The Hardest Part of Research

January 25, 2013 by library | 0 comments

Getting Started

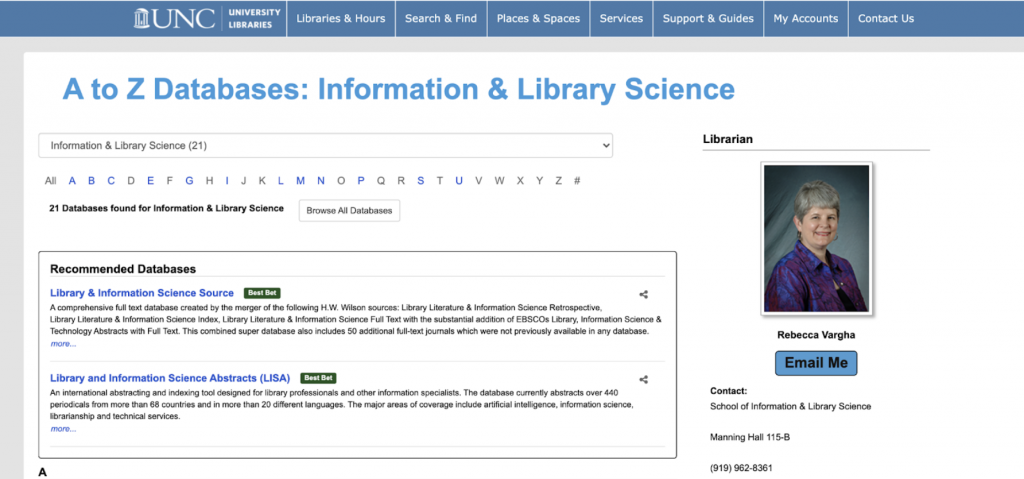

In the fall, we asked you to tell us what the hardest part of research is for you. For many of you, it’s getting started (“knowing where to begin,” “starting it,” “the beginning”). If part of the difficulty is that you know very little about your topic, check out CredoReference . This great database contains encyclopedia, dictionary, and handbook articles on many topics. These should give you an overview of your topic and some ideas on how to break it down. You can find CredoReference in the Databases A-Z list on the library’s homepage.

Avoiding Distractions

Individual Study Room

If you are easily distracted (for example, this person: “Continuing to stay interested when there are shiny objects and funny noises in the same room as you because suddenly tinkling glasses and butterflies and candy and”), consider one of the library’s individual study rooms . These locked rooms have desk space and outlets. They are a great place to hide away from many of life’s distractions and get some work done.

Locating Information

Many of you also mentioned struggling with locating information. This is definitely an area that librarians can help! If you have a hard time with “looking for articles” or “navigating research terms to find the best results,” you should check out our Basic Databases Workshops :

- January 29 (Tuesday): 11:30am to 12:20

- February 4 (Monday): 5:30pm to 6:20

Workshop Description : Need to find articles for a paper? Can’t remember how to use the library databases? This workshop offers an introduction to online database searching strategies to help you find the resources you need.

Evaluating your Sources

For those of you struggling with “Being critical about your sources/citations” and “Sorting the wheat from the chaff,” consider attending our Evaluating Resources Workshops :

- February 12 (Tuesday): 11:30am to 12:20

- February 25 (Monday): 2:00pm to 2:50

Workshop Description : Not sure if you are selecting the best resources for your assignment? Attend this workshop to learn more about how to evaluate the resources you find – books, journals, websites, and everything else.

Organizing your Sources

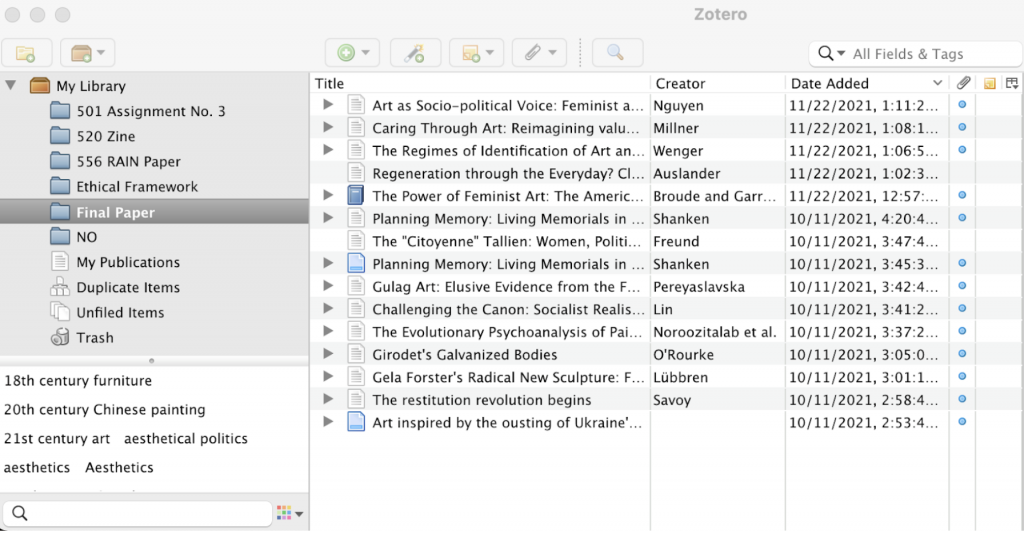

At least one of you mentioned that “keeping everything organized” was a frustration. There are many ways to organize your research. If you are interested in some tech tools that can help you, you may want to learn more about Mendeley or Zotero at our workshops:

- February 5 (Tuesday): 11:30am to 12:20

- February 6 (Wednesday): 5:15pm to 6:05

- February 14 (Thursday): 11:30am to 12:20

- February 19 (Tuesday): 5:15pm to 6:05

Workshop Description : Working on research and have PDFs saved all over the place? Do you keep misplacing the articles you’ve found? There’s an easier way to keep track! Attend these workshops to learn more about Mendeley and/or Zotero, tools that you can use both to keep all your research in one location and to create citations.

Unable to attend a library workshop or want individual assistance? Ask a librarian!

- Stop by the Reference Desk

- Call us: 412-365-1670

- Email us: [email protected]

- IM us from our website: library.chatham.edu

Procrastination

- Friday, January 25: Time Management in College , 11:30am, Chatham Eastside: Main Conference Room

- Wednesday, January 30: Time Management in College , 11:30am, Davis Room: JKM Library

- Friday, February 22: Procrastination , 11:30am, Davis Room: JKM Library

- Monday, February 25: Procrastination , 11:30am, Chatham Eastside: Main Conference Room

Writing the Paper

The PACE Center also provides writing help for those of you who struggle with “writing up the paper” and “editing.”

