How to write a research plan: Step-by-step guide

Last updated

30 January 2024

Reviewed by

Short on time? Get an AI generated summary of this article instead

Today’s businesses and institutions rely on data and analytics to inform their product and service decisions. These metrics influence how organizations stay competitive and inspire innovation. However, gathering data and insights requires carefully constructed research, and every research project needs a roadmap. This is where a research plan comes into play.

Read this step-by-step guide for writing a detailed research plan that can apply to any project, whether it’s scientific, educational, or business-related.

- What is a research plan?

A research plan is a documented overview of a project in its entirety, from end to end. It details the research efforts, participants, and methods needed, along with any anticipated results. It also outlines the project’s goals and mission, creating layers of steps to achieve those goals within a specified timeline.

Without a research plan, you and your team are flying blind, potentially wasting time and resources to pursue research without structured guidance.

The principal investigator, or PI, is responsible for facilitating the research oversight. They will create the research plan and inform team members and stakeholders of every detail relating to the project. The PI will also use the research plan to inform decision-making throughout the project.

- Why do you need a research plan?

Create a research plan before starting any official research to maximize every effort in pursuing and collecting the research data. Crucially, the plan will model the activities needed at each phase of the research project .

Like any roadmap, a research plan serves as a valuable tool providing direction for those involved in the project—both internally and externally. It will keep you and your immediate team organized and task-focused while also providing necessary definitions and timelines so you can execute your project initiatives with full understanding and transparency.

External stakeholders appreciate a working research plan because it’s a great communication tool, documenting progress and changing dynamics as they arise. Any participants of your planned research sessions will be informed about the purpose of your study, while the exercises will be based on the key messaging outlined in the official plan.

Here are some of the benefits of creating a research plan document for every project:

Project organization and structure

Well-informed participants

All stakeholders and teams align in support of the project

Clearly defined project definitions and purposes

Distractions are eliminated, prioritizing task focus

Timely management of individual task schedules and roles

Costly reworks are avoided

- What should a research plan include?

The different aspects of your research plan will depend on the nature of the project. However, most official research plan documents will include the core elements below. Each aims to define the problem statement , devising an official plan for seeking a solution.

Specific project goals and individual objectives

Ideal strategies or methods for reaching those goals

Required resources

Descriptions of the target audience, sample sizes , demographics, and scopes

Key performance indicators (KPIs)

Project background

Research and testing support

Preliminary studies and progress reporting mechanisms

Cost estimates and change order processes

Depending on the research project’s size and scope, your research plan could be brief—perhaps only a few pages of documented plans. Alternatively, it could be a fully comprehensive report. Either way, it’s an essential first step in dictating your project’s facilitation in the most efficient and effective way.

- How to write a research plan for your project

When you start writing your research plan, aim to be detailed about each step, requirement, and idea. The more time you spend curating your research plan, the more precise your research execution efforts will be.

Account for every potential scenario, and be sure to address each and every aspect of the research.

Consider following this flow to develop a great research plan for your project:

Define your project’s purpose

Start by defining your project’s purpose. Identify what your project aims to accomplish and what you are researching. Remember to use clear language.

Thinking about the project’s purpose will help you set realistic goals and inform how you divide tasks and assign responsibilities. These individual tasks will be your stepping stones to reach your overarching goal.

Additionally, you’ll want to identify the specific problem, the usability metrics needed, and the intended solutions.

Know the following three things about your project’s purpose before you outline anything else:

