- Privacy Policy

Home » Tables in Research Paper – Types, Creating Guide and Examples

Tables in Research Paper – Types, Creating Guide and Examples

Table of Contents

Tables in Research Paper

Definition:

In Research Papers , Tables are a way of presenting data and information in a structured format. Tables can be used to summarize large amounts of data or to highlight important findings. They are often used in scientific or technical papers to display experimental results, statistical analyses, or other quantitative information.

Importance of Tables in Research Paper

Tables are an important component of a research paper as they provide a clear and concise presentation of data, statistics, and other information that support the research findings . Here are some reasons why tables are important in a research paper:

- Visual Representation : Tables provide a visual representation of data that is easy to understand and interpret. They help readers to quickly grasp the main points of the research findings and draw their own conclusions.

- Organize Data : Tables help to organize large amounts of data in a systematic and structured manner. This makes it easier for readers to identify patterns and trends in the data.

- Clarity and Accuracy : Tables allow researchers to present data in a clear and accurate manner. They can include precise numbers, percentages, and other information that may be difficult to convey in written form.

- Comparison: Tables allow for easy comparison between different data sets or groups. This makes it easier to identify similarities and differences, and to draw meaningful conclusions from the data.

- Efficiency: Tables allow for a more efficient use of space in the research paper. They can convey a large amount of information in a compact and concise format, which saves space and makes the research paper more readable.

Types of Tables in Research Paper

Most common Types of Tables in Research Paper are as follows:

- Descriptive tables : These tables provide a summary of the data collected in the study. They are usually used to present basic descriptive statistics such as means, medians, standard deviations, and frequencies.

- Comparative tables : These tables are used to compare the results of different groups or variables. They may be used to show the differences between two or more groups or to compare the results of different variables.

- Correlation tables: These tables are used to show the relationships between variables. They may show the correlation coefficients between variables, or they may show the results of regression analyses.

- Longitudinal tables : These tables are used to show changes in variables over time. They may show the results of repeated measures analyses or longitudinal regression analyses.

- Qualitative tables: These tables are used to summarize qualitative data such as interview transcripts or open-ended survey responses. They may present themes or categories that emerged from the data.

How to Create Tables in Research Paper

Here are the steps to create tables in a research paper:

- Plan your table: Determine the purpose of the table and the type of information you want to include. Consider the layout and format that will best convey your information.

- Choose a table format : Decide on the type of table you want to create. Common table formats include basic tables, summary tables, comparison tables, and correlation tables.

- Choose a software program : Use a spreadsheet program like Microsoft Excel or Google Sheets to create your table. These programs allow you to easily enter and manipulate data, format the table, and export it for use in your research paper.

- Input data: Enter your data into the spreadsheet program. Make sure to label each row and column clearly.

- Format the table : Apply formatting options such as font, font size, font color, cell borders, and shading to make your table more visually appealing and easier to read.

- Insert the table into your paper: Copy and paste the table into your research paper. Make sure to place the table in the appropriate location and refer to it in the text of your paper.

- Label the table: Give the table a descriptive title that clearly and accurately summarizes the contents of the table. Also, include a number and a caption that explains the table in more detail.

- Check for accuracy: Review the table for accuracy and make any necessary changes before submitting your research paper.

Examples of Tables in Research Paper

Examples of Tables in the Research Paper are as follows:

Table 1: Demographic Characteristics of Study Participants

This table shows the demographic characteristics of 200 participants in a research study. The table includes information about age, gender, and education level. The mean age of the participants was 35.2 years with a standard deviation of 8.6 years, and the age range was between 21 and 57 years. The table also shows that 46% of the participants were male and 54% were female. In terms of education, 10% of the participants had less than a high school education, 30% were high school graduates, 35% had some college education, and 25% had a bachelor’s degree or higher.

Table 2: Summary of Key Findings

This table summarizes the key findings of a study comparing three different groups on a particular variable. The table shows the mean score, standard deviation, t-value, and p-value for each group. The asterisk next to the t-value for Group 1 indicates that the difference between Group 1 and the other groups was statistically significant at p < 0.01, while the differences between Group 2 and Group 3 were not statistically significant.

Purpose of Tables in Research Paper

The primary purposes of including tables in a research paper are:

- To present data: Tables are an effective way to present large amounts of data in a clear and organized manner. Researchers can use tables to present numerical data, survey results, or other types of data that are difficult to represent in text.

- To summarize data: Tables can be used to summarize large amounts of data into a concise and easy-to-read format. Researchers can use tables to summarize the key findings of their research, such as descriptive statistics or the results of regression analyses.

- To compare data : Tables can be used to compare data across different variables or groups. Researchers can use tables to compare the characteristics of different study populations or to compare the results of different studies on the same topic.

- To enhance the readability of the paper: Tables can help to break up long sections of text and make the paper more visually appealing. By presenting data in a table, researchers can help readers to quickly identify the most important information and understand the key findings of the study.

Advantages of Tables in Research Paper

Some of the advantages of using tables in research papers include:

- Clarity : Tables can present data in a way that is easy to read and understand. They can help readers to quickly and easily identify patterns, trends, and relationships in the data.

- Efficiency: Tables can save space and reduce the need for lengthy explanations or descriptions of the data in the main body of the paper. This can make the paper more concise and easier to read.

- Organization: Tables can help to organize large amounts of data in a logical and meaningful way. This can help to reduce confusion and make it easier for readers to navigate the data.

- Comparison : Tables can be useful for comparing data across different groups, variables, or time periods. This can help to highlight similarities, differences, and changes over time.

- Visualization : Tables can also be used to visually represent data, making it easier for readers to see patterns and trends. This can be particularly useful when the data is complex or difficult to understand.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

How to Cite Research Paper – All Formats and...

Data Collection – Methods Types and Examples

Delimitations in Research – Types, Examples and...

Research Paper Format – Types, Examples and...

Research Process – Steps, Examples and Tips

Research Design – Types, Methods and Examples

Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Tables and Figures

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

Note: This page reflects the latest version of the APA Publication Manual (i.e., APA 7), which released in October 2019. The equivalent resources for the older APA 6 style can be found at this page as well as at this page (our old resources covered the material on this page on two separate pages).

The purpose of tables and figures in documents is to enhance your readers' understanding of the information in the document; usually, large amounts of information can be communicated more efficiently in tables or figures. Tables are any graphic that uses a row and column structure to organize information, whereas figures include any illustration or image other than a table.

General guidelines

Visual material such as tables and figures can be used quickly and efficiently to present a large amount of information to an audience, but visuals must be used to assist communication, not to use up space, or disguise marginally significant results behind a screen of complicated statistics. Ask yourself this question first: Is the table or figure necessary? For example, it is better to present simple descriptive statistics in the text, not in a table.

Relation of Tables or Figures and Text

Because tables and figures supplement the text, refer in the text to all tables and figures used and explain what the reader should look for when using the table or figure. Focus only on the important point the reader should draw from them, and leave the details for the reader to examine on their own.

Documentation

If you are using figures, tables and/or data from other sources, be sure to gather all the information you will need to properly document your sources.

Integrity and Independence

Each table and figure must be intelligible without reference to the text, so be sure to include an explanation of every abbreviation (except the standard statistical symbols and abbreviations).

Organization, Consistency, and Coherence

Number all tables sequentially as you refer to them in the text (Table 1, Table 2, etc.), likewise for figures (Figure 1, Figure 2, etc.). Abbreviations, terminology, and probability level values must be consistent across tables and figures in the same article. Likewise, formats, titles, and headings must be consistent. Do not repeat the same data in different tables.

