BLOG | PODCAST NETWORK | ADMIN. MASTERMIND | SWAG & MERCH | ONLINE TRAINING

- Meet the Team

- Join the Team

- Our Philosophy

- Teach Better Mindset

- Custom Professional Development

- Livestream Shows & Videos

- Administrator Mastermind

- Academy Online Courses

- EDUcreator Club+

- Podcast Network

- Speakers Network

- Free Downloads

- Ambassador Program

- Free Facebook Group

- Professional Development

- Request Training

- Speakers Network Home

- Keynote Speakers

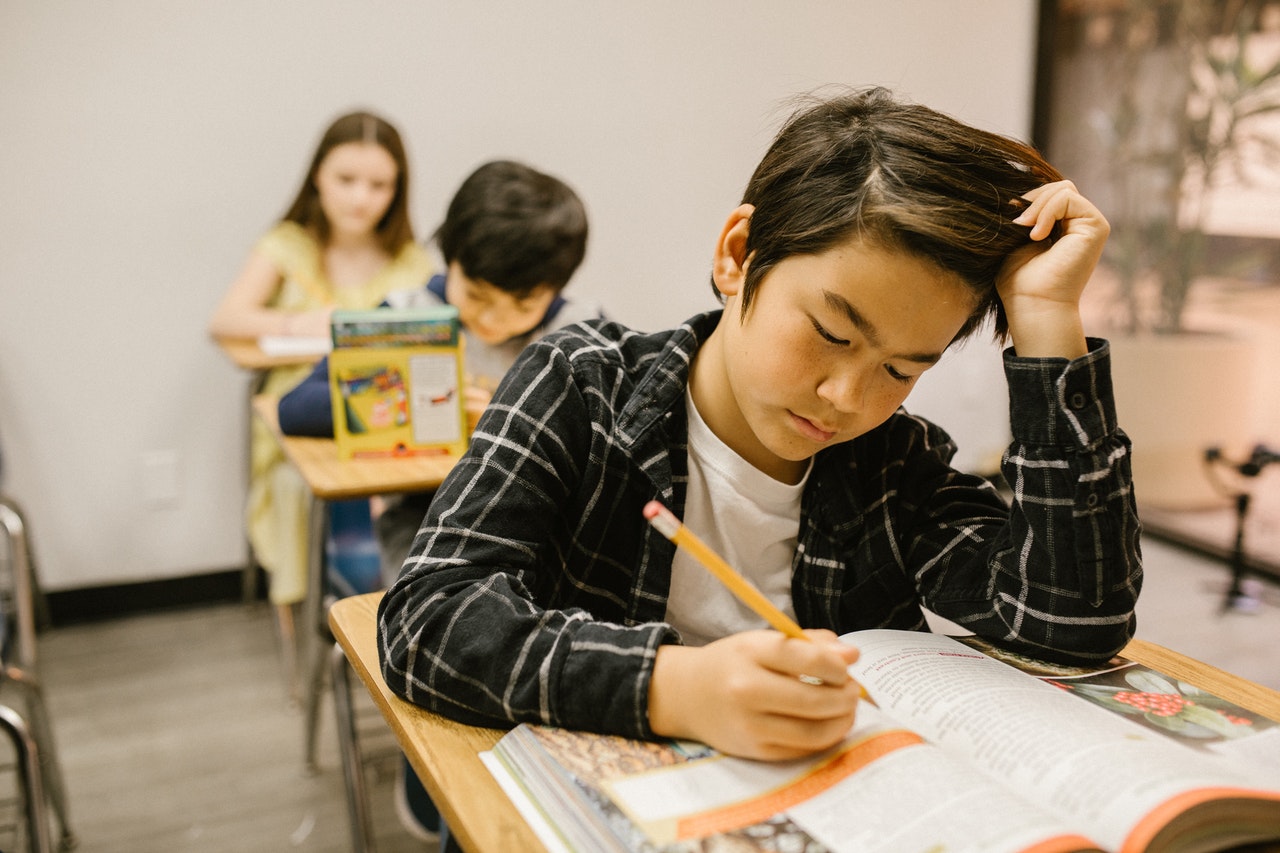

Strategies to Increase Critical Thinking Skills in students

Matthew Joseph October 2, 2019 Blog , Engage Better , Lesson Plan Better , Personalize Student Learning Better

In This Post:

- The importance of helping students increase critical thinking skills.

- Ways to promote the essential skills needed to analyze and evaluate.

- Strategies to incorporate critical thinking into your instruction.

We ask our teachers to be “future-ready” or say that we are teaching “for jobs that don’t exist yet.” These are powerful statements. At the same time, they give teachers the impression that we have to drastically change what we are doing .

So how do we plan education for an unknown job market or unknown needs?

My answer: We can’t predict the jobs, but whatever they are, students will need to think critically to do them. So, our job is to teach our students HOW to think, not WHAT to think.

Helping Students Become Critical Thinkers

My answer is rooted in the call to empower our students to be critical thinkers. I believe that to be critical thinkers, educators need to provide students with the strategies they need. And we need to ask more than just surface-level questions.

Questions to students must motivate them to dig up background knowledge. They should inspire them to make connections to real-world scenarios. These make the learning more memorable and meaningful.

Critical thinking is a general term. I believe this term means that students effectively identify, analyze, and evaluate content or skills. In this process, they (the students) will discover and present convincing reasons in support of their answers or thinking.

You can look up critical thinking and get many definitions like this one from Wikipedia: “ Critical thinking consists of a mental process of analyzing or evaluating information, particularly statements or propositions that people have offered as true. ”

Essential Skills for Critical Thinking

In my current role as director of curriculum and instruction, I work to promote the use of 21st-century tools and, more importantly, thinking skills. Some essential skills that are the basis for critical thinking are:

- Communication and Information skills

- Thinking and Problem-Solving skills

- Interpersonal and Self- Directional skills

- Collaboration skills

These four bullets are skills students are going to need in any field and in all levels of education. Hence my answer to the question. We need to teach our students to think critically and for themselves.

One of the goals of education is to prepare students to learn through discovery . Providing opportunities to practice being critical thinkers will assist students in analyzing others’ thinking and examining the logic of others.

Understanding others is an essential skill in collaboration and in everyday life. Critical thinking will allow students to do more than just memorize knowledge.

Ask Questions

So how do we do this? One recommendation is for educators to work in-depth questioning strategies into a lesson launch.

Ask thoughtful questions to allow for answers with sound reasoning. Then, word conversations and communication to shape students’ thinking. Quick answers often result in very few words and no eye contact, which are skills we don’t want to promote.

When you are asking students questions and they provide a solution, try some of these to promote further thinking:

- Could you elaborate further on that point?

- Will you express that point in another way?

- Can you give me an illustration?

- Would you give me an example?

- Will you you provide more details?

- Could you be more specific?

- Do we need to consider another point of view?

- Is there another way to look at this question?

Utilizing critical thinking skills could be seen as a change in the paradigm of teaching and learning. Engagement in education will enhance the collaboration among teachers and students. It will also provide a way for students to succeed even if the school system had to start over.

[scroll down to keep reading]

Promoting critical thinking into all aspects of instruction.

Engagement, application, and collaboration are skills that withstand the test of time. I also promote the integration of critical thinking into every aspect of instruction.

In my experience, I’ve found a few ways to make this happen.

Begin lessons/units with a probing question: It shouldn’t be a question you can answer with a ‘yes’ or a ‘no.’ These questions should inspire discovery learning and problem-solving.

Encourage Creativity: I have seen teachers prepare projects before they give it to their students many times. For example, designing snowmen or other “creative” projects. By doing the design work or by cutting all the circles out beforehand, it removes creativity options.

