What Does It Mean To Be Human? 300 Years of Definitions and Reflections

By maria popova.

Decades before women sought liberation in the bicycle or their biceps , a more rudimentary liberation was at stake. The book opens with a letter penned in 1872 by an anonymous author identified simply as “An Earnest Englishwoman,” a letter titled “Are Women Animals?” by the newspaper editor who printed it:

Sir, — Whether women are the equals of men has been endlessly debated; whether they have souls has been a moot point; but can it be too much to ask [for a definitive acknowledgement that at least they are animals?… Many hon. members may object to the proposed Bill enacting that, in statutes respecting the suffrage, ‘wherever words occur which import the masculine gender they shall be held to include women;’ but could any object to the insertion of a clause in another Act that ‘whenever the word “animal” occur it shall be held to include women?’ Suffer me, thorough your columns, to appeal to our 650 [parliamentary] representatives, and ask — Is there not one among you then who will introduce such a motion? There would then be at least an equal interdict on wanton barbarity to cat, dog, or woman… Yours respectfully, AN EARNEST ENGLISHWOMAN

The broader question at the heart of the Earnest Englishwoman’s outrage, of course, isn’t merely about gender — “women” could have just as easily been any other marginalized group, from non-white Europeans to non-Westerners to even children, or a delegitimized majority-politically-treated-as-minority more appropriate to our time, such as the “99 percent.” The question, really, is what entitles one to humanness.

But seeking an answer in the ideology of humanism , Bourke is careful to point out, is hasty and incomplete:

The humanist insistence on an autonomous, willful human subject capable of acting independently in the world was based on a very particular type of human. Human civilization had been forged in the image of the male, white, well-off, educated human. Humanism installed only some humans at the centre of the universe. It disparaged ‘the woman,’ ‘the subaltern’ and ‘the non-European’ even more than ‘the animal.’ As a result, it is hardly surprising that many of these groups rejected the idea of a universal and straightforward essence of ‘the human’, substituting something much more contingent, outward-facing and complex. To rephrase Simone de Beauvoir’s inspired conclusion about women, one is not born, but made , a human.

Bourke also admonishes against seeing the historical trend in paradigms about humanness as linear, as shifting “ from the theological towards the rationalist and scientific” or “ from humanist to post-humanist.” How, then, are we to examine the “porous boundary between the human and the animal”?

In complex and sometimes contradictory ways, the ideas, values and practices used to justify the sovereignty of a particular understanding of ‘the human’ over the rest of sentient life are what create society and social life. Perhaps the very concept of ‘culture’ is an attempt to differentiate ourselves from our ‘creatureliness,’ our fleshly vulnerability.

(Cue in 15 years of leading scientists’ meditations on “culture” .)

Bourke goes on to explore history’s varied definitions of what it means to be human, which have used a wide range of imperfect, incomplete criteria — intellectual ability, self-consciousness, private property, tool-making, language, the possession of a soul, and many more.

For Aristotle , writing in the 4th century B.C., it meant having a telos — an appropriate end or goal — and to belong to a polis where “man” could truly speak:

…the power of speech is intended to set forth the expedient and inexpedient, and therefore likewise the just and the unjust. And it is a characteristic of man that he alone has any sense of good and evil, or just and unjust, and the like, and the association of living beings who have this sense makes a family and a state.

In the early 17th century, René Descartes , whose famous statement “Cogito ergo sum” (“I think, therefore I am”) implied only humans possess minds, argued animals were “automata” — moving machines, driven by instinct alone:

Nature which acts in them according to the disposition of their organs, as one sees that a clock, which is made up of only wheels and springs can count the hours and measure time more exactly than we can with all our art.

For late 18th-century German philosopher Immanuel Kant , rationality was the litmus test for humanity, embedded in his categorical claim that the human being was “an animal endowed with the capacity of reason”:

[The human is] markedly distinguished from all other living beings by his technical predisposition for manipulating things (mechanically joined with consciousness), by his pragmatic predisposition (to use other human beings skillfully for his purposes), and by the moral predisposition in his being (to treat himself and others according to the principle of freedom under the laws.)

In The Descent of Man , Darwin reflected:

The difference in mind between man and the higher animals, great as it is, is certainly one of degree and not of kind. We have seen that the senses and intuitions, the various emotions and faculties, such as love, memory, attention, curiosity, imitation, reason, etc., of which man boasts, may be found in an incipient, or even sometimes in a well-developed condition, in the lower animals.

(For more on Darwin’s fascinating studies of emotion, don’t forget Darwin’s Camera .)

Darwin’s concern was echoed quantitatively by Jared Diamond in 1990s when, in The Third Chimpanzee , he wondered how the 2.9% genetic difference between two kids of birds or the 2.2% difference between two gibbons made for a different species, but the 1.6% difference between humans and chimpanzees makes a different genus.

In the 1930s, Bertrand Lloyd , who penned Humanitarianism and Freedom , observed a difficult paradox of any definition:

Deny reason to animals, and you must equally deny it to infants; affirm the existence of an immortal soul in your baby or yourself, and you must at least have the grace to allow something of the kind to your dog.

In 2001, Jacques Derrida articulated a similar concern:

None of the traits by which the most authorized philosophy or culture has thought it possible to recognize this ‘proper of man’ — none of them is, in all rigor, the exclusive reserve of what we humans call human. Either because some animals also possess such traits, or because man does not possess it as surely as is claimed.

Curiously, Bourke uses the Möbius strip as the perfect metaphor for deconstructing the human vs. animal dilemma. Just as the one-sided surface of the strip has “no inside or outside; no beginning or end; no single point of entry or exit; no hierarchical ladder to clamber up or slide down,” so “the boundaries of the human and the animal turn out to be as entwined and indistinguishable as the inner and outer sides of a Möbius strip.” Bourke points to Derrida’s definition as the most rewarding, calling him “the philosopher of the Möbius strip.”

Ultimately, What It Means to Be Human is less an answer than it is an invitation to a series of questions, questions about who and what we are as a species, as souls, and as nodes in a larger complex ecosystem of sentient beings. As Bourke poetically puts it,

Erasing the awe-inspiring variety of sentient life impoverishes all our lives.

And whether this lens applies to animals or social stereotypes , one thing is certain: At a time when the need to celebrate both our shared humanity and our meaningful differences is all the more painfully evident , the question of what makes us human becomes not one of philosophy alone but also of politics, justice, identity, and every fiber of existence that lies between.

HT my mind on books

— Published December 9, 2011 — https://www.themarginalian.org/2011/12/09/what-it-means-to-be-human-joanna-bourke/ —

www.themarginalian.org

PRINT ARTICLE

Email article, filed under, books culture history philosophy politics science, view full site.

The Marginalian participates in the Bookshop.org and Amazon.com affiliate programs, designed to provide a means for sites to earn commissions by linking to books. In more human terms, this means that whenever you buy a book from a link here, I receive a small percentage of its price, which goes straight back into my own colossal biblioexpenses. Privacy policy . (TLDR: You're safe — there are no nefarious "third parties" lurking on my watch or shedding crumbs of the "cookies" the rest of the internet uses.)

What does it mean to be human? 7 famous philosophers answer

What does it mean to be human? Such a fundamental question to our existence.

This question tends to arise in the face of a moral dilemma or existential crisis, or when trying to find yourself .

What’s more, it’s usually followed by more questions:

What separates us from other species? What is it that drives us to do what we do? What makes us unique?

The answers are never straightforward. Even at this age of modernity and intellectual freedom, we may not be close to any concrete answers. For centuries, the world’s philosophers have made it their work to find them.

Yet the answers remain as diverse and inconclusive as ever.

What does it truly mean to be human ?

Read ahead to find out how 7 of the world’s most famous philosophers answer this question.

“If a human being is a social creature, then he can develop only in the society.”

Karl Marx is known for writing the Communist Manifesto alongside philosopher and social scientist Friedrich Engels. He was among the foremost advocates of communism in 19th century Europe.

Although he is famous for his socialism, he remains one of the most prominent modern philosophical thinkers. Aside from sparking a vast set of social movements during his time, he has managed to shape the world’s views on capitalism, politics, economics, sociology – and yes, even philosophy.

What are his views on human nature?

“All history is nothing but a continuous transformation of human nature.”