What you’re doing

Why you’re doing it

What you expect from it

Identify individual objectives

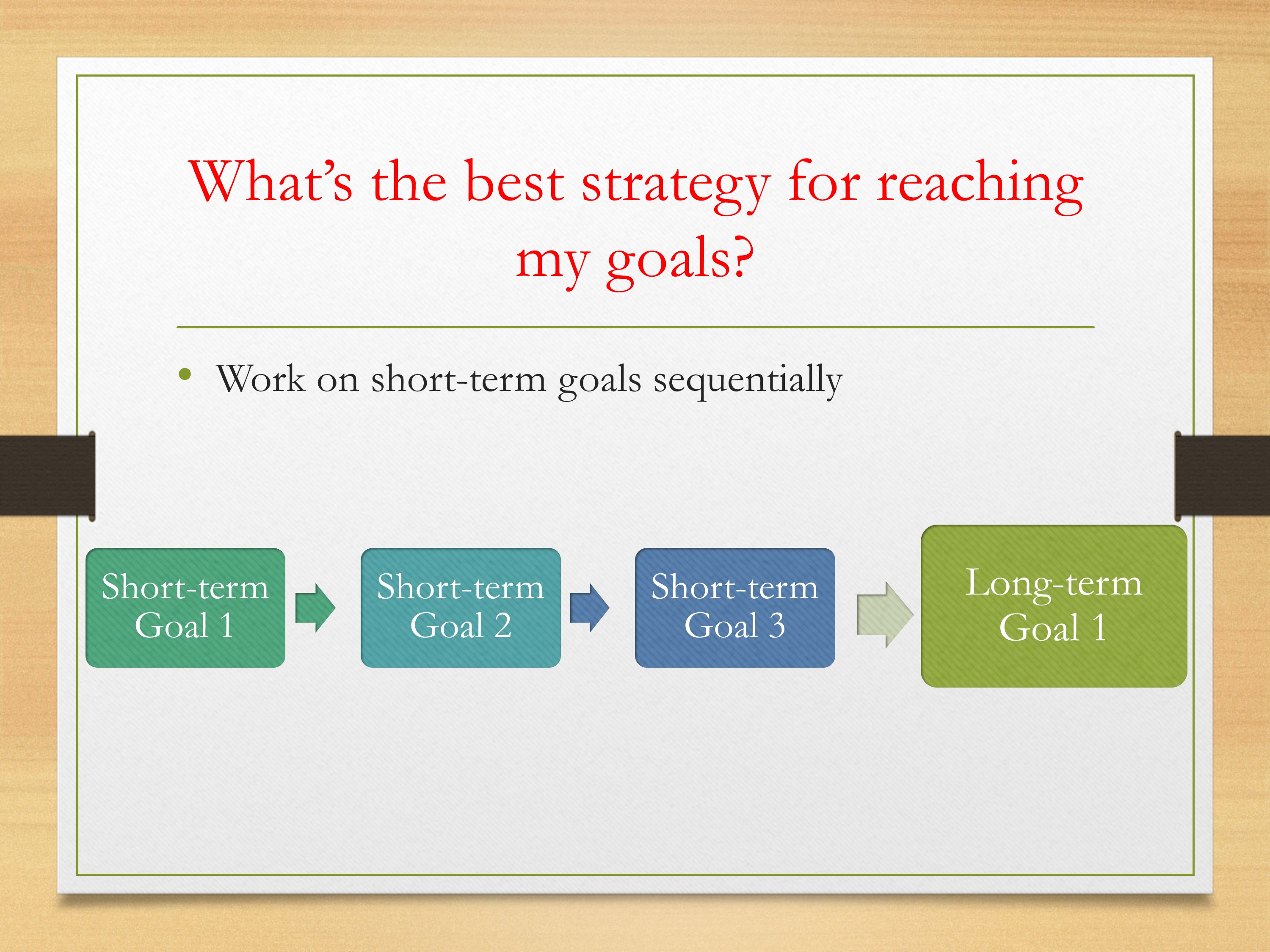

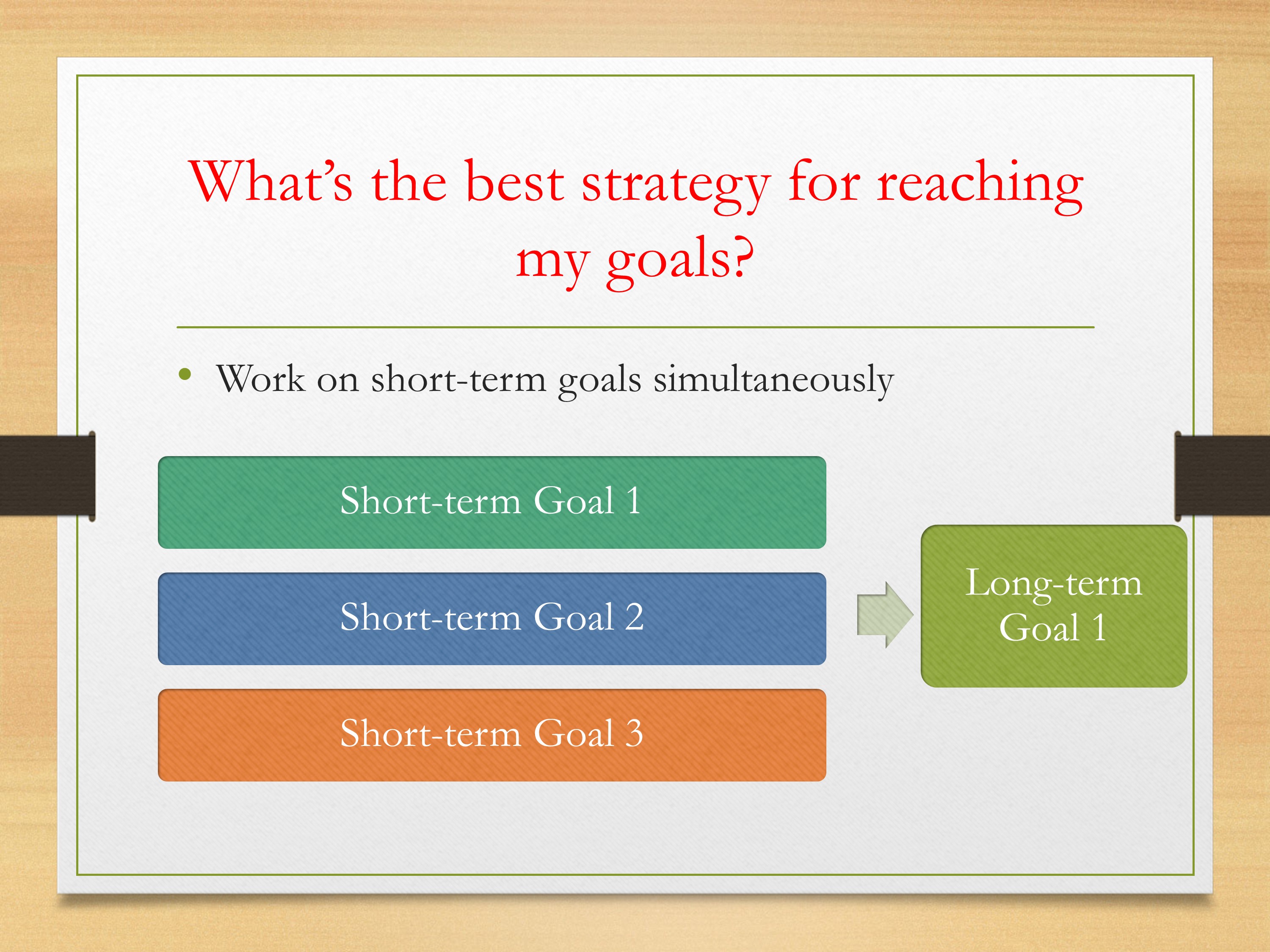

With your overarching project objectives in place, you can identify any individual goals or steps needed to reach those objectives. Break them down into phases or steps. You can work backward from the project goal and identify every process required to facilitate it.

Be mindful to identify each unique task so that you can assign responsibilities to various team members. At this point in your research plan development, you’ll also want to assign priority to those smaller, more manageable steps and phases that require more immediate or dedicated attention.

Select research methods

Once you have outlined your goals, objectives, steps, and tasks, it’s time to drill down on selecting research methods . You’ll want to leverage specific research strategies and processes. When you know what methods will help you reach your goals, you and your teams will have direction to perform and execute your assigned tasks.

Research methods might include any of the following:

User interviews : this is a qualitative research method where researchers engage with participants in one-on-one or group conversations. The aim is to gather insights into their experiences, preferences, and opinions to uncover patterns, trends, and data.

Field studies : this approach allows for a contextual understanding of behaviors, interactions, and processes in real-world settings. It involves the researcher immersing themselves in the field, conducting observations, interviews, or experiments to gather in-depth insights.

Card sorting : participants categorize information by sorting content cards into groups based on their perceived similarities. You might use this process to gain insights into participants’ mental models and preferences when navigating or organizing information on websites, apps, or other systems.

Focus groups : use organized discussions among select groups of participants to provide relevant views and experiences about a particular topic.

Diary studies : ask participants to record their experiences, thoughts, and activities in a diary over a specified period. This method provides a deeper understanding of user experiences, uncovers patterns, and identifies areas for improvement.

Five-second testing: participants are shown a design, such as a web page or interface, for just five seconds. They then answer questions about their initial impressions and recall, allowing you to evaluate the design’s effectiveness.

Surveys : get feedback from participant groups with structured surveys. You can use online forms, telephone interviews, or paper questionnaires to reveal trends, patterns, and correlations.

Tree testing : tree testing involves researching web assets through the lens of findability and navigability. Participants are given a textual representation of the site’s hierarchy (the “tree”) and asked to locate specific information or complete tasks by selecting paths.

Usability testing : ask participants to interact with a product, website, or application to evaluate its ease of use. This method enables you to uncover areas for improvement in digital key feature functionality by observing participants using the product.

Live website testing: research and collect analytics that outlines the design, usability, and performance efficiencies of a website in real time.

There are no limits to the number of research methods you could use within your project. Just make sure your research methods help you determine the following:

What do you plan to do with the research findings?

What decisions will this research inform? How can your stakeholders leverage the research data and results?

Recruit participants and allocate tasks

Next, identify the participants needed to complete the research and the resources required to complete the tasks. Different people will be proficient at different tasks, and having a task allocation plan will allow everything to run smoothly.

Prepare a thorough project summary

Every well-designed research plan will feature a project summary. This official summary will guide your research alongside its communications or messaging. You’ll use the summary while recruiting participants and during stakeholder meetings. It can also be useful when conducting field studies.

Ensure this summary includes all the elements of your research project . Separate the steps into an easily explainable piece of text that includes the following:

An introduction: the message you’ll deliver to participants about the interview, pre-planned questioning, and testing tasks.

Interview questions: prepare questions you intend to ask participants as part of your research study, guiding the sessions from start to finish.

An exit message: draft messaging your teams will use to conclude testing or survey sessions. These should include the next steps and express gratitude for the participant’s time.

