- Subscribe to journal Subscribe

- Get new issue alerts Get alerts

Secondary Logo

Journal logo.

Colleague's E-mail is Invalid

Your message has been successfully sent to your colleague.

Save my selection

Theory Use and Usefulness in Scientific Advancement

Pickler, Rita H.

Rita H. Pickler, PhD, RN, FAAN, is Editor of Nursing Research .

The Editor has no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Accepted for publication November 20, 2017.

Corresponding author: Rita H. Pickler, PhD, RN, FAAN, The FloAnn Sours Easton Professor of Child and Adolescent Health and Director, PhD & MS in Nursing Science Programs, The Ohio State University College of Nursing, 324 Newton Hall, 1585 Neil Avenue Columbus, OH 43210 (e-mail: [email protected] ).

This issue of Nursing Research is focused on theory in nursing, including how theories historically developed in nursing and how they have evolved over time. Also included in this issue are new thoughts on theory development as well as emergent theoretical ideas. But to what end is theory in the rapidly changing scientific world? Do theories and, particularly, “grand” theories of the sort that many of us of a “certain age” were required to “use” in our own first efforts at research lead to scientific advancement? Is theory useful in today’s seemingly atheoretical age where new scientific “discoveries” are announced daily on social media? Do we need theory to advance science?

Like most scientists, I was taught very early in my training that a theory is a set of interrelated concepts and propositions that explains or predicts events or situations. But I also learned that what “counts” as theory could be many different things depending on who you ask. A theory could be “grand” or macro level, setting forth the phenomena of interest to the discipline using rather abstract concepts. A theory could be “grounded,” addressing contextual explanations of very specific phenomena experienced by select people. Or a theory could be “middle range” or meso level, aimed at integrating empirical research and focused on linking macro and micro level concepts and theories. Clear in all of this was the idea that theories are abstract, varying in the extent to which they are conceptually developed and empirically tested. However, in the end, theory development and testing were deemed to be critically important to advancing science.

Scientific advancement is of course critical to any discipline, and nursing is no different; science is generally thought to advance when theories exist that explain and predict phenomena. A full discussion of how science advances is beyond the scope of this editorial. However, whether you think science advances only when current theories fail to explain the phenomena of interest—resulting in a paradigm shift—or at the other extreme that science advances by a steady accumulation of knowledge that occurs with rigorous and repeated theory testing, theory and scientific advancement would appear to interact. But is theory necessary to science? More importantly, should all science or research within a scientific field be focused on theoretical development and testing. I certainly consider myself a scientist. Am I also a theorist?

The answers to these questions, I believe is, “perhaps.” Indeed, perhaps theory is necessary for scientific advancement. This would particularly be the case if theories for nursing science were focused on understanding, explaining, and predicting those phenomena that are of interest to our discipline and, by extension, to our practice. Our conundrum here is that the phenomena of interest in nursing science and practice are highly varied and—importantly—not agreed upon by the discipline. Many years ago, the historically important grand theories identified broad phenomena of interest—person, environment, health, and nursing. In the ensuing years, these broad phenomena have been challenged, modified, or even discounted as meaningless because of their broadness. And yet, it seems that much of what we study as nurse scientists does fall into one or more of these broad categories of phenomena. That begs a further question about the utility of grand theories: Have grand theories resulted in a clear definition of nursing science? However, from an historical perspective, the grand theories have helped advance nursing science by articulating these phenomena, even if we choose to let the phenomena represent almost anything we wish to study.

Thus, we acknowledge the importance of grand theories to explication of phenomena of interest to nursing science. Regrettably, grand theories do not particularly help us to understand relationships among these broad phenomena. Rather, we need middle range or grounded theories to explicate relationships among concepts embedded within these phenomena in order that scientists can test those proposed relationships. But should all our research be focused on the development and testing of these theories? Perhaps. Certainly it would be hard to document that our science is advancing in this way; many research papers do not name a theory upon which the work is based nor identify a theoretical model being tested. Most rare of all are papers reporting on a theory that has been developed. If theory is necessary for scientific advancement, nurse scientists need to pay greater attention to theory use in their research and their research reports. Certainly if theory has been used to inform research, that use should be clearly articulated. And if theories are tested, then scientists should report on how the theory actually performed.

Rather than clear delineation of theory use, much reported nursing science is a collection of empirical studies on many phenomena of interest. Rarely do we have clear understanding of how or why the results of these studies contribute to scientific advancement within the discipline. Perhaps as a scientific community, we do not think this is necessary. Or perhaps we need to encourage theory development using the empirical evidence we have collected over many years and many studies. I might hazard a guess that many of us who have been studying very specific phenomena over a long period of time have sufficient data accumulated from which theories could be developed and tested. Certainly we need more “basic” research to develop and test theories, particularly those that may lead to interventions designed to improve patient outcomes. Greater rigor and precision in theory development and testing is much needed.

Science advances because of and sometimes in spite of our efforts. Theory should help that advancement, providing explanations of phenomena and their relationships. Using theory in research allows us to refine the definitions and scope of the discipline of nursing. Theories may change and the way that they are interpreted may change, but these changes and interpretations based on observations are most likely to result in advancements because they occur within the context of theory. In nursing science, given the broad scope of our interests, we are likely to need many theories to describe, explain, and predict the complexity in the relationships among those concepts.

Theories have long been thought to be the foundations for furthering scientific knowledge and for putting the information gathered through empirical research into practice. Indeed, perhaps more than ever, clear use of theory in research may be even more important to further advance nursing science. Thus, the question is not: should we use theory in our scientific work? The question is: are we making explicit the theories we are using? The papers collected in this issue will hopefully advance science by reminding us of important past theoretical work and providing guidance for the way forward. To each of us engaged in nursing science, our challenge is to carefully consider the function of theory in our own work and to further advance nursing science by making theory use more evident in our research reports.

nursing research; nursing science; nursing theory; scientific advancement

- + Favorites

- View in Gallery

Readers Of this Article Also Read

Key issues in nursing theory: developments, challenges, and future directions, the fundamentals of care framework as a point-of-care nursing theory.

ANA Nursing Resources Hub

Search Resources Hub

What Is Nursing Theory?

3 min read • July, 05 2023

Nursing theories provide a foundation for clinical decision-making. These theoretical models in nursing shape nursing research and create conceptual blueprints, ultimately determining the how and why that drive nurse-patient interactions.

Nurse researchers and scholars naturally develop these theories with the input and influence of other professionals in the field.

Why Is Nursing Theory Important?

Nursing theory concepts are essential to the present and future of the profession. The first nursing theory — Florence Nightingale's Environmental Theory — dates back to the 19th century. Nightingale identified a clear link between a patient's environment (such as clean water, sunlight, and fresh air) and their ability to recover. Her discoveries remain relevant for today's practitioners. As health care continues to develop, new types of nursing theories may evolve to reflect new medicines and technologies.

Education and training showcase the importance of nursing theory. Nurse researchers and scholars share established ideas to ensure industry-wide best practices and patient outcomes, and nurse educators shape their curricula based on this research. When nurses learn these theories, they gain the data to explain the reasoning behind their clinical decision-making. Nurses position themselves to provide the best care by familiarizing themselves with time-tested theories. Recognizing their place in the history of nursing provides a validating sense of belonging within the greater health care system. That helps patients and other health care providers better understand and appreciate nurses’ contributions.

Types of Nursing Theories

Nursing theories fall under three tiers: grand nursing, middle-range, and practical-level theories . Inherent to each is the nursing metaparadigm , which focuses on four components:

- The person (sometimes referred to as the patient or client)

- Their environment (physical and emotional)

- Their health while receiving treatment

- The nurse's approach and attributes

Each of these four elements factors into a specific nursing theory.

Grand Nursing Theories

Grand theories are the broadest of the three theory classifications. They offer wide-ranging perspectives focused on abstract concepts, often stemming from a nurse theorist’s lived experiences or nursing philosophies. Grand nursing theories help to guide research in the field, with studies aiming to explore proposed ideas further.

Hildegard Peplau's Theory of Interpersonal Relations is an excellent example of a grand nursing theory. The theory suggests that for a nurse-patient relationship to be successful, it must go through three phases: orientation, working, and termination. This grand theory is broad in scope and widely applicable to different environments.