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Required fields are marked * .

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

June 19, 2013

What's So Hard about Research?

By Jody Passanisi and Shara Peters

This article was published in Scientific American’s former blog network and reflects the views of the author, not necessarily those of Scientific American

We are told that the students that we teach are “digital natives.” This term implies that from the time they were born, technology has played such a large part in students’ lives that they know no other way. Also, it has been noted that digital natives have an aptitude for technology that is significantly different from the older generations (who have been dubbed “digital immigrants”); the joke goes that if you give a digital native and a digital immigrant a new digital camera, the native will be taking pictures before the immigrant has finished reading page two of the manual. The assumption is that this new generation is simply better than us at technology.

However, as we wrote about in another article for Scientific American , just because students are digital natives, does not mean that they have skills to figure out all technology, or to use technology in a purposeful way. We noticed that, though these digital natives have the world of information at their fingertips, for some reason they are often unable to take basic problem-solving skills and apply them to simple online research. They had no problem figuring out how to work the newest update to Facebook, but when asked to find out any information that required the smallest amount of critical thinking, students were hampered. The best example we have of this is when we asked students what the most important causes of the Revolutionary War were—we heard a student ask Siri: “What are the most important causes of the Revolutionary War?” When Siri did not know the answer, the student said, “I don’t know, I can’t find it.”

Students can find out basic names, dates, and facts through online research. If we ask them what year the Declaration of Independence was signed, they will Google that exact question, and most of the time, produce the right answer. But when asked to research a question that does not have one “right” answer, the room quickly dissolves into a chorus of “I don’t get it” and “I need help” and “I can’t find it.”

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing . By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

In this article we will attempt to answer this question that we have posed and discussed often here at Scientific American:

What about online research is challenging to students?

Through observation of our students, we have come up with five hypotheses as to why this may be:

· Students today are accustomed to instant gratification, and therefore can be overwhelmed by tasks that require time-consuming research.

There are very few things in life that our students have to wait for today. Information they need to know is posted instantly online, they can connect with their friends through social media without needing to wait for school the next day, and Googling a question will give them a quick answer to any fact they want to know. However, research isn’t actually easy--in fact, it’s quite deceptive how the Internet makes it seem easy. In reality, research requires students to read, interpret, and analyze new information, reshape their research question, and start again. This kind of sustained focus on a challenging task is very hard for most students to hold. Here is an exchange that exemplifies this facet of the issue:

Student: “I can’t find anything about the buildings of the South during Reconstruction.”

Teacher: “Ok, show me what sites you’ve used.”

(Student pulls up an article from the History Channel)

Teacher: “Well, I see a good starting place right here. It says that much of the South was destroyed during Sherman’s March to the Sea during the Civil War. Why don’t you find out what areas his march destroyed, and then look up those cities to see what kind of destruction they faced?”

Student: (while pouting and walking back to his desk) “But that’s going to take forever !”

What the student meant to tell the teacher was, “ I can’t find anything easily about the buildings of the South during Reconstruction.” It isn’t true that, as a whole, these students have a difficult time with sustained attention. They do not stop researching and begin another activity because they got distracted; in our experience, they are more likely to spin themselves in circles making no progress for an entire class period because they do not want to go through a cognitive process that will take “forever.”

· When researching online, students unsuccessfully scan pages of text as opposed to reading those pages of text for comprehension. Therefore, they cannot tell whether or not the source they are looking at is applicable to their research question.

There are many techniques one can use to quickly locate information on an Internet page. For example, CTRL + F will bring up a “find” tool that will allow you to highlight all instances of a particular word or phrase on a page. Students use this tool quite frequently; when one student needed to find out what President Polk thought about U.S. expansion, she found an article about expansion, hit CTRL + F, and searched for “Polk.” All of the results on the page linked Polk to legislation that was passed, and land that was acquired during his term, but nowhere on the page could she find a sentence that said that President Polk thought that expansion was ________. Instead of reading the article and using inductive reasoning to figure out that President Polk was probably in favor of expansion, she told us that she couldn’t find the answer.

There are a few factors that we believe are at work here. It is faster to CRTL + F a keyword than it is to read an article, so perhaps some of hypothesis number 1 is at work, here: students want to take the fastest and quickest route. However, there are also issues of monitoring reading comprehension. The problem is not necessarily that the language of the article was too sophisticated for this student; the real problem is that she never stopped to ask herself the question, “Do I understand what this means?”

· When students are given a research prompt by their teacher, students often do not care enough about the topic to really persevere. Therefore, when they find that answers are not immediately apparent, they do not have the motivation necessary to fuel their sustained attention.

We have noticed that when students look up information we tell them to look up, they ask us many questions during a class period. Most are interested in making sure they have the “right answers”, and checking that their assignment is “long enough”. When students conduct research about a topic they have interest in, they have a much stronger sense of purpose. While some do still ask us questions in which they seek our approval, it is more often for approval about their thoughts pertaining to content than for approval of the length of their assignment. They seem to take more ownership of the material, and think about it on a higher level.

· Because there is so much information online, and not all of it is credible, Internet search results can be overwhelming to students. Therefore, the amount of information paralyzes rather than empowers students.

It seems counter-intuitive that a student could pull up 500,000 search results and still tell her teacher that she can’t find anything (just like flipping through a billion channels on cable, but finding that nothing is on)-- but students do often feel that way. The best way to illustrate this is to describe the difference in student responses when they were researching using a search engine other than Google.

Dulcinea Media came up with a search engine designed for students called SweetSearch . It works similarly to Google, in that there is a database of files that one can search by typing keywords into a search bar. What is different about SweetSearch is that the database only contains 30,000 documents, all of which have been previously vetted for academic reliability. For a particular project, the only Internet search engine we allowed the students to use was SweetSearch.

When they researched in class using Google, five to ten students per class period would say they were unable to find what they needed. When they researched in class using SweetSearch, there was not a single student who told us that they could not find any information about their topic. So whether students liked using SweetSearch or not, it is clear that it helped them be more successful when conducting their research.

· Developmentally, middle school students are just beginning to be able to think critically, but they seem programmed to look for “the” answer, and do not have a strong sense of self-efficacy when presented with open-ended questions.