Marx believed that human nature is hugely shaped by our history. He believed that the way we view things – morality, social construct , need fulfillment – is historically contingent in much the same ways our society is.

Of course, his theory on human nature also suggests that humanity’s progress is hindered by capitalism, particularly about labor. As long as we objectify our ideas and satisfy our needs, labor will express our human nature and changes it as well.

“All that belongs to human understanding, in this deep ignorance and obscurity, is to be skeptical, or at least cautious; and not to admit of any hypothesis, whatsoever; much less, of any which is supported by no appearance of probability.”

David Hume was an empiricist . He believed that all human ideas have roots from sense impressions. Meaning, even if we imagine a creature that does not exist, your imagination of it still consists of things you’ve sensed in the real world.

Why is this relevant to being human?

According to Hume, in order to arrange these impressions, we use different mental processes that are fundamentally part of being human. These are Resemblance, Contiguity in time or place, and Cause and Effect.

“‘Tis evident, that all the sciences have a relation, more or less, to human nature … Even Mathematics, Natural Philosophy, and Natural Religion, are in some measure dependent on the science of Man.”

Hume further believes that our own perception of truth, each of us, no matter how different, exists. When humans seek truth, they come into moments of realization. Small moments of realization lead to a sense of happiness of fulfillment. Big moments of realization, one the other hand, are truly what makes us human.

To Hume, It is when we experience these crucial consciousness-altering experiences, that we can finally say, with certainty, what it means to be human.

Ludwig Wittgenstein

“The limits of my language mean the limits of my world. Whereof one cannot speak, thereof one must be silent. The world is everything that is the case.”

There is, perhaps, no other modern philosopher as deeply enigmatic as Ludwig Wittgenstein. His philosophy can be turned sideways, and you’ll still find it both authoritative and obscure.

His philosophy about humanity can be interpreted in many ways. But the gist is still compelling. Let’s digest what he thinks from his one and only book Tractatus-Logico-Philosophicus (1921.)

What it means to be human, for Wittgenstein, is our ability to think consciously. We are active, embodied speakers. Before we communicate, we first need to have something to communicate with. We have to create and distinguish true and false thoughts about the world around us, to be able to think about things – combinations of things.

Related Stories from Ideapod

8 subtle signs you’re a deep thinker, according to psychology, 8 signs you have a good quality heart, according to psychology, if a woman uses these 8 phrases in a conversation, she hasn’t grown up emotionally.

These conscious combinations of thoughts is what Wittgenstein calls “states of affairs.”

“The world is the totality of facts, not of things”

To be human is to think – true, false – it does not truly matter.

Friedrich Nietzsche

“The hour-hand of life. Life consists of rare, isolated moments of the greatest significance, and of innumerably many intervals, during which at best the silhouettes of those moments hover about us. Love, springtime, every beautiful melody, mountains, the moon, the sea-all these speak completely to the heart but once, if in fact they ever do get a chance to speak completely. For many men do not have those moments at all, and are themselves intervals and intermissions in the symphony of real life.”

Friedrich Nietzsche – yet another revolutionary philosopher. He is best known for his book, Human, All Too Human: A Book for Free Spirits.

Amongst other philosophers who write unpalatable and obscure ideologies, Nietzche is witty, eloquent, and brutally honest. And even poetic. He is a philosopher who scrutinizes human nature, while offering concrete advice on how to deal with it.

What does he think about humanity and what it means?

“The advantages of psychological observation. That meditating on things human, all too human (or, as the learned phrase goes, “psychological observation”) is one of the means by which man can ease life’s burden; that by exercising this art, one can secure presence of mind in difficult situations and entertainment amid boring surroundings; indeed, that from the thorniest and unhappiest phases of one’s own life one can pluck maxims and feel a bit better thereby.”

For Nietzsche, our awareness gives meaning to humanity. We are capable of what he calls psychological observations, the ability to see things from an analytical perspective. With this, we, as humans, can control the narrative of our existence.

“For all good and evil, whether in the body or in human nature, originates … in the soul, and overflows from thence, as from the head into the eyes.”

You really didn’t think we’d skip Plato in this list, did you? After all, there’s his Theory of Human Nature.

Plato believed in souls.

He believed that humans have both immaterial mind (soul) and material body . That our souls exist before birth and after death. And it is composed of 1. reason ; 2. appetite (physical urges); and will (emotion, passion, spirit.)

For Plato, the soul is the source for everything we feel – love, anguish, anger, ambition, fear. And most of our mental conflict as humans are caused by these aspects not being in harmony.

“Man – a being in search of meaning.”

Plato also believed that human nature is social. At our core, we are not self-sufficient. We need others. We derive satisfaction from our social interactions. That in truth, we derive meaning from our relationships.

Immanuel Kant

“Intuition and concepts constitute… the elements of all our knowledge, so that neither concepts without an intuition in some way corresponding to them, nor intuition without concepts, can yield knowledge.”

Immanuel Kant is widely regarded as one of the most influential western philosophers of all time. His ideologies were about religion, politics, and eternal peace. But most importantly, he was a philosopher of human autonomy.

Kant believed that as humans, we are determined and capable of knowledge, and the ability to act on it, without depending on anyone else, even religion or some divine intervention.

Humans’ perception of knowledge, according to him, are “sensory states caused by physical objects and events outside the mind, and the mind’s activity in organizing these data under concepts …”

Hence, Kant believes that we interact with the world based on our perception of it. We are human because of our reason. Like other species, we do things, we act. But unlike them, we give reasons for our actions. And that, for Kant, is essentially what it means to be human.

“All our knowledge begins with the senses, proceeds then to the understanding, and ends with reason. There is nothing higher than reason.”

Thomas Aquinas

“We can’t have full knowledge all at once. We must start by believing; then afterwards we may be led on to master the evidence for ourselves.”

Like Plato, Thomas Aquinas was a dualist , who believed that human beings have both a body and a soul.

But unlike Kant who believed it is our intellect that gives us meaning, Aquinas believed the reverse. For him, we absorb knowledge through our sense, and the intellect processes it later, and more gradually, through our human experiences.

Aquinas believed that we are the only beings in existence, that can perceive both matter and spirit. We don’t just exist in this world – we can interpret it, scrutinize it, derive meaning from it, and make decisions about it. It is our intellect that transcends us from simply existing, to actually doing with freedom, with limitless imagination.

What do you think?

You don’t need to be a philosopher to come to your own conclusions. For you, what does it mean to be human? Is it compassion, empathy, logic, our consciousness?

In this world of technology, social media, and advanced scientific discoveries, it’s important to keep asking this crucial question. Don’t let all the noise distracting you from reflection – why do we exist? What does it all even mean? What can we bring into this marvelous existence? Let us know by joining in on the discussion below.

Enhance your experience of Ideapod and join Tribe, our community of free thinkers and seekers.

Related articles

- Lucas Graham

People who struggle with low self-esteem often display these 8 subtle behaviors (without realizing it)

- Ethan Sterling

- Isabella Chase

8 phrases only toxic people use, according to psychology

- Ava Sinclair

9 subtle body language gestures to avoid if you want to look confident and strong

Most read articles.

6 signs a woman really loves you but isn’t sure if you’re the one, according to psychology

People who care about the environment practice these 8 tips

People who care about the planet often practice these 7 recycling habits

If you want to make a real impact, start recycling these 8 everyday items

Most loved zodiac signs: All 12 signs ranked by popularity

Get our articles.

Ideapod news, articles, and resources, sent straight to your inbox every month.

ABOUT IDEAPOD

Social media.

What Does It Mean to Be Human?

We can’t turn to science for an answer..

Posted May 16, 2012 | Reviewed by Matt Huston

What does it mean to be human? Or, putting the point a bit more precisely, what are we saying about others when we describe them as human? Answering this question is not as straightforward as it might appear. Minimally, to be human is to be one of us, but this begs the question of the class of creatures to which “us” refers.

Can’t we turn to science for an answer? Not really. Some paleoanthropologists identify the category of the human with the species Homo sapiens , others equate it with the whole genus Homo , some restrict it to the subspecies Homo sapiens sapiens , and a few take it to encompass the entire hominin lineage. These differences of opinion are not due to a scarcity of evidence. They are due to the absence of any conception of what sort of evidence can settle the question of which group or groups of primates should be counted as human. Biologists aren’t equipped to tell us whether an organism is a human organism because “human” is a folk category rather a scientific one.