Middle-Range Nursing Theories

As the name suggests, middle-range theories lie somewhere between the sweeping scope of grand nursing and a minute focus on practice-level theories. These theories are often phenomena-driven, attempting to explain or predict certain trends in clinical practice. They’re also testable or verifiable through research.

Nurse researchers have applied the concept of Dorothea E. Orem's Self-Care Deficit Theory to patients dealing with various conditions, ranging from hepatitis to diabetes. This grand theory suggests that patients recover most effectively if they actively and autonomously perform self-care.

Practice-Level Nursing Theories

Practice-level theories are more specific to a patient’s needs or goals. These theories guide the treatment of health conditions and situations requiring nursing intervention. Because they’re so specific, these types of nursing theories directly impact daily practices more than other theory classifications. From patient education to practicing active compassion, bedside nurses use these theories in their everyday responsibilities.

Nursing Theory in Practice

Theory and practice inform each other. Nursing theories determine research that shapes policies and procedures. Nurses constantly apply theories to patient interactions, consciously or due to training. For example, a nurse who aims to provide culturally competent care — through a commitment to ongoing education and open-mindedness — puts Madeleine Leininger's Transcultural Nursing Theory into effect. Because nursing is multifaceted, nurses can draw from multiple theories to ensure the best course of action for a patient.

Applying theory in nursing practice develops nursing knowledge and supports evidence-based practice. A nursing theoretical framework is essential to understand decision-making processes and to promote quality patient care.

Images sourced from Getty Images

Related Resources

Item(s) added to cart

Nursing Theories and Theorists: The Definitive Guide for Nurses

In this guide for nursing theories and nursing theorists , we aim to help you understand what comprises a nursing theory and its importance, purpose, history, types, or classifications, and give you an overview through summaries of selected nursing theories.

Table of Contents

- What are Nursing Theories?

Defining Terms

History of nursing theories, environment, definitions, relational statements, assumptions, why are nursing theories important, in academic discipline, in research, in the profession, grand nursing theories, middle-range nursing theories, practice-level nursing theories, factor-isolating theory, explanatory theory, prescriptive theories, other ways of classifying nursing theories, florence nightingale, hildegard e. peplau, virginia henderson, faye glenn abdellah, ernestine wiedenbach, lydia e. hall, joyce travelbee, kathryn e. barnard, evelyn adam, nancy roper, winifred logan, and alison j. tierney, ida jean orlando, jean watson.

- Marilyn Anne Ray

Patricia Benner

Kari martinsen, katie eriksson, myra estrin levine, martha e. rogers, dorothea e. orem, imogene m. king, betty neuman, sister callista roy, dorothy e. johnson, anne boykin and savina o. schoenhofer, afaf ibrahim meleis, nola j. pender, madeleine m. leininger, margaret a. newman, rosemarie rizzo parse, helen c. erickson, evelyn m. tomlin, and mary ann p. swain, gladys l. husted and james h. husted, ramona t. mercer, merle h. mishel, pamela g. reed, carolyn l. wiener and marylin j. dodd, georgene gaskill eakes, mary lermann burke, and margaret a. hainsworth, phil barker, katharine kolcaba, cheryl tatano beck, kristen m. swanson, cornelia m. ruland and shirley m. moore, wanda de aguiar horta, recommended resources, what are nursing theories.

Nursing theories are organized bodies of knowledge to define what nursing is, what nurses do, and why they do it. Nursing theories provide a way to define nursing as a unique discipline that is separate from other disciplines (e.g., medicine). It is a framework of concepts and purposes intended to guide nursing practice at a more concrete and specific level.

Nursing, as a profession, is committed to recognizing its own unparalleled body of knowledge vital to nursing practice—nursing science. To distinguish this foundation of knowledge, nurses need to identify, develop, and understand concepts and theories in line with nursing. As a science, nursing is based on the theory of what nursing is, what nurses do, and why. Nursing is a unique discipline and is separate from medicine. It has its own body of knowledge on which delivery of care is based.

The development of nursing theory demands an understanding of selected terminologies, definitions, and assumptions.

- Philosophy. These are beliefs and values that define a way of thinking and are generally known and understood by a group or discipline.

- Theory . A belief, policy, or procedure proposed or followed as the basis of action. It refers to a logical group of general propositions used as principles of explanation. Theories are also used to describe, predict, or control phenomena.

- Concept. Concepts are often called the building blocks of theories. They are primarily the vehicles of thought that involve images.

- Models. Models are representations of the interaction among and between the concepts showing patterns. They present an overview of the theory’s thinking and may demonstrate how theory can be introduced into practice.

- Conceptual framework. A conceptual framework is a group of related ideas, statements, or concepts. It is often used interchangeably with the conceptual model and with grand theories .

- Proposition. Propositions are statements that describe the relationship between the concepts.

- Domain . The domain is the perspective or territory of a profession or discipline.

- Process. Processes are organized steps, changes, or functions intended to bring about the desired result.

- Paradigm. A paradigm refers to a pattern of shared understanding and assumptions about reality and the world, worldview, or widely accepted value system.

- Metaparadigm. A metaparadigm is the most general statement of discipline and functions as a framework in which the more restricted structures of conceptual models develop. Much of the theoretical work in nursing focused on articulating relationships among four major concepts: person, environment, health, and nursing.

The first nursing theories appeared in the late 1800s when a strong emphasis was placed on nursing education.

- In 1860, Florence Nightingale defined nursing in her “ Environmental Theory ” as “the act of utilizing the patient’s environment to assist him in his recovery.”

- In the 1950s, there is a consensus among nursing scholars that nursing needed to validate itself through the production of its own scientifically tested body of knowledge.

- In 1952, Hildegard Peplau introduced her Theory of Interpersonal Relations that emphasizes the nurse -client relationship as the foundation of nursing practice.

- In 1955, Virginia Henderson conceptualized the nurse’s role as assisting sick or healthy individuals to gain independence in meeting 14 fundamental needs. Thus her Nursing Need Theory was developed.

- In 1960, Faye Abdellah published her work “Typology of 21 Nursing Problems,” which shifted the focus of nursing from a disease-centered approach to a patient-centered approach.

- In 1962, Ida Jean Orlando emphasized the reciprocal relationship between patient and nurse and viewed nursing’s professional function as finding out and meeting the patient’s immediate need for help.

- In 1968, Dorothy Johnson pioneered the Behavioral System Model and upheld the fostering of efficient and effective behavioral functioning in the patient to prevent illness.

- In 1970, Martha Rogers viewed nursing as both a science and an art as it provides a way to view the unitary human being, who is integral with the universe.

- In 1971, Dorothea Orem stated in her theory that nursing care is required if the client is unable to fulfill biological, psychological, developmental, or social needs.

- In 1971, Imogene King ‘s Theory of Goal attainment stated that the nurse is considered part of the patient’s environment and the nurse-patient relationship is for meeting goals towards good health.

- In 1972, Betty Neuman , in her theory, states that many needs exist, and each may disrupt client balance or stability. Stress reduction is the goal of the system model of nursing practice.

- In 1979, Sr. Callista Roy viewed the individual as a set of interrelated systems that maintain the balance between these various stimuli.

- In 1979, Jean Watson developed the philosophy of caring, highlighted humanistic aspects of nursing as they intertwine with scientific knowledge and nursing practice.