Some of our unit assessments are structured in the style of Project Based Learning where students can present their findings in any form, as long as it answers the inquiry-based prompt. Many students were very uncomfortable with the idea that they would be making the decision about what form their project will take, and continually tried to get a stamp of approval. Questions like, “Do you think it will be okay if we make a movie?” Or “Will it be good if we make a poster?” were all answered with some version of, “It doesn’t matter what we think. What do you think?” We could see the frustration in their faces when they did not get the answer they wanted, but our goal here was for them to realize that their opinions were the ones that mattered.

Students also asked for their teachers’ opinions about their research findings. Students felt unsure about their authority, and wanted us to tell them that they had found the right answer. It takes the responsibility off of them; however, we wanted the students to take ownership of the information, and unless they were historically inaccurate in their findings (which almost never happened), we answered all of these questions in the same manner as the questions about their projects: “It doesn’t matter what I think. What do you think?”

Now that we know students struggle with research, now that we’ve discussed why that might be so, what steps can we take to help improve the situation? The next frontier for us will be to design curricular interventions that help students overcome some of these challenges they face, and to provide opportunities--like our Project Based Learning research unit assessment-- for students to research in more productive ways. SweetSearch and critical thinking are just the beginning. This question of research will only be more acute in the coming years as information in this age is becoming even more accessible and available to students. It is our job as their teachers to help students understand and be able to use this information that they discover.

Research Paper: A step-by-step guide: 9. Writing Your Research Paper

- 1. Getting Started

- 2. Topic Ideas

- 3. Thesis Statement & Outline

- 4. Appropriate Sources

- 5. Search Techniques

- 6. Taking Notes & Documenting Sources

- 7. Evaluating Sources

- 8. Citations & Plagiarism

- 9. Writing Your Research Paper

From draft to finish

Writing your paper.

Often the actual writing is the hardest part of a research paper. How do you put all of your ideas together in a cohesive and understandable fashion? Hopefully this guide has helped lead you to this point, but if you need help, go back and review the steps you may need more help with.

You should now have the following items that will help you start your paper:

- Notes and a list of references from valid and reliable sources. When you create your list of works cited, you will only need to include the citations for the sources you refer to in your paper.

- An outline to guide you through your paper with main points and supporting evidence.

- A start on a thesis statement. You may find that your original idea isn’t supported by the research, or your thesis may evolve and change as you write. Revisiting your thesis throughout the research process is normal and a good idea.

Reviewing what makes a good research paper will help keep you on track as you write your paper. Here are the main points from step one of this guide:

- A strong and focused thesis statement

- Logically organized arguments and main points

- Each main point is supported by persuasive facts and examples

- Opposing viewpoints are included and rebutted, showing why the author's argument is more valid

- The paper shows the author's understanding of the topic and the material

- The work is original, not plagiarized

- Every source is correctly documented and credited in a recognized citation style

- The paper is written in clear language in a style suitable for college research

Finishing Touches and Final Draft First drafts can be messy and that is ok. Revising and editing your paper may take as much time, or longer, than writing the first draft. Here are some tips to help you through the process.

- Take a break. Hopefully you gave yourself plenty of time to work on your paper and are not rushed to finish. Taking a break will clear your head, focusing your attention on sections of your paper that might need revision.

- Double check the facts and numbers. Add supporting arguments as needed.

- Check for grammatical and spelling errors. Omit needless words and repetitious ideas.

- Check your citations (in-text citation and reference list) and paper format (header, page number, margins, etc.) to make sure sources are properly cited and the format is correct.

- Ask someone to read over your paper as they may be able to spot the mistakes you overlooked.

- Another way to check for mistakes, omissions, or awkward word construction is to read your paper out loud to yourself.

Tips to Help You Start Writing

To see some quick tips to help you write your paper, watch the following short video:

Need More Help?

Get your paper and citations checked at the Center for Academic Success (CAS).

- CAS Tutoring

- NetTutor You can access 24/7 online tutoring through Canvas.

- << Previous: 8. Citations & Plagiarism

- Last Updated: Apr 18, 2023 12:12 PM

- URL: https://butte.libguides.com/ResearchPaper

Chapter 4 Research Papers: Discussion, Conclusions, Review Papers

- First Online: 17 July 2020

Cite this chapter

- Adrian Wallwork 3 &

- Anna Southern 3

Part of the book series: English for Academic Research ((EAR))

3209 Accesses

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

English for Academics SAS, Pisa, Italy

Adrian Wallwork & Anna Southern

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2020 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Wallwork, A., Southern, A. (2020). Chapter 4 Research Papers: Discussion, Conclusions, Review Papers. In: 100 Tips to Avoid Mistakes in Academic Writing and Presenting. English for Academic Research. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-44214-9_4

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-44214-9_4

Published : 17 July 2020

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-030-44213-2

Online ISBN : 978-3-030-44214-9

eBook Packages : Social Sciences Social Sciences (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

✨ Enrol by 15 May to get access to our Jumpstart Your Summer Writing events at no additional cost! 💰 ✨

How (Not) to Write the Discussion Section of a Research Paper

What the Discussion section of a scientific paper should and shouldn’t contain.

The Discussion section might well be the hardest part of a paper to write. Yet, so useful! In a great Discussion section, the authors tie the different findings of the paper together, analyse them in the context of existing literature, offer speculations, suggest further research and highlight the study’s significance and possible impact.

I love reading well written Discussions sections – it’s not uncommon that I only really understand the author’s contributions after I’ve read this section, especially when the research is somewhat outside my field of expertise. At the same time, I rarely come across well written discussions of research studies.

Why is that? I think a major factor is that the discussion is the least rigid part of a paper, so many authors are simply at a loss as to what to write. Another reason might be that the authors understand their results and what they mean so well that they cannot imagine what kind of discussion the reader would need in order to make sense out of the findings. It often is hard to take a step back to look at the bigger picture.

The Discussion section in a research paper: The 4 most common mistakes

Therefore, I’ve gathered the four most common mistakes I see scientists make in Discussion sections and offer some advice on how to improve them:

1. Providing paragraphs of background information

Authors who do this probably intend to put their results into context. However, the discussion section is neither the right place to reiterate background info nor to mention it for the first time. The correct place for contextualising your study is the introduction section.