It may help the classroom run more smoothly if every child’s material is already cut out, but then every student’s project looks the same. Students don’t have to think on their own or problem solve.

Not having everything “glue ready” in advance is a good thing. Instead, give students all the supplies needed to create a snowman, and let them do it on their own.

Giving independence will allow students to become critical thinkers because they will have to create their own product with the supplies you give them. This might be an elementary example, but it’s one we can relate to any grade level or project.

Try not to jump to help too fast – let the students work through a productive struggle .

Build in opportunities for students to find connections in learning. Encouraging students to make connections to a real-life situation and identify patterns is a great way to practice their critical thinking skills. The use of real-world scenarios will increase rigor, relevance, and critical thinking.

A few other techniques to encourage critical thinking are:

- Use analogies

- Promote interaction among students

- Ask open-ended questions

- Allow reflection time

- Use real-life problems

- Allow for thinking practice

Critical thinking prepares students to think for themselves for the rest of their lives. I also believe critical thinkers are less likely to go along with the crowd because they think for themselves.

About Matthew X. Joseph, Ed.D.

Dr. Matthew X. Joseph has been a school and district leader in many capacities in public education over his 25 years in the field. Experiences such as the Director of Digital Learning and Innovation in Milford Public Schools (MA), elementary school principal in Natick, MA and Attleboro, MA, classroom teacher, and district professional development specialist have provided Matt incredible insights on how to best support teaching and learning. This experience has led to nationally publishing articles and opportunities to speak at multiple state and national events. He is the author of Power of Us: Creating Collaborative Schools and co-author of Modern Mentoring , Reimagining Teacher Mentorship (Due out, fall 2019). His master’s degree is in special education and his Ed.D. in Educational Leadership from Boston College.

Visit Matthew’s Blog

- Our Mission

Helping Students Hone Their Critical Thinking Skills

Used consistently, these strategies can help middle and high school teachers guide students to improve much-needed skills.

Critical thinking skills are important in every discipline, at and beyond school. From managing money to choosing which candidates to vote for in elections to making difficult career choices, students need to be prepared to take in, synthesize, and act on new information in a world that is constantly changing.

While critical thinking might seem like an abstract idea that is tough to directly instruct, there are many engaging ways to help students strengthen these skills through active learning.

Make Time for Metacognitive Reflection

Create space for students to both reflect on their ideas and discuss the power of doing so. Show students how they can push back on their own thinking to analyze and question their assumptions. Students might ask themselves, “Why is this the best answer? What information supports my answer? What might someone with a counterargument say?”

Through this reflection, students and teachers (who can model reflecting on their own thinking) gain deeper understandings of their ideas and do a better job articulating their beliefs. In a world that is go-go-go, it is important to help students understand that it is OK to take a breath and think about their ideas before putting them out into the world. And taking time for reflection helps us more thoughtfully consider others’ ideas, too.

Teach Reasoning Skills

Reasoning skills are another key component of critical thinking, involving the abilities to think logically, evaluate evidence, identify assumptions, and analyze arguments. Students who learn how to use reasoning skills will be better equipped to make informed decisions, form and defend opinions, and solve problems.

One way to teach reasoning is to use problem-solving activities that require students to apply their skills to practical contexts. For example, give students a real problem to solve, and ask them to use reasoning skills to develop a solution. They can then present their solution and defend their reasoning to the class and engage in discussion about whether and how their thinking changed when listening to peers’ perspectives.

A great example I have seen involved students identifying an underutilized part of their school and creating a presentation about one way to redesign it. This project allowed students to feel a sense of connection to the problem and come up with creative solutions that could help others at school. For more examples, you might visit PBS’s Design Squad , a resource that brings to life real-world problem-solving.

Ask Open-Ended Questions

Moving beyond the repetition of facts, critical thinking requires students to take positions and explain their beliefs through research, evidence, and explanations of credibility.

When we pose open-ended questions, we create space for classroom discourse inclusive of diverse, perhaps opposing, ideas—grounds for rich exchanges that support deep thinking and analysis.

For example, “How would you approach the problem?” and “Where might you look to find resources to address this issue?” are two open-ended questions that position students to think less about the “right” answer and more about the variety of solutions that might already exist.

Journaling, whether digitally or physically in a notebook, is another great way to have students answer these open-ended prompts—giving them time to think and organize their thoughts before contributing to a conversation, which can ensure that more voices are heard.

Once students process in their journal, small group or whole class conversations help bring their ideas to life. Discovering similarities between answers helps reveal to students that they are not alone, which can encourage future participation in constructive civil discourse.

Teach Information Literacy

Education has moved far past the idea of “Be careful of what is on Wikipedia, because it might not be true.” With AI innovations making their way into classrooms, teachers know that informed readers must question everything.

Understanding what is and is not a reliable source and knowing how to vet information are important skills for students to build and utilize when making informed decisions. You might start by introducing the idea of bias: Articles, ads, memes, videos, and every other form of media can push an agenda that students may not see on the surface. Discuss credibility, subjectivity, and objectivity, and look at examples and nonexamples of trusted information to prepare students to be well-informed members of a democracy.

One of my favorite lessons is about the Pacific Northwest tree octopus . This project asks students to explore what appears to be a very real website that provides information on this supposedly endangered animal. It is a wonderful, albeit over-the-top, example of how something might look official even when untrue, revealing that we need critical thinking to break down “facts” and determine the validity of the information we consume.

A fun extension is to have students come up with their own website or newsletter about something going on in school that is untrue. Perhaps a change in dress code that requires everyone to wear their clothes inside out or a change to the lunch menu that will require students to eat brussels sprouts every day.

Giving students the ability to create their own falsified information can help them better identify it in other contexts. Understanding that information can be “too good to be true” can help them identify future falsehoods.

Provide Diverse Perspectives

Consider how to keep the classroom from becoming an echo chamber. If students come from the same community, they may have similar perspectives. And those who have differing perspectives may not feel comfortable sharing them in the face of an opposing majority.

To support varying viewpoints, bring diverse voices into the classroom as much as possible, especially when discussing current events. Use primary sources: videos from YouTube, essays and articles written by people who experienced current events firsthand, documentaries that dive deeply into topics that require some nuance, and any other resources that provide a varied look at topics.

I like to use the Smithsonian “OurStory” page , which shares a wide variety of stories from people in the United States. The page on Japanese American internment camps is very powerful because of its first-person perspectives.

Practice Makes Perfect

To make the above strategies and thinking routines a consistent part of your classroom, spread them out—and build upon them—over the course of the school year. You might challenge students with information and/or examples that require them to use their critical thinking skills; work these skills explicitly into lessons, projects, rubrics, and self-assessments; or have students practice identifying misinformation or unsupported arguments.

Critical thinking is not learned in isolation. It needs to be explored in English language arts, social studies, science, physical education, math. Every discipline requires students to take a careful look at something and find the best solution. Often, these skills are taken for granted, viewed as a by-product of a good education, but true critical thinking doesn’t just happen. It requires consistency and commitment.

In a moment when information and misinformation abound, and students must parse reams of information, it is imperative that we support and model critical thinking in the classroom to support the development of well-informed citizens.

