2014 , p. 53) asserts, “If privacy and safety are the main reasons for sex-segregated restrooms, then might alternative physical designs such as floor-to-ceiling stall partitions do an even better job of meeting that goal than the current design of most American public restrooms?”

With regard to social work education, Shelton and Dodd (2020 ) outline key strategies for challenging cisnormativity and moving beyond the gender binary, including:

Use all gender pronouns (they and them) when speaking and writing rather than only including she and he or his and hers, an example of binarizing ( Blumer et al., 2013 ).

Examine and review course syllabi for implicit cisnormativity. Include your name and pronouns, ensure gender identity and expression are a part of classroom nondiscrimination standards, avoid binarizing language, and identify any all-gender restrooms available in the building.

Examine and review content on course syllabi. Ensure readings by and about transgender people are included. Transgender topics and authors should appear in a unit on gender identity. When planning a session about parenting, for instance, include a reading about transgender, gender-expansive, genderqueer, or nonbinary parents.

Be intentional when planning classroom introductions. Some students may not use the names indicated on your class roster or on school records. Plan introductions in such a way that enables students to introduce themselves first (before reading names from the provided class roster).

Model the sharing of pronouns and give students the option to include their pronouns when introducing themselves. For example, you could say, “Please share your name and your pronouns if you would like to do so.”

When utilizing case examples in the classroom, make sure transgender people are included/represented.

When including transgender people in case examples, make sure they are included in a way that does not perpetuate negative stereotypes and misinformation. For instance, a case example including a transgender person does not need to be focused solely on gender dysphoria and does not need to be related to their transgender identity.

Engage students in nuanced discussions about the history of the pathologization of gender and sexual minorities and the role of social work in this history.

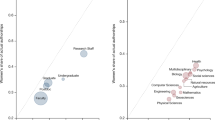

Social work researchers can concretely work toward gender equity throughout the research process, helping to ensure all gender identities and gender expressions are acknowledged as valid. From the design of demographic questions to the reporting of results, researchers can intentionally include participants with a range of gender identities and expressions. Demographic questions can include additional options for sex and gender beyond the binary categorizations of female/male, woman/man, or girl/boy. When analyzing quantitative data, researchers can opt out of collapsing sex and/or gender into a dichotomous variable. Though this may make the process of analysis less simple, making these variables dichotomous erases the lived experiences of participants. When reporting results, researchers can include the experiences of participants across a range of gender identities and gender expressions. In reporting only statistically significant findings, critical data about frequently marginalized and underrepresented populations is lost. Recruitment strategies should include specific outreach to individuals and communities of diverse gender identities and gender expressions. This will require community engaged research and a willingness to extend recruitment timelines to ensure adequate representation. A 2021 study from the Williams Institute reported that 1.2 million adults in the United States are nonbinary ( Wilson & Meyer, 2021 ). Expanding beyond binary conceptualizations of gender within social work research is imperative in order to address the health and well-being of nonbinary individuals and communities.

In summary, gender identity and gender expression are dimensions of identity that are relevant to and impact all people. Thus, it is important for social workers to understand the ways in which gender identity and gender expression impact the individuals and communities with whom they work, as well as the ways that systems and institutions may perpetuate bias and marginalization based on gender identity and gender expression. Although the profession of social work has a fraught history with regard to policing and pathologizing individuals whose gender identities and expressions exist outside of or in between the gender binary, contemporary practice charges social workers with confronting injustice, including dimensions of diversity such as gender identity and gender expression.

Further Reading

- Bilodeau, B. , & Renn, K. (2005). Analysis of LGBT identity development models and implications for practice. New Directions for Student Services , 111 , 25–39.

- Burdge, B. (2007). Bending gender, ending gender: Theoretical foundations for social work practice with the transgender community. Social Work , 52 (3), 243–250.

- Butler, J. (2004). Undoing gender . Routledge.

- James, S. E. , Herman, J. L. , Rankin, S. , Keisling, M. , Mottet, L. , & Anafi, M. (2016). The report of the 2015 U.S. transgender survey . National Center for Transgender Equality.

- Kroehle, K. , Shelton, J. , Clark, E. , & Seelman, K. (2020). Mainstreaming dissidence: Confronting binary gender in social work’s grand challenges. Social Work , 65 (4), 368–377.

- Sanger, T. (2008). Queer(y)ing gender and sexuality: Transgender people’s lived experiences and intimate partnerships. In L. Moon (Ed.), Feeling queer or queer feelings? Radical approaches to counselling sex, sexualities and genders (pp. 72–88). Routledge.

- Action Canada for Sexual Health and Rights . (n.d.). Gender galaxy .

- Ansara, Y. , & Hegarty, P. (2012). Cisgenderism in psychology: Pathologising and misgendering children from 1999 to 2008. Psychology & Sexuality , 3 (2), 137–160.

- Blumer, M. L. C. , Ansara, Y. G. , & Watson, C. M. (2013). Cisgenderism in family therapy: How everyday clinical practices can delegitimize people’s gender self-designations. Special Section: Essays in Family Therapy. Journal of Family Psychotherapy , 24 (4), 267–285.

- Bowles, D. D. , & Hopps, J. G. (2014). The profession’s role in meeting its historical mission to serve vulnerable populations. Advances in Social Work , 15 (1), 1–20.

- Council on Social Work Education . (2015). Educational policy and accreditation standards .

- Coleman, E. , Radix, A. E. , Bouman, W. P. , Brown, G. R. , de Vries, A. L. C. , Deutsch, M. B. , Ettner, R. , Fraser, L. , Goodman, M. , Green, J. , Hancock, A. B. , Johnson, T. W. , Karasic, D. H. , Knudson, G. A. , Leibowitz, S. F. , Meyer-Bahlburg, H. F. L. , Monstrey, S. J. , Motmans, J. , Nahata, L. , Nieder, T. O. , … Arcelus, J. (2022). Standards of Care for the Health of Transgender and Gender Diverse People, Version 8 . International journal of transgender health, 23(Suppl 1), S1–S259.

- Davis, H. (2014). Sex-classification policies as transgender discrimination: An intersectional critique. Perspectives on Politics , 12 (1), 45–60.

- Drescher, J. (2009). Queer diagnoses: Parallels and contrasts in the history of homosexuality, gender variance, and the diagnostic and statistical manual. Archives of Sexual Behavior , 39 , 427–460.

- Fausto-Sterling, A. (2018, October 15). Why sex is not binary. The New York Times .

- Grady, D. (2018, October 2). Anatomy does not determine gender, experts say . The New York Times , 10A.

- National Association of Social Workers . (2017). The NASW code of ethics (Rev. ed.). (Original work published 1996)

- Olson, K. R. , Key, A. C. , & Eaton, N. R. (2015). Gender cognition in transgender children. Psychological Science , 26 (4), 467–474.

- Pincus, F. (1996). Discrimination comes in many forms: Individual, institutional, and structural. The American Behavioral Scientist , 40 (2), 186–194.

- Shelton, J. , & Dodd, S. J. (2020). Beyond the binary: Addressing cisnormativity in the social work classroom. Journal of Social Work Education , 56 (1), 179–185.

- Shelton, J. , Kroehle, K. , & Andia, M. (2019). The trans person is not the problem: Brave spaces and structural competence as educative tools for trans justice in social work. Journal of Sociology and Social Welfare , 46 (4), 97–123.

- World Professional Association for Transgender Health . (2012). Standards of Care for the Health of Transsexual, Transgender, and Gender Nonconforming People [7 th Version].

- Wilson, B. D. M. , & Meyer, I. (2021). Nonbinary LGBTQ adults in the United States . The Williams Institute.

Related Articles

- Disparities and Inequalities: Overview

- Social Justice

- Transgender People

- Discrimination

Printed from Encyclopedia of Social Work. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a single article for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

date: 01 June 2024

- Cookie Policy

- Privacy Policy

- Legal Notice

- Accessibility

- [66.249.64.20|185.66.14.236]

- 185.66.14.236

Character limit 500 /500

- Open access

- Published: 09 February 2022

A review of the essential concepts in diagnosis, therapy, and gender assignment in disorders of sexual development

- Vivek Parameswara Sarma ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-9484-7090 1

Annals of Pediatric Surgery volume 18 , Article number: 13 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

5666 Accesses

1 Altmetric

Metrics details

The aim of this article is to review the essential concepts, current terminologies and classification, management guidelines and the rationale of gender assignment in different types of differences/disorders of sexual development.

The basics of the present understanding of normal sexual differentiation and psychosexual development were reviewed. The current guidelines, consensus statements along with recommendations in management of DSD were critically analyzed to formulate the review. The classification of DSD that is presently in vogue is presented in detail, with reference to old nomenclature. The individual DSD has been tabulated based on various differential characteristics. Two schemes for analysis of DSD types, based on clinical presentation, karyotype and endocrine profile has been proposed here. The risk of gonadal malignancy in different types of DSD is analyzed. The rationale of gender assignment, therapeutic options, and ethical dimension of treatment in DSD is reviewed in detail.

The optimal management of different types of DSD in the present era requires the following considerations: (1) establishment of a precise diagnosis, employing the advances in genetic and endocrine evaluation. (2) A multidisciplinary team is required for the diagnosis, evaluation, gender assignment and follow-up of these children, and during their transition to adulthood. (3) Deeper understanding of the issues in psychosexual development in DSD is vital for therapy. (4) The patients and their families should be an integral part of the decision-making process. (5) Recommendations for gender assignment should be based upon the specific outcome data. (6) The relative rarity of DSD should prompt constitution of DSD registers, to record and share information, on national/international basis. (7) The formation of peer support groups is equally important. The recognition that each subject with DSD is unique and requires individualized therapy remains the most paramount.

The aim of this article is to review the essential concepts, current terminologies and classification, management guidelines, and the rationale of gender assignment in different types of differences/disorders of sexual development (DSD). The basics of the present understanding of normal sexual differentiation and psychosexual development were reviewed. The current guidelines, consensus statements along with recommendations in management of DSD were critically analyzed to formulate the review. The classification of DSD that is presently in vogue is presented in detail, with reference to old nomenclature. The individual DSD has been tabulated based on various differential characteristics. Two schemes for analysis of DSD types, based on clinical presentation, karyotype, and endocrine profile has been proposed here. The risk of gonadal malignancy in different types of DSD is analyzed. The rationale of gender assignment, therapeutic options, and ethical dimension of treatment in DSD is reviewed in detail.

The normal sexual differentiation

The normal pattern of human sexual development and differentiation that involves specific genetic activity and hormonal mediators [ 1 , 2 ] is explained by the classical Jost’s paradigm; the essence of which is narrated below [ 3 ].

The establishment of chromosomal sex (XX or XY) occurs at the time of fertilization. The variations in sex chromosome include XO, XXY or mosaicism as in XO/XY.

Chromosomal sex influences the determination of the gonadal sex, thus differentiating the bipotential gonadal ridge into testis or ovary. (Variations in gonadal sex include ovotestis and streak gonad.) The SRY gene (referred to as the testis-determining gene) on the short arm of Y chromosome directs the differentiation into testes, with formation of Leydig and Sertoli cells [ 4 , 5 ].

The sex phenotype (internal and external genitalia) is determined by the specific hormones secreted by the testes, which translates the gonadal sex into phenotype. Testosterone secretion by Leydig cells promotes Wolffian duct differentiation into vas deferens, epididymis, and seminal vesicles. The Wolffian ducts regress in the absence of androgenic stimulation. Testosterone is converted to dihydrotestosterone (DHT), by 5-alpha reductase, which results in masculinization of external genitalia, closure of urethral folds, and development of the prostate and scrotum. In the absence of influence of SRY gene, the development of bipotential gonad will evolve along the female pathway. Thus, the Mullerian ducts develop (even without any obvious hormonal input) into the uterus, fallopian tubes, and the proximal 2/3 of vagina. DHT is also important for the suppression of development of the sinovaginal bulb, which gives rise to the distal 1/3 of vagina. The fact that internal duct development reflects the ipsilateral gonad (due to the paracrine effect of sex hormones) is an important consideration in the understanding of specific types of DSD. The anti-Mullerian hormone (AMH) from Sertoli cells of Testis is vital for the regression of Mullerian structures. Therefore, Wolffian structures will develop on one side, along with Mullerian duct regression, only in the presence of a fully functional testis. But, Mullerian duct structures develop on one side even in the presence of an ipsilateral streak gonad. The genital tubercle develops as a clitoris, the urethral folds form the labia minora, and the labioscrotal swellings form the labia majora [ 1 , 2 , 4 , 5 , 6 ].