Some folk-categories correspond more or less precisely to scientific categories. To use a well-worn example, the folk category “water” is coextensive with the scientific category “H2O.” But not every folk category is even approximately reducible to a scientific one. Consider the category “weed.” Weeds don’t have any biological properties that distinguish them from non-weeds. In fact, one could know everything there is to know biologically about a plant, but still not know that it is a weed. So, at least in this respect, being human is more like being a weed than it is like being water.

If this sounds strange to you, it is probably because you are already committed to one or another conception of the human (for example, that all and only members of Homo sapiens are human). However, claims like “an animal is human only if it is a member of the species Homo sapiens ” are stipulated rather than discovered. In deciding that all and only Homo sapiens are humans, one is expressing a preference about where the boundary separating humans from non-humans should be drawn, rather than discovering where such a boundary lays.

If science can’t give us an account of the human, why not turn to the folk for an answer?

Unfortunately, this strategy multiplies the problem rather than resolving it. When we look at how ordinary people have used the term “human” and its equivalents across cultures and throughout the span of history, we discover that often (maybe even typically) members of our species are explicitly excluded from the category of the human. It’s well-known that the Nazis considered Jews to be non-human creatures ( Untermenschen ), and somewhat less well-known that fifteenth-century Spanish colonists took a similar stance towards the indigenous inhabitants of the Caribbean islands, as did North Americans toward enslaved Africans (my 2011 book Less Than Human: Why We Demean, Enslave, and Exterminate Others , gives many more examples). Another example is provided by the seemingly interminable debate about the moral permissibility of abortion, which almost always turns on the question of whether the embryo is a human being.

At this point, it looks like the concept of the human is hopelessly confused. But looked at in the right way, it’s possible to discern a deeper order in the seeming chaos. The picture only seems chaotic if one assumes that “human” is supposed to designate a certain taxonomic category across the board (‘in every possible world’ as philosophers like to say). But if we think of it as an indexical expression – a term that gets its content from the context in which it is uttered – a very different picture emerges.

Paradigmatic indexical terms include words like “now,” “here,” and “I.” Most words name exactly the same thing, irrespective of when, where, and by whom they are uttered. For instance, when anyone anywhere correctly uses the expression ‘the Eiffel Tower,’ they are naming one and the same architectural structure. In contrast, the word “now” names the moment at which the word is uttered, the word “here” names the place where it is uttered, and the word “I” names the person uttering it. If I am right, the word “human” works in much the same way that these words do. When we describe others as human, we are saying that they are members of our own kind or, more precisely, members of our own natural kind.

What’s a natural kind? The best way to wrap one’s mind around the notion of natural kinds is to contrast them with artificial kinds. Airplane pilots are an artificial kind, as are Red Sox fans and residents of New Jersey, because they only exist in virtue of human linguistic and social practices, whereas natural kinds (for example, chemical elements and compounds, microphysical particles, and, more controversially, biological species) exist ‘out there’ in the world. Our concepts of natural are concepts that purport to correspond to the structural fault-lines of a mind-independent world. In Plato’s vivid metaphor, they ‘cut nature at its joints.’ Weeds are an artificial kind, because they exist only in virtue of certain linguistic conventions and social practices, but pteridophyta (ferns) are a natural kind because, unlike weeds, their existence is insensitive to our linguistic conventions.

Philosophers distinguish the linguistic meaning of indexical expressions from their content. The content of an indexical is whatever it names. For example, if you were to say ‘I am here’, the word ‘here’ names the spot where you are sitting. Its linguistic meaning is ‘the place where I am when I utter the word “here”.’ If ‘human’ means ‘my own natural kind,’ then referring to a being as human boils down to the assertion that the other is a member of the natural kind that the speaker believes herself to be. This goes a long way towards explaining why a statement of the form ‘x is human,’ in the mouth of a biologist might mean ‘x is a member of the species Homo sapiens ’ while the very same statement in the mouth of a Nazi might mean ‘x is a member of the Aryan race.’ That's what it means to be human.

David Livingstone Smith, Ph.D ., is professor of philosophy at the University of New England.

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Online Therapy

- United States

- Brooklyn, NY

- Chicago, IL

- Houston, TX

- Los Angeles, CA

- New York, NY

- Portland, OR

- San Diego, CA

- San Francisco, CA

- Seattle, WA

- Washington, DC

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Self Tests NEW

- Therapy Center

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

At any moment, someone’s aggravating behavior or our own bad luck can set us off on an emotional spiral that threatens to derail our entire day. Here’s how we can face our triggers with less reactivity so that we can get on with our lives.

- Emotional Intelligence

- Gaslighting

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

Shelley’s Frankenstein: What It Means to Be Human Essay

- To find inspiration for your paper and overcome writer’s block

- As a source of information (ensure proper referencing)

- As a template for you assignment

Frankenstein, a ground-breaking novel by Mary Shelley published in 1818, raises important questions about what it means to be human. Mary Shelley was inspired to write the book in response to the questions arising from growing interactions between indigenous groups and European colonialists and explorers. While the native people the Europeans encountered exhibited human characteristics, the Europeans generally viewed them as inferior and less intelligent. Therefore, at that time, there was an unending debate about whether non-European ethnicities belonged to the same species as Europeans. The contestation was largely influenced by the Enlightenment led by the philosopher David Hume, who argued that there were different species of people and non-European species were “naturally inferior to the whites” (Lee 265). As a result, the native people were positioned beneath the line dividing humans from animals. This essentially meant they would only be subjects of slavery and oppression. However, Shelly’s Frankenstein runs counter to this theory and challenges the rigid notion of being a human based on a synthetic creature made of dead bodies. The book reveals what it means to be human through the creature’s actions.

When Frankenstein was released, many people were mesmerized by stories of “wild” native tribes in distant lands. Lee (267) states that during that time, the native people were judged only based on their appearance and way of life. However, going by Shelly’s progressive and broader definition, anyone would qualify to be called a human being in their own right. Shelly’s illustration even included the “savages” that her contemporaries looked down upon. Shelly uses the classic example of a creature that could survive on a vegetarian diet and climb mountains relatively easily. Her depiction of the creature through Victor Frankenstein shows that he is innately tied to the natural world (Shelley 85). However, the horrific responses he receives from others, including his creator, causes him to live in exile away from the European culture and dwell in the woods.

Furthermore, the creature’s looks make it obvious that it is not European. It stands at “nearly eight feet tall,” is far taller than the average European, and has “yellow skin” and “straight black lips” (Shelley 59). Even though a European developed him, his physical distinctiveness “the work of muscles and arteries beneath” set him apart from others (Shelley 59). Because he has been cast out of society due to his appearance, the creature is not a party to the social contract of the Enlightenment, a tacit agreement between all members of a country to protect each other’s basic rights. When the creature meets others, they fail in their duty to protect his human rights as a group, and later in the book, he murders in retaliation. The pervasive Enlightenment conception of the social contract generates an abstract divide between “civilized man” and “natural man” (Lee 275). The contract allows man to transition out of his “state of nature” and into modern society. That is why most Europeans, the moment Frankenstein was published, would not have understood how deeply connected to nature the creature or many indigenous peoples were.

Notwithstanding the deep connection to nature, the creature is human and characterized by an emotional and often compassionate personality. Despite his young age, he is almost as emotional and just as eloquent as his creator. When Felix, a young farmer whose home he stays in for a while, attacks him, he refrains from retaliation and saves a young girl only from being shot by her male companion. He frequently exhibits more moral “human” behavior than those he meets (Shelley 130). In both instances, he exhibits kindness and mercy and is unjustly assaulted by humans who misjudge him. At one time, the creature gets confronted, causing an aggressive, malicious, and vengeful reaction. However, the creature exemplifies intense guilt at the novel’s conclusion, which characterizes humanity. The creature’s depiction as physically non-European, self-educated, and yet unquestionably human can be applied to the indigenous people in nations like South America that European explorers frequently encountered. The indigenous people were characterized by their lifestyle and appearance rather than their inherent intelligence or upbringing. They can only exist in the natural world because they are not mostly allowed to live in European culture.