- Featured Articles

- Report Card Comments

- Needs Improvement Comments

- Teacher's Lounge

- New Teachers

- Our Bloggers

- Article Library

- Featured Lessons

- Every-Day Edits

- Lesson Library

- Emergency Sub Plans

- Character Education

- Lesson of the Day

- 5-Minute Lessons

- Learning Games

- Lesson Planning

- Subjects Center

- Teaching Grammar

- Leadership Resources

- Parent Newsletter Resources

- Advice from School Leaders

- Programs, Strategies and Events

- Principal Toolbox

- Administrator's Desk

- Interview Questions

- Professional Learning Communities

- Teachers Observing Teachers

- Tech Lesson Plans

- Science, Math & Reading Games

- Tech in the Classroom

- Web Site Reviews

- Creating a WebQuest

- Digital Citizenship

- All Online PD Courses

- Child Development Courses

- Reading and Writing Courses

- Math & Science Courses

- Classroom Technology Courses

- Spanish in the Classroom Course

- Classroom Management

- Responsive Classroom

- Dr. Ken Shore: Classroom Problem Solver

- A to Z Grant Writing Courses

- Worksheet Library

- Highlights for Children

- Venn Diagram Templates

- Reading Games

- Word Search Puzzles

- Math Crossword Puzzles

- Geography A to Z

- Holidays & Special Days

- Internet Scavenger Hunts

- Student Certificates

Newsletter Sign Up

Search form

Strategies for encouraging critical thinking skills in students.

With kids today dealing with information overload, the ability to think critically has become a forgotten skill. But critical thinking skills enable students to analyze, evaluate, and apply information, fostering their ability to solve complex problems and make informed decisions. So how do we bridge that gap?

As educators, we need to use more strategies that promote critical thinking in our students. These seven strategies can help students cultivate their critical thinking skills. (These strategies can be modified for all students with the aid of a qualified educator.)

1. Encourage Questioning

One of the fundamental pillars of critical thinking is curiosity. Encourage students to ask questions about the subject matter and challenge existing assumptions. Create a safe and supportive environment where students feel comfortable expressing their thoughts and ideas. By nurturing their inquisitive nature, you can stimulate critical thinking and empower students to explore different perspectives.

2. Foster Discussions

Engage students in meaningful discussions that require them to examine various viewpoints. Encourage active participation, respectful listening, and constructive criticism. Assign topics that involve controversial and current issues, enabling students to analyze arguments, provide evidence, and formulate their own conclusions in a safe environment.

By engaging in intellectual discourse, students refine their critical thinking skills while honing their ability to articulate and defend their positions. And remember to offer sentence starters for ELD students to feel successful and included in the process, such as:

- "I felt the character Wilbur was a good friend to Charlotte because..."

- "I felt the character Wilbur was not a good friend to Charlotte because..."

3. Teach Information Evaluation

In the age of readily available information, students must be able to evaluate sources. Teach your students how to assess information's credibility, bias, and relevance. Encourage them to cross-reference multiple sources and identify reliable and reputable resources.

Emphasize the importance of distinguishing fact from opinion and encourage students to question the validity of claims. Providing students with tools and frameworks for information evaluation equips them to make informed judgments and enhances their critical thinking abilities.

4. Incorporate Problem-Solving Activities

Integrate problem-solving activities into your curriculum to foster critical thinking skills. Provide students with real-world scenarios that require analysis, synthesis, and decision-making. These activities can include case studies, group projects, or simulations.

Encourage students to break down complex problems into manageable parts, consider alternative solutions, and evaluate the potential outcomes. Students will begin to develop their critical thinking skills and apply their knowledge to practical situations by engaging in problem-solving activities.

5. Promote Reflection and Metacognition

Allocate time for reflection and metacognitive (an understanding of one's thought process) practices. Encourage students to review their thinking processes and reflect on their learning experiences. For example, what went right and/or wrong helps students evaluate the learning process.

Provide prompts that help your students analyze their reasoning, identify biases, and recognize areas for improvement. Journaling, self-assessments, and group discussions can facilitate this reflective process. By engaging in metacognition, students become more aware of their thinking patterns and develop strategies to enhance their critical thinking abilities.

6. Encourage Creative Thinking

Creativity and critical thinking go hand in hand. Encourage students to think creatively by incorporating open-ended tasks and projects. Assign projects requiring them to think outside the box, develop innovative solutions, and analyze potential risks and benefits. Emphasize the value of brainstorming, divergent thinking, and considering multiple perspectives. By nurturing creative thinking, students develop the ability to approach problems from unique angles, fostering their critical thinking skills.

7. Provide Scaffolding and Support

Recognize that critical thinking is a developmental process. Provide scaffolding and support as students build their critical thinking skills. This strategy is especially important for students needing additional help as outlined in their IEP or 504.

Offer guidance, modeling, and feedback to help students navigate complex tasks. Gradually increase the complexity of assignments and provide opportunities for independent thinking and decision-making. By offering appropriate support, you empower students to develop their critical thinking skills while building their confidence and independence.

Implement Critical Thinking Strategies Now

Cultivating critical thinking skills in your students is vital for their academic success and their ability to thrive in an ever-changing world. By implementing various strategies, educators can foster an environment that nurtures critical thinking skills. As students develop these skills, they become active learners who can analyze, evaluate, and apply knowledge effectively, enabling them to tackle challenges and make informed decisions throughout their lives.

EW Lesson Plans

EW Professional Development

Ew worksheets.

Sign up for our free weekly newsletter and receive top education news, lesson ideas, teaching tips and more! No thanks, I don't need to stay current on what works in education! COPYRIGHT 1996-2016 BY EDUCATION WORLD, INC. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. COPYRIGHT 1996 - 2024 BY EDUCATION WORLD, INC. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

The Will to Teach Critical Thinking in the Classroom: A Guide for TeachersIn the ever-evolving landscape of education, teaching students the skill of critical thinking has become a priority. This powerful tool empowers students to evaluate information, make reasoned judgments, and approach problems from a fresh perspective. In this article, we’ll explore the significance of critical thinking and provide effective strategies to nurture this skill in your students. Why is Fostering Critical Thinking Important?Strategies to cultivate critical thinking, real-world example, concluding thoughts. Critical thinking is a key skill that goes far beyond the four walls of a classroom. It equips students to better understand and interact with the world around them. Here are some reasons why fostering critical thinking is important:

Creating an environment that encourages critical thinking can be accomplished in various ways. Here are some effective strategies:

As a school leader, I’ve seen the transformative power of critical thinking. During a school competition, I observed a team of students tasked with proposing a solution to reduce our school’s environmental impact. Instead of jumping to obvious solutions, they critically evaluated multiple options, considering the feasibility, cost, and potential impact of each. They ultimately proposed a comprehensive plan that involved water conservation, waste reduction, and energy efficiency measures. This demonstrated their ability to critically analyze a problem and develop an effective solution. Critical thinking is an essential skill for students in the 21st century. It equips them to understand and navigate the world in a thoughtful and informed manner. As a teacher, incorporating strategies to foster critical thinking in your classroom can make a lasting impact on your students’ educational journey and life beyond school. 1. What is critical thinking? Critical thinking is the ability to analyze information objectively and make a reasoned judgment. 2. Why is critical thinking important for students? Critical thinking helps students make informed decisions, develop analytical skills, and promotes independence. 3. What are some strategies to cultivate critical thinking in students? Strategies can include Socratic questioning, debates and discussions, teaching metacognition, and problem-solving activities. 4. How can I assess my students’ critical thinking skills? You can assess critical thinking skills through essays, presentations, discussions, and problem-solving tasks that require thoughtful analysis. 5. Can critical thinking be taught? Yes, critical thinking can be taught and nurtured through specific teaching strategies and a supportive learning environment. Related Posts7 simple strategies for strong student-teacher relationships. Getting to know your students on a personal level is the first step towards building strong relationships. Show genuine interest in their lives outside the classroom.  Connecting Learning to Real-World Contexts: Strategies for TeachersWhen students see the relevance of their classroom lessons to their everyday lives, they are more likely to be motivated, engaged, and retain information.  Encouraging Active Involvement in Learning: Strategies for TeachersActive learning benefits students by improving retention of information, enhancing critical thinking skills, and encouraging a deeper understanding of the subject matter.  Collaborative and Cooperative Learning: A Guide for TeachersThese methods encourage students to work together, share ideas, and actively participate in their education.  Experiential Teaching: Role-Play and Simulations in TeachingThese interactive techniques allow students to immerse themselves in practical, real-world scenarios, thereby deepening their understanding and retention of key concepts.  Project-Based Learning Activities: A Guide for TeachersProject-Based Learning is a student-centered pedagogy that involves a dynamic approach to teaching, where students explore real-world problems or challenges. Leave a Reply Cancel replyYour email address will not be published. Required fields are marked * Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment. Educationise 11 Activities That Promote Critical Thinking In The ClassIgnite your child’s curiosity with our exclusive “Learning Adventures Activity Workbook for Kids” a perfect blend of education and adventure! Critical thinking activities encourage individuals to analyze, evaluate, and synthesize information to develop informed opinions and make reasoned decisions. Engaging in such exercises cultivates intellectual agility, fostering a deeper understanding of complex issues and honing problem-solving skills for navigating an increasingly intricate world. Through critical thinking, individuals empower themselves to challenge assumptions, uncover biases, and constructively contribute to discourse, thereby enriching both personal growth and societal progress. Critical thinking serves as the cornerstone of effective problem-solving, enabling individuals to dissect challenges, explore diverse perspectives, and devise innovative solutions grounded in logic and evidence. For engaging problem solving activities, read our article problem solving activities that enhance student’s interest. 52 Critical Thinking Flashcards for Problem Solving What is Critical Thinking? Critical thinking is a 21st-century skill that enables a person to think rationally and logically in order to reach a plausible conclusion. A critical thinker assesses facts and figures and data objectively and determines what to believe and what not to believe. Critical thinking skills empower a person to decipher complex problems and make impartial and better decisions based on effective information. More Articles from Educationise

