Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Chapter 3: Developing a Research Question

3.5 Quantitative, Qualitative, & Mixed Methods Research Approaches

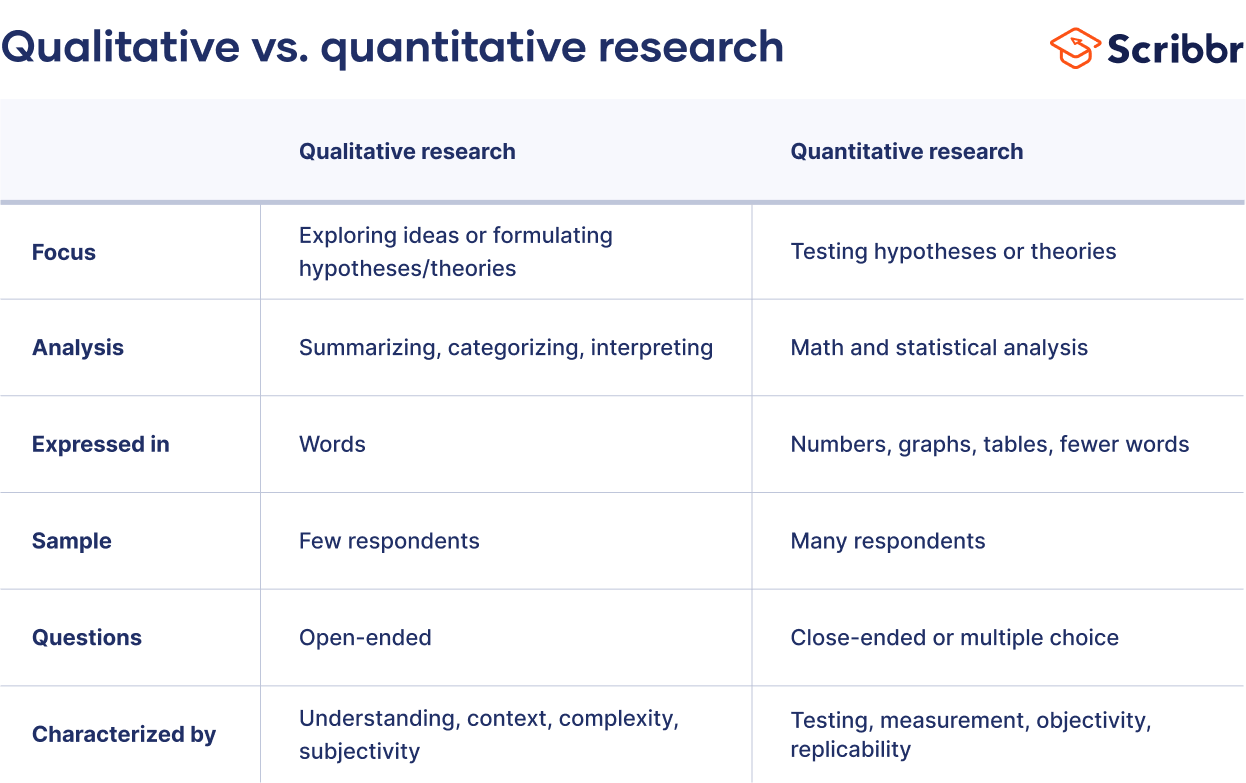

Generally speaking, qualitative and quantitative approaches are the most common methods utilized by researchers. While these two approaches are often presented as a dichotomy, in reality it is much more complicated. Certainly, there are researchers who fall on the more extreme ends of these two approaches, however most recognize the advantages and usefulness of combining both methods (mixed methods). In the following sections we look at quantitative, qualitative, and mixed methodological approaches to undertaking research. Table 2.3 synthesizes the differences between quantitative and qualitative research approaches.

Quantitative Research Approaches

A quantitative approach to research is probably the most familiar approach for the typical research student studying at the introductory level. Arising from the natural sciences, e.g., chemistry and biology), the quantitative approach is framed by the belief that there is one reality or truth that simply requires discovering, known as realism. Therefore, asking the “right” questions is key. Further, this perspective favours observable causes and effects and is therefore outcome-oriented. Typically, aggregate data is used to see patterns and “truth” about the phenomenon under study. True understanding is determined by the ability to predict the phenomenon.

Qualitative Research Approaches

On the other side of research approaches is the qualitative approach. This is generally considered to be the opposite of the quantitative approach. Qualitative researchers are considered phenomenologists, or human-centred researchers. Any research must account for the humanness, i.e., that they have thoughts, feelings, and experiences that they interpret of the participants. Instead of a realist perspective suggesting one reality or truth, qualitative researchers tend to favour the constructionist perspective: knowledge is created, not discovered, and there are multiple realities based on someone’s perspective. Specifically, a researcher needs to understand why, how and to whom a phenomenon applies. These aspects are usually unobservable since they are the thoughts, feelings and experiences of the person. Most importantly, they are a function of their perception of those things rather than what the outside researcher interprets them to be. As a result, there is no such thing as a neutral or objective outsider, as in the quantitative approach. Rather, the approach is generally process-oriented. True understanding, rather than information based on prediction, is based on understanding action and on the interpretive meaning of that action.

Table 3.3 Differences between quantitative and qualitative approaches (from Adjei, n.d).

Note: Researchers in emergency and safety professions are increasingly turning toward qualitative methods. Here is an interesting peer paper related to qualitative research in emergency care.

Qualitative Research in Emergency Care Part I: Research Principles and Common Applications by Choo, Garro, Ranney, Meisel, and Guthrie (2015)

Interview-based Qualitative Research in Emergency Care Part II: Data Collection, Analysis and Results Reporting.

Research Methods for the Social Sciences: An Introduction Copyright © 2020 by Valerie Sheppard is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Introduction: Considering Qualitative, Quantitative and Mixed Methods Research

- First Online: 24 December 2020

Cite this chapter

- Alistair McBeath 2 &

- Sofie Bager-Charleson 2

3705 Accesses

1 Citations

In this introduction we will explore some of the differences and similarities between quantitative and qualitative research, and dispel some of the perceived mysteries within research. We will briefly introduce some of the advantages and disadvantages of both approaches. There will also be an introduction to some of the philosophical assumptions that underpin quantitative and qualitative research methods, with specific mention made of ontological and epistemological considerations. These about the nature of existence (ontology) and how we might gain knowledge about the nature of existence (epistemology). We will explore the difference between positivist and interpretivist research, idiographic versus nomothetic, and inductive and deductive perspectives. Finally, we will also distinguish between qualitative, quantitative and mixed method s research, gaining familiarity with attempts to bridge divides between disciplines and research approaches. Throughout this book, the issue of research-supported practice will remain an underlying theme. This chapter aims to support a research-based practice, aided by considering the multiple routes into research. The chapter encourages you to familiarise yourself with approaches ranging from phenomenological experiences to more nomothetic, generalising and comparing foci like outcome measuring and random control trials (RCTs), understood with a basic knowledge of statistics. The book introduces you to a range of research, guided by interest in separate approaches but also inductive—deductive combinations, as in grounded theory together with pluralistic and mixed methods approaches, all with a shared interest in providing support in the field of mental health and emotional wellbeing. Primarily, we hope that the chapter will encourage you to start considering your own research. Enjoy!

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Bager-Charleson, S., McBeath, A. G., & du Plock, S. (2019). The relationship between psychotherapy practice and research: A mixed-methods exploration of practitioners’ views. Counselling and Psychotherapy Research, 19 (3), 195–205. https://doi.org/10.1002/capr.12196 .

Article Google Scholar

Bager-Charleson, S. du Plock, S and McBeath, A.G. (2018) Therapists Have a lot to Add to the Field of Research, but Many Don’t Make it There: A Narrative Thematic Inquiry into Counsellors’ and Psychotherapists’ Embodied Engagement with Research. Psychoanalysis and Language, 7 (1), 4–22.

Google Scholar

Bhaskar, R. (1975). A realist theory of science . Hassocks, England: Harvester Press.

Bhaskar, R. (1998). The possibility of naturalism . London: Routledge.

Crotty, M. (1998). The foundations of social research . London: Sage Publications.

Danermark, B., Ekstrom, M., Jakobsen, L., & Karlsson, J. C. (2002). Explaining society: Critical realism in the social sciences . New York: Routledge.

Denscombe, M. (1998). The good research for small –Scale social research project . Philadelphia: Open University Press.

Department of Health and Social Care (2017). A Framework for mental health research.

Ellis, D., & Tucker, I. (2015). Social psychology of emotions. London, United Kingdom: Sage.

Evered, R., & Louis, R. (1981). Alternative Perspectives in the Organizational Sciences: ‘Inquiry from the Inside’ and ‘Inquiry from the Outside. Academy of Management Review, 6 (3), 385–395.

Glaser, B. G., & Strauss, A. L. (1967). The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research . New York: Aldine de Gruyter.

Landrum, B., & Garza, G. (2015). Mending fences: Defining the domains and approaches of quantitative and qualitative research. Qualitative Psychology, 2 (2), 199–209. https://doi.org/10.1037/qup0000030 .

Malterud, K. (2001). The art and science of clinical knowledge: Evidence beyond measures and numbers. The Lancet., 358 , 397–400. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(01)05548-9 .

McBeath, A. G. (2019). The motivations of psychotherapists: An in-depth survey. Counselling and Psychotherapy Research, 19 (4), 377–387. https://doi.org/10.1002/capr.12225 .

McBeath, A. G., Bager-Charleson, S., & Abarbanel, A. (2019). Therapists and Academic Writing: ‘Once upon a time psychotherapy practitioners and researchers were the same people. European Journal for Qualitative Research in Psychotherapy, 19 , 103–116.

McEvoy, P., & Richards, D. (2006). A critical realist rationale for using a combination of quantitative and qualitative methods. Journal of Research in Nursing, 11 , 66–78. https://doi.org/10.1177/1744987106060192 .

Rukeyser, M. (1968). The speed of darkness . New York: Random House.

Sandelowski, M. (2001). Real qualitative researchers do not count: The use of numbers in qualitative research. Research in Nursing and Health, 24 (3), 230–240. https://doi.org/10.1002/nur.1025 .

Scotland, J. (2012). Exploring the philosophical underpinnings of research: Relating ontology and epistemology to the methodology and methods of the scientific, interpretive and critical research paradigms. English Language Teaching, 5 (9), 9–16. https://doi.org/10.5539/elt.v5n9p9 .

Smith, J. A., & Osborn, S. (2008). Interpretative phenomenological analysis . In J. A. Smith (Ed.), Qualitative psychology (pp. 53–80). London: Sage.

Ukpabi, D. C., Enyindah, C. W., & Dapper, E. M. (2014). Who is winning the paradigm war? The futility of paradigm inflexibility in Administrative Sciences Research. IOSR Journal of Business and Management, 16 (7), 13–17.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Metanoia Institute, London, UK

Alistair McBeath & Sofie Bager-Charleson

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Alistair McBeath .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Sofie Bager-Charleson & Alistair McBeath &

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2020 The Author(s)

About this chapter

McBeath, A., Bager-Charleson, S. (2020). Introduction: Considering Qualitative, Quantitative and Mixed Methods Research. In: Bager-Charleson, S., McBeath, A. (eds) Enjoying Research in Counselling and Psychotherapy. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-55127-8_1

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-55127-8_1

Published : 24 December 2020

Publisher Name : Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-030-55126-1

Online ISBN : 978-3-030-55127-8

eBook Packages : Behavioral Science and Psychology Behavioral Science and Psychology (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Log in using your username and password

- Search More Search for this keyword Advanced search

- Latest content

- Current issue

- Write for Us

- BMJ Journals More You are viewing from: Google Indexer

You are here

- Volume 20, Issue 3

- Mixed methods research: expanding the evidence base

- Article Text

- Article info

- Citation Tools

- Rapid Responses

- Article metrics

- Allison Shorten 1 ,

- Joanna Smith 2

- 1 School of Nursing , University of Alabama at Birmingham , USA

- 2 Children's Nursing, School of Healthcare , University of Leeds , UK

- Correspondence to Dr Allison Shorten, School of Nursing, University of Alabama at Birmingham, 1720 2nd Ave South, Birmingham, AL, 35294, USA; [email protected]; ashorten{at}uab.edu

https://doi.org/10.1136/eb-2017-102699

Statistics from Altmetric.com

Request permissions.

If you wish to reuse any or all of this article please use the link below which will take you to the Copyright Clearance Center’s RightsLink service. You will be able to get a quick price and instant permission to reuse the content in many different ways.

Introduction

‘Mixed methods’ is a research approach whereby researchers collect and analyse both quantitative and qualitative data within the same study. 1 2 Growth of mixed methods research in nursing and healthcare has occurred at a time of internationally increasing complexity in healthcare delivery. Mixed methods research draws on potential strengths of both qualitative and quantitative methods, 3 allowing researchers to explore diverse perspectives and uncover relationships that exist between the intricate layers of our multifaceted research questions. As providers and policy makers strive to ensure quality and safety for patients and families, researchers can use mixed methods to explore contemporary healthcare trends and practices across increasingly diverse practice settings.

What is mixed methods research?

Mixed methods research requires a purposeful mixing of methods in data collection, data analysis and interpretation of the evidence. The key word is ‘mixed’, as an essential step in the mixed methods approach is data linkage, or integration at an appropriate stage in the research process. 4 Purposeful data integration enables researchers to seek a more panoramic view of their research landscape, viewing phenomena from different viewpoints and through diverse research lenses. For example, in a randomised controlled trial (RCT) evaluating a decision aid for women making choices about birth after caesarean, quantitative data were collected to assess knowledge change, levels of decisional conflict, birth choices and outcomes. 5 Qualitative narrative data were collected to gain insight into women’s decision-making experiences and factors that influenced their choices for mode of birth. 5

In contrast, multimethod research uses a single research paradigm, either quantitative or qualitative. Data are collected and analysed using different methods within the same paradigm. 6 7 For example, in a multimethods qualitative study investigating parent–professional shared decision-making regarding diagnosis of suspected shunt malfunction in children, data collection included audio recordings of admission consultations and interviews 1 week post consultation, with interactions analysed using conversational analysis and the framework approach for the interview data. 8

What are the strengths and challenges in using mixed methods?

Selecting the right research method starts with identifying the research question and study aims. A mixed methods design is appropriate for answering research questions that neither quantitative nor qualitative methods could answer alone. 4 9–11 Mixed methods can be used to gain a better understanding of connections or contradictions between qualitative and quantitative data; they can provide opportunities for participants to have a strong voice and share their experiences across the research process, and they can facilitate different avenues of exploration that enrich the evidence and enable questions to be answered more deeply. 11 Mixed methods can facilitate greater scholarly interaction and enrich the experiences of researchers as different perspectives illuminate the issues being studied. 11

The process of mixing methods within one study, however, can add to the complexity of conducting research. It often requires more resources (time and personnel) and additional research training, as multidisciplinary research teams need to become conversant with alternative research paradigms and different approaches to sample selection, data collection, data analysis and data synthesis or integration. 11

What are the different types of mixed methods designs?

Mixed methods research comprises different types of design categories, including explanatory, exploratory, parallel and nested (embedded) designs. 2 Table 1 summarises the characteristics of each design, the process used and models of connecting or integrating data. For each type of research, an example was created to illustrate how each study design might be applied to address similar but different nursing research aims within the same general nursing research area.

- View inline

Types of mixed methods designs*

What should be considered when evaluating mixed methods research?

When reading mixed methods research or writing a proposal using mixed methods to answer a research question, the six questions below are a useful guide 12 :

Does the research question justify the use of mixed methods?

Is the method sequence clearly described, logical in flow and well aligned with study aims?

Is data collection and analysis clearly described and well aligned with study aims?

Does one method dominate the other or are they equally important?

Did the use of one method limit or confound the other method?

When, how and by whom is data integration (mixing) achieved?

For more detail of the evaluation guide, refer to the McMaster University Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool. 12 The quality checklist for appraising published mixed methods research could also be used as a design checklist when planning mixed methods studies.

- Elliot AE , et al

- Creswell JW ,

- Plano ClarkV L

- Greene JC ,

- Caracelli VJ ,

- Ivankova NV

- Shorten A ,

- Shorten B ,

- Halcomb E ,

- Cheater F ,

- Bekker H , et al

- Tashakkori A ,

- Creswell JW

- 12. ↵ National Collaborating Centre for Methods and Tools . Appraising qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods studies included in mixed studies reviews: the MMAT . Hamilton, ON : BMJ Publishing Group , 2015 . http://www.nccmt.ca/resources/search/232 (accessed May 2017) .

Competing interests None declared.

Provenance and peer review Commissioned; internally peer reviewed.

Read the full text or download the PDF:

- Subject List

- Take a Tour

- For Authors

- Subscriber Services

- Publications

- African American Studies

- African Studies

- American Literature

- Anthropology

- Architecture Planning and Preservation

- Art History

- Atlantic History

- Biblical Studies

- British and Irish Literature

- Childhood Studies

- Chinese Studies

- Cinema and Media Studies

- Communication

- Criminology

- Environmental Science

- Evolutionary Biology

- International Law

- International Relations

- Islamic Studies

- Jewish Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Latino Studies

- Linguistics

- Literary and Critical Theory

- Medieval Studies

- Military History

- Political Science

- Public Health

- Renaissance and Reformation

- Social Work

- Urban Studies

- Victorian Literature

- Browse All Subjects

How to Subscribe

- Free Trials

In This Article Expand or collapse the "in this article" section Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Research Sampling Strategies

Introduction.

- Sampling Strategies

- Sample Size

- Qualitative Design Considerations

- Discipline Specific and Special Considerations

- Sampling Strategies Unique to Mixed Methods Designs

Related Articles Expand or collapse the "related articles" section about

About related articles close popup.

Lorem Ipsum Sit Dolor Amet

Vestibulum ante ipsum primis in faucibus orci luctus et ultrices posuere cubilia Curae; Aliquam ligula odio, euismod ut aliquam et, vestibulum nec risus. Nulla viverra, arcu et iaculis consequat, justo diam ornare tellus, semper ultrices tellus nunc eu tellus.

- Mixed Methods Research

- Qualitative Research Design

- Quantitative Research Designs in Educational Research

Other Subject Areas

Forthcoming articles expand or collapse the "forthcoming articles" section.

- Gender, Power, and Politics in the Academy

- Girls' Education in the Developing World

- Non-Formal & Informal Environmental Education

- Find more forthcoming articles...

- Export Citations

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Research Sampling Strategies by Timothy C. Guetterman LAST MODIFIED: 26 February 2020 DOI: 10.1093/obo/9780199756810-0241

Sampling is a critical, often overlooked aspect of the research process. The importance of sampling extends to the ability to draw accurate inferences, and it is an integral part of qualitative guidelines across research methods. Sampling considerations are important in quantitative and qualitative research when considering a target population and when drawing a sample that will either allow us to generalize (i.e., quantitatively) or go into sufficient depth (i.e., qualitatively). While quantitative research is generally concerned with probability-based approaches, qualitative research typically uses nonprobability purposeful sampling approaches. Scholars generally focus on two major sampling topics: sampling strategies and sample sizes. Or simply, researchers should think about who to include and how many; both of these concerns are key. Mixed methods studies have both qualitative and quantitative sampling considerations. However, mixed methods studies also have unique considerations based on the relationship of quantitative and qualitative research within the study.

Sampling in Qualitative Research

Sampling in qualitative research may be divided into two major areas: overall sampling strategies and issues around sample size. Sampling strategies refers to the process of sampling and how to design a sampling. Qualitative sampling typically follows a nonprobability-based approach, such as purposive or purposeful sampling where participants or other units of analysis are selected intentionally for their ability to provide information to address research questions. Sample size refers to how many participants or other units are needed to address research questions. The methodological literature about sampling tends to fall into these two broad categories, though some articles, chapters, and books cover both concepts. Others have connected sampling to the type of qualitative design that is employed. Additionally, researchers might consider discipline specific sampling issues as much research does tend to operate within disciplinary views and constraints. Scholars in many disciplines have examined sampling around specific topics, research problems, or disciplines and provide guidance to making sampling decisions, such as appropriate strategies and sample size.

back to top

Users without a subscription are not able to see the full content on this page. Please subscribe or login .

Oxford Bibliographies Online is available by subscription and perpetual access to institutions. For more information or to contact an Oxford Sales Representative click here .

- About Education »

- Meet the Editorial Board »

- Academic Achievement

- Academic Audit for Universities

- Academic Freedom and Tenure in the United States

- Action Research in Education

- Adjuncts in Higher Education in the United States

- Administrator Preparation

- Adolescence

- Advanced Placement and International Baccalaureate Courses

- Advocacy and Activism in Early Childhood

- African American Racial Identity and Learning

- Alaska Native Education

- Alternative Certification Programs for Educators

- Alternative Schools

- American Indian Education

- Animals in Environmental Education

- Art Education

- Artificial Intelligence and Learning

- Assessing School Leader Effectiveness

- Assessment, Behavioral

- Assessment, Educational

- Assessment in Early Childhood Education

- Assistive Technology

- Augmented Reality in Education

- Beginning-Teacher Induction

- Bilingual Education and Bilingualism

- Black Undergraduate Women: Critical Race and Gender Perspe...

- Blended Learning

- Case Study in Education Research

- Changing Professional and Academic Identities

- Character Education

- Children’s and Young Adult Literature

- Children's Beliefs about Intelligence

- Children's Rights in Early Childhood Education

- Citizenship Education

- Civic and Social Engagement of Higher Education

- Classroom Learning Environments: Assessing and Investigati...

- Classroom Management

- Coherent Instructional Systems at the School and School Sy...

- College Admissions in the United States

- College Athletics in the United States

- Community Relations

- Comparative Education

- Computer-Assisted Language Learning

- Computer-Based Testing

- Conceptualizing, Measuring, and Evaluating Improvement Net...

- Continuous Improvement and "High Leverage" Educational Pro...

- Counseling in Schools

- Critical Approaches to Gender in Higher Education

- Critical Perspectives on Educational Innovation and Improv...

- Critical Race Theory

- Crossborder and Transnational Higher Education

- Cross-National Research on Continuous Improvement

- Cross-Sector Research on Continuous Learning and Improveme...

- Cultural Diversity in Early Childhood Education

- Culturally Responsive Leadership

- Culturally Responsive Pedagogies

- Culturally Responsive Teacher Education in the United Stat...

- Curriculum Design

- Data Collection in Educational Research

- Data-driven Decision Making in the United States

- Deaf Education

- Desegregation and Integration

- Design Thinking and the Learning Sciences: Theoretical, Pr...

- Development, Moral

- Dialogic Pedagogy

- Digital Age Teacher, The

- Digital Citizenship

- Digital Divides

- Disabilities

- Distance Learning

- Distributed Leadership

- Doctoral Education and Training

- Early Childhood Education and Care (ECEC) in Denmark

- Early Childhood Education and Development in Mexico

- Early Childhood Education in Aotearoa New Zealand

- Early Childhood Education in Australia

- Early Childhood Education in China

- Early Childhood Education in Europe

- Early Childhood Education in Sub-Saharan Africa

- Early Childhood Education in Sweden

- Early Childhood Education Pedagogy

- Early Childhood Education Policy

- Early Childhood Education, The Arts in

- Early Childhood Mathematics

- Early Childhood Science

- Early Childhood Teacher Education

- Early Childhood Teachers in Aotearoa New Zealand

- Early Years Professionalism and Professionalization Polici...

- Economics of Education

- Education For Children with Autism

- Education for Sustainable Development

- Education Leadership, Empirical Perspectives in

- Education of Native Hawaiian Students

- Education Reform and School Change

- Educational Statistics for Longitudinal Research

- Educator Partnerships with Parents and Families with a Foc...

- Emotional and Affective Issues in Environmental and Sustai...

- Emotional and Behavioral Disorders

- Environmental and Science Education: Overlaps and Issues

- Environmental Education

- Environmental Education in Brazil

- Epistemic Beliefs

- Equity and Improvement: Engaging Communities in Educationa...

- Equity, Ethnicity, Diversity, and Excellence in Education

- Ethical Research with Young Children

- Ethics and Education

- Ethics of Teaching

- Ethnic Studies

- Evidence-Based Communication Assessment and Intervention

- Family and Community Partnerships in Education

- Family Day Care

- Federal Government Programs and Issues

- Feminization of Labor in Academia

- Finance, Education

- Financial Aid

- Formative Assessment

- Future-Focused Education

- Gender and Achievement

- Gender and Alternative Education

- Gender-Based Violence on University Campuses

- Gifted Education

- Global Mindedness and Global Citizenship Education

- Global University Rankings

- Governance, Education

- Grounded Theory

- Growth of Effective Mental Health Services in Schools in t...

- Higher Education and Globalization

- Higher Education and the Developing World

- Higher Education Faculty Characteristics and Trends in the...

- Higher Education Finance

- Higher Education Governance

- Higher Education Graduate Outcomes and Destinations

- Higher Education in Africa

- Higher Education in China

- Higher Education in Latin America

- Higher Education in the United States, Historical Evolutio...

- Higher Education, International Issues in

- Higher Education Management

- Higher Education Policy

- Higher Education Research

- Higher Education Student Assessment

- High-stakes Testing

- History of Early Childhood Education in the United States

- History of Education in the United States

- History of Technology Integration in Education

- Homeschooling

- Inclusion in Early Childhood: Difference, Disability, and ...

- Inclusive Education

- Indigenous Education in a Global Context

- Indigenous Learning Environments

- Indigenous Students in Higher Education in the United Stat...

- Infant and Toddler Pedagogy

- Inservice Teacher Education

- Integrating Art across the Curriculum

- Intelligence

- Intensive Interventions for Children and Adolescents with ...

- International Perspectives on Academic Freedom

- Intersectionality and Education

- Knowledge Development in Early Childhood

- Leadership Development, Coaching and Feedback for

- Leadership in Early Childhood Education

- Leadership Training with an Emphasis on the United States

- Learning Analytics in Higher Education

- Learning Difficulties

- Learning, Lifelong

- Learning, Multimedia

- Learning Strategies

- Legal Matters and Education Law

- LGBT Youth in Schools

- Linguistic Diversity

- Linguistically Inclusive Pedagogy

- Literacy Development and Language Acquisition

- Literature Reviews

- Mathematics Identity

- Mathematics Instruction and Interventions for Students wit...

- Mathematics Teacher Education

- Measurement for Improvement in Education

- Measurement in Education in the United States

- Meta-Analysis and Research Synthesis in Education

- Methodological Approaches for Impact Evaluation in Educati...

- Methodologies for Conducting Education Research

- Mindfulness, Learning, and Education

- Motherscholars

- Multiliteracies in Early Childhood Education

- Multiple Documents Literacy: Theory, Research, and Applica...

- Multivariate Research Methodology

- Museums, Education, and Curriculum

- Music Education

- Narrative Research in Education

- Native American Studies

- Note-Taking

- Numeracy Education

- One-to-One Technology in the K-12 Classroom

- Online Education

- Open Education

- Organizing for Continuous Improvement in Education

- Organizing Schools for the Inclusion of Students with Disa...

- Outdoor Play and Learning

- Outdoor Play and Learning in Early Childhood Education

- Pedagogical Leadership

- Pedagogy of Teacher Education, A

- Performance Objectives and Measurement

- Performance-based Research Assessment in Higher Education

- Performance-based Research Funding

- Phenomenology in Educational Research

- Philosophy of Education

- Physical Education

- Podcasts in Education

- Policy Context of United States Educational Innovation and...

- Politics of Education

- Portable Technology Use in Special Education Programs and ...

- Post-humanism and Environmental Education

- Pre-Service Teacher Education

- Problem Solving

- Productivity and Higher Education

- Professional Development

- Professional Learning Communities

- Program Evaluation

- Programs and Services for Students with Emotional or Behav...

- Psychology Learning and Teaching

- Psychometric Issues in the Assessment of English Language ...

- Qualitative Data Analysis Techniques

- Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Research Samp...

- Queering the English Language Arts (ELA) Writing Classroom

- Race and Affirmative Action in Higher Education

- Reading Education

- Refugee and New Immigrant Learners

- Relational and Developmental Trauma and Schools

- Relational Pedagogies in Early Childhood Education

- Reliability in Educational Assessments

- Religion in Elementary and Secondary Education in the Unit...

- Researcher Development and Skills Training within the Cont...

- Research-Practice Partnerships in Education within the Uni...

- Response to Intervention

- Restorative Practices

- Risky Play in Early Childhood Education

- Scale and Sustainability of Education Innovation and Impro...

- Scaling Up Research-based Educational Practices

- School Accreditation

- School Choice

- School Culture

- School District Budgeting and Financial Management in the ...

- School Improvement through Inclusive Education

- School Reform

- Schools, Private and Independent

- School-Wide Positive Behavior Support

- Science Education

- Secondary to Postsecondary Transition Issues

- Self-Regulated Learning

- Self-Study of Teacher Education Practices

- Service-Learning

- Severe Disabilities

- Single Salary Schedule

- Single-sex Education

- Single-Subject Research Design

- Social Context of Education

- Social Justice

- Social Network Analysis

- Social Pedagogy

- Social Science and Education Research

- Social Studies Education

- Sociology of Education

- Standards-Based Education

- Statistical Assumptions

- Student Access, Equity, and Diversity in Higher Education

- Student Assignment Policy

- Student Engagement in Tertiary Education

- Student Learning, Development, Engagement, and Motivation ...

- Student Participation

- Student Voice in Teacher Development

- Sustainability Education in Early Childhood Education

- Sustainability in Early Childhood Education

- Sustainability in Higher Education

- Teacher Beliefs and Epistemologies

- Teacher Collaboration in School Improvement

- Teacher Evaluation and Teacher Effectiveness

- Teacher Preparation

- Teacher Training and Development

- Teacher Unions and Associations

- Teacher-Student Relationships

- Teaching Critical Thinking

- Technologies, Teaching, and Learning in Higher Education

- Technology Education in Early Childhood

- Technology, Educational

- Technology-based Assessment

- The Bologna Process

- The Regulation of Standards in Higher Education

- Theories of Educational Leadership

- Three Conceptions of Literacy: Media, Narrative, and Gamin...

- Tracking and Detracking

- Traditions of Quality Improvement in Education

- Transformative Learning

- Transitions in Early Childhood Education

- Tribally Controlled Colleges and Universities in the Unite...

- Understanding the Psycho-Social Dimensions of Schools and ...

- University Faculty Roles and Responsibilities in the Unite...

- Using Ethnography in Educational Research

- Value of Higher Education for Students and Other Stakehold...

- Virtual Learning Environments

- Vocational and Technical Education

- Wellness and Well-Being in Education

- Women's and Gender Studies

- Young Children and Spirituality

- Young Children's Learning Dispositions

- Young Children's Working Theories

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Policy

- Legal Notice

- Accessibility

Powered by:

- [66.249.64.20|45.133.227.243]

- 45.133.227.243

Join thousands of product people at Insight Out Conf on April 11. Register free.

Insights hub solutions

Analyze data

Uncover deep customer insights with fast, powerful features, store insights, curate and manage insights in one searchable platform, scale research, unlock the potential of customer insights at enterprise scale.

Featured reads

Inspiration

Three things to look forward to at Insight Out

Tips and tricks

Make magic with your customer data in Dovetail

Four ways Dovetail helps Product Managers master continuous product discovery

Events and videos

© Dovetail Research Pty. Ltd.

- What is mixed methods research?

Last updated

20 February 2023

Reviewed by

Miroslav Damyanov

By blending both quantitative and qualitative data, mixed methods research allows for a more thorough exploration of a research question. It can answer complex research queries that cannot be solved with either qualitative or quantitative research .

Analyze your mixed methods research

Dovetail streamlines analysis to help you uncover and share actionable insights

Mixed methods research combines the elements of two types of research: quantitative and qualitative.

Quantitative data is collected through the use of surveys and experiments, for example, containing numerical measures such as ages, scores, and percentages.

Qualitative data involves non-numerical measures like beliefs, motivations, attitudes, and experiences, often derived through interviews and focus group research to gain a deeper understanding of a research question or phenomenon.

Mixed methods research is often used in the behavioral, health, and social sciences, as it allows for the collection of numerical and non-numerical data.

- When to use mixed methods research

Mixed methods research is a great choice when quantitative or qualitative data alone will not sufficiently answer a research question. By collecting and analyzing both quantitative and qualitative data in the same study, you can draw more meaningful conclusions.

There are several reasons why mixed methods research can be beneficial, including generalizability, contextualization, and credibility.

For example, let's say you are conducting a survey about consumer preferences for a certain product. You could collect only quantitative data, such as how many people prefer each product and their demographics. Or you could supplement your quantitative data with qualitative data, such as interviews and focus groups , to get a better sense of why people prefer one product over another.

It is important to note that mixed methods research does not only mean collecting both types of data. Rather, it also requires carefully considering the relationship between the two and method flexibility.

You may find differing or even conflicting results by combining quantitative and qualitative data . It is up to the researcher to then carefully analyze the results and consider them in the context of the research question to draw meaningful conclusions.

When designing a mixed methods study, it is important to consider your research approach, research questions, and available data. Think about how you can use different techniques to integrate the data to provide an answer to your research question.

- Mixed methods research design

A mixed methods research design is an approach to collecting and analyzing both qualitative and quantitative data in a single study.

Mixed methods designs allow for method flexibility and can provide differing and even conflicting results. Examples of mixed methods research designs include convergent parallel, explanatory sequential, and exploratory sequential.

By integrating data from both quantitative and qualitative sources, researchers can gain valuable insights into their research topic . For example, a study looking into the impact of technology on learning could use surveys to measure quantitative data on students' use of technology in the classroom. At the same time, interviews or focus groups can provide qualitative data on students' experiences and opinions.

- Types of mixed method research designs

Researchers often struggle to put mixed methods research into practice, as it is challenging and can lead to research bias. Although mixed methods research can reveal differences or conflicting results between studies, it can also offer method flexibility.

Designing a mixed methods study can be broken down into four types: convergent parallel, embedded, explanatory sequential, and exploratory sequential.

Convergent parallel

The convergent parallel design is when data collection and analysis of both quantitative and qualitative data occur simultaneously and are analyzed separately. This design aims to create mutually exclusive sets of data that inform each other.

For example, you might interview people who live in a certain neighborhood while also conducting a survey of the same people to determine their satisfaction with the area.

Embedded design

The embedded design is when the quantitative and qualitative data are collected simultaneously, but the qualitative data is embedded within the quantitative data. This design is best used when you want to focus on the quantitative data but still need to understand how the qualitative data further explains it.

For instance, you may survey students about their opinions of an online learning platform and conduct individual interviews to gain further insight into their responses.

Explanatory sequential design

In an explanatory sequential design, quantitative data is collected first, followed by qualitative data. This design is used when you want to further explain a set of quantitative data with additional qualitative information.

An example of this would be if you surveyed employees at a company about their satisfaction with their job and then conducted interviews to gain more information about why they responded the way they did.

Exploratory sequential design

The exploratory sequential design collects qualitative data first, followed by quantitative data. This type of mixed methods research is used when the goal is to explore a topic before collecting any quantitative data.

An example of this could be studying how parents interact with their children by conducting interviews and then using a survey to further explore and measure these interactions.

Integrating data in mixed methods studies can be challenging, but it can be done successfully with careful planning.

No matter which type of design you choose, understanding and applying these principles can help you draw meaningful conclusions from your research.

- Strengths of mixed methods research

Mixed methods research designs combine the strengths of qualitative and quantitative data, deepening and enriching qualitative results with quantitative data and validating quantitative findings with qualitative data. This method offers more flexibility in designing research, combining theory generation and hypothesis testing, and being less tied to disciplines and established research paradigms.

Take the example of a study examining the impact of exercise on mental health. Mixed methods research would allow for a comprehensive look at the issue from different angles.

Researchers could begin by collecting quantitative data through surveys to get an overall view of the participants' levels of physical activity and mental health. Qualitative interviews would follow this to explore the underlying dynamics of participants' experiences of exercise, physical activity, and mental health in greater detail.

Through a mixed methods approach, researchers could more easily compare and contrast their results to better understand the phenomenon as a whole.

Additionally, mixed methods research is useful when there are conflicting or differing results in different studies. By combining both quantitative and qualitative data, mixed methods research can offer insights into why those differences exist.

For example, if a quantitative survey yields one result while a qualitative interview yields another, mixed methods research can help identify what factors influence these differences by integrating data from both sources.

Overall, mixed methods research designs offer a range of advantages for studying complex phenomena. They can provide insight into different elements of a phenomenon in ways that are not possible with either qualitative or quantitative data alone. Additionally, they allow researchers to integrate data from multiple sources to gain a deeper understanding of the phenomenon in question.

- Challenges of mixed methods research

Mixed methods research is labor-intensive and often requires interdisciplinary teams of researchers to collaborate. It also has the potential to cost more than conducting a stand alone qualitative or quantitative study .

Interpreting the results of mixed methods research can be tricky, as it can involve conflicting or differing results. Researchers must find ways to systematically compare the results from different sources and methods to avoid bias.

For example, imagine a situation where a team of researchers has employed an explanatory sequential design for their mixed methods study. After collecting data from both the quantitative and qualitative stages, the team finds that the two sets of data provide differing results. This could be challenging for the team, as they must now decide how to effectively integrate the two types of data in order to reach meaningful conclusions. The team would need to identify method flexibility and be strategic when integrating data in order to draw meaningful conclusions from the conflicting results.

- Advanced frameworks in mixed methods research

Mixed methods research offers powerful tools for investigating complex processes and systems, such as in health and healthcare.

Besides the three basic mixed method designs—exploratory sequential, explanatory sequential, and convergent parallel—you can use one of the four advanced frameworks to extend mixed methods research designs. These include multistage, intervention, case study , and participatory.

This framework mixes qualitative and quantitative data collection methods in stages to gather a more nuanced view of the research question. An example of this is a study that first has an online survey to collect initial data and is followed by in-depth interviews to gain further insights.

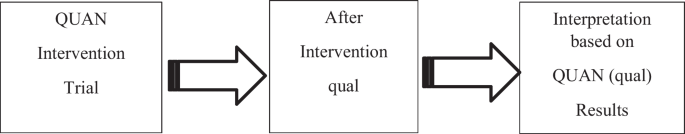

Intervention

This design involves collecting quantitative data and then taking action, usually in the form of an intervention or intervention program. An example of this could be a research team who collects data from a group of participants, evaluates it, and then implements an intervention program based on their findings .

This utilizes both qualitative and quantitative research methods to analyze a single case. The researcher will examine the specific case in detail to understand the factors influencing it. An example of this could be a study of a specific business organization to understand the organizational dynamics and culture within the organization.

Participatory

This type of research focuses on the involvement of participants in the research process. It involves the active participation of participants in formulating and developing research questions, data collection, and analysis.

An example of this could be a study that involves forming focus groups with participants who actively develop the research questions and then provide feedback during the data collection and analysis stages.