The concept of psychosexual development was added to the above sequence by Money et al. [ 7 ]. The brain undergoes sexual differentiation consistent with the other characteristics of sex. It is proposed that androgens organize the brain in early development and pubertal steroids activate the same, leading to masculine behavior. The sexual differentiation of genitalia occur in first 2 months of pregnancy, while sexual differentiation of brain occurs in the second half of pregnancy, and hence these processes can be influenced independently. Therefore, the extent of virilization of genitalia may not reflect the extent of masculinization of brain [ 8 , 9 ].

Psychosexual development is a complex and multifactorial process influenced by brain structure, genetics, prenatal and postnatal hormonal factors, environmental, familial, and psychosocial exposure [ 10 , 11 , 12 ]. Psychosexual development is conceptualized as three components: (1) gender identity is defined as the self-representation of a person as male, female or even, neither. (2) Gender role (sex-typical behavior) describes behavior, attitudes and traits that a society identifies as masculine or feminine. (3) Sexual orientation denotes the individual responsiveness to sexual stimuli, which includes behavior, fantasies, and attractions (hetero/bi/homo-sexual).

Psychosexual development is influenced by various factors such as Androgen exposure, sex chromosome genes, brain structure, family dynamics and social structure. With reference to altered psychosexual development, two conditions are important to be recognized and differentiated. (1) Gender dissatisfaction denotes unhappiness with the assigned sex, the etiology of which is poorly understood. (With respect to subjects with DSD, it has to be remembered that homo-sexual orientation or cross-sex interest is not considered an indication of incorrect gender assignment.) (2) Gender dysphoria (GD) is characterized by marked incongruence between the assigned gender and experienced/expressed gender, which is associated with clinically significant functional impairment. (It can occur in the presence or absence of DSD) [ 12 , 13 , 14 ].

The term “disorders/differences of sex development” (DSD) is defined as congenital anomalies in which development of chromosomal, gonadal, or phenotypic sex (including external genitalia/internal ductal structures) is atypical. In a wider perspective, DSD includes all conditions where chromosomal, gonadal, phenotypical, or psychological sex are incongruent. The three components of psychosexual development also may not always be concordant in DSD [ 15 , 16 ].

A greater understanding of underlying genetic and endocrine abnormalities has necessitated refinement in terminologies and classification of DSD. The newer classification of DSD aims to be more precise, specific, flexible, and inclusive of advances in genetic diagnosis, while being sensitive to patient concerns (Table 1 ). Terms such as intersex, hermaphrodite, pseudohermaphrodite, and sex reversal are avoided, to this end, in diagnostic terminologies. Presently, a specific molecular diagnosis is identified only in about 20% of all DSD. The majority of virilized 46 XX infants will have CAH, but only 50% of 46 XY DSD will have a definitive diagnosis [ 16 , 17 ].

For the purpose of understanding of the basic pathology and ease of comprehension, DSD can be classified as follows:

Sex chromosomal DSD: here, the sex chromosome itself is abnormal. This includes XO (Turner syndrome), XXY (Klinefelter’s syndrome), mosaic patterns of XO/XY (Mixed Gonadal Dysgenesis and Partial Gonadal Dysgenesis), XX/XY (Ovotesticular DSD), and even SRY-positive XX in 46 XX testicular DSD (de la Chapelle syndrome). These are essentially genetic anomalies characterized by a varying degrees of gonadal dysgenesis/abnormal gonadal differentiation secondary to the sex chromosome defect and in certain situations, associated systemic abnormalities and increased risk of malignancies. The phenotypic sex (internal ductal structures and external genitalia) reflects the gonadal sex.

Disorders of gonadal development: these are characterized by abnormal gonadal development, in the absence of any obvious sex chromosomal abnormality, i.e., Karyotype is either 46 XX or 46 XY. It includes 46 XY complete gonadal dysgenesis (Swyer syndrome), 46 XY partial gonadal dysgenesis, 46 XY ovotesticular DSD, 46 XX pure gonadal dysgenesis (Finnish syndrome) and 46 XX ovotesticular DSD. Here also, the phenotypic sex reflects the gonadal sex (streak or dysgenetic gonads/ovotestis).

Abnormalities in phenotypic sex secondary to hormonal defects: these are characterized by normal chromosomal sex (46 XX or 46 XY) and gonadal sex (testes/ovaries), but abnormal phenotype (internal ductal and/or external genital) due to defects in hormonal function. In 46 XY DSD, this can be due to defects in synthesis or action of androgens or less commonly, AMH. In 46 XX DSD, this is due to androgen excess, as in Congenital Adrenal Hyperplasia, or less commonly, gestational hyperandrogenism.

Primary endocrine abnormalities: These are characterized by a severe underlying endocrine abnormality, as in congenital hypogonadotropic hypogonadism or pan-hypopitutarism.

Malformation syndromes: these are characterized by the presence of genital abnormalities due to severe congenital anomalies including persistent cloaca, cloacal exstrophy, Mullerian agenesis/MRKH syndrome, or vaginal atresia.

The common pattern of correlation of gonadal sex with internal duct structure development is summarized in Table 2 . The cardinal characteristics of chromosomal, gonadal, and phenotypic sex in the individual types of DSD is summarized in Table 3 .

The genetic testing in DSD

For a sex chromosome DSD, no further genetic analysis is required. However, a DSD with 46 XX or 46 XY karyotype, the underlying etiology may be a monogenic disorder where the candidate gene has to be analyzed. The algorithm of genetic analysis of DSD is defined according to the results of sex chromosome complement (karyotyping/array CGH or SNP array) and presence of regions of Y chromosome (FISH/QFPCR). The next step is to study specific genes involved in gonadal development by techniques including Sanger sequencing combined with MLPA to assess specific genetic defects. Further analysis includes evaluation for causes of monogenic DSD or analysis of copy number variations (CNV) or both. Panels for candidate genes (CYP21A2 in CAH, AR in androgen insensitivity syndrome) provide rapid and reliable results. The evolving use of whole exome sequencing (WES) and whole genome sequencing (WGS) aim to identify previously unrecognized genetic etiology of DSD.