Data in a table that would require only two or fewer columns and rows should be presented in the text. More complex data is better presented in tabular format. In order for quantitative data to be presented clearly and efficiently, it must be arranged logically, e.g. data to be compared must be presented next to one another (before/after, young/old, male/female, etc.), and statistical information (means, standard deviations, N values) must be presented in separate parts of the table. If possible, use canonical forms (such as ANOVA, regression, or correlation) to communicate your data effectively.

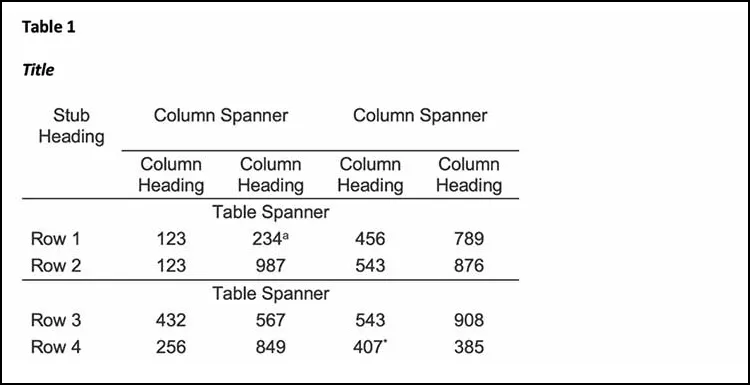

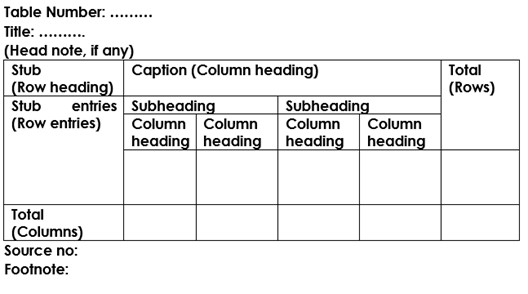

A generic example of a table with multiple notes formatted in APA 7 style.

Elements of Tables

Number all tables with Arabic numerals sequentially. Do not use suffix letters (e.g. Table 3a, 3b, 3c); instead, combine the related tables. If the manuscript includes an appendix with tables, identify them with capital letters and Arabic numerals (e.g. Table A1, Table B2).

Like the title of the paper itself, each table must have a clear and concise title. Titles should be written in italicized title case below the table number, with a blank line between the number and the title. When appropriate, you may use the title to explain an abbreviation parenthetically.

Comparison of Median Income of Adopted Children (AC) v. Foster Children (FC)

Keep headings clear and brief. The heading should not be much wider than the widest entry in the column. Use of standard abbreviations can aid in achieving that goal. There are several types of headings:

- Stub headings describe the lefthand column, or stub column , which usually lists major independent variables.

- Column headings describe entries below them, applying to just one column.

- Column spanners are headings that describe entries below them, applying to two or more columns which each have their own column heading. Column spanners are often stacked on top of column headings and together are called decked heads .

- Table Spanners cover the entire width of the table, allowing for more divisions or combining tables with identical column headings. They are the only type of heading that may be plural.

All columns must have headings, written in sentence case and using singular language (Item rather than Items) unless referring to a group (Men, Women). Each column’s items should be parallel (i.e., every item in a column labeled “%” should be a percentage and does not require the % symbol, since it’s already indicated in the heading). Subsections within the stub column can be shown by indenting headings rather than creating new columns:

Chemical Bonds

Ionic

Covalent

Metallic

The body is the main part of the table, which includes all the reported information organized in cells (intersections of rows and columns). Entries should be center aligned unless left aligning them would make them easier to read (longer entries, usually). Word entries in the body should use sentence case. Leave cells blank if the element is not applicable or if data were not obtained; use a dash in cells and a general note if it is necessary to explain why cells are blank. In reporting the data, consistency is key: Numerals should be expressed to a consistent number of decimal places that is determined by the precision of measurement. Never change the unit of measurement or the number of decimal places in the same column.

There are three types of notes for tables: general, specific, and probability notes. All of them must be placed below the table in that order.

General notes explain, qualify or provide information about the table as a whole. Put explanations of abbreviations, symbols, etc. here.

Example: Note . The racial categories used by the US Census (African-American, Asian American, Latinos/-as, Native-American, and Pacific Islander) have been collapsed into the category “non-White.” E = excludes respondents who self-identified as “White” and at least one other “non-White” race.

Specific notes explain, qualify or provide information about a particular column, row, or individual entry. To indicate specific notes, use superscript lowercase letters (e.g. a , b , c ), and order the superscripts from left to right, top to bottom. Each table’s first footnote must be the superscript a .

a n = 823. b One participant in this group was diagnosed with schizophrenia during the survey.

Probability notes provide the reader with the results of the tests for statistical significance. Asterisks indicate the values for which the null hypothesis is rejected, with the probability ( p value) specified in the probability note. Such notes are required only when relevant to the data in the table. Consistently use the same number of asterisks for a given alpha level throughout your paper.

* p < .05. ** p < .01. *** p < .001

If you need to distinguish between two-tailed and one-tailed tests in the same table, use asterisks for two-tailed p values and an alternate symbol (such as daggers) for one-tailed p values.

* p < .05, two-tailed. ** p < .01, two-tailed. † p <.05, one-tailed. †† p < .01, one-tailed.

Borders

Tables should only include borders and lines that are needed for clarity (i.e., between elements of a decked head, above column spanners, separating total rows, etc.). Do not use vertical borders, and do not use borders around each cell. Spacing and strict alignment is typically enough to clarify relationships between elements.

Example of a table in the text of an APA 7 paper. Note the lack of vertical borders.

Tables from Other Sources

If using tables from an external source, copy the structure of the original exactly, and cite the source in accordance with APA style .

Table Checklist

(Taken from the Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association , 7th ed., Section 7.20)

- Is the table necessary?

- Does it belong in the print and electronic versions of the article, or can it go in an online supplemental file?

- Are all comparable tables presented consistently?

- Are all tables numbered with Arabic numerals in the order they are mentioned in the text? Is the table number bold and left-aligned?

- Are all tables referred to in the text?

- Is the title brief but explanatory? Is it presented in italicized title case and left-aligned?

- Does every column have a column heading? Are column headings centered?

- Are all abbreviations; special use of italics, parentheses, and dashes; and special symbols explained?

- Are the notes organized according to the convention of general, specific, probability?

- Are table borders correctly used (top and bottom of table, beneath column headings, above table spanners)?

- Does the table use correct line spacing (double for the table number, title, and notes; single, one and a half, or double for the body)?

- Are entries in the left column left-aligned beneath the centered stub heading? Are all other column headings and cell entries centered?

- Are confidence intervals reported for all major point estimates?

- Are all probability level values correctly identified, and are asterisks attached to the appropriate table entries? Is a probability level assigned the same number of asterisks in all the tables in the same document?

- If the table or its data are from another source, is the source properly cited? Is permission necessary to reproduce the table?