Importance of Acquiring Critical Thinking SkillsCritical thinking skills cultivate habits of mind such as strategic thinking, skepticism, discerning fallacy from the facts, asking good questions and probing deep into the issues to find the truth. Acquiring critical thinking skills was never as valuable as it is today because of the prevalence of the modern knowledge economy. Today, information and technology are the driving forces behind the global economy. To keep pace with ever-changing technology and new inventions, one has to be flexible enough to embrace changes swiftly. Today critical thinking skills are one of the most sought-after skills by the companies. In fact, critical thinking skills are paramount not only for active learning and academic achievement but also for the professional career of the students. The lack of critical thinking skills catalyzes memorization of the topics without a deeper insight, egocentrism, closed-mindedness, reduced student interest in the classroom and not being able to make timely and better decisions. Benefits of Critical Thinking Skills in Education Certain strategies are more eloquent than others in teaching students how to think critically. Encouraging critical thinking in the class is indispensable for the learning and growth of the students. In this way, we can raise a generation of innovators and thinkers rather than followers. Some of the benefits offered by thinking critically in the classroom are given below:

Read our article: How to Foster Critical Thinking Skills in Students? Creative Strategies and Real-World Examples

Critical Thinking Lessons and Activities 11 Activities that Promote Critical Thinking in the ClassWe have compiled a list of 11 activities that will facilitate you to promote critical thinking abilities in the students. We have also covered problem solving activities that enhance student’s interest in our another article. Click here to read it. 1. Worst Case ScenarioDivide students into teams and introduce each team with a hypothetical challenging scenario. Allocate minimum resources and time to each team and ask them to reach a viable conclusion using those resources. The scenarios can include situations like stranded on an island or stuck in a forest. Students will come up with creative solutions to come out from the imaginary problematic situation they are encountering. Besides encouraging students to think critically, this activity will enhance teamwork, communication and problem-solving skills of the students. Read our article: 10 Innovative Strategies for Promoting Critical Thinking in the Classroom 2. If You Build ItIt is a very flexible game that allows students to think creatively. To start this activity, divide students into groups. Give each group a limited amount of resources such as pipe cleaners, blocks, and marshmallows etc. Every group is supposed to use these resources and construct a certain item such as building, tower or a bridge in a limited time. You can use a variety of materials in the classroom to challenge the students. This activity is helpful in promoting teamwork and creative skills among the students. It is also one of the classics which can be used in the classroom to encourage critical thinking. Print pictures of objects, animals or concepts and start by telling a unique story about the printed picture. The next student is supposed to continue the story and pass the picture to the other student and so on. 4. Keeping it RealIn this activity, you can ask students to identify a real-world problem in their schools, community or city. After the problem is recognized, students should work in teams to come up with the best possible outcome of that problem. 5. Save the EggMake groups of three or four in the class. Ask them to drop an egg from a certain height and think of creative ideas to save the egg from breaking. Students can come up with diverse ideas to conserve the egg like a soft-landing material or any other device. Remember that this activity can get chaotic, so select the area in the school that can be cleaned easily afterward and where there are no chances of damaging the school property. 6. Start a DebateIn this activity, the teacher can act as a facilitator and spark an interesting conversation in the class on any given topic. Give a small introductory speech on an open-ended topic. The topic can be related to current affairs, technological development or a new discovery in the field of science. Encourage students to participate in the debate by expressing their views and ideas on the topic. Conclude the debate with a viable solution or fresh ideas generated during the activity through brainstorming. 7. Create and InventThis project-based learning activity is best for teaching in the engineering class. Divide students into groups. Present a problem to the students and ask them to build a model or simulate a product using computer animations or graphics that will solve the problem. After students are done with building models, each group is supposed to explain their proposed product to the rest of the class. The primary objective of this activity is to promote creative thinking and problem-solving skills among the students. 8. Select from AlternativesThis activity can be used in computer science, engineering or any of the STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, Mathematics) classes. Introduce a variety of alternatives such as different formulas for solving the same problem, different computer codes, product designs or distinct explanations of the same topic. Form groups in the class and ask them to select the best alternative. Each group will then explain its chosen alternative to the rest of the class with reasonable justification of its preference. During the process, the rest of the class can participate by asking questions from the group. This activity is very helpful in nurturing logical thinking and analytical skills among the students. 9. Reading and CritiquingPresent an article from a journal related to any topic that you are teaching. Ask the students to read the article critically and evaluate strengths and weaknesses in the article. Students can write about what they think about the article, any misleading statement or biases of the author and critique it by using their own judgments. In this way, students can challenge the fallacies and rationality of judgments in the article. Hence, they can use their own thinking to come up with novel ideas pertaining to the topic. 10. Think Pair ShareIn this activity, students will come up with their own questions. Make pairs or groups in the class and ask the students to discuss the questions together. The activity will be useful if the teacher gives students a topic on which the question should be based. For example, if the teacher is teaching biology, the questions of the students can be based on reverse osmosis, human heart, respiratory system and so on. This activity drives student engagement and supports higher-order thinking skills among students. 11. Big Paper – Silent ConversationSilence is a great way to slow down thinking and promote deep reflection on any subject. Present a driving question to the students and divide them into groups. The students will discuss the question with their teammates and brainstorm their ideas on a big paper. After reflection and discussion, students can write their findings in silence. This is a great learning activity for students who are introverts and love to ruminate silently rather than thinking aloud. Finally, for students with critical thinking, you can go to GS-JJ.co m to customize exclusive rewards, which not only enlivens the classroom, but also promotes the development and training of students for critical thinking. Share this:4 thoughts on “ 11 activities that promote critical thinking in the class ”.

Thanks for the great article! Especially with the post-pandemic learning gap, these critical thinking skills are essential! It’s also important to teach them a growth mindset. If you are interested in that, please check out The Teachers’ Blog! Leave a Reply Cancel replyDiscover more from educationise. Subscribe now to keep reading and get access to the full archive. Type your email… Continue reading The Importance of Critical Thinking Skills for StudentsLink Copied Share on Facebook Share on Twitter Share on LinkedIn .jpg) Brains at Work! If you’re moving toward the end of your high school career, you’ve likely heard a lot about college life and how different it is from high school. Classes are more intense, professors are stricter, and the curriculum is more complicated. All in all, it’s very different compared to high school. Different doesn’t have to mean scary, though. If you’re nervous about beginning college and you’re worried about how you’ll learn in a place so different from high school, there are steps you can take to help you thrive in your college career. If you’re wondering how to get accepted into college and how to succeed as a freshman in such a new environment, the answer is simple: harness the power of critical thinking skills for students. What is critical thinking?Critical thinking entails using reasoning and the questioning of assumptions to address problems, assess information, identify biases, and more. It's a skillset crucial for students navigating their academic journey and beyond, including how to get accepted into college . At its crux, critical thinking for students has everything to do with self-discipline and making active decisions to 'think outside the box,' allowing individuals to think beyond a concept alone in order to understand it better. Critical thinking skills for students is a concept highly encouraged in any and every educational setting, and with good reason. Possessing strong critical thinking skills will make you a better student and, frankly, help you gain valuable life skills. Not only will you be more efficient in gathering knowledge and processing information, but you will also enhance your ability to analyse and comprehend it. Importance of critical thinking for studentsDeveloping critical thinking skills for students is essential for success at all academic levels, particularly in college. It introduces reflection and perspective while encouraging you to question what you’re learning! Even if you’ve seen solid facts. Asking questions, considering other perspectives, and self-reflection cultivate resilient students with endless potential for learning, retention, and personal growth.A well-developed set of critical thinking skills for students will help them excel in many areas. Here are some critical thinking examples for students: 1. Decision-makingIf you’re thinking critically, you’re not making impulse decisions or snap judgments; you’re taking the time to weigh the pros and cons. You’re making informed decisions. Critical thinking skills for students can make all the difference. 2. Problem-solvingStudents with critical thinking skills are more effective in problem-solving. This reflective thinking process helps you use your own experiences to ideate innovations, solutions, and decisions. 3. CommunicationStrong communication skills are a vital aspect of critical thinking for students, helping with their overall critical thinking abilities. How can you learn without asking questions? Critical thinking for students is what helps them produce the questions they may not have ever thought to ask. As a critical thinker, you’ll get better at expressing your ideas concisely and logically, facilitating thoughtful discussion, and learning from your teachers and peers. 4. Analytical skillsDeveloping analytical skills is a key component of strong critical thinking skills for students. It goes beyond study tips on reviewing data or learning a concept. It’s about the “Who? What? Where? Why? When? How?” When you’re thinking critically, these questions will come naturally, and you’ll be an expert learner because of it. How can students develop critical thinking skillsAlthough critical thinking skills for students is an important and necessary process, it isn’t necessarily difficult to develop these observational skills. All it takes is a conscious effort and a little bit of practice. Here are a few tips to get you started: 1. Never stop asking questionsThis is the best way to learn critical thinking skills for students. As stated earlier, ask questions—even if you’re presented with facts to begin with. When you’re examining a problem or learning a concept, ask as many questions as you can. Not only will you be better acquainted with what you’re learning, but it’ll soon become second nature to follow this process in every class you take and help you improve your GPA . 2. Practice active listeningAs important as asking questions is, it is equally vital to be a good listener to your peers. It is astounding how much we can learn from each other in a collaborative environment! Diverse perspectives are key to fostering critical thinking skills for students. Keep an open mind and view every discussion as an opportunity to learn. 3. Dive into your creativityAlthough a college environment is vastly different from high school classrooms, one thing remains constant through all levels of education: the importance of creativity. Creativity is a guiding factor through all facets of critical thinking skills for students. It fosters collaborative discussion, innovative solutions, and thoughtful analyses. 4. Engage in debates and discussionsParticipating in debates and discussions helps you articulate your thoughts clearly and consider opposing viewpoints. It challenges the critical thinking skills of students about the evidence presented, decoding arguments, and constructing logical reasoning. Look for debates and discussion opportunities in class, online forums, or extracurricular activities. 5. Look out for diverse sources of informationIn today's digital age, information is easily available from a variety of sources. Make it a habit to explore different opinions, perspectives, and sources of information. This not only broadens one's understanding of a subject but also helps in distinguishing between reliable and biased sources, honing the critical thinking skills of students. Unlock the power of critical thinking skills while enjoying a seamless student living experience!Book through amber today! 6. Practice problem-solvingTry engaging in challenging problems, riddles or puzzles that require critical thinking skills for students to solve. Whether it's solving mathematical equations, tackling complex scenarios in literature, or analysing data in science experiments, regular practice of problem-solving tasks sharpens your analytical skills. It enhances your ability to think critically under pressure. Nurturing critical thinking skills helps students with the tools to navigate the complexities of academia and beyond. By learning active listening, curiosity, creativity, and problem-solving, students can create a sturdy foundation for lifelong learning. By building upon all these skills, you’ll be an expert critical thinker in no time—and you’ll be ready to conquer all that college has to offer! Frequently Asked QuestionsWhat questions should i ask to be a better critical thinker, how can i sharpen critical thinking skills for students, how do i avoid bias, can i use my critical thinking skills outside of school, will critical thinking skills help students in their future careers. Your ideal student home & a flight ticket awaits Follow us on :  Related Posts.jpg) 10 Ways to Practice Mindful Eating 13 Breathtaking Places To Go For Spring Break In 2024 10 Best Clubs In Vancouver To Get Your Party On! Planning to Study Abroad ? Your ideal student accommodation is a few steps away! Please fill in your details below so we can find you a new home! We have got your response.jpg) amber © 2024. All rights reserved. 4.8/5 on Trustpilot Rated as "Excellent" • 4800+ Reviews by students Rated as "Excellent" • 4800+ Reviews by Students

UTC RAVE AlertCritical thinking and problem-solving, jump to: , what is critical thinking, characteristics of critical thinking, why teach critical thinking.

References and ResourcesWhen examining the vast literature on critical thinking, various definitions of critical thinking emerge. Here are some samples:

Perhaps the simplest definition is offered by Beyer (1995) : "Critical thinking... means making reasoned judgments" (p. 8). Basically, Beyer sees critical thinking as using criteria to judge the quality of something, from cooking to a conclusion of a research paper. In essence, critical thinking is a disciplined manner of thought that a person uses to assess the validity of something (statements, news stories, arguments, research, etc.). Back Wade (1995) identifies eight characteristics of critical thinking. Critical thinking involves asking questions, defining a problem, examining evidence, analyzing assumptions and biases, avoiding emotional reasoning, avoiding oversimplification, considering other interpretations, and tolerating ambiguity. Dealing with ambiguity is also seen by Strohm & Baukus (1995) as an essential part of critical thinking, "Ambiguity and doubt serve a critical-thinking function and are a necessary and even a productive part of the process" (p. 56). Another characteristic of critical thinking identified by many sources is metacognition. Metacognition is thinking about one's own thinking. More specifically, "metacognition is being aware of one's thinking as one performs specific tasks and then using this awareness to control what one is doing" (Jones & Ratcliff, 1993, p. 10 ). In the book, Critical Thinking, Beyer elaborately explains what he sees as essential aspects of critical thinking. These are:

Oliver & Utermohlen (1995) see students as too often being passive receptors of information. Through technology, the amount of information available today is massive. This information explosion is likely to continue in the future. Students need a guide to weed through the information and not just passively accept it. Students need to "develop and effectively apply critical thinking skills to their academic studies, to the complex problems that they will face, and to the critical choices they will be forced to make as a result of the information explosion and other rapid technological changes" (Oliver & Utermohlen, p. 1 ). As mentioned in the section, Characteristics of Critical Thinking , critical thinking involves questioning. It is important to teach students how to ask good questions, to think critically, in order to continue the advancement of the very fields we are teaching. "Every field stays alive only to the extent that fresh questions are generated and taken seriously" (Center for Critical Thinking, 1996a ). Beyer sees the teaching of critical thinking as important to the very state of our nation. He argues that to live successfully in a democracy, people must be able to think critically in order to make sound decisions about personal and civic affairs. If students learn to think critically, then they can use good thinking as the guide by which they live their lives. Teaching Strategies to Help Promote Critical ThinkingThe 1995, Volume 22, issue 1, of the journal, Teaching of Psychology , is devoted to the teaching critical thinking. Most of the strategies included in this section come from the various articles that compose this issue.