The flexibility of mixed methods research designs means that researchers can choose any combination of the four frameworks outlined above and other methodologies , such as convergent parallel, explanatory sequential, and exploratory sequential, to suit their particular needs.

Through this method's flexibility, researchers can gain multiple perspectives and uncover differing or even conflicting results when integrating data.

When it comes to integration at the methods level, there are four approaches.

Connecting involves collecting both qualitative and quantitative data during different phases of the research.

Building involves the collection of both quantitative and qualitative data within a single phase.

Merging involves the concurrent collection of both qualitative and quantitative data.

Embedding involves including qualitative data within a quantitative study or vice versa.

- Techniques for integrating data in mixed method studies

Integrating data is an important step in mixed methods research designs. It allows researchers to gain further understanding from their research and gives credibility to the integration process. There are three main techniques for integrating data in mixed methods studies: triangulation protocol, following a thread, and the mixed methods matrix.

Triangulation protocol

This integration method combines different methods with differing or conflicting results to generate one unified answer.

For example, if a researcher wanted to know what type of music teenagers enjoy listening to, they might employ a survey of 1,000 teenagers as well as five focus group interviews to investigate this. The results might differ; the survey may find that rap is the most popular genre, whereas the focus groups may suggest rock music is more widely listened to.

The researcher can then use the triangulation protocol to come up with a unified answer—such as that both rap and rock music are popular genres for teenage listeners.

Following a thread

This is another method of integration where the researcher follows the same theme or idea from one method of data collection to the next.

A research design that follows a thread starts by collecting quantitative data on a specific issue, followed by collecting qualitative data to explain the results. This allows whoever is conducting the research to detect any conflicting information and further look into the conflicting information to understand what is really going on.

For example, a researcher who used this research method might collect quantitative data about how satisfied employees are with their jobs at a certain company, followed by qualitative interviews to investigate why job satisfaction levels are low. They could then use the results to explore any conflicting or differing results, allowing them to gain a deeper understanding of job satisfaction at the company.

By following a thread, the researcher can explore various research topics related to the original issue and gain a more comprehensive view of the issue.

Mixed methods matrix

This technique is a visual representation of the different types of mixed methods research designs and the order in which they should be implemented. It enables researchers to quickly assess their research design and adjust it as needed.

The matrix consists of four boxes with four different types of mixed methods research designs: convergent parallel, explanatory sequential, exploratory sequential, and method flexibility.

For example, imagine a researcher who wanted to understand why people don't exercise regularly. To answer this question, they could use a convergent parallel design, collecting both quantitative (e.g., survey responses) and qualitative (e.g., interviews) data simultaneously.

If the researcher found conflicting results, they could switch to an explanatory sequential design and collect quantitative data first, then follow up with qualitative data if needed. This way, the researcher can make adjustments based on their findings and integrate their data more effectively.

Mixed methods research is a powerful tool for understanding complex research topics. Using qualitative and quantitative data in one study allows researchers to understand their subject more deeply.

Mixed methods research designs such as convergent parallel, explanatory sequential, and exploratory sequential provide method flexibility, enabling researchers to collect both types of data while avoiding the limitations of either approach alone.

However, it's important to remember that mixed methods research can produce differing or even conflicting results, so it's important to be aware of the potential pitfalls and take steps to ensure that data is being correctly integrated. If used effectively, mixed methods research can offer valuable insight into topics that would otherwise remain largely unexplored.

What is an example of mixed methods research?

An example of mixed methods research is a study that combines quantitative and qualitative data. This type of research uses surveys, interviews, and observations to collect data from multiple sources.

Which sampling method is best for mixed methods?

It depends on the research objectives, but a few methods are often used in mixed methods research designs. These include snowball sampling, convenience sampling, and purposive sampling. Each method has its own advantages and disadvantages.

What is the difference between mixed methods and multiple methods?

Mixed methods research combines quantitative and qualitative data in a single study. Multiple methods involve collecting data from different sources, such as surveys and interviews, but not necessarily combining them into one analysis. Mixed methods offer greater flexibility but can lead to differing or conflicting results when integrating data.

Get started today

Go from raw data to valuable insights with a flexible research platform

Editor’s picks

Last updated: 21 December 2023

Last updated: 16 December 2023

Last updated: 6 October 2023

Last updated: 17 February 2024

Last updated: 5 March 2024

Last updated: 19 November 2023

Last updated: 15 February 2024

Last updated: 11 March 2024

Last updated: 12 December 2023

Last updated: 6 March 2024

Last updated: 10 April 2023

Last updated: 20 December 2023

Latest articles

Related topics, log in or sign up.

Get started for free

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- Qualitative vs. Quantitative Research | Differences, Examples & Methods

Qualitative vs. Quantitative Research | Differences, Examples & Methods

Published on April 12, 2019 by Raimo Streefkerk . Revised on June 22, 2023.

When collecting and analyzing data, quantitative research deals with numbers and statistics, while qualitative research deals with words and meanings. Both are important for gaining different kinds of knowledge.

Common quantitative methods include experiments, observations recorded as numbers, and surveys with closed-ended questions.

Quantitative research is at risk for research biases including information bias , omitted variable bias , sampling bias , or selection bias . Qualitative research Qualitative research is expressed in words . It is used to understand concepts, thoughts or experiences. This type of research enables you to gather in-depth insights on topics that are not well understood.

Common qualitative methods include interviews with open-ended questions, observations described in words, and literature reviews that explore concepts and theories.

Table of contents

The differences between quantitative and qualitative research, data collection methods, when to use qualitative vs. quantitative research, how to analyze qualitative and quantitative data, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about qualitative and quantitative research.

Quantitative and qualitative research use different research methods to collect and analyze data, and they allow you to answer different kinds of research questions.

Quantitative and qualitative data can be collected using various methods. It is important to use a data collection method that will help answer your research question(s).

Many data collection methods can be either qualitative or quantitative. For example, in surveys, observational studies or case studies , your data can be represented as numbers (e.g., using rating scales or counting frequencies) or as words (e.g., with open-ended questions or descriptions of what you observe).

However, some methods are more commonly used in one type or the other.

Quantitative data collection methods

- Surveys : List of closed or multiple choice questions that is distributed to a sample (online, in person, or over the phone).

- Experiments : Situation in which different types of variables are controlled and manipulated to establish cause-and-effect relationships.

- Observations : Observing subjects in a natural environment where variables can’t be controlled.

Qualitative data collection methods

- Interviews : Asking open-ended questions verbally to respondents.

- Focus groups : Discussion among a group of people about a topic to gather opinions that can be used for further research.

- Ethnography : Participating in a community or organization for an extended period of time to closely observe culture and behavior.

- Literature review : Survey of published works by other authors.

A rule of thumb for deciding whether to use qualitative or quantitative data is:

- Use quantitative research if you want to confirm or test something (a theory or hypothesis )

- Use qualitative research if you want to understand something (concepts, thoughts, experiences)

For most research topics you can choose a qualitative, quantitative or mixed methods approach . Which type you choose depends on, among other things, whether you’re taking an inductive vs. deductive research approach ; your research question(s) ; whether you’re doing experimental , correlational , or descriptive research ; and practical considerations such as time, money, availability of data, and access to respondents.

Quantitative research approach

You survey 300 students at your university and ask them questions such as: “on a scale from 1-5, how satisfied are your with your professors?”

You can perform statistical analysis on the data and draw conclusions such as: “on average students rated their professors 4.4”.

Qualitative research approach

You conduct in-depth interviews with 15 students and ask them open-ended questions such as: “How satisfied are you with your studies?”, “What is the most positive aspect of your study program?” and “What can be done to improve the study program?”

Based on the answers you get you can ask follow-up questions to clarify things. You transcribe all interviews using transcription software and try to find commonalities and patterns.

Mixed methods approach

You conduct interviews to find out how satisfied students are with their studies. Through open-ended questions you learn things you never thought about before and gain new insights. Later, you use a survey to test these insights on a larger scale.