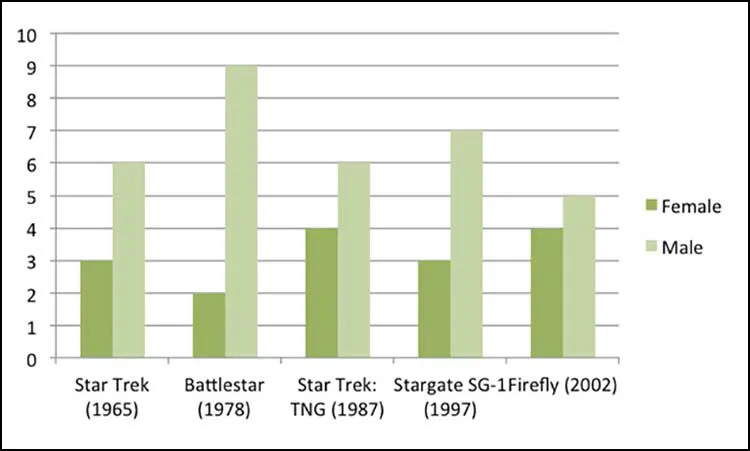

Figures include all graphical displays of information that are not tables. Common types include graphs, charts, drawings, maps, plots, and photos. Just like tables, figures should supplement the text and should be both understandable on their own and referenced fully in the text. This section details elements of formatting writers must use when including a figure in an APA document, gives an example of a figure formatted in APA style, and includes a checklist for formatting figures.

Preparing Figures

In preparing figures, communication and readability must be the ultimate criteria. Avoid the temptation to use the special effects available in most advanced software packages. While three-dimensional effects, shading, and layered text may look interesting to the author, overuse, inconsistent use, and misuse may distort the data, and distract or even annoy readers. Design properly done is inconspicuous, almost invisible, because it supports communication. Design improperly, or amateurishly, done draws the reader’s attention from the data, and makes him or her question the author’s credibility. Line drawings are usually a good option for readability and simplicity; for photographs, high contrast between background and focal point is important, as well as cropping out extraneous detail to help the reader focus on the important aspects of the photo.

Parts of a Figure

All figures that are part of the main text require a number using Arabic numerals (Figure 1, Figure 2, etc.). Numbers are assigned based on the order in which figures appear in the text and are bolded and left aligned.

Under the number, write the title of the figure in italicized title case. The title should be brief, clear, and explanatory, and both the title and number should be double spaced.

The image of the figure is the body, and it is positioned underneath the number and title. The image should be legible in both size and resolution; fonts should be sans serif, consistently sized, and between 8-14 pt. Title case should be used for axis labels and other headings; descriptions within figures should be in sentence case. Shading and color should be limited for clarity; use patterns along with color and check contrast between colors with free online checkers to ensure all users (people with color vision deficiencies or readers printing in grayscale, for instance) can access the content. Gridlines and 3-D effects should be avoided unless they are necessary for clarity or essential content information.

Legends, or keys, explain symbols, styles, patterns, shading, or colors in the image. Words in the legend should be in title case; legends should go within or underneath the image rather than to the side. Not all figures will require a legend.

Notes clarify the content of the figure; like tables, notes can be general, specific, or probability. General notes explain units of measurement, symbols, and abbreviations, or provide citation information. Specific notes identify specific elements using superscripts; probability notes explain statistical significance of certain values.

A generic example of a figure formatted in APA 7 style.

Figure Checklist

(Taken from the Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association , 7 th ed., Section 7.35)

- Is the figure necessary?

- Does the figure belong in the print and electronic versions of the article, or is it supplemental?

- Is the figure simple, clean, and free of extraneous detail?

- Is the figure title descriptive of the content of the figure? Is it written in italic title case and left aligned?

- Are all elements of the figure clearly labeled?

- Are the magnitude, scale, and direction of grid elements clearly labeled?

- Are parallel figures or equally important figures prepared according to the same scale?

- Are the figures numbered consecutively with Arabic numerals? Is the figure number bold and left aligned?

- Has the figure been formatted properly? Is the font sans serif in the image portion of the figure and between sizes 8 and 14?

- Are all abbreviations and special symbols explained?

- If the figure has a legend, does it appear within or below the image? Are the legend’s words written in title case?

- Are the figure notes in general, specific, and probability order? Are they double-spaced, left aligned, and in the same font as the paper?

- Are all figures mentioned in the text?

- Has written permission for print and electronic reuse been obtained? Is proper credit given in the figure caption?

- Have all substantive modifications to photographic images been disclosed?

- Are the figures being submitted in a file format acceptable to the publisher?

- Have the files been produced at a sufficiently high resolution to allow for accurate reproduction?

- SpringerLink shop

Figures and tables

Figures and tables (display items) are often the quickest way to communicate large amounts of complex information that would be complicated to explain in text.

Many readers will only look at your display items without reading the main text of your manuscript. Therefore, ensure your display items can stand alone from the text and communicate clearly your most significant results.

Display items are also important for attracting readers to your work. Well designed and attractive display items will hold the interest of readers, compel them to take time to understand a figure and can even entice them to read your full manuscript.

Finally, high-quality display items give your work a professional appearance . Readers will assume that a professional-looking manuscript contains good quality science. Thus readers may be more likely to trust your results and your interpretation of those results.

When deciding which of your results to present as display items consider the following questions:

- Are there any data that readers might rather see as a display item rather than text?

- Do your figures supplement the text and not just repeat what you have already stated?

- Have you put data into a table that could easily be explained in the text such as simple statistics or p values?

Tables are a concise and effective way to present large amounts of data. You should design them carefully so that you clearly communicate your results to busy researchers.

The following is an example of a well-designed table:

- Clear and concise legend/caption

- Data divided into categories for clarity

- Sufficient spacing between columns and rows

- Units are provided

- Font type and size are legible

Please enter the email address you used for your account. Your sign in information will be sent to your email address after it has been verified.

Your Guide to Creating Effective Tables and Figures in Research Papers

Research papers are full of data and other information that needs to be effectively illustrated and organized. Without a clear presentation of a study's data, the information will not reach the intended audience and could easily be misunderstood. Clarity of thought and purpose is essential for any kind of research. Using tables and figures to present findings and other data in a research paper can be effective ways to communicate that information to the chosen audience.

When manuscripts are screened, tables and figures can give reviewers and publication editors a quick overview of the findings and key information. After the research paper is published or accepted as a final dissertation, tables and figures will offer the same opportunity for other interested readers. While some readers may not read the entire paper, the tables and figures have the chance to still get the most important parts of your research across to those readers.

However, tables and figures are only valuable within a research paper if they are succinct and informative. Just about any audience—from scientists to the general public—should be able to identify key pieces of information in well-placed and well-organized tables. Figures can help to illustrate ideas and data visually. It is important to remember that tables and figures should not simply be repetitions of data presented in the text. They are not a vehicle for superfluous or repetitious information. Stay focused, stay organized, and you will be able to use tables and figures effectively in your research papers. The following key rules for using tables and figures in research papers will help you do just that.

Check style guides and journal requirements

The first step in deciding how you want to use tables and figures in your research paper is to review the requirements outlined by your chosen style guide or the submission requirements for the journal or publication you will be submitting to. For example, JMIR Publications states that for readability purposes, we encourage authors to include no more than 5 tables and no more than 8 figures per article. They continue to outline that tables should not go beyond the 1-inch margin of a portrait-orientation 8.5"x11" page using 12pt font or they may not be able to be included in your main manuscript because of our PDF sizing.

Consider the reviewers that will be examining your research paper for consistency, clarity, and applicability to a specific publication. If your chosen publication usually has shorter articles with supplemental information provided elsewhere, then you will want to keep the number of tables and figures to a minimum.