The further characterization of 46 XY DSD

The further characterization of individual types of 46 XY DSD based on endocrine and genetic evaluation is summarized in Table 4 . The selective use of the following investigations is required in 46 XY DSD to arrive at a specific diagnosis of the subtype:

Assay of serum testosterone, LH and FSH.

hCG stimulation test, to assess response in testosterone levels.

Assay of AMH, to detect the presence of functioning testicular tissue.

Testosterone: dihydrotestosterone (DHT) ratio.

Testosterone: androstenedione ratio.

ACTH test, for the diagnosis of testosterone biosynthesis defects.

Specific substrates like progesterone, 17-OHP, and 1-OH pregnenelone, for typing of Androgen biosynthesis defects.

Ultrasound scan/MRI and laparoscopy for the detection of Mullerian structures.

Gonadal biopsy for the diagnosis of ovotesticular DSD and gonadal dysgenesis.

Genetic testing including screening of androgen receptor gene for mutations, Molecular testing for 5-alpha reductase-2 gene mutations, androgen receptor expression, and androgen binding study in genital skin fibroblasts.

The further characterization of 46 XX DSD is summarized in Table 5 . The classification of the major types of DSD based on the different clinical manifestations is summarized in Table 6 .

Gonadal dysgenesis syndromes

There are five common patterns of gonadal dysgenesis syndromes, in addition to the dysgenetic ovotestis which is found in 46 XX or 46 XY ovotesticular DSD.

46 XY complete gonadal dysgenesis (Swyer syndrome)

46 XY partial gonadal dysgenesis (Noonan syndrome)

45 XO/46 XY mixed gonadal dysgenesis

46 XX pure gonadal dysgenesis (Finnish syndrome)

45 XO Turner’s syndrome.

Gender assignment in DSD

The classical “optimal gender policy” involved early sex assignment and surgical correction of genitalia and hormonal therapy, with the objective of an unambiguous gender of rearing, that will influence the future gender identity and gender role [ 7 , 11 ]. The genital phenotype (characteristics of genitalia) has historically been the guide for gender assignment, considering esthetic, sexual, and fertility considerations. This perspective, which assumes psychosexual neutrality at birth, has been challenged now, with the present focus shifting to the importance of prenatal and genetic influences on psychosexual development. In addition to the progress in the diagnostic techniques and therapeutic modalities, there has been greater understanding of the associated psychosocial issues and acceptance of patient advocacy [ 19 , 20 , 21 ].

Factors to be considered for gender assignment in DSD

The most common gender identity outcome, observed incidence of GD, and requirement of gender reassignment in the specific type of DSD from available data.

The most common pattern of psychosexual development in the particular DSD, consistent with established neurological characteristics.

The requirement of genital reconstructive surgery to conform to the assigned sex.

The estimated risk of gonadal malignancy and need for gonadectomy (Table 7 ).

The requirement, possible response, and timing of HRT.

The expected post-pubertal cosmetic and functional outcome of genitalia, after reconstruction where required.

The potential for fertility, even with the presumed aid of assisted reproduction techniques.

Though GD in patients with DSD influences, the choice of gender assignment (and reassignment), sexual orientation, and gender-atypical behavior do not affect the decision-making process in gender assignment of DSD [ 22 ].

Gender assignment in neonates should be done only after expert evaluation. The evaluation, therapy, and long-term follow-up should only be done at a centre with an experienced multidisciplinary team. The multidisciplinary team for management of DSD should include pediatric subspecialists in endocrinology, surgery/urology, genetics, gynecology, and psychiatry along with pediatrician/neonatologist, psychologist, specialist nurse, social worker, and medical ethicist. The core group will vary according to the type of DSD. All individuals with DSD should receive the appropriate gender assignment [ 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 ]. The patient and family should be able to have an open communication and participation in the decision-making process. The concerns of patients and their families should be respected and addressed in strict confidence.

The rationale of gender assignment in different clinical conditions of DSD

The usually recommended gender assignment guidelines in different clinical types of DSD is summarized in Table 8 .

46 XX DSD—congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH)

In CAH, female gender identity is the most common outcome despite markedly masculinized gender-related behavior. Patients diagnosed in the neonatal period, particularly with lower degrees of virilization, should be assigned and reared as female gender, with early feminizing surgery. GD is rare when female gender is assigned. Those with delayed diagnosis and severely masculinized genitalia need evaluation by a multidisciplinary team. Evidence supports the current recommendation to rear such infants, even with marked virilization, as females [ 18 , 19 , 22 , 23 , 26 ]. A psychological counseling for children with CAH and their families, focused on gender identity and GD, is recommended.

46 XY complete gonadal dysgenesis

It is recommended to rear these children as female, due to following considerations: (a) these patients have typical female psychosexual development. (b) Reconstructive surgery is not required for the external genitalia to be consistent with female gender. (c) Hormonal replacement therapy (HRT) is required at puberty as streak gonads should be removed in view of high risk of gonadal malignancy. (d) Pregnancy is feasible with implantation of fertilized donor eggs and hormonal therapy [ 19 , 22 , 23 ].

Complete androgen insensitivity syndrome (CAIS)

It is recommended that subjects with CAIS should be reared as female, due to the following considerations: (a) they have well documented female-typical core psychosexual characteristics, with no significant GD, in accordance with the proposed absence of androgenization of the brain. (b) Surgical reconstruction of the genitalia is not required for consistency with female gender, though vaginoplasty may be necessary. (c) HRT is required with estrogens after gonadectomy, but testosterone replacement is untenable due to androgen resistance [ 18 , 19 , 22 , 23 , 26 ].