This doesn’t mean that you shouldn’t reference other studies in your discussion. But instead of writing a big block containing only background information, I recommend to refer to other studies in connection with the discussion of your findings. It’s great to mention, for example, whether and why your results and hypotheses agree or disagree with the findings and hypotheses of other studies.

2. Not restating the problem you are solving

Your readers will likely either skip right to your discussion section (I often do this when I’m researching for stories I’m writing about), or they just have just read your results section. In either case, it makes sense to quickly restate why you have researched this topic. For those who skipped your “Introduction” and “Results” sections, reading a quick motivation for your study helps them to put your study into context. Chronological readers will have just deep-dived into the nitty-gritty of your results. By restating the problem you are solving, you help them to zoom out again and remind them of the “why”.

3. Describing the purpose and result of each experiment

Or in other words, don’t confuse what belongs in the “Results” and what in the “Discussion” section. So, skip the “First, we… Then, it was… In order to, we next…”. While I absolutely recommend to state the purpose and result of each experiment, hence guiding your reader through your study’s narrative, it belongs in the “Results” section. Or put differently, once the reader arrives at the discussion section, your story line should be clear. If you compare the story in a scientific paper to a drama, your discussion corresponds to the “Resolution” part of a story. The reader wants to know how things have changed for the characters of your story (aka your model system or study subject) after you obtained your results, how your study has changed the state of the art, or what implications your findings have for an application.

That said, stating the main conclusions of your results in the discussion section is absolutely recommended. But use the remaining space to actually discuss your findings.

4. Too general implication statements

Every discussion section should contain some sentences that outline the significance and importance of your findings. To be fair, most papers contain at least one sentence about this. However, all too often these statements are very general and broad. It’s okay to speculate here about possible applications or a likely impact your findings might have. But try to paint a more precise picture than just saying that your novel material “could be used in nanotechnology applications”. As a reader, I want to know what applications it will be good for specifically? And how exactly will it benefit those applications?

These are the four most common mistakes I see people make in their discussion section. At last, a little word of warning. Sometimes authors prefer to write a combined “Results and Discussion” section. While this can be appropriate in some cases, be careful to not skip discussing your results when doing this and offer an analysis beyond presenting and interpreting your findings.

Procrastinating on your writing? Not feeling like you’re effective at communicating clearly and/or getting desk-rejected a lot?

In this free online training for science researchers, Dr Anna Clemens introduces you to her step-by-step system to write clear & concise papers for your target journals in a timely manner.

Share article

© Copyright 2018-2024 by Anna Clemens. All Rights Reserved.

Photography by Alice Dix

The Secret(s) to Getting Through Long Papers

By Sophie, a Writing Center Coach

It’s the beginning of the semester—meaning, as a graduate student, it’s time for me to get back into the groove of planning and writing long papers. For me, the hardest part of approaching a paper is coming up with a topic that will stay interesting to me throughout the research and writing process. A good example of this is from the end of last semester, when I found myself dreading the final paper for my archives class. We covered so many interesting topics in the class, it was hard to decide which one to choose.

In my experience, a bad topic can make the writing process feel infinitely longer and more stressful. As I thought about my archives paper, I worried about finding something that I could focus on for 12 pages. So many of the topics in my class felt interwoven, and I was afraid it would be hard to pick out one thread. If I try to start a long paper without planning, I’ll end up staring at the same sentence or paragraph for hours, trying to figure out what I could possibly say next.

So, when I finally had to commit to a topic, I decided to break down the process into a few fun steps. Dividing it up helped take away some of my worries and made the process easier because I only had to do one step at a time. Here’s how I got started:

1) Create a real brainstorming session

First, I decided to meet up with a few of my friends who were also in the class. We went to a coffee shop we all like, and we brought our notes and readings from the class. None of us had a concrete idea about what to write; we just wanted to throw some possibilities out to see how other people would react to them.

We started by talking about some of the things we found funny or interesting in previous class discussions. As we talked, we found natural points of disagreement and interest. I took notes about points that stuck out to me. At the end of the conversation, I had a document full of questions and arguments that I wanted to explore further.

My friends also thought of topics, but they arrived at their ideas in different ways. One of my friends kept coming back to a short paper she had already written, and by talking about it, she discovered that she had much more to say. Another friend talked about something that he felt was conspicuously missing from our class discussions, so he decided that this paper would be a good opportunity to learn more.

All three of us came out of the session with inspiration and initial feedback. This step reminded me of the value of talking through my ideas, especially since my peers could push me to think more deeply about particular questions. Plus, connecting with my classmates through discussion helped me get excited about writing.

Alternatively, I know that, for some people, meeting with friends isn’t always effective; there are also other ways to brainstorm. Sometimes, it helps to talk to someone who doesn’t know about the class or topic—like a Writing Center coach ! For others, the note-taking part could be like having a conversation with yourself, which might be all you need. The Writing and Learning Centers also have some great tools for brainstorming if you prefer to work independently.

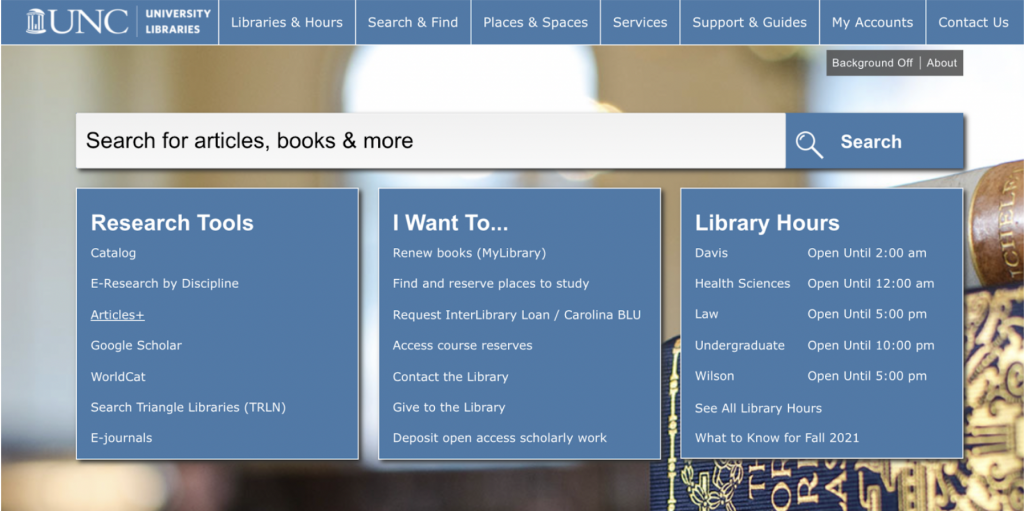

2) Conduct some initial research

Once I had the beginnings of an idea, I decided to look for sources that could help me narrow my topic. The first place I go to find scholarly articles is the UNC Libraries’ page with “Resource Tools.” At this phase, I like to do keyword searches with Articles+. When you open the advanced search options, you can limit your results to be really specific by choosing a discipline, language, date the material was published, and whether the source needs to be scholarly/peer reviewed. In this case, I used “AND” to limit my results to articles with all of my desired keywords, like: “Sexual material” AND “Archives.” There’s another great article that explains the logic behind this kind of search, which uses Boolean logic.

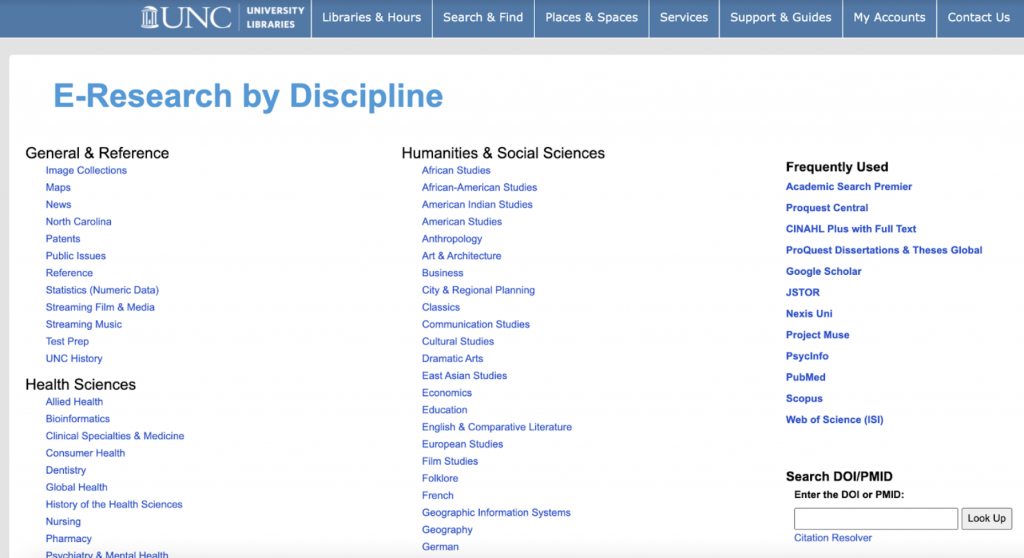

After I’ve combed through relevant results for one search, I’ll usually adjust my keywords to see if anything new pops up. I’ll also see if the best articles (the ones that feel most related to my topic) have been cited by anyone else and whether those articles have something to offer me. I also repeat this process with Google Scholar and with the “E-research by Discipline” option, which will lead me to specific databases for my field.

In this case, I used the Information and Library Science option, which took me to the best databases for journals in my discipline. Searching within a discipline allows me to think more carefully about my keywords; I might not have to include “archives,” or “libraries,” for example, because many of the articles are already about archives.

As I’m going along, I like to save any articles that I find in Zotero, a citation manager that I downloaded from the library’s website. Within Zotero, I make a folder for the assignment (“Final Paper”), and it automatically saves all the information I need to quickly go back to the article if I need it. (Note: I first learned about using Zotero from a helpful university librarian, so if you’re new to citation managers, it might be helpful to have a librarian give you a tutorial. You can also read another blog article on using Zotero .)

At the end of this process, I usually have a file full of “maybe” sources that I could come back to later. This helps give me an idea of what people have already said about this topic and where I might be able to add to the conversation.

3) Meet with your professor

After I came up with an idea and did some preliminary research, I thought it would be a good idea to check in with my professor during office hours. Since my professor is an expert in the field, I knew she would have a better sense of the context surrounding my research question.

(Note: Sometimes I like to go to office hours before I do any research; getting some expertise at the beginning can make the search process even faster. In this case, my professor encouraged us to find what we could before checking in with her.)

Before the meeting, I read through the abstracts of the sources I had already found in my preliminary research (those were saved in my Zotero library). Based on those, I wrote down some questions that I had about the topic. I met with my professor for about 15 minutes, and in that time, I pitched my question and told her what I had already found. She was able to direct me to some additional books and cases to look at, and I wrote those down to research later.

My professor also encouraged me to post my topic in our class’ Sakai forum. She created a discussion page specifically for final topic ideas so that my other classmates could provide feedback. Often, she said, students with similar topics will find sources that are helpful to each other, so the forum is a good place to share resources. I left the meeting with a strong sense of direction of what I needed to begin the actual writing.

After going through these steps, I felt like I had a good idea of what I wanted to write about and some evidence that could support my argument. Still, because it was such a long paper, I felt like I needed help to get started on the outline and the actual writing process. So, I decided to make a Writing Center Appointment to get my ideas in order and to make a plan for finishing the paper on time. Again, since I’m a person who likes to talk through my ideas, it was helpful to hear another person’s reaction to my topic so far. It also gave me a self-imposed deadline to complete these initial steps.

Breaking down the first few steps of writing my research paper helped me think of it as a list of small tasks to check off instead of one giant, frustrating project. It felt good to accomplish little things that I knew would add up to finishing the whole thing. This process also led me to a topic that really excited and engaged me, so when it was time to do the final step (the actual writing), I was happy to get started.

This blog showcases the perspectives of UNC Chapel Hill community members learning and writing online. If you want to talk to a Writing and Learning Center coach about implementing strategies described in the blog, make an appointment with a writing coach , a peer tutor , or an academic coach today. Have an idea for a blog post about how you are learning and writing remotely? Contact us here .

- Master Your Homework

- Do My Homework

Research Paper Challenges: A Guide to Overcoming Them

As the prevalence of research papers continues to increase in educational institutions, so does the need for guidance on how to effectively manage and overcome related challenges. This article provides an overview of some common obstacles that can be encountered when undertaking a research paper project, along with practical solutions which have proven successful among students. The material is supplemented with current case studies from different academic levels and disciplines as well as tips for maximizing resources available during this process. By analyzing these issues through a comprehensive approach, it is possible to gain an understanding of how best to tackle any given challenge associated with completing a research paper project.