According to the Purdue Online Writing Lab (Purdue OWL), the American Psychological Association (APA) states that Data in a table that would require only two or fewer columns and rows should be presented in the text. More complex data is better presented in tabular format. You can avoid unnecessary tables by reviewing the data and deciding if it is simple enough to be included in the text. There is a balance, and the APA guideline above gives a good standard cutoff point for text versus table. Finally, when deciding if you should include a table or a figure, ask yourself is it necessary. Are you including it because you think you should or because you think it will look more professional, or are you including it because it is necessary to articulate the data? Only include tables or figures if they are necessary to articulate the data.

Table formatting

Creating tables is not as difficult as it once was. Most word processing programs have functions that allow you to simply select how many rows and columns you want, and then it builds the structure for you. Whether you create a table in LaTeX , Microsoft Word , Microsoft Excel , or Google Sheets , there are some key features that you will want to include. Tables generally include a legend, title, column titles, and the body of the table.

When deciding what the title of the table should be, think about how you would describe the table's contents in one sentence. There isn't a set length for table titles, and it varies depending on the discipline of the research, but it does need to be specific and clear what the table is presenting. Think of this as a concise topic sentence of the table.

Column titles should be designed in such a way that they simplify the contents of the table. Readers will generally skim the column titles first before getting into the data to prepare their minds for what they are about to see. While the text introducing the table will give a brief overview of what data is being presented, the column titles break that information down into easier-to-understand parts. The Purdue OWL gives a good example of what a table format could look like:

When deciding what your column titles should be, consider the width of the column itself when the data is entered. The heading should be as close to the length of the data as possible. This can be accomplished using standard abbreviations. When using symbols for the data, such as the percentage "%" symbol, place the symbol in the heading, and then you will not use the symbol in each entry, because it is already indicated in the column title.

For the body of the table, consistency is key. Use the same number of decimal places for numbers, keep the alignment the same throughout the table data, and maintain the same unit of measurement throughout each column. When information is changed within the same column, the reader can become confused, and your data may be considered inaccurate.

Figures in research papers

Figures can be of many different graphical types, including bar graphs, scatterplots, maps, photos, and more. Compared to tables, figures have a lot more variation and personalization. Depending on the discipline, figures take different forms. Sometimes a photograph is the best choice if you're illustrating spatial relationships or data hiding techniques in images. Sometimes a map is best to illustrate locations that have specific characteristics in an economic study. Carefully consider your reader's perspective and what detail you want them to see.

As with tables, your figures should be numbered sequentially and follow the same guidelines for titles and labels. Depending on your chosen style guide, keep the figure or figure placeholder as close to the text introducing it as possible. Similar to the figure title, any captions should be succinct and clear, and they should be placed directly under the figure.

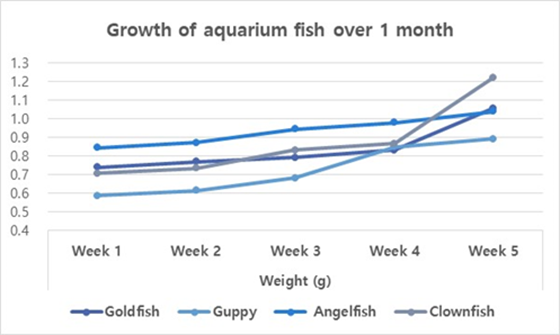

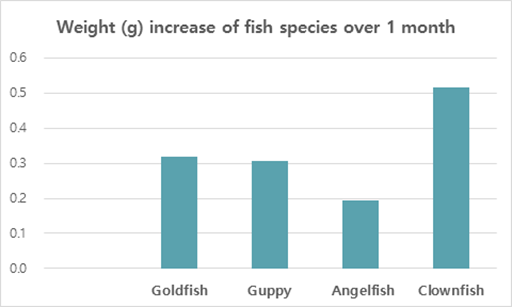

Using the wrong kind of figure is a common mistake that can affect a reader's experience with your research paper. Carefully consider what type of figure will best describe your point. For example, if you are describing levels of decomposition of different kinds of paper at a certain point in time, then a scatter plot would not be the appropriate depiction of that data; a bar graph would allow you to accurately show decomposition levels of each kind of paper at time "t." The Writing Center of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill has a good example of a bar graph offering easy-to-understand information:

If you have taken a figure from another source, such as from a presentation available online, then you will need to make sure to always cite the source. If you've modified the figure in any way, then you will need to say that you adapted the figure from that source. Plagiarism can still happen with figures – and even tables – so be sure to include a citation if needed.

Using the tips above, you can take your research data and give your reader or reviewer a clear perspective on your findings. As The Writing Center recommends, Consider the best way to communicate information to your audience, especially if you plan to use data in the form of numbers, words, or images that will help you construct and support your argument. If you can summarize the data in a couple of sentences, then don't try and expand that information into an unnecessary table or figure. Trying to use a table or figure in such cases only lengthens the paper and can make the tables and figures meaningless instead of informative.

Carefully choose your table and figure style so that they will serve as quick and clear references for your reader to see patterns, relationships, and trends you have discovered in your research. For additional assistance with formatting and requirements, be sure to review your publication or style guide's instructions to ensure success in the review and submission process.

Related Posts

How to Write a Compare and Contrast Essay

The Best Way to Synthesize Academic Research

- Academic Writing Advice

- All Blog Posts

- Writing Advice

- Admissions Writing Advice

- Book Writing Advice

- Short Story Advice

- Employment Writing Advice

- Business Writing Advice

- Web Content Advice

- Article Writing Advice

- Magazine Writing Advice

- Grammar Advice

- Dialect Advice

- Editing Advice

- Freelance Advice

- Legal Writing Advice

- Poetry Advice

- Graphic Design Advice

- Logo Design Advice

- Translation Advice

- Blog Reviews

- Short Story Award Winners

- Scholarship Winners

Need an academic editor before submitting your work?

Effective Use of Tables and Figures in Research Papers

Research papers are often based on copious amounts of data that can be summarized and easily read through tables and graphs. When writing a research paper , it is important for data to be presented to the reader in a visually appealing way. The data in figures and tables, however, should not be a repetition of the data found in the text. There are many ways of presenting data in tables and figures, governed by a few simple rules. An APA research paper and MLA research paper both require tables and figures, but the rules around them are different. When writing a research paper, the importance of tables and figures cannot be underestimated. How do you know if you need a table or figure? The rule of thumb is that if you cannot present your data in one or two sentences, then you need a table .

Using Tables

Tables are easily created using programs such as Excel. Tables and figures in scientific papers are wonderful ways of presenting data. Effective data presentation in research papers requires understanding your reader and the elements that comprise a table. Tables have several elements, including the legend, column titles, and body. As with academic writing, it is also just as important to structure tables so that readers can easily understand them. Tables that are disorganized or otherwise confusing will make the reader lose interest in your work.

- Title: Tables should have a clear, descriptive title, which functions as the “topic sentence” of the table. The titles can be lengthy or short, depending on the discipline.

- Column Titles: The goal of these title headings is to simplify the table. The reader’s attention moves from the title to the column title sequentially. A good set of column titles will allow the reader to quickly grasp what the table is about.

- Table Body: This is the main area of the table where numerical or textual data is located. Construct your table so that elements read from up to down, and not across.

Related: Done organizing your research data effectively in tables? Check out this post on tips for citing tables in your manuscript now!

The placement of figures and tables should be at the center of the page. It should be properly referenced and ordered in the number that it appears in the text. In addition, tables should be set apart from the text. Text wrapping should not be used. Sometimes, tables and figures are presented after the references in selected journals.