5-alpha reductase deficiency

Male gender assignment is usually recommended due to the following considerations: (a) the genital tissue is responsive to androgens. (b) The potential for fertility. (c) The reported high incidence of subjects requesting female-to-male gender reassignment after puberty*. (d) HRT is not required at puberty for patients reared as male, if testes are not removed. (e) As the risk of gonadal malignancy is low, testes can potentially be retained. (f) They are very likely to have a male gender identity.*(As most neonates with this disorder have female external genitalia at birth, they are reared as females. Profound virilization occurs at puberty, with a gender role change from female to male during adolescence in up to 63% cases.) About 60% of these patients, assigned female in infancy and virilizing at puberty, and all who are assigned male, live as males. When the diagnosis is made in infancy, the combination of male gender identity in the majority and the potential for fertility, should be considered for gender assignment [ 19 , 22 , 23 ].

17-beta-HSD-3 deficiency

Classical features are that of an undervirilized male. Some of the affected patients with feminine genitalia at birth are reared as females. Virilization occurs at puberty, with gender role change from female to male in up to 64% cases. They are highly likely to identify as males. Male gender assignment is recommended in partial defects. But there is no strong data to support male gender assignment, as in 5-alpha reductase deficiency. The other considerations against male gender assignment are the lack of reported cases of fertility and the intermediate risk of germ cell tumors. Hence, regular testicular surveillance is required for those reared as male, with retained testes. Therefore, gender assignment should be made considering all the above factors [ 18 , 19 , 22 , 23 , 26 ].

Partial androgen insensitivity syndrome (PAIS)

Infants with PAIS are assigned to male/female gender, depending partially on the degree of undervirilization. The virilization at puberty is also variable and incomplete. The response to hCG stimulation test/testosterone therapy can serve as a guide to the possible sex of rearing. The phenotype is highly variable in PAIS, which is correspondingly reflected in the sex of rearing. The gender identity has considerable fluidity in PAIS, though gender identity is usually in line with the gender of rearing. Though fertility is possible if the testes are retained, it should be remembered that there is an intermediate risk of gonadal germ cell tumors. Hence, gender assignment in these patients is a complex, multifactorial process [ 18 , 19 , 22 , 23 , 26 ].

47 XXY Klinefelter’s syndrome and variants

They usually report a male gender identity, but with a putative high incidence of GD, which needs to be elaborated in larger series.

Mixed gonadal dysgenesis

The genital phenotype is highly variable. The prenatal androgen exposure, internal ductal anatomy, testicular function at and after puberty, post-puberty phallic development, and gonadal location have to be considered to decide the sex of rearing.

- Ovotesticular DSD

These entities were previously referred to as “true hermaphroditism”, signifying the presence of both testicular and ovarian tissue, though dysgenetic, in the same subject. The three patterns seen are as follows:

46 XX/XY–33% of ovotesticular DSD, with testis and ovary/ovotestis.

46 XX–33% of ovotesticular DSD, with dysgenetic ovotestis.

46 XY–7% of ovotesticular DSD, with dysgenetic ovotestis.

This is characterized by ambiguity of genitalia or severe hypospadias at birth, with secondary sexual changes at puberty, corresponding to the relative predominance of ovarian/testicular tissue. The management depends on the age at diagnosis and anatomical differentiation. Either sex assignment is appropriate when the diagnosis is made early, prior to definition of gender identity. The sex of rearing should be decided considering the potential for fertility, based on gonadal differentiation and genital development. It should be ensured that the genitalia are, or can be made, consistent with the chosen sex [ 19 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 ].

General guidelines for surgery and HRT in DSD

Feminizing genitoplasty.

Surgery for correction of virilization (clitoral recession, with conservation of neurovascular and erectile structures, and labioplasty) should be carried out in conjunction with the repair of the common urogenital sinus (vaginoplasty). The current recommendation is to perform early, single-stage feminizing surgery for female infants with CAH. It is opined that correction in first year of life relieves parental distress related to anatomic concerns, mitigates the risks of stigmatization and gender identity confusion, and improves attachment between the child and parents. The current recommendation is the early separation of vagina and urethra, the rationale of which includes the beneficial effects of estrogen for wound healing in early infancy, limiting the postoperative stricture formation and avoidance of possible complications from the abnormal connection between the urinary tract and peritoneum through the Fallopian tubes. Surgical reconstruction in infancy may require refinement at puberty. Vaginal dilatation should not be undertaken before puberty. An absent or inadequate vagina, requiring a complex reconstruction of at high risk of stricture formation, may be appropriately delayed. But, the need for complete correction of urogenital sinus, prior to the onset of menstruation, is an important consideration [ 19 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 ].

Male genital reconstruction

The standard timing and techniques of operative procedures for correction of ventral curvature and urethral reconstruction, along with selective use of pre-operative testosterone supplementation is advised when male sex of rearing is adopted. The complexity of phallic reconstruction later in life, compared to infancy, is an important consideration in this regard. There is no evidence that prophylactic removal of discordant structures (utriculus/pseudovagina, Mullerian remnants) that are asymptomatic, is required. But symptoms in the future may mandate surgical removal. In patients with symptomatic utriculus, removal can be attempted laparoscopically, though it may not be practically feasible to preserve the continuity of vas deferens [ 19 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 ].

Gonadectomy

The gonads at the greatest risk of malignancy are both dysgenetic and intra-abdominal. The streak gonad in a patient with MGD, raised male should be removed by laparoscopy in early childhood. Bilateral gonadectomy (for bilateral streak gonads) is done in early childhood for females with gonadal dysgenesis and Y chromosome material, which should be detected by techniques like FISH and QFPCR. In patients with defects of Androgen biosynthesis raised female, gonadectomy is done before puberty. The testes in patients with CAIS and those with PAIS, raised as females, should be removed to prevent malignancy in adulthood. Immunohistochemical markers (IHM) that can serve to identify gonads at risk of developing malignancy include OCT 3/ 4, PLAP, AFP, beta-Catenin and CD 117. Early removal at the time of diagnosis (along with estrogen replacement therapy) also takes care of the associated hernia, psychological problems associated with the retained testes and risk of malignancy. Parental choice allows deferment until adolescence, in view of the fact that earliest reported malignancy in CAIS is at 14 years of age. A scrotal testis in gonadal dysgenesis is at risk of malignancy. Current recommendations are surveillance with testicular biopsy at puberty to detect premalignant lesions, which if detected, is treated with local low-dose radiotherapy (with preliminary sperm banking). Also, patients with bilateral ovotestes are potentially fertile from the functioning ovarian tissue. Separation of ovarian and testicular tissue, though challenging, is preferably done early in life [ 19 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 ].

