Importance of Daily Oral Care Essay

Introduction, how oral health affects overall health, oral bacteria entering the bloodstream, the mouth is a mirror into person’s health, links between oral health and following diseases, common oral health conditions that may affect the elderly, daily oral hygiene for long-term care residents, daily oral hygiene modifications.

Maintaining oral health is a major issue in the medical field. It is vital in keeping healthy on the whole, along with an imperative effect on the personality of each individual. Keeping good oral health practices may help minimize deadly diseases, and reduce risks of serious illnesses. Oral health involves keeping the mouth, gums, and teeth hygienic, by taking proper care of them and giving them due attention.

Prevention of gums from cavities and diseases is the chief aspect of good oral health. This can be done by regular cleaning, brushing, and flossing of the teeth on a daily basis, which would help prevent bacterial infections and the emergence of plaque. Plaque is caused by constant bacterial action due to a lack of oral hygiene. This bacteria infects the teeth by forming layers upon layers, appearing in the form of tartar.

The bacteria from the mouth, if not removed, can enter the bloodstream, and affect overall health by aggravating pre-existing diseases.

The mouth of a person reflects his personality greatly because it is the main focus while looking at other people during a conversation. It depicts the personal hygiene one possesses and is indicative of the liking for oral hygiene.

Poor oral health has been found linked to many diseases- the relation lies in the fact that the unhygienic conditions of the mouth aggravate any bacterial infections that are present in the body.

Pneumonia is a very common cause of death in elderly nursing home residents. The dental plaque present gives rise to pneumonia-causing bacteria, which get into the respiratory tract through silent aspiration (Jurasek, 2002).

Candidiasis

Candidiasis is a fungal infection that is caused by the yeast Candida Albicans. Denture wearers suffer most from the disease, because of a lack of oral hygiene. It is essential to remove dentures and keep the mouth clean especially after mealtimes (American Dental Association, 2009).

In diabetic patients, oral candidiasis is more prevalent, which can be treated with antifungal medicines. But the most important element is to keep oral hygiene so that such an instance does not initiate. The wounds of diabetic patients take longer to heal, which can affect overall health too.

Heart Disease

The bacteria that affect the gums due to unhygienic conditions of the mouth may enter the bloodstream and also affect the arteries, according to current research. Studies have shown that bacteria infecting the gums can now travel freely throughout the body. The bacteria invade the coronary arteries, causing blockage, and clotting. Another link of oral hygiene to heart disease is the formation of plaque, which causes swelling up of the arteries (American Academy of Periodontology, 2008).

Stroke is also caused due to the same aforementioned reason.

Respiratory Infections

Respiratory infections occur when the bacteria from the gums enter the bloodstream and enter the lungs. Usually, respiratory infections are caused by aspiration or inhaling, but recent studies have shown the bacteria to enter the bloodstream through gum infections. The lower respiratory tract is affected by bacterial invasion.

Bacterial Endocarditis

Bacterial endocarditis is a heart disease in which the valves or inner lining of the heart is affected by germs. Good daily oral hygiene habits may prevent endocarditis, plus, a visit to a dentist every six months, and regular brushing and flossing may also help reduce risks of dental diseases, which may lead to fatal diseases such as the aforementioned (“Infective Endocarditis”, 2009).

Low birth weight and Premature Babies

Premature babies may also result from periodontal disease. When bacteria from the mouth enter the bloodstream, the body produces prostaglandin to fight the bacteria, which causes muscle contraction, resulting in early labor. The bacterium Pgingivalis infects the placenta, which may affect the growth and development of the fetus. Inflammatory chemicals may also be produced in a pregnant woman’s body.

Elderly people may suffer from dry mouth or xerostomia, because of the therapies they are going through. Patients, who are undergoing cancer therapies and the like, develop dry mouth because of the intensity of the medications. They may also be suffering from dry mouth as a result of some other diseases they may be suffering from, like arthritis, bone marrow transplantation, and neurological diseases.

Periodontal Disease

Periodontal diseases occur as a result of bacterial infections, which give rise to root surface caries too.

Root Surface Caries

Root surface caries are seen in these patients because of the long periods they are hospitalized, and are not given the medical attention they may need individually.

Oral Ulcerations

Oral ulcers are additionally a cause of bacterial activity in the inner lining of the mouth, which gives rise to painful blisters and swelling; they are termed oral ulcers.

Brushing Daily

It is essential for every individual to brush teeth regularly, at least once daily, if not twice, to prevent gum diseases. For long-term care residents, because they are being rendered treatment for the disease and may neglect to keep oral hygiene, it is specifically crucial to pay attention to cleanliness. The hospital conditions may also be such that patients are uncomfortable, and may not pay heed to the importance of daily brushing.

Flossing regularly will help remove bacterial films from teeth.

Mouth Rinsing

Mouth rinsing after meal intake is also essential for keeping the gums free of food particles which may enhance bacterial growth.

Sugar-free Chewing gum

The sugars in food tend to stick to the teeth, giving bacteria the chance to act on them, which gradually cause plaque, and eventually, tartar. Thus sugar-free chewing gum would be a good substitute for regular gum, to prohibit infection.

Denture Care

If dentures are worn, they need to be removed regularly for cleaning, and then restored. Dentures need to be washed regularly and the gums need cleaning so that minimal bacterial growths take place to aggravate the disease that already subsists.

OT/PT Consult

Oral hygienic maintenance can be advised by the physician, to the patients. Patients are told the importance of keeping oral hygiene and maintaining it. Consulting always helps, because patients can get convinced verbally, about the importance of keeping the mouth clean, and of brushing teeth. Brushing teeth is the most common and best way to maintain oral health. By tooth brushing, the bacterial film which forms on teeth is removed. This action keeps the buccal cavity protected from any bacterial infections.

One way to improve and make more effective the brushing of teeth is to modify the toothbrush, so as to reach far-reaching areas while cleaning. Duct tape is applied to the handle of the toothbrush, which causes enlargements in the brush. A larger handle helps grasp the toothbrush, which would help in proper cleaning of the teeth (Spratt, et.al, 1997).

Bicycle Handle

The size of the handle of the toothbrush can be increased easily with some household tricks, like the use of a bicycle handle. Floss is helpful in removing plaque from the teeth, and regular flossing is recommended for oral healthcare, even to normal healthy people.

Electric Brush

Electric toothbrushes have also been designed for ease of cleaning the teeth. The electric toothbrush has an oscillating head, due to which it is also called the rotary brush. It has not been found to cleanse better than the ordinary manual brush, however, it is a good modification for the elderly people who would prefer keeping from the trouble of manual brushing.

Another oral hygiene device that may be used is a disposable applicator that attaches to the fingertip of the individual using it. The finger acts like a handle that controls the applicator while it cleanses the gums and oral cavities of the mouth. The gums can be massaged this way too, along with the teeth and interproximal areas. The shape of the applicator is such that it covers the fingertip smoothly, and there is an adhesive at the base, which ensures a good grip. On the top layer, are small bristles that help in the cleaning process.

Simple steps in performing daily oral care in nursing homes may reduce hospital stays and improve the overall quality of living

Simple steps in brushing teeth may help maintain good oral health, which is imperative to the overall health of residents in nursing care. It is apparent that lack of oral hygiene may affect the overall health of individuals, and may worsen the conditions of those who are already suffering from some disease. Daily brushing and mouth cleaning after mealtimes may help reduce risks of disease and may improve the quality of life of individuals who are seeking treatment in the hospital.

Summary of why oral care is imperative to the overall health of residents

Oral care needs to be maintained if good general health is sought because both are interlinked. Residents need to take special care because of their pre-existing illness and have to ensure that their carelessness in oral hygiene will not cause further complications in the disease.

- American Academy of Periodontology (2008).

- Infective Endocarditis (2009) Reference: Wilson W., et al. Prevention of infective endocarditis: Guidelines from the American Heart Association. Circulation, 2007; 115(8). Web.

- Jurasek, G. (2002). Oral Health Affects Pneumonia Riskin the Elderly.

- Spratt, J., Hawley, R. & Hoye, R. (1997). Home Health Care. Principles and Practices. FL 33483, St Lucie Press, 1997, hardback, 388 pp.

- International Marketing Plan in Saudi Arabia

- Health Behaviours Among Adolescents in Saudi Arabia

- Psychology: Chewing Gum' Negative Effects

- Back Pain for the Dentist

- Putting Teeth in Health Care Reform

- Dental Providers Should Be Going Above and Beyond

- COVID-19 Awareness Precautions in King Saud University

- Health Care Providers and Professionals. Nurses and Dentists: A Comparison

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2022, March 5). Importance of Daily Oral Care. https://ivypanda.com/essays/importance-of-daily-oral-care/

"Importance of Daily Oral Care." IvyPanda , 5 Mar. 2022, ivypanda.com/essays/importance-of-daily-oral-care/.

IvyPanda . (2022) 'Importance of Daily Oral Care'. 5 March.

IvyPanda . 2022. "Importance of Daily Oral Care." March 5, 2022. https://ivypanda.com/essays/importance-of-daily-oral-care/.

1. IvyPanda . "Importance of Daily Oral Care." March 5, 2022. https://ivypanda.com/essays/importance-of-daily-oral-care/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Importance of Daily Oral Care." March 5, 2022. https://ivypanda.com/essays/importance-of-daily-oral-care/.

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

Why Oral Hygiene Is Crucial to Your Overall Health

Gum disease has been associated with a range of health conditions, including diabetes, heart disease, dementia and more. Here’s what experts say you can do to manage the risk.

By Hannah Seo

The inside of your mouth is the perfect place for bacteria to thrive: It’s dark, it’s warm, it’s wet and the foods and drinks you consume provide nutrients for them to eat.

But when the harmful bacteria build up around your teeth and gums, you’re at risk of developing periodontal (or gum) disease , experts say, which is an infection and inflammation in the gums and bone that surround your teeth.

And such conditions in your mouth may influence the rest of your body, said Kimberly Bray, a professor of dental hygiene at the University of Missouri-Kansas City.

A growing yet limited body of research , for instance, has found that periodontal disease is associated with a range of health conditions including diabetes, heart disease, respiratory infections and dementia.

Exactly how oral bacteria affect your overall health is still poorly understood, Dr. Bray said, since the existing research is limited and no studies have established cause-and-effect.

But some conditions are more associated with oral health than others, experts say. Here is what we know.

The health issues linked with oral health

About 47 percent of people aged 30 years and older in the United States have some form of periodontal disease, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

In its early stages, called gingivitis, the gums may become swollen, red or tender and may bleed easily. If left untreated, gingivitis may escalate to periodontitis, a more serious form of the disease where gums can recede, bone can be lost, and teeth may become loose or even fall out.

With periodontitis, bacteria and their toxic byproducts can move from the surface of the gums and teeth and into the bloodstream, where they can spread to different organs, said Ananda P. Dasanayake, a professor of epidemiology at the New York University College of Dentistry.

This can happen during a dental cleaning or flossing, or if you have a cut or wound inside your mouth, he said.

If you have inflammation in the mouth that is untreated, some of the proteins responsible for that inflammation can spread throughout the body, Dr. Bray said, and potentially damage other organs.

Of all the associations between oral health and disease, the one with the most evidence is between periodontal disease and diabetes, Dr. Bray said. And the two conditions seem to have a two-way relationship , she added: Periodontal disease seems to increase the risk for diabetes, and vice versa.

Researchers have yet to understand exactly how this might work, but in one review published in 2017 , researchers wrote that the systemic inflammation caused by periodontal disease may worsen the body’s ability to signal for and respond to insulin.

In another study , published in April, scientists found that diabetics who were treated for periodontal disease saw their overall health care costs decrease by 12 to 14 percent.

“You treat periodontal disease, you improve the diabetes,” Dr. Dasanayake said.

If large amounts of bacteria from the mouth are inhaled and settle in the lungs, that can result in bacterial aspiration pneumonia , said Dr. Frank Scannapieco, a professor of oral biology at the University at Buffalo School of Dental Medicine.

This phenomenon has been observed mainly in patients who are hospitalized or older adults in nursing homes, and is a concern for those who can’t floss or brush their teeth on their own, said Dr. Martinna Bertolini, an assistant professor of dental medicine at the University of Pittsburgh School of Dental Medicine.

Preventive dental care such as with professional teeth cleanings, or periodontal treatments like antibiotic therapy, can lower the risk of developing this kind of pneumonia, Dr. Scannapieco said.

Cardiovascular disease

In a report published in 2020 , an international team of experts concluded that there is a significant link between periodontitis and heart attack, stroke, plaque buildup in the arteries, and other cardiovascular conditions.

While researchers haven’t determined how poor oral health might lead to worse heart health, some evidence suggests that periodontal bacteria from the mouth may travel to the arteries in vascular disease patients, potentially playing a role in the development of the disease.

And a 2012 statement from the American Heart Association noted that inflammation in the gums has been associated with higher levels of inflammatory proteins in the blood that have been linked with poor heart health.

Some research also suggests that better oral hygiene practices are linked with lower rates of heart disease.

For example, in a study published in 2019 , researchers reviewed the health records of nearly 250,000 healthy adults living in South Korea and found that over about 10 years, those who regularly brushed their teeth and received regular dental cleanings were less likely to have cardiovascular events than those who had poorer dental hygiene, formed more cavities, experienced tooth loss or developed periodontitis.

Pregnancy complications

A number of studies and reviews have found associations between severe periodontal disease and preterm, low birth weight babies, Dr. Dasanayake said. Though more research is needed to confirm the link.

In a 2019 review , researchers found that treating periodontal disease during pregnancy improved birth weight and reduced the risk of preterm birth and the death of the fetus or newborn.

And in a 2009 study , researchers found that oral bacteria could travel to the placenta — potentially playing a role in chorioamnionitis, a serious infection of the placenta and amniotic fluid that could lead to an early delivery, or even cause life-threatening complications if left untreated.

Research also suggests that bacteria from your mouth may activate immune cells that circulate in the blood, causing inflammation in the womb that could distress the placenta and fetal tissues.

There is longstanding research that periodontitis may induce preterm birth in animals like mice, and that treating these infections can protect against low birth weights and preterm birth.

Researchers have been increasingly interested in the role of oral health in dementia, particularly Alzheimer’s disease, Dr. Scannapieco said.

“Bacteria that are found in the mouth actually have been identified in the brain tissue of patients with Alzheimer’s,” he said, implying a potential role for them in the disease.

In a recent review , scientists noted that oral bacteria — especially those related to periodontitis — could either affect the brain directly via “infection of the central nervous system,” or indirectly by inducing “chronic systemic inflammation” that reaches the brain.

However, there’s no evidence that oral bacteria alone could cause Alzheimer’s, the review authors wrote. Rather, periodontal disease is just one “risk factor” among many for people who are predisposed to Alzheimer’s or other forms of dementia.

Other conditions

Oral bacteria have also been robustly linked with a number of other conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis and osteoporosis , Dr. Bray said. And emerging research is starting to link oral bacteria with kidney and liver disease, as well as colorectal and breast cancers .

But more research is needed to confirm all of these links, the experts said. And we still don’t know if regular dental care and periodontal treatments may help prevent or improve any of the conditions mentioned above, Dr. Scannapieco said.

What you can do

The best way to maintain good oral health is to follow the classic dental care advice , including brushing your teeth twice a day and flossing every day, Dr. Scannapieco said.

“Not all people really appreciate their oral health, and they’re only reminded of it when they have a toothache or some pain,” he added. But it’s important to be just as diligent and proactive about your oral health as you are with exercise or diet or any other aspect of well-being.

Hannah Seo is a reporting fellow for The Times, covering mental and physical health and wellness. More about Hannah Seo

Oral Health

“There is no health without oral health.” You may have heard this statement but what does it mean? The health of our mouth, or oral health, is more important than many of us may realize. It is a key indicator of overall health, which is essential to our well-being and quality of life.

Although preventable to a great extent, untreated tooth decay (or cavities) is the most common health condition worldwide. When we think about the potential consequences of untreated oral diseases including pain, reduced quality of life, lost school days, disruption to family life, and decreased work productivity, making sure our mouths stay healthy is incredibly important. [1]

What is a Healthy Mouth?

The mouth, also called the oral cavity, starts at the lips and ends at the throat. A healthy mouth and well-functioning teeth are important at all stages of life since they support human functions like breathing, speaking, and eating. In a healthy mouth, tissues are moist, odor-free, and pain-free. When we talk about a healthy mouth, we are not just talking about the teeth but also the gingival tissue (or gums) and the supporting bone, known together as the periodontium. The gingiva may vary in color from coral pink to heavily pigmented and vary in pattern and color between different people. Healthy gingiva is firm, not red or swollen, and does not bleed when brushed or flossed. A healthy mouth has no untreated tooth decay and no evidence of lumps, ulcers, or unusual color on or under the tongue, cheeks, or gums. Teeth should not be wiggly but firmly attached to the gingiva and bone. It should not hurt to chew or brush your teeth.

Throughout life, teeth and oral tissues are exposed to many environmental factors that may lead to disease and/or tooth loss. The most common oral diseases are tooth decay and periodontal disease. Good oral hygiene and regular visits to the dentist, combined with a healthy lifestyle and avoiding risks like excess sugar and smoking, help to avoid these two diseases.

Oral Health and Nutrition: What You Eat and Drink Affects Your Teeth

Just like a healthy body, a healthy smile depends on good nutrition. A balanced diet with adequate nutrients is essential for a healthy mouth and in turn, a healthy mouth supports nutritional well-being. Food choices and eating habits are important in preventing tooth decay and gingival disease.

Minerals like calcium and phosphorus contribute to dental health by protecting and rebuilding tooth enamel. [2] Enamel is the hard outer protective layer of the tooth (fun fact: enamel is the hardest substance in the human body). Eating foods high in calcium and other nutrients such as cheese , milk , plain yogurt , calcium-fortified tofu , leafy greens , and almonds may help tooth health. [2] While protein-rich foods like meat, poultry, fish, milk and eggs are great sources of phosphorus.

When it comes to a healthy smile, fruits and vegetables are also good choices since they are high in water and fiber , which balance the sugars they hold and help to clean the teeth. [2] These foods also help stimulate saliva, which helps to wash away acids and food from teeth, both neutralizing acid and protecting teeth from decay. Many fruits and vegetables also have vitamins like vitamin C , which is important for healthy gingiva and healing, and vitamin A, another key nutrient in building tooth enamel.[2]

Water is the clear winner as the best drink for your teeth—particularly fluoridated water. It helps keep your mouth clean and helps fight dry mouth. Fluoride is needed regularly throughout life to protect teeth against tooth decay. [3] Drinking water with fluoride is one of the easiest and most beneficial things you can do to help prevent cavities.

Is carbonated water a healthy choice for my teeth?

How snacking can affect your dental health

Malnutrition and oral health.

Nutrition and oral health are closely related. The World Health Organization defines malnutrition as deficiencies, excesses, or imbalances in a person’s intake of energy and/or nutrients. This means that malnutrition can be over-nutrition or undernutrition. Dental pain or missing teeth can lead to difficulty chewing or swallowing food which negatively affects nutrition. This may mean eating fewer meals or meals with lower nutritional value due to impaired oral health and increased risk of malnutrition. On the other hand, lack of proper nutrients can also negatively affect the development of the oral cavity, the progression of oral diseases and result in poor healing. [5] In this way, nutrition affects oral health, and oral health affects nutrition.

Nutrition is a major factor in infection and inflammation. [5] Inflammation is part of the body’s process of fighting against things that harm it, like infections and injuries. Although inflammation is a natural part of the body’s immune response to protect and heal the body, it can be harmful if it becomes unbalanced. In this way inflammation is a dominant factor in many chronic diseases. Periodontal diseases and obesity are risk factors involved in the onset and progression of chronic inflammation and its consequences. [6]

Oral Health and General Health

While it may appear that oral diseases only affect the mouth, their consequences can affect the rest of the body as well. There is a proven relationship between oral and general health. Many health conditions may increase the risk of oral diseases, and poor oral health can negatively affect many general health conditions and the management of those conditions. Most oral diseases share common risk factors with chronic diseases like cardiovascular disease , cancers , diabetes , and respiratory diseases. These risk factors include unhealthy diets, particularly those high in added sugar, as well as tobacco and alcohol use. [7]

Infective endocarditis (IE), an infection of the inner lining of the heart muscle, can be caused by bacteria that live on teeth. [8] Gingivitis and periodontitis are inflammatory diseases of the gingiva and supporting structures of the teeth caused by specific bacteria. There is evidence that the surface of inflamed tissue around teeth is the point of entry for the specific bacteria that cause as much as 50% of the IE cases in the U.S. annually. This means that improving oral hygiene may help in reducing the risk of developing IE. In addition, periodontal disease may be associated with heart disease and shares risk factors including tobacco use, poorly controlled diabetes , and stress . [9,10]

Oral health is an important part of prenatal care. Poor oral health during pregnancy can result in poor health outcomes for both mother and baby. For example, studies suggest that pregnant women who have periodontal disease may be more likely to have a baby that is born too early and too small. [7] Hormonal changes during pregnancy, particularly elevated levels of progesterone, increase susceptibility to periodontal disease, which includes gingivitis and periodontitis. For this reason, your dentist may recommend more frequent professional cleanings during your pregnancy.

If you are struggling with morning sickness, the stomach acid from vomiting can erode or wear away tooth enamel. To help prevent the effects of erosion, rinse your mouth with 1 teaspoon of baking soda mixed in a cup of water, then wait 30 minutes before brushing your teeth. [11]

Conditions that impact oral health

Certain conditions may also affect your oral health, including:

- Anxiety and stress. Stress is a normal human reaction that everyone experiences at one point or another. However, stress that is left unchecked can contribute to many health problems including oral health issues. While behavioral changes play a leading role in these poor oral health findings, there are certain physiological effects on the body as well. Stress creates a hormone in the body called cortisol. Spikes in this hormone can weaken the immune system and increase susceptibility to developing periodontal disease. Evidence has shown that stress reduces the flow of saliva which in turn can contribute to dental plaque formation. [12] Certain medications like antidepressants and anti-anxiety medications can also cause dry mouth, increasing risk of tooth decay. Additionally, stress may contribute to teeth grinding (or bruxism), clenching, cold sores, and canker sores.

- Osteoporosis and Paget’s Disease . Medical conditions such as osteoporosis are a fitting example of why it is so important to let your dentist know about all the medications you are taking. Certain medications like antiresorptive agents, a group of drugs that slows bone loss, can influence dental treatment decisions. That is because these medications have been associated with a rare but serious condition called osteonecrosis of the jaw (ONJ), which can damage the jawbone. Bisphosphonates (Fosamax, Actonel, and Boniva) and Denosumab (or Prolia) are examples of antiresorptive agents. Although it can occur spontaneously, ONJ more commonly occurs following surgical dental procedures like extracting a tooth or implant placement. Be sure to tell your dentist if you are taking antiresorptive agents so they can take that into account when developing your treatment plan.

A healthy, pain-free mouth can lead to a better state of mind!

Eating concerns: what to eat if you have….

Depending on the type of orthodontic treatment, your braces may have brackets, bands, and wires. In this case, it is important to avoid eating hard or sticky food. This includes things like nuts, popcorn, hard candy or gum, which could break or displace parts of your orthodontics and potentially delay your treatment. Enjoying pasta, soft veggies, fruits, and dairy products are good choices. Having good oral hygiene is key in making sure tooth decay do not form around the braces. This means making sure the teeth and braces are thoroughly cleaned of food debris so that plaque does not accumulate. Allowing plaque to build-up can cause white spots on the surfaces of the teeth. You can ask your dentist for tips on how to maintain good oral hygiene.

If you have clear trays or aligners that are removable, you should always remove your trays before eating or drinking any liquid other than water. Regardless of whether food is hard or soft, removing your tray before eating helps to ensure effectiveness of your treatment.

If you wear dentures, adjusting to what and how you eat can be a major challenge. When you first get dentures, your mouth and tissue need time to adjust to chewing and biting. Starting with soft foods like soups, smoothies, and applesauce for your first few meals can help make the transition more comfortable. Be mindful of hot dishes and drinks as it can sometimes be difficult to gauge the temperature of your food. After a couple of days, you can move onto more solid foods as your mouth begins to adjust to the dentures. Take care to avoid hard or sticky food and tough meats which could break or damage your dentures. Denture-friendly foods include slow-cooked or ground meats, cooked fish, ripe fruits, and cooked vegetables. A good tip is that if you can cut the food with a fork, chances are the food will not damage your dentures.