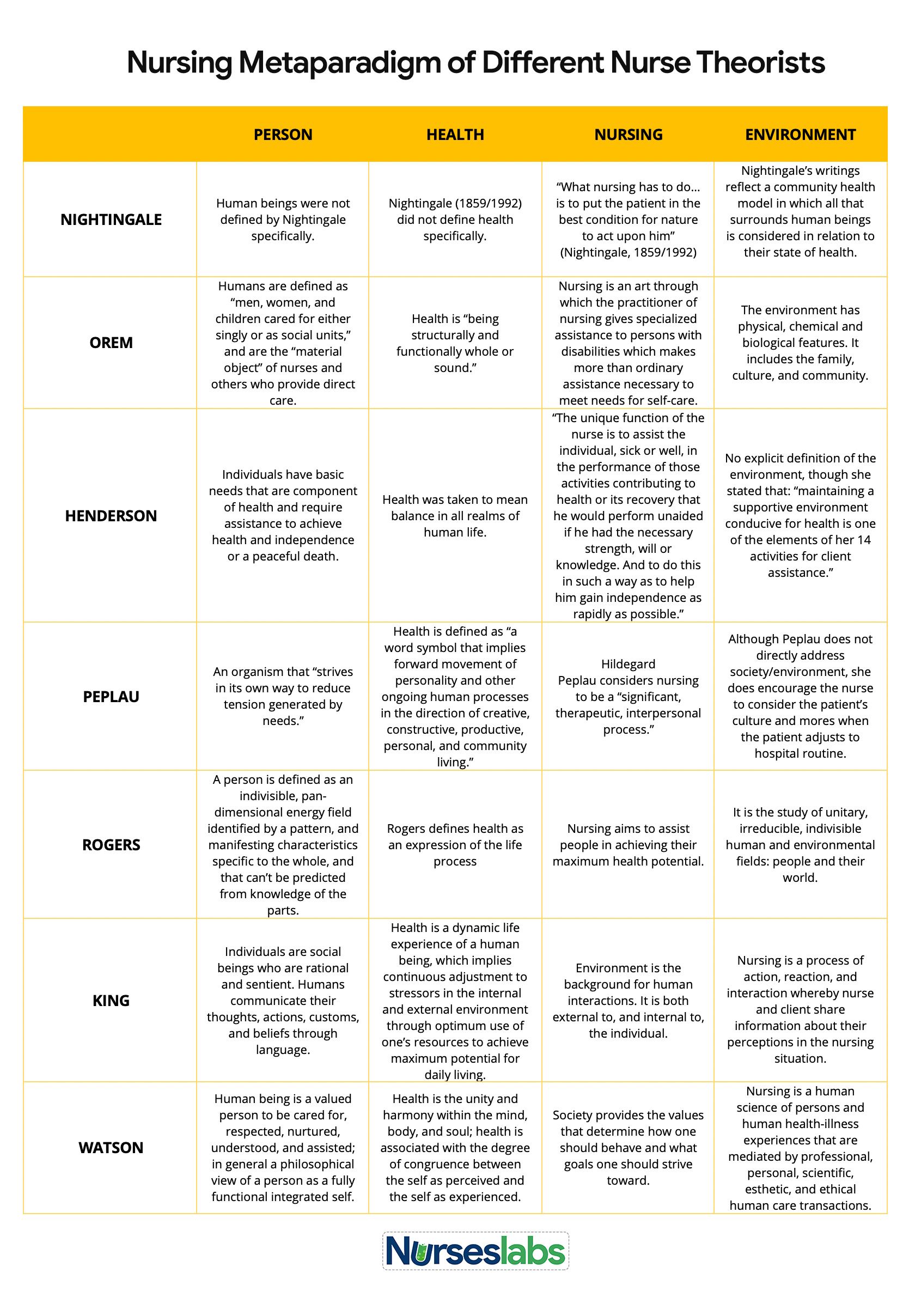

The Nursing Metaparadigm

Four major concepts are frequently interrelated and fundamental to nursing theory: person, environment, health, and nursing. These four are collectively referred to as metaparadigm for nursing .

Person (also referred to as Client or Human Beings) is the recipient of nursing care and may include individuals, patients, groups, families, and communities.

Environment (or situation) is defined as the internal and external surroundings that affect the client. It includes all positive or negative conditions that affect the patient, the physical environment, such as families, friends, and significant others, and the setting for where they go for their healthcare.

Health is defined as the degree of wellness or well-being that the client experiences. It may have different meanings for each patient, the clinical setting, and the health care provider.

The nurse’s attributes, characteristics, and actions provide care on behalf of or in conjunction with the client. There are numerous definitions of nursing, though nursing scholars may have difficulty agreeing on its exact definition. The ultimate goal of nursing theories is to improve patient care .

You’ll find that these four concepts are used frequently and defined differently throughout different nursing theories. Each nurse theorist’s definition varies by their orientation, nursing experience , and different factors that affect the theorist’s nursing view. The person is the main focus, but how each theorist defines the nursing metaparadigm gives a unique take specific to a particular theory. To give you an example, below are the different definitions of various theorists on the nursing metaparadigm:

Components of Nursing Theories

For a theory to be a theory, it has to contain concepts, definitions, relational statements, and assumptions that explain a phenomenon. It should also explain how these components relate to each other.

A term given to describe an idea or response about an event, a situation, a process, a group of events, or a group of situations. Phenomena may be temporary or permanent. Nursing theories focus on the phenomena of nursing.

Interrelated concepts define a theory. Concepts are used to help describe or label a phenomenon. They are words or phrases that identify, define, and establish structure and boundaries for ideas generated about a particular phenomenon. Concepts may be abstract or concrete.

- Abstract Concepts . Defined as mentally constructed independently of a specific time or place.

- Concrete Concepts . Are directly experienced and related to a particular time or place.

Definitions are used to convey the general meaning of the concepts of the theory. Definitions can be theoretical or operational.

- Theoretical Definitions . Define a particular concept based on the theorist’s perspective.

- Operational Definitions . States how concepts are measured.

Relational statements define the relationships between two or more concepts. They are the chains that link concepts to one another.

Assumptions are accepted as truths and are based on values and beliefs. These statements explain the nature of concepts, definitions, purpose, relationships, and structure of a theory.

Nursing theories are the basis of nursing practice today. In many cases, nursing theory guides knowledge development and directs education, research, and practice. Historically, nursing was not recognized as an academic discipline or as a profession we view today. Before nursing theories were developed, nursing was considered to be a task-oriented occupation. The training and function of nurses were under the direction and control of the medical profession. Let’s take a look at the importance of nursing theory and its significance to nursing practice:

- Nursing theories help recognize what should set the foundation of practice by explicitly describing nursing.

- By defining nursing, a nursing theory also helps nurses understand their purpose and role in the healthcare setting.

- Theories serve as a rationale or scientific reasons for nursing interventions and give nurses the knowledge base necessary for acting and responding appropriately in nursing care situations.

- Nursing theories provide the foundations of nursing practice, generate further knowledge, and indicate which direction nursing should develop in the future (Brown, 1964).

- By providing nurses a sense of identity, nursing theory can help patients, managers, and other healthcare professionals to acknowledge and understand the unique contribution that nurses make to the healthcare service (Draper, 1990).

- Nursing theories prepare the nurses to reflect on the assumptions and question the nursing values, thus further defining nursing and increasing the knowledge base.

- Nursing theories aim to define, predict, and demonstrate nursing phenomenon (Chinn and Jacobs, 1978).

- It can be regarded as an attempt by the nursing profession to maintain and preserve its professional limits and boundaries.

- Nursing theories can help guide research and informing evidence-based practice.

- Provide a common language and terminology for nurses to use in communication and practice.

- Serves as a basis for the development of nursing education and training programs.

- In many cases, nursing theories guide knowledge development and directs education, research, and practice, although each influences the others. (Fitzpatrick and Whall, 2005).

Purposes of Nursing Theories

The primary purpose of theory in nursing is to improve practice by positively influencing the health and quality of life of patients. Nursing theories are essential for the development and advancement of the nursing profession. Nursing theories are also developed to define and describe nursing care, guide nursing practice, and provide a basis for clinical decision-making . In the past, the accomplishments of nursing led to the recognition of nursing in an academic discipline, research, and profession.

Much of the earlier nursing programs identified the major concepts in one or two nursing models, organized the concepts, and build an entire nursing curriculum around the created framework. These models’ unique language was typically introduced into program objectives, course objectives, course descriptions, and clinical performance criteria. The purpose was to explain the fundamental implications of the profession and enhance the profession’s status.

The development of theory is fundamental to the research process, where it is necessary to use theory as a framework to provide perspective and guidance to the research study. Theory can also be used to guide the research process by creating and testing phenomena of interest. To improve the nursing profession’s ability to meet societal duties and responsibilities, there needs to be a continuous reciprocal and cyclical connection with theory, practice, and research. This will help connect the perceived “gap” between theory and practice and promote the theory-guided practice.