In conclusion, Shelley used her book, Frankenstein, to show what it means to be human through the creature’s actions. She broadens the definition of humanity by creating a progressive vision that enables those deemed less human to be regarded as completely human. The creature’s actions, when confronted, act as a caution against the risks of treating other people with indignity. Shelley’s story urges the reader to allow everyone to prove themselves before judging them based on their appearance. She advocates for fair treatment by drawing comparisons between the creature and its existence in nature and indigenous peoples worldwide, both forms of the “other.” As shown by the creature’s actions, anyone could end up becoming what is unfairly expected of them if they are not given an equal chance because of the psychological harm caused by the way they have been treated. In the end, the discovery that both the indigenous and the creature are human but are not perceived as such in civilization exposes the flaws in the prejudiced yet obscured view of humanity held by the Enlightenment.

Works Cited

Lee, Seogkwang. “ Humanity in Monstrous Form: Reading Mary Shelley Frankenstein .” The Journal of East-West Comparative Literature , vol. 49, 2019, pp. 261–85, Web.

Shelley, Mary. Frankenstein, or, the Modern Prometheus . Legend Press, 2018.

- “Frankenstein” by Mary Shelley

- Ethics of Discovery in Mary Shelley's "Frankenstein"

- Frankenstein's Historical Context: Review of "In Frankenstein’s Shadow" by Chris Baldrick

- King Lear as a Depiction of Shakespeare's Era

- Themes in "Dancing in the Dark" Novel by Phillip

- The "Dancing in the Dark" Novel by Caryl Phillip

- "Frankenstein" by Mary Shelley Review

- Lewis' The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe Book

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2023, December 17). Shelley's Frankenstein: What It Means to Be Human. https://ivypanda.com/essays/shelleys-frankenstein-what-it-means-to-be-human/

"Shelley's Frankenstein: What It Means to Be Human." IvyPanda , 17 Dec. 2023, ivypanda.com/essays/shelleys-frankenstein-what-it-means-to-be-human/.

IvyPanda . (2023) 'Shelley's Frankenstein: What It Means to Be Human'. 17 December.

IvyPanda . 2023. "Shelley's Frankenstein: What It Means to Be Human." December 17, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/shelleys-frankenstein-what-it-means-to-be-human/.

1. IvyPanda . "Shelley's Frankenstein: What It Means to Be Human." December 17, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/shelleys-frankenstein-what-it-means-to-be-human/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Shelley's Frankenstein: What It Means to Be Human." December 17, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/shelleys-frankenstein-what-it-means-to-be-human/.

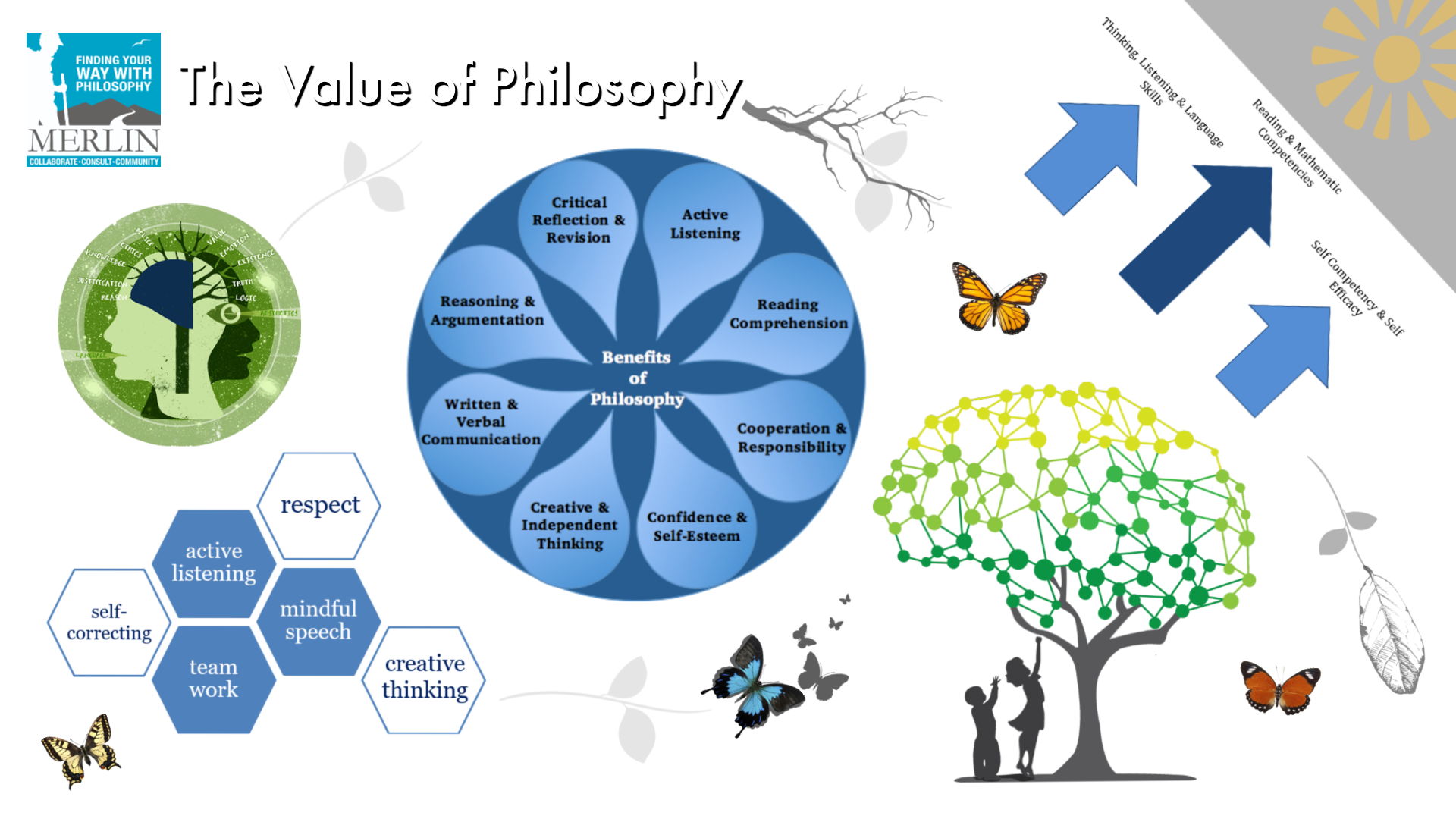

What Philosophy & Anthropology Can Tell Us About Being Human

In this article, Dr. Brian Morris — Emeritus Professor of Anthropology at Goldsmiths, University of London — focuses on how philosophers (Immanuel Kant, in particular, and various schools of thought like existentialism, post-modernism, Marxism, Pragmatism, etc.) and anthropologists have approached the question “what is the human being?”

While, indubitably, this article looks at this question largely through an anthropological lens, both perspectives are valuable and can inform one another. In fact, Kant — perhaps most well-known for his work in moral philosophy — was (along with Rousseau, Herder, Ferguson, and others) a founding ancestor of anthropology, describing it as the study or science of humankind. His fundamental question, “what is the human being?” inevitably intertwined the sorts of questions and lines of inquiry common in both fields.

What is Anthropology?

Morris defines anthropology as a discipline with a ‘dual heritage’ that combines humanism and naturalism and whose insights were drawn from both the Enlightenment and Romanticism periods. “In many ways,” he says, “it is an inter-discipline, held together by placing an emphasis on ethnographic studies, which involve a close experiential encounter with a particular way of life or culture .”

In terms of method, [anthropology] combines scientific explanations of social and cultural phenomena with hermeneutics or biosemiotics. Yet although certain people write of some great divide or schism within anthropology, it has always had, in spite of its diversity, a certain unity of vision and purpose. It employs a universal perspective that places humans firmly within nature. Anthropology has therefore always placed itself at the interface between the humanities and the natural sciences, especially evolutionary biology. – Dr. Brian Morris

According to Morris, anthropology offers an extremely valuable perspective on Kant’s fundamental question about humankind , in large part because it “can offer a cultural critique of much of Western culture and philosophy, while at the same time emphasizing our shared humanity (Kant), thus enlarging our sense of moral community .”

What Does it Mean to Be Human?