Hormonal therapy/sex steroid replacement

Hormonal induction at puberty in hypogonadism should attempt to replicate normal pubertal maturation to induce secondary sexual characteristics, pubertal growth spurt, optimal bone mineral accumulation together with psychosocial support for psychosexual maturation. Treatment is initiated at low doses and progressively increased. Testosterone supplementation in males (initiated at bone age of 12 years) and estrogen supplementation in females (initiated at bone age of 11 years) is given accordingly for established hypogonadism. In males, exogenous testosterone is generally given till about 21 years, while the same in females is variable. Also, in females a progestin is added after breakthrough bleeding occurs, or within 1–2 years of continuous estrogen. No evidence of benefit exists for addition of cyclical progesterone in females without uterus [ 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 ].

The advances in molecular diagnosis of DSD

The advent of advanced tools for genetic diagnosis has enabled specific diagnosis to be made by molecular studies. WES and WGS represent evolving translational research that help to identify novel genetic causes of DSD. The techniques for identification of novel genetic factors in DSD have evolved from the use of CGH and custom array sequencing to the use of next generation sequencing (NGS) which mainly includes polymerase-based and ligase-based techniques. The importance of molecular diagnosis in DSD lies in the guidance of management in relation to possible gender development, assessment of adrenal and gonadal function, evaluation of the risk of gonadal malignancy, assessment of the risk of familial recurrence, and prediction of possible morbidities and long-term outcome. Hence, the advances in molecular diagnosis of DSD constitute a rapidly evolving frontier in the understanding and therapy of DSD.

The ethical dimension in DSD

The predominant ethical considerations in management of DSD are twofold. Firstly, when the components of biological sex (the sexual profile of genome, gonads, phenotype, endocrine and neurological status) align strongly, prediction of gender identity and recommendations for sex assignment can be made accordingly. The more discordant the determinants of biological sex, more variation in subsequent components of psychosexual development. Secondly, irreversible anatomic and physiologic effects of surgical assignment of sex have to be avoided, especially when the components of biological sex do not strongly align. The objective in such situations should be to delay such treatment till the appropriate age [ 24 , 25 , 26 ].

The arguments favoring recognition of DSD as an alternate gender, with delayed sex assignment and deferred surgical therapy has gained ground over the past decades, highlighted by certain judicial interventions across the globe. In this regard, it has to be emphasized that a transgender state, without incongruity of biological sex, has to be clearly distinguished from a DSD. Though differences in psychosexual development can occur in DSD, the vast majority of clinically diagnosed DSD (CAH, MGD, 46 XY DSD) have the anatomic and physiological consequences of altered components of biological sex. The issues in these subjects are not only confined to the genitalia, but also include problems that can include life-threatening cortisol deficiency, features of hypogonadism and urogenital sinus, and even the risk of gonadal malignancy. The early identification and correction of each issue is vital, and the best available window for the same is limited and usually, early in life. It is some of the less frequently encountered types of DSD (ovotesticular DSD, 17-BHSD deficiency, PAIS) that invariably require a more complex decision-making process. The diagnostic and therapeutic approach in the majority of clinically encountered DSD requires a structured scientific approach, with due consideration of the intricacies of psychosexual development.

The optimal management of different types of DSD in the present era requires the following considerations: (1) establishment of a precise diagnosis, employing the advances in genetic testing and endocrine evaluation. (2) A multidisciplinary team is required for the diagnosis, evaluation, gender assignment and follow-up of these children, and during their transition to adulthood. (3) Deeper understanding of the issues in psychosexual development in DSD is vital for therapy. (4) The patients and their families should be an integral part of the decision-making process. (5) Recommendations for gender assignment should be based upon the specific outcome data. (6) The relative rarity of DSD should prompt constitution of DSD registers, to record and share information, on national/international basis. (7) The formation of peer support groups is equally important. The recognition that each subject with DSD is unique and requires individualized therapy remains the most paramount.

Availability of data and materials

Available on request.

Abbreviations

Disorders of sexual differentiation

- Congenital adrenal hyperplasia

Complete androgen insensitivity syndrome

Partial androgen insensitivity syndrome

Follicular stimulating hormone

Leutinizing hormone

Human chorionic gonadotropin

Fluorescence in situ hybridization

Quantitative fluorescence polymerase chain reaction

Comparative genomic hybridization

Multiplex ligand-dependent probe amplification

Kim SS, Kolon TF. Hormonal abnormalities leading to disorders of sexual development. Expert Rev Endocrinol Metab. 2009;4:161–72.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Hiort O, Birinbaun W, Marshall L, Wunsch L, Werner R, Schroder T, et al. Management of disorders of sex development. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2014;10:520–9.

Article Google Scholar

Jost A. A new look at the mechanism controlling sex differentiation in mammals. Johns Hopkins Med J. 1972;130:38–53.

CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Achermann JC, Hughes IA. Disorders of sex development. In: Kronenberg HM, Melmed S, Polonsky KS, Larsen PR, editors. Williams textbook of endocrinology. 11th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier Saunders; 2008.

Google Scholar

Migeon CJ, Wisniewski AB. Human sex differentiation and its abnormalities. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2003;17:1–18.

Pasterski V. Disorders of sex development and atypical sex differentiation. In: Rowland DL, Incrocci L, editors. Handbook of sexual and gender identity disorders. Hoboken: Wiley; 2008. p. 354–74.

Money J, Hampson JG, Hampson JL. An examination of some basic sexual concepts: the evidence of human hermaphroditism. Bull Johns Hopkins Hosp. 1955;97:301–19.

Gooren L. The endocrinology of sexual behavior and gender identity. In: Jameson L, de Groot LJ, editors. Endocrinology—adult and pediatric, 6th edn. Philadelphia: Elsevier Saunders; 2010.

Swaab DF. Sexual differentiation of the brain and behavior. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;21:431–44.

Meyer-Bahlburg HF. Sex steroids and variants of gender identity. Endocrinol Metab Clin N Am. 2013;42:435–52.