It’s also possible to start with a survey to find out the overall trends, followed by interviews to better understand the reasons behind the trends.

Qualitative or quantitative data by itself can’t prove or demonstrate anything, but has to be analyzed to show its meaning in relation to the research questions. The method of analysis differs for each type of data.

Analyzing quantitative data

Quantitative data is based on numbers. Simple math or more advanced statistical analysis is used to discover commonalities or patterns in the data. The results are often reported in graphs and tables.

Applications such as Excel, SPSS, or R can be used to calculate things like:

- Average scores ( means )

- The number of times a particular answer was given

- The correlation or causation between two or more variables

- The reliability and validity of the results

Analyzing qualitative data

Qualitative data is more difficult to analyze than quantitative data. It consists of text, images or videos instead of numbers.

Some common approaches to analyzing qualitative data include:

- Qualitative content analysis : Tracking the occurrence, position and meaning of words or phrases

- Thematic analysis : Closely examining the data to identify the main themes and patterns

- Discourse analysis : Studying how communication works in social contexts

If you want to know more about statistics , methodology , or research bias , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Chi square goodness of fit test

- Degrees of freedom

- Null hypothesis

- Discourse analysis

- Control groups

- Mixed methods research

- Non-probability sampling

- Quantitative research

- Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Research bias

- Rosenthal effect

- Implicit bias

- Cognitive bias

- Selection bias

- Negativity bias

- Status quo bias

Quantitative research deals with numbers and statistics, while qualitative research deals with words and meanings.

Quantitative methods allow you to systematically measure variables and test hypotheses . Qualitative methods allow you to explore concepts and experiences in more detail.

In mixed methods research , you use both qualitative and quantitative data collection and analysis methods to answer your research question .

The research methods you use depend on the type of data you need to answer your research question .

- If you want to measure something or test a hypothesis , use quantitative methods . If you want to explore ideas, thoughts and meanings, use qualitative methods .

- If you want to analyze a large amount of readily-available data, use secondary data. If you want data specific to your purposes with control over how it is generated, collect primary data.

- If you want to establish cause-and-effect relationships between variables , use experimental methods. If you want to understand the characteristics of a research subject, use descriptive methods.

Data collection is the systematic process by which observations or measurements are gathered in research. It is used in many different contexts by academics, governments, businesses, and other organizations.

There are various approaches to qualitative data analysis , but they all share five steps in common:

- Prepare and organize your data.

- Review and explore your data.

- Develop a data coding system.

- Assign codes to the data.

- Identify recurring themes.

The specifics of each step depend on the focus of the analysis. Some common approaches include textual analysis , thematic analysis , and discourse analysis .

A research project is an academic, scientific, or professional undertaking to answer a research question . Research projects can take many forms, such as qualitative or quantitative , descriptive , longitudinal , experimental , or correlational . What kind of research approach you choose will depend on your topic.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Streefkerk, R. (2023, June 22). Qualitative vs. Quantitative Research | Differences, Examples & Methods. Scribbr. Retrieved April 2, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/qualitative-quantitative-research/

Is this article helpful?

Raimo Streefkerk

Other students also liked, what is quantitative research | definition, uses & methods, what is qualitative research | methods & examples, mixed methods research | definition, guide & examples, "i thought ai proofreading was useless but..".

I've been using Scribbr for years now and I know it's a service that won't disappoint. It does a good job spotting mistakes”

Quantitative, Qualitative, and Mixed-Methods Research: Home

Quantitative, qualitative, and mixed-methods research.

Depending on the philosophy of the researcher, the nature of the data, and how it is collected, behavioral science can be classified into qualitative, quantitative, or mixed methods research. Below are descriptions of each method.

Quantitative Research

Collects numerical data, such as frequencies or scores to focus on cause-and-effect relationships among variables

Variables and research methodologies are defined in advance by theories and hypotheses derived from other theories. These remain unchanged throughout the research process.

The researcher tries to achieve objectivity by distancing himself or herself from the research, not allowing himself or herself to be emotionally involved.

The researcher mostly studies research in artificial or less than its natural setting, and manipulates behavior as opposed to studying the behavior in its natural context.

The researcher tries to maintain internal validity and focuses on average behavior or thoughts of people in a population

Qualitative Research

Where researchers collect non-numerical information, such as descriptions of behavioral phenomena, how people experience or interpret events, and/or answers to participants' open-ended responses.

The researcher's variables andmethods used come from the researcher's experiences and can be modified as the research progresses.

The researcher is involved and his or her experiences are valuable as well as the participants' experiences.

The researcher studies behavior as it naturally happens in the natural context.

The researcher tries to maximize ecological validity.

The researcher focuses on similarities and differences in experiences and how people interpret them.

Mixed-Methods Research

Involves both quantitative and qualitative components.

The researcher specifies in advance the types of information necessary to accomplish the study's goals.

The researcher needs to carefully consider the order in which the data types will be collected and the selection criteria for participants in the various parts of the study (e.g., which people will participate in the qualitative assessment if a sub-selection of participants will be involved).

Involves development (where the researcher uses one method to inform data collection or analysis with another method) initiation (where unexpected results change protocol in the other method), corroboration (where consistency is evaluated and compared between methods), and elaboration (where one method is used to expand on the results of the other method).

Whitley, B. E. & Kite, M. E. (2013). Principles of research in behavioral science (3rd ed.). Routledge.

- Last Updated: Sep 2, 2020 12:29 PM

- URL: https://library.divinemercy.edu/research-types

- Frontiers in Psychology

- Quantitative Psychology and Measurement

- Research Topics

Best Practice Approaches for Mixed Methods Research in Psychological Science - Volume II

Total Downloads

Total Views and Downloads

About this Research Topic

Having started as a small movement in the 1980’s, the study of mixed methods research burst onto the scene around the beginning of the second millennium. After decades of intense dispute between supporters of the qualitative perspective and their quantitative counterparts—with both sides having grown deeply ...

Keywords : Symmetry, Quantitizing, Qualitizing, Record Transformation, Qual-Quan Integration

Important Note : All contributions to this Research Topic must be within the scope of the section and journal to which they are submitted, as defined in their mission statements. Frontiers reserves the right to guide an out-of-scope manuscript to a more suitable section or journal at any stage of peer review.

Topic Editors

Topic coordinators, recent articles, submission deadlines, participating journals.

Manuscripts can be submitted to this Research Topic via the following journals:

total views

- Demographics

No records found

total views article views downloads topic views

Top countries

Top referring sites, about frontiers research topics.

With their unique mixes of varied contributions from Original Research to Review Articles, Research Topics unify the most influential researchers, the latest key findings and historical advances in a hot research area! Find out more on how to host your own Frontiers Research Topic or contribute to one as an author.

College of Education and Human Development

Family Social Science

Methods: mixed methods, quantitative methods

The integration of quantitative and qualitative methods in family science allows researchers to explore the complexity of family life, providing a more comprehensive and nuanced understanding that can inform both theory and practice.

Michelle Pasco Michelle Pasco

- Assistant Professor

- she/her/hers

- [email protected]

Michelle Pasco received a PhD in Family and Human Development at Arizona State University and before joining the University of Minnesota was a Postdoctoral Research Scholar working on the Arizona Youth Identity Project.

Timothy Piehler Timothy Piehler

- Associate Professor

- 612-301-1484

- [email protected]

Advising statement My program of research is focused on developing and evaluating preventive interventions in the areas of youth mental health and substance use.

