Trail of Tears Research Paper Topics

This page presents a comprehensive guide to Trail of Tears research paper topics , tailored for students of history who seek to delve into this tragic chapter of American history. From an extensive list of topics to valuable tips on selecting and crafting research papers, this page aims to equip students with the necessary tools to navigate through the complexities of the Trail of Tears and to understand its significance in shaping the nation’s past and present. Additionally, we introduce iResearchNet’s writing services, a reliable partner in providing top-quality custom research papers that meet students’ academic requirements and elevate their understanding of this critical historical event.

100 Trail of Tears Research Paper Topics

The Trail of Tears remains a poignant and significant episode in American history, exemplifying the dark side of westward expansion and the profound impact it had on Native American communities. To aid students in their research endeavors, we present a comprehensive list of Trail of Tears research paper topics, divided into 10 categories, each offering valuable insights into different aspects of this tragic event.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% off with 24start discount code.

- The Indian Removal Act of 1830: Origins and implications

- The political climate and public opinion surrounding Native American removal

- Examination of treaties and agreements leading to forced removal

- Comparison of Native American removal policies with other historical instances

- The role of President Andrew Jackson in the Trail of Tears

- The impact of the Trail of Tears on U.S. government and policies toward Native Americans

- Native American resistance and activism during the removal

- The Trail of Tears as a turning point in Native American-U.S. government relations

- The Trail of Tears in the broader context of American expansionism

- The ethical and moral implications of the Trail of Tears

- Cherokee culture and society before the Trail of Tears

- Principal Chiefs and tribal leadership during the removal

- The impact of removal on Cherokee communities

- Cherokee cultural preservation and adaptation after the relocation

- The significance of Cherokee language and education during the Trail of Tears

- The role of Cherokee women during the removal process

- The representation of Cherokee people in contemporary literature and media

- The legacy of Cherokee removal in modern-day Cherokee Nation

- Cherokee-Native American relations after the Trail of Tears

- The portrayal of the Cherokee removal in oral histories and folktales

- The different routes taken by various tribes

- Conditions and challenges faced during the journey

- Accounts of individual experiences during the relocation

- The impact of geography and environment on the Trail of Tears

- The role of military escorts and their treatment of Native Americans

- The significance of rivers and waterways in the forced removal

- The role of missionaries and churches in aiding or opposing the removal

- The Trail of Tears as a transnational event affecting multiple Native American nations

- The use of primary sources, such as diaries and letters, to reconstruct the journey

- The archeological evidence and artifacts related to the Trail of Tears routes

- The experiences of Choctaw, Creek, Chickasaw, and Seminole tribes

- Comparisons between the different tribes’ experiences

- Resilience and adaptation of Native American communities after relocation

- The impact of the Trail of Tears on intertribal relations and alliances

- The legacy of the Trail of Tears in other Native American removals

- The influence of non-removal tribes in advocating for those affected by the Trail of Tears

- The role of Native American leaders and activists in response to removal policies

- The cultural exchange and conflicts between different Native American tribes during the relocation

- The representation of other Native American tribes in historical accounts of the Trail of Tears

- The historical memory and commemoration of the Trail of Tears among non-Cherokee tribes

- Attempts at legal challenges and resistance against removal

- Life in the Indian Territory and efforts at rebuilding communities

- Comparing pre- and post-removal living conditions and challenges

- The impact of forced assimilation policies on Native American communities

- Native American efforts at preserving cultural practices and traditions in the Indian Territory

- The role of trade and economic activities in the Indian Territory

- The role of education and mission schools in the Indian Territory

- The influence of European settlers and traders in the Indian Territory

- The significance of land ownership and distribution in the Indian Territory

- The consequences of disease and illness on Native American populations in the Indian Territory

- Effects on the economies of Native American tribes

- Influence on the Southern economy and agricultural labor

- Interactions and tensions between Native Americans and white settlers

- The impact of the Trail of Tears on the Southern labor force

- The role of African American slaves in the removal process and the Indian Territory

- The economic and social dynamics between Native American tribes and African American slaves in the Indian Territory

- The role of Native American labor and participation in the Southern economy after removal

- The role of missionaries and churches in aiding Native American economic development in the Indian Territory

- The impact of the Trail of Tears on Southern society and culture

- The representation of economic aspects of the Trail of Tears in historical documents and literature

- The psychological trauma experienced by Native American communities during the Trail of Tears

- The impact of forced assimilation and acculturation on Native American identity

- The preservation and revival of cultural practices and traditions after the removal

- The role of storytelling and oral traditions in passing down the memory of the Trail of Tears

- The representation of the Trail of Tears in Native American art and literature

- The intergenerational effects of the Trail of Tears on Native American communities

- The influence of the Trail of Tears on Native American religious beliefs and practices

- The relationship between Native American spirituality and land in the context of the removal

- The depiction of Native American cultures in the media and popular culture after the Trail of Tears

- The exploration of cultural resilience and adaptation in the face of adversity

- The response of U.S. government and political leaders to the Trail of Tears

- The justification and debate over Native American removal policies

- The impact of the Trail of Tears on the U.S. Supreme Court and legal interpretations of indigenous rights

- The influence of the Trail of Tears on subsequent federal Indian policies

- The role of advocacy groups and activists in challenging removal policies

- The legacy of the Trail of Tears in modern Native American rights movements

- The examination of treaties and agreements violated during the removal process

- The international response and criticism of the U.S. government’s removal policies

- The role of local and state governments in facilitating or opposing the removal

- The exploration of reparations and recognition efforts for the descendants of those affected by the Trail of Tears

- The involvement and experiences of African American slaves during the Trail of Tears

- The relationship between Native American slaveholders and their African American slaves

- The role of African American slaves in the Cherokee Nation and other tribes

- The challenges faced by African American communities after the removal

- The intersectionality of African American and Native American identities and experiences

- The impact of the Trail of Tears on African American migration and settlement patterns

- The legacy of the Trail of Tears in African American cultural memory and heritage

- The portrayal of African American perspectives on the removal in historical accounts

- The influence of the Trail of Tears on African American civil rights movements

- The examination of race relations and interactions between African Americans and Native Americans in the Indian Territory

- The ways in which the Trail of Tears is commemorated and memorialized today

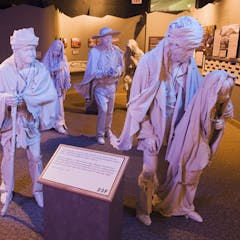

- The establishment and significance of Trail of Tears National Historic Trails and museums

- The representation of the Trail of Tears in public history and education

- The exploration of contested narratives and perspectives on the removal

- The role of historical preservation and archeology in understanding the Trail of Tears

- The significance of local and community efforts to remember the Trail of Tears

- The impact of cultural heritage and tourism on the memory of the Trail of Tears

- The comparison of American and indigenous perspectives on the Trail of Tears

- The role of storytelling and oral history in preserving the memory of the Trail of Tears

- The examination of ongoing efforts to reconcile and come to terms with the historical legacy of the Trail of Tears

This comprehensive list of Trail of Tears research paper topics provides students with a diverse array of avenues to explore the Trail of Tears, examining its historical context, cultural implications, and long-lasting effects on both Native American tribes and the nation as a whole. Each topic offers unique opportunities for critical analysis and contributes to a deeper understanding of this tragic and significant event in American history. Whether focusing on the experiences of specific tribes, the socio-economic impact, or the event’s portrayal in popular culture, students can uncover a wealth of insights and perspectives that shed light on the complex legacy of the Trail of Tears.