I. Introduction to Research Paper Challenges

Ii. identifying the challenge at hand, iii. common causes of research paper difficulties, iv. developing an effective writing strategy, v. overcoming procrastination and distractions in writing a research paper, vi. making use of available resources for assistance with your project, vii .conclusion: understanding and resolving issues when working on a research paper.

Research papers can be quite intimidating. They require more detailed research, significant amount of time and energy to come up with quality results, and a deep understanding of the subject at hand. For many students, the biggest challenge comes from learning how to effectively navigate these academic hurdles while still producing high-quality work.

- Selecting a Topic – Coming up with an interesting yet relevant topic that will yield meaningful results can be difficult.

- Finding Relevant Sources – It is essential to have reliable sources in order for your paper’s argument to be taken seriously.

For researchers in the current academic climate, identifying an appropriate research challenge can be a daunting task. With each year bringing new theories and discoveries, staying up to date on current scholarly literature is a must for any ambitious scholar looking to break through barriers with their work. Furthermore, being able to recognize where further exploration is needed within the field provides invaluable insight that allows your project stand out from other similar ones.

One of the most important aspects of choosing a research topic lies in its ability to foster innovation while advancing existing knowledge. As such, potential projects should take into account recent publications as well as gaps in literature or areas ripe for additional exploration.

- Establishing what questions are yet unanswered : Brainstorming about topics which still need answers helps ensure that your efforts result in something groundbreaking.

- Research past investigations : Reviewing related studies conducted by previous scholars offers valuable information and inspiration when considering possible directions you might pursue.

Lack of Understanding and Organization The most common causes of difficulty when it comes to writing a research paper are lack of understanding the material and poor organization. Without knowing how to properly organize your thoughts, information, or sources into coherent sections with smooth transitions, you will not be able to produce an effective final product. Also crucial is having a basic understanding on which materials should be consulted for each topic – if you do not have this knowledge then you can easily become overwhelmed by all available sources.

Time Commitment For many researchers time management is also an issue as they often underestimate the amount needed to complete their paper in its entirety. All too often students wait until the last minute hoping that sufficient results can still be achieved under such tight constraints – unfortunately more times than none these papers end up being rushed jobs full of errors due to little planning ahead or dedication in researching topics thoroughly enough prior submitting them.

Focusing Your Ideas

Beginning your research paper can be an overwhelming task. It is important to narrow down and define the scope of your project, choose a topic that interests you, and develop a working thesis statement. You should also consider what types of sources are most suitable for supporting arguments in this particular area or on this subject matter. Gathering materials from reliable sources is essential for crafting an accurate argument.

Organizing Your Research Paper

- Create an outline to ensure that all ideas are logically organized.

- Set aside time each day devoted exclusively to researching and writing

. This allows you to make progress at a steady pace without becoming overwhelmed by deadlines or distractions.

- Developing effective writing strategies such as creating drafts; organizing material into logical sections; revising content; proofreading text for clarity, consistency, accuracy and correctness will help expedite the process significantly.

. A combination of careful planning along with diligent effort towards completing tasks ahead of schedule will provide enough time needed for revisions if required before submission deadlines.

When it comes to writing a research paper, procrastination and distractions can be major hindrances to its completion. Fortunately, there are ways of overcoming them.

- Set Clear Goals:

Establishing achievable goals is essential in keeping on task with your research paper. Set smaller, incremental objectives that you will need to complete throughout the process such as outlining chapters or conducting research interviews. Doing so helps make sure progress continues despite any bumps along the way.

- Manage Your Time Wisely:

Time management plays a key role in beating procrastination and distraction when working on your paper. Structure your day into sections dedicated specifically for researching, drafting and editing without interruption from other activities or tasks like checking email frequently or engaging in social media conversations every few minutes – these are huge time wasters! It’s also important to schedule adequate rest periods during which you can do something completely different than what you’ve been doing while working on the project; this keeps creativity alive during crunch times ahead of deadlines.

Uncovering and Utilizing Research Resources It can be difficult to know where to look for help when it comes to researching a project, especially when working with limited time. Start by consulting your professor or teaching assistant: they will likely have access to resources that may not immediately be available elsewhere. Once you’ve identified potential sources of assistance, such as in the university library’s collections, take some time to familiarize yourself with their offerings. Ask questions about what materials are offered — online databases? physical texts? — and how best make use of them. You may also want consider whether supplemental options exist within your research area; examples include interview transcripts or public opinion polls.

- Finding reliable academic sources

- Using primary and secondary source material appropriately

Being cognizant of these elements is essential if you hope for your project paper’s results and conclusions be taken seriously among colleagues. That being said, the process shouldn’t intimidate you either – practice makes perfect! Asking clarifying questions is always recommended, so don’t hesitate approach knowledgeable people who might aid in providing effective guidance along the way – from professors all the way up through experienced professionals in relevant fields.

Conclusion: Understanding and Resolving Issues When Working on a Research Paper

Issues can arise when working on any research paper. As daunting as this prospect may be, it is important to understand the most common issues in order to effectively manage them. Some of these issues include inadequate understanding of the topic or sources used; inadequate time to conduct research and write up findings; limited access to relevant information resources; difficulties in assessing evidence for reliability or accuracy, etc.

The key is having an organized approach towards resolving such issues. The researcher should start by clearly identifying what aspects need attention – this will help narrow down the scope of action required while tackling problems related with their project. It also helps if they discuss their work openly with colleagues and mentors who can provide insight into possible solutions that might not have occurred otherwise. Furthermore, researchers must stay aware about recent developments related to their subject area which would improve understanding from multiple perspectives thus resulting in improved writing quality overall.

The challenges that accompany the research paper can be intimidating. With this guide, we have sought to provide insight into strategies for overcoming these obstacles and to assist researchers in turning their projects from mere ideas into tangible accomplishments. Through an understanding of what they may encounter while writing a research paper, as well as proactive solutions to address each challenge, authors will find themselves better prepared for any issue along the way. This article provides valuable guidance on how one might successfully overcome all manner of roadblocks during the course of researching and writing a quality piece.

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- NATURE INDEX

- 01 May 2024

Plagiarism in peer-review reports could be the ‘tip of the iceberg’

- Jackson Ryan 0

Jackson Ryan is a freelance science journalist in Sydney, Australia.