Dry mouth or xerostomia can make it difficult to talk, chew, and swallow food. Symptoms of dry mouth may include increased thirst, sore mouth and tongue, difficulty swallowing and talking, and changes in taste. [14] If you are experiencing a dry mouth, it is important to talk to your oral health care provider (as well as primary care provider) to better understand the potential causes and management. Regardless of the cause, you have lots of options for making it easier to eat. First, ensure that you drink plenty of fluids and sip cold water between meals. Chew your food well if you’re having trouble swallowing and only take small bites. Combining solid foods with liquid foods such as yogurt, gravy, sauces, or milk can also help. You want to avoid foods that are acidic, hot, or spicy as these may irritate your mouth further. Good oral care also plays a key role in alleviating dry mouth and preventing tooth decay, which is a common oral complication of dry mouth.

Oral Health Tips

Here are some actions you can take to support good oral health: [15]

- Drink fluoridated water and brush with fluoride toothpaste.

- Practice good oral hygiene. Brush teeth thoroughly twice a day and floss daily between the teeth to remove dental plaque.

- Visit your dentist at least once a year (the average person should go twice a year), even if you have no natural teeth or have dentures.

- Do not use any tobacco products. If you smoke, seek resources to help you quit.

- Limit alcoholic drinks. Some alcoholic beverages can be very acidic, resulting in erosion of tooth enamel, and those with a high alcohol content can lead to dry mouth. Also be mindful of drink mixers, many of which are high in sugar and can increase the risk of tooth decay.

- If you have diabetes , work to support control of the disease. This will decrease the risk for other complications, including gum disease. Treating gum disease may help lower your blood sugar level.

- If your medication causes dry mouth, discuss other medication options with your doctor that may not cause this condition. If dry mouth cannot be avoided, drink plenty of water, chew sugarless gum, and avoid tobacco products and alcohol. Your oral health care provider may be able to recommend over-the-counter or prescription medications to improve your dry mouth as well.

- See your doctor or a dentist if you experience sudden changes in taste and smell.

- When acting as a caregiver, help those who are not able to brush and floss their teeth independently.

- Chew sugar-free xylitol gum between meals and/or when you are unable to brush after a meal.

Bottom Line – There Is No Health Without Oral Health

As growing research and studies reveal the link between oral health and overall health, it becomes more evident that taking care of your teeth isn’t just about having a nice smile and pleasant breath. Studies show that poor oral health is linked to heart disease, diabetes, pregnancy complications, and more, while positive oral health can enhance both mental and overall health. Good oral hygiene and regular visits to the dentist, combined with a healthy lifestyle and avoiding risks like excess sugar and smoking, help to keep your smile and body healthy.

- Oral Cavity (mouth) starts at the lips and ends at the throat including the lips, inside the cheeks and lips, the tongue, gums, under the tongue, and roof of the mouth.

- Enamel is the hard calcified tissue covering the surface of the tooth.

- Gingiva (gums) is the soft tissue covering the necks of the teeth and the jaw bones.

- Periodontium is a group of specialized tissues that surround and support the teeth, including the gingiva and bone.

- Periodontal disease (gum disease) includes gingivitis and periodontitis. Gingivitis is the mildest form, in which the gums become red, swollen, and bleed easily. Gingivitis is reversible with professional treatment and good at-home oral care. If untreated, gingivitis can advance to periodontitis where chronic inflammation causes the tissues and bone that support the teeth to be damaged. Overtime, teeth can become loose and may fall out or need to be removed. [16]

- Check out the Harvard School of Dental Medicine for more information and resources for oral health

- Peres MA, Macpherson LM, Weyant RJ, Daly B, Venturelli R, Mathur MR, Listl S, Celeste RK, Guarnizo-Herreño CC, Kearns C, Benzian H. Oral diseases: a global public health challenge. The Lancet . 2019 Jul 20;394(10194):249-60.

- American Dental Association. n.d. Nutrition: What you eat affects your teeth . Mouth Healthy.

- Kohn WG, Maas WR, Malvitz DM, Presson SM, Shaddix KK. Recommendations for using fluoride to prevent and control dental caries in the United States. (2001).

- Chi DL, Scott JM. Added sugar and dental caries in children: a scientific update and future steps. Dental Clinics . 2019 Jan 1;63(1):17-33.

- Ehizele AO, Ojehanon PI, Akhionbare O. Nutrition and oral health. Benin Journal of Postgraduate Medicine. 2009;11(1).

- Suvan JE, Finer N, D’Aiuto F. Periodontal complications with obesity. Periodontology 2000 . 2018 Oct;78(1):98-128.

- Nazir MA. Prevalence of periodontal disease, its association with systemic diseases and prevention. International journal of health sciences . 2017 Apr;11(2):72.

- Lockhart PB, Brennan MT, Thornhill M, Michalowicz BS, Noll J, Bahrani-Mougeot FK, Sasser HC. Poor oral hygiene as a risk factor for infective endocarditis–related bacteremia. The Journal of the American Dental Association . 2009 Oct 1;140(10):1238-44.

- Borrell LN, Papapanou PN. Analytical epidemiology of periodontitis. Journal of clinical periodontology . 2005 Oct;32:132-58.

- Lockhart PB, Bolger AF, Papapanou PN, Osinbowale O, Trevisan M, Levison ME, Taubert KA, Newburger JW, Gornik HL, Gewitz MH, Wilson WR. Periodontal disease and atherosclerotic vascular disease: does the evidence support an independent association? A scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation . 2012 May 22;125(20):2520-44.

- American Dental Association. (n.d.). Pregnant? 9 Questions You May Have About Your Dental Health

- Reners M, Brecx M. Stress and periodontal disease. International journal of dental hygiene . 2007 Nov;5(4):199-204.

- American Dental Association. (n.d.). Osteoporosis and Oral Health .

- Cancer Treatment Centers of America. (n.d.). Dry mouth .

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2021. Oral Health Tips .

- The American Academy of Periodontology. (n.d.). Gum Disease Information .

Last reviewed December 2022

Terms of Use

The contents of this website are for educational purposes and are not intended to offer personal medical advice. You should seek the advice of your physician or other qualified health provider with any questions you may have regarding a medical condition. Never disregard professional medical advice or delay in seeking it because of something you have read on this website. The Nutrition Source does not recommend or endorse any products.

- Research article

- Open access

- Published: 14 July 2020

Incorporating oral health care education in undergraduate nursing curricula - a systematic review

- Vandana Bhagat ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-0158-1471 1 ,

- Ha Hoang ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-5116-9947 2 ,

- Leonard A. Crocombe ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-3916-0058 3 &

- Lynette R. Goldberg ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-8217-317X 4

BMC Nursing volume 19 , Article number: 66 ( 2020 ) Cite this article

9114 Accesses

27 Citations

1 Altmetric

Metrics details

The recognised relationship between oral health and general health, the rapidly increasing older population worldwide, and changes in the type of oral health care older people require have raised concerns for policymakers and health professionals. Nurses play a leading role in holistic and interprofessional care that supports health and ageing. It is essential to understand their preparation for providing oral health care.

Objective: To synthesise the evidence on nursing students’ attitudes towards, and knowledge of, oral healthcare, with a view to determining whether oral health education should be incorporated in nursing education.

Data sources : Three electronic databases - PubMed, Scopus, and CINAHL.

Study eligibility criteria, participants and interventions: Original studies addressing the research objective, written in English, published between 2008 and 2019, including students and educators in undergraduate nursing programs as participants, and conducted in Organisation of Economic Co-operation and Development countries.

Study appraisal and synthesis methods: Data extracted from identified studies were thematically analysed, and quality assessment was done using the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool.

From a pool of 567 articles, 11 met the eligibility criteria. Findings documented five important themes: 1.) nursing students’ limited oral health knowledge; 2.) their varying attitudes towards providing oral health care; 3.) the need for further oral health education in nursing curricula; 4.) available learning resources to promote oral health; and 5.) the value of an interprofessional education approach to promote oral health care in nursing programs.

Limitations: The identified studies recruited small samples, used self-report questionnaires and were conducted primarily in the United States.

Conclusions

The adoption of an interprofessional education approach with a focus on providing effective oral health care, particularly for older people, needs to be integrated into regular nursing education, and practice. This may increase the interest and skills of nursing students in providing oral health care. However, more rigorous studies are required to confirm this. Nursing graduates skilled in providing oral health care and interprofessional practice have the potential to improve the oral and general health of older people.

Peer Review reports

Introduction

Oral health is measured by the absence of orofacial pain, oral infection, periodontal (gum) diseases, tooth decay, tooth loss, and other orofacial diseases and disorders that can affect a person’s overall physical and mental health, and social well-being [ 1 , 2 , 3 ]. This is a particular concern for older people [ 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 ]. The world’s population is ageing rapidly [ 4 ]. Living longer brings challenges when meeting the complex healthcare needs of many older people and ensuring their quality of life. Currently, there is a profound disparity in the oral health of the older population, even in high-income countries [ 5 ].

Worldwide, the oral health of older people, defined as those over 65 years of age, is poor with a high prevalence of dental caries, periodontal diseases, dry mouth problems, and incremental tooth loss [ 5 , 6 ]. Oral health problems often lead to malnutrition, and difficulty with speech and swallowing [ 7 ]. There is increasing evidence of the association of periodontal problems with systemic conditions including type II diabetes, osteoporosis, cardiovascular problems such as myocardial infarction, stroke, coronary heart disease, and aspiration pneumonia that may lead to unplanned hospitalisations [ 8 , 9 , 10 ]. Poor oral health impacts morbidity, mortality, and recovery time after treatment [ 11 , 12 ]. Pain and suffering resulting from oral health problems may influence older people’s mood and behaviour, particularly if they have difficulty in communicating their discomfort [ 13 ]. Poor dental appearance and bad breath can lower self-esteem and exacerbate social isolation [ 14 ]. Thus, oral health problems can have profound physical, psychological, social, and economic consequences.

Most oral health problems experienced by older people are preventable or treatable [ 15 ]. However, they remain underdiagnosed and untreated due to the lack of effective, efficient, and equitable distribution of oral health services [ 15 ]. Reasons for the inadequate delivery of oral health services to older people include limited resources, poor understanding of oral care among nursing staff, lack of interprofessional collaboration, and inadequate policy protocols [ 16 , 17 ]. The lack of time, competing priorities, a high workload, and staffing issues are also significant barriers for providing oral care to older people [ 18 ].

The provision of quality and timely oral health care services to the rapidly increasing older population has become a large challenge for policymakers and health professionals [ 9 , 19 , 20 ]. Many changes have occurred in the oral health care needs of the older population in the twenty-first century due to the preservation of natural teeth, and the placement of complex prostheses such as crowns, bridges, overdentures, and implants. These changes highlight the need for staff trained in providing oral health care to older people [ 21 , 22 ]. With increasing age and ill-health, many people need assistance with their oral and general health care [ 23 , 24 ]. This is particularly true for dependent older adults in residential care communities and hospitals. However, oral health care is a low priority for non-dental health professionals [ 6 , 25 , 26 , 27 ].

Interprofessional education and collaborative practice have been recognised as a valuable approach to alleviate the global health workforce crisis and prepare a health workforce that will better respond to local health needs and ensure safe, holistic practice [ 28 ]. The World Dental Federation (FDI) also supports the need for interprofessional education and collaborative practice to improve access to oral health services [ 29 ]. Involving nurses, primary health care workers, and other allied health professionals in oral health care, will increase the national capacity to reach vulnerable and underserved population groups, including older people [ 6 ]. Nurses account for a large proportion of the health care workforce and are often present at the point of care or supervising direct caregivers [ 30 , 31 ]. Therefore, oral health care education and training are essential for graduating nurses to improve the oral and systemic health of older people [ 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 ]. Such education and practice provided with an interprofessional approach enables nursing students to contribute, learn and work effectively with other professionals involved in oral health [ 29 ].

Nurses provide care to older people in various settings such as hospitals, residential aged care, rehabilitation units, as well as in the community. Community nurses can educate and empower older people to take an active role in their oral care to prevent oral problems [ 37 ]. Nurses working in residential communities can take a leadership role in ensuring oral health care is integrated into routine nursing care [ 38 ]. Nurses can screen each resident’s oral health upon admission, assess the need for an examination by a dental professional, and prepare and monitor an oral health care plan [ 25 , 39 , 40 ]. Registered nurses can train and supervise personal care assistants in providing support to residents to maintain oral hygiene, monitor adequate nutrition, and identify signs of oral diseases [ 33 ]. Similarly, in hospitals, nurses can promote oral health, screen for any suspicious oral pathology, and make appropriate referrals [ 41 ]. Given interprofessional support, nurses can improve and maintain the oral health of older people when immediate access to an oral health therapist is not available [ 23 ].

To synthesise the evidence on nursing students’ attitudes towards, and knowledge of, oral health care, with a view to determining whether oral health education should be incorporated in nursing education. To our best knowledge, no previous study has summarised the literature on this topic.

Research questions

What do nursing students understand about oral health care?

What are the attitudes of nursing students towards providing oral health care?

Is there evidence of oral health education and training in nursing curricula?

A systematic review was performed following Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [ 42 ].

Eligibility criteria

Original studies addressing the research questions, written in English, published between 2008 and 2019, including students and educators in undergraduate nursing programs as participants, and conducted in Organisation of Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries. The review excluded studies involving students from certificate nursing courses, graduate nursing programs, and midwives. Studies reported in conference proceedings, short communications, thesis, or book chapters were also excluded.

Information sources and search

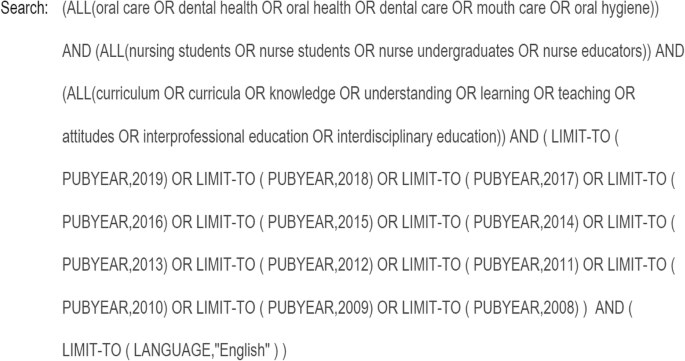

Three electronic databases were searched: PubMed, Scopus, and CINAHL. Boolean operators with the following keywords and strategy were used: (oral care OR dental health OR oral health OR dental care OR mouth care OR oral hygiene) AND (nursing students OR nurse students OR nurse undergraduates OR nurse educators) AND (curriculum OR curricula OR knowledge OR understanding OR learning OR teaching OR attitudes OR interprofessional education OR interdisciplinary education). A detailed example of the search strategy used for Scopus is outlined (Fig. 1 ). This search strategy was adapted for each of the databases.

Full electronic search strategy

Study selection

All original studies, including quantitative, qualitative, and mixed-method studies, were selected if they met the eligibility criteria. After an initial search and removing duplicates from the search list, titles and abstracts were independently screened by two authors (VB, HH) and the full texts of identified papers were then sought. Studies not fitting the eligibility criteria were excluded before the full text was reviewed. In cases of disagreement, two additional authors (LC, LG) were consulted to resolve any conflicts. Disagreements were resolved with consensus by referring back to the protocol. Research data were synthesised systematically, and the quality of the included studies was then evaluated.

Data extraction

The data collection form was developed by two authors (VB, HH) referring to previous systematic reviews in the related field; data extraction was then performed independently by VB. The accuracy of the extracted data was verified by the second author (HH). Information collected from the identified articles for this systematic review included: country and setting, details of participants, objectives of the study, research design, description of the main findings related to the three research questions, and the reported limitations of each study (Table 1 ).

Data synthesis

Extracted data were analysed thematically to produce a narrative description of the findings. While thematic synthesis is commonly used for qualitative research outcomes, it can be used for quantitative research outcomes when there is heterogeneity in measurements. Therefore, the process of thematic synthesis was chosen to narrate the findings of this review [ 53 ]. The thematic analysis was conducted according to Braun and Clarke’s guidelines: familiarisation with the data, coding, developing potential themes, reviewing themes, defining themes and reporting data relating to research questions [ 54 ]. The coding process involved segmenting data into similar groups and identifying the relationship between codes. After finishing the coding process, codes were grouped into descriptive themes that captured similarities in the data across identified studies. Finally, selected themes were reviewed, and synthesised data were finalised in relation to the research questions.

A meta-analyses of the identified studies was not possible because of the small number of studies, participants, and heterogeneity.

Quality assessment

The quality assessment of the identified studies was done by two authors (VB, HH) using the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) [ 55 ]. All studies were screened regarding the clarity of their research questions, and whether collected data addressed the research questions. Studies that passed the screening were then appraised using methodological quality assessment questions relative to the study design. Studies that met all assessment criteria scored 1; studies that met fewer criteria scored less than 1.

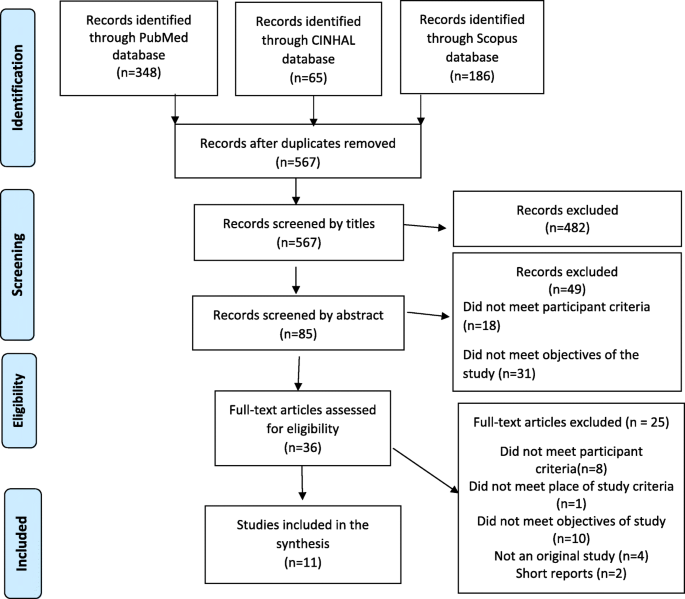

From a pool of 567 articles, 11 met the eligibility criteria (Fig. 2 ). A large number of articles were excluded based on the wording of their titles (482), 49 were excluded from reading the abstract, and a further 25 were excluded after reading the full text. Finally, 11 studies were included in this paper. Of the 11 studies, six were conducted in the United States, two in Australia, and one each in Japan, Turkey, and Canada. Studies evaluating nursing students’ oral health knowledge and attitudes of oral health care used cross-sectional survey design; intervention studies assessing the impact of the inclusion of oral health components in nursing curricula used quasi-experimental pre-post survey design, post-survey design, retrospective pre-post survey design, and cross-sectional qualitative design. The study evaluating oral health care resources for older people used a mixed-method design.

PRISMA flowchart detailing search results and the selection of studies

The main findings of the 11 identified studies were 1.) nursing students’ limited oral health knowledge; 2.) their varying attitudes towards providing oral health care; 3.) the need for further oral health education in nursing curricula; 4.) available learning resources to promote oral health; and 5.) the value of an interprofessional education (IPE) approach to promote oral health care in nursing programs. The results of the quality assessment of the identified papers are shown in Tables 2 , 3 , 4 and 5 .

Synthesis of results: five identified themes

Limited knowledge of oral health care among nursing students.

Only three studies [ 31 , 43 , 45 ] assessed the oral health knowledge of nursing students. Using convenience samples ranging from 30 to163 students, each study used different questionnaires. Data were collected from students belonging to a single university or at different campuses of the same university. Studies conducted in the US and Japan showed students had limited oral health care knowledge and inadequate understanding of the crucial elements of an oral health assessment and promotion of effective oral health practices [ 43 , 45 ]. Only 25% of all participants in the US-based study by Clemmens et al. [ 43 ] were able to recognise the critical components of oral health assessment, despite a majority of students thinking they understood these components. In Japan, Haresaku et al. [ 45 ] found that only half of the nursing students knew that oral health diseases could have an impact on systemic health. An earlier study by Pai et al. [ 31 ] in Australia showed nursing students understood issues related to periodontal diseases; however, the majority of participants were not confident about their understanding and recommended including more detailed oral health content in their nursing curriculum.

Varying attitudes of nursing students towards oral health care

Three studies conducted in the US [ 43 ], Japan [ 45 ], and Turkey [ 44 ] evaluated the attitudes of nursing students towards providing oral health care. Clemmens et al. [ 43 ] found that nursing students felt oral health care to be an essential component for effective nursing practice. A different trend was observed in nursing students from Turkey and Japan. Nursing students from Turkey often avoided going to a dentist until they developed a painful oral condition [ 44 ]. In Japan, the attitudes of nursing students toward oral health appeared negative, with 39.2% of students stating that they were not interested in learning about oral health and practice [ 45 ].

Need for further oral health care education for nursing students

Seven of the 11 studies provided suggestions for including an oral health component in nursing curricula. Six of the seven studies [ 46 , 47 , 48 , 50 , 51 , 52 ] focussed on an interprofessional oral health education model. The remaining study [ 49 ] provided information about resources for older people’s oral health care for nursing curricula.

Available learning resources for nursing students to promote oral health

Lewis et al. [ 49 ] evaluated the relevance of “Building Better Oral Health Communities” (BBOHC) resources for students undertaking a Bachelor of Nursing, Diploma of Nursing, or Certificate III in Aged Care. The BBOHC resources were developed as a part of the Australian government-funded project for aged care workforce training in older people’s oral health care [ 13 ]. The BBOHC consists of five modules: 1) better oral health care, 2) dementia and oral care, 3) understanding the mouth, 4) care for natural teeth, and 5) care for dentures. Participating students were highly satisfied with the content of this resource [ 49 ]. Student learning outcomes showed consistently positive attitudes and substantial enhancements in oral health care knowledge and skills. Educators found the BBOHC content highly relevant in reinforcing a comprehensive approach to older people’s oral health care, which included learning about the consequences of poor health, dry mouth problems, oral health assessment, oral health planning, and timely referral. Educators also found the resources useful in building students’ skills in daily oral hygiene practice by increasing awareness about oral hygiene products, tooth brushing techniques, denture cleaning, and techniques to manage care resistive behaviours [ 49 ].

Value of an Interprofessional education model

An interprofessional education (IPE) model in which nursing students work with, learn from, and contribute to the oral-systemic knowledge of dental and other allied health students has been found effective in improving understanding of nursing students towards their role in oral health care [ 46 , 47 , 48 , 50 , 51 , 52 ]. All the studies focussing on IPE were conducted in the US except the study by Grant et al. [ 46 ], which was conducted in Canada.

As a result of their IPE experiences in lectures and simulation exercises, nursing students showed significant improvement in oral health behaviour, knowledge, and attitudes regarding the importance of oral health care [ 47 , 52 ]. Interprofessional education and practice experiences also increased nursing students’ confidence in conducting oral examinations and providing counselling [ 50 ]. IPE provided the platform for students to explore oral-systemic disease connections in a supportive team culture [ 46 , 48 , 51 ]. IPE helped nursing students to learn oral risk assessments, identify common oral pathologies, engage in oral hygiene activities, use fluoride varnish and work with students from other professions to promote oral health [ 47 ]. IPE clinical experiences focussing on oral-systemic health were valuable in enhancing shared professional skills with hands-on care, facilitating effective communication, and working as a team to develop an integrated plan of care to ensure holistic care [ 50 , 51 ]. Nursing students’ experiences in interprofessional clinical practice were instrumental in understanding how underserved and rural communities could benefit from accessing multiple providers at one place on the same day [ 50 ].

Summary of evidence

This review of 11 identified studies documented limited oral health knowledge and varying attitudes (both favourable and unfavourable) of nursing students towards oral health care. The review identified available learning resources and highlighted the importance of an interprofessional education and practice approach in improving oral health knowledge and attitudes among nursing students.

Growing evidence of the relationship between poor oral health and general systemic health requires urgent attention. The inclusion of oral health care education in nursing curricula, integrated with an interprofessional approach, will strengthen the capability and interest of future nurse practitioners to include evidence-based effective oral health care in routine nursing care. It is important to understand that “oral health care” can be interpreted differently by different health professionals [ 56 ]. For nursing practice, oral health care includes collaboration with dental, medical, and allied health professionals. For nursing students, this entails understanding the factors affecting people’s oral health and oral health-related quality of life, ensuring daily oral care practice, and being able to complete an oral health screening. Such screening includes checking the status and function of oral structures and dentures, swallowing ability, nutritional status, asking each person’s perspective about their oral and general health and whether they have any concerns, and making appropriate referrals. Daily oral care for older people in residential care includes assisting with evidence-based oral hygiene, use of saliva substitutes when appropriate, water hydration, desensitising agents, lip balms, denture cleaning tablets, pastes and adhesive pastes, and fluoride varnishes.

Older people are at particular risk for poor oral health. This review showed a significant gap in the current literature on nursing students’ knowledge of oral health care for older people and how this gap is best addressed through interprofessional education and practice. Interprofessional education and practice is one of the best ways to improve both nursing students’ awareness of the importance of oral health and their role in improving access to and providing oral health services [ 48 , 57 ]. IPE facilitates collaborative work in varying health care settings including educational institutes [ 52 ], dental health clinics [ 47 ], mobile clinics in underserved areas [ 48 ] and hospitals [ 51 ]. While challenges remain in coordinating curricula across disciplines to facilitate students’ involvement in IPE initiatives, providing nursing students with opportunities to include oral health assessments in their assessment of overall body function would significantly improve the health outcomes of older people [ 32 , 58 ]. IPE models have been implemented successfully in many graduate nursing programs in addition to undergraduate nursing programs [ 46 , 59 , 60 , 61 , 62 , 63 ]. The “Smile for Life-National Oral Health Curriculum” has been popular with graduate nursing students [ 17 , 59 , 62 , 63 , 64 ]. This comprehensive oral health curriculum was initially developed in 2005 for primary health workers. It is freely available online and could be readily integrated into IPE activities in nursing curricula ( www.smilesforlifeoralhealth.com ) [ 65 ].

Implementing IPE into nursing curricula requires thought, time, and careful planning to ensure that students from other health-related programs can participate [ 46 , 63 , 66 ]. Organising IPE with students and faculty from different health programs with different health knowledge makes IPE challenging [ 48 ]. Flexibility, willingness, and cooperation among all professionals are needed for effective collaborative and interprofessional learning [ 46 ]. Establishing academic credit for students participating in IPE is an effective way to involve and encourage students in collaborative learning about oral health [ 46 , 66 ].

Effective oral health education must include clinical practice and ideally interprofessional clinical practice. The best way to translate oral health learning to practice is to shift from the traditional physical assessment approach that is Head, Eyes, Ears, Nose, Throat (HEENT) to the Head, Eyes, Ears, Nose, Oral cavity, and Throat (HEENOT) approach for the assessment, diagnosis, and treatment of oral-systemic health [ 17 ]. The HEENOT approach ensures that one does “NOT” leave oral health assessment out of any medical history and physical examination. The success of the HEENOT approach was evidenced by more than 1000 referrals to the Nursing Faculty Practice (NFP) from New York University (NYU) dental clinics between 2008 and 2014. The HEENOT approach resulted in increased care appointments and more than 500 referrals to NYU dental clinics from the NFP [ 17 ]. Another collaborative model provided students in nursing, dental hygiene, and health services management with community-based experience providing affordable oral health services and oral health education [ 67 ]. Nursing students’ involvement in early detection of oral health issues and appropriate, timely referral to a dentist can ensure minimal cost treatment and improve patient-centred care [ 31 ].

This systematic review is a valuable initial step in identifying the current knowledge and attitudes of nursing students towards providing oral health care and recognising factors to reinforce their interest in oral health care, particularly for older people [ 45 ]. Results have several implications for nursing students, nursing educators, nursing education accreditation authorities, and researchers. Nursing students need to understand the importance of oral health, the relationship of poor oral health to systemic disease, the importance of their competency in oral health practices, and their important role in maintaining the health of older people. Oral health education and practical experience occur best in an interprofessional situation to build confidence, motivation, knowledge, and skills. Nursing educators need to understand and implement an interprofessional approach to oral health education and practice in nursing curricula. Nursing education accreditation authorities need to pay attention to develop guidelines to promote oral health care learning and practice among nursing students who are future health professionals. IPE improves workplace practices and productivity, patient health outcomes, staff morale, patient safety, and enables better access to health care [ 28 ]. Ongoing rigorous research is required to understand the extent to which oral health is addressed in nursing curricula in Australia and to evaluate the inclusion and impact of oral health content, delivered through interprofessional education and clinical practice, in undergraduate nursing curricula.

Limitations

Most of the reviewed studies were conducted in the United States and had small sample sizes belonging to a single location; therefore, the results cannot be generalised. Some intervention studies had quasi-experimental designs, and there was a lack of blinding of the intervention leading to questions on the trustworthiness of the study results. Self-report questionnaires were used in the identified studies which may be biased by respondent beliefs. The long-term evaluation results of an integrated oral health learning model are still not available to check the effectiveness of IPE in building nursing students’ capacity in oral healthcare delivery.

This review supports the need to integrate oral health education into nursing curricula, ideally through an IPE approach, to increase nursing students’ knowledge and ability to provide oral care, particularly to maintain the health of older people, and to interest students in providing effective oral care. There is a need to conduct rigorous well-designed studies about how best to achieve this and measure its success. A future nursing workforce with competence in oral health care will help to improve the oral health and quality of life of all people, especially those who are older and dependent on others for care.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed during this study is included in this article.

Abbreviations

Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature

Organisation of Economic Co-operation and Development

Interprofessional education

Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool

Building Better Oral Health Communities

Head, Eyes, Ears, Nose, Oral cavity, and Throat

New York University

Glick M, Williams DM, Kleinman DV, Vujicic M, Watt RG, Weyant RJ. A new definition for oral health developed by the FDI World Dental Federation opens the door to a universal definition of oral health. Br Dent J. 2016;221(12):792–3.

CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Petersen PE. The World Oral Health report 2003: continuous improvement of oral health in the 21st century - the approach of the WHO global Oral Health Programme. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2003;31(SUPPL. 1):3–24.

PubMed Google Scholar

World Health Organisation. Oral Health. 2020 [cited 17 June 2020]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/oral-health . Accessed 17 June 2020.

World Health Organisation. Ageing and Health. 2018 [cited 17 June 2020]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/ageing-and-health . Accessed 17 June 2020.

Gil-Montoya JA, Ferreira de Mello AL, Barrios R, Gonzalez-Moles MA, Bravo M. Oral health in the elderly patient and its impact on general well-being: a nonsystematic review. Clin Interventions in Aging. 2015;ume 10:461–7.

Petersen PE, Kandelman D, Arpin S, Ogawa H. Global oral health of older people--call for public health action. Community Dent Health. 2010;27(4 Suppl 2):257–67.

Hopcraft MS. Dental demographics and metrics of oral diseases in the ageing Australian population. Aust Dent J. 2015;60(Suppl 1):2–13.

Gutkowski S. The biggest wound: oral health in long-term care residents. Annals of Long Term Care: Clinical Care and Ageing. 2011;19(7):23–5.

Kandelman D, Petersen PE, Ueda H. Oral health, general health, and quality of life in older people. Special Care Dentistry. 2008;28(6):224–36.

Google Scholar

Seymour GJ, Ford PJ, Cullinan MP, Leishman S, Yamazaki K. Relationship between periodontal infections and systemic disease. Clin Microbiol Infection. 2007;13(S4):3–10.

CAS Google Scholar

Awano S, Ansai T, Soh I, Hamasaki T, Yoshida A, Takehara T, et al. Oral health and mortality risk from pneumonia in the elderly. J Dent Res. 2008;87(4):334–9.

El-Solh AA. Association between pneumonia and Oral Care in Nursing Home Residents. Lung. 2011;189(3):173.

SA Health. Why oral health care is important for older people. 2020 [cited 17 June 2020] Available from: https://www.sahealth.sa.gov.au/wps/wcm/connect/public+content/sa+health+internet/clinical+resources/clinical+programs+and+practice+guidelines/oral+health/oral+health+care+for+older+people/why+oral+health+care+is+important+for+older+people .

Kisely S. No mental Health without Oral Health. Can J Psychiatry. 2016;61(5):277–82.

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Kossioni AE, Hajto-Bryk J, Maggi S, McKenna G, Petrovic M, Roller-Wirnsberger RE, et al. An Expert Opinion from the European College of Gerodontology and the European Geriatric Medicine Society: European Policy Recommendations on Oral Health in Older Adults 2018:609.

Hearn L, Slack-Smith L. Engaging dental professionals in residential aged-care facilities: staff perspectives regarding access to oral care. Australian J Primary Health. 2016;22(5):445–51.

Haber J, Hartnett E, Allen K, Hallas D, Dorsen C, Lange-Kessler J, et al. Putting the mouth back in the head: HEENT to HEENOT. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(3):437–41.

Hoang H, Barnett T, Maine G, Crocombe L. Aged care staff’s experiences of ‘better Oral Health in residential care training’: a qualitative study. Contemp Nurse. 2018;54(3):268–83.

Petersen PE, Yamamoto T. Improving the oral health of older people: the approach of the WHO global Oral Health Programme. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2005;33(2):81–92.

Thomson W, Ma S. An ageing population poses dental challenges. Singap Dent J. 2014;35C:3–8.

Bailey R, Gueldner S, Ledikwe J, Smiciklas-Wright H. The oral health of older adults: an interdisciplinary mandate. J Gerontol Nurs. 2005;31(7):11–7.

Forsell M, Sjögren P, Kullberg E, Johansson O, Wedel P, Herbst B, et al. Attitudes and perceptions towards oral hygiene tasks among geriatric nursing home staff. Int J Dent Hyg. 2011;9(3):199–203.

Gibney JM, Wright FA, D'Souza M, Naganathan V. Improving the oral health of older people in hospital. Australasian J Ageing. 2019;38(1):33–8.

Jablonski RA, Kolanowski A, Therrien B, Mahoney EK, Kassab C, Leslie DL. Reducing care-resistant behaviors during oral hygiene in persons with dementia. BMC Oral Health. 2011;11:30.

Malkin B. The importance of patients’ oral health and nurses’role in assessing and maintaining it. Nurs Times. 2008;105:19–23.

Albrecht M. Oral health educational interventions for nursing home staff and residents. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. (9).

Wårdh I, Hallberg LR, Berggren U, Andersson L, Sörensen S. Oral health care--a low priority in nursing. In-depth interviews with nursing staff. Scand J Caring Sci. 2000;14(2):137–42.

World Health Organisation. Framework for action on interprofessional education and collaborative practice 2010 [cited 17 June 2020]. Available from: https://www.who.int/hrh/resources/framework_action/en/ . Accessed 17 June 2020.

FDI World Dental Federation. Optimal Oral Health through inter-professional education and collaborative practice. 2015 [Available from: https://www.fdiworlddental.org/sites/default/files/media/news/collaborative-practice_digital.pdf ]. Accessed 17 June 2020.

Dolce MC. Integrating oral health into professional nursing practice: an interprofessional faculty tool kit. J Professional Nurs. 2014;30(1):63–71.

Pai M, Ribot B, Tane H, Murray J. A study of periodontal disease awareness amongst third-year nursing students. Contemporary Nurse. 2016;52(6):686–95.

Dolce MC, Haber J, Shelley D. Oral health nursing education and practice program. Nurs Res Pract. 2012;2012:149673.

Rohr. Assessment and care of the mouth: An essential nursing activity, especially for debilitated or dying inpatients. HNE handover for nurses and midwives. 2012;5(1):33–4.

Young LM, Machado CK, Clark SB. Repurposing with purpose: creating a collaborative learning space to support institutional Interprofessional initiatives. Med Reference Services Quarterly. 2015;34(4):441–50.

Hoyles A, Pollard C, Lees S, Glossop D. Nursing students' early exposure to clinical practice: An innovation in curriculum development. Nurse education today. 2000;20:490–8.

Grønkjær LL, Nielsen N, Nielsen M, Smedegaard C. Oral health behaviour, knowledge, and attitude among nursing students. J Nurs Educ Practice. 2017;7(8):1–6.

Daly B, Smith K. Promoting good dental health in older people: role of the community nurse. Brit J Community Nurs. 2015;20(9):431–6.

Hoben M, Kent A, Kobagi N, Huynh KT, Clarke A, Yoon MN. Effective strategies to motivate nursing home residents in oral care and to prevent or reduce responsive behaviors to oral care: a systematic review. PLoS One. 2017;12(6):e0178913.

Tetuan T. The role of the nurse in oral health. Kansas Nurse. 2004;79(10):1–2.

Moore K. Oral health progress in Kansas. Kansas Nurse. 2004;79(10):8–10.

Garry B, Boran S. Promotion of oral health by community nurses. Brit J Community Nurs. 2017;22(10):496–502.

Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gøtzsche PC, Ioannidis JPA, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ. 2009;339:b2700.

Clemmens D, Rodriguez K, Leef B. Knowledge, attitudes, and practices of baccalaureate nursing students regarding oral health assessment. J Nurs Educ. 2012;51(9):532–5.

Doğan B. Differences in oral health behavior and attitudes between dental and nursing students. J Marmara University Institute of Health Sciences. 2013;3(1):34–40.

Haresaku S, Monji M, Miyoshi M, Kubota K, Kuroki M, Aoki H, et al. Factors associated with a positive willingness to practise oral health care in the future amongst oral healthcare and nursing students. Eur J Dental Educ. 2018;22(3):e634–e43.

Grant L, McKay LK, Rogers LG, Wiesenthal S, Cherney SL, Betts LA. An interprofessional education initiative between students of Dental Hygiene and Bachelor of Science in Nursing. Can J Dent Hyg. 2011;45(1):36–44.

Czarnecki GA, Kloostra SJ, Boynton JR, Inglehart MR. Nursing and dental students' and pediatric dentistry residents' responses to experiences with interprofessional education. J Dent Educ. 2014;78(9):1301–12.

Farokhi MR, Muck A, Lozano-Pineda J, Boone SL, Worabo H. Using Interprofessional education to promote Oral Health literacy in a faculty-student collaborative practice. J Dent Educ. 2018;82(10):1091–7.

Lewis A, Edwards S, Whiting G, Donnelly F. Evaluating student learning outcomes in oral health knowledge and skills. J Clin Nurs. 2018;27(11–12):2438–49.

Nierenberg S, Hughes LP, Warunek M, Gambacorta JE, Dickerson SS, Campbell-Heider N. Nursing and Dental Students' reflections on Interprofessional practice after a service-learning experience in Appalachia. J Dent Educ. 2018;82(5):454–61.

Coan LL, Wijesuriya UA, Seibert SA. Collaboration of Dental hygiene and nursing students on hospital units: an Interprofessional education experience. J Dent Educ. 2019;83(6):654–62.

Dsouza R, Quinonez R, Hubbell S, Brame J. Promoting oral health in nursing education through interprofessional collaborative practice: a quasi-experimental survey study design. Nurse Educ Today. 2019;82:93–8.

Ryan C, Hesselgreaves H, Wu O, Paul J, Dixon-Hughes J, Moss JG. Protocol for a systematic review and thematic synthesis of patient experiences of central venous access devices in anti-cancer treatment. Syst Rev. 2018;7(1):61.

Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101.

Hong QN, Fàbregues S, Bartlett G, Boardman F, Cargo M, Dagenais P, et al. The Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) version 2018 for information professionals and researchers. Educ Inf. 2018;34:285-91.

Koichiro U. Preventing aspiration pneumonia by oral health care. Japan Med Assoc J. 2011;54:39–43.

Goldberg LR, Koontz JS, Rogers N, Brickell J. Considering accreditation in gerontology: the importance of interprofessional collaborative competencies to ensure quality health care for older adults. Gerontol Geriatrics Educ. 2012;33(1):95–110.

Hein C, Schönwetter DJ, Iacopino AM. Inclusion of oral-systemic health in predoctoral/undergraduate curricula of pharmacy, nursing, and medical schools around the world: a preliminary study. J Dent Educ. 2011;75(9):1187–99.

Dolce MC, Parker JL, Marshall C, Riedy CA, Simon LE, Barrow J, et al. Expanding collaborative boundaries in nursing education and practice: the nurse practitioner-dentist model for primary care. J Professional Nurs. 2017;33(6):405–9.

Estes KR, Callanan D, Rai N, Plunkett K, Brunson D, Tiwari T. Evaluation of an Interprofessional Oral Health assessment activity in advanced practice nursing education. J Dent Educ. 2018;82(10):1084–90.

Golinveaux J, Gerbert B, Cheng J, Duderstadt K, Alkon A, Mullen S, et al. Oral health education for pediatric nurse practitioner students. J Dent Educ. 2013;77(5):581–90.

Haber J, Hartnett E, Allen K, Crowe R, Adams J, Bella A, et al. The impact of Oral-systemic Health on advancing Interprofessional education outcomes. J Dent Educ. 2017;81(2):140–8.

Nash WA, Hall LA, Lee Ridner S, Hayden D, Mayfield T, Firriolo J, et al. Evaluation of an interprofessional education program for advanced practice nursing and dental students: the oral-systemic health connection. Nurse Educ Today. 2018;66:25–32.

Kent KA, Clark CA. Open wide and say A-ha: adding Oral Health content to the nurse practitioner curriculum. Nurs Educ Perspect. 2018;39(4):253–4.