Xiaoran Sun Xiaoran Sun

Advising statement As a developmental and family psychologist, I conduct research on the interplay between family systems processes and well-being across adolescence and young adulthood, situated in the larger socio-ecological context--including the…

- Study Protocol

- Open access

- Published: 26 March 2024

The effect of a midwifery continuity of care program on clinical competence of midwifery students and delivery outcomes: a mixed-methods protocol

- Fatemeh Razavinia ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-6827-509X 1 , 2 ,

- Parvin Abedi ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-6980-0693 3 ,

- Mina Iravani ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-8854-1738 4 ,

- Eesa Mohammadi ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-6169-9829 5 ,

- Bahman Cheraghian ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-5446-6998 6 ,

- Shayesteh Jahanfar ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-6149-1067 7 &

- Mahin Najafian ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-6649-3931 8

BMC Medical Education volume 24 , Article number: 338 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

113 Accesses

Metrics details

The midwifery continuity of care model is one of the care models that have not been evaluated well in some countries including Iran. We aimed to assess the effect of a program based on this model on the clinical competence of midwifery students and delivery outcomes in Ahvaz, Iran.

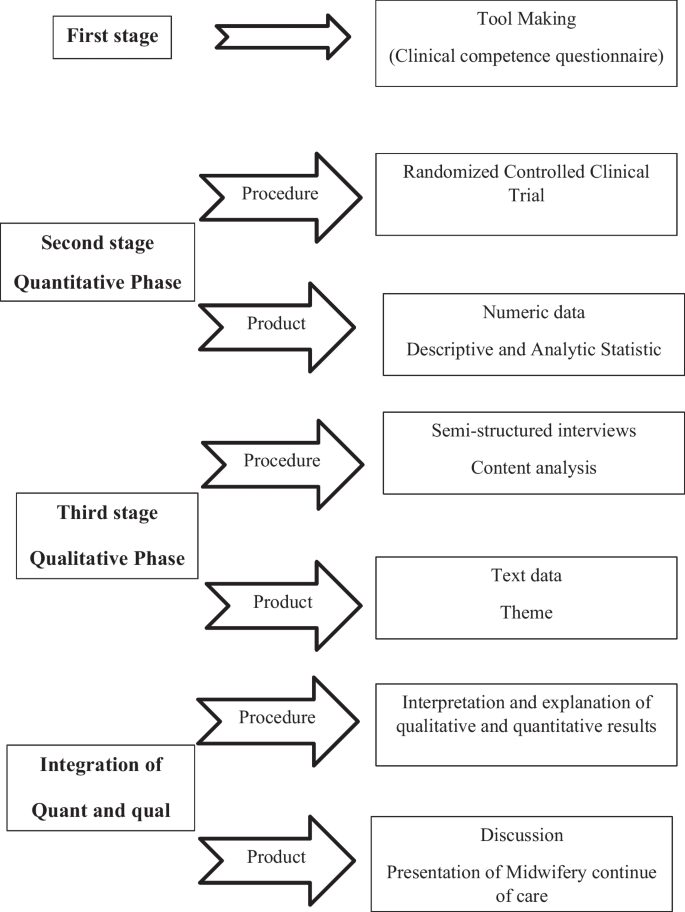

This sequential embedded mixed-methods study will include a quantitative and a qualitative phase. In the first stage, based on the Iranian midwifery curriculum and review of seminal midwifery texts, a questionnaire will be developed to assess midwifery students’ clinical competence. Then, in the second stage, the quantitative phase (randomized clinical trial) will be conducted to see the effect of continuity of care provided by students on maternal and neonatal outcomes. In the third stage, a qualitative study (conventional content analysis) will be carried out to investigate the students’ and mothers’ perception of continuity of care. Finally, the results of the quantitative and qualitative phases will be integrated.

According to the nature of the study, the findings of this research can be effectively used in providing conventional midwifery services in public centers and in midwifery education.

Trial registration

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Ahvaz Jundishapur University of Medical Sciences (IR.AJUMS.REC.1401.460). Also, the study protocol was registered in the Iranian Registry for Randomized Controlled Trials (IRCT20221227056938N1).

Peer Review reports

Providing quality services to pregnant women has been recommended to all countries to achieve the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) (Goals 3, 4 and 5) [ 1 ]. There are different care methods to maintain maternal and neonatal health during pregnancy and postpartum [ 1 ]. One of these care models is continuity of care that can be provided by a midwife or an obstetrician.

Midwifery continuity of care is a relationship-based care provided by a midwife who can be supported by one to three more midwives. They provide planned care for a woman during pregnancy, labor, birth, and the early postpartum period up to 6 weeks after delivery [ 2 ].

Continuity of midwifery care has become a global effort to enable women to have access to high-quality maternity care and delivery services [ 3 ]. As a result, many service providers today are transitioning to a continuous care model [ 4 ], and they have considered continuous care to be necessary for realizing women's rights [ 5 ]. Also, continuous midwifery care is known as the gold standard in maternity care to achieve excellent results for women [ 5 , 6 ]. In order to strengthen midwifery services to achieve global health goals in 2015, the World Health Organization (WHO) proposed a midwife-led continuous care model [ 7 ].

Countries use different midwifery care models. In Iran, for example, primary health services that are specific to pregnant mothers are provided in public health centers by midwives working in the network system and in compliance with the level of services and the referral system [ 8 ].

In general, midwifery continuous care not only has an important impact on a wide range of health and clinical outcomes for mothers and neonates but also brings about economic consequences for the health system [ 2 , 9 ]. This care model is useful for healthcare professionals as well [ 10 ], and it has improved the job satisfaction of midwives [ 11 ]. The midwife is the main guide in planning, organizing and providing care to a woman from the beginning of pregnancy to the postpartum period [ 12 ]. In 2011, in order to increase job motivation and satisfaction, promote retention of the midwifery workforce [ 13 ], and alleviate the shortage of workforce at the international level [ 14 ], the Nursing and Midwifery Advisory Center recommended using midwifery students (at the bedside and to perform midwifery work) to overcome this problem.

Providing high quality care requires enhancing the clinical competence of the professionals [ 4 ]. There is a close relationship between the concept of patient care quality and clinical competence. Therefore, clinical competence is of unique importance in midwifery practice [ 15 ]. As a result, in order to achieve quality patient care, midwifery professionals need to train students to become workforce with clinical competence in order to provide quality care in the health system. WHO defined clinical competence as a level of performance that demonstrates the effective application of knowledge, skills, and judgment [ 16 ].

A previous study showed that clinical competence of midwives plays an important role in managing the process of providing care, achieving care goals, and improving the quality of midwifery services [ 17 ]. In other words, the graduates of this field must have an acceptable level of clinical and professional skills in performing midwifery duties so that the health of mothers, children, and ultimately the community can be improved.

In Iran, prenatal care and the care during labor, delivery and postpartum are not continuous, and a new health provider may take the responsibility of care at any stage. This fragmented care may negatively affect the pregnancy outcomes and increase the rate of cesarean section [ 18 ]. Furthermore, the results of some studies in Iran indicate that the clinical competence obtained by midwifery students is far from optimal and that they do not acquire the necessary skills and abilities at the end of their studies [ 19 ]. Farrokhi et al. showed that the performance quality of 70% of midwives is average, and only 18.5% of them have good quality performance [ 20 ]. Several factors play a role in acquiring, maintaining and improving clinical competence [ 21 ]. There are a number of solutions that can increase the clinical competence of midwifery students, and one is the use of different care models such as the continuity of care model. The continuity of care model allows students to develop their midwifery knowledge, skills, and values individually [ 22 ]. Despite the strong foundation of midwifery in Iran, midwifery care models have not yet been tested. Some studies have reported that the quality of services provided during pregnancy, delivery and after delivery in Iran is poor to moderate. Also, these studies emphasize the necessity of a paradigm shift for better quality care and greater satisfaction of mothers, and they consider lack of continuity of care as the reason for the increase in unnecessary cesarean sections [ 23 , 24 , 25 ]. Moreover, the lack of qualified and experienced workforce has led to low quality health services, including midwifery care, and an increase in the economic burden of health. In Iran, no study has yet been conducted to investigate the effect of the midwifery continuity of care model on the students’ clinical competence and pregnancy outcomes. Given the importance of this topic, using a mixed-methods study design, we aimed to assess the effect of a midwifery continuity of care program on the clinical competence of midwifery students and pregnancy outcomes in Ahvaz, Iran.