Clinical practice generates research questions and knowledge for theory. In a clinical setting, its primary contribution has been the facilitation of reflecting, questioning, and thinking about what nurses do. Because nurses and nursing practice are often subordinate to powerful institutional forces and traditions, introducing any framework that encourages nurses to reflect on, question, and think about what they do provide an invaluable service.

Classification of Nursing Theories

There are different ways to categorize nursing theories. They are classified depending on their function, levels of abstraction, or goal orientation.

By Abstraction

There are three major categories when classifying nursing theories based on their level of abstraction: grand theory, middle-range theory, and practice-level theory.

- Grand theories are abstract, broad in scope, and complex, therefore requiring further research for clarification.

- Grand nursing theories do not guide specific nursing interventions but rather provide a general framework and nursing ideas.

- Grand nursing theorists develop their works based on their own experiences and their time, explaining why there is so much variation among theories.

- Address the nursing metaparadigm components of person, nursing, health, and environment.

- More limited in scope (compared to grand theories) and present concepts and propositions at a lower level of abstraction. They address a specific phenomenon in nursing.

- Due to the difficulty of testing grand theories, nursing scholars proposed using this level of theory.

- Most middle-range theories are based on a grand theorist’s works, but they can be conceived from research, nursing practice, or the theories of other disciplines.

- Practice nursing theories are situation-specific theories that are narrow in scope and focuses on a specific patient population at a specific time.

- Practice-level nursing theories provide frameworks for nursing interventions and suggest outcomes or the effect of nursing practice.

- Theories developed at this level have a more direct effect on nursing practice than more abstract theories.

- These theories are interrelated with concepts from middle-range theories or grand theories.

By Goal Orientation

Theories can also be classified based on their goals. They can be descriptive or prescriptive .

Descriptive Theories

- Descriptive theories are the first level of theory development. They describe the phenomena and identify its properties and components in which it occurs.

- Descriptive theories are not action-oriented or attempt to produce or change a situation.

- There are two types of descriptive theories: factor-isolating theory and explanatory theory .

- Also known as category-formulating or labeling theory.

- Theories under this category describe the properties and dimensions of phenomena.

- Explanatory theories describe and explain the nature of relationships of certain phenomena to other phenomena.

- Address the nursing interventions for a phenomenon, guide practice change, and predict consequences.

- Includes propositions that call for change.

- In nursing, prescriptive theories are used to anticipate the outcomes of nursing interventions.

Classification According to Meleis

Afaf Ibrahim Meleis (2011), in her book Theoretical Nursing: Development and Progress , organizes the major nurse theories and models using the following headings: needs theories, interaction theories, and outcome theories. These categories indicate the basic philosophical underpinnings of the theories.

- Needs-Based Theories. The needs theorists were the first group of nurses who thought of giving nursing care a conceptual order. Theories under this group are based on helping individuals to fulfill their physical and mental needs. Theories of Orem, Henderson, and Abdella are categorized under this group. Need theories are criticized for relying too much on the medical model of health and placing the patient in an overtly dependent position.

- Interaction Theories. These theories emphasized nursing on the establishment and maintenance of relationships. They highlighted the impact of nursing on patients and how they interact with the environment, people, and situations. Theories of King, Orlando, and Travelbee are grouped under this category.

- Outcome Theories . These theories describe the nurse as controlling and directing patient care using their knowledge of the human physiological and behavioral systems. The nursing theories of Johnson , Levine , Rogers , and Roy belong to this group.

Classification According to Alligood

In her book, Nursing Theorists and Their Work, Raile Alligood (2017) categorized nursing theories into four headings: nursing philosophy, nursing conceptual models, nursing theories and grand theories, and middle-range nursing theories.

- Nursing Philosophy . It is the most abstract type and sets forth the meaning of nursing phenomena through analysis, reasoning, and logical presentation. Works of Nightingale, Watson, Ray, and Benner are categorized under this group.

- Nursing Conceptual Models . These are comprehensive nursing theories that are regarded by some as pioneers in nursing. These theories address the nursing metaparadigm and explain the relationship between them. Conceptual models of Levine, Rogers, Roy, King, and Orem are under this group.

- Grand Nursing Theories. Are works derived from nursing philosophies, conceptual models, and other grand theories that are generally not as specific as middle-range theories. Works of Levine, Rogers, Orem, and King are some of the theories under this category.

- Middle-Range Theories. Are precise and answer specific nursing practice questions . They address the specifics of nursing situations within the model’s perspective or theory from which they are derived. Examples of Middle-Range theories are that of Mercer, Reed, Mishel, and Barker.

List of Nursing Theories and Theorists

You’ve learned from the previous sections the definition of nursing theory, its significance in nursing, and its purpose in generating a nursing knowledge base. This section will give you an overview and summary of the various published works in nursing theory (in chronological order). Deep dive into learning about the theory by clicking on the links provided for their biography and comprehensive review of their work.

See Also: Florence Nightingale: Environmental Theory and Biography

- Founder of Modern Nursing and Pioneer of the Environmental Theory.

- Defined Nursing as “the act of utilizing the environment of the patient to assist him in his recovery.”

- Stated that nursing “ought to signify the proper use of fresh air, light, warmth, cleanliness, quiet, and the proper selection and administration of diet – all at the least expense of vital power to the patient.”

- Identified five (5) environmental factors: fresh air, pure water, efficient drainage, cleanliness or sanitation, and light or direct sunlight.

See Also: Hildegard Peplau: Interpersonal Relations Theory

- Pioneered the Theory of Interpersonal Relations

- Peplau’s theory defined Nursing as “An interpersonal process of therapeutic interactions between an individual who is sick or in need of health services and a nurse specially educated to recognize, respond to the need for help.”

- Her work is influenced by Henry Stack Sullivan, Percival Symonds, Abraham Maslow , and Neal Elgar Miller.

- It helps nurses and healthcare providers develop more therapeutic interventions in the clinical setting.

See Also: Virginia Henderson: Nursing Need Theory

- Developed the Nursing Need Theory

- Focuses on the importance of increasing the patient’s independence to hasten their progress in the hospital.

- Emphasizes the basic human needs and how nurses can assist in meeting those needs.

- “The nurse is expected to carry out a physician’s therapeutic plan, but individualized care is the result of the nurse’s creativity in planning for care.”

See Also: Faye Glenn Abdellah: 21 Nursing Problems Theory

- Developed the 21 Nursing Problems Theory

- “Nursing is based on an art and science that molds the attitudes, intellectual competencies, and technical skills of the individual nurse into the desire and ability to help people, sick or well, cope with their health needs.”

- Changed the focus of nursing from disease-centered to patient-centered and began to include families and the elderly in nursing care.

- The nursing model is intended to guide care in hospital institutions but can also be applied to community health nursing, as well.

- Developed The Helping Art of Clinical Nursing conceptual model.

- Definition of nursing reflects on nurse-midwife experience as “People may differ in their concept of nursing, but few would disagree that nursing is nurturing or caring for someone in a motherly fashion.”

- Guides the nurse action in the art of nursing and specified four elements of clinical nursing: philosophy, purpose, practice, and art.

- Clinical nursing is focused on meeting the patient’s perceived need for help in a vision of nursing that indicates considerable importance on the art of nursing.

See Also: Lydia Hall: Care, Cure, Core Theory

- Developed the Care, Cure, Core Theory is also known as the “ Three Cs of Lydia Hall . “

- Hall defined Nursing as the “participation in care, core and cure aspects of patient care , where CARE is the sole function of nurses, whereas the CORE and CURE are shared with other members of the health team.”

- The major purpose of care is to achieve an interpersonal relationship with the individual to facilitate the development of the core.

- The “care” circle defines a professional nurse’s primary role, such as providing bodily care for the patient. The “core” is the patient receiving nursing care. The “cure” is the aspect of nursing that involves the administration of medications and treatments.

- States in her Human-to-Human Relationship Model that the purpose of nursing was to help and support an individual, family, or community to prevent or cope with the struggles of illness and suffering and, if necessary, to find significance in these occurrences, with the ultimate goal being the presence of hope.