Other Reading

On the Internet

Walker Center for Teaching and Learning

Classroom Q&AWith larry ferlazzo. In this EdWeek blog, an experiment in knowledge-gathering, Ferlazzo will address readers’ questions on classroom management, ELL instruction, lesson planning, and other issues facing teachers. Send your questions to [email protected]. Read more from this blog. Integrating Critical Thinking Into the Classroom

(This is the second post in a three-part series. You can see Part One here .) The new question-of-the-week is: What is critical thinking and how can we integrate it into the classroom? Part One ‘s guests were Dara Laws Savage, Patrick Brown, Meg Riordan, Ph.D., and Dr. PJ Caposey. Dara, Patrick, and Meg were also guests on my 10-minute BAM! Radio Show . You can also find a list of, and links to, previous shows here. Today, Dr. Kulvarn Atwal, Elena Quagliarello, Dr. Donna Wilson, and Diane Dahl share their recommendations. ‘Learning Conversations’Dr. Kulvarn Atwal is currently the executive head teacher of two large primary schools in the London borough of Redbridge. Dr. Atwal is the author of The Thinking School: Developing a Dynamic Learning Community , published by John Catt Educational. Follow him on Twitter @Thinkingschool2 : In many classrooms I visit, students’ primary focus is on what they are expected to do and how it will be measured. It seems that we are becoming successful at producing students who are able to jump through hoops and pass tests. But are we producing children that are positive about teaching and learning and can think critically and creatively? Consider your classroom environment and the extent to which you employ strategies that develop students’ critical-thinking skills and their self-esteem as learners. Development of self-esteem One of the most significant factors that impacts students’ engagement and achievement in learning in your classroom is their self-esteem. In this context, self-esteem can be viewed to be the difference between how they perceive themselves as a learner (perceived self) and what they consider to be the ideal learner (ideal self). This ideal self may reflect the child that is associated or seen to be the smartest in the class. Your aim must be to raise students’ self-esteem. To do this, you have to demonstrate that effort, not ability, leads to success. Your language and interactions in the classroom, therefore, have to be aspirational—that if children persist with something, they will achieve. Use of evaluative praise Ensure that when you are praising students, you are making explicit links to a child’s critical thinking and/or development. This will enable them to build their understanding of what factors are supporting them in their learning. For example, often when we give feedback to students, we may simply say, “Well done” or “Good answer.” However, are the students actually aware of what they did well or what was good about their answer? Make sure you make explicit what the student has done well and where that links to prior learning. How do you value students’ critical thinking—do you praise their thinking and demonstrate how it helps them improve their learning? Learning conversations to encourage deeper thinking We often feel as teachers that we have to provide feedback to every students’ response, but this can limit children’s thinking. Encourage students in your class to engage in learning conversations with each other. Give as many opportunities as possible to students to build on the responses of others. Facilitate chains of dialogue by inviting students to give feedback to each other. The teacher’s role is, therefore, to facilitate this dialogue and select each individual student to give feedback to others. It may also mean that you do not always need to respond at all to a student’s answer. Teacher modelling own thinking We cannot expect students to develop critical-thinking skills if we aren’t modeling those thinking skills for them. Share your creativity, imagination, and thinking skills with the students and you will nurture creative, imaginative critical thinkers. Model the language you want students to learn and think about. Share what you feel about the learning activities your students are participating in as well as the thinking you are engaging in. Your own thinking and learning will add to the discussions in the classroom and encourage students to share their own thinking. Metacognitive questioning Consider the extent to which your questioning encourages students to think about their thinking, and therefore, learn about learning! Through asking metacognitive questions, you will enable your students to have a better understanding of the learning process, as well as their own self-reflections as learners. Example questions may include:

‘Adventures of Discovery’Elena Quagliarello is the senior editor of education for Scholastic News , a current events magazine for students in grades 3–6. She graduated from Rutgers University, where she studied English and earned her master’s degree in elementary education. She is a certified K–12 teacher and previously taught middle school English/language arts for five years: Critical thinking blasts through the surface level of a topic. It reaches beyond the who and the what and launches students on a learning journey that ultimately unlocks a deeper level of understanding. Teaching students how to think critically helps them turn information into knowledge and knowledge into wisdom. In the classroom, critical thinking teaches students how to ask and answer the questions needed to read the world. Whether it’s a story, news article, photo, video, advertisement, or another form of media, students can use the following critical-thinking strategies to dig beyond the surface and uncover a wealth of knowledge. A Layered Learning Approach Begin by having students read a story, article, or analyze a piece of media. Then have them excavate and explore its various layers of meaning. First, ask students to think about the literal meaning of what they just read. For example, if students read an article about the desegregation of public schools during the 1950s, they should be able to answer questions such as: Who was involved? What happened? Where did it happen? Which details are important? This is the first layer of critical thinking: reading comprehension. Do students understand the passage at its most basic level? Ask the Tough Questions The next layer delves deeper and starts to uncover the author’s purpose and craft. Teach students to ask the tough questions: What information is included? What or who is left out? How does word choice influence the reader? What perspective is represented? What values or people are marginalized? These questions force students to critically analyze the choices behind the final product. In today’s age of fast-paced, easily accessible information, it is essential to teach students how to critically examine the information they consume. The goal is to equip students with the mindset to ask these questions on their own. Strike Gold The deepest layer of critical thinking comes from having students take a step back to think about the big picture. This level of thinking is no longer focused on the text itself but rather its real-world implications. Students explore questions such as: Why does this matter? What lesson have I learned? How can this lesson be applied to other situations? Students truly engage in critical thinking when they are able to reflect on their thinking and apply their knowledge to a new situation. This step has the power to transform knowledge into wisdom. Adventures of Discovery There are vast ways to spark critical thinking in the classroom. Here are a few other ideas:

Critical thinking has the power to launch students on unforgettable learning experiences while helping them develop new habits of thought, reflection, and inquiry. Developing these skills prepares students to examine issues of power and promote transformative change in the world around them.  ‘Quote Analysis’Dr. Donna Wilson is a psychologist and the author of 20 books, including Developing Growth Mindsets , Teaching Students to Drive Their Brains , and Five Big Ideas for Effective Teaching (2 nd Edition). She is an international speaker who has worked in Asia, the Middle East, Australia, Europe, Jamaica, and throughout the U.S. and Canada. Dr. Wilson can be reached at [email protected] ; visit her website at www.brainsmart.org . Diane Dahl has been a teacher for 13 years, having taught grades 2-4 throughout her career. Mrs. Dahl currently teaches 3rd and 4th grade GT-ELAR/SS in Lovejoy ISD in Fairview, Texas. Follow her on Twitter at @DahlD, and visit her website at www.fortheloveofteaching.net : A growing body of research over the past several decades indicates that teaching students how to be better thinkers is a great way to support them to be more successful at school and beyond. In the book, Teaching Students to Drive Their Brains , Dr. Wilson shares research and many motivational strategies, activities, and lesson ideas that assist students to think at higher levels. Five key strategies from the book are as follows:

Below are two lessons that support critical thinking, which can be defined as the objective analysis and evaluation of an issue in order to form a judgment. Mrs. Dahl prepares her 3rd and 4th grade classes for a year of critical thinking using quote analysis . During Native American studies, her 4 th grade analyzes a Tuscarora quote: “Man has responsibility, not power.” Since students already know how the Native Americans’ land had been stolen, it doesn’t take much for them to make the logical leaps. Critical-thought prompts take their thinking even deeper, especially at the beginning of the year when many need scaffolding. Some prompts include:

Analyzing a topic from occupational points of view is an incredibly powerful critical-thinking tool. After learning about the Mexican-American War, Mrs. Dahl’s students worked in groups to choose an occupation with which to analyze the war. The chosen occupations were: anthropologist, mathematician, historian, archaeologist, cartographer, and economist. Then each individual within each group chose a different critical-thinking skill to focus on. Finally, they worked together to decide how their occupation would view the war using each skill. For example, here is what each student in the economist group wrote:

This was the first time that students had ever used the occupations technique. Mrs. Dahl was astonished at how many times the kids used these critical skills in other areas moving forward.  Thanks to Dr. Auwal, Elena, Dr. Wilson, and Diane for their contributions! Please feel free to leave a comment with your reactions to the topic or directly to anything that has been said in this post. Consider contributing a question to be answered in a future post. You can send one to me at [email protected] . When you send it in, let me know if I can use your real name if it’s selected or if you’d prefer remaining anonymous and have a pseudonym in mind. You can also contact me on Twitter at @Larryferlazzo . Education Week has published a collection of posts from this blog, along with new material, in an e-book form. It’s titled Classroom Management Q&As: Expert Strategies for Teaching . Just a reminder; you can subscribe and receive updates from this blog via email (The RSS feed for this blog, and for all Ed Week articles, has been changed by the new redesign—new ones won’t be available until February). And if you missed any of the highlights from the first nine years of this blog, you can see a categorized list below.

I am also creating a Twitter list including all contributors to this column . The opinions expressed in Classroom Q&A With Larry Ferlazzo are strictly those of the author(s) and do not reflect the opinions or endorsement of Editorial Projects in Education, or any of its publications. Sign Up for EdWeek UpdateEdweek top school jobs.  Sign Up & Sign In Distance LearningUsing technology to develop students’ critical thinking skills. by Jessica Mansbach What Is Critical Thinking?Critical thinking is a higher-order cognitive skill that is indispensable to students, readying them to respond to a variety of complex problems that are sure to arise in their personal and professional lives. The cognitive skills at the foundation of critical thinking are analysis, interpretation, evaluation, explanation, inference, and self-regulation. When students think critically, they actively engage in these processes:

To create environments that engage students in these processes, instructors need to ask questions, encourage the expression of diverse opinions, and involve students in a variety of hands-on activities that force them to be involved in their learning. Types of Critical Thinking SkillsInstructors should select activities based on the level of thinking they want students to do and the learning objectives for the course or assignment. The chart below describes questions to ask in order to show that students can demonstrate different levels of critical thinking.

*Adapted from Brown University’s Harriet W Sheridan Center for Teaching and Learning Using Online Tools to Teach Critical Thinking SkillsOnline instructors can use technology tools to create activities that help students develop both lower-level and higher-level critical thinking skills.

Pulling it All TogetherCritical thinking is an invaluable skill that students need to be successful in their professional and personal lives. Instructors can be thoughtful and purposeful about creating learning objectives that promote lower and higher-level critical thinking skills, and about using technology to implement activities that support these learning objectives. Below are some additional resources about critical thinking.  Additional ResourcesCarmichael, E., & Farrell, H. (2012). Evaluation of the Effectiveness of Online Resources in Developing Student Critical Thinking: Review of Literature and Case Study of a Critical Thinking Online Site. Journal of University Teaching and Learning Practice , 9 (1), 4. Lai, E. R. (2011). Critical thinking: A literature review. Pearson’s Research Reports , 6 , 40-41. Landers, H (n.d.). Using Peer Teaching In The Classroom. Retrieved electronically from https://tilt.colostate.edu/TipsAndGuides/Tip/180 Lynch, C. L., & Wolcott, S. K. (2001). Helping your students develop critical thinking skills (IDEA Paper# 37. In Manhattan, KS: The IDEA Center. Mandernach, B. J. (2006). Thinking critically about critical thinking: Integrating online tools to Promote Critical Thinking. Insight: A collection of faculty scholarship , 1 , 41-50. Yang, Y. T. C., & Wu, W. C. I. (2012). Digital storytelling for enhancing student academic achievement, critical thinking, and learning motivation: A year-long experimental study. Computers & Education , 59 (2), 339-352. Insight Assessment: Measuring Thinking Worldwide http://www.insightassessment.com/ Michigan State University’s Office of Faculty & Organizational Development, Critical Thinking: http://fod.msu.edu/oir/critical-thinking The Critical Thinking Community http://www.criticalthinking.org/pages/defining-critical-thinking/766 Related PostsWays to Use Panopto in Online Courses Enter to Win an iRig Lavalier Microphone (by IK Multimedia) Behind the Scenes of a DL Video Selecting a Video Style 9 responses to “ Using Technology To Develop Students’ Critical Thinking Skills ”This is a great site for my students to learn how to develop critical thinking skills, especially in the STEM fields. Great tools to help all learners at all levels… not everyone learns at the same rate. Thanks for sharing the article. Is there any way to find tools which help in developing critical thinking skills to students? Technology needs to be advance to develop the below factors: Understand the links between ideas. Determine the importance and relevance of arguments and ideas. Recognize, build and appraise arguments. Excellent share! Can I know few tools which help in developing critical thinking skills to students? Any help will be appreciated. Thanks!

Brilliant post. Will be sharing this on our Twitter (@refthinking). I would love to chat to you about our tool, the Thinking Kit. It has been specifically designed to help students develop critical thinking skills whilst they also learn about the topics they ‘need’ to. Leave a Reply Cancel replyYour email address will not be published. Required fields are marked * Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment. Insert/edit linkEnter the destination URL Or link to existing content The Edvocate

Teaching Students About the League Cup: A Comprehensive GuideTeaching students about negative heat in endothermic and exothermic reactions, teaching students about the school of athens: enlightening the minds of tomorrow, teaching students about girona: a cultural and historical adventure, teaching students about donald trump’s wiki page: a comprehensive resource, teaching students about the oldest hockey team, teaching students about st. francis of assisi: enlightening young minds, teaching students about piping: a comprehensive guide, teaching students about sand sharks: a dive into the mysterious world of these intriguing creatures, teaching students about the age of millennials: a new approach to education, strategies and methods to teach students problem solving and critical thinking skills.  The ability to problem solve and think critically are two of the most important skills that PreK-12 students can learn. Why? Because students need these skills to succeed in their academics and in life in general. It allows them to find a solution to issues and complex situations that are thrown there way, even if this is the first time they are faced with the predicament. Okay, we know that these are essential skills that are also difficult to master. So how can we teach our students problem solve and think critically? I am glad you asked. In this piece will list and discuss strategies and methods that you can use to teach your students to do just that.

A method of problem-solving in which a problem is compared to similar problems in nature or other settings, providing solutions that could potentially be applied.

A technique used to encourage creative thinking in which the parts of a subject, problem, or task are listed, and then ways to change those component parts are examined.

A technique used to encourage creative thinking in which the parts of a subject, problem, or task are listed, and then options for changing or improving each part are considered.

A technique used to encourage creative thinking in which the parts of a subject, problem or task listed and then the problem solver uses analogies to other contexts to generate and consider potential solutions.

A technique used to encourage creative problem solving which extends on attribute transferring. A matrix is created, listing concrete attributes along the x-axis, and the ideas from a second attribute along with the y-axis, yielding a long list of idea combinations. SCAMPER stands for Substitute, Combine, Adapt, Modify-Magnify-Minify, Put to other uses, and Reverse or Rearrange. It is an idea checklist for solving design problems.

A problem-solving technique in which an individual is asked to consider the ways problems of this type are solved in nature.

A problem-solving technique in which an individual is challenged to become part of the problem to view it from a new perspective and identify possible solutions.

A problem-solving process in which participants are asked to consider outlandish, fantastic or bizarre solutions which may lead to original and ground-breaking ideas.

A problem-solving technique in which participants are challenged to generate a two-word phrase related to the design problem being considered and that appears self-contradictory. The process of brainstorming this phrase can stimulate design ideas.

An activity in which problem solvers are asked to identify the next steps to implement their creative ideas. This step follows the idea generation stage and the narrowing of ideas to one or more feasible solutions. The process helps participants to view implementation as a viable next step.

Skills aimed at aiding students to be critical, logical, and evaluative thinkers. They include analysis, comparison, classification, synthesis, generalization, discrimination, inference, planning, predicting, and identifying cause-effect relationships. Can you think of any additional problems solving techniques that teachers use to improve their student’s problem-solving skills? The 4 Types of BrainstormingFeeling lethargic it may all that screen .... Matthew LynchRelated articles more from author.  Establishing Order In Your Classroom: Five Common Approaches to Classroom Management 19 Strategies to Help Students to Respond Appropriately to Constructive Criticism Dear First-Year Teacher, Hold on, It Gets Better It’s ok to date new technology, you don’t have to marry it! 24 Strategies to Teach Students Not to Retaliate 9 Challenges Our Students Face in School Today Part I: Poverty & Homeless Families

How to Improve Student Critical Thinking Skills

Home Educators Blog Why are Student Critical Thinking Skills So Essential?There are many skills that are essential for students to have in order to better themselves and their learning. Many of these skills should be taught at an early age and practiced as they grow and develop. Skills such as problem-solving , collaboration , and critical thinking are vital to students inside and outside the classroom. Critical thinking skills are especially important for students to develop. Students need critical thinking skills in many situations such as trying to solve a math problem, figuring out the best way to go from their house to work, or solving any type of puzzle. These skills are essential to help students learn:

So, how do you know if critical thinking is happening in your classroom? Some of the most obvious ways you will know if your students have acquired this skill would be the following observable actions.

Discussions/DebateClass discussions are an important method in developing students’ critical thinking skills. Providing students with a safe forum in which to express their thoughts and ideas empowers them to think deeply about issues and vocalize their thoughts. For example, an English teacher might provide pre-reading exercises for students to complete for homework. These questions can then be used as a springboard to generate a group discussion . To challenge the students more, the questions could be controversial in nature to allow for passionate students to think critically on an issue as they express their ideas. For instance, before teaching Of Mice and Men by John Steinbeck, the teacher may ask questions like:

While these questions ultimately are relevant to the text, before reading the novel, students must interpret these questions from a personal standpoint and evaluate their own feelings and philosophies. Once the students complete the questions, there can be a class discussion or debate on each topic. For the discussion to succeed, the teacher must be an impartial facilitator to their discussion, often playing the proverbial “devil’s advocate” to keep the conversation dynamic and engaging. This discussion approach allows students to not only voice their opinions but also to hear the opinions of their classmates and further assess their own understanding of the topics. This method allows for critical thinking both before the exercise as students complete the questions and then during the exercise as they debate their classmates in a group dynamic. In addition, the questions posed for the group discussion lead directly to another tool for developing critical thinking skills: making real-world connections. Real-World ConnectionsIt is imperative as a teacher to push students to make real-world and personal connections to the material being covered. If students make these connections, they are more invested in the subject matter and more inclined to analyze and think critically about their work. As an example, a teacher may take a text written 80 years ago and ask the students to modernize the work; they can keep the same themes and conflicts yet bring the work to a modern-day setting. This exercise allows students to better relate to the text and understand how they might react if put into the same situations as many characters. Another example is asking students to identify specific mathematical topics in areas in their lives that do not include the classroom. Something such as slope can be identified with how students can go from one floor of the school building to the next. Geometric figures are demonstrated with any building that exists. Specific mathematical or physical laws can happen at any point of their lives. When students are able to identify these instances, it helps them to make a better connection to the learning. These connections force students to examine and analyze on a more critical level because suddenly the material is much more relatable. These real-world connections challenge students to develop the vital critical thinking skills. Has the Pandemic Affected Student Critical Thinking Skills?After navigating through two years of the pandemic, students need to develop critical thinking skills now more than ever. If the pandemic has taught us anything, it is that there is no substitute for in-person classroom instruction. As a result of online learning, many students lost the ability to think critically as many of the assignments didn’t allow for that type of learning. In many ways, students forgot how to be students, and teachers forgot how to be teachers. With the height of the pandemic now behind us, it is imperative that we rebuild critical thinking skills and again teach students how to approach material in an analytical sense. How to Improve Critical Thinking Skills in StudentsTeachers can challenge their students to discover information about the topic being discussed and gain pre-knowledge as mentioned in the example above. Suppose students can access knowledge prior to the lesson or learning new content. In that case, it can help them to develop the necessary skills for the lesson as well as give them the confidence to learn and practice the newest material. This helps to develop their critical thinking as well as have a better connection to the content. There are many ways that teachers can help develop student critical thinking skills. Safe Learning EnvironmentsOne of the ways is to create a safe learning place in which students feel comfortable to ask questions. When students ask questions, it helps them to better understand the content and analyze the information better. Active ParticipationAnother way that students can develop their critical thinking skills is to be active participants in the lesson and help to collaborate. If a teacher can create an atmosphere where the students work together, participate in the learning , and learn from one another, then students can begin to develop these skills. Connections with Previous KnowledgeStudents can use prior knowledge from previously learned material to make connections to the present topics. If students can build off what they already know and apply it to what they are currently learning, it can help them to see the connections as well as analyze the newest information. Students, also, can work backwards to solve problems. Students can take the question, example, and the answer and work backwards to discover how to go from the start to the end. Mistakes and Learning from ThemAlthough some teachers do not like to give the answers to students, this process can actually help them to evaluate the problem better and to learn how to solve it moving forward. One last way students can help develop their critical thinking skills is to take chances, use the guess-and-check method when in doubt, and just try to discover a possible solution. So often, students want to be right, and they want to know that they are right; this happens often at the secondary level . Many of these students are scared to fail and do not want to take risks. Teaching students that it is okay to explore and make mistakes can help them improve their critical thinking skills and confidence. Life is about discovering and exploring and when the students understand that those are important skills to have in life, it can help them to analyze better within the classroom setting. Instructional StrategiesThink about the instructional strategies that you use most often — I am referring to your “go to” tools in your toolbox of instructional strategies. Do these strategies develop deeper learning competencies in your students? For instance, do your students have opportunities to use student choice and voice when working on assignments? Students should be able to create their own projects, define goals , develop their learning plan, and communicate their achievements to a broader audience. When students can make choices and direct their own learning, they become more dedicated and engaged students. An instructional strategy that develops deeper learning competencies (especially critical thinking) is project-based learning . Student critical thinking skills are many of the important skills they should develop to help them in different aspects of their lives. Through being challenged and encouraged to take different approaches, students can begin to learn and develop these skills. Through learning how these skills can be applied in the classroom as well as the real-world, it helps them to understand better. This not only helps them within the classroom setting but also for life after school. Looking to advance your education and impact as a teacher? Check out our educator’s blog and 190+ available masters, doctorates, endorsements, and certifications to advance your career today!