Trail of Tears: A Tragic Chapter in American History

The Trail of Tears stands as one of the most tragic and consequential events in American history, leaving an indelible mark on the nation’s conscience. This 1000-word article will delve into the historical context, causes, and profound consequences of the Trail of Tears, shedding light on the forced removal of Native American tribes from their ancestral lands and the devastating impact it had on their cultures and livelihoods. Moreover, this article will highlight the significance of researching the Trail of Tears and the relevance it holds in contemporary times, as its legacy continues to shape the course of Native American communities and the United States as a whole.

Historical Context and Causes

To comprehend the significance of the Trail of Tears, it is crucial to understand its historical context. In the early 19th century, the United States underwent rapid expansion, driven by a fervent desire for territorial acquisition and economic growth. This ambition came at the expense of the indigenous peoples who inhabited the fertile lands of the Southeastern United States. As white settlers sought more land for agriculture and settlement, the federal government pursued a policy of forced removal of Native American tribes, leading to the tragic events that would become known as the Trail of Tears.

The Forced Removal

The Trail of Tears refers to the forced relocation of several Native American tribes, including the Cherokee, Choctaw, Chickasaw, Creek, and Seminole, from their ancestral homelands to lands west of the Mississippi River. The removal process was marked by deception, coercion, and violence. The tribes were subjected to treaties that were often obtained through unfair negotiations and signed under duress. These treaties stripped them of their land rights and forced them to leave behind their homes, communities, and cultural heritage.

Impact on Cultures and Livelihoods

The consequences of the Trail of Tears were devastating for the Native American tribes. The forced migration resulted in the loss of countless lives due to exposure, disease, and hunger. Families were torn apart, and entire communities were uprooted from their traditional ways of life. The removal had a profound impact on the tribes’ cultures, as they struggled to maintain their customs, languages, and religious practices in their new, unfamiliar surroundings. The forced assimilation into white American society further eroded their cultural identity and threatened the survival of their distinct ways of life.

Significance of Researching the Trail of Tears

Researching the Trail of Tears is not merely an academic pursuit but a moral imperative. Understanding the historical injustice and the human toll of this dark chapter in American history is essential for acknowledging the wrongs committed against Native American communities. It provides an opportunity to confront the legacy of dispossession, discrimination, and marginalization that continues to affect these communities today. By exploring this historical event, researchers can gain insights into the complexity of Native American experiences and the resilience of their cultures in the face of immense challenges.

Relevance in Contemporary Times

The legacy of the Trail of Tears reverberates in contemporary American society. It serves as a stark reminder of the profound impact of colonization, racism, and forced assimilation on indigenous peoples. The struggle for land rights, self-determination, and recognition of cultural heritage remains ongoing for Native American communities. Researching the Trail of Tears allows for a deeper understanding of the historical and ongoing injustices faced by these communities and the urgent need for reconciliation and social justice.

The Trail of Tears represents a dark and tragic chapter in American history, marked by the forced removal of Native American tribes and the immense suffering they endured. This article has provided insights into the historical context, causes, and consequences of the Trail of Tears, shedding light on its devastating impact on Native American cultures and livelihoods. Moreover, it has emphasized the importance of researching this pivotal event and its relevance in contemporary times, calling for greater awareness and acknowledgment of the historical injustices committed against Native American communities. By studying the Trail of Tears, we can strive for a more inclusive and empathetic understanding of American history, fostering a commitment to justice, reconciliation, and respect for the diverse cultures that shape our nation.

How to Choose Trail of Tears Research Paper Topics

Selecting a research paper topic on the Trail of Tears requires careful consideration and sensitivity to the historical significance and cultural implications of this tragic event. This section will provide valuable guidance on how to choose compelling and meaningful Trail of Tears research paper topics that delve into different aspects of the Trail of Tears. By following these 10 tips, students can navigate the complexities of this subject and contribute to a deeper understanding of this pivotal moment in American history.

- Define Your Area of Interest : Begin by identifying your area of interest within the Trail of Tears. Are you fascinated by the historical context, the impact on Native American cultures, the political dynamics involved, or the legacy in contemporary society? Narrowing down your focus will help you choose a topic that resonates with your passion and curiosity.

- Explore Different Perspectives : The Trail of Tears was a multi-faceted event with far-reaching consequences. Consider exploring different perspectives, such as the experiences of specific tribes like the Cherokee or the Choctaw, the roles of government officials involved in the removal process, or the viewpoints of white settlers who supported or opposed the removal.

- Examine Cultural and Social Implications : The forced removal of Native American tribes had profound cultural and social implications. Consider topics that delve into the impact on Native American languages, religions, traditions, and family structures. You could also explore the resilience and preservation of cultural identity among the displaced tribes.

- Analyze Political and Legal Aspects : The Trail of Tears was shaped by political decisions and legal mechanisms. Investigate topics related to the treaties, legislation, and court cases that paved the way for the removal, as well as the political motivations behind these actions.

- Study Human Rights and Ethics : The Trail of Tears raises ethical questions about human rights violations and the treatment of indigenous peoples. Explore topics that delve into the ethical considerations of the removal policy, the responsibility of the government, and the lessons it offers for modern-day human rights issues.

- Consider Economic Factors : Economic interests played a significant role in the forced removal of Native American tribes. Trail of Tears research paper topics exploring the economic motivations behind the removal, the impact on the tribes’ economies, and the consequences for both Native Americans and white settlers can provide valuable insights.

- Investigate Resistance and Resilience : Despite the hardships they faced, Native American tribes displayed remarkable resistance and resilience. Trail of Tears research paper topics that highlight the efforts of tribes to resist removal, such as legal challenges, petitions, and peaceful protests, as well as their efforts to rebuild their communities in new territories.

- Examine Intercultural Encounters : The Trail of Tears brought Native American tribes into contact with other cultures, such as white settlers and African Americans. Investigate topics that explore the interactions, conflicts, and exchanges between these different groups during this tumultuous period.

- Explore Art and Literature : Artists and writers have captured the emotions and experiences of the Trail of Tears through various mediums. Consider research paper topics that analyze the portrayal of the removal in art, literature, and media, and how these representations shape public memory and understanding.

- Reflect on Modern Implications : The Trail of Tears has lasting implications in contemporary society. Trail of Tears research paper topics that examine the ongoing impact on Native American communities, the recognition of historical injustices, and the importance of reconciliation and healing can contribute to current discussions on social justice and cultural heritage.

Choosing a research paper topic on the Trail of Tears is a critical step in contributing to the understanding and commemoration of this significant event in American history. By exploring different angles, perspectives, and implications, students can shed light on the complex and poignant story of the forced removal of Native American tribes, providing valuable insights into the legacy and ongoing relevance of the Trail of Tears in the modern world.

How to Write a Trail of Tears Research Paper

Writing a research paper on the Trail of Tears requires careful planning, in-depth research, and a nuanced understanding of historical events and cultural complexities. In this section, we will guide you through the process of crafting a comprehensive and compelling research paper that explores the Trail of Tears and its significance in American history. Follow these 10 tips to ensure your paper effectively communicates the profound impact of this tragic chapter.

- Thoroughly Research the Trail of Tears : Begin your journey by delving into a wide range of reputable sources, including academic books, scholarly articles, primary documents, and online databases. Gain a comprehensive understanding of the historical context, the various tribes involved, the removal process, and the aftermath of the Trail of Tears.

- Develop a Clear Thesis Statement : Your thesis statement is the foundation of your research paper. It should succinctly state the main argument or focus of your paper. Ensure that your thesis statement reflects the specific aspect of the Trail of Tears you intend to explore and the significance of your findings.

- Outline Your Paper’s Structure : Organize your research and ideas by creating a detailed outline for your paper. Include sections for the introduction, literature review, methodology (if applicable), main body paragraphs, analysis, and conclusion. Each section should flow logically and support your thesis.

- Use Diverse Sources and Evidence : To present a well-rounded analysis, utilize a diverse range of sources and evidence. Incorporate historical records, firsthand accounts, official documents, statistical data, and scholarly interpretations. Using varied sources strengthens the credibility of your research.