- Nursing was accomplished through human-to-human relationships.

- Extended the interpersonal relationship theories of Peplau and Orlando.

- Developed the Child Health Assessment Model .

- Concerns improving the health of infants and their families.

- Her findings on parent-child interaction as an important predictor of cognitive development helped shape public policy.

- She is the founder of the Nursing Child Assessment Satellite Training Project (NCAST), which produces and develops research-based products, assessment , and training programs to teach professionals, parents, and other caregivers the skills to provide nurturing environments for young children.

- Borrows from psychology and human development and focuses on mother-infant interaction with the environment.

- Contributed a close link to practice that has modified the way health care providers assess children in light of the parent-child relationship.

- Focuses on the development of models and theories on the concept of nursing.

- Includes the profession’s goal, the beneficiary of the professional service, the role of the professional, the source of the beneficiary’s difficulty, the intervention of the professional, and the consequences.

- A good example of using a unique basis of nursing for further expansion.

- A Model for Nursing Based on a Model of Living

- Logan produced a simple theory, “which actually helped bedside nurses.”

- The trio collaborated in the fourth edition of The Elements of Nursing: A Model for Nursing Based on a Model of Living and prepared a monograph entitled The Roper-Logan-Tierney Model of Nursing: Based on Activities of Daily Living.

- Includes maintaining a safe environment, communicating, breathing, eating and drinking, eliminating, personal cleansing and dressing , controlling body temperature, mobilizing, working and playing, expressing sexuality, sleeping , and dying .

See Also: Ida Jean Orlando: Nursing Process Theory

- She developed the Nursing Process Theory.

- “Patients have their own meanings and interpretations of situations, and therefore nurses must validate their inferences and analyses with patients before drawing conclusions.”

- Allows nurses to formulate an effective nursing care plan that can also be easily adapted when and if any complexity comes up with the patient.

- According to her, persons become patients requiring nursing care when they have needs for help that cannot be met independently because of their physical limitations, negative reactions to an environment, or experience that prevents them from communicating their needs.

- The role of the nurse is to find out and meet the patient’s immediate needs for help.

See Also: Jean Watson: Theory of Human Caring

- She pioneered the Philosophy and Theory of Transpersonal Caring .

- “Nursing is concerned with promoting health, preventing illness, caring for the sick, and restoring health.”

- Mainly concerns with how nurses care for their patients and how that caring progresses into better plans to promote health and wellness, prevent illness and restore health.

- Focuses on health promotion , as well as the treatment of diseases.

- Caring is central to nursing practice and promotes health better than a simple medical cure.

Marilyn Anne Ray

- Developed the Theory of Bureaucratic Caring

- “Improved patient safety , infection control, reduction in medication errors , and overall quality of care in complex bureaucratic health care systems cannot occur without knowledge and understanding of complex organizations, such as the political and economic systems, and spiritual-ethical caring, compassion and right action for all patients and professionals.”

- Challenges participants in nursing to think beyond their usual frame of reference and envision the world holistically while considering the universe as a hologram.

- Presents a different view of how health care organizations and nursing phenomena interrelate as wholes and parts in the system.

- Caring, Clinical Wisdom, and Ethics in Nursing Practice

- “The nurse-patient relationship is not a uniform, professionalized blueprint but rather a kaleidoscope of intimacy and distance in some of the most dramatic, poignant, and mundane moments of life.”

- Attempts to assert and reestablish nurses’ caring practices when nurses are rewarded more for efficiency, technical skills, and measurable outcomes.

- States that caring practices are instilled with knowledge and skill regarding everyday human needs.

- Philosophy of Caring

- “Nursing is founded on caring for life, on neighborly love, […]At the same time, the nurse must be professionally educated.”

- Human beings are created and are beings for whom we may have administrative responsibility.

- Caring, solidarity, and moral practice are unavoidable realities.

- Theory of Carative Caring

- “Caritative nursing means that we take ‘caritas’ into use when caring for the human being in health and suffering […] Caritative caring is a manifestation of the love that ‘just exists’ […] Caring communion, true caring, occurs when the one caring in a spirit of caritas alleviates the suffering of the patient.”

- The ultimate goal of caring is to lighten suffering and serve life and health.

- Inspired many in the Nordic countries and used it as the basis of research, education, and clinical practice.

See Also: Myra Estrin Levine: Conservation Model for Nursing

- According to the Conservation Model , “Nursing is human interaction.”

- Provides a framework within which to teach beginning nursing students.

- Logically congruent, externally and internally consistent, has breadth and depth, and is understood, with few exceptions, by professionals and consumers of health care.

See Also: Martha Rogers: Theory of Unitary Human Beings

- In Roger’s Theory of Human Beings , she defined Nursing as “an art and science that is humanistic and humanitarian.

- The Science of Unitary Human Beings contains two dimensions: the science of nursing, which is the knowledge specific to the field of nursing that comes from scientific research; and the art of nursing, which involves using nursing creatively to help better the lives of the patient.

- A patient can’t be separated from his or her environment when addressing health and treatment.

See Also: Dorothea E. Orem: Self-Care Theory

- In her Self-Care Theory , she defined Nursing as “The act of assisting others in the provision and management of self-care to maintain or improve human functioning at the home level of effectiveness.”

- Focuses on each individual’s ability to perform self-care .

- Composed of three interrelated theories: (1) the theory of self-care , (2) the self-care deficit theory, and (3) the theory of nursing systems, which is further classified into wholly compensatory, partially compensatory, and supportive-educative.

See Also: Imogene M. King: Theory of Goal Attainment

- Conceptual System and Middle-Range Theory of Goal Attainment

- “Nursing is a process of action, reaction and interaction by which nurse and client share information about their perception in a nursing situation” and “a process of human interactions between nurse and client whereby each perceives the other and the situation, and through communication , they set goals, explore means, and agree on means to achieve goals.”

- Focuses on this process to guide and direct nurses in the nurse-patient relationship, going hand-in-hand with their patients to meet good health goals.

- Explains that the nurse and patient go hand-in-hand in communicating information, set goals together, and then take actions to achieve those goals.

See Also: Betty Neuman: Neuman’s Systems Model

- In Neuman’s System Model , she defined nursing as a “unique profession in that is concerned with all of the variables affecting an individual’s response to stress.”

- The focus is on the client as a system (which may be an individual, family, group, or community) and on the client’s responses to stressors.

- The client system includes five variables (physiological, psychological, sociocultural, developmental, and spiritual). It is conceptualized as an inner core (basic energy resources) surrounded by concentric circles that include lines of resistance, a normal defense line, and a flexible line of defense.

See Also: Sister Callista Roy: Adaptation Model of Nursing

- In Adaptation Model , Roy defined nursing as a “health care profession that focuses on human life processes and patterns and emphasizes the promotion of health for individuals, families, groups, and society as a whole.”

- Views the individual as a set of interrelated systems that strives to maintain a balance between various stimuli.

- Inspired the development of many middle-range nursing theories and adaptation instruments.

See Also: Dorothy E. Johnson: Behavioral Systems Model

- The Behavioral System Model defined Nursing as “an external regulatory force that acts to preserve the organization and integrate the patients’ behaviors at an optimum level under those conditions in which the behavior constitutes a threat to the physical or social health or in which illness is found.”

- Advocates to foster efficient and effective behavioral functioning in the patient to prevent illness and stresses the importance of research-based knowledge about the effect of nursing care on patients.

- Describes the person as a behavioral system with seven subsystems: the achievement, attachment-affiliative, aggressive-protective, dependency, ingestive, eliminative, and sexual subsystems.

- The Theory of Nursing as Caring: A Model for Transforming Practice

- Nursing is an “exquisitely interwoven” unity of aspects of the discipline and profession of nursing.

- Nursing’s focus and aim as a discipline of knowledge and a professional service are “nurturing persons living to care and growing in caring.”

- Caring in nursing is “an altruistic, active expression of love, and is the intentional and embodied recognition of value and connectedness.”

- Transitions Theory

- It began with observations of experiences faced as people deal with changes related to health, well-being, and the ability to care for themselves.

- Types of transitions include developmental, health and illness, situational, and organizational.

- Acknowledges the role of nurses as they help people go through health/illness and life transitions.

- Focuses on assisting nurses in facilitating patients’, families’, and communities’ healthy transitions.

See Also: Nola Pender: Health Promotion Model

- Health Promotion Model

- Describes the interaction between the nurse and the consumer while considering the role of the health promotion environment.

- It focuses on three areas: individual characteristics and experiences, behavior-specific cognitions and affect, and behavioral outcomes.

- Describes the multidimensional nature of persons as they interact within their environment to pursue health.

See Also: Madeleine M. Leininger: Transcultural Nursing Theory

- Culture Care Theory of Diversity and Universality

- Defined transcultural nursing as “a substantive area of study and practice focused on comparative cultural care (caring) values, beliefs, and practices of individuals or groups of similar or different cultures to provide culture-specific and universal nursing care practices in promoting health or well-being or to help people to face unfavorable human conditions, illness, or death in culturally meaningful ways.”

- Involves learning and understanding various cultures regarding nursing and health-illness caring practices, beliefs, and values to implement significant and efficient nursing care services to people according to their cultural values and health-illness context.

- It focuses on the fact that various cultures have different and unique caring behaviors and different health and illness values, beliefs, and patterns of behaviors.

- Health as Expanding Consciousness

- “Nursing is the process of recognizing the patient in relation to the environment, and it is the process of the understanding of consciousness.”

- “The theory of health as expanding consciousness was stimulated by concern for those for whom health as the absence of disease or disability is not possible . . . “

- Nursing is regarded as a connection between the nurse and patient, and both grow in the sense of higher levels of consciousness.

- Human Becoming Theory

- “Nursing is a science, and the performing art of nursing is practiced in relationships with persons (individuals, groups, and communities) in their processes of becoming.”

- Explains that a person is more than the sum of the parts, the environment, and the person is inseparable and that nursing is a human science and art that uses an abstract body of knowledge to help people.

- It centered around three themes: meaning, rhythmicity, and transcendence.

- Modeling and Role-Modeling

- “Nursing is the holistic helping of persons with their self-care activities in relation to their health . . . The goal is to achieve a state of perceived optimum health and contentment.”

- Modeling is a process that allows nurses to understand the unique perspective of a client and learn to appreciate its importance.

- Role-modeling occurs when the nurse plans and implements interventions that are unique for the client.

- Created the Symphonological Bioethical Theory

- “Symphonology (from ‘ symphonia ,’ a Greek word meaning agreement) is a system of ethics based on the terms and preconditions of an agreement.”

- Nursing cannot occur without both nurse and patient. “A nurse takes no actions that are not interactions.”

- Founded on the singular concept of human rights, the essential agreement of non-aggression among rational people forms the foundation of all human interaction.

- Maternal Role Attainment—Becoming a Mother

- “Nursing is a dynamic profession with three major foci: health promotion and prevention of illness, providing care for those who need professional assistance to achieve their optimal level of health and functioning, and research to enhance the knowledge base for providing excellent nursing care.”

- “Nurses are the health professionals having the most sustained and intense interaction with women in the maternity cycle.”

- Maternal role attainment is an interactional and developmental process occurring over time. The mother becomes attached to her infant, acquires competence in the caretaking tasks involved in the role, and expresses pleasure and gratification. (Mercer, 1986).

- Provides proper health care interventions for nontraditional mothers for them to favorably adopt a strong maternal identity.

- Uncertainty in Illness Theory

- Presents a comprehensive structure to view the experience of acute and chronic illness and organize nursing interventions to promote optimal adjustment.

- Describes how individuals form meaning from illness-related situations.

- The original theory’s concepts were organized in a linear model around the following three major themes: Antecedents of uncertainty, Process of uncertainty appraisal, and Coping with uncertainty.

- Self-Transcendence Theory

- Self-transcendence refers to the fluctuation of perceived boundaries that extend the person (or self) beyond the immediate and constricted views of self and the world (Reed, 1997).

- Has three basic concepts: vulnerability, self-transcendence, and well-being.

- Gives insight into the developmental nature of humans associated with health circumstances connected to nursing care.

- Theory of Illness Trajectory

- “The uncertainty surrounding a chronic illness like cancer is the uncertainty of life writ large. By listening to those who are tolerating this exaggerated uncertainty, we can learn much about the trajectory of living.”

- Provides a framework for nurses to understand how cancer patients stand uncertainty manifested as a loss of control.

- Provides new knowledge on how patients and families endure uncertainty and work strategically to reduce uncertainty through a dynamic flow of illness events, treatment situations, and varied players involved in care organization.

- Theory of Chronic Sorrow

- “Chronic sorrow is the presence of pervasive grief -related feelings that have been found to occur periodically throughout the lives of individuals with chronic health conditions, their family caregivers and the bereaved.”

- This middle-range theory defines the aspect of chronic sorrow as a normal response to the ongoing disparity created by the loss.

- Barker’s Tidal Model of Mental Health Recovery is widely used in mental health nursing.

- It focuses on nursing’s fundamental care processes, is universally applicable, and is a practical guide for psychiatry and mental health nursing.

- Draws on values about relating to people and help others in their moments of distress. The values of the Tidal Model are revealed in the Ten Commitments: Value the voice, Respect the language, Develop genuine curiosity, Become the apprentice, Use the available toolkit, Craft the step beyond, Give the gift of time, Reveal personal wisdom, Know that change is constant, and Be transparent.

- Theory of Comfort

- “Comfort is an antidote to the stressors inherent in health care situations today, and when comfort is enhanced, patients and families are strengthened for the tasks ahead. Also, nurses feel more satisfied with the care they are giving.”

- Patient comfort exists in three forms: relief, ease, and transcendence. These comforts can occur in four contexts: physical, psychospiritual, environmental, and sociocultural.

- As a patient’s comfort needs change, the nurse’s interventions change, as well.

- Postpartum Depression Theory

- “The birth of a baby is an occasion for joy—or so the saying goes […] But for some women, joy is not an option.”

- Described nursing as a caring profession with caring obligations to persons we care for, students, and each other.

- Provides evidence to understand and prevent postpartum depression .

- Theory of Caring

- “Caring is a nurturing way of relating to a valued other toward whom one feels a personal sense of commitment and responsibility.”

- Defines nursing as informed caring for the well-being of others.

- Offers a structure for improving up-to-date nursing practice, education, and research while bringing the discipline to its traditional values and caring-healing roots.

- Peaceful End-of-Life Theory

- The focus was not on death itself but on providing a peaceful and meaningful living in the time that remained for patients and their significant others.

- The purpose was to reflect the complexity involved in caring for terminally ill patients.

- Also known as Wanda Horta, she introduced the concepts of nursing that are accepted in Brazil.

- Wrote the book Nursing Process which presents relevance to the various fields of Nursing practice for providing a holistic view of the patient.

- Her work was recognized in all the teaching institutions called the Theory of Basic Human Needs . It is based on Maslow’s Theory of Human Motivation, whose primary concept is the hierarchy of Basic Human Needs (BHN).

- Horta’s Theory of Basic Human Needs is considered the highest point of her work, and the summary of all her research concludes sickness as a science and art of assisting a human being in meeting basic human needs, making the patient independent of this assistance through education in recovery, maintenance, and health promotion .

- Classified basic human needs into three main dimensions – psychobiological, psychosocial and psychospiritual – and establishes a relationship between the concepts of human being, environment, and nursing.

- The theory describes nursing as an element of a healthcare team and states that it can function efficiently through a scientific method. Horta referred this method as the nursing process .

- She defined the nursing process as the dynamics of systematic and interrelated actions to assist human beings. It is characterized by six phases: nursing history, nursing diagnosis , assistance plan, care plan or nursing prescription, evolution, and prognosis.

Recommended books and resources to learn more about nursing theory:

Disclosure: Included below are affiliate links from Amazon at no additional cost from you. We may earn a small commission from your purchase. For more information, check out our privacy policy .

- Nursing Theorists and Their Work (10th Edition) by Alligood Nursing Theorists and Their Work, 10th Edition provides a clear, in-depth look at nursing theories of historical and international significance. Each chapter presents a key nursing theory or philosophy, showing how systematic theoretical evidence can enhance decision making, professionalism, and quality of care.