Using Figures

Figures can take many forms, such as bar graphs, frequency histograms, scatterplots, drawings, maps, etc. When using figures in a research paper, always think of your reader. What is the easiest figure for your reader to understand? How can you present the data in the simplest and most effective way? For instance, a photograph may be the best choice if you want your reader to understand spatial relationships.

- Figure Captions: Figures should be numbered and have descriptive titles or captions. The captions should be succinct enough to understand at the first glance. Captions are placed under the figure and are left justified.

- Image: Choose an image that is simple and easily understandable. Consider the size, resolution, and the image’s overall visual attractiveness.

- Additional Information: Illustrations in manuscripts are numbered separately from tables. Include any information that the reader needs to understand your figure, such as legends.

Common Errors in Research Papers

Effective data presentation in research papers requires understanding the common errors that make data presentation ineffective. These common mistakes include using the wrong type of figure for the data. For instance, using a scatterplot instead of a bar graph for showing levels of hydration is a mistake. Another common mistake is that some authors tend to italicize the table number. Remember, only the table title should be italicized . Another common mistake is failing to attribute the table. If the table/figure is from another source, simply put “ Note. Adapted from…” underneath the table. This should help avoid any issues with plagiarism.

Using tables and figures in research papers is essential for the paper’s readability. The reader is given a chance to understand data through visual content. When writing a research paper, these elements should be considered as part of good research writing. APA research papers, MLA research papers, and other manuscripts require visual content if the data is too complex or voluminous. The importance of tables and graphs is underscored by the main purpose of writing, and that is to be understood.

Frequently Asked Questions

"Consider the following points when creating figures for research papers: Determine purpose: Clarify the message or information to be conveyed. Choose figure type: Select the appropriate type for data representation. Prepare and organize data: Collect and arrange accurate and relevant data. Select software: Use suitable software for figure creation and editing. Design figure: Focus on clarity, labeling, and visual elements. Create the figure: Plot data or generate the figure using the chosen software. Label and annotate: Clearly identify and explain all elements in the figure. Review and revise: Verify accuracy, coherence, and alignment with the paper. Format and export: Adjust format to meet publication guidelines and export as suitable file."

"To create tables for a research paper, follow these steps: 1) Determine the purpose and information to be conveyed. 2) Plan the layout, including rows, columns, and headings. 3) Use spreadsheet software like Excel to design and format the table. 4) Input accurate data into cells, aligning it logically. 5) Include column and row headers for context. 6) Format the table for readability using consistent styles. 7) Add a descriptive title and caption to summarize and provide context. 8) Number and reference the table in the paper. 9) Review and revise for accuracy and clarity before finalizing."

"Including figures in a research paper enhances clarity and visual appeal. Follow these steps: Determine the need for figures based on data trends or to explain complex processes. Choose the right type of figure, such as graphs, charts, or images, to convey your message effectively. Create or obtain the figure, properly citing the source if needed. Number and caption each figure, providing concise and informative descriptions. Place figures logically in the paper and reference them in the text. Format and label figures clearly for better understanding. Provide detailed figure captions to aid comprehension. Cite the source for non-original figures or images. Review and revise figures for accuracy and consistency."

"Research papers use various types of tables to present data: Descriptive tables: Summarize main data characteristics, often presenting demographic information. Frequency tables: Display distribution of categorical variables, showing counts or percentages in different categories. Cross-tabulation tables: Explore relationships between categorical variables by presenting joint frequencies or percentages. Summary statistics tables: Present key statistics (mean, standard deviation, etc.) for numerical variables. Comparative tables: Compare different groups or conditions, displaying key statistics side by side. Correlation or regression tables: Display results of statistical analyses, such as coefficients and p-values. Longitudinal or time-series tables: Show data collected over multiple time points with columns for periods and rows for variables/subjects. Data matrix tables: Present raw data or matrices, common in experimental psychology or biology. Label tables clearly, include titles, and use footnotes or captions for explanations."

Enago is a very useful site. It covers nearly all topics of research writing and publishing in a simple, clear, attractive way. Though I’m a journal editor having much knowledge and training in these issues, I always find something new in this site. Thank you

“Thank You, your contents really help me :)”

Rate this article Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published.

Enago Academy's Most Popular Articles

- Reporting Research

Explanatory & Response Variable in Statistics — A quick guide for early career researchers!

Often researchers have a difficult time choosing the parameters and variables (like explanatory and response…

- Manuscript Preparation

- Publishing Research

How to Use Creative Data Visualization Techniques for Easy Comprehension of Qualitative Research

“A picture is worth a thousand words!”—an adage used so often stands true even whilst…

- Figures & Tables

Effective Use of Statistics in Research – Methods and Tools for Data Analysis

Remember that impending feeling you get when you are asked to analyze your data! Now…

- Old Webinars

- Webinar Mobile App

SCI中稿技巧: 提升研究数据的说服力

如何寻找原创研究课题 快速定位目标文献的有效搜索策略 如何根据期刊指南准备手稿的对应部分 论文手稿语言润色实用技巧分享,快速提高论文质量

Distill: A Journal With Interactive Images for Machine Learning Research

Research is a wide and extensive field of study. This field has welcomed a plethora…

Explanatory & Response Variable in Statistics — A quick guide for early career…

How to Create and Use Gantt Charts

Sign-up to read more

Subscribe for free to get unrestricted access to all our resources on research writing and academic publishing including:

- 2000+ blog articles

- 50+ Webinars

- 10+ Expert podcasts

- 50+ Infographics

- 10+ Checklists

- Research Guides

We hate spam too. We promise to protect your privacy and never spam you.

I am looking for Editing/ Proofreading services for my manuscript Tentative date of next journal submission:

What should universities' stance be on AI tools in research and academic writing?

- Discoveries

- Right Journal

- Journal Metrics

- Journal Fit

- Abbreviation

- In-Text Citations

- Bibliographies

- Writing an Article

- Peer Review Types

- Acknowledgements

- Withdrawing a Paper

- Form Letter

- ISO, ANSI, CFR

- Google Scholar

- Journal Manuscript Editing

- Research Manuscript Editing

Book Editing

- Manuscript Editing Services

Medical Editing

- Bioscience Editing

- Physical Science Editing

- PhD Thesis Editing Services

- PhD Editing

- Master’s Proofreading

- Bachelor’s Editing

- Dissertation Proofreading Services

- Best Dissertation Proofreaders

- Masters Dissertation Proofreading

- PhD Proofreaders

- Proofreading PhD Thesis Price

- Journal Article Editing

- Book Editing Service

- Editing and Proofreading Services

- Research Paper Editing

- Medical Manuscript Editing

- Academic Editing

- Social Sciences Editing

- Academic Proofreading

- PhD Theses Editing

- Dissertation Proofreading

- Proofreading Rates UK

- Medical Proofreading

- PhD Proofreading Services UK

- Academic Proofreading Services UK

Medical Editing Services

- Life Science Editing

- Biomedical Editing

- Environmental Science Editing

- Pharmaceutical Science Editing

- Economics Editing

- Psychology Editing

- Sociology Editing

- Archaeology Editing

- History Paper Editing

- Anthropology Editing

- Law Paper Editing

- Engineering Paper Editing

- Technical Paper Editing

- Philosophy Editing

- PhD Dissertation Proofreading

- Lektorat Englisch

- Akademisches Lektorat

- Lektorat Englisch Preise

- Wissenschaftliches Lektorat

- Lektorat Doktorarbeit

PhD Thesis Editing

- Thesis Proofreading Services

- PhD Thesis Proofreading

- Proofreading Thesis Cost

- Proofreading Thesis

- Thesis Editing Services

- Professional Thesis Editing

- Thesis Editing Cost

- Proofreading Dissertation

- Dissertation Proofreading Cost

- Dissertation Proofreader

- Correção de Artigos Científicos

- Correção de Trabalhos Academicos

- Serviços de Correção de Inglês

- Correção de Dissertação

- Correção de Textos Precos

- 定額 ネイティブチェック

- Copy Editing

- FREE Courses

- Revision en Ingles

- Revision de Textos en Ingles

- Revision de Tesis

- Revision Medica en Ingles

- Revision de Tesis Precio

- Revisão de Artigos Científicos

- Revisão de Trabalhos Academicos

- Serviços de Revisão de Inglês

- Revisão de Dissertação

- Revisão de Textos Precos

- Corrección de Textos en Ingles

- Corrección de Tesis

- Corrección de Tesis Precio

- Corrección Medica en Ingles

- Corrector ingles

Select Page

Presenting Data and Sources Accurately and Effectively

Table of Contents (Guide To Publication)