- Analyze Historical Context and Causes : Devote a section of your research paper to the historical context and causes of the Trail of Tears. Explain the political, economic, and social factors that led to the forced removal of Native American tribes. Provide a comprehensive overview to set the stage for your analysis.

- Address the Impact on Native American Tribes : Explore the profound impact of the Trail of Tears on the affected Native American tribes. Discuss the devastating consequences of forced relocation, loss of ancestral lands, and disruptions to their cultures, languages, and traditions. Highlight the resilience and perseverance of the tribes amidst adversity.

- Evaluate Government Policies and Decisions : Examine the government policies and decisions that led to the Trail of Tears. Analyze the role of President Andrew Jackson, the Indian Removal Act of 1830, and the enforcement of removal treaties. Assess the ethical implications and historical consequences of these policies.

- Analyze Intercultural Encounters and Conflicts : Within your research paper, explore the interactions and conflicts that arose between Native American tribes, white settlers, and government officials during the removal process. Discuss the cultural clashes, misunderstandings, and power dynamics that shaped these encounters.

- Discuss Historical Memory and Commemoration : Address how the Trail of Tears is remembered and commemorated in contemporary society. Explore how different groups interpret and remember this event, and discuss the efforts made to honor the memory of those who suffered during the forced removal.

- Conclude with Reflection and Implications : In your conclusion, restate your thesis and summarize your main findings. Reflect on the lasting implications of the Trail of Tears in shaping American history and the ongoing challenges faced by Native American communities. Offer insights into the importance of understanding this historical event and its relevance in the present day.

By following these tips and conducting rigorous research, you can craft a thought-provoking and insightful research paper that honors the legacy of the Trail of Tears and contributes to a deeper understanding of this tragic chapter in American history.

iResearchNet’s Writing Services:

Your partner in trail of tears research papers.

At iResearchNet, we understand the significance of the Trail of Tears and its impact on American history and Native American communities. We recognize the importance of producing well-researched and insightful papers that explore this tragic chapter in depth. Our team of expert writers, with their academic expertise and profound knowledge of history, is committed to providing students with top-quality, custom-written research papers on the Trail of Tears.

- Expert Degree-Holding Writers : Our writing team consists of highly qualified experts with advanced degrees in history and related fields. They have extensive experience in conducting research on complex historical topics like the Trail of Tears and possess the skills to create engaging and well-structured research papers.

- Custom Written Works : We take pride in delivering 100% original and customized research papers tailored to meet your specific requirements. Our writers approach each paper from scratch, ensuring that the content is unique, well-referenced, and free from any form of plagiarism.

- In-Depth Research : Understanding the complexity of the Trail of Tears and its historical context, our writers conduct thorough research from reputable sources to provide a comprehensive analysis of this significant event. They integrate a diverse range of scholarly materials to ensure the paper is academically robust.

- Custom Formatting : Our writers are well-versed in various citation styles, including APA, MLA, Chicago/Turabian, and Harvard. They meticulously format your research paper according to your preferred style guide and ensure proper citation of sources.

- Top Quality : We prioritize delivering high-quality research papers that exceed your expectations. Our writing team is committed to upholding academic excellence and adhering to the highest standards of writing and research.

- Customized Solutions : We understand that every student’s research paper needs are unique. Our writers tailor their approach to meet your specific instructions, research questions, and academic goals.

- Flexible Pricing : We offer competitive and transparent pricing, ensuring that our services are accessible to students with varying budget constraints. Our flexible pricing options allow you to choose the level of service that best suits your needs.

- Short Deadlines : For students facing tight deadlines, we provide quick turnaround times without compromising on quality. Our writers can efficiently produce well-researched papers in as little as 3 hours.

- Timely Delivery : We recognize the importance of meeting deadlines, and our writers are committed to delivering your research paper on time. We take pride in our prompt and reliable service.

- 24/7 Support : Our customer support team is available round the clock to address any queries or concerns you may have. Feel free to reach out to us at any time, and we will be more than happy to assist you.

- Absolute Privacy : We prioritize the confidentiality of your personal information and ensure that your interactions with our service remain private and secure.

- Easy Order Tracking : With our user-friendly platform, you can easily track the progress of your research paper, communicate with your assigned writer, and stay informed throughout the writing process.

- Money Back Guarantee : We stand behind the quality of our work, and if you are not satisfied with the final paper, we offer a money-back guarantee to ensure your complete satisfaction.

In conclusion, iResearchNet is your trusted partner in producing outstanding Trail of Tears research papers. With our team of expert writers, commitment to quality, and dedication to academic excellence, we are ready to assist you in exploring the profound impact of the Trail of Tears and its significance in American history. Let us help you unleash your potential and excel in your academic journey with our exceptional writing services.

Unleash Your Potential with iResearchNet

Are you struggling to find the right research paper topic on the Trail of Tears? Do you need expert assistance to craft a well-researched and compelling paper that delves deep into this significant chapter in American history? Look no further! iResearchNet is here to support you every step of the way.

Don’t let the challenges of researching and writing on this topic hold you back. Let iResearchNet be your trusted partner in your academic journey. With our expert writers, customized solutions, and commitment to academic excellence, we are here to support you in every way possible.

Take the first step towards producing an exceptional research paper on the Trail of Tears. Contact iResearchNet today and unleash your potential with our top-quality writing services. Together, we can uncover the historical truths and legacies of this tragic chapter in American history.

ORDER HIGH QUALITY CUSTOM PAPER

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

Trail of Tears

By: History.com Editors

Updated: September 26, 2023 | Original: November 9, 2009

At the beginning of the 1830s, nearly 125,000 Native Americans lived on millions of acres of land in Georgia, Tennessee, Alabama, North Carolina and Florida–land their ancestors had occupied and cultivated for generations. But by the end of the decade, very few natives remained anywhere in the southeastern United States. Working on behalf of white settlers who wanted to grow cotton on the Indians’ land, the federal government forced them to leave their homelands and walk hundreds of miles to a specially designated “Indian Territory” across the Mississippi River. This difficult and oftentimes deadly journey is known as the Trail of Tears.

The 'Indian Problem'

White Americans, particularly those who lived on the western frontier, often feared and resented the Native Americans they encountered: To them, American Indians seemed to be an unfamiliar, alien people who occupied land that white settlers wanted (and believed they deserved).

Some officials in the early years of the American republic, such as President George Washington , believed that the best way to solve this “Indian problem” was to simply “civilize” the Native Americans. The goal of this civilization campaign was to make Native Americans as much like white Americans as possible by encouraging them convert to Christianity , learn to speak and read English and adopt European-style economic practices such as the individual ownership of land and other property (including, in some instances in the South, enslaved persons).

In the southeastern United States, many Choctaw, Chickasaw, Seminole, Creek and Cherokee people adopted these customs and became known as the “Five Civilized Tribes.”

Did you know? Indian removal took place in the Northern states as well. In Illinois and Wisconsin, for example, the bloody Black Hawk War in 1832 opened to white settlement millions of acres of land that had belonged to the Sauk, Fox and other native nations.

But the Native Americans’ land, located in parts of Georgia , Alabama , North Carolina , Florida and Tennessee , was valuable, and it grew to be more coveted as white settlers flooded the region. Many of these whites yearned to make their fortunes by growing cotton, and often resorted to violent means to take land from their Indigenous neighbors. They stole livestock; burned and looted houses and towns; committed mass murder ; and squatted on land that did not belong to them.

Worcester v. Georgia

State governments joined in this effort to drive Native Americans out of the South. Several states passed laws limiting Native American sovereignty and rights and encroaching on their territory.