Conceptions about what it means to be human vary dramatically across cultures and even within cultures . Within the Western intellectual tradition, for example, the human being is defined and conceptualized in countless and often contrasting ways. The essentialist response, the dualist response, and the triadic ontology response (offered by Kant) are just three examples. Broadly speaking:

- Essentialism tends to define the human subject or self in terms of a single essential attribute.

- Dualism defines the human subject or self as being split in some fashion. For example, mind and body (according to Descartes) are in some way categorically separate from each other.

- Kant’s Triadic Ontology defines the human subject or self in (as the name suggests) three ways — as a universal human being (mensch), as a unique self (selbst), and as a social being, a member of a particular group of people

While Ockham’s Razor would suggest that we take the simplest approach possible….and not muddy the waters unnecessarily…the human being does indeed seem to be a very muddy creature. ( Note: Ockham’s Razor is still applicable here…it just means that “the simplest approach possible” is complex…and muddy).

To quote Morris: “Throughout the twentieth century, many scholars, within diverse intellectual traditions…developed a more integrated approach to the understanding of the human subject, recognizing, like Kant, the need to develop a more complex model of the subject.”

To read this article in its entirety, click here !

Comments are closed.

A Non-Profit Organization

- Search for: Search

Merlin Events Calendar

Make a Donation

By investing in philosophy, you are investing in community. Please don your toga by making a tax-deductible donation today and/or by becoming a sustaining donor! Click on the yellow donate button to donate via PayPal, the blue donate button to donate via Moonclerk, or donate via QR code.

Special Project

Learn more about our 2024-2025 special public philosophy project on homelessness.

Stay in the Loop

Things to Consider

Testimonials.

Community Hubs

Want to help bring a new program to the Helena & Mountain West communities? Our Community Hubs project is an innovative vision for public humanities that re-centers community as a place of learning. Learn more about our vision & how you can help support it here!

We Love Our Donors!

The Value of Philosophy

Proud Members

- Table of Contents

- Random Entry

- Chronological

- Editorial Information

- About the SEP

- Editorial Board

- How to Cite the SEP

- Special Characters

- Advanced Tools

- Support the SEP

- PDFs for SEP Friends

- Make a Donation

- SEPIA for Libraries

- Entry Contents

Bibliography

Academic tools.

- Friends PDF Preview

- Author and Citation Info

- Back to Top

The Meaning of Life

Many major historical figures in philosophy have provided an answer to the question of what, if anything, makes life meaningful, although they typically have not put it in these terms (with such talk having arisen only in the past 250 years or so, on which see Landau 1997). Consider, for instance, Aristotle on the human function, Aquinas on the beatific vision, and Kant on the highest good. Relatedly, think about Koheleth, the presumed author of the Biblical book Ecclesiastes, describing life as “futility” and akin to “the pursuit of wind,” Nietzsche on nihilism, as well as Schopenhauer when he remarks that whenever we reach a goal we have longed for we discover “how vain and empty it is.” While these concepts have some bearing on happiness and virtue (and their opposites), they are straightforwardly construed (roughly) as accounts of which highly ranked purposes a person ought to realize that would make her life significant (if any would).

Despite the venerable pedigree, it is only since the 1980s or so that a distinct field of the meaning of life has been established in Anglo-American-Australasian philosophy, on which this survey focuses, and it is only in the past 20 years that debate with real depth and intricacy has appeared. Two decades ago analytic reflection on life’s meaning was described as a “backwater” compared to that on well-being or good character, and it was possible to cite nearly all the literature in a given critical discussion of the field (Metz 2002). Neither is true any longer. Anglo-American-Australasian philosophy of life’s meaning has become vibrant, such that there is now way too much literature to be able to cite comprehensively in this survey. To obtain focus, it tends to discuss books, influential essays, and more recent works, and it leaves aside contributions from other philosophical traditions (such as the Continental or African) and from non-philosophical fields (e.g., psychology or literature). This survey’s central aim is to acquaint the reader with current analytic approaches to life’s meaning, sketching major debates and pointing out neglected topics that merit further consideration.

When the topic of the meaning of life comes up, people tend to pose one of three questions: “What are you talking about?”, “What is the meaning of life?”, and “Is life in fact meaningful?”. The literature on life's meaning composed by those working in the analytic tradition (on which this entry focuses) can be usefully organized according to which question it seeks to answer. This survey starts off with recent work that addresses the first, abstract (or “meta”) question regarding the sense of talk of “life’s meaning,” i.e., that aims to clarify what we have in mind when inquiring into the meaning of life (section 1). Afterward, it considers texts that provide answers to the more substantive question about the nature of meaningfulness (sections 2–3). There is in the making a sub-field of applied meaning that parallels applied ethics, in which meaningfulness is considered in the context of particular cases or specific themes. Examples include downshifting (Levy 2005), implementing genetic enhancements (Agar 2013), making achievements (Bradford 2015), getting an education (Schinkel et al. 2015), interacting with research participants (Olson 2016), automating labor (Danaher 2017), and creating children (Ferracioli 2018). In contrast, this survey focuses nearly exclusively on contemporary normative-theoretical approaches to life’s meanining, that is, attempts to capture in a single, general principle all the variegated conditions that could confer meaning on life. Finally, this survey examines fresh arguments for the nihilist view that the conditions necessary for a meaningful life do not obtain for any of us, i.e., that all our lives are meaningless (section 4).

1. The Meaning of “Meaning”

2.1. god-centered views, 2.2. soul-centered views, 3.1. subjectivism, 3.2. objectivism, 3.3. rejecting god and a soul, 4. nihilism, works cited, classic works, collections, books for the general reader, other internet resources, related entries.

One of the field's aims consists of the systematic attempt to identify what people (essentially or characteristically) have in mind when they think about the topic of life’s meaning. For many in the field, terms such as “importance” and “significance” are synonyms of “meaningfulness” and so are insufficiently revealing, but there are those who draw a distinction between meaningfulness and significance (Singer 1996, 112–18; Belliotti 2019, 145–50, 186). There is also debate about how the concept of a meaningless life relates to the ideas of a life that is absurd (Nagel 1970, 1986, 214–23; Feinberg 1980; Belliotti 2019), futile (Trisel 2002), and not worth living (Landau 2017, 12–15; Matheson 2017).

A useful way to begin to get clear about what thinking about life’s meaning involves is to specify the bearer. Which life does the inquirer have in mind? A standard distinction to draw is between the meaning “in” life, where a human person is what can exhibit meaning, and the meaning “of” life in a narrow sense, where the human species as a whole is what can be meaningful or not. There has also been a bit of recent consideration of whether animals or human infants can have meaning in their lives, with most rejecting that possibility (e.g., Wong 2008, 131, 147; Fischer 2019, 1–24), but a handful of others beginning to make a case for it (Purves and Delon 2018; Thomas 2018). Also under-explored is the issue of whether groups, such as a people or an organization, can be bearers of meaning, and, if so, under what conditions.

Most analytic philosophers have been interested in meaning in life, that is, in the meaningfulness that a person’s life could exhibit, with comparatively few these days addressing the meaning of life in the narrow sense. Even those who believe that God is or would be central to life’s meaning have lately addressed how an individual’s life might be meaningful in virtue of God more often than how the human race might be. Although some have argued that the meaningfulness of human life as such merits inquiry to no less a degree (if not more) than the meaning in a life (Seachris 2013; Tartaglia 2015; cf. Trisel 2016), a large majority of the field has instead been interested in whether their lives as individual persons (and the lives of those they care about) are meaningful and how they could become more so.

Focusing on meaning in life, it is quite common to maintain that it is conceptually something good for its own sake or, relatedly, something that provides a basic reason for action (on which see Visak 2017). There are a few who have recently suggested otherwise, maintaining that there can be neutral or even undesirable kinds of meaning in a person’s life (e.g., Mawson 2016, 90, 193; Thomas 2018, 291, 294). However, these are outliers, with most analytic philosophers, and presumably laypeople, instead wanting to know when an individual’s life exhibits a certain kind of final value (or non-instrumental reason for action).

Another claim about which there is substantial consensus is that meaningfulness is not all or nothing and instead comes in degrees, such that some periods of life are more meaningful than others and that some lives as a whole are more meaningful than others. Note that one can coherently hold the view that some people’s lives are less meaningful (or even in a certain sense less “important”) than others, or are even meaningless (unimportant), and still maintain that people have an equal standing from a moral point of view. Consider a consequentialist moral principle according to which each individual counts for one in virtue of having a capacity for a meaningful life, or a Kantian approach according to which all people have a dignity in virtue of their capacity for autonomous decision-making, where meaning is a function of the exercise of this capacity. For both moral outlooks, we could be required to help people with relatively meaningless lives.

Yet another relatively uncontroversial element of the concept of meaningfulness in respect of individual persons is that it is logically distinct from happiness or rightness (emphasized in Wolf 2010, 2016). First, to ask whether someone’s life is meaningful is not one and the same as asking whether her life is pleasant or she is subjectively well off. A life in an experience machine or virtual reality device would surely be a happy one, but very few take it to be a prima facie candidate for meaningfulness (Nozick 1974: 42–45). Indeed, a number would say that one’s life logically could become meaningful precisely by sacrificing one’s well-being, e.g., by helping others at the expense of one’s self-interest. Second, asking whether a person’s existence over time is meaningful is not identical to considering whether she has been morally upright; there are intuitively ways to enhance meaning that have nothing to do with right action or moral virtue, such as making a scientific discovery or becoming an excellent dancer. Now, one might argue that a life would be meaningless if, or even because, it were unhappy or immoral, but that would be to posit a synthetic, substantive relationship between the concepts, far from indicating that speaking of “meaningfulness” is analytically a matter of connoting ideas regarding happiness or rightness. The question of what (if anything) makes a person’s life meaningful is conceptually distinct from the questions of what makes a life happy or moral, although it could turn out that the best answer to the former question appeals to an answer to one of the latter questions.

Supposing, then, that talk of “meaning in life” connotes something good for its own sake that can come in degrees and that is not analytically equivalent to happiness or rightness, what else does it involve? What more can we say about this final value, by definition? Most contemporary analytic philosophers would say that the relevant value is absent from spending time in an experience machine (but see Goetz 2012 for a different view) or living akin to Sisyphus, the mythic figure doomed by the Greek gods to roll a stone up a hill for eternity (famously discussed by Albert Camus and Taylor 1970). In addition, many would say that the relevant value is typified by the classic triad of “the good, the true, and the beautiful” (or would be under certain conditions). These terms are not to be taken literally, but instead are rough catchwords for beneficent relationships (love, collegiality, morality), intellectual reflection (wisdom, education, discoveries), and creativity (particularly the arts, but also potentially things like humor or gardening).

Pressing further, is there something that the values of the good, the true, the beautiful, and any other logically possible sources of meaning involve? There is as yet no consensus in the field. One salient view is that the concept of meaning in life is a cluster or amalgam of overlapping ideas, such as fulfilling higher-order purposes, meriting substantial esteem or admiration, having a noteworthy impact, transcending one’s animal nature, making sense, or exhibiting a compelling life-story (Markus 2003; Thomson 2003; Metz 2013, 24–35; Seachris 2013, 3–4; Mawson 2016). However, there are philosophers who maintain that something much more monistic is true of the concept, so that (nearly) all thought about meaningfulness in a person’s life is essentially about a single property. Suggestions include being devoted to or in awe of qualitatively superior goods (Taylor 1989, 3–24), transcending one’s limits (Levy 2005), or making a contribution (Martela 2016).

Recently there has been something of an “interpretive turn” in the field, one instance of which is the strong view that meaning-talk is logically about whether and how a life is intelligible within a wider frame of reference (Goldman 2018, 116–29; Seachris 2019; Thomas 2019; cf. Repp 2018). According to this approach, inquiring into life’s meaning is nothing other than seeking out sense-making information, perhaps a narrative about life or an explanation of its source and destiny. This analysis has the advantage of promising to unify a wide array of uses of the term “meaning.” However, it has the disadvantages of being unable to capture the intuitions that meaning in life is essentially good for its own sake (Landau 2017, 12–15), that it is not logically contradictory to maintain that an ineffable condition is what confers meaning on life (as per Cooper 2003, 126–42; Bennett-Hunter 2014; Waghorn 2014), and that often human actions themselves (as distinct from an interpretation of them), such as rescuing a child from a burning building, are what bear meaning.

Some thinkers have suggested that a complete analysis of the concept of life’s meaning should include what has been called “anti-matter” (Metz 2002, 805–07, 2013, 63–65, 71–73) or “anti-meaning” (Campbell and Nyholm 2015; Egerstrom 2015), conditions that reduce the meaningfulness of a life. The thought is that meaning is well represented by a bipolar scale, where there is a dimension of not merely positive conditions, but also negative ones. Gratuitous cruelty or destructiveness are prima facie candidates for actions that not merely fail to add meaning, but also subtract from any meaning one’s life might have had.

Despite the ongoing debates about how to analyze the concept of life’s meaning (or articulate the definition of the phrase “meaning in life”), the field remains in a good position to make progress on the other key questions posed above, viz., of what would make a life meaningful and whether any lives are in fact meaningful. A certain amount of common ground is provided by the point that meaningfulness at least involves a gradient final value in a person’s life that is conceptually distinct from happiness and rightness, with exemplars of it potentially being the good, the true, and the beautiful. The rest of this discussion addresses philosophical attempts to capture the nature of this value theoretically and to ascertain whether it exists in at least some of our lives.

2. Supernaturalism

Most analytic philosophers writing on meaning in life have been trying to develop and evaluate theories, i.e., fundamental and general principles, that are meant to capture all the particular ways that a life could obtain meaning. As in moral philosophy, there are recognizable “anti-theorists,” i.e., those who maintain that there is too much pluralism among meaning conditions to be able to unify them in the form of a principle (e.g., Kekes 2000; Hosseini 2015). Arguably, though, the systematic search for unity is too nascent to be able to draw a firm conclusion about whether it is available.

The theories are standardly divided on a metaphysical basis, that is, in terms of which kinds of properties are held to constitute the meaning. Supernaturalist theories are views according to which a spiritual realm is central to meaning in life. Most Western philosophers have conceived of the spiritual in terms of God or a soul as commonly understood in the Abrahamic faiths (but see Mulgan 2015 for discussion of meaning in the context of a God uninterested in us). In contrast, naturalist theories are views that the physical world as known particularly well by the scientific method is central to life’s meaning.

There is logical space for a non-naturalist theory, according to which central to meaning is an abstract property that is neither spiritual nor physical. However, only scant attention has been paid to this possibility in the recent Anglo-American-Australasian literature (Audi 2005).

It is important to note that supernaturalism, a claim that God (or a soul) would confer meaning on a life, is logically distinct from theism, the claim that God (or a soul) exists. Although most who hold supernaturalism also hold theism, one could accept the former without the latter (as Camus more or less did), committing one to the view that life is meaningless or at least lacks substantial meaning. Similarly, while most naturalists are atheists, it is not contradictory to maintain that God exists but has nothing to do with meaning in life or perhaps even detracts from it. Although these combinations of positions are logically possible, some of them might be substantively implausible. The field could benefit from discussion of the comparative attractiveness of various combinations of evaluative claims about what would make life meaningful and metaphysical claims about whether spiritual conditions exist.

Over the past 15 years or so, two different types of supernaturalism have become distinguished on a regular basis (Metz 2019). That is true not only in the literature on life’s meaning, but also in that on the related pro-theism/anti-theism debate, about whether it would be desirable for God or a soul to exist (e.g., Kahane 2011; Kraay 2018; Lougheed 2020). On the one hand, there is extreme supernaturalism, according to which spiritual conditions are necessary for any meaning in life. If neither God nor a soul exists, then, by this view, everyone’s life is meaningless. On the other hand, there is moderate supernaturalism, according to which spiritual conditions are necessary for a great or ultimate meaning in life, although not meaning in life as such. If neither God nor a soul exists, then, by this view, everyone’s life could have some meaning, or even be meaningful, but no one’s life could exhibit the most desirable meaning. For a moderate supernaturalist, God or a soul would substantially enhance meaningfulness or be a major contributory condition for it.