Part ii: preparing, presenting and polishing your work – chapter 5, 5. presenting data and sources accurately and effectively.

Journal guidelines vary greatly when it comes to the advice they provide about presenting data and referring to sources. In some cases separate sections containing detailed instructions about exactly how to lay out tables and figures and how to format citations and references will be provided, while in others authors will simply be advised to format tables and figures in ‘an appropriate’ manner and will be lucky to find two or three reference examples to follow. Tables and figures do seem to receive fairly good coverage in the guidelines of most scholarly journals, however, and generally you will be able to find some indication of the referencing style required. So read anything and everything you can find in the guidelines about these elements of your paper, pay careful attention to any models provided (both appropriate and inappropriate), consult any manuals or other style guides mentioned and take a close look at papers already published by the journal to see how references, tables and figures were successfully formatted. What you learn can be both followed and used to inspire your own designs when constructing your references, tables and figures.

5.1 Tables, Figures and Other Research Data: Guidelines and Good Practice

Although the advice I share in this section should not be taken as a substitute for journal guidelines when it comes to the layout of tables and figures, it stems from a familiarity with the guidelines of many journals and the experience of encountering many tables and figures that present unfamiliar data. As with every other aspect of your paper, clarity, accuracy and precision are essential, and in the case of tables and figures, there’s little space for explanation, so data must for the most part stand on their own, with only the format you shape around them to lend structure and meaning. This means that the format of your tables and figures needs to be thought out very carefully: there needs to be enough space both to present and to separate all the information your tables and figures contain in ways that facilitate your readers’ understanding. Poorly laid out tables and figures can instead obscure that understanding, so it’s important to analyse your tables and figures as a reader would, seeking the information you’re providing, and then edit and reshape until your tables and figures achieve just what they should. Some journals will insist that tables and figures only be used if they include or illustrate information not presented elsewhere in the paper, and frown on those that repeat data in any way. So the first consideration should be whether you need tables and figures to share your research and results effectively and, if so, what exactly those tables and figures should contain. Illustrating devices or conditions discussed in a paper, providing graphs and lists of data that cannot be accommodated in detail in an article and highlighting the most significant aspects of the results of a study are a few of many reasons to provide tables and figures for your readers,

Once you’ve decided that your paper does require tables and/or figures, some basic practices and concerns found in the guidelines of many journals should be considered. For tables, for instance, ask yourself if you will you require lines or rules to separate the material – some journals ask that vertical lines be avoided, others that rules of all kinds be avoided, and a table may take more space on the page if you need to construct it without lines. For figures, there is the matter of using colour or not: some journals only print tables in monochrome (black and white) and include figures in colour solely online, while others will be happy to print your figures in colour, but they may charge a significant amount for it, so you’ll need to decide whether printing the figures in colour is worth the cost. For both tables and figures, consider the overall size of each item in terms of the printed page of the journal, and if your tables or figures will need to be reduced to such a degree that they may no longer be clear or legible, you may have to present the information in a different format or divide the information you’ve compiled in one table or figure into two or three tables or figures. Online publication is often the best route for large tables and figures, and colour rarely proves a problem with online publication.

Remember as you’re constructing your tables and figures that as a general rule each table and figure should be able to stand alone, whether it’s printed amidst the text of your paper or published separately online. For this reason, all abbreviations beyond the standard ones for common measures (cm, Hz, mph, N, SD, etc.) will need to be defined either in the table or figure itself or in close association with it, and this is the case even if you’ve already defined the abbreviations in your paper and in any preceding tables or figures. You can choose to write each term out in full within the body of the table or figure, or introduce and define the abbreviations in the heading or title of a table or in the caption or legend of a figure, or you can define any abbreviations used in a note at the bottom of the table or figure. This last approach is used for tables more often than for figures, and the abbreviations within a table are usually connected to the definitions in the note via superscript lowercase letters (but not always, so do check the journal guidelines). If you’re in any doubt about whether an abbreviation should be defined for your readers, it’s best to define it: such attention is a sign of conscientious documentation, and if the journal deems the definition unnecessary, it can always be removed.

Be sure that the terms you use in your tables and figures match those you use in the paper itself precisely, and that the abbreviations take the same forms in both the paper and the tables and figures. In fact, it’s essential to ensure that all the data presented in tables and figures are entirely consistent with data presented in the paper (and the abstract as well). This is to say that the format in which you present similar data in both places should be identical, and any overlapping data should be exactly the same in content as well as format in both places. Remember that data stand alone in a table or figure, so they need to be perfect and should be checked more than once by more than one pair of knowledgeable eyes. Even a simple error can not only render the information incorrect, it can also alter the overall appearance of the table or figure, and since an effective visual representation of information is precisely the goal of tables and figures, this can be disastrous. All numbers in a table or figure can be written as numerals and should be accurately formatted in keeping with English convention and/or journal guidelines (on the use of numbers in academic or scientific prose, see Section 4.4.1 above).

Journal guidelines should also be consulted to determine exactly how to place and submit your tables and figures in relation to your paper. Variations are myriad: when submitting to some journals you can simply place your tables and figures where you’d have them located in the published version; others will want all tables and figures added at the end of the document and only placement notes – e.g., ‘Insert Table 1 here’ and ‘Figure 3 about here’ – within the body of the paper. ‘Added at the end of the document’ can mean either before or after the reference list, and for some journals tables should precede figures, whereas for others it’s just the opposite. Sometimes guidelines will ask that tables be embedded in or tacked onto the end of the paper, but the figures submitted in separate files, with only the figure legends included in the paper, usually at the end. The point is to note and comply with whatever is required: it’s disappointing to discover that guidelines won’t let you use tables and figures quite as you’d hoped, but better that than writing the paper with the tables and figures you want only to have it rejected because of them or (in the best scenario) have to completely rewrite your paper with different, fewer or no tables at all. If a set number or style or size of tables and figures is absolutely central to your paper, then be sure to choose a journal that allows it.