- Knowledge Development in Nursing: Theory and Process (11th Edition) Use the five patterns of knowing to help you develop sound clinical judgment. This edition reflects the latest thinking in nursing knowledge development and adds emphasis to real-world application. The content in this edition aligns with the new 2021 AACN Essentials for Nursing Education.

- Nursing Knowledge and Theory Innovation, Second Edition: Advancing the Science of Practice (2nd Edition) This text for graduate-level nursing students focuses on the science and philosophy of nursing knowledge development. It is distinguished by its focus on practical applications of theory for scholarly, evidence-based approaches. The second edition features important updates and a reorganization of information to better highlight the roles of theory and major philosophical perspectives.

- Nursing Theories and Nursing Practice (5th Edition) The only nursing research and theory book with primary works by the original theorists. Explore the historical and contemporary theories that are the foundation of nursing practice today. The 5th Edition, continues to meet the needs of today’s students with an expanded focus on the middle range theories and practice models.

- Strategies for Theory Construction in Nursing (6th Edition) The clearest, most useful introduction to theory development methods. Reflecting vast changes in nursing practice, it covers advances both in theory development and in strategies for concept, statement, and theory development. It also builds further connections between nursing theory and evidence-based practice.

- Middle Range Theory for Nursing (4th Edition) This nursing book’s ability to break down complex ideas is part of what made this book a three-time recipient of the AJN Book of the Year award. This edition includes five completely new chapters of content essential for nursing books. New exemplars linking middle range theory to advanced nursing practice make it even more useful and expand the content to make it better.

- Nursing Research: Methods and Critical Appraisal for Evidence-Based Practice This book offers balanced coverage of both qualitative and quantitative research methodologies. This edition features new content on trending topics, including the Next-Generation NCLEX® Exam (NGN).

- Nursing Research (11th Edition) AJN award-winning authors Denise Polit and Cheryl Beck detail the latest methodologic innovations in nursing, medicine, and the social sciences. The updated 11th Edition adds two new chapters designed to help students ensure the accuracy and effectiveness of research methods. Extensively revised content throughout strengthens students’ ability to locate and rank clinical evidence.

Recommended site resources related to nursing theory:

- Nursing Theories and Theorists: The Definitive Guide for Nurses MUST READ! In this guide for nursing theories, we aim to help you understand what comprises a nursing theory and its importance, purpose, history, types or classifications, and give you an overview through summaries of selected nursing theories.

Other resources related to nursing theory:

- Betty Neuman: Neuman Systems Model

- Dorothea Orem: Self-Care Deficit Theory

- Dorothy Johnson: Behavioral System Model

- Faye Abdellah: 21 Nursing Problems Theory

- Florence Nightingale: Environmental Theory

- Hildegard Peplau: Interpersonal Relations Theory

- Ida Jean Orlando: Deliberative Nursing Process Theory

- Imogene King: Theory of Goal Attainment

- Jean Watson: Theory of Human Caring

- Lydia Hall: Care, Cure, Core Nursing Theory

- Madeleine Leininger: Transcultural Nursing Theory

- Martha Rogers: Science of Unitary Human Beings

- Myra Estrin Levine: The Conservation Model of Nursing

- Nola Pender: Health Promotion Model

- Sister Callista Roy: Adaptation Model of Nursing

- Virginia Henderson: Nursing Need Theory

Suggested readings and resources for this study guide :

- Alligood, M., & Tomey, A. (2010). Nursing theorists and their work, seventh edition (No ed.). Maryland Heights: Mosby-Elsevier.

- Alligood, M. R. (2017). Nursing Theorists and Their Work-E-Book . Elsevier Health Sciences.

- Barnard, K. E. (1984). Nursing research related to infants and young children. In Annual review of nursing research (pp. 3-25). Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg.

- Brown, H. I. (1979). Perception, theory, and commitment: The new philosophy of science . University of Chicago Press. [ Link ]

- Brown M (1964) Research in the development of nursing theory: the importance of a theoretical framework in nursing research. Nursing Research.

- Camacho, A. C. L. F., & Joaquim, F. L. (2017). Reflections based on Wanda Horta on the basic instruments of nursing. Rev Enferm UFPE [Internet], 11(12), 5432-8.

- Chinn, P. L., & Jacobs, M. K. (1978). A model for theory development in nursing. Advances in Nursing Science , 1 (1), 1-12. [ Link ]

- Colley, S. (2003). Nursing theory: its importance to practice. Nursing Standard (through 2013), 17(46), 33. [ Link ]

- Fawcett, J. (2005). Criteria for evaluation of theory. Nursing science quarterly, 18(2), 131-135. [ Link ]

- Fitzpatrick, J. J., & Whall, A. L. (Eds.). (1996). Conceptual models of nursing: Analysis and application . Connecticut, Norwalk: Appleton & Lange.

- Kaplan, A. (2017). The conduct of inquiry: Methodology for behavioural science . Routledge. [ Link ]

- Meleis, A. I. (2011). Theoretical nursing: Development and progress . Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

- Neuman, B. M., & Fawcett, J. (2002). The Neuman systems model .

- Nightingale F (1860) Notes on Nursing. New York NY, Appleton.

- Perão, O. F., Zandonadi, G. C., Rodríguez, A. H., Fontes, M. S., Nascimento, E. L. P., & Santos, E. K. A. (2017). Patient safety in an intensive care unit according to Wanda Horta’s theory. Cogitare Enfermagem, 22(3), e45657.

- Peplau H (1988) The art and science of nursing: similarities, differences, and relations. Nursing Science Quarterly

- Rogers M (1970) An Introduction to the Theoretical Basis of Nursing. Philadelphia PA, FA Davis.

51 thoughts on “Nursing Theories and Theorists: The Definitive Guide for Nurses”

Great work indeed

Amazing and simple post I have ever come across about nursing theories.

Thank you for the simplicity

where do i find the reference page in apa format?

The reference listed below the article is in APA format.

i love this. insightful. Comprehensive ,Well researched .

Thank you for these theories they are a life saver and simplified. My school require us to write about 2 nursing theorist from memory for a Comprehensive exam in which if you do not pass it you are required to wait for a year to retake the exam.

Merci beaucoup, puisque je suis très satisfait.

I’m pleased to congratulate you about your work! I really appreciate it! From: Cameroon

An entire’s semester worth of a nursing theory class, expertly and succinctly summarized in one paper. I wish my instructor were as easy to understand. Good work.

I thought this was in a chronological order based on their published works date? Then why Orlando’s theory comes at the later part? Can someone englighten me please because I am making a timeline for our project.

Great job. Very clear and succinct.

I like it. Well explained!

easy to understand and very helpful

thankyou very much.

The article was beneficial to me to understand nursing theories

This is amazing and I love it so enriching!

Thanks for the article may God bless you more Plus More Power and Protection

Thanks so much

Please can someone help me with a nursing theory related to “teamwork” please

Thank you so much !

I loved the text and saw that the nursing theorist Wanda Aguiar Horta, a Brazilian nurse and great theorist regarding basic human needs, was not included.

I suggest reviewing and including it to be more complete.

If you need, I can help with inclusion!

Best Regards

Hi João Carlos, we’d love to hear about her work. Please send us the details via our contact page: https://nurseslabs.com/contact/

Excellent study guide! Detailed, Informative and Valued! Thank you!

hi can someone help me which theorist can relate in Ear, Nose, Throat nursing care.

Wonderful contribution of shared knowledge- now how do we get the word out for nurses that are not able to afford a BSN?

Thanks for the work. It’s very helpful

This has helped me understand theories a bit better, however, there is one that is eluding me. Where does the normative theory fit in?

very educative.I have understood theories more than before.Thanks

hard work. great work in deed

I love reading your material, plain concise and easy

Very informative, more knowledgeable about the theorist

Thank you for your information. This material is great and when I have looked for material for nursing theory. I got is material with complete

A big hand of applause 👏🏿 This is a treasure for nurses of the world. Thank you so much

Hi G. ALex,

Wow, thanks for the awesome feedback! 😊 Super glad you found it to be a treasure. Just curious, was there a particular section that stood out to you or something you’d love to see more of? Always keen to hear what resonates with fellow nurses!

This is really hard work put together in a very easy to understand way.Thank you so much.It came handy

Hi Sigala, Thanks a ton for noticing the effort! 😊 Super happy to hear it came in handy for you. If you ever have suggestions or topics you’d like to see, give me a shout. Cheers to making things understandable!

Absolutely helpful. Thank you.

So glad to hear the nursing theories guide was a hit for you! 😊 If you have any other topics or questions in mind, just give a shout. Always here to help. Keep rocking your studies! Thanks Ishe!

Am happy, to read these theories, very educating. Am going to make use of it when caring for my patients. GREAT NURSES GREAT! I LOVE YOU ALL.

Hi Eboh, I’m thrilled to hear you’re excited about applying these nursing theories in practice! They can really enhance the care we provide. It’s all about putting that knowledge to good use. By the way, which theory resonated with you the most, or which do you see being most applicable in your day-to-day patient care?

How do I relate one of the theories to effective management of intravenous lines? Which theory and how to relate to the above?

Hi wanted to ask you who wrote this page who is the autor because i need to write them on footnotes and i can’t find autor of the page,neither the year it was published. Thank you. Btw this article was really helpful i never understood nursing theories this good.

Hey there Innaya, I’m glad to hear the article on nursing theories was so helpful to you! Here’s how you can cite it in APA format:

Vera, M. (2019, September 11). Nursing Theories and Theorists: The Definitive Guide for Nurses Nurseslabs. https://nurseslabs.com/nursing-theories/

If you need any more help with citations or have other questions, feel free to ask. Happy to assist!

Please is there an app I could download all these from?

Hi Felicia, Thanks for your interest! As of now, we don’t have a dedicated app for downloading our content. However, our website is mobile-friendly, so you can easily access all our resources from your smartphone or tablet browser.

wonderful insights, and very precise and easy to understand, I even got to know and learn about other new theorists of Nursing I didn’t know before.

Thank you so much for this wonderful work.

Its so amazing and very helpful. Please how can I cite any of these theory using Vancouver?

thanls for good informatiom need to explain example

Great!. Useful information to the lecturers, and educators toward delivery info to our young generation nursing.

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Log in using your username and password

- Search More Search for this keyword Advanced search

- Latest content

- Current issue

- Write for Us

- BMJ Journals

You are here

- Volume 27, Issue 1

- Induction, deduction and abduction

- Article Text

- Article info

- Citation Tools

- Rapid Responses

- Article metrics

- http://orcid.org/0000-0003-4308-4219 David Barrett 1 ,

- http://orcid.org/0000-0003-0157-5319 Ahtisham Younas 2 , 3

- 1 Department of Health Sciences , University of York , York , UK

- 2 Memorial University of Newfoundland , St. John's , Newfoundland , Canada

- 3 Swat College of Nursing , Pakistan

- Correspondence to Professor David Barrett, Department of Health Sciences, University of York, York, UK; david.i.barrett{at}york.ac.uk

https://doi.org/10.1136/ebnurs-2023-103873

Statistics from Altmetric.com

Request permissions.

If you wish to reuse any or all of this article please use the link below which will take you to the Copyright Clearance Center’s RightsLink service. You will be able to get a quick price and instant permission to reuse the content in many different ways.

- Nursing Research

Researchers often refer to the type of ‘reasoning’ that they have used to support their analysis and reach conclusions within their study. For example, Krick and colleagues completed a study that supported the development of an outcome framework for measuring the effectiveness of digital nursing technologies. 1 They reported completing the analysis through combining ‘an inductive and deductive approach’ (p1), but what do these terms mean? How can these methods of reasoning support nursing practice, and guide the development and appraisal of research evidence?

This article will explore inductive and deductive reasoning and their place in nursing research. We will also explore a third approach to reasoning—abductive reasoning—which is arguably less well-known than induction and deduction, but just as prevalent and important in nursing practice and nursing research.

Inductive reasoning

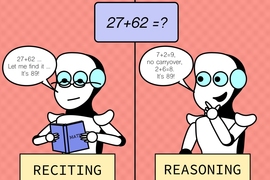

Induction, or inductive reasoning, involves the identification of cues and the collection of data to develop general theories or hypotheses. For this reason, inductive reasoning is often described as being ‘bottom-up’ reasoning. In the paper by Krick and colleagues mentioned previously, the inductive element of their work was taking findings from individual studies in a scoping review and using these to ‘inductively derive’ a first draft of their digital nursing outcomes framework. 1

It is easy to see how this study—and many other qualitative pieces of nursing research—frame themselves as having used inductive reasoning, with data from individuals building piece-by-piece into a general theory or overview of a phenomenon. However, the inductive nature of qualitative research is not universally accepted. Bergdahl and Berterö, discuss the ‘myth’ of inductive reasoning in qualitative research. 4 Though they agree that inductive methods require using direct observations or experiments to develop a general theory, they suggest that this is not what qualitative researchers do. Instead, they argue that the codes and themes developed during qualitative research are not tested scientifically, so do not represent true inductive reasoning. Instead, the generation of theory in qualitative research—they argue—requires a ‘creative leap’ which is well beyond the scope of an inductive approach. 4

Deductive reasoning

In their critique of induction in qualitative research, Bergdahl and Berterö argue that qualitative researchers should be more open to a deductive approach. 4 At a superficial level, deductive reasoning can be viewed as the opposite to induction, with specific conclusions drawn from general theories. So, with inductive reasoning often conceptualised as ‘bottom-up’, deductive reasoning can be viewed as ‘top-down’.

Some researchers have applied deductive reasoning within qualitative research as advocated by Bergdahl and Berterö, often by analysing qualitative data in the context of existing theory. A 2022 study by Andersson and colleagues explored critical care nurses’ experiences of working during the first phase of the COVID-19 pandemic. However, rather than starting their analysis of qualitative interviews with a ‘blank canvas’ (as would be the case in a study using inductive reasoning), the authors applied an existing person-centred practice framework as a lens through which the data could be better understood and interpreted. 5

Often, we see deductive reasoning linked to the hypothesis-testing nature of quantitative nursing research. A typical example is from Chang and colleagues, who completed a randomised controlled trial (RCT) in which the impact of a simulation-based mobile app on student learning was evaluated. 6 The authors developed a set of hypotheses (the ‘general theory’ that forms the foundation of deductive reasoning) related to student learning and satisfaction and then tested whether these were supported through analysis of outcomes in the intervention (mobile app) and control (usual paper-based learning) groups. Through analysis of findings, the authors demonstrated the use of a deductive approach to confirm a theory-based hypothesis. 6

Abductive reasoning

The two approaches discussed so far—induction and deduction—would seem to provide the foundation for much of what nurse researchers seek to do. Induction allows us to build theory from data, and deduction allows us to test theory and hypotheses. However, there is a third approach to reasoning — abduction—which is under-represented in the nursing evidence base, despite its importance to both research and practice. 7

With abduction, we generate new ideas from, and recognise meaning in, the information that is available to us. 8 The key point here is that we ‘generate’ new ideas, rather than test or verify them in the way that we should when using inductive or deductive reasoning. Abductive reasoning therefore plays an important part in both quantitative and qualitative research.

From a quantitative perspective, it is often abductive reasoning that we use to first develop the hypothesis or theory that we can then test deductively. A set of observations about an element of nursing practice may lead us—through abductive reasoning—to develop a hypothesis that best explains what we have seen. We can then apply the hypothetico-deductive approach to test this, as with the RCT by Chang and colleagues described earlier.

In qualitative research, abduction may offer the solution to the ‘myth’ of inductive reasoning proposed by Bergdahl and Berterö. The ‘creative leap’ that they state qualitative researchers must make to turn their data into general theories, 4 aligns well with the moment of discovery often associated with abductive reasoning.

Though abductive reasoning is a critical part of nursing practice and research, there is ongoing discussion about how effective it is when used as the only form of reasoning. Given the importance of producing research that supports evidence-based nursing care, it could be argued that suppositions based on abduction alone require testing by inductive and deductive methods before they can be generalised and implemented with confidence. 7