In Worcester v. Georgia (1832), the U.S. Supreme Court objected to these practices and affirmed that native nations were sovereign nations “in which the laws of Georgia [and other states] can have no force.”

Even so, the maltreatment continued. As President Andrew Jackson noted in 1832, if no one intended to enforce the Supreme Court’s rulings (which he certainly did not), then the decisions would “[fall]…still born.” Southern states were determined to take ownership of Indian lands and would go to great lengths to secure this territory.

Indian Removal Act

Andrew Jackson had long been an advocate of what he called “Indian removal.” As an Army general, he had spent years leading brutal campaigns against the Creeks in Georgia and Alabama and the Seminoles in Florida–campaigns that resulted in the transfer of hundreds of thousands of acres of land from Indian nations to white farmers.

As president, he continued this crusade. In 1830, he signed the Indian Removal Act , which gave the federal government the power to exchange Native-held land in the cotton kingdom east of the Mississippi for land to the west, in the “Indian colonization zone” that the United States had acquired as part of the Louisiana Purchase . This “Indian territory” was located in present-day Oklahoma .

The law required the government to negotiate removal treaties fairly, voluntarily and peacefully: It did not permit the president or anyone else to coerce Native nations into giving up their ancestral lands. However, President Jackson and his government frequently ignored the letter of the law and forced Native Americans to vacate lands they had lived on for generations.

In the winter of 1831, under threat of invasion by the U.S. Army, the Choctaw became the first nation to be expelled from its land altogether. They made the journey to Indian Territory on foot (some “bound in chains and marched double file,” one historian writes), and without any food, supplies or other help from the government.

Thousands of people died along the way. It was, one Choctaw leader told an Alabama newspaper, a “trail of tears and death.”

The Indian-removal process continued. In 1836, the federal government drove the Creeks from their land for the last time: 3,500 of the 15,000 Creeks who set out for Oklahoma did not survive the trip.

Treaty of New Echota

The Cherokee people were divided: What was the best way to handle the government’s determination to get its hands on their territory? Some wanted to stay and fight. Others thought it was more pragmatic to agree to leave in exchange for money and other concessions.

In 1835, a few self-appointed representatives of the Cherokee nation negotiated the Treaty of New Echota, which traded all Cherokee land east of the Mississippi — roughly 7 million acres — for $5 million, relocation assistance and compensation for lost property.

To the federal government, the treaty (signed in New Echota, Georgia) was a done deal, but a majority of the Cherokee felt betrayed. Importantly, the negotiators did not represent the tribal government or anyone else. Most Cherokee people considered the Treaty of New Echota fraudulent, and the Cherokee National Council voted in 1836 to reject it.

“The instrument in question is not the act of our nation,” wrote the nation’s principal chief, John Ross, in a letter to the U.S. Senate protesting the Treaty of New Echota. “We are not parties to its covenants; it has not received the sanction of our people.” Nearly 16,000 Cherokees signed Ross’s petition, but Congress approved the treaty anyway.

By 1838, only about 2,000 Cherokees had left their Georgia homeland for Indian Territory. President Martin Van Buren sent General Winfield Scott and 7,000 soldiers to expedite the removal process. Scott and his troops forced the Cherokee into stockades at bayonet point while his men looted their homes and belongings.

Then, they marched the Indians more than 1,200 miles to Indian Territory. Whooping cough, typhus, dysentery, cholera and starvation were epidemic along the way. Historians estimate that more than 5,000 Cherokee died as a result of the journey.

Legacy of the Trail of Tears

By 1840, tens of thousands of Native Americans had been driven off of their land in the southeastern states and forced to move across the Mississippi to Indian Territory. The federal government promised that their new land would remain unmolested forever, but as the line of white settlement pushed westward, “Indian Country” shrank and shrank. In 1907, Oklahoma became a state and Indian Territory was considered lost.

A 2020 decision by the Supreme Court, however, highlighted ongoing interest in Native American territorial rights. In a 5-4 decision, the Court ruled that a huge area of Oklahoma is still considered an American Indian reservation .

This decision left the state of Oklahoma unable to prosecute Native Americans accused of crimes on those tribal lands — only federal and tribal law enforcement can prosecute such crimes. (A later 2022 Supreme Court decision rolled back some provisions of the 2020 court finding.)

The Trail of Tears — actually a network of different routes — is over 5,000 miles long and covers nine states: Alabama, Arkansas, Georgia, Illinois, Kentucky, Missouri, North Carolina, Oklahoma and Tennessee. Today, the Trail of Tears National Historic Trail is run by the National Park Service and portions of it are accessible on foot, by horse, by bicycle or by car.

Trail of Tears. NPS.gov . Trail of Tears. Museum of the Cherokee Indian . The Treaty of New Echota and the Trail of Tears. North Carolina Department of Natural and Cultural Resources . The Treaty That Forced the Cherokee People from Their Homelands Goes on View. Smithsonian Magazine . Justices rule swath of Oklahoma remains tribal reservation. Associated Press . Justices limit 2020 ruling on tribal lands in Oklahoma. Associated Press .

HISTORY Vault: Native American History

From Comanche warriors to Navajo code talkers, learn more about Indigenous history.

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

MA in American History : Apply now and enroll in graduate courses with top historians this summer!

- AP US History Study Guide

- History U: Courses for High School Students

- History School: Summer Enrichment

- Lesson Plans

- Classroom Resources

- Spotlights on Primary Sources

- Professional Development (Academic Year)

- Professional Development (Summer)

- Book Breaks

- Inside the Vault

- Self-Paced Courses

- Browse All Resources

- Search by Issue

- Search by Essay

- Become a Member (Free)

- Monthly Offer (Free for Members)

- Program Information

- Scholarships and Financial Aid

- Applying and Enrolling

- Eligibility (In-Person)

- EduHam Online

- Hamilton Cast Read Alongs

- Official Website

- Press Coverage

- Veterans Legacy Program

- The Declaration at 250

- Black Lives in the Founding Era

- Celebrating American Historical Holidays

- Browse All Programs

- Donate Items to the Collection

- Search Our Catalog

- Research Guides

- Rights and Reproductions

- See Our Documents on Display

- Bring an Exhibition to Your Organization

- Interactive Exhibitions Online

- About the Transcription Program

- Civil War Letters

- Founding Era Newspapers

- College Fellowships in American History

- Scholarly Fellowship Program

- Richard Gilder History Prize

- David McCullough Essay Prize

- Affiliate School Scholarships

- Nominate a Teacher

- Eligibility

- State Winners

- National Winners

- Gilder Lehrman Lincoln Prize

- Gilder Lehrman Military History Prize

- George Washington Prize

- Frederick Douglass Book Prize

- Our Mission and History

- Annual Report

- Contact Information

- Student Advisory Council

- Teacher Advisory Council

- Board of Trustees

- Remembering Richard Gilder

- President's Council

- Scholarly Advisory Board

- Internships

- Our Partners

- Press Releases

History Resources

Perspectives on the Trail of Tears

By elizabeth berlin taylor, introduction.

In this lesson, student groups will design and create a poster containing facts about the Trail of Tears as well as a collage and concluding statement expressing the group’s feelings about the event.

The Trail of Tears was the result of Andrew Jackson’s policy of Indian Removal in the Southeastern United States. While Jackson’s designs on Indian territory east of the Mississippi River involved Indian nations such as the Cherokees, Seminoles, Chickasaws, Choctaws, and Creeks, as well as others from approximately 1814 until 1840, "the Trail of Tears" refers to the forced march of Cherokees from Georgia to Oklahoma from 1838 to 1839. This episode, legitimized by the disputed Treaty of New Echota, resulted in thousands of deaths and the removal of the Cherokee Nation from its ancestral homelands.