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Time pressures and a lack of confidence could be prompting reviewers to plagiarize text in their reports. Credit: Thomas Reimer/Zoonar via Alamy

Mikołaj Piniewski is a researcher to whom PhD students and collaborators turn when they need to revise or refine a manuscript. The hydrologist, at the Warsaw University of Life Sciences, has a keen eye for problems in text — a skill that came in handy last year when he encountered some suspicious writing in peer-review reports of his own paper.

Last May, when Piniewski was reading the peer-review feedback that he and his co-authors had received for a manuscript they’d submitted to an environmental-science journal, alarm bells started ringing in his head. Comments by two of the three reviewers were vague and lacked substance, so Piniewski decided to run a Google search, looking at specific phrases and quotes the reviewers had used.

To his surprise, he found the comments were identical to those that were already available on the Internet, in multiple open-access review reports from publishers such as MDPI and PLOS. “I was speechless,” says Piniewski. The revelation caused him to go back to another manuscript that he had submitted a few months earlier, and dig out the peer-review reports he received for that. He found more plagiarized text. After e-mailing several collaborators, he assembled a team to dig deeper.

Meet this super-spotter of duplicated images in science papers

The team published the results of its investigation in Scientometrics in February 1 , examining dozens of cases of apparent plagiarism in peer-review reports, identifying the use of identical phrases across reports prepared for 19 journals. The team discovered exact quotes duplicated across 50 publications, saying that the findings are just “the tip of the iceberg” when it comes to misconduct in the peer-review system.

Dorothy Bishop, a former neuroscientist at the University of Oxford, UK, who has turned her attention to investigating research misconduct, was “favourably impressed” by the team’s analysis. “I felt the way they approached it was quite useful and might be a guide for other people trying to pin this stuff down,” she says.

Peer review under review

Piniewski and his colleagues conducted three analyses. First, they uploaded five peer-review reports from the two manuscripts that his laboratory had submitted to a rudimentary online plagiarism-detection tool . The reports had 44–100% similarity to previously published online content. Links were provided to the sources in which duplications were found.

The researchers drilled down further. They broke one of the suspicious peer-review reports down to fragments of one to three sentences each and searched for them on Google. In seconds, the search engine returned a number of hits: the exact phrases appeared in 22 open peer-review reports, published between 2021 and 2023.

The final analysis provided the most worrying results. They took a single quote — 43 words long and featuring multiple language errors, including incorrect capitalization — and pasted it into Google. The search revealed that the quote, or variants of it, had been used in 50 peer-review reports.

Predominantly, these reports were from journals published by MDPI, PLOS and Elsevier, and the team found that the amount of duplication increased year-on-year between 2021 and 2023. Whether this is because of an increase in the number of open-access peer-review reports during this time or an indication of a growing problem is unclear — but Piniewski thinks that it could be a little bit of both.

Why would a peer reviewer use plagiarized text in their report? The team says that some might be attempting to save time , whereas others could be motivated by a lack of confidence in their writing ability, for example, if they aren’t fluent in English.

The team notes that there are instances that might not represent misconduct. “A tolerable rephrasing of your own words from a different review? I think that’s fine,” says Piniewski. “But I imagine that most of these cases we found are actually something else.”

The source of the problem

Duplication and manipulation of peer-review reports is not a new phenomenon. “I think it’s now increasingly recognized that the manipulation of the peer-review process, which was recognized around 2010, was probably an indication of paper mills operating at that point,” says Jennifer Byrne, director of biobanking at New South Wales Health in Sydney, Australia, who also studies research integrity in scientific literature.

Paper mills — organizations that churn out fake research papers and sell authorships to turn a profit — have been known to tamper with reviews to push manuscripts through to publication, says Byrne.

The fight against fake-paper factories that churn out sham science

However, when Bishop looked at Piniewski’s case, she could not find any overt evidence of paper-mill activity. Rather, she suspects that journal editors might be involved in cases of peer-review-report duplication and suggests studying the track records of those who’ve allowed inadequate or plagiarized reports to proliferate.

Piniewski’s team is also concerned about the rise of duplications as generative artificial intelligence (AI) becomes easier to access . Although his team didn’t look for signs of AI use, its ability to quickly ingest and rephrase large swathes of text is seen as an emerging issue.

A preprint posted in March 2 showed evidence of researchers using AI chatbots to assist with peer review, identifying specific adjectives that could be hallmarks of AI-written text in peer-review reports .

Bishop isn’t as concerned as Piniewski about AI-generated reports, saying that it’s easy to distinguish between AI-generated text and legitimate reviewer commentary. “The beautiful thing about peer review,” she says, is that it is “one thing you couldn’t do a credible job with AI”.

Preventing plagiarism

Publishers seem to be taking action. Bethany Baker, a media-relations manager at PLOS, who is based in Cambridge, UK, told Nature Index that the PLOS Publication Ethics team “is investigating the concerns raised in the Scientometrics article about potential plagiarism in peer reviews”.

How big is science’s fake-paper problem?

An Elsevier representative told Nature Index that the publisher “can confirm that this matter has been brought to our attention and we are conducting an investigation”.

In a statement, the MDPI Research Integrity and Publication Ethics Team said that it has been made aware of potential misconduct by reviewers in its journals and is “actively addressing and investigating this issue”. It did not confirm whether this was related to the Scientometrics article.

One proposed solution to the problem is ensuring that all submitted reviews are checked using plagiarism-detection software. In 2022, exploratory work by Adam Day, a data scientist at Sage Publications, based in Thousand Oaks, California, identified duplicated text in peer-review reports that might be suggestive of paper-mill activity. Day offered a similar solution of using anti-plagiarism software , such as Turnitin.

Piniewski expects the problem to get worse in the coming years, but he hasn’t received any unusual peer-review reports since those that originally sparked his research. Still, he says that he’s now even more vigilant. “If something unusual occurs, I will spot it.”

doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-024-01312-0

Piniewski, M., Jarić, I., Koutsoyiannis, D. & Kundzewicz, Z. W. Scientometrics https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-024-04960-1 (2024).

Article Google Scholar

Liang, W. et al. Preprint at arXiv https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2403.07183 (2024).