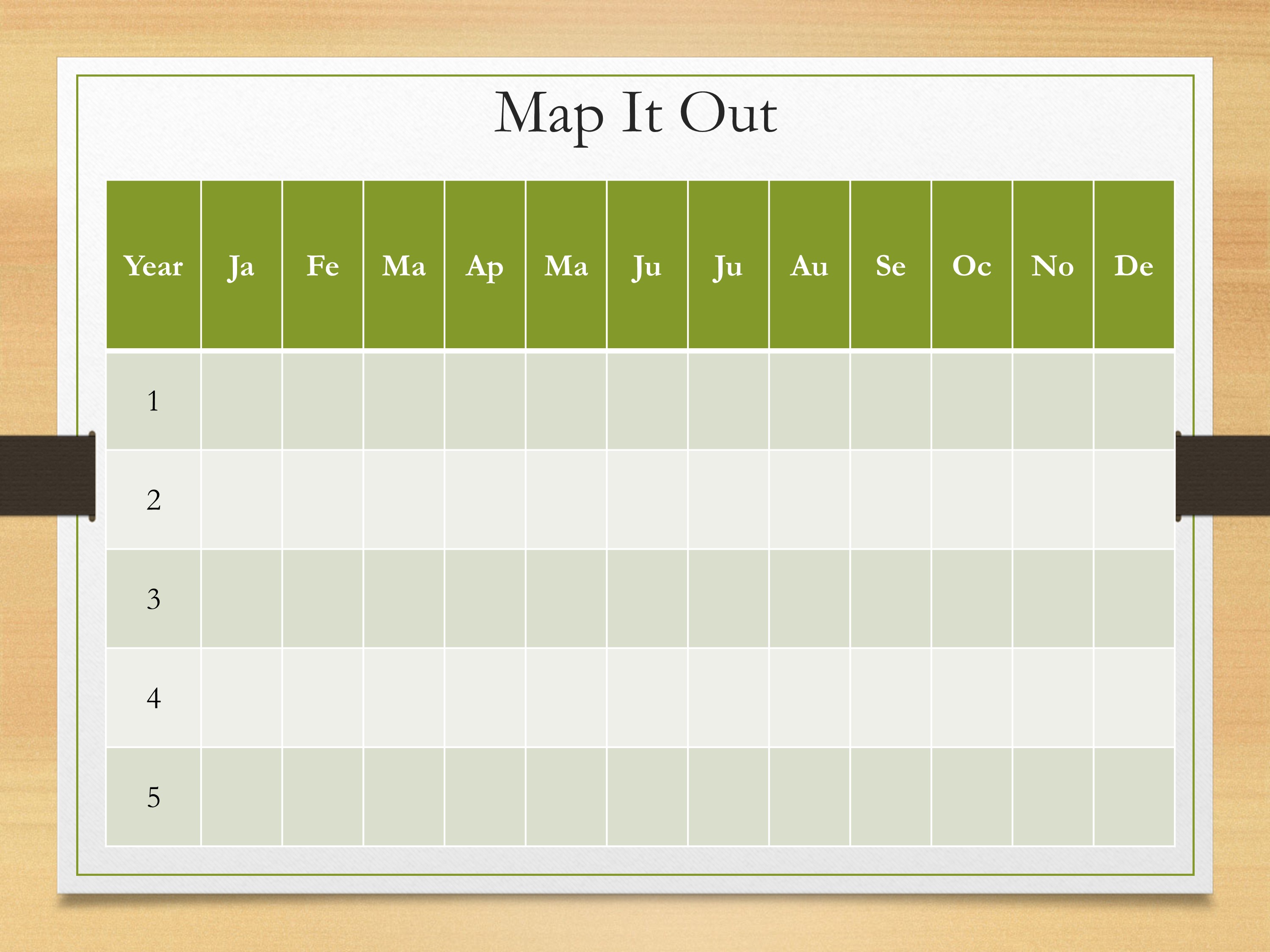

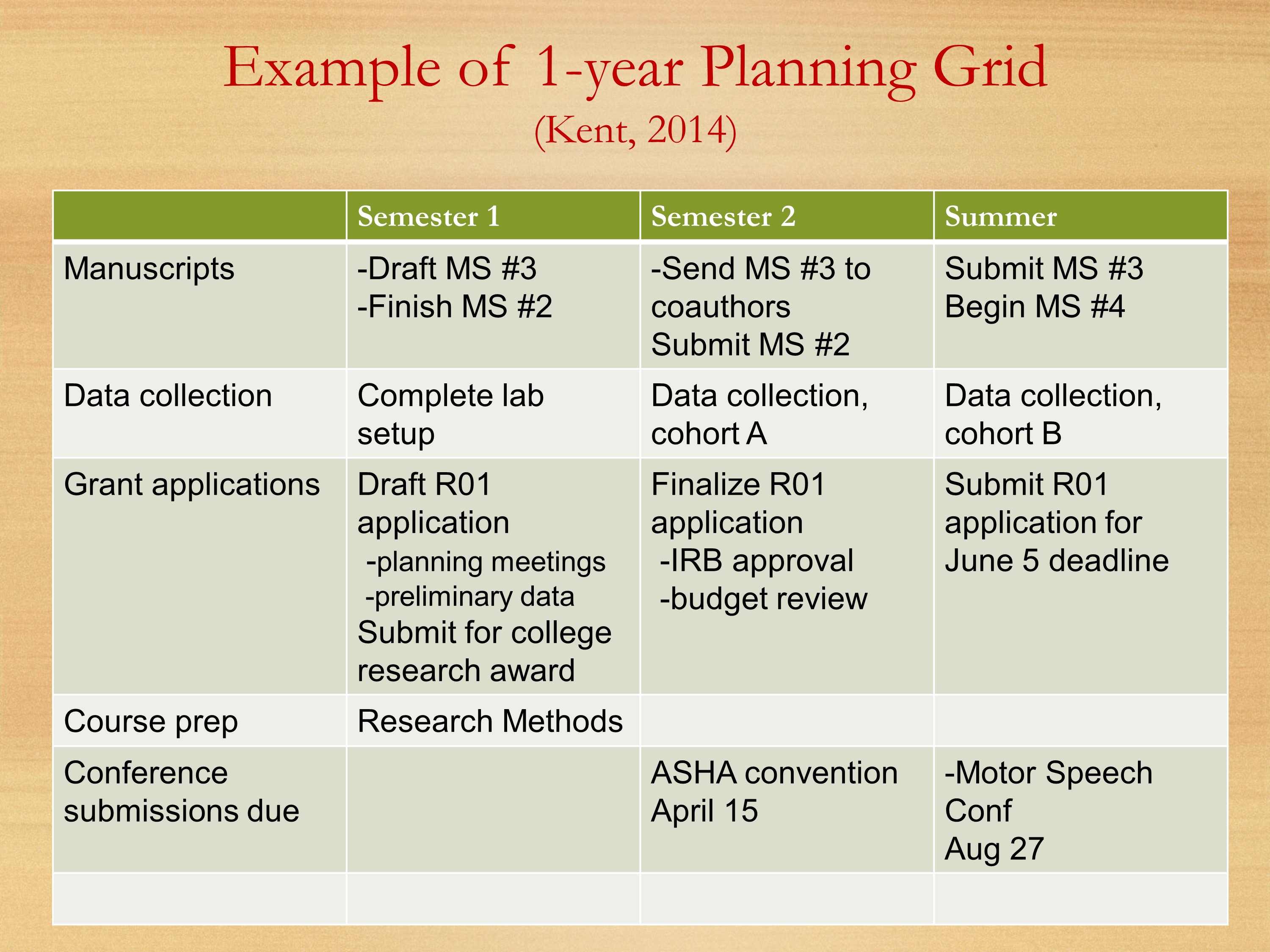

Create a realistic timeline

While your project might already have a deadline or a results timeline in place, you’ll need to consider the time needed to execute it effectively.

Realistically outline the time needed to properly execute each supporting phase of research and implementation. And, as you evaluate the necessary schedules, be sure to include additional time for achieving each milestone in case any changes or unexpected delays arise.

For this part of your research plan, you might find it helpful to create visuals to ensure your research team and stakeholders fully understand the information.

Determine how to present your results

A research plan must also describe how you intend to present your results. Depending on the nature of your project and its goals, you might dedicate one team member (the PI) or assume responsibility for communicating the findings yourself.

In this part of the research plan, you’ll articulate how you’ll share the results. Detail any materials you’ll use, such as:

Presentations and slides

A project report booklet

A project findings pamphlet

Documents with key takeaways and statistics

Graphic visuals to support your findings

- Format your research plan

As you create your research plan, you can enjoy a little creative freedom. A plan can assume many forms, so format it how you see fit. Determine the best layout based on your specific project, intended communications, and the preferences of your teams and stakeholders.

Find format inspiration among the following layouts:

Written outlines

Narrative storytelling

Visual mapping

Graphic timelines

Remember, the research plan format you choose will be subject to change and adaptation as your research and findings unfold. However, your final format should ideally outline questions, problems, opportunities, and expectations.

- Research plan example

Imagine you’ve been tasked with finding out how to get more customers to order takeout from an online food delivery platform. The goal is to improve satisfaction and retain existing customers. You set out to discover why more people aren’t ordering and what it is they do want to order or experience.

You identify the need for a research project that helps you understand what drives customer loyalty . But before you jump in and start calling past customers, you need to develop a research plan—the roadmap that provides focus, clarity, and realistic details to the project.

Here’s an example outline of a research plan you might put together:

Project title

Project members involved in the research plan

Purpose of the project (provide a summary of the research plan’s intent)

Objective 1 (provide a short description for each objective)

Objective 2

Objective 3

Proposed timeline

Audience (detail the group you want to research, such as customers or non-customers)

Budget (how much you think it might cost to do the research)

Risk factors/contingencies (any potential risk factors that may impact the project’s success)

Remember, your research plan doesn’t have to reinvent the wheel—it just needs to fit your project’s unique needs and aims.

Customizing a research plan template

Some companies offer research plan templates to help get you started. However, it may make more sense to develop your own customized plan template. Be sure to include the core elements of a great research plan with your template layout, including the following:

Introductions to participants and stakeholders

Background problems and needs statement

Significance, ethics, and purpose

Research methods, questions, and designs

Preliminary beliefs and expectations

Implications and intended outcomes

Realistic timelines for each phase

Conclusion and presentations

How many pages should a research plan be?

Generally, a research plan can vary in length between 500 to 1,500 words. This is roughly three pages of content. More substantial projects will be 2,000 to 3,500 words, taking up four to seven pages of planning documents.

What is the difference between a research plan and a research proposal?

A research plan is a roadmap to success for research teams. A research proposal, on the other hand, is a dissertation aimed at convincing or earning the support of others. Both are relevant in creating a guide to follow to complete a project goal.

What are the seven steps to developing a research plan?

While each research project is different, it’s best to follow these seven general steps to create your research plan:

Defining the problem

Identifying goals

Choosing research methods

Recruiting participants

Preparing the brief or summary

Establishing task timelines

Defining how you will present the findings

Should you be using a customer insights hub?

Do you want to discover previous research faster?

Do you share your research findings with others?

Do you analyze research data?

Start for free today, add your research, and get to key insights faster

Editor’s picks

Last updated: 18 April 2023

Last updated: 27 February 2023

Last updated: 6 February 2023

Last updated: 5 February 2023

Last updated: 16 April 2023

Last updated: 9 March 2023

Last updated: 30 April 2024

Last updated: 12 December 2023

Last updated: 11 March 2024

Last updated: 4 July 2024

Last updated: 6 March 2024

Last updated: 5 March 2024

Last updated: 13 May 2024

Latest articles

Related topics, .css-je19u9{-webkit-align-items:flex-end;-webkit-box-align:flex-end;-ms-flex-align:flex-end;align-items:flex-end;display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-flex-direction:row;-ms-flex-direction:row;flex-direction:row;-webkit-box-flex-wrap:wrap;-webkit-flex-wrap:wrap;-ms-flex-wrap:wrap;flex-wrap:wrap;-webkit-box-pack:center;-ms-flex-pack:center;-webkit-justify-content:center;justify-content:center;row-gap:0;text-align:center;max-width:671px;}@media (max-width: 1079px){.css-je19u9{max-width:400px;}.css-je19u9>span{white-space:pre;}}@media (max-width: 799px){.css-je19u9{max-width:400px;}.css-je19u9>span{white-space:pre;}} decide what to .css-1kiodld{max-height:56px;display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;}@media (max-width: 1079px){.css-1kiodld{display:none;}} build next, decide what to build next, log in or sign up.

Get started for free

We use cookies to give you the best experience possible. By continuing we’ll assume you’re on board with our cookie policy

- A Research Guide

- Research Paper Guide

How to Write a Research Plan

- Research plan definition

- Purpose of a research plan

- Research plan structure

- Step-by-step writing guide

Tips for creating a research plan

- Research plan examples

Research plan: definition and significance

What is the purpose of a research plan.

- Bridging gaps in the existing knowledge related to their subject.

- Reinforcing established research about their subject.

- Introducing insights that contribute to subject understanding.

Research plan structure & template

Introduction.

- What is the existing knowledge about the subject?

- What gaps remain unanswered?

- How will your research enrich understanding, practice, and policy?

Literature review

Expected results.

- Express how your research can challenge established theories in your field.

- Highlight how your work lays the groundwork for future research endeavors.

- Emphasize how your work can potentially address real-world problems.

5 Steps to crafting an effective research plan

Step 1: define the project purpose, step 2: select the research method, step 3: manage the task and timeline, step 4: write a summary, step 5: plan the result presentation.

- Brainstorm Collaboratively: Initiate a collective brainstorming session with peers or experts. Outline the essential questions that warrant exploration and answers within your research.

- Prioritize and Feasibility: Evaluate the list of questions and prioritize those that are achievable and important. Focus on questions that can realistically be addressed.

- Define Key Terminology: Define technical terms pertinent to your research, fostering a shared understanding. Ensure that terms like “church” or “unreached people group” are well-defined to prevent ambiguity.

- Organize your approach: Once well-acquainted with your institution’s regulations, organize each aspect of your research by these guidelines. Allocate appropriate word counts for different sections and components of your research paper.