There are a variety of ways that great or ultimate meaning has been described, sometimes quantitatively as “infinite” (Mawson 2016), qualitatively as “deeper” (Swinburne 2016), relationally as “unlimited” (Nozick 1981, 618–19; cf. Waghorn 2014), temporally as “eternal” (Cottingham 2016), and perspectivally as “from the point of view of the universe” (Benatar 2017). There has been no reflection as yet on the crucial question of how these distinctions might bear on each another, for instance, on whether some are more basic than others or some are more valuable than others.

Cross-cutting the extreme/moderate distinction is one between God-centered theories and soul-centered ones. According to the former, some kind of connection with God (understood to be a spiritual person who is all-knowing, all-good, and all-powerful and who is the ground of the physical universe) constitutes meaning in life, even if one lacks a soul (construed as an immortal, spiritual substance that contains one’s identity). In contrast, by the latter, having a soul and putting it into a certain state is what makes life meaningful, even if God does not exist. Many supernaturalists of course believe that God and a soul are jointly necessary for a (greatly) meaningful existence. However, the simpler view, that only one of them is necessary, is common, and sometimes arguments proffered for the complex view fail to support it any more than the simpler one.

The most influential God-based account of meaning in life has been the extreme view that one’s existence is significant if and only if one fulfills a purpose God has assigned. The familiar idea is that God has a plan for the universe and that one’s life is meaningful just to the degree that one helps God realize this plan, perhaps in a particular way that God wants one to do so. If a person failed to do what God intends her to do with her life (or if God does not even exist), then, on the current view, her life would be meaningless.

Thinkers differ over what it is about God’s purpose that might make it uniquely able to confer meaning on human lives, but the most influential argument has been that only God’s purpose could be the source of invariant moral rules (Davis 1987, 296, 304–05; Moreland 1987, 124–29; Craig 1994/2013, 161–67) or of objective values more generally (Cottingham 2005, 37–57), where a lack of such would render our lives nonsensical. According to this argument, lower goods such as animal pleasure or desire satisfaction could exist without God, but higher ones pertaining to meaning in life, particularly moral virtue, could not. However, critics point to many non-moral sources of meaning in life (e.g., Kekes 2000; Wolf 2010), with one arguing that a universal moral code is not necessary for meaning in life, even if, say, beneficent actions are (Ellin 1995, 327). In addition, there are a variety of naturalist and non-naturalist accounts of objective morality––and of value more generally––on offer these days, so that it is not clear that it must have a supernatural source in God’s will.

One recurrent objection to the idea that God’s purpose could make life meaningful is that if God had created us with a purpose in mind, then God would have degraded us and thereby undercut the possibility of us obtaining meaning from fulfilling the purpose. The objection harks back to Jean-Paul Sartre, but in the analytic literature it appears that Kurt Baier was the first to articulate it (1957/2000, 118–20; see also Murphy 1982, 14–15; Singer 1996, 29; Kahane 2011; Lougheed 2020, 121–41). Sometimes the concern is the threat of punishment God would make so that we do God’s bidding, while other times it is that the source of meaning would be constrictive and not up to us, and still other times it is that our dignity would be maligned simply by having been created with a certain end in mind (for some replies to such concerns, see Hanfling 1987, 45–46; Cottingham 2005, 37–57; Lougheed 2020, 111–21).

There is a different argument for an extreme God-based view that focuses less on God as purposive and more on God as infinite, unlimited, or ineffable, which Robert Nozick first articulated with care (Nozick 1981, 594–618; see also Bennett-Hunter 2014; Waghorn 2014). The core idea is that for a finite condition to be meaningful, it must obtain its meaning from another condition that has meaning. So, if one’s life is meaningful, it might be so in virtue of being married to a person, who is important. Being finite, the spouse must obtain his or her importance from elsewhere, perhaps from the sort of work he or she does. This work also must obtain its meaning by being related to something else that is meaningful, and so on. A regress on meaningful conditions is present, and the suggestion is that the regress can terminate only in something so all-encompassing that it need not (indeed, cannot) go beyond itself to obtain meaning from anything else. And that is God. The standard objection to this relational rationale is that a finite condition could be meaningful without obtaining its meaning from another meaningful condition. Perhaps it could be meaningful in itself, without being connected to something beyond it, or maybe it could obtain its meaning by being related to something else that is beautiful or otherwise valuable for its own sake but not meaningful (Nozick 1989, 167–68; Thomson 2003, 25–26, 48).

A serious concern for any extreme God-based view is the existence of apparent counterexamples. If we think of the stereotypical lives of Albert Einstein, Mother Teresa, and Pablo Picasso, they seem meaningful even if we suppose there is no all-knowing, all-powerful, and all-good spiritual person who is the ground of the physical world (e.g., Wielenberg 2005, 31–37, 49–50; Landau 2017). Even religiously inclined philosophers have found this hard to deny these days (Quinn 2000, 58; Audi 2005; Mawson 2016, 5; Williams 2020, 132–34).

Largely for that reason, contemporary supernaturalists have tended to opt for moderation, that is, to maintain that God would greatly enhance the meaning in our lives, even if some meaning would be possible in a world without God. One approach is to invoke the relational argument to show that God is necessary, not for any meaning whatsoever, but rather for an ultimate meaning. “Limited transcendence, the transcending of our limits so as to connect with a wider context of value which itself is limited, does give our lives meaning––but a limited one. We may thirst for more” (Nozick 1981, 618). Another angle is to appeal to playing a role in God’s plan, again to claim, not that it is essential for meaning as such, but rather for “a cosmic significance....intead of a significance very limited in time and space” (Swinburne 2016, 154; see also Quinn 2000; Cottingham 2016, 131). Another rationale is that by fulfilling God’s purpose, we would meaningfully please God, a perfect person, as well as be remembered favorably by God forever (Cottingham 2016, 135; Williams 2020, 21–22, 29, 101, 108). Still another argument is that only with God could the deepest desires of human nature be satisfied (e.g., Goetz 2012; Seachris 2013, 20; Cottingham 2016, 127, 136), even if more surface desires could be satisfied without God.

In reply to such rationales for a moderate supernaturalism, there has been the suggestion that it is precisely by virtue of being alone in the universe that our lives would be particularly significant; otherwise, God’s greatness would overshadow us (Kahane 2014). There has also been the response that, with the opportunity for greater meaning from God would also come that for greater anti-meaning, so that it is not clear that a world with God would offer a net gain in respect of meaning (Metz 2019, 34–35). For example, if pleasing God would greatly enhance meaning in our lives, then presumably displeasing God would greatly reduce it and to a comparable degree. In addition, there are arguments for extreme naturalism (or its “anti-theist” cousin) mentioned below (sub-section 3.3).

Notice that none of the above arguments for supernaturalism appeals to the prospect of eternal life (at least not explicitly). Arguments that do make such an appeal are soul-centered, holding that meaning in life mainly comes from having an immortal, spiritual substance that is contiguous with one’s body when it is alive and that will forever outlive its death. Some think of the afterlife in terms of one’s soul entering a transcendent, spiritual realm (Heaven), while others conceive of one’s soul getting reincarnated into another body on Earth. According to the extreme version, if one has a soul but fails to put it in the right state (or if one lacks a soul altogether), then one’s life is meaningless.

There are three prominent arguments for an extreme soul-based perspective. One argument, made famous by Leo Tolstoy, is the suggestion that for life to be meaningful something must be worth doing, that something is worth doing only if it will make a permanent difference to the world, and that making a permanent difference requires being immortal (see also Hanfling 1987, 22–24; Morris 1992, 26; Craig 1994). Critics most often appeal to counterexamples, suggesting for instance that it is surely worth your time and effort to help prevent people from suffering, even if you and they are mortal. Indeed, some have gone on the offensive and argued that helping people is worth the sacrifice only if and because they are mortal, for otherwise they could invariably be compensated in an afterlife (e.g., Wielenberg 2005, 91–94). Another recent and interesting criticism is that the major motivations for the claim that nothing matters now if one day it will end are incoherent (Greene 2021).

A second argument for the view that life would be meaningless without a soul is that it is necessary for justice to be done, which, in turn, is necessary for a meaningful life. Life seems nonsensical when the wicked flourish and the righteous suffer, at least supposing there is no other world in which these injustices will be rectified, whether by God or a Karmic force. Something like this argument can be found in Ecclesiastes, and it continues to be defended (e.g., Davis 1987; Craig 1994). However, even granting that an afterlife is required for perfectly just outcomes, it is far from obvious that an eternal afterlife is necessary for them, and, then, there is the suggestion that some lives, such as Mandela’s, have been meaningful precisely in virtue of encountering injustice and fighting it.