However many or few tables and figures you use, be sure to label each one accurately and to refer to each of them in the body of your paper as you report and discuss your results. Virtually all journal guidelines specify this (and others expect it), and it’s also a simple courtesy to your reader that facilitates that reader’s understanding of your paper and your tables and figures in relation to it. Unnumbered or misnumbered figures and tables to which the reader is not accurately and precisely referred at an appropriate point in the text defeat their own purpose and negate some of the hard work that went into making them by leaving it to the reader to sort out the relationship between your text and your tables and figures. Tables and figures should also be referred to in numerical order, which means that they should be numbered according to the order in which they are mentioned in the text regardless of where they are actually placed in relation to the text. For clarity, they should also be referred to by number whenever mentioned, with the usual format being ‘Figure 1’ or ‘Table 2,’ unless, of course, the journal guidelines specify a different format (such as ‘Fig.1’), and whatever format used to refer to a table or figure should match that used in the heading or caption to label the table or figure itself. In the heading/caption for a table or figure, a full stop usually follows the number (Table 1. Demographic characteristics of study participants) unless there are instructions in the guidelines to the contrary (calling for a colon, for instance, after the number instead of a full stop). The title or heading of a table is generally placed above the table, whereas figure captions or legends often appear beneath figures, but guidelines (as well as style manuals) differ on this as well, so again, reading and following the guidelines of the specific journal is essential to success (see also Section 1.2 above).

Finally, if you are using in your figures any images for which the copyright belongs to someone other than yourself, you’ll need to acknowledge the source(s), usually in the relevant figure captions, and you’ll also need to obtain permissions to reproduce such images. Although all permissions need not be obtained until your paper is accepted for publication in a journal, it’s a good idea to indicate when you submit your paper which figures will require permissions and from which individuals and institutions those permissions will need to be requested, as well as noting any permissions that you’ve already obtained. Planning ahead when it comes to permissions can prevent delays and help speed up the publication process, but remember, too, that permissions to reproduce images from other publications can be costly and the expense is usually met by the author, so it’s a good idea to consider carefully whether reproducing images and other material that require permissions is really necessary and worth the cost.

PRS Tip : So much attention is paid to numerical data in tables and images in figures that the words appearing in tables and figures sometimes suffer neglect. If the words used in tables and figures do not effectively clarify and categorise the information presented, the reader’s understanding suffers as well. So when using words in a table or figure, it’s good to keep these basic practices in mind:

- Use standard abbreviations for measures and define all abbreviations beyond those for common measures.

- Use terms and abbreviations that match exactly those used for the same concepts, categories and measures in the paper and in its other tables and figures.

- Make sure that all words are visible and legible, and not obscured or crowded by other elements of the table or figure.

- Do not allow a word to be split inappropriately onto two separate lines – use a wider column instead.

- Use capitalisation consistently throughout the tables and figures in a paper.

- If the table or figure was originally prepared in another language, translate all words into accurate English – if you’re writing for an English-speaking audience, all aspects of your paper, including your tables and figures, should be entirely legible to that audience.

This article is part of a book called Guide to Academic and Scientific Publication: How To Get Your Writing Published in Scholarly Journals . It provides practical advice on planning, preparing and submitting articles for publication in scholarly journals.

Whether you are looking for information on designing an academic or scientific article, constructing a scholarly argument, targeting the right journal, following journal guidelines with precision, providing accurate and complete references, writing correct and elegant scholarly English, communicating with journal editors or revising your paper in light of that communication, you will find guidance, tips and examples in this manual.

This book is focusing on sound scholarly principles and practices as well as the expectations and requirements of academic and scientific journals, this guide is suitable for use in a wide variety of disciplines, including Economics, Engineering, the Humanities, Law, Management, Mathematics, Medicine and the Social, Physical and Biological Sciences .

You might be interested in Services offered by Proof-Reading-Service.com

Journal editing.

Journal article editing services

PhD thesis editing services

Scientific Editing

Manuscript editing.

Manuscript editing services

Expert Editing

Expert editing for all papers

Research Editing

Research paper editing services

Professional book editing services

- The Dos and Don’ts of Using Tables and Figures in Your Writing

by acburton | Apr 29, 2024 | Resources for Students , Writing Resources

What do you do when words just aren’t enough?

For subjects outside of the Humanities, including STEM disciplines such as mathematics, physical sciences, and engineering, using tables and figures throughout your writing can effectively break-up longer pieces of text by presenting useful data and statistics. Within the Humanities, the incorporation of multimodal elements is championed in UCI courses (Humanities Core!), and can aid in your construction or support of an argument. But what are some things to keep in mind when including these components alongside your written work?

When incorporating tables and figures into writing, you’ll want to be mindful of the:

Who Needs a Table or Figure?

What is the best way to convey the information you have to a reader? What discipline are you working in? How best can you visualize the data you would like to share?

Starting with these questions (or others like it) is a great place to begin when thinking about whether or not to include tables and figures in your writing. While incorporating the following into research or lab reports for a STEM related course may seem like a no-brainer, you’ll still want to examine what kind of data you’ll want to share with your audience or reader and what is the best way (table or figure) to present it. With your audience in mind, think about their expectations as well as your ability to present your data in the most effective, concise, and efficient manner possible.

Synthesize versus Visualize

The incorporation of tables into your writing often serves as one method for synthesizing information, including existing literature, or to explain variables or present the wording of a specific kind of data (e.g., the wording of survey questions) (UNC). In contrast, figures (images, charts, graphs (pie charts, line graphs, etc.* [1] )) are the visual representation of results (UNC). They can be used to provide a visual component or impact and can effectively communicate primary findings such as the relationship (patterns or trends), between two variables (UNC).

Think of figures like you would paragraphs. If you have several important things to say, consider making more than one table or figure, or incorporating other visual elements, one for each important idea that you would like to share. No matter what, strive for clarity ! Don’t put too much information on your tables or figures, making them crowded or difficult to follow. Likewise, do use consistent elements (such as a uniform font) in your tables or figures so as to not distract your reader or audience.

Let’s go through a few other Dos and Don’ts for incorporating tables and figures into your writing!

use a table or figure in your writing as a method of making your data more concise and presentable.

use tables and figures to enhance or supplement the text. They should be self-explanatory.

- be sure that your tables and figures reflect your data accurately.

Don’ts

- incorporate a table or figure just because you want to reach the page minimum for an assignment.

- use a table or figure solely for aesthetic purposes. This may backfire, as it could demonstrate to your reader that you do not have a solid grasp on the requirements or expectations of the assignment or discipline.

- repeat data already shown on one table or figure.

Remember that this is not an exhaustive list. Strive for clarity whenever you decide to incorporate tables or figures into your writing!

How Tables and Figures Interact with Text

Although tables and figures must be able to stand alone, without additional information provided in the text, it is recommended that you reference your tables and figures within the text, reinforcing your decision to incorporate them into your writing.

To refer to tables and figures from within the text, the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill suggests beginning your sentences with:

- Clauses beginning with “as”: “As shown in Table 1, …”

- A Passive voice: “Results are shown in Table 1.”

- An Active voice (if appropriate for your discipline): “Table 1 shows that …”

- A Parentheses: “Each sample tested positive for three nutrients (Table 1).”

Another way that tables and figures interact with text is in the captions. Captions should be concise, descriptive, and comprehensive. They should describe what is being shown, draw attention to important features, and, sometimes, may also include interpretations of the data or results (UNC). Figures are typically read from left to right, top to bottom, but for additional formatting information, reference the citation style guide used for your specific assignment. We recommend using Purdue Owl as a resource for additional clarification.

Check out these Dos and Don’ts surrounding the interaction between tables, figures, and texts!

- clarify any abbreviations you use within the text or in your captions.

consider incorporating your data into the text instead of using a table or figure if there is simple or less data to show.

- repeat data or information already summarized in the text.

Tables, and Figures, and Blog Posts, Oh My! Visit the Writing Center for additional assistance on using tables and figures in your writing!

https://writingcenter.unc.edu/tips-and-tools/figures-and-charts/#:~:text=Think%20of%20graphs%20like%20you,way%20that%20is%20visually%20clear .