- Map of the Cherokee Nation in Georgia, 1827 , David Rumsey Historical Map Collection

- Map of Cherokee Removal Routes , Smithsonian Institution

- Interactive map of the Trail of Tears National Historic Trail (Scroll down and click on "The Trail of Tears National Historic Trail")

- The Trail of Tears by Robert Lindneux, 1942

Secondary Sources

- Cherokee Nation Timeline

- "What happened on the Trail of Tears?"

Primary Sources

- "General Winfield Scott’s Address to the Cherokee Nation," May 10, 1838

- Letter from Chief John Ross protesting the Treaty of New Echota

- Transcript of President Andrew Jackson’s message to Congress "On Indian Removal" (1830)

- Treaty of New Echota , final paragraph of Article 1

Essential Question

What incidents led to the Trail of Tears and what is your perspective of this event?

- Students will be able to read and understand primary and secondary documents that are germane to the events and points of view of the Trail of Tears.

- Students will be able to communicate data about the Trail of Tears on a poster.

- Students will be able to create a collage and a statement that captures the group’s feelings about the Trail of Tears.

Ask students the question: "Does the United States government have the right to make you move out of your house? Why or why not?" After students spend about two minutes writing responses to these questions, ask them to share their answers and respond to each other. As a follow-up question, ask students what they would do if they were required to move by their government.

- Introduce background information on the Trail of Tears via a very brief lecture or discussion.

- Project the maps of the Cherokee Nation in Georgia, 1830, and the Cherokee Removal Routes. Discuss the distance that the Cherokees walked and conditions they endured. If you have access to computer technology, have students investigate the interactive map of the Trail of Tears to understand how long the march was and would be today.

- Project The Trail of Tears by Robert Lindneux. Have students discuss what is happening in the painting and how its subjects are depicted.

- Divide the class into groups of four and distribute an information packet to each group. The packet should contain four copies of the two secondary sources and one copy of each primary source. It would be most effective to keep the materials in a folder.

- Ask students to read the secondary sources individually. Then as a group, have students write one paragraph that responds to the question, "What was the Trail of Tears?"

- Next, ask each student in the group to read one of the primary sources and complete the " Who, What, Where, and When " worksheet. Group members should then share information from their documents with the group.

- Conclude this day’s class by asking for volunteers to explain the events and share their perceptions of the Trail of Tears.

Ask students to return to their groups and review the information they discovered in the previous class period. Hand out the Perspectives on the Trail of Tears poster template to each group. Ask students to answer the following questions in the corners of the poster:

- What was the Trail of Tears?

- Who was removed (and from where were they removed)? Where did they resettle?

- What was John Ross’s opinion of Indian Removal?

- What was Andrew Jackson’s opinion of Indian Removal?

In the center of the poster, have students create a collage showing how the group feels about the Trail of Tears. Underneath the collage, the group should write a one-sentence statement explaining their feelings about the Trail of Tears.

After they complete their work, debrief students on the material they have learned. Pose the concluding question: "Could another removal of an ethnic group happen in the present-day United States?"

Students may research the experiences of other Indian nations subjected to removal as a result of Andrew Jackson’s policies and write a short essay explaining their research.

Stay up to date, and subscribe to our quarterly newsletter.

Learn how the Institute impacts history education through our work guiding teachers, energizing students, and supporting research.

Articles on Trail of Tears

Displaying all articles.

Joel Roberts Poinsett: Namesake of the poinsettia, enslaver, secret agent and perpetrator of the ‘Trail of Tears’

Lindsay Schakenbach Regele , Miami University

Gangsters are the villains in ‘Killers of the Flower Moon,’ but the biggest thief of Native American wealth was the US government

Torivio Fodder , University of Arizona

The story of Ohio’s ancient Native complex and its long journey for recognition as a World Heritage site

Stephen Warren , University of Iowa

In Danielle Smith’s fantasy Alberta, Indigenous struggle is twisted to suit settlers

Daniel Heath Justice , University of British Columbia

Cherokee Nation wants to send a delegate to the House – it’s an idea older than Congress itself

Julie Reed , Penn State

Who gets Cherokee citizenship has long been a struggle between the tribe and the US government

Aaron Kushner , Arizona State University

Indigenous Peoples Day comes amid a reckoning over colonialism and calls for return of Native land

Abel R. Gomez , Syracuse University

Oklahoma is – and always has been – Native land

Dwanna L. McKay , Colorado College

The long history of separating families in the US and how the trauma lingers

Jessica Pryce , Florida State University

Related Topics

- African Americans

- Cherokee Nation

- Indian Removal Act

- Indigenous peoples

- Native American culture

- Native Americans

- Religion and society

- US government

Top contributors

Cherokee Nation citizen, Professor of Critical Indigenous Studies and English, University of British Columbia

Executive Director, The Florida Institute for Child Welfare, Florida State University

PhD Candidate, Religion Department, Syracuse University

Assistant Professor of Race, Ethnicity, and Indigenous Studies, Colorado College

Postdoctoral Scholar, School of Civic and Economic Thought and Leadership, Arizona State University

Associate Professor in History, Penn State

Professor of History and Program Coordinator, Native American and Indigenous Studies, University of Iowa

Indigenous Governance Program Manager and Professor of Practice, University of Arizona

Associate Professor of History, Miami University

- X (Twitter)

- Unfollow topic Follow topic

- Skip to global NPS navigation

- Skip to this park navigation

- Skip to the main content

- Skip to this park information section

- Skip to the footer section

Exiting nps.gov

Alerts in effect, trailwide research.

Last updated: August 3, 2023

Park footer

Contact info, mailing address:.

National Trails Office Regions 6|7|8 Trail of Tears National Historic Trail 1100 Old Santa Fe Trail Santa Fe, NM 87505

Stay Connected

- About Native Knowledge 360°

- Essential Understandings

- Featured Items

- Search NK360° Educational Resources

- Instructional Resources

- Informational Resources

- Resources Beyond the Museum

- Group Information

- imagiNATIONS Activity Center

- About Native Americans

- About Virtual Teacher Institute

The Trail of Tears: A Story of Cherokee Removal

The Cherokee Nation was one of many Native Nations to lose its lands to the United States. The Cherokee tried many different strategies to avoid removal, but eventually, they were forced to move. This interactive uses primary sources, quotes, images, and short videos of contemporary Cherokee people to tell the story of how the Cherokee Nation resisted removal and persisted to renew and rebuild their nation. Explore this resource to better understand the impact of removal and how the Cherokee still celebrate and sustain important cultural values and practices.

Resource Information

1: American Indian Culture Native people continue to fight to maintain the integrity and viability of indigenous societies. American Indian history is one of cultural persistence, creative adaptation, renewal, and resilience.

5: Individuals, Groups, and Institutions Today, American Indian governments uphold tribal sovereignty and promote tribal culture and well-being.

6: Power, Authority, and Governance A variety of political, economic, legal, military, and social policies were used by Europeans and Americans to remove and relocate American Indians and to destroy their cultures. U.S. policies regarding American Indians were the result of major national debate. Many of these policies had a devastating effect on established American Indian governing principles and systems. Other policies sought to strengthen and restore tribal self-government.

LEARN MORE ABOUT ESSENTIAL UNDERSTANDINGS →

D3.4.6-8 Develop claims and counterclaims while pointing out the strengths and limitations of both.

D3.4.9-12 Refine claims and counterclaims attending to precision, significance, and knowledge conveyed through the claim while pointing out the strengths and limitations of both.

CCCSS.ELA-LITERACY.CCRA.R.1 Read closely to determine what the text says explicitly and to make logical inferences from it; cite specific textual evidence when writing or speaking to support conclusions drawn from the text.

6–8 Grades CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RL.6.1 Cite textual evidence to support analysis of what the text says explicitly as well as inferences drawn from the text.

6–8 Grades CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RL.7.1 Cite several pieces of textual evidence to support analysis of what the text says explicitly as well as inferences drawn from the text.

6–8 Grades CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RL.8.1 Cite the textual evidence that most strongly supports an analysis of what the text says explicitly as well as inferences drawn from the text.

9–10 Grades CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RL.9-10.1 Cite strong and thorough textual evidence to support analysis of what the text says explicitly as well as inferences drawn from the text.

11–12 Grades CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RL.11-12.1 Cite strong and thorough textual evidence to support analysis of what the text says explicitly as well as inferences drawn from the text, including determining where the text leaves matters uncertain.

Learning Resources

Teaching beyond the "trail of tears", read for understanding:.

This Learning Resource explores the forced removal of Native Americans from their ancestral lands in the southeast United States in the 1830's-1850's. It was developed as many schools were closed during the COVID-19 global pandemic. Suggested tips for teachers and students engaging in remote learning are included, and some learning strategies and directions have been modified to assist schools with both face to face and virtual instruction.

Key Vocabulary

Annex – forcibly adding new land to a state or nation

Assimilate – for a person or group of people to become similar to others in habits or culture

Atrocities – violent, cruel acts

Barbarity - cruelty, inhumane treatment

Blasphemous – being disrespectful to religion or God

Covenant – An agreement in a deed to real estate (land/property) that restricts future use of the property, often enforceable against future owners. Restrictive covenants based on race were declared unconstitutional in 1949

Inferior – a lower political or social status of a group of people

Missionary - someone who promotes his religion to others in an effort to recruit new followers

Plunder - to steal valuables from others

Reconciliation – restoring positive relations between groups or individuals

Sovereign – government authority over others

Vociferations - speaking out in protest

How did the Indian Removal Act impact Native Americans?

Between 1830 and 1850, over 60,000 Native Americans were forcibly removed from their ancestral homelands in the southeast region of the United States, under President Andrew Jackson’s Indian Removal Act of 1830. These included members of the Chickasaw, Choctaw, Creek, Seminole, and Cherokee peoples, as well as other mixed-race people and enslaved Africans who previously lived among these nations.

Forced to march over a thousand miles, several thousand died and many were buried in unmarked graves along the route often referred to as “The Trail of Tears.” Those who survived were displaced and escorted by state or local militias into government-designated Indian Territory in present-day Oklahoma.

Take a few minutes to study this painting, The Trail of Tears , by artist Robert Lindneux , depicting their Journey of Injustice.

Select one person from the painting to analyze by completing the following:

- List five details about this person.

- What is the mood of this painting? What feeling does it give you?

- What do you think is happening?

To learn more about the Trail of Tears, read this excerpt on Bunk – “Work of Barbarity”: Eyewitness account excerpt Missionary journal, June 16, 1838.

“Work of Barbarity”: An Eyewitness Account of the Trail of Tears

A missionary's account of the atrocities perpetrated against Cherokees shows that the Trail of Tears is no laughing matter.

www.bunkhistory.org

After reading the excerpt, turn and talk to a partner, or if working remotely, use the chat box or other collaboration strategy recommended by your teacher to Think - Pair - Share three examples of unfair treatment experienced by the Cherokees as explained by a missionary who witnessed Indian removal. You may choose to continue reading the complete article by selecting the “View on...” button.

Your teacher may ask you to record your answers on an exit ticket.

Why were the Cherokee and other Native Americans removed from their lands in the 1830s?

Watch this brief video on the PBS LearningMedia site to learn more about President Andrew Jackson’s use of the Indian Removal Act.

Trail of Tears | PBS LearningMedia

In this video segment adapted from American Experience: "We Shall Remain," reenactments help tell the story of how the Cherokee people were forced from their lands in the southeast.

www.pbslearningmedia.org

While watching the video, complete the following S-I-T prompts:

- One Surprising fact or idea

- One Interesting fact or idea

- One Troubling fact or idea

Afterwards, turn and talk with your partner sharing some of your reflections. If working remotely, your teacher may provide opportunities to collaborate with classmates using video conferencing, access to an online chat feature, or breakout rooms.

Next, examine the routes taken by different Native American tribes at part of the Indian Removal Act.

To recognize the events of this journey, the National Park Service has established a National Historic Trail along the routes of the Trail of Tears. Go to the NPS website to discover more information about National Historic Trails.

What is a National Historic Trail (NHT)? - Trail Of Tears National Historic Trail (U.S. National Park Service)

www.nps.gov

Next, investigate the interactive map that follows the Trail of Tears routes. Click on locations that are near you or in which you are interested. Notice the variety of historically significant places you can visit including homes, museums, and visitor centers.

Places To Go - Trail Of Tears National Historic Trail (U.S. National Park Service)

You can also see various exhibits, photos, and videos if you want to learn even more about the Trail of Tears.

Photos & Multimedia - Trail Of Tears National Historic Trail (U.S. National Park Service)

photos and multimedia

What steps did leaders take to resolve the arguments over Native Americans’ lands?

Some Native American tribes, like the Seminole tribe of Florida, physically resisted removal from their lands. Others fought using legal means. In the case of Cherokee Nation v. Georgia (1831), the Cherokee tribe asserted that Georgia laws passed to take their lands were a violation of previous land treaties. The Supreme Court dismissed the case, noting that the Cherokee Nation was not a foreign nation within the U.S. boundaries, and thus the federal government had no right to interfere in the actions of the state of Georgia.

However, one year later, the Supreme Court ruled very differently when a Christian minister named Samuel Worcester sued the state of Georgia challenging that it did not have a right to regulate activities on the Cherokee lands.

Learn more by reading the brief article about the court case Worcester v. Georgia (1832) and complete the chart explaining the role of each leader regarding Indian removal. The information about Samuel Worcester has been completed for you.

Worcester v. Georgia (1832)

In the court case Worcester v. Georgia, the U.S. Supreme Court held in 1832 that the Cherokee Indians constituted a nation holding distinct sovereign powers. Although the decision became the foundatio

www.georgiaencyclopedia.org

NAH Leaders in Worcester v Georgia

New American History

docs.google.com

Read the following quotes made by key leaders in the conflict over Native American lands:

“To save him from this alternative, or perhaps utter annihilation, the General Government kindly offers him a new home, and proposes to pay the whole expense of his removal and settlement."

“The Indian nations had always been considered as distinct, independent political communities retaining their original natural rights as the undisputed possessors of the soil.”

“We are denationalized; we are disfranchised. We are deprived of membership in the human family! We have neither land nor home, nor resting place that can be called our own.”

Select your favorite quote listed above and use this link to create a SketchQuote . Sketchnotes are a form of visual note taking that allows you to combine hand lettering and sketches to annotate a variety of content, including quotes. You can also use information from your chart to add to your SketchQuote.

Your teacher may ask you to share your SketchQuote or record your answers on an exit ticket.

What challenges are Native American tribes facing today?

Using the Bunk website, investigate the modern issues facing Native American tribes by searching “Native Americans” and clicking on one of the articles that interests you.

Notice the related content to the right of the excerpt. The stack of cards contains other articles, maps or content somehow connected to the original article on the left of the screen.

The connection icons located to the left of the cards here represent Idea, Person, Place and Time, which refers to a connected article from a different time period. These icons and the connected articles you see on the screen may change over time as new content is added to Bunk.

Select the “ View Connections ” button.

Notice how the screen changes.

Take some time to explore this and other connections to the original excerpt you chose. Notice how each of the connections icons (Idea, Place, Person, Time) leads you to a new stack of cards with different articles and topics. Each of these topics in turn has a list of “tags” below the icon to help guide you towards new and different content.

Now that you know how Bunk Connections work, you will be building a collection * of articles to help you answer the question, What challenges are Native American tribes facing today?

To build a collection, click on the first article that you have chosen and scroll down to the bottom of the excerpt to locate the Add to Collection button.

You will see a box labeled “Add a note.” This is where you will annotate, or write a brief description of how this excerpt helps you answer the question. Be sure to save your note using the green Save Note button. If you decide you want to remove an excerpt from your collection, you can return to the excerpt and select the red “Remove from Collection button.

Continue adding 3-5 excerpts to your collection, exploring the connections on Bunk and annotating each one. Be sure you are saving as you go along. Once you are finished, you may locate the blue bar at the bottom of your screen and select finalize. You MUST save and finish this during one class period.

You will need to give your collection a title, and add your name and teacher’s name/class period. You may reorder the excerpts, and edit or delete a note or excerpt until you are satisfied with your work. Be sure you SAVE CHANGES before you select the green Complete Collection button.

You will need to use an email address to share or retrieve your collection. For safety reasons, your teacher may choose to have you use their school email address, or they may use the Assignment feature instead of Collections on Bunk.

Keep checking back on Bunk for more content. New is added every day!

*(Note: Your teacher may prefer you to complete an assignment they created in Bunk if your school does not allow students to access email. This is similar to the Collections feature in Bunk).

How has the modern United States government addressed past and current issues facing Native Americans?

In recent years, the United States government has begun acknowledging past transgressions against Indigenous populations in our country. Read this excerpt of the Senate Joint Resolution 14 from the 111th Congress (2009).

Text - S.J.Res.14 - 111th Congress (2009-2010)

Text for S.J.Res.14 - 111th Congress (2009-2010): A joint resolution to acknowledge a long history of official depredations and ill-conceived policies by the Federal Government regarding Indian tribes and offer an apology to all Native Peoples on behalf of the United States.

www.congress.gov

Answer the following questions:

- Which three provisions do you think are the most significant?

- Does the apology go far enough? Why or why not?

- What additional steps should the US government take in its relationship with Native American tribes?

In an effort to make all Americans more aware of historic Native American territories, the U.S. Department of Arts and Culture is calling “on all individuals and organizations to open public events and gatherings with acknowledgment of the traditional Native inhabitants of the land.” If you would like to join this action, you can read more about it on the USDAC site .

Not all Indigenous peoples are in agreement with the practice of using a Land Acknowledgement. This Bunk excerpt explores the topic in more depth. Before adding a Land Acknowledgement to the agenda for a public event, a public-facing document, or as part of a learning experience for students, use the Native-land.ca map territories map to access and contact the local nations in your area and open a dialogue on the topic.

#HonorNativeLand — U.S. Department of Arts and Culture

Next, determine which Native American tribes lived in your area by using this map .

NativeLand.ca

Welcome to Native Land. This is a resource for North Americans (and others) to find out more about local Indigenous territories and languages.

native-land.ca

Finally, you can share this information by creating a graphic design that you can share in your school, community, or via social media. This poster is one example created by others that is displayed on the USDAC site .

Your teacher may ask you to share your poster or record your answers on an exit ticket.

Brownback, Sam. “Text - S.J.Res.14 - 111th Congress (2009-2010): A Joint Resolution to Acknowledge a Long History of Official Depredations and Ill-Conceived Policies by the Federal Government Regarding Indian Tribes and Offer an Apology to All Native Peoples on Behalf of the United States.” Congress.gov, August 6, 2009. https://www.congress.gov/bill/111th-congress/senate-joint-resolution/14/text .

“Cherokee Nation v. Georgia.” Federal Judicial Center. Accessed July 24, 2020. https://www.fjc.gov/history/timeline/cherokee-nation-v-georgia .

Garrison, Tim Alan. “Worcester v. Georgia (1832).” New Georgia Encyclopedia. New Georgia Encyclopedia, February 20, 2018. https://www.georgiaencyclopedia.org/articles/government-politics/worcester-v-georgia-1832 .

“Honor Native Land: A Guide and Call to Acknowledgement.” U.S. Department of Arts and Culture. Accessed August 1, 2020. https://usdac.us/nativeland .

Jones, Evan, and Matthew Dessem. “‘Work of Barbarity’: An Eyewitness Account of the Trail of Tears.” Bunk History. Slate, February 10, 2019. https://www.bunkhistory.org/resources/3885 .

Lindneux, Robert. “Trail of Tears.” Painting, 1942. http://robertlindneux.com/art/lindneux-at-woolarco/ .

Native American Removal from the Southeast . National Geographic . National Geographic . Accessed July 24, 2020. https://www.nationalgeographic.org/thisday/may28/indian-removal-act/ .

Native Land. Native Land Digital. Accessed August 1, 2020. https://native-land.ca/ .

Parker, Bryan D. You Are on Traditional Land . Honor Native Land . U.S. Department of Arts and Culture, October 1, 2017. https://encrypted-tbn0.gstatic.com/images?q=tbn%3AANd9GcQH6z0rb-sxULDqJhvblfa0hg6A80aHYS80fA&usqp=CAU .

Pillar, Wendy, and Heather Marshall. “NAH Sketchquotes.” Google Docs. Google, June 24, 2020. https://docs.google.com/document/d/1OpRRe9eK-xyb9UOY-AtEMCFjAtC7bQSuiAQcVAyXKcc/edit .

“Places To Go Trail of Tears Interactive Map.” National Parks Service. U.S. Department of the Interior, November 18, 2019. https://www.nps.gov/trte/planyourvisit/places-to-go.htm .

President Jackson's Message to Congress "On Indian Removal." December 6, 1830. Records of the United States Senate, 1789‐1990. Record Group 46. Records of the United States Senate, 1789‐1990. National Archives and Records Administration. https://www.nps.gov/museum/tmc/MANZ/handouts/Andrew_Jackson_Annual_Message.pdf

Ross, John. “Letter from Chief John Ross ‘To the Senate and House of Representatives September 28, 1836.” PBS. Public Broadcasting Service. Accessed July 15, 2020. https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/aia/part4/4h3083t.html .

“Samuel A. Worcester, Plaintiff in ERROR v. THE STATE OF GEORGIA.” Legal Information Institute. Legal Information Institute. Accessed July 15, 2020. https://www.law.cornell.edu/supremecourt/text/31/515 .

Sobo, E., Lambert, M., & Lambert, V. (2021, October 7). Land acknowledgments meant to honor indigenous people too often do the opposite. Bunk History. Retrieved from https://www.bunkhistory.org/resources/8864 .

Trail of Tears . PBS LearningMedia . American Experience, 2020. https://vpm.pbslearningmedia.org/resource/akh10.socst.ush.exp.trail/trail-of-tears/ .

“Trail of Tears Photos & Multimedia.” National Parks Service. U.S. Department of the Interior, November 22, 2019. https://www.nps.gov/trte/learn/photosmultimedia/index.htm .

This work by New American History is licensed under a Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) International License . Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at newamericanhistory.org.

Comments? Questions?

Let us know what you think about this Learning Resource. We’d also love to hear other ideas or answer questions from you!

Primary Sources: Native Americans - American Indians - Indigenous Americans: Trail of Tears

- Assimilation & Removal

- French and Indian War

- Indian Wars

- Alcatraz Occupation

- Dakota Access Pipeline/Standing Rock

- Little Big Horn

- Osage Indian Murders

- Trail of Broken Treaties/BIA Takeover (1972)

- Trail of Tears

- Wounded Knee Massacre

- Wounded Knee Occupation

- American West This link opens in a new window

- Bureau of Indian Affairs

- Law & Government

- AIM: American Indian Movement

- Captivity Narratives

- Personal Narratives

- Movies & TV & Radio

- Visual & Fine Arts

- Oral History

- Native American Periodicals This link opens in a new window

- Notable People

- Primary Sources Home

Online Sources: Trail of Tears

- Digital Library of Georgia Search for "Trail of Tears" to locate letters, images, etc. more... less... "The Digital Library of Georgia is a gateway to Georgia's history and culture found in digitized books, manuscripts, photographs, government documents, newspapers, maps, audio, video, and other resources. "

- Gen. Winfield Scott's Address to the Cherokee Nation (May 10, 1838) more... less... Source: Edward J. Cashin (ed.), A Wilderness Still The Cradle of Nature: Frontier Georgia (Savannah: Beehive Press, 1994), pp. 137-38

- Indian-Pioneer Papers Collection University of Oklahoma - Western History Collections more... less... "The Indian-Pioneer Papers oral history collection spans from 1861 to 1936. It includes typescripts of interviews conducted during the 1930s by government workers with thousands of Oklahomans regarding the settlement of Oklahoma and Indian territories, as well as the condition and conduct of life there. Consisting of approximately 80,000 entries, the index to this collection may be accessed via personal name, place name, or subject."

- Indian Removal Act: Primary Documents in American History

- Major General Winfield Scott’s Order No. 25 Regarding the Removal of Cherokee Indians to the West more... less... 5/17/1838 Records of U.S. Army Continental Commands National Archives Identifier: 6172200

- President Andrew Jackson's Message to Congress 'On Indian Removal' (1830) more... less... "On December 6, 1830, in his annual message to Congress, President Andrew Jackson informed Congress on the progress of the removal of Indian tribes living east of the Mississippi River to land in the west."

- DPLA: Primary Source Set: Cherokee Removal and the Trail of Tears Digital Public Library of America more... less... "This primary source set uses documents, images, and music to reveal the story of Cherokee removal, which is part of a larger story known as the Trail of Tears. Thousands of Native Americans—Chickasaw, Creek Choctaw, Seminole, and Cherokee—suffered through this forced relocation."

- See Also Assimilation & Removal section

- The Trail of Tears Through Arkansas more... less... Material from the University of Arkansas at Little Rock’s Sequoyah National Research Center

- Treaty with the Cherokee, 1835, Page 439

- “Our Hearts are Sickened” more... less... "Chief John Ross was the principal chief of the Cherokee in Georgia; in this 1836 letter addressed to “the Senate and House of Representatives,” Ross protested as fraudulent the Treaty of New Echota that forced the Cherokee out of Georgia. In 1838, federal troops forcibly displaced the last of the Cherokee from their homes; their trip to Indian Territory (Oklahoma) is known as the “Trail of Tears.” "

Book Sources: Trail of Tears

- A selection of books/e-books available in Trible Library.

- Click the title for location and availability information.

Search for More

- Suggested terms to look for include - diary, diaries, letters, papers, documents, documentary or correspondence.

- Combine these these terms with the event or person you are researching. (example: civil war diary)

- Also search by subject for specific people and events, then scan the titles for those keywords or others such as memoirs, autobiography, report, or personal narratives.

- << Previous: Trail of Broken Treaties/BIA Takeover (1972)

- Next: Wounded Knee Massacre >>

- Last Updated: Apr 11, 2024 10:38 AM

- URL: https://cnu.libguides.com/psnativeamericans

- Locations and Hours

- UCLA Library

- Research Guides

American Indian Studies

- Indian Removal and the Trail of Tears

- Reference Sources

- Statistics and Demographics

- American Indian Movement

- California and the West

- Colonialism and Settlement

- Education and Boarding Schools

Primary Sources

- Land and Legal Issues

- Other Primary Sources

- Writing the Paper

- Dissertations and Theses

- Andrew Jackson Papers The Andrew Jackson Papers collection documents Jackson's life in its several phases including his Indian policy as President.

- Cherokee Removal and the Trail of Tears Primary source set and teaching guide from the Digital Public Library of America.

- Indian Removal Act: Primary Documents in American History Digital materials at the Library of Congress related to the Indian Removal Act of 1830 and its after-effects, as well as links to external websites and a selected print bibliography.

- << Previous: Education and Boarding Schools

- Next: Land and Legal Issues >>

- Last Updated: Apr 1, 2024 9:53 AM

- URL: https://guides.library.ucla.edu/american-indian

Family Stories from the Trail of Tears

Edited by Lorrie Montiero

Table of Contents

Alexander, jobe, life story of her grandfather, washington lee, cherokee indian, carnes, solomon, incidents of the trail of tears.

Cook, Wallace

Davis, Susanna Adair

Dodge, rachel, fleming, effie oakes, removal to ind. ty., guernsey, charles, harnage, w. w., migration to oklahoma, receives formal notice, the migration to the west of the muskogee, james, rhoda, removal to indian territory, lattimer, josephine usray, lewis, d. b., mann, richard, mcgirt, dick, life and experience of a cherokee woman, the migration, pierce, nannie buchanan, purcell, joe, the trail of tears, migration of the creeks, vann, e. f., men and boys walked, interview with mr. ellis waterkiller, life and customs after migration, source of information received from a personal interview., the removal as told to mrs. watts by her grandparents, divided into detachments, old indian days, the trail of tears., immigration from alabama, agnew, mary cobb.

May 25, 1937 L. W. Wilson Field Worker An Interview with Mary Cobb Agnew; 917 North M Street; Muskogee, Oklahoma

My name was Mary Cobb and I was married to Walter S. Agnew before the Civil War.

I was born in Georgia on May 19, 1840. My mother was a Cherokee woman and my father was a white man. I was only four years old when my parents came to the Indian Territory and I am now ninety-three years old.

My mother and father died when I was but seven years old and I was raised by an aunt, my mother's sister. I never attended school and my education is practical except what I was taught by my husband.

My parents did not come to the Territory on the "Trail of Tears" but my grandparents on my mother's side did. I have heard them say that the United States Government drove them out of Georgia. The Cherokees had protested to the bitter end. Finally the Cherokees knew that they had to go some place because the white men would kill their cattle and hogs and would even burn their houses in Georgia. The Cherokees came a group at a time until all got to the Territory. They brought only a few things with them traveling by wagon train. Old men and women, sick men and women would ride but most of them walked and the men in charge drove them like cattle and many died enroute and many other Cherokees died in Tennessee waiting to cross the Mississippi River. Dysentery broke out in their camp by the river and many died, and many died on the journey but my grandparents got through all right.

I have heard my grandparents say that after they got out of the camp, and even before they left Georgia, many Cherokees were taken sick and later died.

The Cherokees came through Tennessee, Kentucky, part of Missouri and then down to Indian Territory on the "Trail of Tears".

Some Cherokees were already in the country around Evansville, Arkansas, before my grandparents came. They called them Western Cherokees. It was in 1838 when my grandparents came and I heard them say it was in the winter time and all suffered with cold and hunger.

My mother and father remained in Georgia about six years after Mother's folk's came on the "Trail of Tears" and Mother worried continually about her parents. Then when I was four years old, I with my parents and other kin, came west to join my grandparents. I don't know why the Government let Mother stay longer than the rest of the Cherokees in Georgia unless it was because she married a white man. We came by wagons to Memphis, Tennessee. At Memphis we took a steamboat and finally landed at Fort Gibson, Indian Territory, in June, 1844. I don't know how long it took us to come from Memphis nor do I remember the names of the towns we came through but I have heard my folks say that we had to change boats two or three times because the rivers became shallow and we had to change to smaller boats.

After our arrival at Fort Gibson, Indian Territory, we met our kinspeople in the Flint District and settled in the Territory a short way from Evansville, Arkansas. It was in the Flint District and around Fort Gibson that I grew to be a young lady.

May 3, 1938 Jesse S. Bell-Investigator Indian-Pioneer History, S-149 Interview with Jobe Alexander Proctor, Oklahoma