Research plan example

- Writing a Research Paper

- Research Paper Title

- Research Paper Sources

- Research Paper Problem Statement

- Research Paper Thesis Statement

- Hypothesis for a Research Paper

- Research Question

- Research Paper Outline

- Research Paper Summary

- Research Paper Prospectus

- Research Paper Proposal

- Research Paper Format

- Research Paper Styles

- AMA Style Research Paper

- MLA Style Research Paper

- Chicago Style Research Paper

- APA Style Research Paper

- Research Paper Structure

- Research Paper Cover Page

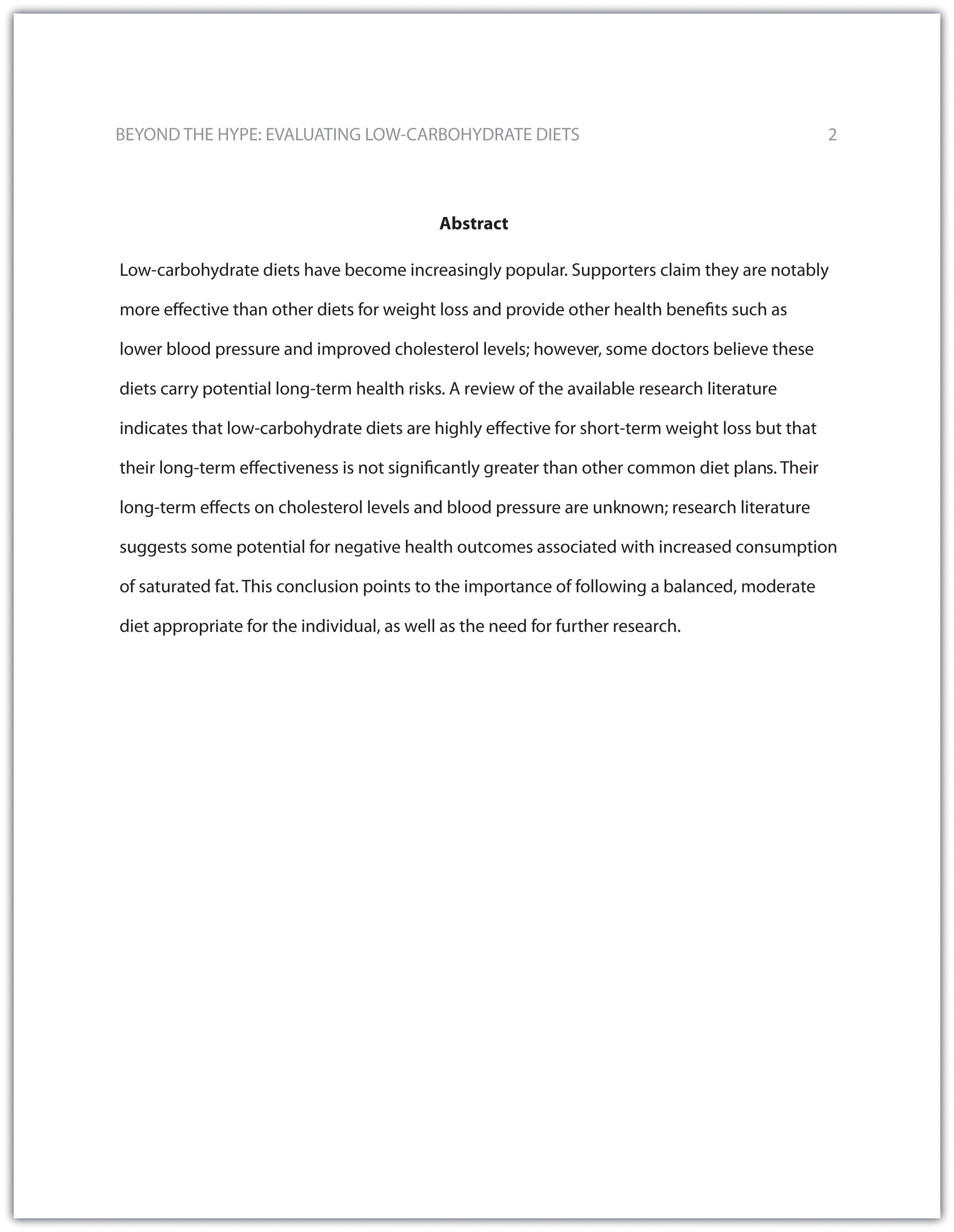

- Research Paper Abstract

- Research Paper Introduction

- Research Paper Body Paragraph

- Research Paper Literature Review

- Research Paper Background

- Research Paper Methods Section

- Research Paper Results Section

- Research Paper Discussion Section

- Research Paper Conclusion

- Research Paper Appendix

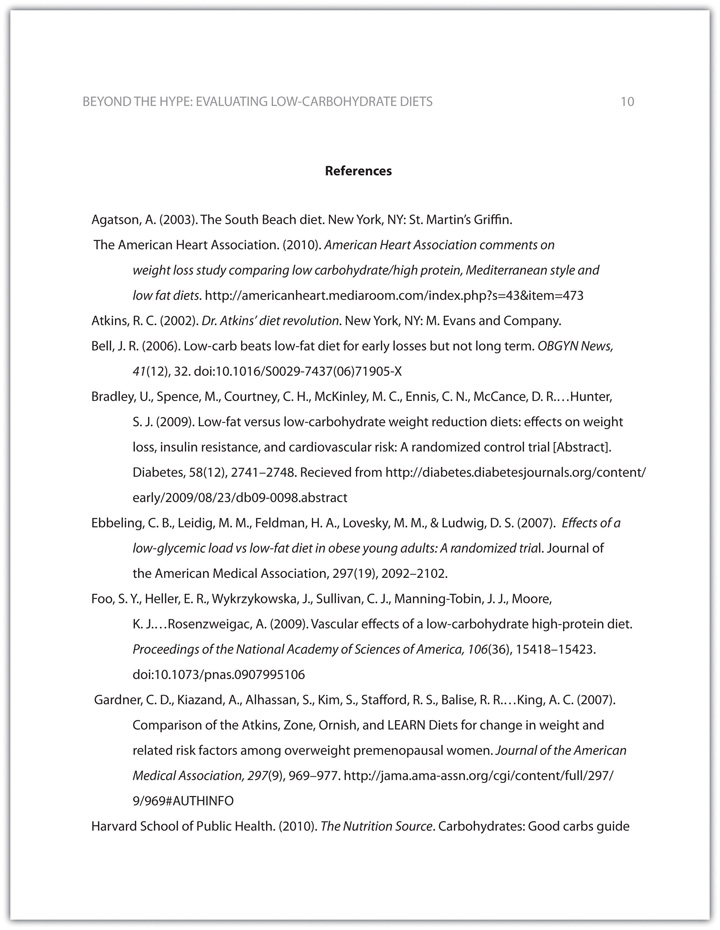

- Research Paper Bibliography

- APA Reference Page

- Annotated Bibliography

- Bibliography vs Works Cited vs References Page

- Research Paper Types

- What is Qualitative Research

Receive paper in 3 Hours!

- Choose the number of pages.

- Select your deadline.

- Complete your order.

Number of Pages

550 words (double spaced)

Deadline: 10 days left

By clicking "Log In", you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We'll occasionally send you account related and promo emails.

Sign Up for your FREE account

FLEET LIBRARY | Research Guides

Rhode island school of design, create a research plan: research plan.

- Research Plan

- Literature Review

- Ulrich's Global Serials Directory

- Related Guides

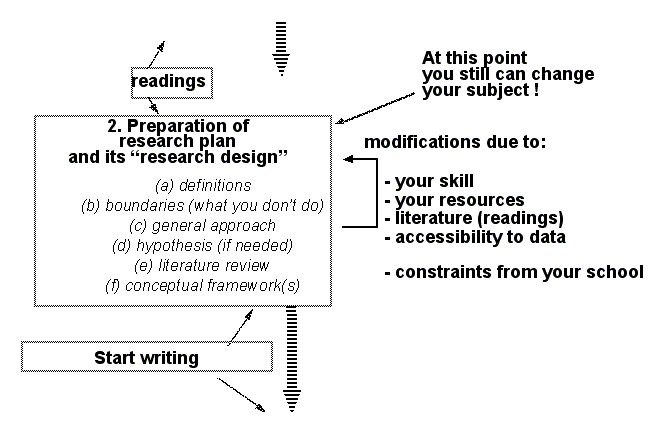

A research plan is a framework that shows how you intend to approach your topic. The plan can take many forms: a written outline, a narrative, a visual/concept map or timeline. It's a document that will change and develop as you conduct your research. Components of a research plan

1. Research conceptualization - introduces your research question

2. Research methodology - describes your approach to the research question

3. Literature review, critical evaluation and synthesis - systematic approach to locating,

reviewing and evaluating the work (text, exhibitions, critiques, etc) relating to your topic

4. Communication - geared toward an intended audience, shows evidence of your inquiry

Research conceptualization refers to the ability to identify specific research questions, problems or opportunities that are worthy of inquiry. Research conceptualization also includes the skills and discipline that go beyond the initial moment of conception, and which enable the researcher to formulate and develop an idea into something researchable ( Newbury 373).

Research methodology refers to the knowledge and skills required to select and apply appropriate methods to carry through the research project ( Newbury 374) .

Method describes a single mode of proceeding; methodology describes the overall process.

Method - a way of doing anything especially according to a defined and regular plan; a mode of procedure in any activity

Methodology - the study of the direction and implications of empirical research, or the sustainability of techniques employed in it; a method or body of methods used in a particular field of study or activity *Browse a list of research methodology books or this guide on Art & Design Research

Literature Review, critical evaluation & synthesis

A literature review is a systematic approach to locating, reviewing, and evaluating the published work and work in progress of scholars, researchers, and practitioners on a given topic.

Critical evaluation and synthesis is the ability to handle (or process) existing sources. It includes knowledge of the sources of literature and contextual research field within which the person is working ( Newbury 373).

Literature reviews are done for many reasons and situations. Here's a short list:

| to learn about a field of study to understand current knowledge on a subject to formulate questions & identify a research problem to focus the purpose of one's research to contribute new knowledge to a field personal knowledge intellectual curiosity | to prepare for architectural program writing academic degrees grant applications proposal writing academic research planning funding |

Sources to consult while conducting a literature review:

Online catalogs of local, regional, national, and special libraries

meta-catalogs such as worldcat , Art Discovery Group , europeana , world digital library or RIBA

subject-specific online article databases (such as the Avery Index, JSTOR, Project Muse)

digital institutional repositories such as Digital Commons @RISD ; see Registry of Open Access Repositories

Open Access Resources recommended by RISD Research LIbrarians

works cited in scholarly books and articles

print bibliographies

the internet-locate major nonprofit, research institutes, museum, university, and government websites

search google scholar to locate grey literature & referenced citations

trade and scholarly publishers

fellow scholars and peers

Communication

Communication refers to the ability to

- structure a coherent line of inquiry

- communicate your findings to your intended audience

- make skilled use of visual material to express ideas for presentations, writing, and the creation of exhibitions ( Newbury 374)

Research plan framework: Newbury, Darren. "Research Training in the Creative Arts and Design." The Routledge Companion to Research in the Arts . Ed. Michael Biggs and Henrik Karlsson. New York: Routledge, 2010. 368-87. Print.

About the author

Except where otherwise noted, this guide is subject to a Creative Commons Attribution license

source document

Routledge Companion to Research in the Arts

- Next: Literature Review >>

- Last Updated: Sep 20, 2023 5:05 PM

- URL: https://risd.libguides.com/researchplan

career support

support to get a great job

- Career Development

How to Write an Effective Research Plan: The Ultimate Guide

Some logistical headaches are inevitable. Many can be relieved with a well-structured, well-written, research plan. Heres a go-to reference for crafting one effectively. Words by Nikki Anderson-Stanier, Visuals by Alisa Harvey

When we think about what we love about our work—what excites us, what inspires us, what triggers the next big “a-ha” moment—we rarely think about processes or documentation.

But when we think about what frustrates us about our work—”next steps” that get delayed, projects that feel unfocused, little logistics that hold up our plans—we often blame processes and documentation.

Even if you don’t consistently reference a research plan, it can help ensure your next project goes more smoothly.

This walk-through will teach you how to write a plan in 15 minutes that’ll save you hours of work down the road.

Get our time-saving research plan templates (with a sample plan, and handy walkthrough) for free here.

What do you mean by user research plan? And why do I need one? A user research plan is a concise reference point for your project’s timeline, goals, main players, and objectives. It’s not always used extensively after the project has started. But sometimes youll use it to remind stakeholders of a project’s purpose, or explain certain logistical decisions (like why certain types of participants were recruited).

Overall, research plans offer an overview about the initiative taking place and serve as a kick-off document for a project. Their beauty lies in their capacity to keep your team on track, to ensure overarching goals are well-defined and agreed upon, and to guarantee those goals are met by the research.

Research plans keep the entire team focused on an outcome and provide an easy reference to keep “need-to-know” stakeholders in the know. They prevent everyone from getting bogged down in the details and from switching the goal of the research in the middle by mistake.

Most importantly, they allow researchers—or whoever is doing the research—to ensure the objectives of the research plan will be answered in the most effective and efficient way possible by the end of the project. We want to make sure we are actually answering the questions we set out to uncover, and research plans enable us to do so.

Imagine you’re working as a researcher at an online food ordering service that allows you to order takeaway delivered to your door from restaurants in your area.

One day, a project lands on your desk. A product manager wants to know how to get people to order takeaway more frequently.

After some back and forth, you get a handle on what the product team is hoping to learn. Their goal is to increase retention rates and user satisfaction. They want to know: Why do customers not order more frequently? And how do customers decide what they want to order?

The team wants to have a better overall understanding of the drivers for customer loyalty, and the pain points that prevent customers from becoming loyal to the platform.

With the project in hand, you’re ready to sit down and write a plan. Then you can share the first draft with the product team to ensure you’re interpreting their aims correctly.

The background section is pretty straightforward. It consists of a few sentences on what the research is about and why it is happening, which orients people to needs and expectations. The background also includes a problem statement (the central question you’re trying to answer with the research findings).

We want to understand the reasons behind why certain customers are reordering at a higher frequency, as well as the barriers encountered by customers that prevent them from reordering on the platform (problem statement).

We will be using generative research techniques to explore the journey users take—both inside and outside of our platform, when they decide to order takeaway—in order to better understand the challenges and needs they face in these circumstances.

Objectives are one of the hardest parts of the research plan to write. They’re the specific ideas you want to learn more about during the research and the questions you want to be answered. Essentially, the objectives drive the entire project. So, how do you write them effectively?

First, start with the central problem statement: to understand the reasons behind why certain customers are reordering at a higher frequency, as well as the barriers encountered by customers that prevent them from reordering on the platform.

Our research objectives should address what we want to learn and how we are going to study the problem statement.

A well-crafted research plan is essential for guiding your research project towards success. Whether conducting academic studies or market research for business, having a thoughtful plan sets you up to generate meaningful insights and conclusions

This step-by-step guide will teach you how to write a clear, actionable research plan to keep your project on track.

Define the Core Research Problem

Start by clearly defining the fundamental problem your research aims to address Concisely explain

- What gap in understanding or need for knowledge exists?

- Who is affected by this problem?

- Why is it important to address?

For example, a research problem could be: “Childhood obesity has tripled over the past 30 years. This epidemic needs to be better understood so preventative health programs can be improved.”

Articulating the research problem provides focus and frames the significance of your study. It’s the catalyst for the entire endeavor.

Identify the Research Goals and Objectives

Once the research problem is established, specify your goals and objectives.

The goals are the overarching achievements you hope to accomplish. Common examples are:

- Discover new information about a topic

- Prove or disprove a hypothesis

- Develop solutions to an existing problem

Objectives are the specific aims you will complete to reach the larger goals. For instance:

- Conduct surveys gathering input from 500 patients

- Interview 25 doctors working in related healthcare fields

- Analyze trends in childhood obesity rates across 10 years of CDC data

Well-defined goals and objectives keep the project sharply focused on outcomes that address the research problem. They also establish clear milestones for measuring progress.

Choose the Research Methods

Your objectives point to the specific research methods you’ll use to conduct the study. Outline the techniques you’ll leverage to gather and analyze data.

Common qualitative methods include:

- One-on-one interviews asking open-ended questions

- Focus groups for group discussions

- Observation gathering descriptive field notes

- Case studies examining individuals or events in-depth

Quantitative methods often entail:

- Surveys with closed-ended questions

- Experiments manipulating variables under controlled conditions

- Systematic statistical analysis of numerical datasets

Choose methods that allow you to best answer your research questions with credible, relevant data. Be specific on tools and analytical approaches.

Recruit Research Participants

If your methods involve surveys, interviews, focus groups or other direct interactions with people, outline your participant recruitment plan.

- How many participants you aim to include

- Their key demographic qualifications (e.g. age, gender, location)

- How you will find and screen qualified participants

- Incentives you’ll provide in exchange for their time

Thoughtful recruiting is essential for getting enough participants with characteristics critical to your research goals. Take care to recruit ethically and avoid sampling bias.

Craft an Informative Research Summary

After defining the core elements above, draft a short summary clearly explaining:

- The research problem and goals

- Specific objectives

- Methods for collecting and analyzing data

- Participant recruitment plan

- Anticipated timeline

This high-level summary gives interested parties a quick understanding of the scope before they dive into the details. It’s a valuable part of your research proposal or application.

Build a Detailed Timeline

With goals identified, flesh out a realistic timeline for each phase. Typical steps include:

- Background reading – 2 weeks

- Research method design – 3 weeks

- Participant recruitment – 3 weeks

- Data collection – 5 weeks

- Data analysis – 4 weeks

- Conclusions, results and recommendations – 3 weeks

Schedule time for delays, revisions and unexpected roadblocks. Finishing late can decrease the value of your findings, so leave ample margins.

Tools like GANTT charts help visualize key milestones over the project timeline. Reviewing your timeline often keeps momentum going.

Plan Your Findings Report

It’s never too early to start planning how you’ll share eventual findings. Will you produce a detailed final paper? Present results at a conference? Write an executive summary for sponsors?

Define expected report elements such as:

- Statistical charts and graphs

- Highlights of major discoveries

- Recommendations based on conclusions

- Appendices with raw data or research artifacts

Consider your target audiences and tailor report formats to optimize value for each. How you share discoveries is part of the process.

Write Concisely to Showcase Expertise

Keep language clear, specific and concise throughout your research plan. Avoid excessive jargon that could confuse readers. Show you thoroughly understand the methodology at hand vs. relying on generic descriptions.

A well-written plan quickly establishes you as an expert. It instills confidence in your ability to conduct rigorous research that adds meaningful insights. Sloppy plans raise doubts.

Refine drafts until the plan encapsulates your research aims as succinctly as possible. Precision demonstrates you are ready to skillfully execute.

Emphasize Significance to Secure Support

Take every opportunity to emphasize why your research matters. Explain how it addresses important gaps or problems. Outline the practical applications of expected insights.

Funders won’t invest precious resources without believing useful knowledge will result. Help them visualize the positive impacts on organizations, communities or society at large.

Depending on the project scope, you may need to submit proposals to boards for formal approval. Convince them of merits through articulate planning.

Adjust Expectations as Needed

Research rarely goes exactly according to the initial plan. As work progresses, adjust timelines, methods and goals as needed while keeping the core aims intact.

For example, you may need to revise recruiting criteria to increase participation. Or new discoveries mid-project might lead to adding interviews for richer data.

View your plan as a guiding framework rather than unbreakable contract. Stay nimble and adaptable, but don’t lose sight of the end goalposts.

Maintain Momentum With Project Management

Throughout execution, diligently track progress against your plan. Tools like Asana, Trello and Excel help you:

- Manage timelines with reminders for upcoming milestones

- Update stakeholders on project status

- Prioritize next actions and mark items complete

- Identify any roadblocks or resource gaps

Think of your plan as a working document. Referring to it often drives momentum and keeps efforts aligned.

Celebrate Hitting Major Milestones

Research requires intense focus and persistence. But don’t forget to celebrate progress along the way.

Take time to recognize when you complete:

- Secondary objectives like finishing initial interviews

- Primary goals like collecting all survey data

- The final report compiling all insights

Acknowledging wins motivates you through slogs. Share updates with colleagues and sponsors to maintain engagement.

Careful planning sets you up to generate research that provides true value. Avoid underplanning and risk wasting significant time. Overplanning wastes energy better directed elsewhere.

Finding the right balance takes practice across projects. Use this guide to build rigorous plans that steer impactful research delivering meaningful results.

Interested in more articles like this?

Nikki Anderson-Stanier is the founder of User Research Academy and a qualitative researcher with 9 years in the field. She loves solving human problems and petting all the dogs.

Bad versus better objectives:

Here are some additional examples I have generated in order to exemplify good versus bad objectives.

Bad: Understand why participants order food.

Better: Understand the end-to-end journey of how and why participants choose to order food online.

Why: “Understand why participants order food” is still too broad. It feels more like a problem statement that you’d want to break down into further objectives. You haven’t set a direction or boundaries.

Bad: Find out how to get participants to order food online.

Better: Uncover participants’ thought processes and prior experiences behind ordering food online.

Why: Trying to learn how to make someone do something is a challenging perspective with which to go into research. How would we ask good questions to get that information?

We are more interested in seeing what their thought process is behind the process, and if/why they have done so in the past. That’s a better foundation to build from.

Bad: Find out why people use Postmates to order food.

Better: Discover the different tools participants use when deciding to order food, and how they feel about each tool

Why: This could be helpful if Postmates is a tool your users frequently use instead of your platform, and you’re setting out to do a competitive analysis.

However, in this case, we’re doing generative research—defined by the product team’s needs and the plan’s background statement.

So in this case, it’s more useful to rely on the research to uncover what kinds of other tools are used. Otherwise, you’re hyper-focused and might miss other opportunities to explore.

Now that we’ve defined our problem statements and objectives, it’s time to define the type of participants we’ll rely on to get the insights we need.

One of the most important elements to any project is talking to the right people. If you don’t have a set vision for who you want to recruit, approximate your user, and include that approximation in your plan.

This will help optimize recruiting efforts to ensure you have the best participants you need for your study. Here are a few ways to approach this:

Bring in internal stakeholders that may have a good idea of what the target user will look like (such as marketing, sales, and customer support). With these stakeholders you can create hypotheses about who your users are, which is a great starting point for who you should be talking to.

Recruit based on their audiences. You can even recruit people who use the competitors product and, during the interview, ask them how they would make it better.

This will get you the participants you need.

- Is there a particular behavior you are looking for (such as ordered takeout X# amount of times in the past three months)?

- Is it necessary they have used your product (or a competitor’s product)?

- Do they need to be a certain age or hold a certain professional title?

Make sure you include the right criteria in order to evaluate whether or not that person would be your target participant.

It’s often useful to attach your screener questions to this part of the plan.

Compared to the others, this step is fairly easy. In this section, talk briefly about the chosen methodology and the reasons behind why that particular method was chosen.

Example methodology

For this study, we’re using one-on-one generative research interviews. This method will enable us to dig deeper into understanding our customers, fostering a strong sense of empathy and enabling us to answer our objectives.

If you’ll be talking to your users in real time, an interview guide is a valuable cheat sheet. It reminds you of which questions will help you meet your objectives, and can keep your discussions on track.

If you’re doing longitudinal or unmoderated research—like unmoderated usability testing, or a diary study—your interview guide might include the exact prompts or triggers you’ll be sending your participants to complete.

Even if you don’t actively refer to your interview guide, writing one ensures everyone else on the team has a place to input their questions. And if you’re outlining questions or prompts for unmoderated research, making those questions public for reference gives your team a chance to alert you if something is unclear.

For moderated research, my interview guides consist of the following sections:

The introduction details what you will say to the participant before the session begins, and serves as a nice preview of all the different points you’ll be discussing. It’s especially helpful if you are nervous about going into a session.

Example introduction

Hi there, I’m Nikki, a user researcher at a takeaway delivery company. Thank you so much for talking with me today. I am really excited to have a conversation with you!

During this session, we are looking to better understand what makes you order food from our service. Imagine were filming a small documentary on you, and are really trying to understand all your thoughts. There are no right or wrong answers, so please just talk freely, and I promise we will find it fascinating.

This session should take about 60 minutes. If you feel uncomfortable at any time or need to stop/take a break, just let me know. Everything you say here today will be completely confidential.

Would it be okay if we recorded today’s session for internal notetaking purposes? Do you have any questions for me? Let’s get started!

This portion of the interview guide is the trickiest to write. In this section, we’re writing down some of the open-ended questions we want to ask users during the session.

For most types of qual research, you won’t always have a long list of detailed questions, since it’s more of a conversation than an interview. But readying a few open-ended questions you can then follow up on can serve as useful prep.

Pro tip: Questions to avoid in your interviews and interview guides

- Priming users – Forces the user to answer in a particular way

- Leading questions – May prohibit the user from exploring a different avenue

- Asking about future behavior – Instead of focusing on the past/present

- Double-barreled questions – Asking two questions in one sentence

- Yes/no questions – Ends the conversation. Instead, we focus on open-ended questions

Examples of priming/leading questions:

- Priming: “How much do you like being able to order takeaway online?”

- Leading: “Could you show me how you would reorder the same order by clicking on the button?”

I always outline my interview guide questions with the TEDW approach. TEDW stands for the following structures:

- “ T ell me…”

- “ E xplain….”

- “ D escribe….”

- “ W alk me through….”

Beyond that, one cool trick for question generation is to use your research objectives. Your questions should be able to give you insights that answer your objectives.

So when you ask a participant a question, it is ultimately answering one of the objectives. Turn each objective into 3–5 questions.

So, let’s take our central research problem and objectives and form some research questions.

Central research problem: To understand the reasons behind why certain customers are reordering at a higher frequency, as well as the barriers encountered by customers that prevent them from reordering on the platform.

- Discover users’ motivations behind reordering, both inside and outside of the website/app

- Uncover other websites/apps customers are using to order takeaway

- Learn about any pain points users are encountering during their process, and what improvements they might make

Research questions

Objective 1: Discover users’ motivations behind reordering, both inside and outside of the website/app

- Think about the last time you ordered takeaway on our website/app. Walk me through the entire process, starting with what sparked the idea.

- Explain how you made the decision to reorder food on our particular website/app.

- Who were you talking to?

- What time of day was it?

- How were you feeling?

- Did you have other websites/apps open?

Objective 2: Learn about any pain points users are encountering during their process, and what improvements they might make.

- How did you solve the problem?

- What would be the most ideal scenario for reordering takeaway from the website/app (crazy ideas included!)?

- How would you change or improve the process of reordering food outside of our website/app? Inside our website/app?

Objective 3: Uncover other websites/apps customers are using to order takeaway.

- Talk me through the other websites/apps you have used multiple to order takeaway (or even groceries).

- Describe your experience with these other websites/apps.

- What are the other websites/apps you use to help you make a decision about whether or not to order takeaway?

Each of these research questions is a jumping off point for a more open conversation. They get at the core of your objectives, which in turn gets to the core of the central problem you’re trying to solve.

The wrap-up is a reminder of all the items to mention during the end of an interview. Generally, you cover information such as compensation, asking if they would be interested in future research, and assuring them that you’re thankful for their time.

Example wrap up

Those are all the questions I have for you today. I really appreciate you taking the time. Your feedback was extremely helpful, and I am excited to share it with the team to see how we can improve.

Since your feedback was so useful, would you be willing to participate in another research session in the future? You have my direct email, so if you have any problems with the compensation or any questions or feedback in the future, please feel free to email me at any time.

Do you have any other questions for me? Again, thank you so much for your time and I hope you enjoy the rest of your day!

I place an approximate timeline in my research plans, so people know what to expect for start and end dates.

Some researchers stay away from this timeline, as it can solidify a deadline that may prove more difficult to meet than expected. I always stress that it is a basic approximation.

Example timeline

- Research start date: Monday, August 5th

- Research plan creation and review: Wednesday, August 7th

- Recruitment begins: Thursday, August 8th

- Interviewing begins: Thursday, August 15th

- Interviewing ends: Friday, August 23rd

- Synthesis begins: Monday, August 26th

- Synthesis ends: Wednesday, August 28th

- Report presentation: Friday, August 30th

In this section, I make sure it’s easy for everyone to find:

- Links to the research sessions

- Any synthesis documents

- The presentation

- Any development/design tickets, prototypes or concepts

- Any follow-up information which would give context to the study

Your user research plan is your research project in miniature. It’s the simplest way to align expectations, solicit feedback, and generate enthusiasm and support for your study.

Whether it actively guides your interviews, or just provides an active structure for organizing your thoughts, a solid research plan can go a long way towards guaranteeing a solid research project.

How to Write a Successful Research Proposal | Scribbr

What is a research plan?

A research plan is a documented overview of a project in its entirety, from end to end. It details the research efforts, participants, and methods needed, along with any anticipated results. It also outlines the project’s goals and mission, creating layers of steps to achieve those goals within a specified timeline.

How do I create a research plan for my project?

The first step to creating a research plan for your project is to define why and what you’re researching. Regardless of whether you’re working with a team or alone, understanding the project’s purpose can help you better define project goals.

How to write a research proposal?

A research proposal adheres to a clear and logical structure that ensures your project’s effectiveness. In the research plan structure, consider organizing its core components as in the following outline. Often referred to as the ‘need for study’ or ‘abstract,’ the introduction serves as the initial platform for your idea.

What makes a good research plan?

There’s general research planning; then there’s an official, well-executed research plan. Whatever data-driven research project you’re gearing up for, the research plan will be your framework for execution. The plan should also be detailed and thorough, with a diligent set of criteria to formulate your research efforts.

Related posts:

- What Is Treasury Management? (With Definition and Benefits)

- RASCI: What It Is and How To Use It for Project Management

- Interview Question: “What’s the Most Difficult Decision You’ve Had to Make?”

- Blog : Is there a dress code for the modern paralegal?

Related Posts

How to calculate percentile rank step-by-step, i want to be a lawyer: a step-by-step guide to becoming an attorney, leave a reply cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Research Guides

- Begin Your Research

- Outline and Plan

Begin Your Research: Outline and Plan

- Research Process

- Background Info

- Research Questions

Outlining and Planning Ahead: Confining or Comforting?

Creating a plan and outline before starting your research paper can lead to a more successful and satisfying writing process. Contrary to concerns about stifling creativity, planning ahead actually frees your mind from cluttered thoughts and allows for creativity to flourish within the boundaries of your rough plan. Just like various aspects of the natural and man-made world, successful creations often begin with some form of structure or boundary. Outlines serve as recipes for your paper, while research plans function as shopping lists, helping you organize your ideas and check your progress once you've completed your work.

Why Create an Outline?

According to the Purdue OWL's Writing Process guide , using an outline is helpful when wanting to "show the hierarchical relationship or logical ordering of information. For research papers, an outline may help you keep track of large amounts of information." Outlines even help those that are preparing a speech or presentation to deliver in front of an audience. Therefore, an outline has many benefits in aiding your writing, organizing your thoughts, keeping your material in logical structures, and giving your writing a boundary within which to keep focus. Making any kind of outline, no matter how rough or polished, will benefit you.

What is an Outline?

An outline is a structured document that lists the main parts of your research paper, essay, presentation, or report. It provides a roadmap for your planned writing, utilizing numbered lists to indicate the larger and nested structures.

- You can further divide your subtopics as needed using Arabic numerals, but there should always be more than one.

- Further subdivision

- Subtopic of First Part (more specific in relationship to the First Part heading)

- Subtopic of First Part (more specific in relationship to the heading above)

- Subtopic of First Part (there should always be more than one subtopic of each main part)

Unless required to use a certain outline template, you have the freedom to choose the type of outline that suits you best, whether it is rough or structured with full sentences, phrases, and alphanumeric ordered lists. Any kind of outline can be effective in aiding your writing process. In conclusion, outlining is a valuable tool for successful writing, allowing you to organize your thoughts and achieve your goals efficiently. By creating a clear plan, you can enhance your creativity and produce a more cohesive and well-structured piece of work.

Please open Purdue OWL's Writing Process guide or separate PDF which provides examples of full sentence and alphanumeric outlines.

- Research Outline Template (RTF file)

- Research Outline Template (PDF File)

Creating a Research Plan

Your final step in the beginning stages of your research journey is making a plan for the rest of your research and writing steps. Treat it like a schedule or shopping list, utilizing a short to-do list or a detailed schedule. Remember, this plan you devise is not restrictive; it's a guide to set achievable goals within one overall process. Here's what to include:

What should you include in a research plan?

As stated above, you don't need to fill out an entire research plan right now, *but as you learn more throughout this "How to Research" guide series. The following items are recommended items to put in your research plan:

- The research topic you have chosen and explored

- The research question or thesis statement you have drafted

- Any important assignment due dates, especially if you have to turn anything in at different stages (topic selection, annotated bibliography, rough draft, final draft)

- The kind of information you are interested in including (supporting or contrasting perspectives, definitions, analysis, facts, background, or statistics)*

- The search terms you have brainstormed and planned in the form of keywords, phrases, or search strings*

- The places you will go to look for information (library searchable databases, websites, physical libraries)*

- If there are any limitations or prohibited sources (no website or encyclopedias, for example)

You can use the provided templates to create your research plan as you progress through the "How to Research" guide series.

- Research Plan Template (RTF File)

- Research Plan Template (PDF File)

Congratulations on completing the initial steps of your research journey, and now you're ready to explore different types of information and sources.

- Learn the Types of Research Sources

- Find Research Sources

Image Source

Unless otherwise indicated, all images are courtesy of Adobe Stock. Paul J. Meyer quote image made in Canva, courtesy of Kristen Cook. The Research Outline Template was adapted from EasyBib.com.

- << Previous: Research Questions

- Next: Need Help? >>

- Last Updated: Jul 9, 2024 11:24 AM

- URL: https://mclennan.libguides.com/Begin

© McLennan Community College

1400 College Drive Waco, Texas 76708, USA

+1 (254) 299-8622

Write Your Research Plan

In this part, we give you detailed information about writing an effective Research Plan. We start with the importance and parameters of significance and innovation.

We then discuss how to focus the Research Plan, relying on the iterative process described in the Iterative Approach to Application Planning Checklist shown at Draft Specific Aims and give you advice for filling out the forms.

You'll also learn the importance of having a well-organized, visually appealing application that avoids common missteps and the importance of preparing your just-in-time information early.

While this document is geared toward the basic research project grant, the R01, much of it is useful for other grant types.

Table of Contents

Research plan overview and your approach, craft a title, explain your aims, research strategy instructions, advice for a successful research strategy, graphics and video, significance, innovation, and approach, tracking for your budget, preliminary studies or progress report, referencing publications, review and finalize your research plan, abstract and narrative.

Your application's Research Plan has two sections:

- Specific Aims —a one-page statement of your objectives for the project.

- Research Strategy —a description of the rationale for your research and your experiments in 12 pages for an R01.

In your Specific Aims, you note the significance and innovation of your research; then list your two to three concrete objectives, your aims.

Your Research Strategy is the nuts and bolts of your application, where you describe your research rationale and the experiments you will conduct to accomplish each aim. Though how you organize it is largely up to you, NIH expects you to follow these guidelines.

- Organize using bold headers or an outline or numbering system—or both—that you use consistently throughout.

- Start each section with the appropriate header: Significance, Innovation, or Approach.

- Organize the Approach section around your Specific Aims.

Format of Your Research Plan

To write the Research Plan, you don't need the application forms. Write the text in your word processor, turn it into a PDF file, and upload it into the application form when it's final.

Because NIH may return your application if it doesn't meet all requirements, be sure to follow the rules for font, page limits, and more. Read the instructions at NIH’s Format Attachments .

For an R01, the Research Strategy can be up to 12 pages, plus one page for Specific Aims. Don't pad other sections with information that belongs in the Research Plan. NIH is on the lookout and may return your application to you if you try to evade page limits.

Follow Examples

As you read this page, look at our Sample Applications and More to see some of the different strategies successful PIs use to create an outstanding Research Plan.

Keeping It All In Sync

Writing in a logical sequence will save you time.

Information you put in the Research Plan affects just about every other application part. You'll need to keep everything in sync as your plans evolve during the writing phase.

It's best to consider your writing as an iterative process. As you develop and finalize your experiments, you will go back and check other parts of the application to make sure everything is in sync: the "who, what, when, where, and how (much money)" as well as look again at the scope of your plans.

In that vein, writing in a logical sequence is a good approach that will save you time. We suggest proceeding in the following order:

- Create a provisional title.

- Write a draft of your Specific Aims.

- Start with your Significance and Innovation sections.

- Then draft the Approach section considering the personnel and skills you'll need for each step.

- Evaluate your Specific Aims and methods in light of your expected budget (for a new PI, it should be modest, probably under the $250,000 for NIH's modular budget).

- As you design experiments, reevaluate your hypothesis, aims, and title to make sure they still reflect your plans.

- Prepare your Abstract (a summary of your Specific Aims).

- Complete the other forms.

Even the smaller sections of your application need to be well-organized and readable so reviewers can readily grasp the information. If writing is not your forte, get help.

To view writing strategies for successful applications, see our Sample Applications and More . There are many ways to create a great application, so explore your options.

Within the character limit, include the important information to distinguish your project within the research area, your project's goals, and the research problem.

Giving your project a title at the outset can help you stay focused and avoid a meandering Research Plan. So you may want to launch your writing by creating a well-defined title.

NIH gives you a 200 character limit, but don’t feel obliged to use all of that allotment. Instead, we advise you to keep the title as succinct as possible while including the important information to distinguish your project within the research area. Make your title reflect your project's goals, the problem your project addresses, and possibly your approach to studying it. Make your title specific: saying you are studying lymphocyte trafficking is not informative enough.

For examples of strong titles, see our Sample Applications and More .

After you write a preliminary title, check that

- My title is specific, indicating at least the research area and the goals of my project.

- It is 200 characters or less.

- I use as simple language as possible.

- I state the research problem and, possibly, my approach to studying it.

- I use a different title for each of my applications. (Note: there are exceptions, for example, for a renewal—see Apply for Renewal for details.)

- My title has appropriate keywords.

Later you may want to change your initial title. That's fine—at this point, it's just an aid to keep your plans focused.

Since all your reviewers read your Specific Aims, you want to excite them about your project.

If testing your hypothesis is the destination for your research, your Research Plan is the map that takes you there.

You'll start by writing the smaller part, the Specific Aims. Think of the one-page Specific Aims as a capsule of your Research Plan. Since all your reviewers read your Specific Aims, you want to excite them about your project.

For more on crafting your Specific Aims, see Draft Specific Aims .

Write a Narrative

Use at least half the page to provide the rationale and significance of your planned research. A good way to start is with a sentence that states your project's goals.

For the rest of the narrative, you will describe the significance of your research, and give your rationale for choosing the project. In some cases, you may want to explain why you did not take an alternative route.

Then, briefly describe your aims, and show how they build on your preliminary studies and your previous research. State your hypothesis.

If it is likely your application will be reviewed by a study section with broad expertise, summarize the status of research in your field and explain how your project fits in.

In the narrative part of the Specific Aims of many outstanding applications, people also used their aims to

- State the technologies they plan to use.

- Note their expertise to do a specific task or that of collaborators.

- Describe past accomplishments related to the project.

- Describe preliminary studies and new and highly relevant findings in the field.

- Explain their area's biology.

- Show how the aims relate to one another.

- Describe expected outcomes for each aim.

- Explain how they plan to interpret data from the aim’s efforts.

- Describe how to address potential pitfalls with contingency plans.

Depending on your situation, decide which items are important for you. For example, a new investigator would likely want to highlight preliminary data and qualifications to do the work.

Many people use bold or italics to emphasize items they want to bring to the reviewers' attention, such as the hypothesis or rationale.

Detail Your Aims

After the narrative, enter your aims as bold bullets, or stand-alone or run-on headers.

- State your plans using strong verbs like identify, define, quantify, establish, determine.

- Describe each aim in one to three sentences.

- Consider adding bullets under each aim to refine your objectives.

How focused should your aims be? Look at the example below.

Spot the Sample

Read the Specific Aims of the Application from Drs. Li and Samulski , "Enhance AAV Liver Transduction with Capsid Immune Evasion."

- Aim 1. Study the effect of adeno-associated virus (AAV) empty particles on AAV capsid antigen cross-presentation in vivo .

- Aim 2. Investigate AAV capsid antigen presentation following administration of AAV mutants and/or proteasome inhibitors for enhanced liver transduction in vivo .

- Aim 3. Isolate AAV chimeric capsids with human hepatocyte tropism and the capacity for cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTL) evasion.

After finishing the draft Specific Aims, check that

- I keep to the one-page limit.

- Each of my two or three aims is a narrowly focused, concrete objective I can achieve during the grant.

- They give a clear picture of how my project can generate knowledge that may improve human health.

- They show my project's importance to science, how it addresses a critical research opportunity that can move my field forward.

- My text states how my work is innovative.

- I describe the biology to the extent needed for my reviewers.

- I give a rationale for choosing the topic and approach.

- I tie the project to my preliminary data and other new findings in the field.

- I explicitly state my hypothesis and why testing it is important.

- My aims can test my hypothesis and are logical.

- I can design and lead the execution of two or three sets of experiments that will strive to accomplish each aim.

- As much as possible, I use language that an educated person without expertise can understand.

- My text has bullets, bolding, or headers so reviewers can easily spot my aims (and other key items).

For each element listed above, analyze your text and revise it until your Specific Aims hit all the key points you'd like to make.

After the list of aims, some people add a closing paragraph, emphasizing the significance of the work, their collaborators, or whatever else they want to focus reviewers' attention on.

Your Research Strategy is the bigger part of your application's Research Plan (the other part is the Specific Aims—discussed above.)

The Research Strategy is the nuts and bolts of your application, describing the rationale for your research and the experiments you will do to accomplish each aim. It is structured as follows:

- Significance

- You can either include this information as a subsection of Approach or integrate it into any or all of the three main sections.

- If you do the latter, be sure to mark the information clearly, for example, with a bold subhead.

- Possible other sections, for example, human subjects, vertebrate animals, select agents, and others (these do not count toward the page limit).

Though how you organize your application is largely up to you, NIH does want you to follow these guidelines:

- Add bold headers or an outlining or numbering system—or both—that you use consistently throughout.

- Start each of the Research Strategy's sections with a header: Significance, Innovation, and Approach.

For an R01, the Research Strategy is limited to 12 pages for the three main sections and the preliminary studies only. Other items are not included in the page limit.

Find instructions for R01s in the SF 424 Application Guide—go to NIH's SF 424 (R&R) Application and Electronic Submission Information for the generic SF 424 Application Guide or find it in your notice of funding opportunity (NOFO).

For most applications, you need to address Rigor and Reproducibility by describing the experimental design and methods you propose and how they will achieve robust and unbiased results. The requirement applies to research grant, career development, fellowship, and training applications.

If you're responding to an institute-specific program announcement (PA) (not a parent program announcement) or a request for applications (RFA), check the NIH Guide notice, which has additional information you need. Should it differ from the NOFO, go with the NIH Guide .

Also note that your application must meet the initiative's objectives and special requirements. NIAID program staff will check your application, and if it is not responsive to the announcement, your application will be returned to you without a review.

When writing your Research Strategy, your goal is to present a well-organized, visually appealing, and readable description of your proposed project. That means your writing should be streamlined and organized so your reviewers can readily grasp the information. If writing is not your forte, get help.

There are many ways to create an outstanding Research Plan, so explore your options.

What Success Looks Like

Your application's Research Plan is the map that shows your reviewers how you plan to test your hypothesis.

It not only lays out your experiments and expected outcomes, but must also convince your reviewers of your likely success by allaying any doubts that may cross their minds that you will be able to conduct the research.

Notice in the sample applications how the writing keeps reviewers' eyes on the ball by bringing them back to the main points the PIs want to make. Write yourself an insurance policy against human fallibility: if it's a key point, repeat it, then repeat it again.

The Big Three

So as you write, put the big picture squarely in your sights. When reviewers read your application, they'll look for the answers to three basic questions:

- Can your research move your field forward?

- Is the field important—will progress make a difference to human health?

- Can you and your team carry out the work?

Add Emphasis

Savvy PIs create opportunities to drive their main points home. They don't stop at the Significance section to emphasize their project's importance, and they look beyond their biosketches to highlight their team's expertise.

Don't take a chance your reviewer will gloss over that one critical sentence buried somewhere in your Research Strategy or elsewhere. Write yourself an insurance policy against human fallibility: if it's a key point, repeat it, then repeat it again.

Add more emphasis by putting the text in bold, or bold italics (in the modern age, we skip underlining—it's for typewriters).

Here are more strategies from our successful PIs:

- While describing a method in the Approach section, they state their or collaborators' experience with it.

- They point out that they have access to a necessary piece of equipment.

- When explaining their field and the status of current research, they weave in their own work and their preliminary data.

- They delve into the biology of the area to make sure reviewers will grasp the importance of their research and understand their field and how their work fits into it.

You can see many of these principles at work in the Approach section of the Application from Dr. William Faubion , "Inflammatory cascades disrupt Treg function through epigenetic mechanisms."

- Reviewers felt that the experiments described for Aim 1 will yield clear results.

- The plans to translate those findings to gene targets of relevance are well outlined and focused.

- He ties his proposed experiments to the larger picture, including past research and strong preliminary data for the current application.

Anticipate Reviewer Questions

Our applicants not only wrote with their reviewers in mind they seemed to anticipate their questions. You may think: how can I anticipate all the questions people may have? Of course you can't, but there are some basic items (in addition to the "big three" listed above) that will surely be on your reviewers' minds:

- Will the investigators be able to get the work done within the project period, or is the proposed work over ambitious?

- Did the PI describe potential pitfalls and possible alternatives?

- Will the experiments generate meaningful data?

- Could the resulting data prove the hypothesis?

- Are others already doing the work, or has it been already completed?

Address these questions; then spend time thinking about more potential issues specific to you and your research—and address those too.

For applications, a picture can truly be worth a thousand words. Graphics can illustrate complex information in a small space and add visual interest to your application.

Look at our sample applications to see how the investigators included schematics, tables, illustrations, graphs, and other types of graphics to enhance their applications.

Consider adding a timetable or flowchart to illustrate your experimental plan, including decision trees with alternative experimental pathways to help your reviewers understand your plans.

Plan Ahead for Video

If you plan to send one or more videos, you'll need to meet certain standards and include key information in your Research Strategy now.

To present some concepts or demonstrations, video may enhance your application beyond what graphics alone can achieve. However, you can't count on all reviewers being able to see or hear video, so you'll want to be strategic in how you incorporate it into your application.

Be reviewer-friendly. Help your cause by taking the following steps:

- Caption any narration in the video.

- Choose evocative still images from your video to accompany your summary.

- Write your summary of the video carefully so the text would make sense even without the video.

In addition to those considerations, create your videos to fit NIH’s technical requirements. Learn more in the SF 424 Form Instructions .

Next, as you write your Research Strategy, include key images from the video and a brief description.

Then, state in your cover letter that you plan to send video later. (Don't attach your files to the application.)

After you apply and get assignment information from the Commons, ask your assigned scientific review officer (SRO) how your business official should send the files. Your video files are due at least one month before the peer review meeting.

Know Your Audience's Perspective

The primary audience for your application is your peer review group. Learn how to write for the reviewers who are experts in your field and those who are experts in other fields by reading Know Your Audience .

Be Organized: A B C or 1 2 3?

In the top-notch applications we reviewed, organization ruled but followed few rules. While you want to be organized, how you go about it is up to you.

Nevertheless, here are some principles to follow:

- Start each of the Research Strategy's sections with a header: Significance, Innovation, and Approach—this you must do.

The Research Strategy's page limit—12 for R01s—is for the three main parts: Significance, Innovation, and Approach and your preliminary studies (or a progress report if you're renewing your grant). Other sections, for example, research animals or select agents, do not have a page limit.

Although you will emphasize your project's significance throughout the application, the Significance section should give the most details. Don't skimp—the farther removed your reviewers are from your field, the more information you'll need to provide on basic biology, importance of the area, research opportunities, and new findings.

When you describe your project's significance, put it in the context of 1) the state of your field, 2) your long-term research plans, and 3) your preliminary data.

In our Sample Applications , you can see that both investigators and reviewers made a case for the importance of the research to improving human health as well as to the scientific field.

Look at the Significance section of the Application from Dr. Mengxi Jiang , "Intersection of polyomavirus infection and host cellular responses," to see how these elements combine to make a strong case for significance.

- Dr. Jiang starts with a summary of the field of polyomavirus research, identifying critical knowledge gaps in the field.

- The application ties the lab's previous discoveries and new research plans to filling those gaps, establishing the significance with context.

- Note the use of formatting, whitespace, and sectioning to highlight key points and make it easier for reviewers to read the text.

After conveying the significance of the research in several parts of the application, check that

- In the Significance section, I describe the importance of my hypothesis to the field (especially if my reviewers are not in it) and human disease.

- I also point out the project's significance throughout the application.

- The application shows that I am aware of opportunities, gaps, roadblocks, and research underway in my field.