Money J. The concept of gender identity disorder in childhood and adolescence after 39 years. J Sex Marital Ther. 1994;20:163–77.

Zucker KJ. Intersexuality and gender identity differentiation. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2002;15:3–13.

Hughes IA. Disorders of sex development: a new definition and classification. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metabol. 2008;22:119–34.

Houk CP, Lee PA. Approach to assigning gender in 46, xx congenital adrenal hyperplasia with male external genitalia: replacing dogmatism with pragmatism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95:4501–8.

Bao AM, Swaab DF. Sexual differentiation of the human brain: relation to gender identity, sexual orientation and neuropsychiatric disorders. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2011;32:214–26.

Fisher AD. Disorders of sex development. In: Kirana PS, Tripodi F, Reisman Y, Porst H, editors. The EFS and ESSM syllabus of clinical sexology. Amsterdam: Medix publishers; 2013.

Hughes IA, Houk C, Ahmed SF, Lee PA, LWPES Consensus Group; ESPE Consensus Group. Consensus statement on management of intersex disorders. Arch Dis Child. 2006;91:554–63.

Guerrero-Fernández J, Azcona San Julián C, Barreiro Conde J, de la Vega JA B, Carcavilla Urquí A, Castaño González LA, et al. Guía de actuación en las anomalías de la diferenciación sexual (ADS)/desarrollo sexual diferente (DSD) [Management guidelines for disorders/different sex development (DSD)]. An Pediatr (Barc). 2018;89(5):315 e1-315.e19.

Houk CP, Hughes IA, Ahmed SF, Lee PA. Summary of consensus statement on intersex disorders and their management. International Intersex Consensus Conference. Pediatrics. 2006;118:753–7.

van der Zwan YG, Callens N, van Kuppenveld J, Kwak K, Drop SL, Kortmann B, et al. Long-term outcomes in males with disorders of sex development. J Urol. 2013;190:1038–42.

Warne G, Grover S, Hutson J, Sinclair A, Metcalfe S, Northam F, et al. A long-term outcome study of intersex conditions. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2005;18:555–67.

Fisher AD, Ristori J, Fanni E, Castellini G, Forti G, Maggi M. Gender identity, gender assignment and reassignment in individuals with disorders of sex development: a major of dilemma. J Endocrinol Investig. 2016;39(11):1207–24.

Hughes IA, Houk C, Ahmed SF, Lee PA. Lawson Wilkins PediatricEndocrine society/European society for Paediatric Endocrinol-ogy consensus group. Consensus statement on management ofintersex disorders. J Pediatr Urol. 2006;2:148–62.

Lee PA, Houk CP, Ahmed SF, HugheRs IA. International ConsensusConference on intersex organized by the Lawson Wilkins pediatric Endocrine Society & the European Society for Paediatric Endocrinology. Consensus statement on management of inter-sex disorders International Consensus Conference on Intersex. Pediatrics. 2006;118:e488–500.

Lee PA, Nordenstrom A, Houk CP, Ahmed SF, Auchus R, Baratz A, et al. Global DSD Update Consortium. Global disorders of sex development update since 2006: perceptions approach andcare. Horm Res Paediatr. 2016;85:158–80.

Douglas G, Axelrad ME, Brandt ML, Crabtree E, Dietrich JE, French S, et al. Consensus in guidelines for evaluation of DSD by the Texas Children's Hospital multidisciplinary gender medicine team. Int J Pediatr Endocrinol. 2010;2010:919707.

Download references

Acknowledgements

The sincere guidance and help provided by Dr. K Sivakumar, Professor and Head, Department of Pediatric Surgery, Government Medical College, Thiruvananthapuram, Kerala, is gratefully acknowledged.

No funding has been procured for the study.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Paediatric Surgery, Government Medical College, Thiruvananthapuram, Kerala, 695010, India

Vivek Parameswara Sarma

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

The conceptualization, preparation, and revision of the manuscript have been done by the author, Dr. Vivek Parameswara Sarma. The author read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Vivek Parameswara Sarma .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

Not applicable, as this is a Review article.

Consent for publication

Not applicable. The manuscript is an academic review article without any study of human subjects or any patient data.

Competing interests

The author declares no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Sarma, V.P. A review of the essential concepts in diagnosis, therapy, and gender assignment in disorders of sexual development. Ann Pediatr Surg 18 , 13 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s43159-021-00149-w

Download citation

Received : 22 July 2021

Accepted : 13 November 2021

Published : 09 February 2022

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s43159-021-00149-w

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Disorders of sexual development

- Ambiguous genitalia

- Gonadal dysgenesis

- Psychosexual development

- Gender dysphoria

Study at Cambridge

About the university, research at cambridge.

- Undergraduate courses

- Events and open days

- Fees and finance

- Postgraduate courses

- How to apply

- Postgraduate events

- Fees and funding

- International students

- Continuing education

- Executive and professional education

- Courses in education

- How the University and Colleges work

- Term dates and calendars

- Visiting the University

- Annual reports

- Equality and diversity

- A global university

- Public engagement

- Give to Cambridge

- For Cambridge students

- For our researchers

- Business and enterprise

- Colleges & departments

- Email & phone search

- Museums & collections

- ED&I at Cambridge

- Public Equality Duties & Protected Characteristics

- Gender Reassignment

- Guidance on Gender Reassignment for Staff

Equality, Diversity & Inclusion

- Equality Reports

- ED&I at Cambridge overview

- College Equality Policies

- Combined Equality Scheme

- Equality Impact Assessments

- Equal Opportunities Policy

- Equality, Diversity & Inclusion Committee

- Gender Equality Steering Group ( GESG )

- Public Equality Duties & Protected Characteristics overview

- Gender Reassignment overview

- Guidance on Gender Reassignment for Staff overview

What is gender reassignment

- Protections in law

- Medical or surgical procedures

- Supporting Staff

- Information records and privacy

- Access to facilities

- Bullying and harassment

- Sources of information and guidance

- Transition support checklist

- Marriage and Civil Partnership

- Pregnancy and Maternity

- Religion or Belief

- Sexual Orientation overview

- Research Resources

- Local Support Groups

- Resources for Managers

- LGB&T Glossary

- Direct Discrimination

- Indirect Discrimination

- Racial harassment

- Victimisation

- Perceptive Discrimination

- Associative Discrimination

- Third-Party Harassment

- Positive Action

- Initiatives overview

- Academic Career Pathways CV Scheme

- Being LGBTQ+ in Cambridge: A review of the experiences and support of staff at the University of Cambridge