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC10394528/

https://core.humanities.uci.edu/index.php/spring/multimodal-presentation-tools/

[1] This is not an exhaustive list; don’t forget X, Y scatter plots or XY line graphs are also great examples!

Our Newest Resources!

- Revision vs. Proofreading

- Engaging With Sources Effectively

- Synthesis and Making Connections for Strong Analysis

- Writing Strong Titles

Additional Resources

- Graduate Writing Consultants

- Instructor Resources

- Student Resources

- Quick Guides and Handouts

- Self-Guided and Directed Learning Activities

- Manuscript Preparation

How to Use Tables and Figures effectively in Research Papers

- 3 minute read

- 43.3K views

Table of Contents

Data is the most important component of any research. It needs to be presented effectively in a paper to ensure that readers understand the key message in the paper. Figures and tables act as concise tools for clear presentation . Tables display information arranged in rows and columns in a grid-like format, while figures convey information visually, and take the form of a graph, diagram, chart, or image. Be it to compare the rise and fall of GDPs among countries over the years or to understand how COVID-19 has impacted incomes all over the world, tables and figures are imperative to convey vital findings accurately.

So, what are some of the best practices to follow when creating meaningful and attractive tables and figures? Here are some tips on how best to present tables and figures in a research paper.

Guidelines for including tables and figures meaningfully in a paper:

- Self-explanatory display items: Sometimes, readers, reviewers and journal editors directly go to the tables and figures before reading the entire text. So, the tables need to be well organized and self-explanatory.

- Avoidance of repetition: Tables and figures add clarity to the research. They complement the research text and draw attention to key points. They can be used to highlight the main points of the paper, but values should not be repeated as it defeats the very purpose of these elements.

- Consistency: There should be consistency in the values and figures in the tables and figures and the main text of the research paper.

- Informative titles: Titles should be concise and describe the purpose and content of the table. It should draw the reader’s attention towards the key findings of the research. Column heads, axis labels, figure labels, etc., should also be appropriately labelled.

- Adherence to journal guidelines: It is important to follow the instructions given in the target journal regarding the preparation and presentation of figures and tables, style of numbering, titles, image resolution, file formats, etc.

Now that we know how to go about including tables and figures in the manuscript, let’s take a look at what makes tables and figures stand out and create impact.

How to present data in a table?

For effective and concise presentation of data in a table, make sure to:

- Combine repetitive tables: If the tables have similar content, they should be organized into one.

- Divide the data: If there are large amounts of information, the data should be divided into categories for more clarity and better presentation. It is necessary to clearly demarcate the categories into well-structured columns and sub-columns.

- Keep only relevant data: The tables should not look cluttered. Ensure enough spacing.

Example of table presentation in a research paper

For comprehensible and engaging presentation of figures:

- Ensure clarity: All the parts of the figure should be clear. Ensure the use of a standard font, legible labels, and sharp images.

- Use appropriate legends: They make figures effective and draw attention towards the key message.

- Make it precise: There should be correct use of scale bars in images and maps, appropriate units wherever required, and adequate labels and legends.

It is important to get tables and figures correct and precise for your research paper to convey your findings accurately and clearly. If you are confused about how to suitably present your data through tables and figures, do not worry. Elsevier Author Services are well-equipped to guide you through every step to ensure that your manuscript is of top-notch quality.

- Research Process

What is a Problem Statement? [with examples]

What is the Background of a Study and How Should it be Written?

You may also like.

Make Hook, Line, and Sinker: The Art of Crafting Engaging Introductions

Can Describing Study Limitations Improve the Quality of Your Paper?

A Guide to Crafting Shorter, Impactful Sentences in Academic Writing

6 Steps to Write an Excellent Discussion in Your Manuscript

How to Write Clear and Crisp Civil Engineering Papers? Here are 5 Key Tips to Consider

The Clear Path to An Impactful Paper: ②

The Essentials of Writing to Communicate Research in Medicine

Changing Lines: Sentence Patterns in Academic Writing

Input your search keywords and press Enter.

How to make a scientific table | Step-by-step and Formatting

It’s time to learn how to make a scientific table to increase the readability and attractiveness of your research paper.

When writing a research paper, there is frequently a massive quantity of data that must be incorporated to meet the research’s purpose. Instead of stuffing your research paper with all this information, you can employ visual assets to make it simpler to read and use to your advantage to make it more appealing to readers.

In this Mind The Graph article, you will learn how to make a scientific table properly, to attract readers and improve understandability.

What is a scientific table and what are its purposes?

Tables are typically used to organize data that is too extensive or nuanced to properly convey in the text, allowing the reader to quickly see and comprehend the findings. Tables can be used to summarize information, explain variables, or organize and present surveys. They can be used to highlight trends or patterns in data and to make research more readable by separating numerical data from text. Tables, although full, should not be overly convoluted.

Tables can only display numerical values and text in columns and rows. Any other type of illustration, such as a chart, graph, photograph, drawing, and so on is called a figure.

If you’re not sure whether to use tables or figures in your research, see How to Include Figures in a Research Paper to find out.

Table formatting

This section teaches you all you need to know on how to make a scientific table to include in your research paper. The proper table format is extremely basic and straightforward to accomplish, here’s a simple guideline to help you:

- Number: If you have more than one table, number them sequentially (Table 1, Table 2…).

- Referencing: Each table must be referred to in the text with a capital T: “as seen in Table 1”.

- Title: Make sure the title corresponds to the topic of the table. Tables should have a precise, informative title that serves as an explanation for the table. Titles can be short or long depending on their subject.

- Column headings: Headings must be helpful and clear when representing the type of data provided. The reader’s attention is drawn progressively from the headline to the column title. A solid collection of column headings will help the reader understand what the table is about immediately.

- Table body: This is the major section of the table that contains numerical or textual data. Make your table such that the elements read from top to bottom, not across.

- Needed information: Make sure to include units, error values and number of samples, as well as explain whatever abbreviation or symbol is used in tables.

- Lines: Limit the use of lines, only use what’s necessary.

Steps to make an effective scientific table

Now that you understand the fundamentals of how to make a scientific table , consider the following ideas and best practices for creating the most effective tables for your research work:

- If your study includes both a table and a graph, avoid including the same information in both.

- Do not duplicate information from a table in a text.

- Make your table aesthetically appealing and easy to read by leaving enough space between columns and rows and using a basic yet effective structure.

- If your table has a lot of information, consider categorizing it and dividing it into columns.

- Consider merging tables with repeated information or deleting those that may not be essential.

- Use footnotes to highlight important information for any of the cells. Use an alphabetical footnote marker if your table contains numerical data.

- Cite the reference if the table you’re displaying contains data from prior research to avoid plagiarism.

Make scientifically accurate infographics in minutes

Aside from adding tables to make your research paper more precise and appealing, consider using infographics, Mind the Graph is a simple tool for creating excellent scientific infographics that may help you solidify and improve the authority of your research.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Exclusive high quality content about effective visual communication in science.

Unlock Your Creativity

Create infographics, presentations and other scientifically-accurate designs without hassle — absolutely free for 7 days!

About Jessica Abbadia

Jessica Abbadia is a lawyer that has been working in Digital Marketing since 2020, improving organic performance for apps and websites in various regions through ASO and SEO. Currently developing scientific and intellectual knowledge for the community's benefit. Jessica is an animal rights activist who enjoys reading and drinking strong coffee.

Content tags

- Search Menu

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies