- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

‘I Have a Dream,’ Yesterday and Today

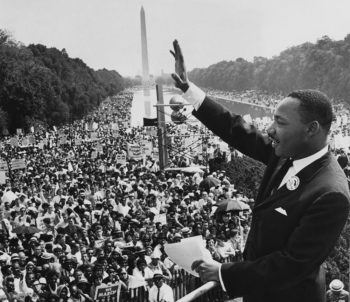

At the March on Washington, where thousands gathered on Saturday to renew the call for equality, participants reflected on Martin Luther King’s historic speech and its themes in the present.

By Darren Sands

Reporting from Washington

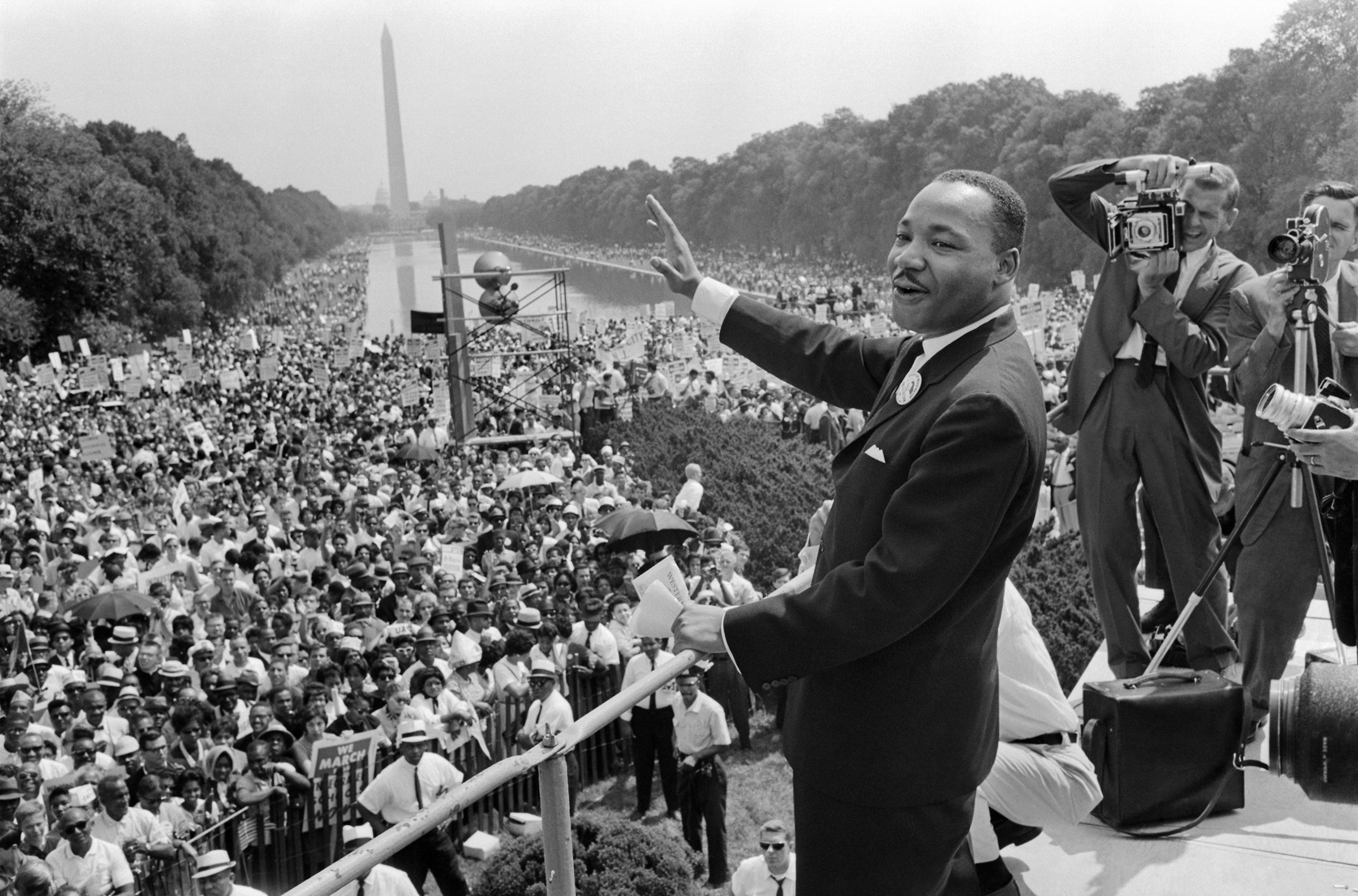

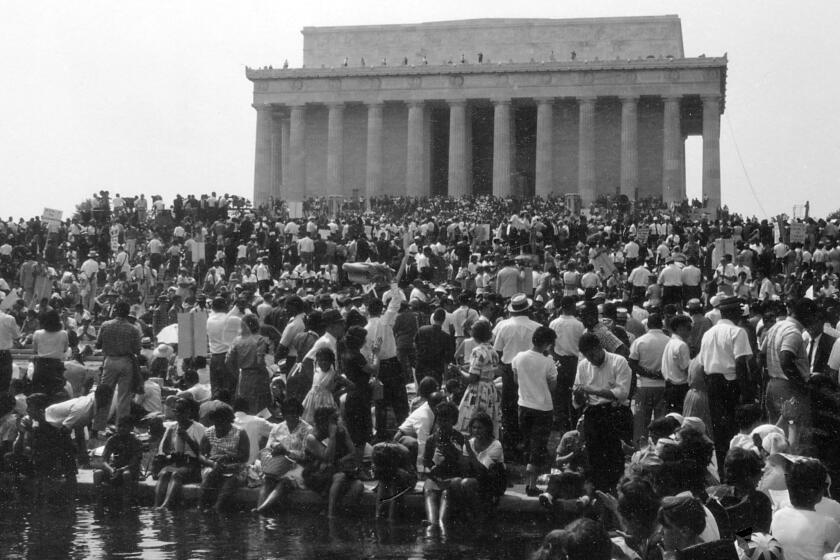

Sixty years after the March on Washington and Martin Luther King’s “I Have a Dream” speech galvanized supporters of the Civil Rights Movement with an anthemic call to action, several thousand people gathered on the National Mall on Saturday to remind the nation of its unfinished work on equality.

Many who turned out, some having also attended the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, traveled from across the country to recall a searing moment in American history that propelled, in the words of one speaker, “the struggle of a lifetime.” The event was convened by the Rev. Al Sharpton and by Martin Luther King III, the son of Martin Luther King Jr. and Coretta Scott King, and was attended by dignitaries including Andrew Young, the former United Nations ambassador and mayor of Atlanta, and the U.S. Representative Hank Johnson of Georgia.

Hovering above all the proceedings, though, were the words delivered by Dr. King six decades ago in front of the Lincoln Memorial, when he took the measure of society a century after slavery was abolished and lamented how Black Americans were “still sadly crippled by the manacles of segregation and the chains of discrimination.”

Though the speech gained renown for its rousing, aspirational coda, other segments decried facets of racial inequality that still resonated with Saturday’s participants. Several attendees who were interviewed — some of them commented on specific excerpts, while others expressed thoughts on Dr. King’s words in general — reflected on the echoes, and the nation, from today’s perspective. Their quotes have been edited for length and clarity.

Martin Luther King on law enforcement

“There are those who are asking the devotees of civil rights, ‘When will you be satisfied?’ We can never be satisfied as long as the Negro is the victim of the unspeakable horrors of police brutality. We can never be satisfied as long as our bodies, heavy with the fatigue of travel, cannot gain lodging in the motels of the highways and the hotels of the cities.”

Jacquealin Yeadon, organizer, National Action Network, Moncks Corner, S.C.

“Police brutality hasn’t gone anywhere — in fact, we deal with it all the time. People dying in jail, in police custody. We’ve got stories upon stories upon stories — of the same thing.”

King on voting rights

“We cannot be satisfied as long as a Negro in Mississippi cannot vote and a Negro in New York believes he has nothing for which to vote.”

Talina Massey, community organizer, entrepreneur, New Bern, N.C.

“This is what’s called voter suppression. Especially in the South with these methods of suppression that make it harder for citizens to vote. This is why we’ve got to keep swinging and not giving up until the fight is won.”

King on justice

But we refuse to believe that the bank of justice is bankrupt. We refuse to believe that there are insufficient funds in the great vaults of opportunity of this nation. And so we’ve come to cash this check, a check that will give us upon demand the riches of freedom and the security of justice.

Grady Smith, retiree, Atlanta

“I came here today because I’ve been a civil rights worker. And we’re here with a lot of civil rights workers and leaders, because we had supported the effort that Martin Luther King put forth years ago about voting rights, equality. We’re still not there. That’s why I’m here.”

King on urgency

“Now is the time to make real the promises of democracy. Now is the time to rise from the dark and desolate valley of segregation to the sunlit path of racial justice. Now is the time to lift our nation from the quicksands of racial injustice to the solid rock of brotherhood. Now is the time to make justice a reality for all of God’s children.”

Nancy Hoover, pediatric nurse practitioner, Damascus, Md.

“I was a freshman in high school in New York when I heard the speech. I wasn’t here, which would have been phenomenal. But now I am. And I feel there’s not been enough progress. It’s like, ‘Come on world, let’s get going. What are we waiting for?’”

King on his dream

“This is our hope. This is the faith that I go back to the South with. With this faith, we will be able to hew out of the mountain of despair a stone of hope. With this faith we will be able to transform the jangling discords of our nation into a beautiful symphony of brotherhood. With this faith we will be able to work together, to pray together, to struggle together, to go to jail together, to stand up for freedom together, knowing that we will be free one day."

Alfonso R. Bernard Sr., New York City, founder, chief executive and pastor, Christian Cultural Center

“He spoke of a dream, an American dream. And here we are 60 years later. Blacks have experienced unprecedented wealth, education. We have more Blacks in positions of power than we have had at any time in the history of America, have an increasing number of Black millionaires. With all that said, we still have the highest rate of poverty. We still have racial disparities in our justice system, policing systems, educational system, health care system and economic opportunity. We still have a long way to go.”

Why “I Have A Dream” Remains One Of History’s Greatest Speeches

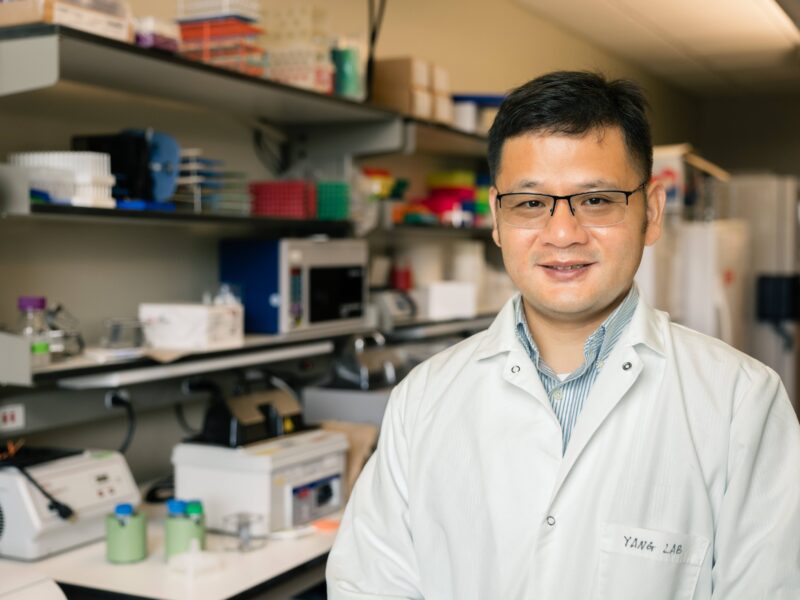

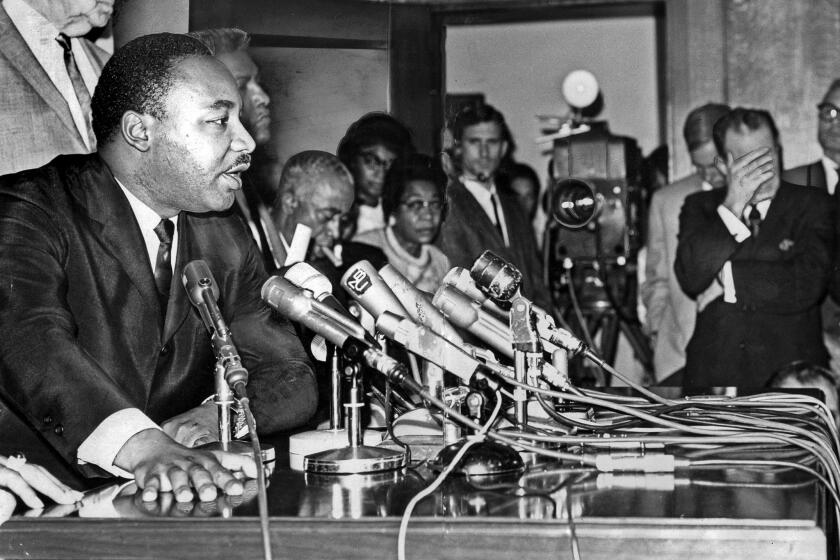

Monday will mark the holiday in honor of Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. and Texas A&M University Professor of Communication Leroy Dorsey is reflecting on King’s celebrated “I Have a Dream” speech, one which he said is a masterful use of rhetorical traditions.

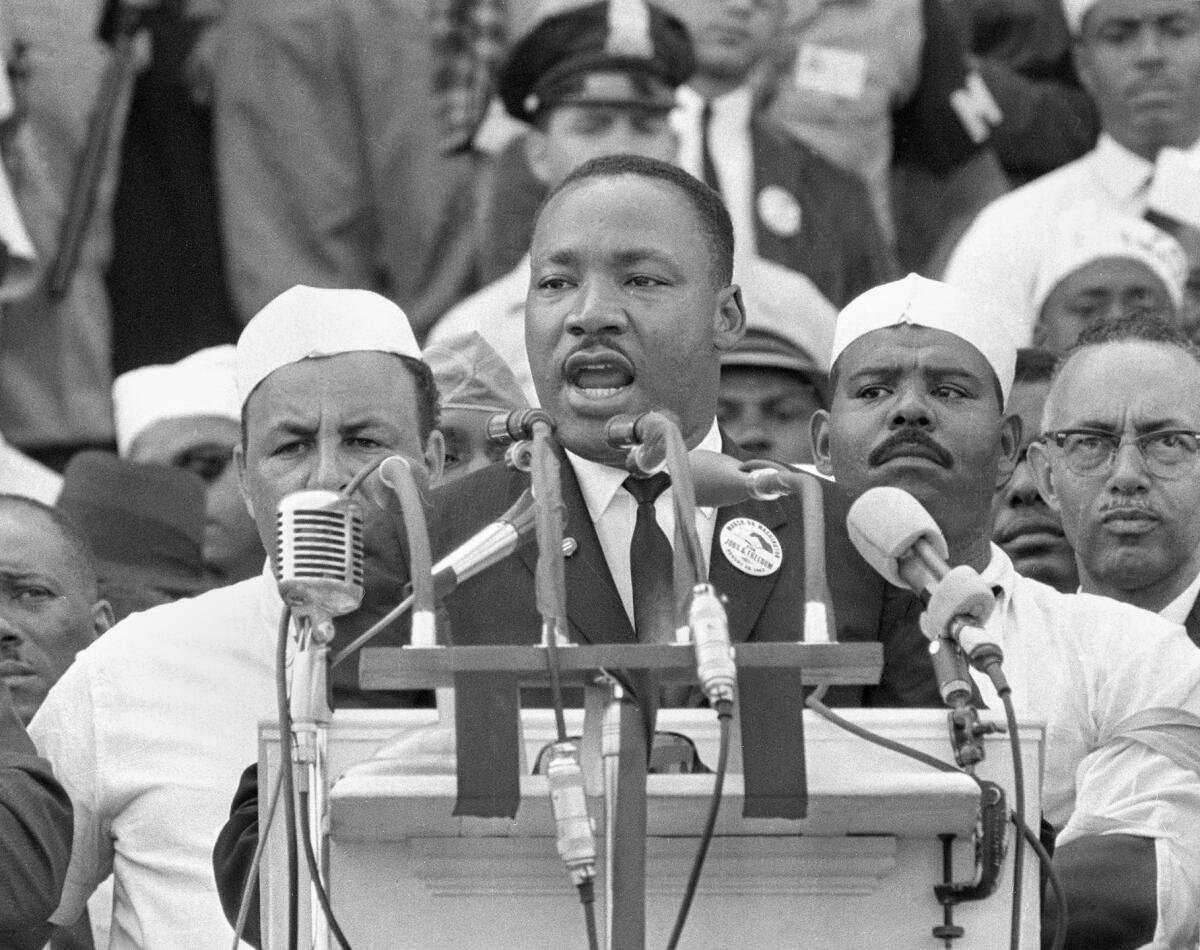

King delivered the famous speech as he stood before a crowd of 250,000 people in front of the Lincoln Memorial on Aug. 28, 1963 during the “March on Washington.” The speech was televised live to an audience of millions.

“He was not just speaking to African Americans, but to all Americans” ~ Leroy Dorsey

Dorsey , associate dean for inclusive excellence and strategic initiatives in the College of Liberal Arts, said one of the reasons the speech stands above all of King’s other speeches – and nearly every other speech ever written – is because its themes are timeless. “It addresses issues that American culture has faced from the beginning of its existence and still faces today: discrimination, broken promises, and the need to believe that things will be better,” he said.

Powerful Use of Rhetorical Devices

Dorsey said the speech is also notable for its use of several rhetorical traditions, namely the Jeremiad, metaphor-use and repetition.

The Jeremiad is a form of early American sermon that narratively moved audiences from recognizing the moral standard set in its past to a damning critique of current events to the need to embrace higher virtues.

“King does that with his invocation of several ‘holy’ American documents such as the Emancipation Proclamation and Declaration of Independence as the markers of what America is supposed to be,” Dorsey said. “Then he moves to the broken promises in the form of injustice and violence. And he then moves to a realization that people need to look to one another’s character and not their skin color for true progress to be made.”

Second, King’s use of metaphors explains U.S. history in a way that is easy to understand, Dorsey said.

“Metaphors can be used to connect an unknown or confusing idea to a known idea for the audience to better understand,” he said. For example, referring to founding U.S. documents as “bad checks” transformed what could have been a complex political treatise into the simpler ideas that the government had broken promises to the American people and that this was not consistent with the promise of equal rights.

The third rhetorical device found in the speech, repetition, is used while juxtaposing contrasting ideas, setting up a rhythm and cadence that keeps the audience engaged and thoughtful, Dorsey said.

“I have a dream” is repeated while contrasting “sons of former slaves and the sons of former slave owners” and “judged by the content of their character” instead of “judged by the color of their skin.” The device was used also with “let freedom ring” which juxtaposes states that were culturally polar opposites – Colorado, California and New York vs. Georgia, Tennessee and Mississippi.

Words That Moved A Movement

The March on Washington and King’s speech are widely considered turning points in the Civil Rights Movement, shifting the demand and demonstrations for racial equality that had mostly occurred in the South to a national stage.

Dorsey said the speech advanced and solidified the movement because “it became the perfect response to a turbulent moment as it tried to address past hurts, current indifference and potential violence, acting as a pivot point between the Kennedy administration’s slow response and the urgent response of the ‘marvelous new militancy’ [those fighting against racism].”

What made King such an outstanding orator were the communication skills he used to stir audience passion, Dorsey said. “When you watch the speech, halfway through he stops reading and becomes a pastor, urging his flock to do the right thing,” he said. “The cadence, power and call to the better nature of his audience reminds you of a religious service.”

Lessons For Today

Dorsey said the best leaders are those who can inspire all without dismissing some, and that King in his famous address did just that.

“He was not just speaking to African Americans in that speech, but to all Americans, because he understood that the country would more easily rise together when it worked together,” he said.

“I Have a Dream” remains relevant today “because for as many strides that have been made, we’re still dealing with the elements of a ‘bad check’ – voter suppression, instances of violence against people of color without real redress, etc.,” Dorsey said. “Remembering what King was trying to do then can provide us insight into what we need to consider now.”

Additionally, King understood that persuasion doesn’t move from A to Z in one fell swoop, but it moves methodically from A to B, B to C, etc., Dorsey said. “In the line ‘I have a dream that one day ,’ he recognized that things are not going to get better overnight, but such sentiment is needed to help people stay committed day-to-day until the country can honestly say, ‘free at last!'”

Media contact: Lesley Henton, 979-845-5591, [email protected].

Related Stories

MSC SCOLA Illuminates Path To Success

The three-day Student Conference on Latinx Affairs offers opportunities for learning, leadership and growth.

Asian Pacific Islander Desi American Heritage Month Events

A variety of campus organizations are inviting the Aggie community for unique cultural experiences.

MSC SCOLA 2023: ‘Focusing On The Present To Ensure Our Future’

The MSC Student Conference On Latinx Affairs (SCOLA) will challenge student leaders to focus on the influence of the Latinx community.

Recent Stories

Is Smallpox Still A Threat?

A Texas A&M scientist has collaborated on a new report that warns of its potential return and urges heightened preparedness.

Workplace Law Expert Examines Starbucks Supreme Court Bid

Starbucks is seeking protection from being ordered to rehire baristas who say they were fired for union-promoting activities. Professor Michael Z. Green explains how the case could affect the right to organize unions in the U.S.

Freestanding Emergency Departments Are Popular, But Do They Function As Intended?

School of Public Health study is the first of its kind to compare characteristics of visits among all emergency department types

Subscribe to the Texas A&M Today newsletter for the latest news and stories every week.

HISTORIC ARTICLE

Aug 28, 1963 ce: martin luther king jr. gives "i have a dream" speech.

On August 28, 1963, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., gave his "I Have a Dream" speech at the March on Washington, a large gathering of civil rights protesters in Washington, D.C., United States.

Social Studies, Civics, U.S. History

Loading ...

On August 28, 1963, Martin Luther King, Jr., took the podium at the March on Washington and addressed the gathered crowd, which numbered 200,000 people or more. His speech became famous for its recurring phrase “I have a dream.” He imagined a future in which “the sons of former slaves and the sons of former slave owners" could "sit down together at the table of brotherhood,” a future in which his four children are judged not "by the color of their skin but by the content of their character." King's moving speech became a central part of his legacy. King was born in Atlanta, Georgia, United States, in 1929. Like his father and grandfather, King studied theology and became a Baptist pastor . In 1957, he was elected president of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference ( SCLC ), which became a leading civil rights organization. Under King's leadership, the SCLC promoted nonviolent resistance to segregation, often in the form of marches and boycotts. In his campaign for racial equality, King gave hundreds of speeches, and was arrested more than 20 times. He won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1964 for his "nonviolent struggle for civil rights ." On April 4, 1968, King was shot and killed while standing on a balcony of his motel room in Memphis, Tennessee, U.S.

Media Credits

The audio, illustrations, photos, and videos are credited beneath the media asset, except for promotional images, which generally link to another page that contains the media credit. The Rights Holder for media is the person or group credited.

Last Updated

October 19, 2023

User Permissions

For information on user permissions, please read our Terms of Service. If you have questions about how to cite anything on our website in your project or classroom presentation, please contact your teacher. They will best know the preferred format. When you reach out to them, you will need the page title, URL, and the date you accessed the resource.

If a media asset is downloadable, a download button appears in the corner of the media viewer. If no button appears, you cannot download or save the media.

Text on this page is printable and can be used according to our Terms of Service .

Interactives

Any interactives on this page can only be played while you are visiting our website. You cannot download interactives.

Related Resources

“I Have A Dream”: Annotated

Martin Luther King, Jr.’s iconic speech, annotated with relevant scholarship on the literary, political, and religious roots of his words.

For this month’s Annotations, we’ve taken Martin Luther King, Jr.’s iconic “I Have A Dream” speech, and provided scholarly analysis of its groundings and inspirations—the speech’s religious, political, historical and cultural underpinnings are wide-ranging and have been read as jeremiad, call to action, and literature. While the speech itself has been used (and sometimes misused) to call for a “color-blind” country, its power is only increased by knowing its rhetorical and intellectual antecedents.

Five score years ago, a great American, in whose symbolic shadow we stand signed the Emancipation Proclamation . This momentous decree came as a great beacon light of hope to millions of Negro slaves who had been seared in the flames of withering injustice. It came as a joyous daybreak to end the long night of captivity.

But one hundred years later, we must face the tragic fact that the Negro is still not free. One hundred years later, the life of the Negro is still sadly crippled by the manacles of segregation and the chains of discrimination. One hundred years later, the Negro lives on a lonely island of poverty in the midst of a vast ocean of material prosperity. One hundred years later, the Negro is still languishing in the corners of American society and finds himself an exile in his own land. So we have come here today to dramatize an appalling condition.

In a sense we have come to our nation’s capital to cash a check. When the architects of our republic wrote the magnificent words of the Constitution and the declaration of Independence, they were signing a promissory note to which every American was to fall heir. This note was a promise that all men would be guaranteed the inalienable rights of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.

It is obvious today that America has defaulted on this promissory note insofar as her citizens of color are concerned. Instead of honoring this sacred obligation, America has given the Negro people a bad check which has come back marked “insufficient funds.” But we refuse to believe that the bank of justice is bankrupt. We refuse to believe that there are insufficient funds in the great vaults of opportunity of this nation. So we have come to cash this check — a check that will give us upon demand the riches of freedom and the security of justice. We have also come to this hallowed spot to remind America of the fierce urgency of now . This is no time to engage in the luxury of cooling off or to take the tranquilizing drug of gradualism. Now is the time to rise from the dark and desolate valley of segregation to the sunlit path of racial justice. Now is the time to open the doors of opportunity to all of God’s children. Now is the time to lift our nation from the quicksands of racial injustice to the solid rock of brotherhood.

It would be fatal for the nation to overlook the urgency of the moment and to underestimate the determination of the Negro. This sweltering summer of the Negro’s legitimate discontent will not pass until there is an invigorating autumn of freedom and equality. Nineteen sixty-three is not an end, but a beginning. Those who hope that the Negro needed to blow off steam and will now be content will have a rude awakening if the nation returns to business as usual. There will be neither rest nor tranquility in America until the Negro is granted his citizenship rights. The whirlwinds of revolt will continue to shake the foundations of our nation until the bright day of justice emerges.

But there is something that I must say to my people who stand on the warm threshold which leads into the palace of justice. In the process of gaining our rightful place we must not be guilty of wrongful deeds. Let us not seek to satisfy our thirst for freedom by drinking from the cup of bitterness and hatred .

We must forever conduct our struggle on the high plane of dignity and discipline. We must not allow our creative protest to degenerate into physical violence. Again and again we must rise to the majestic heights of meeting physical force with soul force. The marvelous new militancy which has engulfed the Negro community must not lead us to distrust of all white people, for many of our white brothers, as evidenced by their presence here today, have come to realize that their destiny is tied up with our destiny and their freedom is inextricably bound to our freedom. We cannot walk alone.

And as we walk, we must make the pledge that we shall march ahead. We cannot turn back. There are those who are asking the devotees of civil rights, “When will you be satisfied?” We can never be satisfied as long as our bodies, heavy with the fatigue of travel, cannot gain lodging in the motels of the highways and the hotels of the cities. We cannot be satisfied as long as the Negro’s basic mobility is from a smaller ghetto to a larger one. We can never be satisfied as long as a Negro in Mississippi cannot vote and a Negro in New York believes he has nothing for which to vote. No, no, we are not satisfied, and we will not be satisfied until justice rolls down like waters and righteousness like a mighty stream.

I am not unmindful that some of you have come here out of great trials and tribulations. Some of you have come fresh from narrow cells. Some of you have come from areas where your quest for freedom left you battered by the storms of persecution and staggered by the winds of police brutality. You have been the veterans of creative suffering. Continue to work with the faith that unearned suffering is redemptive.

Go back to Mississippi, go back to Alabama, go back to Georgia, go back to Louisiana, go back to the slums and ghettos of our northern cities, knowing that somehow this situation can and will be changed. Let us not wallow in the valley of despair.

I say to you today, my friends, that in spite of the difficulties and frustrations of the moment, I still have a dream. It is a dream deeply rooted in the American dream .

I have a dream that one day this nation will rise up and live out the true meaning of its creed: “We hold these truths to be self-evident: that all men are created equal.”

I have a dream that one day on the red hills of Georgia the sons of former slaves and the sons of former slaveowners will be able to sit down together at a table of brotherhood.

I have a dream that one day even the state of Mississippi, a desert state, sweltering with the heat of injustice and oppression, will be transformed into an oasis of freedom and justice.

I have a dream that my four children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character.

I have a dream today.

I have a dream that one day the state of Alabama, whose governor’s lips are presently dripping with the words of interposition and nullification, will be transformed into a situation where little black boys and black girls will be able to join hands with little white boys and white girls and walk together as sisters and brothers.

I have a dream that one day every valley shall be exalted , every hill and mountain shall be made low, the rough places will be made plain, and the crooked places will be made straight, and the glory of the Lord shall be revealed, and all flesh shall see it together.

This is our hope. This is the faith with which I return to the South. With this faith we will be able to hew out of the mountain of despair a stone of hope. With this faith we will be able to transform the jangling discords of our nation into a beautiful symphony of brotherhood . With this faith we will be able to work together, to pray together, to struggle together, to go to jail together, to stand up for freedom together, knowing that we will be free one day.

Weekly Newsletter

Get your fix of JSTOR Daily’s best stories in your inbox each Thursday.

Privacy Policy Contact Us You may unsubscribe at any time by clicking on the provided link on any marketing message.

This will be the day when all of God’s children will be able to sing with a new meaning, “My country, ’tis of thee, sweet land of liberty, of thee I sing. Land where my fathers died, land of the pilgrim’s pride, from every mountainside, let freedom ring.”

And if America is to be a great nation this must become true. So let freedom ring from the prodigious hilltops of New Hampshire. Let freedom ring from the mighty mountains of New York. Let freedom ring from the heightening Alleghenies of Pennsylvania!

Let freedom ring from the snowcapped Rockies of Colorado!

Let freedom ring from the curvaceous peaks of California!

But not only that; let freedom ring from Stone Mountain of Georgia!

Let freedom ring from Lookout Mountain of Tennessee!

Let freedom ring from every hill and every molehill of Mississippi. From every mountainside, let freedom ring.

When we let freedom ring, when we let it ring from every village and every hamlet, from every state and every city, we will be able to speed up that day when all of God’s children, black men and white men, Jews and Gentiles, Protestants and Catholics, will be able to join hands and sing in the words of the old Negro spiritual, “Free at last! free at last! Thank God Almighty, we are free at last!”

For dynamic annotations of this speech and other iconic works, see The Understanding Series from JSTOR Labs .

Support JSTOR Daily! Join our new membership program on Patreon today.

JSTOR is a digital library for scholars, researchers, and students. JSTOR Daily readers can access the original research behind our articles for free on JSTOR.

Get Our Newsletter

More stories.

- Colorful Lights to Cure What Ails You

- Ayahs Abroad: Colonial Nannies Cross The Empire

The Taj Mahal Today

Beryl Markham, Warrior of the Skies

Recent posts.

- The Industrial Revolution and the Rise of Policing

- A Brief Guide to Birdwatching in the Age of Dinosaurs

- Vulture Cultures

Support JSTOR Daily

Sign up for our weekly newsletter.

How We Remember the 'I Have a Dream' Speech 50 Years Later

In honor of the 50th anniversary of the March on Washington and Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.'s iconic "I Have a Dream" speech, news outlets, veterans of the march, and the global community have come together to reflect on that historic day.

In honor of the 50th anniversary of the March on Washington and Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.'s iconic "I Have a Dream" speech, news outlets, veterans of the march and the global community have come together to reflect on that historic day. Some remembrances, like Google's "I Have a Dream" doodle and tweets of the speech, have been small, while others have inspired long essays on how we still feel effects of the speech today. The New York Times ' Michicko Kakutani describes how the most powerful parts of King's speech were improvised on the spot:

Dr. King was about halfway through his prepared speech when Mahalia Jackson... shouted out to him from the speakers’ stand: “Tell ’em about the ‘Dream,’ Martin, tell ’em about the ‘Dream’!” She was referring to a riff he had delivered on earlier occasions, and Dr. King pushed the text of his remarks to the side and began an extraordinary improvisation on the dream theme that would become one of the most recognizable refrains in the world.

Kakutani's notes King's ability to "convey the urgency of his arguments through language richly layered with biblical and historical meanings." And then there's the evidence of King's legacy today. The speech "can still move people to tears," she writes. Just as King was inspired by the Bible and Abraham Lincoln's Gettysburg address, President Obama was inspired by King. Kakutani writes:

President Obama, who once wrote about his mother’s coming home “with books on the civil rights movement, the recordings of Mahalia Jackson, the speeches of Dr. King,” has described the leaders of the movement as “giants whose shoulders we stand on.” Some of his own speeches owe a clear debt to Dr. King’s ideas and words.

Several newspapers dug through the archives to post their 1963 coverage of the speech, which gives a sense of how the country saw the march when it happened. The New York Times tweeted a PDF of its front page the day after the march.

And The Washington Post released an interactive version of their cover, linking to the full text of the stories. "More than 200,000 persons jammed the Mall here yesterday in the biggest civil rights demonstration in the Nation’s history," Robert E. Baker wrote in a story published on August 29, 1963 paper. "This was the 'March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom', a one-day rally demanding a breakthrough in civil rights for Negroes." But as Politico's Mike Allen notes, the Post didn't include a single line from King's speech, only noting he was a speaker at the end of the article.

The Afro-American , a Baltimore weekly paper, went with a bolder headline :

Powerful front page of The Afro-American 50 years earlier on the March on Washington. pic.twitter.com/EElrUYf4Al — andrew kaczynski (@KFILE) August 24, 2013

The Dalai Lama, riffing on the "Dream" ideology, posted a YouTube video on Tuesday expressing his own dream, that this century the world might become a global family. "In order to achieve that, we need a sense of oneness of humanity," he said.

But the most compelling tributes came from people who were there at the march 50 years ago. “You could just feel the energy around, not screaming, not hollering, but an atmosphere of togetherness," Dr. Shirley Johnson told NBC Miami . "I remember every detail like it was an hour ago, as if it were a film loop in my brain," David Morrison told Lancaster Online .

Rep. John Lewis of Georgia was the youngest person to speak at the march, and as he said in the video below, he's the only march speaker still alive today. In the video he spoke with Bill Moyers, students and tourists, walking them through his memories of the day. "I felt very honored to be there on that date, 50 years ago, and I feel honored to have an opportunity to come here almost 50 years later," Lewis said.

Lewis talked about the march with Stephen Colbert earlier this month .

The New York Times

The learning network | text to text | ‘i have a dream’ and ‘the lasting power of dr. king’s dream speech’.

Text to Text | ‘I Have a Dream’ and ‘The Lasting Power of Dr. King’s Dream Speech’

American History

Teaching ideas based on New York Times content.

- See all in American History »

- See all lesson plans »

Last summer was the 50th anniversary of the March on Washington, when the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. painted his dream of racial equality and justice for the nation that still resonates with us. “I have a dream,” he proclaimed, “my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character.” In this Text to Text , we pair Dr. King’s pivotal “I Have a Dream” speech with a reflection by the Times literary critic Michiko Kakutani, who explores why this singular speech has such lasting power.

Background: The speech that the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. delivered on Aug. 28, 1963, on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial was not the speech he had prepared in his notes and stayed up nearly all night writing.

Dr. King was the closing speaker at the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, and the “Dream” speech that inspired a nation and helped galvanize the civil rights movement almost never happened. The march itself almost never happened, as David Brooks writes , because the Urban League, the N.A.A.C.P. and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference either chose to opt out or were focusing their energy elsewhere before the events in Birmingham, Ala., in May 1963, with fire hoses and snapping dogs turned on protesters, helped reignite the call for a national march. The speech almost never happened because Dr. King didn’t think he had time to say all he wanted to say in the five minutes he was allotted — at the end of a long, hot summer day before the crowds were ready to disperse and go home.

But Dr. King was “the son, grandson and great-grandson of Baptist ministers,” Michiko Kakutani writes, and he “was comfortable with the black church’s oral tradition, and he knew how to read his audience and react to it.” In the middle of his speech, the gospel singer Mahalia Jackson urged him from behind the podium, “Tell ’em about the ‘Dream,’ Martin, tell ’em about the ‘Dream’!” She was referring to a riff he had delivered many times before, and in that moment, Dr. King broke from his prepared remarks and shared his transcendent vision for the nation’s future.

Below, we excerpted only the first part of Dr. King’s speech, but students should read the entire speech or this abridged version (PDF). For greater effect, they can listen to the audio or watch the video of Dr. King’s delivery while they read along.

Ms. Kakutani, a Pulitzer Prize-winning literary critic for The Times, reflects on the speech’s lasting power on the 50th anniversary of the March on Washington. We offer an excerpt that introduces her analysis, but we recommend that students read the entire article to explore her evidence for what makes the speech so remarkable.

Key Questions: Why is Martin Luther King’s “I Have a Dream” speech so powerful, even 50 years later?

Activity Sheets: As students read and discuss, they might take notes using one or more of the three graphic organizers (PDFs) we have created for our Text to Text feature:

- Comparing Two or More Texts

- Double-Entry Chart for Close Reading

- Document Analysis Questions

Excerpt 1: From “The Lasting Power of Dr. King’s Dream Speech,” by Michiko Kakutani

It was late in the day and hot, and after a long march and an afternoon of speeches about federal legislation, unemployment and racial and social justice, the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. finally stepped to the lectern, in front of the Lincoln Memorial, to address the crowd of 250,000 gathered on the National Mall. He began slowly, with magisterial gravity, talking about what it was to be black in America in 1963 and the “shameful condition” of race relations a hundred years after the Emancipation Proclamation. Unlike many of the day’s previous speakers, he did not talk about particular bills before Congress or the marchers’ demands. Instead, he situated the civil rights movement within the broader landscape of history — time past, present and future — and within the timeless vistas of Scripture. Dr. King was about halfway through his prepared speech when Mahalia Jackson — who earlier that day had delivered a stirring rendition of the spiritual “I Been ’Buked and I Been Scorned” — shouted out to him from the speakers’ stand: “Tell ’em about the ‘Dream,’ Martin, tell ’em about the ‘Dream’!” She was referring to a riff he had delivered on earlier occasions, and Dr. King pushed the text of his remarks to the side and began an extraordinary improvisation on the dream theme that would become one of the most recognizable refrains in the world. With his improvised riff, Dr. King took a leap into history, jumping from prose to poetry, from the podium to the pulpit. His voice arced into an emotional crescendo as he turned from a sobering assessment of current social injustices to a radiant vision of hope — of what America could be. “I have a dream,” he declared, “my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character. I have a dream today!” Many in the crowd that afternoon, 50 years ago on Wednesday, had taken buses and trains from around the country. Many wore hats and their Sunday best — “People then,” the civil rights leader John Lewis would recall, “when they went out for a protest, they dressed up” — and the Red Cross was passing out ice cubes to help alleviate the sweltering August heat. But if people were tired after a long day, they were absolutely electrified by Dr. King. There was reverent silence when he began speaking, and when he started to talk about his dream, they called out, “Amen,” and, “Preach, Dr. King, preach,” offering, in the words of his adviser Clarence B. Jones, “every version of the encouragements you would hear in a Baptist church multiplied by tens of thousands.” You could feel “the passion of the people flowing up to him,” James Baldwin, a skeptic of that day’s March on Washington, later wrote, and in that moment, “it almost seemed that we stood on a height, and could see our inheritance; perhaps we could make the kingdom real.” Dr. King’s speech was not only the heart and emotional cornerstone of the March on Washington, but also a testament to the transformative powers of one man and the magic of his words. Fifty years later, it is a speech that can still move people to tears. Fifty years later, its most famous lines are recited by schoolchildren and sampled by musicians. Fifty years later, the four words “I have a dream” have become shorthand for Dr. King’s commitment to freedom, social justice and nonviolence, inspiring activists from Tiananmen Square to Soweto, Eastern Europe to the West Bank. Why does Dr. King’s “Dream” speech exert such a potent hold on people around the world and across the generations? Part of its resonance resides in Dr. King’s moral imagination. Part of it resides in his masterly oratory and gift for connecting with his audience — be they on the Mall that day in the sun or watching the speech on television or, decades later, viewing it online. And part of it resides in his ability, developed over a lifetime, to convey the urgency of his arguments through language richly layered with biblical and historical meanings….

Excerpt 2: From “I Have a Dream,” by the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

Five score years ago, a great American, in whose symbolic shadow we stand today, signed the Emancipation Proclamation. This momentous decree came as a great beacon light of hope to millions of Negro slaves who had been seared in the flames of withering injustice. It came as a joyous daybreak to end the long night of their captivity. But 100 years later, the Negro still is not free. One hundred years later, the life of the Negro is still sadly crippled by the manacles of segregation and the chains of discrimination. One hundred years later, the Negro lives on a lonely island of poverty in the midst of a vast ocean of material prosperity. One hundred years later, the Negro is still languished in the corners of American society and finds himself an exile in his own land. And so we’ve come here today to dramatize a shameful condition. In a sense we’ve come to our nation’s capital to cash a check. When the architects of our republic wrote the magnificent words of the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence, they were signing a promissory note to which every American was to fall heir. This note was a promise that all men — yes, black men as well as white men — would be guaranteed the unalienable rights of life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness. It is obvious today that America has defaulted on this promissory note insofar as her citizens of color are concerned. Instead of honoring this sacred obligation, America has given the Negro people a bad check, a check that has come back marked “insufficient funds.” But we refuse to believe that the bank of justice is bankrupt. We refuse to believe that there are insufficient funds in the great vaults of opportunity of this nation. And so we’ve come to cash this check, a check that will give us upon demand the riches of freedom and security of justice. We have also come to this hallowed spot to remind America of the fierce urgency of now. This is no time to engage in the luxury of cooling off or to take the tranquilizing drug of gradualism. Now is the time to make real the promises of democracy. Now is the time to rise from the dark and desolate valley of segregation to the sunlit path of racial justice. Now is the time to lift our nation from the quicksands of racial injustice to the solid rock of brotherhood. Now is the time to make justice a reality for all of God’s children….

For Writing or Discussion

- Michiko Kakutani asks: “Why does Dr. King’s ‘Dream’ speech exert such a potent hold on people around the world and across the generations?” What answer does she provide? What is the most powerful evidence she uses to back up her analysis?

- Ms. Kakutani explains that “with his improvised riff, Dr. King took a leap into history, jumping from prose to poetry, from the podium to the pulpit.” What does she mean by that description?

- After reading, listening or watching Dr. King’s “Dream” speech, describe your reaction. What do you find powerful or moving in the speech? Do you have a favorite line or phrase? Explain.

- How does Dr. King use figurative language and other poetic and oratorical devices, such as repetition and theme, to make his speech more powerful?

- What historical and biblical allusions do you recognize within the speech? Which allusions do you find most compelling, and why?

- Have we achieved Dr. King’s dream 50 years later? What progress do you think this country has made since the March on Washington with regard to civil rights? What progress do we still need to make? Cite evidence to support your opinion.

Going Further

1. Witnesses to History: How did people at the time react — to Dr. King’s “Dream” speech as well as to the march as a whole? The Times gathered reflections from readers who attended the march . Choose one or two memories to read in the Interactive. What was most powerful about the march for them? What was their recollection of Dr. King’s speech?

Alternatively, read James Reston’s 1963 news analysis published the day after the march in The Times to understand one contemporary critic’s perspective. Mr. Reston writes:

It was Dr. King who, near the end of the day, touched the vast audience…. But Dr. King brought them alive in the late afternoon with a peroration that was an anguished echo from all the old American reformers. Roger Williams calling for religious liberty. Sam Adams calling for political liberty, old man Thoreau denouncing coercion, William Lloyd Garrison demanding emancipation, and Eugene V. Debs crying for economic equality — Dr. King echoed them all. “I have a dream,” he cried again and again. And each time the dream was a promise out of our ancient articles of faith: phrases from the Constitution. lines from the great anthem of the nation, guarantees from the Bill of Rights, all ending with a vision that they all one day might come true.

How does Mr. Reston view the “Dream” speech? What additional insights does this news analysis give you about how The Times, or the mainstream news media in general, might have viewed the event at the time?

2. Other Civil Rights Speeches: Dr. King’s “Dream” speech is the best known of a long line of civil rights speeches. The Times collected other speeches that have influenced perceptions of race in America, including Malcolm X’s “The Ballot or the Bullet” and Fannie Lou Hamer’s testimony at the 1964 Democratic National Convention. Choose one speech and compare it to “I Have a Dream” in both tone and message.

3. Nonviolent Resistance: Dr. King’s speech was grounded in a larger movement committed to nonviolent resistance. Read the Times columnist David Brooks’s “The Ideas Behind the March,” and then consider the following questions:

- Mr. Brooks writes: “Nonviolent coercion was an ironic form of aggression. Nonviolence furnished the movement with a series of tactics that allowed it to remain on permanent offense.” What does he mean by that? How does this analysis help explain why nonviolence is often so effective?

- What current issue do you think would be well served by a nonviolent reform movement like the civil rights movement? Why is this issue important to you, and what actions would you want such a movement to take to make change?

4. Assessing the Dream: Daniel R. Smith attended both the March on Washington in 1963 and the 50th anniversary commemoration last August. Five decades after Dr. King’s historic speech, Mr. Smith reflected on how much progress the nation has made in terms of civil rights, but he also wondered if “the pace has slowed considerably.” Read “50 Years After March, Views of Fitful Progress” and study the related graphic analyzing change over time in key areas like education and jobs. How much progress do you think the country has made in civil rights since 1963? How much progress do we still need to make? Cite evidence to support your opinion.

More Resources:

Celebrating M.L.K. Day — news articles, Opinion articles, multimedia and lesson plans related to Dr. King and the civil rights movement

Additional Lesson Plans — by the Gilder Lehrman Institute and PBS for middle school and high school students

This resource may be used to address the academic standards listed below.

Common Core E.L.A. Anchor Standards

1 Read closely to determine what the text says explicitly and to make logical inferences from it; cite specific textual evidence when writing or speaking to support conclusions drawn from the text.

2 Determine central ideas or themes of a text and analyze their development; summarize the key supporting details and ideas.

4 Interpret words and phrases as they are used in a text, including determining technical, connotative, and figurative meanings, and analyze how specific word choices shape meaning or tone.

5 Analyze the structure of texts, including how specific sentences, paragraphs, and larger portions of the text (e.g., a section, chapter, scene, or stanza) relate to each other and the whole.

Comments are no longer being accepted.

Another fantastic lesson plan. I teach AP English Language and Composition. King’s writings are an essential part of the curriculum; these ideas will be great springboards for discussion. Thank you!

James Mulhern, //www.synthesizingeducation.net Atlantic Technical Center Magnet High School Coconut Creek, Florida

Remarkable Rev, Dr Martin Luther King, an exemplary and epitome of peace movement, who has shown extreme rationality in pursuit of justice, equality and freedom without any violence, taught us how to live a life with a high plane of dignity and prosperity, a life of liberty and equality, a life of complete unanimity and harmony in regard with racism. He taught us the real meaning of revolution……. revolution forwarded to bring the bright and sparkling light of hope of peace and tranquillity. His philosophies, ideologies and of course his dream for AMERICANS reflect his heart which is replete with abundance of humanity, compassion, fraternity and brotherhood. Yes, I have a dream and the dream is to live your dream.

Martin Luther King Jr. had the most memorable speak ever in the history of time. Something new that I have learned about Dr. King’s speech is that it was not the one he had prepared for the event. It amazes me that he still managed to say such a magnificent speak and it was not the one he was preparing for it just happened. I think Martin Luther King Jr. speech of “I Have a Dream” is still so powerful till this day is because it was something he was fighting for, for everybody and it was something that was so unique to everybody to hear it was wonderful. The main reason for the speech is for everyone to see that we are equal and for the future to be better than how it was, it just needed to be different. Many people loved the speech that he did but then again there were also others who disliked for the meaning it was about. The people who did not like it probably did not like it because they wanted it to stay the same and were probably taught to hate on others for a reason. Martin to me was a very unique man for doing what he did but there were also others who did the same thing and stood up for what they believed in. Everyone including Martin made others realize what was going on and things needed to be different. So it gave others confidence to do something towards a situation that they may not like and to say something about. The speech was a very peaceful way to say what the problem of the situation was it was not a violent thing to do but it was also dangerous. He did not care that if some were hating on him because of the speech or what he was doing, he must have been proud for what he was doing, I now I would be proud. This speech will always be around and very memorable till this day and till the future.

What's Next

How Martin Luther King Jr. Changed His Mind About America

M ore than fifty years after his death, Martin Luther King Jr. remains a towering figure in the history of American civil rights. As with most influential thinkers, there is a certain amount of ambiguity in the public understanding of King and his legacy. White Americans were very skeptical of King while he was alive, but as his reputation and popularity grew, advocates of very different positions tried to claim him for their own. Nowadays conservatives are fond of invoking his most famous speech, 1963’s I Have a Dream , with its vision of a world in where people “will not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character.” Progressives are fonder of The Other America , a more radical speech from 1967, where he said that we may “have to repent in this generation not merely for the vitriolic words of the bad people and the violent actions of the bad people, but for the appalling silence and indifference of the good people who sit around and say ‘wait on time.’”

Those two Kings are ones we know, but there are other Kings we need to listen to as well. The I Have a Dream speech gives us the standard story of America. According to this story, America starts with the Declaration of Independence, which states our foundational values, particularly equality. The Founders’ Constitution turns these values into law—imperfectly at first, but American history is a progress towards redeeming the “promissory note” of the Declaration, and one day we will “live out the true meaning of … ‘all men are created equal.’”

This story is comforting and reassuring, but it is actually a barrier to progress, as the King of The Other America came to see. For one thing, it supports what he called the indifference of the good people, the idea that social progress “rolls in on the wheels of inevitability.” For another, it tells us to look to Founding America and the Declaration of Independence as the source of our fundamental ideals. But doing that tells us that those ideals can co-exist with white supremacy. The truth is that Founding America was not a nation dedicated to our idea of equality. The Betsy Ross flag shows us thirteen stars in a circle, and every star represents a state where slavery was legal.

The idea that the Declaration provides the way forward is deeply problematic. A younger King saw this. As a junior in high school in 1944, competing in a debate contest, he delivered a speech called The Negro and the Constitution . Like I Have a Dream , this speech examined whether the treatment of Blacks in America was consistent with American values. But unlike I Have a Dream , it did not locate those values in the Founding. “America gave its full pledge of freedom seventy-five years ago,” King said: in 1868, when the 14th Amendment was ratified. The Civil War and Reconstruction created a “new order,” he said, “backed by amendments to the national constitution.” It is these amendments, not the Declaration, that promised equality.

Read More: What It Is Was Like Hearing Martin Luther King Jr. Give ‘I Have a Dream’ Speech

The focus on Reconstruction gives us a different origin story. This one tells us our mission is to take up the struggle of a war for liberty and a remaking of society in pursuit of justice and equality. It is less reassuring, which is presumably why King abandoned it in I Have a Dream , seeking to enlist white moderates in his cause. But the allies he won turned out to be the“good people” of The Other America who sat by and counseled patience. And if this story is more divisive, it is also more true. In the Civil War, the U.S. issued an emancipation proclamation—in the Revolution, the British did. In the Reconstruction Constitution, the U.S. banned slavery—in the Founders’ Constitution, they protected it. And it is more inclusive; it locates our values not in documents written by white slaveowners but by those who fought to end slavery, blacks as well as whites.

This is a better story. And it is the story that King came back to. The day before his assassination in 1968, he spoke in Memphis, where sanitation workers were striking for decent wages and working conditions . King was ill that night and had asked a friend to speak in his place, but when he heard that hundreds of supporters were waiting to hear him, he went to the Mason Temple, took the stage, and spoke extemporaneously. I’ve Been to the Mountaintop starts by considering the question of what moment in human history King would like to live in. He considers some of the high points of antiquity—classical Greece and Rome, the Renaissance. He ignores the Founding entirely—the first moment of American history that gets a reference is the signing of the Emancipation Proclamation. In the end, King says he would like to live just where he is, because “Something is happening in our world. The masses of people are rising up. And … the cry is always the same: ‘We want to be free.’”

We march for freedom, King told his listeners, and we will win if we stick together. He knew that freedom had a cost. “I may not get there with you.” But “we, as a people, will get to the promised land.” And he sent the audience out into the night with one final spur, invoking the great clash where white and black Americans fought together for the freedom of all. The last line of the last speech that King ever delivered is not from the Declaration or the Constitution. It is from the Civil War; it is the first line of The Battle Hymn of the Republic. Mine eyes have seen the glory of the coming of the Lord.

That is when our America was born, not with the Revolution and the Founding but with the Civil War and Reconstruction. The values we must carry forward are not those of Thomas Jefferson and the Framers of the Constitution; they are the values of Abraham Lincoln and the Reconstruction Congress. It is time for us to see this. It is time for us to join that march.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- Exclusive: Google Workers Revolt Over $1.2 Billion Contract With Israel

- Jane Fonda Champions Climate Action for Every Generation

- Stop Looking for Your Forever Home

- The Sympathizer Counters 50 Years of Hollywood Vietnam War Narratives

- The Bliss of Seeing the Eclipse From Cleveland

- Hormonal Birth Control Doesn’t Deserve Its Bad Reputation

- The Best TV Shows to Watch on Peacock

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at [email protected]

- Election 2024

- Entertainment

- Newsletters

- Photography

- Personal Finance

- AP Investigations

- AP Buyline Personal Finance

- Press Releases

- Israel-Hamas War

- Russia-Ukraine War

- Global elections

- Asia Pacific

- Latin America

- Middle East

- Election Results

- Delegate Tracker

- AP & Elections

- March Madness

- AP Top 25 Poll

- Movie reviews

- Book reviews

- Personal finance

- Financial Markets

- Business Highlights

- Financial wellness

- Artificial Intelligence

- Social Media

MLK’s dream for America is one of the stars of the 60th anniversary of the 1963 March on Washington

Associated Press democracy, race and ethnicity reporter Gary Fields talks about the 1963 March on Washington and the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.'s “I Have A Dream” speech. (Aug. 23) (AP production by Serkan Gurbuz)

FILE - The Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., addresses marchers during his “I Have a Dream” speech at the Lincoln Memorial in Washington on Aug. 28, 1963. (AP Photo, File)

- Copy Link copied

A visitor looks closely at the original copy of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.'s “I Have a Dream” speech on display at the National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, Friday, Aug. 18, 2023. (AP Photo/Stephanie Scarbrough)

FILE - In this Aug. 28, 1963 file photo, The Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. waves to the crowd at the Lincoln Memorial for his “I Have a Dream” speech during the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom in Washington. (AP Photo, File)

Martin Luther King III, left, and Arndrea Waters King sit for an interview with the Associated Press on Wednesday, Aug. 16, 2023, in Atlanta. (AP Photo/Brynn Anderson)

Civil Rights icon Andrew Young speaks during an interview with The Associated Press on Wednesday, Aug. 16, 2023, in Atlanta. (AP Photo/Brynn Anderson)

Del. Eleanor Holmes Norton, D-D.C., reflects on her time as a young civil rights activist during the 1963 March on Washington, during an Associated Press interview in her office on Capitol Hill in Washington, Wednesday, Aug. 9, 2023. (AP Photo/J. Scott Applewhite)

Aaron Bryant, museum curator of photography, visual culture and contemporary history at the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of African American History and Culture, talks to the Associated Press about the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.'s original speech from the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, Friday, Aug. 18, 2023, in Washington. (AP Photo/Stephanie Scarbrough)

FILE - The Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., delivers his “I Have a Dream” speech to thousands of civil rights supporters gathered in front of the Lincoln Memorial for the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, on Aug. 28, 1963, in Washington. Actor-singer Sammy Davis Jr. can be seen at the far bottom right. (AP Photo, File)

FILE - A framed copy of the original program from the 1963 March on Washington, where the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. delivered his famous “I Have a Dream” speech, is seen on one of the shelves in the Oval Office of the White House in Washington, Oct. 13, 2009, during the Obama administration. (AP Photo/Gerald Herbert, File)

FILE - An arial view of the crowd at the Lincoln Memorial during the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom where the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. gave his famous “I Have a Dream” speech on Aug. 28, 1963, in Washington. (AP Photo/File)

A visitor reads a display about the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom at the National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, Friday, Aug. 18, 2023. (AP Photo/Stephanie Scarbrough)

WASHINGTON (AP) — The last part of the speech took less time to deliver than it takes to boil an egg, but “I Have A Dream” is one of American history’s most famous orations and most inspiring.

On Aug. 28, 1963, from the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, Martin Luther King Jr. began by speaking of poverty, segregation and discrimination and how the United States had reneged on its promise of equality for Black Americans. If anyone remembers that dystopian beginning, they don’t talk about it.

What is etched into people’s memory is the pastoral flourish that marked the last five minutes and presented a soaring vision of what the nation might be and the freedom that equality for all could bring.

As participants prepare to celebrate the 60th anniversary of the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom , that five-minute piece of King’s 16-minute address is the star of that day and today it is the measuring stick of the country’s progress.

How did that memorable moment come to be? Were there other speakers?

King was one of several prominent figures speaking to the many tens of thousands gathered on the National Mall that summer day. Others included A. Phillip Randolph, the march director and founder of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters; Roy Wilkins, the NAACP’s executive secretary; Walter Reuther, president of the United Auto Workers; and John Lewis, a 23-year-old who led the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee and later was a longtime congressman.

There were memorable moments before King spoke.

Eleanor Holmes Norton, who today is the District of Columbia’s veteran nonvoting delegate to Congress, was a SNCC member who helped organize the march. She remembers that march leaders got Lewis to tone down his planned speech because of concern it was too inflammatory. “He had phrases in there about, for example, Sherman marching through Georgia,” Norton said, a reference to Union Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman burning most of Atlanta during the Civil War. “So we had to work with the leaders of the march to change a little bit of that rhetoric.”

King had no peer at the microphone, she said, acknowledging she does not remember now what others may have said. “I’m afraid that Martin Luther King’s speech drowned out everything. It was so eloquent that it kind of surpassed every other speech.”

Did King deliver the speech off the cuff?

The first two-thirds were from written text. The actual speech he used is on loan now at the National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, in the “Defending Freedom, Defining Freedom” gallery of the museum, and shows where he broke script.

King lieutenant Andrew Young said in an interview that he worked with King preparing the text and “none of the things that we remember were in his speech. They didn’t give him but nine minutes and he was trying to write a nine-minute speech.”

A King biographer, Jonathan Eig, said King hit the end of his written remarks and kept going because “he was Martin Luther King” and “it was time to do what he loved to do best, and that’s to give a sermon.”

Had King talked about a dream before?

Although he set the text aside, his deviation was not extemporaneous in the truest since of the word.

Eight months before the March on Washington, King gave an address in Rocky Mount, North Carolina , with similar themes, including a dream.

In June 1963, King spoke in Detroit and opened with the same recognition of Abraham Lincoln and the Emancipation Proclamation before noting that 100 years later, Black people in the U.S. were not free. He talked of the circumstances and sense of urgency but then moved into what he said was a “dream deeply rooted in the American dream.”

The speech mirrored points he would speak of two months later.

Although King used the theme on several occasions “he always made it sound fresh. That’s kind of how he operated,” said Keith Miller, an Arizona State professor who has studied and written extensively about King’s speeches and addresses.

Legend has it that renowned gospel singer Mahalia Jackson prompted King to make the addition?

Whether Jackson was the catalyst or cheered him on after he started, King did not initially intend to speak about a dream and Jackson did say, “Tell them about the dream Martin.” Whatever the close sequence, the two are intertwined now in that moment.

Young said the speech “wasn’t going too well, but everybody was polite listening. But then Mahalia Jackson said, ‘Tell them about the dream Martin’ and he must have heard it or it was in his spirit any way and he took off.”

Arndrea Waters King, King’s daughter-in-law, said Jackson’s suggestion was the moment “that he just really broke out and really started to deliver, if nothing else, what most people remember when they remember the dream.”

Eig, author of “King: A Life,” said he has listened to the master tape made by Motown and she clearly pushes King about the dream, “but it’s only after he has already begun the dream portion of the speech.” Norton, who was nearby and heard Jackson, agrees that was the sequence.

How important was the march to the steps toward equality in the 1960s?

The diversity and size of the crowd and energy were major drivers for the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965, as well as the fair housing law, Norton said. “It would have been very hard for Congress to ignore 250,000 people coming from all over the country, from every member’s district.”

Aaron Bryant, curator of photography, visual culture and contemporary history at the National Museum of African American History and Culture, said the impact was immediate in some ways.

“After the March on Washington, you had some of the organizers, some of the leaders of the march actually meeting with (President) John Kennedy and (Vice President) Lyndon Johnson, to talk more strategically about legislation. So it wasn’t just a dream. It was about a plan and then putting that plan into action,” Bryant said.

Historians and other luminaries of that time said tragedies and atrocities fortified those plans. Those include the bombing of the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama, that killed four girls two weeks after the march; the murders of three civil rights workers in Neshoba County, Mississippi, in 1964; and the televised beatings of civil rights activists on Bloody Sunday in Selma, Alabama, in March 1965.

Why the focus on the final five minutes?

Eig believes that focus on hope and not the harsher reality of the day and the lack of progress is due in part to the predominantly white media that chose the inspirational part of the speech over King calling for accountability.

That focus has done a “disservice to King” and his overall message, Eig said, because “we forget about the challenging part of that speech where he says that there are insufficient funds in the vaults of opportunity in this nation.”

Has the dream been achieved?

Bryant said the answer to that probably varies within generations, but a democracy “is always going to be a work in progress. I think particularly as ideas of citizenship and democracy and definitions among different groups change over the course of time.”

Bryant said history shows the progress that followed the march. “The question is how do we compare where we were then to where we are now?”

In the eyes of King’s older son, Martin Luther King III, “Many of us, and I certainly am one, thought that we would be further.” He referred to the rewriting of history today and the rise in public hate and hostility, often driven by political leaders.

“There used to be civility. You could disagree without being disagreeable,” he said.

MLK’s ‘I Have a Dream’ speech remains etched in American memory as it turns 60

- Show more sharing options

- Copy Link URL Copied!

The last part of the speech took only minutes, but “I Have A Dream” is one of American history’s most famous orations and most inspiring.

On Aug. 28, 1963, from the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, Martin Luther King Jr. began by speaking of poverty, segregation and discrimination and how the United States had reneged on its promise of equality for Black Americans.

But what is etched into people’s memory is the pastoral flourish that marked the last five minutes and presented a soaring vision of what the nation might be and the freedom that equality for all could bring.

As participants prepare to celebrate the 60th anniversary of the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, that five-minute piece of King’s 16-minute address remains the measuring stick of the country’s progress.

How did that moment come to be?

King was one of several prominent figures speaking to the many tens of thousands gathered on the National Mall that summer day. Others included A. Philip Randolph, the march director and founder of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters; Roy Wilkins, the NAACP’s executive secretary; Walter Reuther, president of the United Auto Workers; and John Lewis , a 23-year-old who led the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee and was later a longtime congressman .

There were memorable moments before King spoke.

Eleanor Holmes Norton, who today is the District of Columbia’s veteran nonvoting delegate to Congress, was a SNCC member who helped organize the march. She remembers that march leaders got Lewis to tone down his planned speech because of concern it was too inflammatory.

World & Nation

Visitors to Lincoln Memorial say America has its flaws, but see gains since March on Washington

Nearly 60 years since the March on Washington, fencing and construction workers greet visitors to the Lincoln Memorial, signaling the monument to the nation’s 16th president is a work in progress.

Aug. 25, 2023

“He had phrases in there about, for example, Sherman marching through Georgia,” Norton said, a reference to Union Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman burning most of Atlanta during the Civil War. “So we had to work with the leaders of the march to change a little bit of that rhetoric.”

King had no peer at the microphone, she said, acknowledging she does not remember now what others may have said. “I’m afraid that Martin Luther King’s speech drowned out everything. It was so eloquent that it kind of surpassed every other speech.”

Biden and Harris will meet with King family on 60th anniversary of March on Washington

President Biden and Vice President Kamala Harris will meet with organizers of the 1963 gathering and relatives of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.

From the Archives: Los Angeles Times images of Martin Luther King Jr.

April 3, 2018

Did King deliver the speech off the cuff?

The first two-thirds were from written text. The actual speech he used is on loan now at the National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, in the “Defending Freedom, Defining Freedom” gallery of the museum, and shows where he broke script.

King lieutenant Andrew Young said in an interview that he worked with King preparing the text and “none of the things that we remember were in his speech. They didn’t give him but nine minutes and he was trying to write a nine-minute speech.”

A King biographer, Jonathan Eig, said King hit the end of his written remarks and kept going because “he was Martin Luther King” and “it was time to do what he loved to do best, and that’s to give a sermon.”

Fifty years later, looking back at King’s ‘Dream’ speech

Vernon Watkins was there in 1963, when the March on Washington galvanized him to change his life. ‘Have we reached the goals of that day?’ he wonders now.

Aug. 24, 2013

Had King talked about a dream before?

Although he set the text aside, his deviation was not extemporaneous in the truest since of the word.

Eight months before the March on Washington, King gave an address in Rocky Mount, N.C., with similar themes, including a dream.

In June 1963, King spoke in Detroit and opened with the same recognition of Abraham Lincoln and the Emancipation Proclamation before noting that 100 years later, Black people in the U.S. were not free. He talked of the circumstances and sense of urgency but then moved into what he said was a “dream deeply rooted in the American dream.”

Biden: Americans should ‘pay attention’ to Martin Luther King Jr.’s legacy

President Biden marks the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.’s birthday as the first sitting president to deliver a Sunday sermon at Ebenezer Baptist Church.

Jan. 15, 2023

The speech mirrored points he would speak of two months later.

Although King used the theme on several occasions “he always made it sound fresh. That’s kind of how he operated,” said Keith Miller, an Arizona State professor who has studied and written extensively about King’s speeches and addresses.

Did gospel singer Mahalia Jackson prompt King?

Whether Jackson was the catalyst or cheered him on after he started, King did not initially intend to speak about a dream, and Jackson did say, “Tell them about the dream Martin.” Whatever the sequence, the two are intertwined now in that moment.

Young said the speech “wasn’t going too well, but everybody was polite listening. But then Mahalia Jackson said, ‘Tell them about the dream Martin’ and he must have heard it or it was in his spirit any way and he took off.”

Arndrea Waters King, King’s daughter-in-law, said Jackson’s suggestion was the moment “that he just really broke out and really started to deliver, if nothing else, what most people remember when they remember the dream.”

Eig, author of “King: A Life,” said he has listened to the master tape made by Motown and she clearly pushes King about the dream, “but it’s only after he has already begun the dream portion of the speech.” Norton, who was nearby and heard Jackson, agrees that was the sequence.

How important was the march?

The diversity and size of the crowd and energy were major drivers for the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965 , as well as the fair housing law, Norton said. “It would have been very hard for Congress to ignore 250,000 people coming from all over the country, from every member’s district.”

Aaron Bryant, curator of photography, visual culture and contemporary history at the National Museum of African American History and Culture, said the impact was immediate in some ways.

“After the March on Washington, you had some of the organizers, some of the leaders of the march actually meeting with [President] John Kennedy and [Vice President] Lyndon Johnson, to talk more strategically about legislation. So it wasn’t just a dream. It was about a plan and then putting that plan into action,” Bryant said.

Historians and other luminaries of that time said tragedies and atrocities fortified those plans. Those include the bombing of the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Ala., that killed four girls two weeks after the march; the murders of three civil rights workers in Neshoba County, Miss. in 1964; and the televised beatings of civil rights activists on Bloody Sunday in Selma, Ala. , in March 1965.

Why the focus on the final five minutes?

Eig believes that focus on hope and not the harsher reality of the day and the lack of progress is due in part to the predominantly white media that chose the inspirational part of the speech over King calling for accountability.

That focus has done a “disservice to King” and his overall message, Eig said, because “we forget about the challenging part of that speech where he says that there are insufficient funds in the vaults of opportunity in this nation.”

Is the dream a ‘work in progress’?

Bryant said the answer to that probably varies within generations, but a democracy “is always going to be a work in progress. I think particularly as ideas of citizenship and democracy and definitions among different groups change over the course of time.”

Bryant said history shows the progress that followed the march. “The question is, how do we compare where we were then to where we are now?”

In the eyes of King’s older son, Martin Luther King III, “Many of us, and I certainly am one, thought that we would be further.” He referred to the rewriting of history today and the rise in public hate and hostility, often driven by political leaders.

“There used to be civility,” he said. “You could disagree without being disagreeable.”

More to Read

This teacher will guide you into talking with your dreams. A warning: They will talk back

April 3, 2024

When Martin Luther King Jr. came to L.A., only one white politician was willing to greet him

March 28, 2024

How Mellon chief Elizabeth Alexander (and $500 million) changed the nature of the monuments we revere

March 14, 2024

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

More From the Los Angeles Times

Judge declines to delay Trump’s hush money criminal trial over complaints of pretrial publicity

1 dead and 13 injured after semitrailer intentionally rams into Texas public safety office

April 12, 2024

Wall Street falls sharply to close out its worst week since October

20 years later, Abu Ghraib detainees get their day in U.S. court

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

Black History Month 2024

5 mlk speeches you should know. spoiler: 'i have a dream' isn't on the list.

Scott Neuman

The Rev. Ralph Abernathy (left) shakes hands with the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. in Montgomery, Ala., on March 22, 1956, as a big crowd of supporters cheers for King, who had just been found guilty of leading the Montgomery bus boycott. Gene Herrick/AP hide caption

The Rev. Ralph Abernathy (left) shakes hands with the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. in Montgomery, Ala., on March 22, 1956, as a big crowd of supporters cheers for King, who had just been found guilty of leading the Montgomery bus boycott.

The Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.'s " I Have a Dream " speech, delivered on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial in 1963, is so famous that it often eclipses his other speeches.

King's greatest contribution to the Civil Rights Movement was his oratory, says Jason Miller, an English professor at North Carolina State University who has written extensively on King's speeches.

Black History Month 2024 has begun. Here's this year's theme and other things to know

"King's first biographer was a dear friend of Dr. King's, L.D. Reddick ," Miller says. Reddick once suggested to King that maybe more marching and less speaking was needed to push the cause of civil rights forward. According to Miller, King is said to have responded, "My dear man, you never deny an artist his medium."

Miller says that in his research, he found numerous examples of King reworking and recycling old speeches. "He would rewrite them ... just to change phrasings and rhythms. And so he prepared a great deal, often 19 lines per page on a yellow legal sheet."

Often, King would write notes to himself in the margins: "what tenor and tone to deliver," Miller says.

That phrasing and an understanding of cadence were all important to the success of these speeches, according to Carolyn Calloway-Thomas, director of graduate studies at the Department of African American and African Diaspora Studies at Indiana University.

King's training in the pulpit gave him a strong insight into what moves an audience, she says. "Preachers are performers. They know when to pause. How long to pause. And with what effect. And he certainly was a great user of dramatic pauses."

Here are four of King's speeches that sometimes get overlooked, plus the one he delivered the day before his 1968 assassination. Collectively, they represent historical signposts on the road to civil rights.

" Give Us the Ballot " (May 17, 1957 — Washington, D.C.)

King spoke at the Lincoln Memorial three years to the day after the U.S. Supreme Court's decision in Brown v. Board of Education , which struck down the "separate but equal" doctrine that had allowed segregation in public schools.

But Jim Crow persisted throughout much of the South. The yearlong Montgomery bus boycott , sparked by the arrest of Rosa Parks, had ended only months before King's speech. And the Voting Rights Act of 1965 , which sought to end disenfranchisement of Black voters, was still eight years away.