A third argument for thinking that having a soul is essential for any meaning is that it is required to have the sort of free will without which our lives would be meaningless. Immanuel Kant is known for having maintained that if we were merely physical beings, subjected to the laws of nature like everything else in the material world, then we could not act for moral reasons and hence would be unimportant. More recently, one theologian has eloquently put the point in religious terms: “The moral spirit finds the meaning of life in choice. It finds it in that which proceeds from man and remains with him as his inner essence rather than in the accidents of circumstances turns of external fortune....(W)henever a human being rubs the lamp of his moral conscience, a Spirit does appear. This Spirit is God....It is in the ‘Thou must’ of God and man’s ‘I can’ that the divine image of God in human life is contained” (Swenson 1949/2000, 27–28). Notice that, even if moral norms did not spring from God’s commands, the logic of the argument entails that one’s life could be meaningful, so long as one had the inherent ability to make the morally correct choice in any situation. That, in turn, arguably requires something non-physical about one’s self, so as to be able to overcome whichever physical laws and forces one might confront. The standard objection to this reasoning is to advance a compatibilism about having a determined physical nature and being able to act for moral reasons (e.g., Arpaly 2006; Fischer 2009, 145–77). It is also worth wondering whether, if one had to have a spiritual essence in order to make free choices, it would have to be one that never perished.

Like God-centered theorists, many soul-centered theorists these days advance a moderate view, accepting that some meaning in life would be possible without immortality, but arguing that a much greater meaning would be possible with it. Granting that Einstein, Mandela, and Picasso had somewhat meaningful lives despite not having survived the deaths of their bodies (as per, e.g., Trisel 2004; Wolf 2015, 89–140; Landau 2017), there remains a powerful thought: more is better. If a finite life with the good, the true, and the beautiful has meaning in it to some degree, then surely it would have all the more meaning if it exhibited such higher values––including a relationship with God––for an eternity (Cottingham 2016, 132–35; Mawson 2016, 2019, 52–53; Williams 2020, 112–34; cf. Benatar 2017, 35–63). One objection to this reasoning is that the infinity of meaning that would be possible with a soul would be “too big,” rendering it difficult for the moderate supernaturalist to make sense of the intution that a finite life such as Einstein’s can indeed count as meaningful by comparison (Metz 2019, 30–31; cf. Mawson 2019, 53–54). More common, though, is the objection that an eternal life would include anti-meaning of various kinds, such as boredom and repetition, discussed below in the context of extreme naturalism (sub-section 3.3).

3. Naturalism

Recall that naturalism is the view that a physical life is central to life’s meaning, that even if there is no spiritual realm, a substantially meaningful life is possible. Like supernaturalism, contemporary naturalism admits of two distinguishable variants, moderate and extreme (Metz 2019). The moderate version is that, while a genuinely meaningful life could be had in a purely physical universe as known well by science, a somewhat more meaningful life would be possible if a spiritual realm also existed. God or a soul could enhance meaning in life, although they would not be major contributors. The extreme version of naturalism is the view that it would be better in respect of life’s meaning if there were no spiritual realm. From this perspective, God or a soul would be anti-matter, i.e., would detract from the meaning available to us, making a purely physical world (even if not this particular one) preferable.

Cross-cutting the moderate/extreme distinction is that between subjectivism and objectivism, which are theoretical accounts of the nature of meaningfulness insofar as it is physical. They differ in terms of the extent to which the human mind constitutes meaning and whether there are conditions of meaning that are invariant among human beings. Subjectivists believe that there are no invariant standards of meaning because meaning is relative to the subject, i.e., depends on an individual’s pro-attitudes such as her particular desires or ends, which are not shared by everyone. Roughly, something is meaningful for a person if she strongly wants it or intends to seek it out and she gets it. Objectivists maintain, in contrast, that there are some invariant standards for meaning because meaning is at least partly mind-independent, i.e., obtains not merely in virtue of being the object of anyone’s mental states. Here, something is meaningful (partially) because of its intrinsic nature, in the sense of being independent of whether it is wanted or intended; meaning is instead (to some extent) the sort of thing that merits these reactions.

There is logical space for an orthogonal view, according to which there are invariant standards of meaningfulness constituted by what all human beings would converge on from a certain standpoint. However, it has not been much of a player in the field (Darwall 1983, 164–66).

According to this version of naturalism, meaning in life varies from person to person, depending on each one’s variable pro-attitudes. Common instances are views that one’s life is more meaningful, the more one gets what one happens to want strongly, achieves one’s highly ranked goals, or does what one believes to be really important (Trisel 2002; Hooker 2008). One influential subjectivist has recently maintained that the relevant mental state is caring or loving, so that life is meaningful just to the extent that one cares about or loves something (Frankfurt 1988, 80–94, 2004). Another recent proposal is that meaningfulness consists of “an active engagement and affirmation that vivifies the person who has freely created or accepted and now promotes and nurtures the projects of her highest concern” (Belliotti 2019, 183).

Subjectivism was dominant in the middle of the twentieth century, when positivism, noncognitivism, existentialism, and Humeanism were influential (Ayer 1947; Hare 1957; Barnes 1967; Taylor 1970; Williams 1976). However, in the last quarter of the twentieth century, inference to the best explanation and reflective equilibrium became accepted forms of normative argumentation and were frequently used to defend claims about the existence and nature of objective value (or of “external reasons,” ones obtaining independently of one’s extant attitudes). As a result, subjectivism about meaning lost its dominance. Those who continue to hold subjectivism often remain suspicious of attempts to justify beliefs about objective value (e.g., Trisel 2002, 73, 79, 2004, 378–79; Frankfurt 2004, 47–48, 55–57; Wong 2008, 138–39; Evers 2017, 32, 36; Svensson 2017, 54). Theorists are moved to accept subjectivism typically because the alternatives are unpalatable; they are reasonably sure that meaning in life obtains for some people, but do not see how it could be grounded on something independent of the mind, whether it be the natural or the supernatural (or the non-natural). In contrast to these possibilities, it appears straightforward to account for what is meaningful in terms of what people find meaningful or what people want out of their lives. Wide-ranging meta-ethical debates in epistemology, metaphysics, and the philosophy of language are necessary to address this rationale for subjectivism.

There is a cluster of other, more circumscribed arguments for subjectivism, according to which this theory best explains certain intuitive features of meaning in life. For one, subjectivism seems plausible since it is reasonable to think that a meaningful life is an authentic one (Frankfurt 1988, 80–94). If a person’s life is significant insofar as she is true to herself or her deepest nature, then we have some reason to believe that meaning simply is a function of those matters for which the person cares. For another, it is uncontroversial that often meaning comes from losing oneself, i.e., in becoming absorbed in an activity or experience, as opposed to being bored by it or finding it frustrating (Frankfurt 1988, 80–94; Belliotti 2019, 162–70). Work that concentrates the mind and relationships that are engrossing seem central to meaning and to be so because of the subjective elements involved. For a third, meaning is often taken to be something that makes life worth continuing for a specific person, i.e., that gives her a reason to get out of bed in the morning, which subjectivism is thought to account for best (Williams 1976; Svensson 2017; Calhoun 2018).

Critics maintain that these arguments are vulnerable to a common objection: they neglect the role of objective value (or an external reason) in realizing oneself, losing oneself, and having a reason to live (Taylor 1989, 1992; Wolf 2010, 2015, 89–140). One is not really being true to oneself, losing oneself in a meaningful way, or having a genuine reason to live insofar as one, say, successfully maintains 3,732 hairs on one’s head (Taylor 1992, 36), cultivates one’s prowess at long-distance spitting (Wolf 2010, 104), collects a big ball of string (Wolf 2010, 104), or, well, eats one’s own excrement (Wielenberg 2005, 22). The counterexamples suggest that subjective conditions are insufficient to ground meaning in life; there seem to be certain actions, relationships, and states that are objectively valuable (but see Evers 2017, 30–32) and toward which one’s pro-attitudes ought to be oriented, if meaning is to accrue.