- Faith and Belief in Practice overview

- Facilities for Reflection or Prayer

- Guidance on Religion or Belief for Staff 2013

- College Chaplaincies

- Overview of Buddhism

- Overview of Christianity

- Overview of Hinduism

- Overview of Islam

- Overview of Judaism

- Overview of Sikhism

- Directory of Faith and Belief Communities in Cambridge overview

- Church of England

- United Reformed Church and Church of Scotland

- Festival of Wellbeing

- George Bridgetower Essay Prize

- Returning Carers Fund

- Supporting Parents and Carers @ Cambridge

- The Meaning of Success

- University Diversity Fund

- UDF Successful Projects

- WiSETI overview

- Cake and Careers

- WiSETI Activities overview

- WiSETI/Schlumberger Annual Lectures overview

- Past Lectures

- Events overview

- Recorded Events

- Equality Charters overview

- Athena Swan at Cambridge

- Race Equality Charter

- Training overview

- Equality & Diversity Online Training

- Understanding Unconscious / Implicit Bias

- Networks overview

- Disabled Staff Network

- LGBTQ+ Network overview

- Advice and Support

- Promoting Respect and Dignity

- Resources & Links

- Staff Development and Benefits

- REN: Race Equality Network

- Supporting Parents and Carers @ Cambridge Network

- Women's Staff Network overview

- Support, Information and Local Women's Organisations

- Personal Development

- Advice, Help and Support

- Release Time for Staff Diversity Networks overview

- Information for staff members

- For Managers

- Resources overview

- Race Equality Week 2024 : 5th - 11th February

- COVID - Inclusion Resources

- Equality, Diversity & Inclusion

- ED&I at Cambridge

- Public Equality Duties & Protected Characteristics

A decision to undertake gender reassignment is made when an individual feels that his or her gender at birth does not match their gender identity. This is called ‘gender dysphoria’ and is a recognised medical condition.

Gender reassignment refers to individuals, whether staff, who either:

- Have undergone, intend to undergo or are currently undergoing gender reassignment (medical and surgical treatment to alter the body).

- Do not intend to undergo medical treatment but wish to live permanently in a different gender from their gender at birth.

‘Transition’ refers to the process and/or the period of time during which gender reassignment occurs (with or without medical intervention).

Not all people who undertake gender reassignment decide to undergo medical or surgical treatment to alter the body. However, some do and this process may take several years. Additionally, there is a process by which a person can obtain a Gender Recognition Certificate , which changes their legal gender.

People who have undertaken gender reassignment are sometimes referred to as Transgender or Trans (see glossary ).

Transgender and sexual orientation

It should be noted that sexual orientation and transgender are not inter-related. It is incorrect to assume that someone who undertakes gender reassignment is lesbian or gay or that his or her sexual orientation will change after gender reassignment. However, historically the campaigns advocating equality for both transgender and lesbian, gay and bisexual communities have often been associated with each other. As a result, the University's staff and student support networks have established diversity networks that include both Sexual Orientation and Transgender groups.

- 20 Jun Women's Staff Network Event

View all events

© 2024 University of Cambridge

- Contact the University

- Accessibility

- Freedom of information

- Privacy policy and cookies

- Statement on Modern Slavery

- Terms and conditions

- University A-Z

- Undergraduate

- Postgraduate

- Research news

- About research at Cambridge

- Spotlight on...

- Table of Contents

- Random Entry

- Chronological

- Editorial Information

- About the SEP

- Editorial Board

- How to Cite the SEP

- Special Characters

- Advanced Tools

- Support the SEP

- PDFs for SEP Friends

- Make a Donation

- SEPIA for Libraries

- Entry Contents

Bibliography

Academic tools.

- Friends PDF Preview

- Author and Citation Info

- Back to Top

Feminist Perspectives on Sex and Gender

Feminism is said to be the movement to end women’s oppression (hooks 2000, 26). One possible way to understand ‘woman’ in this claim is to take it as a sex term: ‘woman’ picks out human females and being a human female depends on various biological and anatomical features (like genitalia). Historically many feminists have understood ‘woman’ differently: not as a sex term, but as a gender term that depends on social and cultural factors (like social position). In so doing, they distinguished sex (being female or male) from gender (being a woman or a man), although most ordinary language users appear to treat the two interchangeably. In feminist philosophy, this distinction has generated a lively debate. Central questions include: What does it mean for gender to be distinct from sex, if anything at all? How should we understand the claim that gender depends on social and/or cultural factors? What does it mean to be gendered woman, man, or genderqueer? This entry outlines and discusses distinctly feminist debates on sex and gender considering both historical and more contemporary positions.

1.1 Biological determinism

1.2 gender terminology, 2.1 gender socialisation, 2.2 gender as feminine and masculine personality, 2.3 gender as feminine and masculine sexuality, 3.1.1 particularity argument, 3.1.2 normativity argument, 3.2 is sex classification solely a matter of biology, 3.3 are sex and gender distinct, 3.4 is the sex/gender distinction useful, 4.1.1 gendered social series, 4.1.2 resemblance nominalism, 4.2.1 social subordination and gender, 4.2.2 gender uniessentialism, 4.2.3 gender as positionality, 5. beyond the binary, 6. conclusion, other internet resources, related entries, 1. the sex/gender distinction..

The terms ‘sex’ and ‘gender’ mean different things to different feminist theorists and neither are easy or straightforward to characterise. Sketching out some feminist history of the terms provides a helpful starting point.

Most people ordinarily seem to think that sex and gender are coextensive: women are human females, men are human males. Many feminists have historically disagreed and have endorsed the sex/ gender distinction. Provisionally: ‘sex’ denotes human females and males depending on biological features (chromosomes, sex organs, hormones and other physical features); ‘gender’ denotes women and men depending on social factors (social role, position, behaviour or identity). The main feminist motivation for making this distinction was to counter biological determinism or the view that biology is destiny.