Download references

Related Articles

- Peer review

- Research management

Illuminating ‘the ugly side of science’: fresh incentives for reporting negative results

Career Feature 08 MAY 24

Algorithm ranks peer reviewers by reputation — but critics warn of bias

Nature Index 25 APR 24

Researchers want a ‘nutrition label’ for academic-paper facts

Nature Index 17 APR 24

Structure peer review to make it more robust

World View 16 APR 24

Is ChatGPT corrupting peer review? Telltale words hint at AI use

News 10 APR 24

Mount Etna’s spectacular smoke rings and more — April’s best science images

News 03 MAY 24

How reliable is this research? Tool flags papers discussed on PubPeer

News 29 APR 24

Faculty Positions at the Center for Machine Learning Research (CMLR), Peking University

CMLR's goal is to advance machine learning-related research across a wide range of disciplines.

Beijing, China

Center for Machine Learning Research (CMLR), Peking University

Faculty Positions at SUSTech Department of Biomedical Engineering

We seek outstanding applicants for full-time tenure-track/tenured faculty positions. Positions are available for both junior and senior-level.

Shenzhen, Guangdong, China

Southern University of Science and Technology (Biomedical Engineering)

Southeast University Future Technology Institute Recruitment Notice

Professor openings in mechanical engineering, control science and engineering, and integrating emerging interdisciplinary majors

Nanjing, Jiangsu (CN)

Southeast University

Staff Scientist

A Staff Scientist position is available in the laboratory of Drs. Elliot and Glassberg to study translational aspects of lung injury, repair and fibro

Maywood, Illinois

Loyola University Chicago - Department of Medicine

W3-Professorship (with tenure) in Inorganic Chemistry

The Institute of Inorganic Chemistry in the Faculty of Mathematics and Natural Sciences at the University of Bonn invites applications for a W3-Pro...

53113, Zentrum (DE)

Rheinische Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Bahauddin Zakariya University. As per my opinion the most difficult part is introduction and discussion of results because both are based on the context and author should a string grip on the ...

Call us: 412-365-1670. Email us: [email protected]. IM us from our website: library.chatham.edu. Procrastination. Avoiding procrastination is another tricky area ("turning on self-control," "calculating how long you can procrastinate until the situation becomes desperate," "ignoring the cat").

In reality, research requires students to read, interpret, and analyze new information, reshape their research question, and start again. This kind of sustained focus on a challenging task is very ...

After you get enough feedback and decide on the journal you will submit to, the process of real writing begins. Copy your outline into a separate file and expand on each of the points, adding data and elaborating on the details. When you create the first draft, do not succumb to the temptation of editing.

The paper is written in clear language in a style suitable for college research; Finishing Touches and Final Draft First drafts can be messy and that is ok. Revising and editing your paper may take as much time, or longer, than writing the first draft. Here are some tips to help you through the process. Take a break.

The Discussion is generally the hardest part of the paper to write. It is often subject to the most mistakes by the author. Most of these mistakes relate to i) not highlight-ing your key findings, ii) not differentiating your work from others, iii) writing long paragraphs, iv) not mentioning your limitations.

Table of contents. Step 1: Introduce your topic. Step 2: Describe the background. Step 3: Establish your research problem. Step 4: Specify your objective (s) Step 5: Map out your paper. Research paper introduction examples. Frequently asked questions about the research paper introduction.

Abstract. Writing qualitative research is a complex activity. Yet there is relatively little research about novices' experiences in learning to write this genre. The purpose of this multiple case study is to explore the challenges students face when they first encounter the qualitative research paradigm. Drawing upon interviews with students ...

A good research paper is not a big, general history or overview of everything that covers a great deal of information in a very superficial manner. It's narrowed and focused and goes deep into a limited area of a topic. By the time you are finished researching and writing, you have become something of an expert on that very narrow topic.

1099 Altmetric. Metrics. Papers from 2015 are a tougher read than some from the nineteenth century — and the problem isn't just about words, says Philip Ball. Modern scientific texts are more ...

The Discussion section might well be the hardest part of a paper to write. Yet, so useful! In a great Discussion section, the authors tie the different findings of the paper together, analyse them in the context of existing literature, offer speculations, suggest further research and highlight the study's significance and possible impact.

Take your time with the planning process. "It's worth consulting other researchers, doing a pilot study to test it, before you go out spending the time, money, and energy to do the big study," Crawford says. "Because once you begin the study, you can't stop.". Challenge: Assembling a Research Team.

The research abstract is a short summary of your completed research or project, or a specific development of practice that you would like to share with others. 2 The abstract needs to be coherent, concise, and understandable; this is usually the only part of the paper the reader can see when searching through electronic databases. In addition ...

It's the beginning of the semester—meaning, as a graduate student, it's time for me to get back into the groove of planning and writing long papers. For me, the hardest part of approaching a paper is coming up with a topic that will stay interesting to me throughout the research and writing process. A good example of this is from the end of last semester, when I found myself dreading the ...

1. Lack of motivation or focus. A lot of hard work and patience are needed to write a research paper. It can be hard to stay motivated during the process, and many problems may arise. You might have trouble focusing on the task, not have enough time because of other commitments or distractions, put it off, worry about finding reliable sources ...

4. Use subheadings: Dividing the Methods section in terms of the experiments helps the reader to follow the section better. You may write the specific objective of each experiment as a subheading. Alternatively, if applicable, the name of each experiment can also be used as subheading. 5.

The Hardest Part of Doing Research: Formulating a Research Question - Sean Q Kelly.

Common Causes of Research Paper Difficulties. IV. Developing an Effective Writing Strategy. V. Overcoming Procrastination and Distractions in Writing a Research Paper. VI. Making Use of Available Resources for Assistance with Your Project. VII .Conclusion: Understanding and Resolving Issues When Working on a Research Paper.

The real hardest part of a research project is restarting it after a long absence. Amid loose ends and notes that no longer make sense, one also must navigate the minefield of self-loathing and ...

Create a habit of reading scientific papers. To start, aim for reading one new paper per day. Then, slowly increase the number, but make sure it's realistic. Read the paper two or three times to have a better understanding of complicated ideas. Avoid highlighting each sentence on the article and mark only the most important information.

Not a phd student, but have published papers. In my opinion, finding the balance between explaining too much and not explaining is the most difficult task. You have to make sure that you are giving enough details. But you also have to be sure that you are not writing so much that you are going off topic. 5.

I think doing research and adhering to proper formatting is the most difficult part. However, today due to such tools as case converter and many other useful apps it became much easier. These lyrics from Chicago's 25 or 6 to 4 describe the hardest part for me: 36 votes, 45 comments.

Research Associate (part-time) / Ph.D. candidate in Surface Science The University of Bonn is an international research university with a wide education and research profile. With a 200-year ...